- About The Journalist’s Resource

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

Building border walls and barriers: What the research says

Are border walls effective at deterring migrants? Do they harm wildlife? How are indigenous groups in the area impacted? We explain the research.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by Denise-Marie Ordway, The Journalist's Resource February 15, 2020

In the lead-up to the 2020 elections, the Journalist’s Resource team is combing through the Democratic presidential candidates’ platforms and reporting what the research says about their policy proposals. We want to encourage deep coverage of these proposals — and do our part to help deter horse race journalism, which research suggests can lead to inaccurate reporting and an uninformed electorate. We’re focusing on proposals that have a reasonable chance of becoming policy, and for us that means several top-polling candidates say they intend to tackle the issue. Here, we look at research on building border walls.

Candidates who oppose expanding the U.S.-Mexico border barrier

Bernie Sanders , Tom Steyer *, Elizabeth Warren *

Candidates who would expand the barrier if experts recommend it

Pete Buttigieg ,* Tulsi Gabbard

Candidates whose position is unclear

Joe Biden , Michael Bloomberg *, Amy Klobuchar *

What the research says

Border barriers can discourage unauthorized border crossings, but the research is mixed in terms of how much they deter migrants from entering the U.S. without permission. Border walls and fences also can damage local habitats and impede the migration of wildlife. A number of academic articles document how the barriers that line the U.S.-Mexico border infringe on the religious and property rights of indigenous nations living in the region.

Meanwhile, hundreds of migrants die or are injured each year trying to go over and around barriers that block off much of America’s nearly 2,000-mile southwestern border. Such structures do not stop foreign visitors from arriving by air and sea and establishing residence without authorization.

Key context

Throughout time, cities, kingdoms and nation-states have built physical barriers to mark their territory, protect their inhabitants and control who and what enters and exits. In just the past few decades, countries worldwide — including the U.S. — have erected thousands of miles of border walls and fences, largely to prevent unauthorized migration. Barriers, writes researcher Elisabeth Vallet , are becoming “a norm of International relations, and a solution in the quest for security.”

“It seems like every month brings news of another border wall going up,” she wrote in The Conversation in 2017 . As of 2019, there were about 70 border barriers in existence across the globe, up from about 15 in 1990, according to Vallet, author of Borders, Fences and Walls: State of Insecurity and director of the Center for Geopolitical Studies at the University of Quebec in Montreal.

When the migrant crisis in Europe emerged several years ago, countries there began erecting barriers. Since 2015, “at least 800 miles of fences have been erected by Austria, Bulgaria, Greece, Hungary, Macedonia, Slovenia and others — a swift and concrete reaction as more than 1.8 million people descended on Europe from war zones from Afghanistan to Syria,” USA Today reported in mid-2018 .

The U.S. first built a barrier along its southwestern border between 1909 and 1911 — a barbed wire structure in southern California to keep cattle from moving between the U.S. and Mexico, Smithsonian Magazine has reported. The federal government has expanded and reinforced the barrier over time. The Wall Street Journal describes construction efforts in recent decades:

“About 119 miles of barriers were in place before 2005, according to the Government Accountability Office. Work ramped up significantly during the George W. Bush administration, particularly around El Paso, Texas. Over the next 10 years, stretching into the Obama administration, the barriers were extended to cover 654 miles in areas including Tucson, Ariz., the Rio Grande Valley and the San Diego vicinity.”

U.S. Customs and Border Protection spent $2.3 billion on fencing at U.S.-Mexico border from fiscal years 2007 through 2015, notes a 2018 report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office, the federal government’s watchdog agency. Of the 654 miles of barrier that line the U.S. border with Mexico, 300 are vehicle barriers and the rest are designed to keep pedestrians out. The border stretches 1,954 miles and runs through four states — California, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas.

While most immigrants living in the U.S. are here legally, nearly one-quarter — 10.5 million — do not have permission to be in the country, according to a 2019 report from Pew Research Center.

Donald Trump made unauthorized immigration a signature issue of his 2016 campaign. The president vowed to build at least 500 miles of new barrier by early 2021 for what will be one of the largest federal infrastructure projects in American history, The Washington Post reported earlier this month.

Shortly after Trump took office in 2017, he signed three executive orders aimed at ramping up federal efforts to control the U.S.-Mexico border and clamp down on unauthorized immigration. The first calls for an improved border barrier. It directs the U.S. Department of Homeland Security to “take all appropriate steps to immediately plan, design, and construct a physical wall along the southern border, using appropriate materials and technology to most effectively achieve complete operational control of the southern border.”

About 110 miles of the new barrier have been finished, and federal officials say a total of 450 miles will be completed or under construction by late 2020, The Washington Post explains. The federal government expects to earmark $18.4 billion for the project — enough to put up nearly 900 miles of new barrier before 2022.

Most of the new wall will replace older and smaller barriers. As the Post describes it , the wall is “far more formidable than anything previously in place along the border. The new structure has steel bollards, anchored in concrete, that reach 18 to 30 feet in height and will have lighting, cameras, sensors and improved roads to allow U.S. agents to respond quickly along an expanded ‘enforcement zone.’”

Over the years, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security has cited reductions in border apprehensions as evidence of the barrier’s effectiveness. It offers this example: When it installed fencing near Yuma, Arizona, the number of people caught crossing the border without permission plunged 90%.

In late 2017, Elaine Duke, then the acting secretary of U.S. Department of Homeland Security, wrote an editorial in USA Today explaining that border apprehensions in Yuma in fiscal year 2016 were about 10% of what they had been in fiscal year 2005. Yuma, she wrote, had been one of the first sectors along the southwestern border to receive “infrastructure investments” under the federal Secure Fence Act of 2006 , which authorized the construction of hundreds of miles of additional border fencing as well as additional checkpoints, vehicle barriers and lighting.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security released a report in 2011 , however, suggesting federal officials were unsure why apprehensions along the entire U.S.-Mexico border fell 61% between 2005 and 2010. It “may be due to a number of factors including changes in U.S. economic conditions and border enforcement efforts,” the report states.

A recent report from the U.S. Border Patrol shows that the number of people apprehended in all nine sectors of the southwestern border rose from a combined 327,577 in fiscal year 2011 to 479,371 in fiscal year 2014. While apprehensions dropped to 303,916 in fiscal year 2017, they more than doubled by the end of the 2019 fiscal year to 851,508.

Recent research

Published research on the effectiveness of border barriers is limited and offers conflicting results in terms of how much of a role barriers play in deterring unauthorized entry in the U.S.

“While advanced as a popular solution, the evidence is mixed on whether walls are effective at preventing large movements of people across borders,” Reece Jones , a political geographer at the University of Hawaii at Manoa and an international expert on border barriers, writes in a 2016 analysis for the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute .

Jones notes that border crossings in the U.S. plummeted in the 1990s, after fences were built along the southwestern border and backed up with large deployments of Border Patrol agents. He also points out that the barriers did not prevent all unauthorized crossings, but rather shifted the stream of migrants to other parts of the border.

“As high-traffic urban routes were closed, migrants and smugglers began to cross in the remote and dangerous deserts of western Arizona,” Jones writes. “Child migration from Central America to the United States, which surged in 2014, has also been undeterred by enforcement.”

Border barriers “are not particularly effective at stopping migration on their own,” he explains in the Journal of Latin American Geography in 2018. “They require constant surveillance by agents, high tech sensors, aircraft, and drones or else they can easily be climbed with a ladder.”

A 2017 report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office, criticizes the U.S. Customs and Border Protection for failing to develop metrics to assess the effectiveness of the U.S.-Mexico border barrier. The report notes that Customs and Border Protection spent about $2.3 billion from fiscal year 2007 through 2015 on fencing there and that, in 2009, the agency estimated fencing maintenance would cost more than $1 billion over the next 20 years.

“Despite these investments, CBP cannot measure the contribution of fencing to border security operations along the southwest border because it has not developed metrics for this assessment,” the U.S. Government Accountability Office writes in the 75-page report.

