Gordon Harvey’s Elements of the Academic Essay

The “Elements of the Academic Essay” is a taxonomy of academic writing by Gordon Harvey. It identifies the key components of academic writing across the disciplines and has been widely influential. Below is a complete list (with descriptions).

Elements of an Essay

“Your main insight or idea about a text or topic, and the main proposition that your essay demonstrates. It should be true but arguable (not obviously or patently true, but one alternative among several), be limited enough in scope to be argued in a short composition and with available evidence, and get to the heart of the text or topic being analyzed (not be peripheral). It should be stated early in some form and at some point recast sharply (not just be implied), and it should govern the whole essay (not disappear in places).” — Gordon Harvey, “Elements of the Academic Essay”

- See this fuller discussion of some of the scholarly debates about the thesis statement: The Thesis Statement

- See this piece on the pros and cons of having a thesis statement: Pros and Cons of Thesis Statements

- See this piece on working with students without a thesis: What To Do When There’s No Thesis

- And see this piece for working with students with varied levels of thesis development: A Pseudo-Thesis

“The intellectual context that you establish for your topic and thesis at the start of your essay, in order to suggest why someone, besides your instructor, might want to read an essay on this topic or need to hear your particular thesis argued—why your thesis isn’t just obvious to all, why other people might hold other theses (that you think are wrong). Your motive should be aimed at your audience: it won’t necessarily be the reason you first got interested in the topic (which could be private and idiosyncratic) or the personal motivation behind your engagement with the topic. Indeed it’s where you suggest that your argument isn’t idiosyncratic, but rather is generally interesting. The motive you set up should be genuine: a misapprehension or puzzle that an intelligent reader (not a straw dummy) would really have, a point that such a reader would really overlook. Defining motive should be the main business of your introductory paragraphs, where it is usually introduced by a form of the complicating word ‘But.'” — Gordon Harvey, “The Elements of the Academic Essay”

“The data—facts, examples, or details—that you refer to, quote, or summarize to support your thesis. There needs to be enough evidence to be persuasive; it needs to be the right kind of evidence to support the thesis (with no obvious pieces of evidence overlooked); it needs to be sufficiently concrete for the reader to trust it (e.g. in textual analysis, it often helps to find one or two key or representative passages to quote and focus on); and if summarized, it needs to be summarized accurately and fairly.” –Gordon Harvey, “The Elements of the Academic Essay

“The work of breaking down, interpreting, and commenting upon the data, of saying what can be inferred from the data such that it supports a thesis (is evidence for something). Analysis is what you do with data when you go beyond observing or summarizing it: you show how its parts contribute to a whole or how causes contribute to an effect; you draw out the significance or implication not apparent to a superficial view. Analysis is what makes the writer feel present, as a reasoning individual; so your essay should do more analyzing than summarizing or quoting.” — Gordon Harvey, “The Elements of the Academic Essay”

“The recurring terms or basic oppositions that an argument rests upon, usually literal but sometimes a ruling metaphor. These terms usually imply certain assumptions—unstated beliefs about life, history, literature, reasoning, etc. that the essayist doesn’t argue for but simply assumes to be true. An essay’s keyterms should be clear in their meaning and appear throughout (not be abandoned half-way); they should be appropriate for the subject at hand (not unfair or too simple—a false or constraining opposition); and they should not be inert clichés or abstractions (e.g. “the evils of society”). The attendant assumptions should bear logical inspection, and if arguable they should be explicitly acknowledged.” — Gordon Harvey, “The Elements of the Academic Essay”

One of the most common issues we address in the writing center is the issue of structure. Many students never consciously address structure in the way that they consciously formulate a thesis. This is ironic because the two are inseparable – that is, the way you formulate an argument (structure) is essential to the argument itself (thesis). Thus, when emphasizing the importance of structure to students, it is important to remind them that structure cannot be developed in the absence of a strong thesis: you have to know what you’re arguing before you decide how to argue it.

As a writing tutor, your first task in addressing issues of structure will be to try and gauge if the student writer has an idea of what good structure looks like. Some students understand good structure, even if it’s just at an intuitive level, while others do not. If comprehension seems lacking, it may be useful to actually stop and explain what good structure looks like.

Some Ways of Thinking about Structure:

The structure of the paper should be progressive; the paper should “build” throughout. That is, there should be a logical order to the paper; each successive paragraph should build on the ideas presented in the last. In the writing center we are familiar with the scattershot essay in which the student throws out ten arguments to see what sticks. Such essays are characterized by weak or nonexistent transitions such as “My next point…” or “Another example of this…”.

Some students will understand structure better with the help of a metaphor. One particularly nice metaphor (courtesy of Dara) is to view the structure of an academic paper as a set of stairs. The paper begins with a small step; the first paragraph gives the most simple assumption or support for the argument. The paper then builds, slowly and gradually towards the top of the staircase. When the paper reaches its conclusion, it has brought the reader up to the top of the staircase to a point of new insight. From the balcony the reader can gaze out upon the original statement or question from higher ground.

How Gordon Harvey describes structure in his “Elements of the Academic Essay”:

“The sections should follow a logical order, and the links in that order should be apparent to the reader (see “stitching”). But it should also be a progressive order—there should have a direction of development or complication, not be simply a list or a series of restatements of the thesis (“Macbeth is ambitious: he’s ambitious here; and he’s ambitious here; and he’s ambitions here, too; thus, Macbeth is ambitious”). And the order should be supple enough to allow the writer to explore the topic, not just hammer home a thesis.”

“Words that tie together the parts of an argument, most commonly (a) by using transition (linking or turning) words as signposts to indicate how a new section, paragraph, or sentence follows from the one immediately previous; but also (b) by recollection of an earlier idea or part of the essay, referring back to it either by explicit statement or by echoing key words or resonant phrases quoted or stated earlier. The repeating of key or thesis concepts is especially helpful at points of transition from one section to another, to show how the new section fits in.” — Gordon Harvey, “The Elements of the Academic Essay”

Persons or documents, referred to, summarized, or quoted, that help a writer demonstrate the truth of his or her argument. They are typically sources of (a) factual information or data, (b) opinions or interpretation on your topic, (c) comparable versions of the thing you are discussing, or (d) applicable general concepts. Your sources need to be efficiently integrated and fairly acknowledged by citation.” — Gordon Harvey, “The Elements of the Academic Essay”

When you pause in your demonstration to reflect on it, to raise or answer a question about it—as when you (1) consider a counter-argument—a possible objection, alternative, or problem that a skeptical or resistant reader might raise; (2) define your terms or assumptions (what do I mean by this term? or, what am I assuming here?); (3) handle a newly emergent concern (but if this is so, then how can X be?); (4) draw out an implication (so what? what might be the wider significance of the argument I have made? what might it lead to if I’m right? or, what does my argument about a single aspect of this suggest about the whole thing? or about the way people live and think?), and (5) consider a possible explanation for the phenomenon that has been demonstrated (why might this be so? what might cause or have caused it?); (6) offer a qualification or limitation to the case you have made (what you’re not saying). The first of these reflections can come anywhere in an essay; the second usually comes early; the last four often come late (they’re common moves of conclusion).” — Gordon Harvey, “The Elements of the Academic Essay”

“Bits of information, explanation, and summary that orient the reader who isn’t expert in the subject, enabling such a reader to follow the argument. The orienting question is, what does my reader need here? The answer can take many forms: necessary information about the text, author, or event (e.g. given in your introduction); a summary of a text or passage about to be analyzed; pieces of information given along the way about passages, people, or events mentioned (including announcing or “set-up” phrases for quotations and sources). The trick is to orient briefly and gracefully.” — Gordon Harvey, “The Elements of the Academic Essay”

“The implied relationship of you, the writer, to your readers and subject: how and where you implicitly position yourself as an analyst. Stance is defined by such features as style and tone (e.g. familiar or formal); the presence or absence of specialized language and knowledge; the amount of time spent orienting a general, non-expert reader; the use of scholarly conventions of form and style. Your stance should be established within the first few paragraphs of your essay, and it should remain consistent.” — Gordon Harvey, “The Elements of the Academic Essay”

“The choices you make of words and sentence structure. Your style should be exact and clear (should bring out main idea and action of each sentence, not bury it) and plain without being flat (should be graceful and a little interesting, not stuffy).” — Gordon Harvey, “The Elements of the Academic Essay”

“It should both interest and inform. To inform—i.e. inform a general reader who might be browsing in an essay collection or bibliography—your title should give the subject and focus of the essay. To interest, your title might include a linguistic twist, paradox, sound pattern, or striking phrase taken from one of your sources (the aptness of which phrase the reader comes gradually to see). You can combine the interesting and informing functions in a single title or split them into title and subtitle. The interesting element shouldn’t be too cute; the informing element shouldn’t go so far as to state a thesis. Don’t underline your own title, except where it contains the title of another text.” — Gordon Harvey, “The Elements of the Academic Essay”

A student’s argument serves as the backbone to a piece of writing. Often expressed in the form of a one-sentence thesis statement, an argument forms the basis for a paper, defines the writer’s feelings toward a particular topic, and engages the reader in a discussion about a particular topic. Because an argument bears so much weight on the success of a paper, students may spend hours searching for that one, arguable claim that will carry them through to the assigned page limit. Formulating a decent argument about a text is tricky, especially when a professor does not distribute essay prompts—prompting students to come to the Writing Center asking that eternal question: “ What am I going to write about?!”

Formulating the Idea of an Argument (Pre-Writing Stage)

Before a student can begin drafting a paper, he or she must have a solid argument. Begin this process by looking at the writing assignment rubric and/or prompt assigned by the professor. If no particular prompt was assigned, ask the student what interests him or her in the class? Was there a reading assignment that was particularly compelling and/or interesting? Engage the student in a conversation about the class or the paper assignment with a pen and paper in their hand. When an interesting idea is conveyed, ask them to jot it down on a paper. Look for similarities or connections in their written list of ideas.

If a student is still lost, it’s helpful to remind them to remember to have a motive for writing. Besides working to pass a class or getting a good grade, what could inspire a student to write an eight page paper and enjoy the process? Relating the assigned class readings to incidents in a student’s own life often helps create a sense of urgency and need to write an argument. In an essay entitled “The Great Conversation (of the Dining Hall): One Student’s Experience of College-Level Writing,” student Kimberly Nelson remembers her passion for Tolkien fueled her to write a lengthy research paper and engage her friends in discussions concerning her topic (290).

Additional ideas for consultations during the pre-writing stage .

Formulating the Argument

The pre-writing stage is essential because arguments must “be limited enough in scope to be argued in a short composition” according to Harvey’s Elements of the Academic Essay . Narrow down the range of ideas so the student may write a more succinct paper with efficient language. When composing an argument (and later, a thesis), avoid definitive statements—arguments are arguable , and a great paper builds on a successive chain of ideas grounded in evidence to support an argument. It is of paramount importance to remind your student that the argument will govern the entire paper and not “disappear in places” (Harvey). When composing an actual paper, it’s helpful to Post-It note a summary of your argument on your computer screen to serve as a constant reminder of why you are writing.

Difficulties with Arguments and International Students

When international students arrive at Pomona College, they are often unsure of what the standard academic writing expectations are. If a student submits a draft to you devoid of any argument, it’s important to remember that the conventions of their home country may not match up to the standards we expect to see here. Some countries place more of an emphasis on a summary of ideas of others rather than generating entirely new arguments. If this is the case for your student, (gently) remind him or her that most Pomona College professors expect to see new arguments generated from the students and that “summary” papers are frowned upon. Don’t disparage their previous work—use the ideas present in their paragraphs as a launching point for crafting a new, creative argument.

“Students, like all writers, must fictionalize their audience.”

– Fred Pfister and Joanne Petrik, “A Heuristic Model for Creating a Writer’s Audience” (1980)

The main purpose of imagining or fictionalizing an audience is to allow the student to position his/her paper within the discourse and in conversation with other academics. By helping the student acknowledge the fact that both the writer (the student) and the reader (the audience) play a role in the writing process, the student will be better able to clarify and strengthen his/her argument.

Moreover, the practice of fictionalizing the audience should eventually help the student learn how to become his/her own reader. By adopting the role of both the writer and the reader, the student will be able to further develop his ability to locate his/her text in a discourse community.

During a consultation, you may notice that a student’s argument does not actually engage in a conversation with the members of its respective discourse community. If his/her paper does not refer to other texts or ask questions that are relevant to this particular discourse, you may need to ask the student to imagine who his/her audience is as well as what the audience’s reaction to the paper may look like.

Although the student’s immediate answer will most likely be his/her professor, you should advise the student to attempt imagining an audience beyond his/her class—an audience composed of people who are invested in this discourse or this specific topic.

If your student cannot imagine or fictionalize such an audience, it may be because the student may not believe that he/she know enough about the topic to address such a knowledgeable audience. In this case, you should advise the student to pretend that he/she is an expert on the topic or that the student’s paper will be published and read by other members of the discourse community.

The student, however, should not pander to the audience and “undervalue the responsibility that [he/she] has to [the] subject” (Ede and Lunsford, 1984). Advise him/her to avoid re-shaping the paper so that it merely caters to or appeases the audience.

- Good and bad News of The Elements of Style

Mailing Address

Pomona College 333 N. College Way Claremont , CA 91711

Get in touch

Give back to pomona.

Part of The Claremont Colleges

- Generating Ideas

- Drafting and Revision

- Sources and Evidence

- Style and Grammar

- Specific to Creative Arts

- Specific to Humanities

- Specific to Sciences

- Specific to Social Sciences

- CVs, Résumés and Cover Letters

- Graduate School Applications

- Other Resources

- Hiatt Career Center

- University Writing Center

- Classroom Materials

- Course and Assignment Design

- UWP Instructor Resources

- Writing Intensive Requirement

- Criteria and Learning Goals

- Course Application for Instructors

- What to Know about UWS

- Teaching Resources for WI

- FAQ for Instructors

- FAQ for Students

- Journals on Writing Research and Pedagogy

- University Writing Program

- Degree Programs

- Majors and Minors

- Graduate Programs

- The Brandeis Core

- School of Arts and Sciences

- Brandeis Online

- Brandeis International Business School

- Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

- Heller School for Social Policy and Management

- Rabb School of Continuing Studies

- Precollege Programs

- Faculty and Researcher Directory

- Brandeis Library

- Academic Calendar

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Summer School

- Financial Aid

- Research that Matters

- Resources for Researchers

- Brandeis Researchers in the News

- Provost Research Grants

- Recent Awards

- Faculty Research

- Student Research

- Centers and Institutes

- Office of the Vice Provost for Research

- Office of the Provost

- Housing/Community Living

- Campus Calendar

- Student Engagement

- Clubs and Organizations

- Community Service

- Dean of Students Office

- Orientation

- Spiritual Life

- Graduate Student Affairs

- Directory of Campus Contacts

- Division of Creative Arts

- Brandeis Arts Engagement

- Rose Art Museum

- Bernstein Festival of the Creative Arts

- Theater Arts Productions

- Brandeis Concert Series

- Public Sculpture at Brandeis

- Women's Studies Research Center

- Creative Arts Award

- Our Jewish Roots

- The Framework for the Future

- Mission and Diversity Statements

- Distinguished Faculty

- Nobel Prize 2017

- Notable Alumni

- Administration

- Working at Brandeis

- Commencement

- Offices Directory

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni & Friends

- Parents & Families

- 75th Anniversary

- New Students

- Shuttle Schedules

- Support at Brandeis

Writing Resources

Terminology: elements of the academic essay.

This handout is available for download in DOCX format and PDF format .

Your main insight or idea about a text or topic, and the main proposition that your essay demonstrates. It should be true but arguable (not obviously or patently true, but one alternative among several), be limited enough in scope to be argued in a short composition and with available evidence, and get to the heart of the text or topic being analyzed (not be peripheral). It should be stated early in some form and at some point recast sharply (not just be implied), and it should govern the whole essay (not disappear in places).

The intellectual context that you establish for your topic and thesis at the start of your essay, in order to suggest why someone, besides your instructor, might want to read an essay on this topic or need to hear your particular thesis argued—why your thesis isn’t just obvious to all, why other people might hold other theses (that you think are wrong). Your motive should be aimed at your audience: it won’t necessarily be the reason you first got interested in the topic (which could be private and idiosyncratic) or the personal motivation behind your engagement with the topic. Indeed it’s where you suggest that your argument isn’t idiosyncratic, but rather is generally interesting. The motive you set up should be genuine: a misapprehension or puzzle that an intelligent reader (not a straw dummy) would really have, a point that such a reader would really overlook. Defining motive should be the main business of your introductory paragraphs, where it is usually introduced by a form of the complicating word “But.”

The data—facts, examples, or details—that you refer to, quote, or summarize to support your thesis. There needs to be enough evidence to be persuasive; it needs to be the right kind of evidence to support the thesis (with no obvious pieces of evidence overlooked); it needs to be sufficiently concrete for the reader to trust it (e.g. in textual analysis, it often helps to find one or two key or representative passages to quote and focus on); and if summarized, it needs to be summarized accurately and fairly.

The work of breaking down, interpreting, and commenting upon the data, of saying what can be inferred from the data such that it supports a thesis (is evidence for something). Analysis is what you do with data when you go beyond observing or summarizing it: you show how its parts contribute to a whole or how causes contribute to an effect; you draw out the significance or implication not apparent to a superficial view. Analysis is what makes the writer feel present, as a reasoning individual; so your essay should do more analyzing than summarizing or quoting.

The recurring terms or basic oppositions that an argument rests upon, usually literal but sometimes a ruling metaphor. These terms usually imply certain assumptions—unstated beliefs about life, history, literature, reasoning, etc. that the essayist doesn’t argue for but simply assumes to be true. An essay’s keyterms should be clear in their meaning and appear throughout (not be abandoned half-way); they should be appropriate for the subject at hand (not unfair or too simple—a false or constraining opposition); and they should not be inert clichés or abstractions (e.g. “the evils of society”). The attendant assumptions should bear logical inspection, and if arguable they should be explicitly acknowledged.

The sequence of main sections or sub-topics, and the turning points between them. The sections should be perceptible and follow a logical order, and the links in that order should be apparent to the reader (but not heavy-handed: see “stitching”). But it should also be a progressive order—it should have a continuous direction of development or complication , not be simply a list or a series of restatements of or takes on the thesis (“Macbeth is ambitious: he’s ambitious here; and he’s ambitious here; and he’s ambitions here, too; thus, Macbeth is ambitious”) or list of elements found in the text. And the order should be supple enough to allow the writer to explore the topic, not just hammer home a thesis. (If the essay is complex or long, its structure may be briefly announced or hinted at after the thesis, in a road-map or plan sentence—or even in the thesis statement itself, if you’re clever enough.)

Words that tie together the parts of an argument, most commonly (a) by using transition (linking or turning) words as signposts to indicate how a new section, paragraph, or sentence follows from the one immediately previous; but also (b) by recollection of an earlier idea or part of the essay, referring back to it either by explicit statement or by echoing key words or resonant phrases quoted or stated earlier. The repeating of key or thesis concepts is especially helpful at points of transition from one section to another, to show how the new section fits in.

Persons or documents, referred to, summarized, or quoted, that help a writer demonstrate the truth of his or her argument. They are typically sources of (a) factual information or data, (b) opinions or interpretation on your topic, (c) comparable versions of the thing you are discussing, or (d) applicable general concepts. Your sources need to be efficiently integrated and fairly acknowledged by citation.

When you pause in your demonstration to reflect on it, to raise or answer a question about it—as when you (1) consider a counter-argument—a possible objection, alternative, or problem that a skeptical or resistant reader might raise; (2) define your terms or assumptions (what do I mean by this term? or, what am I assuming here?); (3) handle a newly emergent concern (but if this is so, then how can X be?); (4) draw out an implication (so what? what might be the wider significance of the argument I have made? what might it lead to if I’m right? or, what does my argument about a single aspect of this suggest about the whole thing? or about the way people live and think?), and (5) consider a possible explanation for the phenomenon that has been demonstrated (why might this be so? what might cause or have caused it?); (6) offer a qualification or limitation to the case you have made (what you’re not saying). The first of these kinds of reflections can come anywhere in an essay; the second usually comes early; the last four often come late (they’re common moves of conclusion). Most good essays have some of the first kind, and often several of the others besides.

Bits of information, explanation, and summary that orient the reader who isn’t expert in the subject, enabling such a reader to follow the argument. The orienting question is, what does my reader need here? The answer can take many forms: necessary information about the text, author, or event (e.g. given in your introduction); a summary of a text or passage about to be analyzed; pieces of information given along the way about passages, people, or events mentioned (including announcing or “set-up” phrases for quotations and sources). The trick is to orient briefly and gracefully—and not to orient when your audience doesn’t need it: e.g. “writer William Shakespeare.”

The implied relationship of you, the writer, to your readers and subject: how and where you implicitly position yourself as an analyst. Stance is defined by such features as style and tone (e.g. familiar or formal); the presence or absence of specialized language and knowledge; the amount of time spent orienting a general, non-expert reader; the use of scholarly conventions of form and style. Your stance should be established within the first few paragraphs of your essay, and it should remain consistent.

The choices you make of words and sentence structure. Your style should be exact and clear (should bring out main idea and action of each sentence, not bury it) and plain without being flat (should be graceful and a little interesting, not stuffy).

It should both interest and inform. To inform—i.e. inform a general reader who might be browsing in an essay collection or bibliography—your title should give the subject and focus of the essay. To interest, your title might include a linguistic twist, paradox, sound pattern, or striking phrase taken from one of your sources (the aptness of which phrase the reader comes gradually to see). You can combine the interesting and informing functions in a single title or split them into title and subtitle. The interesting element shouldn’t be too cute; the informing element shouldn’t go so far as to state a thesis. Don’t underline your own title, except where it contains the title of another text.

Credit: Adapted from Gordon Harvey, The Elements of the Academic Essay , 2009.

- Resources for Students

- Writing Intensive Instructor Resources

- Research and Pedagogy

Gordon Harvey’s “Elements of the Academic Essay”

Have you ever wondered what professors are looking for when they read your essays? This adaptation of Gordon Harvey’s “Elements of the Academic Essay” provides a vocabulary for that will help you to identify patterns in your own writing.

The specific issue that you believe is unresolved or has not been adequately addressed that you choose to address in your academic essay. This may appear as a gap, tension, pattern, anomaly, contradiction, ambiguity, nuance in or debate about your exhibit or topic. The problem you identify should be genuine: a misapprehension or puzzle that an intelligent reader would really have, a point that such a reader would really overlook. The problem can be transformed into a specific question that can be explored and answered in a meaningful way via analysis of expert opinion and evidence. It’s the debate you want to enter.

Your main insight or idea about an exhibit or topic, and the main proposition that your essay demonstrates; it is your response to the problem that you have identified. It should be true but arguable (not a fact and obviously or patently true, but one alternative among several), be limited enough in scope to be argued in a short composition and with available evidence, and get to the heart of the text or topic being analyzed (not be peripheral). It should be stated early in some form and, at some point, recast sharply (not just be implied), and it should govern the whole essay (not disappear in places). It’s your contribution to the debate.

The intellectual context that you establish for your topic and thesis at the start of your essay to suggest why someone, besides your instructor, might want to read an essay on this topic or need to hear your particular thesis argued i.e. why your thesis isn’t just obvious to all, or why other people might hold other theses (that you think are wrong). Your motive should be aimed at your audience; it won’t necessarily be the reason you first got interested in the topic or the personal motivation behind your engagement with the topic. Defining motive should be the main business of your introductory paragraphs; there you should explain why the problem being addressed is significant (to the reader). It’s the specific reason why the debate matters—why readers should care about your thesis.

The data—facts, examples, or details—that you analyze, refer to, quote, or summarize to support your thesis. There needs to be enough evidence to be persuasive; it needs to be the right kind of evidence to support the thesis (with no obvious pieces of evidence overlooked); it needs to be sufficiently concrete for the reader to trust it (e.g. in textual analysis, it often helps to find one or two key or representative passages to quote and focus on); and if summarized, it needs to be summarized accurately and fairly. It’s the sources that you’re analyzing—what you need to define the debate.

The work of breaking down, interpreting, and commenting upon the data, of saying what can be inferred from the data such that it supports a thesis (is evidence for something). Analysis is what you do with data when you go beyond observing or summarizing it: you show how its parts contribute to a whole or how causes contribute to an effect; you draw out the significance or implication not apparent to a superficial view. Analysis is what makes the writer feel present, as a reasoning individual; therefore, your essay should do more analyzing than summarizing or quoting. It’s the how and why of your argument.

The recurring terms or basic oppositions that an argument rests upon, usually literal but sometimes a ruling metaphor. These terms usually imply certain assumptions—unstated beliefs about life, history, literature, reasoning, etc. that the essayist doesn’t argue for but simply assumes to be true. An essay’s key terms should be clear in their meaning and appear throughout (not be abandoned half-way); they should be appropriate for the subject at hand (not unfair or too simple—a false or constraining opposition); and they should not be inert clichés or abstractions (e.g. “the evils of society”). The attendant assumptions should bear logical inspection, and if arguable, they should be explicitly acknowledged. It’s the vocabulary your audience needs to enter this debate.

The sequence of main sections or sub-topics, and the turning points between them. The sections should follow a logical order, and the links in that order should be apparent to the reader (see “stitching”). But it should also be a progressive order—there should have a direction of development or complication, not be simply a list or a series of restatements of the thesis (“Macbeth is ambitious: he’s ambitious here; and he’s ambitious here; and he’s ambitions here, too; thus, Macbeth is ambitious”). The order should also be supple enough to allow the writer to explore the topic, not just hammer home a thesis. (If the essay is complex or long, its structure may be briefly announced or hinted at after the thesis, in a roadmap or plan sentence.) It’s the organization of your overall essay and your individual paragraphs.

Words that tie together the parts of an argument, most commonly (a) by using transition (linking or turning) words as signposts to indicate how a new section, paragraph, or sentence follows from the one immediately previous; but also (b) by recollection of an earlier idea or part of the essay, referring back to it either by explicit statement or by echoing key words or resonant phrases quoted or stated earlier. The repeating of key or thesis concepts is especially helpful at points of transition from one section to another, to show how the new section fits in. It’s how you tie together the pieces and show the relevance of all of them.

Persons or documents, referred to, summarized, or quoted, that help a writer demonstrate the truth of his or her argument. They are typically sources of (a) factual information or data, (b) opinions or interpretation on your topic, (c) comparable versions of the thing you are discussing, or (d) applicable general concepts. Your sources need to be efficiently integrated and fairly acknowledged by citation. Secondary sources are texts that are most central to the debate you’re entering (not evidence to “back you up”).

Reflecting and Synthesis

When you pause in your demonstration to reflect on it, to raise or respond to a complication about it—as when you (1) consider a counter-argument—a possible objection, alternative, or problem that a skeptical or resistant reader might raise; (2) define your terms or assumptions (what do I mean by this term? or, what am I assuming here?); (3) handle a newly emergent concern (but if this is so, then how can X be?); (4) draw out an implication (so what? what might be the wider significance of the argument I have made? what might it lead to if I’m right? or, what does my argument about a single aspect of this suggest about the whole thing? or about the way people live and think?), and (5) consider a possible explanation for the phenomenon that has been demonstrated (why might this be so? what might cause or have caused it?); (6) offer a qualification or limitation to the case you have made (what you’re not saying). The first of these reflections can come anywhere in an essay; the second usually comes early; the last four often come late (they’re common moves of conclusion). It’s you reviewing points you’ve covered to help your reader make connections.

Orienting/Contextualization

Bits of information, explanation, and summary that orient the reader who isn’t expert in the subject, enabling such a reader to follow the argument. The orienting question is, what does my reader need here? The answer can take many forms: necessary information about the text, author, or event (e.g. given in your introduction); a summary of a text or passage about to be analyzed; pieces of information given along the way about passages, people, or events mentioned (including announcing or “set-up” phrases for quotations and sources). The trick is to orient briefly and gracefully. It’s you providing your reader with directions or points on a map introducing any terms or sources that a reader may not know.

The implied relationship of you, the writer, to your readers and subject: how and where you implicitly position yourself as an analyst. Stance is defined by such features as style and tone (e.g. familiar or formal); the presence or absence of specialized language and knowledge; the amount of time spent orienting a general, non-expert reader; the use of scholarly conventions of form and style. Your stance should be established within the first few paragraphs of your essay, and it should remain consistent. It’s where you stand on the intellectual problem (like a thesis but requires your reader to read your entire essay).

The choices you make of words and sentence structure. Your style should be exact and clear (should bring out main idea and action of each sentence, not bury it) and plain without being flat (should be graceful and a little interesting, not stuffy). It’s your unique way of writing for the specific audience.

It should both interest and inform. To inform your title should give the subject and focus of the essay. To interest, your title might include a linguistic twist, paradox, sound pattern, or striking phrase taken from one of your sources (the aptness of which phrase the reader comes gradually to see). You can combine the interesting and informing functions in a single title or split them into title and subtitle. The interesting element shouldn’t be too cute; the informing element shouldn’t go so far as to state a thesis. Effective titles often hint at the problem or thesis of the essay. Don’t underline your own title, except where it contains the title of another text. It tells your reader why they should read your essay and what you’re arguing about in it.

Harvey, G. (2009). “Elements of the Academic Essay.” Harvard College Writing Program. Retrieved April 10, 2023, from https://writingproject.fas.harvard.edu/files/hwp/files/hwp_brief_guides_elements.pdf

Writing About Literature Copyright © by Rachael Benavidez and Kimberley Garcia is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

How to Write an Academic Essay: All You Need to Know

Mark Bradford

This article aims to assist students who start writing an essay. Here, the readers can learn how to write an academic essay, how to format an essay , and create a perfect outline from introduction to conclusion.

What Is an Academic Essay: Its Purpose and Importance

Before writing an essay, students have to figure out its essence. What is an academic essay in general? Many understand it as writing that develops ideas or arguments through evidence and analysis. Regardless of the type of essay, its purpose is to convey knowledge on a specific topic, describe a problem or offer a solution.

To say that academic essays are essential for higher education is an understatement. Writing an essay develops multiple skills, including the next:

- Writing Process Enhances Critical Thinking in Students

Even those who pay for essay know how much intellectual effort it requires. Through academic writing, students train to research background information and key terms, find quality sources and apply the newfound knowledge.

- Academic Writing Develops Professionalism

To write an essay correctly, a person must stick to guidelines. Because the academic essay format requires following many rules, the writing process improves discipline.

Characteristics of an Academic Essay

An academic format essay exists to walk the readers through the author's main points. Therefore, a writer must focus on making the paper understandable. The clue is to meet the following requirements:

Clear and Concise Thesis Statement

A quality thesis statement is an integral part of writing an academic essay. In any type of essay or research paper, the thesis statement decides how the entire essay looks. So, the author should shrink their main idea into one sentence.

Supported Arguments

Undeniably, every thesis statement needs arguments with supporting evidence. The readers see this evidence and trust what the author said in the thesis statement and body paragraphs. That is why profound research helps to write an essay!

Logical Outline Structure

Any type of essay requires an introduction section, several body paragraphs, and a conclusion. However, dividing the text into these parts isn't enough. The main idea is to make a solid outline that logically connects all parts.

Formal Tone

The point of an argumentative paper is to describe ideas using solely formal language. So, no slang, only scientific terms!

Types of Academic Essays

To start writing an academic essay, one has to know its type. Overall, an academic essay can fall into one of these categories:

Expository Essay

This kind of paper exists to describe and explain a specific topic in detail. An expository essay gives facts without emotions. Surprisingly, all students are familiar with expository writing since they visit lectures and see presentations.

Argumentative Essay

As their name implies, argumentative essays present arguments to convince the readers to take an author's side. All argumentative essay outline examples have several body paragraphs with supporting points for a thesis statement. In an argumentative essay outline, every topic sentence has strong evidence.

Descriptive Essay

Are there papers that describe objects, people, events, or anything else? Yes, descriptive essays do that! Every body paragraph, introduction, and conclusion create an immersive experience for the audience.

Persuasive Essay

The point of such essays is to convince people that the author's ideas are correct. But, a persuasive essay contains objective evidence and moral reasoning.

Narrative Essay

If someone wants to describe a personal experience in their own words, a narrative essay helps out! An introduction paragraph hooks people, while the body paragraphs have a thrilling plot. Finally, the conclusion states the moral of the story.

How to Write an Academic Essay: 6 Important Steps

All students need someone to advise them on how to write an academic essay. An analytical essay, blog post, literary analysis essay outline, or any other example essay needs preparation. So, memorize the following ideas!

.png)

Understanding the Essay Prompt

Sometimes, academic essay titles aren't enough for students to understand the assignment. For this reason, writing an academic essay prompt is a necessary step for teachers. A prompt can be one sentence or several full sentences long, discussing the theme and needed key points in the paper. How to understand the prompt correctly?

First, a person should thoroughly read every sentence to find all confusing phrases or words. In such a case, asking a teacher is necessary! Secondly, it is essential to highlight important words, more specifically verbs. For example, some prompts ask writers to analyze, describe or elaborate.

Conducting Research and Gathering Evidence

Since the thesis statement in every academic essay requires supporting points, a preliminary examination is crucial. To begin with, a writer has to assess their time limits and existing knowledge. For instance, they may already know something about the topic. Plus, it's half the success if they know possible examples of evidence sources. Finally, it is necessary to check all literature for an academic format essay for reliability!

A bonus tip is to collect evidence from multiple media types. For example, information on global pandemic topics is online, not in libraries.

Creating an Academic Essay Outline

Undoubtedly, essay outlines are like skeletons for the text. The plan can be either in the form of an alphanumeric outline or a full-sentence outline. Overall, how to make an outline for an essay and succeed? Every academic essay outline has several components:

Introduction

- Hook or attention-grabbing opening

Any academic essay example has to begin with a captivating point or idea. This keeps people interested!

- Background information

The introduction paragraph also mentions existing theories. Students base their essays on these sources.

- Thesis statement

Next, what is a thesis statement generally? In academic essay format, a thesis statement ends the introduction. It briefly expresses an author's main point.

Body paragraphs

- Topic sentences and supporting arguments

Every body paragraph starts with a topic sentence that expresses one idea. Then, supporting points elaborate further on these full sentences.

- Evidence, examples, and citations

Each paragraph should contain examples or facts that support the author's point.

- Analysis and critical thinking

While developing the essay outlines, students should be able to interpret the information and place it accordingly.

Conclusion

- Summarizing key points

Every essay example summarizes the main ideas and supporting points in the conclusion.

- Restating the thesis

A conclusion also repeats the thesis statement using different wording.

- Providing a concluding thought or recommendation

A final suggestion from the author helps to wrap up a conclusion.

Writing the Draft

The next step after building outlines is writing an academic essay draft. Usually, this is a rough copy of the future work, which requires additional time. So, a student can write as many drafts as they want if the deadline allows it.

Naturally, the first draft looks the least like the final paper. For instance, someone might plan three body paragraphs that turn into a five-paragraph essay. Ideas and supporting points can transform during the initial brainstorming, and full sentences can appear and disappear.

Although drafts constantly change, their point is to stick to the original outlines. And, as far as creativity goes, every paragraph must connect to the thesis. However, the whole academic essay format is optional in drafts since they become polished later.

Referencing and Citations

By all means, an example of an academic essay requires referencing and citations. The point here is to acknowledge every idea that a student borrows. If everything is correct, then the paper passes a plagiarism check.

Which citation style to choose? There are several examples. For instance, MLA style fits a literary analysis essay or any other humanities paper. But, science works usually have APA citation style, and business essays use the Chicago style.

Revising and Editing

The concluding stage of writing an academic essay is making the final minor adjustments. Surprisingly, rereading is necessary even if people order essay online to save time. Contrarily, skipping this part lowers the grade since a teacher can point out the obvious mistakes. Also, remember that lengthy work requires more time for checking than a five-paragraph essay.

Tips on Writing an Academic Essay

What else should a person know before submitting an academic essay? There are a few tips:

.png)

- Start early

Although the urge to procrastinate is strong, overcoming it is crucial. So, start early instead of rushing the night before the deadline.

- Carefully read the prompt

Sometimes, people hurry when reading academic essay titles and prompts. As a result, they misinterpret the task. Hence, it is essential to take time and analyze the prompt.

- Thoughtfully choose the point of view

Indeed, everyone has an opinion on particular topics. However, finding evidence is tricky if the student's point of view is unpopular.

- Filter other people's ideas

Usually, professional essay writers recommend studying as many sources as possible. Because they are different, the goal is to choose only the best notions.

- Ask a friend for help

Some writers sample academic essay online or search for ' write essay for me ' services. Meanwhile, the others get assistance from the people around them. Get a friend to reread the draft!

Final Thoughts

Overall, we discussed everything related to academic papers, including their meaning, importance, and outlines. Our essay writing service has much more to offer. For instance, we have an academic essay example, advice on a full-sentence outline, and other info!

- Plagiarism Report

- Unlimited Revisions

- 24/7 Support

Essay Writing Guide

Essay Outline

Last updated on: Jun 10, 2023

A Complete Essay Outline - Guidelines and Format

By: Nova A.

13 min read

Reviewed By: Melisa C.

Published on: Jan 15, 2019

To write an effective essay, you need to create a clear and well-organized essay outline. An essay outline will shape the essay’s entire content and determine how successful the essay will be.

In this blog post, we'll be going over the basics of essay outlines and provide a template for you to follow. We will also include a few examples so that you can get an idea about how these outlines look when they are put into practice.

Essay writing is not easy, but it becomes much easier with time, practice, and a detailed essay writing guide. Once you have developed your outline, everything else will come together more smoothly.

The key to success in any area is preparation - take the time now to develop a solid outline and then write your essays!

So, let’s get started!

On this Page

What is an Essay Outline?

An essay outline is your essay plan and a roadmap to essay writing. It is the structure of an essay you are about to write. It includes all the main points you have to discuss in each section along with the thesis statement.

Like every house has a map before it is constructed, the same is the importance of an essay outline. You can write an essay without crafting an outline, but you may miss essential information, and it is more time-consuming.

Once the outline is created, there is no chance of missing any important information. Also, it will help you to:

- Organize your thoughts and ideas.

- Understand the information flow.

- Never miss any crucial information or reference.

- Finish your work faster.

These are the reasons if someone asks you why an essay outline is needed. Now there are some points that must be kept in mind before proceeding to craft an essay outline.

Easily Outline Your Essays In Seconds!

Prewriting Process of Essay Outline

Your teacher may ask you to submit your essay outline before your essay. Therefore, you must know the preliminary guidelines that are necessary before writing an essay outline.

Here are the guidelines:

- You must go through your assignments’ guidelines carefully.

- Understand the purpose of your assignment.

- Know your audience.

- Mark the important point while researching your topic data.

- Select the structure of your essay outline; whether you are going to use a decimal point bullet or a simple one.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

How to Write an Essay Outline in 4 Steps

Creating an essay outline is a crucial step in crafting a well-structured and organized piece of writing. Follow these four simple steps to create an effective outline:

Step 1: Understand the Topic

To begin, thoroughly grasp the essence of your essay topic.

Break it down into its key components and identify the main ideas you want to convey. This step ensures you have a clear direction and focus for your essay.

Step 2: Brainstorm and Gather Ideas

Let your creativity flow and brainstorm ideas related to your topic.

Jot down key pieces of information, arguments, and supporting evidence that will strengthen your essay's overall message. Consider different perspectives and potential counterarguments to make your essay well-rounded.

Step 3: Organize Your Thoughts

Now it's time to give structure to your ideas.

Arrange your main points in a logical order, starting with an attention-grabbing introduction, followed by body paragraphs that present your arguments.

Finally, tie everything together with a compelling conclusion. Remember to use transitional phrases to create smooth transitions between sections.

Step 4: Add Depth with Subpoints

To add depth and clarity to your essay, incorporate subpoints under each main point.

These subpoints provide more specific details, evidence, or examples that support your main ideas. They help to further strengthen your arguments and make your essay more convincing.

By following these four steps - you'll be well on your way to creating a clear and compelling essay outline.

Essay Outline Format

It is an easy way for you to write your thoughts in an organized manner. It may seem unnecessary and unimportant, but it is not.

It is one of the most crucial steps for essay writing as it shapes your entire essay and aids the writing process.

An essay outline consists of three main parts:

1. Introduction

The introduction body of your essay should be attention-grabbing. It should be written in such a manner that it attracts the reader’s interest. It should also provide background information about the topic for the readers.

You can use a dramatic tone to grab readers’ attention, but it should connect the audience to your thesis statement.

Here are some points without which your introduction paragraph is incomplete.

To attract the reader with the first few opening lines, we use a hook statement. It helps engage the reader and motivates them to read further. There are different types of hook sentences ranging from quotes, rhetorical questions to anecdotes and statistics, and much more.

Are you struggling to come up with an interesting hook? View these hook examples to get inspired!

A thesis statement is stated at the end of your introduction. It is the most important statement of your entire essay. It summarizes the purpose of the essay in one sentence.

The thesis statement tells the readers about the main theme of the essay, and it must be strong and clear. It holds the entire crux of your essay.

Need help creating a strong thesis statement? Check out this guide on thesis statements and learn to write a statement that perfectly captures your main argument!

2. Body Paragraphs

The body paragraphs of an essay are where all the details and evidence come into play. This is where you dive deep into the argument, providing explanations and supporting your ideas with solid evidence.

If you're writing a persuasive essay, these paragraphs will be the powerhouse that convinces your readers. Similarly, in an argumentative essay, your body paragraphs will work their magic to sway your audience to your side.

Each paragraph should have a topic sentence and no more than one idea. A topic sentence is the crux of the contents of your paragraph. It is essential to keep your reader interested in the essay.

The topic sentence is followed by the supporting points and opinions, which are then justified with strong evidence.

3. Conclusion

When it comes to wrapping up your essay, never underestimate the power of a strong conclusion. Just like the introduction and body paragraphs, the conclusion plays a vital role in providing a sense of closure to your topic.

To craft an impactful conclusion, it's crucial to summarize the key points discussed in the introduction and body paragraphs. You want to remind your readers of the important information you shared earlier. But keep it concise and to the point. Short, powerful sentences will leave a lasting impression.

Remember, your conclusion shouldn't drag on. Instead, restate your thesis statement and the supporting points you mentioned earlier. And here's a pro tip: go the extra mile and suggest a course of action. It leaves your readers with something to ponder or reflect on.

5 Paragraph Essay Outline Structure

An outline is an essential part of the writing as it helps the writer stay focused. A typical 5 paragraph essay outline example is shown here. This includes:

- State the topic

- Thesis statement

- Introduction

- Explanation

- A conclusion that ties to the thesis

- Summary of the essay

- Restate the thesis statement

Tough Essay Due? Hire Tough Writers!

Essay Outline Template

The outline of the essay is the skeleton that you will fill out with the content. Both outline and relevant content are important for a good essay. The content you will add to flesh out the outline should be credible, relevant, and interesting.

The outline structure for the essay is not complex or difficult. No matter which type of essay you write, you either use an alphanumeric structure or a decimal structure for the outline.

Below is an outline sample that you can easily follow for your essay.

Essay Outline Sample

Essay Outline Examples

An essay outline template should follow when you start writing the essay. Every writer should learn how to write an outline for every type of essay and research paper.

Essay outline 4th grade

Essay outline 5th grade

Essay outline high school

Essay outline college

Given below are essay outline examples for different types of essay writing.

Argumentative Essay Outline

An argumentative essay is a type of essay that shows both sides of the topic that you are exploring. The argument that presents the basis of the essay should be created by providing evidence and supporting details.

Persuasive Essay Outline

A persuasive essay is similar to an argumentative essay. Your job is to provide facts and details to create the argument. In a persuasive essay, you convince your readers of your point of view.

Compare and Contrast Essay Outline

A compare and contrast essay explains the similarities and differences between two things. While comparing, you should focus on the differences between two seemingly similar objects. While contrasting, you should focus on the similarities between two different objects.

Narrative Essay Outline

A narrative essay is written to share a story. Normally, a narrative essay is written from a personal point of view in an essay. The basic purpose of the narrative essay is to describe something creatively.

Expository Essay Outline

An expository essay is a type of essay that explains, analyzes, and illustrates something for the readers. An expository essay should be unbiased and entirely based on facts. Be sure to use academic resources for your research and cite your sources.

Analytical Essay Outline

An analytical essay is written to analyze the topic from a critical point of view. An analytical essay breaks down the content into different parts and explains the topic bit by bit.

Rhetorical Analysis Essay Outline

A rhetorical essay is written to examine the writer or artist’s work and develop a great essay. It also includes the discussion.

Cause and Effect Essay Outline

A cause and effect essay describes why something happens and examines the consequences of an occurrence or phenomenon. It is also a type of expository essay.

Informative Essay Outline

An informative essay is written to inform the audience about different objects, concepts, people, issues, etc.

The main purpose is to respond to the question with a detailed explanation and inform the target audience about the topic.

Synthesis Essay Outline

A synthesis essay requires the writer to describe a certain unique viewpoint about the issue or topic. Create a claim about the topic and use different sources and information to prove it.

Literary Analysis Essay Outline

A literary analysis essay is written to analyze and examine a novel, book, play, or any other piece of literature. The writer analyzes the different devices such as the ideas, characters, plot, theme, tone, etc., to deliver his message.

