Download 55 million PDFs for free

Explore our top research interests.

Engineering

Anthropology

- Earth Sciences

- Computer Science

- Mathematics

- Health Sciences

Join 258 million academics and researchers

Track your impact.

Share your work with other academics, grow your audience and track your impact on your field with our robust analytics

Discover new research

Get access to millions of research papers and stay informed with the important topics around the world

Publish your work

Publish your research with fast and rigorous service through Academia.edu Publishing. Get instant worldwide dissemination of your work

Unlock the most powerful tools with Academia Premium

Work faster and smarter with advanced research discovery tools

Search the full text and citations of our millions of papers. Download groups of related papers to jumpstart your research. Save time with detailed summaries and search alerts.

- Advanced Search

- PDF Packages of 37 papers

- Summaries and Search Alerts

Share your work, track your impact, and grow your audience

Get notified when other academics mention you or cite your papers. Track your impact with in-depth analytics and network with members of your field.

- Mentions and Citations Tracking

- Advanced Analytics

- Publishing Tools

Real stories from real people

Used by academics at over 16,000 universities

Get started and find the best quality research

- Academia.edu Publishing

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Cognitive Science

- Academia ©2024

Reference management. Clean and simple.

The top list of academic research databases

2. Web of Science

5. ieee xplore, 6. sciencedirect, 7. directory of open access journals (doaj), get the most out of your academic research database, frequently asked questions about academic research databases, related articles.

Whether you are writing a thesis , dissertation, or research paper it is a key task to survey prior literature and research findings. More likely than not, you will be looking for trusted resources, most likely peer-reviewed research articles.

Academic research databases make it easy to locate the literature you are looking for. We have compiled the top list of trusted academic resources to help you get started with your research:

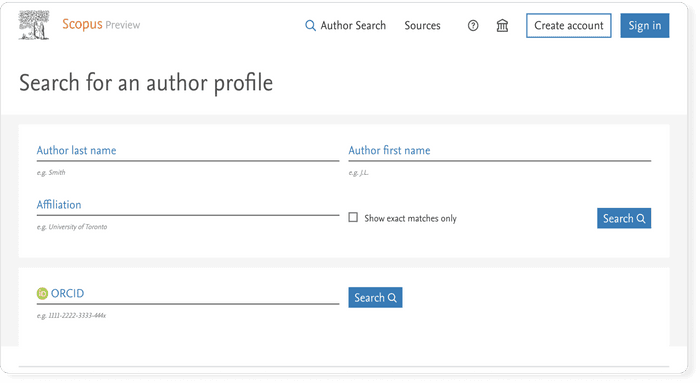

Scopus is one of the two big commercial, bibliographic databases that cover scholarly literature from almost any discipline. Besides searching for research articles, Scopus also provides academic journal rankings, author profiles, and an h-index calculator .

- Coverage: 90.6 million core records

- References: N/A

- Discipline: Multidisciplinary

- Access options: Limited free preview, full access by institutional subscription only

- Provider: Elsevier

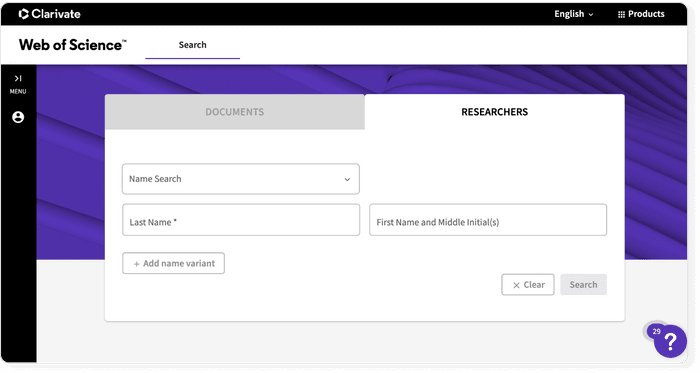

Web of Science also known as Web of Knowledge is the second big bibliographic database. Usually, academic institutions provide either access to Web of Science or Scopus on their campus network for free.

- Coverage: approx. 100 million items

- References: 1.4 billion

- Access options: institutional subscription only

- Provider: Clarivate (formerly Thomson Reuters)

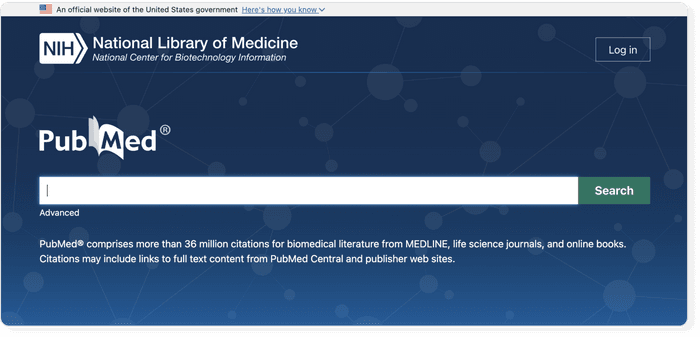

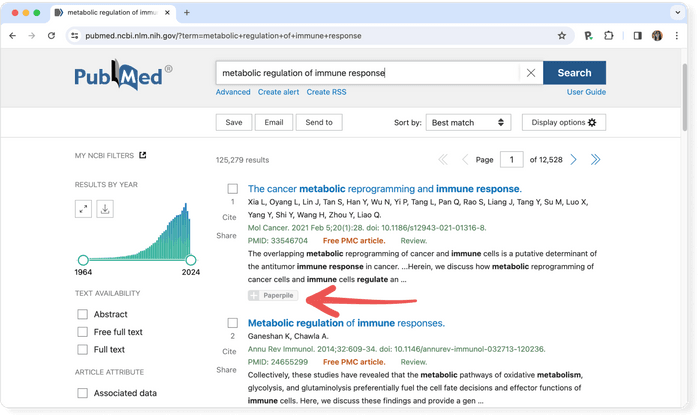

PubMed is the number one resource for anyone looking for literature in medicine or biological sciences. PubMed stores abstracts and bibliographic details of more than 30 million papers and provides full text links to the publisher sites or links to the free PDF on PubMed Central (PMC) .

- Coverage: approx. 35 million items

- Discipline: Medicine and Biological Sciences

- Access options: free

- Provider: NIH

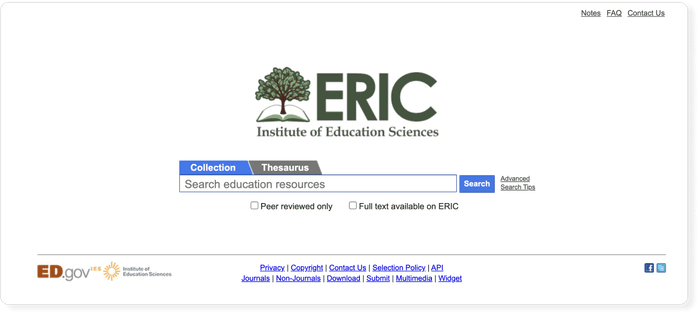

For education sciences, ERIC is the number one destination. ERIC stands for Education Resources Information Center, and is a database that specifically hosts education-related literature.

- Coverage: approx. 1.6 million items

- Discipline: Education

- Provider: U.S. Department of Education

IEEE Xplore is the leading academic database in the field of engineering and computer science. It's not only journal articles, but also conference papers, standards and books that can be search for.

- Coverage: approx. 6 million items

- Discipline: Engineering

- Provider: IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers)

ScienceDirect is the gateway to the millions of academic articles published by Elsevier, 1.4 million of which are open access. Journals and books can be searched via a single interface.

- Coverage: approx. 19.5 million items

The DOAJ is an open-access academic database that can be accessed and searched for free.

- Coverage: over 8 million records

- Provider: DOAJ

JSTOR is another great resource to find research papers. Any article published before 1924 in the United States is available for free and JSTOR also offers scholarships for independent researchers.

