Relevance of Reliability and Validity in Qualitative Research

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Traditional, quantitative concepts of validity and reliability are frequently used to critique qualitative research, often leading to criticisms of lacking scientific rigor, insufficient methodological justification, lack of transparency in analysis, and potential for researcher bias.

Alternative terminology is proposed to better capture the principles of rigor and credibility within the qualitative paradigm :

Validity in Qualitative Research

Validity focuses on the truthfulness and accuracy of findings.

Quantitative research, with its focus on objectivity and generalizability, prioritizes internal validity to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables.

This involves carefully controlling extraneous factors to ensure the observed effects can be confidently attributed to the independent variable.

Qualitative research embraces a different epistemological framework, emphasizing subjectivity, contextual understanding, and the exploration of lived experiences.

In this paradigm, validity focuses on faithfully representing the perspectives, meanings, and interpretations of the participants.

The underlying goal remains to produce research that is rigorous, credible, and insightful, contributing meaningfully to our understanding of complex social phenomena.

This involves ensuring the research process and findings are trustworthy, authentic, and rigorous.

1. Trustworthiness

Validity in qualitative research, often referred to as trustworthiness , assesses the accuracy of findings as representations of the data, participants’ lives, cultures, and contexts.

Trustworthiness is an overarching concept that encompasses both credibility and transferability , reflecting the overall quality and integrity of the research process and findings. It signifies that the research is conducted ethically, rigorously, and transparently.

A central concept in achieving trustworthiness is methodological integrity , which emphasizes the importance of using methods and procedures that are consistent with the research question, goals, and inquiry approach.

Methodological integrity focuses on two key components: fidelity to the subject matter and utility of research contributions .

Fidelity to the Subject Matter

Fidelity to the subject matter emphasizes collecting data that capture the diversity and complexity of the phenomenon under study.

Qualitative research underscores the commitment to representing participants’ authentic perspectives and experiences faithfully and respectfully.

This goes beyond simply recording their words; it involves capturing the depth, complexity, and meaning embedded within their narratives.

Fidelity to the subject matter must demonstratee that the data is adequate to answer the research question and that the researcher’s perspectives were managed during both data collection and analysis to minimize bias.

Researchers should show that the findings are grounded in the evidence by using rich quotes and detailed descriptions of their engagement with the data. This is also referred to as thick, lush description.

Thick description involves going beyond surface-level observations to provide rich, detailed accounts of the data. This includes not just what participants say but also the context of their utterances, their emotional tone, and the nonverbal cues that contribute to meaning.

Thick description enhances authenticity by painting a vivid picture of the participants’ lived experiences, allowing readers to grasp the nuances and complexities of their perspectives.

For instance, if studying a phenomenon like “pain,” researchers should acknowledge whether they perceive it as a real, tangible experience or a socially constructed one.

This understanding shapes data collection and analysis, ensuring the findings remain true to the participants’ realities.

Utility of Research Contributions

Utility refers to the usefulness and value of the research findings.

Studies with high utility introduce new insights, expand upon existing knowledge, or offer practical applications for researchers and practitioners.

The utility of a study’s findings is evaluated in relation to its aims and tradition of inquiry. For example, studies with a critical approach should contribute to an awareness of power dynamics and oppression.

A study might have high fidelity by providing compelling descriptions of student study challenges, but if it only offers obvious or commonly known study strategies, it would have low utility.

Ideally, a study would possess both high fidelity and utility, providing a clear understanding of the phenomenon while also offering valuable contributions to the field.

Strategies to enhance trustworthiness and methodological integrity:

- Using rigorous research methods: Selecting and justifying the chosen qualitative method based on its established rigor enhances credibility and demonstrates a commitment to methodological soundness.

- Reflexivity: Critically examining personal biases, values, and experiences helps researchers identify potential influences on their interpretations and ensure that findings are not solely a product of their own perspectives.

- Promoting authentic voice: Researchers should strive to create conditions that allow participants to express themselves openly and honestly.

- Truth Value: Acknowledging the existence of multiple perspectives and ensuring that the findings accurately represent the participants’ views and experiences.

- Member checking: Involving participants in the research process by sharing findings with them to confirm the accuracy of interpretations.

- Triangulation: Utilizing multiple data sources, methods, or researchers to corroborate findings and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon.

- Prolonged engagement: Spending sufficient time in the field to develop a deep understanding of the context and build rapport with participants, which can lead to more insightful and trustworthy data.

- Using thick, rich descriptions: Providing detailed narratives, representative quotes, and thorough descriptions of the context helps readers understand the phenomenon and assess the credibility and transferability of the findings.

