- Math for Kids

- Parenting Resources

- ELA for Kids

- Teaching Resources

How to Teach Number Formation in 5 Easy Steps

13 Best Resources for Math Videos for Kids: Math Made Fun

How to Teach Skip Counting to Kids in 9 Easy Steps

10 Best Math Intervention Strategies for Struggling Students

How to Teach Division to Kids in 11 Easy Steps

How to Cope With Test Anxiety in 12 Easy Ways

Developmental Milestones for 4 Year Olds: The Ultimate Guide

Simple & Stress-Free After School Schedule for Kids of All Ages

When Do Kids Start Preschool: Age & Readiness Skills

Kindergarten Readiness Checklist: A Guide for Parents

How to Teach Letter Formtaion to Kids in 9 Easy Steps

15 Best Literacy Activities for Preschoolers in 2024

12 Best Poems About Teachers Who Change Lives

6 Effective Ways to Improve Writing Skills

40 Four Letter Words That Start With A

60 Fun Animal Facts for Kids

12 Best Behavior Management Techniques for the Classroom

13 Best Online Teaching Tips for Teachers

How to Teach Kids to Write in 9 Easy Steps

13 Challenges for Teachers and How to Address Them

What is Creative Play for Kids: Its Importance & Activities

What Is Creative Play?

5 types of creative play, 4 reasons why creative play is important, age-appropriate play for children, 7 ways to encourage creative play, 20 creative play activities for kids.

A child’s development benefits from creative play because it fosters creativity, innovation, and self-expression. Children are encouraged to use various imaginative materials to explore their inner selves, try out new ideas and concepts, and execute their problem-solving skills .

SplashLearn: Most Comprehensive Learning Program for PreK-5

SplashLearn inspires lifelong curiosity with its game-based PreK-5 learning program loved by over 40 million children. With over 4,000 fun games and activities, it’s the perfect balance of learning and play for your little one.

Creative play nurtures a child’s development and early education. Children are encouraged to use various imaginative materials to explore their inner selves, try out new ideas and concepts, and execute their problem-solving skills. Through artistic, imaginative, musical, construction and dramatic play, children tend to develop crucial abilities like communication, empathy , and decision-making.

“The creation of something new is not accomplished by the intellect but by the play instinct acting from inner necessity. The creative mind plays with the objects it loves.” – Carl Jung.

It lets them spread their wings and their imagination run wild, giving a holistic approach to learning and helping them prepare for future challenges while having fun in the process.

Creative play definition suggests that it is an imaginative activity where individuals engage in open-ended play to explore and express their creativity, problem-solving skills, and artistic abilities without strict rules or predefined outcomes. This kind of play encourages children to experiment with new concepts, objects, and ideas since it places more emphasis on the process than the outcome.

This is further supported by an article titled “ How play helps children’s development ” highlights that play is a natural and enjoyable way for children to stay active, healthy, and happy. Through freely chosen play, children can experience healthy development, both physically and mentally, and learn life skills. Providing children with various unstructured play opportunities like drawing , painting, playing with friends, and building blocks from birth until their teenage years is crucial to ensure optimal development.

1. Artistic Play

Children who are engaged in artistic play use a variety of creative mediums, including painting, sculpture, and drawing. This way, they can express their creativity by exploring various textures, hues, and materials. It develops their fine motor skills and improves hand-eye coordination. A few more artistic play activities would be finger painting, watercolour painting, coloured pencil or marker drawings, and clay modelling.

2. Imaginative Play

Children engage in imaginative play when they make up and act out various tales, characters, and scenarios. It helps kids think critically and imaginatively, which aids in the development of their problem-solving and critical-thinking skills. For example, playing dress-up, inventing stories, and playing with action figures or dolls.

3. Musical Play

Children that engage in musical play experiment with diverse sounds and music using a variety of musical instruments or even just their voices. Children benefit from this kind of play by improving their coordination, sense of rhythm, and language abilities. The arts of singing, playing the piano or guitar, and dancing are examples of creative play.

4. Construction Play

Children build and make things out of different materials, including blocks, Legos, or construction sets. The growth of children’s analytical, problem-solving, and creative skills is supported by this type of play. Construction play includes activities like making elaborate drawings out of building kits or building skyscrapers or other structures out of blocks.

5. Dramatic Play

Children act out various roles and settings in this, which are often based on true events or myths. Playing in this way helps kids develop their empathy, social skills , and linguistic skills. Dramatic play includes pretending to be someone else, such as a doctor or engineer, or staging a play.

The beginning of learning starts with multiple forms, and it is critical to understand how it dramatic play helps in a child’s growth and how it might support their success. Let’s explore the it in more detail.

Children benefit a lot from imaginative play because it helps them develop several skills important for their physical and mental growth.

Also, an article published by Science Direct emphasizes that “Play is one of the important components of a child’s life, and it is one of the major activities that promote children’s imagination and creativity.”

The following are the most benefits of creative plays:

- Enhances Imagination and Creativity: Children can use their imaginations to broaden their thinking through creative play , which can eventually lead to the invention of novel and ground-breaking notions. For example, drawing fictional animals, creative landscapes, or moulding clay sculptures. It will help them express what they feel or think about.

- Improves Problem-Solving Abilities: It helps kids develop problem-solving and critical thinking skills.

- Fosters Emotional Development: It helps children develop emotionally and depend on their freedom to explore and express their inner worlds via imaginative play in a supportive and safe environment.

- Improves Social Skills: Children learn vital interpersonal skills, including communication, cooperation, and teamwork, by playing freely with others.

Now that we have a solid understanding of the benefits – let’s explore the kinds of activities most suited to children as per their age.

Age-appropriate play simply means selecting games that are right for a child’s age and stage of growth. For babies, it could be tummy time and soft toys while toddlers might like simple puzzles and playing with dolls or toy cars. Preschoolers will enjoy playdough and games like hide-and-seek. Older kids will like board games or outdoor sports . Based on their developmental needs, the list of play activities that are appropriate for kids of various ages is provided below.

1. Toddlers (1-3 years)

Toddlers learn and grow through fun activities like running , jumping, climbing, and throwing. It helps them move better, enhance their gross motor skills, improve coordination, and build strength. Equally, playing with dolls and toy cars sparks the imagination as well as creativity and lets them make friends by playing together. It’s all about having fun and learning at the same time!

2. Preschoolers (3-5 years)

Preschoolers , who belong to the age bracket of 3-5 years, possess an unwavering curiosity about the world around them and demonstrate remarkable imaginative prowess. One effective way of nurturing their creativity and attention to detail is by engaging them in activities such as painting, drawing, and constructing with blocks, which can all serve as valuable conduits for expressing artistic flair. Additionally, engaging in dressing up and outdoor play can stimulate their senses and facilitate their exploration of the world.

3. School-Age Children (6-12 Years)

School-age children, who typically fall within the range of 6-12 years, it is evident that they have amassed a considerable repertoire of cognitive and social skills, which can be channelled into various creative activities. These activities may include filmmaking, video game playing, and athletics. All of these can refine their mental, emotional, social, and collaborative aptitudes.

Playing with your children in a way that fits your their age is super important because it helps them grow and learn better. Age-appropriate creative play fosters imagination, social skills, and cognitive powers. It also helps in making friends and thinking aptitudes.

You can also help your child be more creative and learn new things while having fun. Here are seven easy ways you can also encourage creative play:

Encouraging playful and creative learning is fundamental to supporting a child’s imagination, intelligence, and creativity and can be achieved through various techniques. As a parent or teacher, you can explore different avenues to stimulate your child’s artistic side and promote imaginative play.

