- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

6.6: De Broglie’s Matter Waves

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 4524

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe de Broglie’s hypothesis of matter waves

- Explain how the de Broglie’s hypothesis gives the rationale for the quantization of angular momentum in Bohr’s quantum theory of the hydrogen atom

- Describe the Davisson–Germer experiment

- Interpret de Broglie’s idea of matter waves and how they account for electron diffraction phenomena

Compton’s formula established that an electromagnetic wave can behave like a particle of light when interacting with matter. In 1924, Louis de Broglie proposed a new speculative hypothesis that electrons and other particles of matter can behave like waves. Today, this idea is known as de Broglie’s hypothesis of matter waves . In 1926, De Broglie’s hypothesis, together with Bohr’s early quantum theory, led to the development of a new theory of wave quantum mechanics to describe the physics of atoms and subatomic particles. Quantum mechanics has paved the way for new engineering inventions and technologies, such as the laser and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). These new technologies drive discoveries in other sciences such as biology and chemistry.

According to de Broglie’s hypothesis, massless photons as well as massive particles must satisfy one common set of relations that connect the energy \(E\) with the frequency \(f\), and the linear momentum \(p\) with the wavelength \(λ\). We have discussed these relations for photons in the context of Compton’s effect. We are recalling them now in a more general context. Any particle that has energy and momentum is a de Broglie wave of frequency \(f\) and wavelength \(\lambda\):

\[ E = h f \label{6.53} \]

\[ \lambda = \frac{h}{p} \label{6.54} \]

Here, \(E\) and \(p\) are, respectively, the relativistic energy and the momentum of a particle. De Broglie’s relations are usually expressed in terms of the wave vector \(\vec{k}\), \(k = 2 \pi / \lambda\), and the wave frequency \(\omega = 2 \pi f\), as we usually do for waves:

\begin{aligned} &E=\hbar \omega \label{6.55}\\ &\vec{p}=\hbar \vec{k} \label{6.56} \end{aligned}

Wave theory tells us that a wave carries its energy with the group velocity . For matter waves, this group velocity is the velocity \(u\) of the particle. Identifying the energy E and momentum p of a particle with its relativistic energy \(mc^2\) and its relativistic momentum \(mu\), respectively, it follows from de Broglie relations that matter waves satisfy the following relation:

\[ \lambda f =\frac{\omega}{k}=\frac{E / \hbar}{p / \hbar}=\frac{E}{p} = \frac{m c^{2}}{m u}=\frac{c^{2}}{u}=\frac{c}{\beta} \label{6.57} \]

where \(\beta = u/c\). When a particle is massless we have \(u=c\) and Equation \ref{6.57} becomes \(\lambda f = c\).

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): How Long are de Broglie Matter Waves?

Calculate the de Broglie wavelength of:

- a 0.65-kg basketball thrown at a speed of 10 m/s,

- a nonrelativistic electron with a kinetic energy of 1.0 eV, and

- a relativistic electron with a kinetic energy of 108 keV.

We use Equation \ref{6.57} to find the de Broglie wavelength. When the problem involves a nonrelativistic object moving with a nonrelativistic speed u , such as in (a) when \(\beta=u / c \ll 1\), we use nonrelativistic momentum p . When the nonrelativistic approximation cannot be used, such as in (c), we must use the relativistic momentum \(p=m u=m_{0} \gamma u=E_{0} \gamma \beta/c\), where the rest mass energy of a particle is \(E_0 = m c^2 \) and \(\gamma\) is the Lorentz factor \(\gamma=1 / \sqrt{1-\beta^{2}}\). The total energy \(E\) of a particle is given by Equation \ref{6.53} and the kinetic energy is \(K=E-E_{0}=(\gamma-1) E_{0}\). When the kinetic energy is known, we can invert Equation 6.4.2 to find the momentum

\[ p=\sqrt{\left(E^{2}-E_{0}^{2}\right) / c^{2}}=\sqrt{K\left(K+2 E_{0}\right)} / c \nonumber \]

and substitute into Equation \ref{6.57} to obtain

\[ \lambda=\frac{h}{p}=\frac{h c}{\sqrt{K\left(K+2 E_{0}\right)}} \label{6.58} \]

Depending on the problem at hand, in this equation we can use the following values for hc :

\[ h c=\left(6.626 \times 10^{-34} \: \mathrm{J} \cdot \mathrm{s}\right)\left(2.998 \times 10^{8} \: \mathrm{m} / \mathrm{s}\right)=1.986 \times 10^{-25} \: \mathrm{J} \cdot \mathrm{m}=1.241 \: \mathrm{eV} \cdot \mu \mathrm{m} \nonumber \]

- For the basketball, the kinetic energy is \[ K=m u^{2} / 2=(0.65 \: \mathrm{kg})(10 \: \mathrm{m} / \mathrm{s})^{2} / 2=32.5 \: \mathrm{J} \nonumber \] and the rest mass energy is \[ E_{0}=m c^{2}=(0.65 \: \mathrm{kg})\left(2.998 \times 10^{8} \: \mathrm{m} / \mathrm{s}\right)^{2}=5.84 \times 10^{16} \: \mathrm{J} \nonumber \] We see that \(K /\left(K+E_{0}\right) \ll 1\) and use \(p=m u=(0.65 \: \mathrm{kg})(10 \: \mathrm{m} / \mathrm{s})=6.5 \: \mathrm{J} \cdot \mathrm{s} / \mathrm{m} \): \[ \lambda=\frac{h}{p}=\frac{6.626 \times 10^{-34} \: \mathrm{J} \cdot \mathrm{s}}{6.5 \: \mathrm{J} \cdot \mathrm{s} / \mathrm{m}}=1.02 \times 10^{-34} \: \mathrm{m} \nonumber \]

- For the nonrelativistic electron, \[ E_{0}=mc^{2}=\left(9.109 \times 10^{-31} \mathrm{kg}\right)\left(2.998 \times 10^{8} \mathrm{m} / \mathrm{s}\right)^{2}=511 \mathrm{keV} \nonumber \] and when \(K = 1.0 \: eV\), we have \(K/(K+E_0) = (1/512) \times 10^{-3} \ll 1\), so we can use the nonrelativistic formula. However, it is simpler here to use Equation \ref{6.58}: \[ \lambda=\frac{h}{p}=\frac{h c}{\sqrt{K\left(K+2 E_{0}\right)}}=\frac{1.241 \: \mathrm{eV} \cdot \mu \mathrm{m}}{\sqrt{(1.0 \: \mathrm{eV})[1.0 \: \mathrm{eV}+2(511 \: \mathrm{keV})]}}=1.23 \: \mathrm{nm} \nonumber \] If we use nonrelativistic momentum, we obtain the same result because 1 eV is much smaller than the rest mass of the electron.

- For a fast electron with \(K=108 \: keV\), relativistic effects cannot be neglected because its total energy is \(E = K = E_0 = 108 \: keV + 511 \: keV = 619 \: keV\) and \(K/E = 108/619\) is not negligible: \[ \lambda=\frac{h}{p}=\frac{h c}{\sqrt{K\left(K+2 E_{0}\right)}}=\frac{1.241 \: \mathrm{eV} \cdot \mu \mathrm{m}}{\sqrt{108 \: \mathrm{keV}[108 \: \mathrm{keV}+2(511 \: \mathrm{keV})]}}=3.55 \: \mathrm{pm} \nonumber \].

Significance

We see from these estimates that De Broglie’s wavelengths of macroscopic objects such as a ball are immeasurably small. Therefore, even if they exist, they are not detectable and do not affect the motion of macroscopic objects.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

What is de Broglie’s wavelength of a nonrelativistic proton with a kinetic energy of 1.0 eV?

