- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Drug addiction (substance use disorder)

Diagnosing drug addiction (substance use disorder) requires a thorough evaluation and often includes an assessment by a psychiatrist, a psychologist, or a licensed alcohol and drug counselor. Blood, urine or other lab tests are used to assess drug use, but they're not a diagnostic test for addiction. However, these tests may be used for monitoring treatment and recovery.

For diagnosis of a substance use disorder, most mental health professionals use criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), published by the American Psychiatric Association.

- Care at Mayo Clinic

Our caring team of Mayo Clinic experts can help you with your drug addiction (substance use disorder)-related health concerns Start Here

Although there's no cure for drug addiction, treatment options can help you overcome an addiction and stay drug-free. Your treatment depends on the drug used and any related medical or mental health disorders you may have. Long-term follow-up is important to prevent relapse.

Treatment programs

Treatment programs for substance use disorder usually offer:

- Individual, group or family therapy sessions

- A focus on understanding the nature of addiction, becoming drug-free and preventing relapse

- Levels of care and settings that vary depending on your needs, such as outpatient, residential and inpatient programs

Withdrawal therapy

The goal of detoxification, also called "detox" or withdrawal therapy, is to enable you to stop taking the addicting drug as quickly and safely as possible. For some people, it may be safe to undergo withdrawal therapy on an outpatient basis. Others may need admission to a hospital or a residential treatment center.

Withdrawal from different categories of drugs — such as depressants, stimulants or opioids — produces different side effects and requires different approaches. Detox may involve gradually reducing the dose of the drug or temporarily substituting other substances, such as methadone, buprenorphine, or a combination of buprenorphine and naloxone.

Opioid overdose

In an opioid overdose, a medicine called naloxone can be given by emergency responders, or in some states, by anyone who witnesses an overdose. Naloxone temporarily reverses the effects of opioid drugs.

While naloxone has been on the market for years, a nasal spray (Narcan, Kloxxado) and an injectable form are now available, though they can be very expensive. Whatever the method of delivery, seek immediate medical care after using naloxone.

Medicine as part of treatment

After discussion with you, your health care provider may recommend medicine as part of your treatment for opioid addiction. Medicines don't cure your opioid addiction, but they can help in your recovery. These medicines can reduce your craving for opioids and may help you avoid relapse. Medicine treatment options for opioid addiction may include buprenorphine, methadone, naltrexone, and a combination of buprenorphine and naloxone.

Behavior therapy

As part of a drug treatment program, behavior therapy — a form of psychotherapy — can be done by a psychologist or psychiatrist, or you may receive counseling from a licensed alcohol and drug counselor. Therapy and counseling may be done with an individual, a family or a group. The therapist or counselor can:

- Help you develop ways to cope with your drug cravings

- Suggest strategies to avoid drugs and prevent relapse

- Offer suggestions on how to deal with a relapse if it occurs

- Talk about issues regarding your job, legal problems, and relationships with family and friends

- Include family members to help them develop better communication skills and be supportive

- Address other mental health conditions

Self-help groups

Many, though not all, self-help support groups use the 12-step model first developed by Alcoholics Anonymous. Self-help support groups, such as Narcotics Anonymous, help people who are addicted to drugs.

The self-help support group message is that addiction is an ongoing disorder with a danger of relapse. Self-help support groups can decrease the sense of shame and isolation that can lead to relapse.

Your therapist or licensed counselor can help you locate a self-help support group. You may also find support groups in your community or on the internet.

Ongoing treatment

Even after you've completed initial treatment, ongoing treatment and support can help prevent a relapse. Follow-up care can include periodic appointments with your counselor, continuing in a self-help program or attending a regular group session. Seek help right away if you relapse.

More Information

Drug addiction (substance use disorder) care at Mayo Clinic

- Cognitive behavioral therapy

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies testing new treatments, interventions and tests as a means to prevent, detect, treat or manage this condition.

Coping and support

Overcoming an addiction and staying drug-free require a persistent effort. Learning new coping skills and knowing where to find help are essential. Taking these actions can help:

- See a licensed therapist or licensed drug and alcohol counselor. Drug addiction is linked to many problems that may be helped with therapy or counseling, including other underlying mental health concerns or marriage or family problems. Seeing a psychiatrist, psychologist or licensed counselor may help you regain your peace of mind and mend your relationships.

- Seek treatment for other mental health disorders. People with other mental health problems, such as depression, are more likely to become addicted to drugs. Seek immediate treatment from a qualified mental health professional if you have any signs or symptoms of mental health problems.

- Join a support group. Support groups, such as Narcotics Anonymous or Alcoholics Anonymous, can be very effective in coping with addiction. Compassion, understanding and shared experiences can help you break your addiction and stay drug-free.

Preparing for your appointment

It may help to get an independent perspective from someone you trust and who knows you well. You can start by discussing your substance use with your primary care provider. Or ask for a referral to a specialist in drug addiction, such as a licensed alcohol and drug counselor, or a psychiatrist or psychologist. Take a relative or friend along.

Here's some information to help you get ready for your appointment.

What you can do

Before your appointment, be prepared:

- Be honest about your drug use. When you engage in unhealthy drug use, it can be easy to downplay or underestimate how much you use and your level of addiction. To get an accurate idea of which treatment may help, be honest with your health care provider or mental health provider.

- Make a list of all medicines, vitamins, herbs or other supplements that you're taking, and the dosages. Tell your health care provider and mental health provider about any legal or illegal drugs you're using.

- Make a list of questions to ask your health care provider or mental health provider.

Some questions to ask your provider may include:

- What's the best approach to my drug addiction?

- Should I see a psychiatrist or other mental health professional?

- Will I need to go to the hospital or spend time as an inpatient or outpatient at a recovery clinic?

- What are the alternatives to the primary approach that you're suggesting?

- Are there any brochures or other printed material that I can have? What websites do you recommend?

Don't hesitate to ask other questions during your appointment.

What to expect from your doctor

Your provider is likely to ask you several questions, such as:

- What drugs do you use?

- When did your drug use first start?

- How often do you use drugs?

- When you take a drug, how much do you use?

- Do you ever feel that you might have a problem with drugs?

- Have you tried to quit on your own? What happened when you did?

- If you tried to quit, did you have withdrawal symptoms?

- Have any family members criticized your drug use?

- Are you ready to get the treatment needed for your drug addiction?

Be ready to answer questions so you'll have more time to go over any points you want to focus on.

- Substance-related and addictive disorders. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-5. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. https://dsm.psychiatryonline.org. Accessed Aug. 15, 2022.

- Brown AY. Allscripts EPSi. Mayo Clinic. April 13, 2021.

- DrugFacts: Understanding drug use and addiction. National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/understanding-drug-use-addiction. Accessed Aug. 15, 2022.

- American Psychiatric Association. What is a substance use disorder? https://psychiatry.org/patients-families/addiction-substance-use-disorders/what-is-a-substance-use-disorder. Accessed Sept. 2, 2022.

- Eddie D, et al. Lived experience in new models of care for substance use disorder: A systematic review of peer recovery support services and recovery coaching. Frontiers in Psychology. 2019; doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01052.

- Commonly used drugs charts. National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://www.drugabuse.gov/drug-topics/commonly-used-drugs-charts. Accessed Aug. 16, 2022.

- Drugs, brains, and behavior: The science of addiction. National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugs-brains-behavior-science-addiction/drug-misuse-addiction. Accessed Aug. 16, 2022.

- Drugs of abuse: A DEA resource guide/2020 edition. United States Drug Enforcement Administration. https://admin.dea.gov/documents/2020/2020-04/2020-04-13/drugs-abuse. Accessed Aug. 31, 2022.

- Misuse of prescription drugs research report. National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/misuse-prescription-drugs/overview. Accessed Aug. 17, 2022.

- Principles of drug addiction treatment: A research-based guide. 3rd ed. National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/principles-drug-addiction-treatment-research-based-guide-third-edition/preface. Accessed Aug. 17, 2022.

- The science of drug use: A resource for the justice sector. National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://nida.nih.gov/drug-topics/criminal-justice/science-drug-use-resource-justice-sector. Accessed Sept. 2, 2022.

- Naloxone DrugFacts. National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugfacts/naloxone. Accessed Aug. 31, 2022.

- Drug and substance use in adolescents. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/pediatrics/problems-in-adolescents/drug-and-substance-use-in-adolescents. Accessed Sept. 2, 2022.

- DrugFacts: Synthetic cannabinoids (K2/Spice). National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/synthetic-cannabinoids-k2spice. Accessed Aug. 18, 2022.

- Hall-Flavin DK (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. March 5, 2021.

- Poppy seed tea: Beneficial or dangerous?

Associated Procedures

News from mayo clinic.

- Science Saturday: Preclinical research identifies brain circuit connected to addictive behaviors July 22, 2023, 11:00 a.m. CDT

- What is naloxone and should everyone have access to it? Feb. 16, 2023, 05:06 p.m. CDT

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

- Introduction

- Conclusions

- Article Information

BH indicates behavioral health; CE, continuing education; BH IOP, intensive behavioral health (intensive outpatient or partial hospitalization); IP detox/RTC, inpatient detoxification or residential services; and MOUD, medication for opioid use disorder.

CE indicates continuing education; MOUD, medication for opioid use disorder.

eAppendix 1. Cohort Selection

eAppendix 2. Supplementary Methods

eFigure 1. Definition of OUD

eFigure 2. Cohort Inclusion and Timeline

eFigure 3. Alluvial Flow of OUD Treatment Pathways in the Initial Cohort

eTable. Censoring by Baseline Characteristics

See More About

Sign up for emails based on your interests, select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Get the latest research based on your areas of interest.

Others also liked.

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Wakeman SE , Larochelle MR , Ameli O, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Different Treatment Pathways for Opioid Use Disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1920622. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Comparative Effectiveness of Different Treatment Pathways for Opioid Use Disorder

- 1 Division of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

- 2 Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts

- 3 Clinical Addiction Research and Education Unit, Boston Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts

- 4 Department of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts

- 5 Integrated Programs, OptumLabs Inc, Cambridge, Massachusetts

- 6 Department of Research, OptumLabs, Minnetonka, Minnesota

- 7 Department of Research, OptumLabs, Cambridge, Massachusetts

- 8 Department of Research, Optum Behavioral Health, Cambridge, Massachusetts

- 9 Department of Medicare and Retirement, United Healthcare, Minnetonka, Minnesota

Question What is the real-world effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder?

Findings In this comparative effectiveness research study of 40 885 adults with opioid use disorder that compared 6 different treatment pathways, only treatment with buprenorphine or methadone was associated with reduced risk of overdose and serious opioid-related acute care use compared with no treatment during 3 and 12 months of follow-up.

Meaning Methadone and buprenorphine were associated with reduced overdose and opioid-related morbidity compared with opioid antagonist therapy, inpatient treatment, or intensive outpatient behavioral interventions and may be used as first-line treatments for opioid use disorder.

Importance Although clinical trials demonstrate the superior effectiveness of medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) compared with nonpharmacologic treatment, national data on the comparative effectiveness of real-world treatment pathways are lacking.

Objective To examine associations between opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment pathways and overdose and opioid-related acute care use as proxies for OUD recurrence.

Design, Setting, and Participants This retrospective comparative effectiveness research study assessed deidentified claims from the OptumLabs Data Warehouse from individuals aged 16 years or older with OUD and commercial or Medicare Advantage coverage. Opioid use disorder was identified based on 1 or more inpatient or 2 or more outpatient claims for OUD diagnosis codes within 3 months of each other; 1 or more claims for OUD plus diagnosis codes for opioid-related overdose, injection-related infection, or inpatient detoxification or residential services; or MOUD claims between January 1, 2015, and September 30, 2017. Data analysis was performed from April 1, 2018, to June 30, 2019.

Exposures One of 6 mutually exclusive treatment pathways, including (1) no treatment, (2) inpatient detoxification or residential services, (3) intensive behavioral health, (4) buprenorphine or methadone, (5) naltrexone, and (6) nonintensive behavioral health.

Main Outcomes and Measures Opioid-related overdose or serious acute care use during 3 and 12 months after initial treatment.

Results A total of 40 885 individuals with OUD (mean [SD] age, 47.73 [17.25] years; 22 172 [54.2%] male; 30 332 [74.2%] white) were identified. For OUD treatment, 24 258 (59.3%) received nonintensive behavioral health, 6455 (15.8%) received inpatient detoxification or residential services, 5123 (12.5%) received MOUD treatment with buprenorphine or methadone, 1970 (4.8%) received intensive behavioral health, and 963 (2.4%) received MOUD treatment with naltrexone. During 3-month follow-up, 707 participants (1.7%) experienced an overdose, and 773 (1.9%) had serious opioid-related acute care use. Only treatment with buprenorphine or methadone was associated with a reduced risk of overdose during 3-month (adjusted hazard ratio [AHR], 0.24; 95% CI, 0.14-0.41) and 12-month (AHR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.31-0.55) follow-up. Treatment with buprenorphine or methadone was also associated with reduction in serious opioid-related acute care use during 3-month (AHR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.47-0.99) and 12-month (AHR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.58-0.95) follow-up.

Conclusions and Relevance Treatment with buprenorphine or methadone was associated with reductions in overdose and serious opioid-related acute care use compared with other treatments. Strategies to address the underuse of MOUD are needed.

The increasing burden of opioid use disorder (OUD) has resulted in increased opioid-related morbidity and mortality, with 47 600 overdose deaths in 2017 alone. 1 - 3 From 2002 to 2012, hospitalization costs attributable to opioid-related overdose increased by more than $700 million annually. 4 Associated health complications, such as hepatitis C infection, HIV infection, and serious injection-related infections, are also increasing. 5 - 7 In addition, as rates of opioid-related death have increased despite decreases in prescription opioid supply, there is an increasing recognition that greater attention must be paid to improving access to effective OUD treatment. 8 , 9

Medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) is effective and improves mortality, treatment retention, and remission, but most people with OUD remain untreated. 10 - 15 Many parts of the United States lack access to buprenorphine prescribers, and only a few addiction treatment programs offer all forms of MOUD. 16 - 18 This lack of access has resulted in a treatment gap of an estimated 1 million people with OUD untreated with MOUD annually. 19

Nationally representative, comparative effectiveness studies of MOUD compared with nonpharmacologic treatment are limited. One prior study 12 compared MOUD with psychosocial treatments but was limited to a Massachusetts Medicaid population. Studies 20 - 23 examining OUD treatment among nationally representative populations have examined trends in MOUD initiation, patterns of OUD treatment, and effectiveness of different types of MOUD at reducing overdose using Medicaid and commercial claims data. However, none of those studies 20 - 23 compared the effectiveness of MOUD with nonpharmacologic treatments in a national sample. Despite better access to medical care, only a few commercially insured patients are treated with MOUD, and psychosocial-only treatments continue to be common, suggesting that greater understanding of the comparative effectiveness of these different treatments is needed. 21

In this study, we used a large, nationally representative database of commercially insured and Medicare Advantage (MA) individuals to evaluate the effectiveness of MOUD compared with nonpharmacologic treatment. This retrospective comparative effectiveness study was designed to inform treatment decisions made by policy makers, insurers, practitioners, and patients.

We conducted a comparative effectiveness research study using the OptumLabs Data Warehouse, which includes medical, behavioral health, and pharmacy claims for commercial and MA enrollees. 24 The database represents a diverse mixture of ages, races/ethnicities, and geographic regions across the United States. Our analysis used deidentified administrative claims data. The window for identification of OUD for this study was January 1, 2015, to September 30, 2017. The study used claims data from October 3, 2014, to December 31, 2017, to allow for a 90-day period to ensure a nonopioid clean period and a minimum of 90 days of follow-up for all individuals with diagnosed OUD. Data analysis was performed from April 1, 2018, to June 30, 2019. Because this study involved analysis of preexisting, deidentified data, the Chesapeake Institutional Review Board deemed it exempt from institutional review board approval. This study followed the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research ( ISPOR ) reporting guideline. 25

We defined OUD as 1 or more inpatient or 2 or more outpatient claims for International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) or International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis codes for opioid dependence that occurred within 3 months of each other; 1 or more claims for diagnosis codes for opioid dependence, opioid use, or opioid abuse plus diagnosis codes for an encounter related to opioid overdose or an injection-related infection, opioid-related inpatient detoxification or residential services; or claims for MOUD or detoxification (eFigure 1 in the Supplement ). Cohort inclusion required presence of OUD and age of 16 years or older; commercial or MA medical, pharmacy, and behavioral coverage; and continuous enrollment for 3 months before and after OUD treatment initiation date. For those in the no treatment group, a treatment initiation index date was selected at random that matched the treated groups (eAppendix 1 in the Supplement ).

We examined treatments received in the 3 months after OUD diagnosis during the first 90 days after cohort entry to identify patterns of treatment (eFigure 2 in the Supplement ). We categorized individuals into 1 of 6 mutually exclusive pathway designations based on initial treatment: (1) no treatment, (2) inpatient detoxification or residential services, (3) intensive behavioral health (intensive outpatient or partial hospitalization), (4) buprenorphine or methadone, (5) naltrexone, and (6) only nonintensive behavioral health (outpatient counseling) (eAppendix 2 in the Supplement ). In addition, we examined mean duration of MOUD treatment in days.

Classification of treatment pathways was informed by detailed exploration of the sequence of treatment modalities provided to patients using medical and pharmacy claims (eFigure 3 in the Supplement ). For this study, consistent with an intent-to-treat design, patients were assigned to the initial treatment received.

Our primary outcomes were overdose or serious opioid-related acute care use, defined as an emergency department or hospitalization with a primary opioid diagnosis code. Overdose was identified based on diagnosis codes from claims for health care encounters. These encounters may include both fatal and nonfatal overdose (lack of mortality data preclude that determination). For actively treated individuals, the index date was the date of first treatment. For untreated individuals, the index date was set randomly based on the distribution of time to first treatment among actively treated individuals. Risk for adverse outcomes started 1 day after the index date; however, because the time sequence for adverse events that occurred during an initial inpatient treatment could not be reliably established, risk of adverse outcomes started 1 day after inpatient discharge. Time to event was calculated as (event date – index date + 1), which is consistent with an intent-to-treat analysis for all treatment pathways. Individuals were censored at the earlier outcome, health plan disenrollment, or 12 months. We selected overdose and opioid-related acute care use as negative clinical outcomes, which likely indicate recurrence of OUD. These outcomes may underestimate the prevalence of OUD recurrence because they represent severe consequences of ongoing use.

A secondary outcome was admission to inpatient detoxification or readmission for those who initiated treatment with inpatient detoxification or residential services. All outcomes were evaluated for 3 months and 12 months after treatment initiation. In the absence of an event, patients were followed up until the earliest date of health plan disenrollment or end of the respective period.

We used Cox proportional hazards regression models to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) for primary and secondary outcomes, adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, insurance type, baseline cost rank, mental health and medical comorbidities, and injection-related infections or overdose at study inclusion. For medical comorbidities, we used a modified Elixhauser index that excluded mental health subcomponents because they were classified separately. 26 All analyses were conducted using an intent-to-treat approach that attributed patient outcomes to their initial treatment category. We conducted a subanalysis of patients who received methadone or buprenorphine, stratifying by duration of MOUD treatment as 1 to 30 days, 31 to 180 days, or more than 180 days.

For the secondary outcome of admission to inpatient detoxification, we conducted a subanalysis in which patients in the no treatment and nonintensive behavioral health groups were removed from the sample. These 2 treatment pathways were, by definition, required to not have any treatment (no treatment group) or any treatment other than outpatient behavioral health treatment (nonintensive behavioral health group) in the first 3 months of follow-up, which made them systematically different from the other pathways evaluated for this outcome.

Analysis of survival for all outcomes was performed using unadjusted Kaplan-Meier curves and adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression (PHREG procedure, SAS Enterprise Guide, version 7.13 [SAS Institute Inc]) under both 3-month and 12-month time windows to examine potential survivorship bias and informative censoring. For the unadjusted analysis, the log-rank test is reported; 95% Wald CIs are reported for the adjusted HRs (AHRs). The proportionality assumption was assessed visually and tested by including treatment pathway as a time-dependent covariate in the Cox proportional hazards regression model. Hazards appeared to be proportional during 3 months, but there was evidence of nonproportionality for the behavioral health outpatient pathway during the 12-month time window.

A total of 40 885 individuals with OUD (mean [SD] age, 47.73 [17.25] years; 22 172 [54.2%] male; 30 332 [74.2%] white) were identified. A total of 23 636 (57.8%) were commercially insured, and 17 249 (42.2%) were enrolled in MA plans. Of those with MA, 10 322 (25.2%) were younger than 65 years. Non–substance use disorder mental health comorbidities in the 3 months before the index date were found in 10 942 individuals (45.1%) in the cohort. Depression (9733 [23.8%]) and anxiety (10 704 [26.2%]) were most common ( Table 1 ).

The most common treatment pathway was nonintensive behavioral health (24 258 [59.3%]), followed by inpatient detoxification or residential services (6455 [15.8%]) and buprenorphine or methadone (5123 [12.5%]). Not receiving any treatment was more common (2116 [5.2%]) than naltrexone (963 [2.4%]) or intensive behavioral health (1970 [4.8%]). Mean (SD) length of stay in inpatient detoxification or residential services was 7.47 (10.35) days. For the 5048 in that group who had at least 6 months of continuous enrollment, mean (SD) length of stay was 7.56 (10.99) days. For the 3098 in that group who had at least 12 months of continuous enrollment, mean (SD) length of stay was 7.64 (12.24) days.

Maintaining continuous commercial health insurance was challenging in this cohort; 19 685 (48.1%) were disenrolled by 12 months after the index date. Individuals receiving nonintensive behavioral health had the lowest disenrollment (11 037 [45.5%]), and those receiving MOUD treatment with buprenorphine or methadone (2755 [53.8%]) and MOUD treatment with naltrexone (520 [54.0%]) had the highest disenrollment rates. No differences were found between those who maintained enrollment and those who were disenrolled with regard to race/ethnicity, comorbidities, or markers of severity of OUD, including those with a history of an injection-related infection, hepatitis C infection, or overdose. It was not possible to distinguish disenrollment attributable to death from disenrollment for other reasons (eg, health insurance options offered by employers). Details on demographic characteristics and comorbidities by treatment group for individuals who were disenrolled are provided in the eTable in the Supplement .

During the 3-month follow-up period, 707 participants (1.7%) experienced an overdose, and 773 (1.9%) had a serious opioid-related acute care use episode. Only individuals receiving MOUD treatment with buprenorphine or methadone were less likely to experience an overdose compared with those receiving no treatment (AHR, 0.24; 95% CI, 0.14-0.41) ( Table 2 and Figure 1 A). Inpatient detoxification or residential services (AHR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.57-1.19), naltrexone (AHR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.29-1.20), nonintensive behavioral health services (AHR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.67-1.27), or intensive behavioral health services (AHR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.50-1.32) were not significantly associated with overdose.

MOUD treatment with buprenorphine or methadone was also protective against serious opioid-related acute care use during the 3-month follow-up period (AHR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.47-0.99) ( Table 2 and Figure 1 B). Inpatient detoxification or residential services treatment, naltrexone, and intensive behavioral health services were not significantly associated with serious opioid-related acute care use during 3 months (inpatient detoxification or residential services: AHR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.76-1.45; naltrexone: AHR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.69-1.92; intensive behavioral health: AHR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.54-1.30). Nonintensive behavioral health services were associated with a reduction in serious opioid-related acute care use (AHR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.44-0.80). Receiving MOUD treatment with buprenorphine or methadone continued to be protective against overdose (AHR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.31-0.55) and serious opioid-related acute care use (AHR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.58-0.95) at 12 months.

Compared with MOUD treatment with buprenorphine or methadone, all treatment groups were more likely to have a posttreatment admission to inpatient detoxification. Patients who initiated treatment with inpatient detoxification or residential services were most likely to return within 3 months (AHR, 3.76; 95% CI, 2.98-4.74) and 12 months (AHR, 3.48; 95% CI, 3.02-4.01). However, treatment with naltrexone or intensive behavioral health services was also associated with a higher risk of subsequent detoxification admission during the 3-month (naltrexone: AHR, 2.64; 95% CI, 1.84-3.78; intensive behavioral health: AHR, 2.19; 95% CI, 1.63-2.96) and 12-month (naltrexone: AHR, 1.98; 95% CI, 1.55-2.52; intensive behavioral health: AHR, 2.08; 95% CI, 1.73-2.50) follow-up periods.

Treatment duration for MOUD was relatively short. During 12 months, the mean (SD) treatment duration for naltrexone was 74.41 (70.15) days and 149.65 (119.37) days for buprenorphine or methadone. Individuals who received longer-duration MOUD treatment with buprenorphine or methadone had lower rates of overdose ( Figure 2 A) or serious opioid-related acute care use ( Figure 2 B).

At the end of 12 months, 1198 (3.6%) of those who received no MOUD had an overdose, and 1204 (3.6%) had serious opioid-related acute care use; 105 (6.4%) of those who received MOUD treatment with buprenorphine or methadone for 1 to 30 days had an overdose, and 133 (8.2%) had serious opioid-related acute care use; 101 (3.4%) of those who received MOUD treatment with buprenorphine or methadone for 31 to 180 days had an overdose, and 148 (5.0%) had serious opioid-related acute care use; and 28 (1.1%) of those who received MOUD treatment with buprenorphine or methadone for more than 180 days had an overdose, and 69 (2.6%) had serious opioid-related acute care use.

In a national cohort of 40 885 insured individuals between 2015 and 2017, MOUD treatment with buprenorphine or methadone was associated with a 76% reduction in overdose at 3 months and a 59% reduction in overdose at 12 months. To our knowledge, this was the largest cohort of commercially insured or MA individuals with OUD studied in a real-world environment with complete medical, pharmacy, and behavioral health administrative claims.

Treatment with buprenorphine or methadone was associated with a 32% relative rate of reduction in serious opioid-related acute care use at 3 months and a 26% relative rate of reduction at 12 months compared with no treatment. In contrast, detoxification, intensive behavioral health, and naltrexone treatment were not associated with reduced overdose or serious opioid-related acute care use at 3 or 12 months.

Despite the known benefit of MOUD treatment with buprenorphine or methadone, only 12.5% initiated these evidence-based treatments. Most individuals in this cohort initiated treatment with psychosocial services alone or inpatient detoxification, both of which are less effective than MOUD. It is possible that individuals accessed public sector treatments that were not captured in our data, particularly for methadone, which was not covered by Medicare and may not have been covered without co-payment for all commercial plans during this time. Low rates of MOUD use among an insured population highlight the need for strategies to improve access to and coverage for MOUD treatment.

Our results demonstrate the importance of treatment retention with MOUD. Individuals who received methadone or buprenorphine for longer than 6 months experienced fewer overdose events and serious opioid-related acute care use compared with those who received shorter durations of treatment or no treatment. These findings are consistent with prior research 11 , 15 , 27 - 29 demonstrating high rates of recurrent opioid use if MOUD treatment is discontinued prematurely. Despite the benefit of MOUD in our study, treatment duration was relatively short. Given the chronic nature of OUD and the evidence that longer treatment duration may be associated with improved outcomes, patient-centered MOUD treatment models explicitly focused on engagement and retention are needed. Low-threshold treatment, which aims to reduce barriers to entry and is tailored to the needs of high-risk populations, 30 may be a strategy to improve retention; however, to our knowledge, no rigorous studies have evaluated these models to date. 31 , 32 In addition, patient-centered MOUD care, which allows participants to determine the services they need rather than requirements, such as mandatory counseling, are noninferior to traditional treatment. 32

Numerous barriers limit sustained engagement in MOUD, including a lack of access to waivered practitioners, high co-payments, prior authorization requirements, and other restrictions on use. Previous studies 33 , 34 have demonstrated that restrictions on use for MOUD are associated with limited access and harm. Addiction treatment programs in states that require Medicaid prior authorizations for buprenorphine are less likely to offer buprenorphine, and the more restrictions on use in state Medicaid programs, the fewer treatment programs that offer buprenorphine. 33 Requiring prior authorization for higher doses of buprenorphine may also result in increased recurrence rates among patients. 34 Our finding that MOUD treatment with buprenorphine or methadone was associated with lower overdose and serious opioid-related acute care use supports expanded coverage of these medications without restrictions on use.

Our findings are also consistent with analyses showing that MOUD treatment with buprenorphine or methadone is significantly associated with reduced overdose and recurrence of opioid use compared with no treatment or non-MOUD treatment. A previous cohort study 15 of individuals in Massachusetts demonstrated a reduction in overdose-related mortality associated with treatment with buprenorphine (AHR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.41-0.92) or methadone (AHR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.24-0.70), results that are similar to our finding of an AHR of 0.41 (95% CI, 0.31-0.55) for overdose at 12 months for methadone or buprenorphine. A large meta-analysis 11 examining mortality when individuals were in or out of treatment with buprenorphine or methadone similarly showed decreased overdose mortality during treatment. A study 12 examining proxies for recurrent OUD among Massachusetts Medicaid enrollees found that treatment with buprenorphine or methadone was associated with lower recurrence rates and costs. No studies, to our knowledge, have examined the effect of different OUD treatment pathways on overdose and serious opioid-related acute care use among a national sample of commercially insured and MA enrollees.

Our finding that MOUD treatment with naltrexone was not protective against overdose or serious opioid-related acute care use is consistent with other studies 15 , 35 that found naltrexone to be less effective than MOUD treatment with buprenorphine. The mean (SD) treatment duration for naltrexone in this cohort was longer than prior observational studies at 74.41 (70.15) days.

The findings that nonintensive behavioral health treatment was associated with a reduced risk of overdose at 12 months but not 3 months and a reduced risk of opioid-related acute care use was surprising. Although we attempted to control for differences among various treatment groups, individuals referred to nonintensive behavioral health may represent a less complex patient population than those who receive MOUD treatment or are referred to intensive behavioral health or inpatient treatment.

Specifically, we identified a research question a priori that was meaningful, had clinical and policy implications, and was concise and unambiguous. Our study design’s strengths are the large, nationally representative sample and complete claims data, which allowed us to adequately identify appropriate patients and interventions. In addition, we used a conservative definition of OUD and of proxies for OUD recurrence to limit inclusion of individuals who did not have OUD or of outcomes that did not represent clinically significant recurrence.

This study has limitations. The limitations of our study design include the lack of clinical information in claims data or outcomes that occurred outside a health care encounter (eg, fatal overdoses or active use without medical complication). As with any observational study, there is the possibility that unmeasured patient characteristics were associated with treatment assignment and outcomes, possibly biasing estimates of outcomes associated with MOUD treatment groups. It is also possible that individuals selected for different treatments differed by characteristics that were also associated with the outcomes. We were able to control for many patient characteristics, such as race/ethnicity, sex, insurance type, and comorbidities, but selection bias is possible. Another limitation is the degree of sample attrition during the 12-month follow-up period. However, we attempted to assess potential bias from informative censoring in 2 ways. 36 First, we compared the baseline characteristics of censored and uncensored cases. These distributions were similar, suggesting that, at least on the basis of observable characteristics, censored cases were not statistically different from uncensored cases. Second, we examined the proportionality of HRs. Visual inspection of the HRs indicated that they were proportional for the 3-month period but could not be assumed to be proportional for the 12-month period. Another limitation is the risk of immortal time bias by requiring 3-month enrollment for inclusion; however, we believed it was important to require 3 months of follow-up to adequately measure outcomes. In addition, assessment of community mortality with claims data is characterized by high degrees of measurement error. Traditional instrumental variable methods for addressing immortal time bias cannot be applied to survival models because of their nonlinear functional form.

In a national sample of commercial insurance and MA enrollees with OUD, treatment with buprenorphine or methadone was associated with reductions in overdose and serious opioid-related acute care use, but only a few individuals were treated with these medications. These findings suggest that opportunities exist for health plans to reduce restrictions on use for MOUD and the need for treatment models that prioritize access to and retention of MOUD treatment.

Accepted for Publication: December 12, 2019.

Published: February 5, 2020. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622

Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC-ND License . © 2020 Wakeman SE et al. JAMA Network Open .

Corresponding Author: Sarah E. Wakeman, MD, Division of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit St, Founders 880, Boston, MA 02114 ( [email protected] ).

Author Contributions: Drs Wakeman and Sanghavi had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: Wakeman, Larochelle, Ameli, Chaisson, Crown, Azocar, Sanghavi.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Wakeman, Larochelle, Ameli, Chaisson, McPheeters, Crown, Azocar.

Drafting of the manuscript: Wakeman, Ameli, Crown, Azocar.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Wakeman, Larochelle, Ameli, Chaisson, McPheeters, Crown, Sanghavi.

Statistical analysis: Ameli, McPheeters, Crown.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Chaisson, McPheeters, Azocar.

Supervision: Chaisson, Sanghavi.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Wakeman reported receiving personal fees from OptumLabs during the conduct of the study. Dr Ameli reported receiving grants from OptumLabs during the conduct of the study. Ms Chaisson, Mr McPheeters, and Dr Azocar reported receiving salary support from OptumLabs during the conduct of the study. Dr Azocar also reported receiving salary support from United Health Group outside the submitted work. Dr Sanghavi reported being an employee of United Health Group. No other disclosures were reported.

Funding/Support: This study was supported by grant K23DA042168 from Boston Medical Center, grant 1UL1TR001430 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, grant U01CE002780 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, grant HHSF2232009100006I from the US Food and Drug Administration, grant G1799ONDCP06B from the Office of National Drug Control Policy/University of Baltimore, a Boston University School of Medicine Department of Medicine Career Investment Award (Dr Larochelle) and by Massachusetts General Hospital, grant 1R01DA044526-01A1 from the National Institutes of Health, grant 3UG1DA015831-17S2 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, grant 1H79TI081442-01 from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and the Laura and John Arnold Foundation (Dr Wakeman).

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funding sources reviewed the manuscript but had no role in the design and conduct of the study; interpretation of the data; preparation, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Research Briefing

- Published: 29 April 2024

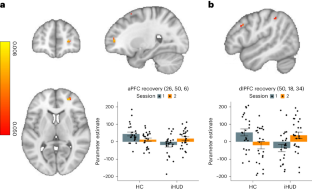

Prefrontal cortex activity increases after inpatient treatment for heroin addiction

Nature Mental Health ( 2024 ) Cite this article

53 Accesses

7 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cognitive control

Using task-based functional MRI, we examined inpatients with heroin use disorder. We found that 15 weeks of medication-assisted treatment (including supplemental group therapy) improved impaired anterior and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex function during an inhibitory control task. Inhibitory control, a core deficit in drug addiction, may be amenable to targeted prefrontal cortex interventions.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

55,14 € per year

only 4,60 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Center for Disease Control. Drug overdose deaths in the U.S. top 100,000 annually https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/nchs_press_releases/2021/20211117.htm (2021). A press release that summarizes substance-use-related overdose death statistics.

Goldstein, R. Z. & Volkow, N. D. Drug addiction and its underlying neurobiological basis: neuroimaging evidence for the involvement of the frontal cortex. Am. J. Psychiatry 159 , 1642–1652 (2002). A review article that presents core symptoms in drug addiction that are associated with PFC impairments, including excessive salience attributed to drug cues at the expense of nondrug cues and rewards with concomitant decreases in inhibitory control.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ceceli, A. O., King, S., McClain, N., Alia-Klein, N. & Goldstein, R. Z. The neural signature of impaired inhibitory control in individuals with heroin use disorder. J. Neurosci. 43 , 173–182 (2022). An empirical report in which we found worse behavioral performance and PFC hypoactivation during inhibitory control in inpatients with heroin use disorder.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Garland, E. L., Atchley, R. M., Hanley, A. W., Zubieta, J.-K. & Froeliger, B. Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement remediates hedonic dysregulation in opioid users: neural and affective evidence of target engagement. Sci. Adv. 5 , eaax1569 (2019). A study that provides neurophysiological evidence for the efficacy of Mindfulness Oriented Recovery Enhancement — one of the therapy groups that supplemented inpatient treatment in our study, with results pending trial completion — in restructuring impaired incentive salience in patients with chronic pain who misuse opiates.

Download references

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This is a summary of: Ceceli, A. O. et al. Recovery of anterior prefrontal cortex inhibitory control after 15 weeks of inpatient treatment in heroin use disorder. Nat. Ment. Health https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-024-00230-4 (2024).

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Prefrontal cortex activity increases after inpatient treatment for heroin addiction. Nat. Mental Health (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-024-00239-9

Download citation

Published : 29 April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-024-00239-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Signs of Addiction

Psychedelics as Therapeutic Treatment

Butler center for research - september 2022.

- Addiction Resources

- Addiction Journals and Abstracts

- Addiction Research Library

- About the Butler Center for Research

Introduction

Download the Psychedelics as Therapeutic Treatment Research Update.

In 2020, one in five adults in the United States experienced a mental illness; one in 15 adults experienced both a substance use disorder and mental illness. 1 Thirty-seven percent of U.S. prisoners and 44 percent of jail inmates had been told in the past by a mental health professional that they had a mental disorder. 2 The total economic burden of depression in the U.S. is estimated to be $210.5 billion per year. 3 The heavy toll that mental health conditions take on individuals, communities, and the country at large has driven the search for new options for treatment. An option gaining more attention in recent years is the use of psychedelics in treatment.

What Are Psychedelic Drugs?