- Coverage: more than 12 million items

- Provider: ITHAKA

Start using a reference manager like Paperpile to save, organize, and cite your references. Paperpile integrates with PubMed and many popular databases, so you can save references and PDFs directly to your library using the Paperpile buttons:

Scopus is one of the two big commercial, bibliographic databases that cover scholarly literature from almost any discipline. Beside searching for research articles, Scopus also provides academic journal rankings, author profiles, and an h-index calculator .

PubMed is the number one resource for anyone looking for literature in medicine or biological sciences. PubMed stores abstracts and bibliographic details of more than 30 million papers and provides full text links to the publisher sites or links to the free PDF on PubMed Central (PMC)

A free, AI-powered research tool for scientific literature

- Timothy Nyerges

- Price Index

- Moral Reasoning

New & Improved API for Developers

Introducing semantic reader in beta.

Stay Connected With Semantic Scholar Sign Up What Is Semantic Scholar? Semantic Scholar is a free, AI-powered research tool for scientific literature, based at the Allen Institute for AI.

21 Legit Research Databases for Free Journal Articles in 2024

#scribendiinc

Written by Scribendi

Has this ever happened to you? While looking for websites for research, you come across a research paper site that claims to connect academics to a peer-reviewed article database for free.

Intrigued, you search for keywords related to your topic, only to discover that you must pay a hefty subscription fee to access the service. After the umpteenth time being duped, you begin to wonder if there's even such a thing as free journal articles.

Subscription fees and paywalls are often the bane of students and academics, especially those at small institutions who don't provide access to many free article directories and repositories.

Whether you're working on an undergraduate paper, a PhD dissertation, or a medical research study, we want to help you find tools to locate and access the information you need to produce well-researched, compelling, and innovative work.

Below, we discuss why peer-reviewed articles are superior and list out the best free article databases to use in 2024.

Download Our Free Research Database Roundup PDF

Why peer-reviewed scholarly journal articles are more authoritative.

Determining what sources are reliable can be challenging. Peer-reviewed scholarly journal articles are the gold standard in academic research. Reputable academic journals have a rigorous peer-review process.

The peer review process provides accountability to the academic community, as well as to the content of the article. The peer review process involves qualified experts in a specific (often very specific) field performing a review of an article's methods and findings to determine things like quality and credibility.

Peer-reviewed articles can be found in peer-reviewed article databases and research databases, and if you know that a database of journals is reliable, that can offer reassurances about the reliability of a free article. Peer review is often double blind, meaning that the author removes all identifying information and, likewise, does not know the identity of the reviewers. This helps reviewers maintain objectivity and impartiality so as to judge an article based on its merit.

Where to Find Peer-Reviewed Articles

Peer-reviewed articles can be found in a variety of research databases. Below is a list of some of the major databases you can use to find peer-reviewed articles and other sources in disciplines spanning the humanities, sciences, and social sciences.

What Are Open Access Journals?

An open access (OA) journal is a journal whose content can be accessed without payment. This provides scholars, students, and researchers with free journal articles. OA journals use alternate methods of funding to cover publication costs so that articles can be published without having to pass those publication costs on to the reader.

Some of these funding models include standard funding methods like advertising, public funding, and author payment models, where the author pays a fee in order to publish in the journal. There are OA journals that have non-peer-reviewed academic content, as well as journals that focus on dissertations, theses, and papers from conferences, but the main focus of OA is peer-reviewed scholarly journal articles.

The internet has certainly made it easier to access research articles and other scholarly publications without needing access to a university library, and OA takes another step in that direction by removing financial barriers to academic content.

Choosing Wisely

Features of legitimate oa journals.

There are things to look out for when trying to decide if a free publication journal is legitimate:

Mission statement —The mission statement for an OA journal should be available on their website.

Publication history —Is the journal well established? How long has it been available?

Editorial board —Who are the members of the editorial board, and what are their credentials?

Indexing —Can the journal be found in a reliable database?

Peer review —What is the peer review process? Does the journal allow enough time in the process for a reliable assessment of quality?

Impact factor —What is the average number of times the journal is cited over a two-year period?

Features of Illegitimate OA Journals

There are predatory publications that take advantage of the OA format, and they are something to be wary of. Here are some things to look out for:

Contact information —Is contact information provided? Can it be verified?

Turnaround —If the journal makes dubious claims about the amount of time from submission to publication, it is likely unreliable.

Editorial board —Much like determining legitimacy, looking at the editorial board and their credentials can help determine illegitimacy.

Indexing —Can the journal be found in any scholarly databases?

Peer review —Is there a statement about the peer review process? Does it fit what you know about peer review?

How to Find Scholarly Articles

Identify keywords.

Keywords are included in an article by the author. Keywords are an excellent way to find content relevant to your research topic or area of interest. In academic searches, much like you would on a search engine, you can use keywords to navigate through what is available to find exactly what you're looking for.

Authors provide keywords that will help you easily find their article when researching a related topic, often including general terms to accommodate broader searches, as well as some more specific terms for those with a narrower scope. Keywords can be used individually or in combination to refine your scholarly article search.

Narrow Down Results

Sometimes, search results can be overwhelming, and searching for free articles on a journal database is no exception, but there are multiple ways to narrow down your results. A good place to start is discipline.

What category does your topic fall into (psychology, architecture, machine learning, etc.)? You can also narrow down your search with a year range if you're looking for articles that are more recent.

A Boolean search can be incredibly helpful. This entails including terms like AND between two keywords in your search if you need both keywords to be in your results (or, if you are looking to exclude certain keywords, to exclude these words from the results).

Consider Different Avenues

If you're not having luck using keywords in your search for free articles, you may still be able to find what you're looking for by changing your tactics. Casting a wider net sometimes yields positive results, so it may be helpful to try searching by subject if keywords aren't getting you anywhere.

You can search for a specific publisher to see if they have OA publications in the academic journal database. And, if you know more precisely what you're looking for, you can search for the title of the article or the author's name.

Determining the Credibility of Scholarly Sources

Ensuring that sources are both credible and reliable is crucial to academic research. Use these strategies to help evaluate the usefulness of scholarly sources:

- Peer Review : Look for articles that have undergone a rigorous peer-review process. Peer-reviewed articles are typically vetted by experts in the field, ensuring the accuracy of the research findings.

Tip: To determine whether an article has undergone rigorous peer review, review the journal's editorial policies, which are often available on the journal's website. Look for information about the peer-review process, including the criteria for selecting reviewers, the process for handling conflicts of interest, and any transparency measures in place.

- Publisher Reputation : Consider the reputation of the publisher. Established publishers, such as well-known academic journals, are more likely to adhere to high editorial standards and publishing ethics.

- Author Credentials : Evaluate the credentials and expertise of the authors. Check their affiliations, academic credentials, and past publications to assess their authority in the field.

- Citations and References : Examine the citations and references provided in the article. A well-researched article will cite credible sources to support its arguments and findings. Verify the accuracy of the cited sources and ensure they are from reputable sources.

- Publication Date : Consider the publication date of the article. While older articles may still be relevant, particularly in certain fields, it is best to prioritize recent publications for up-to-date research and findings.

- Journal Impact Factor : Assess the journal's impact factor or other metrics that indicate its influence and reputation within the academic community. Higher impact factor journals are generally considered more prestigious and reliable.

Tip: Journal Citation Reports (JCR), produced by Clarivate Analytics, is a widely used source for impact factor data. You can access JCR through academic libraries or directly from the Clarivate Analytics website if you have a subscription.

- Peer Recommendations : Seek recommendations from peers, mentors, or professors in your field. They can provide valuable insights and guidance on reputable sources and journals within your area of study.

- Cross-Verification : Cross-verify the information presented in the article with other credible sources. Compare findings, methodologies, and conclusions with similar studies to ensure consistency and reliability.

By employing these strategies, researchers can confidently evaluate the credibility and reliability of scholarly sources, ensuring the integrity of their research contributions in an ever-evolving landscape.

