A Level Philosophy & Religious Studies

Natural Law ethics

Introduction.

Natural law ethics is based on Aristotelian teleology; the idea that everything has a nature which directs it towards its good end goal. Aquinas Christianised this concept. The Christian God designed everything with a telos according to his omnibenevolent plan for creation.

Christian ethics is most associated with the commands and precepts found in the Bible. Aquinas’ contribution was to argue that telos is also a source of Christian moral principles. Human nature has the God given ability to reason which comes with the ability both to intuitively know primary moral precepts and to apply them to moral situations and actions. Following this ‘natural law’ is thus also an essential element of living a moral life.

There is biblical evidence for this view from St Paul in Romans chapter 2:

“when Gentiles, who do not have the law, do by nature things required by the law … They show that the requirements of the law are written on their hearts, their consciences also bearing witness, and their thoughts sometimes accusing them and at other times even defending them.” (Romans 2:14-15).

Gentiles are those who are not Jewish, nor part of the newly-emerging Christianity when St Paul was writing. The ‘law’ refers to the religious law of the Hebrew bible or old testament. Paul clearly indicates that human beings have another source of morality. Not exactly the law itself, but the ‘requirements of the law’. This is ‘written on their hearts’ and found in their conscience. Aquinas thinks all humans are born with God-given reason, which involves the innate ability to intuitively know the moral precepts of natural law.

The ancient Greek idea of telos refers to a thing’s behavioural inclination towards its good end due to its nature.

The nature of a thing determines the behaviours that are ‘natural’ to it. An acorn naturally grows into an oak tree, because of the way its inherent nature is constituted. Birds fly south in winter, because of their natural instincts.

Natural law ethics claims that human beings are also born with a God-designed nature, including the power of reason. Reason intuitively knows certain things to be good or bad, thereby inclining humans towards following God’s morality. So, humans have a telos, a natural inclination towards our good end

“the light of reason is placed by nature in every man, to guide him in his acts towards his end”. – Aquinas.

Animals and natural objects have their behaviour determined by their telos. Humans, however, have free will. We are capable of choosing whether to follow God’s moral law or not. If we do, we will be orientating ourselves towards our good end of glorifying God by following his moral law. This achieves eudaimonia (flourishing), another Aristotelian concept that inspired Aquinas.

Like Aristotle, Aquinas thought eudaimonia can be achieved at the societal as well as the individual level. God has designed the telos of human beings so that a harmony of their individual interests can be achieved if they follow the natural law.

A person or society which fails to orient itself towards the glory of God will not flourish, but degenerate. This doctrine energised much of the preoccupation of Catholics with the moral fabric of society and their opposition to changes they feared would lead to moral degeneration.

So, on the natural law view, ethics is about following the natural law within our nature.

The four tiers of law

The ultimate source of moral goodness and thus law is God’s omnibenevolent nature, which created and ordered the universe with a divine plan, known as the eternal law. However, that is beyond our understanding. We only have access to lesser laws that derive from the eternal law.

The eternal Law . God’s plan, built into the nature of everything which exists, according to his omnibenevolent nature.

The divine law – God’s revelation to humans in the Bible.

The natural law – The moral law God created in human nature, discoverable by human reason.

Human law – The laws humans make which should be based on the natural and divine law. Human law gains its authority by deriving from the natural and divine law which themselves ultimately derive authority from God’s nature.

“Participation of the eternal law in the rational creature is called the natural law”. – Aquinas

The Primary Precepts & Synderesis

Reason is a power of the human soul. Synderesis is the habit or ability of reason to discover foundational ‘first principles’ of God’s natural moral law.

“the first practical principles … [belong to] a special natural habit … which we call “synderesis” … is said to incite to good, and to murmur at evil, inasmuch as through first principles we proceed to discover, and judge of what we have discovered.” – Aquinas

The first principle synderesis tells us is called the synderesis rule: that the good is what all things seek as their end/goal (telos). This means that human nature has an innate orientation to the good.

“This therefore is the principle of law: that good must be done and evil avoided. ” – Aquinas

Further to this, through synderesis we learn the primary precepts: worship God, live in an orderly society, reproduce, educate, protect and preserve human life and defend the innocent. These primary precepts are the articulation of the orientations in our nature toward the good; the natural inclinations of our God-designed human nature, put into the form of ethical principles by human reason. Simply having reason allows a being to intuitively know these precepts. We are all born with the ability to know them.

Secondary precepts & conscientia

“there belongs to the natural law, first, certain most general precepts, that are known to all; and secondly, certain secondary and more detailed precepts, which are, as it were, conclusions following closely from first principles.” – Aquinas.

Conscientia is the ability of reason to apply he primary precepts to situations or types of actions. The judgement we then acquire is a secondary precept. E.g euthanasia: the primary precepts don’t say anything about euthanasia exactly, but we can use our reason to apply the primary precepts to euthanasia, and realise that it goes against the primary precept of protecting and preserving human life. Arguably it even disrupts the functioning of society too. Therefore, we can conclude the secondary precept that euthanasia is wrong.

Interior & exterior acts

A physical action itself is an exterior act because it occurs outside of our mind. Our intention; what we deliberately choose to do, is the interior act because it occurs inside our mind.

The point of natural law ethics is to figure out what fulfils the telos of our nature and act on that. By doing so, we glorify God. This cannot be done without intending to do it. A good exterior act without a good interior act does not glorify God because it is not done with the intention of fulfilling the God-given goal/telos of our nature.

The act of giving money to charity is an example of a good exterior act, but is only morally good when combined with the right kind of intention, which would be an interior act. If the intention was only to be thought of as a good person, which is not the right kind of intention, then the action is not truly morally good.

Whether telos exists

It is a strength of telos-based ethics that they are empirical, i.e., based on evidence. Aristotle observed that everything has a nature which inclines it towards a certain goal which he and Aquinas called its telos. It is a biological fact that certain behaviours cause an organism to flourish. Telos thus seems an empirically valid concept.

Weakness: Modern science’s rejection of final causation. Francis Bacon, called the father of empiricism, argued that only material and efficient causation were valid scientific concepts, not formal and final causation. The idea of telos is unscientific.

Aquinas and Aristotle claim every being has a unique essence which gives it a particular end/purpose. The issue is, modern science tells us that things are merely atoms moving in fields of force – i.e., material and efficient causation. The idea that entities have an ‘essence’ and thus a telos is unscientific. Physicist Sean Carroll concludes that purpose is not built into the “architecture” of the universe.

All supposed telos of a thing can be reduced to non-teleological concepts regarding its material structure and forces operating on it (material & efficient causation). There is no basis for grounding telos in God like Aquinas did, or as a required explanation of change like Aristotle did. For example, Aristotle would regard the telos of a seed as growing into a tree/bush. However, we now understand that change as resulting from the seed’s material structure which was itself caused by evolution, not anything like telos. Similarly, if there is anything in human nature which orients us towards certain behaviours, it is only because evolution programmed them into us because they happened to enable survival in our environment, not because of telos. So, Modern science can explain the world without telos. Telos is an unnecessary explanation.

