If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

High school biology

Course: high school biology > unit 1.

- Biology overview

- Preparing to study biology

- What is life?

- The scientific method

- Data to justify experimental claims examples

- Scientific method and data analysis

- Introduction to experimental design

- Controlled experiments

Biology and the scientific method review

- Experimental design and bias

The nature of biology

Properties of life.

- Organization: Living things are highly organized (meaning they contain specialized, coordinated parts) and are made up of one or more cells .

- Metabolism: Living things must use energy and consume nutrients to carry out the chemical reactions that sustain life. The sum total of the biochemical reactions occurring in an organism is called its metabolism .

- Homeostasis : Living organisms regulate their internal environment to maintain the relatively narrow range of conditions needed for cell function.

- Growth : Living organisms undergo regulated growth. Individual cells become larger in size, and multicellular organisms accumulate many cells through cell division.

- Reproduction : Living organisms can reproduce themselves to create new organisms.

- Response : Living organisms respond to stimuli or changes in their environment.

- Evolution : Populations of living organisms can undergo evolution , meaning that the genetic makeup of a population may change over time.

Scientific methodology

Scientific method example: failure to toast.

- Observation: the toaster won't toast.

- Question: Why won't my toaster toast?

- Hypothesis: Maybe the outlet is broken.

- Prediction: If I plug the toaster into a different outlet, then it will toast the bread.

- Test of prediction: Plug the toaster into a different outlet and try again.

- Iteration time!

Experimental design

Reducing errors and bias.

- Having a large sample size in the experiment: This helps to account for any small differences among the test subjects that may provide unexpected results.

- Repeating experimental trials multiple times: Errors may result from slight differences in test subjects, or mistakes in methodology or data collection. Repeating trials helps reduce those effects.

- Including all data points: Sometimes it is tempting to throw away data points that are inconsistent with the proposed hypothesis. However, this makes for an inaccurate study! All data points need to be included, whether they support the hypothesis or not.

- Using placebos , when appropriate: Placebos prevent the test subjects from knowing whether they received a real therapeutic substance. This helps researchers determine whether a substance has a true effect.

- Implementing double-blind studies , when appropriate: Double-blind studies prevent researchers from knowing the status of a particular participant. This helps eliminate observer bias.

Communicating findings

Things to remember.

- A hypothesis is not necessarily the right explanation. Instead, it is a possible explanation that can be tested to see if it is likely correct, or if a new hypothesis needs to be made.

- Not all explanations can be considered a hypothesis. A hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable in order to be valid. For example, “The universe is beautiful" is not a good hypothesis, because there is no experiment that could test this statement and show it to be false.

- In most cases, the scientific method is an iterative process. In other words, it's a cycle rather than a straight line. The result of one experiment often becomes feedback that raises questions for more experimentation.

- Scientists use the word "theory" in a very different way than non-scientists. When many people say "I have a theory," they really mean "I have a guess." Scientific theories, on the other hand, are well-tested and highly reliable scientific explanations of natural phenomena. They unify many repeated observations and data collected from lots of experiments.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.14: Experiments and Hypotheses

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 43504

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Now we’ll focus on the methods of scientific inquiry. Science often involves making observations and developing hypotheses. Experiments and further observations are often used to test the hypotheses.

A scientific experiment is a carefully organized procedure in which the scientist intervenes in a system to change something, then observes the result of the change. Scientific inquiry often involves doing experiments, though not always. For example, a scientist studying the mating behaviors of ladybugs might begin with detailed observations of ladybugs mating in their natural habitats. While this research may not be experimental, it is scientific: it involves careful and verifiable observation of the natural world. The same scientist might then treat some of the ladybugs with a hormone hypothesized to trigger mating and observe whether these ladybugs mated sooner or more often than untreated ones. This would qualify as an experiment because the scientist is now making a change in the system and observing the effects.

Forming a Hypothesis

When conducting scientific experiments, researchers develop hypotheses to guide experimental design. A hypothesis is a suggested explanation that is both testable and falsifiable. You must be able to test your hypothesis, and it must be possible to prove your hypothesis true or false.

For example, Michael observes that maple trees lose their leaves in the fall. He might then propose a possible explanation for this observation: “cold weather causes maple trees to lose their leaves in the fall.” This statement is testable. He could grow maple trees in a warm enclosed environment such as a greenhouse and see if their leaves still dropped in the fall. The hypothesis is also falsifiable. If the leaves still dropped in the warm environment, then clearly temperature was not the main factor in causing maple leaves to drop in autumn.

In the Try It below, you can practice recognizing scientific hypotheses. As you consider each statement, try to think as a scientist would: can I test this hypothesis with observations or experiments? Is the statement falsifiable? If the answer to either of these questions is “no,” the statement is not a valid scientific hypothesis.

Practice Questions

Determine whether each following statement is a scientific hypothesis.

Air pollution from automobile exhaust can trigger symptoms in people with asthma.

- No. This statement is not testable or falsifiable.

- No. This statement is not testable.

- No. This statement is not falsifiable.

- Yes. This statement is testable and falsifiable.

[reveal-answer q=”429550″] Show Answer [/reveal-answer] [hidden-answer a=”429550″]d: Yes. This statement is testable and falsifiable. This could be tested with a number of different kinds of observations and experiments, and it is possible to gather evidence that indicates that air pollution is not linked with asthma.

[/hidden-answer]

Natural disasters, such as tornadoes, are punishments for bad thoughts and behaviors.

[reveal-answer q=”74245″]Show Answer[/reveal-answer] [hidden-answer a=”74245″]

a: No. This statement is not testable or falsifiable. “Bad thoughts and behaviors” are excessively vague and subjective variables that would be impossible to measure or agree upon in a reliable way. The statement might be “falsifiable” if you came up with a counterexample: a “wicked” place that was not punished by a natural disaster. But some would question whether the people in that place were really wicked, and others would continue to predict that a natural disaster was bound to strike that place at some point. There is no reason to suspect that people’s immoral behavior affects the weather unless you bring up the intervention of a supernatural being, making this idea even harder to test.

Testing a Vaccine

Let’s examine the scientific process by discussing an actual scientific experiment conducted by researchers at the University of Washington. These researchers investigated whether a vaccine may reduce the incidence of the human papillomavirus (HPV). The experimental process and results were published in an article titled, “ A controlled trial of a human papillomavirus type 16 vaccine .”

Preliminary observations made by the researchers who conducted the HPV experiment are listed below:

- Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted virus in the United States.

- There are about 40 different types of HPV. A significant number of people that have HPV are unaware of it because many of these viruses cause no symptoms.

- Some types of HPV can cause cervical cancer.

- About 4,000 women a year die of cervical cancer in the United States.

Practice Question

Researchers have developed a potential vaccine against HPV and want to test it. What is the first testable hypothesis that the researchers should study?

- HPV causes cervical cancer.

- People should not have unprotected sex with many partners.

- People who get the vaccine will not get HPV.

- The HPV vaccine will protect people against cancer.

