Religious beliefs give strength to the anti-abortion movement – but not all religions agree

Professor of Law, Director of the Center for Religion, Law & Democracy, Willamette University

Disclosure statement

Steven K. Green does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

View all partners

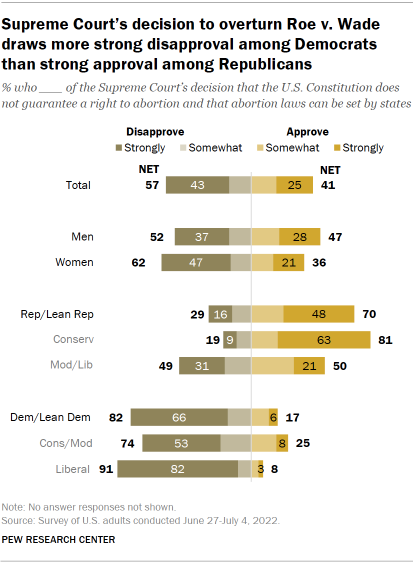

The leaked draft of Justice Samuel Alito’s opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization , which has sent shock waves across the United States, indicates that a majority of Supreme Court justices will likely overturn the constitutional right to an abortion granted in Roe v. Wade . Employing unusually harsh language, Alito declared that “Roe and Planned Parenthood v.Casey must be overruled” because of the decisions’ “abuse of judicial authority.”

“Roe was egregiously wrong from the start,” Alito wrote, and its “reasoning was exceptionally weak.”

He also asserted that neither abortion nor privacy is mentioned in the text of the Constitution, nor should they be considered to be “deeply rooted in the Nation’s history or traditions” so as to be worthy of protection.

As a professor of constitutional law who has taught about reproductive rights for more than 20 years, I argue that Alito’s legal reasoning leaves out several established constitutional principles also not mentioned in the text – such as separation of powers and executive privilege – as well as rights that conservatives hold near and dear like the right to marry and parental rights.

Alito’s claim that a right to an abortion “was entirely unknown in American law” until Roe is unfounded. Historically, abortion was not completely illegal , even in Puritan New England. The first abortion restrictions were enacted in the U.S. in the 1820s .

Even then, they generally outlawed abortions only after “quickening,” the early equivalence of fetal viability – the ability to survive outside the mother’s womb. Alito’s legal rationales aside, the legal debate over abortion is as much a religious dispute as it is a constitutional one.

Religious opposition

Most anti-abortion rallies have signs and banners with religious admonitions such as “ pray for life ” and “ pray to end abortion .”

Today, the Catholic Church’s strong opposition to abortion and contraception is well known. However, in an interesting recent book, “ Abortion in Early Modern Italy ,” historian John Christopoulos argues that prior to 1588, the Catholic Church’s position on abortion was more ambiguous. Before then, the church did not necessarily oppose abortion before quickening, but in that year shifted its position through a papal declaration that pronounced that the human soul is created at the moment of conception, known as “ ensoulment ,” and that all abortions were murder.

In 1968, the National Conference of Catholic Bishops founded the National Right to Life organization to coordinate activities of state groups that opposed abortion. In 1973, following Roe, the organization incorporated as the National Right to Life Committee, severing formal ties with the Catholic Church in order to attract conservative Protestants.

In addition to Catholic groups such as Priests for Life , opposition to abortion is driven by other conservative groups with Protestant members, including the Faith and Freedom Coalition and the Family Research Council .

More militant anti-abortion groups such as Operation Rescue and Operation Save America also state their opposition on religious grounds. According to one OSA official , “Satan wants to kill innocent babies, demean marriage and distort the image of God.”

Religious division

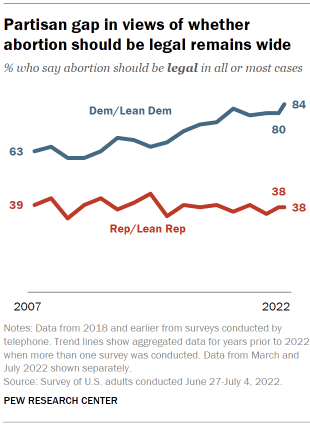

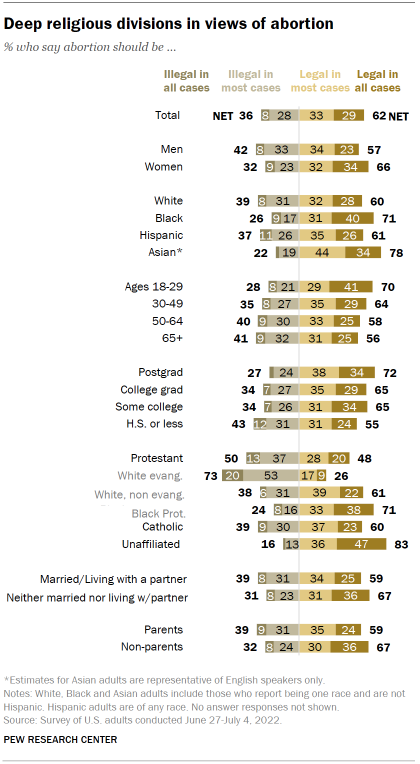

In actuality, America’s religious community is divided over the issue of abortion. According to the Pew Research Center , approximately three-quarters of white evangelical Protestants – 77% – say abortion should be illegal in all or most cases, while 63% of white Protestants who are not evangelical say abortion should be legal in all or most cases. Interestingly, attitudes of Catholic laity are more narrowly split – 55% favor legal abortion in all or most cases, while 43% say it should be illegal in all or most cases.

As philosopher Peter Wenz argued in his book “ Abortion Rights as Religious Freedom ,” one’s opinion about whether a pre-viable fetus is a person is a religious decision. Abortion restrictions interfere with this right to religious freedom.

Several liberal denominations agree. A 1981 resolution of the United Church of Christ declares that “every woman must have the freedom of choice to follow her personal and religious convictions concerning the completion or termination of a pregnancy.” And according to the National Council of Jewish Women, Jewish law does not recognize a fetus to be a person but instead teaches that abortion is permitted and even required when a woman’s health is endangered.

Yet for conservative Christians who believe that life or ensoulment begins at conception, there can be no compromise on the issue of abortion. And the issue of abortion has long been a priority among conservatives in a way not shared by liberals. This helps explain much of the staying power in the anti-abortion movement. Fifty years of legal precedent support the right to abortion. But anti-abortion activists’ moral certainty about the issue is so strong that, in their eyes, even this half-century of precedent seems destined to crumble.

After all, they reason, legal rules and principles are rarely absolute. For them, the religious certainty about the wrongness of abortion provides an answer that the law lacks.

- Catholic church

- Conservatives

- Religion and society

- Anti-abortion

- Religion and law

- Dobbs v. Jackson

Events and Communications Coordinator

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Skip to Content

There is no one ‘religious view’ on abortion: A scholar of religion, gender and sexuality explains

- Share via Twitter

- Share via Facebook

- Share via LinkedIn

- Share via E-mail

Views on abortion differ not only among major religious traditions, but within each one

The Catholic Church’s official line on abortion , and even on any artificial birth control , is well known: Don’t do it.

Surveys of how American Catholics live their lives, though, tell a different story.

The vast majority of Catholic women have used contraceptives, despite the church’s ban. Fifty-six percent of U.S. Catholics believe abortion should be legal in all or most circumstances, whether or not they believe they would ever seek one. One in four Americans who have had abortions are Catholic, according to the Guttmacher Institute, which advocates for reproductive health.

It’s a clear reminder of the complex relationship between any religious tradition’s teachings and how people actually live out their beliefs. With the U.S. Supreme Court poised to overturn Roe v. Wade , the 1973 ruling that protects abortion rights nationwide, religious attitudes toward a woman’s right to end a pregnancy are in the spotlight. But even within one faith, there is no one religious position toward reproductive rights – let alone among different faiths.

People opposed to abortion gather at the Washington Monument during the 2017 March for Life rally in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Tasos Katopodis/AFP via Getty Images ).

Christianity and conscience

As a scholar of gender and religion , I research how religious traditions shape people’s understandings of contraception and abortion.

