Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 07 April 2023

Barriers and interventions on the way to empower women through financial inclusion: a 2 decades systematic review (2000–2020)

- Omika Bhalla Saluja ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9831-1947 1 ,

- Priyanka Singh 1 &

- Harit Kumar 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 148 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

6382 Accesses

5 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Development studies

This study aims to reduce ambiguity in theoretical and empirical underpinning by synthesizing various knowledge concepts through a systematic review of barriers and interventions to promote the financial inclusion of women. The surrounding literature is vast, complex, and difficult to comprehend, necessitating frequent reviews. However, due to the sheer size of the literature, such reviews are generally fragmented focusing only on the factors causing the financial exclusion of women while ignoring the interventions that have been discussed all along. Filling up this gap, this study attempts to provide a bird’s-view to systematically connect all the factors as well as mediations found in past studies with the present and future. PRISMA approach has been used to explain various inclusions and exclusions extracted from Scopus & WOS databases with the backward and forward searches of important studies. Collaborative peer review selection with a qualitative synthesis of results is used to explain various barriers and interventions in financial inclusion that affected women’s empowerment in the period 2000–2020. Out of 1740 records identified, 67 studies are found eligible based on systematic screening for detailed investigation. This study has identified patriarchy structures, psychological factors, low income/wages, low financial literacy, low financial accessibility and ethnicity as six prominent barriers and government & corporate programs/policies, microfinance, formal saving accounts & services, cash & asset transfer, self-help groups, and digital inclusion as six leading interventions to summarize the literature and highlight its gaps.

Similar content being viewed by others

Interviews in the social sciences

Eleanor Knott, Aliya Hamid Rao, … Chana Teeger

Participatory action research

Flora Cornish, Nancy Breton, … Darrin Hodgetts

A meta-analysis of projected global food demand and population at risk of hunger for the period 2010–2050

Michiel van Dijk, Tom Morley, … Yashar Saghai

Introduction

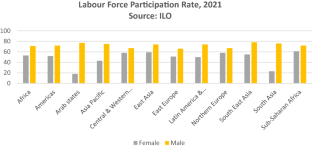

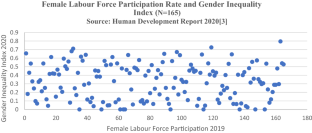

All over the world, women bear an inadequate load of poverty because of social and structural hurdles. A long-dated body of literature (Klasen, 1999 ; Dollar and Gatti, 1999 ; Klasen and Lamanna, 2009 ; Seguino, 2010 ) emphasizes the effect of numerous facets of gender inequality and economic growth. Females are found to be less educated, less paid, less on ownership and able to exercise much less economic control than their male counterparts. This discrimination, especially in education, hampers their financial development, leading to income inequality (Gonzales et al., 2015 ). Consequently, women suffer from lack of health, education, work opportunities and control over their own lives and selections (Kabeer, 1999 )

Nevertheless, we are observing a critical drive to achieve gender equality, with 193 United Nations member countries committing to achieving the sustainable development goal (SDG 5) of ending gender inequality issues by 2030. Realizing that women’s empowerment benefits not only women but also the sustainable development of the community (Vithanagama, 2016 ), numerous banks all over the world, such as Westpac in Australia, ICICI and SBI in India, Natwest in the UK, and UNITAR in Kenya, have developed products and services designed especially for women, keeping in mind their security, accessibility and affordability. To make the most of this, we need more extensive literature exploration to enable conceptually strong evidence-based solutions catalyzing women’s mobility from poverty and exploitation. Considering the vastness of literature, this can only be addressed by a scientific approach to review, which has been followed in the present study. However, due to the sheer size of the related literature, previous reviews (Holloway et al., 2017 , Kalaitzi et al., 2017 , Roy and Patro, 2022 ) are found to be fragmented as their results focused only on the factors causing the financial exclusion of women while ignoring the interventions that have been discussed all along.

Therefore, filling up this gap our review paper aims to scientifically identifying and amalgamating the related studies between 2000 and 2020 with the objective of (a) identifying the nature of major barriers, (b) exploring the most useful mediations/interventions and trends in research on the financial inclusion (FI) of women to enable the community to design thoughtful interventions for them.

The economic empowerment of women was explored in various dimensions at a much greater pace after 2000 (Priya et al., 2021 ). This inspired us to focus on the research work and other initiatives taken in the following 2 decades, defining our study period 2000–2020. Many influential articles have been published in journals dedicated to women and general development, such as World Development Footnote 1 , Feminist Economics Footnote 2 , Journal of Development Economics Footnote 3 and Gender & Development Footnote 4 . However, despite tremendous progress in the global state of FI, the gap in gender has not changed much since 2011, as a 6% difference still exists in access to Bank accounts among men and women in developing countries (Demirguc-Kunt et al., 2022 ), raising the need for considerate customized mediation.

Early studies on financial empowerment of women

Professor Irene Tinker’s work in women studies in the 1960s and 70s is the foundation for research on women development studies. Her work was instrumental in bringing about the first United Nations International conference on Women in 1975, which is also marked as International women’s year. She also founded the International Centre for Research on Women in 1976, which promotes empirical research to advocate evidence-based ways to empower women and promote gender equality.

Research in the 1970s was characterized by pioneer studies that highlighted the role of women in economic development (Boserup, 1970 ; Tinker, 1976 ), while the 1980s captured the role of females in family structures (Acharya and Bennett, 1981 ), the hardships faced by women in agriculture, which was identified as the single most important employment-generating sector for women (Staudt and Jaquette, 1982 ), and the advancement of land rights for women (Agarwal, 1988 ).

In the 1990s, research gathered pace with numerous studies about the persisting gender inequalities (Tinker, 1990 , 1999 ; Sen, 1990 ; Buvinić and Gupta, 1994 ; Mehra, 1997 , Mayoux, 1998 ; Pande, 1999 ) in cooperatives (Sen, 1990 ), financial services and microlevel entrepreneurship (Mehra and Gammage, 1999 ), and discriminations in agriculture and land rights of women to bring about sustainable development and suggest inclusive policies and practices (Mehra, 1995 ). Providing a much need direction and empirical advancement, Kabeer, 1999 proposed the measurement of women’s empowerment with the identification of the ‘resources’ they own, the ‘agency’ or commanding role they have and their ‘achievement’, which can be understood as the outcome in terms of well-being as the basic constructs to be observed. This is one of the most cited articles in the context of studies about the economic empowerment of women. By the end of the decade, the World Bank’s research report presented a cross-country comparison of the impact of gender inequalities on growth and development (Klasen, 1999 ), thus introducing crucial insights into the geographical diversity of the issue.

Thus, the literature around the financial empowerment of women began with recognizing the crucial role of women in the commercial progress at macro level then; it started to realize their critical role at family level and nature of their contribution at social level, which highlighted gender inequalities. Various dimensions in which such discrimination existed were identified giving scope to future researchers to explore various barriers in the way of women development and to develop suitable policy interventions.

Research methodology

Systematic reviews must follow the preset protocol, which is an advance plan of action specifying the methods to be used in the study and is generally accepted as a research design in social science studies. These rules are crucial to avoid researcher bias in data selection and analysis and increase the reliability of reviews (Xiao and Watson, 2019 ).

