- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Don't Miss a Post! Subscribe

- Educational AI

- Edtech Tools

- Edtech Apps

- Teacher Resources

- Special Education

- Edtech for Kids

- Buying Guides for Teachers

Educators Technology

Innovative EdTech for teachers, educators, parents, and students

18 Effective Classroom Motivation Strategies

By Med Kharbach, PhD | Last Update: August 19, 2024

Motivation is one of the key concept in psychology. It is mainly concerned with the why and how humans think and behave as they do. Its significance is particularly pronounced in the realm of classroom learning, where it’s often invoked to explain the successes and failures in learning processes.

Research proved time and again that well-designed curricula and effective teaching methods are not enough to drive students motivation. It takes an integrated and holistic approach that considers both intrinsic and extrinsic factors to enhance students motivation and drive their engagement (Dôrnyei, 2005).

So what are some of these classroom strategies that drive students motivation?

Before we delve into these strategies let me clarify something here: when we talk about motivation strategies we need to differentiate between instructional interventions and self-regulating strategies. Instructional interventions as Guilloteaux and Dörnyei (2008) state are “applied by the teacher to elicit and stimulate student motivation”, and self-regulating strategies “are used purposefully by individual students to manage the level of their own motivation” (p. 57)

In this post I am primarily concerned with instructional interventions, that is, those strategies, you as a teacher and educator can use in your teaching practice to drive students motivation and enhance their engagement.

Related: Great Motivational Videos for Students

Aspects of Motivation

In his paper “ Student Motivation and the Alignment of Teacher Beliefs “, Weisman (2012) provides an insightful overview of different aspects of motivation in the educational context. Two aspects are of particular interest to us in this context: intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.

Intrinsic motivation, a key component in learning, is driven by a natural curiosity and an inherent interest in a subject. This form of motivation manifests in two distinct ways: individual interest , where a child’s innate desire to learn plays a central role, and situational interest , spurred by environmental factors that pique one’s curiosity.

On the other hand, extrinsic motivation revolves around external rewards. However, as Weisman contends, the impact of these rewards is nuanced. While certain types of verbal rewards might bolster intrinsic motivation, most external rewards, particularly tangible or performance-based ones, can paradoxically undermine it. This highlights the delicate balance between internal drive and external incentives in the context of motivation.

Teacher Practices That Enhance Student Motivation

In the insightful work of Weisman (2012), several key practices are identified that significantly enhance student motivation. These practices include:

- Creating Caring Environments : Positive student-teacher relationships are crucial.

- Empathy and Understanding : Understanding students’ lives and affirming their interests can significantly influence motivation.

- Providing Choice and Responsibility : Letting students make choices about their learning enhances motivation.

- Hands-On Activities : Encouraging investigative or experiential learning activities helps in knowledge construction.

Classroom Motivation Strategies

Drawing on the insightful work of Guilloteaux & Dörnyei (2008), specifically from pages 63-64, this section delves into a variety of motivational strategies, enriched with my own examples and explanations to illustrate their practical application in educational settings. These strategies, which range from tangible rewards to fostering a competitive yet collaborative classroom atmosphere, are pivotal in enhancing student engagement and motivation, offering a dynamic and effective approach to teaching and learning.

1. Pair Work

- Explanation : Pair work involves two students collaborating on a task. This approach is beneficial as it allows for peer-to-peer interaction, sharing of ideas, and mutual support.

- Example : In a language class, students might work in pairs to practice a new set of vocabulary words. Each student takes turns using a word in a sentence, while the other offers feedback or suggests improvements.

2. Group Work

- Explanation : Group work requires students to collaborate in small teams. This fosters a sense of community, encourages diverse perspectives, and develops teamwork skills.

- Example : In a science class, students could work in groups to conduct an experiment. Each member could have a specific role (like note-taker, experimenter, or analyst) to contribute to the group’s overall success.

3. Play Games in Class

- Explanation : Incorporating games into learning can make the process more enjoyable and engaging. Games stimulate competition and cooperation, making learning more dynamic.

- Example : A math teacher might use a game like ‘Bingo’ to reinforce multiplication skills. Each correct answer allows a student to mark a spot on their Bingo card.

4. Students Self-Evaluate

- Explanation : Self-evaluation empowers students to assess their own learning. This encourages reflection, self-awareness, and responsibility for their learning process.

- Example : After completing a writing assignment, students could use a checklist to evaluate their work for elements like grammar, structure, and content clarity.

5. Students Co-Evaluate

- Explanation : Co-evaluation, or peer review, involves students evaluating each other’s work. This method provides different perspectives and can foster a collaborative learning environment.

- Example : In a history class, students might peer-review each other’s essays, offering constructive feedback on arguments, evidence used, and clarity of writing.

6. Scaffolding

- Explanation : Scaffolding is a teaching method that involves providing students with temporary support until they can perform tasks independently. This approach is tailored to the student’s current level of understanding.

- Example : In learning a complex concept like fractions, a teacher might start with concrete examples using physical objects, gradually moving to more abstract representations as students’ understanding deepens.

7. Arousing Curiosity or Attention

- Explanation : This strategy involves sparking students’ interest at the beginning of an activity. By arousing curiosity, you engage students and make the learning process more intriguing.

- Example : In a geography lesson, the teacher might start by showing a mysterious image of a place and asking students to guess where it could be, hinting at the unique characteristics of that location.

8. Establishing Relevance

- Explanation : Making a direct connection between what’s being learned and the students’ everyday lives helps them understand the practical application of knowledge.

- Example : In a mathematics class, a teacher could explain how algebra is used in calculating discounts during shopping, thus linking the lesson to a common real-life scenario.

9. Signposting

- Explanation : Clearly stating lesson objectives or summarizing progress helps students understand the purpose of the lesson and how it fits into the larger curriculum.

- Example : At the start of a history lesson, the teacher might say, “Today, we’re going to learn about the causes of World War I, which will help us understand current global political dynamics.”

10. Social Chat

- Explanation : Engaging in informal conversation on topics unrelated to the lesson can build rapport, make the classroom environment more relaxed and approachable.

- Example : A teacher might start a class with a brief chat about a popular sporting event or a new movie, creating a friendly atmosphere.

11. Promoting Autonomy

- Explanation : Allowing students to make choices and take part in decision-making fosters independence and makes learning more personally engaging.

- Example : In a language arts class, students could be given the choice to select a book for a book report. Alternatively, they might decide how to present their project, whether through a traditional report, a creative video, or a class presentation.

12. Tangible Reward

- Explanation : Offering physical rewards for participation or successful completion of an activity can serve as a direct motivator, especially for younger students.

- Example : A teacher might give stickers or small treats to students who complete their math homework on time.

13. Personalization

- Explanation : Allowing students to incorporate their personal experiences, feelings, or opinions into their work makes learning more relevant and engaging for them.

- Example : In an English class, students could write essays based on their own life experiences or opinions on a topic, thus making the assignment more personally meaningful.

14. Tangible Task Product

- Explanation : Having students create a physical product as a part of their learning process can enhance engagement and provide a sense of accomplishment.

- Example : In a science class, students could create a model of a solar system, or in art, they might design a brochure for an exhibition.

15. Individual Competition

- Explanation : Activities that include elements of individual competition can motivate students to perform better by tapping into their competitive spirit.

- Example : A math quiz where students compete to solve problems the fastest can encourage individual effort and focus.

16. Team Competition

- Explanation : Involving an element of team competition can build teamwork and collaborative skills, while still leveraging the motivational benefits of competition.

- Example : A history trivia game where students work in teams to answer questions can foster both cooperation and a competitive drive.