Evaluation defending telos:

Polkinghorne, a modern Christian philosopher and physicist, argued that science is limited and cannot answer all questions. It can tell us the what but not the why . Science can tell us what the universe is like, but it cannot tell us why it is this way, nor why it exists. It cannot answer questions about purpose.

Polkinghorne’s argument is successful because science is limited. It cannot rule out something like a prime mover or God which could provide some kind of telos. If purpose existed, science would not be able to discover it. So, science cannot be used to dismiss the existence of purpose.

Evaluation critiquing telos:

Dawkins responds that it’s not valid to simply assume that there actually is a ‘why’. He makes an analogy: ‘what is the color of jealousy?’ That question is assuming that jealousy has a color. Similarly, just because we can ask why we and the universe exist, that doesn’t mean there actually is a purpose for it.

Dawkins’ argument is successful because it makes use of the burden of proof. Those who claim purpose exists have the burden of providing a reason to think it exists. There is no scientific basis for thinking anything other than material and efficient causation exists. Furthermore, scientists may one day actually explain ‘why’ the universe exists, but even if they don’t, that doesn’t justify a non-scientific explanation of purpose such as telos.

Universal human nature & moral dis/agreement

A strength of Natural law is that it is based on universal human nature. The primary precepts are found in the morality of all societies. For example, not killing for no reason and rules about stealing are universal. Valuing reproduction and education are also universal. Moral thinkers from different cultures came up with similar moral prescriptions such as the golden rule; to treat others as you would like to be treated, which can be found in ancient Chinese Philosophy, Hinduism, Judaism and Christianity. This suggests that moral views are influenced by a universal human moral nature. This is good evidence that we are all born with a moral orientation towards the good (telos), which is the foundation of Aquinas’ theory.

Weakness: If all humans were really born with the ability to know the primary precepts, we should expect to find more moral agreement than we do. In fact, we find vastly different moral beliefs. Furthermore, the disagreement is not random but tends to fall along cultural lines. This suggests that it is actually social conditioning which causes our moral views, not a supposed natural law in human nature. This has been argued by psychologists like Freud. Fletcher argues this shows there is not an innate God-given ability of reason to discover a natural law. He concludes that ethics must be based on faith, not reason (Fletcher’s positivism).

Evaluation defending Aquinas:

Aquinas’ claim is merely that human nature contains an orientation towards the good, it doesn’t involve a commitment to humans actually doing more good than evil, nor to incredibly evil acts or cultures occurring infrequently. Aquinas acknowledges that there are many reasons we might fail to do good despite having an orientation towards it. These include original sin, mistakes in conscientia, lacking virtue and a corrupt culture. So, the fact that there is a core set of moral views found cross-culturally shows his theory is correct.

Evaluation critiquing Aquinas:

Furthermore, cross-cultural morality might result merely from the basic requirement of a society to function. If anyone could kill or steal from anyone else for no reason whenever they wanted, it’s hard to see how a society could exist. That might create an existential pressure which influences the moral thinkers of a society, yielding prescriptions such as the golden rule. Cross-cultural ethics therefore has a practical reality as its basis, not God.

Alternatively, some of the cross-cultural similarities in moral codes might also have resulted from a biologically evolved moral sense rather than one designed by a God, which would mean they are not related to morality or telos at all.

Aquinas’ Natural theology vs Augustine & Karl Barth

A strength of Aquinas’ ethics is its basis in what seems like a realistic and balanced view of human nature as containing both good (reason & telos) but also bad (original sin). Natural law adds an engagement with autonomy to Christian ethics. Sola scriptura protestants like Calvin regard humans as mere passive receptacles for a set of biblical commands. However, Aquinas argues that God presumably gave humans reason so that they may use it.

Natural theology is the view that human reason is capable of knowing God, in this case God’s moral law. Aquinas defends this by first accepting that original sin destroyed original righteousness, meaning perfect rational self-control. However, it did not destroy our reason itself and its accompanying telos inclining us towards the good.

Only rational beings can sin. It makes no sense to say that animals could sin. Original sin made us sinners, but human nature was not reduced to the level of animals. We still have the ability to reason. Furthermore, Aquinas diverges from Augustine, claiming that concupiscence can sometimes be natural to humans, in those cases where our passions are governed by our reason. So, a comprehensive approach to Christian morality must include the use of reason to discover and act on the telos of our nature.

Weakness: Natural theology places a dangerous overreliance on human reason. Karl Barth was influenced by Augustine, who claimed that after the Fall our ability to reason become corrupted by original sin. Barth’s argument is that is therefore dangerous to rely on human reason to know anything of God, including God’s morality. “the finite has no capacity for the infinite” – Karl Barth. Our finite minds cannot grasp God’s infinite being. Whatever humans discover through reason is not divine, so to think it is divine is idolatry – believing earthly things are God. Idolatry can lead to worship of nations and even to movements like the Nazis. After the corruption of the fall, human reason cannot reach God or God’s morality. That is not our telos. Only faith in God’s revelation in the bible is valid.

Final judgement defending Aquinas: Barth’s argument fails because it does not address Aquinas’ point that our reason is not always corrupted and original sin has not destroyed our natural orientation towards the good. Original sin can at most diminish our inclination towards goodness by creating a habit of acting against it. Sometimes, with God’s grace, our reason can discover knowledge of God’s existence and natural moral law. So, natural moral law and natural theology is valid.

Arguably Aquinas has a balanced and realistic view, that our nature contains both good and bad and it is up to us to choose rightly.

Final judgement critiquing Aquinas: Barth still seems correct that being corrupted by original sin makes our reasoning about God’s existence and morality also corrupted. Even if there is a natural law, we are unable to discover it reliably. The bad in our nature unfortunately means we cannot rely on the good. Whatever a weak and misled conscience discovers is too unreliable.

Humanity’s belief that it has the ability to know anything of God is the same arrogance that led Adam and Eve to disobey God. Humanity believing that it has the power to figure out right and wrong is what led to the arrogant certainty of the Nazis in their own superiority. This arrogance of natural theology is evidence of a human inability to be humble enough to solely rely on faith.

Whether Religious & Natural law ethics is outdated

A strength of Natural law ethics is its availability to everyone because all humans are born with the ability to know and apply the primary precepts. Regarding those who do not belong to Abrahamic religion the Bible says: “Gentiles, who do not have the law, do by nature what the law requires … God’s law is written in their hearts, for their own conscience and thoughts either accuse them or tell them they are doing right” (Romans 2:14-15). So, it is possible to follow the natural law even if you are not Christian and/or have no access to the divine law (Bible).

Weakness: Secularists often argue that biblical morality (divine law) is primitive and barbarous, showing it comes from ancient human minds, not God. J. S. Mill calls the Old Testament “Barbarous, and intended only for a barbarous people”. Freud similarly argued that religious morality reflected the “ignorant childhood days of the human race”. Aquinas’ Natural law ethics is criticised as outdated for the same reason. Medieval society was more chaotic. Strict absolutist ethical principles were needed to prevent society from falling apart. This could explain the primary precepts. For example, it was once useful to restrict sexual behaviour to marriage, because of how economically fatal single motherhood tended to be. It was useful to simply ban all killing, because killing was much more common. It was useful to require having lots of children, because most children died. The issue clearly is that all of these socio-economic conditions have changed. So, the primary precepts are no longer useful. Society can now afford to gradually relax the inflexibility of its rules without social order being threatened.