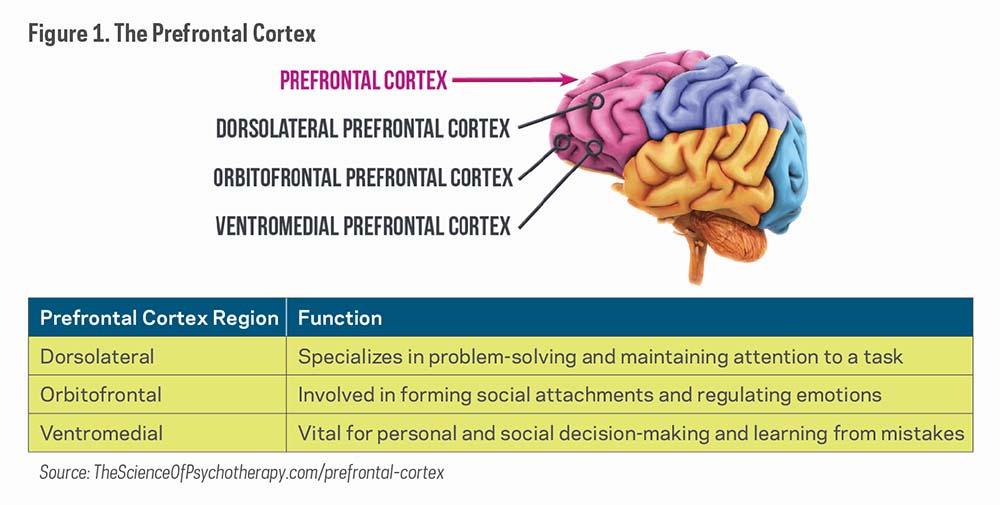

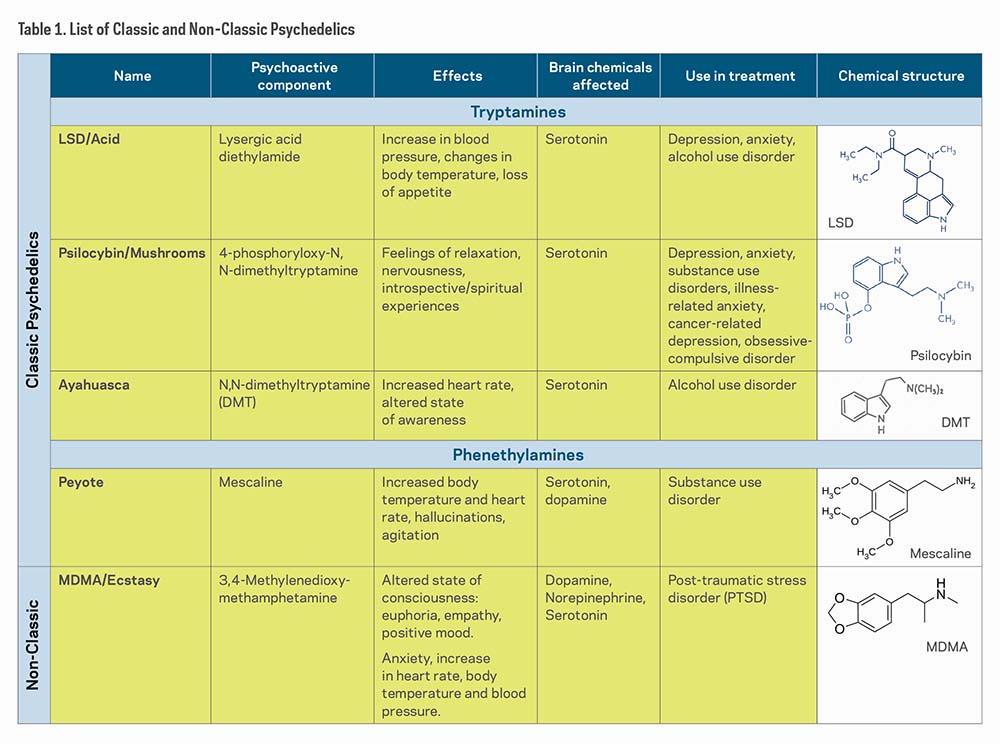

Psychedelic drugs or serotonergic hallucinogens are psychoactive substances that alter perceptions, mood, and cognitive processes. 4 They are generally considered safer than other drugs such as opioids as they are not associated with compulsive drug-seeking behaviors. 5 However, consumption of psychedelic drugs can rapidly produce a tolerance known as tachyphylaxis. 4 Some studies have noted that cross-tolerance can occur between mescaline and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), as well as psilocybin and LSD. Additionally, despite the name hallucinogens, the users' experience does not always include hallucinations. 6 Psychedelic drugs are categorized into four classes based on chemical compounds and pharmacological profile: classic psychedelics, empathogens/entactogens, dissociative anesthetic agents, and atypical hallucinogens. 5 For the sake of brevity, this research update will explore classic psychedelics and the non-classic psychedelic 3,4 Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA). Classic psychedelics act as agonists (substances that bind to and cause activation of a receptor) or partial agonists of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptors, thus earning the "serotonergic" term. The most prominent effects are produced in the prefrontal cortex of the brain, which involves mood, cognition, and perception. 7

Table 1 shows a list of "classic psychedelics," which includes LSD, Psilocybin, Ayahuasca (DMT), and Peyote (Mescaline), and one "non-classic psychedelic," MDMA/Ecstasy. Although all of these substances affect the brains' serotonin receptors, researchers have found that they affect other neural receptors and regions as well.

Brief History of the Use of Psychedelics in the Treatment of Mental Health Disorders

The use of psychedelics, particularly LSD, became more widely used by psychologists and psychiatrists in research and clinical practice during the 1950s and 1960s with studies showing supportive results regarding the use of psychedelics in the treatment of personality disorders, 8 alcohol use disorder (AUD), 9 and neurosis. 10 However, their use did not prove effective in studies focused on people living with psychosis or schizophrenia. 10 Although these studies contributed to the research of psychedelics today, the methods presented several problems including a lack of reporting of adverse outcomes, lack of control groups, and absence of statistical analyses. 10 And in 1971, Abuzzahab and Anderson reviewed 31 studies on the psychedelic treatment model on AUD with LSD. They concluded that it was difficult to reach any meaningful generalizations due to the variety of published investigations with different designs and the various criteria used to measure improvement. 11

Hallucinogenic studies were discontinued after these psychedelics were classified under Schedule I of the 1967 UN Convention on Drugs, legally defining them as having no accepted medical use and the maximum potential for harm and dependence 10 and then the initiation of the U. S. federal Controlled Substances Act, signed by President Nixon in 1970.12 Consequently, the study of psychedelic drugs became practically impossible. 10

Modern-Era Research

In the 1990s, three studies examined the effects of mescaline (Germany, 1998), DMT (ayahuasca) (United States, 1994), and psilocybin (Switzerland, 1997) on healthy individuals, which led to the revival of psychedelic studies. 10 These studies helped to establish the safety of using these psychedelic drugs on human subjects for research purposes. Additionally, in 1994, U.S. researchers conducted a randomized controlled trial to inform safe dosing of MDMA. 5 Subsequent trials conducted in the 2000s explored MDMA's effects on emotional processing, PTSD, anxiety, and social anxiety. 5 The results of the studies helped researchers identify MDMA as safe enough to use in future research. 5

Mood and Anxiety Disorders

In 2006, Moreno and colleagues recruited nine treatment resistant patients who met DSM-IV criteria for obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) for a modified double-blind study on psilocybin's treatment efficacy, tolerability and safety. 13 Participants were given up to four administrations of psilocybin separated by at least one week. Low, medium, and high doses were assigned in that order, with a very low dose inserted randomly after the first low dose. Decreases in OCD symptoms score were observed in all nine subjects at one or more of the testing sessions. 13 Limitations of the study include the small sample size and that the modified escalating dosing method may have influenced expectations in both participants and researchers. In an open-label trial (where study participants and researchers both know which treatment the patient is receiving), researchers wanted to assess the antidepressive potentials of ayahuasca. 14 Conducted in an inpatient psychiatric unit, 17 patients with recurrent major depressive disorder received one oral dose of ayahuasca. Their symptoms were assessed at baseline and again at 1, 7, 14, and 21 days post treatment. Significant decreases in scores of depression and scores of anxious-depression were observed at all points of assessment post treatment. 14 As this was not a randomized or double-blind study, and there was no placebo or other comparator group, it cannot be concluded that the observed changes were in fact caused by ayahuasca. Ayahuasca was also tested with 29 patients diagnosed with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. 15 Participants were randomized to either placebo or one dose of freeze-dried ayahuasca brew. None of the patients had any prior use of ayahuasca, and all participants were weaned off their antidepressant medications prior to drug administration. Significant antidepressant effects of ayahuasca were observed when compared with the placebo group from baseline to 7 days after dosing. 15 Although results seem promising, the number of participants was small and therefore randomized trials in larger populations are necessary. Also, the study was limited to patients with treatment-resistance depression which prevents an extension of these results to other types of depression. In a London-based open-label, uncontrolled study by Carhart-Harris and colleagues, 20 patients with moderate or severe major treatment-resistant depression each received two doses of psilocybin. 16 All participants had a history of unsuccessful treatment of no less than two different anti-depressant medications. Psilocybin was administered at a moderate dose, and one week later followed by a high dose. Marked reductions in depressive symptoms were observed for the first 5 weeks post-treatment, and results remained positive at 3 and 6 months. 16 As this was an open-label trial with no control condition, limited conclusions can be drawn about treatment efficacy. Further research utilizing double-blind randomized control trials are needed.

Substance Use Disorder

Bogenschutz and colleagues, in a proof-of-concept study, assessed the effect of psilocybin treatment in 10 patients with DSM-IV-established diagnosis of alcohol dependence. 17 Psilocybin was given at two separate occasions, first at week 4 (moderate-high dose) and again at week 8 (high dose) in addition to 12 weeks of Motivational Enhancement Therapy. The change in drinking behavior (change in percent heavy drinking days) served as the primary study outcome. Abstinence did not increase significantly in the first 4 weeks of treatment, before participants had received psilocybin, but increased significantly following psilocybin administration. 17 Limitations of this study include small sample size, lack of a control group, and lack of biological verification of alcohol use.

In another study, researchers examined the feasibility and safety of using psilocybin treatment to treat smoking dependence. 18 Fifteen nicotine-dependent smokers were included in the trial. The study consisted of a 15-week course of smoking cessation treatment. Participants attended four weekly meetings during which Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy was delivered. At week 5, participants were administered a moderate dose of psilocybin. Participants continued meeting weekly with study staff and received another dose of psilocybin at week 7 and optionally again at week 13. Changes in smoking between study intake and 6-month follow-up were examined using biomarkers and self-reports of cigarettes per day. At 6 months' follow-up, 12 of the 15 participants were abstinent, and compared to baseline, all participants showed significant reductions in self-reported daily smoking, urine cotinine, and breath carbon monoxide at this time point. 18 In a follow-up paper by the same authors, 67% (10/15) of the participants were still abstinent after 12-months (confirmed by levels of urine cotinine and breath carbon monoxide) with 9 of them abstinent at subsequent long-term follow-up (mean 30 months post-first psilocybin session). Seven of the nine reported continuous abstinence since first psilocybin session. 19 However, the small sample size and the open-label design of the original study and the follow-up paper does not allow for definitive conclusions regarding the efficacy of psilocybin.

Lastly, in 2019, Garcia-Romeu and colleagues investigated instances in which naturalistic psychedelic use led to self-reported reductions in alcohol misuse outside a formal treatment setting. 20 Researchers recruited participants for an anonymous online survey through ads posted on social media and drug discussion websites over a period of about 2 years. Participants needed to meet the following inclusion criteria: 18 years or older, fluent in English, have met DSM-5 criteria for AUD in the past and had used a classic psychedelic (outside of a university or medical setting), followed by reduction or cessation of subsequent alcohol use. The final sample size included 343 adults, predominantly White males from the U.S., whose alcohol use was assessed retrospectively before and after their use of a psychedelic. This included items rating distress related to alcohol use prior to psychedelic use, overall duration of alcohol misuse, use of medication or other AUD treatments before and after psychedelic use, age of first alcohol use, and lifetime presence of other mental health diagnoses. Participants also completed two iterations of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test–Consumption (AUDIT-C), the DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder Symptom Checklist, and the Alcohol Urge Questionnaire (AUQ). Alcohol and cannabis were the most heavily used substances, according to self-reported lifetime drug use history, and the most commonly used classic psychedelics were psilocybin or LSD. Findings indicate that after naturalistic use of psychedelics, most participants reported reduced alcohol use and the majority no longer met the criteria for AUD. 20 Participants also reported that they experienced fewer withdrawal symptoms than in previous attempts to quit drinking after their use of psychedelics. 20 Results from this study are limited due to participant self-selection, volunteer bias, and the retrospective nature of the data, which are subject to recall bias.

The Future of Psychedelics in Research

Given the mixed research findings, it is important to proceed with care and focus on scientific rigor and transparency. There is a need to better establish which of these drugs are most effective, how they should be administered, and who is most likely to benefit. New and future research efforts may benefit from exploring the underlying therapeutic mechanisms of the chemical component(s) of psychedelics in the brain. Such studies could facilitate the development of personalized medicines in the treatment of behavioral health disorders and provide needed data on potential abuse or side effects. Additionally, future studies can increase generalizability by recruiting subjects from diverse populations and expanding the sample size. As mentioned, most studies recruited relatively small samples which prevents applicability in other research settings.

Lastly, there is a need for clinical studies to improve the rigor of the research study methods. For example, additional studies utilizing double-blinded and placebo designs would improve the ability to make causal inferences from study results. Moreover, longitudinal research studies would increase our understanding of long-term use and long-term consequences associated with use of psychedelic drugs.

Finding long-lasting treatment options for mental health disorders, including addiction, is complicated and met with various challenges. Therefore, more treatment options are being explored. The use of psychedelics in treatment is getting more attention as recent research suggests efficacious treatment outcomes in specific behavioral health disorders. However, it is important to note the limitations of these studies.

Psychedelic drugs or serotonergic hallucinogens are psychoactive substances that alter perceptions, mood, and cognitive processes

How to use this information.

It is important to find long-lasting treatment options for addiction and mental health disorders. While more research is being conducted on the use of psychedelics as therapeutic treatment, it is vital to move ahead with care and to focus on the scientific rigor of the research. Current research has not found consistent evidence of effectiveness. Further clinical research is necessary to establish which psychedelic drugs are most effective, how they should be administered, and who is most likely to benefit. It is crucial for treatment providers and others to be aware of the current state of research in order to have informed conversations with their clients and provide the best care possible.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2021). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt35325/NSDUHFFRPDFWHTMLFiles2020/ 2020NSDUHFFR1PDFW102121.pdf

- Bronson, J., & Berzofsky, M. (2017). Indicators of mental health problems reported by prisoners and jail inmates, 2011–12. Bureau of Justice Statistics. bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/imhprpji1112.pdf

- Greenberg, P. E., Fournier, A-A., Sisitsky, T., Pike, C. T., & Kessler, R. C. (2015). The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 76(2), 155–162. doi.org/10.4088/JCP.14m09298

- Nichols, D. E. (2016). Psychedelics. Pharmacological Reviews, 68(2), 264–355. doi.org/10.1124/pr.115.011478

- Reiff, C. M., Richman, E. E., Nemeroff, C. B., Carpenter, L. L., Widge, A. S., Rodriguez, C. I., Kalin, N. H., McDonald, W. M., & The Work Group on Biomarkers and Novel Treatments, a Division of the American Psychiatric Association Council of Research. (2020). Psychedelics and psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 177(5), 391–410. doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19010035

- Dinis-Oliveira, R. J. (2017). Metabolism of psilocybin and psilocin: Clinical and forensic toxicological relevance. Drug Metabolism Reviews, 49(1), 84–91. doi.org/10.1080/03602532.2016.1278228

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2020). How do hallucinogens (LSD, psilocybin, peyote, DMT, and ayahuasca) affect the brain and body? nida.nih.gov/publications/research-reports/hallucinogens-dissociative -drugs/how-do-hallucinogens-lsd-psilocybin-peyote-dmt-ayahuasca-affect-brain-body

- Chandler, A. L., & Hartman, M. A. (1960). Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD-25) as a facilitating agent in psychotherapy. American Medical Association Archives of General Psychiatry, 2(3), 286–299. doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1960.03590090042008

- MacLean, J. R., MacDonald, D. C., Byrne, U. P., & Hubbard, A. M. (1961). The use of LSD-25 in the treatment of alcoholism and other psychiatric problems. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 22(1), 34–45. jsad.com/doi/10.15288/qjsa.1961.22.034

- Rucker, J. J. H., Iliff, J., & Nutt, D. J. (2018). Psychiatry & the psychedelic drugs. Past, present & future. Neuropharmacology, 142, 200–18. doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.12.040

- Abuzzahab, F. S., & Anderson, B. J. (1971). A review of LSD treatment in alcoholism. International Pharmacopsychiatry, 6(4), 223–235. doi.org/10.1159/000468273

- Bogenschutz, M. P., & Forcehimes, A. A. (2016). Development of a psychotherapeutic model for psilocybin-assisted treatment of alcoholism. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 57(4), 389–414. doi.org/10.1177/0022167816673493

- Moreno, F. A., Wiegand, C. B., Keolani Taitano, E., & Delgado, P. L. (2006). Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of psilocybin in 9 patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67(11), 1735–1740. doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v67n1110

- Sanches, R. F., de Lima Osório, F., dos Santos, R. G., Macedo, L. R. H., Maia-de-Oliveira, J. P., Wichert-Ana, L., de Araujo, D. B., Riba, J., Crippa, J. A., & Hallak, J. E. C. (2016). Antidepressant effects of a single dose of ayahuasca in patients with recurrent depression: A SPECT study. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 36(1), 77–81. doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0000000000000436

- Palhano-Fontes, F., Barreto, D., Onias, H., Andrade, K. C., Novaes, M. M., Pessoa, J. A., Mota-Rolim, S. A., Osório, F. L., Sanches, R., dos Santos, R. G.,

- Carhart-Harris, R. L., Bolstridge, M., Day, C. M. J., Rucker, J., Watts, R., Erritzoe, D. E., Kaelen, M., Giribaldi, B., Bloomfield, M., Pilling, S., Rickard, J. A.,

- Bogenschutz, M. P., Forcehimes, A. A., Pommy, J. A., Wilcox, C. E., Barbosa, P. C. R., & Strassman, R. J. (2015). Psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence: A proof-of-concept study. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 29(3), 289–299. doi.org/10.1177/0269881114565144

- Johnson, M. W., Garcia-Romeu, A., Cosimano, M. P., & Griffiths, R. R. (2014). Pilot study of the 5-HT2AR agonist psilocybin in the treatment of tobacco addiction. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 28(11), 983–992. doi.org/10.1177/0269881114548296

- Johnson, M. W., Garcia-Romeu, A., & Griffiths, R. R. (2017). Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 43(1), 55–60. doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2016.1170135

- Garcia-Romeu, A., Davis, A. K., Erowid, F., Erowid, E., Griffiths, R. R., & Johnson, M. W. (2019). Cessation and reduction in alcohol consumption and misuse after psychedelic use. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 33(9), 1088–1101. doi.org/10.1177/0269881119845793

Harnessing science, love and the wisdom of lived experience, we are a force of healing and hope for individuals, families and communities affected by substance use and mental health conditions.

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

News & Events

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA)

Digital health technology shows promise for efforts to address drinking among youth.

Wednesday, May 8, 2024

This article was first published in NIAAA Spectrum Volume 16, Issue 2 .

Underage drinking and alcohol misuse by young adults are serious public health concerns in the United States. The 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) found that 15.1% of people ages 12 to 20 and 50.2% of people ages 18 to 25 reported drinking alcohol in the past month, with 8.2% of 12- to 20-year-olds and 29.5% of 18- to 25-year-olds reporting binge drinking in the past month. 1 , 2 Surveys also consistently find that young people are among the biggest users of the internet and mobile devices.

“There is an urgent need for innovative interventions to prevent alcohol misuse among our nation’s young people,” said National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Director George F. Koob, Ph.D. “Internet and mobile technologies have the potential to significantly expand our prevention efforts.”

In December 2023, NIAAA held a webinar, “ Harnessing Technology and Social Media to Address Alcohol Misuse in Adolescents and Emerging Adults ,” featuring NIAAA-supported research conducted by Maureen Walton, M.P.H., Ph.D., of the University of Michigan and Mai-Ly Steers, Ph.D., of Duquesne University.

In her talk titled “Optimizing Prevention of Alcohol Misuse and Violence Among Adolescents and Emerging Adults,” Dr. Walton discussed the importance of early interventions and how strategies that address multiple factors simultaneously may be more effective in preventing alcohol misuse over time. She also emphasized the potential benefits of more selective alcohol prevention interventions for youth at risk for binge drinking, as opposed to universal interventions that are designed to reach a broader age group.

Dr. Walton, Rebecca Cunningham, M.D., and colleagues previously developed SafERteens . SafERteens is a single-session, motivational interview-based intervention delivered by a therapist to youth ages 14 to 18 during an emergency department visit for a medical illness or injury. The researchers found that alcohol-related consequences and severe aggression were reduced in the year following the intervention.

Dr. Walton’s team has expanded SafERteens to include digital boosters such as telehealth sessions with a health coach and text messages to reduce violence and alcohol misuse. Preliminary data from a recent study show that participants who received SafERteens plus digital boosters reduced their alcohol consumption, their involvement with violence, and the consequences associated with alcohol use and violence over the course of the study.

“Digital technology is an exciting and feasible way to extend interventions and prevention to youth in real time in their daily lives,” said Dr. Walton.

In her talk, “Social Media Use - Friend or Foe? How It Has Been Problematic Yet Holds Promise for Addressing College Drinking,” Dr. Steers discussed the relationship between social media and alcohol consumption, particularly among college students. Although much about social media’s influence on alcohol use is unknown, research has consistently found a link between young people’s exposure to alcohol-related social media posts and their alcohol consumption and related problems. Alcohol-related social media posts by young people have also been found to be robust predictors of alcohol consumption and problems.

Dr. Steers and her colleagues are examining factors that influence young people’s susceptibility to alcohol-related social media content and the individual differences that affect their drinking patterns. The researchers have found that some of the main reasons that college students who drink post alcohol-related content on social media are to obtain attention and approval from their peers and to convey status or popularity. In addition, exposure to other people’s alcohol-related content may normalize drinking and portray it as socially rewarding, both of which can in turn influence a student’s alcohol consumption.

Although social media is linked to increased alcohol misuse, it also holds promise for addressing alcohol misuse among college students. Dr. Steers and her team are working to develop novel interventions targeting students ages 18 to 26 who drink excessively and who are also avid social media users. As a step toward a more standardized measure for research, her team created an alcohol-related content and drinking scale in which students use their alcohol-related posting behavior to recall their drinking retrospectively. The researchers are using this tool within the context of personalized normative feedback−a brief intervention that corrects perceptions of normal behavior−by giving people feedback on their self-reported drinking and their perceptions of how much they think their peers drink.

“Given that we know for sure that social media is a major source of social influence, future research should really try to leverage it as a tool to promote the reduction of drinking,” said Dr. Steers.