- Ideas for Action

- Join the MAHB

- Why Join the MAHB?

- Current Associates

- Current Nodes

- What is the MAHB?

- Who is the MAHB?

- Acknowledgments

How the world is combating the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic

| September 30, 2020 | Leave a Comment

Image by Pete Linforth from Pixabay

Author(s): Gioietta Juo

Since the beginning of 2020 every aspect of our world has changed in an unrecognizable way. Over 200 countries have been affected with the COVID-19 virus. It is in every continent with the exception of the pristine Antarctica. It is now 8 months, what have we achieved? What progress has been made?. It is now time to take stock of the present situation. Are we slowly getting out of the pandemic?? What can we expect the future to look like??

DATA ON CORONAVIRUS WORLDWIDE

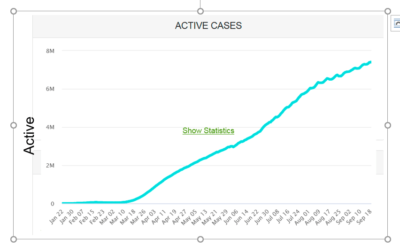

So far, as of September 19, 2020, the. pandemic has caused 30,906,084 cases of coronavirus disease with 959,630 deaths [1].

Figure 1 Active Cases in 2020 in millions

Figure 2 Daily New Cases in 2020 in thousands

It is interesting to note that only 6% of death come from the death of otherwise healthy people. The rest come from those with pre-existing conditions like diabetes, heart and organ weakness and mostly seniors in close contact in places like nursing homes.

Yes, Every aspect of our lives have changed drastically. In order to slow the spread of this highly contagious virus, countries have resorted to a drastic lockdown of ordinary social life as we know it. Schools, shops and many work places have closed. Family is confined to the home. Those who are lucky can work online at home. But others have lost their jobs and depend on government subsistence. But going out means wearing a mask for protection has been mandated.

Even though some countries have slowed down the spread of this virus with social distancing, keeping away from others by more than 6 ft, contact tracing and etc, there are potential down sides. For a start life is lonely not being able to see one’s larger family and friends. Then for those whose marriage is not rock solid, there are emotional risks like child abuse, spouse abuse, drug addictions, alcoholism, and various mental problems even suicides. It has been said that these ills as it happens are worse than the virus itself!! It is imperative that the degree to which these risks have been realized and studied so that health professionals can then develop strategies by which they can be treated. Financial problems can arise, this is where governments have come in to help small businesses and personal problems with stimulus. packages.

There is only a limited time we can lead this dreary life. It is not a permanent solution. Humans are social creatures, we need to go out, meet others, go to schools, have sports, worship in churches and so on……..Most important, schools, the economy cannot be shut down for long.

Now that the season has changed, with the sun beckoning outside, people have the urge to go outside for some fresh air, To the beaches for those living near the coast, to the national parks etc . People cannot be shut indoors forever and it is time to relax the rules.

Most importantly, schools have to open as our children need to go back to their friends and to continue their education. But how?

Social distancing is still necessary. The opening of schools has necessitated a certain closeness in living among the young students, leading to many with low grade fever. In the absence of vaccines what are the solutions? Online teaching is definitely here to stay even though it puts more stress on the families. Then there is nerd immunity [2] where a majority of people who have been exposed and acquired immunity for the virus can impart the immunity to the whole community. That is once a threshold of immune people exist hereby reducing the likelihood of infection for individuals who lack immunity. Immure individuals are unlikely to contribute to disease transmission, They disrupt the chain of infection, which stops or slows the spread of the disease. The greater the proportion of immune individuals in a community, the smaller the probability that that non-immune individuals will come into contact with an immune individual. However, the basic concepts of social distancing, cleanliness of personal hygiene still apply[2].

Definitely, small business – restaurants, hairdressers, stores and workplaces which are the backbone of a country’s economy have to open so long as the basic rules are observed. Innovative ideas such as using the sidewalk for business have sprung up.

PATH TAKEN BY CROATIA TO COMBAT COVID-19

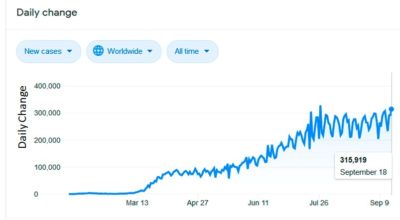

What is happening is Croatia may be an example of what might come [3].

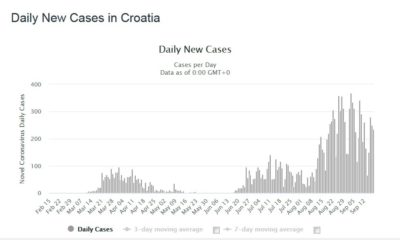

Figure 3 Active Cases in Croatia in 2020

First comes the main peak of active cases. After a mandated social distancing and general lockdown, the number of cases drops drastically. Now is the time to reopen the society and economy? However, after some social mixing, the number of cases rises again. Another lockdown has to happen. Again the number of cases drops. Another attempt of reopening happens followed by an expected rise again of the number of cases. Each time the number of people catching the disease is expected to be lower, Several attempts of reopening will happen until the disease is finally eradicated and society gets back to normal.

Having the confidence that the virus has been licked, the government decided to open up the country completely without restrictions.

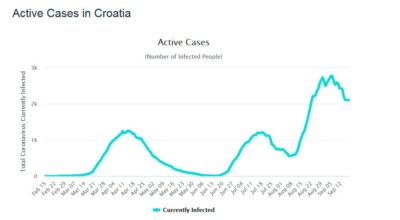

This has led to a disastrous sharp rise in new cases in a third wave. See figures 3 and 4. In fact what we are seeing is the second wave followed by the third wave. Not many countries in the world have seen such pronounced multiple waves. Spain is now seeing the second wave. There are signs that the USA is on its second wave.

Figure 4 Daily New Cases in Croatia

TREATMENTS FOR COVID-19 [4]

Although there is no product approved by the US FDA there are many drugs being tested and used. Remdesivir may be prescribed for emergency use. Otherwise the following are actively being tested:

- Antivirial drugs

In addition to Remdesivir, there are favipiravir and merimepodib.

– Dexamethasone

It is a corticosteroid anti – inflammatory drug studied to treat or prevent organ dysfunction and lung injury from inflammation. With people on ventilators or supplemental oxygen. This can reduce death by 30 %.

- Anti- inflammatory therapy

This is in general useful for more severe cases

- I mmune – based therapy[4]

This is a developing therapy which has been found to be highly effective. Recently the US Food and Drug Administration has issued emergency use authorization to treat hospitalized COVID-19 patients with convalescent plasma from people who have recovered from the virus. Convalescent plasma is the liquid portion of the blood that contains the antibodies an individual develops in response to an infection and can be given to patients currently fighting that virus. This treatment has long been a part of the infectious disease arsenal. It has already been in use for COVID-19 for a number of months: The Mayo Clinic has run an “expanded access program for convalescent plasma since March, and more than 70,000 people have received the treatment. It is found that there is a 35% improvement in mortality rate for COVID-19 patients given the plasma.

- Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine.

This is a long standing anti -malarial drug which has been used for nearly a century. However, there is a fraction of the medical community which maintain this is not an effective solution. In fact there are many people who have used it for long periods just for the prevention of malaria. For them no ill effects have been observed. So this has led to an almost political dialogue. Some say it may cause heart problems but otherwise it has been widely used across all continents with no serious effects.

- Ventilators and oxygen supplements may be used for breathing

VACCINES FOR COVID-19 [5]

It is only natural that we resort to a universal vaccine to solve the pandemic problem. But the scale of the problem given the population size of each country is gigantic. More than 150 companies are desperately competing working drastically to produce a vaccine by the end of 2020. Following are the prominent candidates but which will succeed?

The basic idea of all those vaccines is to instruct one’s immune system to mount a defense, which is sometimes stronger than what would be provided through natural infection and hopefully comes with fewer health consequences.

To do so, some vaccines use the whole coronavirus, but in a killed or weakened state. Others use only part of the virus – whether protein or a fragment. Some transfer the protein into a different virus.

Finally some use pieces of the virus’s genetic material so as to temporarily make the right proteins to stimulate the immune system.