Conservative Catholics often argue that natural law is not outdated because it serves an important function without which society flourishes less. They argue that secular liberal western culture is ethically retrograde because of its abandonment of traditional moral principles like the primary precepts. This shows that we really do need to follow God’s natural law in order to flourish.

Marriages are fewer and less successful. Mental illness increases. Rates of etcetc

People are no longer united by an ethic of devoting our lives to something greater than ourselves. Self-interest and materialistic consumerism is all modern society has to offer by way of meaning and purpose.

“[excluding] God, religion and virtue from public life leads ultimately to a truncated vision of man and of society and thus to a ‘reductive vision of the person and his destiny’”. – Pope Benedict XVI.

Here, Benedict XVI references an encyclical called “Caritas in Veritate”, where he argued that while there is indeed religious fanaticism which runs against religious freedom, the promotion of atheism can deprive people of “spiritual and human resources”. The atheist worldview is that we are a “lost atom in a random universe”, in which case we can grow and evolve, but not really develop morally.

“ideological rejection of God and an atheism of indifference, oblivious to the Creator and at risk of becoming equally oblivious to human values, constitute some of the chief obstacles to development today. A humanism which excludes God is an inhuman humanism. Only a humanism open to the Absolute can guide us in the promotion and building of forms of social and civic life — structures, institutions, culture and ethos — without exposing us to the risk of becoming ensnared by the fashions of the moment.” – Pope Benedict XVI.

So, religious and natural law ethics is not outdated but is a vital societal anchor for morality, meaning and purpose.

Natural law ethics is outdated because Aquinas’ theory was actually a reaction to his socio-economic context and since that has changed, Natural law is no longer relevant.

Aquinas thought that he discovered the primary precepts through human reason, as God designed. However, it’s a simpler explanation that Aquinas was simply intuiting what was good for people in his socio-economic condition. The idea that the resulting principles actually came from God was only in his imagination.

The great strength of religion as a form of social organisation is also its greatest weakness. By telling people that its ethical precepts (such as the primary precepts or sanctity of life) come from God it creates a strong motivation to follow them. Yet, because those precepts are imagined to come from an eternal being, they become inflexible and painstakingly difficult to progress. This makes them increasingly outdated.

The double effect

A single action can have two effects, one in accordance with the primary precepts and one in violation of them. Aquinas claims that such actions can be justified the good effect is intended while the bad effect is “beside the intention”. This is because being a good person involves developing the kind of virtuous character which acts with the intention of following God’s natural law.

Aquinas illustrated this with killing in self-defence. There are two effects; the saving of a life and the killing of a life. Killing someone, which clearly violates the primary precept of preserving human life, can be justified so long as it is an effect which is a secondary effect beside the intention of an action whose other effect was intended and was in accordance with the primary precepts.

There are four generally accepted conditions in modern Catholicism for an action to be justified by the double effect:

The intentionality condition. The good effect must be intended and the bad effect must be ‘besides the intention’. Aquinas illustrated the double effect with the example of killing someone in self-defence. So long as you intended to save your own life, then it is morally permissible to kill someone in self-defence. The bad effect is ‘besides the intention’.

The proportionality condition. The good effect must be at least equivalent to the bad effect. Saving your life is equivalent to ending the life of the attacker. You can’t use more force than is necessary to save your life – there must be proportionality there too.

The means-end condition. The bad effect and the good effect must both be brought about immediately – at the same time. Otherwise, the person would be using a bad effect as a means to bring about a good effect – which is not permissible.

The double effect only applies to actions which have two effects – one good, one bad – where both effects are brought about immediately.

The nature of the act condition. The action must be either morally good, indifferent or neutral. Acts such as lying or killing an innocent person can never be justifiable. An attacker would not count as an innocent person.

Whether the double effect is unbiblical

A strength of the double effect is that it helps to resolve seemingly disparate biblical themes. Jesus’ commands were not merely about following certain rules, but also about having the right moral intention and virtue (E.g. sermon on the mount). The double effect provides important clarity to Christian ethics by showing the relation between the important moral elements of intention and following the moral law. Good intention is important, not to the degree of justifying pure violations of the law, but when involved in an action that has a good effect it can justify permitting a bad side effect.

Weakness: the double effect is unbiblical. Some theologians reject the double effect as unbiblical because God’s commandments are presented as absolute and not dependent on someone’s intention. For those theologians, the distinction between intended effects of actions and merely foreseen effects “beside” the intention has no morally relevant significance. It’s not that intention has no relevance in traditional Christian ethics. Most theologians accept that people are not immoral for consequences of their actions which they could not have foreseen which violate God’s commands. For example if you decide to drive your car at the time a drunk person happened to be out and you ran them over, that would not be considered your fault even through it was an effect of your action. However if you could foresee a bad consequence, the fact that it was a secondary effect beside the effect you did intend doesn’t justify it for theologians who take this view.

Evaluation defending Natural law:

This criticism is unsuccessful because Natural law is different to the Bible. The Bible might be inflexible, but that is the divine law. The natural law in our nature is more flexible because it is in the form of very general precepts which require application and the telos of the natural law is glorifying God, which requires that it be our intention to glorify God – thus showing how intention is relevant.

Evaluation criticising Natural law:

This weakness is successful because it shows natural law is trying to add flexibility to inflexible biblical law – e.g. thou shalt not kill. Self-defence, passive euthanasia, even perhaps abortion could be justified by the double effect. The natural and divine law do not cover separate areas but cross-over and therefore conflict on this point of inflexibility. Christians must choose the Bible over Natural law.

Proportionalism & the double effect

A strength of Natural law is its flexibility due to the doctrine of the double effect.

This has been used by modern Catholics to allow, for example, passive euthanasia, abortion to save the life of the mother (though this is complex and controversial in catholicism), and contraception to prevent the spread of AIDS.

Weakness: B. Hoose’s proportionalism

Hoose developed natural law into what he claimed was a more flexible and coherent form called proportionalism.

Proportionalists agree about following the primary precepts, but argue it is acceptable to go against them if you have a proportionate reason for doing so – i.e., if your action will bring about more good than bad.

The nature of the act condition is invalid because what matters is the proportion of value to disvalue produced by your action. The means-end condition is invalid because what matters is the ultimate value/disvalue proportion.

For proportionalists, the only valid condition in the double effect is proportionality and your intention must be to act with with a proportionate reason.

E.g., Hoose would agree with Fletcher’s example of killing a baby to save the lives of its family. It brings about more value than disvalue, so we have a proportionate reason for breaking the primary precepts in that case.

A resulting strength of proportionalism is it’s far greater flexibility.

Euthanasia, abortion, genetic engineering, anything natural law said to be wrong could in principle be right depending on whether there is a proportionate reason for doing them in a particular situation. There are no intrinsically evil actions. An action can be intrinsically in violation of the principles of natural law, but for proportionalism that doesn’t establish wrongness.

Hoose’s argument for the greater coherence of proportionalism.

