Is Google Making Us Stupid?

What the Internet is doing to our brains

“Dave, stop. Stop, will you? Stop, Dave. Will you stop, Dave?” So the supercomputer HAL pleads with the implacable astronaut Dave Bowman in a famous and weirdly poignant scene toward the end of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey . Bowman, having nearly been sent to a deep-space death by the malfunctioning machine, is calmly, coldly disconnecting the memory circuits that control its artificial “ brain. “Dave, my mind is going,” HAL says, forlornly. “I can feel it. I can feel it.”

I can feel it, too. Over the past few years I’ve had an uncomfortable sense that someone, or something, has been tinkering with my brain, remapping the neural circuitry, reprogramming the memory. My mind isn’t going—so far as I can tell—but it’s changing. I’m not thinking the way I used to think. I can feel it most strongly when I’m reading. Immersing myself in a book or a lengthy article used to be easy. My mind would get caught up in the narrative or the turns of the argument, and I’d spend hours strolling through long stretches of prose. That’s rarely the case anymore. Now my concentration often starts to drift after two or three pages. I get fidgety, lose the thread, begin looking for something else to do. I feel as if I’m always dragging my wayward brain back to the text. The deep reading that used to come naturally has become a struggle.

I think I know what’s going on. For more than a decade now, I’ve been spending a lot of time online, searching and surfing and sometimes adding to the great databases of the Internet. The Web has been a godsend to me as a writer. Research that once required days in the stacks or periodical rooms of libraries can now be done in minutes. A few Google searches, some quick clicks on hyperlinks, and I’ve got the telltale fact or pithy quote I was after. Even when I’m not working, I’m as likely as not to be foraging in the Web’s info-thickets—reading and writing e-mails, scanning headlines and blog posts, watching videos and listening to podcasts, or just tripping from link to link to link. (Unlike footnotes, to which they’re sometimes likened, hyperlinks don’t merely point to related works; they propel you toward them.)

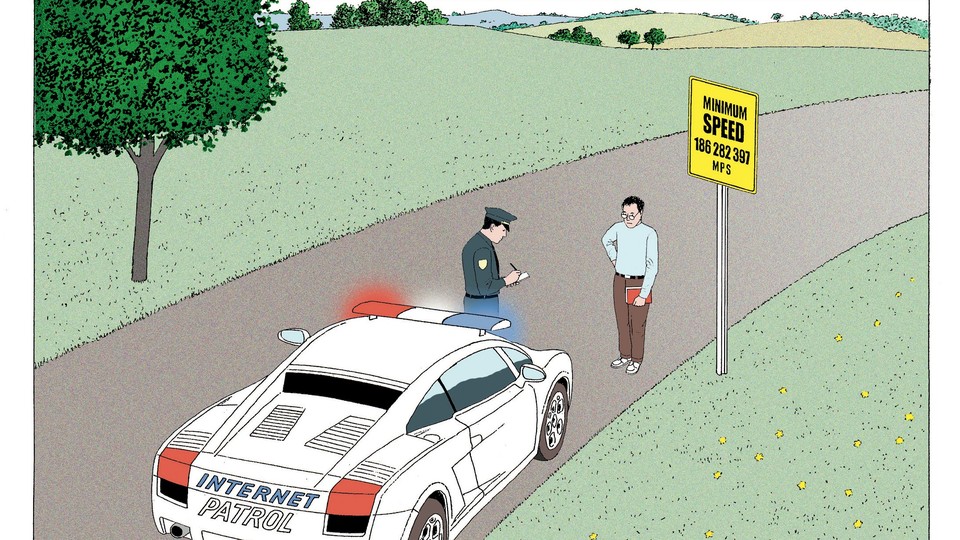

For me, as for others, the Net is becoming a universal medium, the conduit for most of the information that flows through my eyes and ears and into my mind. The advantages of having immediate access to such an incredibly rich store of information are many, and they’ve been widely described and duly applauded. “The perfect recall of silicon memory,” Wired ’s Clive Thompson has written , “can be an enormous boon to thinking.” But that boon comes at a price. As the media theorist Marshall McLuhan pointed out in the 1960s, media are not just passive channels of information. They supply the stuff of thought, but they also shape the process of thought. And what the Net seems to be doing is chipping away my capacity for concentration and contemplation. My mind now expects to take in information the way the Net distributes it: in a swiftly moving stream of particles. Once I was a scuba diver in the sea of words. Now I zip along the surface like a guy on a Jet Ski.

I’m not the only one. When I mention my troubles with reading to friends and acquaintances—literary types, most of them—many say they’re having similar experiences. The more they use the Web, the more they have to fight to stay focused on long pieces of writing. Some of the bloggers I follow have also begun mentioning the phenomenon. Scott Karp, who writes a blog about online media , recently confessed that he has stopped reading books altogether. “I was a lit major in college, and used to be [a] voracious book reader,” he wrote. “What happened?” He speculates on the answer: “What if I do all my reading on the web not so much because the way I read has changed, i.e. I’m just seeking convenience, but because the way I THINK has changed?”

Bruce Friedman, who blogs regularly about the use of computers in medicine , also has described how the Internet has altered his mental habits. “I now have almost totally lost the ability to read and absorb a longish article on the web or in print,” he wrote earlier this year. A pathologist who has long been on the faculty of the University of Michigan Medical School, Friedman elaborated on his comment in a telephone conversation with me. His thinking, he said, has taken on a “staccato” quality, reflecting the way he quickly scans short passages of text from many sources online. “I can’t read War and Peace anymore,” he admitted. “I’ve lost the ability to do that. Even a blog post of more than three or four paragraphs is too much to absorb. I skim it.”

Anecdotes alone don’t prove much. And we still await the long-term neurological and psychological experiments that will provide a definitive picture of how Internet use affects cognition. But a recently published study of online research habits, conducted by scholars from University College London, suggests that we may well be in the midst of a sea change in the way we read and think. As part of the five-year research program, the scholars examined computer logs documenting the behavior of visitors to two popular research sites, one operated by the British Library and one by a U.K. educational consortium, that provide access to journal articles, e-books, and other sources of written information. They found that people using the sites exhibited “a form of skimming activity,” hopping from one source to another and rarely returning to any source they’d already visited. They typically read no more than one or two pages of an article or book before they would “bounce” out to another site. Sometimes they’d save a long article, but there’s no evidence that they ever went back and actually read it. The authors of the study report:

It is clear that users are not reading online in the traditional sense; indeed there are signs that new forms of “reading” are emerging as users “power browse” horizontally through titles, contents pages and abstracts going for quick wins. It almost seems that they go online to avoid reading in the traditional sense.

Thanks to the ubiquity of text on the Internet, not to mention the popularity of text-messaging on cell phones, we may well be reading more today than we did in the 1970s or 1980s, when television was our medium of choice. But it’s a different kind of reading, and behind it lies a different kind of thinking—perhaps even a new sense of the self. “We are not only what we read,” says Maryanne Wolf, a developmental psychologist at Tufts University and the author of Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain . “We are how we read.” Wolf worries that the style of reading promoted by the Net, a style that puts “efficiency” and “immediacy” above all else, may be weakening our capacity for the kind of deep reading that emerged when an earlier technology, the printing press, made long and complex works of prose commonplace. When we read online, she says, we tend to become “mere decoders of information.” Our ability to interpret text, to make the rich mental connections that form when we read deeply and without distraction, remains largely disengaged.