- Ensuring continuous data saturation : Immersing oneself in the data, constantly refining understanding, and remaining open to gathering more data if needed ensure that the data adequately captures the complexity and diversity of the phenomenon under study.

2. Transferability

Transferability in qualitative research is similar to external validity in quantitative research. It refers to the extent to which the findings can be applied or transferred to other contexts, settings, or groups.

While generalizability in the statistical sense is not a primary goal of qualitative research, providing sufficient details about the study context, sample, and methods can enhance the transferability of the findings.

Qualitative research prioritizes transferability over generalizability. Transferability acknowledges the context-specific nature of findings and encourages readers to consider the potential applicability of the research to other settings.

Researchers can promote transferability by providing thick descriptions of the context, the participants, and the research process.

Transferability is an external consideration, inviting readers to evaluate the potential applicability of the findings to other settings.

Promoting Transferability :

- Providing thick description: Offering detailed contextual information about the setting, participants, and findings, allowing readers to assess the potential relevance to other settings.

- Purposive sampling: Selecting participants who represent a range of perspectives and experiences relevant to the research question. This can enhance the applicability of the findings to a broader population.

- Discussing limitations: Openly acknowledging the specificities of the research context and the potential limitations of applying the findings to other settings.

Barriers to Validity in Qualitative Research

Researchers should be aware of potential threats to validity and take steps to mitigate them. Some common pitfalls include:

Researcher Bias and Perspective

Researchers’ own beliefs, values, and assumptions can influence data collection, analysis, and interpretation, potentially distorting the findings.

Acknowledging and managing these perspectives is crucial for ensuring fidelity to the subject matter.

This aligns with the concept of reflexivity in qualitative research, which encourages researchers to critically examine their own positionality and its potential impact on the research process.

Inadequate Sampling and Representation

If the sample of participants is not representative of the population of interest or if the data collected are incomplete or insufficiently detailed, the findings might lack conceptual heterogeneity and fail to capture the full range of perspectives and experiences relevant to the research question.

This emphasizes the importance of purposive sampling in qualitative research, aiming to select participants who can provide rich and diverse insights into the phenomenon under study.

Superficial Data and Lack of Thick Description

When data are presented in a cursory or overly simplistic manner, without sufficient detail and context, the validity of the findings can be questioned.

This reductionism can stem from a lack of thorough data analysis or a tendency to prioritize brevity over depth in reporting the results

Thick description , a cornerstone of qualitative research, involves providing rich, detailed accounts of the data, capturing the nuances of the participants’ experiences and the context in which they occur.

Selective Anecdotalism and Cherry-Picking

Choosing to focus on specific anecdotes or data points that support the researcher’s preconceived notions while ignoring contradictory evidence can severely undermine validity.

This selective reporting distorts the overall picture and presents a biased view of the findings.

Qualitative researchers are expected to analyze and present data comprehensively, acknowledging all relevant themes and perspectives, even those that challenge their initial assumptions.

Perceived Coercion and Power Dynamics

In qualitative research, especially when dealing with sensitive topics or vulnerable populations, power imbalances between the researcher and participants can influence the data obtained.

If participants feel pressured or coerced to provide certain answers, their responses might lack authenticity and fail to reflect their genuine perspectives.

This underscores the importance of establishing trust and rapport with participants, ensuring they feel safe and comfortable to share their experiences openly and honestly.

Attrition in Longitudinal Studies

In qualitative studies that involve multiple data collection points over time, participant attrition can threaten validity.

If participants drop out of the study for reasons related to the research topic, the remaining sample might become biased, and the findings might not accurately reflect the experiences of the original group.

Addressing attrition requires careful planning and implementation of strategies to maintain participant engagement and minimize drop-out rates.

Reliability in Qualitative Research

Traditional quantitative definition, focused on the replicability of results, is not directly applicable to qualitative inquiry.

This is because qualitative research often explores complex, context-specific phenomena that are influenced by multiple subjective interpretations.

In qualitative research, reliability refers to the consistency and stability of the research proces s and findings.

Reliability in qualitative research concerns consistency and dependability in data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

Dependability

Instead of striving for replicability, qualitative research prioritizes dependability , which focuses on the consistency and trustworthiness of the research process itself.

This involves demonstrating that the methods used were appropriate, that the data were collected and analyzed systematically, and that the interpretations are well-supported by the evidence.

Researchers can establish dependability using methods such as audit trails so readers can see the research process is logical and traceable (Koch, 1994).