[reveal-answer q=”20917″] Show Answer [/reveal-answer] [hidden-answer a=”20917″]Hypothesis A is not the best choice because this information is already known from previous studies. Hypothesis B is not testable because scientific hypotheses are not value statements; they do not include judgments like “should,” “better than,” etc. Scientific evidence certainly might support this value judgment, but a hypothesis would take a different form: “Having unprotected sex with many partners increases a person’s risk for cervical cancer.” Before the researchers can test if the vaccine protects against cancer (hypothesis D), they want to test if it protects against the virus. This statement will make an excellent hypothesis for the next study. The researchers should first test hypothesis C—whether or not the new vaccine can prevent HPV.[/hidden-answer]

Experimental Design

You’ve successfully identified a hypothesis for the University of Washington’s study on HPV: People who get the HPV vaccine will not get HPV.

The next step is to design an experiment that will test this hypothesis. There are several important factors to consider when designing a scientific experiment. First, scientific experiments must have an experimental group. This is the group that receives the experimental treatment necessary to address the hypothesis.

The experimental group receives the vaccine, but how can we know if the vaccine made a difference? Many things may change HPV infection rates in a group of people over time. To clearly show that the vaccine was effective in helping the experimental group, we need to include in our study an otherwise similar control group that does not get the treatment. We can then compare the two groups and determine if the vaccine made a difference. The control group shows us what happens in the absence of the factor under study.

However, the control group cannot get “nothing.” Instead, the control group often receives a placebo. A placebo is a procedure that has no expected therapeutic effect—such as giving a person a sugar pill or a shot containing only plain saline solution with no drug. Scientific studies have shown that the “placebo effect” can alter experimental results because when individuals are told that they are or are not being treated, this knowledge can alter their actions or their emotions, which can then alter the results of the experiment.

Moreover, if the doctor knows which group a patient is in, this can also influence the results of the experiment. Without saying so directly, the doctor may show—through body language or other subtle cues—his or her views about whether the patient is likely to get well. These errors can then alter the patient’s experience and change the results of the experiment. Therefore, many clinical studies are “double blind.” In these studies, neither the doctor nor the patient knows which group the patient is in until all experimental results have been collected.

Both placebo treatments and double-blind procedures are designed to prevent bias. Bias is any systematic error that makes a particular experimental outcome more or less likely. Errors can happen in any experiment: people make mistakes in measurement, instruments fail, computer glitches can alter data. But most such errors are random and don’t favor one outcome over another. Patients’ belief in a treatment can make it more likely to appear to “work.” Placebos and double-blind procedures are used to level the playing field so that both groups of study subjects are treated equally and share similar beliefs about their treatment.

The scientists who are researching the effectiveness of the HPV vaccine will test their hypothesis by separating 2,392 young women into two groups: the control group and the experimental group. Answer the following questions about these two groups.

- This group is given a placebo.

- This group is deliberately infected with HPV.

- This group is given nothing.

- This group is given the HPV vaccine.

[reveal-answer q=”918962″] Show Answers [/reveal-answer] [hidden-answer a=”918962″]

- a: This group is given a placebo. A placebo will be a shot, just like the HPV vaccine, but it will have no active ingredient. It may change peoples’ thinking or behavior to have such a shot given to them, but it will not stimulate the immune systems of the subjects in the same way as predicted for the vaccine itself.

- d: This group is given the HPV vaccine. The experimental group will receive the HPV vaccine and researchers will then be able to see if it works, when compared to the control group.

Experimental Variables

A variable is a characteristic of a subject (in this case, of a person in the study) that can vary over time or among individuals. Sometimes a variable takes the form of a category, such as male or female; often a variable can be measured precisely, such as body height. Ideally, only one variable is different between the control group and the experimental group in a scientific experiment. Otherwise, the researchers will not be able to determine which variable caused any differences seen in the results. For example, imagine that the people in the control group were, on average, much more sexually active than the people in the experimental group. If, at the end of the experiment, the control group had a higher rate of HPV infection, could you confidently determine why? Maybe the experimental subjects were protected by the vaccine, but maybe they were protected by their low level of sexual contact.

To avoid this situation, experimenters make sure that their subject groups are as similar as possible in all variables except for the variable that is being tested in the experiment. This variable, or factor, will be deliberately changed in the experimental group. The one variable that is different between the two groups is called the independent variable. An independent variable is known or hypothesized to cause some outcome. Imagine an educational researcher investigating the effectiveness of a new teaching strategy in a classroom. The experimental group receives the new teaching strategy, while the control group receives the traditional strategy. It is the teaching strategy that is the independent variable in this scenario. In an experiment, the independent variable is the variable that the scientist deliberately changes or imposes on the subjects.

Dependent variables are known or hypothesized consequences; they are the effects that result from changes or differences in an independent variable. In an experiment, the dependent variables are those that the scientist measures before, during, and particularly at the end of the experiment to see if they have changed as expected. The dependent variable must be stated so that it is clear how it will be observed or measured. Rather than comparing “learning” among students (which is a vague and difficult to measure concept), an educational researcher might choose to compare test scores, which are very specific and easy to measure.

In any real-world example, many, many variables MIGHT affect the outcome of an experiment, yet only one or a few independent variables can be tested. Other variables must be kept as similar as possible between the study groups and are called control variables . For our educational research example, if the control group consisted only of people between the ages of 18 and 20 and the experimental group contained people between the ages of 30 and 35, we would not know if it was the teaching strategy or the students’ ages that played a larger role in the results. To avoid this problem, a good study will be set up so that each group contains students with a similar age profile. In a well-designed educational research study, student age will be a controlled variable, along with other possibly important factors like gender, past educational achievement, and pre-existing knowledge of the subject area.

What is the independent variable in this experiment?

- Sex (all of the subjects will be female)

- Presence or absence of the HPV vaccine

- Presence or absence of HPV (the virus)

[reveal-answer q=”68680″]Show Answer[/reveal-answer] [hidden-answer a=”68680″]Answer b. Presence or absence of the HPV vaccine. This is the variable that is different between the control and the experimental groups. All the subjects in this study are female, so this variable is the same in all groups. In a well-designed study, the two groups will be of similar age. The presence or absence of the virus is what the researchers will measure at the end of the experiment. Ideally the two groups will both be HPV-free at the start of the experiment.

List three control variables other than age.

[practice-area rows=”3″][/practice-area] [reveal-answer q=”903121″]Show Answer[/reveal-answer] [hidden-answer a=”903121″]Some possible control variables would be: general health of the women, sexual activity, lifestyle, diet, socioeconomic status, etc.

What is the dependent variable in this experiment?

- Sex (male or female)

- Rates of HPV infection

- Age (years)

[reveal-answer q=”907103″]Show Answer[/reveal-answer] [hidden-answer a=”907103″]Answer b. Rates of HPV infection. The researchers will measure how many individuals got infected with HPV after a given period of time.[/hidden-answer]

Contributors and Attributions

- Revision and adaptation. Authored by : Shelli Carter and Lumen Learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Scientific Inquiry. Provided by : Open Learning Initiative. Located at : https://oli.cmu.edu/jcourse/workbook/activity/page?context=434a5c2680020ca6017c03488572e0f8 . Project : Introduction to Biology (Open + Free). License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

Scientific Hypothesis, Model, Theory, and Law

Understanding the Difference Between Basic Scientific Terms

Hero Images / Getty Images

- Chemical Laws

- Periodic Table

- Projects & Experiments

- Scientific Method

- Biochemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Medical Chemistry

- Chemistry In Everyday Life

- Famous Chemists

- Activities for Kids

- Abbreviations & Acronyms

- Weather & Climate

- Ph.D., Biomedical Sciences, University of Tennessee at Knoxville

- B.A., Physics and Mathematics, Hastings College

Words have precise meanings in science. For example, "theory," "law," and "hypothesis" don't all mean the same thing. Outside of science, you might say something is "just a theory," meaning it's a supposition that may or may not be true. In science, however, a theory is an explanation that generally is accepted to be true. Here's a closer look at these important, commonly misused terms.

A hypothesis is an educated guess, based on observation. It's a prediction of cause and effect. Usually, a hypothesis can be supported or refuted through experimentation or more observation. A hypothesis can be disproven but not proven to be true.

Example: If you see no difference in the cleaning ability of various laundry detergents, you might hypothesize that cleaning effectiveness is not affected by which detergent you use. This hypothesis can be disproven if you observe a stain is removed by one detergent and not another. On the other hand, you cannot prove the hypothesis. Even if you never see a difference in the cleanliness of your clothes after trying 1,000 detergents, there might be one more you haven't tried that could be different.

Scientists often construct models to help explain complex concepts. These can be physical models like a model volcano or atom or conceptual models like predictive weather algorithms. A model doesn't contain all the details of the real deal, but it should include observations known to be valid.

Example: The Bohr model shows electrons orbiting the atomic nucleus, much the same way as the way planets revolve around the sun. In reality, the movement of electrons is complicated but the model makes it clear that protons and neutrons form a nucleus and electrons tend to move around outside the nucleus.

A scientific theory summarizes a hypothesis or group of hypotheses that have been supported with repeated testing. A theory is valid as long as there is no evidence to dispute it. Therefore, theories can be disproven. Basically, if evidence accumulates to support a hypothesis, then the hypothesis can become accepted as a good explanation of a phenomenon. One definition of a theory is to say that it's an accepted hypothesis.

Example: It is known that on June 30, 1908, in Tunguska, Siberia, there was an explosion equivalent to the detonation of about 15 million tons of TNT. Many hypotheses have been proposed for what caused the explosion. It was theorized that the explosion was caused by a natural extraterrestrial phenomenon , and was not caused by man. Is this theory a fact? No. The event is a recorded fact. Is this theory, generally accepted to be true, based on evidence to-date? Yes. Can this theory be shown to be false and be discarded? Yes.

A scientific law generalizes a body of observations. At the time it's made, no exceptions have been found to a law. Scientific laws explain things but they do not describe them. One way to tell a law and a theory apart is to ask if the description gives you the means to explain "why." The word "law" is used less and less in science, as many laws are only true under limited circumstances.

Example: Consider Newton's Law of Gravity . Newton could use this law to predict the behavior of a dropped object but he couldn't explain why it happened.

As you can see, there is no "proof" or absolute "truth" in science. The closest we get are facts, which are indisputable observations. Note, however, if you define proof as arriving at a logical conclusion, based on the evidence, then there is "proof" in science. Some work under the definition that to prove something implies it can never be wrong, which is different. If you're asked to define the terms hypothesis, theory, and law, keep in mind the definitions of proof and of these words can vary slightly depending on the scientific discipline. What's important is to realize they don't all mean the same thing and cannot be used interchangeably.

- Theory Definition in Science

- Hypothesis, Model, Theory, and Law

- What Is a Scientific or Natural Law?

- Scientific Hypothesis Examples

- The Continental Drift Theory: Revolutionary and Significant

- What 'Fail to Reject' Means in a Hypothesis Test

- What Is a Hypothesis? (Science)

- Hypothesis Definition (Science)

- Definition of a Hypothesis

- Processual Archaeology

- The Basics of Physics in Scientific Study

- What Is the Difference Between Hard and Soft Science?

- Tips on Winning the Debate on Evolution

- Geological Thinking: Method of Multiple Working Hypotheses

- 5 Common Misconceptions About Evolution

- Deductive Versus Inductive Reasoning

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.2: Science- Reproducible, Testable, Tentative, Predictive, and Explanatory

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 152134

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

- Describe the differences between hypothesis and theory as scientific terms.

- Describe the difference between a theory and scientific law.

- Identify the components of the scientific method.

Although many have taken science classes throughout their course of studies, incorrect or misleading ideas about some of the most important and basic principles in science are still commonplace. Most students have heard of hypotheses , theories , and laws , but what do these terms really mean? Before you read this section, consider what you have learned about these terms previously, and what they mean to you. When reading, notice if any of the text contradicts what you previously thought. What do you read that supports what you thought?

What is a Fact?

A fact is a basic statement established by experiment or observation. All facts are true under the specific conditions of the observation.

What is a Hypothesis?

One of the most common terms used in science classes is a " hypothesis ". The word can have many different definitions, dependent on the context in which it is being used:

- An educated guess: a scientific hypothesis provides a suggested solution based on evidence.

- Prediction: if you have ever carried out a science experiment, you probably made this type of hypothesis, in which you predicted the outcome of your experiment.

- Tentative or proposed explanation: hypotheses can be suggestions about why something is observed. In order for a hypothesis to be scientific, a scientist must be able to test the explanation to see if it works, and if it is able to correctly predict what will happen in a situation. For example, "if my hypothesis is correct, I should see _____ result when I perform _____ test."

A hypothesis is tentative; it can be easily changed.

What is a Theory?

The United States National Academy of Sciences describes a theory as:

"Some scientific explanations are so well established that no new evidence is likely to alter them. The explanation becomes a scientific theory. In everyday language a theory means a hunch or speculation. Not so in science. In science, the word theory refers to a comprehensive explanation of an important feature of nature supported by facts gathered over time. Theories also allow scientists to make predictions about as yet unobserved phenomena."

"A scientific theory is a well-substantiated explanation of some aspect of the natural world, based on a body of facts that have been repeatedly confirmed through observation and experimentation. Such fact-supported theories are not "guesses," but reliable accounts of the real world. The theory of biological evolution is more than "just a theory." It is as factual an explanation of the universe as the atomic theory of matter (stating that everything is made of atoms) or the germ theory of disease (which states that many diseases are caused by germs). Our understanding of gravity is still a work in progress. But the phenomenon of gravity, like evolution, is an accepted fact."

Note some key features of theories that are important to understand from this description:

- Theories are explanations of natural phenomenon. They aren't predictions (although we may use theories to make predictions). They are explanations of why something is observed.

- Theories aren't likely to change. They have a lot of support and are able to explain many observations satisfactorily. Theories can, indeed, be facts. Theories can change in some instances, but it is a long and difficult process. In order for a theory to change, there must be many observations or evidence that the theory cannot explain.

- Theories are not guesses. The phrase "just a theory" has no room in science. To be a scientific theory carries a lot of weight—it is not just one person's idea about something

Theories aren't likely to change.

What is a Law?

Scientific laws are similar to scientific theories in that they are principles that can be used to predict the behavior of the natural world. Both scientific laws and scientific theories are typically well-supported by observations and/or experimental evidence. Usually, scientific laws refer to rules for how nature will behave under certain conditions, frequently written as an equation. Scientific theories are overarching explanations of how nature works, and why it exhibits certain characteristics. As a comparison, theories explain why we observe what we do, and laws describe what happens.

For example, around the year 1800, Jacques Charles and other scientists were working with gases to, among other reasons, improve the design of the hot air balloon. These scientists found, after numerous tests, that certain patterns existed in their observations of gas behavior. If the temperature of the gas increased, the volume of the gas increased. This is known as a natural law. A law is a relationship that exists between variables in a group of data. Laws describe the patterns we see in large amounts of data, but do not describe why the patterns exist.

Laws vs Theories

A common misconception is that scientific theories are rudimentary ideas that will eventually graduate into scientific laws when enough data and evidence has been accumulated. A theory does not change into a scientific law with the accumulation of new or better evidence. Remember, theories are explanations; laws are patterns seen in large amounts of data, frequently written as an equation. A theory will always remain a theory, a law will always remain a law.

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\) What is the difference between scientific law and theory?

The Scientific Method

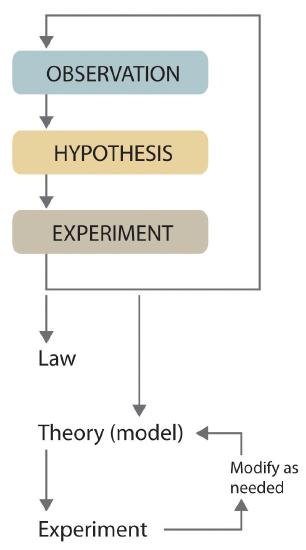

Scientists search for answers to questions and solutions to problems by using a procedure called the scientific method . This procedure consists of making observations, formulating hypotheses, and designing experiments, which in turn lead to additional observations, hypotheses, and experiments in repeated cycles (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)).

- Step 1: Make observations.

Observations can be qualitative or quantitative. Qualitative observations describe properties or occurrences in ways that do not rely on numbers. Examples of qualitative observations include the following: "the outside air temperature is cooler during the winter season," "table salt is a crystalline solid," "sulfur crystals are yellow," and "dissolving a penny in dilute nitric acid forms a blue solution and a brown gas." Quantitative observations are measurements, which by definition consist of both a number and a unit. Examples of quantitative observations include the following: "the melting point of crystalline sulfur is 115.21° Celsius," and "35.9 grams of table salt—the chemical name of which is sodium chloride—dissolve in 100 grams of water at 20° Celsius." For the question of the dinosaurs’ extinction, the initial observation was quantitative: iridium concentrations in sediments dating to 66 million years ago were 20–160 times higher than normal.

- Step 2: Formulate a hypothesis.

After deciding to learn more about an observation or a set of observations, scientists generally begin an investigation by forming a hypothesis, a tentative explanation for the observation(s). The hypothesis may not be correct, but it puts the scientist’s understanding of the system being studied into a form that can be tested. For example, the observation that we experience alternating periods of light and darkness which correspond to observed movements of the sun, moon, clouds, and shadows, is consistent with either of two hypotheses:

- Earth rotates on its axis every 24 hours, alternately exposing one side to the sun.

- The sun revolves around Earth every 24 hours.

Suitable experiments can be designed to choose between these two alternatives. In the case of disappearance of the dinosaurs, the hypothesis was that the impact of a large extraterrestrial object caused their extinction. Unfortunately (or perhaps fortunately), this hypothesis does not lend itself to direct testing by any obvious experiment, but scientists can collect additional data that either supports or refutes it.

Step 3: Design and perform experiments.

After a hypothesis has been formed, scientists conduct experiments to test its validity. Experiments are systematic observations or measurements, preferably made under controlled conditions—that is, under conditions in which a single variable changes.

- Step 4: Accept or modify the hypothesis.

A properly designed and executed experiment enables a scientist to determine whether the original hypothesis is valid. In the case of validity, the scientist can proceed to step 5. In other cases, experiments may demonstrate that the hypothesis is incorrect or that it must be modified, thus requiring further experimentation.

- Step 5: Development of a law and/or theory.

More experimental data are then collected and analyzed, at which point a scientist may begin to think that the results are sufficiently reproducible (i.e., dependable) to merit being summarized in a law—a verbal or mathematical description of a phenomenon that allows for general predictions. A law simply states what happens; it does not address the question of why.

One example of a law, the law of definite proportions (discovered by the French scientist Joseph Proust [1754–1826]), states that a chemical substance always contains the same proportions of elements by mass. Thus, sodium chloride (table salt) always contains the same proportion by mass of sodium to chlorine—in this case, 39.34% sodium and 60.66% chlorine by mass. Sucrose (table sugar) is always 42.11% carbon, 6.48% hydrogen, and 51.41% oxygen by mass.

Whereas a law states only what happens, a theory attempts to explain why nature behaves as it does. Laws are unlikely to change greatly over time, unless a major experimental error is discovered. A theory, in contrast, is incomplete and imperfect; it evolves with time to explain new facts as they are discovered.

Because scientists can enter the cycle shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) at any point, the actual application of the scientific method to different topics can take many different forms. For example, a scientist may start with a hypothesis formed by reading about work done by others in the field, rather than by making direct observations.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Classify each statement as a law, theory, experiment, hypothesis, or observation.

- Ice always floats on liquid water.

- Birds evolved from dinosaurs.

- Hot air is less dense than cold air, probably because the components of hot air are moving more rapidly.

- When 10 g of ice was added to 100 mL of water at 25°C, the temperature of the water decreased to 15.5°C after the ice melted.

- The ingredients of Ivory soap were analyzed to see whether it really is 99.44% pure, as advertised.

- This is a general statement of a relationship between the properties of liquid and solid water, so it is a law.

- This is a possible explanation for the origin of birds, so it is a hypothesis.

- This is a statement that tries to explain the relationship between the temperature and the density of air based on fundamental principles, so it is a theory.

- The temperature is measured before and after a change is made in a system, so these are observations.

- This is an analysis designed to test a hypothesis (in this case, the manufacturer’s claim of purity), so it is an experiment.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Classify each statement as a law, theory, experiment, hypothesis, qualitative observation, or quantitative observation.

- Measured amounts of acid were added to a Rolaids tablet to see whether it really “consumes 47 times its weight in excess stomach acid.”

- Heat always flows from hot objects to cooler ones, not in the opposite direction.

- The universe was formed by a massive explosion that propelled matter into a vacuum.

- Michael Jordan is the greatest pure shooter ever to play professional basketball.

- Limestone is relatively insoluble in water, but dissolves readily in dilute acid with the evolution of a gas.

- A hypothesis is a tentative explanation that can be tested by further investigation.

- A theory is a well-supported explanation of observations.

- A scientific law is a statement that summarizes the relationship between variables.

- An experiment is a controlled method of testing a hypothesis.

- Step 3: Test the hypothesis through experimentation.

Contributors and Attributions

Marisa Alviar-Agnew ( Sacramento City College )

Henry Agnew (UC Davis)

Science and the scientific method: Definitions and examples

Here's a look at the foundation of doing science — the scientific method.

The scientific method

Hypothesis, theory and law, a brief history of science, additional resources, bibliography.

Science is a systematic and logical approach to discovering how things in the universe work. It is also the body of knowledge accumulated through the discoveries about all the things in the universe.

The word "science" is derived from the Latin word "scientia," which means knowledge based on demonstrable and reproducible data, according to the Merriam-Webster dictionary . True to this definition, science aims for measurable results through testing and analysis, a process known as the scientific method. Science is based on fact, not opinion or preferences. The process of science is designed to challenge ideas through research. One important aspect of the scientific process is that it focuses only on the natural world, according to the University of California, Berkeley . Anything that is considered supernatural, or beyond physical reality, does not fit into the definition of science.

When conducting research, scientists use the scientific method to collect measurable, empirical evidence in an experiment related to a hypothesis (often in the form of an if/then statement) that is designed to support or contradict a scientific theory .

"As a field biologist, my favorite part of the scientific method is being in the field collecting the data," Jaime Tanner, a professor of biology at Marlboro College, told Live Science. "But what really makes that fun is knowing that you are trying to answer an interesting question. So the first step in identifying questions and generating possible answers (hypotheses) is also very important and is a creative process. Then once you collect the data you analyze it to see if your hypothesis is supported or not."

The steps of the scientific method go something like this, according to Highline College :

- Make an observation or observations.

- Form a hypothesis — a tentative description of what's been observed, and make predictions based on that hypothesis.

- Test the hypothesis and predictions in an experiment that can be reproduced.

- Analyze the data and draw conclusions; accept or reject the hypothesis or modify the hypothesis if necessary.

- Reproduce the experiment until there are no discrepancies between observations and theory. "Replication of methods and results is my favorite step in the scientific method," Moshe Pritsker, a former post-doctoral researcher at Harvard Medical School and CEO of JoVE, told Live Science. "The reproducibility of published experiments is the foundation of science. No reproducibility — no science."

Some key underpinnings to the scientific method:

- The hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable, according to North Carolina State University . Falsifiable means that there must be a possible negative answer to the hypothesis.

- Research must involve deductive reasoning and inductive reasoning . Deductive reasoning is the process of using true premises to reach a logical true conclusion while inductive reasoning uses observations to infer an explanation for those observations.

- An experiment should include a dependent variable (which does not change) and an independent variable (which does change), according to the University of California, Santa Barbara .

- An experiment should include an experimental group and a control group. The control group is what the experimental group is compared against, according to Britannica .

The process of generating and testing a hypothesis forms the backbone of the scientific method. When an idea has been confirmed over many experiments, it can be called a scientific theory. While a theory provides an explanation for a phenomenon, a scientific law provides a description of a phenomenon, according to The University of Waikato . One example would be the law of conservation of energy, which is the first law of thermodynamics that says that energy can neither be created nor destroyed.

A law describes an observed phenomenon, but it doesn't explain why the phenomenon exists or what causes it. "In science, laws are a starting place," said Peter Coppinger, an associate professor of biology and biomedical engineering at the Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. "From there, scientists can then ask the questions, 'Why and how?'"

Laws are generally considered to be without exception, though some laws have been modified over time after further testing found discrepancies. For instance, Newton's laws of motion describe everything we've observed in the macroscopic world, but they break down at the subatomic level.

This does not mean theories are not meaningful. For a hypothesis to become a theory, scientists must conduct rigorous testing, typically across multiple disciplines by separate groups of scientists. Saying something is "just a theory" confuses the scientific definition of "theory" with the layperson's definition. To most people a theory is a hunch. In science, a theory is the framework for observations and facts, Tanner told Live Science.

The earliest evidence of science can be found as far back as records exist. Early tablets contain numerals and information about the solar system , which were derived by using careful observation, prediction and testing of those predictions. Science became decidedly more "scientific" over time, however.

1200s: Robert Grosseteste developed the framework for the proper methods of modern scientific experimentation, according to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. His works included the principle that an inquiry must be based on measurable evidence that is confirmed through testing.

1400s: Leonardo da Vinci began his notebooks in pursuit of evidence that the human body is microcosmic. The artist, scientist and mathematician also gathered information about optics and hydrodynamics.

1500s: Nicolaus Copernicus advanced the understanding of the solar system with his discovery of heliocentrism. This is a model in which Earth and the other planets revolve around the sun, which is the center of the solar system.

1600s: Johannes Kepler built upon those observations with his laws of planetary motion. Galileo Galilei improved on a new invention, the telescope, and used it to study the sun and planets. The 1600s also saw advancements in the study of physics as Isaac Newton developed his laws of motion.

1700s: Benjamin Franklin discovered that lightning is electrical. He also contributed to the study of oceanography and meteorology. The understanding of chemistry also evolved during this century as Antoine Lavoisier, dubbed the father of modern chemistry , developed the law of conservation of mass.

1800s: Milestones included Alessandro Volta's discoveries regarding electrochemical series, which led to the invention of the battery. John Dalton also introduced atomic theory, which stated that all matter is composed of atoms that combine to form molecules. The basis of modern study of genetics advanced as Gregor Mendel unveiled his laws of inheritance. Later in the century, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen discovered X-rays , while George Ohm's law provided the basis for understanding how to harness electrical charges.

1900s: The discoveries of Albert Einstein , who is best known for his theory of relativity, dominated the beginning of the 20th century. Einstein's theory of relativity is actually two separate theories. His special theory of relativity, which he outlined in a 1905 paper, " The Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies ," concluded that time must change according to the speed of a moving object relative to the frame of reference of an observer. His second theory of general relativity, which he published as " The Foundation of the General Theory of Relativity ," advanced the idea that matter causes space to curve.

In 1952, Jonas Salk developed the polio vaccine , which reduced the incidence of polio in the United States by nearly 90%, according to Britannica . The following year, James D. Watson and Francis Crick discovered the structure of DNA , which is a double helix formed by base pairs attached to a sugar-phosphate backbone, according to the National Human Genome Research Institute .

2000s: The 21st century saw the first draft of the human genome completed, leading to a greater understanding of DNA. This advanced the study of genetics, its role in human biology and its use as a predictor of diseases and other disorders, according to the National Human Genome Research Institute .

- This video from City University of New York delves into the basics of what defines science.

- Learn about what makes science science in this book excerpt from Washington State University .

- This resource from the University of Michigan — Flint explains how to design your own scientific study.

Merriam-Webster Dictionary, Scientia. 2022. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/scientia

University of California, Berkeley, "Understanding Science: An Overview." 2022. https://undsci.berkeley.edu/article/0_0_0/intro_01

Highline College, "Scientific method." July 12, 2015. https://people.highline.edu/iglozman/classes/astronotes/scimeth.htm

North Carolina State University, "Science Scripts." https://projects.ncsu.edu/project/bio183de/Black/science/science_scripts.html

University of California, Santa Barbara. "What is an Independent variable?" October 31,2017. http://scienceline.ucsb.edu/getkey.php?key=6045

Encyclopedia Britannica, "Control group." May 14, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/science/control-group

The University of Waikato, "Scientific Hypothesis, Theories and Laws." https://sci.waikato.ac.nz/evolution/Theories.shtml

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Robert Grosseteste. May 3, 2019. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/grosseteste/

Encyclopedia Britannica, "Jonas Salk." October 21, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/ biography /Jonas-Salk

National Human Genome Research Institute, "Phosphate Backbone." https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Phosphate-Backbone

National Human Genome Research Institute, "What is the Human Genome Project?" https://www.genome.gov/human-genome-project/What

Live Science contributor Ashley Hamer updated this article on Jan. 16, 2022.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Tree rings reveal summer 2023 was the hottest in 2 millennia

Aurora photos: Stunning northern lights glisten after biggest geomagnetic storm in 21 years

Jupiter's elusive 5th moon caught crossing the Great Red Spot in new NASA images

Most Popular

- 2 James Webb telescope measures the starlight around the universe's biggest, oldest black holes for 1st time ever

- 3 See stunning reconstruction of ancient Egyptian mummy that languished at an Australian high school for a century

- 4 China creates its largest ever quantum computing chip — and it could be key to building the nation's own 'quantum cloud'

- 5 James Webb telescope detects 1-of-a-kind atmosphere around 'Hell Planet' in distant star system

- 2 Newfound 'glitch' in Einstein's relativity could rewrite the rules of the universe, study suggests

- 3 Sun launches strongest solar flare of current cycle in monster X8.7-class eruption

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- R Soc Open Sci

- v.10(8); 2023 Aug

- PMC10465209

On the scope of scientific hypotheses

William hedley thompson.

1 Department of Applied Information Technology, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

2 Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

3 Department of Pedagogical, Curricular and Professional Studies, Faculty of Education, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

4 Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

Associated Data

This article has no additional data.

Hypotheses are frequently the starting point when undertaking the empirical portion of the scientific process. They state something that the scientific process will attempt to evaluate, corroborate, verify or falsify. Their purpose is to guide the types of data we collect, analyses we conduct, and inferences we would like to make. Over the last decade, metascience has advocated for hypotheses being in preregistrations or registered reports, but how to formulate these hypotheses has received less attention. Here, we argue that hypotheses can vary in specificity along at least three independent dimensions: the relationship, the variables, and the pipeline. Together, these dimensions form the scope of the hypothesis. We demonstrate how narrowing the scope of a hypothesis in any of these three ways reduces the hypothesis space and that this reduction is a type of novelty. Finally, we discuss how this formulation of hypotheses can guide researchers to formulate the appropriate scope for their hypotheses and should aim for neither too broad nor too narrow a scope. This framework can guide hypothesis-makers when formulating their hypotheses by helping clarify what is being tested, chaining results to previous known findings, and demarcating what is explicitly tested in the hypothesis.

1. Introduction

Hypotheses are an important part of the scientific process. However, surprisingly little attention is given to hypothesis-making compared to other skills in the scientist's skillset within current discussions aimed at improving scientific practice. Perhaps this lack of emphasis is because the formulation of the hypothesis is often considered less relevant, as it is ultimately the scientific process that will eventually decide the veracity of the hypothesis. However, there are more hypotheses than scientific studies as selection occurs at various stages: from funder selection and researcher's interests. So which hypotheses are worthwhile to pursue? Which hypotheses are the most effective or pragmatic for extending or enhancing our collective knowledge? We consider the answer to these questions by discussing how broad or narrow a hypothesis can or should be (i.e. its scope).

We begin by considering that the two statements below are both hypotheses and vary in scope:

- H 1 : For every 1 mg decrease of x , y will increase by, on average, 2.5 points.

- H 2 : Changes in x 1 or x 2 correlate with y levels in some way.

Clearly, the specificity of the two hypotheses is very different. H 1 states a precise relationship between two variables ( x and y ), while H 2 specifies a vaguer relationship and does not specify which variables will show the relationship. However, they are both still hypotheses about how x and y relate to each other. This claim of various degrees of the broadness of hypotheses is, in and of itself, not novel. In Epistemetrics, Rescher [ 1 ], while drawing upon the physicist Duhem's work, develops what he calls Duhem's Law. This law considers a trade-off between certainty or precision in statements about physics when evaluating them. Duhem's Law states that narrower hypotheses, such as H 1 above, are more precise but less likely to be evaluated as true than broader ones, such as H 2 above. Similarly, Popper, when discussing theories, describes the reverse relationship between content and probability of a theory being true, i.e. with increased content, there is a decrease in probability and vice versa [ 2 ]. Here we will argue that it is important that both H 1 and H 2 are still valid scientific hypotheses, and their appropriateness depends on certain scientific questions.

The question of hypothesis scope is relevant since there are multiple recent prescriptions to improve science, ranging from topics about preregistrations [ 3 ], registered reports [ 4 ], open science [ 5 ], standardization [ 6 ], generalizability [ 7 ], multiverse analyses [ 8 ], dataset reuse [ 9 ] and general questionable research practices [ 10 ]. Within each of these issues, there are arguments to demarcate between confirmatory and exploratory research or normative prescriptions about how science should be done (e.g. science is ‘bad’ or ‘worse’ if code/data are not open). Despite all these discussions and improvements, much can still be done to improve hypothesis-making. A recent evaluation of preregistered studies in psychology found that over half excluded the preregistered hypotheses [ 11 ]. Further, evaluations of hypotheses in ecology showed that most hypotheses are not explicitly stated [ 12 , 13 ]. Other research has shown that obfuscated hypotheses are more prevalent in retracted research [ 14 ]. There have been recommendations for simpler hypotheses in psychology to avoid misinterpretations and misspecifications [ 15 ]. Finally, several evaluations of preregistration practices have found that a significant proportion of articles do not abide by their stated hypothesis or add additional hypotheses [ 11 , 16 – 18 ]. In sum, while multiple efforts exist to improve scientific practice, our hypothesis-making could improve.

One of our intentions is to provide hypothesis-makers with tools to assist them when making hypotheses. We consider this useful and timely as, with preregistrations becoming more frequent, the hypothesis-making process is now open and explicit . However, preregistrations are difficult to write [ 19 ], and preregistered articles can change or omit hypotheses [ 11 ] or they are vague and certain degrees of freedom hard to control for [ 16 – 18 ]. One suggestion has been to do less confirmatory research [ 7 , 20 ]. While we agree that all research does not need to be confirmatory, we also believe that not all preregistrations of confirmatory work must test narrow hypotheses. We think there is a possible point of confusion that the specificity in preregistrations, where researcher degrees of freedom should be stated, necessitates the requirement that the hypothesis be narrow. Our belief that this confusion is occurring is supported by the study Akker et al . [ 11 ] where they found that 18% of published psychology studies changed their preregistered hypothesis (e.g. its direction), and 60% of studies selectively reported hypotheses in some way. It is along these lines that we feel the framework below can be useful to help formulate appropriate hypotheses to mitigate these identified issues.

We consider this article to be a discussion of the researcher's different choices when formulating hypotheses and to help link hypotheses over time. Here we aim to deconstruct what aspects there are in the hypothesis about their specificity. Throughout this article, we intend to be neutral to many different philosophies of science relating to the scientific method (i.e. how one determines the veracity of a hypothesis). Our idea of neutrality here is that whether a researcher adheres to falsification, verification, pragmatism, or some other philosophy of science, then this framework can be used when formulating hypotheses. 1

The framework this article advocates for is that there are (at least) three dimensions that hypotheses vary along regarding their narrowness and broadness: the selection of relationships, variables, and pipelines. We believe this discussion is fruitful for the current debate regarding normative practices as some positions make, sometimes implicit, commitments about which set of hypotheses the scientific community ought to consider good or permissible. We proceed by outlining a working definition of ‘scientific hypothesis' and then discuss how it relates to theory. Then, we justify how hypotheses can vary along the three dimensions. Using this framework, we then discuss the scopes in relation to appropriate hypothesis-making and an argument about what constitutes a scientifically novel hypothesis. We end the article with practical advice for researchers who wish to use this framework.

2. The scientific hypothesis

In this section, we will describe a functional and descriptive role regarding how scientists use hypotheses. Jeong & Kwon [ 21 ] investigated and summarized the different uses the concept of ‘hypothesis’ had in philosophical and scientific texts. They identified five meanings: assumption, tentative explanation, tentative cause, tentative law, and prediction. Jeong & Kwon [ 21 ] further found that researchers in science and philosophy used all the different definitions of hypotheses, although there was some variance in frequency between fields. Here we see, descriptively , that the way researchers use the word ‘hypothesis’ is diverse and has a wide range in specificity and function. However, whichever meaning a hypothesis has, it aims to be true, adequate, accurate or useful in some way.

Not all hypotheses are ‘scientific hypotheses'. For example, consider the detective trying to solve a crime and hypothesizing about the perpetrator. Such a hypothesis still aims to be true and is a tentative explanation but differs from the scientific hypothesis. The difference is that the researcher, unlike the detective, evaluates the hypothesis with the scientific method and submits the work for evaluation by the scientific community. Thus a scientific hypothesis entails a commitment to evaluate the statement with the scientific process . 2 Additionally, other types of hypotheses can exist. As discussed in more detail below, scientific theories generate not only scientific hypotheses but also contain auxiliary hypotheses. The latter refers to additional assumptions considered to be true and not explicitly evaluated. 3

Next, the scientific hypothesis is generally made antecedent to the evaluation. This does not necessitate that the event (e.g. in archaeology) or the data collection (e.g. with open data reuse) must be collected before the hypothesis is made, but that the evaluation of the hypothesis cannot happen before its formulation. This claim state does deny the utility of exploratory hypothesis testing of post hoc hypotheses (see [ 25 ]). However, previous results and exploration can generate new hypotheses (e.g. via abduction [ 22 , 26 – 28 ], which is the process of creating hypotheses from evidence), which is an important part of science [ 29 – 32 ], but crucially, while these hypotheses are important and can be the conclusion of exploratory work, they have yet to be evaluated (by whichever method of choice). Hence, they still conform to the antecedency requirement. A further way to justify the antecedency is seen in the practice of formulating a post hoc hypothesis, and considering it to have been evaluated is seen as a questionable research practice (known as ‘hypotheses after results are known’ or HARKing [ 33 ]). 4

While there is a varying range of specificity, is the hypothesis a critical part of all scientific work, or is it reserved for some subset of investigations? There are different opinions regarding this. Glass and Hall, for example, argue that the term only refers to falsifiable research, and model-based research uses verification [ 36 ]. However, this opinion does not appear to be the consensus. Osimo and Rumiati argue that any model based on or using data is never wholly free from hypotheses, as hypotheses can, even implicitly, infiltrate the data collection [ 37 ]. For our definition, we will consider hypotheses that can be involved in different forms of scientific evaluation (i.e. not just falsification), but we do not exclude the possibility of hypothesis-free scientific work.

Finally, there is a debate about whether theories or hypotheses should be linguistic or formal [ 38 – 40 ]. Neither side in this debate argues that verbal or formal hypotheses are not possible, but instead, they discuss normative practices. Thus, for our definition, both linguistic and formal hypotheses are considered viable.

Considering the above discussion, let us summarize the scientific process and the scientific hypothesis: a hypothesis guides what type of data are sampled and what analysis will be done. With the new observations, evidence is analysed or quantified in some way (often using inferential statistics) to judge the hypothesis's truth value, utility, credibility, or likelihood. The following working definition captures the above:

- Scientific hypothesis : an implicit or explicit statement that can be verbal or formal. The hypothesis makes a statement about some natural phenomena (via an assumption, explanation, cause, law or prediction). The scientific hypothesis is made antecedent to performing a scientific process where there is a commitment to evaluate it.

For simplicity, we will only use the term ‘hypothesis’ for ‘scientific hypothesis' to refer to the above definition for the rest of the article except when it is necessary to distinguish between other types of hypotheses. Finally, this definition could further be restrained in multiple ways (e.g. only explicit hypotheses are allowed, or assumptions are never hypotheses). However, if the definition is more (or less) restrictive, it has little implication for the argument below.

3. The hypothesis, theory and auxiliary assumptions

While we have a definition of the scientific hypothesis, we have yet to link it with how it relates to scientific theory, where there is frequently some interconnection (i.e. a hypothesis tests a scientific theory). Generally, for this paper, we believe our argument applies regardless of how scientific theory is defined. Further, some research lacks theory, sometimes called convenience or atheoretical studies [ 41 ]. Here a hypothesis can be made without a wider theory—and our framework fits here too. However, since many consider hypotheses to be defined or deducible from scientific theory, there is an important connection between the two. Therefore, we will briefly clarify how hypotheses relate to common formulations of scientific theory.

