- Learning Tips

- Exam Guides

- School Life

How to Define a Word in an Essay: Text, Sentence, or Paragraph

- by Joseph Kenas

- December 1, 2023

- Writing Tips

While writing your essay, you may feel the passion for using specific words that could be challenging for the reader to understand what you are referring to. In this guide, we teach you how to define a word in an essay, in a text, sentence, or within a paragraph.

In as much as you understand the easy topic inside out, the potential reader may hang while reading new vocabulary.

It could be awkward if you write word-to-word definitions from your dictionary. Also, it could disorganize or be confusing if you use the definition in the wrong part.

The best way to use definitions effectively is by using your own words and remaining concise. You can opt to introduce definitions in the essay’s body instead of in the introduction.

Before elaborating on the word in definition terms, determine whether the word is unusual enough to require a definition.

While is it acceptable for you to define technical jargon in your essay, avoid defining every advanced vocabulary in the essay.

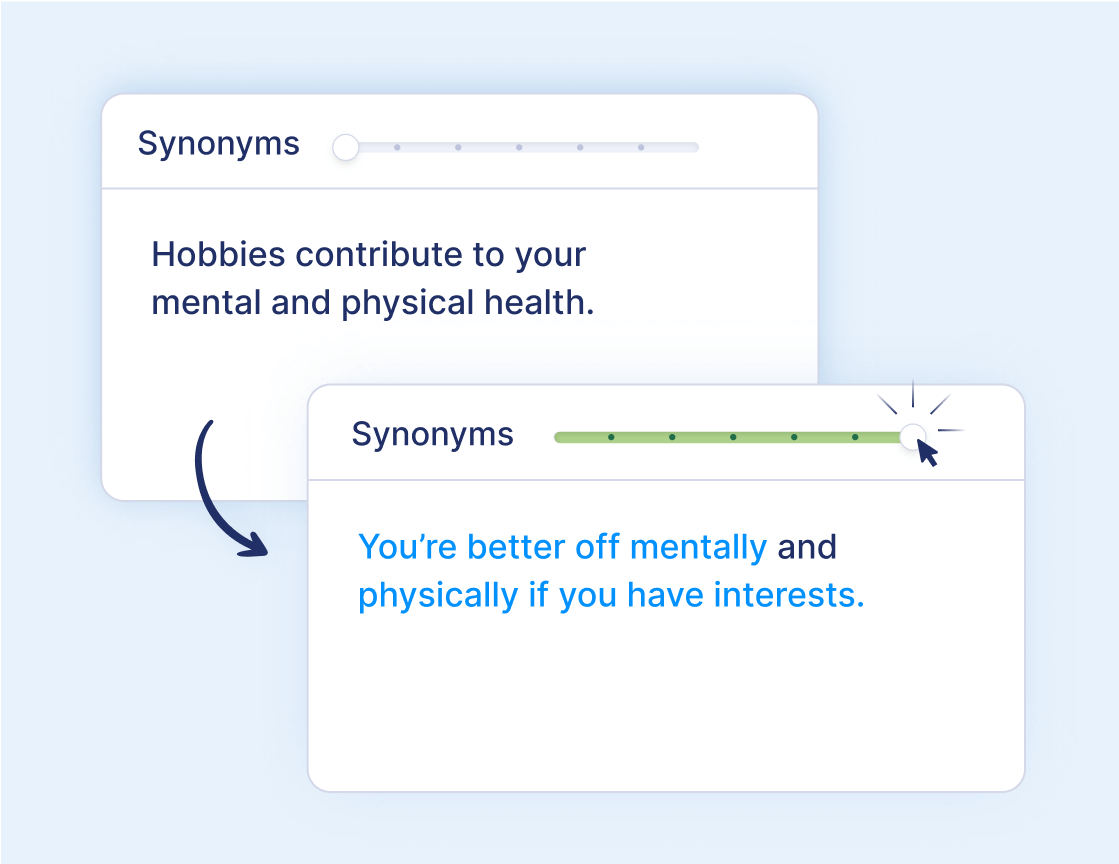

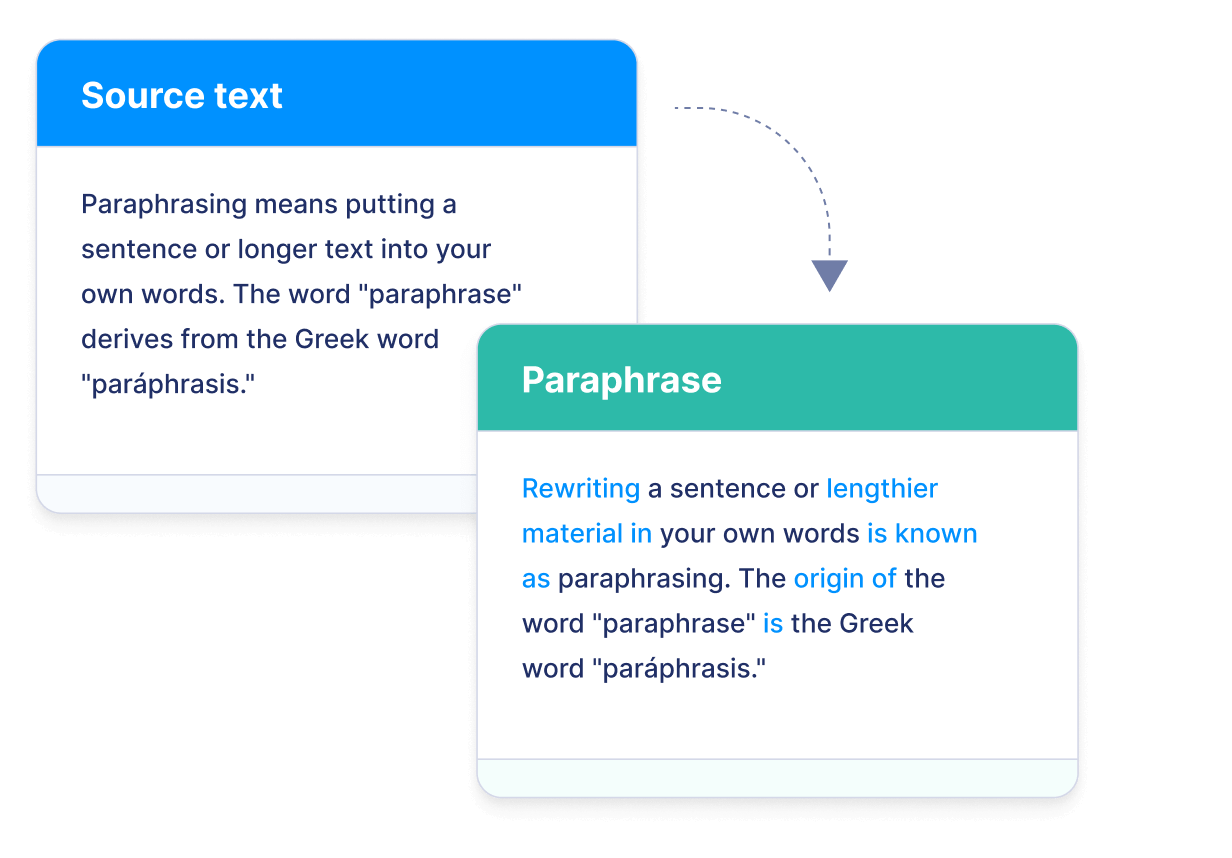

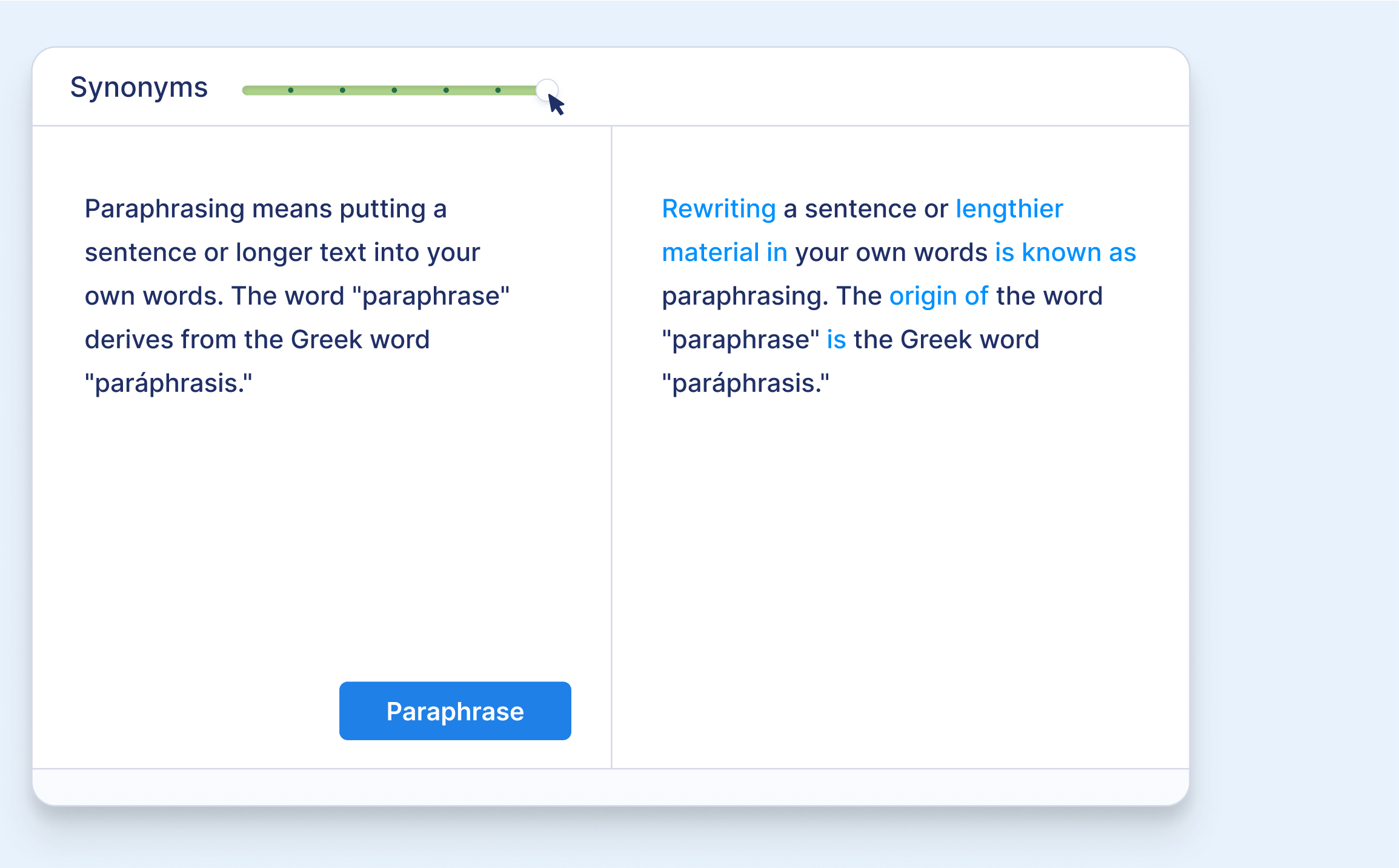

Rephrase the definition in your own words. You must include a full quotation if you are word-to-word definition from the dictionary. For instance, you can make the sentence flow better by

defining a word like ‘workout’, as follows: “Workout is an exercise of improving one’s fitness and performance.”