Strategies for promoting reliability in qualitative research:

- Standardized procedures: Establishing clear and consistent protocols for data collection, analysis, and interpretation can help ensure that the research process is systematic and replicable.

- Rigorous training for researchers in qualitative methodologies, data analysis techniques, and reflexive practices to manage their own perspectives and biases.

- Audit trails: An audit trail provides evidence of the decisions made by the researcher regarding theory, research design, and data collection, as well as the steps they have chosen to manage, analyze, and report data. This includes maintaining detailed field notes, documenting coding decisions, and preserving raw data for future reference.

- Transparency in reporting: Clearly articulating the research design, data collection methods, analytical procedures, and the researcher’s own reflexivity allows readers to assess the trustworthiness of the findings and understand the logic behind the interpretations.

- Interrater reliability (optional): While not universally employed in qualitative research, involving multiple coders to analyze the data can provide insights into the consistency of interpretations. However, it’s important to note that complete agreement might not be the goal, as differing perspectives can enrich the analysis. Discrepancies can be discussed and resolved, leading to a more comprehensive understanding of the data.

Barriers to Reliability in Qualitative Research

Subjectivity in data collection and analysis.

One of the main barriers to reliability stems from the subjective nature of qualitative data collection and analysis.

Unlike quantitative research with its standardized procedures, qualitative research often involves a deep engagement with participants and data, relying on the researcher’s interpretation and judgment.

This introduces potential for inconsistency in data coding and interpretation, especially when multiple researchers are involved.

Researchers’ personal backgrounds, experiences, and theoretical orientations can influence their interpretation of the data.

What one researcher considers significant or meaningful may differ from another researcher’s perspective.

This subjectivity can lead to variations in how data is collected, coded, and analyzed, especially when multiple researchers are involved in a study.

Lack of Detailed Documentation

Qualitative studies often involve complex and iterative processes of data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Without a clear and comprehensive record of these processes, it becomes challenging for others to assess the dependability and consistency of the findings.

Insufficient documentation of data collection methods, coding schemes, analytical decisions, and researcher reflexivity can hinder the ability to establish reliability.

A detailed audit trail, which provides a transparent account of the research process, is crucial for demonstrating the trustworthiness and credibility of qualitative findings.

Lack of detailed documentation of the research process, including data collection methods, coding schemes, and analytical decisions, can hinder reliability.

Without such documentation, it becomes difficult for other researchers to replicate the study or assess the reliability of the conclusions drawn.

Reductionism in Data Representation

Reductionism, or oversimplifying complex data by relying on short quotes and superficial descriptions, can also compromise reliability.

Such reductive practices can distort the richness and nuance of the data, leading to potentially misleading interpretations.

Qualitative research often yields rich, nuanced, and context-specific data that cannot be easily reduced to simple categories or short quotes.

However, in an effort to present findings concisely, researchers may resort to reductive practices that distort the true nature of the data.

Relying on short quotes or superficial descriptions without providing sufficient context can lead to misinterpretations and oversimplification.

Such reductive practices fail to capture the complexity and depth of the participants’ experiences and perspectives.

As a result, the reliability of the findings may be questioned, as they may not accurately represent the full range of data collected.

Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review

- Regular Article

- Open access

- Published: 18 September 2021

- Volume 31 , pages 679–689, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Drishti Yadav ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2974-0323 1

113k Accesses

55 Citations

68 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This review aims to synthesize a published set of evaluative criteria for good qualitative research. The aim is to shed light on existing standards for assessing the rigor of qualitative research encompassing a range of epistemological and ontological standpoints. Using a systematic search strategy, published journal articles that deliberate criteria for rigorous research were identified. Then, references of relevant articles were surveyed to find noteworthy, distinct, and well-defined pointers to good qualitative research. This review presents an investigative assessment of the pivotal features in qualitative research that can permit the readers to pass judgment on its quality and to condemn it as good research when objectively and adequately utilized. Overall, this review underlines the crux of qualitative research and accentuates the necessity to evaluate such research by the very tenets of its being. It also offers some prospects and recommendations to improve the quality of qualitative research. Based on the findings of this review, it is concluded that quality criteria are the aftereffect of socio-institutional procedures and existing paradigmatic conducts. Owing to the paradigmatic diversity of qualitative research, a single and specific set of quality criteria is neither feasible nor anticipated. Since qualitative research is not a cohesive discipline, researchers need to educate and familiarize themselves with applicable norms and decisive factors to evaluate qualitative research from within its theoretical and methodological framework of origin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Good Qualitative Research: Opening up the Debate

Beyond qualitative/quantitative structuralism: the positivist qualitative research and the paradigmatic disclaimer.