17. Effective Praise

- Explanation : Giving praise that is sincere, specific, and commensurate with the student’s achievement can boost confidence and reinforce positive behavior.

- Example : Instead of just saying “Good job!”, a teacher might say, “I’m impressed with how you used evidence to support your argument in that essay.”

18. Class Applause

- Explanation : Celebrating a student’s or a group’s effort or success through applause can create a positive and supportive classroom environment.

- Example : After a student presents a well-researched project, the teacher could lead the class in applauding their effort and achievement.

Classroom motivation strategies poster is available for free download in PDF formats. Subscribe to download it .

Final thoughts

I know it is hard to cover all the aspects of as big a topic as motivation but I hope the insights I shared so far would serve as a springboard to further explore the dynamics of motivation.

- Bernaus, M., & Gardner, R. C. (2008). Teacher Motivation Strategies, Student Perceptions, Student Motivation, and English Achievement. The Modern Language Journal, 92(3), 387–401. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25173065

- Guilloteaux, M. J., & Dörnyei, Z. (2008). Motivating Language Learners: A Classroom-Oriented Investigation of the Effects of Motivational Strategies on Student Motivation. TESOL Quarterly, 42(1), 55–77. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40264425

- WIESMAN, J. (2012). Student Motivation and the Alignment of Teacher Beliefs. The Clearing House, 85(3), 102–108. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23212853

Join our mailing list

Never miss an EdTech beat! Subscribe now for exclusive insights and resources .

Meet Med Kharbach, PhD

Dr. Med Kharbach is an influential voice in the global educational technology landscape, with an extensive background in educational studies and a decade-long experience as a K-12 teacher. Holding a Ph.D. from Mount Saint Vincent University in Halifax, Canada, he brings a unique perspective to the educational world by integrating his profound academic knowledge with his hands-on teaching experience. Dr. Kharbach's academic pursuits encompass curriculum studies, discourse analysis, language learning/teaching, language and identity, emerging literacies, educational technology, and research methodologies. His work has been presented at numerous national and international conferences and published in various esteemed academic journals.

Join our email list for exclusive EdTech content.

How to Motivate Students: 13 Classroom Tips & Examples

In the bustling world of education, one question that perennially echoes through the hallways is, “How can we motivate students effectively?” As educators, understanding the intricate dynamics of motivation is pivotal in creating an enriching learning environment.

In this article, we’ll explore 12 classroom tips and examples to ignite and sustain the flame of motivation among students.

Importance of Student Motivation

Student motivation is the heartbeat of any thriving classroom. When students are motivated, they are more engaged, enthusiastic, and open to learning.

Motivation serves as the catalyst for academic success and personal growth, shaping individuals into lifelong learners.

The Role of Teachers in Fostering Motivation

Teachers play a pivotal role in sculpting the motivational landscape of their classrooms.

By employing effective strategies and creating a positive atmosphere, educators can inspire and empower students to reach new heights.

1. Understanding Motivation

Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Motivation

Motivation comes in two main flavors: intrinsic and extrinsic.

Intrinsic motivation stems from internal desires and a genuine love for learning, while extrinsic motivation involves external rewards.

Balancing these two elements is crucial for a holistic approach to student motivation.

The Psychology of Motivation

Delving into the psychology of motivation unveils a world of cognitive and emotional triggers. Understanding how students perceive challenges and achievements is key to tailoring motivational strategies that resonate with them.

2. Creating a Positive Learning Environment

Importance of a Supportive Atmosphere

A positive and supportive atmosphere is the breeding ground for motivation. Students thrive in environments where they feel safe, acknowledged, and encouraged.

Fostering such an atmosphere lays the foundation for a motivated and engaged classroom.

Personalized Learning Experiences

Recognizing that every student is unique is the first step toward personalized learning experiences. Tailoring lessons to individual interests and learning styles not only sparks motivation but also enhances comprehension and retention.

One way to achieve this is through an assignment writing service that can provide tailored assignments based on your interests and learning style.

3. Setting Clear Goals

SMART Goal-Setting for Students

Setting Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound (SMART) goals provides students with clear objectives. This goal-setting framework empowers them to track progress and celebrate achievements, fueling their motivation.

Tracking Progress and Achievements

Regularly tracking and acknowledging progress is a powerful motivator. Whether through charts, badges, or verbal praise, recognizing achievements, no matter how small, creates a positive feedback loop.

4. Encouraging Student Engagement

Interactive Teaching Methods

Engagement is the key to sustained motivation. Incorporating interactive teaching methods, such as group discussions, hands-on activities, and multimedia presentations, captivates students’ attention and makes learning enjoyable.

Incorporating Real-World Examples

Connecting lessons to real-world examples bridges the gap between theory and practice.

By illustrating the practical applications of knowledge, teachers can instill a sense of purpose, making the learning experience more meaningful and motivating.

5. Recognizing and Rewarding Efforts

The Power of Positive Reinforcement

Positive reinforcement is a cornerstone of motivation. Whether through verbal praise, tangible rewards, or a simple acknowledgment of effort, reinforcing positive behavior encourages students to continue putting in their best.

Creative Reward Systems

Injecting creativity into reward systems adds an element of excitement. From “Student of the Week” awards to themed achievement badges, these creative incentives make the journey towards goals more enjoyable.

6. Fostering a Growth Mindset

Embracing Challenges as Opportunities

Fostering a growth mindset involves cultivating a mindset that views challenges as opportunities for growth. Encouraging students to embrace difficulties as stepping stones to success cultivates resilience and a hunger for knowledge.

Encouraging Resilience in the Face of Setbacks

Setbacks are inevitable, but how students respond to them is crucial. Teaching resilience and perseverance empowers students to overcome obstacles, reinforcing their belief in their ability to succeed.

7. Utilizing Technology Effectively

Integrating Technology in the Classroom

Incorporating technology into lessons caters to the digital-native generation. Interactive apps, educational games, and multimedia presentations not only enhance learning but also add a modern flair that captures students’ interest.

Gamification for Enhanced Engagement

Gamifying the learning experience transforms the classroom into an interactive playground. Incorporating elements like point systems, challenges, and leaderboards taps into the competitive spirit, making learning an exciting adventure.

8. Promoting Collaborative Learning

Benefits of Group Activities

Collaborative learning encourages teamwork and communication skills. Group activities not only break the monotony of traditional teaching but also provide students with a support system, fostering motivation through shared achievements.

Peer-to-Peer Support and Motivation

Peer support is a powerful motivator. Creating an environment where students cheer for each other’s successes and provide assistance during challenges nurtures a sense of community, making the classroom a place where everyone thrives.

9. Tailoring Teaching Styles

Recognizing Diverse Learning Preferences

Students have diverse learning preferences. Some are visual learners, while others excel with hands-on experiences.

Recognizing and accommodating these differences ensures that every student feels seen and understood, enhancing their motivation to learn.

Adapting Teaching Methods Accordingly

Flexibility in teaching methods is a key element in keeping students engaged. Experimenting with different approaches allows educators to find what resonates best with their students, making the learning journey more dynamic and exciting.

10. Celebrating Diversity

Inclusive Teaching Practices

Inclusive teaching practices acknowledge and celebrate diversity. By incorporating diverse perspectives and cultural references in lessons, educators create an inclusive environment where every student feels valued and motivated to participate.

Appreciating Cultural Differences

Cultural differences bring richness to the classroom. Acknowledging and appreciating these differences not only broadens students’ horizons but also fosters a sense of pride in their unique backgrounds, contributing to heightened motivation.