Reading, explains Wolf, is not an instinctive skill for human beings. It’s not etched into our genes the way speech is. We have to teach our minds how to translate the symbolic characters we see into the language we understand. And the media or other technologies we use in learning and practicing the craft of reading play an important part in shaping the neural circuits inside our brains. Experiments demonstrate that readers of ideograms, such as the Chinese, develop a mental circuitry for reading that is very different from the circuitry found in those of us whose written language employs an alphabet. The variations extend across many regions of the brain, including those that govern such essential cognitive functions as memory and the interpretation of visual and auditory stimuli. We can expect as well that the circuits woven by our use of the Net will be different from those woven by our reading of books and other printed works.

Sometime in 1882, Friedrich Nietzsche bought a typewriter—a Malling-Hansen Writing Ball, to be precise. His vision was failing, and keeping his eyes focused on a page had become exhausting and painful, often bringing on crushing headaches. He had been forced to curtail his writing, and he feared that he would soon have to give it up. The typewriter rescued him, at least for a time. Once he had mastered touch-typing, he was able to write with his eyes closed, using only the tips of his fingers. Words could once again flow from his mind to the page.

But the machine had a subtler effect on his work. One of Nietzsche’s friends, a composer, noticed a change in the style of his writing. His already terse prose had become even tighter, more telegraphic. “Perhaps you will through this instrument even take to a new idiom,” the friend wrote in a letter, noting that, in his own work, his “‘thoughts’ in music and language often depend on the quality of pen and paper.”

Recommended Reading

Living with a computer.

How to Trick People Into Saving Money

The Dark Psychology of Social Networks

“You are right,” Nietzsche replied, “our writing equipment takes part in the forming of our thoughts.” Under the sway of the machine, writes the German media scholar Friedrich A. Kittler , Nietzsche’s prose “changed from arguments to aphorisms, from thoughts to puns, from rhetoric to telegram style.”

The human brain is almost infinitely malleable. People used to think that our mental meshwork, the dense connections formed among the 100 billion or so neurons inside our skulls, was largely fixed by the time we reached adulthood. But brain researchers have discovered that that’s not the case. James Olds, a professor of neuroscience who directs the Krasnow Institute for Advanced Study at George Mason University, says that even the adult mind “is very plastic.” Nerve cells routinely break old connections and form new ones. “The brain,” according to Olds, “has the ability to reprogram itself on the fly, altering the way it functions.”

As we use what the sociologist Daniel Bell has called our “intellectual technologies”—the tools that extend our mental rather than our physical capacities—we inevitably begin to take on the qualities of those technologies. The mechanical clock, which came into common use in the 14th century, provides a compelling example. In Technics and Civilization , the historian and cultural critic Lewis Mumford described how the clock “disassociated time from human events and helped create the belief in an independent world of mathematically measurable sequences.” The “abstract framework of divided time” became “the point of reference for both action and thought.”

The clock’s methodical ticking helped bring into being the scientific mind and the scientific man. But it also took something away. As the late MIT computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum observed in his 1976 book, Computer Power and Human Reason: From Judgment to Calculation , the conception of the world that emerged from the widespread use of timekeeping instruments “remains an impoverished version of the older one, for it rests on a rejection of those direct experiences that formed the basis for, and indeed constituted, the old reality.” In deciding when to eat, to work, to sleep, to rise, we stopped listening to our senses and started obeying the clock.

The process of adapting to new intellectual technologies is reflected in the changing metaphors we use to explain ourselves to ourselves. When the mechanical clock arrived, people began thinking of their brains as operating “like clockwork.” Today, in the age of software, we have come to think of them as operating “like computers.” But the changes, neuroscience tells us, go much deeper than metaphor. Thanks to our brain’s plasticity, the adaptation occurs also at a biological level.

The Internet promises to have particularly far-reaching effects on cognition. In a paper published in 1936 , the British mathematician Alan Turing proved that a digital computer, which at the time existed only as a theoretical machine, could be programmed to perform the function of any other information-processing device. And that’s what we’re seeing today. The Internet, an immeasurably powerful computing system, is subsuming most of our other intellectual technologies. It’s becoming our map and our clock, our printing press and our typewriter, our calculator and our telephone, and our radio and TV.

When the Net absorbs a medium, that medium is re-created in the Net’s image. It injects the medium’s content with hyperlinks, blinking ads, and other digital gewgaws, and it surrounds the content with the content of all the other media it has absorbed. A new e-mail message, for instance, may announce its arrival as we’re glancing over the latest headlines at a newspaper’s site. The result is to scatter our attention and diffuse our concentration.

The Net’s influence doesn’t end at the edges of a computer screen, either. As people’s minds become attuned to the crazy quilt of Internet media, traditional media have to adapt to the audience’s new expectations. Television programs add text crawls and pop-up ads, and magazines and newspapers shorten their articles, introduce capsule summaries, and crowd their pages with easy-to-browse info-snippets. When, in March of this year, The New York Times decided to devote the second and third pages of every edition to article abstracts , its design director, Tom Bodkin, explained that the “shortcuts” would give harried readers a quick “taste” of the day’s news, sparing them the “less efficient” method of actually turning the pages and reading the articles. Old media have little choice but to play by the new-media rules.

Never has a communications system played so many roles in our lives—or exerted such broad influence over our thoughts—as the Internet does today. Yet, for all that’s been written about the Net, there’s been little consideration of how, exactly, it’s reprogramming us. The Net’s intellectual ethic remains obscure.

About the same time that Nietzsche started using his typewriter, an earnest young man named Frederick Winslow Taylor carried a stopwatch into the Midvale Steel plant in Philadelphia and began a historic series of experiments aimed at improving the efficiency of the plant’s machinists. With the approval of Midvale’s owners, he recruited a group of factory hands, set them to work on various metalworking machines, and recorded and timed their every movement as well as the operations of the machines. By breaking down every job into a sequence of small, discrete steps and then testing different ways of performing each one, Taylor created a set of precise instructions—an “algorithm,” we might say today—for how each worker should work. Midvale’s employees grumbled about the strict new regime, claiming that it turned them into little more than automatons, but the factory’s productivity soared.

More than a hundred years after the invention of the steam engine, the Industrial Revolution had at last found its philosophy and its philosopher. Taylor’s tight industrial choreography—his “system,” as he liked to call it—was embraced by manufacturers throughout the country and, in time, around the world. Seeking maximum speed, maximum efficiency, and maximum output, factory owners used time-and-motion studies to organize their work and configure the jobs of their workers. The goal, as Taylor defined it in his celebrated 1911 treatise, The Principles of Scientific Management , was to identify and adopt, for every job, the “one best method” of work and thereby to effect “the gradual substitution of science for rule of thumb throughout the mechanic arts.” Once his system was applied to all acts of manual labor, Taylor assured his followers, it would bring about a restructuring not only of industry but of society, creating a utopia of perfect efficiency. “In the past the man has been first,” he declared; “in the future the system must be first.”

Taylor’s system is still very much with us; it remains the ethic of industrial manufacturing. And now, thanks to the growing power that computer engineers and software coders wield over our intellectual lives, Taylor’s ethic is beginning to govern the realm of the mind as well. The Internet is a machine designed for the efficient and automated collection, transmission, and manipulation of information, and its legions of programmers are intent on finding the “one best method”—the perfect algorithm—to carry out every mental movement of what we’ve come to describe as “knowledge work.”

Google’s headquarters, in Mountain View, California—the Googleplex—is the Internet’s high church, and the religion practiced inside its walls is Taylorism. Google, says its chief executive, Eric Schmidt, is “a company that’s founded around the science of measurement,” and it is striving to “systematize everything” it does. Drawing on the terabytes of behavioral data it collects through its search engine and other sites, it carries out thousands of experiments a day, according to the Harvard Business Review , and it uses the results to refine the algorithms that increasingly control how people find information and extract meaning from it. What Taylor did for the work of the hand, Google is doing for the work of the mind.

