Pros and Cons of Growing Up as an Only Child Essay (Critical Writing)

Introduction.

Not many people know what the term pros and cons mean and how it affects a child and the parents. The word pros mean that the child is being raised alone in the family hence has no one to share resources with or fight for things in the home. Cons mean loneliness or boredom.

Children born alone in the family have advantages and disadvantages. The grandparents in such families seem to love these children so much although even in a family with many siblings the grandparents also seem to love them with a single child, the love is not divided. The attitude of grandparents may be affected by traditional believes since they have different beliefs according to their background.

A lone child enjoys all the benefits of the family alone since he/she has no one else to share with. There are no economic constraints in such a family although even if the family has many children they usually have a way to care for their family since they planned for them again nowadays there are many methods of family planning so it is the role of the couple to choose the number of children they want although there is the aspect of God being in control of children to the believers.

Just as Rhoda M. in her article in www. Helium says; she grew alone so she had more cons than pros. she says that she had no one to play with & her life was spoilt I tend to believe her and this from experience with my own cousin.

A child raised alone can be spoilt and is hard for such a child to be independent although in school most of them do very well because the parents have a lot of attention in his/her homework or school work to be more specific. Let me once more revisit the story of my cousin. She was born and grew alone with her parents in an environment where they were no children even nearby the village with whom she could play. The only person she could play with was the parents. She was over pampered by the parents and the grandparents. She had all kinds of toys to play with but she was never contented because not all the time the parents were available for her to play with and again not all kinds of games she could play hence making her life in the home more miserable despite the fact that she had all that she needed. She lacked nothing that she needed. When she went to school after work the parents made sure that they had looked at her books and knew her progress in school and also her studies at home. I admired the way she was living and wished I could also be alone little did I knew that she did not enjoy much being alone. She was so solitary and bored at times for she had no one to play with. I evidenced this during the holidays because she was coming to our home and when the schools re-opened she could cry her heart out refusing to back to their home until she could be beaten up at times. I was wondering why she was behaving like that since she lacked nothing and ate the best foods. It’s later I came to realize that the cons were outweighing her and came to accept the saying of the late Pope John Paul II who said that “the only gift parents can give their children are sisters and brothers”.

Being the only child of the parent is enjoyable only at the tender age but when a time reaches when you have to be independent live starts being tough or when you have to live with other people especially in boarding schools where you seem to share everything and that is a life that you have never been introduced to.

Just as my cousin was living with her parents being provided with everything now things have taken another trend she is spoilt and might remain the same way for the rest of her life as Rhoda was saying in her article that she was spoilt. Now my cousin is married and keeps on bothering her husband every now and then. When they have a grudge and disagrees about an issue she runs home to her parents who have nothing else to do apart from regretting why they did not limit their love to her. The parents have no choice but to talk to her and sometimes she even doesn’t heed to whatever they say and they have no other option apart from giving her whatever she needs.

In China, there is a policy that governs the number of children one has to have and this policy was started in 1980. According to Chinese by James Reynolds BBC News, the national policy is for couples to have a single child and law has to be taken for anyone who violates that rule. In China, if a woman gets pregnant the second time she is allowed to take an abortion. Some of the reasons that make this country be so strict on the number of children are scarcity of land and poverty so raising many siblings becomes a problem. I read in a daily nation in 2006 that there was a couple in China who got many siblings and had to give out some of them to the relatives because they were unable to raise them. This policy can work well in the US because as the Chinese sterilize women and accept abortion the US government also accepts the same and their basic aim is to control the population. An American writer McFann, Carolyn says that there are pros and cons about a single child in the family although he advises couples to have one child. The American’s prefer just a single child either being adopted or born for the sake of heirs. The few numbers of siblings in the US enable them to control the population and this is one of the reasons that it remains a developed country. The fact that the country has few people there is no limited space and resources and the rate of pollution is low despite the fact that there are many industries. The benefit of and liabilities are the activities which children engage in. these benefits are realized by a child who is alone since there is no competition. Doreen Nagle says that all these benefits such as gifts, picnics, and the like are a result of the parents having no other child hence can afford to provide each and every other thing that the child needs.

Although having one child is important it is good for the parent to take caution on how they bring up the child to avoid spoiling her and her life just as my cousin was spoilt. Parents should love these lone children but should have limitations because even the bible(to the believers) in proverbs states it clearly that ‘spare the rod spoil he child’ parents should be very cautious on how they handle their kids for them to grow up with good manners although there are few who are too hard to handle.

In cultural perspectives, there are different views of lone siblings depending on the locality and the tribe and their beliefs. In history, there are those who had superstations and in the traditional setting, the number of children determined the amount of wealth one had.

In my culture, they believe that having one child there are more cons than pros just as Rhoda M was believing. This child has most of the time to be with adults although this might create good closeness with the parents hence the parents can be in a good position to guide and counsel their child and also help him/her out of peer pressure. Even if the children fight when they are at a tender age and lack toys, gifts, and the like at times it is better to have at least two or three siblings because when they grow up they become cooperative and live in harmony helping each other, sharing and a less weight to cater for the parents in their old age although not all children can live this way.

According to Aronson, J.Z book, parents should have a single child so that they can be able to recruit him/her in academics because education is the only key to success and it’s the responsibility of a parent to do so.

In my opinion, one child is better than having multiple of them although two are better than one for socialization, playing, and deep connection. A one-child family is attractive and the couple does not need to worry much after they retire about how their child will survive since they take care of him/her with the few resources that they have. The only thing I find a nuisance is an overindulgence in the love for the child because this might spoil the child. I would prefer parents to have one child due to the current economical constraints and the fact that modern technology is so high hence people are more involved in other issues rather than large families.

Aronson, J.Z (1996). How schools can recruit hard-to-reach parents. Educational leadership.

Berger, K.S (2001). The developing person through the lifespan. New yolk: Worth. James Reynolds BBC news, Henan province, central China.

McFann, Carolyn. (2007). When planning your family, consider the pros and cons of being an only child. Ezinearticles.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, August 27). Pros and Cons of Growing Up as an Only Child. https://ivypanda.com/essays/pros-and-cons-of-growing-up-as-an-only-child/

"Pros and Cons of Growing Up as an Only Child." IvyPanda , 27 Aug. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/pros-and-cons-of-growing-up-as-an-only-child/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Pros and Cons of Growing Up as an Only Child'. 27 August.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Pros and Cons of Growing Up as an Only Child." August 27, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/pros-and-cons-of-growing-up-as-an-only-child/.

1. IvyPanda . "Pros and Cons of Growing Up as an Only Child." August 27, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/pros-and-cons-of-growing-up-as-an-only-child/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Pros and Cons of Growing Up as an Only Child." August 27, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/pros-and-cons-of-growing-up-as-an-only-child/.

- The Secret by Rhoda Byrne

- The Prescott Valley Events Center

- Lone Parents: Social Work and Exclusion

- Saudi Arabian Lone Wolf Terrorism in 2011-2016

- “The Odd Women” and “Women in Love”: Evolving Views of Gender Roles

- Child Behavior Today and Ten Years Ago

- Grandparents-Grandchildren Relations Then and Now

- Lone Workers in the Waste Industry

- Finding Financing for Business Startup

- Grandparents Raising Grandchildren With Disabilities

- Parental Roles and Changes in the Last 50 Years

- Spanking Is Harmful to Children

- Parental Hopes and Standards for Sons and Daughters

- Growing Up with Hearing Loss

- Parenting Education Programs: Pros and Cons

Not So Lonely: Busting the Myth of the Only Child

A burgeoning acceptance toward families with only one child is finally starting to creep into society at large, eliminating the mythical stereotype.

Bill and Hillary have one. Franklin D. Roosevelt was one. And the chances are you probably know one or two. Even I have one of the selfish, lonely, and maladjusted creatures said to be populating America in greater numbers every year. I am referring to the “only child,” also known as singletons or onlies.

Despite the only child being a growing demographic, having one still attracts a surprising amount of criticism. At a playground in London, one mother told me she thought having an only child was tantamount to child abuse as she watched my daughter toddle alone in the sandbox. When I told my mother that I probably wouldn’t have any more children, she exclaimed disparagingly that one child was “simply not a family.” My husband, on the other hand, has not had any of these accusations leveled against him. The shaming of mothers of singletons is yet another arena in which guilt, scorn, and impossibly high expectations are heaped upon women, encouraged by society’s biased views.

A year ago, the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs estimated the world’s population at 7.2 billion. At the same time, natural resources like clean air and water are dwindling. Yet to talk of restricting the number of children people choose to have smacks of coercive policy-making or, worse, genetic engineering. In developed countries, though, a limit on family size seems to be occurring organically, without the need for legislation or encouragement from campaigners. If you had asked American women in the 1930s how many children they wanted, 64 percent would have said they wanted at least three. Today, most women feel that 2.5 is ideal. Many of us, however, don’t manage more than one. In fact, 23 percent of Americans have only one child; in New York City, as in a lot of urban centers, the figure is 30 percent.

For many, the rationale for stopping at one child is financial. The cost of raising a kid in the U.S.—before he even gets to college—is $245,300. For others, there simply aren’t enough childbearing years left to have another. And, for a very small minority, the environment and overpopulation are factors. But there is something else at work here: Society is moving away from seeing only children as disadvantaged—though the shift is happening painfully slowly.

Just more than a hundred years ago, the psychologist G. Stanley Hall declared that being an only child was a disease in itself. He was responsible for putting forth the stereotype of the singleton as deficient, indulged, and spoiled. His theories—which he promoted around the same time that psychoanalysis was beginning to blossom—firmly took root. Hall has since undergone some scrutiny, and many of his theories have been rejected within the realm of academia, but popular opinion has yet to catch up. Hall’s words continue to reverberate around playgrounds and kitchen tables all over the country. We hear so often that only children are self-centered, antisocial, and unable to share, that the stereotype has become a self-fulfilling prophecy, or at the very least, what is known as a “ cultural truism .”

In her essay “ G. Stanley Hall: Male Chauvinist Educator ,” the scholar Gill Schofer accuses Hall—the father of child psychology—of being outdated. In Hall’s eyes, women were born solely to be mothers and wives. They were not to engage in any pursuits that might be mentally taxing, such as learning Latin, Greek, or mathematics. If women were to roam outside the realm of the house, society would crumble.

In fairness to Hall, who was born in 1844 and lived the life of a Victorian gentleman, these views were not uncommon for the time. He wrote at length about his mother , whom he worshipped. He described her as the epitome of the Angel in the House, selflessly devoted to her children, her husband, and God. For society to function, Hall believed, all women needed to model themselves on her.

Some of Hall’s opinions were quaint, while others were dangerous. For instance, he advocated something called “retarding,” a process by which a girl’s education was designed to prevent her from engaging in analytical or cerebral pursuits—any curiosity about important subjects such as science, history, or politics was to be repressed in order for her untainted maternal intuition to come to the fore. To Hall, “a purely intellectual woman is…a biological deformity .” And “to a man, wedlock is an incident, but for women, it is destiny.”

So why have Hall’s views on only children held such a grip on our culture when we have shed every one of his opinions on gender roles? In the 1980s, when more women were heading for the workplace and delaying having children, articles in academic journals with titles like “ Negative Stereotypes About Only Children Unfounded; They Do Well on Any Measure ” finally started to appear. These articles helped balance the established preconceptions about only children with careful research. And then, in 1987, Denise F. Polit and Toni Falbo undertook the first large-scale attempt to understand the effects of not having siblings on children.

Polit and Falbo’s findings, which were the result of in-depth analysis of past and current studies, came to the conclusion that singletons and multiples shared much more than we had previously thought. What’s more, they found that the disadvantages of being an only child were, on balance, nonexistent.

Reading the study today, certain details jump out, such as the section on antisocial behavior, one of the traits Hall ascribed to onlies without exception. In previous research, sociability had been measured by self-report, with only children seeing themselves as much less sociable than other children. However, when peers were asked about the sociability of singletons, they were said to be more sociable than children with siblings on average. Another case of cultural truism, perhaps? If you tell a child often enough that he is unsociable, eventually he’ll start to believe it.

More recently, Lauren Sandler’s 2013 book One and Only: The Freedom of Having an Only Child and the Joy of Being One , merges personal stories and anecdotes with up-to-date statistics. Parental happiness, Sandler reports, declines with every child. And in Denmark, women with one child scored far happier than women with no children or women with more than one. Despite this research, the myth of these sad and lonely only children with their desperate and unfulfilled mothers stubbornly persists.

Many studies on the benefits of one-child families, however, seem to feature factors that are irrelevant to many women when they are deciding how many children to have. Most of us probably don’t pay much heed to the fact that only children have higher IQs than those with siblings, or the fact that they often reach higher academic rankings . It certainly wouldn’t be a reason for any woman I know to stop at one. The fact is that modern motherhood and a working life are often incompatible. Some women excel at juggling careers and multiple children—either through hard work, having the money for childcare, living near family members who can look after their children for free, or any combination of these factors. Others simply can’t do it. We stop at one because we don’t have the money, the time, or the love for another child. Our financial and emotional resources, we feel, are only ample enough to nurture one child well. Or perhaps crippling postpartum depression frightens some women away from going through the difficult and lonely years of caring for another baby. That was certainly a factor for me.

One major raison d’être for feminism is to allow women to make informed choices: whether or not to marry, to work, to have children. But the taboo around choosing to have one child persists. I found it shocking that so many people I barely knew felt entitled to point out how selfish I was for not giving my daughter a sibling. But selfishness is closely linked to—and sometimes confused with—self-preservation, a human being’s most deeply ingrained instinct for survival, and a desirable and healthy characteristic for someone raising a child.

Perhaps, in time, as more people choose to stop at one child, the stigma will disappear. This will also make it easier on those who had the decision to have one child thrust upon them through infertility, ill health, the breakup of a relationship, or, in some cases, the death of a child’s sibling. It will also free children without siblings from having to prove to the world that they can be social, generous, and well-adjusted. Negative comments directed at one-child families suggest a view of life where we can all choose what we want, when and how we want it. Even when it comes to having children, the image that people are being sold—and that some are buying—is one of the happy consumer with an array of endless choices. Yet the reality of bearing children is far from this.

Whatever happened to the idea that life cannot be perfectly planned, nor can we always get what we want when it comes to the big decisions facing us. We are all muddling through, doing the best we can. Siblings won’t necessarily make a sad and lonely child happy, nor will not having siblings necessarily make a happy child miserable. Singletons, in other words, are more maligned than maladjusted , and it does them a disservice to perpetuate outdated stereotypes invented by a reactionary Victorian gentleman. G. Stanley Hall has been dead for 90 years. Maybe a burgeoning acceptance toward one-child families is finally starting to creep into society at large, one that will allow modern women and the people around them to stop seeing one child as being “only” one, and to start seeing them for the abundance they really are.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

More Stories

Meet Saint Wilgefortis, the Bearded Virgin

Nice Guy Spinoza Finishes…First?

A Body in the Bog

A Mughal Mosque in Kenya

Recent posts.

- From Saint to Stereotype: A Story of Brigid

- Christy’s Minstrels Go to Great Britain

- Animals at Play, Ama Divers, and Nuclear Power

- Missouri Compromise of 1820: Annotated

- The Power of Pamphlets in the Anti-Slavery Movement

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Why I'm Glad I Grew Up an Only Child

Updated on 7/23/2018 at 10:03 AM

:upscale()/2016/04/13/874/n/1922398/94139c315fd90d6a_IMG_5964_copy.jpg)

The most common question I was asked as an only child growing up was, not surprisingly, "Don't you wish you had a brother or sister?" And for as long as I can remember, I've always answered "no" without any hesitation. "You'll always have someone to play with, you'll have a lifetime support system ," they said. Although enticing, I never longed for a sibling and I'm sure my parents were thrilled I never asked. (Mom and Dad, you're welcome.)

In my current early adult years, it's not unusual for people to be surprised at my sibling-less life. I'm told that I don't seem like a single child, which is most often defined when I ask as spoiled, attention-hungry, self-centered, and dependent. I guess it's better than getting the reaction, "Oh, that makes sense," but the fact is, I believe that growing up alone contributed to the absence of those traits.

It was never about the attention nor not having to share — those weren't the reasons I never cared for a brother or sister. I kept busy with neighbors and friends and I didn't mind the moments I was alone. I always had quite the imagination so it wasn't hard to get creative and I think I've always been able to appreciate time to myself — even as a child. My tripod of a family was fulfilling enough and I would cringe inside when others criticized or questioned my mother's decision to stick with one . Yes, an older sibling would have been able to watch over me and my future children would have aunts and/or uncles like the loving ones I grew up around. But I believe that my strong independence today can easily be attributed to me growing up as an only child.

I like that I was able to forge my own path rather than live in the shadows of someone else, and that I had to learn things on my own as I went. Plus due to some fantastic parenting, I learned to be self-sufficient at a very young age, which has made me totally fine as a now-22-year-old, still pretty-fresh-out-of-college woman who lives alone in a new city.

I was always fascinated by the fact that those with siblings had a unique bond with somebody else in their family other than a parent, cousin, or relative; a blood relationship with a peer almost — something that I will never be able to experience myself. I've never really been envious of my friends for that, but I do understand the many joys and perks that come with having a brother or sister . I probably wouldn't have gotten as bored at times and would've always had a readily available confidant. However, I'm thankful for my solo upbringing.

So next time someone pressures you to have more children or gives you crap about being an only child yourself, tell them that I turned out just fine — and your child will too!

- Family Relationships

- Personal Essay

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

The highs and lows of being (or having) an only child

Readers respond to Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett’s article about the criticism some parents face for having one child

This was an interesting article by Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett ( ‘One and done’ parents are some of the most thoughtful and compassionate I have met, 31 March ). I remember a fascinating radio programme some years ago, in which researchers asked only children about their experiences. About half reported that being an “only” made it hard to make friends because they had no practice with siblings – they became loners with a lack of good relationships. The other half reported that having no siblings obliged them to become socially skilled, and that they were great at forming relationships.

The researchers concluded that only children are just like the rest of us, displaying the same range of personality traits and resulting life journeys. Alison Carter Lindfield, West Sussex

I was staggered that anyone with only one child would merit criticism for any reason. In my book, that would be a high accolade. I was an only child of an only child, and in youth had always hankered for a sibling. When I decided to follow a different path and had two, they fought and are still, in middle age, not best buddies. When number one had two children, they fought. Number two had one child. She and I have formed an “only child club” and are both highly able to entertain and occupy ourselves when left to our own devices.

Only children can be great, can usually stand on their own two feet, have no one else to live up to or feel threatened by, and are able to cope with singledom when necessary. Name and address supplied

Interesting that Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett’s discussion about the impact of being an only child focuses on their experience as children. Apart from the solidarity that a brother or sister can give you, one important advantage of having siblings is sharing your parents as you, and they, get older.

Siblings can share the burden of parental expectation (whether about careers or grandchildren), but also share support and care for elderly parents as they become frail.

I have been very aware of these issues when I compare my own experience – I have four siblings – with that of my friends who are only children. Whether it is practical support or just someone to discuss options with, that shared responsibility is invaluable. Cath Attlee London

What people fail to mention when questioning someone for choosing to have only one child is that it might not be a choice. I was pregnant three or four times, some pregnancies with traumatic outcomes, before my final successful pregnancy that resulted in our beautiful child. Even with this pregnancy, I spent three months in hospital on bed rest with high blood pressure. So having achieved a healthy child, I could think of no reason to put our little family through such potential trauma again.

Our child has grown up to be kind, caring and all we could wish for. Having been a model, then actress, she is now in her second year’s training to be a midwife – something that she said she always wanted to do despite my horror stories, having been a midwife myself.

So, no, only children are no more likely to be spoiled than any one else. Also, there is no guarantee that you will get on with your siblings. Gabrielle Page Brentwood, Essex

- Parents and parenting

Most viewed

Growing up, I didn't mind being an only child. Now as an adult, I hate it.

- My mom recently asked me if I dreaded being an only child when I was little, which I didn't.

- I didn't tell her that being an adult with no siblings puts a lot of weight on my shoulders.

- Having siblings doesn't guarantee a good relationship, but I wish I had someone else to help.

When I was born, my parents were considered " old " parents . They were 37 and 38, and their plan had never been to have me so late in their lives. They had been married for 12 years and unexplained infertility led to them being childless while everyone around them had babies.

After trying all the fertility treatments available at the time, without any results, my parents started the process of adoption. Shortly after my mom found out she was pregnant, she was put on bed rest and the adoption agency paused their search because they wanted my parents to focus on their miracle: me.

Related stories

Throughout my entire life, my mom has joked that I could've had a sibling the same age as me had the agency not been so old school. Growing up I really didn't feel like I needed a sibling , but now as an adult, I wish I had one.

My childhood was amazing

Only children are often asked if they were bored or lonely growing up. The truth is that I wasn't at all. In true Gemini form, I make friends wherever I go, so I kept a busy schedule hanging out with friends all the time. Those friends are still, to this day, like my family.

We also moved a lot because of my dad's job, which meant we got to travel the world and explore new cultures. I know that if my parents had had more children, this wouldn't have happened because of school schedules, the cost of living, and the logistics of a big family.

I could always bring a friend when we went on summer trips, so my parents could have adult time while I had someone to play with.

They were also incredibly involved in my life. I have vivid memories of my mom going tubing with me in Mexico because we needed two people. She didn't really want to ride it, but also didn't want to deprive me of the fun. She lost her bikini top on that ride, and decades later, we still laugh about it.

Now, as an adult, I wish I had someone to help me out

I'm still incredibly close to my parents; we talk almost every day on the phone and text around the clock. While I don't consider them my best friends, I have a more open relationship with them than most of my friends have with theirs. I also live on the other side of the world to them, and not seeing each other as often as we'd want to means we communicate frequently to make up the difference.

Recently, my mom shared that my dad had lost three of his friends in one week and was feeling sad. A wave of emotions engulfed me: On one hand I wanted to hug my dad, and on the other, I was full of dread over what would be coming up for me.

Though I didn't mind being an only child as a kid, now as an adult, I'm filled with fear of being the only one to take care of my parents. And while I fully know — from seeing how my own aunts and uncles didn't take care of my grandparents — that a sibling does not equal more help with aging parents, I don't even have someone to talk to about it. It helps that my husband is incredibly supportive, but he has his own dad to take care of, so I feel guilty throwing even more onto him when I know he's already dealing with so much.

I also carry immense guilt for having left my home country to chase my dream career. If anything were to happen to them, I am over 15 hours away by plane. I bounce between wanting my own life and wanting to be there for them as they become older and need more help.

Recently my mom asked me if I ever had wanted siblings . I told her, "No." She said I had just removed the biggest weight from her shoulder; I didn't have the courage to tell her all of this.

- Main content

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Who benefits from being an only child a study of parent–child relationship among chinese junior high school students.

- Institute for Population and Development Studies, School of Public Policy and Administration, Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an, China

After more than three decades of implementation, China’s one-child policy has generated a large number of only children. Although extensive research has documented the developmental outcomes of being an only child, research on the parent–child relational quality of the only child is somewhat limited. Using China Education Panel Survey (2014), this study examined whether the only child status was associated with parent–child relationships among Chinese junior high school students. It further explored whether children’s gender moderated the association between the only child status and parent–child relationships. Two-level ordered logit models suggested that only children were more likely to report a close relationship with their mothers and fathers compared to children from multiple-child families (including two-child families). Taking birth order into consideration, we found that, only children were more likely to have close parent–child relationships than firstborns, whereas no significant differences were found between only children and lastborns. Interaction analyses further suggested that the only child advantages were gender-specific: the positive effects of the only child status were stronger for daughters than for sons, that is, daughters benefited more from being only children. Our findings highlight the importance of considering children’s gender and birth order in exploring the only child effects in the Chinese context. Additional analyses about sibling-gender composition indicated female children were more likely to be disadvantaged with the presence of younger brothers, whereas male children benefited more from having older sisters. This reveals that the son preference culture is still deep-rooted in the Chinese multiple-child families.

Introduction

In 1979, China implemented the highly controversial One-Child Policy (OCP) which required the number of children for each couple to be limited to only one Child ( Falbo and Hooper, 2015 ). Exceptions existed in a few cases. For example, couples who were ethnic minorities, whose first child had disabilities, or whose (from rural areas) first child was a girl could get the chance to have a second child with permission ( Li et al., 2015 ). The One-Child Policy, coupled with the socio-economic development, made China’s fertility sharply fall from 6 in the 1970s to 1.5 in 2010 ( Cai, 2013 ). Although this policy ended on January 1, 2016 and was replaced by a universal Two-Child Policy ( Qian and Jin, 2018 ), the profound impacts of this policy on Chinese society still persist ( Chi et al., 2020 ).

One of the impacts is the generation of large numbers of one-child families. In 2010, the total number of only children rose to 145 million ( Wang, 2013 ). This special group has attracted the attention of many scholars ( Chi et al., 2020 ). A growing body of literature has documented the developmental outcomes of being an only child. Generally speaking, two views exist in academia with regard to the welfare of growing up as an only child ( Liu et al., 2010 ). One view supports the negative side. The notion “being an only child is a disease in itself,” remarked by Fenton (1928) , has provided a base for the popular thinking that only children tend to be spoiled by their parents and grandparents ( Mancillas, 2006 ; Liu et al., 2010 ). This idea argues the adults in the families tend to prioritize the needs of the only child, which could result in adverse developmental outcomes of this child, such as dependence, self-centeredness, and indifference ( Roberts and Blanton, 2001 ; Mancillas, 2006 ). In addition, because only children have no siblings to interact with, they perhaps lack proper interpersonal skills to efficiently negotiate their relationships with their peers ( Downey and Condron, 2004 ). Based on this idea, the popular media usually referred to Chinese only children as “little emperors” ( Fong, 2004 ; Falbo, 2012 ).

However, the above popular thinking was deemed a stereotype for only children ( Mancillas, 2006 ) because it was not supported by most empirical studies both in the West ( Falbo and Polit, 1986 ; Mellor, 1990 ; Falbo, 2012 ) and in China ( Poston and Falbo, 1990 ; Falbo and Poston, 1993 ; Guo et al., 2018 ). Therefore, the other perspective about only children was more positive in its nature: only children tend to be either normal or more advantaged compared to those with siblings in many developmental dimensions ( Falbo and Polit, 1986 ; Polit and Falbo, 1987 ; Mellor, 1990 ; Falbo, 2012 ; Chen and Liu, 2014 ). In China, studies of only children have focused on a variety of outcomes. Concerning academic outcomes, Chinese children without siblings appear to have higher academic achievements and cognitive abilities than children with siblings ( Poston and Falbo, 1990 ; Falbo and Poston, 1993 ; Jiao et al., 1996 ). With regard to psychological outcomes and character features, some studies observed no significant differences between Chinese only children and non-only children ( Poston and Falbo, 1990 ; Guo et al., 2015 ; Wang et al., 2020 ), and others reported better outcomes of only children ( Liu et al., 2010 ; Falbo and Hooper, 2015 ; Guo et al., 2018 ). In terms of the traditional virtues, research demonstrated that although Chinese only children did not differ from their non-only counterparts in the sense of family obligation or filial piety ( Fuligni and Zhang, 2004 ; Deutsch, 2006 ), they are more motivated to have higher achievements in order to assume the responsibility supporting their aging parents ( Fong, 2002 , 2004 ).

Even though an extensive body of literature has made comparisons between the Chinese only, and non-only children on a variety of developmental outcomes (such as academic, psychological, and behavioral outcomes), only a few studies have focused on the comparison of the parent–child relationships between the two groups. According to Western research, the variations in parent–child relationships could explain the differences in developmental outcomes between only children and non-only children ( Falbo and Polit, 1986 ; Polit and Falbo, 1988 ; Mellor, 1990 ; Falbo, 2012 ). Meta-analyses conducted by Falbo and Polit (1986) suggested that the different developmental outcomes between only children and non-only children is because the former group have a special parent–child relationship characterized by increased parental anxiety and attention ( Falbo and Polit, 1986 ; Falbo, 2012 ). Specifically, parents of only children tend to be more anxious than their multiple-child counterparts because of their inexperience in rearing children ( Falbo and Polit, 1986 ). In this case, parents of only children would be more careful and responsive in the child-rearing activities than parents of more children, leading to high-quality parent–child relationships ( Falbo and Polit, 1986 ). Further, the high-quality parent–child relationships would encourage children to interact more with their parents, thereby resulting in a stimulating home environment which was beneficial for only children’s developments ( Polit and Falbo, 1988 ). However, such parent–child relational pattern of only children is observed based on Western literature ( Falbo, 2012 ). Whether the parent–child relationships in Chinese families vary with the sibling status? Are Chinese only children more likely to have a close relationship with their parents than their non-only counterparts? Whether the only child effects, if any, differ based on children’s characteristics? This study is designed to answer the above questions.

The Only Child Status and Parent–Child Relationships in Chinese Families

According to attachment theory, parent–child relationship plays an important role in shaping children’s development ( Videon, 2005 ; Levin et al., 2012 ; Ma et al., 2020 ). Studies have consistently documented the significant impacts of relationship with caregivers on children’s developmental outcomes in China and other cultures ( Dmitrieva et al., 2004 ; Chen, 2017 ; Li et al., 2018 ; Xu et al., 2019 ). A harmonious parent–child relationship provides children a sense of security, which is fundamental for their well-being ( Li et al., 2018 ). For example, in a study conducted among Shanghai public school students (age = 15.3 years), children’s attachment to mothers as well as fathers was found to predict their academic engagement ( Chen, 2017 ). Another study using nationally representative data demonstrated that, in addition to academic achievement, parent–child relationships (together with parental presence) also influenced Chinese children’s cognitive and psychological outcomes ( Xu et al., 2019 ).

The nature of parent–child relationships is highly influenced by culture and social structure ( Chow and Zhao, 1996 ). In Chinese families characterized by Confucian culture, parents have greater authority and power in the hierarchical parent–child relationship than their Western counterparts ( Chow and Zhao, 1996 ; Lu and Chang, 2013 ). Therefore, Chinese children are required to obey their parents on any child-related issues and filial piety is regarded as a necessary virtue a person should have ( Chow and Zhao, 1996 ). However, influenced by the Western culture emphasizing individualism, Chinese parent–child relationship is becoming more egalitarian in recent years ( Sun, 2011 ). Meanwhile, with the development of social economy, the children’s economic value drops while their emotional value increases ( Goh and Kuczynski, 2010 ; Sun, 2011 ). A child-centered culture has gradually risen in Chinese families ( Tsui and Rich, 2002 ). In this situation, Chinese parents are becoming emotionally closer to their children than before ( Tsui and Rich, 2002 ; Sun, 2011 ). Therefore, considering the dramatic changes taking place in Chinese families as well as the shifts in parent–child relational pattern in recent years, it is particularly important to gain insight into parent–child relationship in modern Chinese families.

According to family systems theory, many factors determine the quality of parent–child relationship, such as marital relationship of parents ( Li et al., 2018 ). In the present study, we mainly focus on the effects of only child status (family size) on parent–child relationship. A negative association between family size and parent–child relationship is widely reported in the Western literature ( Falbo and Polit, 1986 ). For example, studies of Western families have demonstrated that the parent–child relational quality was higher in one-child families than in larger families ( Falbo and Polit, 1986 ; Falbo, 2012 ). In Lewis and Feiring (1982) ’s study, family members were observed more likely to be involved in conversations including more frequent parent–child discussions during family meals in one-child families than in multiple-child families. Some studies focusing on the comparisons between only children and non-only children also took birth order into consideration ( Falbo and Polit, 1986 ; Mellor, 1990 ; Falbo, 2012 ). Meta-analyses of Western literature showed that, although only children have better relationships with their parents than non-only children in general, they are not significantly different from firstborns or children from two-child families ( Falbo and Polit, 1986 ; Falbo, 2012 ). The Largest differences usually came from the comparisons between only children and children with more than one sibling or children of later born ( Haan, 2010 ; Falbo, 2012 ). As discussed above, this is because parents of only children, firstborns, or children with only one sibling have greater anxiety about parenting (more responsive to children’s needs) and more attention in child rearing activities ( Falbo and Polit, 1986 ; Falbo, 2012 ).

The resource dilution model could explain the link between sibship size and parent–child relationships. The term “resource dilution” is first used by Blake (1981) to describe the relationship between family size and the quality of children. Resource dilution model argues that parental resources are not infinite and with the increase in the number of children, the resources invested in each child decrease ( Blake, 1981 ). Parental resources can take many forms, such as those providing a supportive home environment, opportunities to engage with the outside world, and direct treatments, such as attention ( Polit and Falbo, 1988 ; Gibbs et al., 2016 ). The parent–child relationship is also a kind of parental resource because it is closely related to parental time (attention) spent on children or parent–child interactions: the more time parents devote to their children, the closer the parent–child relationship is ( Li et al., 2015 ).

Although limited, there are still a few studies analyzing how sibship size influences Chinese parent–child relationships. Most of the existing research suggested a more positive parent–child relationship of only children compared to their sibling counterparts. Using data of Beijing schools, Chow and Zhao (1996) showed that parents of only children spent a greater proportion of their leisure and total time on their singleton children than did parents of non-only children. The author also compared other parental resources invested in only children and non-only children and found that the only children were generally in a more advantaged position ( Chow and Zhao, 1996 ). Hao and Feng (2002) used data collected from Hubei Province and found that parents of only children interacted more frequently on both verbal and physical activities with their children than did parents of non-only children. Wei et al. (2016) observed an only child advantage in maternal educational involvement in Chinese families. In a qualitative study by Deutsch (2006) , compared to children with siblings, children without siblings were found to be more concerned with the parent–child relationship and have closer emotional bonds with their parents. By analyzing the social behaviors of Beijing kindergarteners, Li et al. (2015) found that non-only children had slightly closer mother–child relationship than did only children. This pattern is not in line with the resource dilution model perhaps because the sampled families were highly selected and the multiple-child families in Beijing had more resources: the mothers of non-only children did not have to work. In this case, non-only children might have more time to interact with their mothers than only children whose mothers working outside the home ( Li et al., 2015 ).

In sum, existing studies were limited and findings were mainly based on regional data. More representative national-scale data are needed to further examine how only children and non-only children are emotionally attached to their parents and whether there are significant differences between the two groups. Western studies have detected the birth-order effects that only children were no different from firstborns but significantly different from laterborns in terms of parent–child relationships ( Falbo and Polit, 1986 ). Does this pattern apply to Chinese children? Studies of Chinese only children failed to do the comparisons between only children and children of different birth order regarding parent–child relationship. Therefore, this study also aims to fill in the research gap by considering the birth order of children.

The Role of Children’s Gender

Influenced by Confucianism culture, children’s gender plays important role in Chinese parenting strategies. Due to the patriarchal, patrilineal, and patrilocal structure, women are subordinate to men and young women are in the lowest strata of the family hierarchy ( Shu, 2004 ). In this system, daughters are traditionally devalued because they would eventually marry into another family and would have to contribute to that family. Natal families could not see benefits in investing in daughters ( Xie, 2013 ). However, this is not true for sons. Sons are not only expected to support their elderly parents but also responsible for carrying on the family lines ( Sun, 2002 ). Therefore, investments in sons was deemed more rewarding than investments in daughters. As a result, Chinese parenting strategies have been characterized by a son preference for a long time ( Guo et al., 2018 ). The female infanticide in Chinese history is a proof of that ( Das Gupta et al., 2003 ). However, as discussed above, with the implementation of the One-Child Policy and socio-economic development, a child-centered phenomenon is emerging in Chinese families ( Tsui and Rich, 2002 ). By having fewer children or only one child, parents would not show gender preference in their parenting strategies ( Tsui and Rich, 2002 ). Empirical studies have found a narrowing male-favorable gender gap in education ( Ye and Wu, 2011 ) or even a reversed educational gender gap among the Chinese only child group ( Lee, 2012 ). For example, Ye and Wu (2011) found that gender inequality in education among younger cohorts was less prominent than among older cohorts due to the fertility decline in China. This implies that the daughter benefits more from having fewer siblings or being an only child in intra-household resources allocation than does the son ( Lee, 2012 ).

Parent–child relationship is a reflection of emotional and time resources parents invest in children. Therefore, when applying the resource dilution model to analyzing the link between sibship size and parent–child relationship in Chinese families, children’s gender needs to be given special attention ( Chu et al., 2007 ). To the best of our knowledge, little research has examined the role of children’s gender in the association between sibship size and parent–child relationship. To fill in the important research gap, this study will gain an insight into whether the only child advantages (in parent–child relationship), if any, are more prominent among daughters than sons. Previous studies also paid attention to the gender of siblings ( Chu et al., 2007 ; Zheng, 2015 ; Guo et al., 2018 ). Due to the strong son preference, having brothers (especially younger brothers) would reduce one’s opportunities in obtaining family resources, whereas having sisters (especially older sisters) would generally improve one’s well-being ( Chu et al., 2007 ; Zheng, 2015 ). For example, a study in Taiwanese families indicated that parents tended to discontinue the older daughters’ education and further encouraged them to make economic contributions to the whole family and their younger siblings (usually brothers) ( Chu et al., 2007 ). This led to more education of those with older sisters. For the well-being of children, brother(s) presence is an unfavorable factor, while sister(s) presence is a favorable factor ( Zheng, 2015 ). Considering the importance of siblings’ gender, this study also compared only children to children with siblings of different gender.

The Present Study

This study is designed to explore whether Chinese only children are more advantaged in emotional relationship with their parents compared to non-only children. Meanwhile, we also aim to compare only children with the firstborns, the middleborns, and the lastborns from multiple-child families to identify the birth-order effects. Furthermore, considering the gendered characteristics of family relationships in China, we will analyze whether children’s gender plays a moderating role in the association between the only child status and children’s parent–child relationship. Finally, we will compare only children to children with siblings of different gender (sibling-gender composition) regarding parent–child relationships.

The data used in this study derived from a national survey of school-going adolescents (junior high school students, 48.66% female, age range: 12 – 18; average age = 14.5 years). We used this dataset — China Education Panel Survey (2014) — based on the following reasons. First, adolescence is a period when people are undergoing critical changes in psychological, physical, and social development ( Ruhl et al., 2015 ). Influenced by these changes, during this period, children are more vulnerable to their social relationships with parent–child relationships being the most important. The quality of parent–child relationships during adolescence has been found to influence the adolescents’ developmental outcomes ( Ruhl et al., 2015 ; Chen, 2017 ; Li et al., 2018 ; Xu et al., 2019 ), with the influences persisting well into adulthood and later life ( Hair et al., 2008 ; Raudino et al., 2013 ). Second, the increased autonomy and shared-decision making with parents during adolescence enable adolescents to be more objective in their evaluations of their relationships with parents ( Ruhl et al., 2015 ). Third, the sampled adolescents in our study had a mean age of 14.5 years at 2014 meaning that they were born around 2000 when the one-child policy had been in force for almost 30 years. The phenomenon of one-child families had become a social norm ( Falbo and Hooper, 2015 ; Falbo, 2018 ) and a child-centered culture had taken shape in Chinese society. Parenting strategies were thus unique for this generation (the one-child policy began to be relaxed around 2013, see Jiang and Liu, 2016 ). Therefore, it is interesting to explore the only child effects on parenting strategies for this generation. Lastly, because Chinese culture continues to value education highly ( Huang and Gove, 2015 ), junior high school education, which plays an important role in transitioning to high school education, is emphasized by Chinese parents. Due to the highly competitive nature of attaining entrance to high schools in China, there is much stress placed on junior high school students to prepare for the graduation examination—that allows them to enter high-quality high schools ( Wu, 2015 ). In this process, parents also make their own contributions to their children such as providing harmonious family relationships. Furthermore, a junior high sample is more representative of Chinese adolescents in general because this educational stage is covered by the Nine-Year Compulsory Education ( Guo et al., 2019 ). Many adolescents could not go to high schools due to a lack of family resources ( Loyalka et al., 2013 ). The website of China’s Ministry of Education shows that in 2012, around 98% of primary graduates entered junior high schools, whereas only 88% of junior high graduates entered high schools [ MEPRC (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China), 2019 ]. Based on this, it is important to analyze parent–child relationships among junior high school students.

The following content of the paper is divided into four parts: (1) an introduction of materials and methods used in the study; (2) a report of the results from the descriptive analyses and the multilevel models; (3) a discussion of the empirical findings; (4) a summary of the study.

Materials and Methods

We used data from the baseline of China Education Panel Survey (CEPS 2014). CEPS is a nationally representative survey aiming at investigating how individual educational outputs are impacted by family, school, and community. Conducted by Renmin University of China, the data were gathered with a fourth-stage probability sampling design that randomly selected 19,487 students of grade 7 and grade 9 from 438 classes across 112 junior high schools in 28 counties (districts) of mainland China. Students along with their parents (19,487), teachers (438), and school faculty (112) constituted the final survey sample.

Five types of major questionnaires were used in the survey to collect information on students, their parents, homeroom teachers, main subject teachers (Chinese, Math, and English), and school administrators. The student questionnaires were completed by students collectively in the classroom and the parent questionnaires were completed by their corresponding parents or their main caregivers at home (copies of the parent questionnaires were taken home by the students). The study variables in this paper were mainly derived from the student questionnaires. All the survey data were collected using a paper/pencil measure. The data had a response rate of 98.7%.

We merged students’ data and parents’ data and 19,487 parent–child pairs were generated. One hundred and sixty five (0.85%) observations were deleted due to the missing information on dependent variables. In the remaining sample, most of our explanatory variables had a very low level of missing in formation (ranging from 0 to 2.5%) with parental age at birth of the respondent child (around 25% missing) and gender of siblings (around 10% missing) being the exceptions. Apart from parental age at birth and gender of siblings, the missing percentage for the whole sample were 5.35%. To avoid losing too many observations, we created a “missing” category for the variables with high rate of missing information (will elaborate later in the “measure” part). Thus, the final analytical sample was 18,445.

Dependent Variables

Parent–child relationship.

Research has measured parent–child relationships in a variety of ways. Some studies employed parental verbal and physical interactions with children, parental control, and prenatal supportiveness through specific and multi-dimensional items to measure parent–child relationships ( Pritchett et al., 2011 ; Li et al., 2015 ; Chen et al., 2018 ; Xu et al., 2019 ; Ma et al., 2020 ). Others utilized a single and general item measuring parent–child relationships ( Videon, 2005 ; Damsgaard et al., 2014 ). For example, Videon (2005) operationalized parent–child relationship using a single question: “Overall, are you satisfied with your relationship with your mother (father)?” Damsgaard et al. (2014) employed the question: “how easy is it for you to talk to your mother/father about things that really bother you?” In our study, we employed the later practice: capturing the quality of parent–child relationship with a single general question. Meanwhile, because mothers and fathers tend to play different roles in parenting activities ( Liu, 2020 ), and the child’s development is usually influenced by his/her same-sex parent ( Ohannessian, 2012 ), it is necessary to measure father–child and mother–child relationship separately.

In the present study, parent–child relationships were assessed with one item about each parent. On the student questionnaire, children were asked to rate the relationship with their parents: how is the general relationship with your mother/father? Responses included “not close (2.4% for mother–child relationship and 4.3% for father–child relationship),” “moderate (24.21% for mother–child relationship and 33.28% for father–child relationship),” and “close (73.40% for mother–child relationship and 62.42% for father–child relationship).” We created a three-category ordinal variable for mother–child closeness and father–child closeness (0–2, a higher value indicates closer parent–child relationship), respectively. See Table 1 for the measurements of dependent variables.

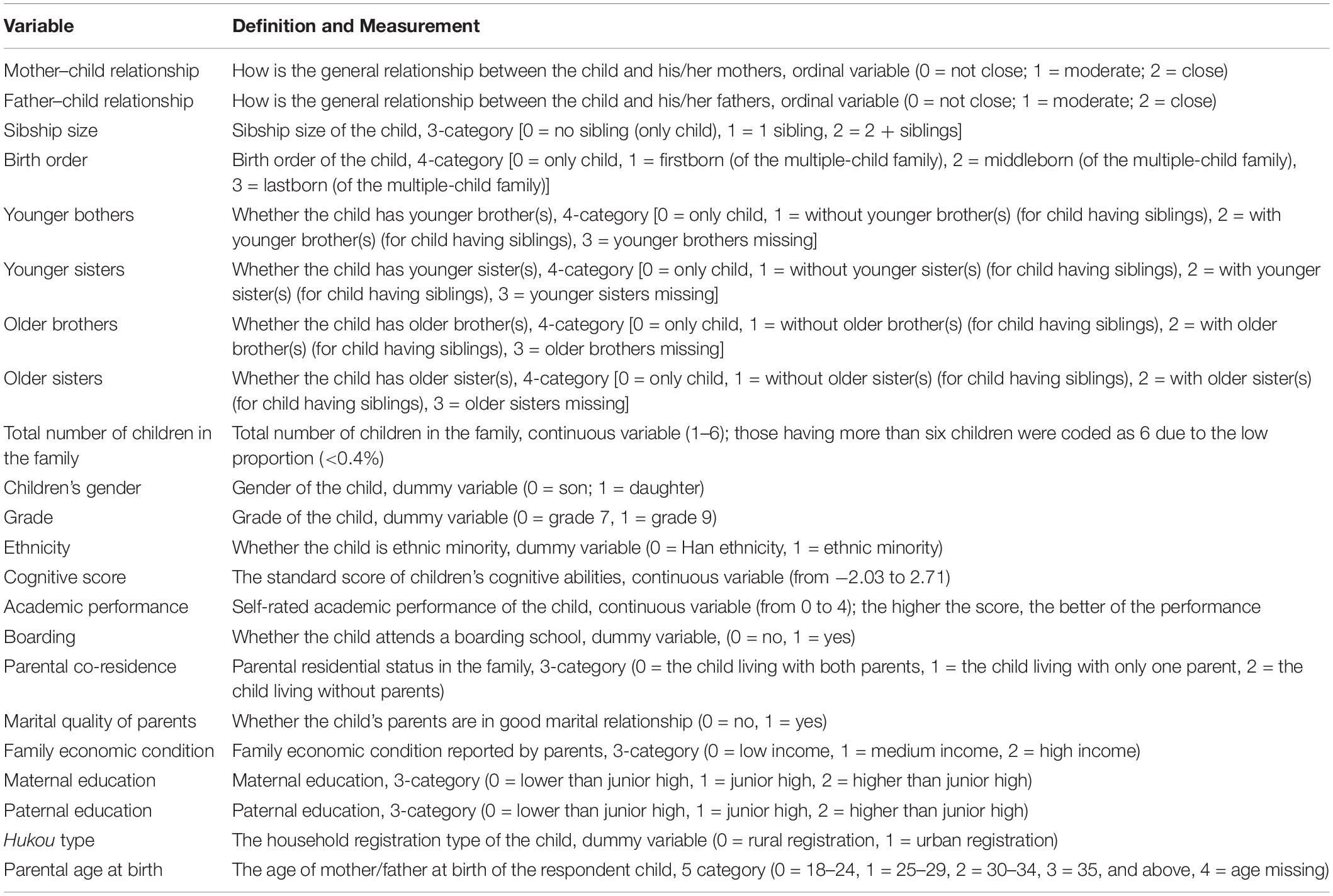

Table 1. Definitions and measurements of the study variables.

Key Independent Variables

Our key independent variable is the sibling status. Based on our research objectives, various sibling-related variables were produced. To compare only children with children having siblings, we created a three-category variable named sibship size with only children as the reference group and children having one sibling and children having two or more siblings as the other two groups. We combined the children with two siblings and more into one category (2 + siblings) because there were only five percent of the students having three or more siblings. In addition, to compare only children with children of different birth order from multiple-child families, we created a four-category variable named birth order. Specifically, only children were coded as 0 (reference category); firstborns, middleborns, and lastborns from multiple-child families were coded as 1, 2, and 3, respectively. To be clear, firstborns, middleborns, and lastborns were defined by the birth order of children from multiple-child families: firstborns were children with only younger siblings; middleborns were children who had both younger siblings and older siblings; lastborns were children with only older siblings. See Table 1 for the definitions and measurements of the study variables. At last, to compare only children with children having siblings of different gender, we created another four variables with each having four categories. For example, the variable “younger brothers” indicated whether the child had younger brothers (0 = only child, 1 = without younger brothers, 2 = with younger brothers, 3 = younger brothers missing). The creations of the other three variables (“younger sisters,” “older brothers,” and “older sisters”) followed the same pattern.

Potential Moderator

To test whether the effects of only child status on parent–child relationship depend on children’s gender, this study set children’s gender as the moderating variable (0 = son, 1 = daughter).

We controlled for a variety of covariates in the models. Covariates included adolescents’ demographics (grade and ethnicity), academic characteristics (cognitive score and academic performance), family dynamics (boarding school attendance, parental co-residence, and parental marital quality), family SES (family economic condition, parental education, hukou type), and parental age at birth of the respondent child. Children’s grade (grade 7 and grade 9) is a reflection of both children’s age and birth cohort which could influence parent–child closeness as well as sibship size. Children’s academic characteristics were also found to predict parent–child relationship ( Sharma and Vaid, 2005 ), especially in the Chinese culture highly valuing children’s education ( Huang and Gove, 2015 ). According to family systems theory, family structure (boarding school attendance and parental co-residence) and marital relationships were strong predictors of parent–child relationship ( Dinisman et al., 2017 ; Yoo, 2020 ). Children’s ethnicity and family SES could affect not only parent–child closeness but also sibship size ( Zhang, 2012 ; Piotrowski and Tong, 2016 ; Weng et al., 2019 ). The one-child policy were implemented more rigorously in the Han ethnicity than in minority ethnicities and in urban families than in rural families, we therefore included ethnicity and the hukou type ( Weng et al., 2019 ). Research has consistently found that with the increase of parental education, the number of children declines ( Piotrowski and Tong, 2016 ) and the parent–child relationship improves ( Zhang, 2012 ). We also controlled for parental age at birth of the surveyed child because it was expected to influence both parent–child relationship and sibship size. Because parental age at birth had a high proportion of missing values (24.61%), we included “age missing” along with other values in the model. Refer to Table 1 for the specific measurements.

Analytical Strategy

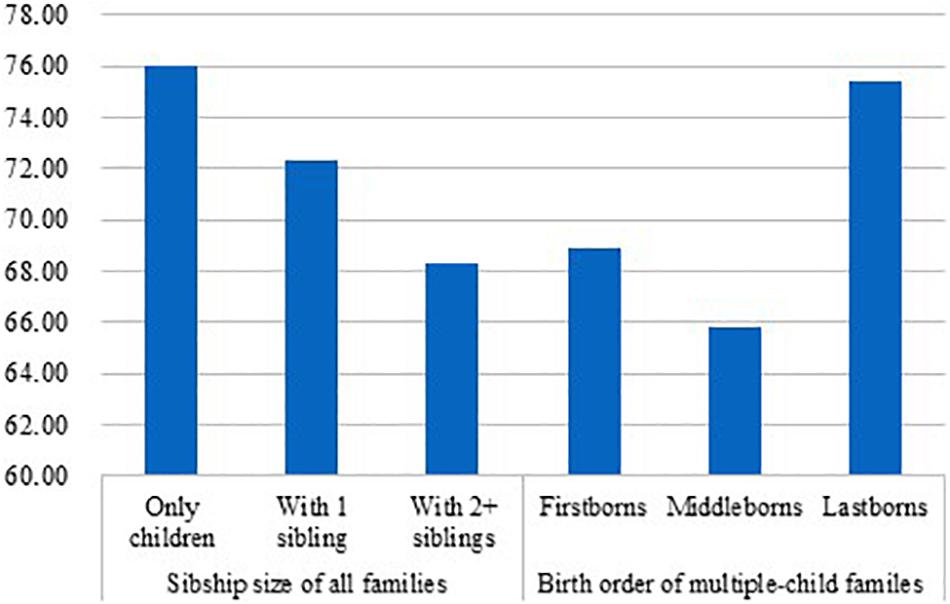

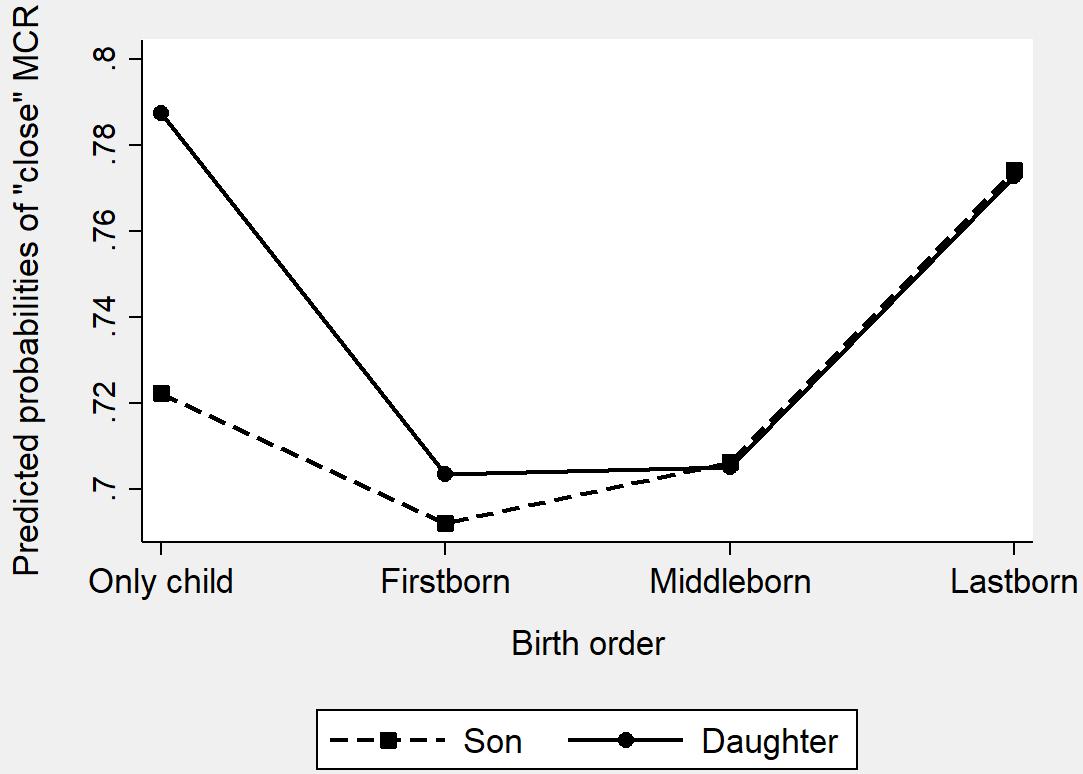

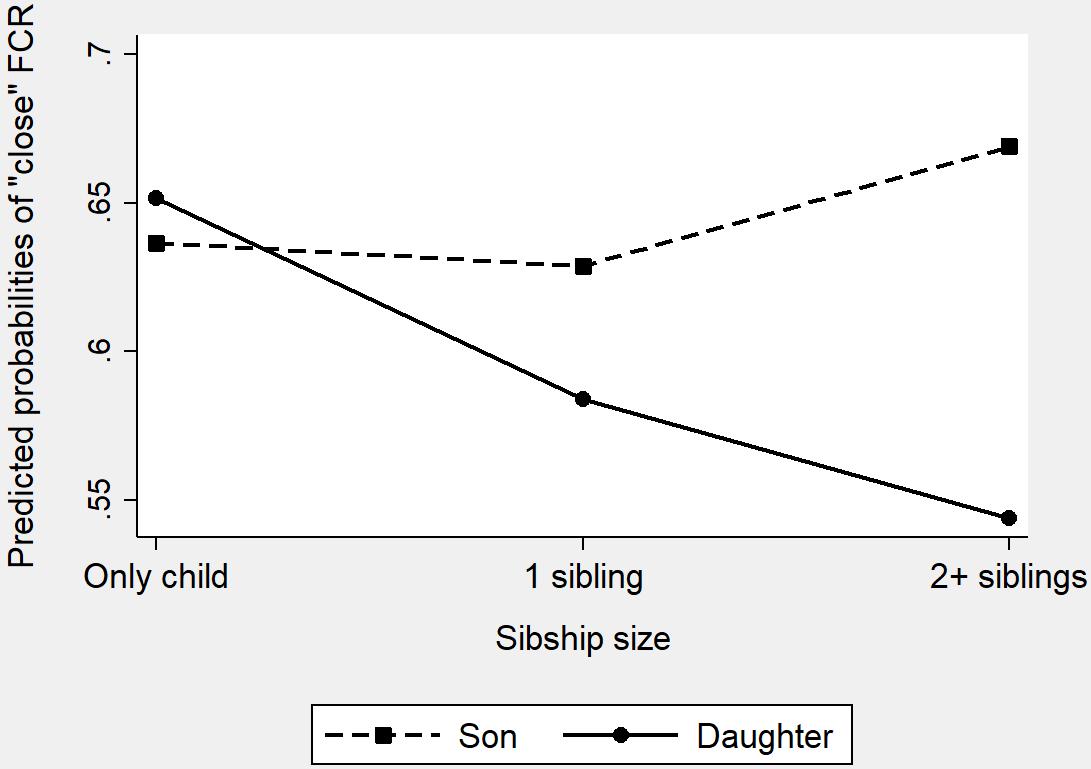

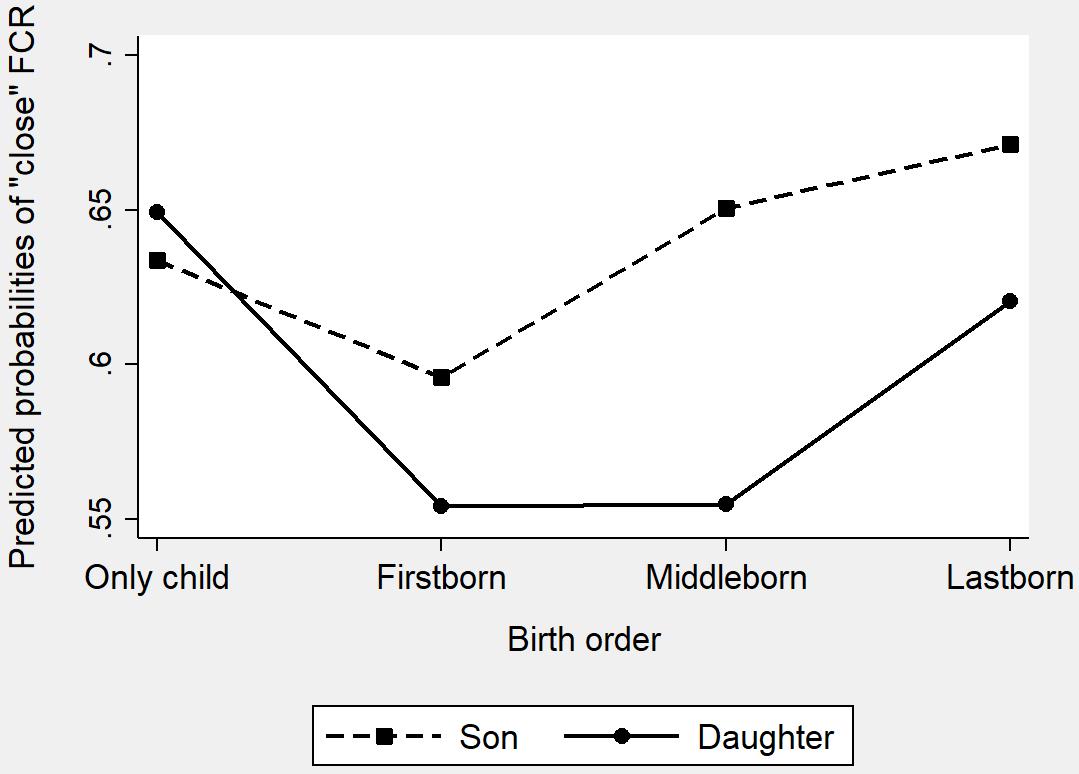

We started the analyses by reporting the sibling information of the analytical sample ( Table 2 ) and the sample characteristics in the full, only child, and non-only child sample ( Table 3 ). Meanwhile, we displayed the percent of “close” mother–child and father–child relationships by children’s sibship size and birth order ( Figures 1 , 2 ). In the next step, given the ordinal nature of the dependent variables, we employed two-level ordered logistic models to estimate mother–child closeness and father–child closeness ( Tables 4 , 5 ). Two-level models were used due to the nested structure of the data (students were nested in schools).

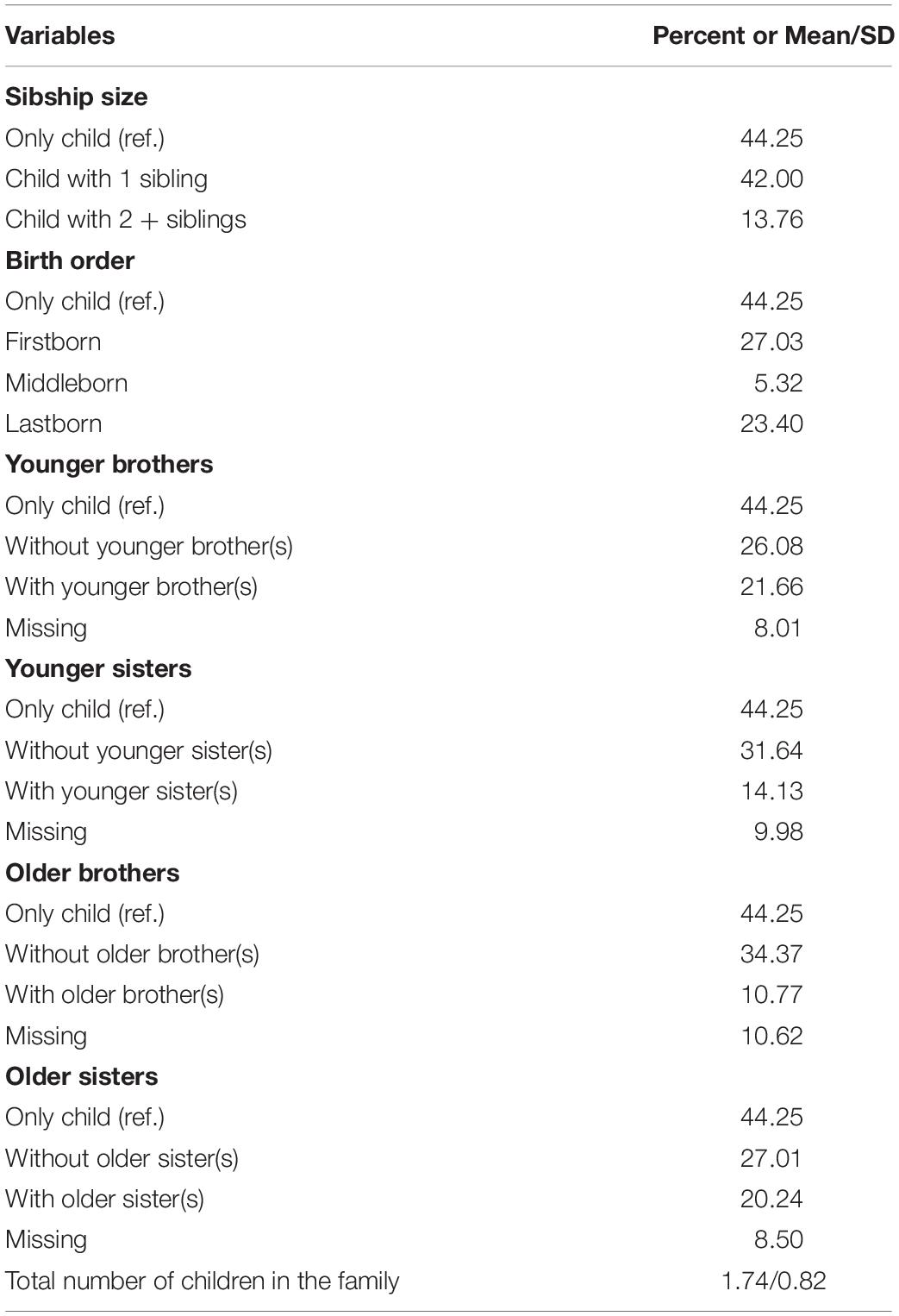

Table 2. Sibling information.

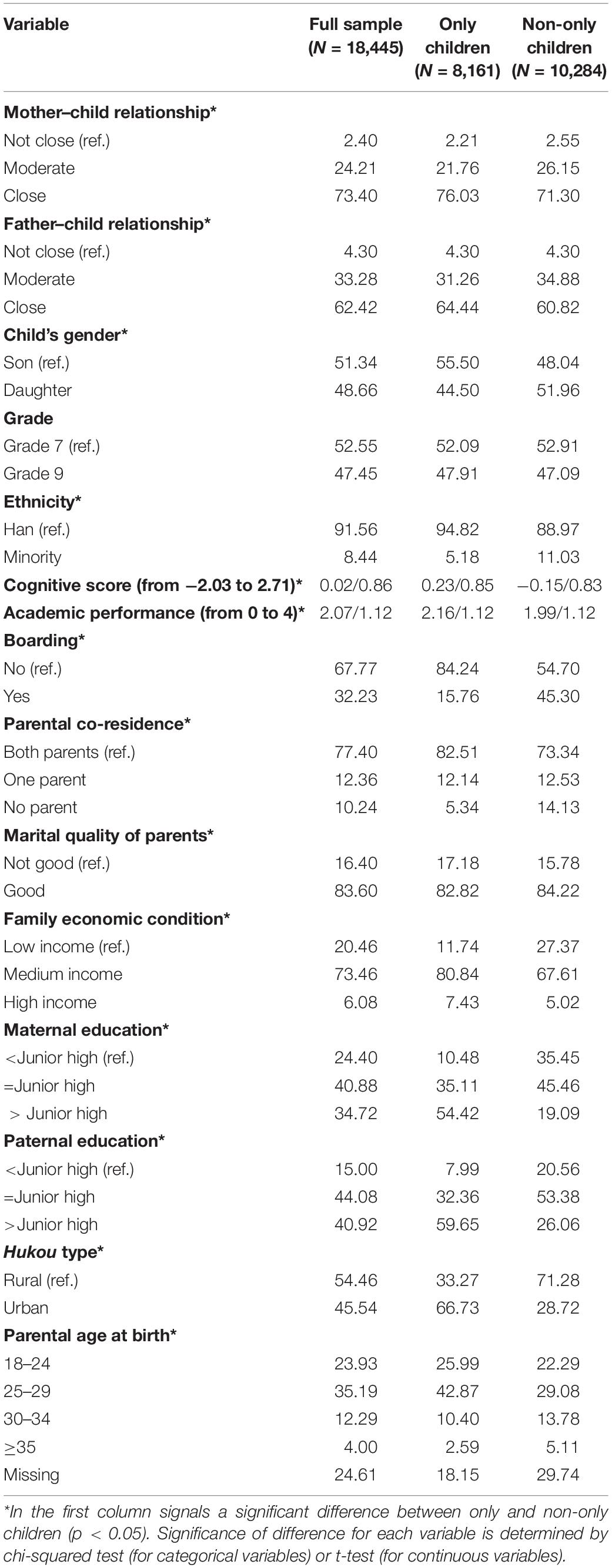

Table 3. Sample characteristics (Percent or Mean/SD).

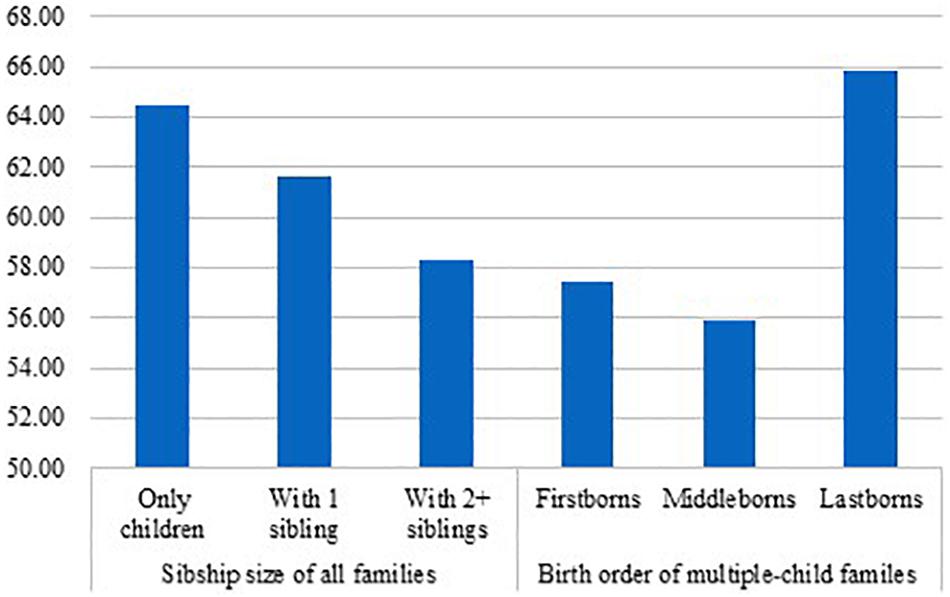

Figure 1. Percent of a “close” mother–child relationship by sibship size and birth order (firstborns do not consist of only children).

Figure 2. Percent of a “close” father–child relationship by sibship size and birth order (firstborns do not consist of only children).

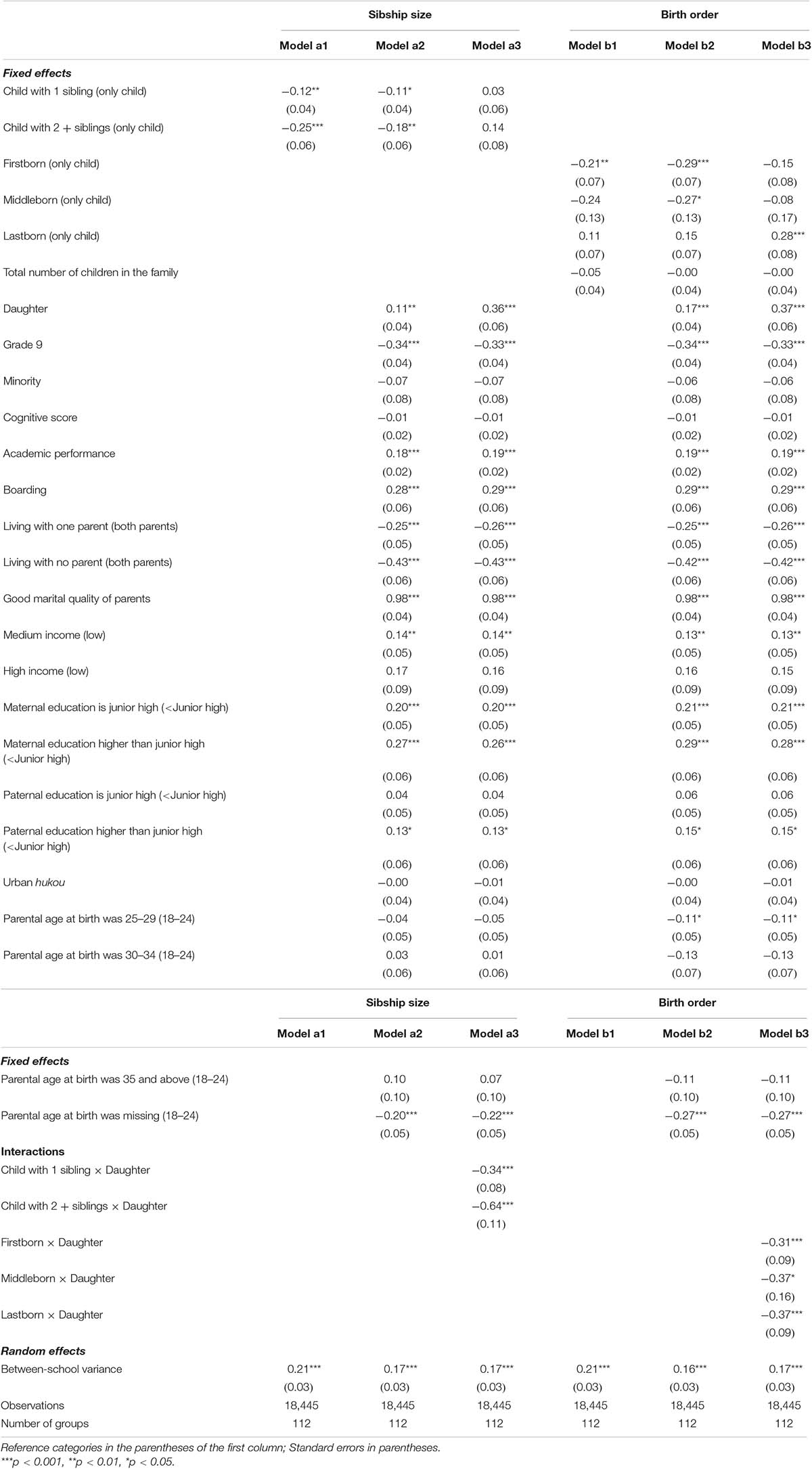

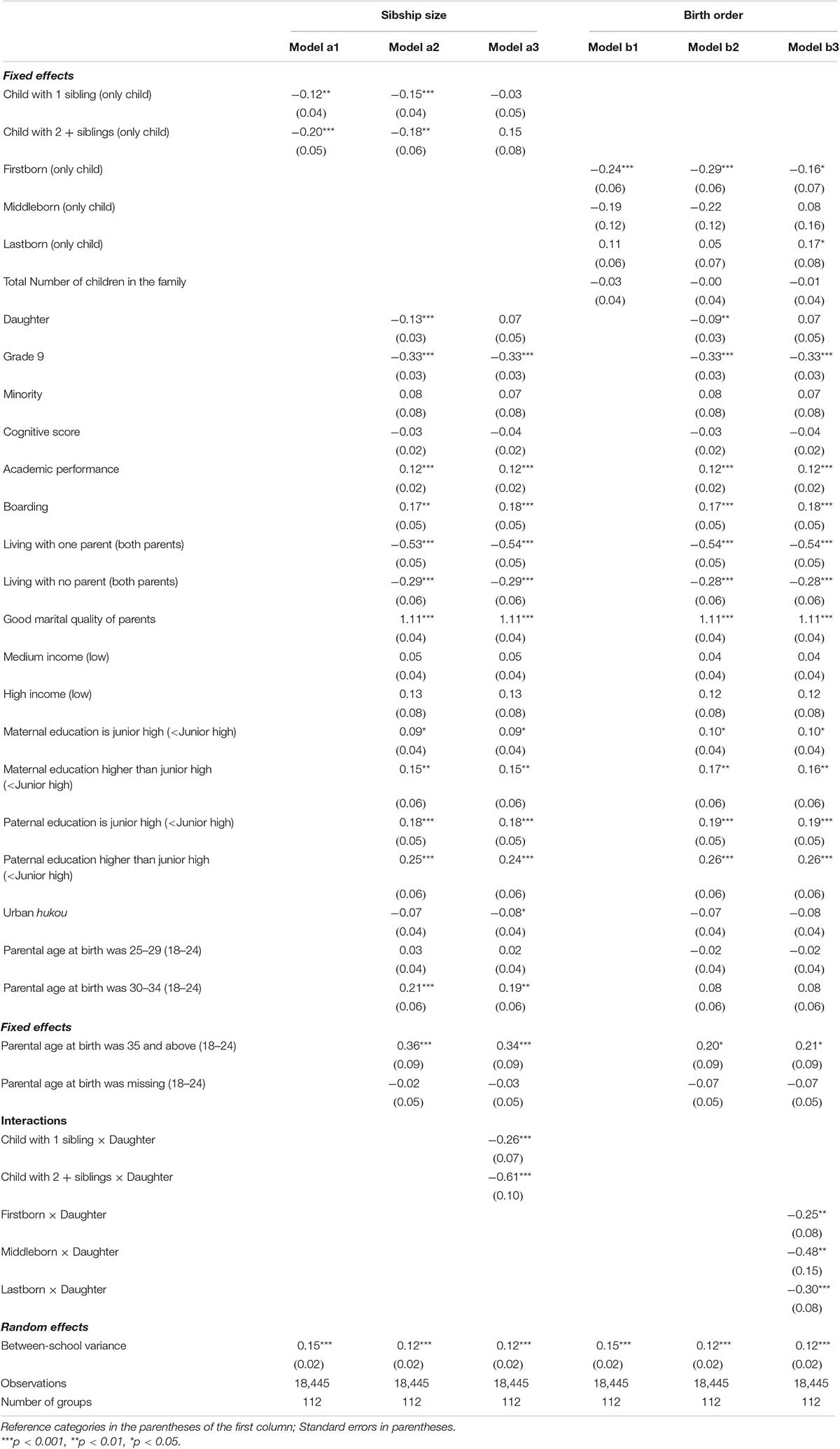

Table 4. Two-level ordered logistic models estimating mother–child closeness ( N = 18445).

Table 5. Two-level ordered logistic models estimating father–child closeness ( N = 18,445).

Descriptive Analyses

Table 2 reports the sibling information of our analytical sample. Information in Table 2 indicates that modern Chinese families have a very small family size with one-child and two-child families accounting for a large proportion (more than 80%). Specifically, only children accounted for almost half of the sampled children (44.25%); children with only one sibling accounted for 42% of the full sample; children with two or more siblings held a very low proportion of 14%. Of the analytical children, around 27% were firstborns, 5% were middleborns, and 23% were lastborns. Among our sampled children, those having younger brothers held the largest proportion (21.66%) and those having older sisters accounted for the second largest proportion (20.24%). Only 10.77% of the children had older brothers. This is perhaps because most rural parents were subject to the one-and-a-half-child policy: rural couples whose first child was a daughter were allowed to have a second child, whereas those with a son as the first child were not allowed to have another child ( Jiang and Liu, 2016 ). The mean number of children for each household in our sample was only 1.74.

Table 3 reports the sample characteristics. In addition to showing the sample characteristics in the full sample, Table 3 also displays the characteristics by children’s only child status. Meanwhile, the chi-squared test (for categorical variables) or t -test (for continuous variables) was employed to decide if the difference between only children and non-only children were significant. As shown in Table 3 , most junior-high-school students had a close parent–child relationship (73.40% for mother–child relationship and 62.42% for father–child relationship). Chi-squared tests show that only children were significantly different from non-only children in three levels of mother–child relationship (χ 2 = 52.23, df = 2, p = 0.000) and father–child relationship (χ 2 = 27.47, df = 2, p = 0.000). To test whether only children were significantly different from non-only children in reporting “close” parent–child relationships, we combined “not close” and “moderate” into one category. After the combination, chi-squared tests of the two levels of parent–child relationships (“not close-moderate combination” and “close”) show that compared to non-only children (71.30%), only children (76.03%) were more likely to report “close” relationships with their mothers (χ 2 = 52.08, df = 1, p = 0.000); compared to non-only children (60.82%), only children (64.44%) were also more likely to report “close” relationships with their fathers (χ 2 = 25.39, df = 1, p = 0.000). In addition, only children had significantly higher cognitive score (0.23 for only children and −0.15 for non-only children, t = 30.90, df = 18,443, p = 0.000) and reported better academic performance (2.16 for only children and 1.99 for non-only children, t = 10.25, df = 18,443, p = 0.000) than did non-only children. Non-only children were more likely to attend a boarding school than only children (χ 2 = 1,800, df = 1, p = 0.000). Regarding family background, only children were more likely to be born in high-income families (χ 2 = 46.19, df = 1, p = 0.000), having parents of more educated (maternal education: χ 2 = 2,500, df = 1, p = 0.000; paternal education: χ 2 = 2,100, df = 1, p = 0.000), and having higher probability of living with both parents (χ 2 = 219.06, df = 1, p = 0.000). Finally, due to the more rigorous implementation of the OCP and the more modern culture in urban areas than in rural areas, only children were significantly different from non-only children in hukou type (urban hukou accounted for 66.73% among only children and only 28.72% among non-only children, χ 2 = 2,700, df = 1, p = 0.000). Overall, only children were more advantaged in terms of both parent–child relationship and background characteristics than non-only children.

Figures 1 , 2 show the percent of “close” mother–child relationship and “close” father–child relationship, respectively, by sibship size and birth order. For “close” mother–child relationship ( Figure 1 ), significant difference was not only found between only children and children with two or more siblings (only children: 76.03%, children with two or more siblings: 68.28%, χ 2 = 60.73, df = 1, p = 0.000) but also found between only children and children having only one sibling (only children: 76.03%, children with 1 sibling: 72.30%; χ 2 = 29.00, df = 1, p = 0.000). Further, only children were also significantly more likely to report “close” mother–child relationships than firstborns (firstborns: 68.87%, χ 2 = 81.10, df = 1, p = 0.000) and middleborns (middleborns: 65.78%, χ 2 = 49.01, df = 1, p = 0.000), but no significant difference was observed between only children and lastborns (lastborns: 75.37%, χ 2 = 0.67, df = 1, p = 0.412). For “close” father–child relationship ( Figure 2 ), the pattern was similar. First, only children were significantly more likely to report “close” father–child relationship than children with one sibling (only children: 64.44%, children with 1 sibling: 61.66%; χ 2 = 13.22, df = 1, p = 0.000) and children with two or more siblings (only children: 64.44%, children with two or more siblings: 58.27%; χ 2 = 31.57, df = 1, p = 0.000). Turing to birth order, only children were also more likely to report “close” father–child relationship than firstborns (firstborns: 57.46%, χ 2 = 63.87, df = 1, p = 0.000) and middleborns (middleborns: 55.91%, χ 2 = 27.55, df = 1, p = 0.000). However, no significant difference was detected between only children and lastborns (lastborns: 65.82%, χ 2 = 2.38, df = 1, p = 0.123).

Multivariate Analyses

Mother–child closeness.

Table 4 shows the coefficients of two-level ordered logistic models estimating mother–child closeness. Model a1 and Model b1 were designed to test the effects of children’s sibship size and birth order on mother–child closeness without controlling for covariates, respectively. Sibship size and birth order were not included in the models simultaneously in order to avoid multi-collinearity because the two variables shared a same reference group (only children). Model a2 and Model b2 were models estimating the net effects of sibship size and birth order, respectively, with other things being equal (all the covariates were controlled). It is worth noting that, in the birth order model (Model b2), we controlled for the total number of children in the family to capture the net effects of birth order. Model a3 and Model b3 were interaction models designed to test the moderating effects of children’s gender on the effects of sibship size and birth order, respectively.

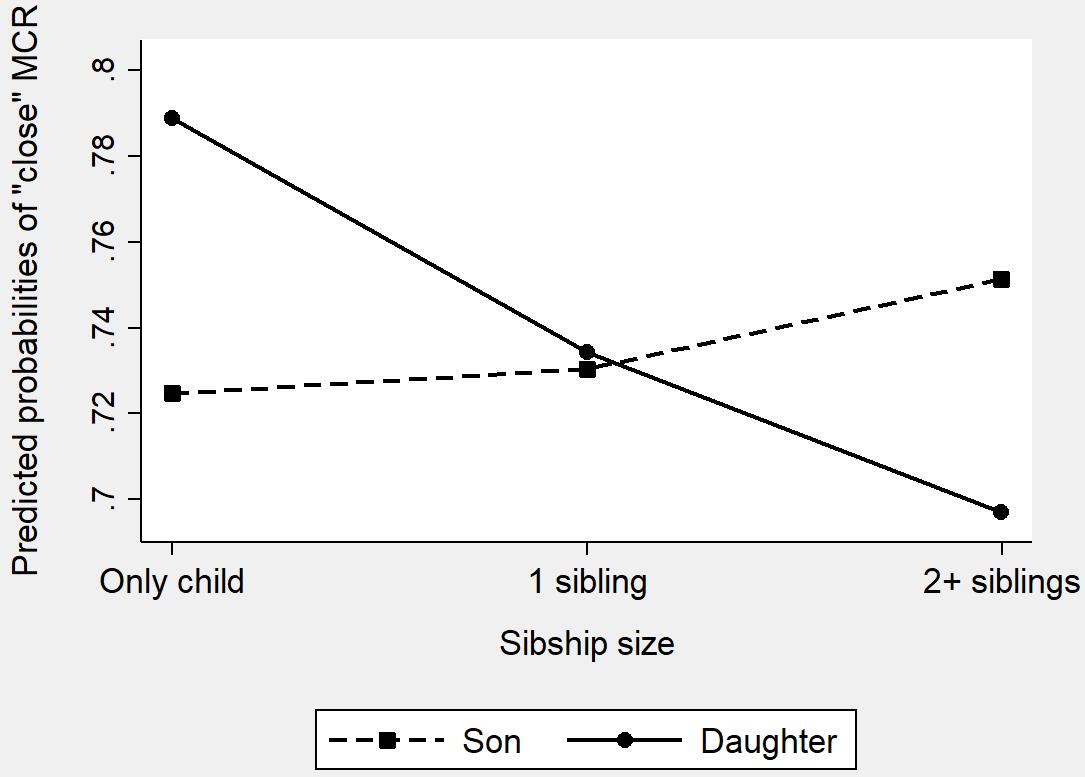

In Model a1, the significantly negative coefficients of one-sibling child and two-or-more-sibling child indicate that the presence of sibling(s) was disadvantaged for children. We then successively added the control variables. In Model a2, with all the covariates being controlled, the negative effects of sibship size dropped in the magnitude but still remained significant. We found that the sibship size effects were largely confounded by family SES (results not shown). Other things being equal, compared to only children, children with one sibling were 10% [1- exp (−0.11), p = 0.016] less likely to report a close relationship with their mothers; Children with two or more siblings were 16.5% [1- exp (−0.18), p = 0.004] less likely to report a close mother–child relationship. In addition, the significantly positive coefficient of children’s gender (β = 0.11, p = 0.001) implied that daughters were more likely to report a close mother–child relationship than sons. Moving to Model a3, the coefficients of the interaction terms are significantly negative (β 1 sibling × daughter = −0.34, p = 0.000; β 2 + siblings × daughter = −0.64, p = 0.000) indicating that the effects of sibship size were significantly different between daughters and sons. We visually displayed the interaction effects in the form of predicted probabilities (for “close” mother–child closeness) in Figure 3 . Figure 3 clearly shows that, the changing directions of the solid line (representing daughter) and the dash line (representing son) were different. Larger sibship size reduced daughters’ probabilities of having a close relationship with mothers by a great degree whereas slightly increased sons’ probabilities of attaining such relationship. In other words, the benefits of being an only child is mainly reflected on daughters in the Chinese context.

Figure 3. Predicted probabilities of a “close” mother–child relationship by sibship size and children’s gender (MCR: mother-child relationship).

Turning to the birth-order models. In Model b1, without controlling for other variables, firstborns were found to be less likely to form a close mother–child relationship compared to only children. In Model b2, net of all the other factors, compared to only children, firstborns and middleborns were 25% [1- exp (−0.29), p = 0.000] and 24% [1- exp (−0.27), p = 0.041] less likely, respectively, to have a close mother–child relationship. Finally, the coefficient of lastborns is positive and marginally significant (β = 0.15; p = 0.052) suggesting lastborns were not disadvantaged compared to only children in mother–child closeness. Turning to Model b3 with interaction terms, we found a significant joint effects of birth order with children’s gender. Figure 4 clearly shows the interaction information of Model b5: daughters as only children had a significantly higher probability to enjoy a close mother–child relationship than sons as only children. Last daughters and sons had the same probability to enjoy a close mother–child relationship. Firstborns and middleborns (both daughters and sons) were least likely to have a close mother–child relationship.

Figure 4. Predicted probabilities of a “close” mother–child relationship by birth order and children’s gender (MCR: mother-child relationship).

Father–Child Closeness

Table 5 shows the coefficients of two-level logistic regression estimating father–child closeness. Model a1 and Model b1 were designed to test the sibship-size effects and birth-order effects on father–child closeness without controlling for other variables, respectively. Model a2 and Model b2 were models testing the net effects of sibship size and birth order (all covariates were controlled). Similar to the estimates of mother–child relationship, sibship size and birth order were not included simultaneously to avoid multi-collinearity. Model a3 and Model b3 were interaction models testing whether children’s gender moderated the sibship-size effects and birth-order effects, respectively.

In Model a1, the coefficients of sibship size were significantly negative suggesting that compared to only children, children with siblings experienced a declined odds of having a close father–child relationship. We then successively added covariates in the model with Model a2 including all variables. Holding other things consistent, having one sibling and two or more siblings reduced the odds of enjoying a close father–child relationship by 14% [1-exp (−0.15), p = 0.000] and 16% [1-exp (−0.18), p = 0.002], respectively. It is worth noting the coefficient of children’s gender: although daughters were more likely (β = 0.11, p = 0.001) to have a close mother–child relationship than sons (see Model a2 in Table 4 ), they were less likely (β = −0.13, p = 0.000) to have a close father–child relationship. Turning to Model a3, the significant coefficients of the interaction terms suggest that children’s gender and sibship size jointly influenced father–child relationship (β 1 sibling × daughter = −0.26, p = 0.000; β 2 + siblings × daughter = −0.61, p = 0.000). We visually displayed the interaction information of Model a3 in Figure 5 . Figure 5 clearly shows that daughters’ probabilities of having a “close” father–child relation declined with the increase of sibship size and only daughters have the highest probabilities. Sons, on the contrary, experienced a slightly increase in father-son closeness as their sibship size rose. Among non-only children (children with 1 sibling or 2+ siblings), sons had higher probabilities of reporting a close father–child relationship than did daughters, whereas among children without siblings, daughters had higher probabilities in reporting a close relationship with their fathers than did sons. Figure 5 suggests that daughters, rather than sons, benefit from being only children.

Figure 5. Predicted probabilities of a “close” father–child relationship by sibship size and children’s gender (FCR: father-child relationship).

Model b1 (only including birth order) suggests that only children were significantly more likely to have close father–child relationships than did firstborns. In Model b2, with all the covariates being controlled, firstborns were 25% [1-exp (−0.29), p = 0.000] less likely to report a close father–child relationship. However, there was no significant difference between only children and middleborns or lastborns. Model b3 includes the interactions of children’s gender and birth order to test whether birth order influenced father–child relationships differently for daughters and sons. The coefficients of the interactions were significantly negative suggesting daughters and sons showed different patterns in the association between birth order and father–child relationship. We displayed the interaction information of Model 4 in Figure 6 . Figure 6 clearly shows that, for sons, being the lastborns of multiple-child families was most beneficial. This is probably due to the son preference: the youngest sons in the families were usually born in the situation that fathers were dissatisfied with the number of sons and their births would make up for it ( Basu and De Jong, 2010 ). Therefore, the births of younger sons would bring about more satisfactions than that of older sons. However, for daughters, the situation is distinct: being the only child was most beneficial. This is also an indirect reflection of son preference: only when there were no siblings to compete for family resources will daughters receive more attention from parents in the Chinese families.

Figure 6. Predicted probabilities of a “close” father–child relationship by birth order and children’s gender (FCR: father-child relationship).

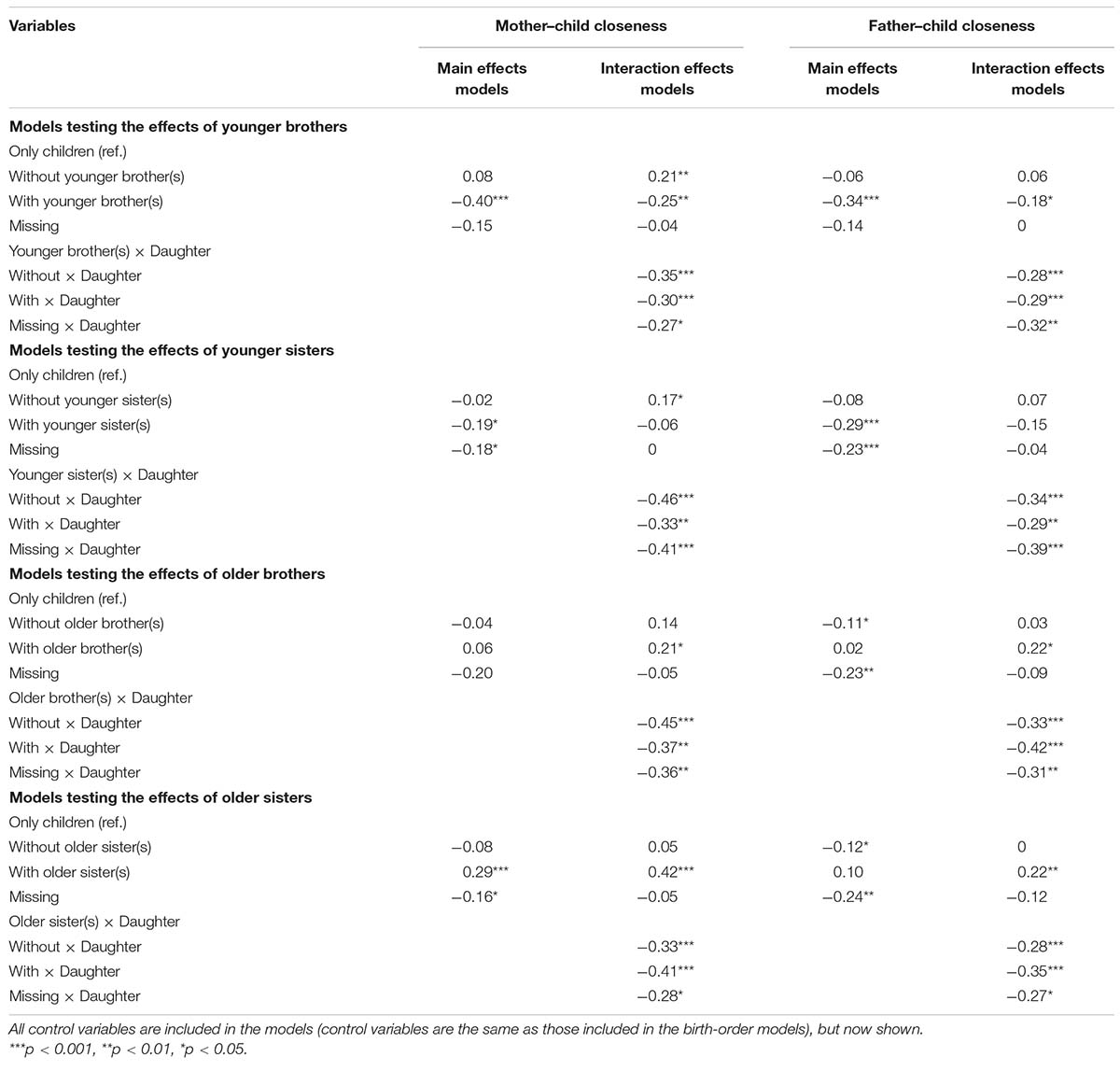

The Presence of Siblings of Different Gender

To compare only children with children having siblings of different gender, we ran a series of additional models. See Table 6 .

Table 6. Effects of younger brothers, younger sisters, older brothers, and older sisters.