Transforming education systems: Why, what, and how

- Download the full policy brief

- Download the executive summary

- Baixe o resumo executivo

- Baixar o resumo da política

تنزيل موجز السياسة

تنزيل الملخص التنفيذي

- Descargar el PDF en Español

- Descargar el resumen de políticas

Subscribe to the Center for Universal Education Bulletin

Rebecca winthrop and rebecca winthrop director - center for universal education , senior fellow - global economy and development the hon. minister david sengeh the hon. minister david sengeh minister of education and chief innovation officer - government of sierra leone, chief innovation officer - directorate of science, technology and innovation in sierra leone.

June 23, 2022

Today, the topic of education system transformation is front of mind for many leaders. Ministers of education around the world are seeking to build back better as they emerge from COVID-19-school closures to a new normal of living with a pandemic. The U.N. secretary general is convening the Transforming Education Summit (TES) at this year’s general assembly meeting (United Nations, n.d.). Students around the world continue to demand transformation on climate and not finding voice to do this through their schools are regularly leaving class to test out their civic action skills.

It is with this moment in mind that we have developed this shared vision of education system transformation. Collectively we offer insights on transformation from the perspective of a global think tank and a national government: the Center for Universal Education (CUE) at Brookings brings years of global research on education change and transformation, and the Ministry of Education of Sierra Leone brings on-the-ground lessons from designing and implementing system-wide educational rebuilding.

This brief is for any education leader or stakeholder who is interested in charting a transformation journey in their country or education jurisdiction such as a state or district. It is also for civil society organizations, funders, researchers, and anyone interested in the topic of national development through education. In it, we answer the following three questions and argue for a participatory approach to transformation:

- Why is education system transformation urgent now? We argue that the world is at an inflection point. Climate change, the changing nature of work, increasing conflict and authoritarianism together with the urgency of COVID recovery has made the transformation agenda more critical than ever.

- What is education system transformation? We argue that education system transformation must entail a fresh review of the goals of your system – are they meeting the moment that we are in, are they tackling inequality and building resilience for a changing world, are they fully context aware, are they owned broadly across society – and then fundamentally positioning all components of your education system to coherently contribute to this shared purpose.

- How can education system transformation advance in your country or jurisdiction? We argue that three steps are crucial: Purpose (developing a broadly shared vision and purpose), Pedagogy (redesigning the pedagogical core), and Position (positioning and aligning all components of the system to support the pedagogical core and purpose). Deep engagement of educators, families, communities, students, ministry staff, and partners is essential across each of these “3 P” steps.

Related Content

Rebecca Winthrop, Adam Barton, Mahsa Ershadi, Lauren Ziegler

September 30, 2021

Jenny Perlman Robinson, Molly Curtiss Wyss, Patrick Hannahan

July 7, 2021

Emiliana Vegas, Rebecca Winthrop

September 8, 2020

Our aim is not to provide “the answer” — we are also on a journey and continually learning about what it takes to transform systems — but to help others interested in pursuing system transformation benefit from our collective reflections to date. The goal is to complement and put in perspective — not replace — detailed guidance from other actors on education sector on system strengthening, reform, and redesign. In essence, we want to broaden the conversation and debate.

Download the full policy brief»

Download the executive summary»

Baixe o resumo executivo»

Baixar o resumo da política»

Descargar el PDF en Español»

Descargar el resumen de políticas»

Global Education

Global Economy and Development

Center for Universal Education

Kelsey Rappe, Grace Cannon, Modupe (Mo) Olateju

October 31, 2024

Online only

Wednesday, 9:00 am - 10:00 am EST

October 30, 2024

Our education system is losing relevance. Here's how to unleash its potential

Our education system was founded to supply workers with a relatively fixed set of skills and knowledge

.chakra .wef-spn4bz{transition-property:var(--chakra-transition-property-common);transition-duration:var(--chakra-transition-duration-fast);transition-timing-function:var(--chakra-transition-easing-ease-out);cursor:pointer;text-decoration:none;outline:2px solid transparent;outline-offset:2px;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-spn4bz:hover,.chakra .wef-spn4bz[data-hover]{text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-spn4bz:focus-visible,.chakra .wef-spn4bz[data-focus-visible]{box-shadow:var(--chakra-shadows-outline);} Karthik Krishnan

- Our current education system is built on the Industrial Revolution model and focuses on IQ, in particular memorization and standardization;

- We must update education with job readiness, the ability to compete against smart machines and the creation of long-term economic value in mind;

- Education access, equity and quality must be improved to solve the global education crisis – 72 million children of primary education age are not in school.

Education today is in crisis. Even before the coronavirus pandemic struck, in many parts of the world, children who should be in school aren’t; for those who are, their schools often lack the resources to provide adequate instruction. At a time when quality education is arguably more vital to one’s life chances than ever before, these children are missing out on the education needed to live fulfilling lives as adults and to participate in and contribute to the world economy.

Historically, education has been the shortest bridge between the haves and the have-nots, bringing progress and prosperity for both individuals and countries, but the current education system is showing its age. Founded at a time when industries needed workers with a relatively fixed set of skills and knowledge, it is losing its relevance in an era of innovation, disruption and constant change, where adaptability and learning agility are most needed.

Have you read?

Two things that need to change for the future of education, the world is failing miserably on access to education. here's how to change course, how higher education can adapt to the future of work.

Our current education system, built on the Industrial Revolution model, focuses on IQ, in particular memorization and standardization – skills that will be easily and efficiently supplanted by artificial and augmented intelligence (AI), where IQ alone isn’t sufficient. A good blend of IQ (intelligence) + EQ (emotional intelligence) + RQ (resilience) is critical to unleashing a student’s potential.

Evaluating our current education system against three criteria – job readiness, ability to compete against smart machines for jobs and creating long-term economic value – reveals the following:

- 34% of students believe their schools are not preparing them for success in the job market . We need to fix the bridge from education to employability;

- 60% of future jobs haven’t been developed yet and 40% of nursery-age children (kindergarteners) in schools today will need to be self-employed to have any form of income (Source: WEF Future of Jobs Report). We need to prepare students for jobs that haven’t been created yet and to become entrepreneurs. What we need to learn, how we learn, and the role of the teacher are all changing.

The $1.5 trillion in student debt in the US is the second highest debt after home mortgages . With tuition fees expected to break $100,000 per year , student debt will be crushing for future generations. Even Barack Obama was reportedly paying off student loans in his 40s . With the average new college graduate making $48,400 , many people will be paying off their student loans well into their retirement, hurting their ability to save, buy homes, support their families and contribute to philanthropic efforts.

While we work to transform education, we also need to make it more accessible. According to UNICEF, more than 72 million children of primary education age are not in school, while 750 million adults are illiterate and do not have the ability to improve their and their children’s living conditions . As we take on education transformation, daisy-chaining across three crucial categories (access, equity, quality/impact) is critical for unleashing potential.

Access means ensuring learners everywhere are not prevented by circumstances from being in school and getting an education. Access to education is low in many developing nations, but inequalities also exist within developed countries that are highly stratified socially , for example, in the UK . How do we make education/learning more accessible? What role can technology play? How can countries, particularly developing ones, hold on to top talent to ensure economic progress?

Equity means ensuring every child has the resources needed to get to school and to thrive, regardless of circumstance. While equality means treating every student the same; equity means making sure every student has the support they need to be successful. The essential drivers are fairness (ensuring that personal and social circumstances do not prevent students from achieving their academic potential); and inclusion (setting a basic minimum standard for all students regardless of background, gender or location). This leads to several questions: how do you raise awareness in communities? What role can technology play in creating personalized and differentiated learning so all students get the kind of instruction they need to succeed?