The federal watchdog agency points out that the U.S. Customs and Border Protection “could potentially use these data to determine the extent to which border fencing diverts illegal entrants into more rural and remote environments, and border fencing’s impact, if any, on apprehension rates over time. Developing metrics to assess the contributions of fencing to border security operations could better position CBP to make resource allocation decisions with the best information available to inform competing mission priorities and investments.”

The report states that the U.S. Department of Homeland Security had begun making changes according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office’s recommendations.

A paper forthcoming in the American Economic Journal: Applied Economics , however, indicates the border barrier has discouraged unauthorized entry. In the paper, Benjamin Feigenberg of the University of Illinois at Chicago looks at how Mexico-to-U.S. migration changed as a result of the Secure Fence Act of 2006, which prompted the federal government to add 548 miles of fencing between 2007 and 2010.

Feigenberg estimates the additional fencing resulted in a 39% decline in migration among Mexicans who live close to the border. The reduction is a bit smaller — 38% — among Mexicans who live farther away from the border, in areas of Mexico that, historically, have had little access to smugglers.

Feigenberg concludes that, overall, 41,500 Mexican migrants are deterred by the barrier each quarter, and he estimates the cost of each deterred migrant to be about $4,820.

A 2018 working paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research, updated twice in 2019, also finds that border barriers curbed migration from Mexico to the U.S., but slightly. Researchers from Dartmouth College and Stanford University found the Secure Fence Act reduced the number of Mexican nationals living in the U.S. from 2005 and 2015 by an estimated 46,459 people. That accounts for about 5% of the actual decline in migration during that period.

The paper also finds that even if the U.S. had built a barrier along the entire length of border, that would have had a relatively small impact as well. It would have reduced migration by an estimated 129,438 people, which, the researchers note, “still comprises a small portion (13%) of the observed decline in migration flows between 2005 and 2015.”

Impacts on migrant safety, indigenous rights and the environment

While scholars will continue to study border barriers’ impact on illegal entry, they have established that numerous migrants have died or been injured trying to go over or around them and that the barriers used to separate countries harm natural habitats and local wildlife.

A 2019 study published in Neurosurgery looks at injuries from jumping or falling off a section of the border wall in Arizona. From January 2012 through December 2017, 64 people sought help at Banner University of Arizona Medical Center-Tucson, a hospital adjacent to the border, for treatment of head and spine injuries.

Doctors diagnosed 78% of these individuals with a spine injury and 23% with head trauma, including skull fractures, intracranial hemorrhaging and traumatic brain injury, according to the paper. The authors estimate the cost of patients’ care at Banner totaled $6.3 million, and that public money was the primary source of funds used to pay those bills.

Hundreds of migrants die each year along the U.S.-Mexico border, particularly in southern Arizona and Texas. Multiple studies over the years have found a direct link between increased border security and migrant deaths. As the U.S. ramped up its border control efforts, more migrants sought entry through remote areas in an attempt to avoid detection, a research team led by Daniel E. Martínez of the University of Arizona writes in a 2014 paper in the Journal on Migration and Human Security .

“Previous research has illustrated that segmented border militarization has resulted in the ‘funnel effect,’ or the redistribution of migratory flows away from traditional urban crossing points into remote and dangerous areas such as the deserts of southern Arizona,” Martínez and his colleagues write. “The Sonoran Desert, which spans much of southern Arizona and northern Sonora, Mexico, is an ecologically diverse region characterized by rugged terrain, pronounced elevation changes, and relatively little rainfall. Temperatures can reach 120 degrees Fahrenheit during the summer months and drop below freezing in the winter and, at higher elevations, in the spring and fall as well.”

Researchers explain in a 2014 paper in the Journal on Migration and Human Security that more aggressive border enforcement has prompted migrants “to travel for longer periods of time through remote areas in an attempt to avoid detection by US authorities, thus increasing the probability of death.”

The U.S. Border Patrol reported 300 deaths at the southwestern border in fiscal year 2019, up slightly from 283 in fiscal year 2018 but considerably lower than the decade high of 471 deaths in fiscal year 2012.

Researchers warn, though, that government tallies might not be accurate.

David K. Androff and Kyoko Y. Tavassoli of Arizona State University write in the journal Social Work that it’s difficult to know how many migrants have died in the desert after crossing into the U.S. without permission. “Medical examiners can only investigate deaths where remains are recovered; as most of the Sonoran desert is an uninhabited, remote wilderness, the discovery of remains is dependent on their identification by U.S. Border Patrol agents or others, and researchers agree that not all remains are recovered,” they write.

Androff and Tavassoli also note in their paper, published in 2012, that “government figures tend to minimize estimates, whereas advocacy groups use higher estimates to draw attention to an issue.”

While much of the focus nationally has been on whether and how to curb illegal entry at the southwestern border, tens of thousands of foreign visitors arrive by air or water each year and do not leave. A significant number of those who stay required visas to get into the U.S. and then let them expire.

Almost 667,000 foreign visitors who were supposed to leave in fiscal year 2018 did not, including 36,289 from Brazil, 29,723 from Nigeria and 35,931 from Venezuela, according to the most recent Entry/Exit Overstay Report from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

“Nearly half of the estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants now in the country did not trek through the desert or wade across the Rio Grande to enter the country; they flew in with a visa, passed inspection at the airport — and stayed,” Miriam Jordan, a national immigration correspondent for The New York Times , wrote last year .

In fiscal year 2019, about 4% of international students and exchange visitors from countries outside North America — a combined 68,593 people — stayed in the U.S. after their expected departure date, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security report shows.

More than 40% of international students and exchange visitors who arrived by air or sea from Yemen, Chad, Eritrea and the Democratic Republic of the Congo did not leave when their visas expired in fiscal year 2019. The largest group of students and exchange visitors who overstayed their visas — totaling 12,924 people — came from China, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security report shows.

In April 2019, Trump signed a Presidential memorandum directing federal officials to find ways to address the “rampant” number of visa overstays.

The total number of suspected visa overstays rose from 482,781 in fiscal year 2015 to 739,478 in fiscal year 2016, according to a recent policy paper from Blas Nuñez-Neto , a former senior advisor to the commissioner of U.S. Customs and Border Protection who now is a senior policy researcher at Rand Corp.

A chart in Nuñez-Neto’s paper shows that visa overstays far outpaced border apprehensions between fiscal years 2015 and 2018. However, he writes in the September 2019 paper that “given the ongoing surge in unauthorized migration this year, which has resulted in more than 766,000 apprehensions in FY2019 through July 31, 2019, it appears likely that individuals apprehended along across our southern border will outstrip visa overstays in 2019.”

While U.S. border walls and fences have failed to block all migrants, legal and academic scholars have documented the various ways the structures interfere with the daily lives and rights of indigenous people living in the area.

A 2017 analysis in the American Indian Law Journal , for example, looks at the barrier’s impact on the civil and property rights of the Tohono O’odham Nation and Pascua Yaqui Tribe in Arizona, the Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas and other federally recognized tribes. The barriers have kept tribal members from accessing the southern parts of their land. They also impede the sharing of customs and have led to the desecration of burial sites, the author writes.

“Some United States Natives who have forgotten some of their customs depend on the elders on the Mexican side of the border to come teach youth culture,” the author writes. “Some Natives need to gather plants and other materials important to their spiritual practices in the deserts of Mexico, and are either unable to travel into Mexico or unable to return with those items, as overzealous border guards mistake them for forbidden plants.”

According to anthropologist Christina Leza of Colorado College, tens of thousands of U.S. tribal members live in the Mexican states of Coahuila, Chihuahua, Baja California and Sonora. She wrote in The Conversation last year that her research indicates these individuals routinely cross the U.S.-Mexico border for cultural, ceremonial or social purposes. They are treated as visitors to the U.S., required to pass through security checkpoints, where they can be interrogated, rejected or delayed.