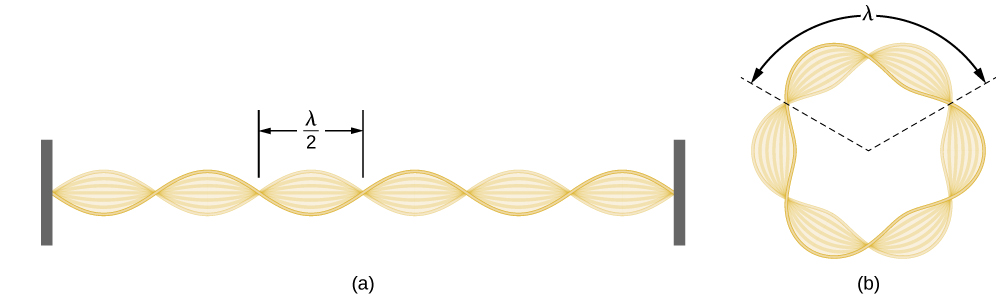

Using the concept of the electron matter wave, de Broglie provided a rationale for the quantization of the electron’s angular momentum in the hydrogen atom, which was postulated in Bohr’s quantum theory. The physical explanation for the first Bohr quantization condition comes naturally when we assume that an electron in a hydrogen atom behaves not like a particle but like a wave. To see it clearly, imagine a stretched guitar string that is clamped at both ends and vibrates in one of its normal modes. If the length of the string is l (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)), the wavelengths of these vibrations cannot be arbitrary but must be such that an integer k number of half-wavelengths \(\lambda/2\) fit exactly on the distance l between the ends. This is the condition \(l=k \lambda /2\) for a standing wave on a string. Now suppose that instead of having the string clamped at the walls, we bend its length into a circle and fasten its ends to each other. This produces a circular string that vibrates in normal modes, satisfying the same standing-wave condition, but the number of half-wavelengths must now be an even number \(k\), \(k=2n\), and the length l is now connected to the radius \(r_n\) of the circle. This means that the radii are not arbitrary but must satisfy the following standing-wave condition:

\[ 2 \pi r_{n}=2 n \frac{\lambda}{2} \label{6.59}. \]

If an electron in the n th Bohr orbit moves as a wave, by Equation \ref{6.59} its wavelength must be equal to \(\lambda = 2 \pi r_n / n\). Assuming that Equation \ref{6.58} is valid, the electron wave of this wavelength corresponds to the electron’s linear momentum, \(p = h/\lambda = nh / (2 \pi r_n) = n \hbar /r_n\). In a circular orbit, therefore, the electron’s angular momentum must be

\[ L_{n}=r_{n} p=r_{n} \frac{n \hbar}{r_{n}}=n \hbar \label{6.60} . \]

This equation is the first of Bohr’s quantization conditions, given by Equation 6.5.6 . Providing a physical explanation for Bohr’s quantization condition is a convincing theoretical argument for the existence of matter waves.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\): The Electron Wave in the Ground State of Hydrogen

Find the de Broglie wavelength of an electron in the ground state of hydrogen.

We combine the first quantization condition in Equation \ref{6.60} with Equation 6.5.6 and use Equation 6.5.9 for the first Bohr radius with \(n = 1\).

When \(n=1\) and \(r_n = a_0 = 0.529 \: Å\), the Bohr quantization condition gives \(a_{0} p=1 \cdot \hbar \Rightarrow p=\hbar / a_{0}\). The electron wavelength is:

\[ \lambda=h / p = h / \hbar / a_{0} = 2 \pi a_{0} = 2 \pi(0.529 \: Å)=3.324 \: Å .\nonumber \]

We obtain the same result when we use Equation \ref{6.58} directly.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Find the de Broglie wavelength of an electron in the third excited state of hydrogen.

\(\lambda = 2 \pi n a_0 = 2 (3.324 \: Å) = 6.648 \: Å\)

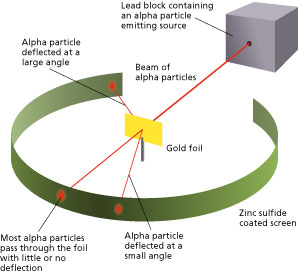

Experimental confirmation of matter waves came in 1927 when C. Davisson and L. Germer performed a series of electron-scattering experiments that clearly showed that electrons do behave like waves. Davisson and Germer did not set up their experiment to confirm de Broglie’s hypothesis: The confirmation came as a byproduct of their routine experimental studies of metal surfaces under electron bombardment.

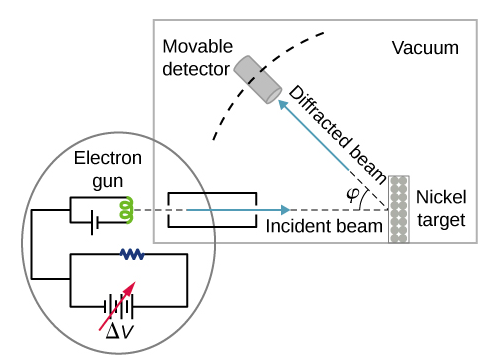

In the particular experiment that provided the very first evidence of electron waves (known today as the Davisson–Germer experiment ), they studied a surface of nickel. Their nickel sample was specially prepared in a high-temperature oven to change its usual polycrystalline structure to a form in which large single-crystal domains occupy the volume. Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) shows the experimental setup. Thermal electrons are released from a heated element (usually made of tungsten) in the electron gun and accelerated through a potential difference ΔV, becoming a well-collimated beam of electrons produced by an electron gun. The kinetic energy \(K\) of the electrons is adjusted by selecting a value of the potential difference in the electron gun. This produces a beam of electrons with a set value of linear momentum, in accordance with the conservation of energy:

\[ e \Delta V=K=\frac{p^{2}}{2 m} \Rightarrow p=\sqrt{2 m e \Delta V} \label{6.61} \]

The electron beam is incident on the nickel sample in the direction normal to its surface. At the surface, it scatters in various directions. The intensity of the beam scattered in a selected direction φφ is measured by a highly sensitive detector. The detector’s angular position with respect to the direction of the incident beam can be varied from φ=0° to φ=90°. The entire setup is enclosed in a vacuum chamber to prevent electron collisions with air molecules, as such thermal collisions would change the electrons’ kinetic energy and are not desirable.

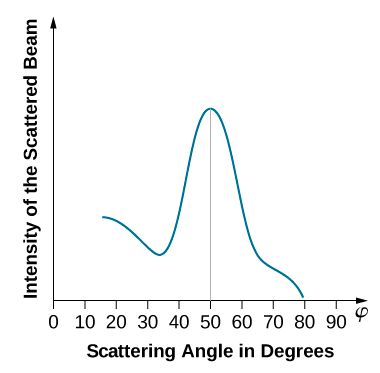

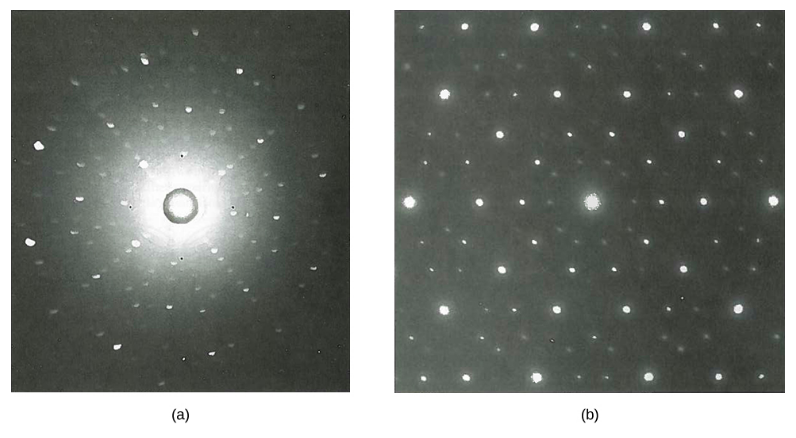

When the nickel target has a polycrystalline form with many randomly oriented microscopic crystals, the incident electrons scatter off its surface in various random directions. As a result, the intensity of the scattered electron beam is much the same in any direction, resembling a diffuse reflection of light from a porous surface. However, when the nickel target has a regular crystalline structure, the intensity of the scattered electron beam shows a clear maximum at a specific angle and the results show a clear diffraction pattern (see Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). Similar diffraction patterns formed by X-rays scattered by various crystalline solids were studied in 1912 by father-and-son physicists William H. Bragg and William L. Bragg. The Bragg law in X-ray crystallography provides a connection between the wavelength \(\lambda\) of the radiation incident on a crystalline lattice, the lattice spacing, and the position of the interference maximum in the diffracted radiation (see Diffraction ).

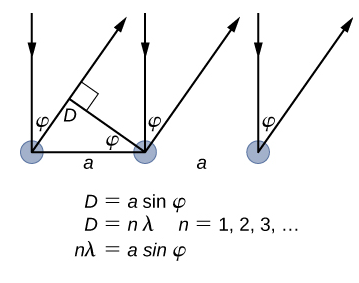

The lattice spacing of the Davisson–Germer target, determined with X-ray crystallography, was measured to be \(a=2.15 \: Å\). Unlike X-ray crystallography in which X-rays penetrate the sample, in the original Davisson–Germer experiment, only the surface atoms interact with the incident electron beam. For the surface diffraction, the maximum intensity of the reflected electron beam is observed for scattering angles that satisfy the condition nλ = a sin φ (see Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). The first-order maximum (for n=1) is measured at a scattering angle of φ≈50° at ΔV≈54 V, which gives the wavelength of the incident radiation as λ=(2.15 Å) sin 50° = 1.64 Å. On the other hand, a 54-V potential accelerates the incident electrons to kinetic energies of K = 54 eV. Their momentum, calculated from Equation \ref{6.61}, is \(p = 2.478 \times 10^{−5} \: eV \cdot s/m\). When we substitute this result in Equation \ref{6.58}, the de Broglie wavelength is obtained as

\[ \lambda=\frac{h}{p}=\frac{4.136 \times 10^{-15} \mathrm{eV} \cdot \mathrm{s}}{2.478 \times 10^{-5} \mathrm{eV} \cdot \mathrm{s} / \mathrm{m}}=1.67 \mathrm{Å} \label{6.62}. \]

The same result is obtained when we use K = 54eV in Equation \ref{6.61}. The proximity of this theoretical result to the Davisson–Germer experimental value of λ = 1.64 Å is a convincing argument for the existence of de Broglie matter waves.