Even when a vaccine has been chemically produced, it faces still a tortuous path to the final usable product. Vaccines have to go through a multi – stage clinical trial process. First phase starts by checking for their safety and whether they trigger an immune response to a small group of healthy individuals. Second phase finds a wider group of those who are likely to catch the virus and to gauge how effective it is. The third phase expands the group to thousands of people to make sure it is safe and effective, given that the immune response varies by age, ethnicity or underlying health conditions.

It then goes to various regulatory agencies for approval. This may take years.

Following are some of the prominent companies. There is much in common between the various companies. Most use the SARS-CoV2 protein to trigger the immune response

== Moderna Therapeutics

Name: mRNA-1273

DNA is the gene and ~RNA gives instructions for certain proteins. A mRNA vaccine is the instruction for the SARS-CoV2 protein. Once inside the cell, the protein is made and that triggers the immune response

Who: A Massachusetts-based biotech company, in collaboration with the US National Institutes of Health.

This vaccine candidate relies on injecting snippets of a virus’s genetic material, in this case mRNA, into human cells. They create viral proteins that mimic the coronavirus, training the immune system to recognize its presence.

STATUS: The third phase has started in a deal with the Swiss company Lonza. It is hoped to manufacture up to one billion doses a year.

Name: BNT162b2

WHO : One of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies, based in New York in collaboration with German biotech BioNTech.

WHAT: Also an mRNA vaccine based on cancer vaccine.

STATUS : Currently combining phase 2 and 3 on a diverse population in 30,000 people from 39 US states and from Brazil, Argentina, and Germany. Hope to supply 1.3 billion doses by end of 2021.

== University of Oxford

Name: ChAdOx1 nCoV-19

Who: The U.K. university in collaboration with AstraZeneca.

What: Oxford’s candidate is what’s known as a viral vector vaccine, essentially a “Trojan horse ” presented to the immune system. Oxford’s research team has transferred the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein—which helps the coronavirus invade cells—into a weakened version of an adenovirus, which typically causes the common cold. When this adenovirus is injected into humans, the hope is that the spike protein will trigger an immune response. AstraZeneca and Oxford plan to produce a billion doses of vaccine that they’ve agreed to sell at cost.

Status: Preliminary results from this candidate’s first two clinical trial phases revealed that the vaccine had triggered a strong immune response—including increased antibodies and responses from T-cells—with only minor side effects such as fatigue and headache. It has now moved into phase three of clinical trials, aiming to recruit up to 50,000 volunteers in Brazil, the UK, USA and South Africa.

Recently it has been found that one volunteer in the test phase of AstreZeneca has contracted inflammation of the spine. It is not known whether this is related to the vaccine or an independent coincidence. So the whole test phase has been put on hold until further investigation.

==. Sinovac

Name: CoronaVac

Who: A Chinese biopharmaceutical company, in collaboration with Brazilian research center Butantan.

What: CoronaVac is an inactivated vaccine, meaning it uses a non-infectious version of the coronavirus. While inactivated pathogens can no longer produce disease, they can still provoke an immune response, such as with the annual influenza vaccine.

Status: On July 3, Brazil’s regulatory agency granted this vaccine candidate approval to move ahead to phase three, as it continues to monitor the results of the phase two clinical trials. The first phases have so far shown that the vaccine does produce an immune response with no severe adverse effects. Preliminary results of this candidate’s earlier testing in macaque monkeys, published in Science , revealed that the vaccine produced antibodies that neutralized 10 strains of SARS-CoV-2. Phase three will recruit nearly 9,000 healthcare professionals in Brazil.

== Sinopharm

Who: China’s state-run pharmaceutical company, in collaboration with the Wuhan Institute of Biological Products. Wuhan Institute is where the virus initially started. There has been much resentment outside China, especially in the US, that China initially limited the movement of people from Wuhan but failed to let travelers go outside internationally. In this way the virus took hold in Europe and then in USA. The spread of the virus all over the world has led to countless cases and deaths. Not to mention the economic and social disruption it has caused the whole world, China should be made accountable for the gigantic disruption and suffering it has caused to the whole planet!

What: Sinopharm is also using an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine that it hopes will reach the public by the end of 2020 . Sinopharm has reported that early trials of its vaccine candidate triggered a strong neutralizing antibody response in participants, with no serious adverse effects.

Status: In mid-July, Sinopharm launched its phase three trial among 15,000 volunteers—aged 18 to 60, with no serious underlying conditions—in the United Arab Emirates. The company selected the UAE , as it has a diverse population with approximately 200 different nationalities, making it an ideal testing ground.

==. Murdoch Children’s Research Institute

Name: Bacillus Calmette-Guerin BRACE trial

Who: The largest child health research institute in Australia, in collaboration with the University of Melbourne.

What: For nearly a hundred years, the Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine has been used to prevent tuberculosis by exposing patients to a small dose of live bacteria . Evidence has emerged over the years that this vaccine may boost the immune system and help the body fight off other diseases as well. Researchers are investigating whether these benefits may also extend to SARS-CoV-2,

Status: This trial has reached phase three in Australia. It has begun a series of randomized controlled trials that will test whether BCG might work on the coronavirus as well. They aim to recruit 10,000 healthcare workers in the study.

==. CanSino Biologics

Name: Ad5-nCoV

Who: A Chinese biopharmaceutical company.

What: CanSino has also developed a viral vector vaccine, using a weakened version of the adenovirus as a vehicle for introducing the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to the body. Preliminary results from phase two trials have shown that the vaccine produces “significant immune responses in the majority of recipients after a single immunization.” There were no serious adverse reactions documented.

Status: Though the company is still technically in phase two of its trial, on June 25, CanSino became the first company to receive limited approval to use its vaccine in people. The Chinese government has approved the vaccine for military use only, for a period of one year.

==. The Gamaleya National Center of Epidemiology and Microbiology

Name: Sputnik V

Who: This is the only Russian vaccine research institution which is in collaboration with the state-run Russian Direct Investment Fund.

What: Gamaleya has developed a viral vector vaccine that also uses a weakened version of the common cold-causing adenovirus to introduce the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to the body. This vaccine uses two strains of adenovirus, and it requires a second injection after 21 days to boost the immune response. Russia has not published any data from its clinical trials, but officials with the institute state that they have completed phases one and two. The researchers also claim the vaccine produced strong antibody and cellular immune responses.

Status: Despite the lack of published evidence, Russia has cleared the Sputnik V vaccine for widespread use and claimed it as the first registered COVID-19 vaccine on the market. Russia reports that it will start phase three clinical trials on August 12 ; the World Health Organization, however, lists the Sputnik V vaccine as being in phase one of clinical trials.

Even when a vaccine is approved, there is the problem of manufacturing, distribution, scaling up of the production and deciding who should get it first. Many vaccines go through the 4th phase of regular study. This can take long time. Then what about the cost? The US government has pledged $10 billion with Pfizer to develop 300 million doses by beginning of 2021, And World Health Organization, WHO, is aiming to deliver 2 billion doses by the end of 2021. It is truly a worldwide effort in the race to produce vaccines to fight and eradicate the pandemic. The companies are located in Australia, Russia, Germany, Brazil, Switzerland, UK, USA and of course China. We hope that the ingenuity of the world’s brilliant scientists and technicians as well as the experience and organized know how of our governments and social systems will lead us through this pandemic by the end of 2020.

Gioietta Kuo, MA at Cambridge, PhD in nuclear physics, Atlas Fellow at St Hilda’s College, Oxford and Princeton University plasma physics lab, is a research physicist. Over 70 professional articles and over 100 articles in environmental problems – in World Future Society-wfs.org, amcips.org, MAHB Stanford and other worldwide think tanks. Also in Chinese in ‘ People’s Daily’ and ‘World Environment’ – Magazine of the Chinese Ministry of Environmental Protection, and others in China. She can be reached at < [email protected] .>

[1] Coronavirus Update (Live): 23,272,847 Cases and 805,907 … https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

[2] Herd immunity and COVID-19 (coronavirus): What you need to … https://www.mayoclinic.org/herd-immunity-and-coronavirus/art-20486808

[3] Croatia Coronavirus: 7,900 Cases and 170 Deaths …

https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/croatia/

[4] FDA Authorizes Convalescent Plasma As Emergency … https://www.capradio.org/news/npr/story?storyid=905277083 1 day ago … https://www.capradio.org/news/npr/story?storyid=905277083 1 day ago …

[5] https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/expert-answers/coronavirus-drugs

COVID-19 (coronavirus) drugs: Are there any that work …

[6] CORONAVIRUS UPDATE: Here’s what you should know about the vaccines in development

National Geographic 2020

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/health-and-human-body/human-diseases/coronavirus-vaccine-tracker-how-they-work-latest-developments-cvd/

How to Write About Coronavirus in a College Essay

Students can share how they navigated life during the coronavirus pandemic in a full-length essay or an optional supplement.

Writing About COVID-19 in College Essays

Getty Images

Experts say students should be honest and not limit themselves to merely their experiences with the pandemic.

The global impact of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, means colleges and prospective students alike are in for an admissions cycle like no other. Both face unprecedented challenges and questions as they grapple with their respective futures amid the ongoing fallout of the pandemic.

Colleges must examine applicants without the aid of standardized test scores for many – a factor that prompted many schools to go test-optional for now . Even grades, a significant component of a college application, may be hard to interpret with some high schools adopting pass-fail classes last spring due to the pandemic. Major college admissions factors are suddenly skewed.

"I can't help but think other (admissions) factors are going to matter more," says Ethan Sawyer, founder of the College Essay Guy, a website that offers free and paid essay-writing resources.

College essays and letters of recommendation , Sawyer says, are likely to carry more weight than ever in this admissions cycle. And many essays will likely focus on how the pandemic shaped students' lives throughout an often tumultuous 2020.

But before writing a college essay focused on the coronavirus, students should explore whether it's the best topic for them.

Writing About COVID-19 for a College Application

Much of daily life has been colored by the coronavirus. Virtual learning is the norm at many colleges and high schools, many extracurriculars have vanished and social lives have stalled for students complying with measures to stop the spread of COVID-19.

"For some young people, the pandemic took away what they envisioned as their senior year," says Robert Alexander, dean of admissions, financial aid and enrollment management at the University of Rochester in New York. "Maybe that's a spot on a varsity athletic team or the lead role in the fall play. And it's OK for them to mourn what should have been and what they feel like they lost, but more important is how are they making the most of the opportunities they do have?"

That question, Alexander says, is what colleges want answered if students choose to address COVID-19 in their college essay.

But the question of whether a student should write about the coronavirus is tricky. The answer depends largely on the student.

"In general, I don't think students should write about COVID-19 in their main personal statement for their application," Robin Miller, master college admissions counselor at IvyWise, a college counseling company, wrote in an email.

"Certainly, there may be exceptions to this based on a student's individual experience, but since the personal essay is the main place in the application where the student can really allow their voice to be heard and share insight into who they are as an individual, there are likely many other topics they can choose to write about that are more distinctive and unique than COVID-19," Miller says.

Opinions among admissions experts vary on whether to write about the likely popular topic of the pandemic.

"If your essay communicates something positive, unique, and compelling about you in an interesting and eloquent way, go for it," Carolyn Pippen, principal college admissions counselor at IvyWise, wrote in an email. She adds that students shouldn't be dissuaded from writing about a topic merely because it's common, noting that "topics are bound to repeat, no matter how hard we try to avoid it."

Above all, she urges honesty.

"If your experience within the context of the pandemic has been truly unique, then write about that experience, and the standing out will take care of itself," Pippen says. "If your experience has been generally the same as most other students in your context, then trying to find a unique angle can easily cross the line into exploiting a tragedy, or at least appearing as though you have."

But focusing entirely on the pandemic can limit a student to a single story and narrow who they are in an application, Sawyer says. "There are so many wonderful possibilities for what you can say about yourself outside of your experience within the pandemic."

He notes that passions, strengths, career interests and personal identity are among the multitude of essay topic options available to applicants and encourages them to probe their values to help determine the topic that matters most to them – and write about it.

That doesn't mean the pandemic experience has to be ignored if applicants feel the need to write about it.

Writing About Coronavirus in Main and Supplemental Essays

Students can choose to write a full-length college essay on the coronavirus or summarize their experience in a shorter form.

To help students explain how the pandemic affected them, The Common App has added an optional section to address this topic. Applicants have 250 words to describe their pandemic experience and the personal and academic impact of COVID-19.

"That's not a trick question, and there's no right or wrong answer," Alexander says. Colleges want to know, he adds, how students navigated the pandemic, how they prioritized their time, what responsibilities they took on and what they learned along the way.

If students can distill all of the above information into 250 words, there's likely no need to write about it in a full-length college essay, experts say. And applicants whose lives were not heavily altered by the pandemic may even choose to skip the optional COVID-19 question.

"This space is best used to discuss hardship and/or significant challenges that the student and/or the student's family experienced as a result of COVID-19 and how they have responded to those difficulties," Miller notes. Using the section to acknowledge a lack of impact, she adds, "could be perceived as trite and lacking insight, despite the good intentions of the applicant."

To guard against this lack of awareness, Sawyer encourages students to tap someone they trust to review their writing , whether it's the 250-word Common App response or the full-length essay.

Experts tend to agree that the short-form approach to this as an essay topic works better, but there are exceptions. And if a student does have a coronavirus story that he or she feels must be told, Alexander encourages the writer to be authentic in the essay.

"My advice for an essay about COVID-19 is the same as my advice about an essay for any topic – and that is, don't write what you think we want to read or hear," Alexander says. "Write what really changed you and that story that now is yours and yours alone to tell."

Sawyer urges students to ask themselves, "What's the sentence that only I can write?" He also encourages students to remember that the pandemic is only a chapter of their lives and not the whole book.

Miller, who cautions against writing a full-length essay on the coronavirus, says that if students choose to do so they should have a conversation with their high school counselor about whether that's the right move. And if students choose to proceed with COVID-19 as a topic, she says they need to be clear, detailed and insightful about what they learned and how they adapted along the way.

"Approaching the essay in this manner will provide important balance while demonstrating personal growth and vulnerability," Miller says.

Pippen encourages students to remember that they are in an unprecedented time for college admissions.

"It is important to keep in mind with all of these (admission) factors that no colleges have ever had to consider them this way in the selection process, if at all," Pippen says. "They have had very little time to calibrate their evaluations of different application components within their offices, let alone across institutions. This means that colleges will all be handling the admissions process a little bit differently, and their approaches may even evolve over the course of the admissions cycle."

Searching for a college? Get our complete rankings of Best Colleges.

10 Ways to Discover College Essay Ideas

Tags: students , colleges , college admissions , college applications , college search , Coronavirus

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

College Admissions: Get a Step Ahead!

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S. News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

Ask an Alum: Making the Most Out of College

You May Also Like

10 destination west coast college towns.

Cole Claybourn May 16, 2024

Scholarships for Lesser-Known Sports

Sarah Wood May 15, 2024

Should Students Submit Test Scores?

Sarah Wood May 13, 2024

Poll: Antisemitism a Problem on Campus

Lauren Camera May 13, 2024

Federal vs. Private Parent Student Loans

Erika Giovanetti May 9, 2024

14 Colleges With Great Food Options

Sarah Wood May 8, 2024

Colleges With Religious Affiliations

Anayat Durrani May 8, 2024

Protests Threaten Campus Graduations

Aneeta Mathur-Ashton May 6, 2024

Protesting on Campus: What to Know

Sarah Wood May 6, 2024

Lawmakers Ramp Up Response to Unrest

Aneeta Mathur-Ashton May 3, 2024

- Open access

- Published: 07 April 2020

Fighting against the common enemy of COVID-19: a practice of building a community with a shared future for mankind

- Xu Qian 1 ,

- Ran Ren 2 ,

- Youfa Wang 3 ,

- Yan Guo 4 ,

- Jing Fang 5 ,

- Zhong-Dao Wu 6 ,

- Pei-Long Liu 4 ,

- Tie-Ru Han 7 &

Members of Steering Committee, Society of Global Health, Chinese Preventive Medicine Association

Infectious Diseases of Poverty volume 9 , Article number: 34 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

196k Accesses

86 Citations

23 Altmetric

Metrics details

The outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has caused more than 80 813 confirmed cases in all provinces of China, and 21 110 cases reported in 93 countries of six continents as of 7 March 2020 since middle December 2019. Due to biological nature of the novel coronavirus, named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) with faster spreading and unknown transmission pattern, it makes us in a difficulty position to contain the disease transmission globally. To date, we have found it is one of the greatest challenges to human beings in fighting against COVID-19 in the history, because SARS-CoV-2 is different from SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV in terms of biological features and transmissibility, and also found the containment strategies including the non-pharmaceutical public health measures implemented in China are effective and successful. In order to prevent a potential pandemic-level outbreak of COVID-19, we, as a community of shared future for mankind, recommend for all international leaders to support preparedness in low and middle income countries especially, take strong global interventions by using old approaches or new tools, mobilize global resources to equip hospital facilities and supplies to protect noisome infections and to provide personal protective tools such as facemask to general population, and quickly initiate research projects on drug and vaccine development. We also recommend for the international community to develop better coordination, cooperation, and strong solidarity in the joint efforts of fighting against COVID-19 spreading recommended by the joint mission report of the WHO-China experts, against violating the International Health Regulation (WHO, 2005), and against stigmatization, in order to eventually win the battle against our common enemy — COVID-19.

A sudden outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus has happened since December 2019 in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, a central city in the People’s Republic of China, where transportation is enormously convenient to connecting all other places in China and overseas [ 1 , 2 ]. As of 7 March, 2020, a total of 80 813 confirmed cases reported in all provinces of China, and 21 110 cases reported in 93 countries/territories/areas of six continents [ 3 ]. In particular, some cases have been confirmed in African countries, such as Algeria, Egypt, and Nigeria [ 3 ]. This is the biggest infectious disease outbreak in China ever since 1949, the year of founding the People’s Republic of China. It is the biggest battle since the disease is spreading so fast with high prevalence, and the prevention of the transmission has involved all people in the country [ 4 ]. While at global level, the strategy and coordinating mechanism to control COVID-19 need to be set down as soon as possible [ 5 ], in particular, three questions need to be addressed as (i) how to take the emergency response actions effectively in different countries? (ii) how to mobilize resources quickly with strategic ways? and (iii) how to encourage people proactively and orderly to participate in this battle against COVID-19 from different regions of the world?

Lessons from the battle against COVID-19 in China

In order to address three aforementioned questions, the lessons from China in the battle against COVID-19 need to be understood clearly in the following three aspects:

Traditional epidemiological approaches effectively control the transmission

Professionally speaking, three steps are necessary to taken once an infectious disease outbreaks in certain regions, including controlling infectious sources, blocking the transmission routes, and protecting the susceptive population [ 6 ]. While, as COVID-19 spreading so fast and people’s travelling so frequent during the Chinese New Year (Spring Festival) season, it cannot control effectively if only taking the normal or general countermeasures [ 7 ]. Therefore, the Chinese government has quickly taken actions to contain its transmission inside China, including detecting the disease early, diagnosis and reporting early, isolating and treatment of cases early, tracing all possible contacts, persuading people to stay at home, and promoting social distancing measures commensurate with the risk, etc., based on the current knowledge about epidemiological features and transmission patterns of COVID-19.

Response strategies coping with local conditions

In dealing with the outbreak, China has been adopting the way of tailoring interventions into local settings, from quickly finding each infected person, tracing close contacts and placing them under quarantine, to promoting basic hygiene measures to the public, such as frequent hand washing, cancelling public gathering, closing schools, extending the Spring Festival holiday, delaying return to work, and to the most severe measure of city lockdown of Wuhan [ 8 , 9 ]. By adapting response strategies to the local context, it may avoid blockading the city when it is not needed, and also prevent from a major outbreak without taking any action.

Mobilizing resources quickly to support the emergency responses

Under the strong leadership of the Central Government of China, the mobilization for the emergency responses has been effectively promoted in following ways. Firstly, a Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism of the State Council has established involving 32 Ministries, with subgroups on control of outbreak, medical rescue, scientific research, information and communication, international cooperation, logistics, and frontline coordination [ 10 ]. This multi-sectoral cooperation mechanism at high level is to ensure the facilities and supplies have been well arranged to support the emergency responses in all provinces, with focus on the Hubei Province, for example, more than 10 mobile hospitals and two big hospitals with each one having the capacity of holding more than 1000 beds have been built within 10 days. Secondly, more than 40 000 medical professionals from other provinces or military institutions have been dispatched to Hubei Province to implement emergency responses, including medical care and treatment, epidemiological investigations, environmental sterilization for disinfection, and data and information management to support the policy making.

Encouraging people proactively and orderly participate in this battle against COVID-19

It is important to protect the community from exposure to the infection, all residents in the potential risk areas were encouraged to stay at home, which is an effective way to block the transmission routes. Local community health workers and volunteers, after the specific training, proactively participate in screening the suspicious infections, and help in implementing proper quarantine measures by providing support services, such as driving patients to the mobile hospitals [ 8 ]. All those activities logistically managed at the community level.

At the same time, from medical care side, the medical doctors and nurses worked very hard in the hospitals, to screen the suspected cases, provide medical care for the confirmed cases, and taking emergency response to rescue severe patients to reduce the fatality. While epidemiologists working in centers for disease control and preventions provided the statistical results for the dissemination of epidemiological data correctly, and provide the well-prepared datasets for the decision makers for coordination of necessary resources, and many health workers investigate the suspected contactors for quick medical quarantine of the suspected cases at the community level.

Preventing the pandemic of COVID-19

With the conceptualization on building a community with a shared future for mankind proposed by Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2013 [ 11 ], Chinese people have taken following actions to prevent the pandemic of the diseases: (i) sharing the sequences of SARS-Cov-2 virus with the World Health Organization (WHO) and other countries which are important information for other countries to prepare the tests for screening and diagnosis, (ii) all epidemiological data with clinical treatment in China has been published in the international journals, (iii) prevent spreading of the disease by traveling ban in Wuhan, (iv) medical quarantine has been performed for all suspected contactors, (v) body temperature measuring facilities were equipped in all railway stations and airports, etc. In order to take very strict contain measures for COVID-19 outbreak tailored to local settings, the travelling ban was executed in Wuhan, and encouraging no gathering and less travelling in other cities out of Hubei Province. Those actions were implemented by strong coordinating of the Chinese government in cooperation with local residents. To date, the epidemiological data has showed more than thousands of people have been protected from the infections, and increasing pattern of the transmission has been suppressed significantly in China [ 12 ].

Challenges in fighting against COVID-19

The fighting against COVID-19 has been lasting almost two months, and the time left for people outside of China to prepare the countermeasures has been narrowed quickly. To date, we have found it is one of the greatest challenges to human beings in fighting against COVID-19 in the history, since the pathogen of SARS-CoV-2 is a new coronavirus, differed from either SARS-CoV or MERS-CoV in terms of biological characteristics and transmissibility [ 13 ].

Technically, we have little knowledge on the pathogen and pathogenesis, without specific effectively drugs or vaccine against the virus infection, which cause difficulties in rescuing the severe cases which account for about 20% of the infections. The transmission routes are not clear enough, although we currently understand that the respiratory transmission from human to human is the major transmission route, but other ways for transmission, such as gastrointenstinal transmission or aerosol propagation, is not so clear.

Administratively, implementing the locked down measures in such a big city with over 15 millions of people is not an easy task, with a lot of preparing works from different dimensions of municipal logistic management, to support the emergency response actions. Thus, the multi-administrative systems need to be coordinated collectively, guiding from the central government, with more resources gathering from various places all over the country.

Globally, the information sharing is so important, including patients’ information sharing to trace the suspected cases to protect more people as quickly as possible, genome sequences information sharing to prepare the diagnostics as quickly as possible, and treatment schemes sharing to rescue more severe cases. The WHO declared the Public Health Emergency of International Concern based on the International Health Regulation (2005) in the early time of the outbreak of COVID-19, as it is an extraordinary event to constitute a public health risk to the states through the international spread of disease, and to potentially require a coordinate international response [ 14 ]. All actions to strengthen surveillance and response systems on infectious diseases need to put emphasis on resources limited countries, such as Southeast Asia and African countries [ 15 ].

Recommendations

With understanding more about the nature of COVID-19, it is necessary to understand clearly the current challenges against COVID-19 become increasing, not only to China but also to the world. In order to take quick actions to early prepare the battle against COVID-19 and better allocate enough health resources from the world, the recommendations are as follows:

Coordinating interventions and resources mobilization globally

Preparedness in low and middle income countries.

WHO has identified 13 African countries at the top-risk affected by COVID-19 but with limited resources against COVID-19, including Algeria, Angola, Cote d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Mauritius, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia. These countries have direct links or greater numbers of people travelling to/from China [ 15 ]. The preparing works on response to the imported cases need initiated as soon as possible with the assistance of WHO as well as developed world. The major preparing works are to prepare enough facilities for use in hospitals, such as test kits, facemasks, and personal protective equipment (PPE), to prepare the quarantine measures in each gate of the traveling venues, and to prepare information communication, etc. The emergency response mechanism on multi-sectoral cooperation needs to be established once the first case has been detected.

Intervention and coordination globally

The fast spreading of COVID-19 to more than 90 countries/territories, with some cluster cases occurred in a few countries, demonstrated that this new disease has higher transmissibility compared with SARS and MERS. The nature of high transmissibility for COVID-19 requires us to (i) prepare the battle globally as soon as possible, by taking the advantage of the time window opened by Chinese battle against COVID-19, (ii) invest more weapons or tools against the diseases by better global coordination, and (iii) take proper quarantine measures globally [ 16 ]. We are able to win the battle only if our actions are coordinated better at a global level.

Resources mobilization globally

One of lessons learnt from the battle in Wuhan is the speed of resources gathering against COVID-19 outbreak could not catch up the speed of the coronavirus spreading in early stage of the outbreak, and it is in need of support or assistances from outside of epicenter, including medical doctors, nurses, and facilities of PPE used in hospitals, and facemasks for residents. The strong support from outside of epicenter quickly to ensure all infectious sources either controlled through quarantine measures or treated in the specialized hospitals. Therefore, for those countries with weak health system, it is so urgent to get help from other parts of the world. WHO needs to mobilize its certified global emergency medical teams to get ready to be dispatched to other countries where health workers are in short supply while an outbreak occurs.

Jointly fighting against common enemy ─ COVID-19

As said by WHO Director-General in the news press on Public Health Emergency of International Concern declaration that “this declaration is not a vote of no confidence in China, our greatest concern is the potential for the virus to spread to countries with weaker health systems.” Therefore, international community needs to work together to prepare for the containment of COVID-19 transmission and spreading in other countries, under the scenario that more countries may be affected by the new coronavirus [ 17 ]. These containment works have to quickly take readiness on active surveillance, early detection, isolation and case management, contact tracing and prevention of onward spread of COVID-19.

Therefore, at this stage, with more countries having confirmed more and more COVID-19 cases, all countries need work together on the following global actions on:

fighting against COVID-19 spreading, including sharing the information of the disease transmission and epidemiological knowledge, sharing the experiences on case management and treatment approaches both for severe cases or light symptoms, and sharing new technologies or strategies to contain the transmission;

fighting against violating International Health Regulation, by following the WHO’s authoritative advices which called on all countries to implement decisions that are evidence-based and convincing. We need to improve our quarantine measures to replace the disconnection of international traveling and trade restrictions, with an assistance of the improved active surveillance systems and AI-based technology to trace the contactors;

fighting against stigmatization, since the stigmatization is always present when the disease outbreak and people facing the sudden attack of this kind of epidemic. These phenomena on stigmatization may be at a scale of epicenter areas, or may be at a country and regional scale, and even at global scale. Thus, we need fight with the real and common enemy which is the new coronavirus, rather than the infected people. The international community needs the solidarity and sympathy to start the battle against the common enemy – the new coronavirus, as well as against stigmatization at the same time.

Global cooperation in priority settings

By considering COVID-19 is spreading so fast which causes difficulties in containing the disease, we, as a community of shared future for mankind, need better coordination in global cooperation and further improvement in the multi-sectoral cooperation in order to quickly take response and prevent from the pandemic [ 18 ]. In addition, we also need better coherence of our resources with more international partners, at least, we can quickly improve our priority settings in sharing information and data, on research priority settings, on surveillance and response to outbreaks at a global level.

Cooperation on sharing information and data

In order to quickly share the information and datasets for countermeasures, the actions on fast and open reporting of outbreak data and sharing of virus samples, genetic information, and research results are encouraged for all international communities, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), as well as governmental institutions around the world. Through regional and country office of WHO, more preventive information against COVID-19 can be disseminated to the public in the vulnerable countries.

Coordination on surveillance and response

With understanding the importance of human health in the planet, multi-sectoral and multi-lateral cooperation against COVID-19 pandemic are recommended at global level. Particularly, the scientific communities, governments and NGOs in different fields, such as public health, agriculture, ecology, epidemiology, governance planning, science, and many others need to collaboratively prevent future outbreaks, with better coordination. The secretary of the United Nations need take the responsibility to coordinate the actions on protecting the planetary health by systematic approaches, such as EcoHealth, One Health, Planetary Health and Urban Health, and making sure public resources are worthwhile investing in strengthening surveillance and response systems for preventing future outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases.

Coherence on research priority settings

We urgently encourage all governments and international foundation to support short-term and emergency response-related research projects to improve our understanding of the causes, risks, infectiousness, and threats of a pandemic [ 19 ]. Health institutions at international level should be encouraged to organize the research priority settings on preventing the pandemic or averting the emergence of the disease. International conservation organizations start to take investigations on types of wildlife-pathogens interactions affecting human health. International environmental agencies can initiate researches on unsustainable transformations of natural environments and ecosystems that provide life-supporting services for our health.

Conclusions

To summarize, COVID-19 is a new disease that has caused great impacts to the people’s daily life extraordinarily. We, as a community of shared future for mankind, need to take collectively and quickly strong emergency responses as a battle against our common enemy, the new coronavirus, not only in China but also in the world. All partners of international community and country leaders are encouraged to proactively take strategic actions as soon as possible to fight the COVID-19 together. Hard times will end finally, and we will meet each other in the blooming spring soon.

Availability of data and materials

All data supporting the findings of this study are included in the article.

Abbreviations

Coronavirus disease 2019

Novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus

Non-governmental organizations

World Health Organization

Personal protective equipment

Wu YC, Chen CS, Chan YJ. Overview of the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV): the pathogen of severe specific contagious pneumonia (SSCP). J Chin Med Assoc. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCMA.0000000000000270 .

Wu F, Zhao S, Yu B, Chen YM, Wang W, Song ZG, et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature . 2020;579:265–9.

Article CAS Google Scholar

World Health Organization: Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation Report-47. In . Edited by World Health Organization. Geneva. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200307-sitrep-47-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=27c364a4_2 . Accessed 8 March 2020.

Zhao S, Lin Q, Ran J, Musa SS, Yang G, Wang W, et al. Preliminary estimation of the basic reproduction number of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in China, from 2019 to 2020: a data-driven analysis in the early phase of the outbreak. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;92:214–7.

Wang FS, Zhang C. What to do next to control the 2019-nCoV epidemic? Lancet . 2020;395(10222):391–3.

Article Google Scholar

TNCPERE. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) — China, 2020. China CDC Weekly. 2020;2(8):113–22.

Google Scholar

Zhao S, Zhuang Z, Ran J, Lin J, Yang G, Yang L, He D. The association between domestic train transportation and novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak in China from 2019 to 2020: a data-driven correlational report. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;33:101568.

General Administration of Quality Supervision: Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China, Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China. GB 19193–2015 Beijing: Standards Press of China; 2016.

Wilder-Smith A, Freedman DO. Isolation, quarantine, social distancing and community containment: pivotal role for old-style public health measures in the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. J Travel Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taaa020 .

Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism of the State Council. http://society.people.com.cn/n1/2020/0122/c1008-31559160.html . 2020.

Hu R, Liu R, Hu N. China's belt and road initiative from a global health perspective. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(8):e752–3.

China-WHO Expert Team. Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Beijing; 2020.

Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–13.

World Health Organization. Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Geneva: World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov) . Accessed 8 March 2020.

Gilbert M, Pullano G, Pinotti F, Valdano E, Poletto C, Boelle PY, et al. Preparedness and vulnerability of African countries against importations of COVID-19: a modelling study. Lancet. 2020;395:871–7.

Chen T, Rui J, Wang Q, Zhao ZY, Cui JA, Yin L. A mathematical model for simulating the phase-based transmissibility of a novel coronavirus. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9:24.

Calisher C, Carroll D, Colwell R, Corley RB, Daszak P, Drosten C, et al. Statement in support of the scientists, public health professionals, and medical professionals of China combatting COVID-19. Lancet . 2020;395:E42–3.

Sullivan AD, Strickland CJ, Howard KM. Public health emergency preparedness practices and the management of frontline communicable disease response. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2020;26(2):180–3.

Thompson R. Pandemic potential of 2019-nCoV. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30068-2 .

Download references

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Public Health/Global Health Institute, Fudan University, Shanghai, 200032, China

Global Health Center, Dalian Medical University, Dalian, 116021, China

Global Health Institute, School of Public Health, Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an, 710061, China

Global Health Center, School of Public Health, Beijing University, Beijing, 100871, China

Yan Guo & Pei-Long Liu

Kunming Medical University, Yunnan, 650500, China

Zhongshan School of Medicine, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, 510080, China

Zhong-Dao Wu

Society of Global Health, Chinese Preventive Medicine Association, Beijing, 100013, China

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

- Zong-Fu Mao

- , Tian-Ping Wang

- , Jia-Hui Zhang

- , Qing-Min Zhang

- , Zhao-Yang Zhang

- , Hong-Ning Zhou

- & Feng Chen

Contributions

QX, RR, WYF, GY, FJ, WZD, LPL, and HTR conceived the paper. QX, RR, WYF, and LPL performed the literature search, prepared the figures, and interpreted the data. QX wrote the first version of the manuscript. QX, RR, WYF, GY, and LPL assisted in the restructuring and revision of the manuscript. All authors read, contributed to, and approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Xu Qian or Tie-Ru Han .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Qian, X., Ren, R., Wang, Y. et al. Fighting against the common enemy of COVID-19: a practice of building a community with a shared future for mankind. Infect Dis Poverty 9 , 34 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-020-00650-1

Download citation

Received : 29 February 2020

Accepted : 20 March 2020

Published : 07 April 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-020-00650-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Preparedness

- International health regulation

Infectious Diseases of Poverty

ISSN: 2049-9957

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

The complexity of managing COVID-19: How important is good governance?

- Download the essay

Subscribe to Global Connection

Alaka m. basu , amb alaka m. basu professor, department of global development - cornell university, senior fellow - united nations foundation kaushik basu , and kaushik basu nonresident senior fellow - global economy and development @kaushikcbasu jose maria u. tapia jmut jose maria u. tapia student - cornell university.

November 17, 2020

- 13 min read

This essay is part of “ Reimagining the global economy: Building back better in a post-COVID-19 world ,” a collection of 12 essays presenting new ideas to guide policies and shape debates in a post-COVID-19 world.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the inadequacy of public health systems worldwide, casting a shadow that we could not have imagined even a year ago. As the fog of confusion lifts and we begin to understand the rudiments of how the virus behaves, the end of the pandemic is nowhere in sight. The number of cases and the deaths continue to rise. The latter breached the 1 million mark a few weeks ago and it looks likely now that, in terms of severity, this pandemic will surpass the Asian Flu of 1957-58 and the Hong Kong Flu of 1968-69.

Moreover, a parallel problem may well exceed the direct death toll from the virus. We are referring to the growing economic crises globally, and the prospect that these may hit emerging economies especially hard.

The economic fall-out is not entirely the direct outcome of the COVID-19 pandemic but a result of how we have responded to it—what measures governments took and how ordinary people, workers, and firms reacted to the crisis. The government activism to contain the virus that we saw this time exceeds that in previous such crises, which may have dampened the spread of the COVID-19 but has extracted a toll from the economy.

This essay takes stock of the policies adopted by governments in emerging economies, and what effect these governance strategies may have had, and then speculates about what the future is likely to look like and what we may do here on.

Nations that build walls to keep out goods, people and talent will get out-competed by other nations in the product market.

It is becoming clear that the scramble among several emerging economies to imitate and outdo European and North American countries was a mistake. We get a glimpse of this by considering two nations continents apart, the economies of which have been among the hardest hit in the world, namely, Peru and India. During the second quarter of 2020, Peru saw an annual growth of -30.2 percent and India -23.9 percent. From the global Q2 data that have emerged thus far, Peru and India are among the four slowest growing economies in the world. Along with U.K and Tunisia these are the only nations that lost more than 20 percent of their GDP. 1

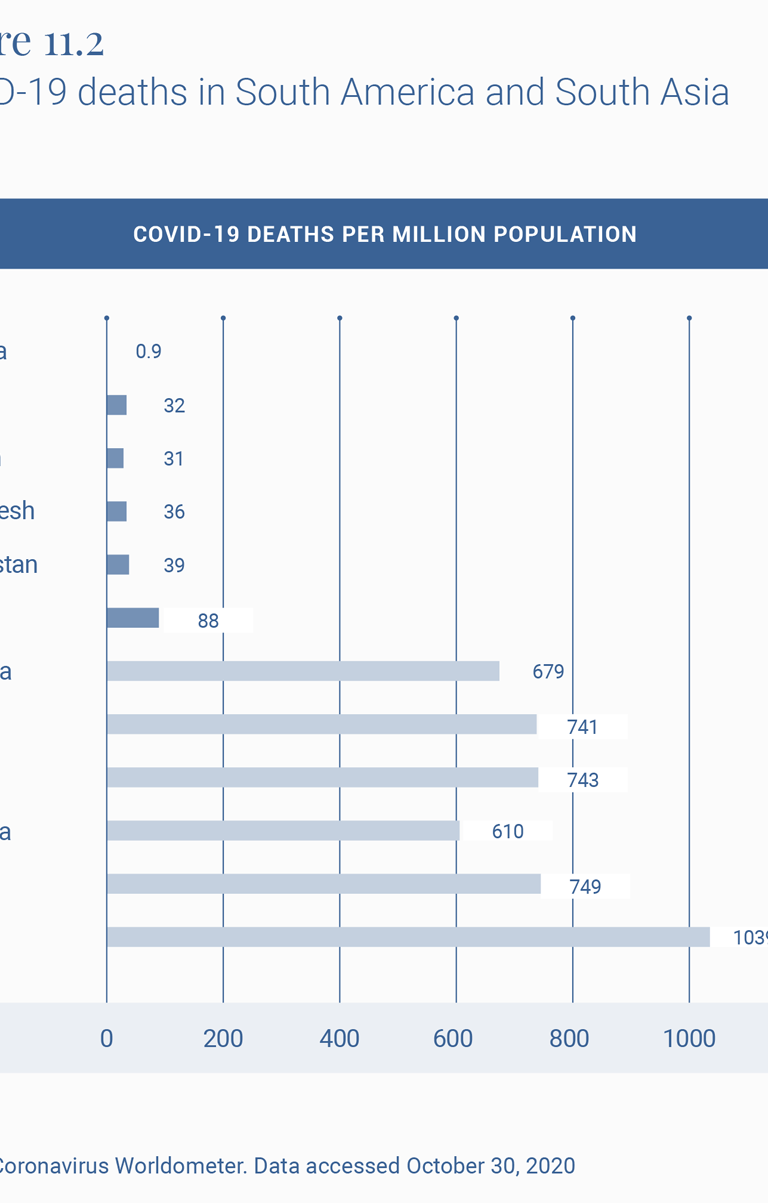

COVID-19-related mortality statistics, and, in particular, the Crude Mortality Rate (CMR), however imperfect, are the most telling indicator of the comparative scale of the pandemic in different countries. At first glance, from the end of October 2020, Peru, with 1039 COVID-19 deaths per million population looks bad by any standard and much worse than India with 88. Peru’s CMR is currently among the highest reported globally.

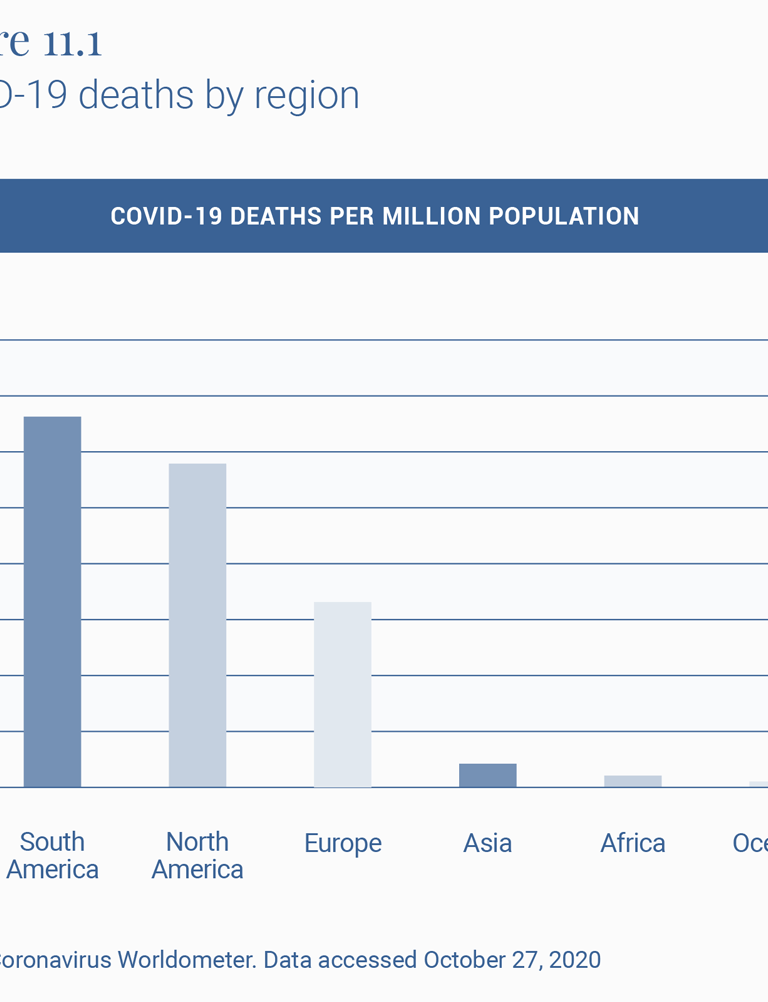

However, both Peru and India need to be placed in regional perspective. For reasons that are likely to do with the history of past diseases, there are striking regional differences in the lethality of the virus (Figure 11.1). South America is worse hit than any other world region, and Asia and Africa seem to have got it relatively lightly, in contrast to Europe and America. The stark regional difference cries out for more epidemiological analysis. But even as we await that, these are differences that cannot be ignored.

To understand the effect of policy interventions, it is therefore important to look at how these countries fare within their own regions, which have had similar histories of illnesses and viruses (Figure 11.2). Both Peru and India do much worse than the neighbors with whom they largely share their social, economic, ecological and demographic features. Peru’s COVID-19 mortality rate per million population, or CMR, of 1039 is ahead of the second highest, Brazil at 749, and almost twice that of Argentina at 679.

Similarly, India at 88 compares well with Europe and the U.S., as does virtually all of Asia and Africa, but is doing much worse than its neighbors, with the second worst country in the region, Afghanistan, experiencing less than half the death rate of India.

The official Indian statement that up to 78,000 deaths 2 were averted by the lockdown has been criticized 3 for its assumptions. A more reasonable exercise is to estimate the excess deaths experienced by a country that breaks away from the pattern of its regional neighbors. So, for example, if India had experienced Afghanistan’s COVID-19 mortality rate, it would by now have had 54,112 deaths. And if it had the rate reported by Bangladesh, it would have had 49,950 deaths from COVID-19 today. In other words, more than half its current toll of some 122,099 COVID-19 deaths would have been avoided if it had experienced the same virus hit as its neighbors.

What might explain this outlier experience of COVID-19 CMRs and economic downslide in India and Peru? If the regional background conditions are broadly similar, one is left to ask if it is in fact the policy response that differed markedly and might account for these relatively poor outcomes.

Peru and India have performed poorly in terms of GDP growth rate in Q2 2020 among the countries displayed in Table 2, and given that both these countries are often treated as case studies of strong governance, this draws attention to the fact that there may be a dissonance between strong governance and good governance.

The turnaround for India has been especially surprising, given that until a few years ago it was among the three fastest growing economies in the world. The slowdown began in 2016, though the sharp downturn, sharper than virtually all other countries, occurred after the lockdown.

On the COVID-19 policy front, both India and Peru have become known for what the Oxford University’s COVID Policy Tracker 4 calls the “stringency” of the government’s response to the epidemic. At 8 pm on March 24, 2020, the Indian government announced, with four hours’ notice, a complete nationwide shutdown. Virtually all movement outside the perimeter of one’s home was officially sought to be brought to a standstill. Naturally, as described in several papers, such as that of Ray and Subramanian, 5 this meant that most economic life also came to a sudden standstill, which in turn meant that hundreds of millions of workers in the informal, as well as more marginally formal sectors, lost their livelihoods.

In addition, tens of millions of these workers, being migrant workers in places far-flung from their original homes, also lost their temporary homes and their savings with these lost livelihoods, so that the only safe space that beckoned them was their place of origin in small towns and villages often hundreds of miles away from their places of work.

After a few weeks of precarious living in their migrant destinations, they set off, on foot since trains and buses had been stopped, for these towns and villages, creating a “lockdown and scatter” that spread the virus from the city to the town and the town to the village. Indeed, “lockdown” is a bit of a misnomer for what happened in India, since over 20 million people did exactly the opposite of what one does in a lockdown. Thus India had a strange combination of lockdown some and scatter the rest, like in no other country. They spilled out and scattered in ways they would otherwise not do. It is not surprising that the infection, which was marginally present in rural areas (23 percent in April), now makes up some 54 percent of all cases in India. 6

In Peru too, the lockdown was sudden, nationwide, long drawn out and stringent. 7 Jobs were lost, financial aid was difficult to disburse, migrant workers were forced to return home, and the virus has now spread to all parts of the country with death rates from it surpassing almost every other part of the world.

As an aside, to think about ways of implementing lockdowns that are less stringent and geographically as well as functionally less total, an example from yet another continent is instructive. Ethiopia, with a COVID-19 death rate of 13 per million population seems to have bettered the already relatively low African rate of 31 in Table 1. 8

We hope that human beings will emerge from this crisis more aware of the problems of sustainability.

The way forward

We next move from the immediate crisis to the medium term. Where is the world headed and how should we deal with the new world? Arguably, that two sectors that will emerge larger and stronger in the post-pandemic world are: digital technology and outsourcing, and healthcare and pharmaceuticals.

The last 9 months of the pandemic have been a huge training ground for people in the use of digital technology—Zoom, WebEx, digital finance, and many others. This learning-by-doing exercise is likely to give a big boost to outsourcing, which has the potential to help countries like India, the Philippines, and South Africa.

Globalization may see a short-run retreat but, we believe, it will come back with a vengeance. Nations that build walls to keep out goods, people and talent will get out-competed by other nations in the product market. This realization will make most countries reverse their knee-jerk anti-globalization; and the ones that do not will cease to be important global players. Either way, globalization will be back on track and with a much greater amount of outsourcing.

To return, more critically this time, to our earlier aside on Ethiopia, its historical and contemporary record on tampering with internet connectivity 9 in an attempt to muzzle inter-ethnic tensions and political dissent will not serve it well in such a post-pandemic scenario. This is a useful reminder for all emerging market economies.

We hope that human beings will emerge from this crisis more aware of the problems of sustainability. This could divert some demand from luxury goods to better health, and what is best described as “creative consumption”: art, music, and culture. 10 The former will mean much larger healthcare and pharmaceutical sectors.

But to take advantage of these new opportunities, nations will need to navigate the current predicament so that they have a viable economy once the pandemic passes. Thus it is important to be able to control the pandemic while keeping the economy open. There is some emerging literature 11 on this, but much more is needed. This is a governance challenge of a kind rarely faced, because the pandemic has disrupted normal markets and there is need, at least in the short run, for governments to step in to fill the caveat.

Emerging economies will have to devise novel governance strategies for doing this double duty of tamping down on new infections without strident controls on economic behavior and without blindly imitating Europe and America.

Here is an example. One interesting opportunity amidst this chaos is to tap into the “resource” of those who have already had COVID-19 and are immune, even if only in the short-term—we still have no definitive evidence on the length of acquired immunity. These people can be offered a high salary to work in sectors that require physical interaction with others. This will help keep supply chains unbroken. Normally, the market would have on its own caused such a salary increase but in this case, the main benefit of marshaling this labor force is on the aggregate economy and GDP and therefore is a classic case of positive externality, which the free market does not adequately reward. It is more a challenge of governance. As with most economic policy, this will need careful research and design before being implemented. We have to be aware that a policy like this will come with its risk of bribery and corruption. There is also the moral hazard challenge of poor people choosing to get COVID-19 in order to qualify for these special jobs. Safeguards will be needed against these risks. But we believe that any government that succeeds in implementing an intelligently-designed intervention to draw on this huge, under-utilized resource can have a big, positive impact on the economy 12 .

This is just one idea. We must innovate in different ways to survive the crisis and then have the ability to navigate the new world that will emerge, hopefully in the not too distant future.

Related Content

Emiliana Vegas, Rebecca Winthrop

Homi Kharas, John W. McArthur

Anthony F. Pipa, Max Bouchet

Note: We are grateful for financial support from Cornell University’s Hatfield Fund for the research associated with this paper. We also wish to express our gratitude to Homi Kharas for many suggestions and David Batcheck for generous editorial help.

- “GDP Annual Growth Rate – Forecast 2020-2022,” Trading Economics, https://tradingeconomics.com/forecast/gdp-annual-growth-rate.

- “Government Cites Various Statistical Models, Says Averted Between 1.4 Million-2.9 Million Cases Due To Lockdown,” Business World, May 23, 2020, www.businessworld.in/article/Government-Cites-Various-Statistical-Models-Says-Averted-Between-1-4-million-2-9-million-Cases-Due-To-Lockdown/23-05-2020-193002/.

- Suvrat Raju, “Did the Indian lockdown avert deaths?” medRxiv , July 5, 2020, https://europepmc.org/article/ppr/ppr183813#A1.

- “COVID Policy Tracker,” Oxford University, https://github.com/OxCGRT/covid-policy-tracker t.

- Debraj Ray and S. Subramanian, “India’s Lockdown: An Interim Report,” NBER Working Paper, May 2020, https://www.nber.org/papers/w27282.

- Gopika Gopakumar and Shayan Ghosh, “Rural recovery could slow down as cases rise, says Ghosh,” Mint, August 19, 2020, https://www.livemint.com/news/india/rural-recovery-could-slow-down-as-cases-rise-says-ghosh-11597801644015.html.

- Pierina Pighi Bel and Jake Horton, “Coronavirus: What’s happening in Peru?,” BBC, July 9, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-53150808.

- “No lockdown, few ventilators, but Ethiopia is beating Covid-19,” Financial Times, May 27, 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/7c6327ca-a00b-11ea-b65d-489c67b0d85d.

- Cara Anna, “Ethiopia enters 3rd week of internet shutdown after unrest,” Washington Post, July 14, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/africa/ethiopia-enters-3rd-week-of-internet-shutdown-after-unrest/2020/07/14/4699c400-c5d6-11ea-a825-8722004e4150_story.html.

- Patrick Kabanda, The Creative Wealth of Nations: Can the Arts Advance Development? (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018).

- Guanlin Li et al, “Disease-dependent interaction policies to support health and economic outcomes during the COVID-19 epidemic,” medRxiv, August 2020, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.08.24.20180752v3.

- For helpful discussion concerning this idea, we are grateful to Turab Hussain, Daksh Walia and Mehr-un-Nisa, during a seminar of South Asian Economics Students’ Meet (SAESM).

Global Economy and Development

Mark Schoeman

May 16, 2024

Ben S. Bernanke, Olivier Blanchard

Joseph Asunka, Landry Signé

May 15, 2024

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Goats and Soda

- Infectious Disease

- Development

- Women & Girls

- Coronavirus FAQ

The Coronavirus Crisis

6 solutions to beat covid-19 in countries where the usual advice just won't work.

Malaka Gharib

The fight against coronavirus will not be won until every country in the world can control the disease. But not every country has the same ability to protect people.

For low-income countries that struggle with weak health systems, large populations of impoverished people and crowded megacities, "there needs to be a very major adaptation" to the established measures we've been using to fight COVID-19, says Dr. Wafaa El-Sadr , an epidemiologist and director of ICAP, a global health organization at Columbia University.

The COVID-19 playbook that wealthy nations in Europe, Asia and North America have come to know — stay home as much as possible, keep a six foot distance from others, wash hands often — will be nearly impossible to follow in much of the developing world.

"I think they're trying, but it's not easy," El-Sadr says. "Ministries of health are working, partnering with international organizations to try to innovate — and hopefully, if the innovation works, it can be scaled up."

Here are some of the solutions now being tried.

Fly in tons of medical gear

Problem: Countries in the developing world face massive shortages of medical gear like personal protective equipment, says Avril Benoit, executive director of Doctors Without Borders. And the cutback in commercial flights has made it difficult to bring in equipment.

Solution: The U.N. has launched what it's calling "solidarity flights" – hiring charter planes to airlift millions of face masks, face shields, goggles, gloves, gowns and other supplies. On April 14 , the U.N. dispatched an Ethiopian Airlines charter flight from Addis Ababa full of COVID-19 gear to transport to countries in need.

"This is by far the largest single shipment of supplies since the start of the pandemic, and we will ensure that people living in countries with some of the weakest health systems are able to get tested and treated," said Dr. Ahmed Al-Mandhari, WHO regional director for the Eastern Mediterranean in a statement .

Assessment: "In the short run, a program like this is fine so long as we're dealing with an acute event," says El-Sadr. "Without [supplies like] PPE, you're at risk of losing your scarce and precious health workforce — and you want to protect them at any cost."

But hiring chartered flights to deliver any kind of aid – instead of commercial flights – is expensive, says Manuel Fontaine, director of emergency programs at UNICEF. The U.N. is calling on donors to provide $350 million to continue this program; so far, it has received $84 million.

Create safe havens for the sick and elderly

Problem: How do you protect the most vulnerable individuals in crowded cities and refugee camps? And how do you keep infected individuals from spreading the disease?

Solution: Health authorities are trying out a somewhat controversial strategy: separating the sick and those at high risk, moving them from the homes where they might live alone or with an extended family into vacant homes or taking over facilities previously used for other purposes, such as learning centers. The people being targeted include the elderly and those with preexisting health conditions that make them susceptible to COVID-19 — as well as the homeless.

The strategy has been cited by several health researchers as a practical way to control the spread of disease in densely packed communities. Francesco Checchi of the London School of Tropical Health and Medicine wrote a paper on the subject , and Dr. Paul Spiegel of Johns Hopkins University, in another paper , recommended this as a potential solution in refugee settings.

Assessment: In his paper, Spiegel warns that the strategy of isolating these groups are "novel and untested." And thus far, in parts of the developing world where the strategy has been rolled out, it has had mixed results.

Shah Dedar, an aid worker with the humanitarian group HelpAge, says that religious and community leaders among the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh don't like the idea of taking the sick or the elderly from the families who might care for them. But "elderly men and women with chronic diseases [who lived alone] were very much keen to the idea and appreciated the initiative," says Dedar.

While HelpAge was able convince local Rohingya leaders to give it a try, Spiegel of Johns Hopkins University says that this may not always be possible. In the case of a severe outbreak, aid workers may have to forcibly separate populations, whether the community approves or not. And he warns that this shielding measure is no guarantee it will keep the virus at bay — it could spread within these facilities, as has happened at some nursing homes in the U.S.