A 2019 article in the American Indian Law Journal examines the U.S. laws that give the federal government vast authority to acquire and use land for immigration security purposes. The paper focuses on how the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996, the Secure Fence Act of 2006 and more recent federal actions have affected the Tohono O’odham. The tribe’s 2.8 million-acre reservation includes 62 miles of border between Arizona and Mexico.

“The Tohono O’odham’s mobile way of life and tribal sovereignty has progressively been infringed upon by immigration policies that have continued to tighten border security,” writes Keegan C. Tasker, from the Seattle University School of Law.

She later adds: “The imposition of these sections of the border wall through Tohono O’odham lands would cause irreparable harm to the Nation in several ways, including: (a) implications on the tribe’s sacred lands and environmental resources; (b) implications to the tribe on free movement and tribal sovereignty; and (c) stripping the tribe of sacred natural resources for spiritual and cultural practice.”

Other research finds that border construction has harmed plant and animal life in the U.S. and across the globe.

The Trump administration’s plan to build a continuous wall between the U.S. and Mexico threatens some of North America’s most biologically diverse areas, researchers write in BioScience . In the 2018 article , which includes a call to action, the authors explain that the barrier splits the geographic ranges of more than 1,000 terrestrial and freshwater animal species and 429 plant species, including 62 species the International Union for Conservation of Nature lists as critically endangered, endangered or vulnerable.

“Physical barriers prevent or discourage animals from accessing food, water, mates, and other critical resources by disrupting annual or seasonal migration and dispersal routes,” they write.

A 2016 analysis in the Review of European Comparative & International Environmental Law examines the issue from an international law and policy perspective. The authors explain that different types of border barrier affect wildlife differently. Across the globe, barriers are made of a range of materials, including concrete, sand, barbed or razor wire and electrified fencing. In some cases, metal walls extend underground. Some fencing strategies involve land mines.

Barriers are of particular concern in Central Asia, home to a variety of migratory and nomadic mammals, the authors write:

“By splitting populations, impeding migrations and killing animals attempting to cross, border fences pose an actual or potential threat to many of these, including the Mongolian gazelle (Procapra gutturosa), saiga antelope (Saiga tatarica), Asiatic wild ass (Equus hemionus, also known as khulan), Bactrian camel (Camelus ferus), argali sheep (Ovis ammon) and snow leopard (Panthera uncia).”

These barriers “have the potential to undo decades of conservation and international collaboration efforts, and their proliferation entails a need to realign our conservation paradigms with the political reality on the ground,” write the authors, from the Tilburg Law School’s Department of European and International Public Law in the Netherlands.

Another 2016 paper , this one published in PLOS Biology , finds that border barriers in Eastern Europe and Central Asia present a major threat to wildlife. A team of researchers estimates there is a total of 30,000 kilometers of border fencing in the study area and that Central Asia is one of the most heavily fenced regions on the planet.

The researchers express concern for rare or endangered species, including three mammals in Europe — the brown bear, gray wolf and Eurasian lynx. “Large spatial requirements and low population densities make conservation of these species particularly challenging, and the current successes in their conservation rely largely on the ability of individuals to move between subpopulations,” write the authors, who represent several universities and research organizations, including the Research Institute of Wildlife Ecology in Austria and the Mongolian Academy of Sciences .

Further reading

From a Distance: Geographic Proximity, Partisanship, and Public Attitudes toward the U.S.–Mexico Border Wall Jeronimo Cortina. Political Research Quarterly , forthcoming.

The gist: “Although the American public is often aligned with partisan predispositions, often ignored is the role that geographic distance to the border plays in forming attitudes. … Using geocoded survey data from 2017, this paper shows that as the distance to the U.S.-Mexico border increases, Republicans are more likely to support building a wall along the entire border with Mexico due to a lack of direct contact, supplanting direct information with partisan beliefs.”

Barriers Along the U.S. Borders: Key Authorities and Requirements Michael John Garcia. Report from the Congressional Research Center, March 2017.

The gist: This 44-page report, issued by Congress’ public policy research arm, offers a close examination of the federal laws and policies that govern how barriers can or should be used along America’s international borders. The report outlines the various laws that can be waived to proceed with the construction of border walls and fencing, including the Safe Drinking Water Act, Archeological Resources Protection Act and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

Expert sources

Treb Allen , associate professor of economics, Dartmouth College.

Peter Andreas , John Hay Professor of International Studies, Brown University.

David Androff , associate professor in the School of Social Work, Arizona State University.

Benjamin Feigenberg , assistant professor of economics, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Reece Jones , professor and chairman of the Department of Geography and Environment, University of Hawaii at Manoa.

Kenneth Madsen , associate professor of geography, Ohio State University.

Daniel E. Martínez , assistant professor of sociology, University of Arizona.

Melanie Morten , assistant professor of economics, Stanford University.

William Ripple , Distinguished Professor of Ecology, Oregon State University.

Arie Trouwborst , associate professor of environmental law, Tilburg Law School.

Elisabeth Vallet , associate professor in the department of geography, director of the Geopolitics Observatory, University of Quebec in Montreal.

*Dropped out of race since publication date.

About The Author

Denise-Marie Ordway

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Immigration & Migration

Trump and harris supporters differ on mass deportations but favor border security, high-skilled immigration.

A majority of Trump backers say more immigrants would make life worse for people like them, while most Harris backers say life wouldn’t change.

Migrant encounters at U.S.-Mexico border have fallen sharply in 2024

Most u.s. voters say immigrants – no matter their legal status – mostly take jobs citizens don’t want, why asian immigrants come to the u.s. and how they view life here, sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Fresh data delivered Saturday mornings

What the data says about immigrants in the U.S.

In 2022, roughly 10.6 million immigrants living in the U.S. were born in Mexico, making up 23% of all U.S. immigrants.

U.S. immigrant population in 2023 saw largest increase in more than 20 years

The number of immigrants living in the U.S. grew by about 1.6 million people in 2023, the largest annual increase by number since 2000.

In Tight U.S. Presidential Race, Latino Voters’ Preferences Mirror 2020

More Latino registered voters back Kamala Harris (57%) than Donald Trump (39%), and supporters of each candidate prioritize different issues.

1 in 10 eligible voters in the U.S. are naturalized citizens

Naturalized citizens make up a record number of eligible voters in 2022, most of whom have lived here more than 20 years.

The Religious Composition of the World’s Migrants

The globe’s 280 million immigrants shape countries’ religious composition. Christians make up the largest share, but Jews are most likely to have migrated.

Religious composition of the world’s migrants, 1990-2020

Explore our interactive table showing the religious composition of immigrants around the globe and how it’s changed from 1990 to 2020.

How Mexicans and Americans view each other and their governments’ handling of the border

Mexicans hold generally positive views of the United States, while Americans hold generally negative views of Mexico – a reversal from 2017.

What we know about unauthorized immigrants living in the U.S.

The unauthorized immigrant population in the U.S. grew to 11 million in 2022, but remained below the peak of 12.2 million in 2007.

How the origins of America’s immigrants have changed since 1850

In 2022, the number of immigrants living in the U.S. reached a high of 46.1 million, accounting for 13.8% of the population.

In some countries, immigration accounted for all population growth between 2000 and 2020

In 14 countries and territories, immigration accounted for more than 100% of population growth during this period.

REFINE YOUR SELECTION

Research teams.

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan, nonadvocacy fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It does not take policy positions. The Center conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, computational social science research and other data-driven research. Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts , its primary funder.