Diffraction lines measured with low-energy electrons, such as those used in the Davisson–Germer experiment, are quite broad (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)) because the incident electrons are scattered only from the surface. The resolution of diffraction images greatly improves when a higher-energy electron beam passes through a thin metal foil. This occurs because the diffraction image is created by scattering off many crystalline planes inside the volume, and the maxima produced in scattering at Bragg angles are sharp (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)).

Since the work of Davisson and Germer, de Broglie’s hypothesis has been extensively tested with various experimental techniques, and the existence of de Broglie waves has been confirmed for numerous elementary particles. Neutrons have been used in scattering experiments to determine crystalline structures of solids from interference patterns formed by neutron matter waves. The neutron has zero charge and its mass is comparable with the mass of a positively charged proton. Both neutrons and protons can be seen as matter waves. Therefore, the property of being a matter wave is not specific to electrically charged particles but is true of all particles in motion. Matter waves of molecules as large as carbon \(C_{60}\) have been measured. All physical objects, small or large, have an associated matter wave as long as they remain in motion. The universal character of de Broglie matter waves is firmly established.

Example \(\PageIndex{3A}\): Neutron Scattering

Suppose that a neutron beam is used in a diffraction experiment on a typical crystalline solid. Estimate the kinetic energy of a neutron (in eV) in the neutron beam and compare it with kinetic energy of an ideal gas in equilibrium at room temperature.

We assume that a typical crystal spacing a is of the order of 1.0 Å. To observe a diffraction pattern on such a lattice, the neutron wavelength λ must be on the same order of magnitude as the lattice spacing. We use Equation \ref{6.61} to find the momentum p and kinetic energy K . To compare this energy with the energy \(E_T\) of ideal gas in equilibrium at room temperature \(T = 300 \, K\), we use the relation \(K = 3/2 k_BT\), where \(k_B = 8.62 \times 10^{-5}eV/K\) is the Boltzmann constant.

We evaluate pc to compare it with the neutron’s rest mass energy \(E_0 = 940 \, MeV\):

\[p = \frac{h}{\lambda} \Rightarrow pc = \frac{hc}{\lambda} = \frac{1.241 \times 10^{-6}eV \cdot m}{10^{-10}m} = 12.41 \, keV. \nonumber \]

We see that \(p^2c^2 << E_0^2\) and we can use the nonrelativistic kinetic energy:

\[K = \frac{p^2}{2m_n} = \frac{h^2}{2\lambda^2 m_n} = \frac{(6.63\times 10^{−34}J \cdot s)^2}{(2\times 10^{−20}m^2)(1.66 \times 10^{−27} kg)} = 1.32 \times 10^{−20} J = 82.7 \, meV. \nonumber \]

Kinetic energy of ideal gas in equilibrium at 300 K is:

\[K_T = \frac{3}{2}k_BT = \frac{3}{2} (8.62 \times 10^{-5}eV/K)(300 \, K) = 38.8 \, MeV. \nonumber \]

We see that these energies are of the same order of magnitude.

Neutrons with energies in this range, which is typical for an ideal gas at room temperature, are called “thermal neutrons.”

Example \(\PageIndex{3B}\): Wavelength of a Relativistic Proton

In a supercollider at CERN, protons can be accelerated to velocities of 0.75 c . What are their de Broglie wavelengths at this speed? What are their kinetic energies?

The rest mass energy of a proton is \(E_0 = m_0c^2 = (1.672 \times 10^{−27} kg)(2.998 \times 10^8m/s)^2 = 938 \, MeV\). When the proton’s velocity is known, we have β = 0.75 and \(\beta \gamma = 0.75 / \sqrt{1 - 0.75^2} = 1.714\). We obtain the wavelength λλ and kinetic energy K from relativistic relations.

\[\lambda = \frac{h}{p} = \frac{hc}{\beta \gamma E_0} = \frac{1.241 \, eV \cdot \mu m}{1.714 (938 \, MeV)} = 0.77 \, fm \nonumber \]

\[K = E_0(\gamma - 1) = 938 \, MeV (1 /\sqrt{1 - 0.75^2} - 1) = 480.1\, MeV \nonumber \]

Notice that because a proton is 1835 times more massive than an electron, if this experiment were performed with electrons, a simple rescaling of these results would give us the electron’s wavelength of (1835)0.77 fm = 1.4 pm and its kinetic energy of 480.1 MeV /1835 = 261.6 keV.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Find the de Broglie wavelength and kinetic energy of a free electron that travels at a speed of 0.75 c .

\(\lambda = 1.417 \, pm; \, K = 261.56 \, keV\)

Talk to our experts

1800-120-456-456

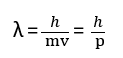

- De Broglie Equation

Introduction

The wave nature of light was the only aspect that was considered until Neil Bohr’s model. Later, however, Max Planck in his explanation of quantum theory hypothesized that light is made of very minute pockets of energy which are in turn made of photons or quanta. It was then considered that light has a particle nature and every packet of light always emits a certain fixed amount of energy.

By this, the energy of photons can be expressed as:

E = hf = h * c/λ

Here, h is Plank’s constant

F refers to the frequency of the waves

Λ implies the wavelength of the pockets

Therefore, this basically insinuates that light has both the properties of particle duality as well as wave.

Louis de Broglie was a student of Bohr, who then formulated his own hypothesis of wave-particle duality, drawn from this understanding of light. Later on, when this hypothesis was proven true, it became a very important concept in particle physics.

⇒ Don't Miss Out: Get Your Free JEE Main Rank Predictor 2024 Instantly! 🚀

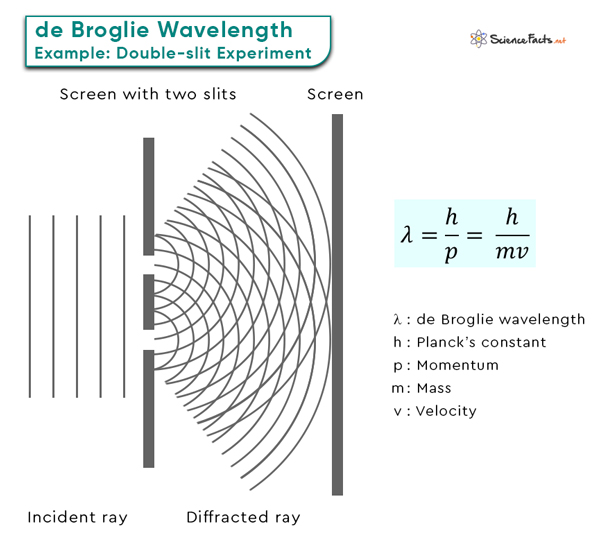

What is the De Broglie Equation?

Quantum mechanics assumes matter to be both like a wave as well as a particle at the sub-atomic level. The De Broglie equation states that every particle that moves can sometimes act as a wave, and sometimes as a particle. The wave which is associated with the particles that are moving are known as the matter-wave, and also as the De Broglie wave. The wavelength is known as the de Broglie wavelength.

For an electron, de Broglie wavelength equation is:

λ = \[\frac{h}{mv}\]

Here, λ points to the wave of the electron in question

M is the mass of the electron

V is the velocity of the electron

Mv is the momentum that is formed as a result

It was found out that this equation works and applies to every form of matter in the universe, i.e, Everything in this universe, from living beings to inanimate objects, all have wave particle duality.

Significance of De Broglie Equation

De Broglie says that all the objects that are in motion have a particle nature. However, if we look at a moving ball or a moving car, they don’t seem to have particle nature. To make this clear, De Broglie derived the wavelengths of electrons and a cricket ball. Now, let’s understand how he did this.

De Broglie Wavelength

1. De Broglie Wavelength for a Cricket Ball

Let’s say,Mass of the ball = 150 g (150 x 10⁻³ kg),

Velocity = 35 m/s,

and h = 6.626 x 10⁻³⁴ Js

Now, putting these values in the equation

λ = (6.626 * 10 to power of -34)/ (150 * 10 to power of -3 *35)

This yields

λBALL = 1.2621 x 10 to the power of -34 m,

Which is 1.2621 x 10 to the power of -24 Å.