The company has declared that its mission is “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” It seeks to develop “the perfect search engine,” which it defines as something that “understands exactly what you mean and gives you back exactly what you want.” In Google’s view, information is a kind of commodity, a utilitarian resource that can be mined and processed with industrial efficiency. The more pieces of information we can “access” and the faster we can extract their gist, the more productive we become as thinkers.

Where does it end? Sergey Brin and Larry Page, the gifted young men who founded Google while pursuing doctoral degrees in computer science at Stanford, speak frequently of their desire to turn their search engine into an artificial intelligence, a HAL-like machine that might be connected directly to our brains. “The ultimate search engine is something as smart as people—or smarter,” Page said in a speech a few years back. “For us, working on search is a way to work on artificial intelligence.” In a 2004 interview with Newsweek , Brin said, “Certainly if you had all the world’s information directly attached to your brain, or an artificial brain that was smarter than your brain, you’d be better off.” Last year, Page told a convention of scientists that Google is “really trying to build artificial intelligence and to do it on a large scale.”

Such an ambition is a natural one, even an admirable one, for a pair of math whizzes with vast quantities of cash at their disposal and a small army of computer scientists in their employ. A fundamentally scientific enterprise, Google is motivated by a desire to use technology, in Eric Schmidt’s words, “to solve problems that have never been solved before,” and artificial intelligence is the hardest problem out there. Why wouldn’t Brin and Page want to be the ones to crack it?

Still, their easy assumption that we’d all “be better off” if our brains were supplemented, or even replaced, by an artificial intelligence is unsettling. It suggests a belief that intelligence is the output of a mechanical process, a series of discrete steps that can be isolated, measured, and optimized. In Google’s world, the world we enter when we go online, there’s little place for the fuzziness of contemplation. Ambiguity is not an opening for insight but a bug to be fixed. The human brain is just an outdated computer that needs a faster processor and a bigger hard drive.

The idea that our minds should operate as high-speed data-processing machines is not only built into the workings of the Internet, it is the network’s reigning business model as well. The faster we surf across the Web—the more links we click and pages we view—the more opportunities Google and other companies gain to collect information about us and to feed us advertisements. Most of the proprietors of the commercial Internet have a financial stake in collecting the crumbs of data we leave behind as we flit from link to link—the more crumbs, the better. The last thing these companies want is to encourage leisurely reading or slow, concentrated thought. It’s in their economic interest to drive us to distraction.

Maybe I’m just a worrywart. Just as there’s a tendency to glorify technological progress, there’s a countertendency to expect the worst of every new tool or machine. In Plato’s Phaedrus , Socrates bemoaned the development of writing. He feared that, as people came to rely on the written word as a substitute for the knowledge they used to carry inside their heads, they would, in the words of one of the dialogue’s characters, “cease to exercise their memory and become forgetful.” And because they would be able to “receive a quantity of information without proper instruction,” they would “be thought very knowledgeable when they are for the most part quite ignorant.” They would be “filled with the conceit of wisdom instead of real wisdom.” Socrates wasn’t wrong—the new technology did often have the effects he feared—but he was shortsighted. He couldn’t foresee the many ways that writing and reading would serve to spread information, spur fresh ideas, and expand human knowledge (if not wisdom).

The arrival of Gutenberg’s printing press, in the 15th century, set off another round of teeth gnashing. The Italian humanist Hieronimo Squarciafico worried that the easy availability of books would lead to intellectual laziness, making men “less studious” and weakening their minds. Others argued that cheaply printed books and broadsheets would undermine religious authority, demean the work of scholars and scribes, and spread sedition and debauchery. As New York University professor Clay Shirky notes, “Most of the arguments made against the printing press were correct, even prescient.” But, again, the doomsayers were unable to imagine the myriad blessings that the printed word would deliver.

So, yes, you should be skeptical of my skepticism. Perhaps those who dismiss critics of the Internet as Luddites or nostalgists will be proved correct, and from our hyperactive, data-stoked minds will spring a golden age of intellectual discovery and universal wisdom. Then again, the Net isn’t the alphabet, and although it may replace the printing press, it produces something altogether different. The kind of deep reading that a sequence of printed pages promotes is valuable not just for the knowledge we acquire from the author’s words but for the intellectual vibrations those words set off within our own minds. In the quiet spaces opened up by the sustained, undistracted reading of a book, or by any other act of contemplation, for that matter, we make our own associations, draw our own inferences and analogies, foster our own ideas. Deep reading , as Maryanne Wolf argues, is indistinguishable from deep thinking.

If we lose those quiet spaces, or fill them up with “content,” we will sacrifice something important not only in our selves but in our culture. In a recent essay , the playwright Richard Foreman eloquently described what’s at stake:

I come from a tradition of Western culture, in which the ideal (my ideal) was the complex, dense and “cathedral-like” structure of the highly educated and articulate personality—a man or woman who carried inside themselves a personally constructed and unique version of the entire heritage of the West. [But now] I see within us all (myself included) the replacement of complex inner density with a new kind of self—evolving under the pressure of information overload and the technology of the “instantly available.”

As we are drained of our “inner repertory of dense cultural inheritance,” Foreman concluded, we risk turning into “‘pancake people’—spread wide and thin as we connect with that vast network of information accessed by the mere touch of a button.”

I’m haunted by that scene in 2001 . What makes it so poignant, and so weird, is the computer’s emotional response to the disassembly of its mind: its despair as one circuit after another goes dark, its childlike pleading with the astronaut—“I can feel it. I can feel it. I’m afraid”—and its final reversion to what can only be called a state of innocence. HAL’s outpouring of feeling contrasts with the emotionlessness that characterizes the human figures in the film, who go about their business with an almost robotic efficiency. Their thoughts and actions feel scripted, as if they’re following the steps of an algorithm. In the world of 2001 , people have become so machinelike that the most human character turns out to be a machine. That’s the essence of Kubrick’s dark prophecy: as we come to rely on computers to mediate our understanding of the world, it is our own intelligence that flattens into artificial intelligence.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic .

Is Google Making Us Stupid Summary, Purpose and Analysis

“Is Google Making Us Stupid?” is an article by Nicholas Carr, delving into the impacts of the internet on our cognitive abilities.

Carr explores how his own mind has changed, noting a decline in his capacity for concentration and deep reading. He attributes this to his extensive online activities, which have reshaped his thinking patterns to align more with the rapid, skimming nature of web browsing.

Full Summary

Carr isn’t alone in his experience.

He mentions friends and acquaintances, including literary types and bloggers, who share similar struggles with focusing on lengthy texts. The phenomenon isn’t just anecdotal; research backs it up.

A study from University College London found that online reading often involves skimming rather than in-depth exploration, with people hopping between sources without fully engaging with any of them.

The article dives into the history of reading and its evolution, discussing how technologies like the printing press and now the internet have changed our approach to reading and, by extension, our thinking.

Carr draws on the perspectives of experts like Maryanne Wolf, who argues that the internet promotes a more superficial form of reading, impacting our ability to think deeply and make rich mental connections.

Carr also touches upon historical figures like Nietzsche, who experienced a change in his writing style after starting to use a typewriter. This example illustrates how new technologies can subtly influence our cognitive processes.

The broader implications of this shift are significant. As we increasingly rely on the internet for information, our minds adapt to its rapid, interruptive nature, potentially diminishing our capacity for contemplation and reflection.