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Notifications

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 03 January 2024

Undocumented immigrants at work: invisibility, hypervisibility, and the making of the modern slave

- Paulina Segarra ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1710-4458 1 &

- Ajnesh Prasad 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 45 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

4836 Accesses

2 Citations

10 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Business and management

The undocumented immigrant represents a socio-legal category, referring to a subject who does not have legal standing to be in the country in which they are located. Extending from their lack of legal standing, undocumented immigrant workers in the United States occupy spaces marked by extreme conditions of vulnerability, which were exacerbated by the election of Donald Trump as president in 2016. The aim of this ethnographic study is to make sense of the experiences of undocumented immigrants under a particularly vicious political rhetoric. Studying the lives of Latinx undocumented immigrant workers in the U.S., our findings capture how the dynamic interplay between the types of labor that they undertake and the socio-legal identity they are attributed function together to systematically disenfranchise them. Specifically, we explicate how doing invisible labor while, at the same time, occupying a hypervisible identity culminates in extreme conditions of vulnerability. In addition to developing the concept of hypervisible identity, we also inform theory on the idea of modern slavery. We contend that without the existence of invisible labor and hypervisible identity performing as interlocking, constitutive precursors, some forms of modern slavery would be negated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Irregular migration is skilled migration: reimagining skill in EU’s migration policies

The impact of social exclusion and identity on migrant workers’ willingness to return to their hometown: micro-empirical evidence from rural China

Taking a longer historical view of america’s renaming moment: the role of black onomastic activism within the student nonviolent coordinating committee (sncc), introduction.

The undocumented immigrant represents a socio-legal category, referring to someone who does not have the legal standing to be in the country in which they are located. A lack of legal standing is critical in defining undocumented immigrants’ lived experiences. Among other things, it determines “who they are, how they relate to others, their participation in local communities, and their continued relationship to their homeland” (Menjivar, 2006 , p. 1000). While this specific circumstance has a deep impact on the lives of undocumented immigrants, it is an invisible attribute that has a deep impact on their lives.

Extending from not possessing legal standing, undocumented immigrant workers in the United States occupy precarious social and organizational spaces (Heyman, 1998 ; Mehan, 1997 ; Young, 2017 ). The precarity experienced by undocumented immigrant workers was only exacerbated with the inauguration of Donald J. Trump as the 45th American president (Giroux, 2017 ). Indeed, the polemical discourse that fermented during the campaign—coupled with the policies that were proposed and enacted in the aftermath of the presidential election—engendered more frequent and more disturbing incidents of symbolic and physical violence against those who embody (and, at times, those who are merely perceived to embody) the category of the undocumented immigrant (Huber, 2016 ).

Several researchers have identified the pressing need to account for the experiences of undocumented immigrants in the backdrop of an increasingly hostile political climate (Chomsky, 2017 ; Ngai, 2017 ). This political climate has established a “war culture” of “normalized violence” (Giroux, 2017 ), with one commentator observing that it is representative of “virulent adherence to white supremacy that opens the discursive doors of public discourses to engage in more overt and violent practices of racism that targets people of color in the U.S. and particularly Latinx immigrants” (Huber, 2016 , p. 216). In response, scholarship published since the presidential election offers preliminary findings into the detrimental outcomes created by political moves towards right-wing populism on the experiences of undocumented immigrants (Romero, 2018 )—especially on critical aspects of life such as health (Gostin and Cathaoir, 2017 ; Reardon, 2017 ) and education (Sulkowski, 2017 ; Talamantes and Aguilar-Gaxiola, 2017 ).

The question of agency is one that frequently arises when talking about immigrants. Mainwaring ( 2016 ) has highlighted the importance of agency when studying migration and asserted that this is a central concept that academics and policymakers should not disregard. On this matter, Schweitzer ( 2017 ) has highlighted the importance of understanding how migrants’ agency has been portrayed as integration and argues that “much of this agency resembles popular understandings and expectations of ‘integration’, that is, of how newcomers, in general, can and should become part of, and accepted by, the receiving society, whether through participation, incorporation or assimilation” (p. 320). Given the substantive and enduring repercussions that the recent transformations in the realm of politics have had on the lives of undocumented immigrants in the U.S., more research on this population is needed.

The aim of this ethnographic study is to understand the experiences of undocumented immigrants under a particularly vicious political rhetoric. Our main research question was: how do Latinx undocumented immigrants experience vulnerability, and how has this condition been exacerbated in the era of Donald Trump’s presidency? Our data collection was guided specifically by the following questions:

What are the lived experiences of undocumented Latinx immigrants in the United States at work and non-work contexts?

What have been the effects of Donald Trump’s rhetoric on undocumented Latinx immigrants’ identities?

What are the effects that precarious work has on undocumented Latinx immigrants’ identities?

This study allowed us to hear the voices of those Latinx immigrants who have left everything behind, hoping to achieve the “American Dream.” In our attempt to understand the extreme conditions of vulnerability under which undocumented immigrants work, we were purposeful in not limiting the scope of our examination predominantly to the nature of the work that they do (Moyce and Schenker, 2018 ; Orrenius and Zavodny, 2009 ) or to the absence of legal standing (Heyman, 1998 ; Menjivar, 2006 ), as has often been the case in extant research on the topic. Instead, we sought to ascertain a nuanced understanding of the myriad of processes occurring in work and non-work contexts by which members of this population are subjugated. Analyzing our data led us to one main discovery, which is this paper’s central contribution: populist rhetoric made the identities of undocumented immigrants hypervisible, and when that new identity is taken in tandem with the types of work that they usually have access to due to their legal—or lack thereof—legal status in the country (i.e., invisible work), has led to conditions of what could be considered modern slavery (Crane, 2013 ).

The remainder of this article unfolds in five substantive sections. First, we offer the theoretical foundation for our study. To capture the contours of life that make work—and other—experiences precarious for undocumented immigrants, we draw upon Butler’s’ ( 2004 ) articulation of vulnerability. Second, we provide a description of the methods of our ethnographic study. In this section, we detail the research context, data collection strategy, and approach to data analysis. Third, we present our findings. Our findings reveal the process by which undocumented immigrant workers experience extreme conditions of vulnerability. Fourth, we discuss the contributions of our study and identify directions for future research. Following our grounded theory approach, our contributions focus on developing a theory on the phenomenon of undocumented immigrants at work. Finally, in the fifth section, we close the article with some concluding remarks.

Theoretical foundations

Judith Butler is a contemporary social theorist whose ideas have meaningfully informed the works of scholars from disciplines across the social sciences and the humanities. Since 9/11, she has devoted much of her attention to conceptualizing the idea of vulnerability. Butler’s ( 2004 ) idea of vulnerability is a germane starting point from which to make sense of the experiences of undocumented immigrants in the U.S. as it engages the very questions that define their existence—national borders, state violence, and cultural intolerance.

Butler ( 2004 ) conceives vulnerability as the ubiquitous presence of insecurity, exploitation, and exclusion. For Butler, all lives are vulnerable, though vulnerability is not evenly distributed—thus, making some lives more vulnerable than others. She elaborates that within the paradigm of neoliberal capitalism, a value-laden set of social, political, and economic factors render certain lives to merit protections against vulnerability; and, concomitantly, other lives that would not merit such protections. Moreover, Butler specifies which lives need protecting and which lives do not by linking these questions to the discourses perennially invoked in U.S. politics about how to create and maintain invulnerability for its citizens. As she stated in an interview in which she was asked to expand on her position:

And it seems to me that implicitly what’s being promised is that, as a major First World country the US has a right to have our borders remain impermeable, protected from incursion, and to have our sovereignty guarantee our invulnerability to attack; at the same time, others, whose state formations are not like our own, or who are not explicitly in alliance with us, are to be targeted and presumptively treated as expungable, as instrumentalizable, and certainly not as enjoying the same kind of presumptive rights to invulnerability that we do. (Bell, 2010 , p. 147)

Butler elucidates how vulnerability is both socially and corporeally fabricated inasmuch as it ideologically positions certain subjects as others . Once these subjects have been othered, it gives license to cast disproportionate amounts of vulnerability onto them. Indeed, based on this vulnerability, it constructs their lives as “expungable” (insecurity), “instrumentalizable” (exploitation), and not entitled to “presumptive rights” (exclusion).

Interestingly, the bodies of one segment of the population that Butler explicitly qualifies as occupying extreme conditions of vulnerability are undocumented immigrants. Indeed, “illegal immigrants” represent “bodies (that is, human capital) …as becoming increasingly disposable, dispossessed by capital and its exploitative excess, uncountable and unaccounted for” (Butler and Athanasiou, 2013 , p. 29). This assertion is consistent with how extant research has characterized the lived realities of undocumented immigrants in the U.S. Indeed, prior scholarship has identified the plethora of ways through which undocumented immigrants are relegated to the margins of society (e.g., Fusell, 2011 ; Passel, 1986 ) and, how this relegation, engenders myriad forms of physical, symbolic, and legal violence (e.g., Menjivar and Abrego, 2012 ; Raj and Silverman, 2002 ).

We seek to extend prior studies on this group by unraveling the various repertoires of social life—and, as importantly, the interrelationships between them—that define extreme conditions of vulnerability in the lives of undocumented immigrant workers in the U.S. In other words, we seek to make sense of the specific processes occurring at work and non-work contexts by which extreme vulnerability is inscribed into their experiences. In the following section, we describe the research setting and methods of our empirical study.

Research setting and methods

To develop a theory around the experiences of undocumented immigrants at work in the United States, we followed a grounded theory methodology (Charmaz, 2006 ; Corbin and Strauss, 2008 ; Glaser and Strauss, 1967 ). This approach allowed us to inductively make sense of our data. In this section, we describe the study’s research context, data collection strategy, and data analysis approach.

Research context and empirical setting

The researcher arrived in Southern California in September 2016, a mere couple of months before Donald Trump was elected president of the United States. When Donald Trump was, in fact, elected on 8 November 2016, the researcher noticed how Latinx immigrants immediately became even more vigilant and worried. In fact, her fieldnotes reflect the concerns that she noticed the day after Trump’s election. The notes mention how 9 November 2016 was the quietest day she had experienced while she had been in Southern California since everyone around her seemed to be shocked by the news and the changes this would bring to their lives.

Choosing Southern California to perform a study on undocumented immigrants was not a coincidence. Through research aiming to find the most suitable place to develop a study on undocumented Latinx immigrants, the researcher found that the U.S. is home to approximately 11 million undocumented immigrants, 78% of whom are of Latin American origin (Hayes and Hill, 2017 ). While undocumented immigrants are dispersed across the country, a study by the Pew Research Center has found that southern California houses more undocumented immigrants than any other region in the United States (Passel and Cohn, 2017 ).

Data collection

The researcher adopted an ethnographic approach, relying on fieldwork, semi-structured interviews, and documentary data. The data collection for this study occurred between September 2016 and May 2017. After almost nine months in the field, theoretical saturation had been achieved. Even when the stories and observations that participants were sharing were still undoubtedly interesting, they had become repetitive. The researcher’s participation in the ‘Resist’ protest, which occurred on May 1st in Los Angeles, marked the conclusion of the data collection process.

Gaining, securing, and maintaining access to research participants is particularly challenging when studying a highly vulnerable population. Undocumented immigrants are ostensibly vulnerable as they are under constant fear of arrest, prosecution, and deportation for not possessing legal documents to be in the country (Fussell, 2011 ; Hernandez et al. 2013 ). Access was a significant consideration for this study, given that undocumented immigrants were encountering a new wave of political and social backlash during the period of data collection. Namely, at the start of data collection, the leading Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump was running on a xenophobic, anti-immigrant campaign. A couple of months into the commencement of data collection, Trump was elected as president. Making matters even more uncertain for the target population of the study, once he was inaugurated as president, among the first actions Trump took was the issuing of two executive orders that targeted refugees and undocumented immigrants.

The researcher was born and raised in Mexico and is fluent in Spanish. These facts offered her an initial level of legitimacy with the target population—Latinx undocumented immigrants. She also took several other steps to increase her legitimacy. Heeding Pettica-Harris, DeGama, and Elias’ ( 2016 ) observation that modifying physical appearance is an important factor in gaining access, the researcher darkened her hair and dressed modestly to be more esthetically relatable to the research participants. Ultimately, her cultural background, language skills, and esthetics increased her status of “insiderness” (Labaree, 2002 , p.102). A methodological advantage of a researcher being an insider is that it lowers the probability of encountering distrust, aggressiveness, and exclusion (Geertz, 1991 ).

Being an insider, namely, speaking the same language and aiming to somehow look like the research participants, allowed the researcher to eventually become part of the community. When reflecting on the implications that making such changes had on both the researcher and research participants; it was not done with the intention to deceive them but aiming to fit in an already vigilant community. The researcher always presented herself as a doctoral student from Mexico and when people asked more questions regarding her degree, she was always happy to answer.

Ethnographic approach

To build trust with the target population, the researcher volunteered at a large Church in Southern California that attended a Latinx congregation. This Church has a dedicated social services office that serves undocumented immigrants, the elderly, and the homeless. The social services office employed one full-time staff member, who was an undocumented immigrant herself.

In her role as a volunteer, the researcher participated in all the activities of the social services office by working closely with the full-time staff member, working 8-hour shifts at least 4 days a week, starting by the end of her first month in the field. A regular presence at the Church’s social services office allowed her to interact with and earn the trust of undocumented immigrants who sought the services of the office—and who would have likely otherwise viewed her with suspicion.

Through one of the research participants she originally met at the Church, the researcher also volunteered at the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights (CHIRLA). CHIRLA was founded in 1986 as a response to the Immigration Reform and Control Act, which made the hiring of undocumented immigrants a crime (Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights, n.d. ). At CHIRLA, the researcher became an active participant in the organization. On occasion, she also did office hours at CHIRLA’s offices, where she would pick up phones and provide basic information to immigrants who contacted the agency. Alongside these activities, dozens of informal conversations were carried out with fellow CHIRLA members, which were recorded as fieldnotes.

In order to interview undocumented immigrants who made a living as day laborers, the researcher visited five Home Depot locations. Day laborers typically gather in and around Home Depot parking lots awaiting potential jobs. Given that day laborers at these locations were exclusively men, at CHIRLA, she recruited the assistance of an older man who was himself an undocumented day laborer. He introduced her to the day laborers in and around the parking lots. The presence of this person—as both a man and an undocumented immigrant who was known to some of the day laborers—provided another layer of legitimacy to this population.

In sum, physical and social access to the target population was enabled by “gatekeepers” at various sites who “offered efficient and expedient routes to participants that would otherwise be difficult to access” (Clark, 2011 , p. 489). These gatekeepers were paramount in this study as they created trust between the researcher and the research participants by mitigating suspicion (Clark, 2011 ).

Finally, to achieve a deeper understanding of the scope of the work that undocumented immigrants perform, the researcher joined some of the participants during their work shifts at various locations. For example, on three separate occasions, she went with the Church’s social office worker, who held a second job as a cleaner, on her overnight shifts at a local Best Buy. While participating at these work sites, the researcher not only observed the participants’ work, but also performed many of the activities herself.

Semi-structured interviews

During the fieldwork stage of the study, the researcher conducted 62 interviews with undocumented immigrants from Latin America, each of which lasted between 45 minutes and two hours. While language preference for the interviews was left to the discretion of the research participants, all participants elected to have their interviews conducted in Spanish. These interviews were audio-recorded and later transcribed into verbatim text. This text was subsequently translated into English. The research participants were mostly cleaners, domestic workers, and day laborers, whom the researcher met at the Church, CHIRLA, Home Depot parking lots, and through the adoption of the snowballing technique. The questions in the interviews mostly revolved around research participants’ life and work circumstances in their countries of origin and in the U.S., as well as the challenges they encountered as a result of being undocumented immigrants. The interviews took place at different locations; sometimes, people would agree to talk with the researcher at the Church’s basement, other times on the streets while day laborers were waiting for a job, and she was once invited to one of the participants’ homes to have lunch and interview some of her friends.