11. Effective Communication

Providing Constructive Feedback

Constructive feedback is a cornerstone of improvement. Timely and specific feedback guides students toward improvement, instilling confidence and motivation to continuously strive for excellence.

12. Instilling a Sense of Purpose

Linking lessons to real-world applications answers the perennial student question, “Why do I need to know this?”

Understanding the practical relevance of knowledge instills a sense of purpose, motivating students to delve deeper into their studies.

Passion is the driving force behind sustained motivation. By sharing their own enthusiasm for the subject matter, teachers can ignite a spark in students, inspiring them to pursue knowledge not just for grades but for the sheer joy of learning.

13. Balancing Structure and Flexibility

The Importance of Routine

Structure provides a sense of security and predictability. Implementing routines in the classroom establishes a conducive learning environment, allowing students to focus on learning without unnecessary distractions.

Allowing for Flexibility in Learning

While structure is essential, flexibility is equally vital. Allowing for flexibility in learning caters to the diverse needs and interests of students, keeping the educational journey dynamic and adapting to the ever-evolving landscape of knowledge.

In the intricate dance of education, motivation takes center stage. By embracing a multifaceted approach that combines positive environments, personalized learning, goal-setting, and effective communication, educators can create classrooms where motivation thrives.

The journey toward motivating students is ongoing, requiring dedication, creativity, and a genuine passion for teaching.

About the Author Pearl Holland is an experienced Academic writer having 7 years of experience at Perfect Essay Writing with a passion for crafting compelling and insightful content.

Our Guide for Increasing Focus and Concentration

Center for Teaching

Motivating students.

Introduction

- Expectancy – Value – Cost Model

ARCS Model of Instructional Design

Self-determination theory, additional strategies for motivating students.

Fostering student motivation is a difficult but necessary aspect of teaching that instructors must consider. Many may have led classes where students are engaged, motivated, and excited to learn, but have also led classes where students are distracted, disinterested, and reluctant to engage—and, probably, have led classes that are a mix. What factors influence students’ motivation? How can instructors promote students’ engagement and motivation to learn? While there are nuances that change from student to student, there are also models of motivation that serve as tools for thinking through and enhancing motivation in our classrooms. This guide will look at three frameworks: the expectancy-value-cost model of motivation, the ARCS model of instructional design, and self-determination theory. These three models highlight some of the major factors that influence student motivation, often drawing from and demonstrating overlap among their frameworks. The aim of this guide is to explore some of the literature on motivation and offer practical solutions for understanding and enhancing student motivation.

Expectancy – Value – Cost Model

The purpose of the original expectancy-value model was to predict students’ achievement behaviors within an educational context. The model has since been refined to include cost as one of the three major factors that influence student motivation. Below is a description of the three factors, according to the model, that influence motivation.

- Expectancy refers to a student’s expectation that they can actually succeed in the assigned task. It energizes students because they feel empowered to meet the learning objectives of the course.

- Value involves a student’s ability to perceive the importance of engaging in a particular task. This gives meaning to the assignment or activity because students are clear on why the task or behavior is valuable.

- Cost points to the barriers that impede a student’s ability to be successful on an assignment, activity and/or the course at large. Therefore, students might have success expectancies and perceive high task value, however, they might also be aware of obstacles to their engagement or a potential negative affect resulting in performance of the task, which could decrease their motivation.

Three important questions to consider from the student perspective:

1. Expectancy – Can I do the task?

2. Value – Do I want to do the task?

• Intrinsic or interest value : the inherent enjoyment that an individual experiences from engaging in the task for its own sake.

• Utility value : the usefulness of the task in helping achieve other short term or long-term goals.

• Attainment value : the task affirms a valued aspect of an individual’s identity and meets a need that is important to the individual.

3. Cost – Am I free of barriers that prevent me from investing my time, energy, and resources into the activity?

It’s important to note that expectancy, value and cost are not shaped only when a student enters your classroom. These have been shaped over time by both individual and contextual factors. Each of your students comes in with an initial response, however there are strategies for encouraging student success, clarifying subject meaning and finding ways to mitigate costs that will increase your students’ motivation. Everyone may not end up at the same level of motivation, but if you can increase each student’s motivation, it will help the overall atmosphere and productivity of the course that you are teaching.

Strategies to Enhance Expectancy, Value, and Cost

Hulleman et. al (2016) summarize research-based sources that positively impact students’ expectancy beliefs, perceptions of task value, and perceptions of cost, which might point to useful strategies that instructors can employ.

Research-based sources of expectancy-related beliefs

Research-based sources of value, research-based sources of cost.

- Barron K. E., & Hulleman, C. S. (2015). Expectancy-value-cost model of motivation. International Encyclopedia of Social and Behavioral Sciences, 8 , 503-509.

- Hulleman, C. S., Barron, K. E., Kosovich, J. J., & Lazowski, R. A. (2016). Student motivation: Current theories, constructs, and interventions within an expectancy-value framework. In A. A. Lipnevich et al. (Eds.), Psychosocial Skills and School Systems in the 21st Century . Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

The ARCS model of instructional design was created to improve the motivational appeal of instructional materials. The ARCS model is grounded in an expectancy-value framework, which assumes that people are motivated to engage in an activity if it’s perceived to be linked to the satisfaction of personal needs and if there is a positive expectancy for success. The purpose of this model was to fill a gap in the motivation literature by providing a model that could more clearly allow instructors to identify strategies to help improve motivation levels within their students.

ARCS is an acronym that stands for four factors, according to the model, that influence student motivation: attention, relevance, confidence, and satisfaction.

- Attention refers to getting and sustaining student attention and directing attention to the appropriate stimuli.

- Relevance involves making instruction applicable to present and future career opportunities, showing that learning in it of itself is enjoyable, and/or focusing on process over product by satisfying students’ psychological needs (e.g., need for achievement, need for affiliation).

- Confidence includes helping students believe that some level of success is possible if effort is exerted.

- Satisfaction is attained by helping students feel good about their accomplishments and allowing them to exert some degree of control over the learning experience.

To use the ARCS instructional design model, these steps can be followed:

- Classify the problem

- Analyze audience motivation

- Prepare motivational objectives (i.e., identify which factor in the ARCS model to target based on the defined problem and audience analysis).

- Generate potential motivational strategies for each objective

- Select strategies that a) don’t take up too much instructional time; b) don’t detract from instructional objectives; c) fall within time and money constraints; d) are acceptable to the audience; and e) are compatible with the instructor’s personal style, preferences, and mode of instruction.

- Prepare motivational elements

- Integrate materials with instruction

- Conduct a developmental try-out

- Assess motivational outcomes

Strategies to Enhance Attention, Relevance, Confidence, and Satisfaction

Keller (1987) provides several suggestions for how instructors can positively impact students’ attention, perceived relevance, confidence, and satisfaction.

Attention Strategies

Incongruity, Conflict

- Introduce a fact that seems to contradict the learner’s past experience.

- Present an example that does not seem to exemplify a given concept.

- Introduce two equally plausible facts or principles, only one of which can be true.

- Play devil’s advocate.

Concreteness

- Show visual representations of any important object or set of ideas or relationships.

- Give examples of every instructionally important concept or principle.

- Use content-related anecdotes, case studies, biographies, etc.

Variability

- In stand up delivery, vary the tone of your voice, and use body movement, pauses, and props.

- Vary the format of instruction (information presentation, practice, testing, etc.) according to the attention span of the audience.

- Vary the medium of instruction (platform delivery, film, video, print, etc.).

- Break up print materials by use of white space, visuals, tables, different typefaces, etc.