Carr suggests that this change might lead to a broader societal impact, where deep, critical thinking becomes less common, and we become more like “pancake people” – spread wide and thin in our knowledge and understanding.

In conclusion, Carr’s article raises important questions about the cognitive effects of the internet.

While acknowledging the immense benefits of easy access to information, he urges us to consider what might be lost in this trade-off – the depth and richness of thought that comes from deep, uninterrupted reading and contemplation.

The purpose of the article is multifaceted and centers around exploring the impact of the Internet, particularly search engines like Google, on our cognitive processes, particularly our ability to concentrate, comprehend, and engage in deep thinking.

The article serves several key functions, some of them being –

1. Raising Awareness about Cognitive Changes

Carr aims to draw attention to a subtle but profound shift in how our minds function due to prolonged exposure to the Internet. He shares personal experiences and observations to illustrate how our ability to concentrate and immerse ourselves in deep reading is diminishing.

By doing so, he encourages readers to reflect on their cognitive experiences and recognize similar patterns in their behavior.

2. Stimulating Intellectual Discourse

The article is a springboard for broader discussion about the nature of intelligence, reading, and learning in the digital age.

Carr doesn’t just present a personal dilemma but taps into a larger cultural and intellectual concern, inviting readers, educators, and scholars to ponder the implications of our growing dependency on digital technology for information processing.

3. Reviewing and Interpreting Research and Theories

Carr integrates research findings and theories from various fields, including neuroscience, psychology , and media studies, to provide a scientific basis for his arguments.

He references studies and experts to suggest that the Internet’s structure and use patterns significantly influence our neural pathways, affecting our memory, attention spans, and even the depth of our thinking.

4. Historical Contextualization

The article places the current technological shift in a historical context, comparing the Internet’s impact on our cognitive abilities to that of previous technologies, such as the clock and the printing press.

Carr uses historical analogies to show that while new technologies often bring significant benefits, they can also have unintended consequences for how we think and process information.

5. Provoking a Reevaluation of Our Relationship with Technology

Carr’s article serves as a call to critically assess our relationship with digital technology. He encourages readers to consider how their interactions with the Internet might be shaping their mental habits and to ponder if this influence is entirely beneficial.

6. Ethical and Philosophical Implications

The article also delves into the ethical and philosophical implications of allowing technology to mediate our understanding of the world.

Carr reflects on the potential loss of certain cognitive abilities and the broader impact this could have on culture, creativity, and the human experience.

7. Encouraging Mindful Engagement with Technology

Ultimately, Carr’s article is a plea for mindful and balanced engagement with technology.

While recognizing the immense benefits of the Internet, he advocates for a more conscious approach to how we use digital tools, suggesting that we should strive to preserve and cultivate our capacity for deep thought and contemplation.

Themes

1. the transformation of reading habits and cognitive processes.

At the heart of Nicholas Carr’s exploration is the profound transformation in how we read and process information in the digital age.

Carr delves into the subtle yet significant shift from deep, immersive reading of printed materials to the skimming and scanning habits fostered by the internet. This theme is not just a commentary on changing reading habits but a deeper inquiry into the cognitive consequences of such a shift.

He reflects on his own experiences, noting a decreased ability to engage in prolonged, focused reading, which once came naturally.

This change is attributed to the constant, rapid-fire consumption of information online, leading to a fragmented attention span.

Carr’s discussion extends beyond personal anecdotes, incorporating research findings that support the notion of diminishing depth in our reading and thinking patterns due to the internet’s influence.

2. The Impact of Technology on Mental Processes and Creativity

Another significant theme in Carr’s article is the broader impact of technology, specifically the internet, on our mental processes and creativity.

He raises concerns about the internet’s role in reshaping our thinking patterns, aligning them more with its non-linear, hyperlinked structure. This restructuring of thought processes is not just about how we seek and absorb information; it reaches into the realms of creativity and problem-solving.

Carr invokes historical parallels, drawing on Nietzsche’s experience with the typewriter to illustrate how new technologies can subtly but fundamentally alter our cognitive styles.

This theme is further enriched by references to various studies and experts, like Patricia Greenfield, who suggest that while certain cognitive abilities, like visual-spatial skills, are enhanced by digital media, this comes at the expense of more traditional, deeper cognitive skills such as reflective thought, critical thinking, and sustained attention.

3. The Dichotomy between Efficiency and Depth in the Digital Era

Carr navigates the complex dichotomy between the efficiency provided by the internet and the potential loss of depth in our thinking. This theme is woven throughout the article, contrasting the immediate, vast access to information against the possible erosion of our capacity for deep contemplation and critical analysis.

Carr posits that while the internet acts as a powerful tool for quick information retrieval and processing, this rapid and efficient access might be undermining our ability to engage in more profound, contemplative thought processes.

He questions whether the trade-off between the speed of information access and the richness of our intellectual life is worth it, suggesting that the convenience of the internet could be leading us to a more superficial understanding of the world around us.

This theme is crucial as it encapsulates the broader societal implications of our growing dependency on digital technologies, prompting a reflection on what we gain and what we might be inadvertently sacrificing in the digital age.

Arguments and Evidence

- Personal Anecdotes : Carr begins with a personal anecdote, a rhetorical strategy that makes his argument relatable. He confesses his own struggles with concentration and deep reading, which he attributes to his internet usage.

- Historical References : He cites historical instances (like Nietzsche’s use of a typewriter) to illustrate how new technologies can subtly influence thinking and writing styles.

- Scientific Research : Carr references various studies and experts (like Maryanne Wolf and Bruce Friedman) to support his claims about the internet’s impact on our cognitive functions.

- Philosophical and Cultural Reflections : He integrates philosophical and cultural perspectives, discussing how different technologies have historically influenced human thought and culture.

- Introduction : Carr opens with a reference to Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey” as a metaphor for his argument. This draws the reader in with a familiar cultural reference.

- Development of Argument : The article unfolds systematically, beginning with personal observations, then moving to broader social implications and scientific evidence.

- Conclusion : Carr concludes by reflecting on the implications of these changes, leaving the reader with questions about the role of technology in our lives.

Strengths and Weaknesses

- Engaging Narrative : Carr’s use of personal and historical anecdotes makes the article engaging and relatable.

- Interdisciplinary Approach : He incorporates insights from neuroscience, psychology, history, and culture, providing a well-rounded argument.

- Provocative and Thought-Provoking : The article successfully provokes deeper thought about our relationship with technology.

- Subjectivity : The heavy reliance on personal anecdotes may lead to questions about the universality of his experiences.

- Potential for Technological Determinism : Some might argue that Carr leans towards a deterministic view of technology, underestimating human agency in adapting to and shaping technological uses.

Overall Impact

Carr’s article is a significant contribution to the discourse on the internet’s impact on human cognition.

It challenges readers to critically assess their interactions with digital technology and consider the broader implications for society and culture.

While it raises more questions than it answers, it serves as a catalyst for further exploration and discussion on the role of technology in shaping our minds and lives.

Sharing is Caring!

A team of Editors at Books That Slay.

Passionate | Curious | Permanent Bibliophiles

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Is Google Making Us Stupid?

24 pages • 48 minutes read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Essay Analysis

Key Figures

Symbols & Motifs

Literary Devices

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Essay Analysis Story Analysis

Analysis: “is google making us stupid”.

In this essay, Carr asserts that the Internet, rather than Google specifically or exclusively, is in the process of revolutionizing human consciousness and cognition. For Carr, this is a negative revolution that threatens to evacuate human intellectual inquiry of its nuance, and to squeeze human interactions with both complex ideas and our own intellectual lives into a dangerously oversimplified mechanism designed only to create productivity and efficiency: two things that he sees as antithetical to a robust intellectual life.