Aquinas said it’s bad to go against the primary precepts, but it could overall be justified through the double effect in some cases.

Hoose objects that an overall good act cannot be composed of bad parts (e.g breaking the precepts). Moral evil is moral evil, it could never be a component of moral goodness.

Moral actions are composed of parts like intention and their dis/accordance with the precepts, but those parts cannot be called good or bad in themselves. Only the overall act can be good or bad. So, no part of an action can be morally bad, including what the action itself is and whether it breaks the precepts.

The ‘parts’ of an action are still good/evil, not in a moral sense but in a factual or physical sense, regarding their enabling or disabling of flourishing (eudaimonia).

Factual enabling of flourishing ‘Ontic goods’. These are physical or factual goods, such as health, life and knowledge (these all enable flourishing and are thus ontic goods). ‘Ontic evils’ are the deprivation of such goods. Whatever in an action enables flourishing is an ‘ontic good’, whatever disables it is an ‘ontic evil’.

To decide whether the action is overall morally good however, we need to judge whether the action produced more ontic good compared to ontic evil. If it does, we have a proportionate reason for doing it, even if it goes against the primary precepts.

Aquinas would say killing the baby in Fletcher’s example is just morally evil – but Hoose is saying no, it’s only an ontic evil – which must be measured against the ontic good caused by the action (saving the whole family). If there’s a proportionate reason for doing it, then it is a morally good act to kill the baby.

“An act is either morally right or morally wrong. It cannot be both. If we talk of morally evil (meaning morally wrong) elements in an act that is morally right and is performed by a morally good person, we confuse the whole issue.” – B. Hoose.

Evaluation defending Natural law

John Paul II defends Natural law ethics, arguing that proportionalism is not a valid development because it misunderstands the objective/intention required for ethical action.

“Acting is morally good when the choices of freedom are in conformity with man’s true good and thus express the voluntary ordering of the person towards his ultimate end” – John Paul II

Under natural law, we intentionally act on the moral law discovered in our nature by reason (primary precepts). God designed us to intuitively know these moral laws – so our telos/purpose is to follow them. The goal of natural law is to follow the primary precepts. John Paul II is correct that Proportionalism misdirects our goal/intention towards the balance of ontic goods over evils produced by our action. God has designed us to follow the primary precepts – so that is our ethical purpose. Hoose misdirects us away from that.

“The morality of the human act depends primarily and fundamentally on the “object” rationally chosen by the deliberate will, as is borne out by the insightful analysis, still valid today, made by Saint Thomas.” – John Paul II.

Evaluation criticising Natural law

Defenders of traditional Natural law like John Paul II assume that our ultimate end is simply to follow the precepts of natural law in a ridged deontological way.

Calculating the ontic goods over evils of our actions could actually be part of our ultimate end.

Even Aquinas accepted that his list of primary precepts was not final but could be added to. The project of understanding the telos of our nature is ongoing. Developments like those of proportionalism cannot be dismissed simply because they differ with the traditional approach.

Whether proportionalism is better suited to our fallen world

A strength of the double effect is that it is pragmatic.

It fits with the reality of moral decision making. Sometimes actions can have two effects and a method is required that makes sense of how to judge them. Aquinas’ self-defence illustration is intuitive.

Proportionalism has the strength of being better suited to moral decision making in our imperfect world.

The Fall destabilised creation, including the moral order. God designed the natural law to perfectly fit following it with human flourishing. In a post-lapsarian world, the presence of ontic evil around acts that follow the natural law sometimes mean they prevent flourishing. Taking a deontological approach to natural law doesn’t make sense.

Ontic goods and evils are defined in relation to whatever enables or disables flourishing. Flourishing is part of our telos. So arguably following proportionalism would successfully orientate us towards our telos.

Weakness: John Paul II argues that although consequences matter, proportionalism takes that too far when it claims that there are no intrinsically evil actions.

It can never enable achievement of our telos to do such acts. Consequences certainly matter, but they can never make an intrinsically evil act acceptable. Such acts disorder us; they can never rightly order us towards our end, even if done with the intention of bringing about a greater balance of ontic goods over ontic evils. It is better to avoid them and bear the consequences, even if it means suffering and dying. JP2 reminds us that early Christians were prepared to be martyred for their faith.

Only intentionally following of the natural law within our nature aims us at our telos of glorifying God. Consequences matter to some degree, but not to the point of justifying intrinsically evil acts.

“Christian ethics, which pays particular attention to the moral object, does not refuse to consider the inner ‘teleology’ of acting, inasmuch as it is directed to promoting the true good of the person; but it recognizes that it is really pursued only when the essential elements of human nature are respected. The human act, good according to its object, is also capable of being ordered to its ultimate end … If acts are intrinsically evil, a good intention or particular circumstances can diminish their evil, but they cannot remove it … an intention is good when it has as its aim the true good of the person in view of his ultimate end. But acts whose object is ‘not capable of being ordered’ to God and ‘unworthy of the human person’ are always and in every case in conflict with that good.” – John Paul II.

Evaluation defending proportionalism

John Paul II’s reference to the Christian Martyrs is a self-serving illustration. It’s easy for most people to make sense of sacrificing oneself rather than break the natural law. However, what about cases where if we don’t break the natural law, we will be letting others suffer and die? Euthanasia is a clear example.

Evaluation criticising proportionalism

This is the ultimate argument against all forms of religious consequentialism. They misunderstand the purpose of morality. We are not here on earth to achieve happiness, but to follow God’s moral law. If suffering results from following God’s law due to living in a fallen world, that doesn’t invalidate God’s law. Aristotle and Aquinas both explained that flourishing is not happiness, but cultivating the virtues which rationally order us in our actions towards our end. As JP2’s example of the martyrs shows, if it is virtuous to suffer and die then that is what we should do, technically that is flourishing. Cardinal Newman expressed this sentiment in a poetic if stark manner:

“The Catholic Church holds it better for the sun and moon to drop from heaven, for the earth to fail, and for all the many millions on it to die of starvation in extremest agony … than that one soul, I will not say, should be lost, but should commit one single venial sin, should tell one willful untruth, or should steal one poor farthing without excuse.” – John Henry Newman.

Suggested extra reading and media links

Youtube playlist for this topic:

Suggested books for this topic:

Suggested pages on other websites for this topic:

Quick links

Home — Essay Samples — Philosophy — Natural Law — Natural Law by Thomas Aquinas: an Examination

Natural Law by Thomas Aquinas: an Examination

- Categories: Natural Law

About this sample

Words: 514 |

Published: Dec 12, 2018

Words: 514 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Explain Aquinas’ Natural Law theory

Works cited.

- Bridges, T. J. (2014). Aquinas on natural law. Routledge.

- Cessario, R. J. (2001). The moral philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas. Catholic University of America Press.

- Garcia, J. L. A. (1996). Natural law and practical rationality. Cambridge University Press.

- Kreeft, P. (2018). Summa of the Summa. Ignatius Press.

- Lisska, A. J. (1996). Aquinas's theory of natural law: An analytic reconstruction. Oxford University Press.

- Murphy, M. C. (2001). Natural law and practical rationality in Aquinas. American Catholic Philosophical Quarterly, 75(1), 1-16.