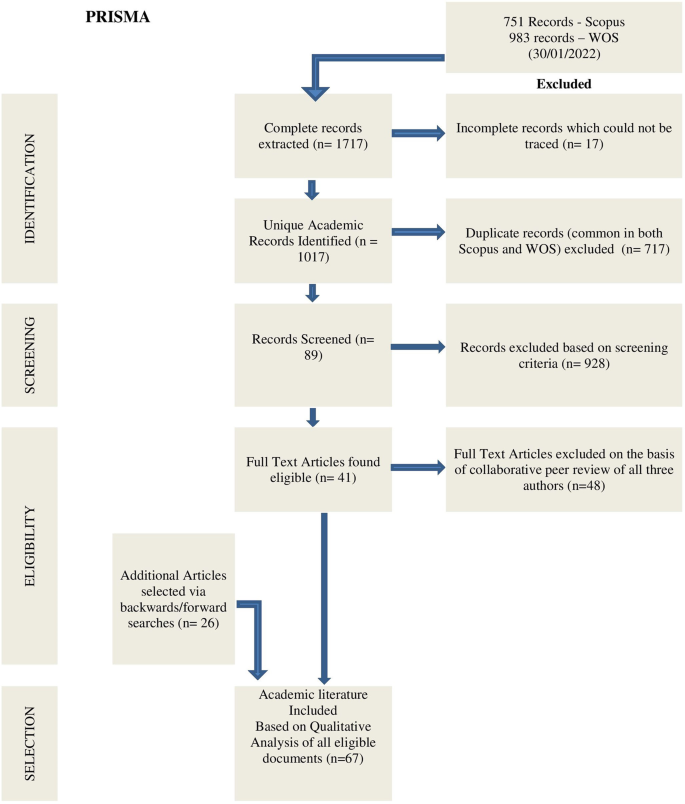

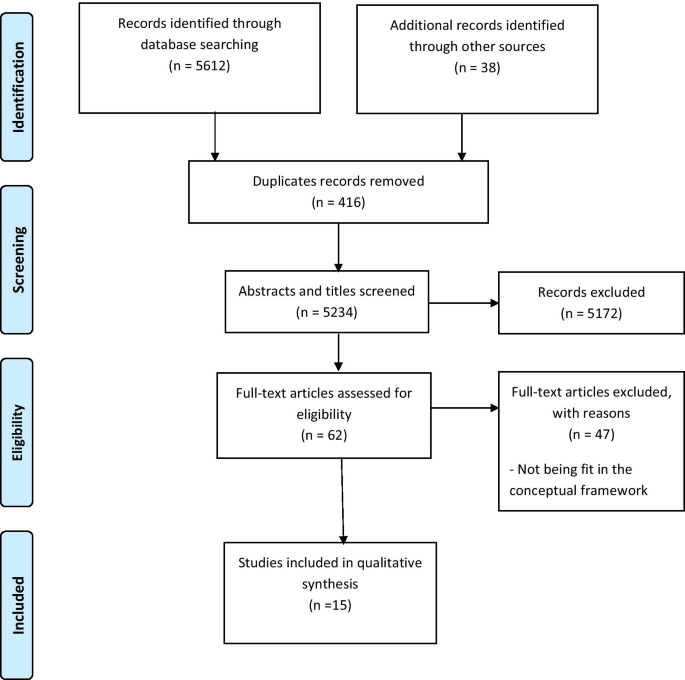

In this section, we have described systematic steps undertaken to extract data using specific channels, keywords, inclusion & exclusion criteria and expert selection explained through the PRISMA framework (Fig. 1 ).

Our initial result of 1734 documents (results as on 30 January 2022) was filtered by including only peer reviewed open access, full text English articles on Financial inclusion and women empowerment, resulting in 67 eligible documents. (author created).

Further, the studies thus extracted have been classified and synthesized qualitatively for deeper insights.

Channel used for literature search

Literature for this review has been found using the two sources suggested by Xio and Watson in 2019. These sources are:

Electronic database —Web of Science (WOS) and Scopus. WOS has the longest indexing coverage from 1900 to the present (Li et al., ( 2010 ) while Scopus has an extensive coverage of good quality academic work (Gavel and Iselid, 2008 ). A literature search using both databases despite the overlapping articles is still recommended to avoid missing out high-impact documents (Vieira and Gomes, 2009 ). Extractions from Scopus and WOS for this study were made on January 30, 22.

Backwards and forward search —Articles cited in important studies (highly cited) were traced to identify the inspiration and key background variables, likewise the articles that cited important studies were explored to determine the direction of the flow of research. (Webster and Watson, 2002 ; Haddaway et al., 2022 ). Also, publications by key authors (highly cited) who contributed to the pool of knowledge were identified to ensure that all their important studies were included.

Concepts from the search statement were extended by synonyms, abbreviations, verb forms and related terms to select keywords (Rowley and Slack, 2004 ), as shown in the Table 1 below:

To capture the essence of the study’s research objectives, a dive was made into the Web of Science and Scopus data extracting 751 and 983 records, respectively, based on identified keywords.

PRISMA approach

Data pulled out were filtered using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses—PRISMA (Fig. 1 ), that explains initial screening, determining parameters for inclusion and exclusion and outlining work limitations (Stovold et al., 2014 ; Selçuk, 2019 ).

Inclusion parameters

Publications from 2000–2020.

Open access articles.

Research areas: “Business management, social science, economics, econometrics, accounting and finance”

Exclusion parameters

Incomplete and non-English language publications.

Conference reviews, books, chapters, book reviews, conference papers, and surveys were excluded.

Articles in press.

Collaborative peer review-based exclusion

Expert selection and evaluation

After the electronic screening of records, a double screening was performed by all three authors, where all 89 studies were reviewed by each author individually. Later, 48 studies were screened out as they were not found to be measuring the population (vulnerable women) or outcomes (barriers and interventions) of interest, and 41 studies were finally selected. Additionally, 26 important and relevant studies, including 8 working papers, were identified through backwards and forward searches while reviewing the studies. The included working papers are listed in the Table 2 for reference. After the screening of the literature, a total of 67 articles were documented individually and classified and amalgamated in tables followed by a qualitative synthesis of these studies.

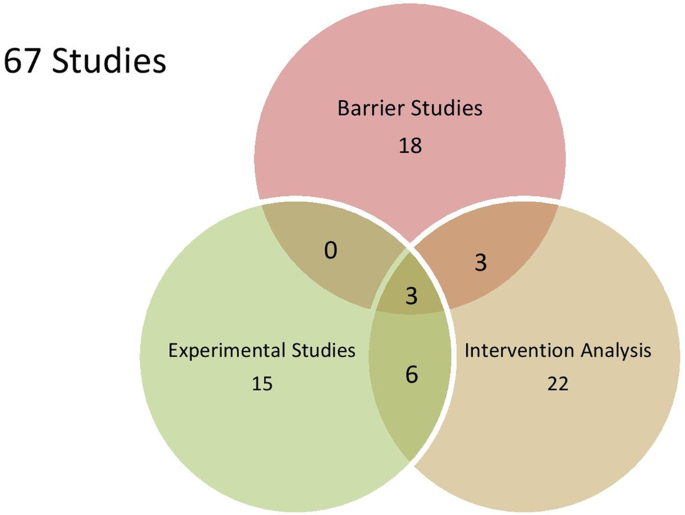

To achieve our research objectives, the selected articles were classified as barrier-related studies, experimental studies and studies evaluating interventions, with a few studies covering more than one dimension (Fig. 2 ).

Venn grouping of the selected studies on the basis of their evaluation of barriers or interventions and the nature of study being experimental or otherwise (author created).

Tabular synthesis

In Table 3 below, we have classified and connected 67 eligible articles based on their contribution to developing different perspectives about barriers and interventions in FI-based women empowerment.

Additionally, twenty-four experimental studies during 2000–2020 are presented in a tabular form (Table 4 ) for review. For the purpose of our study, only the gender-based findings are listed for each study. Owing to the high level of heterogeneity of quantitative data, we could not conduct a meta-analysis; instead, we summarized studies based on their characteristics, factors, mediations and results (Bohren et al., 2015 ).

Qualitative synthesis

The ideas forwarded through the tabular classifications in the studies of FI and WE have been knit to arrive at a thematic discussion about barriers, intervention-based studies and intervention types, which are the three main dimensions of our study.

Barriers to financial empowerment of women

Women have been suppressed and exploited physically, socially, mentally and economically for a long time. Developing countries particularly have a patriarchal set up where women are seen second to men (Nagindrappa and Radhika, 2013 ). While there is a section of society that encourages women empowerment, numerous barriers continue to restrict their advances.

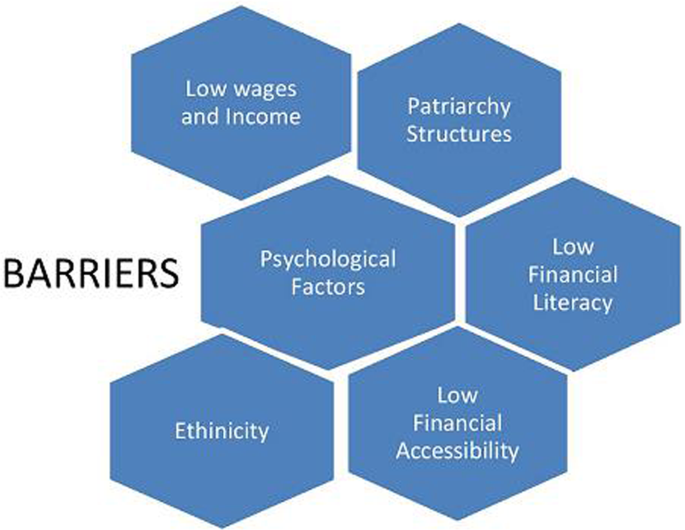

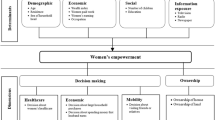

Through our set of identified studies, we have presented below a discussion about various barriers that have been found through the discussion to be interlinked and often cyclical in nature. Figure 3 highlights the scope of our further discussion about the barriers to FI in women.