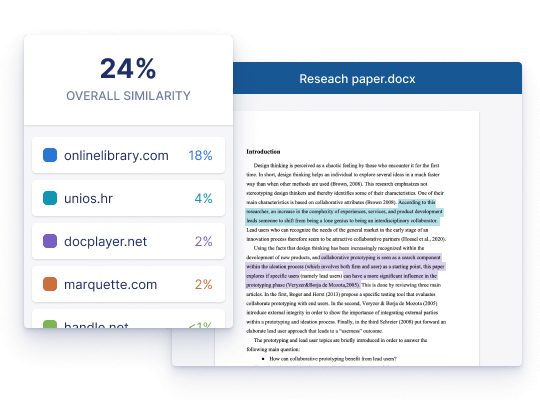

If you are using in-text citations, you should cite the dictionary or the textbook that you took the definition from when you end the sentences.

When it is the first time you are using such a source, then use the full title backed by the abbreviation. By doing correct referencing of the definition source you used, you will be avoiding plagiarism in your essay.

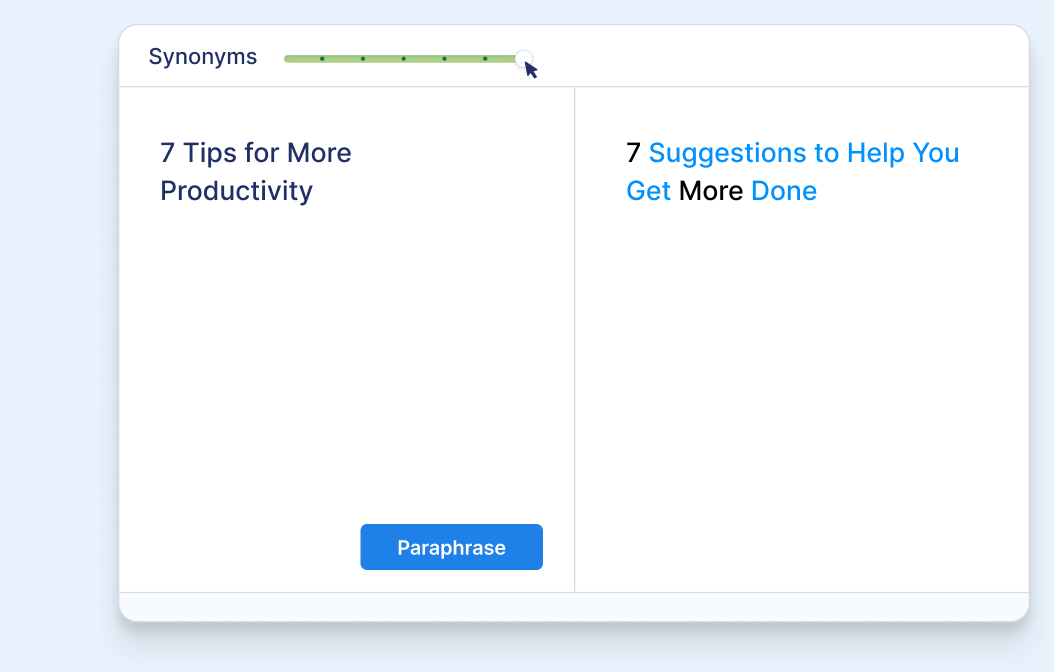

Let the definition be in the body and not the introduction since the introduction ought to catch the reader’s attention as you lay your thesis. Alternatively, if you want to avoid defining a word, then use synonyms.

Keep the definition as short as possible. But, if you believe the definition could belong, then you can break it into shorter sentences to bring clarity to your essay.

How to Define a Word in a Sentence

Do you want to explain something in the middle of the sentence without confusing the reader?

While it is true that you may be harboring a lot of terminologies in your context that require some explanation, you must do it tactfully to promote the flow of your sentences well.

There are three ways you can insert a definition in the mid-sentence as provided by the following examples.

1. By Using Commas

You can use commas as a way of punctuating your sentence to enhance the meaning. For example:

“John and Joseph had to see Bill gates, the leader of Microsoft Corporation, and advise him….”

2. Em and En Dashes

They are not synonymous with hyphens but are needed to punctuate your sentence and restore your intended meaning. For example, we can paraphrase the above sentence to appear as follows:

“John and Joseph had to see Bill gates — the leader of Microsoft Corporation — and advise him….”

3. Parenthetical Aside

It is also another suitable method to use when inserting a definition in the mid-sentence to update the reader with additional facts.

“John and Joseph had to see Bill gates (the leader of Microsoft Corporation) and advise him….”

How to Quote a Definition in a Sentence/Essay

When writing your essay, you will encounter such issues, which are usually unavoidable. If we assume that you are using APA style for referencing, one must quote a definition inside double quotes.

That is “Definition,” and put the author, year, and page numbers.

A definition in an essay examples

- McCarthy and George (1990) defined the essay as “a literary composition which represents author’s arguments on a specific topic.” P.87

- An essay is “a literary composition which represents author’s arguments on a specific topic.” (McCarthy and George, 1990, P.87)

- McCarthy and George (1990, P.87) defined an essay as “a literary composition which represents author’s arguments on a specific topic.”

Such definitions come in handy when you are writing essays that require you to understand one thing well. A good example is when writing a comparison essay or a definition essay. Let us explore how to write a definition essay here.

Tips on How to Write a Definition Essay

A definition essay could be a piece of writing where you write your own meaning. One must ensure that you research your definition well and support it with evidence.

In addition, it could be an explanation of what specific terms mean in your context. This becomes a paragraph. Check out how to write good definition paragraphs and understand them from another perspective.

Some of the terms could have literal meanings, like a phone, tablet, or spoon.

Other abstracts, such as truth, love, or success, will depend on the person’s point of view.

Different papers carry varying meanings; hence when writing one, you must be precise to help the reader understand what you are talking about.

It could be reasonable if you remain unique as you write a definition essay. Avoid expressing meaning using the same words.

Before you choose a definition essay topic, ensure that you select an abstract word that has a complex meaning. Also, ensure that the same word is indisputable.

Tips on How to Define a Word in a Text or Paragraph

1. select a word.

The main point of view when writing an essay is selecting an idea or concept. Select a word that will describe an idea like hate, love, etc., and ensure that you understand the term you are choosing completely.

You can read from the dictionary but avoid extracting the definition from there. Instead, explain it in your own words.

Suppose your concept is open, then find your unique definition based on experience. After that, find the basis to support your definitions.

2. Select a Word That You Know

It is suitable to settle for the word that you are familiar with and you have a basic understanding of the word. Doing so helps you to write easily. For example, you can select a word like ‘pride’ because you understand its meaning and what it feels as you use it in your context.

3. Select a Word With Different Meanings

Selecting a word with plural meanings comes in handy when you believe it will bring a different meaning to various people. As you write about it, there is an opportunity to involve your understanding and interpretations of other people.

For example, one can select a word like “love” because it comes with varying meanings. Every person will understand and interoperate it uniquely.

4. Avoid Specific Things and Objects

Stay away from selecting such things as “cups “or “pillow” because it complicates your writing because you cannot write a lot on specific objects. That makes the essay appear superficial and not shrewd enough.

5. Go Online

With an internet connection, you can seek an online platform and get enough information about what you want. The internet has several scholarly academic blogs and articles.

Additionally, you can still access videos created by smart people who deeply researched different words and shared them with you.

6. Access the Dictionary

It is true that every official word has a deeper dictionary meaning. Tactfully, it is vital that you familiarize yourself with yourself before using it in your contexts.

You must take a closer look at the definition structure before deciding to use it. Ensure that you explain it in your own understanding when writing about it.

7. Know the Origin of the Word

Before using a specific word, it is critical to study and understand its origin. One way of researching the word is involving encyclopedias to get theories and ideas about that particular word.

For instance, if you are picking a word in the medical field, then you should consult the encyclopedia in the medical field.

8. Ask Colleagues

While it is crucial to have your perspective about the word, you can still ask friends and family about the meaning of that particular word.

Let them explain to you what it feels when you mention such a particular word. Later, you can record the answers and utilize them as your sources.

Joseph is a freelance journalist and a part-time writer with a particular interest in the gig economy. He writes about schooling, college life, and changing trends in education. When not writing, Joseph is hiking or playing chess.

Word Choice

What this handout is about.

This handout can help you revise your papers for word-level clarity, eliminate wordiness and avoid clichés, find the words that best express your ideas, and choose words that suit an academic audience.

Introduction

Writing is a series of choices. As you work on a paper, you choose your topic, your approach, your sources, and your thesis; when it’s time to write, you have to choose the words you will use to express your ideas and decide how you will arrange those words into sentences and paragraphs. As you revise your draft, you make more choices. You might ask yourself, “Is this really what I mean?” or “Will readers understand this?” or “Does this sound good?” Finding words that capture your meaning and convey that meaning to your readers is challenging. When your instructors write things like “awkward,” “vague,” or “wordy” on your draft, they are letting you know that they want you to work on word choice. This handout will explain some common issues related to word choice and give you strategies for choosing the best words as you revise your drafts.