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Related Titles

By Nicholas Carr

The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains

Nicholas Carr

Featured Collections

Essays & Speeches

View Collection

Rhetoric in “Is Google Making Us Stupid” by Carr Essay

Summary of the essay, carr’s manipulation of words, carr’s use of the ethos, carr’s use of the pathos, carr’s use of the logos, works cited.

Nicholas Carr’s powerful essay called “Is Google Making Us Stupid” is an interesting piece of writing that persuaded readers to take a long and hard look on the Internet’s impact on the human brain. An overview of the essay revealed the application of a careful appeal to the reader’s emotions, the establishment of the writer’s credibility, logical presentation of relevant information, and the subtle entreaty using shared experiences. After a careful review of the ancient rules of persuasion, it was made clear that Carr utilized an Aristotelian construct characterized by three Latin words – pathos, ethos, and logos – in order to develop a persuasive argument concerning the impact of the Internet on the human brain.

Nicholas Carr made an attempt to persuade readers to reconsider the impact of the Internet on a person’s thought process. His claim was centered on a personal experience in conjunction with the experience of other skilled writers when it came to the way they go through certain mental tasks. This was manifested while in the process of reading books, and the creation of significant literary works that required deep thought and several hours of study.

Carr pointed out the speed and ease of access to information as twin factors that affected the radical changes in the Internet user’s thought process. Carr connected with his readers when he leveraged Marshall McLuhan’s theory on how the medium affects the message (1). He also bolstered his claim when he presented the scientific basis of the brain’s plasticity or the mind’s profound adaptation capabilities (Carr 1).

Aristotle’s strategy of persuasion requires three key elements, and it is defined through the usage and interaction of three Latin words: ethos, pathos, and logos (Killingsworth 26). Ethos, the ancient root word for ethics , defines the importance of the speaker’s character. In other words, the proponent of the persuasive rhetoric must have a clear understanding of the importance of credibility because it is a crucial consideration before speaking in front of an audience (Killingsworth 26).

Pathos, another ancient term, defines the need to connect through shared experiences and human emotions (Killingsworth 26). On the other hand, logos, the third component, defines the importance of the logical presentation of verifiable statements, in order to urge the audience to think hard regarding a certain issue (Killingsworth 26).

Aristotle designed the use of the ethos, pathos, and logos as part of an orator’s arsenal of skills (Killingsworth 26). Therefore, adopting the said strategy in the crafting of an essay required the careful manipulation of words. For example, the author substituted Google for the word Internet.

In the ancient use of ethos, orators relied on costumes and hand gestures to establish an air of credibility. This type of methodology was not accessible to Carr. Thus, he utilized a different tactic to establish his credibility, and he succeeded by convincing his readers regarding his writing capabilities. Carr’s ability to create an essay as a professional writer was made obvious after his name was appended to a world-class organization called The Atlantic . However, for those who did not get the hint, Carr added one anecdote after another, and these were subtle references to his capability as a writer. At one point, he intimated that he spent ten years “searching and surfing and sometimes adding to the great database of the Internet” (Carr 1). He also made the disclosure that he was familiar with the different forms of online content, such as e-mail, blog posts, video, podcasts, and essays found on websites (Carr 1).

A human connection with the readers was made in the essay’s first paragraph. In the introduction section, the author recalled a poignant scene in one of the most popular films of all time. In Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey , Carr found the perfect vehicle to carry the message regarding the abstract idea of the re-arrangement of the mental circuitry within the brain (Carr 1). It was a well-calculated move on the part of the author, because the film’s popularity and subject matter assured the establishment of common ground between the author and his target audience (Killingsworth 26).

He also created a human connection when he used Google as a reference point, even when the technical term for the medium he wanted to focus on was the Internet, and not the world’s most popular search engine. However, he came to realize the fact that when he wrote the word Google, the majority of the readers associated the term to the World Wide Web or the Internet.

Carr developed a four-stage process in the construction of a logical framework supporting his thesis. First, he examined his personal thought process in relation to the way he acquired information. Second, he examined the thought process of his colleagues. He compared how they acquired information before the advent of the Internet, and after they became adept at getting information online. Third, he discussed a popular theoretical framework regarding the impact of mass media on the lives of modern people.

Marshall McLuhan’s “the medium is the message” was a theoretical construct he used. It was useful in understanding how the Internet had affected the way users processed and appreciated the various types of online content available through the World Wide Web. Finally, Carr presented relevant findings in the field of neuroscience that were instrumental in explaining the mental adaptation process that the brain has to go through, when faced with a radically different stimulator or source of information.

Carr’s persuasive argument with regards to the Internet’s effect on the human thought process compelled readers to reconsider how they use the World Wide Web in accessing information online. He persuaded his readers through persuasive arguments based on an ancient framework defined by three Latin words – ethos, pathos, and logos. Carr’s effective application of the concept of “ethos” gave him an opportunity to present his argument in a credible manner. He was able to accomplish this task by presenting his credentials as a writer. Carr’s effective use of “pathos” enabled him to establish a human connection with his readers. As a result, his readers felt they were able to relate to his ideas.

Finally, his careful application of the “logos” principle enabled him to skillfully create a four-stage process of arguing the case. He started with his personal experience that served as a way to connect with his readers. This approach also enhanced his credibility with his readers. As a result, readers were made aware of the mind-altering power of the Internet. Carr’s insights came at a critical juncture when human beings are no longer interested in books. It is important to take a closer look at the ideas provided by Carr because human being must find out if the long-term impact of using the Internet causes detrimental effects that the global population may soon regret.

Carr, Nicholas. “ Is Google Making Us Stupid? ” The Atlantic . 2008. Web.

Killingsworth, Jimmie. Appeals in Modern Rhetoric . SI University Press, 2005.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, July 30). Rhetoric in “Is Google Making Us Stupid” by Carr. https://ivypanda.com/essays/rhetoric-in-is-google-making-us-stupid-by-carr/

"Rhetoric in “Is Google Making Us Stupid” by Carr." IvyPanda , 30 July 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/rhetoric-in-is-google-making-us-stupid-by-carr/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Rhetoric in “Is Google Making Us Stupid” by Carr'. 30 July.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Rhetoric in “Is Google Making Us Stupid” by Carr." July 30, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/rhetoric-in-is-google-making-us-stupid-by-carr/.

1. IvyPanda . "Rhetoric in “Is Google Making Us Stupid” by Carr." July 30, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/rhetoric-in-is-google-making-us-stupid-by-carr/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Rhetoric in “Is Google Making Us Stupid” by Carr." July 30, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/rhetoric-in-is-google-making-us-stupid-by-carr/.

- Views on Internet and the Human Brain by Nicholas Carr

- “The Twenty Years' Crisis 1919-1939” by E. Carr

- Emily Carr’s Legacy in Canadian Art History

- Rhetorical Situations: Ethos, Pathos, Logos

- Public Speaking in Ancient Greece and Roman Empire

- Syllogism and Enthymeme in Aristotle's Rhetoric

- Marketing in an Unpredictable World: Logos, Pathos, and Ethos

- Immigration in Trump’s Candidate Speech

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Author Interviews

'the shallows': this is your brain online.

Try reading a book while doing a crossword puzzle, and that, says author Nicholas Carr, is what you're doing every time you use the Internet.

Carr is the author of the Atlantic article Is Google Making Us Stupid? which he has expanded into a book, The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains.

Carr believes that the Internet is a medium based on interruption -- and it's changing the way people read and process information. We've come to associate the acquisition of wisdom with deep reading and solitary concentration, and he says there's not much of that to be found online.

Chronic Distraction

Carr started research for The Shallows after he noticed a change in his own ability to concentrate.

"I'd sit down with a book, or a long article," he tells NPR's Robert Siegel, "and after a couple of pages my brain wanted to do what it does when I'm online: check e-mail, click on links, do some Googling, hop from page to page."

The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains By Nicholas Carr Hardcover, 276 pages W.W. Norton & Co. List price: $26.95

This chronic state of distraction "follows us" Carr argues, long after we shut down our computers.

"Neuroscientists and psychologists have discovered that, even as adults, our brains are very plastic," Carr explains. "They're very malleable, they adapt at the cellular level to whatever we happen to be doing. And so the more time we spend surfing, and skimming, and scanning ... the more adept we become at that mode of thinking."

Would You Process This Information Better On Paper?

The book cites many studies that indicate that online reading yields lower comprehension than reading from a printed page. Then again, reading online is a relatively recent phenomenon, and a generation of readers who grow up consuming everything on the screen may simply be more adept at online reading than people who were forced to switch from print.

Still, Carr argues that even if people get better at hopping from page to page, they will still be losing their abilities to employ a "slower, more contemplative mode of thought." He says research shows that as people get better at multitasking, they "become less creative in their thinking."

The idea that the brain is a kind of zero sum game -- that the ability to read incoming text messages is somehow diminishing our ability to read Moby Dick -- is not altogether self-evident. Why can't the mind simply become better at a whole variety of intellectual tasks?

Carr says it really has to do with practice. The reality -- especially for young people -- is that online time is "crowding out" the time that might otherwise be spent in prolonged, focused concentration.

"We're seeing this medium, the medium of the Web, in effect replace the time that we used to spend in different modes of thinking," Carr says.

Nicholas Carr is also the author of The Big Switch: Rewiring the World, from Edison to Google and Does IT Matter? He blogs at Rough Type . Joanie Simon hide caption

Nicholas Carr is also the author of The Big Switch: Rewiring the World, from Edison to Google and Does IT Matter? He blogs at Rough Type .

The Natural State Of Things?

Carr admits he's something of a fatalist when it comes to technology. He views the advent of the Internet as "not just technological progress but a form of human regress."

Human ancestors had to stay alert and shift their attention all the time; cavemen who got too wrapped up in their cave paintings just didn't survive. Carr acknowledges that prolonged, solitary thought is not the natural human state, but rather "an aberration in the great sweep of intellectual history that really just emerged with [the] technology of the printed page."

The Internet, Carr laments, simply returns us to our "natural state of distractedness."

The Shallows

Buy featured book.

Your purchase helps support NPR programming. How?

- Independent Bookstores

Excerpt: 'The Shallows'

Nicholas Carr's blog

“is google making us stupid”: sources and notes.

Since the publication of my essay Is Google Making Us Stupid? in The Atlantic, I’ve received several requests for pointers to sources and related readings. I’ve tried to round them up below.

The essay builds on my book The Big Switch: Rewiring the World, from Edison to Google, particularly the final chapter, “iGod.” The essential theme of both the essay and the book – that our technologies change us, often in ways we can neither anticipate nor control – is one that was frequently, and deeply, discussed during the last century, in books and articles by such thinkers as Lewis Mumford, Eric A. Havelock, J. Z. Young, Marshall McLuhan, and Walter J. Ong.

The screenplay for the film 2001: A Space Odyssey was written by Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke. Clarke’s book 2001 , a lesser work than the film, was based on the screenplay rather than vice versa.

Scott Karp’s blog post about how he’s lost his capacity to read books can be found here , and Bruce Friedman’s post can be found here . Both Karp and Friedman believe that what they’ve gained from the Internet outweighs what they’ve lost. An overview of the University of College London study of the behavior of online researchers, “Information Behaviour of

the Researcher of the Future,” is here . Maryanne Wolf’s fascinating Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain was published last year by Harpercollins.

I found the story of Friedrich Nietzsche’s typewriter in J. C. Nyíri’s essay Thinking with a Word Processor as well as Friedrich A. Kittler’s winningly idiosyncratic Gramophone, Film, Typewriter and Darren Wershler-Henry’s history of the typewriter, The Iron Whim .

Lewis Mumford discusses the impact of the mechanical clock in his 1934 Technics and Civilization . See also Mumford’s later two-volume study The Myth of the Machine . Joseph Weizenbaum’s Computer Power and Human Reason remains one of the most thoughtful books written about the human implications of computing. Weizenbaum died earlier this year, and I wrote a brief appreciation of him here .

Alan Turing’s 1936 paper on the universal computer was titled On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem . Tom Bodkin’s explanation of the New York Times ‘s design changes came in this Slate interview with Jack Shafer.

For Frederick Winslow Taylor’s story, I drew on Robert Kanigel’s biography The One Best Way and Taylor’s own The Principles of Scientific Management .

Eric Schmidt made his comments about Google’s Taylorist goals during the company’s 2006 press day . The Harvard Business Review article on Google, “Reverse Engineering Google’s Innovation Machine,” appeared in the April 2008 issue. Google describes its “mission” here and here . A much lengthier recital of Sergey Brin’s and Larry Page’s comments on Google’s search engine as a form of artificial intelligence, along with sources, can be found at the start of the “iGod” chapter in The Big Switch . Schmidt made his comment about “using technology to solve problems that have never been solved before” at the company’s 2006 analyst day .

I used Neil Postman’s translation of the excerpt from Plato’s Phaedrus, which can be found at the start of Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology . Walter J. Ong quotes Hieronimo Squarciafico in Orality and Literacy . Clay Shirky’s observation about the printing press was made here .

Richard Foreman’s “pancake people” essay was originally distributed to members of the audience for Foreman’s play The Gods Are Pounding My Head . It was reprinted in Edge. I first noted the essay in my 2005 blog post Beyond Google and Evil .

Promulgate:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

10 thoughts on “ “Is Google Making Us Stupid?”: sources and notes ”

I mention your article and link this very useful blog posting in my latest Berkshire Artsblog entry, where I briefly mention a couple of counter-examples from personal experience. If you make an effort to control the effect of online reading, you can still read books, I think.

The Atlantic article was great – thanks. Have you noticed the connection with an earlier edition of the Atlantic?

Oliver Wendell Holmes Snr. famously observed in an early edition of the Atlantic Monthly magazine in 1858, “Every now and then a man’s mind is stretched by a new idea or sensation, and never shrinks back to its former dimensions.” This was published almost exactly 150 years ago, as part of a series of monographs subsequently compiled into a book titled ‘The Autocrat of the Breakfast Table’.

In 1858 philosophers enthused at the way a new idea could expand one’s intellectual horizons. By 2008 there are so many new ideas, so easily found, that our minds are overstretched and overwhelmed by them!

I like your comments about shallow/pancake brains. It causes one to ponder how Holmes would regard the manner in which our minds are stretched by the internet? Deeply or shallowly? One is reminded of the old jest about the difference between people from Melbourne and Sydney, the former being shallowly deep and the later deeply shallow. Are we clogging our minds with shallow ephemera and ‘social networking’ while we upload our deep knowledge to the internet … and with it our practical, dirt under the fingernails, wisdom? Can anyone now become an instant expert on any topic in the manner of Trinity downloading the ability to fly a helicopter in the movie The Matrix? University lecturers frequently comment with dismay about the digital generation’s scant disregard for deep learning. Why bother memorizing when you can just Google knowledge when you need it? Are we now happy with shallow, thin, brains knowing that we can go deep on demand by plugging ourselves into the cloud?

Perhaps ‘diving deep’ into the colder waters of offline knowledge, savored on paper and discussed with face-to-face people, is good for the brain in the same way that good food and regular exercise are good for our bodies?

If Trinity’s ability to fly that helicopter is dependent on her connection to The Matrix what happens when she needs to operate in offline mode?

How about Vannevar Bush As We May Think ? Although crude and anachronistic, the thoughts of the guy who actually invented the idea of a search engine are important as well. At least in terms of how the technology could provide an adjunct to human reasoning rather than as a replacement for it. Eric Schmidt’s idea that Google as a form of AI is a “little bit out there” – too much Starbuck’s, EC?

Did you ever consider the potential effects of screens and their light on our behaviour? Maybe the observed psychological effects are due to the fact that we stare more or less directly at a source of light all the time during the reading process from a screen, which may lead to some unphysiological form of arousal. I observe personally that in evenings I can remain awake behind a laptop screen for hours without feeling tired, but when I switch the screen off and start to read from paper, it takes no more than 5 to 10 minutes and I have to fight against sleep. I attribute this much more to effects of the hardware than to any form of the content.

I just read The Big Switch, and really enjoyed it. Besides all else, it was delightfully well written. I note that you discuss the themes of “Is Google making us stupid?” at some length near the end of the book. However, unless I’ve missed something, none of the commenters in this debate have pointed this out. Maybe they didn’t have enough attention span to get to those last pages… ;-)

Perhaps the Internet and Google are also making us international conformists. As more of us read the same ideas and are less exposed to fringe-thinking (that’s after all what Google [and popular/mass Media] does) we will tend to adopt more popular ideas as our own. Individualism is what has led to the great persons of history and their ideas which themselves have had the most impact on human history. Perhaps, on the positive side, it will lead to greater peace – wars are frequently about clashing ideals and purposes after all. I would not ,however, vote for peace if it meant trading humanity’s progress in the bargain.

When the Atlantic runs a full page ad in Business Week (Nov 03 Issue) with only the words ‘Is google making us stupid?”

You can safely say you hit a nerve

Hello Nick,

My name is Jessica, and I am a senior at Milken Community High School. My history class, America 3.0 (a study of the last 40 years of American history and how it will affect the future of our country) recently read your book, The Big Switch, and I particularly found your iGod chapter to be riveting, as well as frightening when discussing the looming future of artificial intelligence integrated into our brains.

When I discussed this topic with my friends, they seemed very aggressive and quick to put down my feelings of ambivalence towards this future technology. One friend in particular strongly supports the utilization of this technology, claiming that it will improve our quality of life ten fold due to the instant gratification that the brain chip will give us. Mass amounts of information readily available at our fingertips will allow for learning to elevate to a new level.

My issue with this technology is the potential it provides for mind infiltration. It is no secret, there are people all around the world that hack computers, and steal extremely important information. Take China for example, with online communities designated to attack the United States government websites through Denial of Service attacks. They’ve stolen terabytes of information on the F-25 joint strike fighter, which America and other NATO supporting companies have supported billions into. We still don’t know what they did with the information, except that they have it and that it can be used against us.

Now, with the issue of hackers getting into computer databases in our government, an institution that is supposed to be the safest in the country, how are we supposed to allow computer chips to be installed into our brains? I truly believe that it doesn’t matter how advanced technology gets, there will always be a way to break it down and I definitely don’t feel comfortable with the idea of someone getting into my mind. When the information being stolen is external, tangible, outside of my body, it is explainable. It can be taken by anyone. But, when something is in the safety of my mind, and is open to be absconded with, that is where the true fear begins to erupt.

This type of hacking opens to door to all different kinds of mind based warfare, and Orwellian opportunities. Who is to say that America won’t enter the age of 1984, and use computer databases in our minds just as the Thought Police did? We are entering uneasy times in our country, and already you can slowly see civil liberties being taken away. Say the word ‘bomb’ in an airport, and you will see what our country has come to. No longer will you have to say the word ‘bomb’, all you will have to do is think it. People will be wrongly attacked and questioned for harmless thoughts, and involuntary daydreams that were not floating through the id with violent intentions.

You speak about the technology, “…offer[ing] the ‘potential for outside control of human behavior through digital media.’ We will become programmable, too” (pg 217). The age in which humans will no longer be able to be differentiated on the basis of intelligence, where we will be able to technologically advance our brains without the labor of learning, will be a very dark age. No longer will education be respected, or necessary for that matter. Why even live if every single documented human experience will be readily available in our minds? There will no longer be surprise…accomplishment…competition…we will turn into a conformist country, ruled by robots.

We recently read your article “Is Google Making Us Stupid” in my College English class. I am a mom of two and the artical actually really made me think about why my girls don’t like to sit down and read a book. The article made me realize that their brains were never trained to be that quiet and that still. We are now working with them to train their brains to slow down so they can sit and read for long periods of time. I no longer get severely frustrated with them because I understand them a little better. Thank you.

Thanks for this list of sources. Even if you read a book on a kindle it’s not the same as reading a real book – it’s ontologically different!

See Ong’s lectures:

http://libraries.slu.edu/special/digital/ong/audio.php

and Michael Heim’s argument:

http://www.mheim.com/files/21c-heim.pdf

Comments are closed.

Home — Essay Samples — Information Science and Technology — Impact of Technology — Review of Nicholas Carr’s ‘Is Google Making Us Stupid’

Review of Nicholas Carr's 'Is Google Making Us Stupid'

- Categories: Impact of Technology Negative Impact of Technology

About this sample

Words: 1487 |

Published: Apr 8, 2022

Words: 1487 | Pages: 3 | 8 min read

Works Cited

- Carr, N. (2008, July). Is Google Making Us Stupid? The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2008/07/is-google-making-us-stupid/306868/

- Goel, V., & Grafman, J. (2000). Are we less intelligent than we were 100 years ago? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4(5), 176-181.

- Greenfield, S. (2009). The mind and brain of short-term memory. Scientific American, 301(5), 50-55.

- Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide. NYU Press.

- Johnson, S. (2010). The medium is the metaphor. In Everything Bad is Good for You: How Today's Popular Culture is Actually Making Us Smarter (pp. 77-103). Penguin Books.

- Liu, Z. (2005). Reading behavior in the digital environment: Changes in reading behavior over the past ten years. Journal of Documentation, 61(6), 700-712.

- Manovich, L. (2001). The language of new media. MIT Press.

- McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding media: The extensions of man. Routledge.

- Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: What the internet is hiding from you. Penguin.

- Wolf, M. (2007). Proust and the squid: The story and science of the reading brain. Harper Perennial.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr Jacklynne

Verified writer

- Expert in: Information Science and Technology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 459 words

4 pages / 2022 words

1 pages / 448 words

4 pages / 1798 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Impact of Technology

Technology has transformed the way we live, work and communicate. The advancements in technology have brought about numerous benefits, but they have also raised concerns regarding the effects on different aspects of our lives. [...]

The trajectory of technological advancement has been nothing short of remarkable, and the pace at which innovation is occurring is accelerating exponentially. As we look ahead, it becomes evident that technology will continue to [...]

Technology has revolutionized the way we live, work and communicate. In the 21st century, it seems that we cannot function without our smartphones, tablets, laptops, and most importantly, the internet. While technology has [...]

The impact of technology on daily life is multifaceted, touching upon communication, work, education, entertainment, health, and more. As we navigate the digital landscape, it is imperative to recognize the opportunities and [...]

There has been lot of improvements in the field of technology and communication. Texting is one of them. This is something that you don’t need verbal speaking and is very short. Basically, young generations are more influenced [...]