The Top 21 Free Online Journal and Research Databases

Navigating OA journals, research article databases, and academic websites trying to find high-quality sources for your research can really make your head spin. What constitutes a reliable database? What is a useful resource for your discipline and research topic? How can you find and access full-text, peer-reviewed articles?

Fortunately, we're here to help. Having covered some of the ins and outs of peer review, OA journals, and how to search for articles, we have compiled a list of the top 21 free online journals and the best research databases. This list of databases is a great resource to help you navigate the wide world of academic research.

These databases provide a variety of free sources, from abstracts and citations to full-text, peer-reviewed OA journals. With databases covering specific areas of research and interdisciplinary databases that provide a variety of material, these are some of our favorite free databases, and they're totally legit!

CORE is a multidisciplinary aggregator of OA research. CORE has the largest collection of OA articles available. It allows users to search more than 219 million OA articles. While most of these link to the full-text article on the original publisher's site, or to a PDF available for download, five million records are hosted directly on CORE.

CORE's mission statement is a simple and straightforward commitment to offering OA articles to anyone, anywhere in the world. They also host communities that are available for researchers to join and an ambassador community to enhance their services globally. In addition to a straightforward keyword search, CORE offers advanced search options to filter results by publication type, year, language, journal, repository, and author.

CORE's user interface is easy to use and navigate. Search results can be sorted based on relevance or recency, and you can search for relevant content directly from the results screen.

Collection : 219,537,133 OA articles

Other Services : Additional services are available from CORE, with extras that are geared toward researchers, repositories, and businesses. There are tools for accessing raw data, including an API that provides direct access to data, datasets that are available for download, and FastSync for syncing data content from the CORE database.

CORE has a recommender plug-in that suggests relevant OA content in the database while conducting a search and a discovery feature that helps you discover OA versions of paywalled articles. Other features include tools for managing content, such as a dashboard for managing repository output and the Repository Edition service to enhance discoverability.

Good Source of Peer-Reviewed Articles : Yes

Advanced Search Options : Language, author, journal, publisher, repository, DOI, year

2. ScienceOpen

Functioning as a research and publishing network, ScienceOpen offers OA to more than 74 million articles in all areas of science. Although you do need to register to view the full text of articles, registration is free. The advanced search function is highly detailed, allowing you to find exactly the research you're looking for.

The Berlin- and Boston-based company was founded in 2013 to "facilitate open and public communications between academics and to allow ideas to be judged on their merit, regardless of where they come from." Search results can be exported for easy integration with reference management systems.

You can also bookmark articles for later research. There are extensive networking options, including your Science Open profile, a forum for interacting with other researchers, the ability to track your usage and citations, and an interactive bibliography. Users have the ability to review articles and provide their knowledge and insight within the community.

Collection : 74,560,631

Other Services : None

Advanced Search Options : Content type, source, author, journal, discipline

3. Directory of Open Access Journals

A multidisciplinary, community-curated directory, the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) gives researchers access to high-quality peer-reviewed journals. It has archived more than two million articles from 17,193 journals, allowing you to either browse by subject or search by keyword.

The site was launched in 2003 with the aim of increasing the visibility of OA scholarly journals online. Content on the site covers subjects from science, to law, to fine arts, and everything in between. DOAJ has a commitment to "increase the visibility, accessibility, reputation, usage and impact of quality, peer-reviewed, OA scholarly research journals globally, regardless of discipline, geography or language."

Information about the journal is available with each search result. Abstracts are also available in a collapsible format directly from the search screen. The scholarly article website is somewhat simple, but it is easy to navigate. There are 16 principles of transparency and best practices in scholarly publishing that clearly outline DOAJ policies and standards.

Collection : 6,817,242

Advanced Search Options : Subject, journal, year

4. Education Resources Information Center

The Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) of the Institution of Education Sciences allows you to search by topic for material related to the field of education. Links lead to other sites, where you may have to purchase the information, but you can search for full-text articles only. You can also search only peer-reviewed sources.

The service primarily indexes journals, gray literature (such as technical reports, white papers, and government documents), and books. All sources of material on ERIC go through a formal review process prior to being indexed. ERIC's selection policy is available as a PDF on their website.

The ERIC website has an extensive FAQ section to address user questions. This includes categories like general questions, peer review, and ERIC content. There are also tips for advanced searches, as well as general guidance on the best way to search the database. ERIC is an excellent database for content specific to education.

Collection : 1,292,897

Advanced Search Options : Boolean

5. arXiv e-Print Archive

The arXiv e-Print Archive is run by Cornell University Library and curated by volunteer moderators, and it now offers OA to more than one million e-prints.

There are advisory committees for all eight subjects available on the database. With a stated commitment to an "emphasis on openness, collaboration, and scholarship," the arXiv e-Print Archive is an excellent STEM resource.

The interface is not as user-friendly as some of the other databases available, and the website hosts a blog to provide news and updates, but it is otherwise a straightforward math and science resource. There are simple and advanced search options, and, in addition to conducting searches for specific topics and articles, users can browse content by subject. The arXiv e-Print Archive clearly states that they do not peer review the e-prints in the database.

Collection : 1,983,891

Good Source of Peer-Reviewed Articles : No

Advanced Search Options : Subject, date, title, author, abstract, DOI

6. Social Science Research Network

The Social Science Research Network (SSRN) is a collection of papers from the social sciences community. It is a highly interdisciplinary platform used to search for scholarly articles related to 67 social science topics. SSRN has a variety of research networks for the various topics available through the free scholarly database.

The site offers more than 700,000 abstracts and more than 600,000 full-text papers. There is not yet a specific option to search for only full-text articles, but, because most of the papers on the site are free access, it's not often that you encounter a paywall. There is currently no option to search for only peer-reviewed articles.

You must become a member to use the services, but registration is free and enables you to interact with other scholars around the world. SSRN is "passionately committed to increasing inclusion, diversity and equity in scholarly research," and they encourage and discuss the use of inclusive language in scholarship whenever possible.

Collection : 1,058,739 abstracts; 915,452 articles

Advanced Search Options : Term, author, date, network

7. Public Library of Science

Public Library of Science (PLOS) is a big player in the world of OA science. Publishing 12 OA journals, the nonprofit organization is committed to facilitating openness in academic research. According to the site, "all PLOS content is at the highest possible level of OA, meaning that scientific articles are immediately and freely available to anyone, anywhere."

PLOS outlines four fundamental goals that guide the organization: break boundaries, empower researchers, redefine quality, and open science. All PLOS journals are peer-reviewed, and all 12 journals uphold rigorous ethical standards for research, publication, and scientific reporting.

PLOS does not offer advanced search options. Content is organized by topic into research communities that users can browse through, in addition to options to search for both articles and journals. The PLOS website also has resources for peer reviewers, including guidance on becoming a reviewer and on how to best participate in the peer review process.

Collection : 12 journals

Advanced Search Options : None

8. OpenDOAR

OpenDOAR, or the Directory of Open Access Repositories, is a comprehensive resource for finding free OA journals and articles. Using Google Custom Search, OpenDOAR combs through OA repositories around the world and returns relevant research in all disciplines.

The repositories it searches through are assessed and categorized by OpenDOAR staff to ensure they meet quality standards. Inclusion criteria for the database include requirements for OA content, global access, and categorically appropriate content, in addition to various other quality assurance measures. OpenDOAR has metadata, data, content, preservation, and submission policies for repositories, in addition to two OA policy statements regarding minimum and optimum recommendations.

This database allows users to browse and search repositories, which can then be selected, and articles and data can be accessed from the repository directly. As a repository database, much of the content on the site is geared toward the support of repositories and OA standards.

Collection : 5,768 repositories

Other Services : OpenDOAR offers a variety of additional services. Given the nature of the platform, services are primarily aimed at repositories and institutions, and there is a marked focus on OA in general. Sherpa services are OA archiving tools for authors and institutions.

They also offer various resources for OA support and compliance regarding standards and policies. The publication router matches publications and publishers with appropriate repositories.

There are also services and resources from JISC for repositories for cost management, discoverability, research impact, and interoperability, including ORCID consortium membership information. Additionally, a repository self-assessment tool is available for members.

Advanced Search Options : Name, organization name, repository type, software name, content type, subject, country, region

9. Bielefeld Academic Search Engine

The Bielefeld Academic Search Engine (BASE) is operated by the Bielefeld University Library in Germany, and it offers more than 240 million documents from more than 8,000 sources. Sixty percent of its content is OA, and you can filter your search accordingly.

BASE has rigorous inclusion requirements for content providers regarding quality and relevance, and they maintain a list of content providers for the sake of transparency, which can be easily found on their website. BASE has a fairly elegant interface. Search results can be organized by author, title, or date.

From the search results, items can be selected and exported, added to favorites, emailed, and searched in Google Scholar. There are basic and advanced search features, with the advanced search offering numerous options for refining search criteria. There is also a feature on the website that saves recent searches without additional steps from the user.

Collection : 276,019,066 documents; 9,286 content providers

Advanced Search Options : Author, subject, year, content provider, language, document type, access, terms of reuse

10. Digital Library of the Commons Repository

Run by Indiana University, the Digital Library of the Commons (DLC) Repository is a multidisciplinary journal repository that allows users to access thousands of free and OA articles from around the world. You can browse by document type, date, author, title, and more or search for keywords relevant to your topic.

DCL also offers the Comprehensive Bibliography of the Commons, an image database, and a keyword thesaurus for enhanced search parameters. The repository includes books, book chapters, conference papers, journal articles, surveys, theses and dissertations, and working papers. DCL advanced search features drop-down menus of search types with built-in Boolean search options.

Searches can be sorted by relevance, title, date, or submission date in ascending or descending order. Abstracts are included in selected search results, with access to full texts available, and citations can be exported from the same page. Additionally, the image database search includes tips for better search results.

Collection : 10,784

Advanced Search Options : Author, date, title, subject, sector, region, conference

11. CIA World Factbook

The CIA World Factbook is a little different from the other resources on this list in that it is not an online journal directory or repository. It is, however, a useful free online research database for academics in a variety of disciplines.

All the information is free to access, and it provides facts about every country in the world, which are organized by category and include information about history, geography, transportation, and much more. The World Factbook can be searched by country or region, and there is also information about the world's oceans.

This site contains resources related to the CIA as an organization rather than being a scientific journal database specifically. The site has a user interface that is easy to navigate. The site also provides a section for updates regarding changes to what information is available and how it is organized, making it easier to interact with the information you are searching for.

Collection : 266 countries

12. Paperity

Paperity boasts its status as the "first multidisciplinary aggregator of OA journals and papers." Their focus is on helping you avoid paywalls while connecting you to authoritative research. In addition to providing readers with easy access to thousands of journals, Paperity seeks to help authors reach their audiences and help journals increase their exposure to boost readership.

Paperity has journal articles for every discipline, and the database offers more than a dozen advanced search options, including the length of the paper and the number of authors. There is even an option to include, exclude, or exclusively search gray papers.

Paperity is available for mobile, with both a mobile site and the Paperity Reader, an app that is available for both Android and Apple users. The database is also available on social media. You can interact with Paperity via Twitter and Facebook, and links to their social media are available on their homepage, including their Twitter feed.

Collection : 8,837,396

Advanced Search Options : Title, abstract, journal title, journal ISSN, publisher, year of publication, number of characters, number of authors, DOI, author, affiliation, language, country, region, continent, gray papers

13. dblp Computer Science Bibliography

The dblp Computer Science Bibliography is an online index of major computer science publications. dblp was founded in 1993, though until 2010 it was a university-specific database at the University of Trier in Germany. It is currently maintained by the Schloss Dagstuhl – Leibniz Center for Informatics.

Although it provides access to both OA articles and those behind a paywall, you can limit your search to only OA articles. The site indexes more than three million publications, making it an invaluable resource in the world of computer science. dblp entries are color-coded based on the type of item.

dblp has an extensive FAQ section, so questions that might arise about topics like the database itself, navigating the website, or the data on dblp, in addition to several other topics, are likely to be answered. The website also hosts a blog and has a section devoted to website statistics.

Collection : 5,884,702

14. EconBiz

EconBiz is a great resource for economic and business studies. A service of the Leibniz Information Centre for Economics, it offers access to full texts online, with the option of searching for OA material only. Their literature search is performed across multiple international databases.

EconBiz has an incredibly useful research skills section, with resources such as Guided Walk, a service to help students and researchers navigate searches, evaluate sources, and correctly cite references; the Research Guide EconDesk, a help desk to answer specific questions and provide advice to aid in literature searches; and the Academic Career Kit for what they refer to as Early Career Researchers.

Other helpful resources include personal literature lists, a calendar of events for relevant calls for papers, conferences, and workshops, and an economics terminology thesaurus to help in finding keywords for searches. To stay up-to-date with EconBiz, you can sign up for their newsletter.

Collection : 1,075,219

Advanced Search Options : Title, subject, author, institution, ISBN/ISSN, journal, publisher, language, OA only

15. BioMed Central

BioMed Central provides OA research from more than 300 peer-reviewed journals. While originally focused on resources related to the physical sciences, math, and engineering, BioMed Central has branched out to include journals that cover a broader range of disciplines, with the aim of providing a single platform that provides OA articles for a variety of research needs. You can browse these journals by subject or title, or you can search all articles for your required keyword.

BioMed Central has a commitment to peer-reviewed sources and to the peer review process itself, continually seeking to help and improve the peer review process. They're "committed to maintaining high standards through full and stringent peer review." They publish the journal Research Integrity and Peer Review , which publishes research on the subject.

Additionally, the website includes resources to assist and support editors as part of their commitment to providing high-quality, peer-reviewed OA articles.

Collection : 507,212

Other Services : BMC administers the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) registry. While initially designed for registering clinical trials, since its creation in 2000, the registry has broadened its scope to include other health studies as well.

The registry is recognized by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, as well as the World Health Organization (WHO), and it meets the requirements established by the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform.

The study records included in the registry are all searchable and free to access. The ISRCTN registry "supports transparency in clinical research, helps reduce selective reporting of results and ensures an unbiased and complete evidence base."

Advanced Search Options : Author, title, journal, list

A multidisciplinary search engine, JURN provides links to various scholarly websites, articles, and journals that are free to access or OA. Covering the fields of the arts, humanities, business, law, nature, science, and medicine, JURN has indexed almost 5,000 repositories to help you find exactly what you're looking for.

Search features are enhanced by Google, but searches are filtered through their index of repositories. JURN seeks to reach a wide audience, with their search engine tailored to researchers from "university lecturers and students seeking a strong search tool for OA content" and "advanced and ambitious students, age 14-18" to "amateur historians and biographers" and "unemployed and retired lecturers."

That being said, JURN is very upfront about its limitations. They admit to not being a good resource for educational studies, social studies, or psychology, and conference archives are generally not included due to frequently unstable URLs.

Collection : 5,064 indexed journals

Other Services : JURN has a browser add-on called UserScript. This add-on allows users to integrate the JURN database directly into Google Search. When performing a search through Google, the add-on creates a link that sends the search directly to JURN CSE. JURN CSE is a search service that is hosted by Google.

Clicking the link from the Google Search bar will run your search through the JURN database from the Google homepage. There is also an interface for a DuckDuckGo search box; while this search engine has an emphasis on user privacy, for smaller sites that may be indexed by JURN, DuckDuckGo may not provide the same depth of results.

Advanced Search Options : Google search modifiers

Dryad is a digital repository of curated, OA scientific research data. Launched in 2009, it is run by a not-for-profit membership organization, with a community of institutional and publisher members for whom their services have been designed. Members include institutions such as Stanford, UCLA, and Yale, as well as publishers like Oxford University Press and Wiley.

Dryad aims to "promote a world where research data is openly available, integrated with the scholarly literature, and routinely reused to create knowledge." It is free to access for the search and discovery of data. Their user experience is geared toward easy self-depositing, supports Creative Commons licensing, and provides DOIs for all their content.

Note that there is a publishing charge associated if you wish to publish your data in Dryad. When searching datasets, they are accompanied by author information and abstracts for the associated studies, and citation information is provided for easy attribution.

Collection : 44,458

Advanced Search Options : No

Run by the British Library, the E-Theses Online Service (EThOS) allows you to search over 500,000 doctoral theses in a variety of disciplines. All of the doctoral theses available on EThOS have been awarded by higher education institutions in the United Kingdom.

Although some full texts are behind paywalls, you can limit your search to items available for immediate download, either directly through EThOS or through an institution's website. More than half of the records in the database provide access to full-text theses.

EThOS notes that they do not hold all records for all institutions, but they strive to index as many doctoral theses as possible, and the database is constantly expanding, with approximately 3,000 new records added and 2,000 new full-text theses available every month. The availability of full-text theses is dependent on multiple factors, including their availability in the institutional repository and the level of repository development.

Collection : 500,000+

Advanced Search Options : Abstract, author's first name, author's last name, awarding body, current institution, EThOS ID, year, language, qualifications, research supervisor, sponsor/funder, keyword, title

PubMed is a research platform well-known in the fields of science and medicine. It was created and developed by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) at the National Library of Medicine (NLM). It has been available since 1996 and offers access to "more than 33 million citations for biomedical literature from MEDLINE, life science journals, and online books."

While PubMed does not provide full-text articles directly, and many full-text articles may be behind paywalls or require subscriptions to access them, when articles are available from free sources, such as through PubMed Central (PMC), those links are provided with the citations and abstracts that PubMed does provide.

PMC, which was established in 2000 by the NLM, is a free full-text archive that includes more than 6,000,000 records. PubMed records link directly to corresponding PMC results. PMC content is provided by publishers and other content owners, digitization projects, and authors directly.

Collection : 33,000,000+

Advanced Search Options : Author's first name, author's last name, identifier, corporation, date completed, date created, date entered, date modified, date published, MeSH, book, conflict of interest statement, EC/RN number, editor, filter, grant number, page number, pharmacological action, volume, publication type, publisher, secondary source ID, text, title, abstract, transliterated title

20. Semantic Scholar

A unique and easy-to-use resource, Semantic Scholar defines itself not just as a research database but also as a "search and discovery tool." Semantic Scholar harnesses the power of artificial intelligence to efficiently sort through millions of science-related papers based on your search terms.

Through this singular application of machine learning, Semantic Scholar expands search results to include topic overviews based on your search terms, with the option to create an alert for or further explore the topic. It also provides links to related topics.

In addition, search results produce "TLDR" summaries in order to provide concise overviews of articles and enhance your research by helping you to navigate quickly and easily through the available literature to find the most relevant information. According to the site, although some articles are behind paywalls, "the data [they] have for those articles is limited," so you can expect to receive mostly full-text results.

Collection : 203,379,033

Other Services : Semantic Scholar supports multiple popular browsers. Content can be accessed through both mobile and desktop versions of Firefox, Microsoft Edge, Google Chrome, Apple Safari, and Opera.

Additionally, Semantic Scholar provides browser extensions for both Chrome and Firefox, so AI-powered scholarly search results are never more than a click away. The mobile interface includes an option for Semantic Swipe, a new way of interacting with your research results.

There are also beta features that can be accessed as part of the Beta Program, which will provide you with features that are being actively developed and require user feedback for further improvement.

Advanced Search Options : Field of study, date range, publication type, author, journal, conference, PDF

Zenodo, powered by the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), was launched in 2013. Taking its name from Zenodotus, the first librarian of the ancient library of Alexandria, Zenodo is a tool "built and developed by researchers, to ensure that everyone can join in open science." Zenodo accepts all research from every discipline in any file format.

However, Zenodo also curates uploads and promotes peer-reviewed material that is available through OA. A DOI is assigned to everything that is uploaded to Zenodo, making research easily findable and citable. You can sort by keyword, title, journal, and more and download OA documents directly from the site.

While there are closed access and restricted access items in the database, the vast majority of research is OA material. Search results can be filtered by access type, making it easy to view the free articles available in the database.

Collection : 2,220,000+

Advanced Search Options : Access, file type, keywords

Check out our roundup of free research databases as a handy one-page PDF.

How to find peer-reviewed articles.

There are a lot of free scholarly articles available from various sources. The internet is a big place. So how do you go about finding peer-reviewed articles when conducting your research? It's important to make sure you are using reputable sources.

The first source of the article is the person or people who wrote it. Checking out the author can give you some initial insight into how much you can trust what you’re reading. Looking into the publication information of your sources can also indicate whether the article is reliable.

Aspects of the article, such as subject and audience, tone, and format, are other things you can look at when evaluating whether the article you're using is valid, reputable, peer-reviewed material. So, let's break that down into various components so you can assess your research to ensure that you're using quality articles and conducting solid research.

Check the Author

Peer-reviewed articles are written by experts or scholars with experience in the field or discipline they're writing about. The research in a peer-reviewed article has to pass a rigorous evaluation process, so it's a foregone conclusion that the author(s) of a peer-reviewed article should have experience or training related to that research.

When evaluating an article, take a look at the author's information. What credentials does the author have to indicate that their research has scholarly weight behind it? Finding out what type of degree the author has—and what that degree is in—can provide insight into what kind of authority the author is on the subject.

Something else that might lend credence to the author's scholarly role is their professional affiliation. A look at what organization or institution they are affiliated with can tell you a lot about their experience or expertise. Where were they trained, and who is verifying their research?

Identify Subject and Audience

The ultimate goal of a study is to answer a question. Scholarly articles are also written for scholarly audiences, especially articles that have gone through the peer review process. This means that the author is trying to reach experts, researchers, academics, and students in the field or topic the research is based on.

Think about the question the author is trying to answer by conducting this research, why, and for whom. What is the subject of the article? What question has it set out to answer? What is the purpose of finding the information? Is the purpose of the article of importance to other scholars? Is it original content?

Research should also be approached analytically. Is the methodology sound? Is the author using an analytical approach to evaluate the data that they have obtained? Are the conclusions they've reached substantiated by their data and analysis? Answering these questions can reveal a lot about the article's validity.

Format Matters

Reliable articles from peer-reviewed sources have certain format elements to be aware of. The first is an abstract. An abstract is a short summary or overview of the article. Does the article have an abstract? It's unlikely that you're reading a peer-reviewed article if it doesn't. Peer-reviewed journals will also have a word count range. If an article seems far too short or incredibly long, that may be reason to doubt it.

Another feature of reliable articles is the sections the information is divided into. Peer-reviewed research articles will have clear, concise sections that appropriately organize the information. This might include a literature review, methodology, and results in the case of research articles and a conclusion.

One of the most important sections is the references or bibliography. This is where the researcher lists all the sources of their information. A peer-reviewed source will have a comprehensive reference section.

An article that has been written to reach an academic community will have an academic tone. The language that is used, and the way this language is used, is important to consider. If the article is riddled with grammatical errors, confusing syntax, and casual language, it almost definitely didn't make it through the peer review process.

Also consider the use of terminology. Every discipline is going to have standard terminology or jargon that can be used and understood by other academics in the discipline. The language in a peer-reviewed article is going to reflect that.

If the author is going out of their way to explain simple terms, or terms that are standard to the field or discipline, it's unlikely that the article has been peer reviewed, as this is something that the author would be asked to address during the review process.

Publication

The source of the article will be a very good indicator of the likelihood that it was peer reviewed. Where was the article published? Was it published alongside other academic articles in the same discipline? Is it a legitimate and reputable scholarly publication?

A trade publication or newspaper might be legitimate or reputable, but it is not a scholarly source, and it will not have been subject to the peer review process. Scholarly journals are the best resource for peer-reviewed articles, but it's important to remember that not all scholarly journals are peer reviewed.

It's helpful to look at a scholarly source's website, as peer-reviewed journals will have a clear indication of the peer review process. University libraries, institutional repositories, and reliable databases (and you now might have a list of some legit ones) can also help provide insight into whether an article comes from a peer-reviewed journal.

Common Research Mistakes to Avoid

Research is a lot of work. Even with high standards and good intentions, it's easy to make mistakes. Perhaps you searched for access to scientific journals for free and found the perfect peer-reviewed sources, but you forgot to document everything, and your references are a mess. Or, you only searched for free online articles and missed out on a ground-breaking study that was behind a paywall.

Whether your research is for a degree or to get published or to satisfy your own inquisitive nature, or all of the above, you want all that work to produce quality results. You want your research to be thorough and accurate.

To have any hope of contributing to the literature on your research topic, your results need to be high quality. You might not be able to avoid every potential mistake, but here are some that are both common and easy to avoid.

Sticking to One Source

One of the hallmarks of good research is a healthy reference section. Using a variety of sources gives you a better answer to your question. Even if all of the literature is in agreement, looking at various aspects of the topic may provide you with an entirely different picture than you would have if you looked at your research question from only one angle.

Not Documenting Every Fact

As you conduct your research, do yourself a favor and write everything down. Everything you include in your paper or article that you got from another source is going to need to be added to your references and cited.

It's important, especially if your aim is to conduct ethical, high-quality research, that all of your research has proper attribution. If you don't document as you go, you could end up making a lot of work for yourself if the information you don't write down is something that later, as you write your paper, you really need.

Using Outdated Materials

Academia is an ever-changing landscape. What was true in your academic discipline or area of research ten years ago may have since been disproven. If fifteen studies have come out since the article that you're using was published, it's more than a little likely that you're going to be basing your research on flawed or dated information.

If the information you're basing your research on isn't as up-to-date as possible, your research won't be of quality or able to stand up to any amount of scrutiny. You don't want all of your hard work to be for naught.

Relying Solely on Open Access Journals

OA is a great resource for conducting academic research. There are high-quality journal articles available through OA, and that can be very helpful for your research. But, just because you have access to free articles, that doesn't mean that there's nothing to be found behind a paywall.

Just as dismissing high-quality peer-reviewed articles because they are OA would be limiting, not exploring any paid content at all is equally short-sighted. If you're seeking to conduct thorough and comprehensive research, exploring all of your options for quality sources is going to be to your benefit.

Digging Too Deep or Not Deep Enough

Research is an art form, and it involves a delicate balance of information. If you conduct your research using only broad search terms, you won't be able to answer your research question well, or you'll find that your research provides information that is closely related to your topic but, ultimately, your findings are vague and unsubstantiated.

On the other hand, if you delve deeply into your research topic with specific searches and turn up too many sources, you might have a lot of information that is adjacent to your topic but without focus and perhaps not entirely relevant. It's important to answer your research question concisely but thoroughly.

Different Types of Scholarly Articles

Different types of scholarly articles have different purposes. An original research article, also called an empirical article, is the product of a study or an experiment. This type of article seeks to answer a question or fill a gap in the existing literature.

Research articles will have a methodology, results, and a discussion of the findings of the experiment or research and typically a conclusion.

Review articles overview the current literature and research and provide a summary of what the existing research indicates or has concluded. This type of study will have a section for the literature review, as well as a discussion of the findings of that review. Review articles will have a particularly extensive reference or bibliography section.

Theoretical articles draw on existing literature to create new theories or conclusions, or look at current theories from a different perspective, to contribute to the foundational knowledge of the field of study.

10 Tips for Navigating Journal Databases

Use the right academic journal database for your search, be that interdisciplinary or specific to your field. Or both!

If it's an option, set the search results to return only peer-reviewed sources.

Start by using search terms that are relevant to your topic without being overly specific.

Try synonyms, especially if your keywords aren't returning the desired results.

Even if you've found some good articles, try searching using different terms.

Explore the advanced search features of the database(s).

Learn to use Booleans (AND, OR, NOT) to expand or narrow your results.

Once you've gotten some good results from a more general search, try narrowing your search.

Read through abstracts when trying to find articles relevant to your research.

Keep track of your research and use citation tools. It'll make life easier when it comes time to compile your references.

7 Frequently Asked Questions

1. how do i get articles for free.

Free articles can be found through free online academic journals, OA databases, or other databases that include OA journals and articles. These resources allow you to access free papers online so you can conduct your research without getting stuck behind a paywall.

Academics don't receive payment for the articles they contribute to journals. There are often, in fact, publication fees that scholars pay in order to publish. This is one of the funding structures that allows OA journals to provide free content so that you don't have to pay fees or subscription costs to access journal articles.

2. How Do I Find Journal Articles?

Journal articles can be found in databases and institutional repositories that can be accessed at university libraries. However, online research databases that contain OA articles are the best resource for getting free access to journal articles that are available online.

Peer-reviewed journal articles are the best to use for academic research, and there are a number of databases where you can find peer-reviewed OA journal articles. Once you've found a useful article, you can look through the references for the articles the author used to conduct their research, and you can then search online databases for those articles, too.

3. How Do I Find Peer-Reviewed Articles?

Peer-reviewed articles can be found in reputable scholarly peer-reviewed journals. High-quality journals and journal articles can be found online using academic search engines and free research databases. These resources are excellent for finding OA articles, including peer-reviewed articles.

OA articles are articles that can be accessed for free. While some scholarly search engines and databases include articles that aren't peer reviewed, there are also some that provide only peer-reviewed articles, and databases that include non-peer-reviewed articles often have advanced search features that enable you to select "peer review only." The database will return results that are exclusively peer-reviewed content.

4. What Are Research Databases?

A research database is a list of journals, articles, datasets, and/or abstracts that allows you to easily search for scholarly and academic resources and conduct research online. There are databases that are interdisciplinary and cover a variety of topics.

For example, Paperity might be a great resource for a chemist as well as a linguist, and there are databases that are more specific to a certain field. So, while ERIC might be one of the best educational databases available for OA content, it's not going to be one of the best databases for finding research in the field of microbiology.

5. How Do I Find Scholarly Articles for Specific Fields?

There are interdisciplinary research databases that provide articles in a variety of fields, as well as research databases that provide articles that cater to specific disciplines. Additionally, a journal repository or index can be a helpful resource for finding articles in a specific field.

When searching an interdisciplinary database, there are frequently advanced search features that allow you to narrow the search results down so that they are specific to your field. Selecting "psychology" in the advanced search features will return psychology journal articles in your search results. You can also try databases that are specific to your field.

If you're searching for law journal articles, many law reviews are OA. If you don't know of any databases specific to history, visiting a journal repository or index and searching "history academic journals" can return a list of journals specific to history and provide you with a place to begin your research.

6. Are Peer-Reviewed Articles Really More Legitimate?

The short answer is yes, peer-reviewed articles are more legitimate resources for academic research. The peer review process provides legitimacy, as it is a rigorous review of the content of an article that is performed by scholars and academics who are experts in their field of study. The review provides an evaluation of the quality and credibility of the article.

Non-peer-reviewed articles are not subject to a review process and do not undergo the same level of scrutiny. This means that non-peer-reviewed articles are unlikely, or at least not as likely, to meet the same standards that peer-reviewed articles do.

7. Are Free Article Directories Legitimate?

Yes! As with anything, some databases are going to be better for certain requirements than others. But, a scholarly article database being free is not a reason in itself to question its legitimacy.

Free scholarly article databases can provide access to abstracts, scholarly article websites, journal repositories, and high-quality peer-reviewed journal articles. The internet has a lot of information, and it's often challenging to figure out what information is reliable.

Research databases and article directories are great resources to help you conduct your research. Our list of the best research paper websites is sure to provide you with sources that are totally legit.

Get Professional Academic Editing

Hire an expert academic editor , or get a free sample, about the author.

Scribendi's in-house editors work with writers from all over the globe to perfect their writing. They know that no piece of writing is complete without a professional edit, and they love to see a good piece of writing transformed into a great one. Scribendi's in-house editors are unrivaled in both experience and education, having collectively edited millions of words and obtained numerous degrees. They love consuming caffeinated beverages, reading books of various genres, and relaxing in quiet, dimly lit spaces.

Have You Read?

"The Complete Beginner's Guide to Academic Writing"

Related Posts

How to Write a Research Proposal

How to Write a Scientific Paper

How to Write a Thesis or Dissertation

Upload your file(s) so we can calculate your word count, or enter your word count manually.

We will also recommend a service based on the file(s) you upload.

English is not my first language. I need English editing and proofreading so that I sound like a native speaker.

I need to have my journal article, dissertation, or term paper edited and proofread, or I need help with an admissions essay or proposal.

I have a novel, manuscript, play, or ebook. I need editing, copy editing, proofreading, a critique of my work, or a query package.

I need editing and proofreading for my white papers, reports, manuals, press releases, marketing materials, and other business documents.

I need to have my essay, project, assignment, or term paper edited and proofread.

I want to sound professional and to get hired. I have a resume, letter, email, or personal document that I need to have edited and proofread.

Prices include your personal % discount.

Prices include % sales tax ( ).

How To Write A Research Paper

Step-By-Step Tutorial With Examples + FREE Template

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | March 2024

For many students, crafting a strong research paper from scratch can feel like a daunting task – and rightly so! In this post, we’ll unpack what a research paper is, what it needs to do , and how to write one – in three easy steps. 🙂

Overview: Writing A Research Paper

What (exactly) is a research paper.

- How to write a research paper

- Stage 1 : Topic & literature search

- Stage 2 : Structure & outline

- Stage 3 : Iterative writing

- Key takeaways

Let’s start by asking the most important question, “ What is a research paper? ”.

Simply put, a research paper is a scholarly written work where the writer (that’s you!) answers a specific question (this is called a research question ) through evidence-based arguments . Evidence-based is the keyword here. In other words, a research paper is different from an essay or other writing assignments that draw from the writer’s personal opinions or experiences. With a research paper, it’s all about building your arguments based on evidence (we’ll talk more about that evidence a little later).

Now, it’s worth noting that there are many different types of research papers , including analytical papers (the type I just described), argumentative papers, and interpretative papers. Here, we’ll focus on analytical papers , as these are some of the most common – but if you’re keen to learn about other types of research papers, be sure to check out the rest of the blog .

With that basic foundation laid, let’s get down to business and look at how to write a research paper .

Overview: The 3-Stage Process

While there are, of course, many potential approaches you can take to write a research paper, there are typically three stages to the writing process. So, in this tutorial, we’ll present a straightforward three-step process that we use when working with students at Grad Coach.

These three steps are:

- Finding a research topic and reviewing the existing literature

- Developing a provisional structure and outline for your paper, and

- Writing up your initial draft and then refining it iteratively

Let’s dig into each of these.

Need a helping hand?

Step 1: Find a topic and review the literature

As we mentioned earlier, in a research paper, you, as the researcher, will try to answer a question . More specifically, that’s called a research question , and it sets the direction of your entire paper. What’s important to understand though is that you’ll need to answer that research question with the help of high-quality sources – for example, journal articles, government reports, case studies, and so on. We’ll circle back to this in a minute.

The first stage of the research process is deciding on what your research question will be and then reviewing the existing literature (in other words, past studies and papers) to see what they say about that specific research question. In some cases, your professor may provide you with a predetermined research question (or set of questions). However, in many cases, you’ll need to find your own research question within a certain topic area.

Finding a strong research question hinges on identifying a meaningful research gap – in other words, an area that’s lacking in existing research. There’s a lot to unpack here, so if you wanna learn more, check out the plain-language explainer video below.

Once you’ve figured out which question (or questions) you’ll attempt to answer in your research paper, you’ll need to do a deep dive into the existing literature – this is called a “ literature search ”. Again, there are many ways to go about this, but your most likely starting point will be Google Scholar .

If you’re new to Google Scholar, think of it as Google for the academic world. You can start by simply entering a few different keywords that are relevant to your research question and it will then present a host of articles for you to review. What you want to pay close attention to here is the number of citations for each paper – the more citations a paper has, the more credible it is (generally speaking – there are some exceptions, of course).

Ideally, what you’re looking for are well-cited papers that are highly relevant to your topic. That said, keep in mind that citations are a cumulative metric , so older papers will often have more citations than newer papers – just because they’ve been around for longer. So, don’t fixate on this metric in isolation – relevance and recency are also very important.

Beyond Google Scholar, you’ll also definitely want to check out academic databases and aggregators such as Science Direct, PubMed, JStor and so on. These will often overlap with the results that you find in Google Scholar, but they can also reveal some hidden gems – so, be sure to check them out.

Once you’ve worked your way through all the literature, you’ll want to catalogue all this information in some sort of spreadsheet so that you can easily recall who said what, when and within what context. If you’d like, we’ve got a free literature spreadsheet that helps you do exactly that.

Step 2: Develop a structure and outline

With your research question pinned down and your literature digested and catalogued, it’s time to move on to planning your actual research paper .

It might sound obvious, but it’s really important to have some sort of rough outline in place before you start writing your paper. So often, we see students eagerly rushing into the writing phase, only to land up with a disjointed research paper that rambles on in multiple

Now, the secret here is to not get caught up in the fine details . Realistically, all you need at this stage is a bullet-point list that describes (in broad strokes) what you’ll discuss and in what order. It’s also useful to remember that you’re not glued to this outline – in all likelihood, you’ll chop and change some sections once you start writing, and that’s perfectly okay. What’s important is that you have some sort of roadmap in place from the start.

At this stage you might be wondering, “ But how should I structure my research paper? ”. Well, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution here, but in general, a research paper will consist of a few relatively standardised components:

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Methodology

Let’s take a look at each of these.

First up is the introduction section . As the name suggests, the purpose of the introduction is to set the scene for your research paper. There are usually (at least) four ingredients that go into this section – these are the background to the topic, the research problem and resultant research question , and the justification or rationale. If you’re interested, the video below unpacks the introduction section in more detail.

The next section of your research paper will typically be your literature review . Remember all that literature you worked through earlier? Well, this is where you’ll present your interpretation of all that content . You’ll do this by writing about recent trends, developments, and arguments within the literature – but more specifically, those that are relevant to your research question . The literature review can oftentimes seem a little daunting, even to seasoned researchers, so be sure to check out our extensive collection of literature review content here .

With the introduction and lit review out of the way, the next section of your paper is the research methodology . In a nutshell, the methodology section should describe to your reader what you did (beyond just reviewing the existing literature) to answer your research question. For example, what data did you collect, how did you collect that data, how did you analyse that data and so on? For each choice, you’ll also need to justify why you chose to do it that way, and what the strengths and weaknesses of your approach were.

Now, it’s worth mentioning that for some research papers, this aspect of the project may be a lot simpler . For example, you may only need to draw on secondary sources (in other words, existing data sets). In some cases, you may just be asked to draw your conclusions from the literature search itself (in other words, there may be no data analysis at all). But, if you are required to collect and analyse data, you’ll need to pay a lot of attention to the methodology section. The video below provides an example of what the methodology section might look like.

By this stage of your paper, you will have explained what your research question is, what the existing literature has to say about that question, and how you analysed additional data to try to answer your question. So, the natural next step is to present your analysis of that data . This section is usually called the “results” or “analysis” section and this is where you’ll showcase your findings.

Depending on your school’s requirements, you may need to present and interpret the data in one section – or you might split the presentation and the interpretation into two sections. In the latter case, your “results” section will just describe the data, and the “discussion” is where you’ll interpret that data and explicitly link your analysis back to your research question. If you’re not sure which approach to take, check in with your professor or take a look at past papers to see what the norms are for your programme.

Alright – once you’ve presented and discussed your results, it’s time to wrap it up . This usually takes the form of the “ conclusion ” section. In the conclusion, you’ll need to highlight the key takeaways from your study and close the loop by explicitly answering your research question. Again, the exact requirements here will vary depending on your programme (and you may not even need a conclusion section at all) – so be sure to check with your professor if you’re unsure.

Step 3: Write and refine

Finally, it’s time to get writing. All too often though, students hit a brick wall right about here… So, how do you avoid this happening to you?

Well, there’s a lot to be said when it comes to writing a research paper (or any sort of academic piece), but we’ll share three practical tips to help you get started.

First and foremost , it’s essential to approach your writing as an iterative process. In other words, you need to start with a really messy first draft and then polish it over multiple rounds of editing. Don’t waste your time trying to write a perfect research paper in one go. Instead, take the pressure off yourself by adopting an iterative approach.

Secondly , it’s important to always lean towards critical writing , rather than descriptive writing. What does this mean? Well, at the simplest level, descriptive writing focuses on the “ what ”, while critical writing digs into the “ so what ” – in other words, the implications. If you’re not familiar with these two types of writing, don’t worry! You can find a plain-language explanation here.

Last but not least, you’ll need to get your referencing right. Specifically, you’ll need to provide credible, correctly formatted citations for the statements you make. We see students making referencing mistakes all the time and it costs them dearly. The good news is that you can easily avoid this by using a simple reference manager . If you don’t have one, check out our video about Mendeley, an easy (and free) reference management tool that you can start using today.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. To recap, the three steps to writing a high-quality research paper are:

- To choose a research question and review the literature

- To plan your paper structure and draft an outline

- To take an iterative approach to writing, focusing on critical writing and strong referencing

Remember, this is just a b ig-picture overview of the research paper development process and there’s a lot more nuance to unpack. So, be sure to grab a copy of our free research paper template to learn more about how to write a research paper.

You Might Also Like:

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Something went wrong when searching for seed articles. Please try again soon.

No articles were found for that search term.

Author, year The title of the article goes here

LITERATURE REVIEW SOFTWARE FOR BETTER RESEARCH

“This tool really helped me to create good bibtex references for my research papers”

Ali Mohammed-Djafari

Director of Research at LSS-CNRS, France

“Any researcher could use it! The paper recommendations are great for anyone and everyone”

Swansea University, Wales

“As a student just venturing into the world of lit reviews, this is a tool that is outstanding and helping me find deeper results for my work.”

Franklin Jeffers

South Oregon University, USA

“One of the 3 most promising tools that (1) do not solely rely on keywords, (2) does nice visualizations, (3) is easy to use”

Singapore Management University

“Incredibly useful tool to get to know more literature, and to gain insight in existing research”

KU Leuven, Belgium

“Seeing my literature list as a network enhances my thinking process!”

Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium

“I can’t live without you anymore! I also recommend you to my students.”

Professor at The Chinese University of Hong Kong

“This has helped me so much in researching the literature. Currently, I am beginning to investigate new fields and this has helped me hugely”

Aran Warren

Canterbury University, NZ

“It's nice to get a quick overview of related literature. Really easy to use, and it helps getting on top of the often complicated structures of referencing”

Christoph Ludwig

Technische Universität Dresden, Germany

“Litmaps is extremely helpful with my research. It helps me organize each one of my projects and see how they relate to each other, as well as to keep up to date on publications done in my field”

Daniel Fuller

Clarkson University, USA

“Litmaps is a game changer for finding novel literature... it has been invaluable for my productivity.... I also got my PhD student to use it and they also found it invaluable, finding several gaps they missed”

Varun Venkatesh

Austin Health, Australia

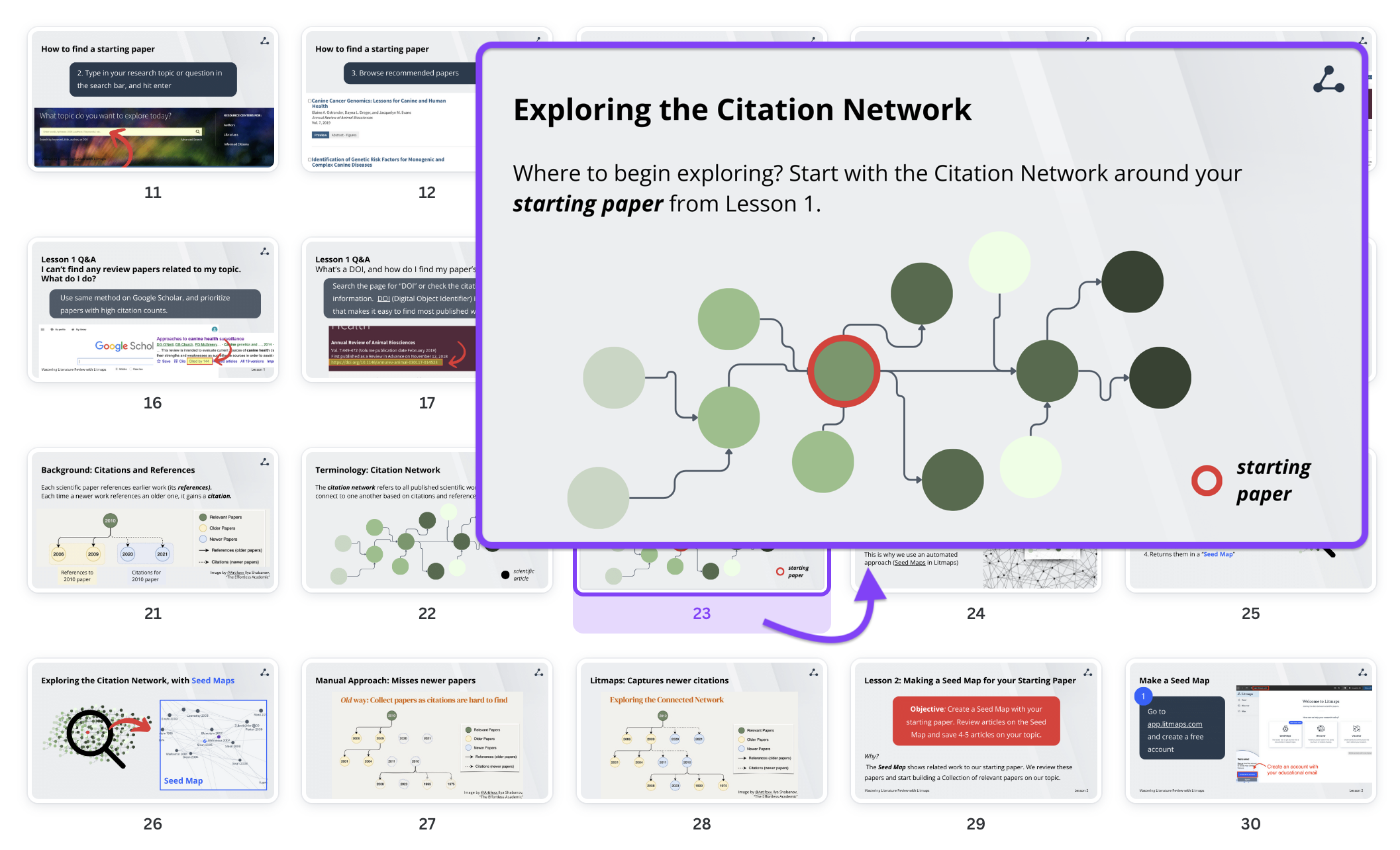

Our Course: Learn and Teach with Litmaps

- Advanced search

- Peer review

Discover relevant research today

Advance your research field in the open

Reach new audiences and maximize your readership

ScienceOpen puts your research in the context of

Publications

For Publishers

ScienceOpen offers content hosting, context building and marketing services for publishers. See our tailored offerings

- For academic publishers to promote journals and interdisciplinary collections

- For open access journals to host journal content in an interactive environment

- For university library publishing to develop new open access paradigms for their scholars

- For scholarly societies to promote content with interactive features

For Institutions

ScienceOpen offers state-of-the-art technology and a range of solutions and services

- For faculties and research groups to promote and share your work

- For research institutes to build up your own branding for OA publications