The definition of quality and success has to move beyond standardized test scores to a more holistic measurement tied to life improvements and societal impact. Quality education would provide learners with capabilities and competencies required to make them economically productive, develop sustainable livelihoods, enhance individual well-being and contribute to community. The impact orientation will help shift our gaze away from behaviour and activities (attending school and checking the box) to value-creation environments (from personalized learning and career counselling to job readiness and becoming responsible global citizens).

It’s in everybody’s best interest to solve the global education crisis:

- 13 million US students are likely to drop out of school during the next decade costing the country $3 trillion;

- Compared to high-school dropouts, graduates pay more taxes, draw less from social welfare programmes and are less likely to commit a crime;

- An 8% improvement in US PISA scores in the next 20 years would boost GDP by about $70 trillion in the next 80 years.

“Investing in education is the most cost-effective way to drive economic development, improve skills and opportunities for young women and men, and unlock progress on all 17 Sustainable Development Goals," says United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres .

So let us reset education and learning to meet 21st-century needs , shaping a path from education to employability and economic independence.

Let’s all commit to collectively helping to break a link in the shackles holding education back. Let’s blend the lessons of the past with the technology of the present and future to truly transform education, giving students the ability to think, learn and evolve no matter what the challenges that await them tomorrow and unleash their potential to benefit the world.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Education, gender and work.

.chakra .wef-1v7zi92{margin-top:var(--chakra-space-base);margin-bottom:var(--chakra-space-base);line-height:var(--chakra-lineHeights-base);font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-larger);}@media screen and (min-width: 56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1v7zi92{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-large);}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-ugz4zj{margin-top:var(--chakra-space-base);margin-bottom:var(--chakra-space-base);line-height:var(--chakra-lineHeights-base);font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-larger);color:var(--chakra-colors-yellow);}@media screen and (min-width: 56.5rem){.chakra .wef-ugz4zj{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-large);}} Education, Gender and Work is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-19044xk{margin-top:var(--chakra-space-base);margin-bottom:var(--chakra-space-base);line-height:var(--chakra-lineHeights-base);color:var(--chakra-colors-uplinkBlue);font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-larger);}@media screen and (min-width: 56.5rem){.chakra .wef-19044xk{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-large);}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

The agenda .chakra .wef-dog8kz{margin-top:var(--chakra-space-base);margin-bottom:var(--chakra-space-base);line-height:var(--chakra-lineheights-base);font-weight:var(--chakra-fontweights-normal);} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

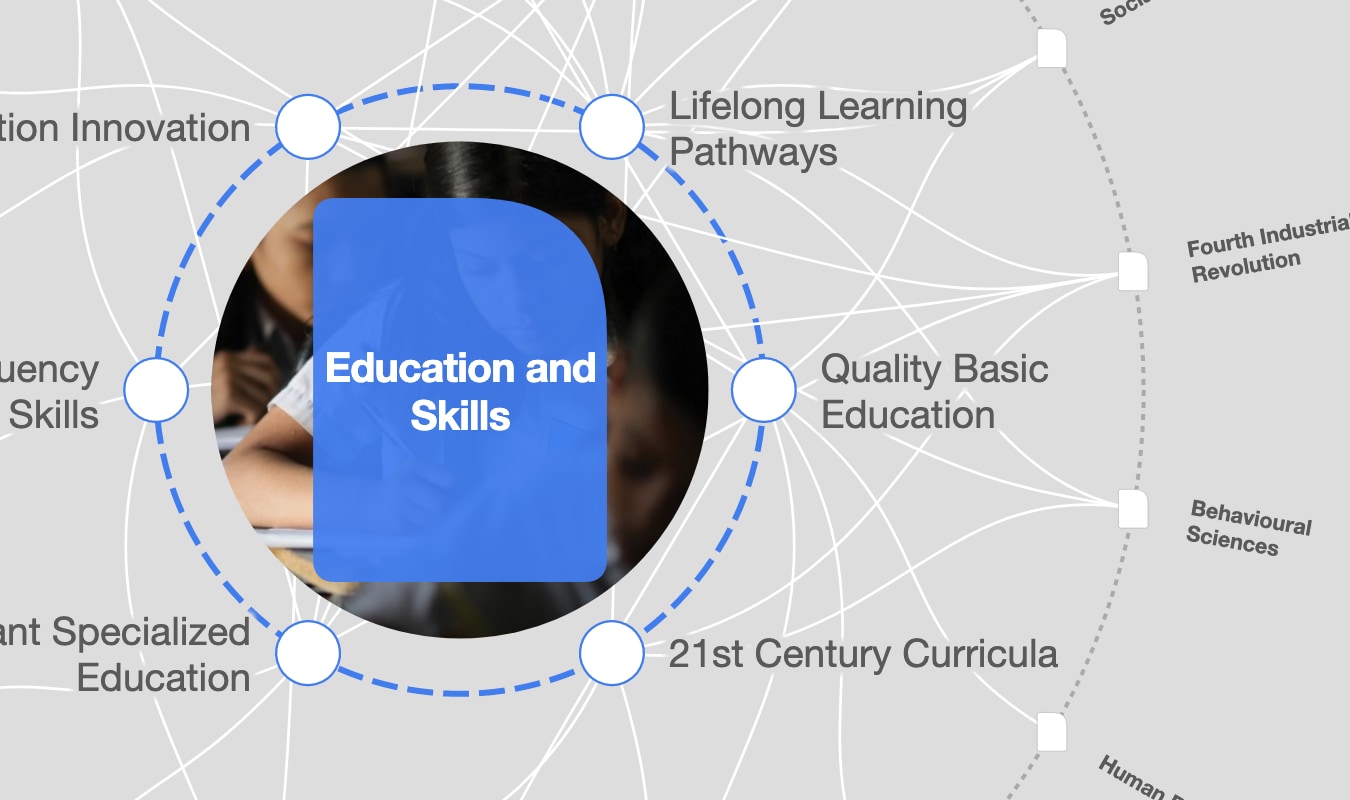

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:flex;align-items:center;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Education and Skills .chakra .wef-17xejub{flex:1;justify-self:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-2sx2oi{display:inline-flex;vertical-align:middle;padding-inline-start:var(--chakra-space-1);padding-inline-end:var(--chakra-space-1);text-transform:uppercase;font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-smallest);border-radius:var(--chakra-radii-base);font-weight:var(--chakra-fontWeights-bold);background:none;box-shadow:var(--badge-shadow);align-items:center;line-height:var(--chakra-lineHeights-short);letter-spacing:1.25px;padding:var(--chakra-space-0);white-space:normal;color:var(--chakra-colors-greyLight);box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width: 37.5rem){.chakra .wef-2sx2oi{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-smaller);}}@media screen and (min-width: 56.5rem){.chakra .wef-2sx2oi{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-base);}} See all

Why younger generations need critical thinking, fact-checking and media verification to stay safe online

Agustina Callegari and Adeline Hulin

October 31, 2024

Skills for the future: 4 ways to help workers transition to the digital economy

From herding to coding: the Mongolian NGO bridging the digital divide

World University Rankings 2025: Elite universities go increasingly global

- IELTS Scores

- Life Skills Test

- Find a Test Centre

- Alternatives to IELTS

- All Lessons

- General Training

- IELTS Tests

- Academic Word List

- Topic Vocabulary

- Collocation

- Phrasal Verbs

- Writing eBooks

- Reading eBook

- All eBooks & Courses

Education System Essays

by Keyla Simoes (Praia Grande, São Paulo, Brazil)

Choice of Subjects at University

by Karlie (China)

Some people think that all university students should study whatever they like. Others believe that they should only be allowed to study subjects that will be useful in the future, such as those related to science and technology. Discuss both these views and give your own opinion. Nowadays, more and more students are unconscious about how to choose their major. They think if they need to choose the subject that they love or choose the subject that is good and useful for the society in the future. It is no doubt that there are some benefits to study a major is about the technology and science. If most of the students study these kinds of major, there will be a sharp increase in the technical development, the productivity will be improved and produce more high-tech products, as a result, the living standard will be better that before and it will have a rise in the economic growth. Moreover, students may get high salary, if they find a job that needs a lot of skill about technology or science. On the other hand, the others think that students need to study the subject that they love it. For example, students choose their favorite subject, they would like to spend more time on their subject that they are interest and they don’t feel boring about their classes, try their best to do their research or lecture, even though the subject is difficult for them, so they could get high mark and get more successful in their major. In addition, different people have different favorite major, not all the students only study technology and science, it can makes the society develop in many kinds of ways, such as literature, art, sports. In conclusion, I believe that students need to choose the subject that they love, the reason for this is students can have more incentive to study and they can have a good mark in their exam. I think university could add some additional subjects about technology or science for students who do not learn these, let students learn some knowledge about technology or science. *** Please provide me with feedback on my Choice of Subjects at University Essay.