As you read further into the handout, keep in mind that it can sometimes take more time to “save” words from your original sentence than to write a brand new sentence to convey the same meaning or idea. Don’t be too attached to what you’ve already written; if you are willing to start a sentence fresh, you may be able to choose words with greater clarity.

For tips on making more substantial revisions, take a look at our handouts on reorganizing drafts and revising drafts .

“Awkward,” “vague,” and “unclear” word choice

So: you write a paper that makes perfect sense to you, but it comes back with “awkward” scribbled throughout the margins. Why, you wonder, are instructors so fond of terms like “awkward”? Most instructors use terms like this to draw your attention to sentences they had trouble understanding and to encourage you to rewrite those sentences more clearly.

Difficulties with word choice aren’t the only cause of awkwardness, vagueness, or other problems with clarity. Sometimes a sentence is hard to follow because there is a grammatical problem with it or because of the syntax (the way the words and phrases are put together). Here’s an example: “Having finished with studying, the pizza was quickly eaten.” This sentence isn’t hard to understand because of the words I chose—everybody knows what studying, pizza, and eating are. The problem here is that readers will naturally assume that first bit of the sentence “(Having finished with studying”) goes with the next noun that follows it—which, in this case, is “the pizza”! It doesn’t make a lot of sense to imply that the pizza was studying. What I was actually trying to express was something more like this: “Having finished with studying, the students quickly ate the pizza.” If you have a sentence that has been marked “awkward,” “vague,” or “unclear,” try to think about it from a reader’s point of view—see if you can tell where it changes direction or leaves out important information.

Sometimes, though, problems with clarity are a matter of word choice. See if you recognize any of these issues:

- Misused words —the word doesn’t actually mean what the writer thinks it does. Example : Cree Indians were a monotonous culture until French and British settlers arrived. Revision: Cree Indians were a homogenous culture.

- Words with unwanted connotations or meanings. Example : I sprayed the ants in their private places. Revision: I sprayed the ants in their hiding places.

- Using a pronoun when readers can’t tell whom/what it refers to. Example : My cousin Jake hugged my brother Trey, even though he didn’t like him very much. Revision: My cousin Jake hugged my brother Trey, even though Jake doesn’t like Trey very much.

- Jargon or technical terms that make readers work unnecessarily hard. Maybe you need to use some of these words because they are important terms in your field, but don’t throw them in just to “sound smart.” Example : The dialectical interface between neo-Platonists and anti-disestablishment Catholics offers an algorithm for deontological thought. Revision : The dialogue between neo-Platonists and certain Catholic thinkers is a model for deontological thought.

- Loaded language. Sometimes we as writers know what we mean by a certain word, but we haven’t ever spelled that out for readers. We rely too heavily on that word, perhaps repeating it often, without clarifying what we are talking about. Example : Society teaches young girls that beauty is their most important quality. In order to prevent eating disorders and other health problems, we must change society. Revision : Contemporary American popular media, like magazines and movies, teach young girls that beauty is their most important quality. In order to prevent eating disorders and other health problems, we must change the images and role models girls are offered.

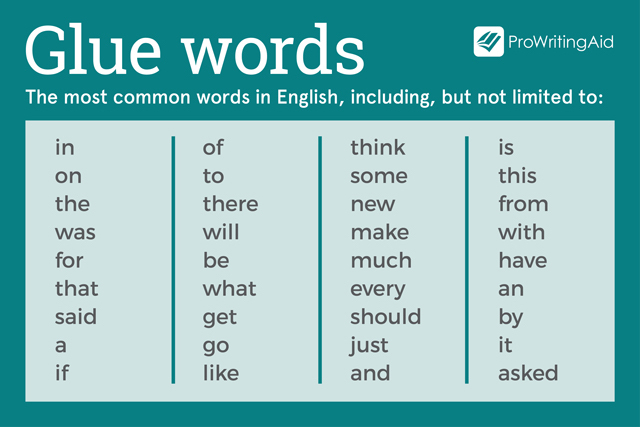

Sometimes the problem isn’t choosing exactly the right word to express an idea—it’s being “wordy,” or using words that your reader may regard as “extra” or inefficient. Take a look at the following list for some examples. On the left are some phrases that use three, four, or more words where fewer will do; on the right are some shorter substitutes:

Keep an eye out for wordy constructions in your writing and see if you can replace them with more concise words or phrases.

In academic writing, it’s a good idea to limit your use of clichés. Clichés are catchy little phrases so frequently used that they have become trite, corny, or annoying. They are problematic because their overuse has diminished their impact and because they require several words where just one would do.

The main way to avoid clichés is first to recognize them and then to create shorter, fresher equivalents. Ask yourself if there is one word that means the same thing as the cliché. If there isn’t, can you use two or three words to state the idea your own way? Below you will see five common clichés, with some alternatives to their right. As a challenge, see how many alternatives you can create for the final two examples.

Try these yourself:

Writing for an academic audience

When you choose words to express your ideas, you have to think not only about what makes sense and sounds best to you, but what will make sense and sound best to your readers. Thinking about your audience and their expectations will help you make decisions about word choice.

Some writers think that academic audiences expect them to “sound smart” by using big or technical words. But the most important goal of academic writing is not to sound smart—it is to communicate an argument or information clearly and convincingly. It is true that academic writing has a certain style of its own and that you, as a student, are beginning to learn to read and write in that style. You may find yourself using words and grammatical constructions that you didn’t use in your high school writing. The danger is that if you consciously set out to “sound smart” and use words or structures that are very unfamiliar to you, you may produce sentences that your readers can’t understand.

When writing for your professors, think simplicity. Using simple words does not indicate simple thoughts. In an academic argument paper, what makes the thesis and argument sophisticated are the connections presented in simple, clear language.

Keep in mind, though, that simple and clear doesn’t necessarily mean casual. Most instructors will not be pleased if your paper looks like an instant message or an email to a friend. It’s usually best to avoid slang and colloquialisms. Take a look at this example and ask yourself how a professor would probably respond to it if it were the thesis statement of a paper: “Moulin Rouge really bit because the singing sucked and the costume colors were nasty, KWIM?”

Selecting and using key terms

When writing academic papers, it is often helpful to find key terms and use them within your paper as well as in your thesis. This section comments on the crucial difference between repetition and redundancy of terms and works through an example of using key terms in a thesis statement.

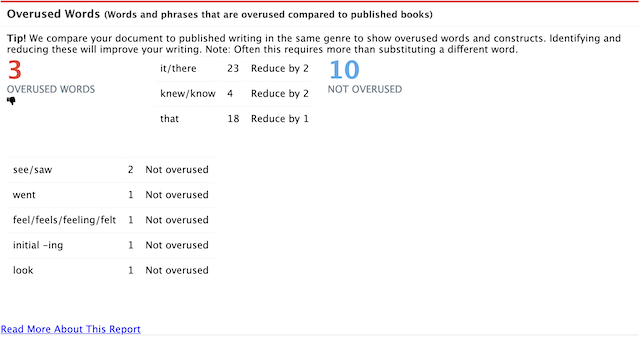

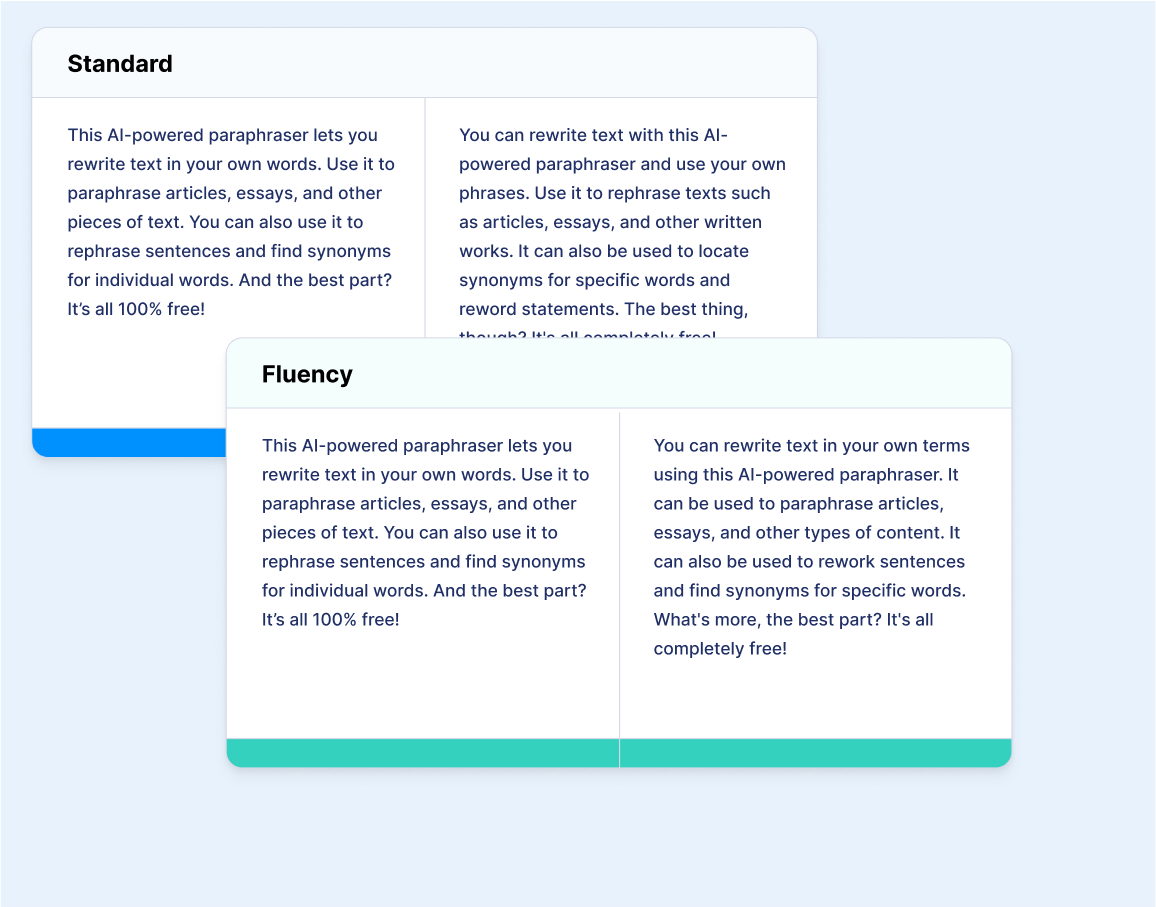

Repetition vs. redundancy

These two phenomena are not necessarily the same. Repetition can be a good thing. Sometimes we have to use our key terms several times within a paper, especially in topic sentences. Sometimes there is simply no substitute for the key terms, and selecting a weaker term as a synonym can do more harm than good. Repeating key terms emphasizes important points and signals to the reader that the argument is still being supported. This kind of repetition can give your paper cohesion and is done by conscious choice.

In contrast, if you find yourself frustrated, tiredly repeating the same nouns, verbs, or adjectives, or making the same point over and over, you are probably being redundant. In this case, you are swimming aimlessly around the same points because you have not decided what your argument really is or because you are truly fatigued and clarity escapes you. Refer to the “Strategies” section below for ideas on revising for redundancy.

Building clear thesis statements

Writing clear sentences is important throughout your writing. For the purposes of this handout, let’s focus on the thesis statement—one of the most important sentences in academic argument papers. You can apply these ideas to other sentences in your papers.

A common problem with writing good thesis statements is finding the words that best capture both the important elements and the significance of the essay’s argument. It is not always easy to condense several paragraphs or several pages into concise key terms that, when combined in one sentence, can effectively describe the argument.

However, taking the time to find the right words offers writers a significant edge. Concise and appropriate terms will help both the writer and the reader keep track of what the essay will show and how it will show it. Graders, in particular, like to see clearly stated thesis statements. (For more on thesis statements in general, please refer to our handout .)

Example : You’ve been assigned to write an essay that contrasts the river and shore scenes in Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. You work on it for several days, producing three versions of your thesis:

Version 1 : There are many important river and shore scenes in Huckleberry Finn.

Version 2 : The contrasting river and shore scenes in Huckleberry Finn suggest a return to nature.

Version 3 : Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

Let’s consider the word choice issues in these statements. In Version 1, the word “important”—like “interesting”—is both overused and vague; it suggests that the author has an opinion but gives very little indication about the framework of that opinion. As a result, your reader knows only that you’re going to talk about river and shore scenes, but not what you’re going to say. Version 2 is an improvement: the words “return to nature” give your reader a better idea where the paper is headed. On the other hand, they still do not know how this return to nature is crucial to your understanding of the novel.

Finally, you come up with Version 3, which is a stronger thesis because it offers a sophisticated argument and the key terms used to make this argument are clear. At least three key terms or concepts are evident: the contrast between river and shore scenes, a return to nature, and American democratic ideals.

By itself, a key term is merely a topic—an element of the argument but not the argument itself. The argument, then, becomes clear to the reader through the way in which you combine key terms.

Strategies for successful word choice

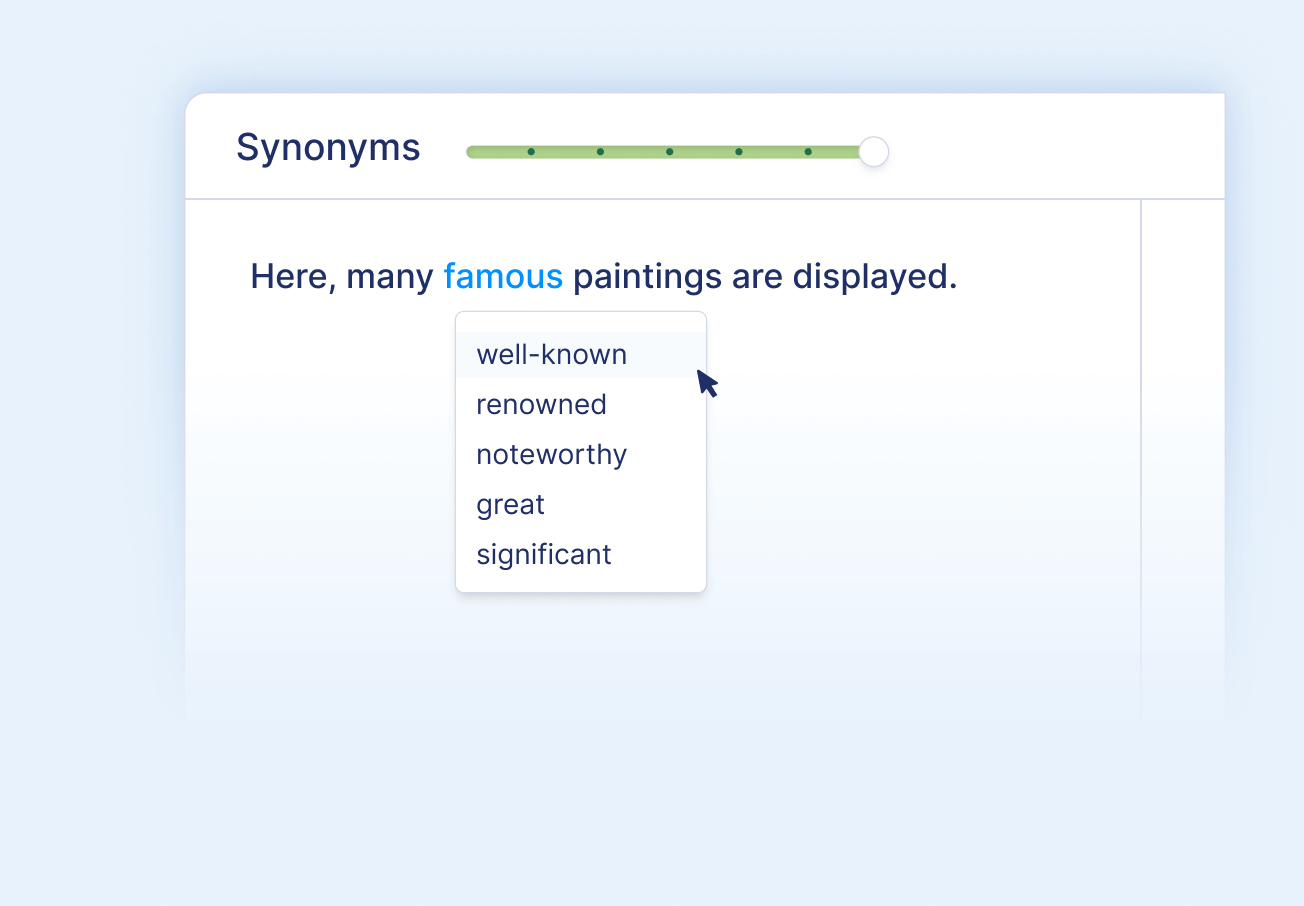

- Be careful when using words you are unfamiliar with. Look at how they are used in context and check their dictionary definitions.

- Be careful when using the thesaurus. Each word listed as a synonym for the word you’re looking up may have its own unique connotations or shades of meaning. Use a dictionary to be sure the synonym you are considering really fits what you are trying to say.

- Under the present conditions of our society, marriage practices generally demonstrate a high degree of homogeneity.

- In our culture, people tend to marry others who are like themselves. (Longman, p. 452)

- Before you revise for accurate and strong adjectives, make sure you are first using accurate and strong nouns and verbs. For example, if you were revising the sentence “This is a good book that tells about the Revolutionary War,” think about whether “book” and “tells” are as strong as they could be before you worry about “good.” (A stronger sentence might read “The novel describes the experiences of a soldier during the Revolutionary War.” “Novel” tells us what kind of book it is, and “describes” tells us more about how the book communicates information.)

- Try the slash/option technique, which is like brainstorming as you write. When you get stuck, write out two or more choices for a questionable word or a confusing sentence, e.g., “questionable/inaccurate/vague/inappropriate.” Pick the word that best indicates your meaning or combine different terms to say what you mean.

- Look for repetition. When you find it, decide if it is “good” repetition (using key terms that are crucial and helpful to meaning) or “bad” repetition (redundancy or laziness in reusing words).

- Write your thesis in five different ways. Make five different versions of your thesis sentence. Compose five sentences that express your argument. Try to come up with four alternatives to the thesis sentence you’ve already written. Find five possible ways to communicate your argument in one sentence to your reader. (We’ve just used this technique—which of the last five sentences do you prefer?)Whenever we write a sentence we make choices. Some are less obvious than others, so that it can often feel like we’ve written the sentence the only way we know how. By writing out five different versions of your thesis, you can begin to see your range of choices. The final version may be a combination of phrasings and words from all five versions, or the one version that says it best. By literally spelling out some possibilities for yourself, you will be able to make better decisions.

- Read your paper out loud and at… a… slow… pace. You can do this alone or with a friend, roommate, TA, etc. When read out loud, your written words should make sense to both you and other listeners. If a sentence seems confusing, rewrite it to make the meaning clear.

- Instead of reading the paper itself, put it down and just talk through your argument as concisely as you can. If your listener quickly and easily comprehends your essay’s main point and significance, you should then make sure that your written words are as clear as your oral presentation was. If, on the other hand, your listener keeps asking for clarification, you will need to work on finding the right terms for your essay. If you do this in exchange with a friend or classmate, rest assured that whether you are the talker or the listener, your articulation skills will develop.

- Have someone not familiar with the issue read the paper and point out words or sentences they find confusing. Do not brush off this reader’s confusion by assuming they simply doesn’t know enough about the topic. Instead, rewrite the sentences so that your “outsider” reader can follow along at all times.

- Check out the Writing Center’s handouts on style , passive voice , and proofreading for more tips.

Questions to ask yourself

- Am I sure what each word I use really means? Am I positive, or should I look it up?

- Have I found the best word or just settled for the most obvious, or the easiest, one?

- Am I trying too hard to impress my reader?

- What’s the easiest way to write this sentence? (Sometimes it helps to answer this question by trying it out loud. How would you say it to someone?)

- What are the key terms of my argument?

- Can I outline out my argument using only these key terms? What others do I need? Which do I not need?

- Have I created my own terms, or have I simply borrowed what looked like key ones from the assignment? If I’ve borrowed the terms, can I find better ones in my own vocabulary, the texts, my notes, the dictionary, or the thesaurus to make myself clearer?

- Are my key terms too specific? (Do they cover the entire range of my argument?) Can I think of specific examples from my sources that fall under the key term?

- Are my key terms too vague? (Do they cover more than the range of my argument?)

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Cook, Claire Kehrwald. 1985. Line by Line: How to Improve Your Own Writing . Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Grossman, Ellie. 1997. The Grammatically Correct Handbook: A Lively and Unorthodox Review of Common English for the Linguistically Challenged . New York: Hyperion.

Houghton Mifflin. 1996. The American Heritage Book of English Usage: A Practical and Authoritative Guide to Contemporary English . Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

O’Conner, Patricia. 2010. Woe Is I: The Grammarphobe’s Guide to Better English in Plain English , 3rd ed. New York: Penguin Publishing Group.

Tarshis, Barry. 1998. How to Be Your Own Best Editor: The Toolkit for Everyone Who Writes . New York: Three Rivers Press.

Williams, Joseph, and Joseph Bizup. 2017. Style: Lessons in Clarity and Grace , 12th ed. Boston: Pearson.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Academic Phrasebank

Defining terms.

- GENERAL LANGUAGE FUNCTIONS

- Being cautious

- Being critical

- Classifying and listing

- Compare and contrast

- Describing trends

- Describing quantities

- Explaining causality

- Giving examples

- Signalling transition

- Writing about the past

In academic work students are often expected to give definitions of key words and phrases in order to demonstrate to their tutors that they understand these terms clearly. More generally, however, academic writers define terms so that their readers understand exactly what is meant when certain key terms are used. When important words are not clearly understood misinterpretation may result. In fact, many disagreements (academic, legal, diplomatic, personal) arise as a result of different interpretations of the same term. In academic writing, teachers and their students often have to explore these differing interpretations before moving on to study a topic.

Introductory phrases

The term ‘X’ was first used by … The term ‘X’ can be traced back to … Previous studies mostly defined X as … The term ‘X’ was introduced by Smith in her … Historically, the term ‘X’ has been used to describe … It is necessary here to clarify exactly what is meant by … This shows a need to be explicit about exactly what is meant by the word ‘X’.

Simple three-part definitions

General meanings or application of meanings.

X can broadly be defined as … X can be loosely described as … X can be defined as … It encompasses … In the literature, the term tends to be used to refer to … In broad terms, X can be defined as any stimulus that is … Whereas X refers to the operations of …, Y refers to the … The broad use of the term ‘X’ is sometimes equated with … The term ‘disease’ refers to a biological event characterised by … Defined as …, X is now considered a worldwide problem and is associated with …

Indicating varying definitions

The definition of X has evolved. There are multiple definitions of X. Several definitions of X have been proposed. In the field of X, various definitions of X are found. The term ‘X’ embodies a multitude of concepts which … This term has two overlapping, even slightly confusing meanings. Widely varying definitions of X have emerged (Smith and Jones, 1999). Despite its common usage, X is used in different disciplines to mean different things. Since the definition of X varies among researchers, it is important to clarify how the term is …

Indicating difficulties in defining a term

X is a contested term. X is a rather nebulous term … X is challenging to define because … A precise definition of X has proved elusive. A generally accepted definition of X is lacking. Unfortunately, X remains a poorly defined term. There is no agreed definition on what constitutes … There is little consensus about what X actually means. There is a degree of uncertainty around the terminology in … These terms are often used interchangeably and without precision. Numerous terms are used to describe X, the most common of which are …. The definition of X varies in the literature and there is terminological confusion. Smith (2001) identified four abilities that might be subsumed under the term ‘X’: a) … ‘X’ is a term frequently used in the literature, but to date there is no consensus about … X is a commonly-used notion in psychology and yet it is a concept difficult to define precisely. Although differences of opinion still exist, there appears to be some agreement that X refers to …

Specifying terms that are used in an essay or thesis

The term ‘X’ is used here to refer to … In the present study, X is defined as … The term ‘X’ will be used solely when referring to … In this essay, the term ‘X’ will be used in its broadest sense to refer to all … In this paper, the term that will be used to describe this phenomenon is ‘X’. In this dissertation, the terms ‘X’ and ‘Y’ are used interchangeably to mean … Throughout this thesis, the term ‘X’ is used to refer to informal systems as well as … While a variety of definitions of the term ‘X’ have been suggested, this paper will use the definition first suggested by Smith (1968) who saw it as …

Referring to people’s definitions: author prominent

For Smith (2001), X means … Smith (2001) uses the term ‘X’ to refer to … Smith (1954) was apparently the first to use the term … In 1987, psychologist John Smith popularized the term ‘X’ to describe … According to a definition provided by Smith (2001:23), X is ‘the maximally … This definition is close to those of Smith (2012) and Jones (2013) who define X as … Smith, has shown that, as late as 1920, Jones was using the term ‘X’ to refer to particular … One of the first people to define nursing was Florence Nightingale (1860), who wrote: ‘… …’ Chomsky writes that a grammar is a ‘device of some sort for producing the ….’ (1957, p.11). Aristotle defines the imagination as ‘the movement which results upon an actual sensation.’ Smith et al . (2002) have provided a new definition of health: ‘health is a state of being with …

Referring to people’s definitions: author non-prominent

X is defined by Smith (2003: 119) as ‘… …’ The term ‘X’ is used by Smith (2001) to refer to … X is, for Smith (2012), the situation which occurs when … A further definition of X is given by Smith (1982) who describes … The term ‘X’ is used by Aristotle in four overlapping senses. First, it is the underlying … X is the degree to which an assessment process or device measures … (Smith et al ., 1986).

Commenting on a definition

+44 (0) 161 306 6000

The University of Manchester Oxford Rd Manchester M13 9PL UK

Connect With Us

The University of Manchester

Words To Use In Essays: Amplifying Your Academic Writing

Use this comprehensive list of words to use in essays to elevate your writing. Make an impression and score higher grades with this guide!

Words play a fundamental role in the domain of essay writing, as they have the power to shape ideas, influence readers, and convey messages with precision and impact. Choosing the right words to use in essays is not merely a matter of filling pages, but rather a deliberate process aimed at enhancing the quality of the writing and effectively communicating complex ideas. In this article, we will explore the importance of selecting appropriate words for essays and provide valuable insights into the types of words that can elevate the essay to new heights.

Words To Use In Essays

Using a wide range of words can make your essay stronger and more impressive. With the incorporation of carefully chosen words that communicate complex ideas with precision and eloquence, the writer can elevate the quality of their essay and captivate readers.

This list serves as an introduction to a range of impactful words that can be integrated into writing, enabling the writer to express thoughts with depth and clarity.

Significantly

Furthermore

Nonetheless

Nevertheless

Consequently

Accordingly

Subsequently

In contrast

Alternatively

Implications

Substantially

Transition Words And Phrases

Transition words and phrases are essential linguistic tools that connect ideas, sentences, and paragraphs within a text. They work like bridges, facilitating the transitions between different parts of an essay or any other written work. These transitional elements conduct the flow and coherence of the writing, making it easier for readers to follow the author’s train of thought.

Here are some examples of common transition words and phrases:

Furthermore: Additionally; moreover.

However: Nevertheless; on the other hand.

In contrast: On the contrary; conversely.

Therefore: Consequently; as a result.

Similarly: Likewise; in the same way.

Moreover: Furthermore; besides.

In addition: Additionally; also.

Nonetheless: Nevertheless; regardless.

Nevertheless: However; even so.

On the other hand: Conversely; in contrast.

These are just a few examples of the many transition words and phrases available. They help create coherence, improve the organization of ideas, and guide readers through the logical progression of the text. When used effectively, transition words and phrases can significantly guide clarity for writing.

Strong Verbs For Academic Writing

Strong verbs are an essential component of academic writing as they add precision, clarity, and impact to sentences. They convey actions, intentions, and outcomes in a more powerful and concise manner. Here are some examples of strong verbs commonly used in academic writing:

Analyze: Examine in detail to understand the components or structure.

Critique: Assess or evaluate the strengths and weaknesses.

Demonstrate: Show the evidence to support a claim or argument.

Illuminate: Clarify or make something clearer.

Explicate: Explain in detail a thorough interpretation.

Synthesize: Combine or integrate information to create a new understanding.

Propose: Put forward or suggest a theory, idea, or solution.

Refute: Disprove or argue against a claim or viewpoint.

Validate: Confirm or prove the accuracy or validity of something.

Advocate: Support or argue in favor of a particular position or viewpoint.

Adjectives And Adverbs For Academic Essays

Useful adjectives and adverbs are valuable tools in academic writing as they enhance the description, precision, and depth of arguments and analysis. They provide specific details, emphasize key points, and add nuance to writing. Here are some examples of useful adjectives and adverbs commonly used in academic essays:

Comprehensive: Covering all aspects or elements; thorough.

Crucial: Extremely important or essential.

Prominent: Well-known or widely recognized; notable.

Substantial: Considerable in size, extent, or importance.

Valid: Well-founded or logically sound; acceptable or authoritative.

Effectively: In a manner that produces the desired result or outcome.

Significantly: To a considerable extent or degree; notably.

Consequently: As a result or effect of something.

Precisely: Exactly or accurately; with great attention to detail.

Critically: In a careful and analytical manner; with careful evaluation or assessment.

Words To Use In The Essay Introduction

The words used in the essay introduction play a crucial role in capturing the reader’s attention and setting the tone for the rest of the essay. They should be engaging, informative, and persuasive. Here are some examples of words that can be effectively used in the essay introduction:

Intriguing: A word that sparks curiosity and captures the reader’s interest from the beginning.

Compelling: Conveys the idea that the topic is interesting and worth exploring further.

Provocative: Creates a sense of controversy or thought-provoking ideas.

Insightful: Suggests that the essay will produce valuable and thought-provoking insights.

Startling: Indicates that the essay will present surprising or unexpected information or perspectives.

Relevant: Emphasizes the significance of the topic and its connection to broader issues or current events.

Timely: Indicates that the essay addresses a subject of current relevance or importance.

Thoughtful: Implies that the essay will offer well-considered and carefully developed arguments.

Persuasive: Suggests that the essay will present compelling arguments to convince the reader.

Captivating: Indicates that the essay will hold the reader’s attention and be engaging throughout.

Words To Use In The Body Of The Essay

The words used in the body of the essay are essential for effectively conveying ideas, providing evidence, and developing arguments. They should be clear, precise, and demonstrate a strong command of the subject matter. Here are some examples of words that can be used in the body of the essay:

Evidence: When presenting supporting information or data, words such as “data,” “research,” “studies,” “findings,” “examples,” or “statistics” can be used to strengthen arguments.

Analysis: To discuss and interpret the evidence, words like “analyze,” “examine,” “explore,” “interpret,” or “assess” can be employed to demonstrate a critical evaluation of the topic.

Comparison: When drawing comparisons or making contrasts, words like “similarly,” “likewise,” “in contrast,” “on the other hand,” or “conversely” can be used to highlight similarities or differences.

Cause and effect: To explain the relationship between causes and consequences, words such as “because,” “due to,” “leads to,” “results in,” or “causes” can be utilized.

Sequence: When discussing a series of events or steps, words like “first,” “next,” “then,” “finally,” “subsequently,” or “consequently” can be used to indicate the order or progression.

Emphasis: To emphasize a particular point or idea, words such as “notably,” “significantly,” “crucially,” “importantly,” or “remarkably” can be employed.

Clarification: When providing further clarification or elaboration, words like “specifically,” “in other words,” “for instance,” “to illustrate,” or “to clarify” can be used.

Integration: To show the relationship between different ideas or concepts, words such as “moreover,” “furthermore,” “additionally,” “likewise,” or “similarly” can be utilized.

Conclusion: When summarizing or drawing conclusions, words like “in conclusion,” “to summarize,” “overall,” “in summary,” or “to conclude” can be employed to wrap up ideas.

Remember to use these words appropriately and contextually, ensuring they strengthen the coherence and flow of arguments. They should serve as effective transitions and connectors between ideas, enhancing the overall clarity and persuasiveness of the essay.

Words To Use In Essay Conclusion

The words used in the essay conclusion are crucial for effectively summarizing the main points, reinforcing arguments, and leaving a lasting impression on the reader. They should bring a sense of closure to the essay while highlighting the significance of ideas. Here are some examples of words that can be used in the essay conclusion:

Summary: To summarize the main points, these words can be used “in summary,” “to sum up,” “in conclusion,” “to recap,” or “overall.”

Reinforcement: To reinforce arguments and emphasize their importance, words such as “crucial,” “essential,” “significant,” “noteworthy,” or “compelling” can be employed.

Implication: To discuss the broader implications of ideas or findings, words like “consequently,” “therefore,” “thus,” “hence,” or “as a result” can be utilized.

Call to action: If applicable, words that encourage further action or reflection can be used, such as “we must,” “it is essential to,” “let us consider,” or “we should.”

Future perspective: To discuss future possibilities or developments related to the topic, words like “potential,” “future research,” “emerging trends,” or “further investigation” can be employed.

Reflection: To reflect on the significance or impact of arguments, words such as “profound,” “notable,” “thought-provoking,” “transformative,” or “perspective-shifting” can be used.

Final thought: To leave a lasting impression, words or phrases that summarize the main idea or evoke a sense of thoughtfulness can be used, such as “food for thought,” “in light of this,” “to ponder,” or “to consider.”

How To Improve Essay Writing Vocabulary

Improving essay writing vocabulary is essential for effectively expressing ideas, demonstrating a strong command of the language, and engaging readers. Here are some strategies to enhance the essay writing vocabulary:

- Read extensively: Reading a wide range of materials, such as books, articles, and essays, can give various writing styles, topics, and vocabulary. Pay attention to new words and their usage, and try incorporating them into the writing.

- Use a dictionary and thesaurus: Look up unfamiliar words in a dictionary to understand their meanings and usage. Additionally, utilize a thesaurus to find synonyms and antonyms to expand word choices and avoid repetition.

- Create a word bank: To create a word bank, read extensively, write down unfamiliar or interesting words, and explore their meanings and usage. Organize them by categories or themes for easy reference, and practice incorporating them into writing to expand the vocabulary.

- Contextualize vocabulary: Simply memorizing new words won’t be sufficient; it’s crucial to understand their proper usage and context. Pay attention to how words are used in different contexts, sentence structures, and rhetorical devices.

How To Add Additional Information To Support A Point

When writing an essay and wanting to add additional information to support a point, you can use various transitional words and phrases. Here are some examples:

Furthermore: Add more information or evidence to support the previous point.

Additionally: Indicates an additional supporting idea or evidence.

Moreover: Emphasizes the importance or significance of the added information.

In addition: Signals the inclusion of another supporting detail.

Furthermore, it is important to note: Introduces an additional aspect or consideration related to the topic.

Not only that, but also: Highlights an additional point that strengthens the argument.

Equally important: Emphasizes the equal significance of the added information.

Another key point: Introduces another important supporting idea.

It is worth noting: Draws attention to a noteworthy detail that supports the point being made.

Additionally, it is essential to consider: Indicates the need to consider another aspect or perspective.

Using these transitional words and phrases will help you seamlessly integrate additional information into your essay, enhancing the clarity and persuasiveness of your arguments.

Words And Phrases That Demonstrate Contrast

When crafting an essay, it is crucial to effectively showcase contrast, enabling the presentation of opposing ideas or the highlighting of differences between concepts. The adept use of suitable words and phrases allows for the clear communication of contrast, bolstering the strength of arguments. Consider the following examples of commonly employed words and phrases to illustrate the contrast in essays:

However: e.g., “The experiment yielded promising results; however, further analysis is needed to draw conclusive findings.”

On the other hand: e.g., “Some argue for stricter gun control laws, while others, on the other hand, advocate for individual rights to bear arms.”

Conversely: e.g., “While the study suggests a positive correlation between exercise and weight loss, conversely, other research indicates that diet plays a more significant role.”

Nevertheless: e.g., “The data shows a decline in crime rates; nevertheless, public safety remains a concern for many citizens.”

In contrast: e.g., “The economic policies of Country A focus on free-market principles. In contrast, Country B implements more interventionist measures.”

Despite: e.g., “Despite the initial setbacks, the team persevered and ultimately achieved success.”

Although: e.g., “Although the participants had varying levels of experience, they all completed the task successfully.”

While: e.g., “While some argue for stricter regulations, others contend that personal responsibility should prevail.”

Words To Use For Giving Examples

When writing an essay and providing examples to illustrate your points, you can use a variety of words and phrases to introduce those examples. Here are some examples:

For instance: Introduces a specific example to support or illustrate your point.

For example: Give an example to clarify or demonstrate your argument.

Such as: Indicates that you are providing a specific example or examples.

To illustrate: Signals that you are using an example to explain or emphasize your point.

One example is: Introduces a specific instance that exemplifies your argument.

In particular: Highlights a specific example that is especially relevant to your point.

As an illustration: Introduces an example that serves as a visual or concrete representation of your point.

A case in point: Highlights a specific example that serves as evidence or proof of your argument.

To demonstrate: Indicates that you are providing an example to show or prove your point.

To exemplify: Signals that you are using an example to illustrate or clarify your argument.

Using these words and phrases will help you effectively incorporate examples into your essay, making your arguments more persuasive and relatable. Remember to give clear and concise examples that directly support your main points.

Words To Signifying Importance

When writing an essay and wanting to signify the importance of a particular point or idea, you can use various words and phrases to convey this emphasis. Here are some examples:

Crucially: Indicates that the point being made is of critical importance.

Significantly: Highlights the importance or significance of the idea or information.

Importantly: Draws attention to the crucial nature of the point being discussed.

Notably: Emphasizes that the information or idea is particularly worthy of attention.

It is vital to note: Indicates that the point being made is essential and should be acknowledged.

It should be emphasized: Draws attention to the need to give special importance or focus to the point being made.

A key consideration is: Highlight that the particular idea or information is a central aspect of the discussion.

It is critical to recognize: Emphasizes that the understanding or acknowledgment of the point is crucial.

Using these words and phrases will help you convey the importance and significance of specific points or ideas in your essay, ensuring that readers recognize their significance and impact on the overall argument.

Exclusive Scientific Content, Created By Scientists

Mind the Graph platform provides scientists with exclusive scientific content that is created by scientists themselves. This unique feature ensures that the platform offers high-quality and reliable information tailored specifically for the scientific community. The platform serves as a valuable resource for researchers, offering a wide range of visual tools and templates that enable scientists to create impactful and visually engaging scientific illustrations and graphics for their publications, presentations, and educational materials.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Exclusive high quality content about effective visual communication in science.

Content tags

Places on our 2024 summer school are filling fast. Don’t miss out. Enrol now to avoid disappointment

- 40 Useful Words and Phrases for Top-Notch Essays

To be truly brilliant, an essay needs to utilise the right language. You could make a great point, but if it’s not intelligently articulated, you almost needn’t have bothered.

Developing the language skills to build an argument and to write persuasively is crucial if you’re to write outstanding essays every time. In this article, we’re going to equip you with the words and phrases you need to write a top-notch essay, along with examples of how to utilise them.

It’s by no means an exhaustive list, and there will often be other ways of using the words and phrases we describe that we won’t have room to include, but there should be more than enough below to help you make an instant improvement to your essay-writing skills.

If you’re interested in developing your language and persuasive skills, Oxford Royale offers summer courses at its Oxford Summer School , Cambridge Summer School , London Summer School , San Francisco Summer School and Yale Summer School . You can study courses to learn english , prepare for careers in law , medicine , business , engineering and leadership.

General explaining

Let’s start by looking at language for general explanations of complex points.

1. In order to

Usage: “In order to” can be used to introduce an explanation for the purpose of an argument. Example: “In order to understand X, we need first to understand Y.”

2. In other words

Usage: Use “in other words” when you want to express something in a different way (more simply), to make it easier to understand, or to emphasise or expand on a point. Example: “Frogs are amphibians. In other words, they live on the land and in the water.”

3. To put it another way

Usage: This phrase is another way of saying “in other words”, and can be used in particularly complex points, when you feel that an alternative way of wording a problem may help the reader achieve a better understanding of its significance. Example: “Plants rely on photosynthesis. To put it another way, they will die without the sun.”

4. That is to say

Usage: “That is” and “that is to say” can be used to add further detail to your explanation, or to be more precise. Example: “Whales are mammals. That is to say, they must breathe air.”

5. To that end

Usage: Use “to that end” or “to this end” in a similar way to “in order to” or “so”. Example: “Zoologists have long sought to understand how animals communicate with each other. To that end, a new study has been launched that looks at elephant sounds and their possible meanings.”

Adding additional information to support a point

Students often make the mistake of using synonyms of “and” each time they want to add further information in support of a point they’re making, or to build an argument . Here are some cleverer ways of doing this.

6. Moreover

Usage: Employ “moreover” at the start of a sentence to add extra information in support of a point you’re making. Example: “Moreover, the results of a recent piece of research provide compelling evidence in support of…”

7. Furthermore

Usage:This is also generally used at the start of a sentence, to add extra information. Example: “Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that…”

8. What’s more

Usage: This is used in the same way as “moreover” and “furthermore”. Example: “What’s more, this isn’t the only evidence that supports this hypothesis.”

9. Likewise

Usage: Use “likewise” when you want to talk about something that agrees with what you’ve just mentioned. Example: “Scholar A believes X. Likewise, Scholar B argues compellingly in favour of this point of view.”

10. Similarly

Usage: Use “similarly” in the same way as “likewise”. Example: “Audiences at the time reacted with shock to Beethoven’s new work, because it was very different to what they were used to. Similarly, we have a tendency to react with surprise to the unfamiliar.”

11. Another key thing to remember

Usage: Use the phrase “another key point to remember” or “another key fact to remember” to introduce additional facts without using the word “also”. Example: “As a Romantic, Blake was a proponent of a closer relationship between humans and nature. Another key point to remember is that Blake was writing during the Industrial Revolution, which had a major impact on the world around him.”

12. As well as

Usage: Use “as well as” instead of “also” or “and”. Example: “Scholar A argued that this was due to X, as well as Y.”

13. Not only… but also

Usage: This wording is used to add an extra piece of information, often something that’s in some way more surprising or unexpected than the first piece of information. Example: “Not only did Edmund Hillary have the honour of being the first to reach the summit of Everest, but he was also appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire.”

14. Coupled with

Usage: Used when considering two or more arguments at a time. Example: “Coupled with the literary evidence, the statistics paint a compelling view of…”

15. Firstly, secondly, thirdly…

Usage: This can be used to structure an argument, presenting facts clearly one after the other. Example: “There are many points in support of this view. Firstly, X. Secondly, Y. And thirdly, Z.

16. Not to mention/to say nothing of

Usage: “Not to mention” and “to say nothing of” can be used to add extra information with a bit of emphasis. Example: “The war caused unprecedented suffering to millions of people, not to mention its impact on the country’s economy.”

Words and phrases for demonstrating contrast

When you’re developing an argument, you will often need to present contrasting or opposing opinions or evidence – “it could show this, but it could also show this”, or “X says this, but Y disagrees”. This section covers words you can use instead of the “but” in these examples, to make your writing sound more intelligent and interesting.

17. However

Usage: Use “however” to introduce a point that disagrees with what you’ve just said. Example: “Scholar A thinks this. However, Scholar B reached a different conclusion.”

18. On the other hand

Usage: Usage of this phrase includes introducing a contrasting interpretation of the same piece of evidence, a different piece of evidence that suggests something else, or an opposing opinion. Example: “The historical evidence appears to suggest a clear-cut situation. On the other hand, the archaeological evidence presents a somewhat less straightforward picture of what happened that day.”

19. Having said that

Usage: Used in a similar manner to “on the other hand” or “but”. Example: “The historians are unanimous in telling us X, an agreement that suggests that this version of events must be an accurate account. Having said that, the archaeology tells a different story.”

20. By contrast/in comparison

Usage: Use “by contrast” or “in comparison” when you’re comparing and contrasting pieces of evidence. Example: “Scholar A’s opinion, then, is based on insufficient evidence. By contrast, Scholar B’s opinion seems more plausible.”

21. Then again

Usage: Use this to cast doubt on an assertion. Example: “Writer A asserts that this was the reason for what happened. Then again, it’s possible that he was being paid to say this.”

22. That said

Usage: This is used in the same way as “then again”. Example: “The evidence ostensibly appears to point to this conclusion. That said, much of the evidence is unreliable at best.”

Usage: Use this when you want to introduce a contrasting idea. Example: “Much of scholarship has focused on this evidence. Yet not everyone agrees that this is the most important aspect of the situation.”

Adding a proviso or acknowledging reservations

Sometimes, you may need to acknowledge a shortfalling in a piece of evidence, or add a proviso. Here are some ways of doing so.

24. Despite this

Usage: Use “despite this” or “in spite of this” when you want to outline a point that stands regardless of a shortfalling in the evidence. Example: “The sample size was small, but the results were important despite this.”

25. With this in mind

Usage: Use this when you want your reader to consider a point in the knowledge of something else. Example: “We’ve seen that the methods used in the 19th century study did not always live up to the rigorous standards expected in scientific research today, which makes it difficult to draw definite conclusions. With this in mind, let’s look at a more recent study to see how the results compare.”

26. Provided that

Usage: This means “on condition that”. You can also say “providing that” or just “providing” to mean the same thing. Example: “We may use this as evidence to support our argument, provided that we bear in mind the limitations of the methods used to obtain it.”

27. In view of/in light of

Usage: These phrases are used when something has shed light on something else. Example: “In light of the evidence from the 2013 study, we have a better understanding of…”

28. Nonetheless

Usage: This is similar to “despite this”. Example: “The study had its limitations, but it was nonetheless groundbreaking for its day.”

29. Nevertheless

Usage: This is the same as “nonetheless”. Example: “The study was flawed, but it was important nevertheless.”

30. Notwithstanding

Usage: This is another way of saying “nonetheless”. Example: “Notwithstanding the limitations of the methodology used, it was an important study in the development of how we view the workings of the human mind.”

Giving examples

Good essays always back up points with examples, but it’s going to get boring if you use the expression “for example” every time. Here are a couple of other ways of saying the same thing.

31. For instance

Example: “Some birds migrate to avoid harsher winter climates. Swallows, for instance, leave the UK in early winter and fly south…”

32. To give an illustration

Example: “To give an illustration of what I mean, let’s look at the case of…”

Signifying importance

When you want to demonstrate that a point is particularly important, there are several ways of highlighting it as such.

33. Significantly

Usage: Used to introduce a point that is loaded with meaning that might not be immediately apparent. Example: “Significantly, Tacitus omits to tell us the kind of gossip prevalent in Suetonius’ accounts of the same period.”

34. Notably

Usage: This can be used to mean “significantly” (as above), and it can also be used interchangeably with “in particular” (the example below demonstrates the first of these ways of using it). Example: “Actual figures are notably absent from Scholar A’s analysis.”

35. Importantly

Usage: Use “importantly” interchangeably with “significantly”. Example: “Importantly, Scholar A was being employed by X when he wrote this work, and was presumably therefore under pressure to portray the situation more favourably than he perhaps might otherwise have done.”

Summarising

You’ve almost made it to the end of the essay, but your work isn’t over yet. You need to end by wrapping up everything you’ve talked about, showing that you’ve considered the arguments on both sides and reached the most likely conclusion. Here are some words and phrases to help you.

36. In conclusion

Usage: Typically used to introduce the concluding paragraph or sentence of an essay, summarising what you’ve discussed in a broad overview. Example: “In conclusion, the evidence points almost exclusively to Argument A.”

37. Above all

Usage: Used to signify what you believe to be the most significant point, and the main takeaway from the essay. Example: “Above all, it seems pertinent to remember that…”

38. Persuasive

Usage: This is a useful word to use when summarising which argument you find most convincing. Example: “Scholar A’s point – that Constanze Mozart was motivated by financial gain – seems to me to be the most persuasive argument for her actions following Mozart’s death.”

39. Compelling

Usage: Use in the same way as “persuasive” above. Example: “The most compelling argument is presented by Scholar A.”

40. All things considered

Usage: This means “taking everything into account”. Example: “All things considered, it seems reasonable to assume that…”

How many of these words and phrases will you get into your next essay? And are any of your favourite essay terms missing from our list? Let us know in the comments below, or get in touch here to find out more about courses that can help you with your essays.

At Oxford Royale Academy, we offer a number of summer school courses for young people who are keen to improve their essay writing skills. Click here to apply for one of our courses today, including law , business , medicine and engineering .

Comments are closed.

How-To Geek

How to search for text in word.

Searching for text in your Microsoft Word document is extremely easy to do, especially with the built-in advanced search options.

Quick Links

Finding text in a word doc, setting advanced search features.

Microsoft Word provides a feature that allows you to search for text within a document. You can also use advanced settings to make your search more specific, such as case matching or ignoring punctuation. Here’s how to use it.

To search for text in Word, you’ll need to access the “Navigation” pane. You can do so by selecting “Find” in the “Editing” group of the “Home” tab.

An alternative method to accessing this pane is by using the Ctrl + F shortcut key on Windows or Command + F on Mac.

Related: How to Search for Text Inside of Any File Using Windows Search

With the “Navigation” pane open, enter the text you want to find. The number of instances that text appears throughout the document will be displayed.

You can navigate through the search results by selecting the up and down arrows located beneath the search box or by clicking directly on the result snippet in the navigation pane.

The caveat with the basic search function is that it doesn’t take into account many things such, as the case of the letters in the text. This is a problem if you’re searching a document that contains a lot of content, such as a book or thesis.

You can fine-tune these details by going to the “Editing” group of the “Home” tab, selecting the arrow next to “Find,” and selecting “Advanced Find” from the drop-down list.

The “ Find and Replace ” window will appear. Select “More.”

In the “Search Options” group, check the box next to the options you want to enable.

Now, the next time you search for text in Word, the search will work with the selected advanced options.

You can search for words or sets of words within a specific article. For example, maybe you want to find every instance of the word "twin" in an article you are reading. To search for words or phrases within the article you are viewing, do the following:

- Hold the Ctrl keyboard key and press the F keyboard key (Ctrl+F) or right-click (click the right mouse button) somewhere on the article and select Find (in this article) . This will bring up a text box to type search words into (see picture below).

- Small arrows buttons next to the find text box allow you to go back and forth between each instance of the word or phrase.

- When you are done searching, press Ctrl+F on the keyboard or right-click on the article and select Find (in this article) . This will remove the find text box and restore the default buttons.

- Write great papers Article

- Captivate the class Article

- Stage your story Article

Write great papers

Write great papers with microsoft word.

You may already use Microsoft Word to write papers, but you can also use for many other tasks, such as collecting research, co-writing with other students, recording notes on-the-fly, and even building a better bibliography!

Explore new ways to use Microsoft Word below.

Getting started

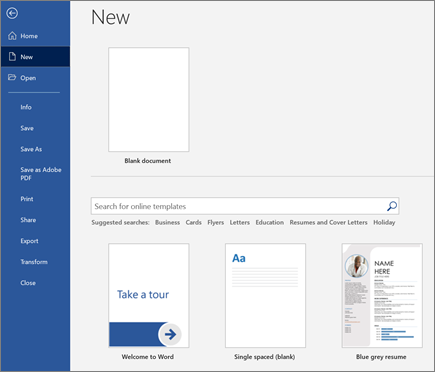

Let’s get started by opening Microsoft Word and choosing a template to create a new document. You can either:

Select Blank document to create a document from scratch.

Select a structured template.

Select Take a tour for Word tips.

Next, let’s look at creating and formatting copy. You can do so by clicking onto the page and beginning to type your content. The status bar at the bottom of the document shows your current page number and how many words you've typed, in case you’re trying to stay maintain a specific word count.

To format text and change how it looks, select the text and select an option on the Home tab: Bold, Italic, Bullets, Numbering , etc.

To add pictures, shapes, or other media, simply navigate to the Insert tab, then select any of the options to add media to your document.

Word automatically saves your content as you work, so you don’t have to stress about losing your progress if you forget to press Save .

Here are some of the advanced tools you can try out while using Microsoft Word.

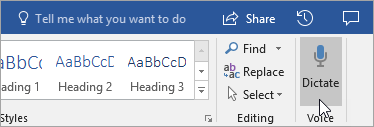

Type with your voice

Have you ever wanted to speak, not write, your ideas? Believe it or not, there’s a button for that! All you have to do is navigate to the Home tab, select the Dictate button, and start talking to “type” with your voice. You’ll know Dictate is listening when the red recording icon appears.

Tips for using Dictate

Speak clearly and conversationally.

Add punctuation by pausing or saying the name of the punctuation mark.

If you make a mistake, all you have to do is go back and re-type your text.

Finding and citing sources

Get a head start on collecting sources and ideas for a big paper by searching key words in Researcher in the References tab of your document.

Researcher uses Bing to search the web and deliver high-quality research sources to the side of your page. Search for people, places, or ideas and then sort by journal articles and websites. Add a source to your page by selecting the plus sign.

As you write, Researcher saves a record of your searches. Just select My Research to see the complete list.

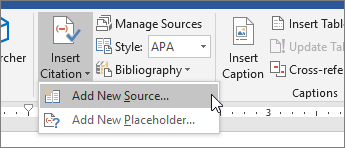

Keep track of all your sources by using Word's built-in bibliography maker. Simply navigate to the References tab.

First, choose the style you want your citations to be in. In this example, we’ve selected APA style.

Select Insert Citation and Add New Source .

In the next window, choose what kind of work you’re citing—an article, book, etc.—and fill in the required details. Then select OK to cite your source.

Keep writing. At the ends of sentences that need sources, select Insert Citation to keep adding new sources, or pick one you already entered from the list.

As you write, Word will keep track of all the citations you’ve entered. When you’re finished, select Bibliography and choose a format style. Your bibliography will appear at the end of your paper, just like that.

Make things look nice

Make your report or project look extra professional in the Design tab! Browse different themes, colors, fonts, and borders to create work you're proud of!

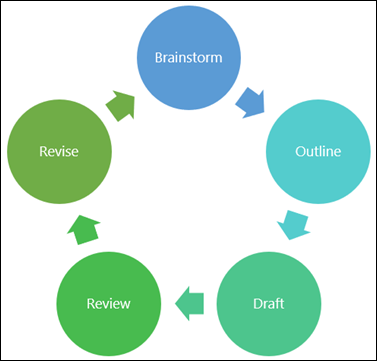

Illustrate a concept with a chart or a model by navigating to the Insert tab and choosing SmartArt . In this example, we chose Cycle and filled in text from the writing process to make a simple graphic. Choose other graphic types to represent hierarchies, flow charts, and more.

To insert a 3D model, select Insert > 3D Models to choose from a library of illustrated dioramas from different course subjects and 3D shapes.

Invite someone to write with you

If you’re working on a group project, you can work on a document at the same time without emailing the file back and forth. Select Share at the top of your page and create a link you can send to other students.

Now, everybody can open the same file and work together.

Keep learning

Check out more Microsoft Word training and support

Microsoft paper and report templates

Need more help?

Want more options.

Explore subscription benefits, browse training courses, learn how to secure your device, and more.

Microsoft 365 subscription benefits

Microsoft 365 training

Microsoft security

Accessibility center

Communities help you ask and answer questions, give feedback, and hear from experts with rich knowledge.

Ask the Microsoft Community

Microsoft Tech Community

Windows Insiders

Microsoft 365 Insiders

Was this information helpful?

Thank you for your feedback.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

MLA In-Text Citations: The Basics

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Guidelines for referring to the works of others in your text using MLA style are covered throughout the MLA Handbook and in chapter 7 of the MLA Style Manual . Both books provide extensive examples, so it's a good idea to consult them if you want to become even more familiar with MLA guidelines or if you have a particular reference question.

Basic in-text citation rules

In MLA Style, referring to the works of others in your text is done using parenthetical citations . This method involves providing relevant source information in parentheses whenever a sentence uses a quotation or paraphrase. Usually, the simplest way to do this is to put all of the source information in parentheses at the end of the sentence (i.e., just before the period). However, as the examples below will illustrate, there are situations where it makes sense to put the parenthetical elsewhere in the sentence, or even to leave information out.

General Guidelines

- The source information required in a parenthetical citation depends (1) upon the source medium (e.g. print, web, DVD) and (2) upon the source’s entry on the Works Cited page.

- Any source information that you provide in-text must correspond to the source information on the Works Cited page. More specifically, whatever signal word or phrase you provide to your readers in the text must be the first thing that appears on the left-hand margin of the corresponding entry on the Works Cited page.

In-text citations: Author-page style

MLA format follows the author-page method of in-text citation. This means that the author's last name and the page number(s) from which the quotation or paraphrase is taken must appear in the text, and a complete reference should appear on your Works Cited page. The author's name may appear either in the sentence itself or in parentheses following the quotation or paraphrase, but the page number(s) should always appear in the parentheses, not in the text of your sentence. For example:

Both citations in the examples above, (263) and (Wordsworth 263), tell readers that the information in the sentence can be located on page 263 of a work by an author named Wordsworth. If readers want more information about this source, they can turn to the Works Cited page, where, under the name of Wordsworth, they would find the following information:

Wordsworth, William. Lyrical Ballads . Oxford UP, 1967.

In-text citations for print sources with known author

For print sources like books, magazines, scholarly journal articles, and newspapers, provide a signal word or phrase (usually the author’s last name) and a page number. If you provide the signal word/phrase in the sentence, you do not need to include it in the parenthetical citation.

These examples must correspond to an entry that begins with Burke, which will be the first thing that appears on the left-hand margin of an entry on the Works Cited page:

Burke, Kenneth. Language as Symbolic Action: Essays on Life, Literature, and Method . University of California Press, 1966.

In-text citations for print sources by a corporate author

When a source has a corporate author, it is acceptable to use the name of the corporation followed by the page number for the in-text citation. You should also use abbreviations (e.g., nat'l for national) where appropriate, so as to avoid interrupting the flow of reading with overly long parenthetical citations.

In-text citations for sources with non-standard labeling systems

If a source uses a labeling or numbering system other than page numbers, such as a script or poetry, precede the citation with said label. When citing a poem, for instance, the parenthetical would begin with the word “line”, and then the line number or range. For example, the examination of William Blake’s poem “The Tyger” would be cited as such:

The speaker makes an ardent call for the exploration of the connection between the violence of nature and the divinity of creation. “In what distant deeps or skies. / Burnt the fire of thine eyes," they ask in reference to the tiger as they attempt to reconcile their intimidation with their relationship to creationism (lines 5-6).

Longer labels, such as chapters (ch.) and scenes (sc.), should be abbreviated.

In-text citations for print sources with no known author

When a source has no known author, use a shortened title of the work instead of an author name, following these guidelines.

Place the title in quotation marks if it's a short work (such as an article) or italicize it if it's a longer work (e.g. plays, books, television shows, entire Web sites) and provide a page number if it is available.

Titles longer than a standard noun phrase should be shortened into a noun phrase by excluding articles. For example, To the Lighthouse would be shortened to Lighthouse .

If the title cannot be easily shortened into a noun phrase, the title should be cut after the first clause, phrase, or punctuation:

In this example, since the reader does not know the author of the article, an abbreviated title appears in the parenthetical citation, and the full title of the article appears first at the left-hand margin of its respective entry on the Works Cited page. Thus, the writer includes the title in quotation marks as the signal phrase in the parenthetical citation in order to lead the reader directly to the source on the Works Cited page. The Works Cited entry appears as follows:

"The Impact of Global Warming in North America." Global Warming: Early Signs . 1999. www.climatehotmap.org/. Accessed 23 Mar. 2009.

If the title of the work begins with a quotation mark, such as a title that refers to another work, that quote or quoted title can be used as the shortened title. The single quotation marks must be included in the parenthetical, rather than the double quotation.

Parenthetical citations and Works Cited pages, used in conjunction, allow readers to know which sources you consulted in writing your essay, so that they can either verify your interpretation of the sources or use them in their own scholarly work.

Author-page citation for classic and literary works with multiple editions

Page numbers are always required, but additional citation information can help literary scholars, who may have a different edition of a classic work, like Marx and Engels's The Communist Manifesto . In such cases, give the page number of your edition (making sure the edition is listed in your Works Cited page, of course) followed by a semicolon, and then the appropriate abbreviations for volume (vol.), book (bk.), part (pt.), chapter (ch.), section (sec.), or paragraph (par.). For example:

Author-page citation for works in an anthology, periodical, or collection

When you cite a work that appears inside a larger source (for instance, an article in a periodical or an essay in a collection), cite the author of the internal source (i.e., the article or essay). For example, to cite Albert Einstein's article "A Brief Outline of the Theory of Relativity," which was published in Nature in 1921, you might write something like this: