How to Write a Poetry Essay: Step-By-Step-Guide

Table of contents

- 1 What Is A Poetry Analysis?

- 2 How to Choose a Poem for Analysis?

- 3.0.1 Introduction

- 3.0.2 Main Body

- 3.0.3 Conclusion

- 4.1 Title of the Poem

- 4.2 Poetry Background

- 4.3 Structure of the Poem

- 4.4 Tone and Intonation of the Poetry

- 4.5 Language Forms and Symbols of the Poetry

- 4.6 Poetic devices

- 4.7 Music of the Poem

- 4.8 Purpose of Poem

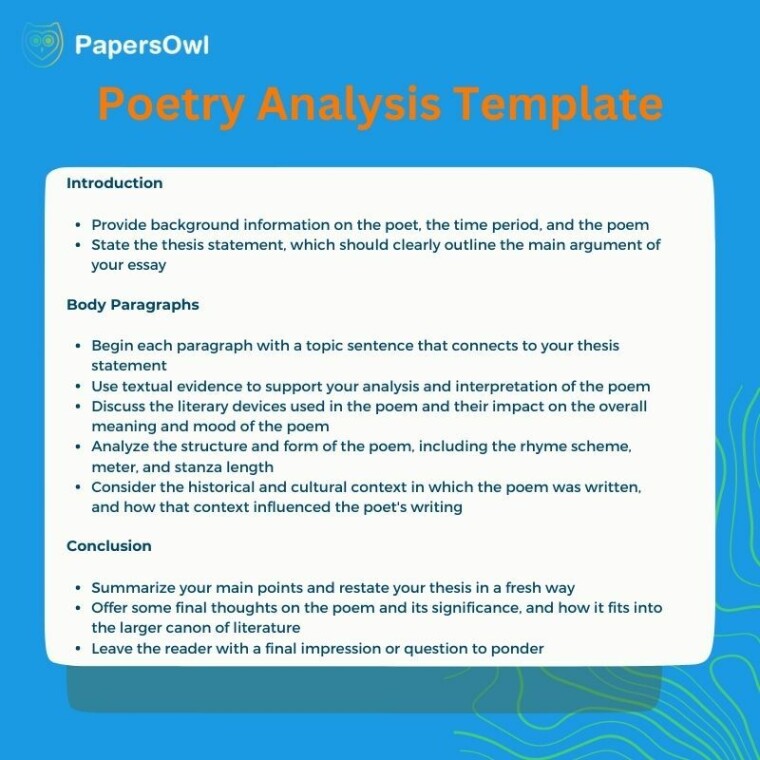

- 5 Poetry Analysis Template

- 6 Example of Poem Analysis

Edgar Allan Poe once said:

“Poetry is the rhythmical creation of beauty in words.”

The reader’s soul enjoys the beauty of the words masterfully expressed by the poet in a few lines. How much meaning is invested in these words, and even more lies behind them? For this reason, poetry is a constant object of scientific interest and the center of literary analysis.

As a university student, especially in literary specialties, you will often come across the need to write a poetry analysis essay. It may seem very difficult when you encounter such an essay for the first time. This is not surprising because even experienced students have difficulty performing such complex studies. This article will point you in the right direction and can be used as a poetry analysis worksheet.

What Is A Poetry Analysis?

Any poetry analysis consists in an in-depth study of the subject of study and the background details in which it is located. Poetry analysis is the process of decomposing a lyrical work into its smallest components for a detailed study of the independent elements. After that, all the data obtained are reassembled to formulate conclusions and write literary analysis . The study of a specific lyric poem also includes the study of the hidden meaning of the poem, the poet’s attitude and main idea, and the expression of individual impressions. After all, the lyrics aim to reach the heart of the reader.

The goal of the poetry analysis is to understand a literary work better. This type of scientific research makes it possible to study entire categories of art on the example of specific works, classify them as certain movements, and find similarities and differences with other poems representing the era.

A poetry analysis essay is a very common type of an essay for university programs, especially in literary and philological areas. Students are often required to have extensive knowledge as well as the ability of in-depth analysis. Such work requires immersion in the context and a high level of concentration.

How to Choose a Poem for Analysis?

You are a really lucky person if you have the opportunity to choose a poem to write a poetry analysis essay independently. After all, any scientific work is moving faster and easier if you are an expert and interested in the field of study. First of all, choose a poet who appeals to you. The piece is not just a set of sentences united by a common meaning. Therefore, it is primarily a reflection of the thoughts and beliefs of the author.

Also, choose a topic that is interesting and close to you. It doesn’t matter if it is an intimate sonnet, a patriotic poem, or a skillful description of nature. The main thing is that it arouses your interest. However, pay attention to the size of the work to make your work easier. The volume should be sufficient to conduct extensive analysis but not too large to meet the requirement for a poem analysis essay.

Well, in the end, your experience and knowledge of the poetry topic are important. Stop choosing the object of study that is within the scope of your competence. In this way, you will share your expert opinion with the public, as well as save yourself from the need for additional data searches required for better understanding.

Poem Analysis Essay Outline

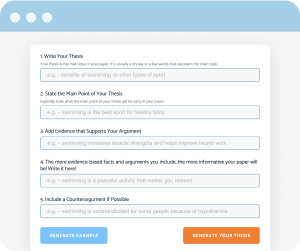

A well-defined structure is a solid framework for your writing. Sometimes our thoughts come quite chaotically, or vice versa, you spend many hours having no idea where to start writing. In both cases, a poem analysis outline will come to your aid. Many students feel that writing an essay plan is a waste of time. However, you should reconsider your views on such a work strategy. And although it will take you time to make a poetry analysis essay outline, it will save you effort later on. While a perfect way out is to ask professionals to write your essays online , let’s still take a look at the key features of creating a paper yourself. Working is much easier and more pleasant when you understand what to start from and what to rely on. Let’s look at the key elements of a poem analysis essay structure.

The essence of a poetry essay outline is to structure and organize your thoughts. You must divide your essay into three main sections: introduction, body, and conclusions. Then list brainstormed ideas that you are going to present in each of these parts.

Introduction

Your essay should begin with an introductory paragraph . The main purpose of this section is to attract the attention of the reader. This will ensure interest in the research. You can also use these paragraphs to provide interesting data from the author of the poem and contextual information that directly relates to your poem but is not a part of the analysis yet.

Another integral part of the poem analysis essay introduction is the strong thesis statement . This technique is used when writing most essays in order to summarize the essence of the paper. The thesis statement opens up your narrative, giving the reader a clear picture of what your work will be about. This element should be short, concise, and self-explanatory.

The central section of a literary analysis essay is going to contain all the studies you’ve carried out. A good idea would be to divide the body into three or four paragraphs, each presenting a new idea. When writing an outline for your essay, determine that in the body part, you will describe:

- The central idea.

- Analysis of poetic techniques used by the poet.

- Your observations considering symbolism.

- Various aspects of the poem.

Make sure to include all of the above, but always mind the coherence of your poem literary analysis.

In the final paragraph , you have to list the conclusions to which your poetry analysis came. This is a paragraph that highlights the key points of the study that are worth paying attention to. Ensure that the information in the conclusion matches your goals set in the introduction. The last few lines of a poem usually contain the perfect information for you to wrap up your paper, giving your readers a ground for further thought.

Tips on How to Analyze a Poem

Now, having general theoretical information about what a poetry analysis essay is, what its components are, and how exactly you can make an outline, we are ready to move on to practical data. Let’s take a closer look at the key principles that you should rely on in the poetry analysis. As you might guess, just reading a poem will not be enough to make a comprehensive analysis. You have to pay attention to the smallest details to catch what other researchers have not noticed before you.

Title of the Poem

And although the poems do not always have a title, if the work you have chosen has a name, then this is a good basis for starting the poetry analysis. The title of the poetic work gives the understanding of what the poet considers to be the key ideas of his verse. In some cases, this element directly reflects the theme and idea of the poem. However, there are also common cases when the poet plays with the name, putting the opposite information into it. Look at the correlation between the title and the content of the poem. This may give you new clues to hidden meanings.

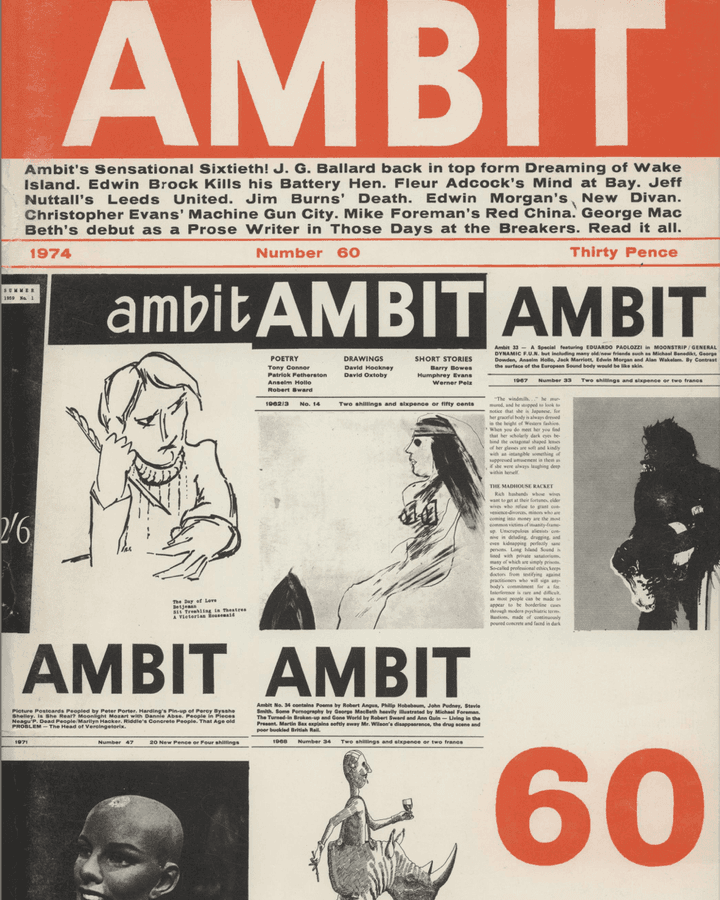

Poetry Background

To fully immerse yourself in the context of the verse, you need to study the prerequisites for its writing. Analyze poetry and pay attention to the period of the author’s life in which the work was written. Study what emotions prevailed in a given time. The background information will help you study the verse itself and what is behind it, which is crucial for a critical analysis essay . What was the poet’s motivation, and what sensations prompted him to express himself specifically in this form? Such in-depth research will give you a broad understanding of the author’s intent and make your poem analysis essay writing more solid.

This fragment of your poem analysis essay study also includes interpretations of all the difficult or little-known words. Perhaps the analyzed poem was written using obsolete words or has poetic terms. For a competent poem analysis, you need to have an enhanced comprehension of the concepts.

Structure of the Poem

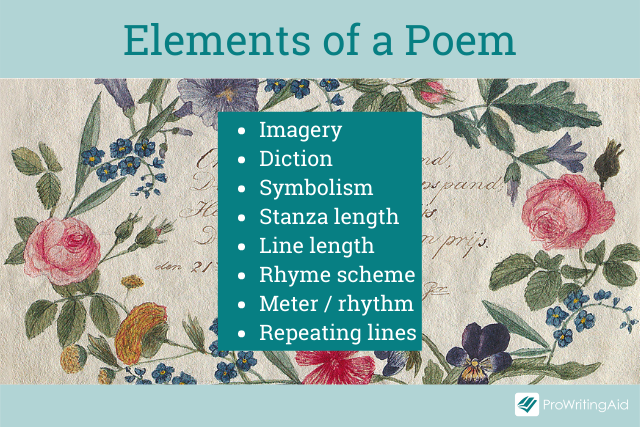

Each lyrical work consists of key elements. The theory identifies four main components of a poem’s structure: stanza, rhyme, meter, and line break. Let’s clarify each of the terms separately so that you know exactly what you are supposed to analyze.

The stanza is also called a verse. This element is a group of lines joined together and separated from other lines by a gap. This component of the poem structure exists for the ordering of the poem and the logical separation of thoughts.

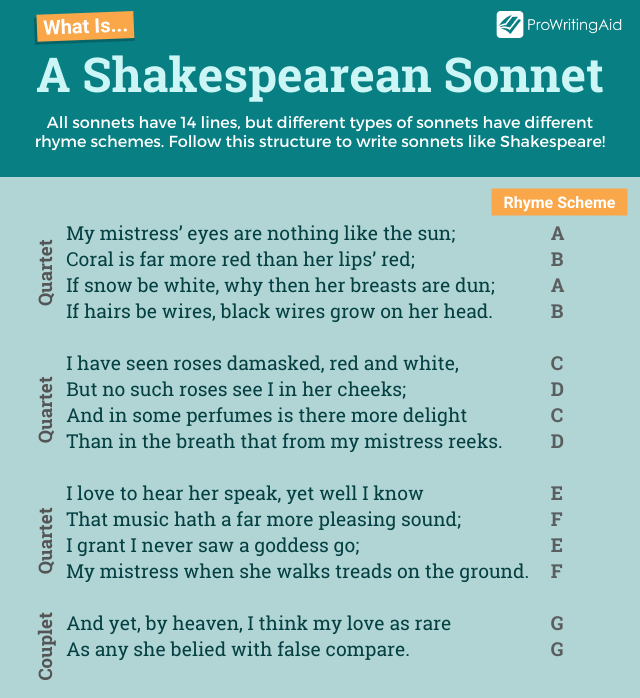

The next crucial element is rhyme. This is a kind of pattern of similar sounds that make up words. There are different types of a rhyme schemes that a particular poem can follow. The difference between the species lies in the spaces between rhyming words. Thus, the most common rhyme scheme in English literature is iambic pentameter.

The meter stands for a composite of stressed and unstressed syllables, following a single scheme throughout the poem. According to the common silabotonic theory, the poem’s rhythm determines the measure of the verse and its poetic form. In other words, this is the rhythm with which lyrical works are written.

Finally, the line break is a technique for distinguishing between different ideas and sentences within the boundaries of one work. Also, the separation serves the reader as a key to understanding the meaning, thanks to the structuring of thoughts. If the ideas went continuously, this would create an extraordinary load on perception, and the reader would struggle to understand the intended message.

Writing an essay about poetry requires careful attention and analysis. Poems, although short, can be intricate and require a thorough understanding to interpret them effectively. Some students may find it challenging to analyze poetry and may consider getting professional help or pay to do an assignment on poetry. Regardless of the approach, it is essential to create a well-structured essay that examines the poem’s meaning and provides relevant examples.

Tone and Intonation of the Poetry

The tone and intonation of the poem could be analyzed based on two variables, the speaker and the recipient. Considering these two sides of the narrative, you can reach a better overview of the analyzed poem.

The first direction is to dig deeper into the author’s ideas by analyzing thematic elements. Pay attention to any information about the poet that can be gleaned from the poem. What mood was the author in when he wrote it, what exactly he felt, and what he wanted to share? What could he be hiding behind his words? Why did the poet choose the exact literary form? Is it possible to trace a life position or ideology through analysis? All of this information will help you get a clue on how to understand a poem.

The analysis of the figure of the recipient is also going to uncover some crucial keys to coherent study. Analyze a poem and determine whether the poem was written for someone specific or not. Find out whether the poet put motivational value into his work or even called readers to action. Is the writer talking to one person or a whole group? Was the poem based on political or social interests?

Language Forms and Symbols of the Poetry

Having sufficiently analyzed the evident elements of the poem, it is time to pay attention to the images and symbols. This is also called the connotative meaning of the work. It can sometimes get challenging to interpret poems, so we will see which other poetic techniques you should consider in the poetry analysis essay.

To convey intricate ideas and display thoughts more vividly, poets often use figurative language. It mostly explains some terms without directly naming them. Lyrical expression works are rich in literary devices such as metaphor, epithet, hyperbole, personification, and others. It may sometimes get really tough to research those poem elements yourself, so keep in mind buying lit essay online. Descriptive language is also one of the techniques used in poems that requires different literary devices in order to make the story as detailed as possible.

To fully understand poetry, it is not enough just to describe its structure. It is necessary to analyze a poem, find the hidden meanings, multiple artistic means, references the poet makes, and the language of writing.

Poetic devices

Poetic devices, such as rhythm, rhyme, and sounds, are used to immerse the audience. The poets often use figurative techniques in various poems, discovering multiple possibilities for the readers to interpret the poem. To discover the composition dedicated to the precise verse, you need to read the poem carefully. Consider studying poetry analysis essay example papers to better understand the concepts. It is a certain kind of reader’s quest aimed at finding the true meaning of the metaphor the poet has hidden in the poem. Each literary device is always there for a reason. Try to figure out its purpose.

Music of the Poem

Many poems formed the basis of the songs. This does not happen by chance because each poem has its own music. Lyrical works have such elements as rhythm and rhyme. They set the pace for reading. Also, sound elements are often hidden in poems. The line break gives a hint about when to take a long pause. Try to pay attention to the arrangement of words. Perhaps this will reveal you a new vision of the analyzed poem.

Purpose of Poem

While you analyze a poem, you are supposed to search for the purpose. Each work has its purpose for writing. Perhaps this is just a process in which the author shares his emotions, or maybe it’s a skillful description of landscapes written under great impressions. Social lyrics illuminate the situation in society and pressing problems. Pay attention to whether the verse contains a call to action or an instructive context. Your task is to study the poem and analyze the motives for its writing. Understanding the general context, and especially the purpose of the poet will make your analysis unique.

Poetry Analysis Template

To make it easier for you to research, we have compiled a template for writing a poetry analysis essay. The best specialists of the our writing service have assembled the main guides that will serve as a layout for your essay. Choose a poem that suits you and analyze it according to this plan.

Introduction:

- The title of the poem or sonnet

- The name of the poet

- The date the poem was first published

- The background information and interesting facts about the poet and the poem

- Identify the structure of the poem, and the main components

- Find out the data about the speaker and recipient

- State the purpose of the poem

- Distinguish the topic and the idea of the verse

Figurative language:

- Study the literary devices

- Search for the hidden meanings

Following these tips, you will write a competitive poem analysis essay. Use these techniques, and you will be able to meet the basic requirements for quality work. However, don’t forget to add personality to your essay. Analyze both the choices of the author of the poem and your own vision. First of all, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Do not limit yourself to dry analysis, add your own vision of the poem. In this way, you will get a balanced essay that will appeal to teachers.

Example of Poem Analysis

Maya Angelou’s “Still I Rise,” is a powerful anthem of strength and resilience that has become an iconic piece of literature. The poem was written in the 1970s during the civil rights movement and was published in Angelou’s collection of poetry, “And Still I Rise,” in 1978. The structure of the poem is unique in that it is not divided into stanzas but is composed of a series of short phrases that are separated by semicolons. This creates a sense of continuity and momentum as the poem moves forward. The lack of stanzas also reflects the speaker’s determination to keep going, regardless of the obstacles she faces. The tone of the poem is confident and defiant, with a strong sense of pride in the speaker’s identity and heritage. The intonation is rhythmic and musical, with a repeated refrain that emphasizes the theme of rising above adversity. The language forms used in the poem are simple and direct. One of the most powerful symbols in the poem is the image of the rising sun… FULL POEM ANALYSIS

Our database is filled with a wide range of poetry essay examples that can help you understand how to analyze and write about poetry. Whether you are a student trying to improve your essay writing skills or a poetry enthusiast looking to explore different perspectives on your favorite poems, our collection of essays can provide valuable insights and inspiration. So take a look around and discover new ways to appreciate and interpret the power of poetry!

Readers also enjoyed

WHY WAIT? PLACE AN ORDER RIGHT NOW!

Just fill out the form, press the button, and have no worries!

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy.

A Full Guide to Writing a Perfect Poem Analysis Essay

01 October, 2020

14 minutes read

Author: Elizabeth Brown

Poem analysis is one of the most complicated essay types. It requires the utmost creativity and dedication. Even those who regularly attend a literary class and have enough experience in poem analysis essay elaboration may face considerable difficulties while dealing with the particular poem. The given article aims to provide the detailed guidelines on how to write a poem analysis, elucidate the main principles of writing the essay of the given type, and share with you the handy tips that will help you get the highest score for your poetry analysis. In addition to developing analysis skills, you would be able to take advantage of the poetry analysis essay example to base your poetry analysis essay on, as well as learn how to find a way out in case you have no motivation and your creative assignment must be presented on time.

What Is a Poetry Analysis Essay?

A poetry analysis essay is a type of creative write-up that implies reviewing a poem from different perspectives by dealing with its structural, artistic, and functional pieces. Since the poetry expresses very complicated feelings that may have different meanings depending on the backgrounds of both author and reader, it would not be enough just to focus on the text of the poem you are going to analyze. Poetry has a lot more complex structure and cannot be considered without its special rhythm, images, as well as implied and obvious sense.

While analyzing the poem, the students need to do in-depth research as to its content, taking into account the effect the poetry has or may have on the readers.

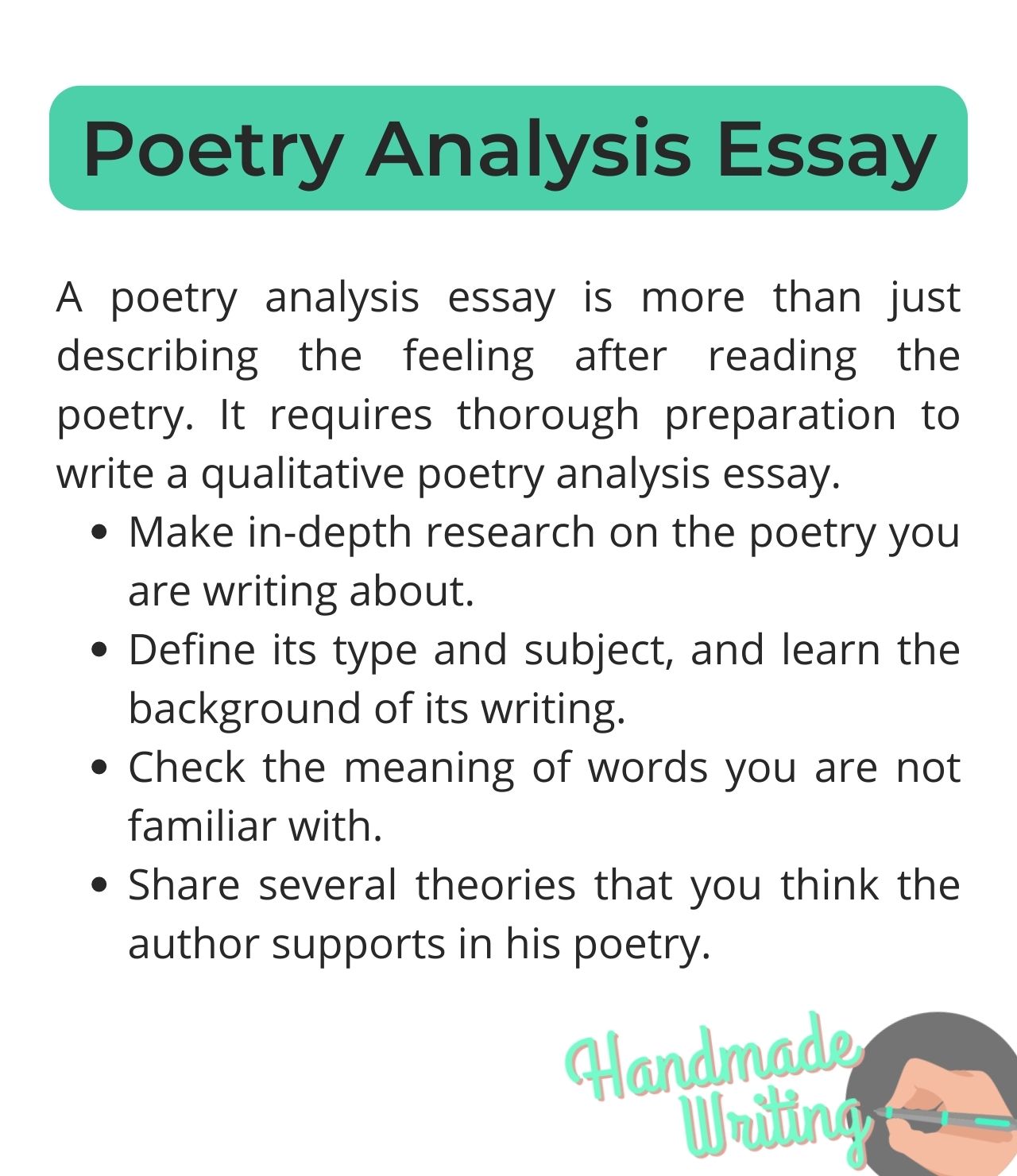

Preparing for the Poetry Analysis Writing

The process of preparation for the poem analysis essay writing is almost as important as writing itself. Without completing these stages, you may be at risk of failing your creative assignment. Learn them carefully to remember once and for good.

Thoroughly read the poem several times

The rereading of the poem assigned for analysis will help to catch its concepts and ideas. You will have a possibility to define the rhythm of the poem, its type, and list the techniques applied by the author.

While identifying the type of the poem, you need to define whether you are dealing with:

- Lyric poem – the one that elucidates feelings, experiences, and the emotional state of the author. It is usually short and doesn’t contain any narration;

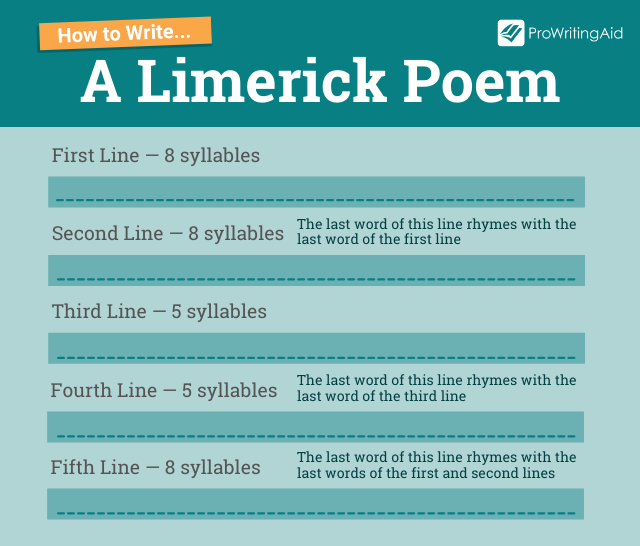

- Limerick – consists of 5 lines, the first, second, and fifth of which rhyme with one another;

- Sonnet – a poem consisting of 14 lines characterized by an iambic pentameter. William Shakespeare wrote sonnets which have made him famous;

- Ode – 10-line poem aimed at praising someone or something;

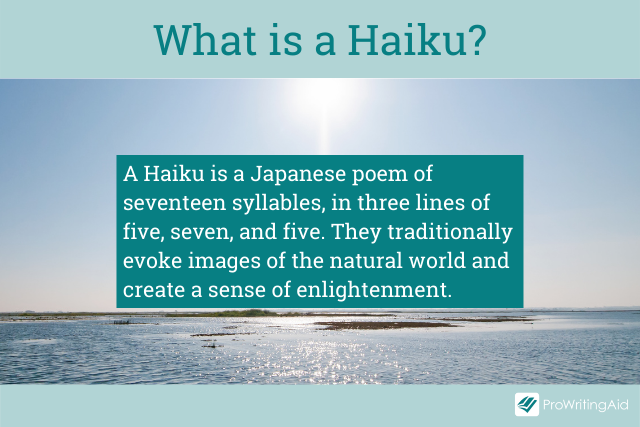

- Haiku – a short 3-line poem originated from Japan. It reflects the deep sense hidden behind the ordinary phenomena and events of the physical world;

- Free-verse – poetry with no rhyme.

The type of the poem usually affects its structure and content, so it is important to be aware of all the recognized kinds to set a proper beginning to your poetry analysis.

Find out more about the poem background

Find as much information as possible about the author of the poem, the cultural background of the period it was written in, preludes to its creation, etc. All these data will help you get a better understanding of the poem’s sense and explain much to you in terms of the concepts the poem contains.

Define a subject matter of the poem

This is one of the most challenging tasks since as a rule, the subject matter of the poem isn’t clearly stated by the poets. They don’t want the readers to know immediately what their piece of writing is about and suggest everyone find something different between the lines.

What is the subject matter? In a nutshell, it is the main idea of the poem. Usually, a poem may have a couple of subjects, that is why it is important to list each of them.

In order to correctly identify the goals of a definite poem, you would need to dive into the in-depth research.

Check the historical background of the poetry. The author might have been inspired to write a poem based on some events that occurred in those times or people he met. The lines you analyze may be generated by his reaction to some epoch events. All this information can be easily found online.

Choose poem theories you will support

In the variety of ideas the poem may convey, it is important to stick to only several most important messages you think the author wanted to share with the readers. Each of the listed ideas must be supported by the corresponding evidence as proof of your opinion.

The poetry analysis essay format allows elaborating on several theses that have the most value and weight. Try to build your writing not only on the pure facts that are obvious from the context but also your emotions and feelings the analyzed lines provoke in you.

How to Choose a Poem to Analyze?

If you are free to choose the piece of writing you will base your poem analysis essay on, it is better to select the one you are already familiar with. This may be your favorite poem or one that you have read and analyzed before. In case you face difficulties choosing the subject area of a particular poem, then the best way will be to focus on the idea you feel most confident about. In such a way, you would be able to elaborate on the topic and describe it more precisely.

Now, when you are familiar with the notion of the poetry analysis essay, it’s high time to proceed to poem analysis essay outline. Follow the steps mentioned below to ensure a brilliant structure to your creative assignment.

Best Poem Analysis Essay Topics

- Mother To Son Poem Analysis

- We Real Cool Poem Analysis

- Invictus Poem Analysis

- Richard Cory Poem Analysis

- Ozymandias Poem Analysis

- Barbie Doll Poem Analysis

- Caged Bird Poem Analysis

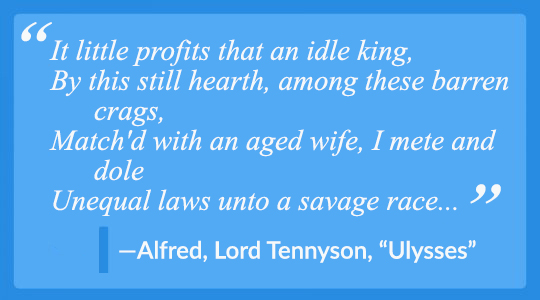

- Ulysses Poem Analysis

- Dover Beach Poem Analysis

- Annabelle Lee Poem Analysis

- Daddy Poem Analysis

- The Raven Poem Analysis

- The Second Coming Poem Analysis

- Still I Rise Poem Analysis

- If Poem Analysis

- Fire And Ice Poem Analysis

- My Papa’S Waltz Poem Analysis

- Harlem Poem Analysis

- Kubla Khan Poem Analysis

- I Too Poem Analysis

- The Juggler Poem Analysis

- The Fish Poem Analysis

- Jabberwocky Poem Analysis

- Charge Of The Light Brigade Poem Analysis

- The Road Not Taken Poem Analysis

- Landscape With The Fall Of Icarus Poem Analysis

- The History Teacher Poem Analysis

- One Art Poem Analysis

- The Wanderer Poem Analysis

- We Wear The Mask Poem Analysis

- There Will Come Soft Rains Poem Analysis

- Digging Poem Analysis

- The Highwayman Poem Analysis

- The Tyger Poem Analysis

- London Poem Analysis

- Sympathy Poem Analysis

- I Am Joaquin Poem Analysis

- This Is Just To Say Poem Analysis

- Sex Without Love Poem Analysis

- Strange Fruit Poem Analysis

- Dulce Et Decorum Est Poem Analysis

- Emily Dickinson Poem Analysis

- The Flea Poem Analysis

- The Lamb Poem Analysis

- Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night Poem Analysis

- My Last Duchess Poetry Analysis

Poem Analysis Essay Outline

As has already been stated, a poetry analysis essay is considered one of the most challenging tasks for the students. Despite the difficulties you may face while dealing with it, the structure of the given type of essay is quite simple. It consists of the introduction, body paragraphs, and the conclusion. In order to get a better understanding of the poem analysis essay structure, check the brief guidelines below.

Introduction

This will be the first section of your essay. The main purpose of the introductory paragraph is to give a reader an idea of what the essay is about and what theses it conveys. The introduction should start with the title of the essay and end with the thesis statement.

The main goal of the introduction is to make readers feel intrigued about the whole concept of the essay and serve as a hook to grab their attention. Include some interesting information about the author, the historical background of the poem, some poem trivia, etc. There is no need to make the introduction too extensive. On the contrary, it should be brief and logical.

Body Paragraphs

The body section should form the main part of poetry analysis. Make sure you have determined a clear focus for your analysis and are ready to elaborate on the main message and meaning of the poem. Mention the tone of the poetry, its speaker, try to describe the recipient of the poem’s idea. Don’t forget to identify the poetic devices and language the author uses to reach the main goals. Describe the imagery and symbolism of the poem, its sound and rhythm.

Try not to stick to too many ideas in your body section, since it may make your essay difficult to understand and too chaotic to perceive. Generalization, however, is also not welcomed. Try to be specific in the description of your perspective.

Make sure the transitions between your paragraphs are smooth and logical to make your essay flow coherent and easy to catch.

In a nutshell, the essay conclusion is a paraphrased thesis statement. Mention it again but in different words to remind the readers of the main purpose of your essay. Sum up the key claims and stress the most important information. The conclusion cannot contain any new ideas and should be used to create a strong impact on the reader. This is your last chance to share your opinion with the audience and convince them your essay is worth readers’ attention.

Problems with writing Your Poem Analysis Essay? Try our Essay Writer Service!

Poem Analysis Essay Examples

A good poem analysis essay example may serve as a real magic wand to your creative assignment. You may take a look at the structure the other essay authors have used, follow their tone, and get a great share of inspiration and motivation.

Check several poetry analysis essay examples that may be of great assistance:

- https://study.com/academy/lesson/poetry-analysis-essay-example-for-english-literature.html

- https://www.slideshare.net/mariefincher/poetry-analysis-essay

Writing Tips for a Poetry Analysis Essay

If you read carefully all the instructions on how to write a poetry analysis essay provided above, you have probably realized that this is not the easiest assignment on Earth. However, you cannot fail and should try your best to present a brilliant essay to get the highest score. To make your life even easier, check these handy tips on how to analysis poetry with a few little steps.

- In case you have a chance to choose a poem for analysis by yourself, try to focus on one you are familiar with, you are interested in, or your favorite one. The writing process will be smooth and easy in case you are working on the task you truly enjoy.

- Before you proceed to the analysis itself, read the poem out loud to your colleague or just to yourself. It will help you find out some hidden details and senses that may result in new ideas.

- Always check the meaning of words you don’t know. Poetry is quite a tricky phenomenon where a single word or phrase can completely change the meaning of the whole piece.

- Bother to double check if the conclusion of your essay is based on a single idea and is logically linked to the main body. Such an approach will demonstrate your certain focus and clearly elucidate your views.

- Read between the lines. Poetry is about senses and emotions – it rarely contains one clearly stated subject matter. Describe the hidden meanings and mention the feelings this has provoked in you. Try to elaborate a full picture that would be based on what is said and what is meant.

Write a Poetry Analysis Essay with HandmadeWriting

You may have hundreds of reasons why you can’t write a brilliant poem analysis essay. In addition to the fact that it is one of the most complicated creative assignments, you can have some personal issues. It can be anything from lots of homework, a part-time job, personal problems, lack of time, or just the absence of motivation. In any case, your main task is not to let all these factors influence your reputation and grades. A perfect way out may be asking the real pros of essay writing for professional help.

There are a lot of benefits why you should refer to the professional writing agencies in case you are not in the mood for elaborating your poetry analysis essay. We will only state the most important ones:

- You can be 100% sure your poem analysis essay will be completed brilliantly. All the research processes, outlines, structuring, editing, and proofreading will be performed instead of you.

- You will get an absolutely unique plagiarism-free piece of writing that deserves the highest score.

- All the authors are extremely creative, talented, and simply in love with poetry. Just tell them what poetry you would like to build your analysis on and enjoy a smooth essay with the logical structure and amazing content.

- Formatting will be done professionally and without any effort from your side. No need to waste your time on such a boring activity.

As you see, there are a lot of advantages to ordering your poetry analysis essay from HandmadeWriting . Having such a perfect essay example now will contribute to your inspiration and professional growth in future.

A life lesson in Romeo and Juliet taught by death

Due to human nature, we draw conclusions only when life gives us a lesson since the experience of others is not so effective and powerful. Therefore, when analyzing and sorting out common problems we face, we may trace a parallel with well-known book characters or real historical figures. Moreover, we often compare our situations with […]

Ethical Research Paper Topics

Writing a research paper on ethics is not an easy task, especially if you do not possess excellent writing skills and do not like to contemplate controversial questions. But an ethics course is obligatory in all higher education institutions, and students have to look for a way out and be creative. When you find an […]

Art Research Paper Topics

Students obtaining degrees in fine art and art & design programs most commonly need to write a paper on art topics. However, this subject is becoming more popular in educational institutions for expanding students’ horizons. Thus, both groups of receivers of education: those who are into arts and those who only get acquainted with art […]

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

5 Tips for Poetry Writing: How to Get Started Writing Poems

Hannah Yang

Poetry is a daunting art form to break into.

There are technically no rules for how to write a poem , but despite that—or perhaps because of it—learning how to write a successful poem might feel more difficult than learning how to write a successful essay or story.

There are many reasons to try your hand at poetry, even if you’re primarily a prose writer. Here are just a few:

- Practice writing stronger descriptions and imagery

- Unlock a new side of your creative writing practice

- Learn how to wield language in a more nuanced way

Learning how to write poetry may seem intimidating, but it doesn’t have to be.

In this article, we’ll cover five of our favorite tips to get started writing poetry.

How Do You Start Writing Poetry?

How do you write a poem from a new perspective, how do you write a meaningful poem, how do you write a poem about a theme, what are some different types of poetry, tip 1: focus on concrete imagery.

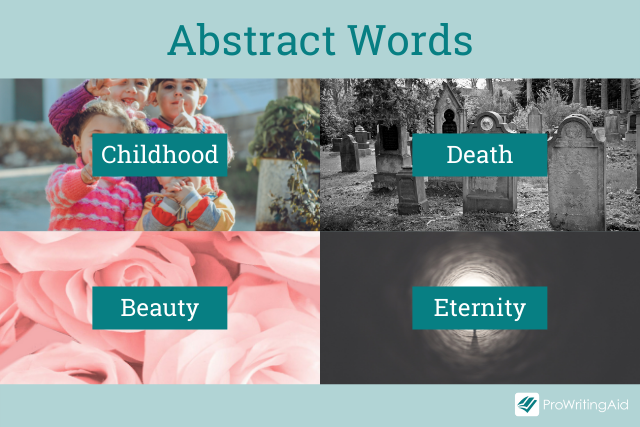

One of the best ways to start writing poetry is to use concrete images that appeal to the five senses.

The idea of starting with the specific might feel counterintuitive, because many people think of poetry as a way to describe abstract ideas, such as death, joy, or sorrow.

It certainly can be. But each of these concepts has been written about extensively before. Try sitting down and writing an original poem about joy—it’s hard to find something new to say about it.

If you write about a specific experience you’ve had that made you feel joy, that will almost certainly be unique, because nobody has lived the same experiences you have.

That’s what makes concrete imagery so powerful in poetry.

A concrete image is a detail that has a basis in something real or tangible. It could be the texture of your daughter’s hair as you braid it in the morning, or the smell of a food that reminds you of home.

The more specific the image is, the more vivid and effective the poem will become.

Concrete imagery: Example

Harlem by Langston Hughes

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun? Or fester like a sore— And then run? Does it stink like rotten meat? Or crust and sugar over— like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

Notice how Langston Hughes doesn’t directly write about dreams, except for the very first line. After the first line, he uses concrete images that are very specific and appeal to the five senses: “dry up like a raisin in the sun,” “stink like rotten meat,” “sags like a heavy load.”

He conveys a deeper message about an abstract concept—dreams—using these specific, tangible images.

Concrete Imagery: Exercise

Examine your surroundings. Describe what you see, hear, feel, taste, and smell.

Through these concrete images, try to evoke a specific feeling (e.g., nostalgia, boredom, happiness) without ever naming that feeling in the poem.

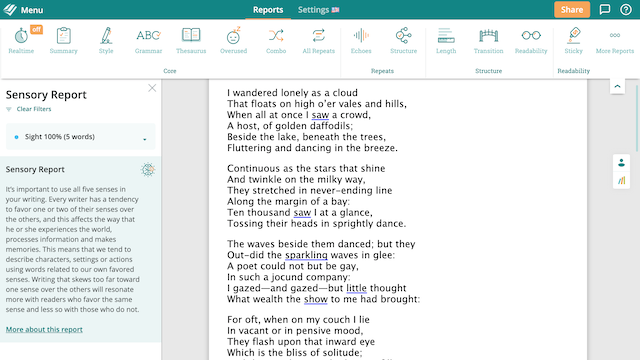

Once you've finished writing, you can use ProWritingAid’s Sensory Check to see which of the five senses you've used the most in your imagery. Most writers favor one or two senses, like in the example below, which can resonate with some readers but alienate others.

Sign up for a free ProWritingAid account to try the Sensory Check.

Bonus Tip: Start with a free verse poem, which is a poem with no set format or rhyme scheme. You can punctuate it the same way you would punctuate normal prose. Free verse is a great option for beginners, because it lets you write freely without limitations.

Tip 2: Play with Perspective

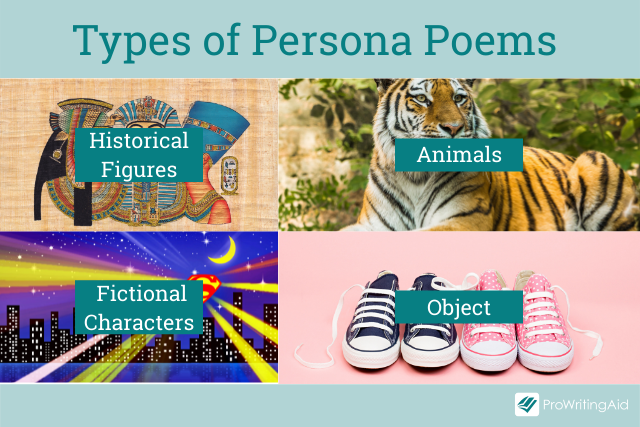

A persona poem is a poem told in the first-person POV (point of view) from the perspective of anything or anyone. This could include a famous person, a figure from mythology, or even an inanimate object.

The word persona comes from the Latin word for mask . When you write a persona poem, it’s like you’re putting on a mask to see the world through a new lens.

If you’re a new poet and you haven’t found your own voice yet, a persona poem is a great way to experiment with a unique style.

Some persona poems are narrative poems, which tell a story from a specific point of view. Others are lyric poems, which focus more on the style and sound of the poem instead of telling a story.

You can write from the perspective of a pop star, a politician, or a figure from fable or myth. You can try to imagine what it feels like to be a pair of jeans or a lawn mower or a fountain pen. There are no limits except your own creativity.

Play with Perspective: Example

Anne Hathaway by Carol Ann Duffy

Item I gyve unto my wief my second best bed … (from Shakespeare’s will)

The bed we loved in was a spinning world of forests, castles, torchlight, cliff-tops, seas where he would dive for pearls. My lover’s words were shooting stars which fell to earth as kisses on these lips; my body now a softer rhyme to his, now echo, assonance; his touch a verb dancing in the centre of a noun. Some nights I dreamed he’d written me, the bed a page beneath his writer’s hands. Romance and drama played by touch, by scent, by taste. In the other bed, the best, our guests dozed on, dribbling their prose. My living laughing love— I hold him in the casket of my widow’s head as he held me upon that next best bed.

In this poem, Carol Ann Duffy writes from the perspective of Anne Hathaway, the wife of William Shakespeare.

She imagines what the wife of this famous literary figure might think and feel, with lines like “Some nights I dreamed he’d written me.”

The poem isn’t written in Shakespearean English, but it uses diction and vocabulary that’s more old-fashioned than the English we speak today, to evoke the feeling of Shakespeare’s time period.

Play with Perspective: Exercise

Write a persona poem from the perspective of a fictional character out of a book or movie. You can tell an important story from their life, or simply try to capture the feeling of being in their head for a moment.

If this character lives in a different time period or speaks in a specific dialect, try to capture that in the poem’s voice.

Tip 3: Write from Life

The best poems are the ones that feel authentic and come from a place of truth.

Brainstorm your own personal experiences. Are there any stories from your life that evoke strong feelings for you? How can you tell that story through a poem?

Try to avoid clichés here. If you want to write about a universal experience or feeling, try to find an entry point into that feeling that’s unique to your life.

Maybe your first hobby was associated with a specific pair of shoes. Maybe your first encounter with shame came from breaking a specific promise to your grandfather. Any of these details could be the launching point for a poem.

Write from Life: Example

Discord in Childhood By D.H. Lawrence

Outside the house an ash-tree hung its terrible whips, And at night when the wind arose, the lash of the tree Shrieked and slashed the wind, as a ship’s Weird rigging in a storm shrieks hideously.

Within the house two voices arose in anger, a slender lash Whistling delirious rage, and the dreadful sound Of a thick lash booming and bruising, until it drowned The other voice in a silence of blood, ’neath the noise of the ash.

Here, D.H. Lawrence writes about the suffering he endured as a child listening to his parents arguing. He channels his own memories and experiences to create a profoundly relatable piece.

Write from Life: Exercise

Go to your phone’s camera roll, or a physical photo album, and find a photo from your life that speaks to you. Write a poem inspired by that photo.

What does that part of your life mean to you? What were your thoughts and feelings at that point in your life?

Tip 4: Save the Theme for the End

In a poem, the last line is often the most important. These are the words that echo in your reader’s head after they’re done reading.

Many poems will tell a story or depict a series of images, allowing you to draw your own conclusions about what it’s trying to say, and then conclude with the takeaway at the very end. Think of it like a fable you might tell a child—often, the moral of the story comes at the end.

In sonnets it’s a common trend for the final couplet to summarize the theme of the whole poem.

Save the Theme: Example

Resumé by Dorothy Parker

Razors pain you; Rivers are damp; Acids stain you; And drugs cause cramp. Guns aren’t lawful; Nooses give; Gas smells awful; You might as well live.

Here, Dorothy Parker doesn’t make the poem’s meaning clear until the very last line: “You might as well live.” The poem feels fun, almost like a song, and its true meaning doesn’t become obvious until after you’ve finished reading the poem.