Testing and Exams in Education

Hello, can you give me a feedback on my essay please? What should I improve to reach band 7-8? Tests and examinations are a central feature of school systems in many countries. Do you think the educational benefits of testing outweigh any disadvantages? Assessing students includes many methods; however the majority of educational institutions regard examinations as the most efficient. Even though testing system is practiced in many countries and has many benefits, this system has become outdated and dilapidated. The main problem of current educational program is single-disciplinarily system, so it doesn’t take into consideration individual abilities of each student. Mostly, exams are in the written form consisting of tests and theoretical questions, hence practical skills and critical thinking play a minor role in assessment. By cramming for exams scholars remember information only for short period of time, meanwhile practical learning could give a lot more effective results. Another drawback of testing system is inaccuracy of exam results because scholars are pressured under limited time and strict conditions. There were many cases where students passed their exam and scored less than their real knowledge and abilities. Some people claim that written assessment provide effective studying by tracking the progress and enhancing competition among students. However, this can give a rise to conflicts among students or pupils and their parents, inferiority complexes and other consequences. Moreover different attitude of teacher towards pupils can lead to the unfair results too. In conclusion, testing takes the important part in educational system, however it shouldn’t be the most valuable description of student’s knowledge.

Education and a Country's Success Essay

Giving Children Homework

by Miku (tokyo)

Some people believe that school children should not be given homework by their teachers, whereas others argue that homework plays an important role in the education of children. Discuss both views and give your own opinion. Homework has been given in large number of schools so far. However, there are agreement and disagreement in some people. This essay will indicate the both views how homework affects positively to educated students. I believe that doing homework leads their better education and it is highly likely to achieve their lives. Firstly, no homework can save students’ time and it is possible to develop their skills in the other interests. Younger generation have tons of opportunities and flexible mind and also some people do not actually use school subjects in their entire life. For example, many famous entertainers such as singer or dancer are absorbed their artistry in their childhood. So instead of doing homework, skilled person should experience and spend their time what they exactly want to do. On the other hand, to do homework still plays a significant role in teenager’s life. It is because there are only few people can be skilled person and the other ones would fail or suffer in a difficult situation before achievement. Furthermore, the mind of youngsters is changing easily. Moreover, making effort and handling a lot of tasks in schooling will even build a strong personality. Therefore, homework should be given to all students. In conclusion, it depends on the situation and people how they would like to advance their life. However, to manage school homework could be the momentous effect in any work environments. Thus, I will believe that being given homework is much important than without homework in school. [email protected] Thanks

Online Learning Essay

With the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, most schools have had to switch to teaching online. Some people think that online teaching is as effective as in-person instruction, while others think online teaching is inferior. Discuss both these views and give your own opinion. It is considered by some that having online classes are as good as face-to-face classes, while there are others who think having face-to-face classes are better than having online classes. In my opinion, I believe that face-to-face classes are better for practical courses, while online classes are similar to face-to-face classes for theoretical courses. On the one hand, many think online classes are comparable to face-to-face classes. In other words, they think online classes could provide students the same standard of teaching and feedback. Nothing changes except for the medium to deliver the classes. Students would still need to finish assignments, do presentations and sit for examinations. On the other hand, some think online classes are lower in quality. Teaching staffs might not use to deliver lectures or classes through online platforms and ignore some questions from students. Consequently, some students need to spend extra time to email lecturers or teachers to answer their enquiries. Finally, in my opinion, whether face-to-face classes are better or equally efficient as online classes, depends on the major of the students. For example, face-to-face classes are better for students who are studying arts, physical education and chemistry, which required certain practical skills to succeed in their relevant fields. In contrast, online classes are as high quality as face-to-face classes for students who study law, accounting, cultural studies, which required more theoretical knowledge than getting their hands dirty. In conclusion, both teaching methods, either online or in person, could help students to achieve in their studies. It just depends on what students are studying to determine which method delivers better learning quality and experience.

IELTS Essay - Choice of School Subjects

by Ali Almasi (Esfahan, Iran)

Schools should only offer subjects that are beneficial to students’ future career success. Other subjects, such as music and sports, are not important. To what extent do you agree or disagree? It is generally thought that students should only study subjects which are beneficial to their successful future career and other topics like music and sports are not of importance. Personally, I am of the opinion that schools should provide, pupils with a marvelous opportunity to learn different subjects. There are many positive points if schools incorporate are lessons into their curriculum. One of the most important advantages with respect to this view is that it can significantly contribute to the enhancement of children’s creativity. Scientifically speaking, it has been proven that music and sports lessons may afford students the opportunity to develop their efficiency, performance and innovation. As a result, it can be particularly beneficial for them if they have an acquaintance with this type of subjects. Another merit can be ascribed to the fact that music can provide students with assistance to recall satisfactory memories and sports lessons may mitigate the risk of suffering from the infirmities and frailties of old age. Therefore, the more children study art topics during their studies the more they become successful in their occupation in the future. Another benefit in support of this view stems from the familiarity with expressing emotions. In other words, music and sports can boost children’s ability to explain their emotions and display their affection towards each other. Hence, they are competent in leading a tranquil lifestyle fraught with composure. By contrast, there is no doubt that subjects, such as math, chemistry and physics have played a significant role in the future career of children. This is because these subjects are rooted in reality and have a direct impact on all facets of children’s existence. It is true, though, that the brain of students is growing and needs to become acquainted with other courses. There are a large number of illustrations which indicate that children should be at liberty to opt their favorite discipline themselves to become successful, such as Elon Mask and Taylor Swift In conclusion, although educational systems consider subjects in the curriculum that would be useful for future job success of students, other topics like music and sports are of immense significance for them.

IELTS Essay - Compulsory Sport at School

by zaid khan

It is generally accepted that exercise is good for children and teenagers. Therefore physical education and sport should be compulsory for all students in all schools. What is your opinion? Although physical training is beneficial for children and teenagers alike, making it compulsory for all students in all schools is not a good idea. Rather it is the duty of each and every child's parents to ensure that their children get the required fitness education. In today's world, there are many types of schools including those for specially abled children where some pupils may not be able participate in sports due to some disability. Also there are a plenty of games that all played today and it is not feasible for any school to train their pupil for every one of them. For the sake of argument, if we make physical education as a mandatory subject in the curriculum then people will next argue which sport to make as obligatory in schools and that will be a never ending debate. Also, each sport has their specific requirements such as hiring qualified trainers, high-end equipment, open spaces, and quality time which would add to the expenses of institutions and shift the focus from their fundamental duty of imparting scholastic knowledge. Rather, It is the duty of each parents and not the schools to facilitate recreational activities for their children. Every parent should try to encourage their child to be sportive and should try to find which sport interest their child the most. They can then, enroll their offspring to master in his or her favorite play at sport-complexes which are designed for making champions which can never happen in a school. Also some games such as boxing involve a high risk of injury and should only be trained at premises where immediate medical help can be given which again cannot be expected in a school compound. In conclusion, although sports education is good for a child but it should not be made compulsory in a school. Instead parents should take the responsibility of their child's physical fitness and let schools pay attention on children's curricular activities. 329 words 1,939 characters

IELTS Essay - Investing in Computers or Teachers

by Shatha Salman (Jordan)

Computers or Teachers?