- Change the style of presentation (humorous-serious, fast-slow, loud-soft, active-passive, etc.).

- Shift between student-instructor interaction and student-student interaction.

- Where appropriate, use plays on words during redundant information presentation.

- Use humorous introductions.

- Use humorous analogies to explain and summarize.

- Use creativity techniques to have learners create unusual analogies and associations to the content.

- Build in problem solving activities at regular interval.

- Give learners the opportunity to select topics, projects and assignments that appeal to their curiosity and need to explore.

Participation

- Use games, role plays, or simulations that require learner participation.

Relevance Strategies

- State explicitly how the instruction builds on the learner’s existing skills.

- Use analogies familiar to the learner from past experience.

- Find out what the learners’ interests are and relate them to the instruction.

Present Worth

- State explicitly the present intrinsic value of learning the content, as distinct from its value as a link to future goals.

Future Usefulness

- State explicitly how the instruction relates to future activities of the learner.

- Ask learners to relate the instruction to their own future goals (future wheel).

Need Matching

- To enhance achievement striving behavior, provide opportunities to achieve standards of excellence under conditions of moderate risk.

- To make instruction responsive to the power motive, provide opportunities for responsibility, authority, and interpersonal influence.

- To satisfy the need for affiliation, establish trust and provide opportunities for no-risk, cooperative interaction.

- Bring in alumni of the course as enthusiastic guest lecturers.

- In a self-paced course, use those who finish first as deputy tutors.

- Model enthusiasm for the subject taught.

- Provide meaningful alternative methods for accomplishing a goal.

- Provide personal choices for organizing one’s work.

Confidence Strategies

Learning Requirements

- Incorporate clearly stated, appealing learning goals into instructional materials.

- Provide self-evaluation tools which are based on clearly stated goals.

- Explain the criteria for evaluation of performance.

- Organize materials on an increasing level of difficulty; that is, structure the learning material to provide a “conquerable” challenge.

Expectations

- Include statements about the likelihood of success with given amounts of effort and ability.

- Teach students how to develop a plan of work that will result in goal accomplishment.

- Help students set realistic goals.

Attributions

- Attribute student success to effort rather than luck or ease of task when appropriate (i.e., when you know it’s true!).

- Encourage student efforts to verbalize appropriate attributions for both successes and failures.

Self-Confidence

- Allow students opportunity to become increasingly independent in learning and practicing a skill.

- Have students learn new skills under low risk conditions, but practice performance of well-learned tasks under realistic conditions.

- Help students understand that the pursuit of excellence does not mean that anything short of perfection is failure; learn to feel good about genuine accomplishment.

Satisfaction Strategies

Natural Consequences

- Allow a student to use a newly acquired skill in a realistic setting as soon as possible.

- Verbally reinforce a student’s intrinsic pride in accomplishing a difficult task.

- Allow a student who masters a task to help others who have not yet done so.

Unexpected Rewards

- Reward intrinsically interesting task performance with unexpected, non-contingent rewards.

- Reward boring tasks with extrinsic, anticipated rewards.

Positive Outcomes

- Give verbal praise for successful progress or accomplishment.

- Give personal attention to students.

- Provide informative, helpful feedback when it is immediately useful.

- Provide motivating feedback (praise) immediately following task performance.

Negative Influences

- Avoid the use of threats as a means of obtaining task performance.

- Avoid surveillance (as opposed to positive attention).

- Avoid external performance evaluations whenever it is possible to help the student evaluate his or her own work.

- Provide frequent reinforcements when a student is learning a new task.

- Provide intermittent reinforcement as a student becomes more competent at a task.

- Vary the schedule of reinforcements in terms of both interval and quantity.

Source: Keller, J. M. (1987). Development and use of the ARCS model of instructional design. Journal of Instructional Development, 10 , 2-10.

Self-determination theory (SDT) is a macro-theory of human motivation, emotion, and development that is concerned with the social conditions that facilitate or hinder human flourishing. While applicable to many domains, the theory has been commonly used to understand what moves students to act and persist in educational settings. SDT focuses on the factors that influence intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, which primarily involves the satisfaction of basic psychological needs.

Basic Psychological Needs

SDT posits that human motivation is guided by the need to fulfill basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

- Autonomy refers to having a choice in one’s own individual behaviors and feeling that those behaviors stem from individual volition rather than from external pressure or control. In educational contexts, students feel autonomous when they are given options, within a structure, about how to perform or present their work.

- Competence refers to perceiving one’s own behaviors or actions as effective and efficient. Students feel competent when they are able to track their progress in developing skills or an understanding of course material. This is often fostered when students receive clear feedback regarding their progression in the class.

- Relatedness refers to feeling a sense of belonging, closeness, and support from others. In educational settings, relatedness is fostered when students feel connected, both intellectually and emotionally, to their peers and instructors in the class. This can often be accomplished through interactions that allow members of the class to get to know each other on a deeper, more personal level.

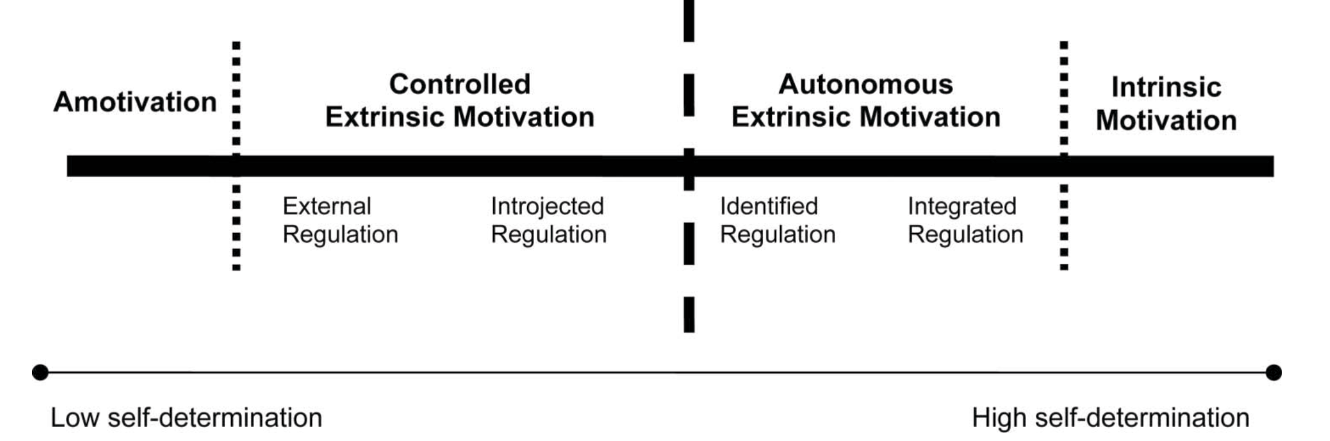

Continuum of Self-Determination

SDT also posits that motivation exists on a continuum. When an environment provides enough support for the satisfaction of the psychological needs of autonomy, competence and relatedness, an individual may experience self-determined forms of motivation: intrinsic motivation, integration, and identification. Self-determined motivation occurs when there is an internal perceived locus of causality (i.e., internal factors are the main driving force for the behavior). Integration and identification are also grouped as autonomous extrinsic motivation as the behavior is driven by internal and volitional choice.

Intrinsic motivation , which is the most self-determined type of motivation, occurs when individuals naturally and spontaneously perform behaviors as a result of genuine interest and enjoyment.

Integrated regulation is when individuals identify the importance of a behavior, integrate this behavior into their self-concept, and pursue activities that align with this self-concept.