We know that Å is a very small unit, and therefore the value is in the power of 10−24−24^{-24}, which is a very small value. From here, we see that the moving cricket ball is a particle.

Now, the question arises if this ball has a wave nature or not. Your answer will be a big no because the value of λBALL is immeasurable. This proves that de Broglie’s theory of wave-particle duality is valid for the moving objects ‘up to’ the size (not equal to the size) of the electrons.

De Broglie Wavelength for an Electron

We know that me = 9.1 x 10 to power of -31 kg

and ve = 218 x 10 to power of -6 m/s

Now, putting these values in the equation λ = h/mv, which yields λ = 3.2 Å.

This value is measurable. Therefore, we can say that electrons have wave-particle duality. Thus all the big objects have a wave nature and microscopic objects like electrons have wave-particle nature.

E = hν = \[\frac{hc}{\lambda }\]

The Conclusion of De Broglie Hypothesis

From de Broglie equation for a material particle, i.e.,

λ = \[\frac{h}{p}\]or \[\frac{h}{mv}\], we conclude the following:

i. If v = 0, then λ = ∞, and

If v = ∞, then λ = 0

It means that waves are associated with the moving material particles only. This implies these waves are independent of their charge.

FAQs on De Broglie Equation

1.The De Broglie hypothesis was confirmed through which means?

De Broglie had not proved the validity of his hypothesis on his own, it was merely a hypothetical assumption before it was tested out and consequently, it was found that all substances in the universe have wave-particle duality. A number of experiments were conducted with Fresnel diffraction as well as a specular reflection of neutral atoms. These experiments proved the validity of De Broglie’s statements and made his hypothesis come true. These experiments were conducted by some of his students.

2.What exactly does the De Broglie equation apply to?

In very broad terms, this applies to pretty much everything in the tangible universe. This means that people, non-living things, trees and animals, all of these come under the purview of the hypothesis. Any particle of any substance that has matter and has linear momentum also is a wave. The wavelength will be inversely related to the magnitude of the linear momentum of the particle. Therefore, everything in the universe that has matter, is applicable to fit under the De Broglie equation.

3.Is it possible that a single photon also has a wavelength?

When De Broglie had proposed his hypothesis, he derived from the work of Planck that light is made up of small pockets that have a certain energy, known as photons. For his own hypothesis, he said that all things in the universe that have to matter have wave-particle duality, and therefore, wavelength. This extends to light as well, since it was proved that light is made up of matter (photons). Hence, it is true that even a single photon has a wavelength.

4.Are there any practical applications of the De Broglie equation?

It would be wrong to say that people use this equation in their everyday lives, because they do not, not in the literal sense at least. However, practical applications do not only refer to whether they can tangibly be used by everyone. The truth of the De Broglie equation lies in the fact that we, as human beings, also are made of matter and thus we also have wave-particle duality. All the things we work with have wave-particle duality.

5.Does the De Broglie equation apply to an electron?

Yes, this equation is applicable for every single moving body in the universe, down to the smallest subatomic levels. Just how light particles like photons have their own wavelengths, it is also true for an electron. The equation treats electrons as both waves as well as particles, only then will it have wave-particle duality. For every electron of every atom of every element, this stands true and using the equation mentioned, the wavelength of an electron can also be calculated.

6.Derive the relation between De Broglie wavelength and temperature.

We know that the average KE of a particle is:

K = 3/2 k b T

Where k b is Boltzmann’s constant, and

T = temperature in Kelvin

The kinetic energy of a particle is ½ mv²

The momentum of a particle, p = mv = √2mK

= √2m(3/2)KbT = √2mKbT

de Broglie wavelength, λ = h/p = h√2mkbT

7.If an electron behaves like a wave, what should determine its wavelength and frequency?

Momentum and energy determine the wavelength and frequency of an electron.

8. Find λ associated with an H 2 of mass 3 a.m.u moving with a velocity of 4 km/s.

Here, v = 4 x 10³ m/s

Mass of hydrogen = 3 a.m.u = 3 x 1.67 x 10⁻²⁷kg = 5 x 10⁻²⁷kg

On putting these values in the equation λ = h/mv we get

λ = (6.626 x 10⁻³⁴)/(4 x 10³ x 5 x 10⁻²⁷) = 3 x 10⁻¹¹ m.

9. If the KE of an electron increases by 21%, find the percentage change in its De Broglie wavelength.

We know that λ = h/√2mK

So, λ i = h/√(2m x 100) , and λ f = h/√(2m x 121)

% change in λ is:

Change in wavelength/Original x 100 = (λ fi - λ f )/λ i = ((h/√2m)(1/10 - 1/21))/(h/√2m)(1/10)

On solving, we get

% change in λ = 5.238 %

Reset password New user? Sign up

Existing user? Log in

De Broglie Hypothesis

Already have an account? Log in here.

Today we know that every particle exhibits both matter and wave nature. This is called wave-particle duality . The concept that matter behaves like wave is called the de Broglie hypothesis , named after Louis de Broglie, who proposed it in 1924.

De Broglie Equation

Explanation of bohr's quantization rule.

De Broglie gave the following equation which can be used to calculate de Broglie wavelength, \(\lambda\), of any massed particle whose momentum is known:

\[\lambda = \frac{h}{p},\]

where \(h\) is the Plank's constant and \(p\) is the momentum of the particle whose wavelength we need to find.

With some modifications the following equation can also be written for velocity \((v)\) or kinetic energy \((K)\) of the particle (of mass \(m\)):

\[\lambda = \frac{h}{mv} = \frac{h}{\sqrt{2mK}}.\]

Notice that for heavy particles, the de Broglie wavelength is very small, in fact negligible. Hence, we can conclude that though heavy particles do exhibit wave nature, it can be neglected as it's insignificant in all practical terms of use.

Calculate the de Broglie wavelength of a golf ball whose mass is 40 grams and whose velocity is 6 m/s. We have \[\lambda = \frac{h}{mv} = \frac{6.63 \times 10^{-34}}{40 \times 10^{-3} \times 6} \text{ m}=2.76 \times 10^{-33} \text{ m}.\ _\square\]

One of the main limitations of Bohr's atomic theory was that no justification was given for the principle of quantization of angular momentum. It does not explain the assumption that why an electron can rotate only in those orbits in which the angular momentum of the electron, \(mvr,\) is a whole number multiple of \( \frac{h}{2\pi} \).

De Broglie successfully provided the explanation to Bohr's assumption by his hypothesis.

Problem Loading...

Note Loading...

Set Loading...

6.5 De Broglie’s Matter Waves

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe de Broglie’s hypothesis of matter waves

- Explain how the de Broglie’s hypothesis gives the rationale for the quantization of angular momentum in Bohr’s quantum theory of the hydrogen atom

- Describe the Davisson–Germer experiment

- Interpret de Broglie’s idea of matter waves and how they account for electron diffraction phenomena

Compton’s formula established that an electromagnetic wave can behave like a particle of light when interacting with matter. In 1924, Louis de Broglie proposed a new speculative hypothesis that electrons and other particles of matter can behave like waves. Today, this idea is known as de Broglie’s hypothesis of matter waves . In 1926, De Broglie’s hypothesis, together with Bohr’s early quantum theory, led to the development of a new theory of wave quantum mechanics to describe the physics of atoms and subatomic particles. Quantum mechanics has paved the way for new engineering inventions and technologies, such as the laser and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). These new technologies drive discoveries in other sciences such as biology and chemistry.

According to de Broglie’s hypothesis, massless photons as well as massive particles must satisfy one common set of relations that connect the energy E with the frequency f , and the linear momentum p with the wavelength λ . λ . We have discussed these relations for photons in the context of Compton’s effect. We are recalling them now in a more general context. Any particle that has energy and momentum is a de Broglie wave of frequency f and wavelength λ : λ :

Here, E and p are, respectively, the relativistic energy and the momentum of a particle. De Broglie’s relations are usually expressed in terms of the wave vector k → , k → , k = 2 π / λ , k = 2 π / λ , and the wave frequency ω = 2 π f , ω = 2 π f , as we usually do for waves:

Wave theory tells us that a wave carries its energy with the group velocity . For matter waves, this group velocity is the velocity u of the particle. Identifying the energy E and momentum p of a particle with its relativistic energy m c 2 m c 2 and its relativistic momentum mu , respectively, it follows from de Broglie relations that matter waves satisfy the following relation:

where β = u / c . β = u / c . When a particle is massless we have u = c u = c and Equation 6.57 becomes λ f = c . λ f = c .

Example 6.11

How long are de broglie matter waves.

Depending on the problem at hand, in this equation we can use the following values for hc : h c = ( 6.626 × 10 −34 J · s ) ( 2.998 × 10 8 m/s ) = 1.986 × 10 −25 J · m = 1.241 eV · μ m h c = ( 6.626 × 10 −34 J · s ) ( 2.998 × 10 8 m/s ) = 1.986 × 10 −25 J · m = 1.241 eV · μ m

- For the basketball, the kinetic energy is K = m u 2 / 2 = ( 0.65 kg ) ( 10 m/s ) 2 / 2 = 32.5 J K = m u 2 / 2 = ( 0.65 kg ) ( 10 m/s ) 2 / 2 = 32.5 J and the rest mass energy is E 0 = m c 2 = ( 0.65 kg ) ( 2.998 × 10 8 m/s ) 2 = 5.84 × 10 16 J. E 0 = m c 2 = ( 0.65 kg ) ( 2.998 × 10 8 m/s ) 2 = 5.84 × 10 16 J. We see that K / ( K + E 0 ) ≪ 1 K / ( K + E 0 ) ≪ 1 and use p = m u = ( 0.65 kg ) ( 10 m/s ) = 6.5 J · s/m : p = m u = ( 0.65 kg ) ( 10 m/s ) = 6.5 J · s/m : λ = h p = 6.626 × 10 −34 J · s 6.5 J · s/m = 1.02 × 10 −34 m . λ = h p = 6.626 × 10 −34 J · s 6.5 J · s/m = 1.02 × 10 −34 m .

- For the nonrelativistic electron, E 0 = m c 2 = ( 9.109 × 10 −31 kg ) ( 2.998 × 10 8 m/s ) 2 = 511 keV E 0 = m c 2 = ( 9.109 × 10 −31 kg ) ( 2.998 × 10 8 m/s ) 2 = 511 keV and when K = 1.0 eV , K = 1.0 eV , we have K / ( K + E 0 ) = ( 1 / 512 ) × 10 −3 ≪ 1 , K / ( K + E 0 ) = ( 1 / 512 ) × 10 −3 ≪ 1 , so we can use the nonrelativistic formula. However, it is simpler here to use Equation 6.58 : λ = h p = h c K ( K + 2 E 0 ) = 1.241 eV · μ m ( 1.0 eV ) [ 1.0 eV+ 2 ( 511 keV ) ] = 1.23 nm . λ = h p = h c K ( K + 2 E 0 ) = 1.241 eV · μ m ( 1.0 eV ) [ 1.0 eV+ 2 ( 511 keV ) ] = 1.23 nm . If we use nonrelativistic momentum, we obtain the same result because 1 eV is much smaller than the rest mass of the electron.

- For a fast electron with K = 108 keV, K = 108 keV, relativistic effects cannot be neglected because its total energy is E = K + E 0 = 108 keV + 511 keV = 619 keV E = K + E 0 = 108 keV + 511 keV = 619 keV and K / E = 108 / 619 K / E = 108 / 619 is not negligible: λ = h p = h c K ( K + 2 E 0 ) = 1.241 eV · μm 108 keV [ 108 keV + 2 ( 511 keV ) ] = 3.55 pm . λ = h p = h c K ( K + 2 E 0 ) = 1.241 eV · μm 108 keV [ 108 keV + 2 ( 511 keV ) ] = 3.55 pm .

Significance

Check your understanding 6.11.

What is de Broglie’s wavelength of a nonrelativistic proton with a kinetic energy of 1.0 eV?

Using the concept of the electron matter wave, de Broglie provided a rationale for the quantization of the electron’s angular momentum in the hydrogen atom, which was postulated in Bohr’s quantum theory. The physical explanation for the first Bohr quantization condition comes naturally when we assume that an electron in a hydrogen atom behaves not like a particle but like a wave. To see it clearly, imagine a stretched guitar string that is clamped at both ends and vibrates in one of its normal modes. If the length of the string is l ( Figure 6.18 ), the wavelengths of these vibrations cannot be arbitrary but must be such that an integer k number of half-wavelengths λ / 2 λ / 2 fit exactly on the distance l between the ends. This is the condition l = k λ / 2 l = k λ / 2 for a standing wave on a string. Now suppose that instead of having the string clamped at the walls, we bend its length into a circle and fasten its ends to each other. This produces a circular string that vibrates in normal modes, satisfying the same standing-wave condition, but the number of half-wavelengths must now be an even number k , k = 2 n , k , k = 2 n , and the length l is now connected to the radius r n r n of the circle. This means that the radii are not arbitrary but must satisfy the following standing-wave condition:

If an electron in the n th Bohr orbit moves as a wave, by Equation 6.59 its wavelength must be equal to λ = 2 π r n / n . λ = 2 π r n / n . Assuming that Equation 6.58 is valid, the electron wave of this wavelength corresponds to the electron’s linear momentum, p = h / λ = n h / ( 2 π r n ) = n ℏ / r n . p = h / λ = n h / ( 2 π r n ) = n ℏ / r n . In a circular orbit, therefore, the electron’s angular momentum must be

This equation is the first of Bohr’s quantization conditions, given by Equation 6.36 . Providing a physical explanation for Bohr’s quantization condition is a convincing theoretical argument for the existence of matter waves.

Example 6.12

The electron wave in the ground state of hydrogen, check your understanding 6.12.

Find the de Broglie wavelength of an electron in the third excited state of hydrogen.

Experimental confirmation of matter waves came in 1927 when C. Davisson and L. Germer performed a series of electron-scattering experiments that clearly showed that electrons do behave like waves. Davisson and Germer did not set up their experiment to confirm de Broglie’s hypothesis: The confirmation came as a byproduct of their routine experimental studies of metal surfaces under electron bombardment.

In the particular experiment that provided the very first evidence of electron waves (known today as the Davisson–Germer experiment ), they studied a surface of nickel. Their nickel sample was specially prepared in a high-temperature oven to change its usual polycrystalline structure to a form in which large single-crystal domains occupy the volume. Figure 6.19 shows the experimental setup. Thermal electrons are released from a heated element (usually made of tungsten) in the electron gun and accelerated through a potential difference Δ V , Δ V , becoming a well-collimated beam of electrons produced by an electron gun. The kinetic energy K of the electrons is adjusted by selecting a value of the potential difference in the electron gun. This produces a beam of electrons with a set value of linear momentum, in accordance with the conservation of energy:

The electron beam is incident on the nickel sample in the direction normal to its surface. At the surface, it scatters in various directions. The intensity of the beam scattered in a selected direction φ φ is measured by a highly sensitive detector. The detector’s angular position with respect to the direction of the incident beam can be varied from φ = 0 ° φ = 0 ° to φ = 90 ° . φ = 90 ° . The entire setup is enclosed in a vacuum chamber to prevent electron collisions with air molecules, as such thermal collisions would change the electrons’ kinetic energy and are not desirable.

When the nickel target has a polycrystalline form with many randomly oriented microscopic crystals, the incident electrons scatter off its surface in various random directions. As a result, the intensity of the scattered electron beam is much the same in any direction, resembling a diffuse reflection of light from a porous surface. However, when the nickel target has a regular crystalline structure, the intensity of the scattered electron beam shows a clear maximum at a specific angle and the results show a clear diffraction pattern (see Figure 6.20 ). Similar diffraction patterns formed by X-rays scattered by various crystalline solids were studied in 1912 by father-and-son physicists William H. Bragg and William L. Bragg . The Bragg law in X-ray crystallography provides a connection between the wavelength λ λ of the radiation incident on a crystalline lattice, the lattice spacing, and the position of the interference maximum in the diffracted radiation (see Diffraction ).

The lattice spacing of the Davisson–Germer target, determined with X-ray crystallography, was measured to be a = 2.15 Å . a = 2.15 Å . Unlike X-ray crystallography in which X-rays penetrate the sample, in the original Davisson–Germer experiment, only the surface atoms interact with the incident electron beam. For the surface diffraction, the maximum intensity of the reflected electron beam is observed for scattering angles that satisfy the condition n λ = a sin φ n λ = a sin φ (see Figure 6.21 ). The first-order maximum (for n = 1 n = 1 ) is measured at a scattering angle of φ ≈ 50 ° φ ≈ 50 ° at Δ V ≈ 54 V , Δ V ≈ 54 V , which gives the wavelength of the incident radiation as λ = ( 2.15 Å ) sin 50 ° = 1.64 Å . λ = ( 2.15 Å ) sin 50 ° = 1.64 Å . On the other hand, a 54-V potential accelerates the incident electrons to kinetic energies of K = 54 eV . K = 54 eV . Their momentum, calculated from Equation 6.61 , is p = 2.478 × 10 −5 eV · s / m . p = 2.478 × 10 −5 eV · s / m . When we substitute this result in Equation 6.58 , the de Broglie wavelength is obtained as

The same result is obtained when we use K = 54 eV K = 54 eV in Equation 6.61 . The proximity of this theoretical result to the Davisson–Germer experimental value of λ = 1.64 Å λ = 1.64 Å is a convincing argument for the existence of de Broglie matter waves.

Diffraction lines measured with low-energy electrons, such as those used in the Davisson–Germer experiment, are quite broad (see Figure 6.20 ) because the incident electrons are scattered only from the surface. The resolution of diffraction images greatly improves when a higher-energy electron beam passes through a thin metal foil. This occurs because the diffraction image is created by scattering off many crystalline planes inside the volume, and the maxima produced in scattering at Bragg angles are sharp (see Figure 6.22 ).

Since the work of Davisson and Germer, de Broglie’s hypothesis has been extensively tested with various experimental techniques, and the existence of de Broglie waves has been confirmed for numerous elementary particles. Neutrons have been used in scattering experiments to determine crystalline structures of solids from interference patterns formed by neutron matter waves. The neutron has zero charge and its mass is comparable with the mass of a positively charged proton. Both neutrons and protons can be seen as matter waves. Therefore, the property of being a matter wave is not specific to electrically charged particles but is true of all particles in motion. Matter waves of molecules as large as carbon C 60 C 60 have been measured. All physical objects, small or large, have an associated matter wave as long as they remain in motion. The universal character of de Broglie matter waves is firmly established.

Example 6.13

Neutron scattering.

We see that p 2 c 2 ≪ E 0 2 p 2 c 2 ≪ E 0 2 so K ≪ E 0 K ≪ E 0 and we can use the nonrelativistic kinetic energy:

Kinetic energy of ideal gas in equilibrium at 300 K is:

We see that these energies are of the same order of magnitude.

Example 6.14

Wavelength of a relativistic proton, check your understanding 6.13.

Find the de Broglie wavelength and kinetic energy of a free electron that travels at a speed of 0.75 c .

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/university-physics-volume-3/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Samuel J. Ling, Jeff Sanny, William Moebs

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: University Physics Volume 3

- Publication date: Sep 29, 2016

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/university-physics-volume-3/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/university-physics-volume-3/pages/6-5-de-broglies-matter-waves

© Jan 19, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- Why Does Water Expand When It Freezes

- Gold Foil Experiment

- Faraday Cage

- Oil Drop Experiment

- Magnetic Monopole

- Why Do Fireflies Light Up

- Types of Blood Cells With Their Structure, and Functions

- The Main Parts of a Plant With Their Functions

- Parts of a Flower With Their Structure and Functions

- Parts of a Leaf With Their Structure and Functions

- Why Does Ice Float on Water

- Why Does Oil Float on Water

- How Do Clouds Form

- What Causes Lightning

- How are Diamonds Made

- Types of Meteorites

- Types of Volcanoes

- Types of Rocks

de Broglie Wavelength

The de Broglie wavelength is a fundamental concept in quantum mechanics that profoundly explains particle behavior at the quantum level. According to de Broglie hypothesis, particles like electrons, atoms, and molecules exhibit wave-like and particle-like properties.

This concept was introduced by French physicist Louis de Broglie in his doctoral thesis in 1924, revolutionizing our understanding of the nature of matter.

de Broglie Equation

A fundamental equation core to de Broglie hypothesis establishes the relationship between a particle’s wavelength and momentum . This equation is the cornerstone of quantum mechanics and sheds light on the wave-particle duality of matter. It revolutionizes our understanding of the behavior of particles at the quantum level. Here are some of the critical components of the de Broglie wavelength equation:

1. Planck’s Constant (h)

Central to this equation is Planck’s constant , denoted as “h.” Planck’s constant is a fundamental constant of nature, representing the smallest discrete unit of energy in quantum physics. Its value is approximately 6.626 x 10 -34 Jˑs. Planck’s constant relates the momentum of a particle to its corresponding wavelength, bridging the gap between classical and quantum physics.

2. Particle Momentum (p)

The second critical component of the equation is the particle’s momentum, denoted as “p”. Momentum is a fundamental property of particles in classical physics, defined as the product of an object’s mass (m) and its velocity (v). In quantum mechanics, however, momentum takes on a slightly different form. It is the product of the particle’s mass and its velocity, adjusted by the de Broglie wavelength.

The mathematical formulation of de Broglie wavelength is

We can replace the momentum by p = mv to obtain

The SI unit of wavelength is meter or m. Another commonly used unit is nanometer or nm.

This equation tells us that the wavelength of a particle is inversely proportional to its mass and velocity. In other words, as the mass of a particle increases or its velocity decreases, its de Broglie wavelength becomes shorter, and it behaves more like a classical particle. Conversely, as the mass decreases or velocity increases, the wavelength becomes longer, and the particle exhibits wave-like behavior. To grasp the significance of this equation, let us consider the example of an electron .

de Broglie Wavelength of Electron

Electrons are incredibly tiny and possess a minimal mass. As a result, when they are accelerated, such as when they move around the nucleus of an atom , their velocities can become significant fractions of the speed of light, typically ~1%.

Consider an electron moving at 2 x 10 6 m/s. The rest mass of an electron is 9.1 x 10 -31 kg. Therefore,

These short wavelengths are in the range of the sizes of atoms and molecules, which explains why electrons can exhibit wave-like interference patterns when interacting with matter, a phenomenon famously observed in the double-slit experiment.

Thermal de Broglie Wavelength

The thermal de Broglie wavelength is a concept that emerges when considering particles in a thermally agitated environment, typically at finite temperatures. In classical physics, particles in a gas undergo collision like billiard balls. However, particles exhibit wave-like behavior at the quantum level, including wave interference phenomenon. The thermal de Broglie wavelength considers the kinetic energy associated with particles due to their thermal motion.

At finite temperatures, particles within a system possess a range of energies described by the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. Some particles have relatively high energies, while others have low energies. The thermal de Broglie wavelength accounts for this distribution of kinetic energies. It helps to understand the statistical behavior of particles within a thermal ensemble.

Mathematical Expression

The thermal de Broglie wavelength (λ th ) is determined by incorporating both the mass (m) of the particle and its thermal kinetic energy (kT) into the de Broglie wavelength equation:

Here, k is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the temperature in Kelvin.

- de Broglie Wave Equation – Chem.libretexts.org

- de Broglie Wavelength – Spark.iop.org

- de Broglie Matter Waves – Openstax.org

- Wave Nature of Electron – Hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu

Article was last reviewed on Friday, October 6, 2023

Related articles

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Popular Articles

Join our Newsletter

Fill your E-mail Address

Related Worksheets

- Privacy Policy

© 2024 ( Science Facts ). All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited.

de Broglie Equation Definition

Chemistry Glossary Definition of de Broglie Equation

- Chemical Laws

- Periodic Table

- Projects & Experiments

- Scientific Method

- Biochemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Medical Chemistry

- Chemistry In Everyday Life

- Famous Chemists

- Activities for Kids

- Abbreviations & Acronyms

- Weather & Climate

- Ph.D., Biomedical Sciences, University of Tennessee at Knoxville

- B.A., Physics and Mathematics, Hastings College

In 1924, Louis de Broglie presented his research thesis, in which he proposed electrons have properties of both waves and particles, like light. He rearranged the terms of the Plank-Einstein relation to apply to all types of matter.

The de Broglie equation is an equation used to describe the wave properties of matter , specifically, the wave nature of the electron : λ = h/mv , where λ is wavelength, h is Planck's constant, m is the mass of a particle, moving at a velocity v. de Broglie suggested that particles can exhibit properties of waves.

The de Broglie hypothesis was verified when matter waves were observed in George Paget Thomson's cathode ray diffraction experiment and the Davisson-Germer experiment, which specifically applied to electrons. Since then, the de Broglie equation has been shown to apply to elementary particles, neutral atoms, and molecules.

- De Broglie Hypothesis

- Wave-Particle Duality - Definition

- Wave Particle Duality and How It Works

- De Broglie Wavelength Example Problem

- Photon Definition

- Chemistry Timeline

- Erwin Schrödinger and the Schrödinger's Cat Thought Experiment

- What Is a Photon in Physics?

- J.J. Thomson Atomic Theory and Biography

- What is a Wave Function?

- What Is the Definition of "Matter" in Physics?