What is Qualitative in Research

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“… It is important to regularly dialogue about what makes for good qualitative research” (Tracy, 2010 , p. 837)

To decide what represents good qualitative research is highly debatable. There are numerous methods that are contained within qualitative research and that are established on diverse philosophical perspectives. Bryman et al., ( 2008 , p. 262) suggest that “It is widely assumed that whereas quality criteria for quantitative research are well‐known and widely agreed, this is not the case for qualitative research.” Hence, the question “how to evaluate the quality of qualitative research” has been continuously debated. There are many areas of science and technology wherein these debates on the assessment of qualitative research have taken place. Examples include various areas of psychology: general psychology (Madill et al., 2000 ); counseling psychology (Morrow, 2005 ); and clinical psychology (Barker & Pistrang, 2005 ), and other disciplines of social sciences: social policy (Bryman et al., 2008 ); health research (Sparkes, 2001 ); business and management research (Johnson et al., 2006 ); information systems (Klein & Myers, 1999 ); and environmental studies (Reid & Gough, 2000 ). In the literature, these debates are enthused by the impression that the blanket application of criteria for good qualitative research developed around the positivist paradigm is improper. Such debates are based on the wide range of philosophical backgrounds within which qualitative research is conducted (e.g., Sandberg, 2000 ; Schwandt, 1996 ). The existence of methodological diversity led to the formulation of different sets of criteria applicable to qualitative research.

Among qualitative researchers, the dilemma of governing the measures to assess the quality of research is not a new phenomenon, especially when the virtuous triad of objectivity, reliability, and validity (Spencer et al., 2004 ) are not adequate. Occasionally, the criteria of quantitative research are used to evaluate qualitative research (Cohen & Crabtree, 2008 ; Lather, 2004 ). Indeed, Howe ( 2004 ) claims that the prevailing paradigm in educational research is scientifically based experimental research. Hypotheses and conjectures about the preeminence of quantitative research can weaken the worth and usefulness of qualitative research by neglecting the prominence of harmonizing match for purpose on research paradigm, the epistemological stance of the researcher, and the choice of methodology. Researchers have been reprimanded concerning this in “paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences” (Lincoln & Guba, 2000 ).

In general, qualitative research tends to come from a very different paradigmatic stance and intrinsically demands distinctive and out-of-the-ordinary criteria for evaluating good research and varieties of research contributions that can be made. This review attempts to present a series of evaluative criteria for qualitative researchers, arguing that their choice of criteria needs to be compatible with the unique nature of the research in question (its methodology, aims, and assumptions). This review aims to assist researchers in identifying some of the indispensable features or markers of high-quality qualitative research. In a nutshell, the purpose of this systematic literature review is to analyze the existing knowledge on high-quality qualitative research and to verify the existence of research studies dealing with the critical assessment of qualitative research based on the concept of diverse paradigmatic stances. Contrary to the existing reviews, this review also suggests some critical directions to follow to improve the quality of qualitative research in different epistemological and ontological perspectives. This review is also intended to provide guidelines for the acceleration of future developments and dialogues among qualitative researchers in the context of assessing the qualitative research.

The rest of this review article is structured in the following fashion: Sect. Methods describes the method followed for performing this review. Section Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies provides a comprehensive description of the criteria for evaluating qualitative studies. This section is followed by a summary of the strategies to improve the quality of qualitative research in Sect. Improving Quality: Strategies . Section How to Assess the Quality of the Research Findings? provides details on how to assess the quality of the research findings. After that, some of the quality checklists (as tools to evaluate quality) are discussed in Sect. Quality Checklists: Tools for Assessing the Quality . At last, the review ends with the concluding remarks presented in Sect. Conclusions, Future Directions and Outlook . Some prospects in qualitative research for enhancing its quality and usefulness in the social and techno-scientific research community are also presented in Sect. Conclusions, Future Directions and Outlook .

For this review, a comprehensive literature search was performed from many databases using generic search terms such as Qualitative Research , Criteria , etc . The following databases were chosen for the literature search based on the high number of results: IEEE Explore, ScienceDirect, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science. The following keywords (and their combinations using Boolean connectives OR/AND) were adopted for the literature search: qualitative research, criteria, quality, assessment, and validity. The synonyms for these keywords were collected and arranged in a logical structure (see Table 1 ). All publications in journals and conference proceedings later than 1950 till 2021 were considered for the search. Other articles extracted from the references of the papers identified in the electronic search were also included. A large number of publications on qualitative research were retrieved during the initial screening. Hence, to include the searches with the main focus on criteria for good qualitative research, an inclusion criterion was utilized in the search string.

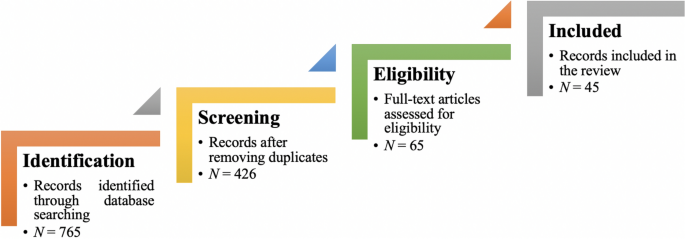

From the selected databases, the search retrieved a total of 765 publications. Then, the duplicate records were removed. After that, based on the title and abstract, the remaining 426 publications were screened for their relevance by using the following inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Table 2 ). Publications focusing on evaluation criteria for good qualitative research were included, whereas those works which delivered theoretical concepts on qualitative research were excluded. Based on the screening and eligibility, 45 research articles were identified that offered explicit criteria for evaluating the quality of qualitative research and were found to be relevant to this review.

Figure 1 illustrates the complete review process in the form of PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, i.e., “preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses” is employed in systematic reviews to refine the quality of reporting.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the search and inclusion process. N represents the number of records

Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies

Fundamental criteria: general research quality.

Various researchers have put forward criteria for evaluating qualitative research, which have been summarized in Table 3 . Also, the criteria outlined in Table 4 effectively deliver the various approaches to evaluate and assess the quality of qualitative work. The entries in Table 4 are based on Tracy’s “Eight big‐tent criteria for excellent qualitative research” (Tracy, 2010 ). Tracy argues that high-quality qualitative work should formulate criteria focusing on the worthiness, relevance, timeliness, significance, morality, and practicality of the research topic, and the ethical stance of the research itself. Researchers have also suggested a series of questions as guiding principles to assess the quality of a qualitative study (Mays & Pope, 2020 ). Nassaji ( 2020 ) argues that good qualitative research should be robust, well informed, and thoroughly documented.

Qualitative Research: Interpretive Paradigms

All qualitative researchers follow highly abstract principles which bring together beliefs about ontology, epistemology, and methodology. These beliefs govern how the researcher perceives and acts. The net, which encompasses the researcher’s epistemological, ontological, and methodological premises, is referred to as a paradigm, or an interpretive structure, a “Basic set of beliefs that guides action” (Guba, 1990 ). Four major interpretive paradigms structure the qualitative research: positivist and postpositivist, constructivist interpretive, critical (Marxist, emancipatory), and feminist poststructural. The complexity of these four abstract paradigms increases at the level of concrete, specific interpretive communities. Table 5 presents these paradigms and their assumptions, including their criteria for evaluating research, and the typical form that an interpretive or theoretical statement assumes in each paradigm. Moreover, for evaluating qualitative research, quantitative conceptualizations of reliability and validity are proven to be incompatible (Horsburgh, 2003 ). In addition, a series of questions have been put forward in the literature to assist a reviewer (who is proficient in qualitative methods) for meticulous assessment and endorsement of qualitative research (Morse, 2003 ). Hammersley ( 2007 ) also suggests that guiding principles for qualitative research are advantageous, but methodological pluralism should not be simply acknowledged for all qualitative approaches. Seale ( 1999 ) also points out the significance of methodological cognizance in research studies.

Table 5 reflects that criteria for assessing the quality of qualitative research are the aftermath of socio-institutional practices and existing paradigmatic standpoints. Owing to the paradigmatic diversity of qualitative research, a single set of quality criteria is neither possible nor desirable. Hence, the researchers must be reflexive about the criteria they use in the various roles they play within their research community.

Improving Quality: Strategies

Another critical question is “How can the qualitative researchers ensure that the abovementioned quality criteria can be met?” Lincoln and Guba ( 1986 ) delineated several strategies to intensify each criteria of trustworthiness. Other researchers (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016 ; Shenton, 2004 ) also presented such strategies. A brief description of these strategies is shown in Table 6 .

It is worth mentioning that generalizability is also an integral part of qualitative research (Hays & McKibben, 2021 ). In general, the guiding principle pertaining to generalizability speaks about inducing and comprehending knowledge to synthesize interpretive components of an underlying context. Table 7 summarizes the main metasynthesis steps required to ascertain generalizability in qualitative research.

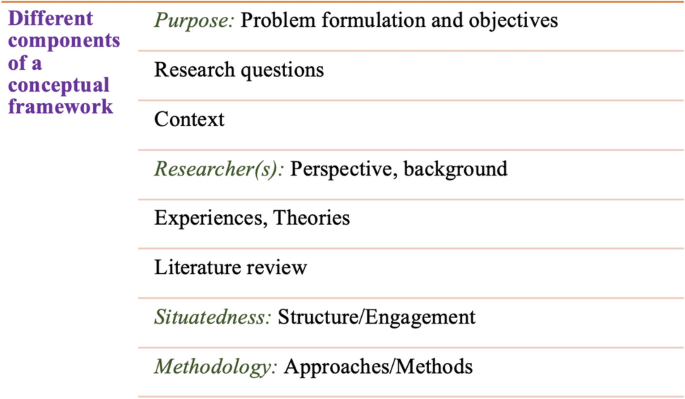

Figure 2 reflects the crucial components of a conceptual framework and their contribution to decisions regarding research design, implementation, and applications of results to future thinking, study, and practice (Johnson et al., 2020 ). The synergy and interrelationship of these components signifies their role to different stances of a qualitative research study.

Essential elements of a conceptual framework

In a nutshell, to assess the rationale of a study, its conceptual framework and research question(s), quality criteria must take account of the following: lucid context for the problem statement in the introduction; well-articulated research problems and questions; precise conceptual framework; distinct research purpose; and clear presentation and investigation of the paradigms. These criteria would expedite the quality of qualitative research.

How to Assess the Quality of the Research Findings?

The inclusion of quotes or similar research data enhances the confirmability in the write-up of the findings. The use of expressions (for instance, “80% of all respondents agreed that” or “only one of the interviewees mentioned that”) may also quantify qualitative findings (Stenfors et al., 2020 ). On the other hand, the persuasive reason for “why this may not help in intensifying the research” has also been provided (Monrouxe & Rees, 2020 ). Further, the Discussion and Conclusion sections of an article also prove robust markers of high-quality qualitative research, as elucidated in Table 8 .

Quality Checklists: Tools for Assessing the Quality

Numerous checklists are available to speed up the assessment of the quality of qualitative research. However, if used uncritically and recklessly concerning the research context, these checklists may be counterproductive. I recommend that such lists and guiding principles may assist in pinpointing the markers of high-quality qualitative research. However, considering enormous variations in the authors’ theoretical and philosophical contexts, I would emphasize that high dependability on such checklists may say little about whether the findings can be applied in your setting. A combination of such checklists might be appropriate for novice researchers. Some of these checklists are listed below:

The most commonly used framework is Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) (Tong et al., 2007 ). This framework is recommended by some journals to be followed by the authors during article submission.

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) is another checklist that has been created particularly for medical education (O’Brien et al., 2014 ).

Also, Tracy ( 2010 ) and Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP, 2021 ) offer criteria for qualitative research relevant across methods and approaches.

Further, researchers have also outlined different criteria as hallmarks of high-quality qualitative research. For instance, the “Road Trip Checklist” (Epp & Otnes, 2021 ) provides a quick reference to specific questions to address different elements of high-quality qualitative research.

Conclusions, Future Directions, and Outlook

This work presents a broad review of the criteria for good qualitative research. In addition, this article presents an exploratory analysis of the essential elements in qualitative research that can enable the readers of qualitative work to judge it as good research when objectively and adequately utilized. In this review, some of the essential markers that indicate high-quality qualitative research have been highlighted. I scope them narrowly to achieve rigor in qualitative research and note that they do not completely cover the broader considerations necessary for high-quality research. This review points out that a universal and versatile one-size-fits-all guideline for evaluating the quality of qualitative research does not exist. In other words, this review also emphasizes the non-existence of a set of common guidelines among qualitative researchers. In unison, this review reinforces that each qualitative approach should be treated uniquely on account of its own distinctive features for different epistemological and disciplinary positions. Owing to the sensitivity of the worth of qualitative research towards the specific context and the type of paradigmatic stance, researchers should themselves analyze what approaches can be and must be tailored to ensemble the distinct characteristics of the phenomenon under investigation. Although this article does not assert to put forward a magic bullet and to provide a one-stop solution for dealing with dilemmas about how, why, or whether to evaluate the “goodness” of qualitative research, it offers a platform to assist the researchers in improving their qualitative studies. This work provides an assembly of concerns to reflect on, a series of questions to ask, and multiple sets of criteria to look at, when attempting to determine the quality of qualitative research. Overall, this review underlines the crux of qualitative research and accentuates the need to evaluate such research by the very tenets of its being. Bringing together the vital arguments and delineating the requirements that good qualitative research should satisfy, this review strives to equip the researchers as well as reviewers to make well-versed judgment about the worth and significance of the qualitative research under scrutiny. In a nutshell, a comprehensive portrayal of the research process (from the context of research to the research objectives, research questions and design, speculative foundations, and from approaches of collecting data to analyzing the results, to deriving inferences) frequently proliferates the quality of a qualitative research.

Prospects : A Road Ahead for Qualitative Research

Irrefutably, qualitative research is a vivacious and evolving discipline wherein different epistemological and disciplinary positions have their own characteristics and importance. In addition, not surprisingly, owing to the sprouting and varied features of qualitative research, no consensus has been pulled off till date. Researchers have reflected various concerns and proposed several recommendations for editors and reviewers on conducting reviews of critical qualitative research (Levitt et al., 2021 ; McGinley et al., 2021 ). Following are some prospects and a few recommendations put forward towards the maturation of qualitative research and its quality evaluation:

In general, most of the manuscript and grant reviewers are not qualitative experts. Hence, it is more likely that they would prefer to adopt a broad set of criteria. However, researchers and reviewers need to keep in mind that it is inappropriate to utilize the same approaches and conducts among all qualitative research. Therefore, future work needs to focus on educating researchers and reviewers about the criteria to evaluate qualitative research from within the suitable theoretical and methodological context.

There is an urgent need to refurbish and augment critical assessment of some well-known and widely accepted tools (including checklists such as COREQ, SRQR) to interrogate their applicability on different aspects (along with their epistemological ramifications).

Efforts should be made towards creating more space for creativity, experimentation, and a dialogue between the diverse traditions of qualitative research. This would potentially help to avoid the enforcement of one's own set of quality criteria on the work carried out by others.

Moreover, journal reviewers need to be aware of various methodological practices and philosophical debates.

It is pivotal to highlight the expressions and considerations of qualitative researchers and bring them into a more open and transparent dialogue about assessing qualitative research in techno-scientific, academic, sociocultural, and political rooms.

Frequent debates on the use of evaluative criteria are required to solve some potentially resolved issues (including the applicability of a single set of criteria in multi-disciplinary aspects). Such debates would not only benefit the group of qualitative researchers themselves, but primarily assist in augmenting the well-being and vivacity of the entire discipline.

To conclude, I speculate that the criteria, and my perspective, may transfer to other methods, approaches, and contexts. I hope that they spark dialog and debate – about criteria for excellent qualitative research and the underpinnings of the discipline more broadly – and, therefore, help improve the quality of a qualitative study. Further, I anticipate that this review will assist the researchers to contemplate on the quality of their own research, to substantiate research design and help the reviewers to review qualitative research for journals. On a final note, I pinpoint the need to formulate a framework (encompassing the prerequisites of a qualitative study) by the cohesive efforts of qualitative researchers of different disciplines with different theoretic-paradigmatic origins. I believe that tailoring such a framework (of guiding principles) paves the way for qualitative researchers to consolidate the status of qualitative research in the wide-ranging open science debate. Dialogue on this issue across different approaches is crucial for the impending prospects of socio-techno-educational research.

Amin, M. E. K., Nørgaard, L. S., Cavaco, A. M., Witry, M. J., Hillman, L., Cernasev, A., & Desselle, S. P. (2020). Establishing trustworthiness and authenticity in qualitative pharmacy research. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 16 (10), 1472–1482.

Article Google Scholar

Barker, C., & Pistrang, N. (2005). Quality criteria under methodological pluralism: Implications for conducting and evaluating research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 35 (3–4), 201–212.

Bryman, A., Becker, S., & Sempik, J. (2008). Quality criteria for quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods research: A view from social policy. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11 (4), 261–276.

Caelli, K., Ray, L., & Mill, J. (2003). ‘Clear as mud’: Toward greater clarity in generic qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2 (2), 1–13.

CASP (2021). CASP checklists. Retrieved May 2021 from https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

Cohen, D. J., & Crabtree, B. F. (2008). Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: Controversies and recommendations. The Annals of Family Medicine, 6 (4), 331–339.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 1–32). Sage Publications Ltd.

Google Scholar

Elliott, R., Fischer, C. T., & Rennie, D. L. (1999). Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38 (3), 215–229.

Epp, A. M., & Otnes, C. C. (2021). High-quality qualitative research: Getting into gear. Journal of Service Research . https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670520961445

Guba, E. G. (1990). The paradigm dialog. In Alternative paradigms conference, mar, 1989, Indiana u, school of education, San Francisco, ca, us . Sage Publications, Inc.

Hammersley, M. (2007). The issue of quality in qualitative research. International Journal of Research and Method in Education, 30 (3), 287–305.

Haven, T. L., Errington, T. M., Gleditsch, K. S., van Grootel, L., Jacobs, A. M., Kern, F. G., & Mokkink, L. B. (2020). Preregistering qualitative research: A Delphi study. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19 , 1609406920976417.

Hays, D. G., & McKibben, W. B. (2021). Promoting rigorous research: Generalizability and qualitative research. Journal of Counseling and Development, 99 (2), 178–188.

Horsburgh, D. (2003). Evaluation of qualitative research. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 12 (2), 307–312.

Howe, K. R. (2004). A critique of experimentalism. Qualitative Inquiry, 10 (1), 42–46.

Johnson, J. L., Adkins, D., & Chauvin, S. (2020). A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 84 (1), 7120.

Johnson, P., Buehring, A., Cassell, C., & Symon, G. (2006). Evaluating qualitative management research: Towards a contingent criteriology. International Journal of Management Reviews, 8 (3), 131–156.

Klein, H. K., & Myers, M. D. (1999). A set of principles for conducting and evaluating interpretive field studies in information systems. MIS Quarterly, 23 (1), 67–93.

Lather, P. (2004). This is your father’s paradigm: Government intrusion and the case of qualitative research in education. Qualitative Inquiry, 10 (1), 15–34.

Levitt, H. M., Morrill, Z., Collins, K. M., & Rizo, J. L. (2021). The methodological integrity of critical qualitative research: Principles to support design and research review. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 68 (3), 357.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1986). But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Program Evaluation, 1986 (30), 73–84.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (2000). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions and emerging confluences. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 163–188). Sage Publications.

Madill, A., Jordan, A., & Shirley, C. (2000). Objectivity and reliability in qualitative analysis: Realist, contextualist and radical constructionist epistemologies. British Journal of Psychology, 91 (1), 1–20.

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2020). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Research in Health Care . https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119410867.ch15

McGinley, S., Wei, W., Zhang, L., & Zheng, Y. (2021). The state of qualitative research in hospitality: A 5-year review 2014 to 2019. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 62 (1), 8–20.

Merriam, S., & Tisdell, E. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, US.

Meyer, M., & Dykes, J. (2019). Criteria for rigor in visualization design study. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 26 (1), 87–97.

Monrouxe, L. V., & Rees, C. E. (2020). When I say… quantification in qualitative research. Medical Education, 54 (3), 186–187.

Morrow, S. L. (2005). Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52 (2), 250.

Morse, J. M. (2003). A review committee’s guide for evaluating qualitative proposals. Qualitative Health Research, 13 (6), 833–851.

Nassaji, H. (2020). Good qualitative research. Language Teaching Research, 24 (4), 427–431.

O’Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89 (9), 1245–1251.

O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19 , 1609406919899220.

Reid, A., & Gough, S. (2000). Guidelines for reporting and evaluating qualitative research: What are the alternatives? Environmental Education Research, 6 (1), 59–91.

Rocco, T. S. (2010). Criteria for evaluating qualitative studies. Human Resource Development International . https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2010.501959

Sandberg, J. (2000). Understanding human competence at work: An interpretative approach. Academy of Management Journal, 43 (1), 9–25.

Schwandt, T. A. (1996). Farewell to criteriology. Qualitative Inquiry, 2 (1), 58–72.

Seale, C. (1999). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 5 (4), 465–478.

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22 (2), 63–75.

Sparkes, A. C. (2001). Myth 94: Qualitative health researchers will agree about validity. Qualitative Health Research, 11 (4), 538–552.

Spencer, L., Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., & Dillon, L. (2004). Quality in qualitative evaluation: A framework for assessing research evidence.

Stenfors, T., Kajamaa, A., & Bennett, D. (2020). How to assess the quality of qualitative research. The Clinical Teacher, 17 (6), 596–599.

Taylor, E. W., Beck, J., & Ainsworth, E. (2001). Publishing qualitative adult education research: A peer review perspective. Studies in the Education of Adults, 33 (2), 163–179.

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19 (6), 349–357.

Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16 (10), 837–851.

Download references

Open access funding provided by TU Wien (TUW).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Informatics, Technische Universität Wien, 1040, Vienna, Austria

Drishti Yadav

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Drishti Yadav .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Yadav, D. Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 31 , 679–689 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0

Download citation

Accepted : 28 August 2021

Published : 18 September 2021

Issue Date : December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Qualitative research

- Evaluative criteria

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research