Definition Essay Outline

A definition essay requires students to pick a particular concept, term, or idea and define it in their own words and according to their understanding.

Descriptive Essay Outline

A descriptive essay is a type of essay written to describe a person, place, object, or event. The writer must describe the topic so that the reader can visualize it using their five senses.

Evaluation Essay Outline

Problem Solution Essay Outline

In a problem-solution essay, you are given a problem as a topic and you have to suggest multiple solutions on it.

Scholarship Essay Outline

A scholarship essay is required at the time of admission when you are applying for a scholarship. Scholarship essays must be written in a way that should stand alone to help you get a scholarship.

Reflective Essay Outline

A reflective essay is written to express your own thoughts and point of view regarding a specific topic.

Getting started on your essay? Give this comprehensive essay writing guide a read to make sure you write an effective essay!

With this complete guide, now you understand how to create an outline for your essay successfully. However, if you still can’t write an effective essay, then the best option is to consult a professional academic writing service.

Essay writing is a dull and boring task for some people. So why not get some help instead of wasting your time and effort? 5StarEssays.com is here to help you. All your do my essay for me requests are managed by professional essay writers.

Place your order now, and our team of expert academic writers will help you.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the three types of outlines.

Here are the three types of essay outline;

- Working outline

- Speaking outline

- Full-sentence outline

All three types are different from each other and are used for different purposes.

What does a full-sentence outline look like?

A full sentence outline contains full sentences at each level of the essay’s outline. It is similar to an alphanumeric outline and it is a commonly used essay outline.

What is a traditional outline format?

A traditional essay outline begins with writing down all the important points in one place and listing them down and adding sub-topics to them. Besides, it will also include evidence and proof that you will use to back your arguments.

What is the benefit of using a traditional outline format and an informal outline format?

A traditional outline format helps the students in listing down all the important details in one palace while an informal outline will help you coming up with new ideas and highlighting important points

As a Digital Content Strategist, Nova Allison has eight years of experience in writing both technical and scientific content. With a focus on developing online content plans that engage audiences, Nova strives to write pieces that are not only informative but captivating as well.

Was This Blog Helpful?

Keep reading.

- How to Write an Essay - A Complete Guide with Examples

- The Art of Effective Writing: Thesis Statements Examples and Tips

- Writing a 500 Word Essay - Easy Guide

- What is a Topic Sentence - An Easy Guide with Writing Steps & Examples

- 220 Best Transition Words for Essays

- Essay Format: Detailed Writing Tips & Examples

- How to Write a Conclusion - Examples & Tips

- Essay Topics: 100+ Best Essay Topics for your Guidance

- How to Title an Essay: A Step-by-Step Guide for Effective Titles

- How to Write a Perfect 1000 Word Essay

- How To Make An Essay Longer - Easy Guide For Beginners

- Learn How to Start an Essay Effectively with Easy Guidelines

- Types of Sentences With Examples

- Hook Examples: How to Start Your Essay Effectively

- Essay Writing Tips - Essential Do’s and Don’ts to Craft Better Essays

- How To Write A Thesis Statement - A Step by Step Guide

- Art Topics - 200+ Brilliant Ideas to Begin With

- Writing Conventions and Tips for College Students

People Also Read

- essay outline

- essay writing old

- dissertation writing

- writing narrative essay

- informative speech topics

Burdened With Assignments?

Advertisement

- Homework Services: Essay Topics Generator

© 2024 - All rights reserved

Academic Writing

- Introduction

- Planning an Essay

- Basic Essay Structure

Writing an Essay

- Writing Paragraghs

- Plagiarism This link opens in a new window

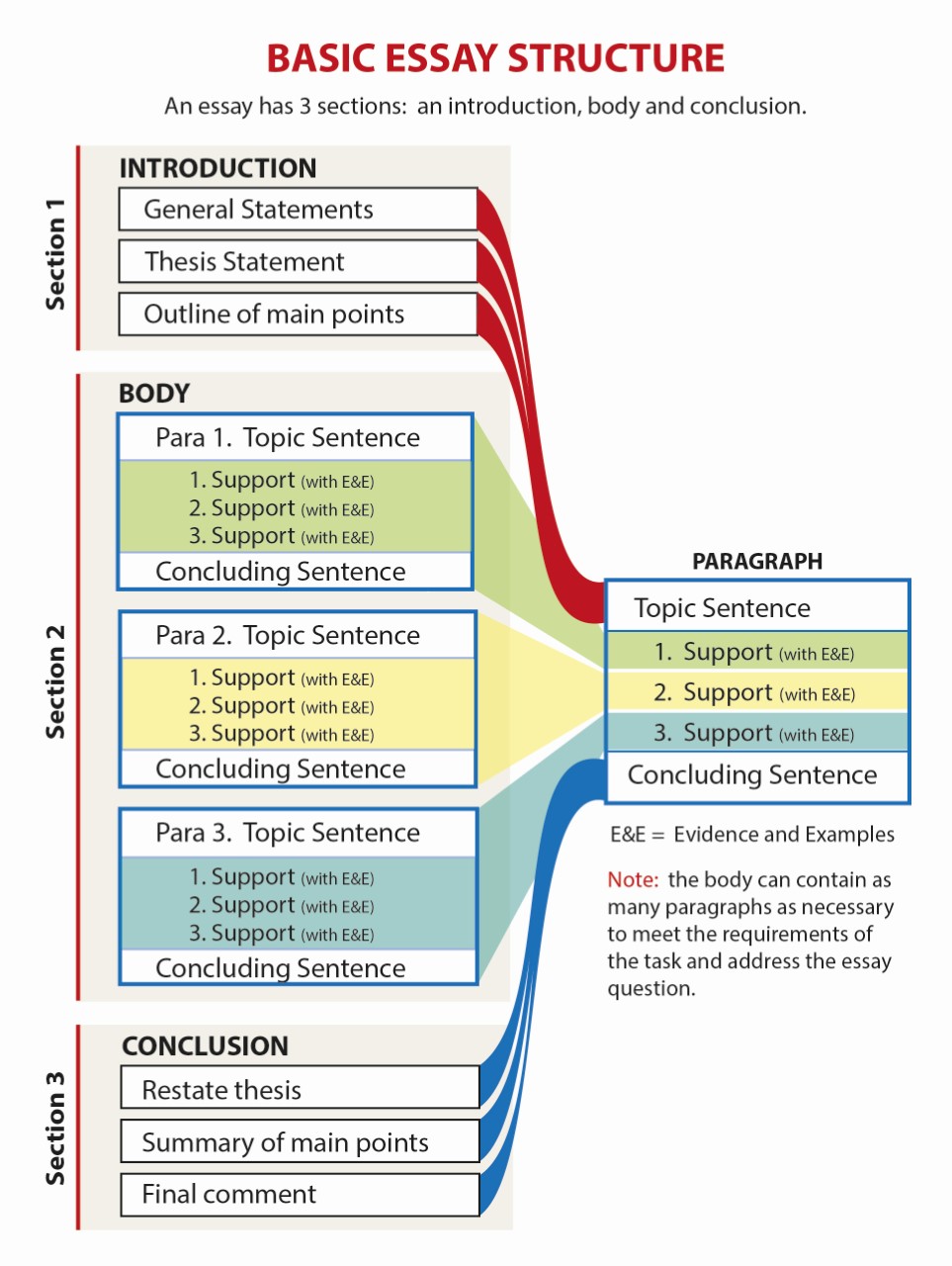

Basic academic essays have three main parts:

- introduction

- Video Explanation

Writing an Introduction

- Section One is a neutral sentence that will engage the reader’s interest in your essay.

- Section Two picks up the topic you are writing about by identifying the issues that you are going to explore.

- Section Three is an indication of how the question will be answered. Give a brief outline of how you will deal with each issue, and in which order.

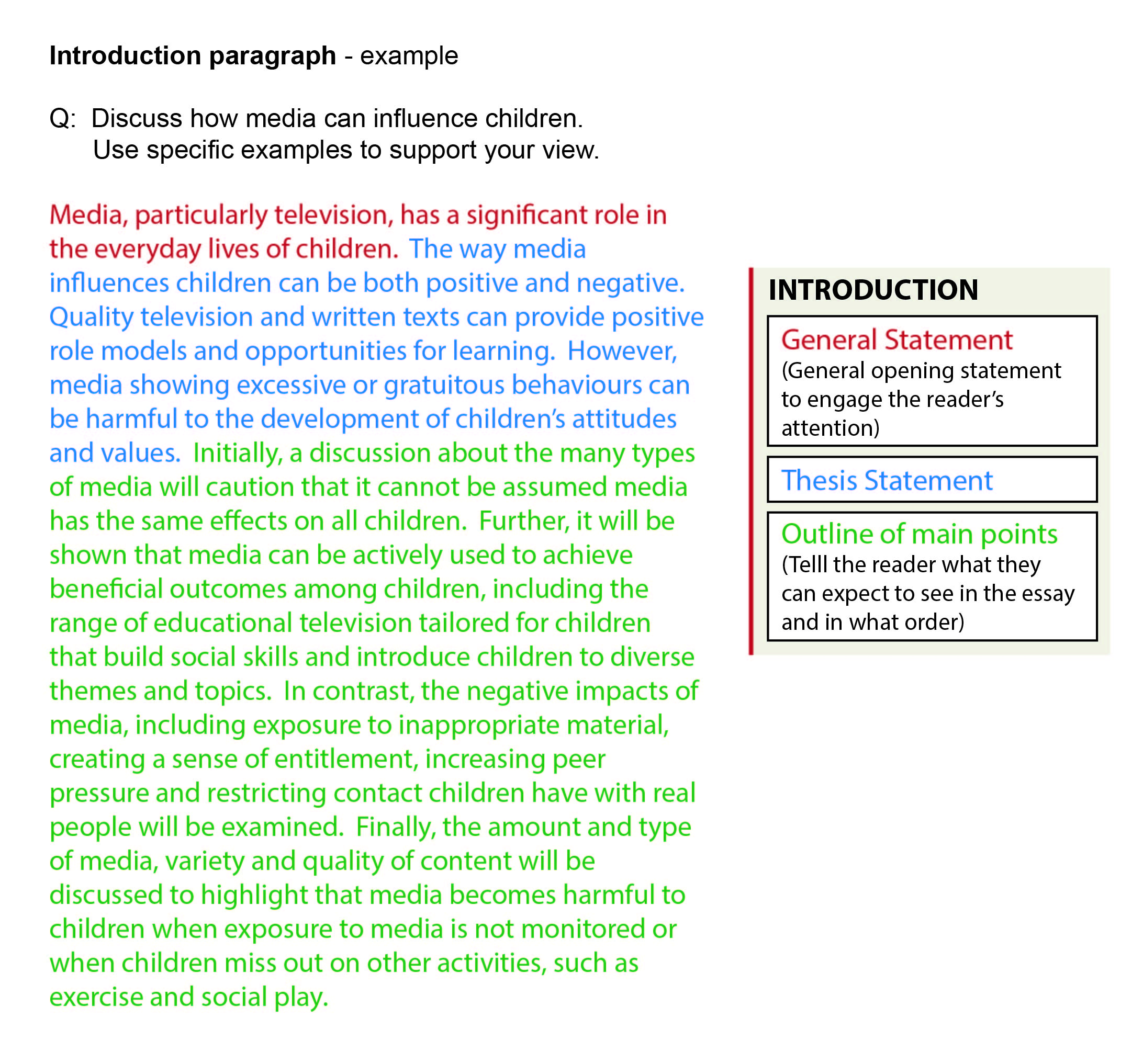

An introduction generally does three things. The first section is usually a general comment that shows the reader why the topic is important, gets their interest, and leads them into the topic. It isn’t actually part of your argument. The next section of the introduction is the thesis statement . This is your response to the question; your final answer. It is probably the most important part of the introduction. Finally, the last section of an introduction tells the reader what they can expect in the essay body. This is where you briefly outline your arguments .

Here is an example of the introduction to the question - Discuss how media can influence children. Use specific examples to support your view.

Writing Body Paragraphs

- The topic sentence introduces the topic of your paragraph.

- The sentences that follow the topic sentence will develop and support the central idea of your topic.

- The concluding sentence of your paragraph restates the idea expressed in the topic sentence.

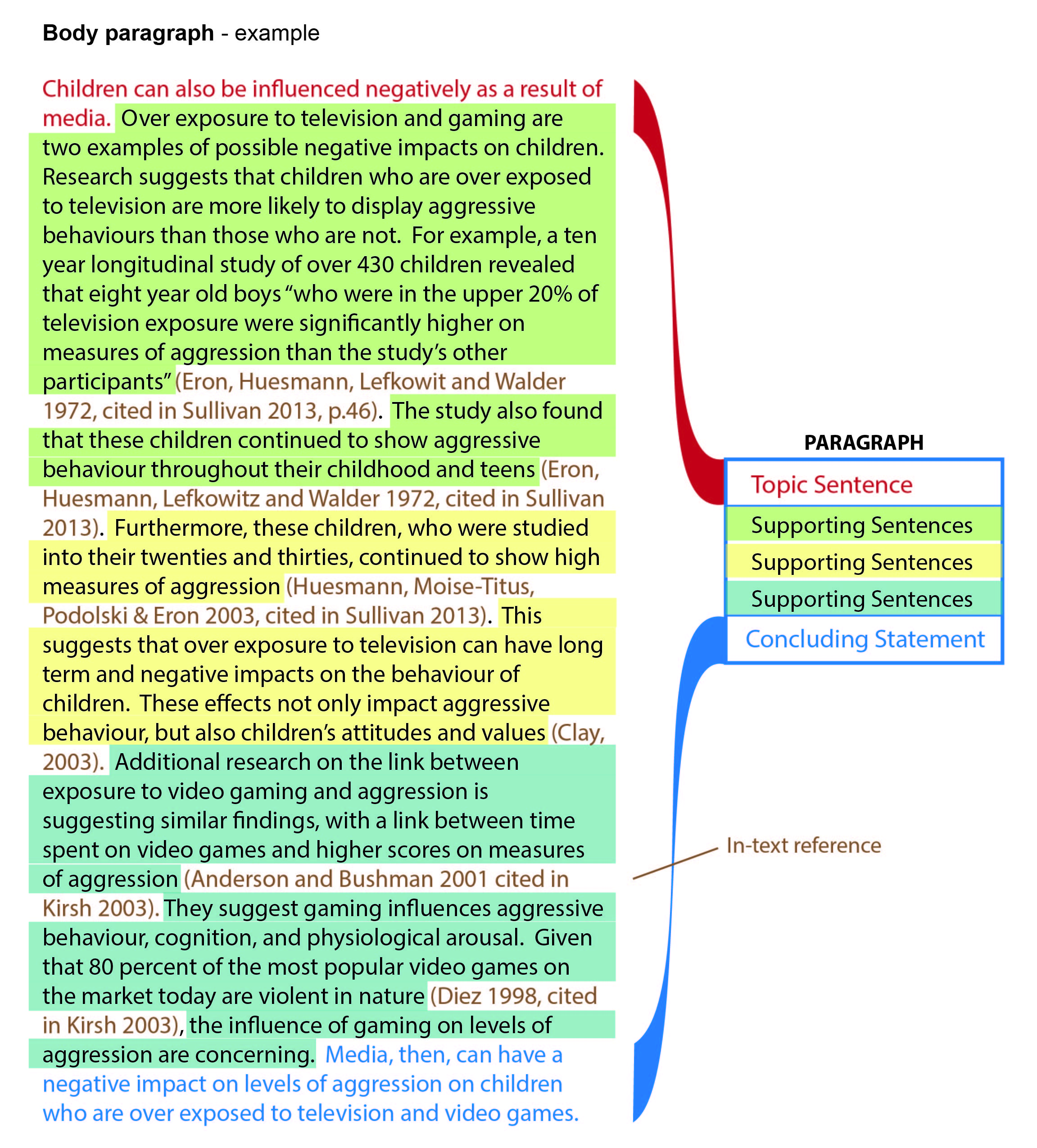

The essay body itself is organized into paragraphs, according to your plan. Remember that each paragraph focuses on one idea, or aspect of your topic, and should contain at least 4-5 sentences so you can deal with that idea properly.

Each body paragraph has three sections. First is the topic sentence . This lets the reader know what the paragraph is going to be about and the main point it will make. It gives the paragraph’s point straight away. Next, come the supporting sentences , which expand on the central idea, explaining it in more detail, exploring what it means, and of course giving the evidence and argument that back it up. This is where you use your research to support your argument. Then there is a concluding sentence . This restates the idea in the topic sentence, to remind the reader of your main point. It also shows how that point helps answer the question.

Writing a Conclusion

- Re-read your introduction – this information will need to be restated in your conclusion emphasizing what you have proven and how you have proven it.

- Begin by summarizing your main arguments and restating your thesis ; e.g. "This essay has considered….."

- State your general conclusions, explaining why these are important.

- The final sentences should draw together the evidence you have presented in the body of the essay to restate your conclusion in an interesting way (use a transitional word to get you started e.g. Overall, Therefore).

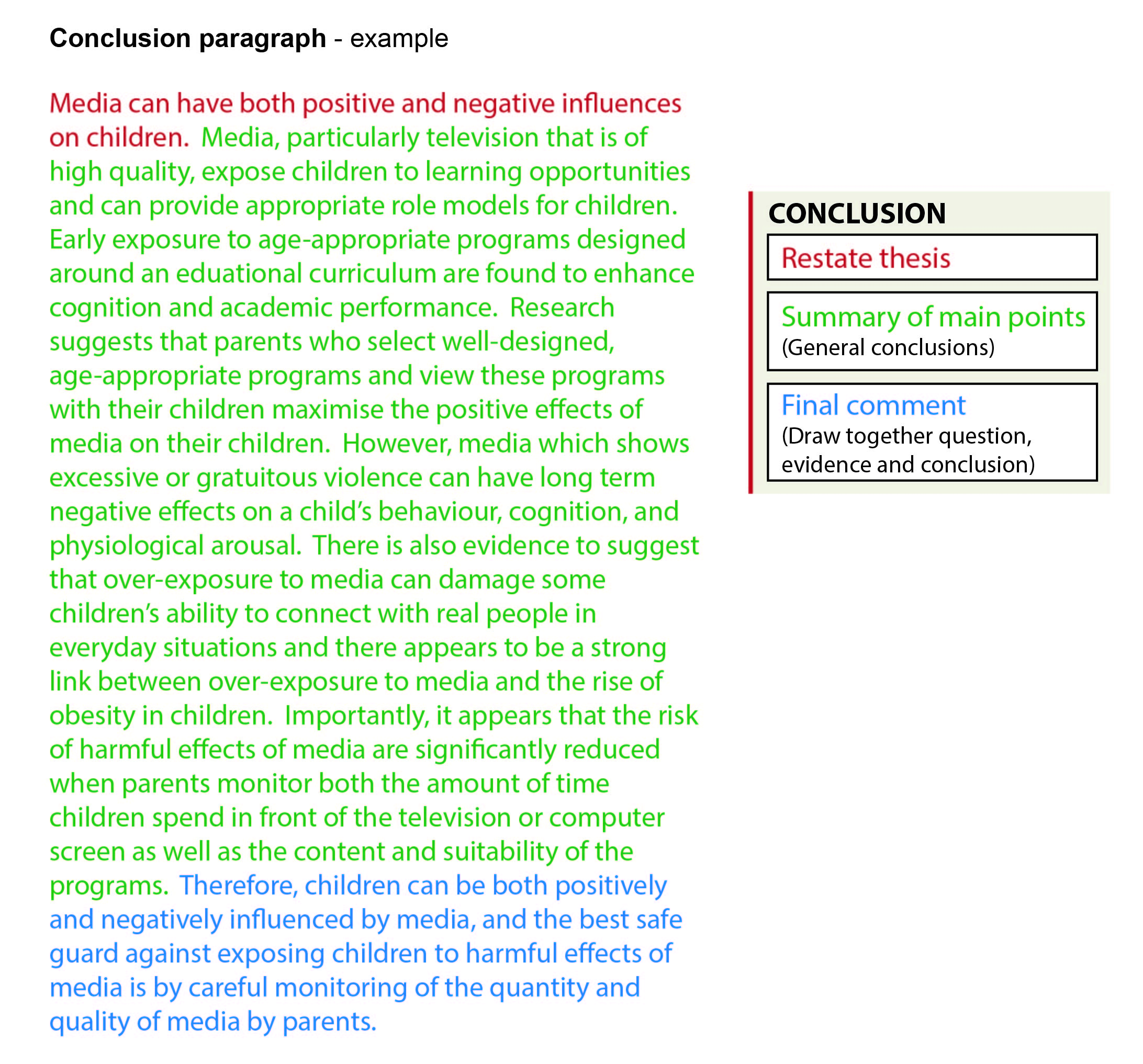

The last section of an academic essay is the conclusion. The conclusion should reaffirm your answer to the question, and briefly summarize key arguments. It does not include any new points or new information.

A conclusion has three sections. First, repeat the thesis statement . It won’t use the exact same words as in your introduction, but it will repeat the point: your overall answer to the question based on your arguments. Then set out your general conclusions , and a short explanation of why they are important. Finally, draw together the question, the evidence in the essay body, and the conclusion. This way the reader knows that you have understood and answered the question. This part needs to be clear and concise.

- << Previous: Planning an Essay

- Next: Writing Paragraghs >>

- Last Updated: Oct 3, 2023 11:15 AM

- URL: https://bcsmn.libguides.com/Academic_Writing

Pasco-Hernando State College

- Parts of an Academic Essay

- The Writing Process

- Rhetorical Modes as Types of Essays

- Stylistic Considerations

- Literary Analysis Essay - Close Reading

- Unity and Coherence in Essays

- Proving the Thesis/Critical Thinking

- Appropriate Language

Test Yourself

- Essay Organization Quiz

- Sample Essay - Fairies

- Sample Essay - Modern Technology

In a way, these academic essays are like a court trial. The attorney, whether prosecuting the case or defending it, begins with an opening statement explaining the background and telling the jury what he or she intends to prove (the thesis statement). Then, the attorney presents witnesses for proof (the body of the paragraphs). Lastly, the attorney presents the closing argument (concluding paragraph).

The Introduction and Thesis

There are a variety of approaches regarding the content of the introduction paragraph such as a brief outline of the proof, an anecdote, explaining key ideas, and asking a question. In addition, some textbooks say that an introduction can be more than one paragraph. The placement of the thesis statement is another variable depending on the instructor and/or text. The approach used in this lesson is that an introduction paragraph gives background information leading into the thesis which is the main idea of the paper, which is stated at the end.

The background in the introductory paragraph consists of information about the circumstances of the thesis. This background information often starts in the introductory paragraph with a general statement which is then refined to the most specific sentence of the essay, the thesis. Background sentences include information about the topic and the controversy. It is important to note that in this approach, the proof for the thesis is not found in the introduction except, possibly, as part of a thesis statement which includes the key elements of the proof. Proof is presented and expanded on in the body.

Some instructors may prefer other types of content in the introduction in addition to the thesis. It is best to check with an instructor as to whether he or she has a preference for content. Generally, the thesis must be stated in the introduction.

The thesis is the position statement. It must contain a subject and a verb and express a complete thought. It must also be defensible. This means it should be an arguable point with which people could reasonably disagree. The more focused and narrow the thesis statement, the better a paper will generally be.

If you are given a question in the instructions for your paper, the thesis statement is a one-sentence answer taking a position on the question.

If you are given a topic instead of a question, then in order to create a thesis statement, you must narrow your analysis of the topic to a specific controversial issue about the topic to take a stand. If it is not a research paper, some brainstorming (jotting down what comes to mind on the issue) should help determine a specific question.

If it is a research paper, the process begins with exploratory research which should show the various issues and controversies which should lead to the specific question. Then, the research becomes focused on the question which in turn should lead to taking a position on the question.

These methods of determining a thesis are still answering a question. It’s just that you pose a question to answer for the thesis. Here is an example.

Suppose, one of the topics you are given to write about is America’s National Parks. Books have been written about this subject. In fact, books have been written just about a single park. As you are thinking about it, you may realize how there is an issue about balancing between preserving the wilderness and allowing visitors. The question would then be Should visitors to America’s National Parks be regulated in order to preserve the wilderness?

One thesis might be There is no need for regulations for visiting America’s National Parks to preserve the wilderness.

Another might be There should be reasonable regulations for visiting America’s National Parks in order to preserve the wilderness.

Finally, avoid using expressions that announce, “Now I will prove…” or “This essay is about …” Instead of telling the reader what the paper is about, a good paper simply proves the thesis in the body. Generally, you shouldn’t refer to your paper in your paper.

Here is an example of a good introduction with the thesis in red:

Not too long ago, everyday life was filled with burdensome, time-consuming chores that left little time for much more than completing these tasks. People generally worked from their homes or within walking distance to their homes and rarely traveled far from them. People were limited to whatever their physical capacities were. All this changed dramatically as new technologies developed. Modern technology has most improved our lives through convenience, efficiency, and accessibility.

Note how the background is general and leads up to the thesis. No proof is given in the background sentences about how technology has improved lives.

Moreover, notice that the thesis in red is the last sentence of the introduction. It is a defensible statement.

A reasonable person could argue the opposite position: Although modern technology has provided easier ways of completing some tasks, it has diminished the quality of life since people have to work too many hours to acquire these gadgets, have developed health problems as a result of excess use, and have lost focus on what is really valuable in life.

Quick Tips:

The introduction opens the essay and gives background information about the thesis.

Do not introduce your supporting points (proof) in the introduction unless they are part of the thesis; save these for the body.

The thesis is placed at the end of the introductory paragraph.

Don’t use expressions like “this paper will be about” or “I intend to show…”

For more information on body paragraphs and supporting evidence, see Proving a Thesis – Evidence and Proving a Thesis – Logic, and Logical Fallacies and Appeals in Related Pages on the right sidebar.

Body paragraphs give proof for the thesis. They should have one proof point per paragraph expressed in a topic sentence. The topic sentence is usually found at the beginning of each body paragraph and, like a thesis, must be a complete sentence. Each topic sentence must be directly related to and support the argument made by the thesis.

After the topic sentence, the rest of the paragraph should go on to support this one proof with examples and explanation. It is the details that support the topic sentences in the body paragraphs that make the arguments strong.

If the thesis statement stated that technology improved the quality of life, each body paragraph should begin with a reason why it has improved the quality of life. This reason is called a topic sentence . Following are three examples of body paragraphs that provide support for the thesis that modern technology has improved our lives through convenience, efficiency, and accessibility:

Almost every aspect of our lives has been improved through convenience provided by modern technology. From the sound of music from an alarm clock in the morning to the end of the day being entertained in the convenience of our living room, our lives are improved. The automatic coffee maker has the coffee ready at a certain time. Cars or public transportation bring people to work where computers operate at the push of a button. At home, there’s the convenience of washing machines and dryers, dishwashers, air conditioners, and power lawn mowers. Modern technology has made life better with many conveniences.

Not only has technology improved our lives through convenience, it has improved our lives through efficiency. The time saved by machines doing most of the work leaves more time for people to develop their personal goals or to just relax. Years ago, when doing laundry could take all day, there wasn’t time left over to read or go to school or even just to take a leisurely walk. Nowadays, people have more time and energy than ever to simply enjoy their lives and pursue their goals thanks to the efficiency of modern technology.