- Pieper, J. (1997). The four cardinal virtues. University of Notre Dame Press.

- Regan, R. J. (2002). The educational theory of St. Thomas Aquinas. Ave Maria Press.

- Spiazzi, R. (1965). The moral philosophy of St. Thomas: Ethical theory and moral practice. Newman Press.

- Von Hildebrand, D. (2005). The nature of love. Sophia Institute Press.

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr Jacklynne

Verified writer

- Expert in: Philosophy

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1547 words

1 pages / 635 words

3 pages / 1309 words

5 pages / 2242 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

In the 1800s the industrial revolution caused many people to reconsider the laws that were introduced to society. One of the people who wanted change was an English Philosopher named Jeremy Bentham. His views on the law came [...]

Who could forget the famous words of the unforgettable Martin Luther King Jr., “Injustice everywhere is a threat to justice everywhere”. This theme is expressed throughout King’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail conveying his legal [...]

This paper covers the central theme of Moral (Cultural) Relativism. It is essentially the idea that morally acceptable conduct is determined and set by culture. The key factor is that the moral codes of a certain culture are [...]

Just War Theory analyzes all aspects of why and how war should be fought and conducted. Just War has been discussed in Europe as far back as Cicero, and there have been several other texts in other civilizations with similar [...]

The term Tabula Rasa suggests that we are born as a “blank slate”, implying that we are born without any form of conscious knowledge whatsoever, and that we gain our information through sense experience of the world. In this [...]

Functionalism is a consensus theory that sees society as a complex structure whose parts have to work together in order to function. Emile Durkheim was the one to come up with this theory, he initially envisioned society as an [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Humanities ›

- The U. S. Government ›

- U.S. Legal System ›

Natural Law: Definition and Application

ziggymaj / Getty Images

- U.S. Legal System

- History & Major Milestones

- U.S. Constitution & Bill of Rights

- U.S. Political System

- Defense & Security

- Campaigns & Elections

- Business & Finance

- U.S. Foreign Policy

- U.S. Liberal Politics

- U.S. Conservative Politics

- Women's Issues

- Civil Liberties

- The Middle East

- Race Relations

- Immigration

- Crime & Punishment

- Canadian Government

- Understanding Types of Government

- B.S., Texas A&M University

Natural law is a theory that says all humans inherit—perhaps through a divine presence—a universal set of moral rules that govern human conduct.

Key Takeaways: Natural Law

- Natural law theory holds that all human conduct is governed by an inherited set of universal moral rules. These rules apply to everyone, everywhere, in the same way.

- As a philosophy, natural law deals with moral questions of “right vs. wrong,” and assumes that all people want to live “good and innocent” lives.

- Natural law is the opposite of “man-made” or “positive” law enacted by courts or governments.

- Under natural law, taking another life is forbidden, no matter the circumstances involved, including self-defense.

Natural law exists independently of regular or “positive” laws—laws enacted by courts or governments. Historically, the philosophy of natural law has dealt with the timeless question of “right vs. wrong” in determining the proper human behavior. First referred to in the Bible, the concept of natural law was later addressed by the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle and Roman philosopher Cicero .

What Is Natural Law?

Natural law is a philosophy based on the idea that everyone in a given society shares the same idea of what constitutes “right” and “wrong.” Further, natural law assumes that all people want to live “good and innocent” lives. Thus, natural law can also be thought of as the basis of “morality.”

Natural law is the opposite of “man-made” or “positive” law. While positive law may be inspired by natural law, natural law may not be inspired by positive law. For example, laws against impaired driving are positive laws inspired by natural laws.

Unlike laws enacted by governments to address specific needs or behaviors, natural law is universal, applying to everyone, everywhere, in the same way. For example, natural law assumes that everyone believes killing another person is wrong and that punishment for killing another person is right.

Natural Law and Self Defense

In regular law, the concept of self-defense is often used as justification for killing an aggressor. Under natural law, however, self-defense has no place. Taking another life is forbidden under natural law, no matter the circumstances involved. Even in the case of an armed person breaking into another person’s home, natural law still forbids the homeowner from killing that person in self-defense. In this way, natural law differs from government-enacted self-defense laws like so-called “ Castle Doctrine ” laws.

Natural Rights vs. Human Rights

Integral to the theory of natural law, natural rights are rights endowed by birth and not dependent on the laws or customs of any particular culture or government. As stated in the United States Declaration of Independence , for example, the natural rights mentioned are “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.” In this manner, natural rights are considered universal and inalienable, meaning they cannot be repealed by human laws.

Human rights, in contrast, are rights endowed by society, such as the right to live in safe dwellings in safe communities, the right to healthy food and water, and the right to receive healthcare. In many modern countries, citizens believe the government should help provide these basic needs to people who have difficulty obtaining them on their own. In mainly socialist societies , citizens believe the government should provide such needs to all people, regardless of their ability to obtain them.

Natural Law in the US Legal System

The American legal system is based on the theory of natural law holding that the main goal of all people is to live a “good, peaceful, and happy” life, and that circumstances preventing them from doing so are “immoral” and should be eliminated. In this context, natural law, human rights, and morality are inseparably intertwined in the American legal system.

Natural law theorists contend that laws created by the government should be motivated by morality. In asking the government to enact laws, the people strive to enforce their collective concept of what is right and wrong. For example, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was enacted to right what the people considered to be a moral wrong—racial discrimination. Similarly, the peoples’ view of enslavement as being a denial of human rights led to ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868.

Natural Law in the Foundations of American Justice

Governments do not grant natural rights. Instead, through covenants like the American Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution , governments create a legal framework under which the people are permitted to exercise their natural rights. In return, people are expected to live according to that framework.

In his 1991 Senate confirmation hearing, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas expressed the widely shared belief that the Supreme Court should refer to natural law in interpreting the Constitution. “We look at natural law beliefs of the Founders as a background to our Constitution,” he stated.

Among the Founders who inspired Justice Thomas in considering natural law to be an integral part of the American justice system, Thomas Jefferson referred to it when he wrote in the first paragraph of the Declaration of Independence:

“When, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the laws of nature and of nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.”

Jefferson then reinforced the concept that governments cannot deny rights granted by natural law in the famous phrase:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Natural Law in Practice: Hobby Lobby vs. Obamacare

Deeply rooted in the Bible, natural law theory often influences actual legal cases involving religion. An example can be found in the 2014 case of Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores , in which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that for-profit companies are not legally obligated to provide employee health care insurance that covers expenses for services that go against their religious beliefs.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 —better known as “Obamacare”—requires employer-provided group health care plans to cover certain types of preventative care, including FDA-approved contraceptive methods. This requirement conflicted with the religious beliefs of the Green family, owners of Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., a nationwide chain of arts and crafts stores. The Green family had organized Hobby Lobby around their Christian principles and had repeatedly stated their desire to operate the business according to Biblical doctrine, including the belief that any use of contraception is immoral.

In 2012, the Greens sued the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, claiming that the Affordable Care Act’s requirement that employment-based group health care plans cover contraception violated the Free Exercise of Religion Clause of the First Amendment and the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), that “ensures that interests in religious freedom are protected.” Under the Affordable Care Act, Hobby Lobby faced significant fines if its employee health care plan failed to pay for contraceptive services.