When it comes to official stances on abortion, religions’ positions are tied to different approaches to some key theological concepts. For instance, for several religions, a key issue in abortion rights is “ensoulment,” the moment at which the soul is believed to enter the body – that is, when a fetus becomes human.

The catch is that traditions place ensoulment at different moments and give it various degrees of importance. Catholic theologians place ensoulment at the moment of conception , which is why the official position of the Catholic Church is that abortion is never permitted. From the moment the sperm meets the egg, in Catholic theology, a human exists, and you cannot kill a human, regardless of how it came to exist. Nor can you choose between two human lives, which is why the church opposes aborting a fetus to save the life of the pregnant person .

As in any faith, not all Catholics feel compelled to follow the church teachings in all cases. And regardless of whether someone thinks they would ever seek an abortion, they may believe it should be a legal right. Fifty-seven percent of U.S. Catholics say abortion is morally wrong, but 68% still support Roe v. Wade , while only 14% believe that abortion should never be legal.

Some Catholics advocate for abortion access not despite but because of their dedication to Catholic teachings. The organization Catholics for Choice describes its work as rooted in Catholicism’s emphasis on “social justice, human dignity, and the primacy of conscience ” – people making their own decisions out of deep moral conviction.

Other Christians also say faith shapes their support for reproductive rights. Protestant clergy, along with their Jewish colleagues, were instrumental in helping women to secure abortions before Roe, through a network called the Clergy Consultation Service. These pro-choice clergy were motivated by a range of concerns, including desperation that they saw among women in their congregations, and theological commitments to social justice . Today, the organization still exists as the Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice .

There are myriad Protestant opinions on abortion . The most conservative equate it with murder, and therefore oppose any exemptions. The most liberal Protestant voices advocate for a broad platform of reproductive justice, calling on believers to “ Trust Women .”

Who is a ‘person’?

Protesters listen during the 2022 Jewish Rally for Abortion Justice in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images ).

Muslims scholars and clerics, too, have a range of positions on abortion. Some believe abortion is never permitted, and many allow it until ensoulment, which is often placed at 120 days’ gestation, just shy of 18 weeks. In general, many Muslim leaders permit abortion to save the life of the mother , since classical Islamic law sees legal personhood as beginning at birth – though while many Muslims may seek out their religious leaders for guidance about or assistance with abortion, many do not.

Jewish tradition has a great deal of debate about when ensoulment occurs : Various rabbinic texts place it at or even before conception, and many place it at birth, but ensoulment is not as key as the legal status of the fetus under Jewish law. Generally, it is not considered to be a person. For instance, the Talmud – the main source of Jewish law – refers to the fetus as part of the mother’s body. The biblical Book of Exodus notes that if a pregnant woman is attacked and then miscarries, the attacker owes a fine but is not guilty of murder.

In other words, Jewish law protects a fetus as a “potential person,” but does not view it as holding the same full personhood as its mother. Jewish clergy generally agree that abortion is not only permitted, but mandated, to save the life of the mother , because potential life must be sacrificed to save existing life – even during labor, as long as the head has not emerged from the birth canal.

Where Jewish law on abortion gets complicated is when the mother’s life is not at risk. For example, contemporary Jewish leaders debate whether abortion is permitted if the mother’s mental health will be damaged, if genetic testing shows evidence of a nonfatal disability or if there are other compelling concerns, such as that the family’s resources would be strained too much to care for their existing children.

American Jews have generally supported legal abortion with very few restrictions, seeing it as a religious freedom issue – and a question of life versus potential life. Eighty-three percent support a woman’s right to an abortion, and while many might turn to their clergy for support in seeking an abortion, many would not see a need to.

A different view of life

As much diversity as exists in Christianity, Islam, and Judaism, there is likely even more in Hinduism, which has a range of texts, deities and worldviews. Many scholars argue that the fact so many different traditions are all lumped together under the umbrella term “Hindusim” has more to do with British colonialism than anything else.

Most Hindus believe in reincarnation , which means that while one may enter bodies with birth and leave with death, life itself does not, precisely, begin or end. Rather, any given moment in a human body is seen as part of an unending cycle of life – making the question of when life begins quite different than in Abrahamic religions.

Jizo statues sit along the Daiya River and Jiunji Temple in Nikko, Japan. (Photo by John S Lander/LightRocket via Getty Images ).

Some bioethicists see Hinduism as essentially pro-life , permitting abortion only to save the life of the mother. Looking at what people do, though, rather than what a tradition’s sacred texts say, abortion is common in Hindu-majority India, especially of female fetuses .

In the United States, there are immigrant Hindu communities, Asian American Hindu communities, and people who have converted to Hinduism who bring this diversity to their approaches to abortion. Overall, however 68% say abortion should be legal in all or most cases.

Compassionate choices

Buddhists also have varied views on abortion. The Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice notes: “Buddhism, like the other religions of the world, faces the fact that abortion may sometimes be the best decision and a truly moral choice. That does not mean there is nothing troubling about abortion, but it means that Buddhists may understand that reproductive decisions are part of the moral complexity of life.”

Japanese Buddhism in particular can be seen as offering a “middle way” between pro-choice and pro-life positions. While many Buddhists see life as beginning at conception, abortion is common and addressed through rituals involving Jizo , one of the enlightened figures Buddhists call bodhisattvas, who is believed to take care of aborted and miscarried fetuses.

In the end, the Buddhist approach to abortion emphasizes that abortion is a complex moral decision that should be made with an eye toward compassion .

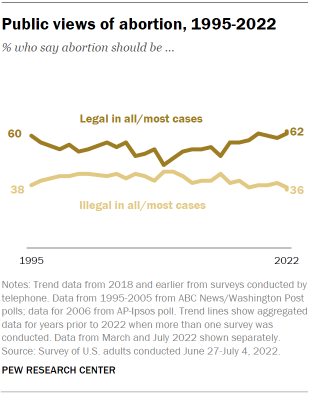

We tend to think of the religious response to abortion as one of opposition, but the reality is much more complicated. Formal religious teachings on abortion are complex and divided – and official positions aside, data shows that over and over , the majority of Americans, religious or not, support abortion.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article .

Related Articles

A justification for unrest? Look no further than the Bible and the Founding Fathers

‘Untraditional’ Hanukkah celebrations are often full of traditions for Jews of color

To tree, or not to tree? How Jewish-Christian families navigate the ‘December Dilemma’

- Jewish Studies

- Religious Studies

- The Conversation

- Women and Gender Studies

Find anything you save across the site in your account

All products are independently selected by our editors. If you buy something, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Is Abortion Sacred?

By Jia Tolentino

Twenty years ago, when I was thirteen, I wrote an entry in my journal about abortion, which began, “I have this huge thing weighing on me.” That morning, in Bible class, which I’d attended every day since the first grade at an evangelical school, in Houston, my teacher had led us in an exercise called Agree/Disagree. He presented us with moral propositions, and we stood up and physically chose sides. “Abortion is always wrong,” he offered, and there was no disagreement. We all walked to the wall that meant “agree.”

Then I raised my hand and, according to my journal, said, “I think it is always morally wrong and absolutely murder, but if a woman is raped, I respect her right to get an abortion.” Also, I said, if a woman knew the child would face a terrible life, the child might be better off. “Dead?” the teacher asked. My classmates said I needed to go to the other side, and I did. “I felt guilty and guilty and guilty,” I wrote in my journal. “I didn’t feel like a Christian when I was on that side of the room. I felt terrible, actually. . . . But I still have that thought that if a woman was raped, she has her right. But that’s so strange—she has a right to kill what would one day be her child? That issue is irresolved in my mind and it will eat at me until I sort it out.”

I had always thought of abortion as it had been taught to me in school: it was a sin that irresponsible women committed to cover up another sin, having sex in a non-Christian manner. The moral universe was a stark battle of virtue and depravity, in which the only meaningful question about any possible action was whether or not it would be sanctioned in the eyes of God. Men were sinful, and the goodness of women was the essential bulwark against the corruption of the world. There was suffering built into this framework, but suffering was noble; justice would prevail, in the end, because God always provided for the faithful. It was these last tenets, prosperity-gospel principles that neatly erase the material causes of suffering in our history and our social policies—not only regarding abortion but so much else—which toppled for me first. By the time I went to college, I understood that I was pro-choice.

America is, in many ways, a deeply religious country—the only wealthy Western democracy in which more than half of the population claims to pray every day. (In Europe, the figure is twenty-two per cent.) Although seven out of ten American women who get abortions identify as Christian, the fight to make the procedure illegal is an almost entirely Christian phenomenon. Two-thirds of the national population and nearly ninety per cent of Congress affirm a tradition in which a teen-age girl continuing an unplanned pregnancy allowed for the salvation of the world, in which a corrupt government leader who demanded a Massacre of the Innocents almost killed the baby Jesus and damned us all in the process, and in which the Son of God entered the world as what the godless dare to call a “clump of cells.”

For centuries, most Christians believed that human personhood began months into the long course of pregnancy. It was only in the twentieth century that a dogmatic narrative, in which every pregnancy is an iteration of the same static story of creation, began both to shape American public policy and to occlude the reality of pregnancy as volatile and ambiguous—as a process in which creation and destruction run in tandem. This newer narrative helped to erase an instinctive, long-held understanding that pregnancy does not begin with the presence of a child, and only sometimes ends with one. Even within the course of the same pregnancy, a person and the fetus she carries can shift between the roles of lover and beloved, host and parasite, vessel and divinity, victim and murderer; each body is capable of extinguishing the other, although one cannot survive alone. There is no human relationship more complex, more morally unstable than this.

The idea that a fetus is not just a full human but a superior and kinglike one—a being whose survival is so paramount that another person can be legally compelled to accept harm, ruin, or death to insure it—is a recent invention. For most of history, women ended unwanted pregnancies as they needed to, taking herbal or plant-derived preparations on their own or with the help of female healers and midwives, who presided over all forms of treatment and care connected with pregnancy. They were likely enough to think that they were simply restoring their menstruation, treating a blockage of blood. Pregnancy was not confirmed until “quickening,” the point at which the pregnant person could feel fetal movement, a measurement that relied on her testimony. Then as now, there was often nothing that distinguished the result of an abortion—the body expelling fetal tissue—from a miscarriage.

Ancient records of abortifacient medicine are plentiful; ancient attempts to regulate abortion are rare. What regulations existed reflect concern with women’s behavior and marital propriety, not with fetal life. The Code of the Assura, from the eleventh century B.C.E., mandated death for married women who got abortions without consulting their husbands; when husbands beat their wives hard enough to make them miscarry, the punishment was a fine. The first known Roman prohibition on abortion dates to the second century and prescribes exile for a woman who ends her pregnancy, because “it might appear scandalous that she should be able to deny her husband of children without being punished.” Likewise, the early Christian Church opposed abortion not as an act of murder but because of its association with sexual sin. (The Bible offers ambiguous guidance on the question of when life begins: Genesis 2:7 arguably implies that it begins at first breath; Exodus 21:22-24 suggests that, in Old Testament law, a fetus was not considered a person; Jeremiah 1:5 describes God’s hand in creation even “before I formed you in the womb.” Nowhere does the Bible clearly and directly address abortion.) Augustine, in the fourth century, favored the idea that God endowed a fetus with a soul only after its body was formed—a point that Augustine placed, in line with Aristotelian tradition, somewhere between forty and eighty days into its development. “There cannot yet be a live soul in a body that lacks sensation when it is not formed in flesh, and so not yet endowed with sense,” he wrote. This was more or less the Church’s official position; it was affirmed eight centuries later by Thomas Aquinas.

In the early modern era, European attitudes began to change. The Black Death had dramatically lowered the continent’s population, and dealt a blow to most forms of economic activity; the Reformation had weakened the Church’s position as the essential intermediary between the layman and God. The social scientist Silvia Federici has argued, in her book “ Caliban and the Witch ,” that church and state waged deliberate campaigns to force women to give birth, in service of the emerging capitalist economy. “Starting in the mid-16th century, while Portuguese ships were returning from Africa with their first human cargoes, all the European governments began to impose the severest penalties against contraception, abortion, and infanticide,” Federici notes. Midwives and “wise women” were prosecuted for witchcraft, a catchall crime for deviancy from procreative sex. For the first time, male doctors began to control labor and delivery, and, Federici writes, “in the case of a medical emergency” they “prioritized the life of the fetus over that of the mother.” She goes on: “While in the Middle Ages women had been able to use various forms of contraceptives, and had exercised an undisputed control over the birthing process, from now on their wombs became public territory, controlled by men and the state.”

Martin Luther and John Calvin, the most influential figures of the Reformation, did not address abortion at any length. But Catholic doctrine started to shift, albeit slowly. In 1588, Pope Sixtus V labelled both abortion and contraception as homicide. This pronouncement was reversed three years later, by Pope Gregory XIV, who declared that abortion was only homicide if it took place after ensoulment, which he identified as occurring around twenty-four weeks into a pregnancy. Still, theologians continued to push the idea of embryonic humanity; in 1621, the physician Paolo Zacchia, an adviser to the Vatican, proclaimed that the soul was present from the moment of conception. Still, it was not until 1869 that Pope Pius IX affirmed this doctrine, proclaiming abortion at any point in pregnancy to be a sin punishable by excommunication.

When I found out I was pregnant, at the beginning of 2020, I wondered how the experience would change my understanding of life, of fetal personhood, of the morality of reproduction. It’s been years since I traded the echo chamber of evangelical Texas for the echo chamber of progressive Brooklyn, but I can still sometimes feel the old world view flickering, a photographic negative underneath my vision. I have come to believe that abortion should be universally accessible, regulated only by medical codes and ethics, and not by the criminal-justice system. Still, in passing moments, I can imagine upholding the idea that our sole task when it comes to protecting life is to end the practice of abortion; I can imagine that seeming profoundly moral and unbelievably urgent. I would only need to think of the fetus in total isolation—to imagine that it were not formed and contained by another body, and that body not formed and contained by a family, or a society, or a world.

As happens to many women, though, I became, if possible, more militant about the right to an abortion in the process of pregnancy, childbirth, and caregiving. It wasn’t just the difficult things that had this effect—the paralyzing back spasms, the ragged desperation of sleeplessness, the thundering doom that pervaded every cell in my body when I weaned my child. And it wasn’t just my newly visceral understanding of the anguish embedded in the facts of American family life. (A third of parents in one of the richest countries in the world struggle to afford diapers ; in the first few months of the pandemic , as Jeff Bezos’s net worth rose by forty-eight billion dollars, sixteen per cent of households with children did not have enough to eat.) What multiplied my commitment to abortion were the beautiful things about motherhood: in particular, the way I felt able to love my baby fully and singularly because I had chosen to give my body and life over to her. I had not been forced by law to make another person with my flesh, or to tear that flesh open to bring her into the world; I hadn’t been driven by need to give that new person away to a stranger in the hope that she would never go to bed hungry. I had been able to choose this permanent rearrangement of my existence. That volition felt sacred.

Abortion is often talked about as a grave act that requires justification, but bringing a new life into the world felt, to me, like the decision that more clearly risked being a moral mistake. The debate about abortion in America is “rooted in the largely unacknowledged premise that continuing a pregnancy is a prima facie moral good,” the pro-choice Presbyterian minister Rebecca Todd Peters writes . But childbearing, Peters notes, is a morally weighted act, one that takes place in a world of limited and unequally distributed resources. Many people who get abortions—the majority of whom are poor women who already have children—understand this perfectly well. “We ought to take the decision to continue a pregnancy far more seriously than we do,” Peters writes.

I gave birth in the middle of a pandemic that previewed a future of cross-species viral transmission exacerbated by global warming, and during a summer when ten million acres on the West Coast burned . I knew that my child would not only live in this degrading world but contribute to that degradation. (“Every year, the average American emits enough carbon to melt ten thousand tons of ice in the Antarctic ice sheets,” David Wallace-Wells writes in his book “ The Uninhabitable Earth .”) Just before COVID arrived, the science writer Meehan Crist published an essay in the London Review of Books titled “Is it OK to have a child?” (The title alludes to a question that Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez once asked in a live stream, on Instagram.) Crist details the environmental damage that we are doing, and the costs for the planet and for us and for those who will come after. Then she turns the question on its head. The idea of choosing whether or not to have a child, she writes, is predicated on a fantasy of control that “quickly begins to dissipate when we acknowledge that the conditions for human flourishing are distributed so unevenly, and that, in an age of ecological catastrophe, we face a range of possible futures in which these conditions no longer reliably exist.”

In late 2021, as Omicron brought New York to another COVID peak, a Gen Z boy in a hoodie uploaded a TikTok , captioned “yall better delete them baby names out ya notes its 60 degrees in december.” By then, my baby had become a toddler. Every night, as I set her in the crib, she chirped good night to the elephants, koalas, and tigers on the wall, and I tried not to think about extinction. My decision to have her risked, or guaranteed, additional human suffering; it opened up new chances for joy and meaning. There is unknowability in every reproductive choice.

As the German historian Barbara Duden writes in her book “ Disembodying Women ,” the early Christians believed that both the bodies that created life and the world that sustained it were proof of the “continual creative activity of God.” Women and nature were aligned, in this view, as the material sources of God’s plan. “The word nature is derived from nascitura , which means ‘birthing,’ and nature is imagined and felt to be like a pregnant womb, a matrix, a mother,” Duden writes. But, in recent decades, she notes, the natural world has begun to show its irreparable damage. The fetus has been left as a singular totem of life and divinity, to be protected, no matter the costs, even if everything else might fall.

The scholar Katie Gentile argues that, in times of cultural crisis and upheaval, the fetus functions as a “site of projected and displaced anxieties,” a “fantasy of wholeness in the face of overwhelming anxiety and an inability to have faith in a progressive, better future.” The more degraded actual life becomes on earth, the more fervently conservatives will fight to protect potential life in utero. We are locked into the destruction of the world that birthed all of us; we turn our attention, now, to the worlds—the wombs—we think we can still control.

By the time that the Catholic Church decided that abortion at any point, for any reason, was a sin, scientists had identified the biological mechanism behind human reproduction, in which a fetus develops from an embryo that develops from a zygote, the single-celled organism created by the union of egg and sperm. With this discovery, in the mid-nineteenth century, women lost the most crucial point of authority over the stories of their pregnancies. Other people would be the ones to tell us, from then on, when life began.

At the time, abortion was largely unregulated in the United States, a country founded and largely populated by Protestants. But American physicians, through the then newly formed American Medical Association, mounted a campaign to criminalize it, led by a gynecologist named Horatio Storer, who once described the typical abortion patient as a “wretch whose account with the Almighty is heaviest with guilt.” (Storer was raised Unitarian but later converted to Catholicism.) The scholars Paul Saurette and Kelly Gordon have argued that these doctors, whose profession was not as widely respected as it would later become, used abortion “as a wedge issue,” one that helped them portray their work “as morally and professionally superior to the practice of midwifery.” By 1910, abortion was illegal in every state, with exceptions only to save the life of “the mother.” (The wording of such provisions referred to all pregnant people as mothers, whether or not they had children, thus quietly inserting a presumption of fetal personhood.) A series of acts known as the Comstock laws had rendered contraception, abortifacient medicine, and information about reproductive control widely inaccessible, by criminalizing their distribution via the U.S. Postal Service. People still sought abortions, of course: in the early years of the Great Depression, there were as many as seven hundred thousand abortions annually. These underground procedures were dangerous; several thousand women died from abortions every year.

This is when the contemporary movements for and against the right to abortion took shape. Those who favored legal abortion did not, in these years, emphasize “choice,” Daniel K. Williams notes in his book “ Defenders of the Unborn .” They emphasized protecting the health of women, protecting doctors, and preventing the births of unwanted children. Anti-abortion activists, meanwhile, argued, as their successors do, that they were defending human life and human rights. The horrors of the Second World War gave the movement a lasting analogy: “Logic would lead us from abortion to the gas chamber,” a Catholic clergyman wrote, in October, 1962.

Ultrasound imaging, invented in the nineteen-fifties, completed the transformation of pregnancy into a story that, by default, was narrated to women by other people—doctors, politicians, activists. In 1965, Life magazine published a photo essay by Lennart Nilsson called “ Drama of Life Before Birth ,” and put the image of a fetus at eighteen weeks on its cover. The photos produced an indelible, deceptive image of the fetus as an isolated being—a “spaceman,” as Nilsson wrote, floating in a void, entirely independent from the person whose body creates it. They became totems of the anti-abortion movement; Life had not disclosed that all but one had been taken of aborted fetuses, and that Nilsson had lit and posed their bodies to give the impression that they were alive.

In 1967, Colorado became the first state to allow abortion for reasons other than rape, incest, or medical emergency. A group of Protestant ministers and Jewish rabbis began operating an abortion-referral service led by the pastor of Judson Memorial Church, in Manhattan; the resulting network of pro-choice clerics eventually spanned the country, and referred an estimated four hundred and fifty thousand women to safe abortions. The evangelical magazine Christianity Today held a symposium of prominent theologians, in 1968, which resulted in a striking statement: “Whether or not the performance of an induced abortion is sinful we are not agreed, but about the necessity and permissibility for it under certain circumstances we are in accord.” Meanwhile, the priest James McHugh became the director of the National Right to Life Committee, and equated fetuses to the other vulnerable people whom faithful Christians were commanded to protect: the old, the sick, the poor. As states began to liberalize their abortion laws, the anti-abortion movement attracted followers—many of them antiwar, pro-welfare Catholics—using the language of civil rights, and adopted the label “pro-life.”

W. A. Criswell, a Dallas pastor who served as president of the Southern Baptist Convention from 1968 to 1970, said, shortly after the Supreme Court issued its decision in Roe v. Wade , that “it was only after a child was born and had life separate from his mother that it became an individual person,” and that “it has always, therefore, seemed to me that what is best for the mother and the future should be allowed.” But the Court’s decision accelerated a political and theological transformation that was already under way: by 1979, Criswell, like the S.B.C., had endorsed a hard-line anti-abortion stance. Evangelical leadership, represented by such groups as Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority , joined with Catholics to oppose the secularization of popular culture, becoming firmly conservative—and a powerful force in Republican politics. Bible verses that express the idea of divine creation, such as Psalm 139 (“For you created my innermost being; you knit me together in my mother’s womb,” in the New International Version’s translation), became policy explanations for prohibiting abortion.

In 1984, scientists used ultrasound to detect fetal cardiac activity at around six weeks’ gestation—a discovery that has been termed a “fetal heartbeat” by the anti-abortion movement, though a six-week-old fetus hasn’t yet formed a heart, and the electrical pulses are coming from cell clusters that can be replicated in a petri dish. At six weeks, in fact, medical associations still call the fetus an embryo; as I found out in 2020, you generally can’t even schedule a doctor’s visit to confirm your condition until you’re eight weeks along.

So many things that now shape the cultural experience of pregnancy in America accept and reinforce the terms of the anti-abortion movement, often with the implicit goal of making pregnant women feel special, or encouraging them to buy things. “Your baby,” every app and article whispered to me sweetly, wrongly, many months before I intuited personhood in the being inside me, or felt that the life I was forming had moved out of a liminal realm.

I tried to learn from that liminality. Hope was always predicated on uncertainty; there would be no guarantees of safety in this or any other part of life. Pregnancy did not feel like soft blankets and stuffed bunnies—it felt cosmic and elemental, like volcanic rocks grinding, or a wild plant straining toward the sun. It was violent even as I loved it. “Even with the help of modern medicine, pregnancy still kills about 800 women every day worldwide,” the evolutionary biologist Suzanne Sadedin points out in an essay titled “War in the womb.” Many of the genes that activate during embryonic development also activate when a body has been invaded by cancer, Sadedin notes; in ectopic pregnancies, which are unviable by definition and make up one to two per cent of all pregnancies, embryos become implanted in the fallopian tube rather than the uterus, and “tunnel ferociously toward the richest nutrient source they can find.” The result, Sadedin writes, “is often a bloodbath.”

The Book of Genesis tells us that the pain of childbearing is part of the punishment women have inherited from Eve. The other part is subjugation to men: “Your desire will be for your husband and he will rule over you,” God tells Eve. Tertullian, a second-century theologian, told women, “You are the devil’s gateway: you are the unsealer of the (forbidden) tree: you are the first deserter of the divine law: you are she who persuaded him whom the devil was not valiant enough to attack.” The idea that guilt inheres in female identity persists in anti-abortion logic: anything a woman, or a girl, does with her body can justify the punishment of undesired pregnancy, including simply existing.

If I had become pregnant when I was a thirteen-year-old Texan , I would have believed that abortion was wrong, but I am sure that I would have got an abortion. For one thing, my Christian school did not allow students to be pregnant. I was aware of this, and had, even then, a faint sense that the people around me grasped, in some way, the necessity of abortion—that, even if they believed that abortion meant taking a life, they understood that it could preserve a life, too.

One need not reject the idea that life in the womb exists or that fetal life has meaning in order to favor the right to abortion; one must simply allow that everything, not just abortion, has a moral dimension, and that each pregnancy occurs in such an intricate web of systemic and individual circumstances that only the person who is pregnant could hope to evaluate the situation and make a moral decision among the options at hand. A recent survey found that one-third of Americans believe life begins at conception but also that abortion should be legal. This is the position overwhelmingly held by American Buddhists, whose religious tradition casts abortion as the taking of a human life and regards all forms of life as sacred but also warns adherents against absolutism and urges them to consider the complexity of decreasing suffering, compelling them toward compassion and respect.

There is a Buddhist ritual practiced primarily in Japan, where it is called mizuko kuyo : a ceremony of mourning for miscarriages, stillbirths, and aborted fetuses. The ritual is possibly ersatz; critics say that it fosters and preys upon women’s feelings of guilt. But the scholar William LaFleur argues, in his book “ Liquid Life ,” that it is rooted in a medieval Japanese understanding of the way the unseen world interfaces with the world of humans—in which being born and dying are both “processes rather than fixed points.” An infant was believed to have entered the human world from the realm of the gods, and move clockwise around a wheel as she grew older, eventually passing back into the spirit realm on the other side. But some infants were mizuko , or water babies: floating in fluids, ontologically unstable. These were the babies who were never born. A mizuko , whether miscarried or aborted—and the two words were similar: kaeru , to go back, and kaesu , to cause to go back—slipped back, counterclockwise, across the border to the realm of the gods.

There is a loss, I think, entailed in abortion—as there is in miscarriage, whether it occurs at eight or twelve or twenty-nine weeks. I locate this loss in the irreducible complexity of life itself, in the terrible violence and magnificence of reproduction, in the death that shimmered at the edges of my consciousness in the shattering moment that my daughter was born. This understanding might be rooted in my religious upbringing—I am sure that it is. But I wonder, now, how I would square this: that fetuses were the most precious lives in existence, and that God, in His vision, already chooses to end a quarter of them. The fact that a quarter of women, regardless of their beliefs, also decide to end pregnancies at some point in their lifetimes: are they not acting in accordance with God’s plan for them, too? ♦

More on Abortion and Roe v. Wade

In the post-Roe era, letting pregnant patients get sicker— by design .

The study that debunks most anti-abortion arguments .

Of course the Constitution has nothing to say about abortion .

How the real Jane Roe shaped the abortion wars.

Black feminists defined abortion rights as a matter of equality, not just “choice.”

Recent data suggest that taking abortion pills at home is as safe as going to a clinic.

When abortion is criminalized, women make desperate choices .

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Paul Elie

By Louis Menand

By Maya Jasanoff

Advertisement

Supported by

Religious Freedom Arguments Underpin Wave of Challenges to Abortion Bans

In lawsuits challenging state abortion bans, lawyers for abortion rights plaintiffs are employing religious liberty arguments the Christian right has used for decades.

- Share full article

By Pam Belluck

Pam Belluck has written about reproductive health for over a decade.

For years, conservative Christians have used the principle of religious freedom to prevail in legal battles on issues like contraceptive insurance mandates and pandemic restrictions. Now, abortion rights supporters are employing that argument to challenge one of the right’s most prized accomplishments: state bans on abortion.

In the year since Roe v. Wade was overturned, clergy and members of various religions, including Christian and Jewish denominations, have filed about 15 lawsuits in eight states, saying abortion bans and restrictions infringe on their faiths.

Listen to This Article

Many of those suing say that according to their religious beliefs, abortion should be allowed in at least some circumstances that the bans prohibit, and that the bans violate religious liberty guarantees and the separation of church and state. The suits, some seeking exemptions and others seeking to overturn the bans, often invoke state religious freedom restoration acts enacted and used by conservatives in some battles over social issues.

The lawsuits show “religious liberty doesn’t operate in one direction,” said Elizabeth Sepper, a law professor at University of Texas at Austin.

Aaron Kemper, a lawyer representing three Jewish women who are suing to overturn Kentucky’s abortion ban, said he studied and emulated federal and state religious liberty cases that conservatives won.

“We were like, it works for them, so we thought we should use sections from those cases,” he said.

Though most lawsuits have not yet yielded court rulings, there are signs the arguments may have some legal traction. In Indiana , a judge issued a preliminary injunction blocking the state’s abortion ban, saying it violated the state’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act adopted in 2015 under then-Gov. Mike Pence, an ardent abortion opponent who is now running for president.

Recognizing a potential threat, Oklahoma and West Virginia recently amended their religious freedom restoration acts to explicitly prevent challenges to abortion bans under the acts.

Some belief systems, including the United Church of Christ’s, support women making their own decisions in pregnancy. Some, including the Episcopal Church and many branches of Judaism have traditions that abortion should be supported in certain cases , especially where pregnancies threaten women’s physical or mental health or involve serious fetal abnormalities. Some faiths do not define life as beginning with conception.

The Indiana case was filed by Hoosier Jews for Choice, three Jewish women and a woman with independent spiritual beliefs. Judge Heather Welch of Marion County Superior Court has certified it as a class-action lawsuit on behalf of “all persons in Indiana whose religious beliefs direct them to obtain abortions in situations prohibited by” the ban.

“The court has concluded that the plaintiffs’ religious exercise is being substantially burdened, that they are suffering irreparable harm,” Judge Welch wrote in blocking the ban for plaintiffs with religious objections.

The state has appealed, arguing that “‘abortion access’ is not religious exercise.” Like other states fighting such lawsuits, Indiana said it has a “compelling interest” to prohibit abortions.

“Plaintiffs identify no principle that makes abortion a religious act any more than countless other actions that they believe to affect their well-being,” Indiana’s attorney general wrote, adding, “Other acceptable means for plaintiffs to achieve such ends in the context of childbearing include sexual abstinence, contraceptives, IUDs and natural family planning, just to name a few.”

Indiana’s ban had already been on hold because of a preliminary injunction in a lawsuit citing other objections to the law. On Friday, in a ruling in that lawsuit, an appeals court said the ban could be enforced. But those with religious freedom objections can still seek abortions until an appeals court rules in the religious case, lawyers said.

Decades ago, some anti-abortion groups warned that religious freedom arguments might be used to bolster abortion rights. When Congress considered what became the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act, the National Right to Life Committee and the U.S. Catholic Conference raised that concern.

“The Act, if passed, will be used to seek access to abortions,” the Catholic Conference’s general counsel wrote in 1992 .

In Florida, lawsuits filed by Episcopal, Buddhist, Unitarian Universalist, Jewish and United Church of Christ clergy say abortion restrictions violate “clerical obligations and faith” and impose “severe barriers” on religious belief, speech and conduct.

“We believe God is the source of all life and has caused us to share in the work of creation,” said one plaintiff, the Rev. Dr. Laurie Hafner, senior pastor of Coral Gables Congregational United Church of Christ. “The privileges and responsibilities of being part of co-creating,” she said, mean “women have the ability and wherewithal to make the decision that’s right for them.”

Reverend Hafner said she had counseled parishioners deciding whether to terminate pregnancies, including a 14-year-old girl and a woman whose fetus was nonviable. Florida’s six-week abortion ban is currently on hold, but, she said, “what if it gets to that place where I can no longer sit at the bedside or in the living room or in my office with someone out of fear of what might happen?”

Within any faith, there may be varying opinions on abortion. But many of those suing say abortion bans embed conservative Christian ideology into state law.

One Kentucky plaintiff, Sarah Baron, a 38-year-old mother of two and a board member of a Louisville synagogue, said, “The Torah teaches us that the fetus does not have the same personhood status as the mother until its first breath.”

Ms. Baron, who belongs to Judaism’s conservative denomination, said her age and previous fertility struggles raised risks of pregnancy complications or fetal abnormalities.

Under Kentucky’s ban, she said, “I would be unable to make that extremely difficult decision of whether to continue carrying a fetus if the pregnancy is causing severe physical or psychological harm to me or the fetus is nonviable.”

“It’s not only cruel,” she said, “but it represents a situation where Jewish law may require the pregnancy to be terminated.”

Within Judaism, there are differing views, with some Orthodox Jews supporting only very limited circumstances for abortion. But Mr. Kemper, the Kentucky plaintiffs’ lawyer, said rabbis from every large Kentucky synagogue have supported the lawsuit.

The lawsuits by members of widely known faiths follow a trail blazed by a less conventional religion, the Satanic Temple, which began filing abortion-related lawsuits after the Supreme Court’s 2014 Hobby Lobby decision exempting family-owned corporations from the Affordable Care Act’s mandate that insurance cover contraceptives. The temple, which is recognized by the I.R.S. as a religion and lists 46 American congregations , has lawsuits pending in Idaho, Texas and Indiana, and it recently started the first telemedicine abortion service operated by a religion, with a goal of using it to challenge abortion restrictions.

A nontheistic religion that construes Satan not as a New Testament evildoer but as the English literary character who battles oppression, the Satanic Temple often employs a strategy of flamboyant provocation, said Joseph Laycock, a religion scholar at Texas State University and the author of a book about the temple. Its antics make some abortion rights supporters worry that it will stoke anti-abortion sentiment. But some courts have taken its religious freedom claims on various issues seriously, including in a recent preliminary ruling ordering a school district in Hellertown, Pa., to allow its After School Satan Club to meet.

Marci Hamilton, a religious freedom expert at the University of Pennsylvania who represents clergy in abortion rights lawsuits in Florida, called the temple’s lawsuits “extremely helpful.”

“They are saying, OK, courts, if you’re going to favor the religious right, we’re going to show you a faith whose rights are being violated,” she added.

The temple created an abortion ritual, a recitation of tenets about individual control over one’s body and the importance of making decisions based on science. Its general counsel, Matthew Kezhaya, said the ritual strengthens legal claims by linking “abortion and the religion itself” and establishing a practice “interfered with by these particular laws.”

The temple’s telemedicine service is currently available in New Mexico, where abortion is legal, but it plans to expand to states with bans and religious freedom laws, temple officials said. It has an intentionally inflammatory name, Samuel Alito’s Mom’s Satanic Abortion Clinic (after the Supreme Court justice who wrote the opinion overturning Roe), but it follows standard medical procedures, employs experienced reproductive health nurses and is listed by a national clearinghouse of legitimate medication abortion services .

One patient, Mikayla, 28, who asked to be identified by her first name to protect her privacy, drove from Texas to an Albuquerque airport hotel to use the service , and allowed The New York Times to observe. During video medical consultations, a nurse practitioner and patient care coordinator discussed effects like cramping and bleeding and urged her to call their 24-hour nurse hotline with questions or concerns.

After she received the medication, the process took a different turn. Via Zoom, a minister prompted Mikayla to look in a mirror to reflect on self-empowerment and recite: “One’s body is inviolable, subject to one’s own will alone.” After swallowing the first pill in the two-drug regimen, Mikayla recited a tenet about prioritizing science. The minister advised that after the pregnancy tissue was eventually expelled, Mikayla could recite: “By my body, my blood. By my will, it is done.”

Legal experts said some religious freedom lawsuits seeking abortion rights might succeed, given recent Supreme Court decisions that “supported religious exemptions even in cases where there are really strong health and safety issues,” said Elizabeth Reiner Platt, director of the Law, Rights and Religion Project at Columbia University. Arguments for exemptions might also be persuasive because most abortion bans have some exceptions, like rape, experts said.

“These should be very strong, compelling cases, but I also acknowledge that this is a highly political issue,” Ms. Platt said.

Josh Blackman, a professor at South Texas College of Law Houston who has criticized the lawsuits, questioned the plaintiffs’ legal standing, saying, “A lot of these women are sort of making prospective claims that, One day, I might be pregnant, and one day, I might have this problem and that might require me to have an abortion.”

He said some plaintiffs could have religiously sincere “extenuating individual circumstances,” but that allowing widespread exemptions could undermine the law’s larger purpose.

Whichever way courts rule could be groundbreaking.

“We’re in a completely new landscape,” Ms. Platt said.

Adria Malcolm contributed reporting from Albuquerque.

Audio produced by Kate Winslett .

Pam Belluck is a health and science writer whose honors include sharing a Pulitzer Prize and winning the Victor Cohn Prize for Excellence in Medical Science Reporting. She is the author of “Island Practice,” a book about an unusual doctor. More about Pam Belluck

Princeton Legal Journal

The First Amendment and the Abortion Rights Debate

Sofia Cipriano

Following Dobbs v. Jackson ’s (2022) reversal of Roe v. Wade (1973) — and the subsequent revocation of federal abortion protection — activists and scholars have begun to reconsider how to best ground abortion rights in the Constitution. In the past year, numerous Jewish rights groups have attempted to overturn state abortion bans by arguing that abortion rights are protected by various state constitutions’ free exercise clauses — and, by extension, the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. While reframing the abortion rights debate as a question of religious freedom is undoubtedly strategic, the Free Exercise Clause is not the only place to locate abortion rights: the Establishment Clause also warrants further investigation.

Roe anchored abortion rights in the right to privacy — an unenumerated right with a long history of legal recognition. In various cases spanning the past two centuries, t he Supreme Court located the right to privacy in the First, Fourth, Fifth, Ninth, and Fourteenth Amendments . Roe classified abortion as a fundamental right protected by strict scrutiny, meaning that states could only regulate abortion in the face of a “compelling government interest” and must narrowly tailor legislation to that end. As such, Roe ’s trimester framework prevented states from placing burdens on abortion access in the first few months of pregnancy. After the fetus crosses the viability line — the point at which the fetus can survive outside the womb — states could pass laws regulating abortion, as the Court found that “the potentiality of human life” constitutes a “compelling” interest. Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey (1992) later replaced strict scrutiny with the weaker “undue burden” standard, giving states greater leeway to restrict abortion access. Dobbs v. Jackson overturned both Roe and Casey , leaving abortion regulations up to individual states.

While Roe constituted an essential step forward in terms of abortion rights, weaknesses in its argumentation made it more susceptible to attacks by skeptics of substantive due process. Roe argues that the unenumerated right to abortion is implied by the unenumerated right to privacy — a chain of logic which twice removes abortion rights from the Constitution’s language. Moreover, Roe’s trimester framework was unclear and flawed from the beginning, lacking substantial scientific rationale. As medicine becomes more and more advanced, the arbitrariness of the viability line has grown increasingly apparent.

As abortion rights supporters have looked for alternative constitutional justifications for abortion rights, the First Amendment has become increasingly more visible. Certain religious groups — particularly Jewish groups — have argued that they have a right to abortion care. In Generation to Generation Inc v. Florida , a religious rights group argued that Florida’s abortion ban (HB 5) constituted a violation of the Florida State Constitution: “In Jewish law, abortion is required if necessary to protect the health, mental or physical well-being of the woman, or for many other reasons not permitted under the Act. As such, the Act prohibits Jewish women from practicing their faith free of government intrusion and thus violates their privacy rights and religious freedom.” Similar cases have arisen in Indiana and Texas. Absent constitutional protection of abortion rights, the Christian religious majorities in many states may unjustly impose their moral and ethical code on other groups, implying an unconstitutional religious hierarchy.

Cases like Generation to Generation Inc v. Florida may also trigger heightened scrutiny status in higher courts; The Religious Freedom Restoration Act (1993) places strict scrutiny on cases which “burden any aspect of religious observance or practice.”

But framing the issue as one of Free Exercise does not interact with major objections to abortion rights. Anti-abortion advocates contend that abortion is tantamount to murder. An anti-abortion advocate may argue that just as religious rituals involving human sacrifice are illegal, so abortion ought to be illegal. Anti-abortion advocates may be able to argue that abortion bans hold up against strict scrutiny since “preserving potential life” constitutes a “compelling interest.”

The question of when life begins—which is fundamentally a moral and religious question—is both essential to the abortion debate and often ignored by left-leaning activists. For select Christian advocacy groups (as well as other anti-abortion groups) who believe that life begins at conception, abortion bans are a deeply moral issue. Abortion bans which operate under the logic that abortion is murder essentially legislate a definition of when life begins, which is problematic from a First Amendment perspective; the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment prevents the government from intervening in religious debates. While numerous legal thinkers have associated the abortion debate with the First Amendment, this argument has not been fully litigated. As an amicus brief filed in Dobbs by the Freedom From Religion Foundation, Center for Inquiry, and American Atheists points out, anti-abortion rhetoric is explicitly religious: “There is hardly a secular veil to the religious intent and positions of individuals, churches, and state actors in their attempts to limit access to abortion.” Justice Stevens located a similar issue with anti-abortion rhetoric in his concurring opinion in Webster v. Reproductive Health Services (1989) , stating: “I am persuaded that the absence of any secular purpose for the legislative declarations that life begins at conception and that conception occurs at fertilization makes the relevant portion of the preamble invalid under the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the Federal Constitution.” Judges who justify their judicial decisions on abortion using similar rhetoric blur the line between church and state.

Framing the abortion debate around religious freedom would thus address the two main categories of arguments made by anti-abortion activists: arguments centered around issues with substantive due process and moral objections to abortion.

Conservatives may maintain, however, that legalizing abortion on the federal level is an Establishment Clause violation to begin with, since the government would essentially be imposing a federal position on abortion. Many anti-abortion advocates favor leaving abortion rights up to individual states. However, in the absence of recognized federal, constitutional protection of abortion rights, states will ban abortion. Protecting religious freedom of the individual is of the utmost importance — the United States government must actively intervene in order to uphold the line between church and state. Protecting abortion rights would allow everyone in the United States to act in accordance with their own moral and religious perspectives on abortion.

Reframing the abortion rights debate as a question of religious freedom is the most viable path forward. Anchoring abortion rights in the Establishment Clause would ensure Americans have the right to maintain their own personal and religious beliefs regarding the question of when life begins. In the short term, however, litigants could take advantage of Establishment Clauses in state constitutions. Yet, given the swing of the Court towards expanding religious freedom protections at the time of writing, Free Exercise arguments may prove better at securing citizens a right to an abortion.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Latest Latest

- The West The West

- Sports Sports

- Opinion Opinion

- Magazine Magazine

Religion influences abortion policy. But does it actually shape people’s abortion views?

New research from public religion research institute explores americans’ views on abortion rights.

By Kelsey Dallas

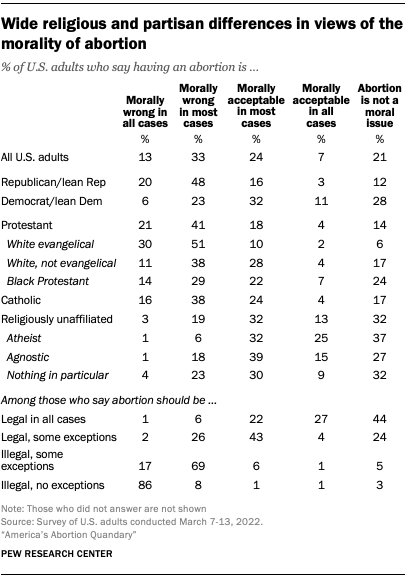

Religion plays a significant role in today’s debates about abortion policy, but few Americans cite faith as the source of their own abortion views, according to a new report from Public Religion Research Institute.

The Institute found that just 31% of U.S. adults agree with the statement, “My religious faith dictates my views on abortion.” Agreement is much more common among those who believe abortion should be illegal (65%) than among those who support abortion rights (14%).

It’s even less common for Americans to look to religious leaders for insights on the issue of abortion, researchers found. Just 16% of U.S. adults told Public Religion Research Institute that they turn to pastors, priests or other faith leaders “for guidance on how to think about abortion.”

White evangelical Protestants were outliers on both of these questions, since relatively large shares of members of this faith group cite faith or faith leaders as a key influence on their abortion views.

For example, nearly 3 in 4 white evangelical Protestants (73%) agreed that faith dictates their views on abortion, compared to 33% of white Catholics and 26% of white mainline Protestants, according to Public Religion Research Institute.

White evangelicals also stand out for their opposition to abortion. Fewer than one-third of members of this faith group (27%) say abortion should be legal in all or most cases. Sixty-four percent of U.S. adults overall hold that view.

“More granularly, 30% (of Americans) say abortion should be legal in all cases, 34% say it should be legal in most cases, 25% say it should be illegal in most cases, and just 9% say it should be illegal in all cases,” researchers wrote in the new survey report.

Along with white evangelicals, Jehovah’s Witnesses (27%), members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (32%) and Hispanic Protestants (44%) are notably less likely than the average American — and members of other faith groups — to believe abortion should be legal.

Public Religion Research Institute’s new report on abortion views is based on online interviews with nearly 23,000 U.S. adults that took place from March to December 2022.

Researchers noted that, for the most part, faith groups’ opinions about abortion remained steady throughout 2022, despite the major state-level policy shifts that came after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in June.

Hispanic Catholics and Black Protestants were the exceptions, the survey report said, since support for abortion rights grew within these groups over the course of the year.

“Among Hispanic Catholics, support for legal abortion in all cases nearly doubled, from 16% in March to 26% in June and 27% in August, reaching a peak of 31% in December,” researchers wrote. “Similarly, support among Black Protestants for abortion being legal in all cases grew from 28% in March and 27% in June to 38% in August and 37% in December.”

Just as members of most faith groups believe abortion should be legal in all or most cases, most people of faith support Roe v. Wade, the landmark 1973 Supreme Court ruling that was overturned.

“With the notable exception of white evangelical Protestants (61%) and Latter-day Saints (52%), less than half of all major religious groups support overturning Roe v. Wade,” Public Religion Research Institute found.

These findings help explain why religious freedom laws are being used to push back against the Supreme Court’s June ruling and new abortion restrictions. People of faith have argued that abortion bans are trampling their ability to live out their faith-based beliefs on abortion, as the Deseret News previously reported.

“There’s both a very rich history and current practice of folks seeing abortion care as a religious and moral calling,” said Elizabeth Reiner Platt, director of the Law, Rights and Religion Project at Columbia Law School, to the Deseret News last year.

But the new report also shows why such arguments can be met with skepticism. As noted above, fewer than one-third of U.S. adults say their faith “dictates” their abortion views, including just 14% of Americans who believe abortion should be legal.

Internet Explorer 11 is not supported

Many people of faith support access to abortion, a new survey from the public religion research institute finds that a significant majority of religious americans think abortion should be legal in most or all cases..

- Abortion has become a highly charged issue since the overturn of Roe v. Wade.

- Efforts to restrict access are increasingly justified by the religious convictions of some public policymakers. A Missouri law, for example, evokes a Supreme Being in its text.

- However, a new survey from the Public Religion Research Institute finds that most people of faith in the U.S. support access to abortion.

Faith and Policy

Personal, not political.

Faith and Democracy

- News & Politics

- The Right Wing

- Election ’20

- Documentaries

- Immigration

- Hot Topics >>

- Corrections

- GET OUR DAILY NEWSLETTER!

- GO AD FREE!

- MAKE A ONE-TIME DONATION

Religious views on abortion more diverse than they may appear in U.S. political debate

Lawmakers who oppose abortion often invoke their faith — many identify as Christian — while debating policy.

The anti-abortion movement’s use of Christianity in arguments might create the impression that broad swaths of religious Americans don’t support abortion rights. But a recent report shows that Americans of various faiths and denominations believe abortion should be legal in all or most cases.

According to a Public Religion Research Institute survey of some 22,000 U.S. adults released last week, 93% of Unitarian Universalists, 81% of Jews, 79% of Buddhists and 60% of Muslims also hold that view.

Researchers also found that most people who adhere to the two major branches of Christianity — Catholicism and Protestantism — also believe abortion should be mostly legal, save for three groups: white evangelical Protestants, Latter-day Saints and Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Historically, the Catholic Church has opposed abortion. But the poll found that 73% of Catholics of color — PRRI defines this group as Black, Asian, Native American and multiracial Americans — support the right to have an abortion, followed by 62% of white Catholics and 57% of Hispanic Catholics.

The findings show that interfaith views on abortion may not be as simple as they appear during political debate, where the voices of white evangelical legislators and advocates can be the loudest.

States Newsroom spoke with Abrahamic religious scholars — specifically, experts in Catholicism, Islam and Judaism — and reproductive rights advocates about varying perspectives on abortion and their history.

Abortion views in America before Roe v. Wade

The Moral Majority — a voting bloc of white, conservative evangelicals who rose to prominence after the U.S. Supreme Court Roe v. Wade ruling in 1973 — is often associated with spearheading legislation to restrict abortion.

Gillian Frank is a historian specializing in religion, gender and sexuality who teaches at the Stevens Institute of Technology in New Jersey. Frank said evangelical views on abortion were actually more ambivalent before the early ’70s Roe decision established the federal right to terminate a pregnancy. (The Supreme Court upended that precedent about two years ago.)

“What we have to understand is that evangelicals, alongside mainline Protestants and Jews of various denominations, supported what was called therapeutic abortion, which is to say abortion for certain exceptional causes,” Frank said, including saving the life or health of the mother, fetal abnormalities, rape, incest and the pregnancy of a minor. Religious bodies like the Southern Baptist Convention and the National Association of Evangelicals said abortion was OK in certain circumstances, he added.

Protestants before Roe did not endorse “elective abortions,” Frank said, or what they called “abortion on demand,” a phrase invoked by abortion-rights opponents today that he said entered the American lexicon around 1962.

The 1973 ruling was seismic and led organizations opposing abortion, such as the National Right to Life Committee — formed by the Conference of Catholic Bishops — to sprout across the country, according to an article published four years later in Southern Exposure . Catholic leaders often lobbied other religious groups — evangelicals, Mormons, orthodox Jews — to join their movement and likened abortion to murder in their newspapers.

After Roe, “abortion is increasingly associated with women’s liberation in popular rhetoric in popular culture, because of the activism of the women’s movement but also because of the ways in which the anti-abortion movement is associating abortion with familial decline,” Frank said. Those sentiments, he said, were spread by conservative figures like Phyllis Schlafly, a Catholic opposed to feminism and abortion, who campaigned against and managed to block the Equal Rights Amendment in the 1970s.

Polls suggest the views of Catholic clergy and laypeople diverge

Catholicism is generally synonymous with opposition to abortion. According to the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops , the church has stood against abortion since the first century. The conference points to Jeremiah 1:5 in the Bible to back up arguments that pregnancy termination is “contrary to the moral law.”

But nearly 6 in 10 American Catholics believe abortion should be mostly legal, according to a Pew Research Center report released last month.

Catholics for Choice spokesperson Ashley Wilson said that there’s a disconnect between the church as an institution and its laity. “We recognize that part of the problem is that the Catholic clergy, and the people who write the official teaching of the church, are all or mostly white male — my boss likes to say ostensibly celibate men — who don’t have wives,” Wilson said. “They don’t have daughters. They have no inroads into the lives of laypeople.”

Her group plans on going to Vatican City in Rome this fall to lift up stories of Catholics who’ve had abortions. The organization is also actively involved in efforts to restore abortion access — 14 states have near-total bans — through direct ballot measures in Colorado , Florida and Missouri this year.

Catholic dioceses and fraternities are often behind counter-efforts to proposed ballot questions. They poured millions into campaigns in Kansas and Kentucky in 2022 to push anti-abortion amendments, and also in Ohio last year to defeat a reproductive rights ballot measure but they failed in each state.

Ensoulment and mercy in Islam

Tenets of Islam — the second largest faith in the world — often make references to how far along a person’s pregnancy is and whether there are complications. University of Colorado Law professor Rabea Benhalim, an expert of Islamic and Judaic law, said there’s a common belief that at 40 days’ gestation, the embryo is akin to a drop of fluid. After 120 days, the fetus gains a soul, she said.

While the Quran doesn’t specifically speak to abortion, Benhalim said Chapter 23: 12-14 is considered a description of a fetus in a womb. The verses are deeply “important in the development of abortion jurisprudence within Islamic law, because there’s an understanding that life is something that is emerging over a period of stages.”

In some restrictive interpretations of Islam, there’s a limit on abortion after 40 days, or seven weeks after implantation, Benhalim said. In other interpretations, because ensoulment doesn’t occur until 120 days of gestation, abortion is generally permitted in some Muslim communities for various reasons, she said. After ensoulment, abortion is allowed if the mother’s life is in danger, according to religious doctrine.

Sahar Pirzada, the director of movement building at HEART, a reproductive justice organization focused on sexual health and education in Muslim American communities, confirmed that some Muslims believe in the 40-day mark, while others adhere to the 120-day mark when weighing abortion.

“How can you make a black-and-white ruling on something that is going to be applied across the board when everyone’s situation is different?” she asked. “There’s a lot of compassion and mercy with how we’re supposed to approach matters of the womb.”

The issue is personal for Pirzada, who had an abortion in 2018 after her fetus received a fatal diagnosis of trisomy 18 when she was 12 weeks pregnant. “I wanted to terminate within the 120-day mark, which gave me a few more weeks,” she said.

She consulted scholars and Islamic teachings before making the decision to end her pregnancy, she said, and mentioned the importance of rahma — mercy — in Islam. “I tried to embody that spirit of compassion for myself,” she said.

Pirzada, who is now a mother of two, had the procedure at exactly 14 weeks on a day six years ago that was both Ash Wednesday and Valentine’s Day. She said she felt loved and surrounded by people of faith at the hospital, where some health care workers had crosses marked in ash on their foreheads. “I felt very appreciative that they were offering me care on a day that was spiritual for them,” she said.

Seeing the stories of people with pregnancy complications in the period since the Supreme Court overturned the federal right to an abortion has left her grief stricken. For instance, Kate Cox, a Texas woman whose fetus had the same diagnosis as Pirzada’s, was denied an abortion by the state Supreme Court in December. Cox had to travel elsewhere for care, Texas Tribune reported.

Benhalim, the University of Colorado expert, said teachings in Islam and Judaism offer solace to followers who are considering abortion, as they can provide guidance during difficult decisions.

No fetal personhood in Judaism

In Jewish texts, the embryo is referred to as water before 40 days of gestation, according to the National Council of Jewish Women . Exodus: 21:22-23 in the Torah mentions a hypothetical situation where two men are fighting and injure a pregnant woman. If she has a miscarriage, the men are only fined. But if she is seriously injured and dies, “the penalty shall be a life for a life.”

This part of the Torah is interpreted to mean that a fetus does not have personhood, and the men didn’t commit murder, according to the council. But this may not be a catchall belief — Benhalim noted that denominations of Judaism have different opinions on abortion.

Today, Jewish Americans have been at the forefront of legal challenges to abortion bans based on religious freedom in Florida , Indiana and Kentucky . Many of the lawsuits have interfaith groups of plaintiffs and argue that restrictions on termination infringe on their religion.

The legal challenge in Indiana has been the most successful. Hoosier Jews for Choice and five anonymous plaintiffs sued members of the state medical licensing board in summer 2022, when Indiana’s near-total abortion ban initially took effect.