Some believe that money for education should mainly be spent on better computers while others believe it would be better spent on teachers. Discuss both views and give your own opinion. There is no doubt education play a crucial role in people’s lives. However, while some think investments in teaching should be towards enhanced technology and up to date computing machines, I would agree with those who argue that it will be a well spent fund if spent on tutors. Opponents point out that increased technology capabilities are important in students’ life cycle. This is because nowadays market requirements are all evolved on acquiring better computer skills. For instance, a student who has dealt earlier years in his education with advanced soft wares will somehow surpass the other. If, in contrast no funds were allocated for such valuable tool, a huge gap will arise later in students’ career. Meanwhile attracting talented tutors with a rich experience and knowledgeable resume will somehow comes in favor of students. In other words these teachers will inherit their lessons and expand learnings if they were paid the salary they deserve and by that they will be motivated to achieve their objectives and deliver the value to students. For example, some teachers connect spiritually with their students and encourage them to unleash the potential inside of them by the skills they already have throughout life. In order to have high maintained educational system, good talents with high level of experience to expand should be first on demand. In conclusion, although developed computers could contribute positively in education process and readiness, in my opinion investing in teachers are more vulnerable.

Band 7+ eBooks

"I think these eBooks are FANTASTIC!!! I know that's not academic language, but it's the truth!"

Linda, from Italy, Scored Band 7.5

Bargain eBook Deal! 30% Discount

All 4 Writing eBooks for just $25.86 Find out more >>

IELTS Modules:

Other resources:.

- Band Score Calculator

- Writing Feedback

- Speaking Feedback

- Teacher Resources

- Free Downloads

- Recent Essay Exam Questions

- Books for IELTS Prep

- Useful Links

Recent Articles

Improve Coherence and Cohesion in IELTS Writing

Oct 27, 24 07:24 AM

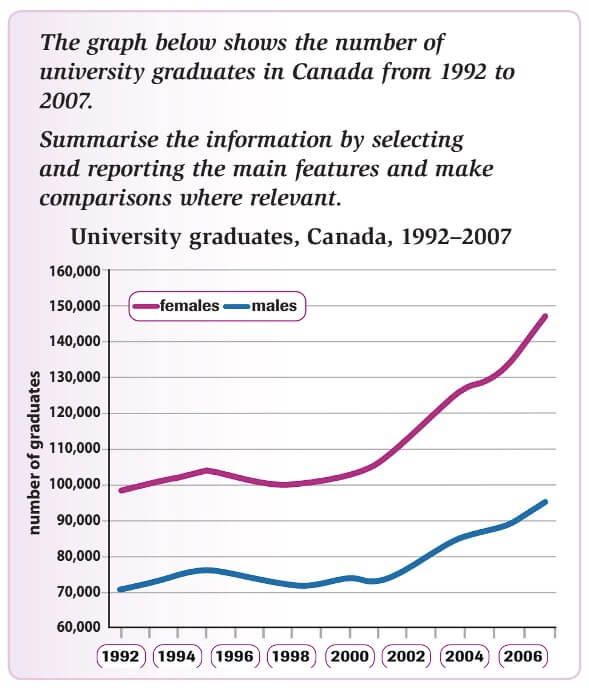

Lesson on Writing IELTS Line Graphs

Oct 15, 24 02:26 AM

Time Management Tips for IELTS

Oct 06, 24 12:59 PM

Important pages

IELTS Writing IELTS Speaking IELTS Listening IELTS Reading All Lessons Vocabulary Academic Task 1 Academic Task 2 Practice Tests

Connect with us

Before you go...

30% discount - just $25.86 for all 4 writing ebooks.

Copyright © 2022- IELTSbuddy All Rights Reserved

IELTS is a registered trademark of University of Cambridge, the British Council, and IDP Education Australia. This site and its owners are not affiliated, approved or endorsed by the University of Cambridge ESOL, the British Council, and IDP Education Australia.

Onlymyenglish.com

Learn English

My School Essay in English (100, 200, 300, 500 words)

Table of Contents

My School Essay 100 Words

My school is a place where I get educated; learn new subjects under the guidance of trained and skilled teachers. I study at a school that is near my home. It is one of the best schools in my entire town. The management of my school believes that it isn’t only academic excellence that we should be after, but also the overall personality development and evolving into a good and useful human being.

The school has two playgrounds – one is a tennis court and the other one is a cricket ground. We also have a nice swimming pool and a canteen. It also has a beautiful garden where students relax and play during recess. Even in games, sports and tournaments, it has made much progress. My school has won many trophies, shields, and medals in many extra-curricular activities. In debates also, the students of my school secure good positions. It is considered to be one of the best schools in my locality.

My School Essay 200 Words

The school is called the educational institution which is designed to provide learning spaces and create an environment for the children where the teaching of the students is under the direction and guidance of the teachers.

My School is one of the best educational institutions where I get an education and make progress towards the goals of my life and make me capable of achieving them. Besides education, there are several significant roles that my school plays in my life. My school is performing well in all fields. It develops my physical and mental stamina, instills confidence, and

gives me tremendous opportunities to prove my skills and talents in different fields. In the academic field, it has made a mark. Its students secure top positions in the board examinations.

I go to school with my other friends. We study in our school in a great friendly environment. We reach school at a fixed time. As soon as we reach we line up to attend the assembly. Attending the school assembly is a wonderful experience. I enjoy for being first in a row in a school assembly. As soon as the assembly ends we rush to our respective classrooms. We take part in all school activities. One of my school fellows is the best singer and dancer. She has recently won the best singer award at the annual arts festival. Our school organizes all-important national events like Independence Day, teachers’ day, father’s day, etc. My school also gives every student abundant opportunities to take part in extracurricular activities like sports and music.

All of us are proud of being a part of it. I am fortunate enough to be a student at this school. I love and am proud of my school.

My School Essay 300 Words

An institution where higher education is taught is commonly called a school, University College, or University. Most countries have systems of formal education, which is sometimes compulsory. In these systems, Students progress through a series of schools. The names for these schools vary by country but generally include primary school for young children and secondary school for teenagers who have completed primary education.

My school is a place where I not only get educated but also get trained in other necessary competitive skills like sports, music, and dance. I am proud of my school because it provides us with all the basic facilities like a big playground, a central library, a big auditorium hall, a science lab, and a good computer lab. That is why my school is rated as one of the best schools in my entire area. My school has produced many great people in my country. It has a big and beautiful building that looks shiny from far away. I reach my target at a fixed time. I came to school with other friends of mine. We happily enter the schools with great confidence. We take part in a school assembly and then we move into our classrooms.

This all is done by a very efficient and well-trained teaching staff of my school. The best schools are those that make the students the best and the best school is made by the best teachers. We study under the guidance of the best teachers. My school has a dedicated teacher for all the subjects as well as extracurricular activities like music and sports. I consider my school as the best school because it supports and encourages every student to do their best and make progress. Fortunately, my school provides the best environment, the best teachers, and the best facilities.

Our Class teacher greets us daily and asks about us. He is quite a cool and kind man. He entertains us along with teaching his subject. We learn a lot of things like discipline, self-help, confidence, and cooperation here. As I enter my classroom I feel quite happy and relaxed.

My School Essay 500 Words

The place where children as the leaders of tomorrow study and where the future of the nation is shaped are called schools. Education is an essential weapon for tomorrow, so the good schools of today are important for the best future of a nation. Schools are the center of learning where we attend classes on various subjects, interact with the teachers, get our queries

answered, and appeared in exams. In my school, learning is more like a fun activity, because of the extra-talented teaching staff.

My school is a government primary school located on the outskirts of the city. Usually, when people think about a government school, they perceive it to be at an isolated location and have poor basic amenities and teaching facilities. But, despite being a government school, my school defies all such speculations. Teachers of my school are not only knowledgeable about the subjects they teach but also are skilled enough to teach through fun activities. For example, our physics teacher explains every concept by stating real-life examples that we could relate to. This way we not only understand the subject better. Moreover, not a moment I remember, when any teacher had ever replied rudely to any of the students. They always patiently listen and provide answers to all the queries posed to them. Learning at my school is fun and it is made possible only because of the teachers.

My school is very important in my life, in a way even more than my family. My family gives me love, care, and affection, and provides for all my other essential needs. But, all of this isn’t enough to make me a good human being and succeed in life. Favorably, I am lucky enough to be enrolled in a prestigious school, and gaining a wonderful education, looking forward to realizing my dreams one day. The most necessary for success in life is education, and only my school provides it to me. Without my school and the education that it gives, I would be like a confused and wandering soul, almost aimless in life.

My school helps with my educational and overall personality development. It imparts education through classes, tests, and exams to teach me how to conduct myself confidently. It just feels so great to be in my school and be a part of everyday activities, be it lectures, sports, or Something else. While in school, I always feel happy, confident, enthusiastic, and loved. I make friends at school, those whom I will never forget and will always love them. My family supports my materialistic needs, but school is the place where my actual physical, social, and mental development takes place. I know that every question that crosses my mind will be answered by my teachers. I also know that my school friends will always be at my side whenever I need them to be. As much as the studies, my school also stresses much on These activities as the management thinks that extracurricular activities are very essential for our overall personality development. My school provides dedicated teachers and staff for each extracurricular activity. We have a big sports ground with kits for all the major sports; a covered auditorium for dance and music and a separate basketball court.

The role my school plays in my personality development is fantastic. It not only imparts education in me but also teaches me how to conduct myself and how to behave decently and properly. I get trained in all the other necessary skills of life, like how to keep calm in challenging situations and help others as well. My school teaches me to be a good and evolved human being, to stay composed and progressive always. It also teaches me to be kind and generous to others and not differentiate them based on their caste, religion, ethnicity, or other divisions. These are some of the most essential personality traits that my school imparts to me, something that I will always be thankful for. Every time I think of my school, I think of it as a temple of education. A temple, where my soul meets education, making my life more meaningful and useful to society and the nation as well. It is a place where my aspirations get a wing and I get the strength and confidence to realize them. No other place in the entire world could replace my school and the role that it plays in my life. I will always be thankful to my friends, teachers, and the staff of my school, for making it such a comfortable and Educational place of learning.

- My Mother Essay

- Republic Day Essay

- Mahatma Gandhi Essay

- Essay on Holi

- Independence Day Essay

- My Family Essay

You might also like

Online education esaay in english, independence day essay in english, my hobby essay in english, essay on swami vivekananda in english for students, my teacher essay in english, my favourite game essay.

Essay on How to Improve Our Education System

Students are often asked to write an essay on How to Improve Our Education System in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on How to Improve Our Education System

Identifying the issues.

Our education system has some flaws. It’s often focused on rote learning, not creativity. Also, it doesn’t cater to different learning styles.

Adopting a Holistic Approach

We should focus on holistic development, not just academics. This includes sports, arts, and social skills.

Personalized Learning

Every student learns differently. So, we should use technology to personalize education.

Teacher Training

Teachers need continuous training to stay updated. More resources should be allocated for this.

Parental Involvement

Parents should be more involved in their child’s education. This can improve learning outcomes.

By addressing these issues, we can enhance our education system.

250 Words Essay on How to Improve Our Education System

Introduction.

Education is the cornerstone of societal progress. However, in the face of rapidly evolving global challenges, our education system must adapt and innovate. To improve our education system, we need to focus on three key areas: curriculum development, teaching methodologies, and assessment strategies.

Curriculum Development

Building a relevant curriculum is vital. It should not just be limited to textbook knowledge but also include real-world issues, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills. Incorporating technology and digital literacy into the curriculum is essential to prepare students for the digital age.

Teaching Methodologies

Traditional lecture-based teaching methods need to evolve. Active learning strategies such as project-based learning, flipped classrooms, and collaborative group work should be encouraged. These methods stimulate student engagement and foster a deeper understanding of the subject matter.

Assessment Strategies

Assessment should be more than just testing memory. Evaluations should measure a student’s understanding, creativity, and ability to apply knowledge. Formative assessments, which provide ongoing feedback, can help students identify their strengths and areas for improvement.

In conclusion, to improve our education system, we must revamp our curriculum, adopt innovative teaching methods, and revise our assessment strategies. These changes will equip students with the skills and knowledge necessary to thrive in the 21st century.

500 Words Essay on How to Improve Our Education System

Education is the cornerstone of society, providing the foundation for personal growth, social development, and economic prosperity. However, the current education system, predominantly based on rote learning and standardized tests, has been criticized for not adequately preparing students for the challenges of the 21st century. This essay explores how we can improve our education system to foster creativity, critical thinking, and lifelong learning.

Embracing Technology

Technology has revolutionized every sector, and education should be no exception. Integrating technology into the classroom can enhance learning by making it more interactive and engaging. For instance, digital platforms can offer personalized learning experiences tailored to each student’s pace and level of understanding. Moreover, virtual reality and augmented reality can provide immersive learning experiences, making abstract concepts more tangible.

Student-Centered Learning

The traditional teacher-centered model should be replaced by a student-centered approach, where students take active roles in their learning process. This approach encourages students to question, explore, and discover, fostering critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Additionally, project-based learning, where students work on real-world problems, can make learning more relevant and meaningful.

Curriculum Reform

The current curriculum heavily emphasizes theoretical knowledge, often at the expense of practical skills. A reformed curriculum should strike a balance between the two, incorporating subjects like financial literacy, digital literacy, and soft skills. Furthermore, the curriculum should be flexible enough to accommodate the fast-paced changes in the job market, equipping students with the skills needed for jobs that do not yet exist.

Assessment Reform

Assessment methods need to evolve beyond standardized tests, which often measure rote memorization rather than understanding. Alternative assessment methods like portfolios, presentations, and peer assessments can provide a more comprehensive picture of a student’s abilities. These methods not only assess knowledge but also skills like communication, collaboration, and creativity.

Teacher Training and Support

Teachers play a pivotal role in the education system. Therefore, their training and support should be a priority. Regular professional development programs can equip teachers with the latest pedagogical strategies and technological tools. Moreover, teachers should be given adequate resources and autonomy to innovate and adapt their teaching methods to the needs of their students.

Improving our education system is a complex task that requires the collaboration of educators, policymakers, parents, and students. While the steps outlined above are not exhaustive, they provide a starting point for transforming our education system into one that nurtures creativity, critical thinking, and lifelong learning. By doing so, we can ensure that our education system prepares students not just for exams, but for life.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Education Is the Key to Success

- Essay on Purpose of Education

- Essay on Right to Education

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- About Project

- Testimonials

Business Management Ideas

Essay on My School

List of essays on my school in english, essay on my school – essay 1 (250 words), essay on my school – essay 2 (250 words), essay on my school – teachers, schedule and conclusion – essay 3 (300 words), essay on my school life – memories and conclusion – essay 4 (400 words), essay on my school – introduction, environment and teachers – essay 5 (500 words), essay on my school – surroundings and structure – essay 6 (600 words), essay on my school – infrastructure and academic activities – essay 7 (750 words), essay on my school – introduction, discipline and conduct – essay 8 (1000 words).

A school is a medium of learning for children and is often regarded as a place of worship for the students. Writing an essay on my school is quite common among students. Here we have essays on My School of different lengths which would prove quite helpful to your children. You can choose the essay as per your length requirement and you shall find that essays have been written in quite easy to understand yet crisp language. Moreover, the essays have been written in such a manner that they are suited for all classes, be it the junior school or the senior classes.

Introduction:

Education in India has made significant progress over the years. Both private and public schools facilitate education for Indian children and follow the same regulations for teaching curriculum. All schools incorporate extracurricular activities into the school systems, which motivates the learners and help them in realizing their talents and building their personalities. Schools are funded by the three levels i.e., the state, local and central levels. Schools in India cover primary, secondary and post-secondary levels of education. The highest percentage of schools offer primary education.

Crescent public school:

My school is a public institution that is located in Delhi. Crescent Public school was established in 1987 and it has been in operation ever since. The school is well equipped in terms of facilities as we have a gym, a library, a nice playground, our classes are modern, the buses are adequate and labs are functional. I joined this school in the year 2016 and I have been able to learn a lot about the school. The school is affordable and the education I have received is quality because I have developed in all aspects of life.

Not only is the school excellent in education, but also excellence in sports is achieved. I have always loved playing tennis. I participate in the school’s tennis competitions. In the year 2017, we won the Bronze medal in the national tournament by CBSE. This year, we secured third position in the same sport, which was an exciting experience for both the students and the teachers. It has been a great experience especially with support from our teachers.

Introduction

My School, St. Mary’s Anglo Indian Higher Secondary School is located in Armenian Street, at the heart of Chennai City. It is one of the oldest schools for boys in India, established during the British rule.

“Viriliter Age” which means “Act like a Man” is the motto of my school. It aims to provide a family atmosphere for us to become intellectually enlightened, spiritually profound, emotionally balanced, socially committed and morally responsible students.

Though built during the colonial rule, the buildings are airy and comfortable. The Management regularly upgrades the facilities and uses uptodate technology to run my school. It has a large playground, well-stocked library and well-equipped science laboratory.

Daily Schedule

A typical day at my school starts with the assembly at 8:30 AM. We render our prayers, hear moral and other instructions from teachers. Apart from regular academics through the day, our time table is spotted with periods for music, games, project work etc. We undertake sports activities for an hour after the last period, which gets over at 3:30 PM.

Co-Curricular Activities

According to our interests, we are encouraged to participate in Arts & Crafts, NSS, Scout etc., and become members of various Clubs and Associations. Medical Teams and Psychologists visit us regularly to aid our holistic growth.

I love my school, teachers and friends very much. I aim to complete my studies with laurels. I wish to shine brightly in my higher studies and career, to spread the pride of my school.

My school is situated in the foothills of Yercaud in Salem district, Tamil Nadu and is called “Golden Gates”. It fosters a love for learning and this is clearly seen in its location which is unlike any other school. It is well placed in a natural setting with hills all around and streams flowing nearby. Inside the campus too, there is abundant nature with almond trees lining the divide between buildings and many shrubs and plants bordering different sports grounds. This facilitates practical study and most of our science and geography classes happen outside. Our Principal and Correspondent have made it their mission to create a healthy and organic atmosphere for learning.

My school teachers come in all shades of character. There are those teachers who have great love for the subject they teach and impart that love to us students too. Even a student who hates that particular subject will start liking it, if he/she sits in their classes. Next, we have jovial teachers who are cheerful in nature and radiate joy to all around them. They are friendly and compassionate and are the go-to people for all students when any trouble comes up. Then, there are the strict teachers who are rigorous in nature and make sure discipline and decorum is maintained throughout school. They are the ones who keep rule breakers and unruly students at bay. Together, our teachers form the heart and soul of the school.

On weekdays, typical school schedule happens in my school too. We start our day with a prayer assembly. With a short news time, prayer song and any specific instructions for the day, we depart to our respective classes. After four periods of subjects with a short snack break in between, we break for lunch. Lunch is when the whole school comes alive with shouts and screams of laughter as we all socialise with fellow classmates. Then follows three periods of subjects in the afternoon and off we leave to our homes. But everybody’s favourite is Saturday! The day dedicated for extracurricular activities. There are many clubs for Music, Dance, Gardening, Math, Drama, Science, Eco, etc… Each student is to pick two clubs and partake in them in the morning. Post lunch we have various sports clubs to participate in. On the whole, Saturdays are packed with play and fun.

Conclusion:

In today’s world, with the hustle and bustle of city life, my school is a wonderful place to learn and grow. It enriches our journey through education by blending in play, fun and nature.

Be a light to be a light – is the touching inscription welcomes all of us at the entrance gate of our school. My school – always filled with a treasure trove of memories, which is the best part of my life. It was indeed a paradise, located in the high ranges of the Western Ghats. Far away from the buzzing urban setting, my school situated amidst lush greenery in a calm and serene atmosphere.

My alma mater did mold me into a responsible citizen and an aspiring individual. It witnessed my metamorphosis from an ignorant toddler into a bold young adult with an unquenchable thirst for knowledge. It gifted me with fourteen years of reminiscence to cherish for a lifetime.

Only fond memories – a home away from home:

For me, it was a home away from home. Even the trivial matters about the school became part and parcel of my life. Each classroom that I have sat in had made an indelible mark on my memory. The see-saw in the kids’ park, the class assemblies, physical training classes, lunch break chit chats, art competitions, sports competitions, silly fights with friends, school anniversaries, tight special classes, records, labs, exams… all left deep imprints in my mind.

The most significant part of my school memory revolves around the teachers. They are the incarnation of the divine. They kindle our lives with the bright light of knowledge and help us to imbibe the values to live. We cannot, ignore the contributions of the teachers, as they played a considerable role in molding a student’s life. At first, a student tries to imitate the teacher and gradually makes them the role models.

A teacher plays a vital role in guiding the students to a righteous path. The moral values inherited during school life can last for a lifetime. The way the teachers nurtures and loves the students is heart rendering. We can openly share our anxieties and frustrations with our teachers.

Most teachers were more like best friends. We used to celebrate Teachers Day every year in a grandiose fashion. Our dear teachers always put forth spell spindling performance and enthralled the students with a real visual treat. Their blessings can have a huge influence on anybody’s lives. Even after you go to pursue your higher studies, you can always come back to your school and cherish your good old days. Our teachers are so overwhelmed to see us and are curious to know about our accomplishments.

Besides all these, another best thing about school is our friends. It is the place where any human begins to socialize. You enter into a new realm of social life at school. Hence your acquaintance at school becomes family. As you grow up, the influence of your peer group holds a vital role in your character formation. The hilarious moments with the friends are irreplaceable.

Hence, school life turns out to be a microcosm of the real life wherein you laugh, cry, forgive, forget, interact, react, adjust, learn, teach, observe, take risks, transform and finally evolve into fully fledged individual ready to step out into the complex world.

Education is the bedrock of the society. Any society that wants to break new grounds in science and art has to invest in its education. Though education can be attained both formally and informally, formal education through schools occupies the large chunk of the learning process of any country.

My school is by a large margin one of the best places to attain formal education. While the above statement might sound bold, this article would explain the reasons why my school can back up the bold statement. Features possessed by my school smoothens the learning curve and takes stress away from education.

The Environment:

Assimilation becomes difficult when learning is conducted in a toxic environment. Other times, the terrain isn’t toxic but lacks the right appeal to the average student. Student want to be welcomed with the right colours, feel comfortable when they sit or draw inspiration from the general architecture of their school.

My school embodies the above mentioned qualities and more to the smallest of details. The classrooms are decorated with bright colours to cheer up the student’s mood; the playground is designed to relax each student after participating in mentally challenging mind exercise and the general design of the school subconsciously makes every student feel at home.

The Teachers:

Teachers can either make or break any school. Some grumpy, others dull, and then you have those who simply lack the techniques of teaching. While some concepts are easy to learn, other concepts require a teacher who has mastered the art of teaching to drive the point home with each student.

My school possesses experienced teacher who could honestly be motivational speakers when they want to be. They are witty, smart and full of charisma. Also, while they can be playful, they ensure that the message doesn’t get lost. To sum it up, teachers in my school hold themselves to the best moral standards. These values are innocuously instilled in the student while they learn academic concepts.

The Students:

There simply can be no school without the student. No matter how nicely decorated a school is, the quality of its teachers or management, it would all go to waste without bright student flooding the classes on a daily basis.

While abundance of vibrant student can be found at my school, the strength of the student does not lie solely in their numbers. Students at my school make the job of teachers easy. They are attentive in class, pay attention to detail and they have a knack for finishing task in record time.

The conduct of student at my school is second to none. The students are courteous to each other and their superiors. Also, they maintain the highest level of decorum in the classroom and beyond.

All the good things about my school cannot be exhausted in this short article. Also, after all has been said and done, the pertinent question is whether or not I love my school enough to recommend it to others. The answer to this question is definitely in the affirmative.

School is an integral part of everybody’s life. It helps in forming and building the base of child’s future. The students that are genuinely concerned to learn might build healthy practices merely in the schools. In my school, I was educated about the ways through which I can move in the society, progress in my life and behave with others.

My school was quite grand and big. There were three storeys and wonderfully constructed building in the school. It was situated in the middle of my city which was quite close to my home. I used to go there by walking. It was one of the most excellent schools in the entire town in which I was living.

Surroundings of My school:

The site of my school was very quiet as well as pollution free. There were two stairways at both ends that make me reach to each floor. The school was well furnished including a well-instrumented science research laboratory, a big library, as well as one computer laboratory at first floor. There was a school lecture theatre located on the ground floor in which the entire annual meetings and functions take place.

Structure of my school:

The head office, principal offices, staff room, clerk room, and common study room are situated on my school’s ground floor. Moreover, there were the stationery shop, school canteen; skating hall and chess room that were located on the ground floor.

My school possesses two large concreted basketball courts opposite the office of school principal whereas the field of football located at its side. There was a tiny green garden facing the head office. It was full of bright flowers and pretty plants that increase the whole school beauty. During my time, there were around 1600 students at my school. All the students perform quite well in any inter-school competitions.

Standard of education:

The education standards of my school were quite inventive and advanced that benefit me in understanding any difficult subjects quite effortlessly. Our professors explain us everything very genuinely and try to let us know all the things practically. My school always get the first rank in any inter-school cultural activities.

All the significant days of the year like teacher’s day, sports day, parent’s day, anniversary day, children’s day, republic day, founder’s day, Christmas day, independence day, mother’s day, happy new year, annual junction, Mahatma Gandhi birthday, etc., were celebrated in my school in a magnificent way.

My school’s atmosphere was very delightful as there were lots of greenery and scenic beauty. There was a big size garden along with the pool having frog, fish, trees, colorful flowers, green grass, and decorative trees, etc. My school offers the programme’s facility to the students belonging to the class nursery to class 12th. Our school’s principal was very strict regarding hygiene, discipline, and cleanliness.

Other facilities:

Students in my school also get the facility of the bus that helps them in reaching the school from far away places. The entire students used to accumulate in the play area during the morning time for the prayer and then go back to their particular schoolrooms. There were different teachers for the diverse subjects in my school such as Math, P.T., Hindi, English, G.K, Marathi, geography, history, drawing and crafts, science, and many more.

We used to have numerous co-curricular activities in my school like scouting, swimming, N.C.C, skating, school band, dancing, singing, etc. All those students who had prejudiced behavior and do disobedient activities were penalized by the class teacher according to the norms of my school. We also get a small lecture daily from our principal for around 10 minutes regarding the etiquette, character formation, moral education, respecting others and acquiring good values. Thus, I can say that what I am today is only because of my school which is the best school according to me.

I am a proud student of Delhi Public School, Mayapuri. My school is located quite close to my home, at a walking distance of 5 minutes. My school positions high among the composite state-funded schools of Delhi. Late Sh. Ram Gopal, the founder leader of Seth Sagarmal trust is the zenith body behind the establishment of this school. The founder administrator Sh. Ram Gopal was a visionary and a philanthropist and he had a fantasy for giving quality education and great foundation with the goal that the kids from the cross segment of the general public could get great training and turn into the respectable nationals of the nation. His fantasy was acknowledged when Delhi Public School, Mayapuri was built up in the year 1991 and spread over 4 acres of land. He used to tell during the assembly meetings that this school has been set up with a mission to give quality training gelled with moral qualities and has the vision to encourage and develop the intellectual and creative abilities in us. Our teachers at Delhi Public School plan to make a solid society by giving comprehensive training keeping in view the changing patterns in worldwide instruction and guide us accordingly.

Infrastructure:

My school is situated on a plot of 4 acres of land out of which 2 acres of land is for the building and remaining 2 acres of land is for the playground and other open-air exercises. Other than brilliant class empowered classrooms, my school building contains the accompanying Lab (Language, General Science, Physics, Chemistry, Biology, Maths and Computers), Library, Multipurpose Hall, Music, Dance and Drama Room, Workmanship Room, Sports Room, Yoga Room, Hospital/Medical Room regulated by full time qualified specialist and helped by an attendant and Staff Rooms (separate staff spaces for various dimension of educators). My school transport has 6 different routes which cover nearly most of Delhi making it convenient for students from all areas to reach the school on time.

The Atmosphere of My School:

The atmosphere of my school is superb with bunches of natural greenery and scenery. There is a vast ground surrounded by beautiful trees and full of green grass for us to play during our PT periods. Different things like an enormous playground, vast open spaces all around the school give my school a characteristic marvel. There is an office of cricket net, basketball court and skating ground too. My school pursues CBSE board standards. My school gives the education to students of all caste and creed from nursery to twelfth class. My school principal is extremely strict about school control, cleanliness and neatness.

Academic Activities in My School:

The academic norms of my school are exceptionally inventive and imaginative which enables us to understand any difficult issue effortlessly. Our teachers show us earnestly and let us know everything essentially. My school positions first in any program like between school social interests and sports exercises. In my school we celebrate all important days and events of the year such as Sports Day, Teacher’s Day, Parents’ Day, Children’s Day, School Anniversary Day, Founder’s Day, Republic Day, Independence Day, Christmas Day, Mother’s Day, Annual capacity, Happy New Year, Mahatma Gandhi Birthday, and so on in a fabulous way.

We take part in the co-curricular exercises, for example, swimming, exploring, N.C.C., school band, skating, singing, moving, and so on. Students having unjustifiable conduct and unrestrained exercises are punished by the class educator according to the school standards. Our in charge ma’am takes classes of each student occasionally in the gathering corridor for 10 minutes to manage our character, behaviour, moral instruction, gaining great qualities and regarding others. Our educational time is exceptionally fascinating and charming as we do lots of inventive and useful works with the help of our teachers.

Why I Worship My School?

My school resembles a temple where we go every day, appeal to God and study for 6 hours every day. My teacher is exceptionally decent and understanding. My school has strict standards of study, cleanliness and uniform. I just enjoy going to school every day as my mom says that it is exceptionally important to go to class daily and study. This is very important for my bright future and my journey towards becoming a good human being. My School is a temple of realizing where we are creatively engaged through the learning procedure. We learn different things too with our examination like control, conduct, act well, reliability and a lot more manners. In this way, my school is the best school in the world.