In considering the case, the Supreme Court was asked to decide if the RFRA allowed closely held, for-profit companies to refuse to provide its employees with health insurance coverage for contraception based on the religious objections of the company’s owners.

In a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court held that by forcing religion-based companies to fund what they consider the immoral act of abortion, the Affordable Care Act placed an unconstitutionally “substantial burden” on those companies. The court further ruled that an existing provision in the Affordable Care Act exempting non-profit religious organizations from providing contraception coverage should also apply to for-profit corporations such as Hobby Lobby.

The landmark Hobby Lobby decision marked the first time the Supreme Court had recognized and upheld a for-profit corporation’s natural law claim of protection based on a religious belief.

Sources and Further Reference

- “ Natural Law .” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- “ The Natural Law Tradition in Ethics .” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2002-2019)

- “Hearing of the Senate Judiciary Committee on the Nomination of Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court. Part 1 , Part 2 , Part 3 , Part 4 .” U.S. Government Publishing Office.

- What Is Parens Patriae? Definition and Examples

- What Is Statutory Law? Definition and Examples

- What Is Civil Law? Definition and Examples

- What Is Qualified Immunity? Definition and Examples

- What Is a Writ of Certiorari?

- What Is Judicial Restraint? Definition and Examples

- What Is Sedition? Definition and Examples

- Obergefell v. Hodges: Supreme Court Case, Arguments, Impacts

- What Is Administrative Law? Definition and Examples

- What Is a Protected Class?

- The Warren Court: Its Impact and Importance

- What Is Corporal Punishment? Is It Still Allowed?

- What Is Identity Theft? Definition, Laws, and Prevention

- What Is Originalism? Definition and Examples

- What Is an Amicus Brief?

- Court Case of Korematsu v. United States

Thomistic Philosophy Page

Natural Law

St. Thomas Aquinas on the Natural Law.

After his Five Ways of Proving the Existence of God ( ST Ia, 2, 3 ), St. Thomas Aquinas is probably most famous for articulating a concise but robust understanding of natural law. Just as he claims and demonstrates in his proofs for God’s existence that natural human reason can come to some understanding of the Author of nature, so in his exposition of natural law, Aquinas shows that human beings can discover objective moral norms by reasoning from the objective order in nature, specifically human nature. While Aquinas believes that this objective order of nature (and the operation of human reason which discovers it) are, in fact, ultimately grounded and established by God’s intelligent willing of the good of creation (i.e., His love), Aquinas’s understands that one need not know that God’s providence underpins the objective order of nature. Thus, whether or not one believes in or rationally proves there is a God, one can recognize and be bound by the natural law for, according to Aquinas, it applies to all people at all times, and in some sense is known by all rational humans (though, of course, they do not (but should) always act in accordance with it).

Eternal Law

In his monumental Summa Theologiae , St. Thomas Aquinas , devotes relatively little space to the natural law – merely a single question and passing mention in two others. There, he bases his doctrine of the natural law, as one would expect, on his understanding of God and His relation to His creation. He grounds his theory of natural law in the notion of an eternal law (in God). In asking whether there is an eternal law, he begins by stating a general definition of all law: Law is a dictate of reason from the ruler for the community he rules.

This dictate of reason is first and foremost within the reason or intellect of the ruler. It is the idea of what should be done to ensure the well-ordered functioning of whatever community the ruler has care for. (It is a fundamental tenet of Aquinas’ political theory that rulers rule for the sake of the governed, i.e., for the good and well-being of those subject to the ruler.) Since he has elsewhere shown that God rules the world with his reason (since he is the cause of its being (cf. Summa Theologiae I 22, 1-2) ), Aquinas concludes that God has in His intellect an idea by which He governs the world. This Idea, in God, for the governance of things is the eternal law. ( ST I-II, 91, 1)

Defining the Natural Law

Next, Aquinas asks whether there is in us a natural law. First, he makes a distinction: A law is not only in the reason of a ruler, but may also be in the thing that is ruled. Just as the plan or rule for constructing a house resides primarily in the mind of an architect, so that plan or rule can be said also to be in the house so constructed, imprinted, as it were, into the very composition of the house and dictating how the house is properly to operate or function (cf. ST I-II, 93, 1 ).

In the case of the eternal law, the things of creation that are ruled by that law have it imprinted on the them through their nature or essence. Since things act according to their nature, they derive their “respective inclinations to their proper acts and ends” ( final cause ) according to the law that is written into their nature. Everything in nature, insofar as they reflect the order by which God directs them through their nature for their own benefit, reflects the eternal law in their own natures ( ST I-II, 91, 2)

The natural law is properly applied to the case of human beings, and acquires greater precision because of the fact that we have reason and free will . It is our nature as humans to act freely (i.e., to be provident for ourselves and others) by directing ourselves toward our proper acts and end. That is, we human beings must exercise our natural reason to discover what is best for us in order to achieve the end to which our nature inclines. Furthermore, we must do this through the exercise our freedom, by choosing what reason determines to be naturally suited to us, i.e., what is best for our nature.

Now among all others, the rational creature is subject to Divine providence in the most excellent way, in so far as it partakes of a share of providence, by being provident both for itself and for others. Wherefore it has a share of the Eternal Reason, whereby it has a natural inclination to its proper act and end: and this participation of the eternal law in the rational creature is called the natural law . ( ST I-II, 91, 2)

The natural inclination of humans to achieve their proper end through reason and free will is the natural law. Formally defined, the natural law is humans’ participation in the eternal law, through reason and will. Humans actively participate in the eternal law of God (the governance of the world) by using reason in conformity with the natural law to discern what is good and evil . Just as the proper functioning of the body and its organs in order to achieve an optimal physical life defines health and the rules of medicine and healthy living, so the proper functioning of all human faculties defines the human good and the rules for living well (morally, spiritually, socially, etc.). The natural law encompasses the rules and precepts by which humans do good actions and live well, individually and collectively.

The Human Good

In applying this universal notion of natural law to the human person, one first must decide what it is that (God has ordained) human nature is inclined toward. Since each thing has a nature (given it by God), and each thing has a natural end, so there is a fulfillment to human activity of living. Even apart from knowing about this dependence on God, one can discover by reason what the purpose of living is, and so he or she will discover what his or her natural end is. Building on the insight of Aristotle that “happiness is what all desire,” a person can conclude that they will be happy when he or she achieves this natural end, specifically “a life of virtuous activity in accordance with reason” ( Nicomachean Ethics , I, 7 ; see Aquinas, Commentary, Bk. I, C h. 10, nos. 127-8 ). The commands or precepts, then, that lead to human happiness or flourishing is what Aquinas means by the natural law.

Aquinas distinguishes different levels of precepts or commands that constitute or comprise the natural law. The most universal is the command “Good is to be done and pursued and evil avoided ” ( ST I-II, 94, 2 ). This applies to everything and everyone, so much so that some consider it to be more of a description or definition of what we mean by “good.” For these philosophers, a thing is “good” just in case it is pursued or done by someone. Aquinas would agree with this to a certain extent; but he would say that that is a definition of an apparent good. Thus, this position of Aquinas has a certain phenomenological appeal: a person does anything and everything he or she does only because that thing at least “appears” to be good. Even when I choose something that I know is bad for myself, I nevertheless chooses it under some aspect of good, i.e., as some kind of good. I know the cake is fattening, for example, and I don’t choose to eat it as fattening. I do, however, choose to eat it as tasty (which is an apparent, though not a true, good). A true good is an object of desire which reason determines to be appropriate or fitting to a given person, in certain circumstances, in light of their universal human nature ( ST I-II, 94, 3 , esp. ad 3). Sometimes this will include eating cake, but not too much of it.

Precepts of the Natural Law

The precepts of the natural law are commands derived from the inclinations or desires natural to human beings; for Aquinas there is no problem in deriving “ought” from “is.” Since the object of every desire has the character or formality of “good,” there are a variety of goods we naturally seek. They are all subsumed under the First Principle of Practical Reasoning: The good is to be done and pursued, and evil avoided. This first principle is operative in all the precepts that comprise the natural law. Subsequent precepts of the natural law derive first from various sorts of inclinations as humans share these with other sorts of natural things, and second, as one discovers these goods in greater specificity ( ST I-II, 94, 2 ).

On the level that we share with all substances, the natural law commands that we preserve ourselves in being. Therefore, one of the most basic precepts of the natural law is to not commit suicide. (Nevertheless, suicide can, sadly, be chosen as an apparent good, e.g., as the cessation of pain; often it is not chosen at all, but the result of mental illness.) On the level we share with all living things, the natural law commands that we take care of our life, and transmit that life to the next generation. Thus, almost as basic as the preservation of our lives, the natural law commands us to rear and care for offspring. On the level that is most specific to humans, the fulfillment of the natural law consists in the exercise those activities that are unique and proper to humans, i.e., knowledge and love , and in a state that is also natural to human persons, i.e., society. The natural law, thus, commands us to develop our rational and moral capacities by growing in the virtues of intellect (prudence, art, and science ) and will ( justice , courage, temperance) ( ST I-II, 94, 3 ). Natural law also commands those things that make for the harmonious functioning of society (“Thou shalt not kill,” “Thou shalt not steal”). Human nature also shows that each of us have a destiny beyond this world, too. Man’s infinite capacity to know and love shows that he is destined to know and love an infinite being, God, and so, natural law commands the practice of religion.

All of these levels of precepts so far outlined are only the most basic. “The good is to be done and pursued and evil is to be avoided” is not very helpful for making actual choices. Therefore, Aquinas believes that one needs one’s reason to be perfected by the virtues , especially prudence, in order to discover precepts of the natural law that are more proximate to the choices that one has to make on a day-to-day basis. As is indicated in the table above, particular precepts, as they derive from more general ones in issuing forth in action, can conflict with each other. The command to save David might conflict with the apparent injunction that one ought not to lie to soldiers bent on unjustly executing him, but might cohere with the injunction not to give them information they have no just right to. Applying the natural law to cases, then, is more open to error, even though the general principles are true and apparent, and there is, in fact, a true and most rational application to certain particular circumstances ( ST I-II, 94, 3 ).

Application of the Natural Law as an Absolute / Objective Standard

Given that the natural law depends on the inclinations inherent in human nature (as ordained by the intelligent, loving providence of God, i.e., the Eternal Law) it applies to all people, at all times. Yet Aquinas readily acknowledges that the laws and morals of people can vary wildly. Rather than succumbing to moral relativism (where what is morally good and right is merely what each society or person thinks is such), Aquinas seeks both to uphold the objective and universal basis of morality in the natural law, and to explain the variety of moral and legal injunctions. Despite his belief that the natural law applies universally, Aquinas explains how this variety arises, first from the perspective of the generality of the precepts, and then from the perspective of the knowledge an individual has of the precepts.

From the perspective of the generality of the precepts, Aquinas reasons that the more general a precept is, the less is it open to exceptions. The general principles of both speculative reasoning (e.g., mathematics and the sciences) and practical reasoning (arts, ethics and politics) are necessary, and so the primary precepts of the natural law apply in all cases. The good is always to be done; life is always to be preserved. Yet, as one seeks to apply the general principles to particular cases, the particular circumstances necessitate greater variety in the kinds of actions required by the principle. Preserving life in the community may require the execution of murderers .

Although there is necessity in the general principles, the more we descend to matters of detail, the more frequently we encounter defects. … In matters of action, truth or practical rectitude is not the same for all, as to matters of detail, but only as to the general principles: and where there is the same rectitude in matters of detail, it is not equally known to all . ( ST I-II, 94, 4 )

From the perspective of the knowledge an of individual, the variety of ways of applying the natural law also leads to variability in knowing how to so apply the principles. The more general a precept is, the more likely it is to be known by a greater number of people. The more particular a precept of the natural law (or the application of a general precept to a particular case) is, the more likely it is that a particular individual will get it wrong.

Aquinas thus concludes that the greater the detail, the more likely it will be that people disagree about what the natural law requires:

Consequently, we must say that the natural law, as to general principles, is the same for all, both as to rectitude and as to knowledge. But as to certain matters of detail, which are conclusions, as it were, of those general principles, it is the same for all in the majority of cases, both as to rectitude and as to knowledge; and yet in some few cases it may fail, both as to rectitude, by reason of certain obstacles (just as natures subject to generation and corruption fail in some few cases on account of some obstacle), and as to knowledge, since in some the reason is perverted by passion, or evil habit, or an evil disposition of nature. ( ST I-II, 94, 4 )

Even though it is true that as one makes more particular applications of the general precepts of the natural law, the form that application takes is likely to be displayed in a greater variety of actions, nevertheless, the same natural law is being applied in each case, and the same natural law commands a variety of actions as given situations demand. What is the right thing to do might vary according to a variety of circumstances, yet in each case, the right thing to do is objective and necessary, a rational deduction of the certain general principles of moral action.

Just and Unjust Laws

Aquinas thus argues that the natural law cannot be changed, except by way of addition. Such additions, he says, are “things for the benefit of human life [which] have been added over and above the natural law, both by Divine law and by human laws ” ( ST I-II, 94, 5 ). Nothing can be subtracted from the natural law with regard to the primary precepts, and thus, no human law which commands something contrary to the natural law can be just. Interestingly, he notes, that certain features of society, while not being provided to humans by nature, accord with the natural law under the general principle of being “devised by human reason for the benefit of human life” ( ad 3 ). He includes among such non-natural features as consonant with natural law: clothing, private property and slavery. Yet by introducing the condition that just additions to the natural law must be for the benefit of human life, he allows, as we’ll see below, that should they fail this condition, they would thereby be subtractions from the natural law and so, unjust.

Given the universality and objective character of the natural law, Aquinas unsurprisingly asserts that it cannot be forgotten or “abolished from the human heart” ( ST I-II, 94, 6 ). Nevertheless, he recognizes that many people act as though they do not recognize this universal and objective standard of morality since they are inhibited by the influence of concupiscence or other passions , by an error of reasoning , or “by vicious customs and corrupt habits.” Indeed, as the third objection notes, there are whole societies which operate according to laws at variance with the natural law, declaring their departures as “just.” Aquinas responds that such laws abolish only the “secondary precepts of the natural law, against which some legislators have framed certain enactments which are unjust.” ( ST 94, 6 ad 3 ). This nuanced understanding of the natural law, then, provides a standard for judging just and unjust laws. He makes this criterion of just laws explicit when he turns to the origin of human law.

Consequently, every human law has just so much of the nature of law, as it is derived from the law of nature. But if in any point it deflects from the law of nature, it is no longer a law but a perversion of law.” ( ST I-II, 95, 2 )

Aquinas, thus, seems to grant that whatever judges a system of human laws must stand outside and above that system. The laws of Nazi Germany which prescribed the execution of Jews and dissidents and forbade their protection constituted “crimes against humanity,” not because these laws were in violation of other laws of Germany, or the laws of France or the United States. The reason that the attempted destruction of the Jews was wrong was not even because the whole rest of the world thought it was wrong. The crimes of Nazi Germany could be judged as crimes because they were violations of a law that stands apart from and above the laws of every nation; they were violations of the natural law. Natural law, then, serves as the standard against which we determine whether human positive laws are just or not.

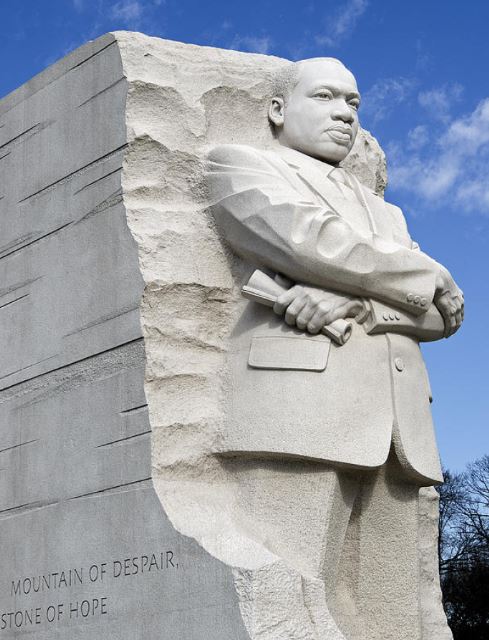

One can see these principles at work in “ Letter from Birmingham City Jail ” by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. As King says:

I would be the first to advocate obeying just laws. One has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws. I would agree with St. Augustine that “an unjust law is no law at all.” Now, what is the difference between the two? How does one determine whether a law is just or unjust? A just law is a man made code that squares with the moral law or the law of God. An unjust law is a code that is out of harmony with the moral law. To put it in the terms of St. Thomas Aquinas: An unjust law is a human law that is not rooted in eternal law and natural law. Any law that uplifts human personality is just. Any law that degrades human personality is unjust. All segregation statutes are unjust because segregation distorts the soul and damages the personality. It gives the segregator a false sense of superiority and the segregated a false sense of inferiority.

The justification to which King appeals in order to show that segregation laws are unjust is not other laws of Alabama or of the United States, but the natural law as it is founded in human nature. Human nature demands a true sense of equality and dignity, and because segregation laws violate that equality and dignity, they are unjust. Segregation laws clearly diminished the dignity, and thus damage the personality of blacks in Alabama. Interestingly, King asserts that segregation laws were harmful to the white majority, distorting their proper dignity and damaging their personality as well. In both cases, segregation laws are an affront to human dignity, founded as it is in our common human nature.

The Thomistic notion of natural law has its roots, then, in a quite basic understanding of the universe as caused and cared for by God, and the basic notion of what a law is. It is a fairly sophisticated notion by which to ground the legitimacy of human law in something more universal than the mere agreement and decree of legislators. Yet, it allows that what the natural law commands or allows is not perfectly obvious when one gets to the proximate level of commanding or forbidding specific acts. It grounds the notion that there are some things that are wrong, always and everywhere, i.e., “crimes against humanity,” while avoiding the obvious difficulties of claiming that this is determined by any sort of human consensus. Nevertheless, it still sees the interplay of people in social and rational discourse as necessary to determine what in particular the natural law requires.

Updated February 24, 2024

Revised and expanded August 26, 2021

Please support the Thomistic Philosophy Page with a gift of any amount.

Share this:.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

COMMENTS

The theory of Natural Law was put forward by Aristotle but championed by Aquinas (1225-74).  It is a deductive theory - it starts with basic principles, and from these the right course of action in a particular situation can be deduced.  It is deontological, looking at the intent behind an action and the nature of the act itself, not its outcomes.

Introduction Natural law ethics is based on Aristotelian teleology; the idea that everything has a nature which directs it towards its good end goal. Aquinas Christianised this concept. The Christian God designed everything with a telos according to his omnibenevolent plan for creation. Christian ethics is most associated with the commands and precepts found in…

Natural Law For centuries the dominant philosophical thought on the issue of natural law was dominated by the Catholic Church's theocracy (Gula, 1989). Natural law is the idea that law exists that is set by nature and that therefore it is universally validity (Cochrane, 1857). The first great philosopher to establish the early views on natural law was St. Augustine.

Essays on Natural Law. Essay examples. Essay topics. 7 essay samples found. Sort & filter. 1 Natural Law by Thomas Aquinas: an Examination . 1 page / 514 words . Explain Aquinas' Natural Law theory Thomas Aquinas was a 13th century monk who studied Aristotle's philosophy. He developed his Natural Law from these studies.

Natural law is a theory asserting that certain natural rights or values are inherent by virtue of human nature and can be universally understood through human reason (Coyle, 2023). Rooted deeply in various religious and ... Cite this Article in your Essay (APA Style) Drew, C. (August 2, 2023). 15 Natural Law Examples. Helpful Professor. https ...

Natural law, according to Nobles and Schiff, can be described as the 'application of ethical or political theories to the question of how legal orders can acquire, or have legitimacy'. Natural law is primarily a theory on morality or ethics and is not a legal theory. Law is just another aspect of society which natural law looks at.

Explain Aquinas' Natural Law theory. Thomas Aquinas was a 13th century monk who studied Aristotle's philosophy. He developed his Natural Law from these studies. Natural law is an absolute, deontological theory which states that morals are issued by God to nature.

Natural law theory holds that all human conduct is governed by an inherited set of universal moral rules. These rules apply to everyone, everywhere, in the same way. As a philosophy, natural law deals with moral questions of "right vs. wrong," and assumes that all people want to live "good and innocent" lives.

Natural Law Essay. Sort By: Page 1 of 50 - About 500 essays. Better Essays. Natural Law And Human Law. 1515 Words; 7 Pages; Natural Law And Human Law 'An unjust law cannot be a valid law' In the light of Natural Law and Positivist theories, assess the accuracy of the above statement. Intro Natural law Natural Law Theory seeks to explain ...

The natural law is properly applied to the case of human beings, and acquires greater precision because of the fact that we have reason and free will. It is our nature as humans to act freely (i.e., to be provident for ourselves and others) by directing ourselves toward our proper acts and end. That is, we human beings must exercise our natural ...