- Contact AAPS

- Get the Newsletter

How to Write a Really Great Presentation Abstract

Whether this is your first abstract submission or you just need a refresher on best practices when writing a conference abstract, these tips are for you..

An abstract for a presentation should include most the following sections. Sometimes they will only be a sentence each since abstracts are typically short (250 words):

- What (the focus): Clearly explain your idea or question your work addresses (i.e. how to recruit participants in a retirement community, a new perspective on the concept of “participant” in citizen science, a strategy for taking results to local government agencies).

- Why (the purpose): Explain why your focus is important (i.e. older people in retirement communities are often left out of citizen science; participants in citizen science are often marginalized as “just” data collectors; taking data to local governments is rarely successful in changing policy, etc.)

- How (the methods): Describe how you collected information/data to answer your question. Your methods might be quantitative (producing a number-based result, such as a count of participants before and after your intervention), or qualitative (producing or documenting information that is not metric-based such as surveys or interviews to document opinions, or motivations behind a person’s action) or both.

- Results: Share your results — the information you collected. What does the data say? (e.g. Retirement community members respond best to in-person workshops; participants described their participation in the following ways, 6 out of 10 attempts to influence a local government resulted in policy changes ).

- Conclusion : State your conclusion(s) by relating your data to your original question. Discuss the connections between your results and the problem (retirement communities are a wonderful resource for new participants; when we broaden the definition of “participant” the way participants describe their relationship to science changes; involvement of a credentialed scientist increases the likelihood of success of evidence being taken seriously by local governments.). If your project is still ‘in progress’ and you don’t yet have solid conclusions, use this space to discuss what you know at the moment (i.e. lessons learned so far, emerging trends, etc).

Here is a sample abstract submitted to a previous conference as an example:

Giving participants feedback about the data they help to collect can be a critical (and sometimes ignored) part of a healthy citizen science cycle. One study on participant motivations in citizen science projects noted “When scientists were not cognizant of providing periodic feedback to their volunteers, volunteers felt peripheral, became demotivated, and tended to forgo future work on those projects” (Rotman et al, 2012). In that same study, the authors indicated that scientists tended to overlook the importance of feedback to volunteers, missing their critical interest in the science and the value to participants when their contributions were recognized. Prioritizing feedback for volunteers adds value to a project, but can be daunting for project staff. This speed talk will cover 3 different kinds of visual feedback that can be utilized to keep participants in-the-loop. We’ll cover strengths and weaknesses of each visualization and point people to tools available on the Web to help create powerful visualizations. Rotman, D., Preece, J., Hammock, J., Procita, K., Hansen, D., Parr, C., et al. (2012). Dynamic changes in motivation in collaborative citizen-science projects. the ACM 2012 conference (pp. 217–226). New York, New York, USA: ACM. doi:10.1145/2145204.2145238

📊 Data Ethics – Refers to trustworthy data practices for citizen science.

Get involved » Join the Data Ethics Topic Room on CSA Connect!

📰 Publication Ethics – Refers to the best practice in the ethics of scholarly publishing.

Get involved » Join the Publication Ethics Topic Room on CSA Connect!

⚖️ Social Justice Ethics – Refers to fair and just relations between the individual and society as measured by the distribution of wealth, opportunities for personal activity, and social privileges. Social justice also encompasses inclusiveness and diversity.

Get involved » Join the Social Justice Topic Room on CSA Connect!

👤 Human Subject Ethics – Refers to rules of conduct in any research involving humans including biomedical research, social studies. Note that this goes beyond human subject ethics regulations as much of what goes on isn’t covered.

Get involved » Join the Human Subject Ethics Topic Room on CSA Connect!

🍃 Biodiversity & Environmental Ethics – Refers to the improvement of the dynamics between humans and the myriad of species that combine to create the biosphere, which will ultimately benefit both humans and non-humans alike [UNESCO 2011 white paper on Ethics and Biodiversity ]. This is a kind of ethics that is advancing rapidly in light of the current global crisis as many stakeholders know how critical biodiversity is to the human species (e.g., public health, women’s rights, social and environmental justice).

⚠ UNESCO also affirms that respect for biological diversity implies respect for societal and cultural diversity, as both elements are intimately interconnected and fundamental to global well-being and peace. ( Source ).

Get involved » Join the Biodiversity & Environmental Ethics Topic Room on CSA Connect!

🤝 Community Partnership Ethics – Refers to rules of engagement and respect of community members directly or directly involved or affected by any research study/project.

Get involved » Join the Community Partnership Ethics Topic Room on CSA Connect!

Academic & Employability Skills

Subscribe to academic & employability skills.

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Join 412 other subscribers.

Email Address

Writing an abstract - a six point checklist (with samples)

Posted in: abstract , dissertations

The abstract is a vital part of any research paper. It is the shop front for your work, and the first stop for your reader. It should provide a clear and succinct summary of your study, and encourage your readers to read more. An effective abstract, therefore should answer the following questions:

- Why did you do this study or project?

- What did you do and how?

- What did you find?

- What do your findings mean?

So here's our run down of the key elements of a well-written abstract.

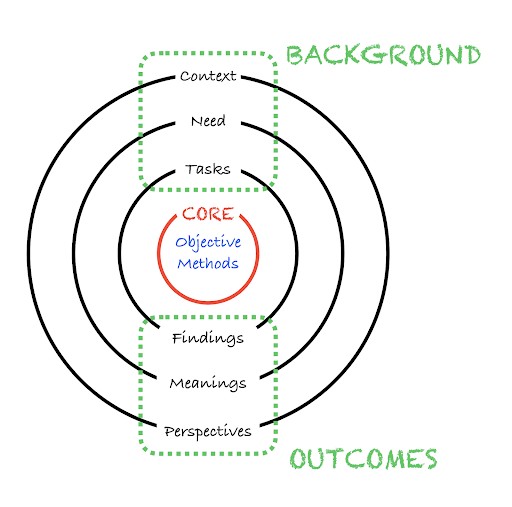

- Size - A succinct and well written abstract should be between approximately 100- 250 words.

- Background - An effective abstract usually includes some scene-setting information which might include what is already known about the subject, related to the paper in question (a few short sentences).

- Purpose - The abstract should also set out the purpose of your research, in other words, what is not known about the subject and hence what the study intended to examine (or what the paper seeks to present).

- Methods - The methods section should contain enough information to enable the reader to understand what was done, and how. It should include brief details of the research design, sample size, duration of study, and so on.

- Results - The results section is the most important part of the abstract. This is because readers who skim an abstract do so to learn about the findings of the study. The results section should therefore contain as much detail about the findings as the journal word count permits.

- Conclusion - This section should contain the most important take-home message of the study, expressed in a few precisely worded sentences. Usually, the finding highlighted here relates to the primary outcomes of the study. However, other important or unexpected findings should also be mentioned. It is also customary, but not essential, to express an opinion about the theoretical or practical implications of the findings, or the importance of their findings for the field. Thus, the conclusions may contain three elements:

- The primary take-home message.

- Any additional findings of importance.

- Implications for future studies.

Example Abstract 2: Engineering Development and validation of a three-dimensional finite element model of the pelvic bone.

Abstract from: Dalstra, M., Huiskes, R. and Van Erning, L., 1995. Development and validation of a three-dimensional finite element model of the pelvic bone. Journal of biomechanical engineering, 117(3), pp.272-278.

And finally... A word on abstract types and styles

Abstract types can differ according to subject discipline. You need to determine therefore which type of abstract you should include with your paper. Here are two of the most common types with examples.

Informative Abstract

The majority of abstracts are informative. While they still do not critique or evaluate a work, they do more than describe it. A good informative abstract acts as a surrogate for the work itself. That is, the researcher presents and explains all the main arguments and the important results and evidence in the paper. An informative abstract includes the information that can be found in a descriptive abstract [purpose, methods, scope] but it also includes the results and conclusions of the research and the recommendations of the author. The length varies according to discipline, but an informative abstract is usually no more than 300 words in length.

Descriptive Abstract A descriptive abstract indicates the type of information found in the work. It makes no judgements about the work, nor does it provide results or conclusions of the research. It does incorporate key words found in the text and may include the purpose, methods, and scope of the research. Essentially, the descriptive abstract only describes the work being summarised. Some researchers consider it an outline of the work, rather than a summary. Descriptive abstracts are usually very short, 100 words or less.

Adapted from Andrade C. How to write a good abstract for a scientific paper or conference presentation. Indian J Psychiatry. 2011 Apr;53(2):172-5. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.82558. PMID: 21772657; PMCID: PMC3136027 .

Share this:

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Click here to cancel reply.

- Email * (we won't publish this)

Write a response

Navigating the dissertation process: my tips for final years

Imagine for a moment... After months of hard work and research on a topic you're passionate about, the time has finally come to click the 'Submit' button on your dissertation. You've just completed your longest project to date as part...

8 ways to beat procrastination

Whether you’re writing an assignment or revising for exams, getting started can be hard. Fortunately, there’s lots you can do to turn procrastination into action.

My takeaways on how to write a scientific report

If you’re in your dissertation writing stage or your course includes writing a lot of scientific reports, but you don’t quite know where and how to start, the Skills Centre can help you get started. I recently attended their ‘How...

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write an Abstract

Expedite peer review, increase search-ability, and set the tone for your study

The abstract is your chance to let your readers know what they can expect from your article. Learn how to write a clear, and concise abstract that will keep your audience reading.

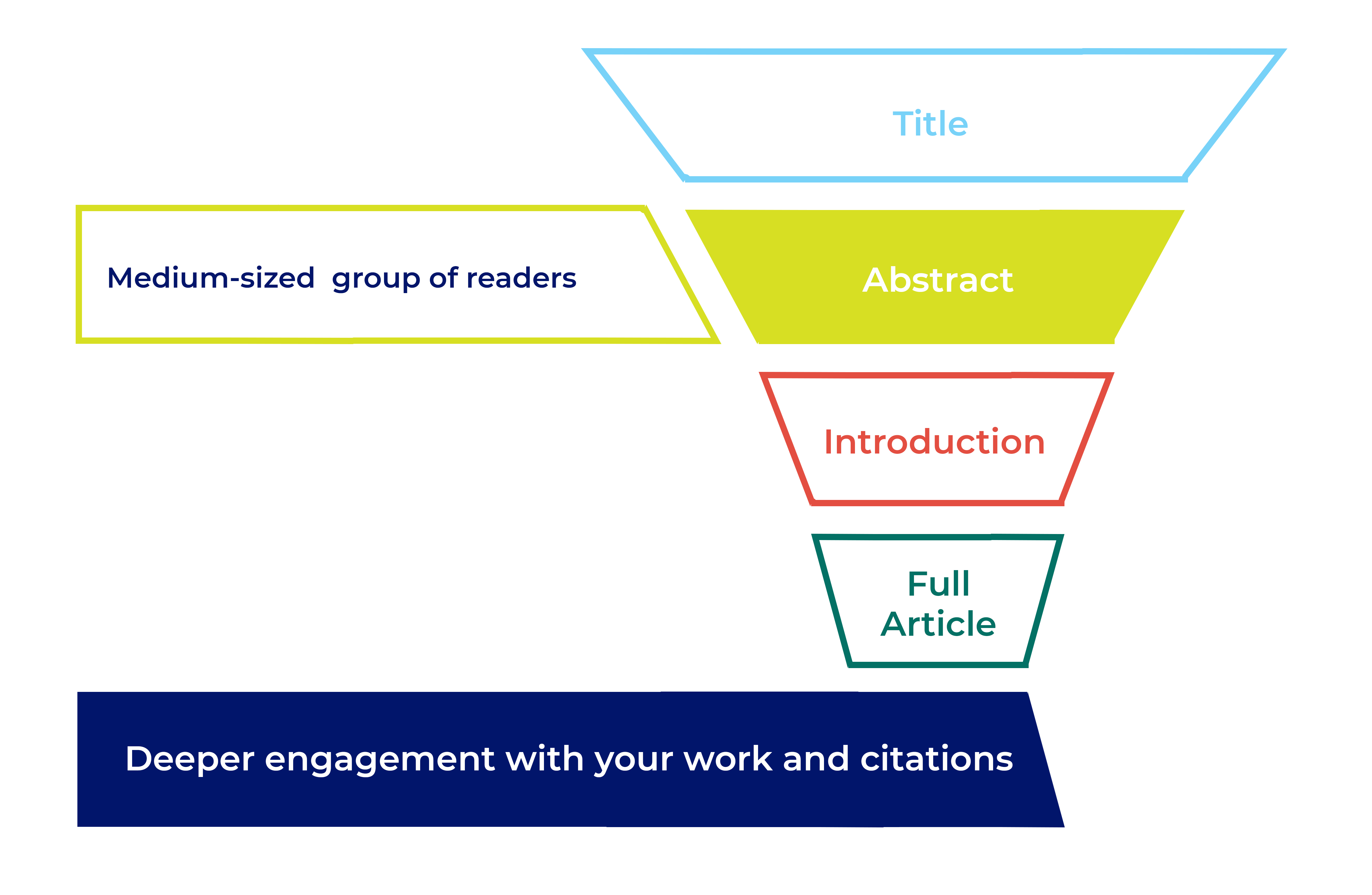

How your abstract impacts editorial evaluation and future readership

After the title , the abstract is the second-most-read part of your article. A good abstract can help to expedite peer review and, if your article is accepted for publication, it’s an important tool for readers to find and evaluate your work. Editors use your abstract when they first assess your article. Prospective reviewers see it when they decide whether to accept an invitation to review. Once published, the abstract gets indexed in PubMed and Google Scholar , as well as library systems and other popular databases. Like the title, your abstract influences keyword search results. Readers will use it to decide whether to read the rest of your article. Other researchers will use it to evaluate your work for inclusion in systematic reviews and meta-analysis. It should be a concise standalone piece that accurately represents your research.

What to include in an abstract

The main challenge you’ll face when writing your abstract is keeping it concise AND fitting in all the information you need. Depending on your subject area the journal may require a structured abstract following specific headings. A structured abstract helps your readers understand your study more easily. If your journal doesn’t require a structured abstract it’s still a good idea to follow a similar format, just present the abstract as one paragraph without headings.

Background or Introduction – What is currently known? Start with a brief, 2 or 3 sentence, introduction to the research area.

Objectives or Aims – What is the study and why did you do it? Clearly state the research question you’re trying to answer.

Methods – What did you do? Explain what you did and how you did it. Include important information about your methods, but avoid the low-level specifics. Some disciplines have specific requirements for abstract methods.

- CONSORT for randomized trials.

- STROBE for observational studies

- PRISMA for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Results – What did you find? Briefly give the key findings of your study. Include key numeric data (including confidence intervals or p values), where possible.

Conclusions – What did you conclude? Tell the reader why your findings matter, and what this could mean for the ‘bigger picture’ of this area of research.

Writing tips

The main challenge you may find when writing your abstract is keeping it concise AND convering all the information you need to.

- Keep it concise and to the point. Most journals have a maximum word count, so check guidelines before you write the abstract to save time editing it later.

- Write for your audience. Are they specialists in your specific field? Are they cross-disciplinary? Are they non-specialists? If you’re writing for a general audience, or your research could be of interest to the public keep your language as straightforward as possible. If you’re writing in English, do remember that not all of your readers will necessarily be native English speakers.

- Focus on key results, conclusions and take home messages.

- Write your paper first, then create the abstract as a summary.

- Check the journal requirements before you write your abstract, eg. required subheadings.

- Include keywords or phrases to help readers search for your work in indexing databases like PubMed or Google Scholar.

- Double and triple check your abstract for spelling and grammar errors. These kind of errors can give potential reviewers the impression that your research isn’t sound, and can make it easier to find reviewers who accept the invitation to review your manuscript. Your abstract should be a taste of what is to come in the rest of your article.

Don’t

- Sensationalize your research.

- Speculate about where this research might lead in the future.

- Use abbreviations or acronyms (unless absolutely necessary or unless they’re widely known, eg. DNA).

- Repeat yourself unnecessarily, eg. “Methods: We used X technique. Results: Using X technique, we found…”

- Contradict anything in the rest of your manuscript.

- Include content that isn’t also covered in the main manuscript.

- Include citations or references.

Tip: How to edit your work

Editing is challenging, especially if you are acting as both a writer and an editor. Read our guidelines for advice on how to refine your work, including useful tips for setting your intentions, re-review, and consultation with colleagues.

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write Your Methods

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

Five Steps to a Brilliant Abstract

by Dr. Jo Koster, Winthrop University

Humanities scholars and students aren’t usually taught to write abstracts like our friends in the natural and social sciences are. That’s because in the humanities, full pieces of discourse are preferred to short, condensed summaries. But in many cases you will NEED to write an abstract for your work—and a lot of what your colleagues in other disciplines know can help you.

Let’s start with the basic questions.

What is a descriptive abstract?

A descriptive abstract is the summary of work you have already completed or work you are proposing. It is not the same thing as the introduction to your work. The abstract should give readers a short, concise snapshot of the work as a whole—not just how it starts. Remember that the readers of your abstract will sometimes not read the paper as a whole, so in this short document you need to give them an overall picture of your work. If you are writing an abstract as a proposal for your research—in other words, as a request for permission to write a paper—the abstract serves to predict the kind of paper you hope to write.

What’s different about a conference paper (or informative) abstract?

A conference abstract is one you submit to have your paper considered for presentation at a professional conference (CURAH maintains a growing list of these opportunities ). The conference organizers will specify the length — rarely be more than 500 words (just short of two double-spaced pages). In an ideal world, you write your abstract after the actual paper is completed, but in some cases you may write an abstract for a paper you haven’t yet written—especially if the conference is some time away. Because the conference review committee will usually read the abstract and not your actual paper, you need to think of it as an independent document, aimed at that specific committee and connecting solidly with the theme of the conference. You may want to pick up phrasing from the conference title or call for papers in the abstract to reinforce this connection. Examine the call for papers carefully; it will specify the length of the abstract, special formatting requirements, whether the abstract will be published in the conference bulletin or proceedings, etc. Abstracts that do not meet the specified format are usually rejected early in the proceedings, so pay attention to each conference’s rules!

How wedded are you to the abstract you submit?

An abstract is a promissory note. That is, you are promising that you can and will produce the goods in the paper. Particularly in the case of a conference abstract, the organizers will make up a session based on the contents of the abstract. If you propose a paper that says you will use Foucault to comment on post-colonialism in Heat and Dust” and then show up with a paper on “Metaphors for Spring in A Bend in the River,” your paper may not fit the session where it was slotted, and you’ll look silly—and those organizers may not ask you back. While some divergence from the promised topic is acceptable (and probably inevitable if you haven’t written the paper when you submit the abstract), you need to produce a paper that’s within shouting distance of your original topic for the sake of keeping your promise.

The Five Step Process

Descriptive abstracts are usually only 100-250 words, so they must be pared down to the essentials. Typically, a descriptive abstract answers these questions:

Why did you choose this study or project? What did/will you do and how? What did you/do you hope to find? (For a completed work) What do your findings mean?

Step 1: A catchy title

Which paper would you rather go hear at a conference? ‘Issues of Heteronormativity and Gender Performance In Twain’s Novels” or “Come Back to the Raft, Huck Honey”?

Your title should be informative and focused, indicating the problem and your general approach. It’s very fashionable in the humanities to have titles featuring a catchy phrase, a colon, and then an explanation of the title. While snappy titles may help your abstract be noticed, it’s really what comes after the colon that sells the abstract, so pay attention to it. “All the World’s a Ship: Race and Ethnicity in Moby Dick” catches the eye, but “Melville’s Deconstruction of Ethnicity in the ‘Midnight, Forecastle’ Episode of Moby Dick” tells readers much more specifically what you’re promising to deliver.

Step 2: A snappy context sentence (or sentences)

The abstract should begin with a clear sense of the research question you have framed. Often writers set this up as a problem: “Although some recent scholars claim to have identified Shakespeare’s lost play Cardenio, that attribution is still not accepted.

Step 3: Introduce your argument (don’t just copy your thesis statement).

If you began with a problem, you can pose your argument as the solution: “In this paper I use the records of the Worshipful Company of Stationers, London’s chief publishing organization, to show that the play identified by Charles Hamilton in 1990 is not actually the play Shakespeare’s company mounted in 1613.” It’s perfectly legit to use “I” in sentences referring to your argument.

Step 4: Add some sentences describing how you make your argument.

It always helps when you identify the theoretical or methodological school that you are using to approach your question or position yourself within an ongoing debate. This helps readers situate your ideas in the larger conversations of your discipline. For instance, “The debate among Folsom, McGann, and Stallybrass over the notion of database as a genre (PMLA 122.5, Fall 2007) suggests that….” or “Using the definition of dataclouds proposed by Johnson-Eilola (2005), I will argue that…”

Finally, briefly state your conclusion.

“ Through analyzing Dickinson’s use of metaphor, I demonstrate that she systematically transformed Watt’s hymnal tropes as a way of asserting her own doctrinal truths. This transformation…”

Not everyone agrees how much jargon should be included in an abstract. My best advice is to add any technical terms you need, but don’t put in jargon for jargon’s sake or just to make it look like you are an expert (this especially extends to (post)modernizing your words or other typographical excrescences).

Special for conference papers:

To the basic requirements of the descriptive abstract, a conference paper abstract should also include a few sentences about how the proposed paper fits in the theme of the conference. For instance, a call for papers for a session on “Science and Literature in the 19th Century” at a conference entitled “(Dis)Junctions” requested “critical works on the interaction between scientific writing and literature in the 19th century. How did scientific discoveries, theories and assumptions (for example, in medicine and psychology, but not limited to these) influence contemporaneous fiction?” If you were submitting a paper to this session, you would want to have a sentence or two about the theories you were discussing and name the particular works where you would identify their influence. If you can work the words “join” or “junction” (or “disjunction”) into your title or abstract, you’ll increase your chance of having the paper accepted, since you’re showing clearly how the paper fits the theme of the session.

Step 5: Show the conference organizers or editors that you’re a pro.

Tell them your essay is a finished work (even if it’s only complete in your head!). It’s also considered good in a conference abstract to conclude with a sentence about your presentation, since the great horror of session chairs is the paper that runs far too long (or embarrassingly too short). Organizers also need to know if you need any special technology to present the paper. So a a much-appreciated professional touch is concluding passage such as, “My paper is complete and can be presented in 20 minutes. I will bring bring video clips on a portable drive but will need a computer, projector, and Internet access to show all my materials.”

Be professional!

Double-check your abstract to make sure it meets the length requirements. Make sure it’s edited and documented. And above all, make sure it’s submitted on time.

Here is a video version of this page, taking you from the call for papers to the finished abstract.

Check out these other guides from CURAH:

- How to write a proposal

- How to make a poster

- A list of regional and national conferences where you can present your work

Acknowledgements:

Illustrated by Ian MacInnes Thanks to Dr. Leslie Bickford for her sample abstract

I consulted and borrowed material from the following websites in preparing these suggestions:

www.unc.edu/depts/wcweb/handouts/abstracts.html www.linguistics.ucsb.edu/faculty/bucholtz/sociocultural/abstracttips.html www.academic-conferences.org/abstract-guidelines.htm ceca.icom.museum/ dbase upl/writinganabstract.pdf ling.wisc.edu/macaulay/800.abstracts.html writingcenter.unlv.edu/writing/abstract.html www.lightbluetouchpaper.org/2007/03/14/how-not-to-write-an-abstract/ webapp.comcol.umass.edu/msc/absGuidelines.aspx www.oberlin.edu/history/Honors/prospectus.html www.english.eku.edu/ma/scholarlythesis.php

The Arts and Humanities Division of the Council on Undergraduate Research

Important Tips for Writing an Effective Conference Abstract

Academic conferences are an important part of graduate work. They offer researchers an opportunity to present their work and network with other researchers. So, how does a researcher get invited to present their work at an academic conference ? The first step is to write and submit an abstract of your research paper .

The purpose of a conference abstract is to summarize the main points of your paper that you will present in the academic conference. In it, you need to convince conference organizers that you have something important and valuable to add to the conference. Therefore, it needs to be focused and clear in explaining your topic and the main points of research that you will share with the audience.

The Main Points of a Conference Abstract

There are some general formulas for creating a conference abstract .

Formula : topic + title + motivation + problem statement + approach + results + conclusions = conference abstract

Here are the main points that you need to include.

The title needs to grab people’s attention. Most importantly, it needs to state your topic clearly and develop interest. This will give organizers an idea of how your paper fits the focus of the conference.

Problem Statement

You should state the specific problem that you are trying to solve.

The abstract needs to illustrate the purpose of your work. This is the point that will help the conference organizer determine whether or not to include your paper in a conference session.

You have a problem before you: What approach did you take towards solving the problem? You can include how you organized this study and the research that you used.

Important Things to Know When Developing Your Abstract

Do your research on the conference.

You need to know the deadline for abstract submissions. And, you should submit your abstract as early as possible.

Do some research on the conference to see what the focus is and how your topic fits. This includes looking at the range of sessions that will be at the conference. This will help you see which specific session would be the best fit for your paper.

Select Your Keywords Carefully

Keywords play a vital role in increasing the discoverability of your article. Use the keywords that most appropriately reflect the content of your article.

Once you are clear on the topic of the conference, you can tailor your abstract to fit specific sessions.

An important part of keeping your focus is knowing the word limit for the abstract. Most word limits are around 250-300 words. So, be concise.

Use Example Abstracts as a Guide

Looking at examples of abstracts is always a big help. Look at general examples of abstracts and examples of abstracts in your field. Take notes to understand the main points that make an abstract effective.

Avoid Fillers and Jargon

As stated earlier, abstracts are supposed to be concise, yet informative. Avoid using words or phrases that do not add any specific value to your research. Keep the sentences short and crisp to convey just as much information as needed.

Edit with a Fresh Mind

After you write your abstract, step away from it. Then, look it over with a fresh mind. This will help you edit it to improve its effectiveness. In addition, you can also take the help of professional editing services that offer quick deliveries.

Remain Focused and Establish Your Ideas

The main point of an abstract is to catch the attention of the conference organizers. So, you need to be focused in developing the importance of your work. You want to establish the importance of your ideas in as little as 250-300 words.

Have you attended a conference as a student? What experiences do you have with conference abstracts? Please share your ideas in the comments. You can also visit our Q&A forum for frequently asked questions related to different aspects of research writing, presenting, and publishing answered by our team that comprises subject-matter experts, eminent researchers, and publication experts.

best article to write a good abstract

Excellent guidelines for writing a good abstract.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

![how to create an abstract for a presentation What is Academic Integrity and How to Uphold it [FREE CHECKLIST]](https://www.enago.com/academy/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/FeatureImages-59-210x136.png)

Ensuring Academic Integrity and Transparency in Academic Research: A comprehensive checklist for researchers

Academic integrity is the foundation upon which the credibility and value of scientific findings are…

- AI in Academia

AI vs. AI: How to detect image manipulation and avoid academic misconduct

The scientific community is facing a new frontier of controversy as artificial intelligence (AI) is…

- Diversity and Inclusion

Need for Diversifying Academic Curricula: Embracing missing voices and marginalized perspectives

In classrooms worldwide, a single narrative often dominates, leaving many students feeling lost. These stories,…

- Career Corner

- Trending Now

Recognizing the signs: A guide to overcoming academic burnout

As the sun set over the campus, casting long shadows through the library windows, Alex…

Reassessing the Lab Environment to Create an Equitable and Inclusive Space

The pursuit of scientific discovery has long been fueled by diverse minds and perspectives. Yet…

7 Steps of Writing an Excellent Academic Book Chapter

When Your Thesis Advisor Asks You to Quit

Virtual Defense: Top 5 Online Thesis Defense Tips

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

How to Write an Abstract (With Examples)

Sarah Oakley

Table of Contents

What is an abstract in a paper, how long should an abstract be, 5 steps for writing an abstract, examples of an abstract, how prowritingaid can help you write an abstract.

If you are writing a scientific research paper or a book proposal, you need to know how to write an abstract, which summarizes the contents of the paper or book.

When researchers are looking for peer-reviewed papers to use in their studies, the first place they will check is the abstract to see if it applies to their work. Therefore, your abstract is one of the most important parts of your entire paper.

In this article, we’ll explain what an abstract is, what it should include, and how to write one.

An abstract is a concise summary of the details within a report. Some abstracts give more details than others, but the main things you’ll be talking about are why you conducted the research, what you did, and what the results show.

When a reader is deciding whether to read your paper completely, they will first look at the abstract. You need to be concise in your abstract and give the reader the most important information so they can determine if they want to read the whole paper.

Remember that an abstract is the last thing you’ll want to write for the research paper because it directly references parts of the report. If you haven’t written the report, you won’t know what to include in your abstract.

If you are writing a paper for a journal or an assignment, the publication or academic institution might have specific formatting rules for how long your abstract should be. However, if they don’t, most abstracts are between 150 and 300 words long.

A short word count means your writing has to be precise and without filler words or phrases. Once you’ve written a first draft, you can always use an editing tool, such as ProWritingAid, to identify areas where you can reduce words and increase readability.

If your abstract is over the word limit, and you’ve edited it but still can’t figure out how to reduce it further, your abstract might include some things that aren’t needed. Here’s a list of three elements you can remove from your abstract:

Discussion : You don’t need to go into detail about the findings of your research because your reader will find your discussion within the paper.

Definition of terms : Your readers are interested the field you are writing about, so they are likely to understand the terms you are using. If not, they can always look them up. Your readers do not expect you to give a definition of terms in your abstract.

References and citations : You can mention there have been studies that support or have inspired your research, but you do not need to give details as the reader will find them in your bibliography.

Good writing = better grades

ProWritingAid will help you improve the style, strength, and clarity of all your assignments.

If you’ve never written an abstract before, and you’re wondering how to write an abstract, we’ve got some steps for you to follow. It’s best to start with planning your abstract, so we’ve outlined the details you need to include in your plan before you write.

Remember to consider your audience when you’re planning and writing your abstract. They are likely to skim read your abstract, so you want to be sure your abstract delivers all the information they’re expecting to see at key points.

1. What Should an Abstract Include?

Abstracts have a lot of information to cover in a short number of words, so it’s important to know what to include. There are three elements that need to be present in your abstract:

Your context is the background for where your research sits within your field of study. You should briefly mention any previous scientific papers or experiments that have led to your hypothesis and how research develops in those studies.

Your hypothesis is your prediction of what your study will show. As you are writing your abstract after you have conducted your research, you should still include your hypothesis in your abstract because it shows the motivation for your paper.

Throughout your abstract, you also need to include keywords and phrases that will help researchers to find your article in the databases they’re searching. Make sure the keywords are specific to your field of study and the subject you’re reporting on, otherwise your article might not reach the relevant audience.

2. Can You Use First Person in an Abstract?

You might think that first person is too informal for a research paper, but it’s not. Historically, writers of academic reports avoided writing in first person to uphold the formality standards of the time. However, first person is more accepted in research papers in modern times.

If you’re still unsure whether to write in first person for your abstract, refer to any style guide rules imposed by the journal you’re writing for or your teachers if you are writing an assignment.

3. Abstract Structure

Some scientific journals have strict rules on how to structure an abstract, so it’s best to check those first. If you don’t have any style rules to follow, try using the IMRaD structure, which stands for Introduction, Methodology, Results, and Discussion.

Following the IMRaD structure, start with an introduction. The amount of background information you should include depends on your specific research area. Adding a broad overview gives you less room to include other details. Remember to include your hypothesis in this section.

The next part of your abstract should cover your methodology. Try to include the following details if they apply to your study:

What type of research was conducted?

How were the test subjects sampled?

What were the sample sizes?

What was done to each group?

How long was the experiment?

How was data recorded and interpreted?

Following the methodology, include a sentence or two about the results, which is where your reader will determine if your research supports or contradicts their own investigations.

The results are also where most people will want to find out what your outcomes were, even if they are just mildly interested in your research area. You should be specific about all the details but as concise as possible.

The last few sentences are your conclusion. It needs to explain how your findings affect the context and whether your hypothesis was correct. Include the primary take-home message, additional findings of importance, and perspective. Also explain whether there is scope for further research into the subject of your report.

Your conclusion should be honest and give the reader the ultimate message that your research shows. Readers trust the conclusion, so make sure you’re not fabricating the results of your research. Some readers won’t read your entire paper, but this section will tell them if it’s worth them referencing it in their own study.

4. How to Start an Abstract

The first line of your abstract should give your reader the context of your report by providing background information. You can use this sentence to imply the motivation for your research.

You don’t need to use a hook phrase or device in your first sentence to grab the reader’s attention. Your reader will look to establish relevance quickly, so readability and clarity are more important than trying to persuade the reader to read on.

5. How to Format an Abstract

Most abstracts use the same formatting rules, which help the reader identify the abstract so they know where to look for it.

Here’s a list of formatting guidelines for writing an abstract:

Stick to one paragraph

Use block formatting with no indentation at the beginning

Put your abstract straight after the title and acknowledgements pages

Use present or past tense, not future tense

There are two primary types of abstract you could write for your paper—descriptive and informative.

An informative abstract is the most common, and they follow the structure mentioned previously. They are longer than descriptive abstracts because they cover more details.

Descriptive abstracts differ from informative abstracts, as they don’t include as much discussion or detail. The word count for a descriptive abstract is between 50 and 150 words.

Here is an example of an informative abstract:

A growing trend exists for authors to employ a more informal writing style that uses “we” in academic writing to acknowledge one’s stance and engagement. However, few studies have compared the ways in which the first-person pronoun “we” is used in the abstracts and conclusions of empirical papers. To address this lacuna in the literature, this study conducted a systematic corpus analysis of the use of “we” in the abstracts and conclusions of 400 articles collected from eight leading electrical and electronic (EE) engineering journals. The abstracts and conclusions were extracted to form two subcorpora, and an integrated framework was applied to analyze and seek to explain how we-clusters and we-collocations were employed. Results revealed whether authors’ use of first-person pronouns partially depends on a journal policy. The trend of using “we” showed that a yearly increase occurred in the frequency of “we” in EE journal papers, as well as the existence of three “we-use” types in the article conclusions and abstracts: exclusive, inclusive, and ambiguous. Other possible “we-use” alternatives such as “I” and other personal pronouns were used very rarely—if at all—in either section. These findings also suggest that the present tense was used more in article abstracts, but the present perfect tense was the most preferred tense in article conclusions. Both research and pedagogical implications are proffered and critically discussed.

Wang, S., Tseng, W.-T., & Johanson, R. (2021). To We or Not to We: Corpus-Based Research on First-Person Pronoun Use in Abstracts and Conclusions. SAGE Open, 11(2).

Here is an example of a descriptive abstract:

From the 1850s to the present, considerable criminological attention has focused on the development of theoretically-significant systems for classifying crime. This article reviews and attempts to evaluate a number of these efforts, and we conclude that further work on this basic task is needed. The latter part of the article explicates a conceptual foundation for a crime pattern classification system, and offers a preliminary taxonomy of crime.

Farr, K. A., & Gibbons, D. C. (1990). Observations on the Development of Crime Categories. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 34(3), 223–237.

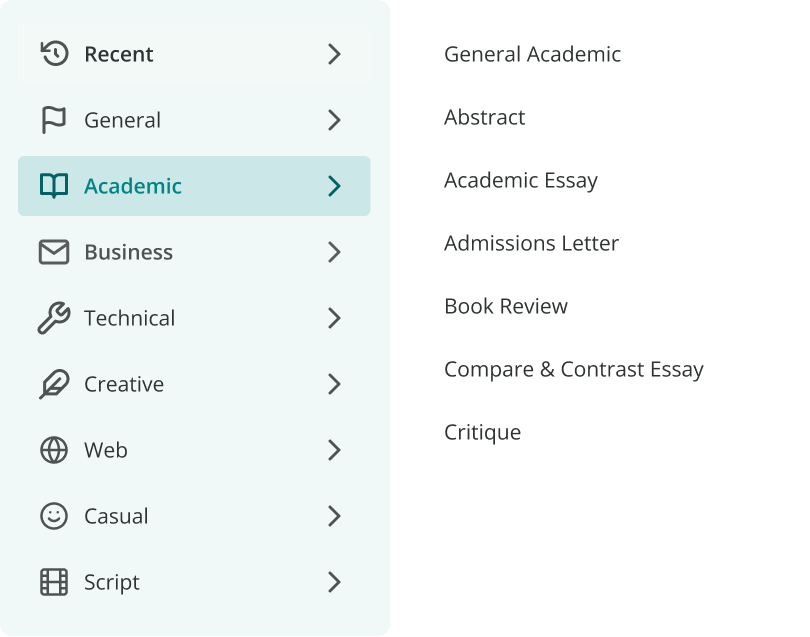

If you want to ensure your abstract is grammatically correct and easy to read, you can use ProWritingAid to edit it. The software integrates with Microsoft Word, Google Docs, and most web browsers, so you can make the most of it wherever you’re writing your paper.

Before you edit with ProWritingAid, make sure the suggestions you are seeing are relevant for your document by changing the document type to “Abstract” within the Academic writing style section.

You can use the Readability report to check your abstract for places to improve the clarity of your writing. Some suggestions might show you where to remove words, which is great if you’re over your word count.

We hope the five steps and examples we’ve provided help you write a great abstract for your research paper.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Science Writing

How to Write an Abstract

Last Updated: May 6, 2021 Approved

This article was co-authored by Megan Morgan, PhD . Megan Morgan is a Graduate Program Academic Advisor in the School of Public & International Affairs at the University of Georgia. She earned her PhD in English from the University of Georgia in 2015. There are 11 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. wikiHow marks an article as reader-approved once it receives enough positive feedback. This article received 60 testimonials and 86% of readers who voted found it helpful, earning it our reader-approved status. This article has been viewed 4,906,682 times.

If you need to write an abstract for an academic or scientific paper, don't panic! Your abstract is simply a short, stand-alone summary of the work or paper that others can use as an overview. [1] X Trustworthy Source University of North Carolina Writing Center UNC's on-campus and online instructional service that provides assistance to students, faculty, and others during the writing process Go to source An abstract describes what you do in your essay, whether it’s a scientific experiment or a literary analysis paper. It should help your reader understand the paper and help people searching for this paper decide whether it suits their purposes prior to reading. To write an abstract, finish your paper first, then type a summary that identifies the purpose, problem, methods, results, and conclusion of your work. After you get the details down, all that's left is to format it correctly. Since an abstract is only a summary of the work you've already done, it's easy to accomplish!

Getting Your Abstract Started

- A thesis and an abstract are entirely different things. The thesis of a paper introduces the main idea or question, while the abstract works to review the entirety of the paper, including the methods and results.

- Even if you think that you know what your paper is going to be about, always save the abstract for last. You will be able to give a much more accurate summary if you do just that - summarize what you've already written.

- Is there a maximum or minimum length?

- Are there style requirements?

- Are you writing for an instructor or a publication?

- Will other academics in your field read this abstract?

- Should it be accessible to a lay reader or somebody from another field?

- Descriptive abstracts explain the purpose, goal, and methods of your research but leave out the results section. These are typically only 100-200 words.

- Informative abstracts are like a condensed version of your paper, giving an overview of everything in your research including the results. These are much longer than descriptive abstracts, and can be anywhere from a single paragraph to a whole page long. [4] X Research source

- The basic information included in both styles of abstract is the same, with the main difference being that the results are only included in an informative abstract, and an informative abstract is much longer than a descriptive one.

- A critical abstract is not often used, but it may be required in some courses. A critical abstract accomplishes the same goals as the other types of abstract, but will also relate the study or work being discussed to the writer’s own research. It may critique the research design or methods. [5] X Trustworthy Source University of North Carolina Writing Center UNC's on-campus and online instructional service that provides assistance to students, faculty, and others during the writing process Go to source

Writing Your Abstract

- Why did you decide to do this study or project?

- How did you conduct your research?

- What did you find?

- Why is this research and your findings important?

- Why should someone read your entire essay?

- What problem is your research trying to better understand or solve?

- What is the scope of your study - a general problem, or something specific?

- What is your main claim or argument?

- Discuss your own research including the variables and your approach.

- Describe the evidence you have to support your claim

- Give an overview of your most important sources.

- What answer did you reach from your research or study?

- Was your hypothesis or argument supported?

- What are the general findings?

- What are the implications of your work?

- Are your results general or very specific?

Formatting Your Abstract

- Many journals have specific style guides for abstracts. If you’ve been given a set of rules or guidelines, follow them to the letter. [8] X Trustworthy Source PubMed Central Journal archive from the U.S. National Institutes of Health Go to source

- Avoid using direct acronyms or abbreviations in the abstract, as these will need to be explained in order to make sense to the reader. That uses up precious writing room, and should generally be avoided.

- If your topic is about something well-known enough, you can reference the names of people or places that your paper focuses on.

- Don’t include tables, figures, sources, or long quotations in your abstract. These take up too much room and usually aren’t what your readers want from an abstract anyway. [9] X Research source

- For example, if you’re writing a paper on the cultural differences in perceptions of schizophrenia, be sure to use words like “schizophrenia,” “cross-cultural,” “culture-bound,” “mental illness,” and “societal acceptance.” These might be search terms people use when looking for a paper on your subject.

- Make sure to avoid jargon. This specialized vocabulary may not be understood by general readers in your area and can cause confusion. [12] X Research source

- Consulting with your professor, a colleague in your field, or a tutor or writing center consultant can be very helpful. If you have these resources available to you, use them!

- Asking for assistance can also let you know about any conventions in your field. For example, it is very common to use the passive voice (“experiments were performed”) in the sciences. However, in the humanities active voice is usually preferred.

Sample Abstracts and Outline

Community Q&A

- Abstracts are typically a paragraph or two and should be no more than 10% of the length of the full essay. Look at other abstracts in similar publications for an idea of how yours should go. [13] X Research source Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Consider carefully how technical the paper or the abstract should be. It is often reasonable to assume that your readers have some understanding of your field and the specific language it entails, but anything you can do to make the abstract more easily readable is a good thing. Thanks Helpful 2 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/abstracts/

- ↑ http://writing.wisc.edu/Handbook/presentations_abstracts_examples.html

- ↑ http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/656/1/

- ↑ https://www.ece.cmu.edu/~koopman/essays/abstract.html

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/656/1/

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3136027/

- ↑ http://writing.wisc.edu/Handbook/presentations_abstracts.html

About This Article

To write an abstract, start with a short paragraph that explains the purpose of your paper and what it's about. Then, write a paragraph explaining any arguments or claims you make in your paper. Follow that with a third paragraph that details the research methods you used and any evidence you found for your claims. Finally, conclude your abstract with a brief section that tells readers why your findings are important. To learn how to properly format your abstract, read the article! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

May 21, 2017

Did this article help you?

Rohit Payal

Aug 5, 2018

Nila Anggreni Roni

Feb 6, 2017

Aug 27, 2019

Mike Bossert

Dec 27, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Level up your tech skills and stay ahead of the curve

Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Definition and Purpose of Abstracts

An abstract is a short summary of your (published or unpublished) research paper, usually about a paragraph (c. 6-7 sentences, 150-250 words) long. A well-written abstract serves multiple purposes:

- an abstract lets readers get the gist or essence of your paper or article quickly, in order to decide whether to read the full paper;

- an abstract prepares readers to follow the detailed information, analyses, and arguments in your full paper;

- and, later, an abstract helps readers remember key points from your paper.

It’s also worth remembering that search engines and bibliographic databases use abstracts, as well as the title, to identify key terms for indexing your published paper. So what you include in your abstract and in your title are crucial for helping other researchers find your paper or article.

If you are writing an abstract for a course paper, your professor may give you specific guidelines for what to include and how to organize your abstract. Similarly, academic journals often have specific requirements for abstracts. So in addition to following the advice on this page, you should be sure to look for and follow any guidelines from the course or journal you’re writing for.

The Contents of an Abstract

Abstracts contain most of the following kinds of information in brief form. The body of your paper will, of course, develop and explain these ideas much more fully. As you will see in the samples below, the proportion of your abstract that you devote to each kind of information—and the sequence of that information—will vary, depending on the nature and genre of the paper that you are summarizing in your abstract. And in some cases, some of this information is implied, rather than stated explicitly. The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , which is widely used in the social sciences, gives specific guidelines for what to include in the abstract for different kinds of papers—for empirical studies, literature reviews or meta-analyses, theoretical papers, methodological papers, and case studies.

Here are the typical kinds of information found in most abstracts:

- the context or background information for your research; the general topic under study; the specific topic of your research

- the central questions or statement of the problem your research addresses

- what’s already known about this question, what previous research has done or shown

- the main reason(s) , the exigency, the rationale , the goals for your research—Why is it important to address these questions? Are you, for example, examining a new topic? Why is that topic worth examining? Are you filling a gap in previous research? Applying new methods to take a fresh look at existing ideas or data? Resolving a dispute within the literature in your field? . . .

- your research and/or analytical methods

- your main findings , results , or arguments

- the significance or implications of your findings or arguments.

Your abstract should be intelligible on its own, without a reader’s having to read your entire paper. And in an abstract, you usually do not cite references—most of your abstract will describe what you have studied in your research and what you have found and what you argue in your paper. In the body of your paper, you will cite the specific literature that informs your research.

When to Write Your Abstract

Although you might be tempted to write your abstract first because it will appear as the very first part of your paper, it’s a good idea to wait to write your abstract until after you’ve drafted your full paper, so that you know what you’re summarizing.

What follows are some sample abstracts in published papers or articles, all written by faculty at UW-Madison who come from a variety of disciplines. We have annotated these samples to help you see the work that these authors are doing within their abstracts.

Choosing Verb Tenses within Your Abstract

The social science sample (Sample 1) below uses the present tense to describe general facts and interpretations that have been and are currently true, including the prevailing explanation for the social phenomenon under study. That abstract also uses the present tense to describe the methods, the findings, the arguments, and the implications of the findings from their new research study. The authors use the past tense to describe previous research.

The humanities sample (Sample 2) below uses the past tense to describe completed events in the past (the texts created in the pulp fiction industry in the 1970s and 80s) and uses the present tense to describe what is happening in those texts, to explain the significance or meaning of those texts, and to describe the arguments presented in the article.

The science samples (Samples 3 and 4) below use the past tense to describe what previous research studies have done and the research the authors have conducted, the methods they have followed, and what they have found. In their rationale or justification for their research (what remains to be done), they use the present tense. They also use the present tense to introduce their study (in Sample 3, “Here we report . . .”) and to explain the significance of their study (In Sample 3, This reprogramming . . . “provides a scalable cell source for. . .”).

Sample Abstract 1

From the social sciences.

Reporting new findings about the reasons for increasing economic homogamy among spouses

Gonalons-Pons, Pilar, and Christine R. Schwartz. “Trends in Economic Homogamy: Changes in Assortative Mating or the Division of Labor in Marriage?” Demography , vol. 54, no. 3, 2017, pp. 985-1005.

![how to create an abstract for a presentation “The growing economic resemblance of spouses has contributed to rising inequality by increasing the number of couples in which there are two high- or two low-earning partners. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the topic under study (the “economic resemblance of spouses”). This sentence also implies the question underlying this research study: what are the various causes—and the interrelationships among them—for this trend?] The dominant explanation for this trend is increased assortative mating. Previous research has primarily relied on cross-sectional data and thus has been unable to disentangle changes in assortative mating from changes in the division of spouses’ paid labor—a potentially key mechanism given the dramatic rise in wives’ labor supply. [Annotation for the previous two sentences: These next two sentences explain what previous research has demonstrated. By pointing out the limitations in the methods that were used in previous studies, they also provide a rationale for new research.] We use data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to decompose the increase in the correlation between spouses’ earnings and its contribution to inequality between 1970 and 2013 into parts due to (a) changes in assortative mating, and (b) changes in the division of paid labor. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The data, research and analytical methods used in this new study.] Contrary to what has often been assumed, the rise of economic homogamy and its contribution to inequality is largely attributable to changes in the division of paid labor rather than changes in sorting on earnings or earnings potential. Our findings indicate that the rise of economic homogamy cannot be explained by hypotheses centered on meeting and matching opportunities, and they show where in this process inequality is generated and where it is not.” (p. 985) [Annotation for the previous two sentences: The major findings from and implications and significance of this study.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-1.png)

Sample Abstract 2

From the humanities.

Analyzing underground pulp fiction publications in Tanzania, this article makes an argument about the cultural significance of those publications

Emily Callaci. “Street Textuality: Socialism, Masculinity, and Urban Belonging in Tanzania’s Pulp Fiction Publishing Industry, 1975-1985.” Comparative Studies in Society and History , vol. 59, no. 1, 2017, pp. 183-210.

![how to create an abstract for a presentation “From the mid-1970s through the mid-1980s, a network of young urban migrant men created an underground pulp fiction publishing industry in the city of Dar es Salaam. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the context for this research and announces the topic under study.] As texts that were produced in the underground economy of a city whose trajectory was increasingly charted outside of formalized planning and investment, these novellas reveal more than their narrative content alone. These texts were active components in the urban social worlds of the young men who produced them. They reveal a mode of urbanism otherwise obscured by narratives of decolonization, in which urban belonging was constituted less by national citizenship than by the construction of social networks, economic connections, and the crafting of reputations. This article argues that pulp fiction novellas of socialist era Dar es Salaam are artifacts of emergent forms of male sociability and mobility. In printing fictional stories about urban life on pilfered paper and ink, and distributing their texts through informal channels, these writers not only described urban communities, reputations, and networks, but also actually created them.” (p. 210) [Annotation for the previous sentences: The remaining sentences in this abstract interweave other essential information for an abstract for this article. The implied research questions: What do these texts mean? What is their historical and cultural significance, produced at this time, in this location, by these authors? The argument and the significance of this analysis in microcosm: these texts “reveal a mode or urbanism otherwise obscured . . .”; and “This article argues that pulp fiction novellas. . . .” This section also implies what previous historical research has obscured. And through the details in its argumentative claims, this section of the abstract implies the kinds of methods the author has used to interpret the novellas and the concepts under study (e.g., male sociability and mobility, urban communities, reputations, network. . . ).]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-2.png)

Sample Abstract/Summary 3

From the sciences.

Reporting a new method for reprogramming adult mouse fibroblasts into induced cardiac progenitor cells

Lalit, Pratik A., Max R. Salick, Daryl O. Nelson, Jayne M. Squirrell, Christina M. Shafer, Neel G. Patel, Imaan Saeed, Eric G. Schmuck, Yogananda S. Markandeya, Rachel Wong, Martin R. Lea, Kevin W. Eliceiri, Timothy A. Hacker, Wendy C. Crone, Michael Kyba, Daniel J. Garry, Ron Stewart, James A. Thomson, Karen M. Downs, Gary E. Lyons, and Timothy J. Kamp. “Lineage Reprogramming of Fibroblasts into Proliferative Induced Cardiac Progenitor Cells by Defined Factors.” Cell Stem Cell , vol. 18, 2016, pp. 354-367.

![how to create an abstract for a presentation “Several studies have reported reprogramming of fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes; however, reprogramming into proliferative induced cardiac progenitor cells (iCPCs) remains to be accomplished. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence announces the topic under study, summarizes what’s already known or been accomplished in previous research, and signals the rationale and goals are for the new research and the problem that the new research solves: How can researchers reprogram fibroblasts into iCPCs?] Here we report that a combination of 11 or 5 cardiac factors along with canonical Wnt and JAK/STAT signaling reprogrammed adult mouse cardiac, lung, and tail tip fibroblasts into iCPCs. The iCPCs were cardiac mesoderm-restricted progenitors that could be expanded extensively while maintaining multipo-tency to differentiate into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells in vitro. Moreover, iCPCs injected into the cardiac crescent of mouse embryos differentiated into cardiomyocytes. iCPCs transplanted into the post-myocardial infarction mouse heart improved survival and differentiated into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells. [Annotation for the previous four sentences: The methods the researchers developed to achieve their goal and a description of the results.] Lineage reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs provides a scalable cell source for drug discovery, disease modeling, and cardiac regenerative therapy.” (p. 354) [Annotation for the previous sentence: The significance or implications—for drug discovery, disease modeling, and therapy—of this reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-3.png)

Sample Abstract 4, a Structured Abstract

Reporting results about the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis, from a rigorously controlled study

Note: This journal requires authors to organize their abstract into four specific sections, with strict word limits. Because the headings for this structured abstract are self-explanatory, we have chosen not to add annotations to this sample abstract.

Wald, Ellen R., David Nash, and Jens Eickhoff. “Effectiveness of Amoxicillin/Clavulanate Potassium in the Treatment of Acute Bacterial Sinusitis in Children.” Pediatrics , vol. 124, no. 1, 2009, pp. 9-15.

“OBJECTIVE: The role of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis (ABS) in children is controversial. The purpose of this study was to determine the effectiveness of high-dose amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate in the treatment of children diagnosed with ABS.

METHODS : This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Children 1 to 10 years of age with a clinical presentation compatible with ABS were eligible for participation. Patients were stratified according to age (<6 or ≥6 years) and clinical severity and randomly assigned to receive either amoxicillin (90 mg/kg) with potassium clavulanate (6.4 mg/kg) or placebo. A symptom survey was performed on days 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 20, and 30. Patients were examined on day 14. Children’s conditions were rated as cured, improved, or failed according to scoring rules.

RESULTS: Two thousand one hundred thirty-five children with respiratory complaints were screened for enrollment; 139 (6.5%) had ABS. Fifty-eight patients were enrolled, and 56 were randomly assigned. The mean age was 6630 months. Fifty (89%) patients presented with persistent symptoms, and 6 (11%) presented with nonpersistent symptoms. In 24 (43%) children, the illness was classified as mild, whereas in the remaining 32 (57%) children it was severe. Of the 28 children who received the antibiotic, 14 (50%) were cured, 4 (14%) were improved, 4(14%) experienced treatment failure, and 6 (21%) withdrew. Of the 28children who received placebo, 4 (14%) were cured, 5 (18%) improved, and 19 (68%) experienced treatment failure. Children receiving the antibiotic were more likely to be cured (50% vs 14%) and less likely to have treatment failure (14% vs 68%) than children receiving the placebo.

CONCLUSIONS : ABS is a common complication of viral upper respiratory infections. Amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate results in significantly more cures and fewer failures than placebo, according to parental report of time to resolution.” (9)

Some Excellent Advice about Writing Abstracts for Basic Science Research Papers, by Professor Adriano Aguzzi from the Institute of Neuropathology at the University of Zurich:

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

- Search Events

Login/Register

How to Write an Abstract for a Conference: The Ultimate Guide

Are you thinking about attending a conference? If so, you will likely be asked to submit an abstract beforehand. An abstract is an ultra-brief summary of your proposed presentation; it should be no longer than 300 words and contain just the key points of your speech. A conference abstract is also known as a registration prospectus, an information document or a proposal. It is effectively a pitch document that explains why your speech would be of value to the audience at that particular conference – and why they need to hear it from you rather than anyone else! Creating an effective abstract is not always easy, and if this is the first time you have been asked to write one it can feel like quite a challenge. However, don’t panic! This blog post covers everything you need to know about how to write an abstract for a conference – read on to get started now!

What Exactly is an Abstract?

As we have already mentioned, an abstract is a super-brief summary of your proposed presentation. An abstract is used in several different fields and industries, but it’s most often found in the worlds of research, academia and business. An abstract allows the reader to get a quick overview of the main points of a longer document, such as a research paper, a dissertation or a business plan. It’s therefore a useful tool for helping people to get up to speed with your work quickly. Abstracts are also used to summarize conference presentations. A conference abstract is effectively a pitch document that explains why your speech would be of value to the audience at that particular conference – and why they need to hear it from you rather than anyone else!

Why is an abstract important?

Conference organizers need to be able to effectively communicate what the event is about, who should attend and what each speaker will be talking about. This can often be challenging when there are hundreds of different speakers and presentations on a wide range of topics. By creating an abstract, you’re helping the event organizers by providing them with a concise overview of your speech. This is useful because it allows the organizers to quickly and easily communicate the key points of your presentation to the rest of the conference team and conference attendees. Conference abstracts are, therefore, essential for pitching your speech to the organizer – and hopefully securing a place on the conference schedule!

How to write an effective abstract?

If you have ever read the abstracts for research papers, you’ll know that they can vary significantly in quality. Some are written in a very engaging, straightforward style that’s easy to understand, whereas others can be overly complex and difficult to comprehend. You want your abstract to be engaging and easy for your readers to understand, so we recommend keeping the following points in mind when you’re writing yours:

– Keep it brief. An abstract should be no longer than 300 words.

– Keep it relevant. An abstract is not a replacement for your actual presentation, so don’t include any information that isn’t relevant to the topic of your speech.

– Keep it accurate. Make sure that everything you include in your abstract is correct – if you get something wrong, you could have to correct it during your presentation!

– Keep it interesting. Your abstract should be engaging and exciting to read.

– Keep it professional. Even though it’s a short piece of writing, your abstract should be written professionally and engagingly.

Final words

As you can see, creating an abstract can be challenging, mainly if this is the first time you have been asked to write one. However, by following the tips and suggestions in this blog post, you should be able to create an effective, engaging and easy-to-understand abstract. With a little preparation, you should be able to create a compelling abstract that will help you get your foot on the conference speaking circuit!

Thank you liked those tips.

Good advice

Write a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Search Blog

Recent posts.

Navigating the Future of Education: Academic Conferences as a Hub for Insights, Ideas, and Best Practices

How to Prepare for a Conference: A Checklist of Tips to Make the Most of Your Experience

How a Virtual Conference Can Help You Reach Your Professional Goals

Create an Event Website: A Tutorial to Design.

7 Tips for How to Network at a Conference

ASCO Connection

The professional networking site for asco's worldwide oncology community, search form, presentation tips for first-time abstract presenters.

Apr 28, 2020

By Muhamad Alhaj Moustafa, MD

The ASCO Annual Meeting is the largest educational and scientific conference in oncology. In 2019, ASCO attracted more than 42,000 attendees from all over the world. The fundamental goal of such a scientific meeting is to share knowledge and accelerate scientific advances. Investigators use different types of presentations as methods to disseminate and share their valuable work with others in the field. This is an important aspect of promoting their scientific careers. These presentations are important to communicate findings and connect with others in the field with similar interests. During these meetings, your research work has the potential to get the highest attention and visibility. This is a great opportunity to get feedback on your work and to build future collaborations and valuable connections.

I attended my first ASCO Annual Meeting as a post-doctoral fellow in 2015. I remember being so excited about my abstract acceptance but also stressed out about presenting at such a large-scale meeting. I had to read a lot of articles and seek advice from mentors on how to prepare the perfect presentation and how to connect with and impress the audience.