Six cyclic and interconnected barriers to the FI of women identified through an expert evaluation of selected studies (author created).

Patriarchy structures

Patriarchy is a socio-ideological concept in which men in the family (father, brother, husband, son, etc.) are considered to be superior to women. It is also described as a social arrangement in which men (patriarchs) dominate, oppress and exploit women (Walby, 1989 ).

Delving into the subject of patriarchy, noted author, Naila Kabeer, 2015 pointed to two types of inequities against women. First, gender mediated social class-based violence, rape and other sexual exploitation that women get subject to, and second, domestic violence due to scarcity or poverty and related helplessness of males within the household.

The abuse of women does not stem from scarcity or poverty; even affluent families exploit their daughters by denying them their land and property rights. The Indian government introduced a gender-progressive inheritance law to combat this injustice; despite the reforms, parents continued to deprive their daughters of their rights based on emotions and compensation in the form of higher education and higher dowries (Roy et al., 2015 ). This ill treatment of woman, which starts from her parental abode, continues in her husband’s house, where the ordered unequal power relations developed out of patriarchy further diminish her position. Her production, reproduction and sexuality are controlled by men. This biased treatment of women in the household adversely affects all levels of her social interactions, depriving her of access to resources and opportunities (Manta, 2019 ; Ghosh and Günther, 2018 ) and financial independence (Schaner, 2017 ).

Psychological factors

For obvious reasons, as discussed under the previous heading, many women lose self-confidence and self-esteem and perceive opportunities with fear of failure (Koellinger et al., 2008 ). An experimental study found that females in the lower income group tend to be more risk averse than their male counterparts and think about the negative consequences of not being able to pay back loans. (Manta, 2019 ) Thus, psychological factors must be carefully studied as crucial drivers of the FI of women (Kavita and Suman, 2019 ).

It was found that investment pattern, group experience and age impacted women’s perception about barriers to FI (Lombe et al., 2012 ), and attitude could be explained by personality traits, ability to cope-up, resource utilization, entrepreneurial abilities, organizational control, financial inclusion and economic betterment (Patil and Kokate, 2017 ).

Low income/wages

Although the concepts of income inequality and gender have been discussed separately in the literature, they cannot be compartmentalized, as they keep interacting by the way of inequality in outcomes and opportunities, which are a bye-product of inequalities mainly in education, financial access, social structures and individual perspectives.

With the biasness of patriarchy and her own fallen self-esteem, a woman’s low negotiation and bargaining power leads her to enter into the social contracts where she is able to earn a low level of income and wages compared to men for the same work. This discrimination is popularly referred to as the “glass ceiling” and is experienced by women at all levels of hierarchy. This reminds us of the much-discussed US presidential elections in 2016, where former U.S. Senator and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton was subject to misogynistic attacks indicating to her being too weak to serve the nation’s highest office. (Marie et al., 2017 ). Hence, women being exploited at work in terms of work treatment and low wages are no exception. At lower levels of education and power, gendered wage gaps are even more pronounced (Gonzales Martínez et al., 2020 ) and are found to further contribute to financial exclusion (Ghosh and Vinod, 2017 ) and further impede the economic growth of women.

Low financial literacy

With cyclical interconnections with all other barriers to the financial empowerment of women, financial literacy has been much discussed by researchers. Hung, A. et al, 2009 combined all previous definitions of financial literacy to express it as “knowledge of basic economic and financial concepts, as well as the ability to use that knowledge and other financial skills to manage financial resources effectively for a lifetime of financial well-being.” Successive studies have recognized financial awareness, financial knowledge, financial skills, financial attitude and financial behavior as key factors in determining financial literacy (Kumari and Azam, 2019 )

Financial literacy has been supported as one of the critical factors to bring about FI and has greater importance for increasing economic empowerment among women, especially the rural poor (Gonzales et al., 2015 ; Montanari and Bergh, 2019 ; Kumari and Azam, 2019 ; Kaur and Kapuria, 2020 ), who in the lack of it make wrong choices and become vulnerable to high financial risks (Manta, 2019 ). With a lack of financial knowledge and skills, women cannot access financial services and the benefits of the formal financial system, making them economically dependent on men and confined to the vicious circle of low investments, low income and low profits (Manta, 2019 ). Montanari and Bergh, 2019 found that the participation of women in the earnings and decision-making activities of rural cooperatives was almost nonexistent. It insisted that women’s roles in such institutions were restricted to low-cost or free physical labor, while those who benefited were literate and generally educated people.

Spatial diversity and related factors play an important role in the effective communication of financial literacy. Gendered gaps in education were found to be greatly related to the general variation in educational achievement across countries, signifying a shortage of access to education. (Gonzales et al., 2015 ).

A cross-regional comparison showed high-level gendered discrimination based on education level and economic participation in South Asia. Observations in Asian countries indicate lessening of the gendered employment gap with the rise in gendered education levels, while in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), gender gaps in education have decreased, yet women have not obtained opportunities in employment (Klassen and Lamanna, 2009 ). This result hints at the presence of interwoven barriers that are passed on locally.

Overall, a high level of financial literacy is expected to result in greater economic participation of women, where she has an opportunity to express her thoughts and receive suggestions about investment avenues and updates about new profitable products and services, encouraging her towards group effort and informed financial behavior (Ingale and Paluri, 2020 ), which in turn improves her relative wealth (Doss et al., 2020 ) and empowers her.

Low financial accessibility

Access to bank accounts, savings instruments, and other financial amenities may result in women’s better control of their earnings, personal consumption and commercial expenditure (Bernasek, 2003 ), and lack of it pushes her back to obscurity. This was exemplified in an experimental study in Kenya that found that credit constraint prevented women from starting a business and savings constraint further barred them from sustaining it (Brudevold et al., 2017 ).

While trying to develop within the male dominant society, a woman is subject to biases that pull down her self-confidence hurling her into the loop of less education, low employment and low wages, denying her the benefits of access to formal finance such as credit, deposits, insurance, payments and other risk management services (Demirguc-Kunt et al., 2022 ). Findings in an Africa-based study indicate that access to formal finance is mainly driven by individual characteristics such as education, age, income, residence area, employment status, marital status, household size and degree of trust in financial institutions (Soumare et al., 2016 ). Most of the above factors have been identified as obstacles for the FI of women, thus emphasizing women’s overall lack of opportunity to access finance.

Women’s lack of access to financial products and services may also happen because of the absence of a bank branch in rural areas that are not commercially viable for banking. Marginalized women living in underdeveloped far-flung areas with poor infrastructure and roads find it hard to regularly visit bank branches in other areas (Manta, 2019 ), so they avoid banking altogether. This problem was addressed by Mueller et al. in 2020, who worked to develop a travel time model to indicate market accessibility, which is the summary travel time to the nearest state capital city in hours. Such indicators may help in planning inclusion strategies.

Another major reason for women’s lack of access to finance is the lack of commercial interest of banks in disbursing small credit to poor women with no credit history or collateral. Such lending may lead to the building up of non-performing assets and eventually high losses for banks. Therefore, they avoid giving loans to underprivileged women depriving them of economic opportunities. Moreover, the absence of collateral with women is further enhanced by biased traditional property rights (Manta, 2019 ), which denies her resources to build upon a better future.

Looking at the brighter side, ambitious efforts are being made through pathways such as microfinance (Kemp and Berkovitch, 2020 ) and digital inclusion to pull women out of these never-ending and self-building barriers.

In recent studies, ethnicity has emerged as an important factor to be considered while promoting FI in women. Gonzales Martínez et al. ( 2020 ) conducted a controlled laboratory experiment in Bolivia to evaluate whether credit officers in microfinance institutions rejected loan applications on the basis of the interaction of gender and ethnicity of potential buyers. Although the study supported that women were benefitting from microcredit, it indicated discrimination based on ethnicity, as nonindigenous women had twice the probability of getting loan approved, whereas indigenous women had only 1.5 times the probability of getting loan approved compared to men. This idea was supported by another contemporary study (Kaur and Kapuria, 2020 ), suggesting that households headed by females belonging to socially underprivileged backgrounds had a poorer likelihood of obtaining finance from institutions. This suggests that important insights for FI for women can be derived from ethnic studies.

Experimental studies on women’s financial empowerment

As the researchers identified various variables related to the financial empowerment of women through exploratory and descriptive studies, a number of empirical and experimental studies were undertaken to understand the relationship between them. The three main types of interventions identified during our analysis were as follows:

Economic interventions —Involving cash/asset transfer, free bank accounts, free services, subsidies

Social interventions —Comprising family counseling, life skill training, vocational training, awareness programs

Bundled Economic and Social Interventions

Mostly, field experiments measuring the long-term impact of interventions on women’s financial empowerment were conducted. Overall, economic interventions were found to be highly effective in reducing the economic vulnerability of women (Stark et al., 2018 ; Brudevold et al., 2017 ). However, Ismayilova et al., 2018 and Buehren et al., 2015 ) suggested that bundling up economic, social and psychological interventions could make them more constructive.

Interventions implemented for financial empowerment of women

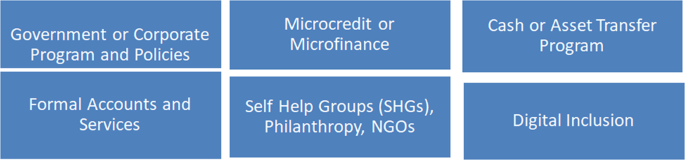

Intervention studies have guided various programs and policies of governments that are essential to support, promote and scale up the literacy, access and growth of financial products and services for women’s empowerment. Realizing the fact that women’s empowerment benefits not only women but also the sustainable development of the community (Vithanagama, 2016 ), numerous banks all over the world, such as Westpac in Australia, ICICI and SBI in India, Natwest in the UK, and UNITAR in Kenya, have developed products and services designed especially for women, keeping in mind their security, accessibility and affordability. Figure 4 defines the scope of our further discussion about six successful interventions in the way of FI of women.

Six most important interventions in empowering women through FI identified through an expert evaluation of selected studies (author created).

Government/corporates programs and policies

The insights developed from the conclusive studies provided governments and public and private enterprises around the world to design suitable inclusive programs, schemes and policies to address the gender gap in finance. Interventions such as government-to-people transfers and the inclusion of post office financial services were evaluated by researchers to comprehend their success or failure in bringing about fairness for women. Swamy ( 2014 ) evaluated the Indian government’s inclusive plans, policies and programs by observing changes in income level, food security, living standards, production levels and asset creation to find that the FI initiatives had a much higher impact on women than on men. These results were cited in many successive studies and laid the groundwork for more intensive inclusive efforts in India.

While acknowledging the imperative need for women’s empowerment for nation building, governments and related organizations all over the world launched ambitious programs to support women. Strategies of the Green Morocco Plan (GMP) were explored by Montanari and Bergh ( 2019 ) to conclude towards the persisting miserable circumstances of women despite planned efforts.

Similar to the actions taken by the states, many private sector companies design schemes, products and programs to promote gender equality for the benefit of their women staff. A Turkish study (Gülsoy and Ustaba, 2019 ) investigated diversity management strategies of companies and found that company leadership played an important role in bringing about equality programs in the workplace. However, they also pointed to the profiteering motive of corporations, which could be served by associating with image building activities, higher productivity and innovation capability, which could result from greater employee satisfaction.

However, some studies claim that many such initiatives had failed because they did not fully anticipate the importance and influence of social institutions such as age, gender, ethnicity, literacy, race, background and religion towards building an enabling environment for inclusion (Gonzales Martínez et al., 2020 ; Kaur and Kapuria, 2020 ).

Microcredit/microfinance

Microfinance helps to bring about the financial independence of poor or exploited women by enabling them to participate in economic activities, improving their status in households and society and reinforcing their power to make decisions (Zhang and Posso, 2017 ; Lall et al., 2017 ). A strong correlation was found between the level of outreach of microfinance institutions and women’s empowerment (Laha and Kuri, 2014 ).

Zhang and Posso ( 2017 ) used case studies to support the constructive role of microfinance to reduce gender inequality. This idea was strengthened by the empirical diary data-based study (Elu et al., 2019 ) in Mozambique, Sub-Saharan Africa, which revealed that being a woman had a positive treatment effect on procuring microcredit. A longitudinal panel study (Khandker and Samad, 2014 ) comparing the effects of microcredit programs in Bangladesh showed that a 10% increase in borrowing by women lowered extreme poverty by 5% and increased the willingness to work of women by 0.46%.

The usefulness of microfinance, microcredit, and microenterprises to promote the empowerment of women has been widely studied (Karlan et al., 2007 ; Swamy, 2014 ; Laha and Kuri, 2014 ; Zhang and Posso, 2017 ), along with the impact of bundling them up with vocational trainings, education or counseling (Kim et al., 2007 ; Buehren et al., 2015 ; Karlan et al., 2007 ). It has been found that both economic and social empowerment programs together were effective in reducing IPV (Kim et al., 2007 ). One such intervention affirms that lifeskills and livelihood training along with microfinance resulted in the likelihood of higher earnings and consumption along with a reduction in teen pregnancy and early marriage (Buehren et al., 2015 ). Likewise, it was found that health knowledge along with microcredit could help in reducing health risks (Karlan et al., 2007 ).

On the other hand, the success of microfinance policy based on outreach was challenged with an argument that institutions and their policies had engaged in a residual rather than the relational understanding of poverty (Johnson, 2013 ). Similarly, it was also questioned by Gonzales et al. in 2020 by highlighting the regressive attitude and biasness of credit officers against indigenous women.

Formal accounts/services

Formal account ownership and its use have been established as an important indicator of FI, and with the support of several research experiments, it has been adopted as an important policy intervention in many countries. Worldwide, 55% of males have a formal account at a financial institution, whereas only 47% of women own or co-own such an account with a gloomier picture in developing countries where women are 28% less likely to have an account at a formal financial institution. (Demirguc-Kunt et al., 2022 ).

Bank accounts result in savings that lead to wealth creation, which is an identified determinant of FI. A study in Kenya found that women made use of savings account far more than men. It observed that there was a 45% increase in savings on business investments among women when commitment-saving bank accounts were opened along with a high fee on withdrawal (Dupas and Robinsion, 2013 ). However, in their successive study (Dupas et al., 2014 ), where instead of a compulsive intervention, the mediation was only to facilitate account opening, it was found that men saved more than women and were more frequent in making transactions.

Hence, the mere opening of bank accounts in the names of women will not ensure their inclusion in the financial mainstream, and their usage of the same over the long run is crucial development. An experimental study found that 22% of such mediated accounts were active in the short run, and only 7% were used in the third year. Many women claim that they use the formal account of someone else in their family so they do not need an account in their own name. In many cases, husbands hold access to the ATM card of their wife, hinting towards the family structures that deprive women of a sense of ownership, making her dependent on other family members in financial matters. (Schaner, 2017 ; Demirguc-Kunt et al., 2022 ).

On the brighter side, it was found that with the sense of ownership of wealth, women tend to appreciate themselves by spending on their personal needs, elevating their sense of self-worth. There was a 40% increase in women’s personal expenditure (Dupas and Robinsion, 2013 ) and an increase in education and health after the account opening (Prina, 2015 ). Additionally, the ATM cards issued along with bank accounts were found to be quite popular among married couples, as transactions increased up to 62% in the short run and 68% in the long run. It was found to enable wives to participate in joint financial decisions along with their husbands (Schaner, 2017 ). These results reflect the positive impact of free account opening and subsidized or free financial services on inclusion but also emphasize the need to ensure that the benefits reach out to the targeted vulnerable women and have long-term effects.

Cash/asset transfer program

CTs benefit women through financial well-being, economic security and emotional well-being, leading to a reduction in intimate partner violence and significant improvement in women’s status and relationships in the family. (Ismayilova et al., 2018 ; Buller et al., 2018 )

Studies have supported adding cognitive and emotive features such as training, counseling and coaching with economic strategies in policy interventions to empower women (Ismayilova et al., 2018 ; Brudevold et al., 2017 ). When CT intervention was compared with the one coupled with life skill training, it was found that sole cash transfers were more useful in increasing the income of women in the short run only, whereas the likelihood of employment could be increased with life skill training and CT bundled together (Brudevold et al., 2017 ). An interesting study to find the real beneficiaries of CT in the long run found that benefits were largely retained by women, as they had less pressure to share their income with their relatives on the pretext that their earning options were limited (Squires, 2018 ).

The impact of productive asset transfer (livestock) in the name of women was explored in an experimental setting in Bangladesh. It revealed that although women’s asset ownership increased significantly, the real beneficiaries were men instead of women (“fly paper effect”), male sole ownership in agriculture and land increased significantly after the intervention (Roy et al., 2015 ). This reaffirms the earlier made point about the way dowry benefits are reaped by the male members.

The usefulness of CT or asset transfer cannot be denied in the short run, where lack of cash or assets averts women from starting a business, but their limitation to save prevents them from sustaining the benefits in the long run (Brudevold et al., 2017 ).

Self-help groups (SHG), philanthropy, NGOs

SHGs are informal groups of rural women formed to socially and economically support each other with a sense of belongingness and responsibility among themselves. These groups foster FI along with the social empowerment of women. Members join the SHG mainly to obtain financial support to meet basic needs, especially in the case of emergency (Nagaraj and Sundaram, 2017 ).

Most SHG members are young in age, are less educated, have less income and lack any kind of previous experience in handling money. After their SHG experience, women have been found to be managing cash (Kabeer, 2011 ; Maclean, 2012 ; Ramachandar and Pelto, 2009 ), although some studies have found that even after SHG training, there was no impact on asset formation or income of participants (Deininger and Liu, 2013 ), women remained unsure and pressurized about their financial decisions, especially in the presence of a community member (Maclean, 2012 ; Ramachandar and Pelto, 2009 ).

It was found that when the members become old in the group, they start realizing their social responsibilities, which transforms their social participation and builds up their confidence in making decisions (Mehta et al., 2011 ), enabling them to fight against exploitation at the family or societal level.

Many philanthropists and NGOs have dedicated themselves to the cause of women’s empowerment. The BOMA project in Kenya, which works to achieve the UN sustainable development goals of poverty reduction, reducing gender inequality and mitigating the effects of climate change, has been instrumental in increasing income and savings (Tiwari et al., 2019 ). In 2019, Hendriks studied the logic and strategy of the functioning of one such philanthropic Bill & Melinda Gates foundation that aims to reduce the gender gap through FI, while in 2020, Kemp and Berkovitch worked to study feminist NGOs in Israel.

Digital inclusion

Gender was identified as a key variable in consumer readiness in adopting mobile payment services and strategizing market segmentation (Humbani and Wiese, 2018 ). Digital financial services have been discussed in papers as one of the most effective FI models (Arnold and Gammage, 2019 , Natile, 2019 ), promising greater privacy, confidentiality and control of women over their finances (Duflo, 2012 ). An influential African study by Efobi et al. in 2018 found a strong positive relationship between progressions in information technology through mobile & internet penetration and the participation of women in the economy.

With the advent of mobile banking, many women who cannot reach out to financial institutions have been linked to financial services and are more likely to save than men, even with limited amounts (Ouma et al., 2017 ), gaining greater flexibility to spend on household expenditures and child welfare measures (Duflo, 2012 ). In 2016, Suri and Jack found that Kenyan mobile money system M-PESA was able to lift 194,000 households, which was 2% of the total households, out of poverty, with a significant positive impact in female households driven by higher savings and better employment of women. Acknowledging its phenomenal reach, the drawbacks and efficiencies of mobile banking were discussed further to promote FI (Humbani and Wiese, 2018 ; Arnold and Gammage, 2019 ). Prospects of digitizing G2P payments were evaluated (Klapper and Singer, 2017 ) to find that with the backing of government, there could be a dramatic reduction in costs, higher efficiencies, transparency and greater acceptance of technology.

Deliberating imperfections, on the one hand, complex financial products and services are being launched every other day; on the other hand, almost 80% of women in low-income economies still earn their wages in cash (Klapper and Dutt, 2015 ). Inherent inequalities in financial access (Klapper and Dutt, 2015 ), innumeracy, illiteracy and unfamiliarity with technology (Tiwari et al., 2019 ) are barriers to women’s digital FI. Reiterating the above idea, the exploration of inclusionary arrangements found the exploitation of the M-PESA program to identify market opportunities causing its failure to adopt the redistributive measures necessary for the benefit of society (Natile, 2019 ). This suggests that there is a need for a very well-planned, systematic digital intervention with higher transparency, sensitivity and awareness.

Our systematic study seeks to explore its research objectives through three dimensions viz. barriers, intervention types and intervention/experimental studies (Fig. 2 ). The results obtained with regards to each dimension have been further discussed to present the contribution of our work.

Out of 67 related studies 24 studies provided us insights about the barriers in the way to financial Inclusion of women. A tabular synthesis of these studies resulted in the identification of six barriers, which were further qualitatively synthesized to find that they were interlinked and often cyclical in nature. We found that the study conducted for understanding one barrier led the way to explore other barrier. The long-term ill treatment of women due to patriarchy structures induce low self-esteem and other psychological barriers, which in turn reduce their negotiation power and more often than not they have to settle for low income and wages coupled with low literacy levels than their male counterparts. Low finances, economic power and low literacy directly affect their decision-making, leadership and opportunities. With fewer opportunities to grow, females get lesser access to finance and the women who have been underprivileged on account of their ethnicity face greater challenges in accessing finance their development. Lack of financial strength and literacy keeps pushing women into the patriarchy structures and hence the viscous cycle of disempowering women continues.

The results obtained from the tabular synthesis of 34 intervention studies, identified Government/Corporates programs and policies, Microcredit/Microfinance, Formal accounts/services, Cash/asset transfer program, Self-Help Groups (SHG), Philanthropy, NGOs and Digital Inclusion as the main interventions. These interventions have been individually documented to get insights about the related studies. The qualitative results suggest that there is a significant role of public and social institutions, related experiences, economic nature of intervention and technical advancement in financial services in fostering financial empowerment of women.

Also, we have presented a tabular synthesis of 24 intervention or experimental studies, which give an insight about the kind of intervention, the key findings and the research methodology that has been adopted in previous studies (Table 4 ). The findings from intervention studies suggest that economic interventions alone or bundled with social interventions were useful in financially empowering women.

Previous studies such as Holloway et al. ( 2017 ) and Kalaitzi et al. ( 2017 ) have used thematic mapping and traditional review methods to approach similar problem. Holloway et al. ( 2017 ) studied the impact of various saving, credit, payments and insurance products on women empowerment and found that there are numerous demand and supply-side barriers, some of which could be overcome by product design features. The study suggested that a greater degree of control and privacy surrounding women’s income and expenditure decision could boost their inclusion in the financial system. Our study results supports this finding especially while planning financial inclusion of women through digital ways where transparency, sensitivity and awareness must be considered as important variables.

Kalaitzi et al. ( 2017 ) identified 26 barriers to women leadership in Healthcare, Academia and Business, some of which were common while some were found to be starkly different across sectors. A systematic review by Roy and Patro ( 2022) synthesized evidence from 73 studies to find out that demand side factors were the main cause of gender-based exclusion. Unlike these studies, we have not only identified the different types of barriers, but also have attempted to understand the nature of these barriers, which has led to physical, social, mental, economic exploitation and overall suppression of women since a very long time. The focus of previous studies was only on the factors and the importance of the FI of women, giving us the opportunity to discuss the subject at a comprehensive level by including related interventions. Also, our findings about the experimental studies have not been presented in former studies making our contribution significant in women studies.

Thus, filling up the gaps, we have discussed the nature of six main barriers, summarized 24 key experimental studies and have clearly identified six major interventions that have been applied in the first 2 decades of the twenty-first century to provide a bird’s-view to systematically connect the factors as well as mediations found in past studies with the present and future.

However, as mentioned earlier in the result section of this paper, the presence of heterogeneity of the quantitative studies prevented us from conducting a meta-analysis, which we have tried to compensate with a rigorous synthesis of results from various studies. Sincere efforts have been made to include all the major contributors to the research topic, but due to the vastness of the subject and the limitation of our research design, some insightful studies may have been omitted from the discussion. Nevertheless, we believe that the current work covers inputs from many imminent studies, such as Kabeer ( 2011 ), Kabeer and Sweetman ( 2015 ), Beck et al. ( 2007 ), Brudevold et al. ( 2017 ), Swamy ( 2014 ), Efobi et al. ( 2018 ), Klapper and Dutt, ( 2015 ), and Dupas and Robinsion ( 2013 ) is able to provide the readers with a comprehensive, yet quick overview of the literature and its gaps while contributing to the development of useful interventions to achieve the sustainability goal of gender equality by 2030.

Practical implications

Considering the vastness of the subject and the need for urgent attention as the fifth sustainability goal, a quick understanding to formulate useful policies, programs and other interventions is much needed. Therefore, the findings of our study can provide useful insights to policy makers.

The barriers to financial Inclusion of women have been found to be inter-related and cyclical. This implies that a constant endeavor to eradicate even one such hurdle will have a multifold effect and will be useful in removing others. On the flip side, if attention is not paid to remove even one of these hurdles, they will keep occurring and obstructing the way of women’s development. Therefore, long-term policy interventions with continuous monitoring of efforts are required to bring about inclusive financial growth of women.

We have found through our exploration of intervention studies (Table 3 ) that though Government-to-people transfers (G2P), such as pensions, conditional cash transfers, financial literacy programs, microfinance, other socioeconomic transfers and products & services of public facility institutions such as post-offices, have resulted in the growth of savings and thereby higher entrepreneurship among women, but the related experiences of poor women determine their likelihood of connecting with the system in the long run. Hence, merely designing the intervention is not enough, and careful monitoring of such interventions must be done to achieve the objectives.

We have also found that SHGs, NGOs and other local communities enable women to become a part of the value chain and the familiarity and trust of vulnerable women in such organizations gives them a comparative advantage over other formal institutions. Therefore, as these formal or informal setups help women to get past the psychological hurdles, they must be included in all programs devised for including women in the financial system.

Moreover, we have found digital inclusion to be the most promising intervention with the widest range and prospects to connect with left-behind poor women. This calls for a sensitive customized approach keeping in mind the convenience of vulnerable and less educated women in adapting to the digital ways.

Furthermore, through our exploration of experimental studies (Table 4 ) we have found that economic interventions are more useful than social interventions in promoting entrepreneurship, savings, consumption and general betterment of the lifestyle of women. However, the most effective programs are those in which both economic and social components are incorporated. This insight can be utilized towards designing valuable mediations to support entrepreneurship among women, keeping in view that such intervention should not just be on papers, but must actually reach to the beneficiary and be utilized towards the identified cause only.

Future scope for research

The 67 studies discussed in this work have exposed many gaps in the related literature. As we have found that all the barriers are inter-related and cyclical, there is a need to break the cycle. Our findings can help future researchers to develop deeper insights about each of the highlighted barrier. A few future areas for research have been identified as:

Meaningful and important insights can be derived from ethnic studies to measure the impact of cultural institutions such as women’s dress codes and their expected public behavior on the level of their economic participation.

Exploration of behavioral irrationality of rural women towards financial products and services.

Biasness at the workplace in terms of income, authority and leadership should be explored further to devise suitable interventions.

The perception, attitude, and behavior of women towards finance have been evaluated in many studies, but not much has been discussed to understand the supply-side psychological hurdles at the individual level in disbursal of finance.

Likewise, our results suggest and discuss the evaluation of most effective interventions, which can help researchers to understand the way these mediations have developed so far and the way in which they can be improvised. Some future areas, which may be explored in theory may be:

The usefulness of online education to promote financial literacy and awareness in the remote corners of countries and across countries.

The lack of discussion about insurance products to mitigate risk and encourage investments among women can be addressed.

There is a need to discuss security, transparency and awareness in digital financial services along with thoughtfully designing simpler digital interfaces, tools and devices customized for women.

Moreover, as the problem of the FI of women has evidently been discussed primarily in developing nations, there is a need for exploration studies about poor or indigenous women in developed countries.

Thus, offering a deeper insight to the subject of Women empowerment through Financial Inclusion, we have identified six prominent barriers to FI of women: patriarchy structures, psychological factors, low income/wages, low financial literacy, low financial accessibility and ethnicity and have uniquely found that these barriers are interconnected with cyclical impact, resulting in redistribution effects that further widen the gaps between the privileged and the underprivileged, which must be considered while designing interventions in future.

Similarly, we have recognized six main interventions that have been introduced thus far: government and corporate programs/policies, microfinance, formal saving accounts/services, cash or asset transfer, self-help groups and digital inclusion and have presented various methods and findings of related experimental researches to provide direction for future inquiry. The consequences, appreciation and criticism of various interventions have been documented in the results and discussion to provide useful vision for future policy or theoretic implementation. Overall, this study has exclusively presented a summary of the barriers and interventions, which have been inquired into during 2000–2020 thereby contributing to achieving sustainable development goal (SDG 5) of ending gender inequality issues by 2030.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information file.

Deininger & Liu ( 2013 ) in World Development, 43, 149–163, Ghosh & Vinod ( 2017 ) in World Development, 92, 60–81, Swamy ( 2014 ) in World Development, 56, 1–15.

Klasen & Lamanna ( 2009 ) in Feminist economics, 15(3), 91–132

Prina ( 2015 ) in Journal of development economics, 115, 16–31, Roy et al. ( 2015 ) in Journal of Development Economics, 117, 1–19.

Seguino ( 2010 ) in Gender & Development, 18(2), 179–199, Kabeer & Sweetman ( 2015 ) in Gender & Development, 23(2), 185–188.

Acharya M, Bennett L (1981) The rural women of Nepal: an aggregate analysis and summary of 8 village studies. In: The Status of Women in Nepal, Vol. II, Part 9. Center for Economic Development and Administration (CEDA), Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu

Adoho F, Chakravarty S, Korkoyah, DT, Lundberg MKA, Tasneem A (2014) The Impact of an Adolescent Girls Employment Program: The Epag Project in Liberia. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 6832, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2420245

Agarwal B (1988) Who sows? Who reaps? Women and land rights in India. J Peasant Stud 15(4):531–581

Article Google Scholar

Alzúa ML, Cruces G, Lopez C (2016) Long-run effects of youth training programs: experimental evidence from Argentina. Econ Inq 54(4):1839–1859. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecin.12348

Arnold J, Gammage S (2019) Gender and financial inclusion: the critical role for holistic programming. Dev Pract 29(8):965–973. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2019.1651251

Bandiera O, Buehren N, Burgess R, Goldstein M, Gulesci S, Rasul I, & Sulaiman M (2015) Women’s economic empowerment in action:Evidence from a randomized control trial in Africa. Employment Working Paper no. 187, International Labour Office Geneva

Beck T, Demirgüç-Kunt A, Levine R (2007) Finance, inequality and the poor. J Econ Growth 12(1):27–49

Article MATH Google Scholar

Bernasek A (2003) Banking on social change: Grameen Bank lending to women. Int J Polit Cult Soc 16(3):369–385

Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, Lutsiv O, Makh SK, Souza JP, Gülmezoglu M (2015) The mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities globally: a mixed-methods systematic review. PLoS Med 12(6):e1001847

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Boserup E (1970) Women’s role in economic development. St. Martins, New York

Google Scholar

Brudevold-Newman AP, Honorati M, Jakiela P, Ozier, OW (2017) A Firm of One’s Own: Experimental Evidence on Credit Constraints and Occupational Choice. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 7977, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2923530

Buehren N, Goldstein M, Gulesci S, Sulaiman M, Yam V (2015) Evaluation of layering microfinance on an adolescent development program for girls in Tanzania. BRAC Institute of Governance and Development, Mohakhali, Dhaka. https://bigd.bracu.ac.bd/publications/evaluation-of-layering-microfinance-on-an-adolescent-development-program-for-girlsin-tanzania/

Buller AM, Peterman A, Ranganathan M, Bleile A, Hidrobo M, Heise L (2018) A mixed-method review of cash transfers and intimate partner violence in lowand middle-income countries. World Bank Res Obs 33(2):218–258. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lky002

Buvinić M, Gupta GR (1994) Targeting poor woman-headed households and woman-maintained families in developing countries: views on a policy dilemma. Population Council

Chakravarty S, Lundberg MK, Nikolov P, Zenker J (2016) The role of training programs for youth employment in Nepal: Impact evaluationreport on the employment fund. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, (7656)

Cho Y, Kalomba D, Mobarak AM, Orozco V (2013) Malawi-differences in the effects of vocational training: constraints on women and drop-out behavior. World Bank Group. United States of America

Deininger K, Liu Y (2013) Economic and social impacts of an innovative self-help group model in India. World Dev 43:149–163

Demirguc-Kunt A, Klapper L, Singer D, Ansar S (2022) The Global Findex Database 2021: financial inclusion, digital payments, and resilience in the age of COVID-19. World Bank. © World Bank, Washington, DC, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/37578

Diaz JJ, Rosas D (2016) Impact evaluation of the job youth training program Projoven (No. IDB-WP-693). IDB Working Paper Series

Dollar D, Gatti R (1999) Gender inequality, income, and growth: are good times good for women? (Vol. 1). Development Research Group, The World Bank, Washington, DC

Doss C, Swaminathan H, Deere CD, Suchitra JY, Oduro AD, Anglade B (2020) Women, assets, and formal savings: a comparative analysis of ecuador, ghana and india. Dev Policy Rev 38(2):180–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12424

Duflo E (2012) Women empowerment and economic development. J Econ Lit 50:1051–1079

Dupas P, Robinson J (2013) Savings constraints and microenterprise development: Evidence from a field experiment in Kenya. Am Econ J Appl Econ 5(1):163–192

Dupas P, Green S, Keats A, Robinson J (2014) Challenges in banking the rural poor: Evidence from Kenya’s western province. In: African successes, volume III: modernization and development. University of Chicago Press. pp. 63–101

Efobi UR, Tanankem BV, Asongu SA (2018) Female economic participation with information and communication technology advancement: Evidence from Sub‐Saharan Africa. S Afr J Econ 86(2):231–246

Elu J, Price GN, Williams M (2019) Gender and microcredit in Sub-Saharan Africa: The case of Mozambican small holder households. Enterprise Development & Microfinance 30(2):117–128

Field E, Jayachandran S, Pande R, Rigol N (2016) Friendship at work: can peer effects catalyze female entrepreneurship? Am Econ J Econ Policy 8(2):125–53. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20140215

Gavel Y, Iselid L (2008) Web of Science and Scopus: a journal title overlap study. Online information review

Ghosh S, Vinod D (2017) What constrains financial inclusion for women? evidence from indian micro data. World Dev 92:60–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.11.011

Ghosh S, Günther MK (2018) Financial inclusion through public works program: Does gender-based violence make a difference? Gend Issue 35(3):254–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12147-017-9202-0

Gonzales Martínez R, Aguilera-Lizarazu G, Rojas-Hosse A, Aranda Blanco P (2020) The interaction effect of gender and ethnicity in loan approval: a bayesian estimation with data from a laboratory field experiment. Rev Dev Econ 24(3):726–749. https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.12607

Gonzales MC, Jain-Chandra MS, Kochhar MK, Newiak MM, Zeinullayev MT (2015) Catalyst for change: empowering women and tackling income inequality. International Monetary Fund

Gülsoy T, Ustabaş A (2019) Corporate sustainability initiatives in gender equality: organizational practices fostering inclusiveness at work in an emerging-market context. Int J Innov Technol Manag 16(04):1940005

Haddaway NR, Grainger MJ, Gray CT (2022) Citation chaser: a tool for transparent and efficient forward and backwards citation chasing in systematic searching. Res Synth Method 13(4):533–545

Hendriks S (2019) The role of financial inclusion in driving womenas economic empowerment Dev Pract 29(8):1029–1038. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2019.1660308

Holloway K, Niazi Z, Rouse R (2017) Women’s economic empowerment through financial inclusion: a review of existing evidence and remaining knowledge gaps. Innovations for poverty action

Honorati M (2015) The impact of private sector internship and training on urban youth in Kenya. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, (7404)

Humbani M, Wiese M (2018) A cashless society for all: determining consumers’ readiness to adopt mobile payment services. J Afr Bus 19(3):409–429

Hung AA, Parker AM, Yoong JK (2009) Defining and measuring financial literacy. RAND Working paper series no. 708

Ibarrarán P, Kluve J, Ripani L, Rosas Shady D (2019) Experimental evidence on the long-term effects of a youth training program. ILR Rev 72(1):185–222

Ingale KK, Paluri RA (2020) Financial literacy and financial behaviour: a bibliometric analysis. Review of Behavioral Finance 14(1):130–154

Ismayilova L, Karimli L, Gaveras E, Tô-Camier A, Sanson J, Chaffin J, Nanema R (2018) An integrated approach to increasing women’s empowerment status and reducing domestic violence: results of a cluster-randomized controlled trial in a West African country. Psychol Violence 8(4):448

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Johnson S (2013) From microfinance to inclusive financial markets: the challenge of social regulation. Oxf Dev Stud 41(SUPPL 1):S35–S52. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600818.2012.734799

Kabeer N (1999) Resources, agency, achievements: reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Dev Change 30(3):435–464

Kabeer N (2011) Contextualising the Economic Pathways of Women’s Empowerment: Findings from a Multi-Country Research Programme, Pathways Policy Paper, Brighton: Pathways of Women’s Empowerment, IDS

Kabeer N (2015) Gender, poverty, and inequality: a brief history of feminist contributions in the field of international development. Gender & Development 23(2):189–205

Kabeer N, Sweetman C (2015) Introduction: gender and inequalities. Gend Dev 23(2):185–188

Kalaitzi S, Czabanowska K, Fowler-Davis S, Brand H (2017) Women leadership barriers in healthcare, academia and business. Equal Divers Incl Int J 36(5):457–474

Karlan DS (2007) Social connections and group banking. Econ J 117:F52–F84

Kaur S, Kapuria C (2020) Determinants of financial inclusion in rural India: does gender matter? Int J Soc Econ 47(6):747–767. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-07-2019-0439

Kavita, Suman (2019) Determinants of financial inclusion in India: a literature review. Indian J Financ 13(11):53–61. https://doi.org/10.17010/ijf/2019/v13i11/148417

Kemp A, Berkovitch N (2020) Uneasy passages between neoliberalism and feminism: social inclusion and financialization in Israel’s empowerment microfinance. Gender Work Organ 27(4):507–526. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12400

Khandker SR, Samad HA (2014) Dynamic Effects of Microcredit in Bangladesh. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 6821, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2417519

Kim JC, Watts CH, Hargreaves JR, Ndhlovu LX, Phetla G, Morison LA, Pronyk P (2007) Understanding the impact of a microfinance-based intervention on women’s empowerment and the reduction of intimate partner violence in South Africa. Am J Public Health 97(10):1794–1802

Klapper L, Singer D (2017) The opportunities and challenges of digitizing government-to-person payments. World Bank Res Obs 32(2):211–226

Klapper L, Dutt P (2015) Digital financial solutions to advance women’s economic participation. Report prepared by the World Bank Group for the Turkish G20 Presidency

Klasen S (1999) Does gender inequality reduce growth and development: evidence from cross-country regressions (English). Policy research report on gender and development working paper series; no. 7. World Bank Group, Washington, DC

Klasen S, Lamanna F (2009) The impact of gender inequality in education and employment on economic growth: new evidence for a panel of countries. Fem Econ 15(3):91–132

Koellinger P, Minniti M, Schade C (2008) Seeing the World with Different Eyes: Gender Differences in Perceptions and the Propensity to Start a Business (March 2008). Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper No. 2008-035/3, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1115354 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1115354

Kumari DAT, Ferdous Azam SM (2019) The mediating effect of financial inclusion on financial literacy and women’s economic empowerment: a study among rural poor women in Sri Lanka. Int J Sci Technol Res 8(12):719–729

Laha A, Kuri PK (2014) Measuring the impact of microfinance on women empowerment: A cross country analysis with special reference to india. Int J Public Adm 37(7):397–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2013.858354

Lall P, Shaw SA, Saifi R, Sherman SG, Azmi NN, Pillai V,…, Wickersham JA (2017) Acceptability of a microfinance‐based empowerment intervention for transgender and cisgender women sex workers in Greater Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. J Int AIDS Soc 20(1):21723

Li J, Burnham JF, Lemley T, Britton RM (2010) Citation analysis: Comparison of web of science®, scopus™, SciFinder®, and google scholar. J Electron Resour Med Libr 7(3):196–217

Lombe M, Newransky C, Kayser K, Raj PM (2012) Exploring barriers to inclusion of widowed and abandoned women through microcredit self-help groups: The case of rural south india. J Sociol Soc Welfare 39(2):143–162

Maclean K (2012) Banking on women’s labour: responsibility, risk and control in village banking in Bolivia. J Int Dev 24:S100–S111

Maitra P, Mani S (2017) Learning and earning: evidence from a randomized evaluation in India. Labour Econ 45:116–130

Manta A (2019) Financial inclusion and gender barriers for rural women. Int J Manag 10(5):61–72. https://doi.org/10.34218/IJM.10.5.2019.006

Marie AC-B, Christina AS, Tracy H, Michelle AJ (2017) Women in leadership and the bewildering glass ceiling. Am J Health-Syst Pharm 74(5 Mar):312–324. https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp160930

Mayoux L (1998) Research Round-Up women’s empowerment and micro-finance programmes: strategies for increasing impact. Dev Pract 8(2):235–241

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Mehra R (1995) Women, land and sustainable development. International Center for Research on Women, Washington, DC, pp. 1–48

Mehra R (1997) Women, empowerment, and economic development. The Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci 554(1):136–149

Mehra R, Gammage S (1999) Trends, countertrends, and gaps in women’s employment. World Dev 27(3):533–550

Mehta SK, Mishra DHG, Singh A (2011) Role of self help groups in socio-economic change of vulnerable poor of Jammu region. International Conference on Economics and Finance Research. IPEDR 4(Feb):519–523

Montanari B, Bergh SI (2019) A gendered analysis of the income generating activities under the Green Morocco Plan: who profits? Hum Ecol 47(3):409–417

Mueller V, Schmidt E, Kirkleeng D (2020) Structural change and women’s employment potential in Myanmar. Int Reg Sci Rev 43(5):450–476

Nagaraj B, Sundaram N (2017) Effectiveness of self-help groups towards the empowerment of women in vellore district, tamil nadu. Man India 97(2):843–855

Nagindrappa M, Radhika MK (2013) Women exploitation in Indian modern society. Int J Sci Res Publ 3(2):1–11

Natile S (2019) Regulating exclusions? gender, development and the limits of inclusionary financial platforms. Int J Law Context 15(4):461–478. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744552319000417

Ouma SA, Odongo TM, Were M (2017) Mobile financial services and financial inclusion: Is it a boon for savings mobilization? Rev Dev Financ 7(1):29–35

Pande R (1999) Structural Violence and Women’s Health–Work in the Beedi Industry in India. In: Violence and Health, Proceedings of WHO Global Symposium. WHO, pp. 192–205

Patil S, Kokate K (2017) Identifying factors governing attitude of rural women towards self-help groups using principal component analysis. J Rural Stud 55:157–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.08.003

Prina S (2015) Banking the poor via savings accounts: evidence from a field experiment. J Dev Econ 115:16–31

Priya P, Venkatesh A, Shukla A (2021) Two decades of theorising and measuring women’s empowerment: literature review and future research agenda. Women’s Stud Int Forum 87(Jul):102495. Pergamon

Ramachandar L, Pelto PJ (2009) Self-help groups in Bellary: microfinance and women’s empowerment. J Fam Welf 55(2):1–16

Rowley J, Slack F (2004) Conducting a literature review. Management research news

Roy P, Patro B (2022) Financial inclusion of women and gender gap in access to finance: a systematic literature review. Vision 26(3):282–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/09722629221104205

Roy S, Ara J, Das N, Quisumbing AR (2015) Flypaper effects” in transfers targeted to women: evidence from BRAC’s “Targeting the Ultra Poor” program in Bangladesh. J Dev Econ 117:1–19

Schaner S (2017) The cost of convenience? Transaction costs, bargaining power, and savings account use in Kenya. J Hum Resour 52(4):919–945

Seguino S (2010) The global economic crisis, its gender and ethnic implications, and policy responses. Gend Dev 18(2):179–199

Selçuk AA (2019) A guide for systematic reviews: PRISMA. Turk Arch Otorhinolaryngol 57(1):57

Sen A (1990) Gender and Cooperative Conflicts. In: Tinker I (eds) Persistent inequalities. Oxford University Press, New York

Soumare I, Tchana Tchana F, Kengne TM (2016) Analysis of the determinants of financial inclusion in Central and West Africa. Transnatl Corp Rev 8(4):231–249

Squires M (2018) Kinship taxation as an impediment to growth: experimental evidence from Kenyan microenterprises. Working paper. VSE, University of British Columbia

Stark L, Seff I, Assezenew A, Eoomkham J, Falb K, Ssewamala FM (2018) Effects of a social empowerment intervention on economic vulnerability for adolescent refugee girls in Ethiopia. J Adolesc Health 62(1):S15–S20

Staudt KA, Jaquette JS (1982) Women and development. Women Polit 2(4):1–6

Stovold E, Beecher D, Foxlee R, Noel-Storr A (2014) Study flow diagrams in Cochrane systematic review updates: an adapted PRISMA flow diagram. Syst Rev 3(1):1–5

Suri T, Jack W (2016) The long-run poverty and gender impacts of mobile money. Science 354(6317):1288–1292

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Swamy V (2014) Financial inclusion, gender dimension, and economic impact on poor households. World Dev 56:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.10.019

Tinker I (1976) The adverse impact of development on women. Women and World Development . pp. 22–34

Tinker I (1990) Persistent inequalities. Women and world development

Tinker I, Summerfield G (1999) Women’s rights to house and land: China, Laos, Vietnam. Boulder, Lynne Rienner Publishers, Colorado. ISBN 9781555878177

Tiwari J, Schaub E, Sultana N (2019) Barriers to “last mile” financial inclusion: cases from northern Kenya. Dev Pract 29(8):988–1000

Valdivia M (2015) Business training plus for female entrepreneurship? Short and medium-term experimental evidence from Peru. J Dev Econ 113:33–51

Vieira E, Gomes J (2009) A comparison of scopus and web of science for a typical university. Scientometrics 81(2):587–600

Vithanagama R (2016) Women’s economic empowerment: A literature review. Horizon Printing (Pvt.) Ltd., Pannipitiya, Sri Lanka

Walby S (1989) Theorising patriarchy. Sociology 23(2):213–234

Webster J, Watson RT (2022) Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: writing a literature review. MIS Q 26(2):xiii–xxiii. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4132319

Xiao Y, Watson M (2019) Guidance on conducting a systematic literature review. J plan Educ Res 39(1):93–112

Zhang Q, Posso A (2017) Microfinance and gender inequality: cross-country evidence. Appl Econ Lett 24(20):1494–1498. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2017.1287851

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Pranveer Singh Institute of Technology, Kanpur, India

Omika Bhalla Saluja, Priyanka Singh & Harit Kumar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Omika Bhalla Saluja .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Our study is designed to provide an objective, honest, and unbiased review. This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Saluja, O.B., Singh, P. & Kumar, H. Barriers and interventions on the way to empower women through financial inclusion: a 2 decades systematic review (2000–2020). Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10 , 148 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01640-y

Download citation

Received : 26 August 2022

Accepted : 23 March 2023

Published : 07 April 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01640-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Financial well-being of women self-help group members: a qualitative study.

- Barun Srivastava

- Vinay Kandpal

- Arvind Kumar Jain

Environment, Development and Sustainability (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Open access

- Published: 20 December 2021

Women empowerment in reproductive health: a systematic review of measurement properties

- Maryam Vizheh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8281-3405 1 , 2 ,

- Salut Muhidin ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7780-8580 2 ,

- Zahra Behboodi Moghadam ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4708-3590 1 &

- Armin Zareiyan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6983-0569 3

BMC Women's Health volume 21 , Article number: 424 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

8616 Accesses

6 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

Introduction

There is a considerable dearth of official metrics for women empowerment, which is pivotal to observe universal progress towards Sustainable Development Goals 5, targeting "achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.” This study aimed to introduce, critically appraise, and summarize the measurement properties of women empowerment scales in sexual and reproductive health.

A comprehensive systematic literature search through several international electronic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Embase, ProQuest, and Science Direct was performed on September 2020, without a time limit. All studies aimed to develop and validate a measurement of women empowerment in sexual and reproductive health were included. The quality assessment was performed through a rating scale addressing the six criteria, including: a priori explicit theoretical framework, evaluating content validity, internal consistency, and factor analysis to assess structural validity.

Of 5234 identified studies, fifteen were included. The majority of the studies were conducted in the United States. All studies but one used a standardized measure. Total items of each scale ranged from 8 to 23. The most common domains investigated were decision-making, freedom of coercion, and communication with the partner. Four studies did not use any conceptual framework. The individual agency followed by immediate relational agency were the main focus of included studies. Of the included studies, seven applied either literature review, expert panels, or empirical methods to develop the item pool. Cronbach's alpha coefficient reported in nine studies ranged from α = 0.56 to 0.87. Most of the studies but three lack reporting test–retest reliability ranging r = 0.69–0.87. Nine studies proved content validity. Six criteria were applied to scoring the scales, by which nine of fifteen articles were rated as medium quality, two rated as poor quality, and four rated as high quality.

Most scales assessed various types of validity and Internal consistency for the reliability. Applying a theoretical framework, more rigorous validation of scales, and assessing the various dimensions of women empowerment in diverse contexts and different levels, namely structural agency, are needed to develop effective and representing scales.

Peer Review reports

Recognition and measurement of women empowerment are critical for global development and human rights [ 1 ]. This was accentuated as the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 5), which targets to "achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls” [ 1 ].