We all have many sweet and sour memories of our school. Many of us complete our school education from one school but some students like me have to change more than a few schools. School leaves a great impact on our minds. It affects our way of thinking and teaches us to live in the outside world. No wonder it is called the second home of a child.

I too admire my school. Although it has also been two years since I started studying here, there are many kinds of emotions I have developed for my current school. Basically, I belong to the colorful state of Rajasthan. But due to some family reasons, I had to come to Bhubaneswar. It is the capital city of the state of Orissa.

Early Days at My School:

I started my studies here as a student of standard 7. Clearly, there were many cultural differences between my past school and this one. The language, the climate, the food, and the ways of interaction, everything was different here. For the first few months, it was hard for me to adjust in a completely new environment. But slowly, it started to feel familiar.

The Atmosphere:

My classmates and subject teachers have been very supportive. It’s a co-ed school that means both girls and boys sit together and interact with each other frankly. Our school has a great building. It is situated at the heart of the city, away from the residential areas of the town. We go to school by bus.

Teachers at my school come from different parts of the country. My English teacher is a south-Indian whereas my science teacher is a highly reputed lady who came from America and settled in India a few years ago. She is a visiting faculty and teaches us out of her passion for the teaching job.

The students in my school belong to different types of families. Some are from a very simple family. And some are from highly reputed and educated families. For example, the parents of one of my classmates are scientists and parents of another classmate are lecturers. But all the students are treated equally in my school and this is what makes me really proud of my school.

Our School Campus:

My school has a three-floor building. All the classrooms here are large and well-maintained. They are always clean. Huge windows in the class allow sufficient sunlight into the rooms. In summers, we also use the air conditioning in the school as the climate here is quite hot and humid.

We also have a huge playground in the school where our daily assembly and all the other activities take place. In the morning assembly, everything is organized by the students only. From playing the instruments to reading the news and helping students make a line to their classrooms, students take care of all the tasks.

What I Enjoy the Most at My School:

It is a day-boarding school. So, all the children get their breakfast and lunch from the school mess itself. The meals served here is hot and fresh. You can get extra servings as many times as you like. Although in the beginning, it was new to my taste buds, I started to like the Oriya cuisine very soon.

There are many extra-curricular activities taught to the students here. To name some, we have a traditional Oriya dance class. Then, there are self-defense classes and an additional class to learn a foreign language of your choice.

Discipline and Conduct:

Discipline and cleanliness form a great part of my school culture. Every day, the seniors form a group for hygiene checking of the juniors. The responsibility of each senior student is fixed. From the shoes to nails and clean dress, everything is checked properly.

The classes in my school start from play way and up to standard 10. Sincerity and punctuality are the key habits of my school. Even the teachers and kids from the lower classes come to school on time and follow every rule.

Once we get inside the school premises, it is not allowed for us to talk in our mother tongue. All the students have to talk to each other in English. And the rules about it are very strict. Though it may sound a severe rule, it has improved our spoken English in a great way.

Extra-curricular Activities:

Our principal likes discipline but she also shows us a lot of affection and warmth. The students can directly go to her for sharing their problems. She also makes sure that we enjoy the teaching of our teachers and not get bored. That is why occasional trips are arranged for us to explore the nearby cities, which I enjoy a lot.

I also look forward to the annual sports day organized at my school. There are so many sports activities to cheer us up and keep our mind and body healthy. I also participate in the annual functions of my school. It is organized at the biggest auditorium in Bhubaneswar. We practice for several days before the final performance on the stage.

My Sweet Memories at the School:

Last year, my classmates and juniors made my birthday so special. My desk was filled with gifts and greeting cards. They showered me with so much love and affection. When I was new here, all my classmates were very helpful and made it easy for me to settle here without much of a problem.

They are also kind enough to teach me their local language ‘Oriya’. With time, I have learned to read and write the basic words and sentences in the language. Our school also introduced us to the habit of writing and sharing letters with our pen-pals.

My school has taught me many valuable such as to help others, to not make fun of others, respecting the elders and loving the young ones. Over time, I have collected many precious memories here and feel grateful to God for allowing me such a rich learning environment.

I would always love my school and no matter where I go, I will always be proud of it all my life.

Get FREE Work-at-Home Job Leads Delivered Weekly!

Join more than 50,000 subscribers receiving regular updates! Plus, get a FREE copy of How to Make Money Blogging!

Message from Sophia!

Like this post? Don’t forget to share it!

Here are a few recommended articles for you to read next:

- Essay on Success

- Essay on My Best Friend

- Essay on Solar Energy

- Essay on Christmas

No comments yet.

Leave a reply click here to cancel reply..

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Billionaires

- Donald Trump

- Warren Buffett

- Email Address

- Free Stock Photos

- Keyword Research Tools

- URL Shortener Tools

- WordPress Theme

Book Summaries

- How To Win Friends

- Rich Dad Poor Dad

- The Code of the Extraordinary Mind

- The Luck Factor

- The Millionaire Fastlane

- The ONE Thing

- Think and Grow Rich

- 100 Million Dollar Business

- Business Ideas

Digital Marketing

- Mobile Addiction

- Social Media Addiction

- Computer Addiction

- Drug Addiction

- Internet Addiction

- TV Addiction

- Healthy Habits

- Morning Rituals

- Wake up Early

- Cholesterol

- Reducing Cholesterol

- Fat Loss Diet Plan

- Reducing Hair Fall

- Sleep Apnea

- Weight Loss

Internet Marketing

- Email Marketing

Law of Attraction

- Subconscious Mind

- Vision Board

- Visualization

Law of Vibration

- Professional Life

Motivational Speakers

- Bob Proctor

- Robert Kiyosaki

- Vivek Bindra

- Inner Peace

Productivity

- Not To-do List

- Project Management Software

- Negative Energies

Relationship

- Getting Back Your Ex

Self-help 21 and 14 Days Course

Self-improvement.

- Body Language

- Complainers

- Emotional Intelligence

- Personality

Social Media

- Project Management

- Anik Singal

- Baba Ramdev

- Dwayne Johnson

- Jackie Chan

- Leonardo DiCaprio

- Narendra Modi

- Nikola Tesla

- Sachin Tendulkar

- Sandeep Maheshwari

- Shaqir Hussyin

Website Development

Wisdom post, worlds most.

- Expensive Cars

Our Portals: Gulf Canada USA Italy Gulf UK

Privacy Overview

- CBSE Class 10th

- CBSE Class 12th

- UP Board 10th

- UP Board 12th

- Bihar Board 10th

- Bihar Board 12th

Top Schools

- Top Schools in India

- Top Schools in Delhi

- Top Schools in Mumbai

- Top Schools in Chennai

- Top Schools in Hyderabad

- Top Schools in Kolkata

- Top Schools in Pune

- Top Schools in Bangalore

Products & Resources

- JEE Main Knockout April

- Free Sample Papers

- Free Ebooks

- RD Sharma Solutions

- Navodaya Vidyalaya Admission 2024-25

NCERT Study Material

- NCERT Notes

- NCERT Books

- NCERT Syllabus

- NCERT Solutions

- NCERT Solutions for Class 12

- NCERT Solutions for Class 11

- NCERT solutions for Class 10

- JEE Main Exam

- JEE Advanced Exam

- BITSAT Exam

- View All Engineering Exams

- Colleges Accepting B.Tech Applications

- Top Engineering Colleges in India

- Engineering Colleges in India

- Engineering Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- Engineering Colleges Accepting JEE Main

- Top IITs in India

- Top NITs in India

- Top IIITs in India

- JEE Main College Predictor

- JEE Main Rank Predictor

- MHT CET College Predictor

- AP EAMCET College Predictor

- GATE College Predictor

- KCET College Predictor

- JEE Advanced College Predictor

- View All College Predictors

- JEE Advanced Cutoff

- JEE Main Cutoff