- Mathematical Properties of Waves

- Topics Typically Covered in Grade 11 Chemistry

- Top 10 Weird but Cool Physics Ideas

- A to Z Chemistry Dictionary

- Electron Definition: Chemistry Glossary

de Broglie equation, derivation, and its Significance

- November 10, 2021

- Atomic Structure

Table of Contents

In 1905, Albert Einstein proposed that light can behave both as a wave and as a particle, implying that it has a dual character. The French physicist Louis de Broglie suggested (1924) a hypothesis to explain the theory of atomic structure, and is therefore the hypothesis is also referred to as the de Broglie hypothesis. The de Broglie hypothesis states that any moving particle/object is associated with both the wave properties as well as particle properties . Later on, Davisson and Germer proved the hypothesis experimentally while studying the diffraction of electrons.

de Broglie Equation Definition

According to de Broglie equation/hypothesis, “ a matter particle in motion is also associated with waves .” In other words, any moving microscopic or macroscopic particle will be associated with a wave character. Such waves are also called matter waves or de Broglie waves. de Broglie equation is basically used to define the wave properties of matter/electron. Thus, the matter particle-like electrons show dual character i.e. it behaves like a particle as well as a wave.

According to de-Broglie, the particle with wavelength and mass ‘m’ moving with velocity ‘v’ is represented by the relation:

de Broglie wave equation derivation

de Broglie equation significance

The de-Broglie equation is significant only for sub-microscopic objects in the range of atoms, molecules, or smaller sub-atomic particles. The wave nature of matter, on the other hand, has no meaning for ordinary-sized objects because the wavelength of the wave associated with them is too small to detect.

de Broglie Hypothesis video

What is h in de broglie equation?

h in de Broglie equation is Planck’s constant having a value of 6.62607 x 10 -34 J s

What is the significance of de Broglie equation?

The de-Broglie equation is significant only for sub-microscopic particles that are in the range of atoms, molecules, or smaller sub-atomic particles.

Derive de Broglie equation for microscopic particle.

According to de Broglie equation/hypothesis, “ a matter particle in motion is also associated with waves.”

Share this to:

- Tags: Atomic Structure , de Broglie equation , de Broglie equation definition chemistry , de Broglie equation derivation , de Broglie equation significance , de Broglie hypothesis , de Broglie wave equation , de Broglie wave equation derivation , de Broglie wavelength equation

You may also like to read:

Balancing Redox Equations by Oxidation Number method

Lead: Properties, 7 Important Uses, Health Effects and Symptoms

Zinc – Chemistry, Deficiency, Side Effects, and its 4 important Health Benefits

Group 13 Elements: Boron Family- Easy Explanation

What is Activated complex? Easy Explanation

Ortho hydrogen and Para Hydrogen: Difference, interconversion

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Top Universities in the USA for Undergraduate and Graduate Chemistry Courses

Preparation of Phthalimide from Phthalic acid by two-step synthesis: Useful Lab Report

Feel Good Hormones: Dopamine, Oxytocin, Serotonin, and Endorphin

Invisible ink: Chemistry, Properties, and 3 Reliable Application

Pyrrole Disorder: Symptoms, Causes, and Treatment

The Chemistry of Mehendi: Composition, Side effects, and Reliable Application

How to Balance Redox Equations Using a Redox Reaction Calculator

Sugar Vs Jaggery: Differences, Calories And Many more

Centrifugation: Definition, Principle, Types, and 3 Reliable Application

Eppendorf Tube: Definition, Types, and Reliable Uses

Litmus Paper: Definition, Chemistry, Test, and 4 important Applications

Our mission is to provide free, world-class Chemisry Notes to Students, anywhere in the world.

Chemist Notes | Chemistry Notes for All | 2024 - Copyright©️ ChemistNotes.com

What is De Broglie Hypothesis?

De broglie's hypothesis says that matter consists of both the particle nature as well as wave nature. de broglie wavelength λ is given as λ = h p , where p represents the particle momentum and can be written as: λ = h m v where, h is the planck's constant, m is the mass of the particle, and v is the velocity of the particle. from the above relation, it can be said that the wavelength of the matter is inversely proportional to the magnitude of the particle's linear momentum. this relation is applicable to both microscopic and macroscopic particles the de broglie equation is one of the equations that is commonly used to define the wave properties of matter. electromagnetic radiation exhibits the dual nature of a particle (having a momentum) and wave (expressed in frequency, and wavelength)..

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.7: de Broglie Waves can be Experimentally Observed

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 210781

Learning Objectives

- To present the experimental evidence behind the wave-particle duality of matter

The validity of de Broglie’s proposal was confirmed by electron diffraction experiments of G.P. Thomson in 1926 and of C. Davisson and L. H. Germer in 1927. In these experiments it was found that electrons were scattered from atoms in a crystal and that these scattered electrons produced an interference pattern. The interference pattern was just like that produced when water waves pass through two holes in a barrier to generate separate wave fronts that combine and interfere with each other. These diffraction patterns are characteristic of wave-like behavior and are exhibited by both matter (e.g., electrons and neutrons) and electromagnetic radiation. Diffraction patterns are obtained if the wavelength is comparable to the spacing between scattering centers.

Diffraction occurs when waves encounter obstacles whose size is comparable with its wavelength.

Continuing with our analysis of experiments that lead to the new quantum theory, we now look at the phenomenon of electron diffraction.

Light Diffraction (Young's Double Slit Experiment)

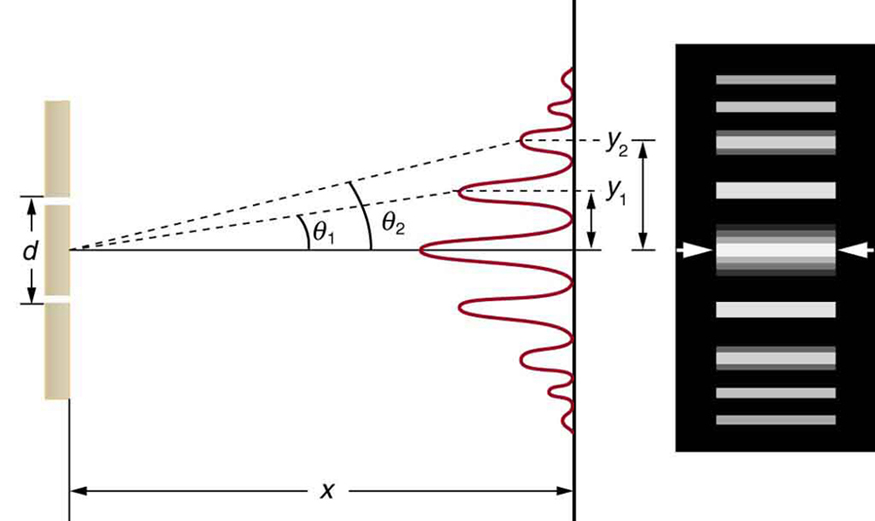

It is well-known that light has the ability to diffract around objects in its path, leading to an interference pattern that is particular to the object. This is, in fact, how holography works (the interference pattern is created by allowing the diffracted light to interfere with the original beam so that the hologram can be viewed by shining the original beam on the image). A simple illustration of light diffraction is the Young double slit experiment (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)).

Interference is a wave phenomenon in which two waves superimpose to form a resultant wave of greater or lower amplitude. It is the primary property used to identify wave behavior.

Here, we use water waves (pictured as waves in a plane parallel to the double slit apparatus) and observe what happens when they impinge on the slits. Each slit then becomes a point source for spherical waves that subsequently interfere with each other, giving rise to the light and dark fringes on the screen at the right (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) ).

Electron Diffraction (Davisson–Germer Experiment)

According to classical physics, electrons should behave like particles - they travel in straight lines and do not curve in flight unless acted on by an external agent, like a magnetic field. In this model, if we fire a beam of electrons through a double slit onto a detector, we should get two bands of "hits", much as you would get if you fired a machine gun at the side of a house with two windows - you would get two areas of bullet-marked wall inside, and the rest would be intact Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) (left).

However, if the slits are made small enough and close enough together, we actually observe the electrons are diffracting through the slits and interfering with each other just like waves. This means that the electrons have wave-particle duality, just like photons, in agreement with de Broglie's hypothesis discussed previously. In this case, they must have properties like wavelength and frequency. We can deduce the properties from the behavior of the electrons as they pass through our diffraction grating.

This was a pivotal result in the development of quantum mechanics. Just as the photoelectric effect demonstrated the particle nature of light, the Davisson–Germer experiment showed the wave-nature of matter, and completed the theory of wave-particle duality. For physicists this idea was important because it meant that not only could any particle exhibit wave characteristics, but that one could use wave equations to describe phenomena in matter if one used the de Broglie wavelength.

Is Matter a Particle or a Wave?

