- Nieman Foundation

- Fellowships

To promote and elevate the standards of journalism

Nieman News

Back to News

Strictly Q&A

February 24, 2023, auschwitz stories told by those who lived them, the director of the auschwitz-birkenau state museum in poland has collected hundreds of survivor testimonials, told with a rawness that no outsider could.

By Andrea Pitzer

Tagged with

The gate into the Auschwitz concentration camp in WWII Nazi-occupied Poland. Translated, the words say "Work sets you free." Frederick Wallace via Unsplash

Piotr Cywiński

“ Auschwitz: A Monograph on the Human ,” a 2022 book by Piotr Cywiński, tries to address that abyss. He does so not by working his way along the boundaries around Auschwitz — the dates and architecture of genocide that swallowed more than a million people , the overwhelming majority of them Jewish — but instead dives into the emptiness itself, gathering details from hundreds of memoirs and official testimonies, along with trial minutes and questionnaires. Chronology doesn’t serve as the organizing principle; instead, the book is divided into themes of human emotion and experience, such as “Decency,” “Hierarchy,” and “Fear” that emerged from looking at the survivors’ accounts as a whole.

Cywiński is a historian and has been the director of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum in Poland for more than 16 years. His polyphonic approach of bringing in hundreds of voices to tell one overarching story struck me as an answer to the question of how to write about something as vast as incomprehensible as Auschwitz.

This focus made me think of Pulitzer winner Katherine Boo who, in talking about her book “Behind the Beautiful Forevers,” balked at the idea of the journalistic impulse to make an individual a symbol of a place or an event. In a 2012 interview Poynter.org, she warned of the dangers of using one person’s story to represent a bigger concept:

“Nobody is representative. That’s just narrative nonsense. People may be part of a larger story or structure or institution, but they’re still people. Making them representative loses sight of that.”

Cywiński’s Auschwitz monograph illustrates this idea elegantly, gathering related observations with care then ceding nearly all his book to camp prisoners themselves, letting their archival testimonies converse with one another, with minimal interpretation and explanation.

Last December, more than 80 years after Nazis first sent prisoners to the small town of Oświęcim in Poland, Cywiński sat for a public interview with me at the Kosciuszko Foundation in New York. We spoke about why some stories went untold for decades, why understanding life at Auschwitz remains almost impossible and why it’s important to include a multitude of perspectives to even begin to glimpse the real story of Auschwitz.

Here are some excerpts from our conversation, which have been condensed and edited for clarity:

Train tracks that lead from the entry to the Birkenau concentration camp to the gas chambers. Birkenauwas an extension of the Auschwitz camp in WWII Nazi-occupied Poland. Andrea Pitzer

Y ou mention several times in the book the experience of prisoners entering a different world on arrival at Auschwitz. This is extremely important, and I think that this was maybe the main reason why so many survivors started to speak about Auschwitz so late. And still, 95 percent of survivors didn’t speak, didn’t give testimonials, didn’t write any memoirs. I think that they were afraid that using words from our normal world would never give the sense of the reality of the camp.

When I’m hungry, it doesn’t mean the same as when you are hungry in the camp. It’s completely different, and it’s like this with many other emotions, because they are at an extreme that we can’t imagine in our world. You’re put in a situation when the most important factors, like space and time, are completely different. You don’t know how long you will survive. When you’re speaking about hope, it means some plans for the future, but in the camp it means to survive for the next five or ten minutes. And at every moment, somebody is dying around you. That means you will also die, perhaps in a few minutes or in one hour. It’s a completely different kind of time than we experience in normal life.

At the beginning, I was thinking that I would speak about death at the end of the book. This was an error. In Auschwitz death did not happen at the end; it was present at all times and everywhere.

One of the essays in the collection is on death. There’s a quote from a survivor: “not only is life and human dignity violated here but human death counts for nothing.” For us, death is so tragic. It’s a big mystery. We will arrive all of us at one moment to face our death, but it’s something that we consider with a religious or para-religious approach, with a philosophical approach, even if we if we don’t want to organize our lives according to this destination.

In the camp death was everywhere and could arrive at every moment. Maybe the only thing that they were sure of was death. It’s also completely different when it’s an inverse point to our way of thinking about death. If I ask what you’re sure about in the immediate future, you would tell me about how you will go back home and get dinner or do something with your family. But nobody would be thinking about death as something that we can be sure of happening in the present moment.

One quote from another testimony says: “Among the Auschwitz prisoners who wrote their memoirs none of them claims the camp ennobled people.” Yet it’s woven into a lot of fabric of society before and after Auschwitz that suffering brings a kind of nobility, that there is something inherent in suffering that makes us pure or better. I think it’s important that is not what’s reflected in most of these testimonies. Yes, this perspective is present in very few testimonies. What we consider as a moral system in our society was completely different when it was recreated inside the camp. I think it was also a factor in the incapacity to speak about Auschwitz for many survivors because they begin to justify themselves, and they don’t want to justify themselves. They knew that their choices inside the camp — daily choices, I do not speak about dramatic choices — the daily choices were how to survive, to have one or two or three or days more to stay alive.

The position where you stand at the queue in order to have your soup: If you go at the starting point of the distribution of the soup, you will receive only water; if you go at the end, you’ll be beaten by some very well-positioned prisoners, some kapo or some people from the blocks, because they know that at the end, there will be some potatoes. So you have to find your own position, not too quickly and not too late. But that means you will take this place from some other prisoner. And with every choice you made, that means somebody else did not get this choice.

You also address the Sonderkommando — these people who were drafted into being active participants in the murder of other prisoners at Auschwitz. It’s perhaps the most tragic history in the camp, the story of the Sonderkommando . They were in general young men taken from different transports and put to work around the gas chambers and the crematoria. They had to burn corpses, to make all this machinery function. A clear majority were Jews, and many of them were coming from Jewish Orthodox families, and cremation of course was something they couldn’t have imagined. For decades after the war, they were considered maybe not as perpetrators but as collaborators of perpetrators, except two or three, like Shlomo Venezia or Filip Müller . Many of them stayed silent for years.

We are all very proud of our culture, our education and our sense of values. We feel really prepared to confront difficulties. Those people also, certainly they were thinking like this. But a few days were enough to change a person arriving from a normal world to a person completely acting according to the camp rules, thinking in a different way, approaching other humans in a different way, considering himself as a completely different person.

Another example of a theme that we in our world might think of quite differently than the voices we hear in the book is this idea of sacrifice. I want to speak specifically about Father Kolbe , because many people have heard about this story, and he was canonized later for switching places with a condemned person. Here’s what one of the survivors said about him: “I must stress that what impressed us was not that he gave up his life for someone else, for life wasn’t worth much in the camp. We were impressed that in front of so many SS men and prisoner functionaries, he had broken discipline and dared to step out of rank.” It’s quite different than what we might think. I heard many words like this. “If you give your life for another, that does not mean you give your life. You give your last few days or a few weeks, it’s not something exceptional. But breaking the rules, it is something, yes.”

And there were, of course, different levels of sacrifice. You can share, for example, your bread. So you have some bread. Your kid or your friend for some reason has no more bread, and maybe he’s in deeper need. You can give him the half of your bread; it seems nothing. But what was the remark of the prisoners? “Oh, look at him he’s starting to share his bread. He has no will to survive. He will be finished very quickly.” It’s not like a sacrifice, it’s like suicide. This is why I am speaking about an entire axiology that is completely different in the camp than in our perception.

A prisoners' room at the Auschwitz concentration camp. Auschwitz memorial, Poland.

You note that some of those people wo were most deeply tied into their communities actually were a tremendous disadvantage in the camp. Those who had the easiest time adapting to the camp were people coming from very low socioeconomic levels from big cities, people who had very hard childhoods with many problems in their lives. They’ve got ideas on how to adapt to those difficulties.

But at the opposite end, you get for example people from the countryside, normal people without any education, unable to understand or to speak German, unable to imagine a different world than their own, living all the time in cyclical time according to the seasons. They found themselves in the camp and were completely unable to adapt. In general they did not leave testimonies after the war, because if you finish two grades in the schools or even not two, you are unable to write your testimony.

But many other prisoners themselves tried to enter in contact with them and describe them, and this was something incredible. Many times you think it’s those people coming from very traditional settings with centuries of culture and systems of ethics who will be the strongest in a difficult time. Not really. Not really.

