- Open access

- Published: 06 March 2020

Transition towards green banking: role of financial regulators and financial institutions

- Hyoungkun Park 1 , 2 &

- Jong Dae Kim 3

Asian Journal of Sustainability and Social Responsibility volume 5 , Article number: 5 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

76k Accesses

104 Citations

14 Altmetric

Metrics details

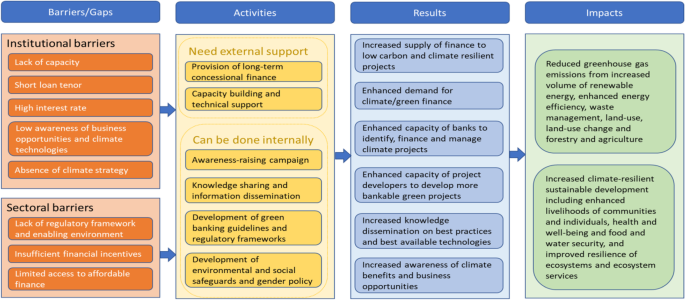

This paper provides an overview of green banking as an emerging area of creating competitive advantages and new business opportunities for private sector banks and expanding the mandate of central banks and supervisors to protect the financial system and manage risks of individual financial institutions. Climate change is expected to accelerate and is no longer considered only as an environmental threat because it affects all economic sectors. Furthermore, climate-related risks are causing physical and transitional risks for the financial sector. To mitigate the negative impacts, central banks, supervisors and policymakers started undertaking various green banking initiatives, although the approach taken so far is slightly different between developed and developing countries. In parallel, both private and public financial institutions, individually and collectively, are trying to address the issues on the horizon especially from a risk management perspective. Particularly, private sector banks have developed climate strategies and rolled out diverse green financial instruments to seize the business opportunities. This paper uses the theory of change conceptual framework at the sectoral, institutional and combined level as a tool to identify barriers in green banking and analyze activities that are needed to mitigate those barriers and to reach desired results and impacts.

Introduction

The latest IPCC report (IPCC 2018 ) reaffirmed that human activities caused global warming and are likely to further accelerate it by reaching 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels between 2030 and 2052 based on a business-as-usual scenario. The IPCC report set highly ambitious targets of reducing global net anthropogenic CO 2 emissions by approximately 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 and reaching net zero around 2050 to meet 1.5 °C of global warming. Limiting global warming to 1.5 °C certainly requires social and business transformations and emissions reductions across all sectors. Whilst the National Climate Assessment (USGCRP 2018 ) was more limited in scope by focusing its findings on the United States, it reached similar conclusions and suggested measures to reduce risks through emissions mitigation and adaptation actions. These findings prove that there is still a long way to go despite negative impacts arising from climate change and global warming (Doran and Zimmerman 2009 ; Cook et al. 2013 ).

To achieve such a structural transformation, the magnitude of the investment required is enormous. The IPCC report projected USD 2.4 trillion in clean energy is needed every year through 2035 and between USD 1.6 and USD 3.8 trillion in energy system supply-side investments every year through 2050, which is equivalent to USD 51.2 and USD 122 trillion exclusively for energy investments. Considering the significant investment needs, the financial sector is expected to play a pivotal role in providing necessary financial resources as it is the backbone of the real economy (OECD 2017 ). The role of the banking sector is central in meeting financial needs of the private sector and delivering credit to households and individuals (Beck and Demirguc-Kunt 2006 ; Wang 2016 ). The banking sector also plays a critical role in supporting a country’s adaptation to climate change and enhancing its financial resilience to climate risks. Banks can help reduce risks associated with climate change and sustainability, mitigate the impact of these risks, adapt to climate change and support recovery by reallocating financing to climate-sensitive sectors.

Climate change is affecting the financial system because of its far-reaching impact across all sectors and geographies, and the high degree of certainty that risks will emerge and have irreversible consequences if no actions are taken today. However, climate-related risks are not yet fully assessed and factored into current valuation of assets (NGFS 2019 ). The role of banks in financing the transition to a green economy is to unlock private investments, to bridge supply and demand while considering the entire spectrum of risks and to evaluate projects from both an economic and environmental perspective (EBF 2017 ). Although several banks have demonstrated their leadership in financing green or climate projects, the green portfolio of most banks is still very low. The International Finance Corporation (IFC) estimated the total green loans and credits of banks in developing countries to the private sector in 2016 to be approximately USD 1.5 trillion, or about 7% of total claims on the private sector in emerging markets (IFC 2018a , 2018b ). This outcome results from both a lack of the necessary regulatory and supervisory framework and failure to integrate environment and climate change risks into banks’ strategies and risk management systems. Additionally, the current financial framework often makes the required investment difficult to be met due to barriers exist at the sectoral and institutional level (Mazzucato and Semieniuk 2018 ). In response to the lack of regulatory and supervisory framework, a growing number of central banks and regulators around the world are becoming aware of their role and potential mandate in addressing climate change and environment risks faced by the banking and financial sector and taking actions (Volz 2017 ). For example, a group of central banks and supervisors launched the Networking for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) in 2017 to contribute to the analysis and management of climate and environment-related risks in the financial sector, and to mobilize mainstream finance to support the transition toward a sustainable economy (NGFS 2018 ). In parallel, more banks, especially private sector commercial banks, have started greening their operations by integrating environmental and climate change risks into their strategies and risk management systems and rolling out green financial products to expand their business horizons.

While green banking is still a new concept in the field of climate finance, it can serve the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)‘s objectives by financing climate change mitigation and adaptation activities in collaboration with the private sector. This paper aims to identify the challenges that climate change presents to the financial sector and describes and analyzes various tools for financial institutions that can help manage climate and credit risks while developing business opportunities in parallel.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 introduces the topic of green banking and reviews the relevant literature. Section 3 shows the green banking initiatives being undertaken by central banks and regulators and recent discussions about the mandates of central banks in their efforts to make the bank’s operations green and sustainable. It will also analyze the key difference in the approaches taken by developed and developing countries. This is followed by a discussion of the range of strategies, policies, tools and instruments that are being adopted and deployed by banks and presents the framework in Section 4. Section 5 introduces the theory of change conceptual framework as a tool to analyze current barriers and gaps, activities to be performed to mitigate the barriers and expected results and impacts that can be created. The final section discusses implications for academia, policy makers and practitioners and provides directions for future research.

Overview of green banking

Definition of green banking.

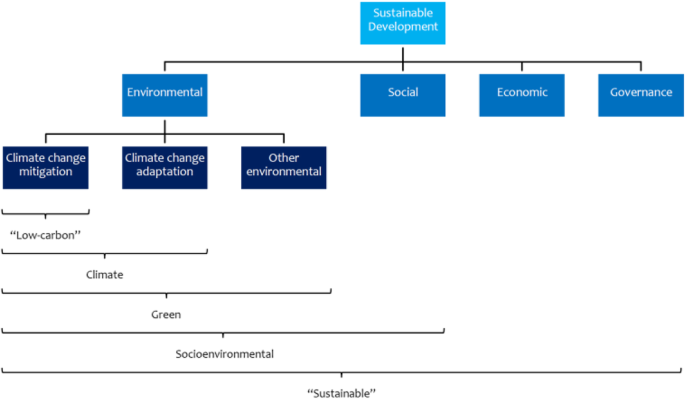

There is no universally accepted definition of green banking (Alexander 2016 ) and it varies widely between countries. However, some researchers and organizations tried to come up with their own definition. The Indian Institute for Development and Research in Banking Technology (IDRBT), which is established by the Reserve Bank of India, defined green banking as an umbrella term referring to practices and guidelines that make banks sustainable in economic, environmental and social dimensions (IDRBT, 2013 ). Green banking is similar to the concept of ethical banking, which starts with the aim of protecting the environment, as it involves promoting environmental and social responsibility while providing excellent banking services (Bihari 2011 ). The State Bank of Pakistan defined green banking as promoting environmentally friendly practices that aid banks and customers in reducing their carbon footprints (SBP 2015 ). Green banking can be also called social or responsible banking because it covers the social responsibility of banks towards environmental protection, illustrating that social issues often intersect with environmental issues. Social banking is broadly defined as addressing some of the most pressing issues of our time and aiming to have a positive impact on people, the environment and culture by meaning of banking (Kaeufer 2010 ; Weber and Remer 2011 ). Similarly, responsible banking encompasses a strong commitment by banks to sustainable development and addressing corporate social responsibility as an integral part of its business activities. Finally, green banking can be a subset of sustainable banking which tends to capture broader environmental and social dimensions (Dufays 2012 ). Global Alliance for Banking on Values (GABV) is an independent network of banks and banking cooperatives with a shared mission to use finance to deliver sustainable economic, social and environmental development. GABV has endorsed the principles of sustainable banking which include triple bottom line approach (social, environmental and financial aspects) at the heart of the business model, grounded in communities and transparent and inclusive governance (GABV 2012 ). There are many overlaps between these definitions and concepts which can be confusing to some extent. To make the scope and definitions a little clearer, UNEP provided a good comparison on respective definitions of green vs. sustainable vs. socioenvironmental (UNEP, 2016 ), as shown in Fig. 1 . According to UNEP, sustainable finance is the most inclusive concept which contains social, environmental and economic aspects while green finance includes climate and other environmental finance but excludes social and economic aspects.

A simplified schema for understanding broad terms. Source: UNEP, 2016

Whilst the definition of green finance in the UNEP paper was used to address environmental concerns in general and therefore became broader than the definition of climate finance, the scope of this paper will only apply to banking activities related to climate change mitigation and adaptation. In this respect, the concept of green banking is similar to that of climate finance defined by the UNFCCC which refers to finance that aims at reducing emissions and enhancing sinks of greenhouse gases and aims at reducing vulnerability of, and maintaining and increasing the resilience of, human and ecological systems to negative climate change impacts. In this paper, green banking is defined as financing activities by banking and non-banking financial institutions with an aim to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and increase the resilience of the society to negative climate change impacts while considering other sustainable development goals such as economic growth, job creation and gender equality.

Need for green banking as a risk assessment and management tool

IPCC rightfully claimed that there is no clear scientific evidence on how the banking sector will be affected by the impacts of climate change (IPCC 2001 ). Whilst there may not be clear scientific evidence, central banks, regulators and the academia have been analyzing the climate change challenges from a financial risk and stability point of view (Kim et al. 2015 ; Carney 2015 ; Battiston et al. 2017 ; Volz 2017 ). Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) within the Bank of England identified two primary financial risk factors associated with climate change: physical and transition (PRA 2018 ). Physical risk is defined as the first-order risks which arise from climate and weather-related events, such as floods, storms, heatwaves, droughts and sea-level rise with the vulnerability of exposure of human and natural systems (PRA 2015 ; Batten et al. 2016 ; PRA 2018 ). Physical risks can lead to higher credit risks and financial losses by impairing asset values. Transition risks are those that can arise while adjusting, frequently in a disorderly fashion, towards a low-carbon economy (Carney 2015 ; Platinga and Scholtens). Given that climate change mitigation actions often require radical changes and adjustments by the public and private sector and households, a large range of assets are at risk of becoming stranded. This is especially prevalent for fossil-fuel related sectors and assets, which as a result of a revaluation, can in turn lead to higher credit exposure for banking and non-banking financial institutions. Additionally, liability risks can be another primary financial risk factor. Liability risks can arise if parties suffering losses from the damages of climate change seek compensation from those they hold accountable (Heede 2014 ; Carney 2015 ). Liability risks can be more relevant to the insurance sector rather than banking sector due their nature and compensation mechanism. The three types of financial risk factors constitute a major threat to the stability of the financial system (Carney 2015 ; Arezki et al. 2016 ; Christophers 2017 ).

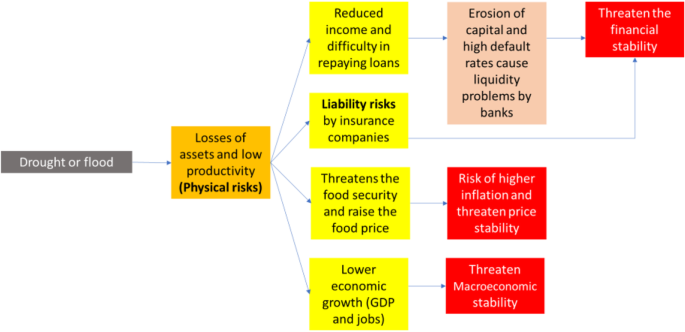

Those risks can come in parallel as they are interdependent. For example, an agriculture-dominated economy can suffer in many ways. Drought or flood, which is a physical risk, can lead to direct losses in agriculture and other agriculture- and food-related value-added sectors. Such a damage in turn can trigger liability risks if their properties were insured. Extreme weather events will not only reduce incomes generated by those sectors but also hamper economic growth by lowering the gross domestic product (GDP) and affecting the job market and thus threaten macroeconomic stability. As a result, affected corporates and individuals may not be able to repay their loans. Once loan default rates increase, banks with heavy agriculture portfolios will suffer. Ultimately, the stability of the whole financial system can be threatened. Additionally, changes in agricultural input can affect food security and food prices which in turn can influence the inflation rate and threaten price stability (Heinen et al. 2016 ). Figure 2 shows an example of climate change affecting in an agriculture-dominant economy.

Climate change effects in an agriculture-dominant economy

For banking and non-banking financial institutions, the transition risks of policy changes can cause more immediate and serious consequences compared to the other two types of financial risks, especially from a credit risk perspective. For example, valuation of collaterals such as land and properties may have to be downgraded if the governments decide to give up on coastal lands and properties vulnerable to sea-level rise for economic reasons or introduce more stringent building energy efficiency standards. Additionally, more extreme hot weather can decrease agricultural productivity leading to lower valuations. Borrowers in the tourism sector relying on coral ecosystems are likely to suffer from a significant decline of coral reefs of 70–90% under a 1.5 °C global warming scenario. Those banks that hold such collaterals and assets would be expected to reserve more capital against them or require more collaterals to offset the shortfall and manage the probability of default and loss-given-default which will become a financial burden by borrowers. Many banks have high exposure to carbon-intensive industries whose business models may not fit into the transition to a low-carbon economy. As a result, the borrowers in the carbon-intensive sector may face challenges in repaying loans due to a decrease in their earnings and asset value. As a result, more banks can be under pressure to shift their investment and lending patterns by divesting from fossil-fuels and investing more in low carbon and energy efficient technologies.

Additionally, the climate risk factors may increase market and operational risks for banks. Market risks can arise from significant fluctuations in energy and commodity prices due to the transition on carbon-intensive industries. Coupled with weakened macroeconomic conditions such as inflation and economic growth, these market risks can increase transaction costs for banks. Banks may also have to bear higher insurance risk premiums on their own assets vulnerable to climate change. Operational risks associated with business continuity can also increase due to climate change and frequency and depth of extreme weather events. For example, banks may have to relocate their headquarters and data centers. Reputational risks by banks could also arise from investing in carbon-intensive assets and borrowers as some might view such activities as breach of fiduciary duty for failing to consider long-term investment value drivers (Table 1 ).

Banks have increasingly started assessing the risks associated with exposure to their loans by adopting risk management frameworks such as the Equator Principles, which are essentially a credit risk management tool that can be used to identify, evaluate and manage environmental and social risks in project finance transactions. However, many frameworks like the Equator Principles are voluntary, legally non-binding industry benchmark and demonstrated inherent limitations including limited scope, a lack of transparency and publicly disclosed information, inadequate monitoring and a lack of accountability, liability, implementation and enforcement (Wörsdörfer 2016 ).

Arguably, the most effective means to address those issues would be to make such tools more enforceable within the boundary of the regulatory and prudential frameworks, assuming that most banks would not voluntarily undertake such measures. However, with exceptions of a few countries such as Bangladesh, China and Indonesia, most countries have just started exploring this possibility. In the case of China, the People’s Bank of China and the China Banking Regulatory Commission developed Green Credit Guidelines based on their Banking Industry Regulation and Administration Law and Commercial Banking Law. China’s Green Credit Guidelines require that banks establish a monitoring and evaluating system for green credit. The effectiveness of such policies is not easy to measure, and they are mostly still in mixed form between voluntary guidelines and enforceable regulations. Nonetheless, even voluntary guidelines can provide a very strong signal to banks if they come from central banks and supervisors, or organically from banks themselves, and are expected to encourage banks to assess and manage credit risks which may transit from climate risks.

Some argue that green loans possess better credit quality than non-green loans, particularly in terms of a lower non-performing loan (NPL) ratio (Weber et al. 2010 , 2015 ; Cui et al. 2018 ). On the other hand, NGFS conducted a preliminary stock-taking of research on credit risk differentials in terms of default rates and NPL ratio between green and non-green assets and concluded that there were no potential risk differentials (NGFS 2019 ). Existing data gaps is one of the factors that make a conclusion difficult to be drawn. Simply put, there isn’t much data available in this field given this is still a very new area and it’s been only a few years since countries and banks have started analyzing the potential risk exposure. Consistent and reliable data covering the credit exposure to climate risks and risk-return profiles of green and non-green assets over a sufficient period of time is needed (NGFS 2019 ).

The role of central banks and financial regulators in responding to climate change challenges

Debates on the role of the central banks and financial regulators.

As the financial risks from climate change are becoming more apparent and relevant to the banking sector, a growing number of central banks and financial regulators are taking them more seriously (Monnin 2018 ). NGFS members also acknowledge that climate-related risks are becoming financial risks and therefore taking care of climate risks is within the mandates of central banks and supervisors (NGFS 2018 ). Prior to the launch of the NGFS, the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) and the G20 Sustainable Finance Study Group, which was formerly known as G20 Green Finance Study Group, were established to serve similar objectives. The TCFD was established by the Financial Stability Board, which is an international body that monitors and makes recommendations about the global financial system, with an aim to develop voluntary, consistent climate-related financial risk disclosures that would be helpful to investors, lenders, insurance companies and asset managers in identifying and managing financial risks (TCFD 2017 ). Similarly, the G20 Sustainable Finance Study Group was created to identify barriers to green finance and improve the financial system to mobilize private capital for green and sustainable investment (G20 Green Finance Study Group 2017 ). While these kinds of frameworks and industry-led initiatives are major drivers of innovation and risk management, the public sector, namely central banks and financial regulators, also must play a supporting role in mainstreaming green finance and making sure climate-related risks are properly measured, verified and reported. However, many central banks are still reluctant to ease capital requirements for green lending without clear evidence that green finance indeed carries lower risks. Many debates are now arising regarding the climate change and environmental mandate of central banks and financial regulators (Volz 2017 ).

According to the statutes of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), a central bank is defined as the bank that has been entrusted the duty of regulating the volume of currency and credit in the country. Central banks have historically had three main functional roles, which are to maintain price stability and financial stability, to support a country’s financing needs at times of crisis and to constrain misuse of its financial powers in normal times (Goodhart 2010 ). Additionally, central banks are often required to contribute to stabilizing exchange rate, creating jobs and fueling economic growth (Barkawi and Monnin 2015 ). Central banks often act as financial regulators that define the rules for banking and non-banking financial institutions such as the minimum capital requirement and specific restrictions on certain types of lending. However, there are other cases where an independent supervisory authority is established with the power of financial regulations and supervision while a central bank solely focuses on the monetary policy. The recent financial crisis between 2007 and 2008 indeed accelerated and expanded the role of central banks as the guardian of the financial system and as a lender of last resort. In this respect, the main job of a central bank is to control inflation and macroeconomic and financial stability. Thus, in a narrow sense evaluating climate-related risks and adjusting its monetary and macroprudential policies accordingly can be seen as overstepping its mandate. Volz ( 2017 ) also described potential conflicts with core objectives and mandates of central banks, overstretching their powers and resistance within the central banking community by incorporating the green objective in the mandate of central banks. Additionally, there is a question on the legal mandate of central banks. Some central banks in developing countries such as the Bangladesh Bank, the Banco Central do Brasil and the People’s Bank of China are active in pursuing green central banking policies and explicitly included sustainability in their mandate (Dikau and Ryan-Collins 2017 ). Also, the Financial Services Authority (OJK), the financial market regulator in Indonesia, has safeguarding financial system stability as a foundation of sustainable development in their corporate objectives and subsequently launched a roadmap for sustainable finance in 2014 and regulation on sustainable finance in 2017 (OJK 2014 ; OJK 2017 ). However, such an environmental sustainability mandate is relatively ambiguous for those in developed countries. For example, Article 127 (1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union defines price stability as the main objective of the European System of Central Banks (ESCB). Although some rely on Article 3 (3) of the Treaty on European Union, which states that the European Central Bank (ECB) shall support the general economic policies in the Union including a high level of protection and improvement of the quality of the environment, to argue that the ECB already integrated the environmental sustainability in its mandate; however, it is still considered as a secondary objective of the ECB and thus there is room for different interpretations. One study found that 54 out of 133 central banks have a mandate to spearhead sustainable economic growth or support sustainability goals set by the government but their mandates are not explicitly linked to climate change (Dikau and Volz 2019 ). To sum up, most central banks have focused on its interventionist role in the world’s economies since the financial crisis and they have not made significant adjustment of their policies to support a low-carbon transition (NEF 2017 ).

An increasing number of central banks and financial regulators, however, started analyzing the negative climate change effects on their banking and non-banking financial sector, and recent research supports the argument that climate change challenges can damage the financial stability (PRA 2015 ; Batten et al. 2016 ; Dietz et al. 2016 ; Volz 2017 ; Campiglio et al. 2018 ). The negative impact of climate change on the banking sector has already been analyzed from the transition, physical and liability perspectives. As shown in Fig. 2 , climate change challenges can pose potential threats to the stability of the financial markets, price and macroeconomics, all of which are within the key mandate of central banks and financial regulators. Moreover, fluctuations in energy prices while transitioning to a low-carbon economy can directly influence price stability and inflation and can hamper economic growth in all sectors, including the financial sector (DNB 2016 ). Stranded assets caused by transition risks can lead to a climate “Minsky” moment whereby a sudden, major collapse of asset values is expected to threaten the financial stability and trigger cascade effects throughout the interconnected financial system (Minsky 1982 ; Minsky 1992 ; Carney 2015 ; ESRB 2016b ; Battiston et al., 2017 ). The latest IPCC special report also mentioned that central banks or financial regulators could be a facilitator of last resort for climate financing instruments which can help lower the systemic risk of stranded assets (Safarzyńska and van den Bergh 2017 ). Other arguments supporting the expanded role of central banks and financial regulators include their responsibility for wider public goals such as the mitigation of market failure and their role in developing long-term national strategies (NEF 2017 ; Volz 2017 ). Given that climate change is becoming a major threat to the global economy, central banks and regulators are increasingly being asked to analyze climate change effects and intervene when necessary to exercise their duty as public institu7pt?>tions. Also, as putting specific restrictions on certain types of lending is one of their responsibilities, central banks and regulators should restrict financial flows and bank lending to carbon-intensive and environmentally-harmful borrowers to mitigate a credit market failure. Central banks and regulators are required to develop and implement a forward-looking monetary policy strategy (Montes 2010 ) because monetary policies usually affect the economy with a lag. The same principle should apply when dealing with climate change challenges. Central banks and regulators should develop a long-term climate change strategy and provide a long-term market signal to investors who need to deliver a vast amount of investment needed for a low-carbon transition. More central banks and regulators tend to accept their evolving roles. The NGFS declared that climate-related risks fell squarely within their mandate. A member of the Executive Board of the ECB also argued that the ECB can and should support the transition to a low-carbon economy acting within its mandate while acknowledging different views and opinions around this topic (Cœuré 2018 ).

Different approach in developing countries vs. developed countries

It is widely acknowledged that countries that established clear guidelines and mandatory regulations to direct public and private financing towards green products, offer an enabling environment for domestic finance institutions to scale up their green investments (GIZ 2019 ). However, approaches toward green banking policy interventions tend to be different between developing and developed countries, although actions taken by prudential authorities in developed countries vary. For example, rule-based authorities such as those within France tend to act more proactively and introduce policies that aim to measure climate risks, while principle-based authorities such as those within Switzerland and Japan tend to take more market-driven approaches (Spiegel et al. 2019 ). As summarized in Table 2 , many of the developing countries have introduced mandatory regulations which require their banks to formalize and implement an environmental and social safeguards policy and report relevant activities to central banks and regulators. In some cases, central banks in developing countries such as Bangladesh and India set specific lending quotas for climate-sensitive sectors. Many developing countries have received support from multilateral development agencies such as IFC in developing their green banking policy framework. According to IFC, developing countries are at different stages of sustainable finance development and Bangladesh, Brazil, China, Colombia, Indonesia, Mongolia, Nigeria and Vietnam are most advanced as they have started reporting on results of their implementation actions (IFC 2018a , 2018b ). On the other hand, most the developed countries have taken an industry-driven, voluntary approach, focusing mainly on the disclosure of climate-related financial risks as part of supporting the TCFD. As of 2018, governments in Belgium, France, Sweden, and the United Kingdom (U.K.) and financial regulators from Australia, Belgium, France, Japan, the Netherlands, Sweden and the U.K. have expressed support for the TCFD, which fully remains a voluntary initiative (TCFD 2018 ). Furthermore, France made the disclosure of climate-related financial information by listed firms, banks and credit providers as well as investors mandatory under its Energy Transition Law for Green Growth. Japan is another case of a developed country, as the Bank of Japan provides concessional loans to banks that lend to environment and energy businesses. However, even those mandatory schemes under implementation often lack details of the enforcement and thus create some ambiguity as to the extent to which authority within the government will take the responsibility of compliance-check and monitoring.

Green banking policy instruments

Green banking policy instruments can be grouped into four different policy areas which include macro-prudential policy, micro-prudential policy, market-making policy and credit allocation policy according to Dikau and Volz ( 2018 ), as summarized in Table 3 .

Green macro-prudential policy aims to define the rules for financial institutions and mitigate the systemic financial risks to the macro-economy caused by climate change. Green macro-prudential tools can include a climate stress-testing of the banking system, differentiated capital requirements depending on the proportion of green portfolio of the bank and restrictions on credit exposure and financial ratios. Such tools can help central banks and regulators influence the lending activity of banks by encouraging them to make more green investments. Arguably, the most powerful macro-prudential tool would be the Basel accord. The current capital and liquidity requirements under the Basel III accord do not necessarily require banks to evaluate the impacts of climate risks on their balance-sheet (BCBS 2016 ; ESRB 2016a ). Given that the Basel III standards have been adopted and are being implemented by all 27 Basel committee member jurisdictions (BCBS 2018 ), they are the most widely accepted standards in the banking industry across developing and developed countries. Therefore, consideration of climate and environmental risks by the Basel committee in assessing their impacts on the stability of the banking sector will give a very strong market signal and further encourage central banks and regulators to adopt robust environmental and social risk management frameworks.

Green micro-prudential policy seeks to encourage individual financial institutions to incorporate environmental and social safeguards into their policies and operations. Green micro-prudential instruments can include information disclosure of climate-related financial risks by banks, adoption and implementation of environmental and social risks management and differentiated reserve requirements. For example, Banque du Liban, the central bank of Lebanon, introduced a climate finance loan scheme whereby commercial banks are exempted from part of the required reserve when they lend to energy-related projects under the National Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Action (NEEREA) (CCCU 2014 ).

Central banks and regulators can play a market-making role to promote green investments and operations. For example, they can develop and provide sustainable finance guidelines for banks that can create an enabling environment in the banking sector. This is the core initiative of IFC’s Sustainable Banking Network. Another example is to develop green bond guidelines to encourage the issuance of green bonds by banks because proceeds of green bonds can be exclusively used to finance green projects. Most green bonds issued in the past followed standards set by the International Capital Market Association (ICMA) and Climate Bonds Initiative. However, some countries and regions such as China and ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) recently developed their own standards to propel their green bond market.

Finally, green credit allocation policy seeks to promote lending and investment toward climate-sensitive sectors such as agriculture, energy and water. Some central banks have been implementing such a policy by setting a minimum proportion of bank lending to climate and environment-related sectors, creating concessional green refinancing windows and extending concessional loans to banks that lend to climate-sensitive sectors.

Additionally, the NGFS made six recommendations that can help central banks, supervisors, policy makers and financial institutions manage climate risks and ultimately make the financial system green and climate-resilient (NGFS 2019 ). The six recommendations include integrating climate risks into financial stability monitoring and prudential supervision, incorporating environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors into portfolio management, sharing and disclosing climate risk data, capacity building and awareness raising, supporting the work of the TCFD and development of a green and climate taxonomy. Developing a robust green and climate taxonomy can be a key instrument to mitigate the possibility of a green bubble and green washing.

Measuring the effectiveness of green banking policies

Measuring the effectiveness of green banking-related policies at both a sectoral and institutional level can be premature mainly due to the current lack of data and measurement methodologies, let alone comparing the performance and effectiveness between developing and developed countries and among different instruments. Many scholars have been very active in their endeavors to analyze the performance of China’s Green Credit Policy; however, their findings showed mixed results on whether implementing the policy has been effective in serving its goals (Scholtens et al. 2008 ; Aizawa and Yang 2010 ; Zhang. et al., 2011 ; Jin and Mengqi 2011 ; Stephens and Skinner 2013 ; Gong and Gao 2015 ; Lian 2015 ; Liu et al. 2015 ; Ge et al. 2016 ; Yu and Ren 2016 ). Another study analyzed the relationship between corporate environmental information disclosure, as required under the Green Credit Policy in China, and corporate green financing. It concluded that the environmental information disclosure requirement did not become a risk management tool for banks to make their financing decisions (Wang et al. 2019 ).

Also, China has officially started measuring and reporting the effectiveness of its Green Credit Policy based on the NPL ratio. The China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC, formerly the China Banking Regulatory Commission) reported that the NPL ratio of green loans provided by the 21 domestic major banks was 0.41%, which is 1.35% lower than the NPL ratio of all loans, in September 2016. In June 2017, CBIRC subsequently released the same data showing that the NPL ratio of green loans decreased to 0.37%, which is 1.32% lower than the that of all loans (Cui et al. 2018 ; NGFS 2019 ).

Despite early attempts, mostly led by China, to measure the effectiveness of green banking policies and green loans, there is still a significant lack of data availability and inconsistency to draw a clear conclusion.

The role of banks in responding to climate change challenges

Financial institutions, especially banks, have a unique market position as they have deep market knowledge and experience across all economic sectors. They arguably have one of the widest networks, outreaches and client bases and can shift consumer behavior by scaling up and redirecting financing flow towards low-carbon and climate-resilient investments.

Many international and local banks have undertaken various green banking initiatives to seize business opportunities, manage risks, comply with national and regional regulations and guidelines, enable countries to deliver their climate ambitions and encourage corporate social responsibility (CSR). According to IFC, there is USD 23 trillion worth of climate-smart investment opportunities in developing countries between 2016 and 2030 (IFC 2018a , 2018b ). Such investment opportunities will be more enormous if those in developed countries are added. Therefore, it is a natural move by commercial banks to enter into a lucrative market. According to a survey of 90% of the UK banking sector, 70% of banks in the country view climate change as a threat to the financial system, although the same survey found that only 10% are building a strategy on climate-related financial risk management (PRA 2018 ). As the banking sector is a heavily regulated market, eventually all the green banking policy efforts by central banks and regulators will seek to change the behavior of commercial banks and lead them to gradually shift their focus toward more climate- and environment-friendly ways of doing business which can help themselves manage their risk exposure and also countries meet their climate goals. Finally, some banks view green banking as a CSR-related activity as they see growing demands for banks to be greener and more sustainable by their clients and foresee potential reputational risks. CSR as a governance tool can be useful for monitoring the behavior of management in financial institutions, especially for those identified as “too big to fail” because they are critical to the economy (Barclift 2011 ). In this section, actions being taken by commercial banks, both collectively and individually, and their performance will be presented and analyzed, and gaps and areas for improvement will be identified and suggested.

Collective actions and their performance

A growing number of financial institutions around the world have voluntarily either created their own networks or initiatives or joined platforms established by international development agencies such as IFC and United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Some of the well-known ones are outlined in Table 4 . The common objectives of these frameworks and initiatives include development and adoption of standards, principles and risk management frameworks and sharing knowledge and best practices such as the Equator Principles. The Sustainable Banking Network (SBN), established by IFC, is a network of central banks, regulators and banking associations in developing countries that facilitates the collective learning of members and supports them in policy development (IFC 2016a ). Several developing countries such as Mongolia have received support from IFC SBN when they developed and launched their sustainable finance principles. The Banking Programme, established by the UNEP-Finance Initiative (FI), aims to help banks understand environmental, social and governance challenges for their operations and is probably the largest green banking initiative with over 130 member banks across the world. The UNEP FI also supported some of their members to create the Principles for Responsible Banking which aimed to define the banking industry’s role and responsibilities in shaping a sustainable future and align banks’ business with the objectives of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Paris Climate Agreement (UNEP FI 2018 ).

Performance of some green banking frameworks and initiatives has been analyzed by researchers and the result so far is mixed. For example, Weber and Acheta ( 2016 ) analyzed reports issued by Equator Principles signatories and concluded that the Equator Principles did not make significant contributions to both sustainability of projects and the financial system because they were primarily adopted as a means to enhance reputation and risk management of the signatories. Earlier research also stated that adoption of the Equator Principles was mainly used to signal responsible conduct and did not find significantly improved aspect of financial performance between adopters and non-adopters apart from the size factor (Scholtens and Dam 2007 ). On the contrary, a research by the GABV compared the financial performance of their member banks and that of the global systemically important banks (GSIB), namely the largest banks in the world, and found that their member banks achieved higher return-on-assets and return-on-equity than GSIBs with lower volatility between 2007 and 2016 (GABV 2018 ). Moreover, some studies have found that green tagging, which refers to identifying green attributes of a bank’s loan and asset portfolio, may lead to lower probability of default of borrowers (Principal 2017 ; Sahadi et al. 2013 ). According to a survey conducted by IFC, 62% of a sample of 42 banks from developing countries responded that the non-performing loan ratio of their green portfolios is lower compared to that of other non-green portfolios (IFC 2018a , 2018b ).

Individual actions and instruments

A bank is a complex institution with financial products and numerous services that they offer to their clients. As more green- and climate-related themes have increasingly become mainstreamed in the banking sector and demands by their clients grow, banks started launching dedicated green financial products and services, mostly using and customizing their existing offerings. Table 5 is not an exhaustive list of those products and services but presents the most-widely used instruments by banks. Arguably, the main function of a bank is to lend money. There are different types of borrowers, but the majority of a bank’s lending goes to companies, individuals and projects. As there have been emerging green investment opportunities and ways to lower the costs by reducing energy bills for example, more borrowers rely on bank lending to develop renewable energy projects,climate-resilient infrastructure projects and install more energy-efficient and climate-smart equipment, appliances, houses and vehicles. Small-holder farmers also borrow from a bank or a micro-finance institution to purchase climate-resilient seeds and climate-smart agriculture equipment. Some banks offer an insurance product, often by using their insurance subsidiary. A green auto insurance product can be offered to financially incentivize users by lowering insurance premium when they use electric or hybrid vehicles which emit less greenhouse gases and other pollutants. Banks can also help finance green projects and refinance existing green assets through securitization using bond issuance and warehousing. Securitization can also help free up capital by selling securities to third-party investors to support further lending to low-carbon and climate-resilient assets. Some banks perform principal investing, using their own balance-sheet, to hold a direct equity stake on start-ups and venture firms that develop green and climate-smart technologies. An alternative way is to invest in a private equity fund as an intermediary who will invest into green projects on behalf of its investors. Many banks offer brokerage and market-making services for trading of green bonds and carbon credits to help facilitate green investments. Finally, some banks provide advisory services to their clients usually for financial structuring of a project. Quite a few borrowers consider a green project complicated in terms of structuring the transaction from a financial point of view and a bank can help them using their expertise and experience. A few banks sometimes try to stimulate demands by offering capacity building support to their borrowers or project developers. For example, a bank can help a borrower perform an energy audit of its firm, factory or house by dispatching the bank’s own resources.

According to IFC (IFC 2018a , 2018b ), the proportion of banks from developing countries that provide climate lending increased from 61% in 2016 to 72% in 2017 among 135 sample banks and they have been most active in the renewable energy and energy efficiency sector. Additionally, 49% of the banks offered dedicated green financial products. Green credit was the most widely used financial product, followed by green insurance and advisory services and green investment funds. Finally, although 55% of the banks currently do not provide green financial products, 88% of them expressed their interest in offering such instruments in the future if additional support is provided. A good example for green financial products can be an auto-loan that can be used to purchase electric or hybrid vehicles which emit zero or significantly less greenhouse gases compared to vehicles with a combustion engine. Some countries provide a subsidy to promote the purchase of electric or hybrid vehicles because they usually cost more. However, not many countries can afford it due to budget constraints. Banks can bridge the gap if they can launch affordable eco-car loans which provide financial incentives to their clients to switch their choice of vehicles in addition to fuel cost savings they can benefit from.

Theory of change in green banking

Application of theory of change

The theory of change framework is generally regarded as an assessment of inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes and impacts, articulating how certain types of interventions are expected to lead to changes and achievements (Rauscher et al. 2012 ; Stein and Valters 2012 ). The theory of change framework provides the logical underpinning of changes and goals and highlights the relation between activities and expected outputs, outcomes and impacts from the carrying out of the activities. According to Stein and Valters ( 2012 ), the theory of change framework serves to map the change process and its expected results and facilitates implementation of projects (strategic planning); to articulate anticipated processes and results that can be monitored and evaluated (monitoring and evaluation); to communicate change processes to internal and external stakeholders (description); and to help organizations clarify and improve the theory behind them or their programmes (learning).

The theory of change can be a useful strategic framework and tool to assess status of green banking, conduct a gap analysis, identify activities needed to be performed to mitigate gaps and barriers and describe expected results and impacts that can be created. Given that there is a lack of data availability in this field of research, a theory of change can also be helpful for identifying the data that should be collected and how they can be analyzed in the future (Rogers 2014 ). In linking the theory of change model to green banking, barriers and gaps will be used instead of inputs as a means to identify and narrow the gap between change objectives and actual potential in green banking. Additionally, outputs and outcomes will be merged into results. The data on barriers and activities were collected and developed based on literature review and market observations. Results and impacts are desired outcomes of green banking activities which aim to contribute to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and enhancing climate-resilient sustainable development.

Three types of theory of change framework – sectoral, institutional and integrated - will be presented as different interventions are required to transform an institution versus the whole banking sector. An integrated theory of change framework aims to capture both aspects.

Theory of change at the sectoral level

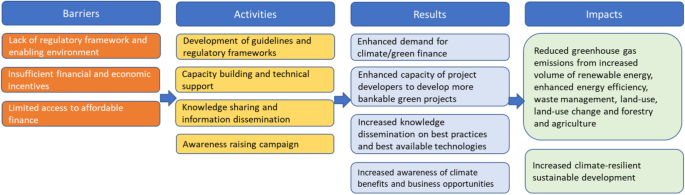

The theory of change in green banking at the sectoral level is related to making systemic changes and transformation within the entire banking sector which can drive both supply and demand for green banking products and services. Therefore, it is more inclusive than the theory of change at the institutional level as engaging with other stakeholders such as project developers, beneficiaries and government agencies is critical.

There are sectoral barriers that can influence activities of individual banks and can create institutional barriers as shown in Fig. 3 . Lack of regulatory framework and enabling environment often leads to disincentivizing banks to undertake green banking activities as the banking sector is highly regulated. For example, the banking sector can set criteria for the businesses they finance, especially carbon-intensive industries, thereby mitigating the risks related to an energy transition and ultimately making the economy more sustainable (DNB 2016 ). Other sectoral barriers include insufficient financial incentives for both banks and project developers and limited access to affordable finance.

Theory of change in green banking at sectoral level

While some countries may prefer market-led approaches compared to regulations or rules to encourage green banking activities, development and implementation of green banking policy guidelines or regulatory frameworks is expected to accelerate necessary actions by financial institutions. Such policy-level interventions should also include supports for capacity building, knowledge sharing and awareness raising to maximize their impact and to reach desired results and outputs.

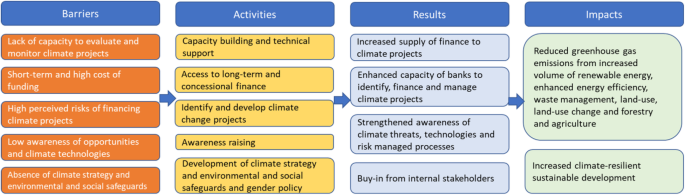

Theory of change at the institutional level

The theory of change in green banking at the institutional level, as shown in Fig. 4 , assumes that most financial institutions are not active in terms of providing green banking products and services because they often do not recognize the climate and green sector as commercially viable. This is mainly due to the perception of risks associated with climate change projects and their existing capacity or willingness to develop and grow financial supply in the sector is insufficient. Most financial institutions from developing countries have short-term and high cost funding which prevent them from providing more affordable financing to their borrowers which is critical to stimulate market demands for climate projects. Additionally, other types of barriers include low awareness of business opportunities and best-available climate technologies and absence of overall climate change strategies and environment and social safeguards that are needed to properly finance climate change projects. Establishing green financial products and services is often constrained by such barriers as knowledge gaps to design and operationalize the products and services and high upfront costs necessary to assess and verify technology performance.

Theory of change in green banking at institutional level

To mitigate those barriers, activities such as capacity building and access to long-term and concessional financing are needed. Additionally, financial institutions need to put more efforts into identifying and developing climate change projects and raising internal awareness. All of these activities will lead to an increased supply of financing to climate change projects. Also, developing a climate strategy and environmental and social safeguards including gender policy will help in obtaining buy-in from internal stakeholders and properly managing the projects.

Integrated theory of change framework

Mainstreaming green banking into the core banking policies and practices remains a challenge at both institutional and sectoral level because there are still many barriers and gaps to overcome and activities to be undertaken to achieve desired results and impacts.

As shown in Fig. 5 , barriers or gaps refer to impediments to promotion of green banking and they exist at both the institutional and sectoral level and are often intertwined with each other. For example, the sectoral barriers are likely to naturally become institutional barriers unless financial institutions either individually or collectively take their own action on a voluntary basis. The costs of the transition to green banking by reducing the barriers and undertaking desired activities can be evenly shared among the public sector, private sector and financial institutions, although the financial institutions are expected to be more responsible to cover many of their own activities. The public sector can be divided into domestic and international, depending on the source of financing. The domestic public sector can support the transition through various policy measures such as policy lending, subsidies and tax benefits. On the other hand, the international public sector, such as climate funds and multilateral development banks, can provide grants for technical assistance and capacity building and long-term concessional loans. The private sector can contribute by developing bankable climate projects and technologies. Expected results are also likely to happen at both the sectoral and institutional level.

The application of the theory of change indicates that if the establishment of a green financing programme with more affordable terms for climate purposes is achieved and the capacity of banks is built up, then demand for such a lending product is expected to be stimulated within the country, driving the spread of green banking activities. It is expected that expanding lending for the purpose of investing in greenhouse gas mitigation and climate resilience projects is likely to lead to the achievement of climate change mitigation and resilience impacts throughout the economies of the countries where such green banking activities are being established.

Conclusions and implications for further studies, policy makers and practitioners

The concept of green banking still has a long way to go until it gets fully mainstreamed in the banking sector. However, simultaneous activation of both top-down and bottom-up engagement in raising the awareness of green banking has taken off. Policy makers and regulators have been increasingly realizing the importance of adopting green banking policy interventions as a means to transform the financial sector which can immensely contribute towards helping countries meet their climate targets and goals. Especially, the role of central banks and financial regulators is key as they have the power to change and control dynamics and landscape of the financial sector. Considering that most developed countries rely on a voluntary code of conduct by their banks and focus on the information disclosure while developing countries tend to use more regulatory approaches to promote green banking activities, future research could examine the performance and effectiveness of each green banking policy instrument and identify which approach is proven to be more effective or has the better prospect. However, it is expected to take considerable time before any researcher can undertake such analysis because of a lack of data availability as this is very new research area. It would be equally challenging to design and develop the criteria against which performance and effectiveness of the policy instrument will be measured.

Simultaneously, more banks are willing to become greener either individually or collectively and started launching green financial products, mainly in order to increase their economic value, but also to be good corporate citizens. Green financial products serve banks to fulfill several important objectives: banks can comply with government’s regulations or guidance, enhance firm reputation, and seize emerging business opportunities. The size of the green market has been steadily growing and expected to grow further. Banks that can establish themselves as early-movers and market leaders are more likely to enhance their reputation which can in turn help attract new clients. Further, from strategic perspective, change of consumer buying behavior by encouraging them to maximize the use of green financial products is most desirable. Thus, banks will have to develop and implement robust environmental and social safeguard standards to be able to manage their green financial products and comply with the regulations or guidelines.

While there is a limited number of studies that found a positive relationship between green and social banking activities and financial and operational performance of banks, it is too early to draw such a conclusion. To do so, more data are needed and various studies should be conducted both theoretically and empirically. For example, a formal survey targeting financial institutions on current barriers and desired activities can be a useful tool for collecting the data and making the theory of change more robust. With such data in place, a structure for a more systematic and empirical analysis of root causes of market barriers and activities to address them can be developed. Also, it could be interesting future research to identify if reputation plays a mediating role between green banking activity and financial as well as operational performance of banks. Other future research topics in this area can include investigating whether green banks outperform non-green banks in terms of climate as well as operational and financial performance, and comparing the effectiveness of green banking policy measures. However, parameters and standards need to be developed to measure the green and climate performance of banks and such a task is expected to be a major challenge.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Association of Southeast Asian Nations

Bank for International Settlements

Corporate Social Responsibility

European Central Bank

European System of Central Banks

Environmental, Social and Governance

Global Alliance for Banking on Value

Gross Domestic Product

International Capital Market Association

International Finance Corporation

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

National Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Action

Network for Greening the Financial System

Non-Performing Loans

Financial Services Authority

Sustainable Banking Network

Sustainable Development Goal

Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures

United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

Aizawa M, Yang C (2010) Green credit, Green stimulus, Green revolution? China’s Mobilization of Banks for Environmental Cleanup. J Environ Dev 2010(19):119–144

Article Google Scholar

Alexander K (2016) Greening banking policy. In: Support of the G20 Green Finance Study Group

Google Scholar

Arezki R, Bolton P, Peters S, Samama F, Stiglitz J (2016) From global savings glut to financing infrastructure: the advent of investment platforms. In: IMF working paper WP/16/18. International Monetary Fund (IMF), Washington DC, 46

Bank of Japan (2010). Principal terms and conditions for the fund-provisioning measure to support strengthening the foundation for economic growth conducted through the loan support program.

Barclift Z (2011) Too Big to Fail, Too Big Not to Know: Financial Firms and Corporate Social Responsibility. J Civil Rights Econ Dev 25(3):2

Barkawi, A and Monnin, P (2015). Greening China’s Financial System. International Institute for Sustainable Development, Ch. 7, Winnipeg

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) (2016) Guidance on the application of the core principles for effective banking supervision to the regulation and supervision of institutions relevant to financial inclusion. Bank of International Settlements

Batten S, Sowerbutts R, Tanaka M (2016) Let’s talk about the weather: the impact of climate change on central banks. Technical report, Bank of England

Battiston S, Mandel A, Monasterolo I, Schütze F and Visentin G (2017) A climate stress-test of the financial system. Nat Clim Chang 7(4):283–288

BCBS (2018) Fifteenth progress report on adoption of the Basel regulatory framework. Bank of International Settlements

Beck T, Demirguc-Kunt A (2006) Small and medium-sized enterprises: access to finance as a growth constraint. J Bankng Finance 30(11):2931–2943

Bihari S (2011) Green banking-towards socially responsible banking in India. Int J Bus Insights Transform 4(1) October 2010 – March 2011

Campiglio E et al (2018) Climate change challenges for central banks and financial regulators. Nat Climate Change

Carney M (2015) Breaking the tragedy of the horizon - climate change and financial stability (speech). Bank of England, Speech

Christophers B (2017) Climate change and financial instability: risk disclosure and the Problematics of neoliberal governance. Ann Am Assoc Geographers 107(5):1108–1127. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2017.1293502

Climate Change Coordination Unit (CCCU) (2014). Climate finance loan schemes: Existing and planned loan schemes in Lebanon

Cœuré B (2018) Monetary policy and climate change (speech). the Executive Board of the ECB, Speech at at a conference on “Scaling up Green Finance: The Role of Central Banks”, organised by the Network for Greening the Financial System. the Deutsche Bundesbank and the Council on Economic Policies, Berlin

Cook J, Nuccitelli D, Green S, Richardson M, Winkler B, Painting R, Way R, Jacobs P, Skuce A (2013) Quantifying the consensus on anthropogenic global warming in the scientic literature. Environ Res Lett 8(2):024024

Cui, Y., Geobey, S., Weber, O. And Lin, H (2018). The impact of Green lending on credit risk in China. Sustainability

Book Google Scholar

Dietz S, Bowen A, Dixon C, Gradwell P (2016) “climate value at risk” of global financial assets. Nat Climate Change 6(7):676

Dikau S, Ryan-Collins J (2017) Green central banking in emerging market and developing country economies. New Economics Foundation, London

Dikau S, Volz U (2018) Central banking, climate change and green finance. In: ADBI working paper series 867. Asian Development Bank Institute, Tokyo

Dikau, S. and U. Volz (2019). Central Bank mandates, Sustainability Objectives and the Promotion of Green Finance

DNB (2016). Time for transition: an exploratory study of the transition to a carbon-neutral economy

Doran PT, Zimmerman MK (2009) Examining the scientic consensus on climate change. Eos Transac Am Geophys Union 90(3):22–23

Dufays L (2012) Responsible banking, the 10 principles. IEB Int J Finance 2012(5):238–269

EBF (2017). Towards a green finance framework

EBF (2018). Towards a green finance framework. European Banking Federation report

ESRB (2016a). Too late, too sudden: transition to a low-carbon economy and systemic risk. Reports of the Advisory Scientific Committee No 6

ESRB (2016b). Macroprudential policy beyond banking: an esrb strategy paper. Technical report, Advisory Scientific Committee of the European Systemic Risk Board

G20 Green Finance Study Group (2017). G20 Green Finance Synthesis Report 2017

GABV (2012). Strong, straightforward and sustainable banking

GABV (2018). Real economy – real returns: the business case for values-based banking

Ge L, Huang HF, Wang MC (2016) Research on the credit risk of the green credit for new energy and high pollution industry—based on empirical data test of KMV model. J Math Prac Theory 2016(46):18–26

GIZ (2019). The Role of National Financial Institutions in the Implementation of NDCs

Gong J, Gao WD (2015) Analysis on the influencing factors of developing green credit to the competitiveness of banks—a case study of industrial Bank Co. Ltd. J Chang Financ Coll 2015(2):12–17

Goodhart CAE (2010) The changing role of central banks, BIS working papers no 326. Bank for International Settlements, Basel

Heede R (2014) Tracing anthropogenic carbon dioxide and methane emissions to fossil fuel and cement producers, 1854–2010. Clim Chang 122(1):229–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-013-0986-y

Heinen A, Khadan J, Strobl E (2016) “The inflationary costs of extreme weather in developing countries”, mimeo, paper presented at the Bank of England conference on ‘central banking, climate change and environmental sustainability’, 14 November

IDRBT (2013). Greening banking for Indian banking sector

IFC (2013) Mobilizing public and private funds for inclusive Green growth Investment in Developing Countries, An expanded stocktaking report prepared for the G20 development working group. IFC Climate Business Department

IFC (2016a). Greening the banking system – experiences from the Sustainable Banking Network (SBN). https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/712ae885-5985-4fa4-9c27-a089f84f4ab7/SBN_PAPER_G20_3rd+draft_updated.pdf?MOD=AJPERES

IFC (2016b) Green finance: a bottom-up approach to track existing flows. Climate Business Department

IFC (2018a). Raising US$ 23 trillion: Greening banks and capital markets for growth. G20 input paper on emerging markets

IFC (2018b). Sustainable Banking Network (SBN) Global Progress Report

IPCC (2001). Climate change 2001: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

IPCC (2018). Global warming of 1.5°C

Jin D, Mengqi N (2011) The paradox of green credit in China. Energy Procedia 2011(5):1979–1986

Kaeufer K (2010) Banking as a vehicle for socio-economic development and change: case studies of socially responsible and Green banks. Presencing Institute, Cambridge, p 6

Kim Y, An H, Kim J (2015) The effect of carbon risk on the cost of equity capital. J Clean Prod 93:279–287

Lian LL (2015) Does green credit influence debt financing cost of business?—a comparative study of green businesses and “two high” businesses. J Guangdong Univ Financ 2015(30):83–93

Liu JY, Xia Y, Lin SM, Wu J, Fan Y (2015) The short, medium and long term effects of green credit policy in China based on a financial CGE model. Chin J Manag Sci 2015(23):46–52

Mazzucato M, Semieniuk G (2018) Financing renewable energy: who is financing what and why it matters. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 127:8–22

Minsky HP (1982) Can ‘It’ happen again? Essays on instability and finance. M.E. Sharpe, New York

Minsky, H. P. (1992). The financial instability hypothesis. Working paper 74, The Jerome Levy Economics Institute of Bard College

Monnin P (2018) Central banks and the transition to a low-carbon economy. Technical report, discussion note 2018/1. Council on Economic Policies, Zurich

Montes G (2010) Uncertainties, monetary policy and financial stability: challenges on inflation targeting. Braz J Pol Econ 30(n° 1 (117)):89–111

New Economics Foundation (NEF) (2017). Central banks, climate change and the transition to a low-carbon economy: a policy briefing

NGFS (2018). First Progress report

NGFS (2019). First comprehensive report

OECD (2017) OECD economic surveys: Luxembourg 2017. OECD Publishing, Paris https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-lux-2017-en

OJK (2014). Roadmap for sustainable finance in Indonesia 2015–2019

OJK (2017). Regulation of financial services authority (NO. 51/POJK.03/2017) on application of sustainable finance to financial services institution, issuer and publicized listed companies

Platinga A, Scholtens B (2016) The Financial Impact of Divestment from Fossil Fuels. SOM Research Reports; no. 16005-EEF. SOM research school, University of Groningen, Groningen, p 47

PRA (2018), Transition in thinking: the impact of climate change on the UK banking sector

Principal (2017) Pillars of responsible property investing – connecting the dots to financial performance. Principal financial group research note. Principal Financial Services, Inc

Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) (2015), The impact of climate change on the UK insurance sector, A Climate Change Adaptation Report by the Prudential Regulation Authority

Rauscher O, Schober C, Millner R (2012) Social impact measurement und social return on investment (SROI)-analysis

Reserve Bank of India (2015). Priority sector lending – targets and classification

Rogers P (2014) Theory of change, methodological briefs: impact evaluation 2. UNICEF Office of Research, Florence

Safarzyńska K, van den Bergh J (2017) Financial stability at risk due to investing rapidly in renewable energy. Energy Policy 108(2017):12–20

Sahadi R, Stellberg S, Quercia R (2013) Home energy efficiency and mortgage risks. Institute for Market Transformation, Washington, DC

SBP (2015). Concept paper on green banking

Schoenmaker D, Van Tilburg R (2016) What role for financial supervisors in addressing environmental risks? Comp Econ Stud 58(3):317–334

Scholtens B, Cerin P, Hassel L (2008) Sustainable development and socially responsible finance and investing. Sustain Dev 2008(16):137–140

Scholtens B, Dam L (2007) Banking on the equator. Are banks that adopted the equator principles different from non-adopters? World Dev 35(8):1307–1328

Spiegel, A., Wiener, D., Schneider-Roos, K. and Diamant, N. (2019). “The missing link: linking financial stability with environmental stability”, published by ecos

Stein, D. and Valters, C. (2012). Understanding theory of change in international development. The Justice and Security Research Programme. The Asia Foundation

Stephens, C. and Skinner, C (2013). Banks for a better planet? The challenge of sustainable social and environmental development and the emerging response of the banking sector Environ Dev 2013, 5, 175–179

TCFD (2017). Final report: recommendations of the task force on climate-related financial disclosures

TCFD (2018). 2018 status report. September 2018

UNEP (2016). Definitions and concepts: Background note.

UNEP FI (2018). Principles for responsible banking. Consultation version

USGCRP (2018). Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: fourth National Climate Assessment, volume II [Reidmiller, D.R., C.W. Avery, D.R. Easterling, K.E. Kunkel, K.L.M. Lewis, T.K. Maycock, and B.C. Stewart (eds.)]. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, 1515 pp. doi: https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA4.2018

Volz, U. (2017). On the role of central banks in enhancing green finance. UN environment inquiry working paper 17/01

Wang, F.; Yang, S,; Reisner, A; Liu, N (2019). Does Greem credit policy work in China? The correlation between Green credit and corporate environmental information disclosure Quality. Sustainability

Wang Y (2016) What are the biggest obstacles to growth of SMEs in developing countries? – An empirical evidence from an enterprise survey. Borsa Instanbul Rev 16(3):167–176

Weber, O and Acheta, E (2016). The Equator Principles – Do they make banks more sustainable?. UN Environment Inquiry Working Paper 16/05

Weber O, Hoque A, Islam AM (2015) Incorporating environmental criteria into credit risk management in Bangladeshi banks. J Sustain Financ Investig 2015(5):1–15

Weber O, Remer S (2011) Social banking – introduction. In: Weber O, Remer S (eds) Social banks and the future of sustainable finance. Routledge, London, pp 1–14

Chapter Google Scholar

Weber O, Scholz RW, Michalik G (2010) Incorporating sustainability criteria into credit risk management. Bus Strateg Environ 2010(19):39–50

Wörsdörfer M (2016) 10 years equator principles: a critical appraisal. In: Wendt K (ed) Responsible investment banking. Springer, Cham, pp 473–501

Yu WQ, Ren SY (2016) Empirical study on green credit and financial performance of commercial banks. Financ Rev 2016:33

Zhang B, Yang Y, Bi J (2011) Tracking the implementation of green credit policy in China: top-down perspective and bottom-up reform. J Environ Manag 2011(92):1321–1327

Download references

Acknowledgements

Author information, authors and affiliations.

Sustainability Management Department, Inha University, 100 Inha-ro, Michuhol-gu, Incheon, 22212, Republic of Korea

Hyoungkun Park

Green Climate Fund, 175 Art center-daero, Yeonsu-gu, Incheon, 22004, Republic of Korea

College of Business Administration, Inha University, 100 Inha-ro, Michuhol-gu, Incheon, 22212, Republic of Korea

Jong Dae Kim

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

HP carried out the research design and the literature review, performed the analysis and drafted the manuscript. JDK conceived the study and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jong Dae Kim .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Park, H., Kim, J.D. Transition towards green banking: role of financial regulators and financial institutions. AJSSR 5 , 5 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41180-020-00034-3

Download citation

Received : 19 October 2019

Accepted : 06 February 2020

Published : 06 March 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s41180-020-00034-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Green banking

- Sustainable banking

- Climate change

- Financial institutions

- Central bank

- Financial sector

- Theory of change

- Climate risk

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, green banking: a road map for adoption.

International Journal of Ethics and Systems

ISSN : 2514-9369

Article publication date: 30 June 2020

Issue publication date: 14 August 2020

The purpose of this study is to propose Green Banking best practices for the adoption of this business construct based on the dimensions of environment, social and governance (ESG). This paper proposes a number of green practices under the ESG dimensions that can be adopted by individual banks at any stage of Green Banking adoption. It provides tactics for implementing this business construct that can serve as a tool for regulatory authorities forming Green Banking guidelines or policies for adoption. Such research has not been undertaken up until now.

Design/methodology/approach

The Green Banking adoption model is based on the concept of human ecology in which the inter-dependency and inter-connectivity of the variables impacting the phenomenon of environmental sustainability. These influencing variables are, in turn, connected with the natural environment. In the proposed model, the variables of ESG are inter-connected and impacting the natural environment as well. The proposed best practices have been derived from the Green Banking practices of the global industry leaders and Green Banking regulations of developed and developing countries. It can be beneficial to the stakeholders, as it proposes a step-by-step guide to Green Banking adoption that can be followed either sequentially or in parallel by the banks.

Green Banking adoption can be achieved by banks through implementing certain practices in either sequential or parallel manner. The adoption process depends on the various external and internal environmental dependencies. The Green Banking adoption practices can be broken down in three areas, i.e. ESG, allowing the construct optimal depth of coverage and complexity.

Originality/value