- Provide open-ended toys: To encourage your child’s creativity, provide toys such as building blocks, art tools, and playdough that may be utilized in various ways.

- Allow unstructured playtime: Allow your child unstructured playtime where they can explore and create without being directed or told what to do.

- Support exploration: Allow your child to explore the world around them by taking them on nature walks or to museums.

- Show interest: To foster creativity and deepen your bond with your child, ask them questions about what they’re working on.

- Limit screen time: Because too much screen time can limit creativity, encourage your youngster to engage in other forms of play.

- Foster a positive environment: Create a safe and positive environment where your child can express themselves without fear of being judged.

- Allow mistakes: Assist your child in learning from their mistakes and encourage them to try again.

Encouraging your children gives them an important tool for growth and self-expression. These easy suggestions will help promote your child’s creativity and start them on the way to a bright and imaginative future. Take a close look at a few activities you can do with your little ones.

Signe Juhl Møller conducted an experimental study that lasted four months, focusing on preschool children’s play with creative construction and social-fantasy toys. The study found that toys, imagination, and setting all played significant roles in shaping children’s playtime activities. Thus, parents who encourage their children to partake in these activities bestow upon them a valuable tool for self-growth and expression.

“We are never more fully alive, more completely ourselves, or more deeply engrossed in anything than when we are playing.” – Charles Schaefer, American Psychologist.

- Fabricate an art project utilizing recycled materials such as egg cartons, toilet paper rolls, and cereal boxes.

- Assemble a fort or playhouse utilizing blankets, pillows, and chairs.

- Implore the use of dress-up attire and emulate various characters or scenarios.

- Create a board game with paper, markers, and game pieces from scratch.

- Indulge in a scavenger hunt either indoors or outdoors.

- Put on a puppet show featuring sock puppets or paper bag puppets.

- Host a dance party featuring your child’s preferred music.

- Create homemade playdough and sculpt various shapes and figures.

- Cultivate a garden or container garden and observe the plant’s growth.

- Establish a sensory bin with rice, beans, water, and diverse toys or objects.

- Savour a tea party with dolls or plush animals.

- Engage in magnetism and devise designs on a magnetic board or fridge.

- Erect a tower or structure using blocks, Legos, or alternative materials.

- Participate in games such as Simon Says or Red Light, Green Light.

- Plan a cooking or baking activity and concoct a simple recipe together.

- Embark on a nature walk and gather various items, such as pine cones, rocks, and leaves.

- Create an automobile or spaceship out of a cardboard box, and commence a makeshift journey.

- On a hot day, partake in a water balloon or cannon battle.

- Blow bubbles and measure how large the bubbles your child can create become.

- Undertake a science experiment employing household items such as vinegar, baking soda, oil, and water.

Other than providing enjoyment, these various creative-play activities elicit imagination, creativity, and learning. Thus, prepare yourself to relish in the merriment of this experience with your child and observe their intellectual and emotional growth through the conduit of playtime.

Creative play for kids up a world of unlimited possibilities for children, allowing them to let their imaginations run wild as they learn important life lessons at the same time. These help children develop problem-solving skills, enhance communication skills, and gain confidence in their unique qualities. Parents and teachers must encourage and facilitate a creative and playful learning environment in their children’s lives through art projects, imaginary play, or by building and constructing. Understand what your children need and help them by making learning fun and enjoyable. In no time, you will see your child thrive beyond your imagination.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Can technology be incorporated into creative play.

Yes, technology can complement creative play when used mindfully, such as using interactive apps or digital tools that encourage artistic expression or collaborative storytelling . However, moderation is essential to maintain a healthy balance with real-world experiences.

Why is creative play so crucial for kids?

It allows kids to build cognitive, emotional, and social skills, as well as helps to spark their imaginations and boosts their language skills. Kids learn to think critically in playful ways while building strong cultural understanding.

How can adults motivate kids to play imaginatively?

Parents can encourage kids to play imaginatively at home by playing or drawing together, reading inspiring storybooks, setting up themed playdates, praising innovative ideas and limiting screen time.

12 Best Activities for Kinesthetic Learners

15 best speech therapy activities for toddlers.

15 Best STEM Activities for Preschoolers

Most Popular

15 Best Report Card Comments Samples

117 Best Riddles for Kids (With Answers)

40 best good vibes quotes to brighten your day, recent posts.

10 Best Online Homeschool Programs

Math & ELA | PreK To Grade 5

Kids see fun., you see real learning outcomes..

Watch your kids fall in love with math & reading through our scientifically designed curriculum.

Parents, try for free Teachers, use for free

- Games for Kids

- Worksheets for Kids

- Math Worksheets

- ELA Worksheets

- Math Vocabulary

- Number Games

- Addition Games

- Subtraction Games

- Multiplication Games

- Division Games

- Addition Worksheets

- Subtraction Worksheets

- Multiplication Worksheets

- Division Worksheets

- Times Tables Worksheets

- Reading Games

- Writing Games

- Phonics Games

- Sight Words Games

- Letter Tracing Games

- Reading Worksheets

- Writing Worksheets

- Phonics Worksheets

- Sight Words Worksheets

- Letter Tracing Worksheets

- Prime Number

- Order of Operations

- Long multiplication

- Place value

- Parallelogram

- SplashLearn Success Stories

- SplashLearn Apps

- [email protected]

© Copyright - SplashLearn

Make study-time fun with 14,000+ games & activities, 450+ lesson plans, and more—free forever.

Parents, Try for Free Teachers, Use for Free

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

The Importance of Play: On Finding Joy in your Writing Practice

How to approach your work with open hands, not closed fists.

This article originally appeared in Issue #62, Winter 2017 issue of Creative Nonfiction .

On the last morning of a writers’ retreat I went to a year ago, there was a tiny bell lying on the seat of every chair in the spacious conference center. The weekend was unlike any gathering of writers I’d ever been to: for two days, we attendees had listened, enthralled, to one heresy after another. “Find a hobby that isn’t writing,” one speaker said. “Take walks. Do yoga. Don’t be literary. Be a human being.” Another went further. “It doesn’t take that much time to get writing done,” she said, and a gasp rippled through the audience. Here were writers who took their art seriously, but not themselves—at least, not all the time.

I was charmed to find the little trinket on my seat. What was it for? While the auditorium began to fill, people traded them, pocketed them, bounced them from hand to hand.

One of the workshop leaders took the microphone. He asked us to take our bells, hold them as tightly as we could, and give them a shake. Nothing happened, although several faces turned red with exertion.

“Now take your bell,” he said, “hold it loosely in your hand, and shake it.”

Lovely tinkling music filled the giant room up to its vaulted ceiling.

“That’s how you need to approach writing,” he told us—not with clenched fists, but with open hands.

Relaxed. Playful. Open to possibility.

I returned home from the weekend, set the bell on my desk, and told myself the next hour or two was just for fun. Then I started to write—with results that surprised me. I began to wonder if other writers knew something I didn’t. Could writing be as enjoyable at the outset as at the conclusion? Could it be—dare I say it?—something close to play?

I interviewed four of my favorite writers to find out, and, although they didn’t all use (or even like) the word play , some clear themes began to emerge. Themes like surprise, laughter, and a willingness to let go of self-consciousness and convention. These writers have discovered ways to bring joy into their work, so perhaps it’s no surprise that their writing is a delight to read.

Brenda Miller

One of the workshop leaders at the retreat was Brenda Miller. As she walked us through the steps of writing short, powerful pieces, like her much-anthologized apologia “Swerve” and the sensory-rich “What I Could Eat,” she couldn’t stop smiling. On the last day of the conference, I asked her about her generative writing group, which meets every week to do a series of unusual exercises: first, five minutes of subject-verb-object sentences; then, ten minutes of linking sentences; and finally, one long, continuous run-on sentence for twenty minutes. I was puzzled by so much prescription.

“It’s an interesting paradox,” she said.

Sometimes, the more constraints we give ourselves, the more fun we can have. Think about the rules of a sport or a game: while a free-for-all may sound like fun, we often prefer to have rules and guidelines, and to see how much creativity and mastery we can accomplish within those guidelines. For these particular exercises (which were taught to me by the artist and writer Nancy Canyon), the rules give your intellectual mind something to concentrate on, and then your subconscious mind can come out to play. The time limit quiets the inner censor and forces you to keep writing whatever comes out.

Miller said she also plays in her writing practice by trying pieces as “hermit crab” essays:

In a hermit crab piece, you are adopting already existing forms to tell your story, such as a recipe, a how-to article, etc. I’ve written pieces in the forms of rejection notes, field guides, a table of figures, and how-to pieces. I end up having so much fun developing and playing with the voices of these forms that the writing barely seems like work. In the rejection note piece, titled, “We Regret to Inform You,” I begin by cataloging all the rejections one receives from grade school on, so it starts on a lighthearted note and gets progressively more serious as the chronology goes along, including my experiences with two miscarriages in my early twenties.

Miller has talked about seasons in her writing life—writing in solitude, writing in community, and, most recently, writing in collaboration:

I’ve been doing two different collaborations over the last year: one with my colleague and friend Lee Gulyas and one with my friend Julie Marie Wade. With Lee, we’ve been trading photographs and writing to the images, sometimes together and sometimes individually. You never know what the image will trigger, how our two perspectives will either mesh or diverge.

With Julie, we’ve written many different kinds of essays, usually with one of us starting on a specific topic and lobbing the essay back to the other. In this way, the essay builds bit by bit, shifting directions, always surprising us. Sometimes, it feels like a conversation with each section referring directly to something that came before (such as the essay “Toys” in CNF #60); sometimes, it feels more like parallel play.

I asked if she had always approached writing with this attitude of play.

I can say that after writing for more than thirty years, and teaching for almost twenty, I had to find some new ways to approach the writing process, or I would have stopped writing altogether. As a creative nonfiction writer, it can be easy to feel like you’ve used up your material, so the emphasis becomes finding new perspectives and forms. And yes, this approach makes me very happy to write. I get that thrill of writing something new and unexpected almost every time I come out to play.

Brian Doyle

I first met Brian Doyle at a writers’ workshop fifteen years ago and have been a fan ever since. He had a handout that suggested writers think sideways: What does grass mean? How does winter smell? In “Playfulnessness: A Note,” Doyle argues that the essay is “the most playful of forms, liable to hilarity and free association and startlement.” I recently asked him if he thinks he brings those qualities to his own writing.

Hmm—I do think it’s true, and immediately think of my sister saying I am congenitally wonder-addled because I got spectacles at age seven and have never recovered from that wash of wonder. I suppose I am also sort of addicted to the salt and swing and song of the American language, which is a bruised dusty lewd brave vibrant language, and trammeling it carefully seems disrespectful to me, as long as I am clear. I set out with an idea and try to hammer sentences that have loose ends; does that make sense? I never know where a story or an essay or a proem is going to end up, or even go, quite. . . . I just start, and I have in mind that I want to write like people talk and think, in loose-limbed, free, piercing, entertaining ways, and things go from there—sometimes utterly to the dogs.

I had to ask: what does it mean to hammer sentences that have loose ends?

I am trying to stay open to surprise, to spin, to swerve, to deepen—I want to start and then see what happens. I suspect that if you know exactly what you want to say, or exactly how a piece should end, then you have put yourself in a polite jail cell. I have the utmost respect for op-eds and editorials and reports and journalism, but I also love and am much more deeply moved by pieces that are open to surprise. An example for me is a long essay called “The Meteorites,” which started out simply as a list of all the weird summer jobs I’d had, and morphed into a piece about being a counselor at a summer day camp, and finally into a piece very much about the spangle and spatter of light and love.

Language isn’t the only thing Doyle doesn’t “trammel carefully.” He also plays with form, and I asked him about his proems —the word he uses to describe his box-shaped pieces that are part poem, part prose, part prayer.

With the proems, I want to get to some place between prose and poems, because while poems at their best are the form closest to music and swing and rhythm and cadence, at their worst, they are artsy-fartsy selfish elusive self-absorbed muddles; can you make a thing that’s alert to music but also clear as a bell, in unadorned conversational lines? And as regarding forms, there are so many: the story that’s all one voice; a paragraph in which two stories are being told alternately, as happens in my novel Mink River; the essay that is clearly wildly hyperbolic but also totally true because you waved the hyperbole flag, somehow. . .

Doyle has advised new writers to “type fast and tell a story with your fingers.”

Newer writers very often sit down with expectations and plans and programs and outlines and assumptions as to form, and I think all those things are little jail cells. You shut off so much possible when you insist on what must be. And so much poor writing is just news and memory and explanation and persuasion and report and data and airy opinion; whereas stories are bigger deeper wilder unforgettabler. For me, I think it was years as a journalist on magazines and papers in Boston and Chicago that made me yearn for what was under mere reporting and accounting. Could I catch and share moments, images, the deeper story? Could you use one tiny story to carry a thousand bigger stories on its shoulders?

David Quammen

I met David Quammen a year ago when I interviewed him about his book Ebola in the wake of the 2014 outbreak. A literary journalist who specializes in ecology and evolutionary biology, Quammen told me, then, that his purposes “are divided about halfway between education and vaudeville” as he tries to make science writing accessible to a broad audience. When I recently asked him about approaching writing with an attitude of playfulness, he made it clear he didn’t like that word:

First thing I want to say is that I distrust programmatic approaches to writing. It can’t be taught. A person is funny or playful if he or she has that capacity. Or not. It’s not a recipe. I love humor. I love surprise. I tend to be a smart aleck. “Playfulness”? Meh.

I pressed him. While playfulness may not be the right word in every case, how writers escape “programmatic” approaches to writing to keep returning and delighting in their work was exactly what I was interested in. How, for instance, does he find moments of relief while writing about infectious disease? He acknowledged the challenge:

The world right now is grim. Problems are dire. It’s rotten, catastrophic. But also filled with wonders, joys, amazing places and things, heroic behaviors. Pratfalls and ridiculosity. It’s always important to be able to laugh in the face of gloom, and in the face of time. I’ve learned that from some of the masters—Samuel Beckett; Faulkner; Ed Abbey; Dorothy Parker; my Irish mother, Mary Egan Quammen.

Quammen noted his humor can be dry and oblique. In Spillover , about the growing incidence of zoonotic diseases (infections that spread from animals to humans), he recounts an instance in which a Texas lab euthanized forty-nine monkeys as a precaution because they shared the same room as one that died and tested positive for Reston virus. Most of the monkeys, later screened posthumously for the virus, tested negative. Without missing a beat, Quammen writes, “Ten employees who had helped unload and handle the monkeys were also screened for infection, and they also tested negative, but none of them were euthanized.”

Gallows humor is helpful, too, if you’re writing about something like Ebola or HIV or herpes B. There’s always room, if it’s done with irony about the brutality of life and with sympathy for the victims’ side. Why not laugh darkly? We need laughter as much as we need pharmaceuticals.

Surprise is something Quammen said he relishes in his work. For him, it comes not from plumbing the depths of memory, but from the people he interviews.

I get interested, immediately, in their whole lives, their whole stories. I wait and hope for them to surprise me. I never ever ever say to a source, “Give me a quote on yadda yadda.” I ask genuine questions. I wait and hope for them to tell me a story because they suddenly feel they can trust me with something they have never told any other person—or, at least, any other writer. Jack Horner did that with me, 35 years ago: dyslexia led him to dinosaur bones. Kelly Warfield did it more recently: working in a 7-Eleven at Fort Detrick led her to Ebola research.

Abigail Thomas

At the writing retreat, Brenda Miller introduced me to Thomas’s first memoir, Safekeeping . She presented it as an example of memoir that—with its tiny micro-chapters, third-person accounts, and soliloquies from Thomas’s sister who comes in now and again to explain the action (a move Miller likened to a Greek chorus)—doesn’t follow convention. It’s a memoir about loss, and yet there are moments when it’s impossible not to laugh. I asked Thomas about the book’s playful tone.

Well, lots of my memories were hilarious, as were the conversations with my sister. Life is full of loss but also a lot of laughs, thank god. And yeah, probably because I had no set plan, no outline, no nothing, anything and everything came marching in. Or slithering. Life is so very funny, right in the middle of everything awful. That’s how we survive, I think.

The way I wrote Safekeeping was determined by the way my memory works (or doesn’t). My memory is terrible, but what I do remember, I remember well. There usually isn’t any interstitial material. After [my second husband] Quin died, these hundreds of little pieces came more or less flying out of me. It wasn’t a plan. I really didn’t know why I was doing what I was doing, didn’t for a long time think it would be a book. I was writing down moments, mostly—moments and feelings I remembered well.

I do think that if you have a memory, and you get it right, you leave it alone. You don’t need to put in the weather report or whatever else is lying around on the grass. Hit it, hit it as best as you can, and move on. And I couldn’t have done it without my sister. Wonderful, the Greek chorus description. Perfect.

Thomas is known for assigning her students “two pages” exercises as a way into a story “they may be staring too directly in the face,” she writes in her book Thinking about Memoir . She recalled a workshop in which she asked students to write two pages about a time they were dressed inappropriately for the occasion:

One woman described what had happened to her first husband. He had been helping load a truck for a neighbor, someone he barely knew, but that was the kind of generous man he was. The truck moved unexpectedly, and her husband was thrown to the ground. By the time they got him to the hospital, he was declared brain-dead. She remembered walking back and forth on the roof of the hospital with her husband’s brother, trying to decide whether or not to take him off life support, and thinking she was wearing the wrong clothes to be making such a decision: cutoffs, a T-shirt, sandals. It was the first time she’d ever written about this, and it was the assignment that gave her a side door. Extremely moving.

Two pages makes it less intimidating. If it goes longer, fine. But it doesn’t have to. We’re not on guard.

There’s a line in Thinking about Memoir that reminds me of the object lesson at the writers’ retreat with the bell: “We do better when we’re not trying too hard,” Thomas writes. “There is nothing more deadening to creativity than the grim determination to write.” How does she avoid the writerly tendency toward grim determination?

Doing absolutely nothing helps. Keep quiet. Take note of what you notice. See what happens. Get out of the way. Stop thinking. Wait for the unlikely pair to couple. Take naps. Especially take naps. If something strikes you while you’re beginning to drift off (and it will), get up immediately and write it down. For me, painting is a wonderful way of using a different part of what’s left of my brain. I just wait for the accident, wait for the thing to reveal itself to me. I’m NOT in charge.

What’s the most fun you’ve ever had writing?

Brenda Miller:

The most fun I’ve ever had writing was when I wrote my first hermit crab piece, “How to Meditate.” I loved poking fun at both myself and the earnestness of the meditation community while still getting at the heart of some essential experiences. It was the first time I felt so immersed in a voice not my own, and I wrote the entire piece in one twelve-hour writing day on retreat at the Ucross Foundation in Wyoming.

Brian Doyle:

Oh man, a nonfiction book about a year in a vineyard: The Grail . That was fun for all sorts of reasons, not just the wine. To write loose and free about a real place and people and science, to write a fun book about wine in a world filled with so many somber, lugubrious books about wine. . . .

David Quammen:

In Spillover, I used the techniques of fiction (which I had once used in writing novels) to give the reader an imagined (truth in advertising) version of how the fateful passage of HIV from a forest-dwelling chimpanzee to the big cities of Central Africa may have happened. It was risky, this movement in a nonfiction book from carefully reported scientific fact into a mythic mode—and it was liberating, and maybe a bit provocative. I can still remember the thrill as my hypothetical story of that event, featuring a character I called the Voyager, unfolded for me each day on the page. It was great fun, in roughly the same way that running a Class V stretch of whitewater in a kayak is fun—dangerous, exhilarating, worth-the-risk fun.

Abigail Thomas:

Well, I had a lot of fun with “Sixteen Again,” the account of a date where I feel madly in love with the guy who did not return the compliment, and got over it very quickly. The essay changed in the course of the writing from a lament to a sort of triumph, and I wound up laughing.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Susan Bruns Rowe

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

Reclaiming Of Mice and Men from Parody

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

Looking for strategies or have questions about how to support your child’s education? Ask our AI-powered assistant.

Parent Resources for Learning > Creativity > 9 Simple Ways to Encourage Creative Play in Your Kids

9 Simple Ways to Encourage Creative Play in Your Kids

by Dr. Jody Sherman LeVos | Jun 16, 2023 | Creativity

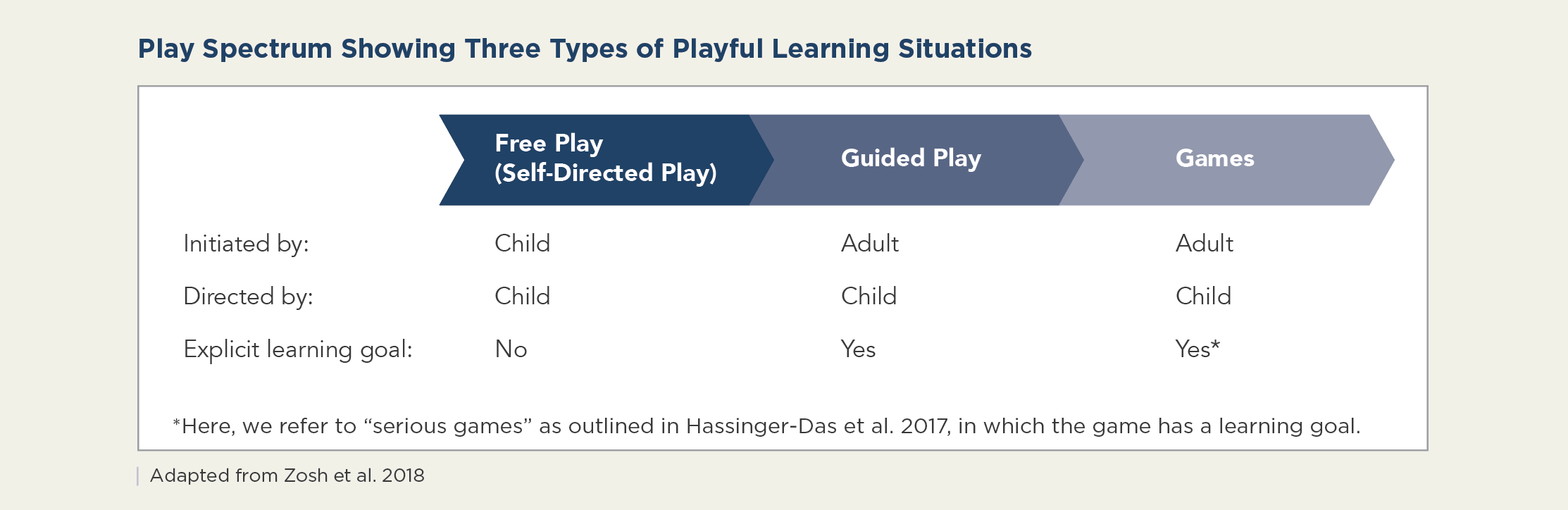

Some people see creative play as a diversionary activity that children do to pass the time. However, creative play is crucial for child development because it helps kids learn essential skills like problem-solving, self-expression, and communication.

Creativity is one of the 5 C’s at the heart of the Begin Approach to helping kids thrive in school and life. It helps kids express themselves through different mediums, think outside the box for solutions, and invent new ideas.

In this article, we’ll look at what creative play is, explore some of its benefits in more detail, and dive into our expert tips on how you can encourage your child to engage in this type of play.

The Short Cut

- Creativity and out-of-the-box thinking will boost your child’s current and future success (and help them have fun!)

- Creative play has far-reaching benefits, from big imaginations to robust problem-solving skills

- Encourage your children to get creative through structured play, boredom, outside play, and art so that their imagination blooms in different ways

- Developing the 5 C’s doesn’t need to be complicated. You can make a big difference in only 15 minutes a day !

What Is Creative Play?

Creative play, also known as imaginative play, is any type of play that allows kids to use their imaginations and express themselves freely.

There are many different types of imaginative play, but some common examples include:

- Pretend play : This is when kids use props and toys to act out scenarios or tell stories. For example, a child might pretend to be a doctor, a firefighter, or a parent.

- Art : Art is an excellent way for kids to express themselves creatively. For example, they can draw, sculpt, paint, or make a collage.

- Music : Making music helps foster creativity. Kids can use instruments, voices, or everyday objects to create sound.

- Dance : Movement allows kids to express themselves. It can include actual dancing or just free movement through running, jumping, or twirling.

All types of creative play are important because they allow kids to explore the world around them, try new things, and use their imaginations . When kids engage in imaginative play, they also develop essential skills they will use throughout their lives.

The Importance of Creative Play

We hinted at it above, but creative play is vital for child development. Let’s take a look at some of the skills it can help improve.

Problem-Solving

When kids are engaged in creative play, they face new challenges. For example, they might have to figure out how to build a tall tower out of blocks or make a character come to life through pretend play.

Through trial and error, they learn how to problem solve and think critically.

Communication

Creative play also helps children develop communication skills. For example, if they are engaging in pretend play with others, they must communicate with their playmates to make the story work. This involves taking turns, listening, and speaking.

Critical Thinking

This type of play also provides plenty of opportunities to make decisions and choose between options. For example, your child might have to decide what story to tell or what character to pretend to be.

Having to make these types of decisions helps them learn to think critically about the world around them and examine their choices.

Because critical thinking requires us to absorb information and make judgments about that information, it takes imagination and curiosity. As kids take in new information—like when they’re playing—they must consider how this information fits (or doesn’t fit) in with what they already know.

Age-Appropriate Play for Kids

Now that we’ve looked at some of the benefits, it’s important to note that creative play is vital for kids of all ages. But the type of play appropriate for your child will depend on their age and stage of development.

Here are some types of creative play you might notice kids engaging in at different ages.

Babies (0-12 months)

Babies are just beginning to explore the world around them at this age. They might start to engage in something called “enactive naming,” which is the beginning of pretend play.

During this phase, your baby isn’t actively playing, but they’re showing their knowledge by mimicking actions they’ve seen, like holding a cup or spoon to their mouth. This is also a time when they love to experience new textures and sounds.

Toddlers (1-3 years)

Toddlers are full of energy and love to move. They might dance and enjoy active games, or they might start to “pretend play” with simple props. Toddlers also love to explore art through creative activities, like finger painting and playdough.

Preschoolers (3-5 years)

Preschoolers are beginning to understand the world around them more. At this age, they might engage in more complex dramatic play , like pretending to be a doctor or a chef. They also love to express themselves through art and music.

School-Age Kids (6-12 years)

School-age kids are beginning to think more abstractly. As a result, they might try more complex pretend play, like creating entire worlds with their friends. At this age, they might also start to express themselves through writing stories or making films.

How to Encourage Creative Play

Now that you know what this type of play looks like and why it’s so important, you might wonder how you can encourage your child to engage in creative play. Here are some of our expert tips.

1. Provide Ample Free Time

If your child’s entire day is full of structured, adult-led activities, they won’t have much time for independent creative play. Instead, make sure they have plenty of free time to explore and play on their own.

2. Let Your Child Be Bored

Boredom can be a good thing! When your child is bored, they are more likely to get creative.

You don’t need to entertain your child every minute of the day. Let them get bored sometimes and see what activities they come up with.

3. Focus on Open-Ended Toys

Open-ended toys are the best for encouraging creativity. Provide your child with toys, such as blocks, puppets, and art supplies. Try to avoid toys that only have one purpose or outcome.

In addition to encouraging creativity, open-ended toys have another benefit: Your child won’t outgrow them as quickly, so they’ll get a lot of use!

4. Foster Different Play Experiences

Creative play can happen when your child is playing alone. But it can also happen when they’re playing with you or their friends.

These different experiences help your child build unique skills, so be sure to provide opportunities for both solo and cooperative play . Playdates are great ways for your child to develop this skill set. Just try not to fill their schedule too much!

5. Enjoy Time Outside

There’s nothing like time spent in nature to encourage creative pursuits. Kids can explore, imagine, and run to their heart’s content when they are outside. They can also use natural items to create art or try to build a fort out of sticks and leaves.

Let your child play in different environments, like the sand at the beach or the mud in the backyard. This is great for their creative development, and it’s a fantastic way to get them moving and burn off some energy!

6. Support Exploration and New Ideas

Encouraging your child’s creativity is one of the best things you can do for their development. It helps them to think outside the box, problem-solve, and express themselves in unique ways.

But, if you’re trying to control their play or tell them what to do, you’re stifling their creativity. Instead, try to support their unique ideas and exploration.

For example, if they want to use the camera from our HOMER Explore Letters Kit to pretend they’re a wildlife photographer, let them! If they want to move the pieces on a Monopoly board randomly, that’s OK, too! Let them lead the way.

7. Embrace the Mess

It’s important to embrace the mess during creative play. Don’t interrupt your child to make them stop and clean up. Just let them have fun and explore.

Of course, to avoid complete chaos, it’s a good idea to set up some ground rules before they start playing. For example, you might want to designate a specific area for their art project or put down a sheet to protect your furniture.

You’ll also want to keep your child’s safety, age, and development in mind. For example, turning a toddler loose with a bottle of glitter might not be the best idea (but you already know that)!

8. Model Creative Play

If you want your child to be creative, one of the best things you can do is be an innovative role model. Show them it’s OK to experiment, try new things, and make mistakes.

Engage in activities alongside them. Get out the paints and make a picture together. Build a fort with blankets and pillows. Or get down on the floor at their level and create a city out of blocks.

You can also host a “tea party” with your child and their dolls, open a vet clinic for their stuffed animals, or dress up with them. Remember to take it easy; dressing up doesn’t have to be elaborate. A bandana made from a large cloth napkin is just as much fun as a store-bought costume!

9. Provide Accessible Art Supplies

When inspiration strikes, your child should be able to easily access the supplies they need to bring their ideas to life. This means having a well-stocked art area.

Of course, you don’t need to go all out, but it’s a good idea to have a selection of basics, like crayons, markers, pencils, paints, paper, glue, and scissors. You can include fun extras like stickers, glitter, and feathers if you want, too.

The type of supplies you choose should depend on your child’s age and ability. For instance, toddlers don’t need unfettered access to scissors and glue. But having some paper and crayons within reach can help encourage creativity.

Creative Play for Creative Kids!

Creative play helps your child learn to think outside the box. It allows them to take their ideas and dreams and turn them into reality. And it’s an excellent way for kids to express themselves, explore their interests, and get active.

For more fun ideas to help your child learn through play, check out our HOMER app. For something more hands-on, try our age-appropriate activity kit subscriptions in STEM, cooking, animals, culture and more with Little Passports !

With the right supplies, freedom, and encouragement, your child will be practicing their newfound skills in no time.

Jody has a Ph.D. in Developmental Science and more than a decade of experience in the children’s media and early learning space.

View all posts

Dr. Jody Sherman LeVos

Chief Learning Officer at Begin

Related Posts

8 Ways to Use Holistic Skill Development to Help Your Whole Child Thrive

Our approach to learning makes a great foundation for holistic skill development. Check out 8 activities you can do at home.

Keep Reading →

Understanding Your Picky Eater: A List of Foods to Try (and How to Find More)

Many kids are picky eaters. Find out some common reasons why and expand the list of foods your child will eat!

7 Creative, Rewarding Ways to Teach Empathy to Kids at Home

Check out some creative ways to teach empathy to kids, and help your child develop a compassionate mindset as you work on empathy skills.

8 Ways to Raise Confident Kids at Home (for Girls and Boys!)

Confidence helps kids throughout their lives. Try these parenting strategies and activities and start raising confident kids at home!

5 Fun Activities to Build Social Skills for Preschoolers

Social skills activities can help your preschooler learn how to interact with the world. Try these five at home!

6 Ways to Make Curiosity-Building Sensory Bottles

Sensory play helps kids build curiosity. Try these six ways to make sensory bottles for your family!

9 Effective Emotional Regulation Activities for Kids in 2024

Emotional regulation is an important skill, but our kids aren’t just born with it. Find out how to teach it to your child!

5 Fun Critical Thinking Games to Play with Your Child

Critical thinking is an essential early learning skill! Check out these 5 games that help kids build it!

Bring Calm to Your Child’s Body with These 8 Breathing Exercises

Even one minute of breathing can reduce stress and anxiety for your child. Check out these exercises to see which might help your child learn how to find calm.

6 Key Goals for Enhancing Social Skills in Children at Home

Social skills are the building blocks of healthy relationships. Find out how to set social skills goals for your child and practice achieving them!

5 Activities for Teaching Kindness Lessons to Kids

Showing kindness means focusing your attention on another person, recognizing what they are feeling and what they need, and then offering them something. It’s giving your sister the last cookie in the jar. It’s playing a game because it’s your friend’s favorite....

13 Invention Ideas for Kids and Why They Matter

Inventing new things helps kids develop creativity and critical thinking. Try these 13 invention ideas!

The Value of Play I: The Definition of Play Gives Insights

Freedom to quit is an essential aspect of play's definition..

Posted November 19, 2008 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Play in our species serves many valuable purposes. It is a means by which children develop their physical, intellectual, emotional, social, and moral capacities. It is a means of creating and preserving friendships. It also provides a state of mind that, in adults as well as children, is uniquely suited for high-level reasoning, insightful problem solving, and all sorts of creative endeavors.

This essay is the first in a series I plan to post on The Value of Play . The subject of this first installment is the definition of play. Clues to play’s value lie in the definition.

Most of this essay is about the defining characteristics of play, but before listing them there are three general points that I think are worth keeping in mind. The first point is that the characteristics of play all have to do with motivation and mental attitude, not with the overt form of the behavior. Two people might be throwing a ball, or pounding nails, or typing words on a computer, and one might be playing while the other is not. To tell which one is playing and which one is not, you have to infer from their expressions and the details of their actions something about why they are doing what they are doing and their attitude toward it.

The second point, toward definition, is that play is not necessarily all-or-none. Play can blend with other motives and attitudes, in proportions ranging anywhere from 0 up to 100 percent play. Pure play occurs more often in children than in adults. In adults, play is commonly blended with other motives, having to do with adult responsibilities. That is why, in everyday conversation, we tend to talk about children “playing” and about adults bringing a “playful attitude” or “playful spirit” to their activities. We intuitively think of playfulness as a matter of degree. Of course, we don’t have meters for measuring these things, but I would estimate that my behavior in writing this blog is about 80% play.

The third point is that play is not neatly defined in terms of some single identifying characteristic. Rather, it is defined in terms of a confluence of several characteristics. People before me who have studied and written about play have, among them, described quite a few such characteristics; but they can all be boiled down, I think, to the following five:

- Play is self-chosen and self-directed.

- Play is activity in which means are more valued than ends.

- Play has structure, or rules, which are not dictated by physical necessity but emanate from the minds of the players.

- Play is imaginative, non-literal, mentally removed in some way from “real” or “serious” life.

- Play involves an active, alert, but non- stressed frame of mind.

The more fully an activity entails all of these characteristics, the more inclined most people are to refer to that activity as play. By “most people,” I don’t just mean most scholars who study play. Even young children are most likely to use the wordplay for activities that most fully contain these five characteristics. These characteristics seem to capture our intuitive sense of what play is. Notice that all of the characteristics have to do with the motivation or attitude that the person brings to the activity.

Let me elaborate on these characteristics, one by one, and expand a bit on each by pointing out some of its implications for thinking about the purposes of play.

1. Play is self-chosen and self-directed; players are always free to quit.

Play is, first and foremost, an expression of freedom. It is what one wants to do as opposed to what one is obliged to do. The joy of play is the ecstatic feeling of liberty. Play is not always accompanied by smiles and laughter , nor are smiles and laughter always signs of play; but play is always accompanied by a feeling of “Yes, this is what I want to do right now.” Players are free agents, not pawns in someone else’s game.

Players not only choose to play or not play, but they also direct their own actions during play. As I will argue below, play always involves rules of some sort, but all players must freely accept the rules, and if rules are changed then all players must agree to the changes. That is why play is the most democratic of all activities. In social play (play involving more than one player), one player may emerge for a period as the leader , but only at the will of all the others. Every rule a leader proposes must be approved, at least tacitly, by all of the other players.

The ultimate freedom in play is the freedom to quit. A person who feels coerced or pressured to engage in an activity, and unable to quit, is not a player but a victim. The freedom to quit provides the foundation for all of the democratic processes that occur in social play. If one player attempts to bully or dominate the others, the others will quit and the game will be over; so players who want to continue playing must learn not to bully or dominate. People who don’t agree to a proposed change in rules may likewise quit, and that is why leaders in play must gain the consent of the other players in order to change a rule. People who begin to feel that their needs or desires are not being met in play will quit, and that is why children learn, in play, to be sensitive to others’ needs and to strive to meet those needs. It is through social play that children learn, on their own, with no lectures, how to meet their own needs while, at the same time, satisfying the needs of others. This is perhaps the most important lesson that people in any society can learn.

This point about play being self-chosen and self-directed is ignored by, or perhaps unknown to, many adults who try to take control of children’s play. Adults can play with children, and in some cases can even be leaders in children’s play, but to do so requires at least the same sensitivity that children themselves show to the needs and wishes of all the players. Because adults are commonly viewed as authority figures, children often feel less able to quit, or to disagree with the proposed rules, when an adult is leading than when a child is leading. And so, when adults try to lead children’s play the result often is something that, for many of the children, is not play at all. When a child feels coerced, the play spirit vanishes and all of the advantages of that spirit go with it. Math games in school and adult-led sports are not play for those who feel that they have to participate and are not ready to accept, as their own, the rules that the adults have established. Adult-led games can be great for kids who freely choose them, but can seem like punishment to kids who haven’t made that choice.

What is true for children’s play is also true for adults’ sense of play. Research studies have shown that adults who have a great deal of freedom as to how and when to do their work often experience that work as play, even (in fact, especially) when the work is difficult. In contrast, people who must do just what others tell them to do at work rarely experience their work as play.

2. Play is an activity in which means are more valued than ends.

Many of our actions are “free” in the sense that we don’t feel that other people are making us do them, but are not free, or at least are not experienced as free, in another sense. These are actions that we feel we must do in order to achieve some necessary or much-desired goal, or end. We scratch an itch to get rid of the itch, flee from a tiger to avoid getting eaten, study an uninteresting book to get a good grade on a test, work at a boring job to get money. If there were no itch, tiger, test, or need for money, we would not scratch, flee, study, or do the boring work. In those cases we are not playing.

To the degree that we engage in an activity purely to achieve some end, or goal, which is separate from the activity itself, that activity is not play. What we value most, when we are not playing, are the results of our actions. The actions are merely means to the ends. When we are not playing, we typically opt for the shortest, least effortful means of achieving our goal. The non-playful, goal-oriented college student, for example, does the least studying in each course that she can in order to get the “A” that she desires, and her studying is focused directly on the goal of doing well on the tests. Any learning not related to that goal is, for her, wasted effort.

In play, however, all this is reversed. Play is activity conducted primarily for its own sake. The playful student enjoys studying the subject and cares less about the test. In play, attention is focused on the means, not the ends, and players do not necessarily look for the easiest routes to achieving the ends. Think of a cat preying on a mouse versus a cat that is playing at preying on a mouse. The former takes the quickest route for killing the mouse. The latter tries various ways of catching the mouse, not all very efficient, and lets the mouse go each time so it can try again. The preying cat enjoys the end; the playing cat enjoys the means. (The mouse, of course, enjoys none of this.)

Play often has goals, but the goals are experienced as an intrinsic part of the game, not as the sole reason for engaging in the game’s actions. Goals in play are subordinate to the means for achieving them. For example, constructive play (the playful building of something) is always directed toward the goal of creating the object that the player has in mind. But notice that the primary objective in such play is the creation of the object, not the having of the object. Children making a sandcastle would not be happy if an adult came along and said, "You can stop all your effort now. I'll make the castle for you." That would spoil their fun. The process, not the product, motivates them. Similarly, children or adults playing a competitive game have the goal of scoring points and winning, but, if they are truly playing, it is the process of scoring and trying to win that motivates them, not the points themselves or the status of having won. If someone would just as soon win by cheating as by following the rules, or get the trophy and praise through some shortcut that bypasses the game process, then that person is not playing.

Adults can test the degree to which their work is play by asking themselves this: “If I could receive the same pay, the same prospects for future pay, the same amount of approval from other people, and the same sense of doing good for the world for not doing this job as I am receiving for doing it, would I quit?” If the person would eagerly quit, the job is not play. To the degree that the person would quit reluctantly, or not quit, the job is play. It is something that the person enjoys independently of the extrinsic rewards received for doing it.

One reason why play is such an ideal state of mind for creativity and learning is because the mind is focused on means. Since the ends are understood as secondary, fear of failure is absent and players feel free to incorporate new sources of information and to experiment with new ways of doing things.

3. Play is guided by mental rules.

Play is freely chosen activity, but it is not freeform activity. Play always has structure, and that structure derives from rules in the player’s mind. This point is really an extension of the point just made about the importance of means in play. The rules of play are the means. To play is to behave in accordance with self-chosen rules. The rules are not like rules of physics, nor like biological instincts, which are automatically followed. Rather, they are mental concepts that often require conscious effort to keep in mind and follow.

A basic rule of constructive play, for example, is that you must work with the chosen medium in a manner aimed at producing or depicting some specific object or design. You don’t just pile up blocks randomly; you arrange them deliberately in accordance with your mental image of what you are trying to make. Even rough and tumble play (playful fighting and chasing), which may look wild from the outside, is constrained by rules. An always-present rule in play fighting, for example, is that you mimic some of the actions of real fighting, but you don’t really hurt the other person. You don’t hit with all your force (at least not if you are the stronger of the two); you don’t kick, bite, or scratch. Play fighting is much more controlled than real fighting; it is always an exercise in restraint.

Among the most complex forms of play, in terms of rules, is what play researchers call sociodramatic play—the playful acting out of roles or scenes, as when children are playing “house,” or acting out a marriage , or pretending to be superheroes. The fundamental rule here is that you must abide by your and the other players’ shared understanding of the role that you are playing. If you are the pet dog in a game of “house,” you must walk around on all fours and bark rather than talk. If you are Wonder Woman, and you and your playmates believe that Wonder Woman never cries, then you refrain from crying, even when you fall down and hurt yourself.

To illustrate the rule-based nature of sociodramatic play, the Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky wrote about two actual sisters—ages seven and five—who sometimes played that they were sisters.[1] As actual sisters, they rarely thought about their sisterhood and had no consistent way of behaving toward one another. Sometimes they enjoyed one another, sometimes they argued, and sometimes they ignored one another. But, when they were playing sisters, they always behaved according to their shared stereotype of how sisters should behave. They dressed alike, talked alike, always loved one another, talked about the differences between themselves and everyone else, and so on. Much more self-control , mental effort, and rule following was involved in playing sisters than in being sisters.

The category of play with the most explicit rules is that called formal games. These are games, like checkers and baseball, with rules that are specified, verbally, in ways designed to minimize ambiguity in interpretation. The rules of these games are commonly passed along from one generation of players to the next. Many formal games in our society are competitive, and one purpose of the formal rules is to make sure that the same restrictions apply equally to all competitors. Players of formal games, if they are true players, must adopt these rules as their own for the period of the game and be willing to stick to them. Of course, except in “official” versions of such games, players commonly modify the rules to fit their own needs, but each modification must be agreed upon by all the players.

The main point I want to make here is that every form of play involves a good deal of self-control. When not playing, children (and adults too) may act according to their immediate biological needs, emotions, and whims; but in play they must act in ways that they and their playmates deem appropriate to the game. Play draws and fascinates the player precisely because it is structured by rules that the player herself or himself has invented or accepted.

The student of play who most strongly emphasized play’s rule-based nature was Lev Vygotsky, whose example of sisters playing sisters I just mentioned. In an essay on the role of play in development, originally published in 1933, Vygotsky commented, as follows, on the apparent paradox between the idea that play is spontaneous and free and the idea that players must follow rules:

“The … paradox is that in play [the child] adopts the line of least resistance—she does what she most feels like doing because play is connected with pleasure—and at the same time she learns to follow the line of greatest resistance by subordinating herself to rules and thereby renouncing what she wants, since subjection to rules and renunciation of impulsive action constitute the path to maximum pleasure in play. Play continually creates demands on the child to act against immediate impulse. At every step the child is faced with a conflict between the rules of the game and what she would do if she could suddenly act spontaneously. … Thus, the essential attribute of play is a rule that has become a desire. …. The rule wins because it is the strongest impulse. Such a rule is an internal rule, a rule of self-restraint and self-determination …. In this way a child’s greatest achievements are possible in play, achievements that tomorrow will become her basic level of real action and morality .”[1]

Vygotsky's point, of course, is that the child's desire to play is so strong that it becomes a motivating force for learning self-control. The child resists impulses and temptations that would run counter to the rules because the child seeks the larger pleasure of remaining in the game. To Vygotsky's analysis, I would add that the child accepts and desires the rules of play only because he or she is always free to quit if the rules become too burdensome. With that in mind, the paradox can be seen to be superficial. The child's real-life freedom is not restricted by the rules of the game, because the child can at any moment choose to leave the game. That is another reason why the freedom to quit is such a crucial aspect of the definition of play. Without that freedom, rules of play would be intolerable. To be required to act like Wonder Woman in real life would be terrifying, but to act like that in play––a realm you are always free to leave––is great fun.

Along with Vygotsky, I would contend that the greatest of play’s many values for our species lies in the learning of self-control. Self-control is the essence of being human. We commonly say that people behave like “animals,” rather than like humans, when they fail to abide by socially agreed-upon rules and, instead, impulsively follow their immediate drives and whims. Everywhere, to live in human society, people must behave in accordance with conscious, shared mental conceptions of what is appropriate; and that is what children practice constantly in their play. In play, from their own desires, children practice the art of being human.

4. Play is non-literal, imaginative, marked off in some way from reality.

Another apparent paradox of play, also pointed out by Vygotsky, is that play is serious yet not serious, real yet not real. In play one enters a realm that is physically located in the real world, makes use of props in the real world, is often about the real world, is said by the players to be real, and yet in some way is mentally removed from the real world.

Imagination , or fantasy , is most obvious in sociodramatic play, where the players create the characters and plot, but it is also present to some degree in all other forms of human play. In rough and tumble play, the fight is a pretend one, not a real one. In constructive play, the players say that they are building a castle, but they know it is a pretend castle, not a real one. In formal games with explicit rules, the players must accept an already established fictional situation that provides the foundation for the rules. For example, in the real world bishops can move in any direction they choose, but in the fantasy world of chess they can move only on the diagonals.

The fantasy aspect of play is intimately connected to play’s rule-based nature. Because play takes place in a fantasy world, it must be governed by rules that are in the minds of the players rather than by laws of nature. In reality, one cannot ride a horse unless a real horse is physically present; but in play one can ride a horse whenever the game's rules permit or prescribe it. In reality, a broom is just a broom, but in play it can be a horse. In reality, a chess piece is just a carved bit of wood, but in chess it is a bishop or a knight that has well-defined capacities and limitations for movement that are not even hinted at in the carved wood itself. The fictional situation dictates the rules of the game; the actual physical world within which the game is played is secondary. Through play the child learns to take charge of the world and not simply respond passively to it. In play the child’s mental concept dominates, and the child molds available elements of the physical world to meet that concept.

Play of all sorts has “time in” and “time out,” though that is more obvious for some forms of play than others. Time in is the period of fiction. Time out is the temporary return to reality—perhaps to tie one’s shoes, or go to the bathroom, or correct a playmate who hasn't been following the rules. During time in one does not say, “I am just playing,” any more than does Shakespeare’s Hamlet announce from the stage that he is merely pretending to murder his stepfather.

Adults sometimes become confused by the seriousness of children’s play and by children’s refusal, while playing, to say that they are playing. They worry needlessly that children don’t distinguish fantasy from reality. When my son was four years old he was Superman for periods that sometimes lasted more than a day. During those periods he would deny vigorously that he was only pretending to be Superman, and this worried his nursery school teacher. She was only partly mollified when I pointed out that he never attempted to leap off of actual tall buildings or stop real railroad trains and that he would acknowledge that he had been playing when he finally did declare time out by removing his cape. To acknowledge that play is play is to remove the magic spell; it automatically turns time in into time out.

An amazing fact of human nature is that even 2-year-olds know the difference between real and pretend. A 2-year-old who turns a cup filled with imaginary water over a doll and says, “Oh oh, dolly all wet,” knows that the doll isn’t really wet. It would be impossible to teach such young children such a subtle concept as pretense, yet they understand it. Apparently, the fictional mode of thinking, and the ability to keep that mode distinct from the literal mode, are innate to the human mind. That innate capacity is part of the inborn capacity for play.

The fantasy element of play is often not as obvious, or as full-blown, in adults’ play as in children’s play. That is one reason why adults’ play is typically not of the 100% variety. Yet, I would argue, fantasy occupies a big role in much if not most of what adults do and is a major element in our intuitive sense of the degree to which adult activities are play. An architect designing a house is designing a real house. Yet, the architect brings a good deal of imagination to bear in visualizing the house, imagining how people might use it, and matching it with some aesthetic concepts that she has in mind. It is reasonable to say that the architect builds a pretend house, in her mind and on paper, before it becomes a real one.

When I say that my writing this blog is about 80% play, I am taking into account not only my sense of freedom about doing it, my enjoyment of the process, and the fact that I’m following rules (about writing) that I accept as my own, but also the fact that a considerable degree of imagination is involved. I’m not making up the facts, but I am making up the way of stringing them together, and I am imagining how you might respond to what I am writing. Sometimes my fantasy goes even further, and I imagine that the ideas I’m presenting will have certain positive effects on society. So, fantasy is moving me along in this, much as it moves a child along in building a sandcastle or pretending to be Superman. The fact that parts of my fantasy could possibly turn into reality does not negate its status as fantasy.

5. Play involves an active, alert, but non-stressed frame of mind.

This final characteristic of play follows naturally from the other four. Because play involves conscious control of one’s own behavior, with attention to process and rules, it requires an active, alert mind. Players do not just passively absorb information from the environment , or reflexively respond to stimuli, or behave automatically in accordance with habit. Moreover, because play is not a response to external demands or immediate strong biological needs, the person at play is relatively free from the strong drives and emotions that are experienced as pressure or stress. And because the player’s attention is focused on process more than outcome, the player’s mind is not distracted by fear of failure. So, the mind at play is active and alert, but not stressed. The mental state of play is what some researchers call “flow.” Attention is attuned to the activity itself, and there is reduced consciousness of self and time. The mind is wrapped up in the ideas, rules, and actions of the game.

This point about the mental state of play is very important for understanding play’s value as a mode of learning and creative production. The alert but unstressed condition of the playful mind is precisely the condition that has been shown repeatedly, in many psychological experiments, to be ideal for creativity and the learning of new skills. Such experiments are normally not described as experiments on play, but it is no stretch to interpret them as that. What the experiments show is that strong pressure to perform well (which induces a non-playful state) improves performance on tasks that are mentally easy or habitual for the person, but worsens performance on tasks that require creativity, or conscious decision making , or the learning of new skills. In contrast, anything that is done to reduce the person’s concern with outcome and to increase the person’s enjoyment of the task for its own sake—that is, anything that increases playfulness—has the opposite effect.

Strong pressure to perform well inhibits creativity and learning by focusing attention strongly and narrowly on the goal, thereby reducing the ability to focus on means. In the pressured state, one tends to fall back on instinctive or well-learned ways of doing things. That way of responding to pressure is adaptive in many emergency situations. When a tiger is chasing you, you use whatever means you have already learned for getting away or hiding; that is not a good time to experiment with new ways. Experts in any realm can usually perform well in the pressured state because they can call on their well-learned, habitual modes of responding and don’t need to learn anything new or act creatively. Their attention can focus on producing the best possible outcome using the repertoire of actions that are already second nature to them.

When we pressure students to do well on their schoolwork by constantly evaluating their work, we put them into a non-playful, goal-directed state that may motivate those who already know how to do it to perform well, but inhibits experimentation and learning in those who don’t already know how. Pressure widens the performance gap between experts and novices. Even experts, though, must play at their activity of expertise if they are going to rise to still higher levels of expertise. And, in some realms, such as art and essay writing, creativity is required no matter how much experience a person has had, and a playful mind always performs best in those realms.

When an activity becomes so easy, so habitual, that it no longer requires conscious mental effort, it may lose its status as play. That is why players keep making the game harder, or different, or keep raising the criteria for success. A game is a game only if an active, alert mind is required to do it well.