An electron, indeed any particle, is neither a particle nor a wave . Describing the electron as a particle is a mathematical model that works well in some circumstances while describing it as a wave is a different mathematical model that works well in other circumstances. When you choose to do some calculation of the electron's behavior that treats it either as a particle or as a wave, you're not saying the electron is a particle or is a wave: you're just choosing the mathematical model that makes it easiest to do the calculation.

Neutron Diffraction

Like all quantum particles, neutrons can also exhibit wave phenomena and if that wavelength is short enough, atoms or their nuclei can serve as diffraction obstacles. When a beam of neutrons emanating from a reactor is slowed down and selected properly by their speed, their wavelength lies near one angstrom (0.1 nanometer), the typical separation between atoms in a solid material. Such a beam can then be used to perform a diffraction experiment. Neutrons interact directly with the nucleus of the atom, and the contribution to the diffracted intensity depends on each isotope; for example, regular hydrogen and deuterium contribute differently. It is also often the case that light (low Z) atoms contribute strongly to the diffracted intensity even in the presence of large Z atoms.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Neutron Diffraction

Neutrons have no electric charge, so they do not interact with the atomic electrons. Hence, they are very penetrating (e.g., typically 10 cm in lead). Neutron diffraction was proposed in 1934, to exploit de Broglie’s hypothesis about the wave nature of matter. Calculate the momentum and kinetic energy of a neutron whose wavelength is comparable to atomic spacing (\(1.8 \times 10^{-10}\, m\)).

This is a simple use of de Broglie’s equation

\[\lambda = \dfrac{h}{p} \nonumber\]

where we recognize that the wavelength of the neutron must be comparable to atomic spacing (let's assumed equal for convenience, so \(\lambda = 1.8 \times 10^{-10}\, m\)). Rearranging the de Broglie wavelength relationship above to solve for momentum (\(p\)):

\[\begin{align} p &= \dfrac{h}{\lambda} \nonumber \\[4pt] &= \dfrac{6.6 \times 10^{-34} J s}{1.8 \times 10^{-10} m} \nonumber \\[4pt] &= 3.7 \times 10^{-24}\, kg \,\,m\, \,s^{-1} \nonumber \end{align} \nonumber\]

The relationship for kinetic energy is

\[KE = \dfrac{1}{2} mv^2 = \dfrac{p^2}{2m} \nonumber\]

where \(v\) is the velocity of the particle. From the reference table of physical constants , the mass of a neutron is \(1.6749273 \times 10^{−27}\, kg\), so

\[\begin{align*} KE &= \dfrac{(3.7 \times 10^{-24}\, kg \,\,m\, \,s^{-1} )^2}{2 (1.6749273 \times 10^{−27}\, kg)} \\ &=4.0 \times 10^{-21} J \end{align*}\]

The neutrons released in nuclear fission are ‘fast’ neutrons, i.e. much more energetic than this. Their wavelengths be much smaller than atomic dimensions and will not be useful for neutron diffraction. We slow down these fast neutrons by introducing a "moderator", which is a material (e.g., graphite) that neutrons can penetrate, but will slow down appreciable.

Contributors

Michael Fowler (Beams Professor, Department of Physics , University of Virginia)

Mark Tuckerman ( New York University )

- John Rennie (StackExchange)

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Compton's formula established that an electromagnetic wave can behave like a particle of light when interacting with matter. In 1924, Louis de Broglie proposed a new speculative hypothesis that electrons and other particles of matter can behave like waves. Today, this idea is known as de Broglie's hypothesis of matter waves.In 1926, De Broglie's hypothesis, together with Bohr's early ...

This equation relating the momentum of a particle with its wavelength is the de Broglie equation, and the wavelength calculated using this relation is the de Broglie wavelength. Relation between de Broglie Equation and Bohr's Hypothesis of Atom. Bohr postulated that the angular momentum of an electron revolving around the nucleus is quantized ...

The wavelength is known as the de Broglie wavelength. For an electron, de Broglie wavelength equation is: λ = h mv. Here, λ points to the wave of the electron in question. M is the mass of the electron. V is the velocity of the electron. Mv is the momentum that is formed as a result.

Today we know that every particle exhibits both matter and wave nature. This is called wave-particle duality. The concept that matter behaves like wave is called the de Broglie hypothesis, named after Louis de Broglie, who proposed it in 1924. De Broglie gave the following equation which can be used to calculate de Broglie wavelength, ...

Compton's formula established that an electromagnetic wave can behave like a particle of light when interacting with matter. In 1924, Louis de Broglie proposed a new speculative hypothesis that electrons and other particles of matter can behave like waves. Today, this idea is known as de Broglie's hypothesis of matter waves.In 1926, De Broglie's hypothesis, together with Bohr's early ...

The de Broglie hypothesis showed that wave-particle duality was not merely an aberrant behavior of light, but rather was a fundamental principle exhibited by both radiation and matter. As such, it becomes possible to use wave equations to describe material behavior, so long as one properly applies the de Broglie wavelength.

A fundamental equation core to de Broglie hypothesis establishes the relationship between a particle's wavelength and momentum.This equation is the cornerstone of quantum mechanics and sheds light on the wave-particle duality of matter. It revolutionizes our understanding of the behavior of particles at the quantum level.

To calculate the de Broglie wavelength (Equation 4.5.1 ), the momentum of the particle must be established and requires knowledge of both the mass and velocity of the particle. The mass of an electron is 9.109383 × 10 − 28 g and the velocity is obtained from the given kinetic energy of 1000 eV: KE = mv2 2 = p2 2m = 1000 eV.

While this equation was specifically for waves, de Broglie, using his hypothesis that particles can act like waves, combined the equations: E = m c 2 = h ν. Where E is energy, m is mass, c is the ...

Matter waves are a central part of the theory of quantum mechanics, being half of wave-particle duality.At all scales where measurements have been practical, matter exhibits wave-like behavior.For example, a beam of electrons can be diffracted just like a beam of light or a water wave.. The concept that matter behaves like a wave was proposed by French physicist Louis de Broglie (/ d ə ˈ b ...

Also, Einstein's theory of relativity blurs the distinction between particles and radiation by stating that energy carried by the mass of particles can be converted into radiation ( E= mc2), which found a dramatic con rmation in the discovery of nuclear reactions. De Broglie's postulate Radiation can behave like matter.

The de Broglie equation is an equation used to describe the wave properties of matter, specifically, the wave nature of the electron : . λ = h/mv, where λ is wavelength, h is Planck's constant, m is the mass of a particle, moving at a velocity v. de Broglie suggested that particles can exhibit properties of waves.

The expression for the de-Broglie wavelength of an electron, λ = h 2 m K. If the electron having a charge e is moving under an external potential V, then, The kinetic energy of the electron, K = eV. Substituting this expression in the above equation, λ = h 2 m e V. Put, h = 6.62607 × 10 − 34 Js. e = 1.6 × 10 − 19 C.

Heisenberg's Uncertainty. The Davisson-Germer experiment proved beyond doubt the wave nature of matter by diffracting electrons through a crystal. In 1929, de Broglie was awarded the Nobel Prize for his matter wave theory and for opening up a whole new field of Quantum Physics. The matter-wave theory was gracefully incorporated by Heisenberg ...

The de Broglie hypothesis states that any moving particle/object is associated with both the wave properties as well as particle properties. Later on, Davisson and Germer proved the hypothesis experimentally while studying the diffraction of electrons. de Broglie Equation Definition. According to de Broglie equation/hypothesis, "a matter ...

The above equation is known as de Broglie relationship and the wavelength, λ is known as de Broglie wavelength. Diffraction of electron beams explains the de Broglie relationship as diffraction is the property of waves. An electron microscope is a common instrument illustrating this fact. Thus, every object in motion has a wavelike character.

The de Broglie‐Bohr model of the hydrogen atom presented here treats the electron as a particle on a ring with wave‐like properties. λ = h mev λ = h m e v. de Broglie's hypothesis that matter has wave-like properties. nλ = 2πr n λ = 2 π r. The consequence of de Broglieʹs hypothesis; an integral number of wavelengths must fit within ...

De Broglie's Hypothesis says that Matter consists of both the particle nature as well as wave nature. De Broglie wavelength λ is given as λ = h p, where p represents the particle momentum and can be written as: λ = h m v Where, h is the Planck's constant, m is the mass of the particle, and v is the velocity of the particle.; From the above relation, it can be said that the wavelength of the ...

Solution. This is a simple use of de Broglie's equation. λ = h p λ = h p. where we recognize that the wavelength of the neutron must be comparable to atomic spacing (let's assumed equal for convenience, so λ = 1.8 ×10−10 m λ = 1.8 × 10 − 10 m ). Rearranging the de Broglie wavelength relationship above to solve for momentum ( p p ...