Documentary data

Documentary data were collected during data collection, which included meeting minutes of CHIRLA, ‘Know Your Rights’ workshop materials, flyers which were provided by the Mexican consulate, ‘Preparing Your Family for Immigration Enforcement’ documents provided by the Roman Catholic Diocese, and ‘Lobbying Guidelines’ provided by CHIRLA from the Sacramento visit. In order to capture how undocumented immigrants were being represented in the media during the data collection period, targeted searches of newspapers, magazines, and websites were also conducted. Specifically, Time Magazine , the CNN website, The Wall Street Journal , and The Guardian were scanned to ascertain a national perspective, while the Los Angeles Times and the Voice of San Diego were examined to acquire a local perspective. In addition, Univision News was also scanned as it represents a widely consumed media outlet by the American-based Latinx population. The search yielded a total of 26 media articles that were considered relevant to the phenomenon under study. This collection of documentary data provided us with a real-time set of documents that illuminated the most pressing issues confronting undocumented immigrants in the wake of Trump’s presidential nomination and election.

Data analysis

In Footnote 1 following the tradition of grounded theory, hypotheses were not developed prior to the data being collected (Corbin and Strauss, 2008 ). Data analysis was performed in an iterative manner, which commenced while the researcher was in the field. As initial interviews and documentary evidence were collected and analyzed in the early stages of fieldwork, unforeseen aspects of the undocumented immigrant experience emerged. The interview guide evolved as a result (Charmaz, 2014 ) and, whenever possible, the researcher went back to previously interviewed research participants with new questions.

Grounded theory charges researchers with the task of observing data in ways that allow them to develop theoretical insights by conceptualizing the connections between the ideas revealed by the data, of which research participants themselves might not be aware (Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton, 2013 ). After reading the interview transcripts, a list of relevant concepts and themes was developed, which sought to identify passages in which research participants spoke about their thoughts and feelings, their lives in the U.S., and their experiences at work.

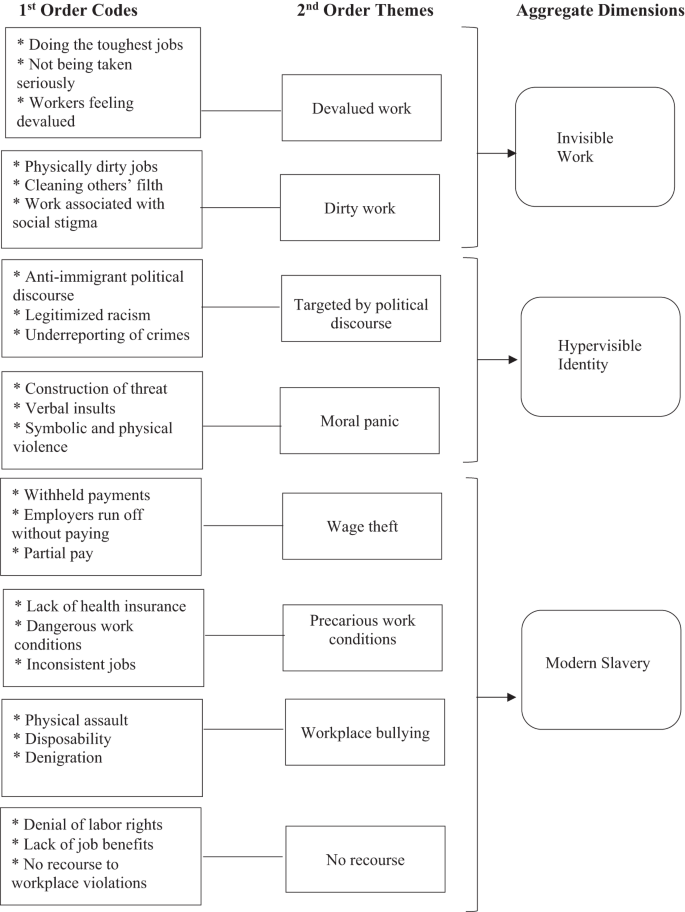

NVivo software was used to analyze data comprehensively and systematically. This process reduces the opportunities for data not to be captured during analysis (Bazeley and Jackson, 2013 ). Using NVivo allowed the authors to apply the approach to the grounded theory proposed by Gioia et al. ( 2013 ). More specifically, during the first phase of data analysis, transcripts were analyzed with the intent to allow codes to surface. Comparative analysis (Corbin and Strauss, 2008 ) was then used in order to find connections and dissimilarities between the identified passages. While comparing these quotes, we aimed to find the most prevalent issues raised by the research participants, which led us to first-order concepts. Focused coding (Charmaz, 2006 ) further allowed us to use the most meaningful initial codes to distill and classify data. Additionally, axial coding allowed us to build links between our data (Charmaz, 2015 ). Subsequently, second-order themes were ascertained based on the similarities between the first-order concepts, leading to more “theoretically revelatory” categories (Eury et al. 2018 , p. 833). Table 1 provides illustrative excerpts representative of second-order themes. As Gioia and colleagues ( 2013 ) suggested, performing this type of analysis allows for the conflation of informants’ and researchers’ voices, which links the data and allows for the emergence of new concepts and processes.

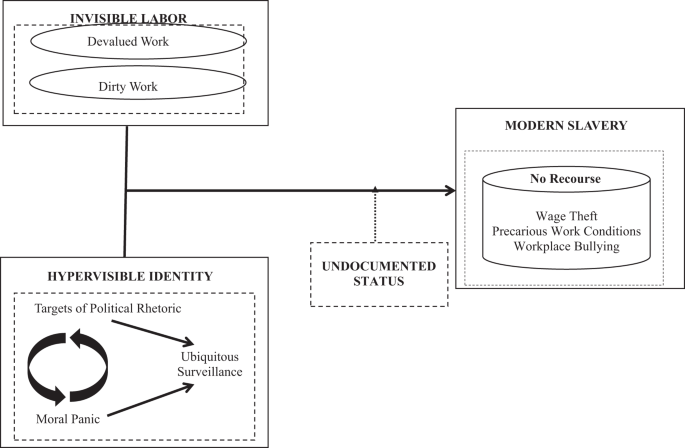

We went back and forth between the selected excerpts we identified from a set of core themes, which captured three aggregate dimensions: invisible labor , hypervisible identity , and modern slavery . We analyzed the dimensions in pursuance of the attainment of integration (Corbin and Strauss, 2008 ), which entails making sense of how the aggregate dimensions are related. This procedure allowed us to build an inductive model, which illuminates the connections between data and theory (Gioia et al. 2013 ). Our inductive model, which we explicate in our discussion, lends authenticity to our findings as it identifies how the aggregate dimensions are linked. Figure 1 offers the data structure that inductively emerged from the analysis.

Figure 1 identifies what constitutes invisible labor and the process by which hypervisible identity is socially constructed. The model depicts how the doing of invisible labor while, at the same time, occupying a hypervisible identity engenders a form of modern slavery.

The corpus of the data emanating from this study—including the ethnography, documentary evidence, and interviews—was theoretically revealing. The theoretical revelations inform the process model offered in Fig. 1 , which we use, following Eury and colleagues ( 2018 ), to structure this section. Figure 2 illuminates which themes emerged from our data analysis and shows the relationship(s) between the emergent themes. Specifically, Fig. 1 identifies what constitutes invisible labor and the process by which hypervisible identity is socially constructed. The model then depicts how the doing of invisible labor while, at the same time, occupying a hypervisible identity engenders a form of modern slavery.

Figure presents the data structure, showing first-order codes, second-order themes, and aggregate dimensions.

Figure 2 presents the data structure, showing first-order codes, second-order themes, and aggregate dimensions. To contextualize our claims and to underscore the interplay between second-order themes and aggregate dimensions, throughout this section, we will include some exemplary quotes from the interviews as well as other sources of data.