One of the things the general public forgets today about the enormity of the death camps and the Holocaust was that it took many years to frame even the basic understanding that we have today of what happened. It was not understood in the immediate postwar time, so survivors didn’t have that space to speak, because what they experienced was in some ways quite different than what was first said about what had happened in the camps. The situation of somebody captured in 1940 in Warsaw because he prepared some anti-Nazi, anti-German action, as a scout or something like this, was completely different than somebody who was taken from their house for nothing. The latter was unable to know why he was in this camp. It was difficult to create a definite narrative after the war if you were taken for no reason from your house or from the street and sent to the camp. If somebody was involved in some unusual actions, it was different. He was able afterward to say, “Yes I suffered a lot. It was inhuman, but I was fighting against something.”

This psychological difference was huge in the postwar narratives.

A question from the audience, from a woman whose father spent years in Auschwitz, asks about the difference between the reception of Christian and Jewish narratives. In Poland, especially after 1968, the camp narrative was more organized by Christian prisoners. In the Western world it was more organized by Jewish survivors. It was a very clear difference between the two narratives.

I remember in the ’90s when Communism ended, it became possible to travel to Poland to visit Auschwitz. The two communities of remembrance met in the same place and did not recognize each other. It was like they were speaking about some completely different history. There were different symbols, words, approaches. It created tensions, it created emotions.

It took time, even a whole generation — up until 2010 or later — for those different worlds not only to accept each other but to understand that, yes, they’re all attached to the same story, to the same place. It was very, very difficult.

And at the same time, in the late ’90s, some new history arrived. The genocide of the Roma and Sinti — so-called gypsies — was discovered by the larger public. Then Russia started to speak about the Soviet prisoners of war who were put in Auschwitz.

I think we are headed in a good direction. We are learning to understand each other and all these stories.

Andrea Pitzer is the author of three books of narrative nonfiction that explore untold histories. She was the editor of Nieman Storyboard from 2009-2012.

- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- 2024 election

- Kate Middleton

- TikTok’s fate

- Supreme Court

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

- World Politics

Read these searing quotes from an Auschwitz survivor's essay on life in the camp

Share this story.

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Read these searing quotes from an Auschwitz survivor's essay on life in the camp

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/45558310/15675169423_bc3772fdf2_k.0.0.jpg)

Today is International Holocaust Remembrance Day — a day on which it's worth taking some time to actually understand what happened during the Nazi slaughter. One of the best ways to do that is to revisit the writing of Primo Levi, a Jewish-Italian Auschwitz survivor and one of the camp's greatest and most insightful literary documentarians.

Of Levi's work, his essay "The Gray Zone" — from The Drowned and the Saved , his final book before his 1987 suicide — really stands out. It's remarkable both for its unforgettable depiction of the routine brutality of life in Auschwitz and for its penetrating psychological analysis of the camp's inner workings. Here are nine of the most insightful, terrifying, and powerful quotes from Levi's essay — ones that best exemplify the core of the piece.

1) Here's how Levi describes the experience of entering the camp:

Kicks and punches right away, often in the face; an orgy of orders screamed with true and simulated rage; complete nakedness after being stripped; the shaving off of all one's hair; the outfitting in rags.

2) For Levi, this spoke to an underlying purpose of the camps:

Remember that the concentration camp system even from its origins (which coincide with the rise to power of Nazism in Germany), had as its primary purpose shattering the adversaries' capacity to resist: for the camp management, the new arrival was by definition an adversary, whatever the label attached to him might be, and he must immediately be demolished to make sure that he did not become an example or a germ of organized resistance.

3) The camps didn't just break prisoners' will in order to prevent rebellion. They did so, Levi believes, as yet another form of cruel punishment for the crime of existing:

It is naïve, absurd, and historically false to believe that an infernal system such as National Socialism sanctifies its victims: On the contrary, it degrades them, it makes them resemble itself, and this all the more when they are available, blank, and lacking a political and moral armature.

4) No group better exemplified the way camps degraded their victims than the Sonderkommando (Special Squad). These overwhelmingly Jewish prisoners were given enough to eat for some time, but their task was horrible:

With the duly vague definition, "Special Squad," the SS referred to the group of prisoners entrusted with running the crematoria. It was their task to maintain order among the new arrivals (often completely unaware of the destiny awaiting them) who were to be sent into the gas chambers, to extract the corpses from the chambers, to pull gold teeth from jaws, to cut women's hair, to sort and classify clothes, shoes, and the content of the luggage, to transport the bodies to the crematoria and oversee the operation of the ovens, to extract and eliminate the ashes. The Special Squad in Auschwitz numbered, depending on the moment, from seven hundred to one thousand active members. These Special Squads did not escape everyone else's fate. On the contrary, the SS exerted the greatest diligence to prevent any man who had been part of it from surviving and telling. Twelve squads succeeded each other for a few months, whereupon it was suppressed, each time with a different trick to head off possible resistance. As its initiation, the next squad burnt the corpses of its predecessors.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3344124/16269108846_a93b5d28f4_k.0.jpg)

Eyeglasses, clothing, footwear and other personal effects taken from the prisoners before they were taken to the gas chamber, were found after the liberation piled up in the six remaining warehouses at the camp. ( United States Holocaust Memorial Museum , courtesy of Philip Vock)

5) Why assign Jews these tasks? For Levi, the answers have to do with the design of the camps itself.

Conceiving and organizing the squads was National Socialism's most demonic crime. Behind the pragmatic aspect (to economize on able men, to impose on other others the most atrocious tasks)...the institution represented an attempt to shift onto others — specifically, the victims — the burden of guilt, so that they were deprived of even the solace of innocence.

6) Levi recalls a soccer game between the Special Squad and their SS guards:

Nothing of this kind ever took place, nor would it have been conceivable, with other categories of prisoners; but with them, with the "crematorium ravens," the SS could enter the field on an equal footing, or almost. Behind this armistice one hears satanic laughter: it is consummated, we have succeeded, you no longer are the other race, the anti-race, the prime enemy of the millennial Reich; you are no longer the people who reject idols. We have embraced you, corrupted you, dragged you to the bottom with us. You are like us, you proud people: dirtied with your own blood, as we are. You too, like us and like Cain, have killed the brother. Come, we can play together.

7) Levi's intent is not to place the camp's inmates and guards on the same moral plane, or even to judge the Special Squad members thrown into an awful situation:

I do not know, and it does not much interest me to know, whether in my depths there lurks a murderer, but I do know that I was a guiltless victim and I was not a murderer. I know that the murderers existed, not only in Germany, and still exist, retired or on active duty, and that to confuse them with their victims is a moral disease or an aesthetic affectation or a sinister sign of complicity; above all, it is precious service rendered (intentionally or not) to the negators or truth.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/5938573/480340749.0.0.jpg)

"Survivor," a portrait of Primo Levi by Jewish artist Larry Rivers. The painting superimposes the image of another survivor on Levi's forehead. (Santi Visalli/Getty Images)

8) Instead, Levi is attempting to explain how systems of domination corrupt even their victims — and to remind people to challenge them:

The ascent of the privileged, not only in the Lager but in all human coexistence, is an anguishing but unfailing phenomenon: only in utopias is it absent. It is the duty of righteous men to make war on all undeserved privilege, but one must not forget that this is a war without end. Where power is exercised by few or only one against the many, privilege is born and proliferates, even against the will of the power itself.

9) The essay concludes with a stark reminder that while Nazism has been defeated, the psychological forces that enabled its rise are universal :

We too are so dazzled by power and prestige as to forget our essential fragility. Willingly or not we come to terms with power, forgetting that we are all inside the ghetto, that the ghetto is walled in, that outside the ghetto reign the lords of death, and close by the train is waiting.

Will you help keep Vox free for all?

At Vox, we believe that clarity is power, and that power shouldn’t only be available to those who can afford to pay. That’s why we keep our work free. Millions rely on Vox’s clear, high-quality journalism to understand the forces shaping today’s world. Support our mission and help keep Vox free for all by making a financial contribution to Vox today.