Save the Theme: Exercise

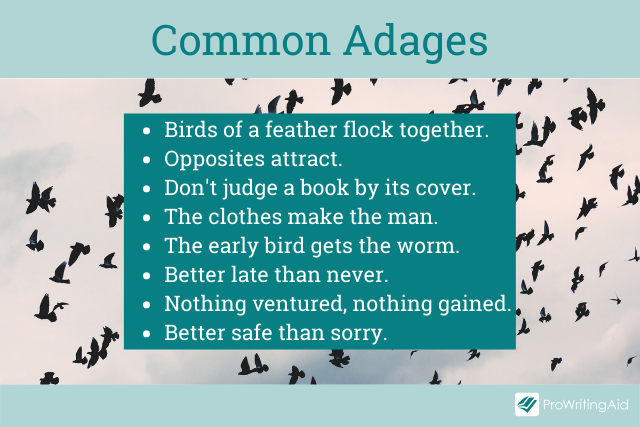

Pick your favorite proverb or adage, such as “Actions speak louder than words.” Write a poem that uses that proverb or adage as the closing line.

Until the closing line, don’t comment on the deeper meaning in the rest of the poem—instead, tell a story that builds up to that theme.

Tip 5: Try a Poetic Form

Up until now, we’ve been writing in blank verse because it’s the most freeing. Sometimes, though, adding limitations can spark creativity too.

You can use a traditional poetic form to create the structure and shape of your poem.

If you have a limited number of lines to use, you’ll concentrate more on being concise and focused. Great poetry is minimalistic—no word is unnecessary. Using a form is a way to practice paring back to the words you absolutely need, and to start thinking about sound and rhyme.

The rules of a poetic form are never set in stone. It’s okay to experiment, and to pick and choose which rules you want to follow. If you want to use a form’s rhyme scheme but ignore its syllable count, for example, that’s perfectly fine.

Let’s look at some examples of poetic forms you can try, and the benefits of each one.

The haiku is a form of Japanese poetry made of three short, unrhymed lines. Traditionally, the first line contains 5 syllables, the second line contains 7 syllables, and the last contains 5 syllables.

Because each haiku must be incredibly concise, this form is a great way to practice economy of language and to learn how to convey a lot with a little. Even more so than with most other poetic forms, you have to think about each word and whether or not it pulls its weight in the poem as a whole.

The Old Pond by Matsuo Bashō

An old silent pond A frog jumps into the pond— Splash! Silence again.

The limerick is a 5-line poem with a sing-songy rhyme scheme and syllable count.

Limericks tend to be humorous and witty, so if you’re usually a comedic writer, they can be a great form for learning how to write poetry. You can treat the poem as a joke that builds up to a punchline.

Untitled Limerick by Edward Lear

There was an Old Man with a beard Who said, "It is just as I feared! Two Owls and a Hen, Four Larks and a Wren, Have all built their nests in my beard!"

The sonnet is a 14-line poetic form, invented in Italy in the 13th century.

There are multiple types of sonnet. One of the most well-known forms is the Shakespearean sonnet, which is divided into three quatrains (4-line stanzas) and one couplet (2-line stanza).

Almost every professional poet has tried a sonnet at some point, from classical poets such as William Shakespeare , John Milton , and John Donne , as well as contemporary poets such as Kim Addonizio , R.S. Gwynn , and Cathy Park Hong .

Sonnets are great for practicing more advanced poetry. Their form forces you to think about rhyme and meter.

Sonnet 116 by William Shakespeare

Let me not to the marriage of true minds Admit impediments. Love is not love Which alters when it alteration finds, Or bends with the remover to remove. O no, it is an ever fixed mark That looks on tempests and is never shaken; It is the star to every wand’ring barque, Whose worth’s unknown although his height be taken. Love’s not time’s fool, though rosy lips and cheeks Within his bending sickle’s compass come; Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks, But bears it out even to the edge of doom. If this be error and upon me proved, I never writ, nor no man ever loved.

The villanelle is a 19-line poem with two lines that recur over and over throughout the poem.

The word “villanelle” comes from the Italian villanella , meaning rustic song or dance, because the two lines that are repeated resemble the chorus of a folk song. Using this form helps you to think about the sound and musicality of your writing.

Mad Girl’s Love Song by Sylvia Plath

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead; I lift my lids and all is born again. (I think I made you up inside my head.)

The stars go waltzing out in blue and red, And arbitrary blackness gallops in: I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.

I dreamed that you bewitched me into bed And sung me moon-struck, kissed me quite insane. (I think I made you up inside my head.)

God topples from the sky, hell’s fires fade: Exit seraphim and Satan’s men: I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.

I fancied you’d return the way you said, But I grow old and I forget your name. (I think I made you up inside my head.)

I should have loved a thunderbird instead; At least when spring comes they roar back again. I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead. (I think I made you up inside my head.)

Try a Poetic Form: Exercise

Pick your favorite poetic form (sonnet, limerick, haiku, or villanelle) and try writing a poem in that structure.

Remember that you don’t have to follow all the rules—pick the ones that spark your imagination, and ignore the ones that don’t.

These are our five favorite tips to get started writing poems. Feel free to try each of them, or to mix and match them to create something entirely new.

Have you tried any of these poetry methods before? Which ones are your favorites? Let us know in the comments.

Take your writing to the next level:

20 Editing Tips from Professional Writers

Whether you are writing a novel, essay, article, or email, good writing is an essential part of communicating your ideas., this guide contains the 20 most important writing tips and techniques from a wide range of professional writers..

Write like a bestselling author

Love writing? ProWritingAid will help you improve the style, strength, and clarity of your stories.

Hannah Yang is a speculative fiction writer who writes about all things strange and surreal. Her work has appeared in Analog Science Fiction, Apex Magazine, The Dark, and elsewhere, and two of her stories have been finalists for the Locus Award. Her favorite hobbies include watercolor painting, playing guitar, and rock climbing. You can follow her work on hannahyang.com, or subscribe to her newsletter for publication updates.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

- Writing & Editing

How to Write a Poem: Everything You’ll Need to Know

Poetry is a thought-provoking art form to get started in. Although there aren't any formal guidelines for writing poetry, learning how to do so may seem more challenging than learning how to produce a good essay or short story.

Poetry is an excellent literary genre you should explore. It's not only a fantastic way to develop your writing skills, but it's also a fantastic field in which to develop a career. But you should understand a few basics about poetry before you even consider starting. Before you even think of taking up poetry though, you should know a few things about how to write poetry.

What is a poem?

It is a written piece that is arranged according to its beauty, rhyme, and sound. They are meant to express a specific idea, emotion, or experience.

It is one of the oldest writing forms in human history. Various cultures have their own types of poetry, and poems are still relevant to this day. Some of the oldest forms of poetry are the Epic of Gilgamesh, which is around 4,000 years old.

What is the purpose of a poem?

There is really no set purpose for writing a poem. Some people write a poem to tell a story, while others do so to express a feeling. Overall, the main purpose of writing poetry is all about artistry, and conveying one’s own perceptions on life.

What are the different types of poem?

Throughout the centuries, poetry has evolved a great deal. Poems have been around in various forms for thousands of years, and they have evolved according to the culture and the times. Here are some of the types of poetry that you should try.

This type of poetry is considered one of the oldest in the world. One of the oldest poems in history, The Epic of Gilgamesh is an epic. It is a very lengthy poem, and is written in a more formal style. It usually features a hero or heroine, and recounts feats of strength and bravery. Here is an excerpt from an epic.

This dog won’t hunt. This horse won’t jump. You get the general drift. However, he keeps on trying, but the fire won’t burn, the kindling is wet, and the faint glow of the ember is weak and dying. He has no other choice then but to let It go and take a nap on the ground there, lying Next to her—for whom Dame Fortune has more Woes and tribulations yet in store.

- Orlando Furioso by Ludovico Ariosto

This kind of poetry is of Grecian origin, and is considered one of the oldest in the world. Ode is derived from the Grecian word ‘aiedein’ which means ‘chant or sing’. This was usually in praise of someone, event or even an object. The poetry is accompanied by musical instruments.

Happy the man, whose wish and care A few paternal acres bound Content to breathe his native air In his own ground.

- Ode on Solitude by Alexander Pope

The free verse format of poetry is relatively new and is by far the freest of all the poetry forms. Thus the name. Its main characteristic is that the verses don’t have to rhyme, and there is no limit to how many lines or stanzas that you could write.

I celebrate myself, and sing myself, And what I assume you shall assume, For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you. I loafe and invite my soul, I lean and loafe at my ease observing a spear of summer grass…

- Song of Myself by Walt Whitman

This poetic style is centered on only one topic, which is death. It is written for a person who has passed away and often has melancholic themes. However, you could also give it an optimistic twist if you want.

Black milk of dawn we drink you at night we drink you mornings and noontime we drink you evenings we drink and we drink A man lives in the house he plays with the snakes he writes he writes when it turns dark to Deutschland your golden hair Margarete Your ashen hair Shulamit we dig a grave in the air there one lies at ease

- Fugue of Death by Paul Celan

Rhymed Poetry

As the name implies, this type of poetry is meant to rhyme. The poem should contain rhyming vowel sounds at specific moments. This rhyme scheme is a constant in most poems, and has been in use for centuries.

Out of the night that covers me, Black as the pit from pole to pole, I thank whatever gods may be For my unconquerable soul.

- Invictus by William Ernest Henley

A very old poetry form, haiku, originated in Japan in the 1600’s. It has gained a great deal of popularity over the years and is unique due to its short but potent format. It is limited to three lines. The first and third lines must have five syllables, and the second one has seven. They don’t have to rhyme, but must convey a specific emotion.

A world of dew, And within every dewdrop A world of struggle.

- A World of Dew by Kobayashi Issa

What are the elements of poetry?

Before you start the poetry writing process, it is important that you know what makes up a poem. Here are the five elements of poetry to get you started.

The meter is the basic rhythmic structure of the lines within your poem. The meter is usually made up two components. These are the exact number of syllables, and the overall pattern being emphasized on those syllables.

The rhyme within a poem occurs when the final or even more syllables match. These must occur within separate words. The rhyme in a poem usually occurs when the last two words in a verse rhyme with one another.

The term verse is often described as a single metrical line in a poem. While it could represent a single line, it could also represent the entire poem itself.

This is often described as the rhyming pattern contained within a poem. The composition of the scheme may contain words that rhyme within the stanza, or in alternating lines, or even in couplets.

The stanza is often described as a group of lines within the poem, and they could follow a regular rhyme and metrical scheme. They are mostly separated by blank spaces or indentations. Stanzas are meant to organize and give shape to a poem.

What are the rules of creating good poetry?

As an aspiring poet, there is really no set rule on how you should do your writing sessions. However, it is important that you should at least have a strategy on how to approach the poetry writing session, and how to get the right inspiration for your poetry writing. Here are some easy to follow rules to follow as a newbie poet.

• Read poetry

Before you start writing poetry, it is important that you are as well-read as possible. No matter how good you are at writing, if you have never really read or heard a poem before, then there is no way you’ll gain proficiency from it.

Take the time to check on the greats such as Pablo Neruda, Oscar Wilde, Sylvia Plath and so many other poets. The more content you read, the better you will be as a poet.

• Start slow

If you just started out as a poet, you should start slow. You could try your hand at poetry writing, but you should not really rush yourself to create great poetry right away. Remember that every writer has to start somewhere. So take your time, and just keep practicing.

• Choose different concepts

When it comes to writing poetry, it is a good idea to write about different concepts. The more concepts you write about, the more multi-faceted your poetry will be. Don’t limit yourself to just a few concepts. You will only limit your growth as a poet.

• Try out different poetry styles

There are many poetry styles, and you should try your hand in all of them. This does not mean that you should build your entire poetry career on them. However, you should at least try them out at least once. You will not only learn more as a poet, you may even expand your repertoire as a poet as well.

• Read out your work

As you write your poems, you should make sure to read them aloud as well. Remember that your poem has to rhyme and sound pleasant to the ear. The poem may sound good on paper, but it sounds awkward when read out. As a rule, you should read out your work during your writing sessions, and make the necessary modifications.

• Make storytelling a key goal

When you write a poem, storytelling must be a key goal. Remember that there should be a sense of cohesion in your writing. As a rule, you should try to tell a story whenever you write a poem. This will make your poems more immersive.

• Reach out to other poets

A great way to further improve your poetry is to reach out to other poets. As a new poet, you may not know the finer points of poetry. Even if you know the basics of poetry writing, you still have a lot to learn. By reaching out to other poets, you will be able to hone your poetry skills more effectively.

• Stay away from clichés

Clichés had become common in the poetry writing scene at the time. Clichés are concepts that have been overused to the extent that readers have grown tired of them. If you want to make your work as original as possible, it is important that you identify these common poetic clichés and never use them.

• Use the five senses

As you write your poem, it is important that you engage all your reader’s senses. This will make your work feel more immersive. When you write your poetry, try to engage all five senses, which are sight, taste, sound, touch, and smell.

• Utilize various writing tools

As you write a poem, you should be as ready as possible. Remember that you will be fully engaged during your writing sessions, so you should make sure that you have the right writing tools on hand.

If you prefer a handwritten approach, you could use a pen and notebook. This does have a more elegant and traditional feel. However, there is nothing wrong with using a tablet or laptop during your writing sessions.

You should also have a dictionary and thesaurus at the ready. You could even download writing software on your phone, tablet, or computer. These apps usually have spell-checks and even a built-in dictionary. This will make the poetry writing process so much easier.

• Have your work looked through

While having your poetry looked through may seem daunting, it is important that you have fellow poets look through it.

Remember that your ultimate goal is to have the public read your work, so it is best if fellow poets go through it. They will be able to point out your poems’s good and bad points and allow you to make the necessary changes.

• Write as much poetry as possible

If you want to be a true poet, it is important that you make poetry a part of your life. You won’t be able to become skilled at poetry overnight. As a rule, you should make poetry writing a habit. Don’t go into poetry in a half-hearted manner. Embrace the poet’s life with a passion, and write poetry every chance you get.

How to write a poem in 7 easy steps

Now that you have a strategy on how to approach the poetry writing process, it is now time to write a poem of your very own. Here are some quick and easy steps that you could follow.

1. Choose a fitting concept

Before you start writing a poem, it is important that you choose a concept. This could be practically anything under the sun. However, your concept should be something that you are passionate about. The more passionate you are about the concept, the more emotion and care you will be able to invest in the poem.

2. Have a free-writing session

Once you have chosen your concept, now is the time to do some free-writing. The free-writing session is like a feeling-out process. You don’t have to come up with a fully realized poem. This is a chance for you to get your bearings and write about the concept without any pressure.

3. Choose the style and form of your poem

After the free-writing session, it is now time to choose the style and form for your poem. There are many forms of poetry that you could write. Just make sure that you know how to write in your chosen style of poetry. Remember that each style has its set characteristics, and you should follow them to the letter.

4. Experiment with your verses

Once you have chosen the style and form of your poem, it is now time to work on your poem. Take your time with the process. Find a good place to write, and experiment with the right tone and words that you use. Don’t be afraid to take risks. Utilize your entire vocabulary of words, and enjoy the process.

5. Read it out loud to an audience

After you have finished writing your first draft of your poem, you should read it aloud to an audience. The audience could be family and friends, or better yet fellow poets. For a first-time poet, this may be a bit scary, but this is a fear that you will have to overcome.

6. Get feedback

Your audience will give you feedback on your poem. As a rule, you should not expect applause. Remember that you are just starting out. So your work won’t really be polished, and your audience will give you both positive and negative feedback. Don’t be offended if you do get negative feedback. Remember, this is for your own progress as a writer.

7. Revise your poem

When you get feedback from your audience, make sure to revise your poem as soon as possible. Revising your poem may seem tedious at first, but you should not think of it as correcting a mistake. Instead, you should think of the revision as a way to enhance your poetry writing skills.

Final thoughts

If you want to try your hand at poetry, it is important that you know the key elements of the writing form. With this article, you will know what constitutes a poem, what kinds of poems there are, and how to write them.

Become a Self-Published Author in 3 Simple Steps

Powered by Experts, Published by You. Reach 40,000+ Retailers & Libraries Around the World. Concierge Service. Tailored Packages. BBB Accredited Business. 100% Royalty Program.

Related Articles

Writing a children’s book is a great and fulfilling endeavor for any writer. This is because writing a children’s book is not like writing any other type of book. You are writing for kids...

If you want to be a professional writer and publish a book of your very own, you will need a particular set of skills. Foremost amongst these skills is the ability...

Get started now

Privacy Policy: Writers Republic will not give, sell, or otherwise transfer addresses to any other party for the purposes of initiating, or enabling others to initiate, electronic mail messages.

Privacy Policy

Privacy commitment to our authors, effective date:.

Writers Republic abides to every author’s personal information being entrusted to us. And with that, we have stipulated a privacy policy that will show the processes of our ways in collating our clients’ personal details as needed in the publication process. As an established publishing company, our prohibitions strictly includes sharing, selling, or any illicit transactions of personal information from our clients.

Personal Details Needed:

- b) E-mail Address

- c) Phone Number(s)

- d) Physical/Billing Address

- e) Book Information

Authors can find our privacy policy through all forms of compiled and submitted information to either the company’s employees, through e-mail and phone, or from our website www.writersrepublic.com.

Information Usage

The use of the author’s personal information will take place in completing registrations, necessary materials to be used in publication arrangements with our specialists, and payment transactions that will be accomplished from our services and packages.

Registration Process

Users must fill out and complete any registration form before they can access anywhere in the Site as they wish to. These include the services, promos, blogs, and rest of the facets they can explore once they are registered to the system. The authors are entitled to a free publishing guide to give you a brief idea about self-publishing. Relevant features also include the Authors’ Lounge that teaches you some publishing tips you will be needing during the procedure.

Providing the user’s contact information like his/her name and email address during the registration will be necessary for our specialists in keeping in touch with the client anytime in regards to the manuscript submission, publishing, and finally, expanding his/her book’s publicity by any means. Our registered authors are free from accessing the website with his/her personal data or they may reach our customer service representatives through telephone or e-mail for further information and updates on our services. Aforementioned, all of the author’s personal data submitted to us will be kept confidential.

Information Sharing

Sharing of the client’s personal data to third parties is considered a violation unless it is conducted in a way it is indicated strictly in the privacy policy. Authors must understand that we are required to provide their personal data to other businesses that will to provide the required assistance in succeeding the publishing procedure, the following involves payment processor or a third party vendor benefit. These associated firms has established the consent to use the client’s personal data for necessary purposes of providing a quality service to Writers Republic.

In any case that Writers republic will conduct a union with associated companies, procurement, or sale of all or a share of its properties, authors will be notified through a notice in our website or sent through email of any ownership change or the utilization of the user’s personal data, in addition to the selections provided regarding his/ her personal information.

The company solely shares the collected information to the firms we do business with to acquaint them with the services or assistance needed for the publication. The data required plainly comprises with order completion, payment transactions, and the rest of the necessary processes. We can guarantee our users that the submission of these information will not be concomitant to any confidentialities that will identify a person’s identity. Privacy rules include prohibitions of sharing, or keeping of any private information for unrelated businesses to our company.

Data Protection

Our authors’ confidentiality comes first all the time. We follow the widely accepted preference in safekeeping the user’s personal data during its transmission and by the moment it is stored in our system. Writers Republic ensures both online and offline security of all information provided by our authors through the website. Any electronic transmittal over the internet may not be overall safe, hence the company cannot commit to an absolute protection.

The client’s agreement entails his/her responsibility in sustaining the account access, any personal information, benefits, company’s services, logins, and passwords. The author’s adherence to these sanctions include acquainting Writers Republic through phone, e-mail, or any means of communication, should there be any inadmissible access to the author’s account and all the applicable company data and services. Any direct, involuntary, minor, or distinctive damages caused due to client’s failure to adhere and/or inefficiency in utilizing the company’s site, services, and transactions will not be held liable to Writer’s Republic.

Any messages received or consequences resulted due to the user’s technical unfamiliarity or insufficient knowledge will not be held accountable to Writers Republic. Furthermore, any damages incurred due to negligence to the information entered or impermissible access will leave no liability to the company. These reparations may denote to but not restricted to revenue loss or reduced profit from the entire process.

Electronic Tracking Tools and Site Traffic Usage

Writers Republic website collects SSI (Standard Statistical Information) about the site visits and keeps a record of it as much as other websites do. Please be advised that the IP addresses, browser information, its timestamps, and referred pages are tracked for the sole purpose of maintenance and to construct the site noticeable and valuable as it can be. No accumulated data is joined routinely to other information we collect from our users.

The site server gathers fundamental technical data from our site visitors which include their IP address, domain label, and referral information. Alongside with the said above, the site also tracks the total count of the site activity from our online visitors for the intention of analyzing the flows of our site traffic. For our statistic intents, we may incorporate the information from one visitor with another into group facts, which will probably be shared on a cumulative base.

The technologies in particular: beacons, cookies, tags, and scripts are utilized by writersrepublic.com, our publishing & marketing associates, publicity service providers. These innovations are used in examining trends, website managing, tracking users’ navigation anywhere on the site and to collect public data about our user in entirety. We may obtain news founded on the utilization of these innovations by these firms on an individual as well as on an accumulated basis.

Writers Republic affiliates with third parties to offer positive features on website or to exhibit advertising based upon your web navigation activity also uses Local Storage Objects (LSOs) such as HTML 5 to gather and keep some data. Browsers may provide their own administrating tools in taking out HTML LSOs. To manage LSOs please click the link provided: http://www.macromedia.com/support/documentation/en/flashplayer/help/settings_manager07.html

Removing or Updating Your Information

Don’t hesitate to reach us directly anytime when you want to delete, update, or correct information you give over the phone or e-mail. For safety purposes, Writers Republic takes functional regulations in authenticating your identity before we grant you the access in changing and updating personal details. Your personal record and other data will be kept so long as you stay active as our site user or as necessary to offer you services. Please note that we’ll be using your information for necessary compliance of lawful commitments, imposing of agreements, and determination of disputes.

Contributors

Writers Republic will be requiring your contributors’ names to be indicated in the book publication when you opt to add them as contributors for your book publishing service. We will store your contributors’ personal details for the sole purpose of fixing their names on one of the pages of your book. Your contributors may reach us at [email protected] to request for removal of personal information from our system.

3rd Party Sites Link

Our company recommends you to carefully go over to the privacy policy of any website you visit or send personal information to. Our website comprises links to other sites whose norms and privacy regulations may contrast to ours. Accordingly, providing of personal data to these websites is administrated by their privacy rules and not ours.

Social Media Features & Widgets

Writers Republic website involves social media features such as: Facebook “Like” button and widget, such as the interactive mini-programs that run on our site or the “Share This” button. Please note that these features may set a cookie to allow the feature to appropriately function. It may also collect your IP address and which page you are visiting on our site. Your interactions with these features are either presented directly on our website or by a third party.

Announcements and Newsletters

Writers Republic will be inquiring your e-mail address if you’re interested to subscribe from our self-publishing updates, newsletters, articles, or periodic product and service announcements. You may choose to unsubscribe by clicking on the “Unsubscribe” button at the end part of the mail sent to you should you no longer want to receive emails from us.

Discounts and Promos

We offer promos and special deals on out publishing and marketing services from any given point of time. Thus, we may request for your contact details that includes your name, shipping address, demographic data, and educational attainment which will be utilized to inform the winners and prizes. Participation in any contest and promo is voluntary. The purpose for our promos, discounts, and contests, will be employed to assess and enhance eminence of or services to our clients.

Policy Changes

Any modifications or changes to be applied in our Privacy Policy will oblige Writers Republic to provide a notice on the website or by email before the change will take effect. Therefore, we recommend you to go over this page for any probable alterations and updates on our privacy norms. You may send us an email at [email protected] for all concerns, queries, and updates of personal details such as your email and mailing address. This also serves as your alternative to reach us if you want to withdraw your service or if you no longer want to receive any updates from our end.

Writers Republic will not be held accountable for any check payment issues, apart from the checks that are delivered to the address indicated below.

Writers Republic Publishing 515 Summit Ave. Unit R1, Union City, NJ 07087, USA

VIDEO COURSE

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Sign up now to watch a free lesson!

Learn How to Write a Novel

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Enroll now for daily lessons, weekly critique, and live events. Your first lesson is free!

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Nov 23, 2022

How to Write a Poem: Get Tips from a Published Poet

Ever wondered how to write a poem? For writers who want to dig deep, composing verse lets you sift the sand of your experience for new glimmers of insight. And if you’re in it for less lofty reasons, shaping a stanza from start to finish can teach you to have fun with language in totally new ways.

To help demystify the subtle art of writing verse, we chatted with Reedsy editor (and published poet) Lauren Stroh . In 8 simple steps, here's how to write a poem:

1. Brainstorm your starting point

2. free-write in prose first, 3. choose your poem’s form and style, 4. read for inspiration, 5. write for an audience of one — you, 6. read your poem out loud, 7. take a break to refresh your mind, 8. have fun revising your poem.

If you’re struggling to write your poem in order from the first line to the last, a good trick is opening with whichever starting point your brain can latch onto as it learns to think in verse.

Your starting point can be a line or a phrase you want to work into your poem, though it doesn’t have to take the form of language at all. It might be a picture in your head, as particular as the curl of hair over your daughter’s ear as she sleeps, or as capacious as the sea. It can even be a complicated feeling you want to render with precision — or maybe it's a memory you return to again and again. Think of this starting point as the "why" behind your poem, your impetus for writing it in the first place.

If you’re worried your starting point isn’t grand enough to merit an entire poem, stop right there. After all, literary giants have wrung verse out of every topic under the sun, from the disappointments of a post- Odyssey Odysseus to illicitly eaten refrigerated plums .

As Lauren Stroh sees it, your experience is more than worthy of being immortalized in verse.

"I think the most successful poems articulate something true about the human experience and help us look at the everyday world in new and exciting ways."

It may seem counterintuitive but if you struggle to write down lines that resonate, perhaps start with some prose writing first. Take this time to delve into the image, feeling, or theme at the heart of your poem, and learn to pin it down with language. Give yourself a chance to mull things over before actually writing the poem.

Take 10 minutes and jot down anything that comes to mind when you think of your starting point. You can write in paragraphs, dash off bullet points, or even sketch out a mind map . The purpose of this exercise isn’t to produce an outline: it’s to generate a trove of raw material, a repertoire of loosely connected fragments to draw upon as you draft your poem in earnest.

Silence your inner critic for now

And since this is raw material, the last thing you should do is censor yourself. Catch yourself scoffing at a turn of phrase, overthinking a rhetorical device , or mentally grousing, “This metaphor will never make it into the final draft”? Tell that inner critic to hush for now and jot it down anyway. You just might be able to refine that slapdash, off-the-cuff idea into a sharp and poignant line.

Whether you’ve free-written your way to a beginning or you’ve got a couple of lines jotted down, before you complete a whole first draft of your poem, take some time to think about form and style.

The form of a poem often carries a lot of meaning beyond the structural "rules" that it offers the writer. The rhyme patterns of sonnets — and the Shakespearean influence over the form — usually lend themselves to passionate pronouncements of love, whether merry or bleak. On the other hand, acrostic poems are often more cheeky because of the secret meaning that it hides in plain sight.

Even if your material begs for a poem without formal restrictions, you’ll still have to decide on the texture and tone of your language. Free verse, after all, is as diverse a form as the novel, ranging from the breathless maximalism of Walt Whitman to the cool austerity of H.D . Where, on this spectrum, will your poem fall?

Choosing a form and tone for your poem early on can help you work with some kind of structure to imbue more meanings to your lines. And if you’ve used free-writing to generate some raw material for yourself, a structure can give you the guidance you need to organize your notes into a poem.

A poem isn’t a nonfiction book or a historical novel: you don’t have to accumulate reams of research to write a good one. That said, a little bit of outside reading can stave off writer’s block and keep you inspired throughout the writing process.

Build a short, personalized syllabus around your poem’s form and subject. Say you’re writing a sensorily rich, linguistically spare bit of free verse about a relationship of mutual jealousy between mother and daughter. In that case, you’ll want to read some key Imagist poems , alongside some poems that sketch out complicated visions of parenthood in unsentimental terms.