Invisible labor

Undocumented immigrants are habitually relegated to doing invisible labor. Invisible labor represents work that is largely unseen and meaningfully underappreciated by others; labor that is taken for granted and is only noticed when it is not performed. The fact that undocumented laborers are not taken into consideration most of the time renders them invisible to American society, which benefits from their work. As Herod and Aguiar ( 2006 , p. 427) observe when discussing cleaners, “most of us know when somewhere has not been cleaned but few of us…stop to think much about the laboring process which goes into maintaining spaces as clean.” Invisible work is especially tenable under circumstances when work is performed outside the formal labor market—such work is classified as not constructively contributing to the national economy (Daniels, 1988 ; Leonard, 1998 ). In our study, research participants reflected on the kind of jobs that are available to them, considering their lack of legal status. Invisible labor performed by undocumented immigrants manifested in two forms: (i) devalued work and (ii) dirty work.

Devalued work

How someone attributes meaning to the work that they do is intersubjectively constructed through the interactions between the individual who does the work and those with whom the individual is socially and professionally related (Wrzesniewski et al. 2003 ). Also, how a worker is treated by others will inform how they make sense of the value of their work as well as their professional worth (Dutton et al. 2016 ). Research participants appeared cognizant of the fact that the work that they do is not valued by others with whom they interact in the community, including those for whom they perform the work. As Rosa, a 43-year-old restaurant worker from El Salvador described, “that’s what they don’t see, it’s what these presidents don’t see…our effort. They think only about their own well-being, but they don’t think about the well-being of Latinx undocumented immigrants.” Rosa had been living in the United States for over 8 years after crossing the Rio Grande using car tires as makeshift rafts.

Undocumented immigrants undertaking devalued work is an established fact in the United States, with the well-recited proverb, undocumented immigrants do the work that Americans refuse to do , only adding veracity to the point. When asked about the reason for why undocumented immigrants do devalued work, Miguel, a Guatemalan day laborer responded: “They charge less, they take the toughest jobs, that’s why Latinxs are chosen. Gabachos (Americans) are going to take longer and will charge more money.” Edgar, a 30-year-old Guatemalan farm worker bitterly stated while waiting for a job at a street corner during a warm day in sunny California: “ Gabachos ( Americans) don’t want to do these jobs because it’s too tough…they’re afraid of the sun.”.

Research participants elaborated on feeling devalued by illuminating what Chang ( 2016 ) refers to as, their own disposability. Oscar, a Mexican man who had previously worked a factory, said: “We [undocumented immigrant workers] are disposable, once one doesn’t perform as needed, they can just bring another one.” This participant had first-hand experience of “feeling disposable” as he was replaced immediately after he had a work accident, which did not allow him to work anymore.

Further, devalued work was personally experienced by the researcher when she accompanied one of the participants on her shift as a janitor at Best Buy. The researcher reflected in her fieldnotes:

I followed her around while she skillfully worked a ghostbuster looking vacuum, leaned down to pick garbage up and pulled a 60 ft. cable around…all at the same time. Incredibly, other Best Buy’s workers wouldn’t even acknowledge her presence and would, nonchalantly, step on the cable. Others would just jump over the cable without even looking at who was cleaning the store.

The term “dirty work” refers to those “tasks and occupations that are likely to be perceived as disgusting or degrading” (Hughes cited in Ashforth and Kreiner, 1999 , p. 413) and are culturally tainted (Ashforth et al. 2017 ; Zulfiqar and Prasad, 2021 , 2022 ). Participants engaged in a wide array of what they referred to as dirty work, including house cleaning, caretaking, and landscaping. One of the participants, Estela, a Mexican woman who had been living in the U.S. without legal documents for a decade, shared one of her worst experiences with doing dirty work when she reflected on working as a janitor at a large store:

I found that one of the toilets in the men’s room was clogged with a lot of toilet paper. [Once I tried to remove the toilet paper] I saw that it was clogged with the security device that is attached to merchandise to prevent theft…It looked like someone had tried to steal something and when the alarm broke it started to make noise. In order to stop the noise, the person must have thrown the alarm into the toilet. You could still hear a very faint noise. I imagine someone else tried to use the toilet and when he flushed it, it all flooded…When I saw what happened, I cried! I looked at all the mess and thought, ‘I’m going to have to clean it, how am I going to do it?’

Individuals who perform dirty work typically experience some form of social stigmatization for doing such work (Bosmans et al. 2016 ; Duffy, 2007 ). In the study, participants explained how they were ontologically marked; that because they did dirty work, employers considered them to be dirty themselves. While riding the bus to go lobbying in Sacramento along with undocumented immigrants seeking to speak to state senators regarding immigrant rights, the researcher spoke to Claudia, a Mexican cleaning lady who recalled: “Once, a lady told me ‘you can’t use the restroom, but if you must use it, you have to clean it afterwards’…I felt humiliated. I’m not dirty!” Rocío, another Mexican cleaning lady, described an incident experienced by her husband: “They wouldn’t let him sit on the couch because they thought that he was dirty—that he smelled bad.” These denigrating comments have the effect of diminishing the undocumented immigrants’ perception of who they are, which has a lasting effect on their sense of self-worth and their idea of being helpless in a country where they have found opportunities amidst hardships.

The participants were cognizant of the fact that the dirty work they did represented the labor that no one else would want to do. As Claudia, who had previously worked as a seamstress when she arrived in the United States over two decades before, described: “No one wants to do the work that we [undocumented immigrants] do. Not cleaning, sewing, fast food jobs, or working the field.” Similarly, Oscar, a Guatemalan day laborer, who had lived in California for over a decade, asserted: “If Trump is set on getting rid of all illegal people, I don’t think an American is going to go wash toilets for minimum wage.” In both quotes, participants suggest that the “dirty jobs” that they undertake would not be performed by American-born citizens or others with legal residency status would do it for a considerably higher amount of money.

Hypervisible identity

Foucault ( 1977 ) used subjectivity to conceptualize how individuals devise their sense of self (i.e., identity). For Foucault, subjectivity is a discursive, identity-forming project that establishes how individuals perceive themselves, which, in turn, determines how they relate to others. Butler ( 1997 ) adopted Foucualt’s meaning of the term to argue that subjectivity is only possible when one’s identity is recognized in social discourse—that is, when one is recognized by others. Extending the works of Foucault and Butler, we define hypervisible identity as the sense of self that is formed when the recognition from others is cast with the intent to discursively and juridically control one’s existence by rendering their subjectivity to be readily available for social and political interrogation. The study reveals that hypervisible identity emerged as the corollary of three interrelated social phenomena directed towards undocumented immigrants: (i) targeting them in political rhetoric, (ii) moral panic, and (iii) ubiquitous surveillance.

Targets of political rhetoric

While undocumented immigrants have often been the targets of political rhetoric in the U.S., Trump’s toxic anti-immigrant and xenophobic discourse only heightened their vulnerability (Giroux, 2017 ). When announcing his bid for the Republican nomination for president on 16 June 2015, Trump stated: “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best…They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists” (Koplan, 2016 ). Trump echoed his claim in the following tweet directed at undocumented immigrants: “Illegal immigration costs the United States more than 200 billion Dollars a year. How was this allowed to happen?” In another tweet, he added: “Mexico is not our friend. They’re killing us at the border and they’re killing us on jobs and trade. FIGHT!” Note how Trump makes a call for action (‘FIGHT!’) that was directed at undermining any sense of security of immigrants who crossed the border into the US illegally. In fact, as Saramo ( 2017 ) has stated, “the rise of Donald Trump…has relied on emotional evocations of violence—fear, threats, aggression, hatred, and division” (p.1).

Trump reified his anti-immigrant and xenophobic discourse by signing executive orders shortly after being inaugurated as president. On 25 January 2017, two executive orders were signed that ostensibly targeted undocumented immigrants. Trump justified his executive orders by asserting: “[A] nation without borders is not a nation…I just signed two Executive Orders that will save thousands of lives, millions of jobs, and billions of dollars” (Smith, 2017 ).

Research participants described the uncertainty engendered by being the targets of political rhetoric. One month after President Trump took office, the researcher had the chance to speak with several women who were part of the domestic workers coalition. During one interview, Rocío, an undocumented cleaning lady originally from Mexico poignantly said:

Now with what’s happening with the president…he made all the people who were already racist to come out. He made these hidden people to come out and feel with the freedom to reject us, disrespect us, yell at us, offend us. He encouraged this.