Identified regulation is where people identify and recognize the value of a behavior, which then drives their action.

When an environment does not provide enough support for the satisfaction of autonomy, competence, and relatedness, an individual may experience non-self-determined forms of motivation: introjection and external regulation. Introjection and external regulation are grouped as controlled extrinsic motivation because people enact these behaviors due to external or internal pressures.

Introjected regulation occurs when individuals are controlled by internalized consequences administered by the individual themselves, such as pride, shame, or guilt.

External regulation is when people’s behaviors are controlled exclusively by external factors, such as rewards or punishments.

Finally, at the bottom of the continuum is amotivation, which is lowest form of motivation.

Amotivation exists when there is a complete lack of intention to behave and there is no sense of achievement or purpose when the behavior is performed.

Below is a figure depicting the continuum of self-determination taken from Lonsdale, Hodge, and Rose (2009).

Although having intrinsically motivated students would be the ultimate goal, it may not be a practical one within educational settings. That’s because there are several tasks that are required of students to meet particular learning objectives that may not be inherently interesting or enjoyable. Instead, instructors can employ various strategies to satisfy students’ basic psychological needs, which should move their level of motivation along the continuum, and hopefully lead to more self-determined forms of motivation, thus yielding the greatest rewards in terms of student academic outcomes.

Below are suggestions for how instructors can positively impact students’ perceived autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

Strategies to Enhance Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness

Autonomy strategies.

- Have students choose paper topics

- Have students choose the medium with which they will present their work

- Co-create rubrics with students (e.g., participation rubrics, assignment rubrics)

- Have students choose the topics you will cover in a particular unit

- Drop the lowest assessment or two (e.g., quizzes, exams, homework)

- Have students identify preferred assignment deadlines

- Gather mid-semester feedback and make changes based on student suggestions

- Provide meaningful rationales for learning activities

- Acknowledge students’ feelings about the learning process or learning activities throughout the course

Competence Strategies

- Set high but achievable learning objectives

- Communicate to students that you believe they can meet your high expectations

- Communicate clear expectations for each assignment (e.g., use rubrics)

- Include multiple low-stakes assessments

- Give students practice with feedback before assessments

- Provide lots of early feedback to students

- Have students provide peer feedback

- Scaffold assignments

- Praise student effort and hard work

- Provide a safe environment for students to fail and then learn from their mistakes

Relatedness Strategies

- Share personal anecdotes

- Get to know students via small talk before/after class and during breaks

- Require students to come to office hours (individually or in small groups)

- Have students complete a survey where they share information about themselves

- Use students’ names (perhaps with the help of name tents)

- Have students incorporate personal interests into their assignments

- Share a meal with students or bring food to class

- Incorporate group activities during class, and allow students to work with a variety of peers

- Arrange formal study groups

- Convey warmth, caring, and respect to students

- Lonsdale, C., Hodge, K., & Rose, E. (2009). Athlete burnout in elite sport: A self-determination perspective. Journal of Sports Sciences, 27, 785-795.

- Niemiec, C. P., & Ryan, R. M. (2009). Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom: Applying self-determination theory to educational practice. Theory and Research in Education, 7, 133-144.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness . New York: Guilford.

Below are some additional research-based strategies for motivating students to learn.

- Become a role model for student interest . Deliver your presentations with energy and enthusiasm. As a display of your motivation, your passion motivates your students. Make the course personal, showing why you are interested in the material.

- Get to know your students. You will be able to better tailor your instruction to the students’ concerns and backgrounds, and your personal interest in them will inspire their personal loyalty to you. Display a strong interest in students’ learning and a faith in their abilities.

- Use examples freely. Many students want to be shown why a concept or technique is useful before they want to study it further. Inform students about how your course prepares students for future opportunities.

- Teach by discovery. Students find it satisfying to reason through a problem and discover the underlying principle on their own.

- Cooperative learning activities are particularly effective as they also provide positive social pressure.

- Set realistic performance goals and help students achieve them by encouraging them to set their own reasonable goals. Design assignments that are appropriately challenging in view of the experience and aptitude of the class.

- Place appropriate emphasis on testing and grading. Tests should be a means of showing what students have mastered, not what they have not. Avoid grading on the curve and give everyone the opportunity to achieve the highest standard and grades.

- Be free with praise and constructive in criticism. Negative comments should pertain to particular performances, not the performer. Offer nonjudgmental feedback on students’ work, stress opportunities to improve, look for ways to stimulate advancement, and avoid dividing students into sheep and goats.

- Give students as much control over their own education as possible. Let students choose paper and project topics that interest them. Assess them in a variety of ways (tests, papers, projects, presentations, etc.) to give students more control over how they show their understanding to you. Give students options for how these assignments are weighted.

- Bain, K. (2004). What the best college teachers do. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- DeLong, M., & Winter, D. (2002). Learning to teach and teaching to learn mathematics: Resources for professional development . Washington, D.C.: Mathematical Association of America.

- Nilson, L. (2016). Teaching at its best: A research-based resource for college instructors (4 th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Josey-Bass.

Teaching Guides

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

- TEFL Internship

- TEFL Masters

- Find a TEFL Course

- Special Offers

- Course Providers

- Teach English Abroad

- Find a TEFL Job

- About DoTEFL

- Our Mission

- How DoTEFL Works

Forgotten Password

- How to Motivate Students Effectively: 21 Tips & Techniques

- Teach English

- James Prior

- No Comments

- Updated September 30, 2024

Discover effective strategies on how to motivate students with practical tips and techniques. Learn how to build confidence, get results, and inspire a love for learning in every student.

Motivating students can be a challenge, but it is essential for their success. When students are motivated, they engage more deeply, learn more effectively, and perform better.

As an educator, your role in fostering motivation is critical. This guide provides practical tips and techniques to keep students motivated and enthusiastic about learning.

However, before we get into some actionable tips, it’s important to understand what drives student motivation.

Table of Contents

What Drives Student Motivation?

Motivation is driven by a complex interplay of factors that include individual psychological needs, environmental influences, and social contexts. Research in psychology and education highlights several key drivers of motivation that impact students’ engagement and learning:

1. Self-Determination Theory (SDT)

Developed by Deci and Ryan, Self-Determination Theory is one of the most widely recognized theories of motivation. It emphasizes three basic psychological needs that drive motivation:

- Autonomy: The need to feel in control of one’s actions and decisions. Students are more motivated when they feel they have a choice in their learning.

- Competence: The need to feel capable and effective in one’s tasks. Students are driven by the desire to master skills and see their progress.

- Relatedness: The need to feel connected to others. Positive relationships with teachers and peers foster a sense of belonging and motivate students to participate.

SDT posits that when these needs are satisfied, motivation is more intrinsic, leading to higher engagement, persistence, and overall well-being of those involved.

2. Expectancy-Value Theory

Developed by Eccles and Wigfield, Expectancy-Value Theory suggests that motivation is influenced by two main factors:

- Expectancy: This refers to a student’s belief in their ability to succeed in a task. When students believe they can succeed, they are more motivated to engage and put in effort.

- Value: This refers to how much a student values the task, including interest, usefulness, and relevance. Students are more motivated when they see the task as important, interesting, or useful for their future.

This theory highlights the importance of helping students build confidence in their abilities and demonstrating the value of what they are learning.

3. Growth Mindset

Research by Carol Dweck on growth mindset shows that students’ beliefs about intelligence and ability significantly impact motivation. A growth mindset — the belief that abilities can be developed through effort and learning — encourages students to embrace challenges, persist through difficulties, and view failure as an opportunity to grow.