Five years after the end of World War II, the 1950s brought an era of economic prosperity, changed some cultural norms, and provided people with fast and easy access to news, entertainment, and other things. However, the [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Is Google Making Us Ungodly?

You Are What You Scroll

In August 2008, writer and researcher Nicholas Carr published an essay in The Atlantic entitled, “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” At the start of the essay, Carr offers a lament for his mind. It remains one of the most important paragraphs I’ve ever read:

Over the past few years I’ve had an uncomfortable sense that someone, or something, has been tinkering with my brain, remapping the neural circuitry, reprogramming the memory. My mind isn’t going—so far as I can tell—but it’s changing. I’m not thinking the way I used to think. I can feel it most strongly when I’m reading. Immersing myself in a book or a lengthy article used to be easy. My mind would get caught up in the narrative or the turns of the argument, and I’d spend hours strolling through long stretches of prose. That’s rarely the case anymore. Now my concentration often starts to drift after two or three pages. I get fidgety, lose the thread, begin looking for something else to do. I feel as if I’m always dragging my wayward brain back to the text. The deep reading that used to come naturally has become a struggle. 1

Carr’s search to discover the cause for his mental distress led him to a revolutionary conclusion. The internet, which had become for Carr (like millions of others) the most normal, most immersive, most consuming medium of communication and learning, was changing his brain. Referring to the net as a “universal medium,” Carr described it not simply as an extreme expansion of traditional written word tools but as something different entirely, something that, particularly through repeated immersion, shaped the human brain to be more net-like.

Digital Liturgies

Samuel D. James

People search for heaven in all the wrong places, and the internet is no exception. Digital Liturgies warns readers of technology’s damaging effects and offers a fulfilling alternative through Scripture and rest in God’s perfect design.

Two years after his essay appeared in The Atlantic , Carr expanded his argument into a book. The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains makes a clear, persuasive, and important argument that the form of the web is a neurologically powerful tool for rewiring how human beings learn, feel, and process information. If Carr is correct, then it’s not just the messages that we find on the web that influence us; it’s the web itself, the process through which the web puts us as we engage its powers. As Marshall McLuhan put it, “The medium is the message.” 2 And in the case of the web, it is one of the most powerful messages in the world.

Carr begins by unpacking cognitive research that demonstrates the human brain’s “plasticity.” This refers to the ability of our brain to make significant changes to itself: new neural patterns and different kinds of synapses that retrain our brain how to interpret input. “Every time we perform a task or experience a sensation, whether physical or mental,” Carr writes, “a set of neurons in our brains is activated.”

If they’re in proximity, these neurons join together. . . . As the same experience is repeated, the synaptic links between the neurons grow stronger and more plentiful through both physiological changes, such as the release of higher concentrations of neurotransmitters, and anatomical ones, such as the generation of new neurons or the growth of new synaptic terminals. . . . What we learn as we live is embedded in the ever-changing cellular connections inside our heads. 3

That’s an intimidating-sounding paragraph to most of us. But the point is simple enough: the human brain possesses within itself the capacity to change. The neural phenomena that are associated with one set of attitudes or behaviors can change into a different kind in response to repeated practices or consumption. In other words, our choices matter in shaping us into a certain kind of person. Carr concludes, “Our ways of thinking, perceiving, and acting, we now know, are not entirely determined by our genes. Nor are they entirely determined by our childhood experiences. We change them through the way we live —and . . . through the tools we use .” 4

The plasticity of the brain helps to explain the phenomenon of how major technologies can create different kinds of societies that end up shaped around the technologies. Part of the reason this is true at a cultural level is that it is true at an individual level. New technologies do more than give us new ideas or methods; they can create new neural pathways in our brains that transform how we conceive and respond to reality. Carr cites political scientist Langdon Winner as saying, “If the experience of modern society shows us anything, it is that technologies are not merely aids to human activity, but also powerful forces acting to reshape that activity and its meaning.” 5 In particular, Carr specifies that “intellectual technologies”—technologies that directly influence human language and thinking—communicate by their design and function certain ideas about “how the human mind works or should work.” 6 In other words, our intellectual technologies are constantly preaching to us, and over time, their sermons transform how we think and act.

Carr’s category of intellectual technologies is helpful for making distinctions between certain kinds of technology. A wheel, a rifle, and a jet airplane certainly reshape cultures through the possibilities they unlock and the vision of life we embrace as we use them. But this effect is significantly different from the effect that language-based tools have. Devices and practices that alter our habits of speaking and reading consequently alter our habits of learning and thinking. It is these technologies that tend to have the most power over us.

Talking about any technology this way may sound strange to you. Over the last few months, I’ve been asked many times what my book is about. When I tell someone that it’s about the spiritually formative power of the web, I can almost always see a mixture of understanding and confusion in their faces. The confusion may owe to the fact that many evangelicals do not intuitively attribute spiritual significance to things . Objects, places, and other material realities don’t seem morally or spiritually important. We tend to emphasize the limits of material things, what they are not . The church is not a building. God’s word is not a leather-bound book (but the canonical words within that book). Our attention is fixed on the immaterial often to the exclusion of the material.

Yet a strict material/immaterial dualism is not what Christianity teaches. Neuroplasticity and the formative power of technology are profoundly theologically relevant because human beings, created in the image of God and belonging to God “body and soul,” 7 are irrevocably physical. While our bodies and souls are not equally central to our spiritual lives, our souls depend on our bodies, 8 which means that our spiritual lives—our pursuit of sanctification, of wisdom, and of virtue—are bodily lives too. What’s more, habits and practices, while carried out externally by physical means, are spiritually significant because they shape us into particular kinds of people.

In Psalm 1, the blessed man is described as one who delights in the law of the Lord and meditates on it day and night (Ps. 1:2).

He is like a tree planted by streams of water that yields its fruit in its season, and its leaf does not wither. In all that he does, he prospers. (Ps. 1:3)

Here, spiritual blessedness is connected to the physical (neurological) practice of meditating on the law of the Lord with delight. To drive home the point, the psalmist compares the blessed, law-meditating man to a tree whose roots drink deeply of a rich stream. While the blessed man’s relationship to God’s word is certainly more than a physical matter of hearing and meditating on it, it is not less .

Carr’s insights into the power of material things to change us resonate deeply with a Christian view of spirituality. In his book You Are What You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habit , James K. A. Smith makes the case that our conformity to the image of Christ is a process expressed through the formative effect of repeated actions and rituals:

In our culture that prizes “authenticity” and places a premium on novelty and uniqueness, imitation has received a bad rap, as if being an imitator is synonymous with being a fake (think “imitation leather”). But the New Testament holds imitation in a very different light. Indeed, we are exhorted to be imitators. “Follow my example,” Paul says, “as I follow the example of Christ” (1 Cor. 11:1). Similarly, Paul commends imitation to the Christians at Philippi: “join together in following my example, brothers and sisters, and just as you have us as a model, keep your eyes on those who live as we do” (Phil. 3:17). Like a young boy who learns to shave by mimicking what he sees his father doing, so we learn to “put on” the virtues by imitating those who model the Christlike life. This is part of the formative power of our teachers who model the Christian life for us. It’s also why the Christian tradition has held up as exemplars of Christlikeness the saints, whose images were often the stained glass “wallpaper” of Christian worship. . . . Such moral, kingdom-reflecting dispositions are inscribed in your character through rhythms and routines and rituals, enacted over and over again, that implant in you a disposition to an end ( telos ) that becomes a character trait—a sort of learned, second-nature default orientation that you trend toward “without thinking about it.” 9