A scientific theory is generally a set of axioms or statements about some objects, properties and their relations relating to some phenomena. Hypotheses can often be deduced from the theory. Additionally, a theory has boundary conditions. The boundary conditions specify the domain of the theory stating under what conditions it applies (e.g. all things with a central neural system, humans, women, university teachers) [ 42 ]. Boundary conditions of a theory will consequently limit all hypotheses deduced from the theory. For example, with a boundary condition ‘applies to all humans’, then the subsequent hypotheses deduced from the theory are limited to being about humans. While this limitation of the hypothesis by the theory's boundary condition exists, all the considerations about a hypothesis scope detailed below still apply within the boundary conditions. Finally, it is also possible (depending on the definition of scientific theory) for a hypothesis to test the same theory under different boundary conditions. 5

The final consideration relating scientific theory to scientific hypotheses is auxiliary hypotheses. These hypotheses are theories or assumptions that are considered true simultaneously with the theory. Most philosophies of science from Popper's background knowledge [ 24 ], Kuhn's paradigms during normal science [ 44 ], and Laktos' protective belt [ 45 ] all have their own versions of this auxiliary or background information that is required for the hypothesis to test the theory. For example, Meelh [ 46 ] auxiliary theories/assumptions are needed to go from theoretical terms to empirical terms (e.g. neural activity can be inferred from blood oxygenation in fMRI research or reaction time to an indicator of cognition) and auxiliary theories about instruments (e.g. the experimental apparatus works as intended) and more (see also Other approaches to categorizing hypotheses below). As noted in the previous section, there is a difference between these auxiliary hypotheses, regardless of their definition, and the scientific hypothesis defined above. Recall that our definition of the scientific hypothesis included a commitment to evaluate it. There are no such commitments with auxiliary hypotheses, but rather they are assumed to be correct to test the theory adequately. This distinction proves to be important as auxiliary hypotheses are still part of testing a theory but are separate from the hypothesis to be evaluated (discussed in more detail below).

4. The scope of hypotheses

In the scientific hypothesis section, we defined the hypothesis and discussed how it relates back to the theory. In this section, we want to defend two claims about hypotheses:

- (A1) Hypotheses can have different scopes . Some hypotheses are narrower in their formulation, and some are broader.

- (A2) The scope of hypotheses can vary along three dimensions relating to relationship selection , variable selection , and pipeline selection .

A1 may seem obvious, but it is important to establish what is meant by narrower and broader scope. When a hypothesis is very narrow, it is specific. For example, it might be specific about the type of relationship between some variables. In figure 1 , we make four different statements regarding the relationship between x and y . The narrowest hypothesis here states ‘there is a positive linear relationship with a magnitude of 0.5 between x and y ’ ( figure 1 a ), and the broadest hypothesis states ‘there is a relationship between x and y ’ ( figure 1 d ). Note that many other hypotheses are possible that are not included in this example (such as there being no relationship).

Examples of narrow and broad hypotheses between x and y . Circles indicate a set of possible relationships with varying slopes that can pivot or bend.

We see that the narrowest of these hypotheses claims a type of relationship (linear), a direction of the relationship (positive) and a magnitude of the relationship (0.5). As the hypothesis becomes broader, the specific magnitude disappears ( figure 1 b ), the relationship has additional options than just being linear ( figure 1 c ), and finally, the direction of the relationship disappears. Crucially, all the examples in figure 1 can meet the above definition of scientific hypotheses. They are all statements that can be evaluated with the same scientific method. There is a difference between these statements, though— they differ in the scope of the hypothesis . Here we have justified A1.

Within this framework, when we discuss whether a hypothesis is narrower or broader in scope, this is a relation between two hypotheses where one is a subset of the other. This means that if H 1 is narrower than H 2 , and if H 1 is true, then H 2 is also true. This can be seen in figure 1 a–d . Suppose figure 1 a , the narrowest of all the hypotheses, is true. In that case, all the other broader statements are also true (i.e. a linear correlation of 0.5 necessarily entails that there is also a positive linear correlation, a linear correlation, and some relationship). While this property may appear trivial, it entails that it is only possible to directly compare the hypothesis scope between two hypotheses (i.e. their broadness or narrowness) where one is the subset of the other. 6

4.1. Sets, disjunctions and conjunctions of elements

The above restraint defines the scope as relations between sets. This property helps formalize the framework of this article. Below, when we discuss the different dimensions that can impact the scope, these become represented as a set. Each set contains elements. Each element is a permissible situation that allows the hypothesis to be accepted. We denote elements as lower case with italics (e.g. e 1 , e 2 , e 3 ) and sets as bold upper case (e.g. S ). Each of the three different dimensions discussed below will be formalized as sets, while the total number of elements specifies their scope.

Let us reconsider the above restraint about comparing hypotheses as narrower or broader. This can be formally shown if:

- e 1 , e 2 , e 3 are elements of S 1 ; and

- e 1 and e 2 are elements of S 2 ,

then S 2 is narrower than S 1 .

Each element represents specific propositions that, if corroborated, would support the hypothesis. Returning to figure 1 a , b , the following statements apply to both:

- ‘There is a positive linear relationship between x and y with a slope of 0.5’.

Whereas the following two apply to figure 1 b but not figure 1 a :

- ‘There is a positive linear relationship between x and y with a slope of 0.4’ ( figure 1 b ).

- ‘There is a positive linear relationship between x and y with a slope of 0.3’ ( figure 1 b ).

Figure 1 b allows for a considerably larger number of permissible situations (which is obvious as it allows for any positive linear relationship). When formulating the hypothesis in figure 1 b , we do not need to specify every single one of these permissible relationships. We can simply specify all possible positive slopes, which entails the set of permissible elements it includes.

That broader hypotheses have more elements in their sets entails some important properties. When we say S contains the elements e 1 , e 2 , and e 3 , the hypothesis is corroborated if e 1 or e 2 or e 3 is the case. This means that the set requires only one of the elements to be corroborated for the hypothesis to be considered correct (i.e. the positive linear relationship needs to be 0.3 or 0.4 or 0.5). Contrastingly, we will later see cases when conjunctions of elements occur (i.e. both e 1 and e 2 are the case). When a conjunction occurs, in this formulation, the conjunction itself becomes an element in the set (i.e. ‘ e 1 and e 2 ’ is a single element). Figure 2 illustrates how ‘ e 1 and e 2 ’ is narrower than ‘ e 1 ’, and ‘ e 1 ’ is narrower than ‘ e 1 or e 2 ’. 7 This property relating to the conjunction being narrower than individual elements is explained in more detail in the pipeline selection section below.

Scope as sets. Left : four different sets (grey, red, blue and purple) showing different elements which they contain. Right : a list of each colour explaining which set is a subset of the other (thereby being ‘narrower’).

4.2. Relationship selection

We move to A2, which is to show the different dimensions that a hypothesis scope can vary along. We have already seen an example of the first dimension of a hypothesis in figure 1 , the relationship selection . Let R denote the set of all possible configurations of relationships that are permissible for the hypothesis to be considered true. For example, in the narrowest formulation above, there was one allowed relationship for the hypothesis to be true. Consequently, the size of R (denoted | R |) is one. As discussed above, in the second narrowest formulation ( figure 1 b ), R has more possible relationships where it can still be considered true:

- r 1 = ‘a positive linear relationship of 0.1’

- r 2 = ‘a positive linear relationship of 0.2’

- r 3 = ‘a positive linear relationship of 0.3’.

Additionally, even broader hypotheses will be compatible with more types of relationships. In figure 1 c , d , nonlinear and negative relationships are also possible relationships included in R . For this broader statement to be affirmed, more elements are possible to be true. Thus if | R | is greater (i.e. contains more possible configurations for the hypothesis to be true), then the hypothesis is broader. Thus, the scope of relating to the relationship selection is specified by | R |. Finally, if |R H1 | > |R H2 | , then H 1 is broader than H 2 regarding the relationship selection.