Similarly, others commented: “I never thought a crazy man would be president…he is encouraging the people who are racist like him” (Edgar) and “the new president wants to separate us from our kids” (Maru).

Being targeted in political rhetoric had direct and far-reaching effects on the undocumented immigrant community. Los Angeles Police Chief, Charlie Beck, cited one such detrimental outcome. Beck stated that undocumented immigrants were refraining from reporting incidents of sexual assault and domestic violence due to the fear that engaging with the police would lead to deportation (Queally, 2017 ).

Moral panic

Being targeted in political rhetoric functioned as a precursor to moral panic. Moral panic refers to “[a] condition, episode, person, or groups of persons emerges to become defined as a threat to societal values and interests” (Cohen, 1972 , p. 9). During moral panics, societal harm may either be “alleged but imaginary” or “real but exaggerated” (Goode & Ben Yehuda cited in Laws, 2016 , p. 12). Moral panic developed against undocumented immigrants, who were portrayed as job-stealing criminals whom the citizenry needed urgent protection (Stupi, Chiricos, and Gertz, 2016 ; for a related argument on the outcome of this phenomenon on legal immigrants, see Zatz and Smith, 2012 ). Moral panic against undocumented immigrants is not grounded in any such reality. Extant research has consistently shown undocumented immigrants do not commit disproportionately higher rates of crime than others in the U.S. (O’Brien et al. 2019 ; Wang, 2012 ); in fact, statistically speaking, undocumented immigrants engage in lower rates of crime relative to others (Light and Miller, 2018 ).

Although this moral panic is not based in fact, it did have material consequences on the experiences of undocumented immigrants—and others who were perceived to be “one of them.” Indeed, there was a proliferation of violence against undocumented immigrants from members of the public who perceived them as threats to the existing social order. In the immediate aftermath of Trump’s inauguration, Univision News reported that they received hundreds of cases of anti-immigrant physical and non-physical violence (Weiss, 2017 ). A candid example of this violence was offered by CNN in a report about a homeless man of Latin descent being assaulted and urinated on by two men with one of them declaring: “Donald Trump was right, all these illegals need to be deported” (Ferrigno, 2015 ).

During Donald Trump’s presidential campaign, he invoked the death of Kate Steinle, a young woman who had allegedly been murdered in San Francisco by a Mexican undocumented immigrant. Trump stated, “This senseless and totally preventable act of violence committed by an illegal immigrant is yet another example of why we must secure our border immediately…This is an absolutely disgraceful situation, and I am the only one that can fix it” (Schleifer, 2015 ). Trump even made a point of meeting with family members of people killed by undocumented immigrants as a part of his political campaign (Gray, 2015 ). When José Inés García Zárate, the man accused of Steinle’s death, was acquitted in late November 2017, Trump responded with two tweets that aggrandized the fear of undocumented immigrants that the American population was already experiencing: “A disgraceful verdict in the Kate Steinle case! No wonder the people in our Country are so angry with illegal immigration” and “The Kate Steinle killer came back and back over the weakly protected Obama border, always committing crimes and being violent, and yet this info was not used in court. His exoneration is a complete travesty of justice. BUILD THE WALL!” (Tatum, 2017 ). While conducting fieldwork, the researcher noticed the conspicuous apprehension felt by some Americans who, fostered by toxic political rhetoric, interpreted undocumented immigrants to be an omnipresent threat. This apprehension among Americans was captured during a conversation with a Mexican day laborer who said that after Trump’s statements, he was getting fewer jobs since employers were afraid to take him to their homes, fearing that their physical well-being and their property would be at risk. Trump had previously been seen as a celebrity and a successful businessman, so there were people eagerly willing to follow his ideas (Mollan and Geesin, 2020 ).

The outcomes of moral panic against undocumented immigrants were also represented in the interviews. One of the research participants, María, a woman from Honduras, described how she had been verbally attacked on the streets: “Once I was walking by, and someone said, ‘oh, look! All of them illegal immigrants, all of them, all those people are shit. They are trash.’” Another participant described his experience while waiting for a job as a day laborer: “The gabachos (Americans) go by and say, ‘those are the ones who need to be deported’” (Edgar). In the construction of this moral panic, undocumented immigrants are configured as deviants whose extrication from the country (“need to be deported”) will establish the proper social order.

Ubiquitous surveillance

Political rhetoric and moral panic, when taken collectively, establish ubiquitous surveillance in the lives of undocumented immigrants. Surveillance of this group manifested ubiquitously through two distinct, though mutually constituting, forms: social constructions and discursive constructions. That is, for undocumented immigrants, it involved being both surveilled by others and surveilling themselves. The latter phenomenon is perhaps best reflected in Foucault’s ( 1997 ) idea of the panopticon—the gaze under which subjects monitor their behavior through internalized governance.

The first form of ubiquitous surveillance appeared to be socially constructed. Immediately following Trump’s inauguration, there were some high-profile raids by ICE agents in Southern California. The chilling effects of these raids were felt immediately among undocumented immigrants. Undocumented immigrants became fearful of being constantly watched by authorities who might at any time raid a residence or place of employment to arrest them. The uncertainty of arrest (and subsequent deportation) was evidenced by the numerous individuals who spoke with the researcher when they visited the Church’s social office and CHIRLA seeking advice about what they should do in case of arrest. At the Church, among other things, the full-time employee (and the researcher) handed out a flyer entitled “Preparing Your Family for Immigration Enforcement,” which was prepared by the Archdiocese of Los Angeles. The document detailed the necessary precautions that undocumented immigrants should take given the increasingly hostile climate towards them (e.g., have an emergency plan, what to do during a raid, what to do if immigration officers visit your home, what your rights are under detention). Similarly, CHIRLA workers would furnish “rights cards” to undocumented immigrants, which they were to provide to ICE officers in case of arrest. The card read:

I am giving you this card because I do not wish to speak to you or have any further contact with you. I choose to exercise my constitutional right to remain silent and refuse to answer your questions. If you arrest me, I will continue to exercise my right to remain silent and refuse to answer any of your questions. I want to speak to a lawyer before answering your questions. I would like to contact this attorney or Organization:

Interestingly, documents such as these only further inculcated, among undocumented immigrants, the omnipresent sense that they are being watched and at risk of arrest.

The second form of ubiquitous surveillance was, in essence, caused by the first form. Specifically, the social construction of ubiquitous surveillance was shown to be experienced discursively. In assuming that they were being watched, undocumented immigrants internalized the surveillance and began to change how they behaved in meaningful ways. For instance, several research participants quit their jobs in fear of encountering ICE. Out of necessity, others kept working, though the fear remained significant. While being interviewed at a Home Depot parking lot, Juan, a 22-year-old day laborer who had arrived in the U.S. only a month before, said:

I’m afraid to come to work because if Immigration [an ICE officer] sees me…I want to be honest with the law. I want to abide the law, what the law says but, how am I supposed to eat now? I have to work, I have to fight for my daughter, for my wife.

Similarly, Roberto, another Mexican day laborer recalled: “On the subway, you do not see so many Latin people that come to work anymore… It has been a problem for me since I am afraid that I might run into an immigration agent in a subway station.”

The discursive effects of ubiquitous surveillance were associated with psychological problems such as anxiety and paranoia. Victoria, an undocumented immigrant of Mexican origin who continuously volunteered at CHIRLA, felt detrimentally impacted by the new stories about the ongoing ICE raids, which instilled into the participant that fear of imminent raid. As she explained:

I don’t want to go out, even yesterday I was locked in all day…I didn’t even want to go to the grocery store which is very close. I didn’t want to go out at all. I heard people going upstairs and I quickly looked through the window to check who it was. I was anxious, completely anxious and on edge…I am taking pills to feel calmer since we heard the news about the raids.

The routines of Victoria’s life were altered dramatically as she internalized the (fear of) ubiquitous surveillance. The following account from her further underscores this point: