- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- The Lit Hub Podcast

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- I’m a Writer But

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Behind the Mic

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- Emergence Magazine

- The History of Literature

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

The Last Essay I Need to Write about David Foster Wallace

Mary k. holland on closing the “open question” of wallace’s misogyny.

Feature photo by Steve Rhodes .

David Foster Wallace’s work has long been celebrated for audaciously reorienting fiction toward empathy, sincerity, and human connection after decades of (supposedly) bleak postmodern assertions that all had become nearly impossible. Linguistically rich and structurally innovative, his work is also thematically compelling, mounting brilliant critiques of liberal humanism’s masked oppressions, the soul-killing dangers of technology and American narcissism, and the increasing impotence of our culture of irony.

Wallace spoke and wrote movingly about our need to cultivate self-awareness in order to more fully see and respect others, and created formal methods that construct the reader-writer relationship with such piercing intimacy that his fans and critics feel they know and love him. A year after his death by suicide, as popular and critical attention to him and his work began to build into the industry of Wallace studies that exists today, he was first outed as a misogynist who stalked, manipulated, and physically attacked women.

In her 2009 memoir, Lit , Mary Karr spends less than four pages narrating the several years in which Wallace pursued her, leading to a brief romantic relationship that ended in vicious arguments and “his pitching my coffee table at me.” Unlike her accounts of the relationship nearly a decade later, Karr’s tone here notably remains clever and humorous throughout. She also follows each disclosure of Wallace’s ferocity with a confession of her own regrettable behavior: regarding his “temper fits” she admits to “sentences I had to apologize for” and assures us—twice—that “no doubt he was richly provoked.” After describing the coffee-table incident, she notes parenthetically that “years later, we’ll accept each other’s longhand apologies for the whole debacle,” as if having a piece of furniture thrown at you makes you as guilty as having thrown it.

Three years later D.T. Max published his biography of Wallace, in which he divulged more shocking details about the relationship with Karr—that Wallace tried to buy a gun to kill her husband, that he tried to push her from a moving car—while also dropping enough details about Wallace’s sex life and professed attitudes toward women to make him sound like one of his own hideous men. Wallace called female fans at his readings “audience pussy”; wondered to Jonathan Franzen whether “his only purpose on earth was ‘to put my penis in as many vaginas as possible’”; picked up vulnerable women in his recovery groups; admitted to a “fetish for conquering young mothers,” like Orin in Infinite Jest ; and “affected not to care that some of the women were his students.”

In a 2016 anthology dedicated to the late author, one of those students, Suzanne Scanlon, published a short story about a student having a manipulative, emotionally abusive sexual affair with her professor (called “D-,” “Author,” and “a self-identified Misogynist”), using characteristic formal elements of “Octet” and “Brief Interviews” and dominated by the narrative voice popularized by David Foster Wallace.

None of these accounts had any visible impact on fans’ or readers’ love of Wallace’s writing or on critics’ readings and opinions of his work. Rather, one writer, Rebecca Rothfeld, confessed in 2013 that Max’s record of (some of) Wallace’s misogynistic acts and statements could not shake her “faith in [his] fundamental goodness, intelligence, and likeability” because his “work seemed more real to me than his behavior did.” Critic Amy Hungerford took the opposite stance in 2016, proclaiming her decision to stop reading and teaching Wallace’s work, but without mentioning his abusive treatment of women or the question of how that behavior presses us to re-read the same in his work.

Another writer, Deirdre Coyle, explained her discomfort at reading Wallace not in terms of the author’s own behavior—which she gives no sign of being aware of—but because of sexual and misogynistic violence perpetrated on her by men she sees as very much like Wallace (“Small liberal arts colleges are breeding grounds for these guys”) and in terms of patriarchy in general (“It’s hard to distinguish my reaction to Wallace from my reaction to patriarchy.” Any woman who has been violated, talked over, and condescended to by this kind of man, the kind who thinks his pseudo-feminism allows him to enlighten her about her own experiences of male oppression and sexual violation, cannot help but sympathize with Coyle.

But in rejecting Wallace because of other men’s sexual violence and misogyny in general, she shifts the argument away from questions about how these function in the fiction and how Wallace’s biography might force us to re-read that fiction, and allows for the kind of circular rebuttal that a (male) Wallace critic offered a year later: not all male readers of Wallace are misogynists; therefore, women should listen to the good ones and read more Wallace; let me tell you why.