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Next Up In World Politics

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

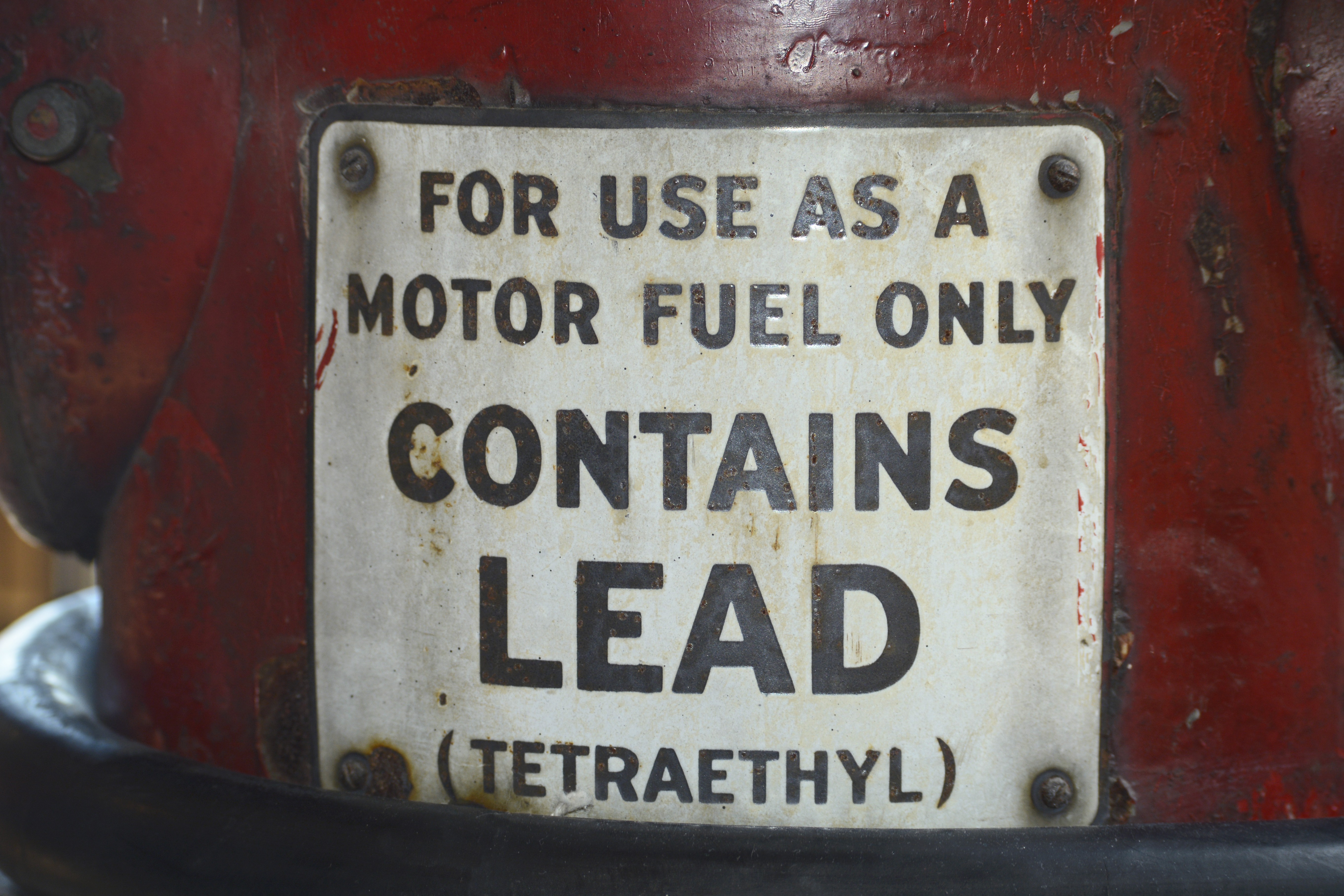

Lead pollution anywhere is a public health threat everywhere

Multigenerational housing is coming back in a big way

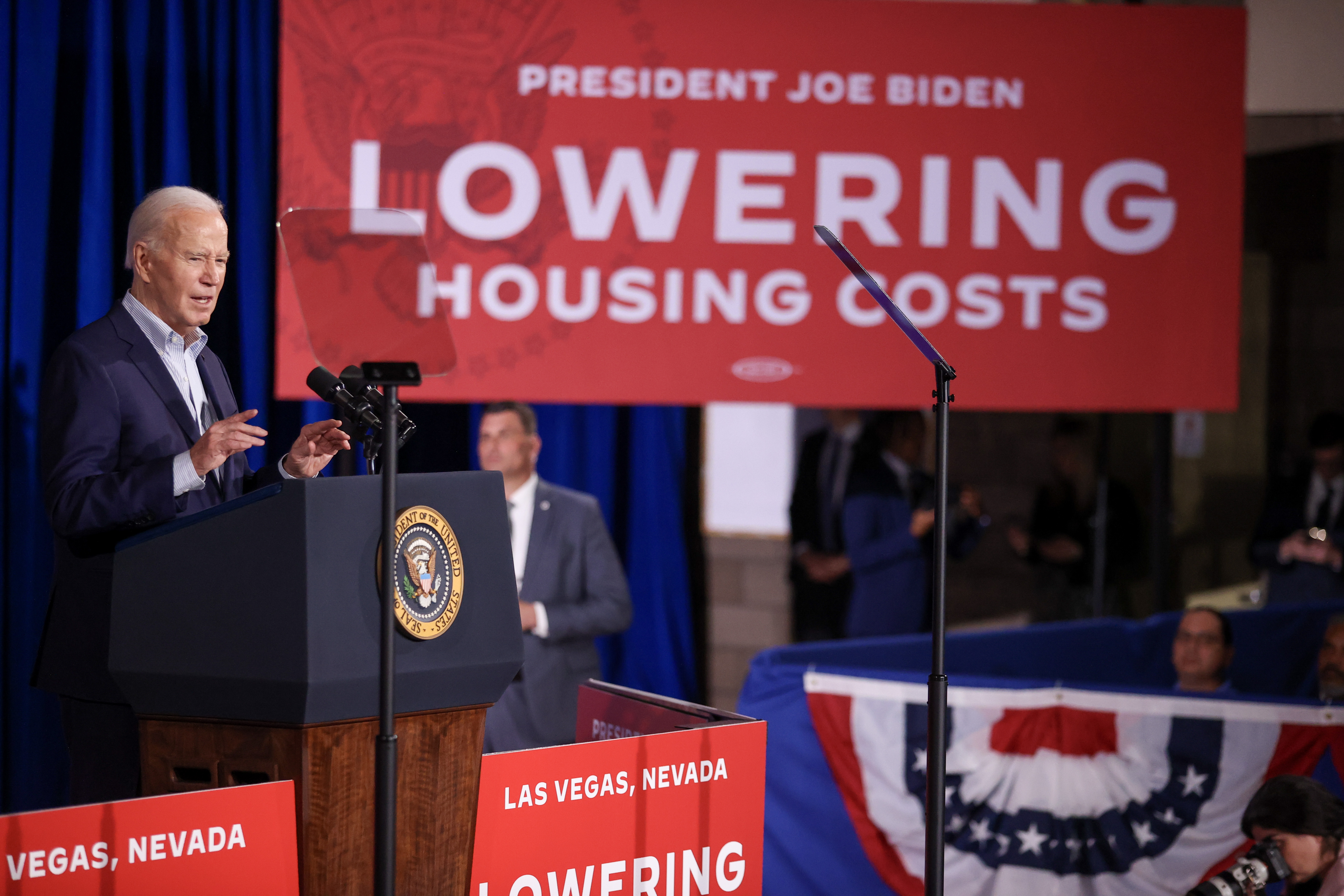

Biden wants to campaign on housing. He also sort of has to.

Want a 32-hour workweek? Give workers more power.

The harrowing “Quiet on Set” allegations, explained

The chaplain who doesn’t believe in God

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Story Corps

- Visit StoryCorps.org

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

A family helped a Holocaust survivor escape death. Then they became his real family

Emma Bowman

Philip and Ruth Lazowski, both Holocaust survivors, married over a decade after Ruth's mother saved him from a massacre, Philip said. The Lazowski family. hide caption

Philip and Ruth Lazowski, both Holocaust survivors, married over a decade after Ruth's mother saved him from a massacre, Philip said.

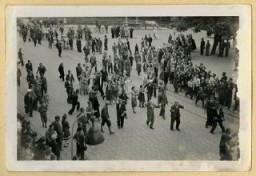

When Nazis invaded the Polish town of Bielica, Philip Lazowski and his family were among the Jewish residents who were sent to the Zhetel ghetto during Word War II.

One April morning in 1942, the Lazowski family caught wind that the Nazis were killing Jews in the ghetto, in what is now Belarus, and decided to go into hiding. Philip, then just 11 years old, helped his parents and siblings take shelter in a hideout they'd built in their apartment. He closed off the hiding spot so it wouldn't be discovered, telling his family he would find another place to hide.

But before he could, a German soldier spotted him.

Philip was then taken to the Zhetel marketplace, where German soldiers split people into two groups — those who could work and those who could not. As Nazis conducted the selection, Philip noticed that the killing squad members were sparing families with adults who had work papers.

About 1,000 Jews were killed in the massacre that day.

'We Were Lucky': Kids Of Holocaust Survivors Learned Their Parents' Life Philosophy

Book Reviews

'into the forest' tells story of one family's escape from nazi-created zhetel ghetto.

Philip, now a 91-year-old rabbi, came to StoryCorps with his wife, Ruth, last month to remember how quick thinking and a woman's kindness in that moment had saved his life.

Searching the crowds frantically, the young Philip saw a woman with the documentation in hand, a nurse who stood with her two girls.

"I went over to her and I asked her, 'Would you be kind enough to take me as your son?' " Philip recalled. "She said, 'If they let me live with two children, maybe they'll let me live with three. Hold on to my dress,' " as he tells it.

That woman, Miriam Rabinowitz, was the mother of his future wife, Ruth.

Philip and Ruth Lazowski are pictured on their wedding day in 1955. The Lazowski family hide caption

Philip and Ruth Lazowski are pictured on their wedding day in 1955.

Years later, after Philip immigrated to the U.S., a strange happenstance would miraculously reconnect him with Ruth. Author Rebecca Frankel detailed their story in the book, Into the Forest: A Holocaust Story of Survival.

While attending a wedding, Philip struck up a conversation with a woman seated next to him.

"Sitting at the table I said, 'I come from the town of Bielica,' " he said. "She says, 'You know, a girlfriend told me a story, they saved a boy from Bielica. And we don't know if he's alive.' "

That's when Philip realized he was that boy. He then got in touch with Miriam and visited her and the rest of the family. In 1955, Philip and Ruth married.

"Your mother saved my life," Philip told Ruth, 86, at Storycorps. "That's how our family began."

The Lazowskis now have three children and seven grandchildren.

Audio produced for Morning Edition by Jo Corona.

StoryCorps is a national nonprofit that gives people the chance to interview friends and loved ones about their lives. These conversations are archived at the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, allowing participants to leave a legacy for future generations. Learn more, including how to interview someone in your life, at StoryCorps.org .

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

The Holocaust

By: History.com Editors

Updated: April 11, 2023 | Original: October 14, 2009

The Holocaust was the state-sponsored persecution and mass murder of millions of European Jews, Romani people, the intellectually disabled, political dissidents and homosexuals by the German Nazi regime between 1933 and 1945. The word “holocaust,” from the Greek words “holos” (whole) and “kaustos” (burned), was historically used to describe a sacrificial offering burned on an altar.

After years of Nazi rule in Germany, dictator Adolf Hitler’s “Final Solution”—now known as the Holocaust—came to fruition during World War II, with mass killing centers in concentration camps. About six million Jews and some five million others, targeted for racial, political, ideological and behavioral reasons, died in the Holocaust—more than one million of those who perished were children.

Historical Anti-Semitism

Anti-Semitism in Europe did not begin with Adolf Hitler . Though use of the term itself dates only to the 1870s, there is evidence of hostility toward Jews long before the Holocaust—even as far back as the ancient world, when Roman authorities destroyed the Jewish temple in Jerusalem and forced Jews to leave Palestine .

The Enlightenment , during the 17th and 18th centuries, emphasized religious tolerance, and in the 19th century Napoleon Bonaparte and other European rulers enacted legislation that ended long-standing restrictions on Jews. Anti-Semitic feeling endured, however, in many cases taking on a racial character rather than a religious one.

Did you know? Even in the early 21st century, the legacy of the Holocaust endures. Swiss government and banking institutions have in recent years acknowledged their complicity with the Nazis and established funds to aid Holocaust survivors and other victims of human rights abuses, genocide or other catastrophes.

Hitler's Rise to Power

The roots of Adolf Hitler’s particularly virulent brand of anti-Semitism are unclear. Born in Austria in 1889, he served in the German army during World War I . Like many anti-Semites in Germany, he blamed the Jews for the country’s defeat in 1918.

Soon after World War I ended, Hitler joined the National German Workers’ Party, which became the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP), known to English speakers as the Nazis. While imprisoned for treason for his role in the Beer Hall Putsch of 1923, Hitler wrote the memoir and propaganda tract “ Mein Kampf ” (or “my struggle”), in which he predicted a general European war that would result in “the extermination of the Jewish race in Germany.”

Hitler was obsessed with the idea of the superiority of the “pure” German race, which he called “Aryan,” and with the need for “Lebensraum,” or living space, for that race to expand. In the decade after he was released from prison, Hitler took advantage of the weakness of his rivals to enhance his party’s status and rise from obscurity to power.

On January 30, 1933, he was named chancellor of Germany. After the death of President Paul von Hindenburg in 1934, Hitler anointed himself Fuhrer , becoming Germany’s supreme ruler.

Concentration Camps

The twin goals of racial purity and territorial expansion were the core of Hitler’s worldview, and from 1933 onward they would combine to form the driving force behind his foreign and domestic policy.

At first, the Nazis reserved their harshest persecution for political opponents such as Communists or Social Democrats. The first official concentration camp opened at Dachau (near Munich) in March 1933, and many of the first prisoners sent there were Communists.

Like the network of concentration camps that followed, becoming the killing grounds of the Holocaust, Dachau was under the control of Heinrich Himmler , head of the elite Nazi guard, the Schutzstaffel (SS) and later chief of the German police.

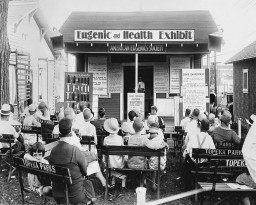

By July 1933, German concentration camps ( Konzentrationslager in German, or KZ) held some 27,000 people in “protective custody.” Huge Nazi rallies and symbolic acts such as the public burning of books by Jews, Communists, liberals and foreigners helped drive home the desired message of party strength and unity.

In 1933, Jews in Germany numbered around 525,000—just one percent of the total German population. During the next six years, Nazis undertook an “Aryanization” of Germany, dismissing non-Aryans from civil service, liquidating Jewish-owned businesses and stripping Jewish lawyers and doctors of their clients.

Nuremberg Laws

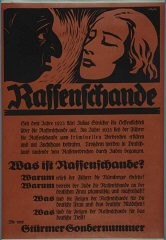

Under the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, anyone with three or four Jewish grandparents was considered a Jew, while those with two Jewish grandparents were designated Mischlinge (half-breeds).

Under the Nuremberg Laws, Jews became routine targets for stigmatization and persecution. This culminated in Kristallnacht , or the “Night of Broken Glass” in November 1938, when German synagogues were burned and windows in Jewish home and shops were smashed; some 100 Jews were killed and thousands more arrested.

From 1933 to 1939, hundreds of thousands of Jews who were able to leave Germany did, while those who remained lived in a constant state of uncertainty and fear.

HISTORY Vault: Third Reich: The Rise

Rare and never-before-seen amateur films offer a unique perspective on the rise of Nazi Germany from Germans who experienced it. How were millions of people so vulnerable to fascism?

Euthanasia Program

In September 1939, Germany invaded the western half of Poland , starting World War II . German police soon forced tens of thousands of Polish Jews from their homes and into ghettoes, giving their confiscated properties to ethnic Germans (non-Jews outside Germany who identified as German), Germans from the Reich or Polish gentiles.

Surrounded by high walls and barbed wire, the Jewish ghettoes in Poland functioned like captive city-states, governed by Jewish Councils. In addition to widespread unemployment, poverty and hunger, overpopulation and poor sanitation made the ghettoes breeding grounds for disease such as typhus.

Meanwhile, beginning in the fall of 1939, Nazi officials selected around 70,000 Germans institutionalized for mental illness or physical disabilities to be gassed to death in the so-called Euthanasia Program.

After prominent German religious leaders protested, Hitler put an end to the program in August 1941, though killings of the disabled continued in secrecy, and by 1945 some 275,000 people deemed handicapped from all over Europe had been killed. In hindsight, it seems clear that the Euthanasia Program functioned as a pilot for the Holocaust.

'Final Solution'

Throughout the spring and summer of 1940, the German army expanded Hitler’s empire in Europe, conquering Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg and France. Beginning in 1941, Jews from all over the continent, as well as hundreds of thousands of European Romani people, were transported to Polish ghettoes.

The German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 marked a new level of brutality in warfare. Mobile killing units of Himmler’s SS called Einsatzgruppen would murder more than 500,000 Soviet Jews and others (usually by shooting) over the course of the German occupation.

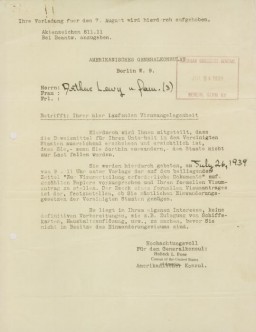

A memorandum dated July 31, 1941, from Hitler’s top commander Hermann Goering to Reinhard Heydrich, chief of the SD (the security service of the SS), referred to the need for an Endlösung ( Final Solution ) to “the Jewish question.”

Yellow Stars

Beginning in September 1941, every person designated as a Jew in German-held territory was marked with a yellow, six-pointed star, making them open targets. Tens of thousands were soon being deported to the Polish ghettoes and German-occupied cities in the USSR.

Since June 1941, experiments with mass killing methods had been ongoing at the concentration camp of Auschwitz , near Krakow, Poland. That August, 500 officials gassed 500 Soviet POWs to death with the pesticide Zyklon-B. The SS soon placed a huge order for the gas with a German pest-control firm, an ominous indicator of the coming Holocaust.

Holocaust Death Camps

Beginning in late 1941, the Germans began mass transports from the ghettoes in Poland to the concentration camps, starting with those people viewed as the least useful: the sick, old and weak and the very young.

The first mass gassings began at the camp of Belzec, near Lublin, on March 17, 1942. Five more mass killing centers were built at camps in occupied Poland, including Chelmno, Sobibor, Treblinka, Majdanek and the largest of all, Auschwitz.

From 1942 to 1945, Jews were deported to the camps from all over Europe, including German-controlled territory as well as those countries allied with Germany. The heaviest deportations took place during the summer and fall of 1942, when more than 300,000 people were deported from the Warsaw ghetto alone.

Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

Amid the deportations, disease and constant hunger, incarcerated people in the Warsaw Ghetto rose up in armed revolt.

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising from April 19-May 16, 1943, ended in the death of 7,000 Jews, with 50,000 survivors sent to extermination camps. But the resistance fighters had held off the Nazis for almost a month, and their revolt inspired revolts at camps and ghettos across German-occupied Europe.

Though the Nazis tried to keep operation of the camps secret, the scale of the killing made this virtually impossible. Eyewitnesses brought reports of Nazi atrocities in Poland to the Allied governments, who were harshly criticized after the war for their failure to respond, or to publicize news of the mass slaughter.

This lack of action was likely mostly due to the Allied focus on winning the war at hand, but was also partly a result of the general incomprehension with which news of the Holocaust was met and the denial and disbelief that such atrocities could be occurring on such a scale.

'Angel of Death'

At Auschwitz alone, more than 2 million people were murdered in a process resembling a large-scale industrial operation. A large population of Jewish and non-Jewish inmates worked in the labor camp there; though only Jews were gassed, thousands of others died of starvation or disease.

In 1943, eugenics advocate Josef Mengele arrived in Auschwitz to begin his infamous experiments on Jewish prisoners. His special area of focus was conducting medical experiments on twins , injecting them with everything from petrol to chloroform under the guise of giving them medical treatment. His actions earned him the nickname “the Angel of Death.”

Nazi Rule Ends

By the spring of 1945, German leadership was dissolving amid internal dissent, with Goering and Himmler both seeking to distance themselves from Hitler and take power.

In his last will and political testament, dictated in a German bunker that April 29, Hitler blamed the war on “International Jewry and its helpers” and urged the German leaders and people to follow “the strict observance of the racial laws and with merciless resistance against the universal poisoners of all peoples”—the Jews.

The following day, Hitler died by suicide . Germany’s formal surrender in World War II came barely a week later, on May 8, 1945.

German forces had begun evacuating many of the death camps in the fall of 1944, sending inmates under guard to march further from the advancing enemy’s front line. These so-called “death marches” continued all the way up to the German surrender, resulting in the deaths of some 250,000 to 375,000 people.

In his classic book Survival in Auschwitz , the Italian-Jewish author Primo Levi described his own state of mind, as well as that of his fellow inmates in Auschwitz on the day before Soviet troops liberated the camp in January 1945: “We lay in a world of death and phantoms. The last trace of civilization had vanished around and inside us. The work of bestial degradation, begun by the victorious Germans, had been carried to conclusion by the Germans in defeat.”

Legacy of the Holocaust

The wounds of the Holocaust—known in Hebrew as “Shoah,” or catastrophe—were slow to heal. Survivors of the camps found it nearly impossible to return home, as in many cases they had lost their entire family and been denounced by their non-Jewish neighbors. As a result, the late 1940s saw an unprecedented number of refugees, POWs and other displaced populations moving across Europe.

In an effort to punish the villains of the Holocaust, the Allies held the Nuremberg Trials of 1945-46, which brought Nazi atrocities to horrifying light. Increasing pressure on the Allied powers to create a homeland for Jewish survivors of the Holocaust would lead to a mandate for the creation of Israel in 1948.

Over the decades that followed, ordinary Germans struggled with the Holocaust’s bitter legacy, as survivors and the families of victims sought restitution of wealth and property confiscated during the Nazi years.

Beginning in 1953, the German government made payments to individual Jews and to the Jewish people as a way of acknowledging the German people’s responsibility for the crimes committed in their name.

The Holocaust. The National WWII Museum . What Was The Holocaust? Imperial War Museums . Introduction to the Holocaust. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum . Holocaust Remembrance. Council of Europe . Outreach Programme on the Holocaust. United Nations .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Featured Clinical Reviews

- Screening for Atrial Fibrillation: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement JAMA Recommendation Statement January 25, 2022

- Evaluating the Patient With a Pulmonary Nodule: A Review JAMA Review January 18, 2022

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

Survivors, Victims, and Perpetrators: Essays on the Nazi Holocaust

University of Illinois Medical Center Chicago

This article is only available in the PDF format. Download the PDF to view the article, as well as its associated figures and tables.

This book delineates the social setting and the process of organizing the extermination of millions according to National Socialist philosophy. As Hamburg notes in his foreword, the "level of sophistication in modern organization and technology" that the Germans brought to this work was unique—railway schedules, euphemisms for murder, classifications of Gypsies, Jews, Poles, and political prisoners, the architectural design and chemistry of mass murder. Also detailed are the use of inmates as cards for political negotiation and the resistance of some Italian Fascists and German clergymen.

There is a section on the victims, telling how survivors coped in the camps and afterwards, and about the psychotherapy of survivors and what happens to their children. A general model of stress and coping under extreme conditions is developed by Benner, Roskies, and Lazarus.

A final section deals with the perpetrators. There are diaries and autobiographical material from guards and prominent Nazis, as

Bernstein NR. Survivors, Victims, and Perpetrators: Essays on the Nazi Holocaust. JAMA. 1982;247(22):3138. doi:10.1001/jama.1982.03320470078043

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Cardiology in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

- Auschwitz Photos

- Birkenau Photos

- Mauthausen Photos

- Then and Now

- Paintings by Jan Komski – Survivor

- Geoffrey Laurence Paintings

- Paintings by Tamara Deuel – Survivor

- David Aronson Images

- Haunting Memory

- Holocaust Picture Book – The Story of Granny Girl as a Child

- Birkenau and Mauthausen Photos

- Student Art

- Photos – Late 1930s

- Holocaust Photos

- Lest We Forget

- Carapati – a Film

- Warsaw Ghetto Photos

- Nordhausen Liberation

- Dachau Liberation

- Ohrdruf Liberation

- Gunskirchen Lager Pamphlet

- Buchenwald Liberation

- Chuck Ferree

- Lt. Col. Felix Sparks

- Debate the Holocaust?

- Books by Survivors

- Children of Survivors

- Adolf Eichmann – PBS

- Adolf Hitler’s Plan

- Himmler Speech

- Goebbels Diaries

- Letter on Sterilization

- Letters on Euthanasia

- Nazi Letters on Executions

- Page of Glory

- Homosexuals

- Gypsies in Auschwitz I

- Gypsies in Auschwitz 2

- Babi Yar Poem

- Polish Citizens and Jews

- Harold Gordon

- Sidney Iwens

- I Cannot Forget

- Keep Yelling! A Survivor’s Testimony

- A Survivor’s Prayer

- In August of 1942

- Jacque Lipetz

- Walter Frank

- Helen Lazar

- Lucille Eichengreen

- Judith Jagermann

- Filip Muller

- Holocaust Study Guide

- Holocaust Books A-Z

- Anne Frank Biography | 1998 Holocaust Book

- Help Finding People Lost in the Holocaust Search and Unite

- Holocaust history and stories from Holocaust Photos, Survivors, Liberators, Books and Art

- Remember.org Origins

Poetry, Essays, & Short Stories by Children of Survivors

This section is devoted to.

Poetry, Essays, & Short Stories by Children of Survivors and Our Parents.

From Maxine Shoshanna Persaud, Toronto, Canada:

Many years ago I wrote the following words into my diary on a night when my parents were having a particularly hard time coping with life. Life, not as we see it , but as seen through the eyes of Holocaust survivors. I could not comfort them that night and so I wrote this in the hope that I could absorb some of their pain, so that they might live again, not merely exist. I wanted to communicate what they could not. Since then, I have learned that words, even the words of the survivors themselves, pale when compared to the atrocities committed against them by the Nazis.

That time so long ago and yet, so near They gassed the beaten then, melted them Like the hot wax of a shabbos candle The blood stained ball of each rising sun, and I, formed only by G-d’s will not word, living only on the dreams of the two that would conceive me, cried out in anguish, lamented, in my invisible, outraged soul. For those whose earthly screams, were forever silenced, In a world where few can still hear their tortured echoes. Crimes against humanity never die, only the victims. And we all suffer the legacy. ——————————–

The following three poems are from Izzy Nelken:

Yom HaSho’a 1996

By izzy nelken.

Y om HaSho’a in Israel I remember it so well Going back twenty two years Re-living some of my worst fears We had to turn the TV off So my mom wouldn’t be reminded of…

Of what was she not supposed to be reminded? What was the secret that was so well guarded? My parents were with me at home but where were mom’s parents? how come she was alone? There were stories of a horrible train which mom told with a great deal of pain I knew that her parents came to a terrible fate That had something to do with bigotry and hate

As a kid I learned not to ask which was not always an easy task Until this very day, I’m missing details there are only a few, very sketchy tales

So I would go on to school dressed up like a fool In Khaki shorts and a white shirt which had so much starch that it actually hurt US kids took turns standing by a Yahrzeit candle each one for a little while back then, in Israel, that was the style I tried my best to look sad as I stood by the candle But my friends would tell jokes that were too funny to handle So I would start to smile but just for a while Pretty soon my shift was done and now it was time to really have some fun Some other kid took my place he stood by the candle and made a serious face So I tried to make him laugh by saying all sorts of funny stuff

Looking at all of this now I am beginning to see how The Nazis tried to destroy the flame and the spark and they almost managed to make it totally dark But somehow our parents managed to survive and they made it to the free world alive We were all kids of the second generation and our parents brought us to the Israeli nation I went to a Hebrew school with a Jewish “in crowd” And of that, we can all feel very proud Standing by a candle so many years later I feel the tears which were masked by laughter ============

Trying to grasp Elie Wiesel’s “Night” It’s an internal fight I read two pages, leave and come back imagine the gallows around someone’s neck

Elie’s father was well respected it didn’t help him when he was “selected” whatever they had was taken away and there was nothing you could do or say

My grandfather had a lot of clout but our entire family was wiped out he had a factory and property and bank accounts today, I am filled with doubts: a man works all his life to collect then, one day it is taken, so what’s the effect?

“Men to the left, women to the right” mother and sister are soon out of sight this happened to our parents but could have been us and yesterday, we made such a fuss should we eat Italian or Chinese? they survived on snow, so please…

sitting in Chicago, my belly is full they weren’t so lucky, under Nazi rule

you stand in a group of five barely alive and try to survive

A few days after Elie’s operation the Nazis announce an evacuation should they leave or should they stay? what’s the right answer, who can say? they must decide there is no place to hide

The other day I went for a run on the Lakeshore, under the sun with a Walkman and a bottle of Evian what can I say, it was a lot of fun But can you imagine running all night the SS guard has you in his sight the machine gun is fired if you get tired

Elie slept just above his dad the Nazi hit him on the head and the next day, he was dead

This is very real and also un-imaginable there’s a lesson here but it’s so intangible

What’s important in life? my family and my wife education, career and financial success who are we trying to impress?

But in times of extreme strife an extra blanket may save your life all you want is soup and bread and a place to rest your head

We live very good here and it won’t disappear This I try to believe so I can live a normal life with my wife =============

The ghosts of Auchwitz are chasing me again just like they did when I was ten I sat with in the kitchen with my mom trying to speak, I was quite dumb

Tried to listen to what she had to say wished it was just another regular day and now its midnight and I am drunk smoked a cigar and smell like a skunk what is the meaning of life, I try to figure with the skills of a mathematician and all its rigor

Menke Kalisch, Kopel Reich those are important figures in my psych I can feel them fight with all their might “Torah is important, everything else is fake” No! More dough you got to make

Mom would wake up every morning and sort of go into mourning Where is her family and Galanta, she tried to shout Do you know what this is about?

Lisa lies next to me. so innocent never had to deal with anything indecent wish I could be like her and think that life is fair But I think of my uncle, whom I never met but can’t seem to be able to forget and both of my grandparents and their families rolling in their grave whom no one wanted to save

===================================================

From Jackie Ruben:

I am a psychology graduate student. My grandmother is Hungarian and, although she left Hungary right before the war, she lost many relatives including her parents and two siblings. I wrote the following personal essay at the beginning of this year. Would you pleasepost it in the Cybrary?

Jackie Ruben—-

In My Grandmother’s Kitchen

By jackie ruben.

What do we talk about, as my grandma chops the onions, the green peppers, the tomatoes, and starts to saute them at low heat?…. I have a mental picture of my beautiful grandmother, ever vigilant, making sure that the onions are translucent enough, yet not burnt. Everything’s all right….

“Mami, where are your parents?”

Something changes…Can my little child memories crystallize?

“They’re dead….,”a whisper,”…. they were killed….”

She sets her wooden spoon down and stares out the window, her left hand touching her cheek and covering her mouth, as I’ve often seen her do since that first memory, so many years ago.

“Were they killed with a sword?”

No answer… What’s happened here? I’ve never seen my grandmother cry… herbright green-grey eyes become water as I approach her, wandering, fearing whatever it is, what the shadow, the terrible thing is…

And she hugs me and whispers in my ear, “No, my ‘muggetcita,’ my little flower, no…”

Later that day, my mother would explain that my grandmother’s parents, her sister Irenke, her brother Gyula, his wife Etush, their children and many more family members, had been “gassed,” whatever that meant, at a place called Auschwitz. I learned the meaning of that name way before I could spell…I also learned soon enough not to ask my grandmother about her family too often. She didn’t even talk with my mom and my aunt about those things. Although I was curious, I didn’t want my Mami to cry. Words floated in low, somber tones, though, and I heard them all…”Nazis…SS…Zyklon B…concentration camps….” And I remembered.

Holocaust… The word that symbolized my family’s taboo subject.To me, it is a word that encompasses it all, yet will never be enough. It is a word that has followed me throughout my life. It is also the wound of my heart that will never heal.It is, in short, my family legacy–one that, I have sworn to myself, I will pass down to the generations–the most important lesson to teach my kids.

The meaning of the word “Holocaust” embodies, more than anything, the biggest lesson, the most important present that my grandmother has given me. She has taught me, through her pain, that we must never forget. Sixty years have not eased the crack in her soul.When my grandmother thinks of her Hungarian family, she is my age again, timeless, finding out again and again and again that she will NEVER see her family again.

And I have turned my twenty-three years of learning on her. We went to Hungary last year, she and I, as well as my parents. For her, it was the first time she would return in close to sixty years.

We went to Mezocsat, the town of her youth. We found the Jewish Cemetery and there, amidst the overgrown weeds and fallen tombstones, we saw the wall with the names of the town’s Jews that had been taken. There are no tombs to visit… there are only names and ages on a wall, unchanging, like the faces on the photographs…

For the first time in my life, my dead family materialized… I saw then, that those names had belonged to REAL people. I felt their presence, our link… people who were not just my grandma’s family who had been murdered in the Holocaust, but MINE as well.

My family too had been murdered.

And although we had not tombstones, you see, we did put a little stone at the wall, for each of the “Schwarcz” listed and for the rest of the Mezocsat Jews, whose memories only survive as names on these hard, cold walls, and as memories in those old folks who knew them and those young folks who, like me, refuse to forget.

When I went back home to visit during the winter break, the few photos left of my family became oh-so-precious.I laser-copied them.

Irenke, my grandmother’s sister, you and I were born on the same date… I have your Yiddish name, Bluma… and, like you, I like to cook…

“Oh sons of Irenke,” I wrote in my photo album,” Oh, children of Gyula, where are your sweet little faces? Sweet Irenke and Etush, you’re frozen in time forever. Beautiful Jewish women. Innocent Jewish women. Where’s Hermina, my mother’s “Mami,”-your body wasn’t allowed to follow its natural course neither in life nor in death. Your spirits surround me, your eyes haunt me. I look at your hands in these old photos but can’t reach across death and time to touch them… I can see them becoming ashes… WHY?”

“Irenke, you haunt me, sister, grand-aunt…Twin: we were born years apart, yet on the same date. Who were you? What were your dreams? Beautiful photos don’t reveal the horror. Bluma, I didn’t know you but you won’t be forgotten. You weren’t given a chance to have your own children, my cousins too have been murdered. I give you my descendants. They’ll remember you, though it isn’t the same, is it?….Would you have taught your little ones how to make “kalacs” and recite the “Sh’ma” like my “Mami”-your “Margitka” taught me? We’ll never know….”

There are six empty pages in my photo album that will never be filled with the photos never taken of my murdered family’s descendants.

There are six million empty album pages that will never be filled.

From Jessica Hollander: I wrote this poem when I was in my first year of high school, at age 14. I submitted it in a poetry writing contest in southern California and won first place for it. there was a special ceremony and Mel Mermelstein was present to give my award. Here it goes….

There Lies Hope

By jessica hollander.

With one great swipe of his unmerciful hand, He led us destruction. With one great tear streaming from my eye, I send myself back in time to those painful years. A time when the world was ablaze with a burning hatred. A hatred so threatening and vicious, Against a humble people so full of innocence. Why?

I question myself, gazing above into the clear blue sky. Expecting an answer, but no answer comes. With each fresh tear, I struggle with my burden Until one night in my dream The answer is revealed.

I received the following poem from From Diane Schmolka:

In All Those Camps For every particle of dust there was a name Not only when the sunlight reveals their properties floating in air that it is a phase through which they energize It is in the pulse of non-perceived awareness that their power utters every word in the primeval language once spoken in time. There are those I love dearly who do not believe there is any gift created by suffering loss. It is only when they are ready to let their arms brush against minute mouldered remains settled on cot posts, door jambs hospital beds and barbed-wire fences; when they journey to places wherein loved ones embrace them they can know joy from severed attachment I have watched them in their sleep When they dream, I believe tortured relatives sprinkle symbolice speech in pantomimes denied any sense in mornings Like ash, feelings well up from any past time as dead loved ones create moments the way a cat quietly arrives on what you’re reading to claim you for their own. I know when I awake on nights wherein I see no moon that stars will always shine from bones pulverized in all those camps I know now I can sing Kaddish only when charoset has once stuck in my throat. by Diane Schmolka. first published in “The Ottawa Unitarian” Summer,1995

Poetry, Essays, & Short Stories by Children of Survivors

If you have art, poetry, short stories, plays, etc. by survivors in your family or inspired by the fact that you are a child of a holocaust survivor, please contact remember.org.

Remember. Zachor. Sich erinnern.

Remember.org helps people find the best digital resources, connecting them through a collaborative learning structure since 1994. If you'd like to share your story on Remember.org, all we ask is that you give permission to students and teachers to use the materials in a non-commercial setting. Founded April 25, 1995 as a "Cybrary of the Holocaust". Content created by Community. THANKS FOR THE SUPPORT . History Channel ABC PBS CNET One World Live New York Times Apple Adobe Copyright 1995-2024 Remember.org. All Rights Reserved. Publisher: Dunn Simply

APA Citation

Dunn, M. D. (Ed.). (95, April 25). Remember.org - The Holocaust History - A People's and Survivors' History. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from remember.org

MLA Citation

To bookmark items, please log in or create an account.

Advanced Search Filters

In addition to or instead of a keyword search, use one or more of the following filters when you search.

Experiencing History Holocaust Sources in Context

- Create Account

1 of 14 Collections in

Jewish Perspectives on the Holocaust

Holocaust diaries.

Jewish diaries offer unique, personal accounts of the Holocaust. Motivated to record their experiences for a variety of reasons, these authors all had different identities, national traditions, education levels, faiths, politics, and ages. The sources collected here reflect this diversity and show the value of diaries for the study of the Holocaust.

Jewish diaries were not always recognized as critical sources for the study of the Holocaust . Due to an early focus on perpetrators and official documents when the field of Holocaust studies first began, researchers tended to dismiss Jewish diaries as subjective and unreliable. 1 But in recent decades, many scholars have shown how these concerns about personal diaries can be used to add valuable details to official accounts of events. The sources featured in this collection add personal details from a wide range of different Jewish experiences of the Holocaust. 2

Many different types of personal records that Jewish people kept under Nazi persecution can be considered to be forms of Holocaust diaries. Soon after the end of World War II , people's ideas of Holocaust diaries were shaped by the publication of Anne Frank’s diary—a personal account of a Jewish girl hiding with her family in occupied Amsterdam . 3 But the sources in this collection show that there are many other kinds of Holocaust diaries. The examples included here demonstrate that first-person writing from the period of the Holocaust takes different forms. 4

All of the authors in this collection were targeted by antisemitic Nazi racial laws for being Jewish. Whether or not they identified as Jewish or framed events in their diaries as Jewish experiences, their lives were threatened because they had been labeled Jewish by others. It is this common experience of persecution that links these very different sources. 5

Individual motivations for writing a diary—and the conditions of writing—varied considerably from case to case. Some authors kept a diary throughout their lives and started writing before the time of the Holocaust. Many others—from children like Peter Feigl to adults like Jechiel Górny —were inspired to write by the traumatic events they experienced. Some authors were driven to write by a desire to bear witness to the injustices and crimes commited against their communities. Other writers like Moryc Brajtbart wrote only for themselves with no other readers in mind. It is likely that many people recorded their experiences not only to document their persecution, but also to help work through their personal trauma.

Difficult and often deadly living conditions in camps and ghettos influenced the form these diaries took. During the Holocaust, very few Jewish people were able to note down events as they were happening. In the various camps in which Jews lived and died, writing was forbidden. The demands of work and survival also robbed the prisoners of the energy, time, and materials necessary to document their experiences.

Outside camps and ghettos, writing could still be extremely dangerous. If one was in hiding, anything that could give away a person’s true identity was an unnecessary risk. It took enormous courage and energy for many Jewish people to write. This means that many texts from the Holocaust that we think of as diaries actually represent an array of different writings on a wide range of forms and topics. Many diary writers went through periods in which they were not able to write. When they found the time and energy to do so—often after fleeing a ghetto to hide in a so-called "Aryan" part of a town or village—what they wrote was more like a memoir in terms of style and narrative. 6

The authors of Holocaust diaries varied widely in terms of their personal biographies, religious traditions, and educations. The authors' motivations for writing were all different as well. The unique primary sources gathered here explore some of the wide variety of Jewish experiences of persecution during the Holocaust—and show how different kinds of Holocaust diaries can add to our understanding of these events.

Raul Hilberg, a founding contributor to the field of Holocaust studies and author of the first comprehensive study of the Holocaust, based his 1,000-page study exclusively on primary sources left by German agencies and institutions, as well as the occasional memoir by a high Nazi official. Hilberg's landmark study was published in 1961. For the authoritative edition, see Raul Hilberg, The Destruction of the European Jews (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003).

Many of the sources presented here are also featured in the book series, Jewish Responses to Persecution, 1933–1946, published by the US Holocaust Memorial Museum.

The first translation of Anne Frank's diary into English was published in 1952. For a revised critical edition, see Anne Frank, The Diary of Anne Frank: The Revised Critical Edition (New York: Doubleday, 2003).

For more on Holocaust diaries as a genre of sources in scholarship, see the related online lecture from the US Holocaust Memorial Museum.

The definition of "Jewishness" in this context—often based on Nazi criteria—has been criticized and debated. See for example the essay by historian Isaac Deutscher, "Who Is a Jew?" in Deutscher, The Non-Jewish Jew and Other Essays (London: Merlin Press, 1981).

Memoirs are typically written after the events they depict, while diaries are generally written about current events. For an introduction to the many aspects of Jewish diary writing during the Holocaust, see Alexandra Garbarini, Numbered Days: Diaries and the Holocaust (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006).

All 21 Items in the Holocaust Diaries Collection

Diary of Đura Rajs

tags: aging & the elderly belongings children & youth deportations forced labor health & hygiene

type: Diary

Diary of Peter Feigl

tags: belongings children & youth family health & hygiene hope money refugees & immigration religious life

Diary of Susi Hilsenrath

tags: children & youth children's diaries family health & hygiene refugees & immigration religious life

Diary of Elisabeth Ornstein

tags: belongings children & youth children's diaries family homesickness religious life

Diary of Jacques Berenholc

tags: children & youth depression food & hunger friendship health & hygiene refugees & immigration

Diary of Aharon Pick

tags: fear & intimidation ghettos health & hygiene humiliation

Diary of Jechiel Górny

tags: black market deportations forced labor ghettos group violence

Diary of Mirjam Korber

tags: depression Displaced Persons friendship ghettos health & hygiene homesickness letters & correspondence money

Diary of Elvira Kohn

tags: food & hunger health & hygiene hope liberation women's experiences

Diary of Saartje Wijnberg

tags: family gender health & hygiene liberation living underground loneliness women's experiences

Anonymous Diary from the Warsaw Ghetto

tags: children & youth community food & hunger health & hygiene living underground

Deposition of Pesakh Burshteyn

tags: aging & the elderly children & youth deportations family fear & intimidation forced labor ghettos

type: Report

Diary of Herzl Mazia

tags: food & hunger leisure & recreation letters & correspondence

Diary of Abraham Frieder

tags: bureaucracy community deportations depression fear & intimidation

Diary of Adolf Guttentag

tags: aging & the elderly deportations family ghettos health & hygiene suicide Theresienstadt

Diary of Moryc Brajtbart

tags: children & youth deportations depression family homesickness living underground loneliness

Memoir of Fryderyk Winnykamień

tags: children & youth family fear & intimidation ghettos hope humiliation living underground

type: Memoir

Diary of Michal Kraus

tags: children & youth family

Memoir of Calel Perechodnik

tags: antisemitism ghettos Judaism law enforcement religious life Zionism

Diary of Irene Hauser

tags: children & youth depression family food & hunger gender health & hygiene women's experiences

Diary of Janusz Korczak

tags: children & youth deportations depression health & hygiene

Thank You for Supporting Our Work

We would like to thank The Alexander Grass Foundation for supporting the ongoing work to create content and resources for Experiencing History. View the list of all donors and contributors.

Learn more about sources for your classroom

- Getting Started

- Find Articles

- Find Encyclopaedias, Chronologies, and Bibliographies

- Find Information on Victims and Destroyed Communities

- Find Information on Rescuers

- Find Primary Sources

- Find Legal Material

Primary Sources The Holocaust at Gelman Library

- Kiev Judaica Collection: The I. Edward Kiev Judaica Collection has numerous books, pamphlets, and graphic materials related to the Holocaust, including yizkor books. These are memorial books that were published by Holocaust survivors commemorating their destroyed towns and those who died there. Many are in foreign languages, but some have English translations as well and photos/drawings that can be easily interpreted.

By clicking on the GW & Consortium catalogue on the library home page, typing Holocaust Jewish (1939-1945) Source, the list of records that will appear will mostly consist of records of items in the consortium libraries that are, or include, primary sources. An identical search can be done in Worldcat which is comprised of the catalogues of thousands of libraries. Another potentially useful search is Holocaust Jewish (1939-1945) Personal Narratives.

- Kiev Family Trust Graphic Arts Collection,1493-1969 Has prints, posters, cartoons, postcards and other Judaica, primarily related to antisemitism.

- Kiev Family Trust Pamphlet Collection Contains pamphlets concerning antisemitism and sermons from prominent European and American rabbis.

- William R. Perl Collection Perl rescued an estimated forty thousand European Jews from annihilation by the Nazis by helping them illegally immigrate to Mandatory Palestine.

- Jewish Responses to Persecution Gelman Fourth Floor Stacks DS134.255 .M38 2010

Primary Sources on The Holocaust Online and at Other Local Repositories

- Yad Vashem Digital Collections

- U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum: The Collections Division of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum consists of eight branches: Archives, Art and Artifacts, Film and Video, Music, Oral History, Photo Archives, Collections Management, and Conservation. The Archives Branch of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum is one of the world's largest and most comprehensive repositories of Holocaust-related records. The collection consists of nearly 42 million pages of records.

- Experiencing History: Jewish Perspectives on the Holocaust Learn about everyday Jewish life during the Holocaust by engaging with a variety of Jewish sources from the period. Discover and analyze a diary, a letter, a newspaper article, a policy paper by an international Jewish organization, see a photograph, or watch film footage. Produced by the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

By clicking on the classic catalogue (under the Research link at the top of the library home page), typing Holocaust Survivors Interviews and changing the box to the right to subject, the list of records will be for items in the consortium libraries. An identical search can be done in Worldcat which is comprised of the catalogues of thousands of libraries.

- Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies GW Libraries' Special Collections Research Center is now a partner site with Yale University, providing GW and the public with access to the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies. This collection requires researchers to create an account and request access to the online streaming content through Yale Library. The directions given at our web page outline the required steps. Once you have created an account, requested an item, and received an email approving your request you may visit the SCRC to view the content

- Voice/Vision Holocaust Survivor Oral History Archive "The Voice/Vision Holocaust Survivor Oral History Archive exists to maintain a collection of oral testimonies of those who survived the Holocaust and make these widely accessible for educational purposes. Through interlibrary loan, the Internet and community outreach, we make the oral testimonies and transcriptions available to researchers, students and the general public." A project of the Univesity of Michigan.

Contact Information

Special Collections Research Center Melvin Gelman Library 2130 H St., NW, Suite 704 Washington, DC 20052 (202) 994-7549 Hours: Monday-Friday, 10 AM - 5 PM

For manuscripts and collections inquiries: [email protected]

For University Archives inquiries: [email protected]

ArchiveGrid

- ArchiveGrid ArchiveGrid contains the descriptions of nearly one million archival collections held in archives around the world.

- << Previous: Find Information on Rescuers

- Next: Find Legal Material >>

- Last Updated: Jan 25, 2023 1:44 PM

- URL: https://libguides.gwu.edu/holocaust

What are you looking for?

Joel Citron, chair of the USC Shoah Foundation Board of Councilors; USC President Carol Folt; USC Life Trustee Steven Spielberg; and Holocaust survivor Celina Biniaz (from left) attend the presentation of the University Medallion to the survivors who have shared their stories with the foundation. (USC Photo/Sydney Livingston)

University Medallion recognizes Holocaust survivors who entrusted testimonies to USC Shoah Foundation

USC Life Trustee Steven Spielberg created the foundation three decades ago to preserve the stories of genocide survivors.

For nearly five decades, Celina Biniaz didn’t speak about her experiences during the Holocaust — even with her children. As a girl, Biniaz survived the Krakow Ghetto, the Plaszow concentration camp and the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp before she and her family were saved by German businessman Oskar Schindler when Biniaz was 13.

But after seeing Steven Spielberg’s 1993 film Schindler’s List — which tells the story of how Schindler rescued more than 1,000 Jews from death in concentration camps — Biniaz was inspired to come forward to share her eyewitness account of the Holocaust and experiences as one of the youngest people on that list.

This week, 92-year-old Biniaz linked arms with Spielberg to accept USC’s highest honor, the University Medallion, from USC President Carol Folt on behalf of all the survivors whose testimonies have been preserved by USC Shoah Foundation — The Institute for Visual History and Education, which Spielberg established in 1994.

“I believe the human voice speaks louder than history books,” Biniaz said. “We must always remember the power each individual has to transform the lives of others.”