Conversely, a fixed mindset, where students believe their abilities are static, often leads to avoidance of challenges and a fear of failure. Promoting a growth mindset can drive intrinsic motivation and resilience in students.

4. Goal Orientation Theory

Goal Orientation Theory differentiates between mastery goals and performance goals:

- Mastery Goals: Focus on learning, understanding, and personal improvement. Students with mastery goals are motivated by the desire to gain new skills and knowledge.

- Performance Goals: Focus on demonstrating ability relative to others. These can be divided into performance-approach goals (aiming to outperform others) and performance-avoidance goals (aiming to avoid doing worse than others).

Research shows that mastery goals are more effective in fostering long-term motivation, as they encourage deep engagement and a positive attitude toward learning challenges.

5. Social and Environmental Influences

Motivation is also influenced by the classroom environment, teaching style, and social interactions. Studies highlight the importance of:

- Teacher-Student Relationships: Positive and supportive relationships with teachers are linked to higher student motivation. Teachers who show empathy, respect, and interest in their students help foster a more motivating environment.

- Peer Influence: Peer interactions can either positively or negatively impact motivation. Collaborative learning and peer encouragement can boost motivation, while negative peer pressure can have the opposite effect.

- Classroom Climate: A safe, engaging, and inclusive classroom climate that values effort, allows for mistakes, and supports growth fosters a more motivating environment.

This leads us nicely to how you can motivate your students.

How to Motivate Your Students

In this section, we explore 21 practical tips on how to motivate your students . From building strong relationships and setting clear goals to incorporating movement and creating a positive learning environment, these techniques will help you inspire your students to stay focused, enthusiastic, and driven to succeed.

1. Understand What Drives Your Students

Before you can motivate students, you need to understand what drives them. Every student is different, with unique needs, interests, and learning styles. Spend time getting to know your students individually. Ask them about their interests, hobbies, and goals. Knowing what excites them can help you tailor your approach to motivate them better.

- Intrinsic Motivation vs. Extrinsic Motivation: Some students are motivated by internal factors like curiosity or a desire to learn (intrinsic motivation). Others respond to external rewards like grades, praise, or competition (extrinsic motivation). Recognize which type of motivation drives each student and use it to your advantage.

- Learning Styles Matter: Students learn in different ways—some are visual learners, while others prefer hands-on activities. Adapt your teaching style to include a mix of methods that cater to various learning styles.

2. Set Clear, Achievable Goals

Setting clear and achievable goals is a powerful motivator. Students need to understand what they are working towards and why it matters.

- Define Specific Objectives: Break down large tasks into smaller, manageable objectives. For example, instead of asking students to “do well in math,” set specific goals like “master multiplication tables by next Friday.”

- Use SMART Goals: SMART goals are Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound. For instance, instead of a vague goal like “improve reading skills,” set a SMART goal: “Read one chapter of a book each week and summarize it.”

- Celebrate Small Wins: Acknowledge achievements, no matter how small. Celebrating small wins keeps students motivated and builds their confidence.

3. Create a Positive and Supportive Learning Environment

A positive classroom environment plays a significant role in student motivation. Students are more likely to engage when they feel safe, respected, and valued.

- Build Strong Relationships: Take time to build strong, trusting relationships with your students. Show genuine interest in their well-being and academic success.

- Promote a Growth Mindset: Encourage students to view challenges as opportunities to learn rather than failures. Praise effort, not just results, and emphasize that intelligence and abilities can grow with hard work.

- Be Approachable and Fair: Students respond better when they feel their teacher is approachable and fair. Be consistent with rules and fair in how you treat students.

4. Make Learning Relevant and Fun

Students are more motivated when they see the relevance of what they are learning. Connect lessons to real-life situations, student interests, or future goals.

- Relate Lessons to Real Life: Show students how what they are learning applies to the real world. For example, when teaching math, use examples like budgeting or shopping to make it relevant.

- Incorporate Technology: Use technology like interactive apps, games, or videos to make learning engaging. Many students find technology-based learning more exciting than traditional methods.

- Gamify Learning: Incorporate game elements into your lessons, such as point systems, leaderboards, or challenges. Gamification in education makes learning fun and encourages healthy competition.

5. Provide Choice and Autonomy

Giving students some control over their learning can significantly boost their motivation. When students feel they have a say, they are more invested in the outcome.

- Offer Choices in Assignments: Allow students to choose how they demonstrate their learning. For example, they could write an essay , create a video, or present a project.

- Let Students Set Personal Goals: Encourage students to set their own learning goals. This fosters a sense of ownership and responsibility for their education.

- Use Self-Directed Learning: Allow students to explore topics of interest on their own. Provide guidelines but let them take the lead.

6. Use Praise and Positive Reinforcement

Positive reinforcement can encourage students to keep up the good work. Praise should be specific, sincere, and directed at effort rather than innate ability.

- Praise Effort, Not Just Results: Recognize students who put in effort, even if they don’t get perfect results. For instance, say, “I’m proud of how hard you worked on this.”

- Be Specific in Your Praise: Instead of vague praise like “Good job,” be specific: “You did a great job organizing your essay.”

- Reward Progress: Use rewards like stickers, extra recess, or classroom privileges to recognize progress. Make sure rewards are meaningful and appropriate for the age group.

7. Use Collaborative Learning and Group Work

Collaboration encourages students to engage with each other and the material. Group work builds communication skills and creates a sense of community.

- Group Projects: Assign group projects where students can work together towards a common goal. This not only builds teamwork skills but also makes learning more dynamic.

- Peer Teaching: Let students teach each other. When students explain concepts to their peers, they reinforce their own understanding.

- Encourage Discussion: Create opportunities for students to discuss what they are learning. Use small group discussions, peer reviews, or class debates.

8. Provide Constructive Feedback

Feedback is essential for learning and motivation. Effective feedback should be timely, specific, and focused on growth.

- Be Timely with Feedback: Provide feedback as soon as possible after an assignment. Immediate feedback helps students understand what they did well and what needs improvement.

- Focus on Specifics: Instead of general comments like “Try harder,” give detailed feedback: “Your essay is well-structured, but adding more examples could make your argument stronger.”

- Encourage Reflection: Encourage students to reflect on the feedback and think about how they can improve. This promotes a growth mindset.

9. Address Anxiety and Fear of Failure

Fear of failure can be a significant demotivator for students. Addressing these fears can help students feel more comfortable taking risks.

- Create a Safe Space for Mistakes: Let students know it’s okay to make mistakes. Use mistakes as learning opportunities rather than something to be punished.

- Teach Coping Skills: Teach students how to manage stress and anxiety. Techniques like deep breathing, positive self-talk, or time management can help.

- Reframe Failure: Help students reframe failure as a step towards success. Share stories of famous people who failed before succeeding to illustrate this point.

10. Personalize Learning Experiences

Personalizing learning can make students feel seen and understood. When lessons are tailored to individual needs, students are more likely to stay motivated.

- Differentiate Instruction: Use different teaching methods to cater to various learning styles. For example, visual aids, hands-on activities, and discussions can address diverse needs.

- Offer One-on-One Support: Provide individualized support for students who need extra help. This can be in the form of tutoring, additional resources, or just taking extra time to explain concepts.

- Set Individual Learning Plans: For students who need extra challenges or support, set individual learning plans that cater to their specific needs.

11. Foster a Sense of Belonging and Community

Students who feel they belong in the classroom are more motivated. Creating a sense of community can boost engagement and make students more enthusiastic about learning.

- Encourage Class Participation: Create a classroom environment where every student feels comfortable participating. Use icebreaker questions , icebreaker games , group discussions, and inclusive practices to involve everyone.

- Celebrate Diversity: Recognize and celebrate the diverse backgrounds of your students. Incorporate culturally relevant materials and discussions into your lessons.

- Build a Classroom Community: Use activities that build relationships among students, such as team-building exercises or class traditions.

12. Integrate Real-World Applications and Problem-Solving

Connecting learning to real-world scenarios can make lessons more engaging. Students are motivated when they see the practical application of what they learn.

- Use Problem-Based Learning (PBL): Present students with real-world problems to solve. This approach promotes critical thinking and shows the relevance of academic concepts.

- Invite Guest Speakers: Bring in guest speakers from various professions to talk about how they use what students are learning in real life.

- Incorporate Field Trips and Experiential Learning: Field trips and hands-on activities provide students with practical experiences that relate to their studies.

13. Encourage Self-Assessment and Reflection

When students assess their own work, they become more aware of their strengths and areas for improvement. Self-reflection promotes accountability and intrinsic motivation.

- Use Self-Assessment Tools: Provide students with rubrics or checklists to evaluate their own work. This encourages them to think critically about their performance.

- Encourage Journaling: Journals can be a great way for students to reflect on their learning experiences. They can write about what they learned, what they found challenging, and how they felt.

- Set Reflection Time: Allocate time for students to reflect on their progress regularly. This could be after an assignment, at the end of a unit, or even weekly.

14. Incorporate Movement and Physical Activity

Physical movement can boost energy levels and improve focus. Integrating movement into lessons can help keep students engaged.

- Brain Breaks: Use short brain breaks that involve movement, like stretching or quick physical exercises. This helps re-energize students and improve concentration.

- Kinesthetic Learning: Incorporate hands-on activities or movement-based learning. For example, students can act out a scene from history or use gestures to learn vocabulary.

- Outdoor Learning: When possible, take learning outside. Outdoor environments can be refreshing and provide a change of pace.

15. Adapt Your Teaching Style

Your teaching style significantly impacts student motivation. Be flexible, enthusiastic, and willing to try new approaches.

- Be Enthusiastic: Your passion for the subject can be contagious. Show excitement when teaching, and students are more likely to mirror your enthusiasm.

- Use Humor: A little humor can go a long way in creating a relaxed and enjoyable learning environment. Don’t be afraid to laugh with your students.

- Be Flexible: If a lesson isn’t working, be willing to change your approach. Adapt to the needs of your students rather than sticking rigidly to the plan.

16. Develop a Reward System

A well-thought-out reward system can boost student motivation. Rewards can be simple, like praise, or more tangible, like certificates or small prizes.

- Use a Points System: Assign points for good behavior, completing assignments, or participation. Points can be exchanged for rewards like extra break time or classroom privileges.

- Create a Classroom Store: Set up a classroom store where students can “buy” items with earned points. Items can be inexpensive but should be meaningful.

- Recognize Achievements Publicly: Public recognition, like a “Student of the Week” award, can motivate students to do their best.

17. Encourage Goal Setting and Self-Improvement

Help students set personal academic goals. This fosters a sense of direction and purpose.

- Guide Students in Setting Goals: Help students set realistic goals that challenge them. Provide guidance on how to break down larger goals into manageable steps.

- Track Progress: Use goal-tracking sheets or apps to help students monitor their progress. This visual representation can be motivating.

- Reflect on Goals Regularly: Encourage students to revisit their goals periodically. Discuss what is working, what isn’t, and how they can adjust.

18. Address Barriers to Learning

Identifying and addressing barriers to learning can help maintain student motivation. Barriers might include learning difficulties, language challenges, or personal issues.

- Identify Learning Difficulties Early: Look for signs that a student is struggling and address them early. This could involve extra support, accommodations, or referrals to specialists.

- Provide Extra Help: Offer additional resources, tutoring, or study sessions for students who need it. Be proactive in offering help before students fall behind.

- Communicate with Parents: Keep open communication with parents to understand what might be affecting a student’s motivation outside of school.

19. Emphasize the Value of Education

Help students understand the long-term benefits of education. Showing them the bigger picture can provide motivation beyond immediate rewards.

- Connect Learning to Future Goals: Talk about how skills learned today can benefit students in their future careers or personal lives.

- Discuss Success Stories: Share stories of individuals who succeeded through education. This can inspire students and give them role models to look up to.

- Incorporate Career Exploration: Integrate activities that allow students to explore different careers and how education plays a role in achieving those careers.

20. Be Patient and Persistent

Motivating students is not always easy, and progress can be slow. Stay patient, persistent, and consistent in your efforts.

- Keep Encouraging, Even When It’s Tough: Some students may take longer to respond to motivational techniques. Keep encouraging and never give up on them.

- Adapt and Learn: Be willing to adapt your strategies based on what works and what doesn’t. Learn from each experience and refine your approach.

- Celebrate Progress: Remember to celebrate both big and small achievements along the way. Every step forward is a win.

21. Inspire Them

As an educator, your attitude toward learning can significantly influence your students. When you model passion, curiosity, and a love for learning, students are more likely to adopt these attitudes themselves.

- Share Your Learning Experiences: Talk about things you are learning, whether related to the subject or something entirely different. This shows students that learning doesn’t stop after school.

- Be Curious and Ask Questions: Show enthusiasm for discovering new information and exploring topics in-depth. When students see you asking questions and seeking answers, they’ll be more inclined to do the same.

- Stay Updated and Innovative: Continuously update your teaching methods and bring new ideas into the classroom. Your willingness to learn and adapt will inspire students to keep an open mind and embrace change.

Modeling a positive attitude toward learning helps students see it as a lifelong journey rather than just a task to complete in school. This perspective can deeply motivate them to stay engaged and curious both inside and outside the classroom.

Ready to Motivate Your Students?

Motivating students requires effort, creativity, and a deep understanding of what drives them. By using these tips and techniques, you can create an engaging learning environment that fosters enthusiasm, resilience, and a lifelong love of learning.

Remember, your role as an educator is not just to teach but to inspire. With the right approach, you can motivate every student to reach their full potential.

- Recent Posts

- 27 Christmas Idioms With Their Meanings & Examples - November 4, 2024

- 25 Fun Christmas Classroom Activities for Your Class - November 4, 2024

- Bear With Me or Bare With Me: Which is Correct? - November 1, 2024

More from DoTEFL

5 Most Common Expat Challenges and How to Overcome Them

- Updated October 7, 2024

259+ Icebreaker Questions for Every Occasion

- Updated September 5, 2024

Countries & Nationalities List With Their Adjective & Noun Forms

- Updated July 31, 2023

Gamification in Education: Transforming Learning through Play

- Updated September 3, 2024

49 Best Apps for Teachers (2024)

- Updated August 20, 2024

Cultural Immersion in Language Learning: Why It’s Important

- The global TEFL course directory.

A Strategy for Boosting Student Motivation

A teacher shares the strategy she developed to increase elementary students’ willingness to engage in productive struggle and meet their learning goals.

Your content has been saved!

How to motivate students is an issue that teachers have always had to grapple with. Now, with the constant stimuli of internet-connected devices, it can seem impossible. By incorporating psychological, social, and cognitive theories from Fritz Heider , Bernard Weiner , and Alfred Bandura , respectively, into what I think of as a “Frankensteined” Cycle of Motivation, I have been able to break through the motivation barrier. Using this strategy, I focus on what students attribute their successes to, on setting up mastery experiences and opportunities for productive struggle, and on providing goal-related feedback.

Getting started

To begin with, you can have a conversation with students about productive struggle. I would do this during morning meeting, even in grades as young as kindergarten. Productive struggle is working through challenges to reach your goal, and in kindergarten we said that productive struggle is “trying your best and never giving up.”

Creating an anchor chart for reference is important for continuing to reinforce the idea throughout the school year. The conversation on creating the chart is followed shortly by a conversation on attribution: When we succeed in our productive struggle, why? What do we attribute that success to? I have successfully had conversations about attribution and created an anchor chart in grades two through five.

The answers to the above questions should be limited to things that students can repeat and are a result of an action on their part. Being “smart” or “lucky,” for example, does not lead to success and isn’t repeatable because it isn’t in our control. Those descriptors are too vague. “Using my resources,” “asking for help,” and “studying or reading at night before bed” are all replicable actions that students can take to increase their subsequent chances of success.

A Classroom Culture of Motivation

During classwork and instruction, you can create opportunities for mastery experiences, purposeful opportunities that let students overcome a slightly difficult challenge so they can experience success and gain self-efficacy they’ll need for a more difficult challenge.

For example, when talking about comparing fractions in fourth grade, I start with ⅓ versus ⅔. While students are discussing the differences, ask how they know what they know. They might say they remember from third grade or they know about the number of parts or size of parts. Activate schema. They’re feeling confident and motivated to take risks. Ask if they’re ready for a challenge.

Challenges are nothing to be afraid of—they’re opportunities for growth—and I have never gotten a “no” at this point. Then challenge students with something like ⅓ and ⅙. This highlights common misconceptions. Ask them how they can use what they know to figure out what they don’t know. How can they use what they know about the number of parts and sizes of parts to figure out this question? Discuss. Ask questions and provide feedback.

When they have figured out a hard question, ask: How did we figure that out? What do we attribute our success to? Discuss the repeatable strategies they used, like using prior knowledge, reasoning, drawing a picture, discussing with a neighbor, etc. Then ask if they’re ready for another challenge. Their self-efficacy increases, which increases their internal motivation and their willingness to productively struggle.

For younger students, let’s say they are learning how to write letters. Start with o . It’s a circle (mastery experience). “Now, I wonder if you can write an a . Let’s try. It’s an o with a line.” Once they’ve done it, you’ll likely see increased motivation. “How did you know how to do that?” (Attribution). “Well, you just wrote an o and then a line because you knew how to write an o ! I wonder if we could try a d , since you know how to write an o and a line.” And repeat. Throughout their learning during whole or small group, partner, or independent practice, remind them of what they have attributed their success to in the past.

Include Goal-Setting

This is also applicable to assessments. You can goal-set with students. Conferencing with students prior to the assessment to discuss goals and what actions they can take to reach their achievable and measurable goal prepares them for the post-assessment conversation and helps them to verbally explain how they’re taking ownership of their success. Then, after the assessment, conferencing with them to reflect on whether they met their goal and why or why not allows them to become self-aware about how their actions control their outcomes.

“If we didn’t meet our goal, what can we add or subtract from our actions to ensure our success? Do we need to adjust our goal?” This is not a time for shaming—it is only a time for reflection on actions and outcomes.

“If we did meet our goal, what actions do we take to refine and repeat to continue our success?” Students begin to understand that there are things they can control, but also, sometimes, even when they try their best, they still might not reach their goal, and that’s OK. “What can we tweak to help ourselves? Tweak the goal? Tweak the supports? Tweak ourselves in some way?”

When incorporating this Cycle of Motivation in my classroom, 93 percent of my students reached a new growth band. In Texas, we have Did Not Meet, Met, and Masters for the state assessment. I had students who traditionally scored in Did Not Meet or Met who moved up to Masters, and that included students served in special education, by dyslexia services, etc.

This had never happened before, and I was recognized by my district of 30,000 students for this accomplishment. I definitely attribute this to the above strategy of helping students take ownership of their learning by empowering them to make better choices based on what they can control, challenging them to overcome struggles, celebrating them, and helping them recognize how their choices affect outcomes. They were the most motivated, most powerful learners I’d ever taught.

This strategy is meant to help students become self-aware and motivated and to increase their self-efficacy through successful productive struggle. Another powerful by-product of this strategy, however, is a classroom full of students who love a challenge (and might challenge you on occasion) and who are able to internalize how they can control more than they think.

Tapping the Power of Intrinsic Motivation

- Posted October 10, 2019

- By Emily Boudreau

Why is it that students are eager to start some tasks but not others? Why do some students complete certain assignments with care and other projects done by the same students are dashed off as quickly as possible or not completed at all?

Existing research on the science of learning provides some indication that targeting natural curiosity , providing choice in learning, and developing a growth mindset can help teachers guide their students toward motivation. And within the typical American classroom, students have a range of interests and outside experiences teachers can leverage to engage students.

Teachers may struggle to capitalize on this potential, wondering how to use these strengths to increase intrinsic motivation within everyday classroom activities. But they shouldn’t assume that some students are unmotivated by nature. “The biggest misconception [about motivation] is that students aren’t motivated,” says Rhonda Bondie , director of professional learning and lecturer at Harvard Graduate School of Education. “The good news is that everyone is motivated. It’s not that some people have it and some people don’t.”

Teachers can adjust the environment by using four levers in class culture to help students find their own motivation, says Bondie: autonomy, belonging, competence, and meaning (ABC+M) . Here are a few strategies that can help:

Make quality visible : Post required criteria for an assignment or more general criteria for all assignments in a highly visible part of the room. Also post what a task would need to exceed expectations.

- How it helps : A task becomes clear and alleviates confusion. Students will feel like they can begin and complete a task autonomously . Additionally, they will start to observe qualities in their own work that will help them demonstrate understanding in the future. By annotating where they see the qualities in their work students will recognize competence .

“The biggest misconception [about motivation] is that students aren’t motivated. The good news is that everyone is motivated. It’s not that some people have it and some people don’t.” – Rhonda Bondie

Provide a starting point : Ask students to check two things that seem familiar and circle one thing that seems new on a given assignment — a routine called Check, Circle, Old, and New. This will help with goal setting and reflection because it provides a visible starting point. “Usually when you say goal setting, [students] usually think more like New Year’s resolutions, and really goal setting can be as simple as asking students to jot down a starting position,” Bondie says.

- How it helps : This helps students break assignments down into tasks that appear more manageable. They feel a greater sense of belonging — and also find greater meaning in assignments — if they can see a relationship between new learning and previous experiences. While these modifications increase feelings of belonging and meaning, they also improve learning. “We’re really talking about setting cognitive goals for our thinking that encourage us to reflect and make connections and lead to deeper more effective learning at the same time,” Bondie says.

Find meaning in routines : “Whenever you want to engage students in a behavioral task such as lining up or cleaning the room, begin by presenting the problem as an opportunity for research or investigation,” Bondie suggests. For example, asking, “How long did it take us to get started this morning? How do we feel about that?” might provide an entry point for students to collect data about morning transitions and use it to determine how to make them faster.

- How it helps : A task like cleaning their desks or getting settled in the morning takes on meaning and provokes thinking when it is seen as a process that can be modified or changed based on what a student or class does or does not do. “Teachers can vary the thinking required for tasks, and the number of ways they’re asking students to put things together. We can control things that lead students to greater autonomy and feelings of competence ,” Bondie says.

Assign to reflection instead of completion : When students are completing the task for the teacher, school is work. However, tasks can be modified to support motivation throughout the process. Thinking routines like “I used to think ______ and now I think ______. So next I will _______,” can keep the learning going.