These pre-#MeToo reactions to Karr’s and Max’s reports of Wallace’s abuse of women clarify what is at stake as readers, critics, and teachers consider this biographical information in the context of Wallace’s work. For, while Wimsatt and Beardsley’s argument against the intentional fallacy is compelling and important, its goal is to protect the sanctity of the text against the undue influence of our assumptions about the person who wrote it. Arguments defending the importance of Wallace’s beautiful empathizing fiction in spite of his abuse of women threaten to do the opposite.

Like Rothfeld, whose admiration for Wallace’s fiction renders his own misogynistic acts less “real,” David Hering argues that “the biographical revelation of unsavoury details about Wallace’s own relationships” leads to an equation between Wallace and misogyny that “does a fundamental disservice to the kind of urgent questions Wallace asks in his work about communication, empathy, and power”—as if Wallace’s real abuse of real women is not worth contemplating in comparison with his writing about how fictional men treat fictional women. Hering’s use of the euphemism “unsavoury” to describe behavior ranging from exploitation to physical attacks, like his description of Wallace’s work regarding gender as “troublesome,” illustrates another widespread problem with nearly all critical treatments of this topic so far: an unwillingness to say, or perhaps even see, that what we are talking about in the fiction and in the author’s life is gender-motivated violence, stalking, physical abuse, even, in the case of Karr’s husband, plotting to murder.

In the wake of the October 2017 resurgence of Burke’s #MeToo movement, we see a curious split between Wallace-studies critics and others in their reactions to these allegations. Not only does Hering’s response downplay the severity of Wallace’s behavior and its relevance to his work; it also asserts Hering’s “belief” that Wallace’s work “dramatize[s]” misogyny, rather than expressing it—without offering a text-based argument or pointing to the critical work that had already done this analysis and found exactly the opposite to be true.

He also relies on a technique used by memoirists, bloggers, and critics alike in their attempts to save Wallace from his own biography: he converts an example of male domination of women into a universal human dilemma, erasing the elements of gender and power entirely, by reading Wallace’s silencing of his female interviewer’s voice in Brief Interviews as “embody[ing] the richness of Wallace’s work—its focus on the difficulty and importance of communication and empathy, and its illustration of the poisonous things that happen when dialogue breaks down.” Such a reading ignores the fact that when dialogue breaks down between an entitled man and a pressured woman , the things that can happen go beyond metaphorically poisonous to physically sickening and injurious—as so many of the stories in that collection illustrate.

Given the same platform and the same task—celebrating Wallace around what would have been his 56th birthday—critic Clare Hayes-Brady offered “Reading David Foster Wallace in 2018,” mere months after the social media flood of women’s testimonies about sexual violence had begun. It does not mention #MeToo or the public allegations that had been made about Wallace, raising the question of what “in 2018” refers to. When asked several months later “what’s changed?” in Wallace studies, after the public (but not critical) backlash had begun, Hayes-Brady falls back on the same generalizing technique used by Hering. She reframes accusations of misogyny as an entirely academic development, beneficial to Wallace studies and unrelated to #MeToo outcry against perpetrators of sexual violence (“a coincidence of timing”). She equates “flaws in his writing both technical and also moral and ethical,” as if women had been up in arms across Twitter over Wallace’s exhausting sentence structures.

When directly asked if Wallace was a misogynist, she replies “yes, but in the way everyone is, including me,” as if we neither have nor need a separate word for men who do not just live unavoidably in our misogynistic culture but also willfully perpetrate selfish, cruel, and violent acts of misogyny against women. That is, rather than responding humanely to indisputable evidence that our beloved writer was not the saint he would have liked us to think he was (and that we would have liked to believe him to be), Wallace critics—including me, in my silence at that time—refused to allow #MeToo to force the reckoning that was so clearly required. We did so by denying the relevance of his personal behavior to his fiction and to our work, or—worse—by participating in that age-old rape culture enabler: refusing to believe women’s testimony.

Those outside literary studies reacted quite differently to the renewed attention #MeToo brought to these accusations. After Junot Díaz was publicly accused on May 4, 2018, of sexually abusing women, causing immediate public protest, Mary Karr responded by reminding us on Twitter of the abuse she had reported nearly a decade earlier, prompting a series of blog articles and interviews that supported Karr by recounting the allegations made by Karr and Max. They also began to reveal the misogyny that had shaped and stifled public reception of those allegations.

Whitney Kimball pointed out that Max described Wallace’s violent treatment of Karr as beneficial to his creative output and part of what made him “fascinating”; that in praising the “quite remarkable” “craftsmanship” of one of Wallace’s letters, Max notes only in passing that the letter is Wallace’s apology for planning to buy a gun to kill Karr’s husband. Megan Garber noted the misogyny of an interviewer asking Max why “his feelings for [Karr] created such trouble for Wallace”—an example of what Kate Manne calls “himpathy,” or empathizing with a male perpetrator of sexual violence rather than the victim.

#MeToo also began to make the misogyny of Wallace’s work more visible to his readers. Devon Price describes how reading about Wallace’s abuses against women caused them to revisit Wallace’s work and see its gender violence for the first time. Tellingly, Price also realizes that one of the reasons they were depressed when they fell in love with Wallace’s work is that they were then in a physically, emotionally, and sexually abusive relationship. Price’s realization points to another common reason why readers are blind to or defensive about the misogyny in Wallace’s work and behavior, and to a key way in which the #MeToo movement can allow reading and literary studies to illuminate misogyny in synergistic ways: we are often blind to misogyny and sexual abuse, in fiction and in others’ behavior, because we are living in it unaware. And the awareness of the spectrum of sexual abuse brought by #MeToo testimonies reveals misogyny not just in the fiction that we read, but in our own lives—one revelation causing the other.

To date, no new criticism has emerged that directly considers the implications to his work of Wallace’s now widely reported misogyny and violence toward women. But the recent publication of Adrienne Miller’s memoir In the Land of Men (2020), which describes her years-long relationship with Wallace while she was literary editor at Esquire , makes a compelling, if unwitting, argument for the necessity of such biographically informed criticism. Miller documents the connection between Wallace’s life and work in excruciating detail, recounting extended scenes between them in which Wallace speaks and acts nearly identically to the misogynists of Brief Interviews , an identification he encourages by telling her that “some of the interviews were ‘actual conversations I had when I had to break up with people.’”

But though Miller lays out the “sexism” of Wallace’s fiction, especially Jest and Brief Interviews , more baldly than any of us Wallace scholars has so far, she remains, even from the vantage point of twenty years later and post-#MeToo, unable or unwilling to identify Wallace’s treatment of her as abusive or misogynistic. In fact, most shocking about the memoir is not its record of Wallace’s behavior but its methodical and steadfast refusal to acknowledge the gender violence of that behavior, and Miller’s disturbing pattern of normalizing, apologizing for, and denying it.

Ultimately, she attempts to redirect us from the question of whether her relationship with Wallace qualifies as abuse or sexual harassment by asking, “Who looks to the artist’s life for moral guidance anyway?” and “What are we to do with the art of profoundly compromised men?” But rather than neatly pivoting from Wallace’s culpability, these questions reveal important reasons why we must consider the lives of such men in conversation with their art. For these men are not merely passively “compromised” but aggressively compromis ing , in ways that our misogynistic culture obscures, and which savvy investigation of their art and lives can illuminate. And “moral” investigation is particularly indicated by the work of Wallace, who declared himself a maverick writer willing to return literature to earnestness and “love” (“Interview with David Foster Wallace” 1993), who wrote fiction that quizzes us on ethics and human value (“Octet” 1999), and who delivered a beloved commencement speech arguing the importance of recognizing one’s inherent narcissism in order to extend care to others.

What does it mean that this artist could not produce in his life the mutually respecting empathy he all but preached in his work (or, most clearly, in his statements about it)? What does it mean that a man and a body of work that claimed feminism in theory primarily produced a stream of abusive relationships between men and women in life and art? What can we learn about the blindness of both men and women to their participation in misogyny and rape culture, despite their professions of awareness of both? How might reading Wallace’s fiction in the contexts of biographical information about him and women’s narratives about their experiences of sexual violence enable us to better understand—and interrupt—the powerful hold misogyny and rape culture have on our society, our art, and our critical practices?

_____________________________________________________________________

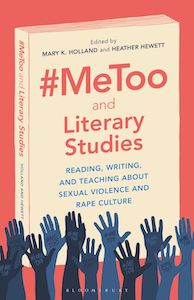

Excerpted from #MeToo and Literary Studies: Reading, Writing, and Teaching about Sexual Violence and Rape Culture , edited by Mary K. Holland & Heather Hewett. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Bloomsbury Academic. © 2021 by Mary K. Holland & Heather Hewett.

Mary K. Holland

Previous article, next article.

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

The best free cultural &

educational media on the web

- Online Courses

- Certificates

- Degrees & Mini-Degrees

- Audio Books

30 Free Essays & Stories by David Foster Wallace on the Web

in e-books , Literature | February 22nd, 2012 10 Comments

Image by Steve Rhodes, via Wikimedia Commons

We started the week expecting to publish one David Foster Wallace post . Then, because of the 50th birthday celebration, it turned into two . And now three. We spent some time tracking down free DFW stories and essays available on the web, and they’re all now listed in our collection, 800 Free eBooks for iPad, Kindle & Other Devices . But we didn’t want them to escape your attention. So here they are — 23 pieces published by David Foster Wallace between 1989 and 2011, mostly in major U.S. publications like The New Yorker , Harper’s , The Atlantic , and The Paris Review . Enjoy, and don’t miss our other collections of free writings by Philip K. Dick and Neil Gaiman .

- “9/11: The View From the Midwest” (Rolling Stone, October 25, 2001)

- “All That” (New Yorker, December 14, 2009)

- “An Interval” (New Yorker, January 30, 1995)

- “Asset” (New Yorker, January 30, 1995)

- “Backbone” An Excerpt from The Pale King (New Yorker, March 7, 2011)

- “Big Red Son” from Consider the Lobster & Other Essays

- “Brief Interviews with Hideous Men” (The Paris Review, Fall 1997)

- “Consider the Lobster” (Gourmet, August 2004)

- “David Lynch Keeps His Head” (Premiere, 1996)

- “Everything is Green” (Harpers, September 1989)

- “E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction” (The Review of Contemporary Fiction, June 22, 1993)

- “Federer as Religious Experience” (New York Times, August 20, 2006)

- “Good People” (New Yorker, February 5, 2007)

- “Host” (The Atlantic, April 2005)

- “Incarnations of Burned Children” (Esquire, April 21, 2009)

- “Laughing with Kafka” (Harper’s, January 1998)

- “Little Expressionless Animals” (The Paris Review, Spring 1988)

- “On Life and Work” (Kenyon College Commencement address, 2005)

- “Order and Flux in Northampton” (Conjunctions, 1991)

- “Rabbit Resurrected” (Harper’s, August 1992)

- “ Several Birds” (New Yorker, June 17, 1994)

- “Shipping Out: On the (nearly lethal) comforts of a luxury cruise” (Harper’s, January 1996)

- “Tennis, trigonometry, tornadoes A Midwestern boyhood” (Harper’s, December 1991)

- “Tense Present: Democracy, English, and the wars over usage” (Harper’s, April 2001)

- “The Awakening of My Interest in Annular Systems” (Harper’s, September 1993)

- “The Compliance Branch” (Harper’s, February 2008)

- “The Depressed Person” (Harper’s, January 1998)

- “The String Theory” (Esquire, July 1996)

- “The Weasel, Twelve Monkeys And The Shrub” (Rolling Stone, April 2000)

- “Ticket to the Fair” (Harper’s, July 1994)

- “Wiggle Room” (New Yorker, March 9, 2009)

Related Content:

Free Philip K. Dick: Download 13 Great Science Fiction Stories

Neil Gaiman’s Free Short Stories

Read 17 Short Stories From Nobel Prize-Winning Writer Alice Munro Free Online

10 Free Stories by George Saunders, Author of Tenth of December , “The Best Book You’ll Read This Year”

by OC | Permalink | Comments (10) |

Related posts:

Comments (10), 10 comments so far.

I got another free DFW essay for you: Big Red Son http://www.hachettebookgroup.com/books_9780316156110_ChapterExcerpt(1) .htm

Thanks very much. I added it to the list.

Appreciate it, Dan

Thanks very much for this information regarding essays and stories

Hi Dan. It’s a bit late for this, but I just remembered another link you might want to add. You can hear DFW giving the full unabridged Kenyon commencement speech (which you link to in your list) at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M5THXa_H_N8 (it’s in 2 parts). Or download the full audio from http://www.mediafire.com/?file41t3kfml6q6 Thanks for all your hard work!

This is excellent, thanks so much. Will these links be up permanently? I want to avoid the trouble of downloading the stuff I don’t have time to get to now.

Just thought I’d mention that ‘Little Expressionless Animals” cuts off about 2/3rds of the way through, requiring you to purchase the issue ($40) for the chance to read the rest.

Kind of a bummer.

Don’t forget “Tracy Austin Serves Up a Bubbly Life Story” (review of Tracy Austin’s Beyond Center Court: My Story): http://www.mendeley.com/research/tracy-austin-serves-up-bubbly-life-story-review-tracy-austins-beyond-center-court-story

Also, just to let you know, the link to “Big Red Son” is broken.

There’s also a ton of other here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Foster_Wallace_bibliography

You can add “Good Old Neon” to your list if you like:

http://kalamazoo.coop/sites/default/files/Good%20Old%20Neon.pdf

There’s a bunch of articles with broken links, notably those from Harper’s Magazine. Has anybody saved them and would be so kind to share them?

Add a comment

Leave a reply.

Name (required)

Email (required)

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Click here to cancel reply.

- 1,700 Free Online Courses

- 200 Online Certificate Programs

- 100+ Online Degree & Mini-Degree Programs

- 1,150 Free Movies

- 1,000 Free Audio Books

- 150+ Best Podcasts

- 800 Free eBooks

- 200 Free Textbooks

- 300 Free Language Lessons

- 150 Free Business Courses

- Free K-12 Education

- Get Our Daily Email

Free Courses

- Art & Art History

- Classics/Ancient World

- Computer Science

- Data Science

- Engineering

- Environment

- Political Science

- Writing & Journalism

- All 1700 Free Courses

Receive our Daily Email

Free updates, get our daily email.

Get the best cultural and educational resources on the web curated for you in a daily email. We never spam. Unsubscribe at any time.

FOLLOW ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Free Movies

- 1150 Free Movies Online

- Free Film Noir

- Silent Films

- Documentaries

- Martial Arts/Kung Fu

- Free Hitchcock Films

- Free Charlie Chaplin

- Free John Wayne Movies

- Free Tarkovsky Films

- Free Dziga Vertov

- Free Oscar Winners

- Free Language Lessons

- All Languages

Free eBooks

- 700 Free eBooks

- Free Philosophy eBooks

- The Harvard Classics

- Philip K. Dick Stories

- Neil Gaiman Stories

- David Foster Wallace Stories & Essays

- Hemingway Stories

- Great Gatsby & Other Fitzgerald Novels

- HP Lovecraft

- Edgar Allan Poe

- Free Alice Munro Stories

- Jennifer Egan Stories

- George Saunders Stories

- Hunter S. Thompson Essays

- Joan Didion Essays

- Gabriel Garcia Marquez Stories

- David Sedaris Stories

- Stephen King

- Golden Age Comics

- Free Books by UC Press

- Life Changing Books

Free Audio Books

- 700 Free Audio Books

- Free Audio Books: Fiction

- Free Audio Books: Poetry

- Free Audio Books: Non-Fiction

Free Textbooks

- Free Physics Textbooks

- Free Computer Science Textbooks

- Free Math Textbooks

K-12 Resources

- Free Video Lessons

- Web Resources by Subject

- Quality YouTube Channels

- Teacher Resources

- All Free Kids Resources

Free Art & Images

- All Art Images & Books

- The Rijksmuseum

- Smithsonian

- The Guggenheim

- The National Gallery

- The Whitney

- LA County Museum

- Stanford University

- British Library

- Google Art Project

- French Revolution

- Getty Images

- Guggenheim Art Books

- Met Art Books

- Getty Art Books

- New York Public Library Maps

- Museum of New Zealand

- Smarthistory

- Coloring Books

- All Bach Organ Works

- All of Bach

- 80,000 Classical Music Scores

- Free Classical Music

- Live Classical Music

- 9,000 Grateful Dead Concerts

- Alan Lomax Blues & Folk Archive

Writing Tips

- William Zinsser

- Kurt Vonnegut

- Toni Morrison

- Margaret Atwood

- David Ogilvy

- Billy Wilder

- All posts by date

Personal Finance

- Open Personal Finance

- Amazon Kindle

- Architecture

- Artificial Intelligence

- Comics/Cartoons

- Current Affairs

- English Language

- Entrepreneurship

- Food & Drink

- Graduation Speech

- How to Learn for Free

- Internet Archive

- Language Lessons

- Most Popular

- Neuroscience

- Photography

- Pretty Much Pop

- Productivity

- UC Berkeley

- Uncategorized

- Video - Arts & Culture

- Video - Politics/Society

- Video - Science

- Video Games

Great Lectures

- Michel Foucault

- Sun Ra at UC Berkeley

- Richard Feynman

- Joseph Campbell

- Jorge Luis Borges

- Leonard Bernstein

- Richard Dawkins

- Buckminster Fuller

- Walter Kaufmann on Existentialism

- Jacques Lacan

- Roland Barthes

- Nobel Lectures by Writers

- Bertrand Russell

- Oxford Philosophy Lectures

Sign up for Newsletter

Open Culture scours the web for the best educational media. We find the free courses and audio books you need, the language lessons & educational videos you want, and plenty of enlightenment in between.

Great Recordings

- T.S. Eliot Reads Waste Land

- Sylvia Plath - Ariel

- Joyce Reads Ulysses

- Joyce - Finnegans Wake

- Patti Smith Reads Virginia Woolf

- Albert Einstein

- Charles Bukowski

- Bill Murray

- Fitzgerald Reads Shakespeare

- William Faulkner

- Flannery O'Connor

- Tolkien - The Hobbit

- Allen Ginsberg - Howl

- Dylan Thomas

- Anne Sexton

- John Cheever

- David Foster Wallace

Book Lists By

- Neil deGrasse Tyson

- Ernest Hemingway

- F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Allen Ginsberg

- Patti Smith

- Henry Miller

- Christopher Hitchens

- Joseph Brodsky

- Donald Barthelme

- David Bowie

- Samuel Beckett

- Art Garfunkel

- Marilyn Monroe

- Picks by Female Creatives

- Zadie Smith & Gary Shteyngart

- Lynda Barry

Favorite Movies

- Kurosawa's 100

- David Lynch

- Werner Herzog

- Woody Allen

- Wes Anderson

- Luis Buñuel

- Roger Ebert

- Susan Sontag

- Scorsese Foreign Films

- Philosophy Films

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

©2006-2024 Open Culture, LLC. All rights reserved.

- Advertise with Us

- Copyright Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

Find anything you save across the site in your account

5 David Foster Wallace Essays You Should Read Before Seeing The End of the Tour

The End of the Tour could have been terrible; Jason Segel plays David Foster Wallace, and Jesse Eisenberg plays the douchey journalist charged with profiling him. But The End of the Tour is not terrible. It turns out Jason Segel is great at acting, and Jesse Eisenberg is great at being a douchebag.

So you’re really excited to see Segel put How I Met Your Mother behind him at last, but you’re harboring a dark secret: You’ve never read anything by David Foster Wallace. You lie and say you "found Infinite Jest and The Pale King positively resplendent." You say things like, “I admire Wallace’s fiction, but I much prefer his essays.” It’s alright. Everyone does it. Lying about having read David Foster Wallace is an American tradition. Like making up words to describe wine.

You'll like The End of the Tour whether you're a Wallace disciple or a flailing literary newborn, but a little primer never hurts. Here are five nuggets of Wallace brilliance that you can read before The End of the Tour comes out on July 31. Go forth, young man, and ooze pretension.

Ticket to the Fair

In 1993, a year before Infinite Jest was published, Wallace headed back to his native Illinois on assignment from Harper’s , to write about the Illinois State Fair. Ticket to the Fair is Wallace at his most readable. He’s just wandering around describing the height of Americana, like so:

The horses' faces are long and somehow suggestive of coffins. The racers are lanky, velvet over bone. The draft and show horses are mammoth and spotlessly groomed, and more or less odorless: the acrid smell in here is just the horses' pee: All their muscles are beautiful; the hides enhance them. They make farty noises when they sigh, heads hanging over the short doors. They're not for petting, though.

Read it here.

Consider the Lobster

The titular essay of Wallace’s collection Consider the Lobster began as a story for Gourmet . Following the tradition of sending Wallace to a mega-American event (see above) Gourmet sent Wallace to the Maine Lobster Festival. Every sentence of the essay is solid gold, and you will learn more about lobsters and life than you ever thought possible. As with all of Wallace’s writing, one must never skip the footnotes. Case in point, this tiny drama in note 11:

The short version regarding why we were back at the airport after already arriving the previous night involves lost luggage and a miscommunication about where and what the local National Car Rental franchise was—Dick came out personally to the airport and got us, out of no evident motive but kindness. (He also talked nonstop the entire way, with a very distinctive speaking style that can be described only as manically laconic; the truth is that I now know more about this man than I do about some members of my own family.)

9/11: The View From the Midwest

With the totally unnecessary caveat that this 2001 essay in Rolling Stone was “written very fast and in what probably qualifies as shock,” Wallace really, really effectively describes how most of the country experienced 9/11, or the Horror. A somber, great read, with little moments like this:

Mrs. T. has coffee on, but another sign of Crisis is that if you want some you have to get it yourself – usually it just sort of appears.

Roger Federer as Religious Experience

In 2008, when Roger Federer as Religious Experience ran in the Times , Federer mania was at its peak and Wallace was on the scene to explain it. Further proof that Wallace could write about literally anything in a nuanced way:

Nadal and Federer now warm each other up for precisely five minutes; the umpire keeps time. There’s a very definite order and etiquette to these pro warm-ups, which is something that television has decided you’re not interested in seeing.

Shipping Out: On the (Nearly Lethal) Comforts of a Luxury Cruise

Shipping Out , originally published in Harper’s in 1996, is the cornerstone of Wallace’s collection A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again . Many writers have tried and failed to describe the misery of luxury cruises as well as Wallace does. (Though an honorable mention goes to Tina Fey’s honeymoon in Bossypants .) Enjoy this tour of every neurotic man’s personal hell:

For the first two nights, who’s feeling seasick and who’s not and who’s not now but was a little while ago or isn’t feeling it yet but thinks it’s maybe coming on, etc. is a big topic of conversation at Table 64 in the Five-Star Caravelle Restaurant. Discussing nausea and vomiting while eating intricately prepared gourmet foods doesn’t seem to bother anybody.

Oh, to be blessed with a seat at Table 64. Read more here.

Related: John Jeremiah Sullivan Reviews The Pale King

Also Related:

This content can also be viewed on the site it originates from.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Really, all of the essays in Wallace’s canon. DFW is the Montaigne of Modern English. I also think “Authority and American Usage” is so good that it should be de rigueur curriculum for …

A. Wallace did some monstrous things in his life, particularly in his treatment of women, and in the era of MeToo that misogyny and abuse deserves to be dissected and ultimately grappled with, …

He’s up there with people like Talese and Caro based on a few slim volumes of essays. It’s incredible. A Supposedly Fun Thing to me stands out as both a great essay and so hilarious. Also the View from Mrs Thomas’ is perhaps the best …

David Foster Wallace’s work has long been celebrated for audaciously reorienting fiction toward empathy, sincerity, and human connection after decades of (supposedly) bleak postmodern assertions that all had …

When the David Foster Wallace died, he left behind a series of fragments: notes towards a dictionary all of his own. “Now go do the right thing” Fictional Futures and the Conspicuously Young. How does the literary …

If you want to make inroads into his fiction, Brief Interviews with Hideous Men is a very good starting place. I've found his non-fiction to be surprisingly relevant to his fiction, and having a …

So here they are — 23 pieces published by David Foster Wallace between 1989 and 2011, mostly in major U.S. publications like The New Yorker, Harper’s, The Atlantic, and The Paris Review.

Here are five nuggets of Wallace brilliance that you can read before The End of the Tour comes out on July 31. Go forth, young man, and ooze pretension. Ticket to the Fair