Importance of staying up-to-date in Research topics

It’s vital to stay current in your field of Research to ensure that your study fits into the larger context of scientific knowledge and prevent duplicating work that’s already been done. Then, because you’re expected to follow those standards, staying on top of ever-changing legal and compliance duties is a business need.

Why is it critical to keep up with the most recent Research?

There are several reasons why it’s critical to stay current with your field of study changes.

Identifying fresh Research opportunities

Understanding the present state of knowledge on a topic, recognizing gaps, and focusing on a meaningful and responsive issue. A thorough literature search can help you find a research topic that is precise enough to be examined in the context of a specific test.

Also, to ensure that you don’t leave any important studies out of your literature review, staying current will assist you in defining your long-term research goals and career trajectory, not just the next topic to concentrate on.

The findings of the Research have an expiration date.

Time is a critical factor in the systematic review process and an important covariate in assessing study heterogeneity and a fundamental determinant of systematic review clinical relevance. Indeed, systematic reviews’ usefulness as a foundation for evidence-based practice depends on proper time considerations.

New Research-based on Previous works

Previous work can help you figure out which methodologies to utilize, what data or resources are already freely available to work with, and what Research limits to solve. Developing beneficial relationships with potential collaborators

As Research entails testing, verifying, and rejecting hypotheses regularly, keeping up with recent publications will assist you in defining building blocks for your study.

Guidance & Confirming that your Research is focused on a new topic

One of the key responsibilities for a doctorate adviser, department head, or field expertise is to advise students on relevant research subjects.

Staying current on literature in your line of work and learning how to do it effectively will help you better support them and guide their research careers. You will not only be assisting them in their career advancements, but you will also be contributing to the improvement of your discipline as a whole.

Observing what your competitors are doing

Research involves many activities. As a researcher, you rely on the information and insights of other researchers to help you understand specific elements of your profession or related disciplines.

How do I stay current with Research Topics?

Keeping upto date may appear daunting at first, but your sources can be divided into two categories: formal and informal. You’ll need to put up mechanisms for the many sources you deem to be relevant if you want to stay on top of newly published and emergent Research .

As your priorities may alter over time, you’ll need to go back and evaluate your notifications from time to time, especially if you’re performing your Research over several months or even years. To track changes in the direction of your original study interest, you have to create new alerts. As a result, keeping up with the Research Topics can help you uncover potential solutions or alternatives to problems you’re having with your study.

Related Posts

Interrogative pronoun – english editing..

The interrogative pronouns are : Who, whom, whose, what, which. They are used in the formation of questions: What is homeopathy? For Scientific english editing and Medical Writing Services visitwww.manuscriptedit.com

Superlative – English editing.

Many adjectives can have three forms: Absolute Comparative Superlative Small smaller smallest Attractive more attractive most attractive The comparative form is used when comparing two items; the superlative is used when there are more than two: She is smaller than her brother. (comparative) The smallest of the three specialist colleges, it has just over 150 […]

Intensifier – English editing.

An adverb that is used to modify an adjective. Intensifiers show how much of a quality something has. For example: A beautiful view. A rather beautiful tropical garden. Extremely beautiful drawings. Intensifiers can also modify other adverbs. For example: Easily Fairly easily Incredibly easily. For Scientific english editing and Medical Writing Services visitwww.manuscriptedit.com

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

Science, health, and public trust.

September 8, 2021

Explaining How Research Works

We’ve heard “follow the science” a lot during the pandemic. But it seems science has taken us on a long and winding road filled with twists and turns, even changing directions at times. That’s led some people to feel they can’t trust science. But when what we know changes, it often means science is working.

Explaining the scientific process may be one way that science communicators can help maintain public trust in science. Placing research in the bigger context of its field and where it fits into the scientific process can help people better understand and interpret new findings as they emerge. A single study usually uncovers only a piece of a larger puzzle.

Questions about how the world works are often investigated on many different levels. For example, scientists can look at the different atoms in a molecule, cells in a tissue, or how different tissues or systems affect each other. Researchers often must choose one or a finite number of ways to investigate a question. It can take many different studies using different approaches to start piecing the whole picture together.

Sometimes it might seem like research results contradict each other. But often, studies are just looking at different aspects of the same problem. Researchers can also investigate a question using different techniques or timeframes. That may lead them to arrive at different conclusions from the same data.

Using the data available at the time of their study, scientists develop different explanations, or models. New information may mean that a novel model needs to be developed to account for it. The models that prevail are those that can withstand the test of time and incorporate new information. Science is a constantly evolving and self-correcting process.

Scientists gain more confidence about a model through the scientific process. They replicate each other’s work. They present at conferences. And papers undergo peer review, in which experts in the field review the work before it can be published in scientific journals. This helps ensure that the study is up to current scientific standards and maintains a level of integrity. Peer reviewers may find problems with the experiments or think different experiments are needed to justify the conclusions. They might even offer new ways to interpret the data.

It’s important for science communicators to consider which stage a study is at in the scientific process when deciding whether to cover it. Some studies are posted on preprint servers for other scientists to start weighing in on and haven’t yet been fully vetted. Results that haven't yet been subjected to scientific scrutiny should be reported on with care and context to avoid confusion or frustration from readers.

We’ve developed a one-page guide, "How Research Works: Understanding the Process of Science" to help communicators put the process of science into perspective. We hope it can serve as a useful resource to help explain why science changes—and why it’s important to expect that change. Please take a look and share your thoughts with us by sending an email to [email protected].

Below are some additional resources:

- Discoveries in Basic Science: A Perfectly Imperfect Process

- When Clinical Research Is in the News

- What is Basic Science and Why is it Important?

- What is a Research Organism?

- What Are Clinical Trials and Studies?

- Basic Research – Digital Media Kit

- Decoding Science: How Does Science Know What It Knows? (NAS)

- Can Science Help People Make Decisions ? (NAS)

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

How recent is recent for good referencing?

Cited articles (i.e., references) in a research paper play a central role in demonstrating the necessity of the research and establishing the validity and significance of the research results.

Therefore, good referencing practices (e.g., citing relevant, critical, and recent research works on the topics) not only increase the quality of the research paper but also facilitate its peer review and availability to the right audience.

Citing or referencing recent articles in the research paper assures reviewers that an extensive literature review was undertaken while writing the paper and information in the paper is up to date. This builds trust between the authors of the paper and the reviewers, which may influence peer review reports.

How old is gold?

All being said, do we exactly know how old a research article can be before it gets the label of not being recent i.e., an old article not good for citing.

There is consensus among scientists and researchers that articles less than five years old are recent publications. However, it may vary from discipline to discipline. For example, researchers in fast-moving fields (e.g., nanotechnology or artificial intelligence) may feel 5-years is too old whereas those in biology may not have the same feeling.

How many recent references make a research paper contemporaneous?

Santini et al. (20018) suggested that if the most recent reference is more than 5 years or so, it can indicate that a full up to date review of the literature has not been undertaken.

However, the suggestion is a weak indicator of the comprehensiveness of the literature review done while writing a paper as it is based on the measure of only one reference.

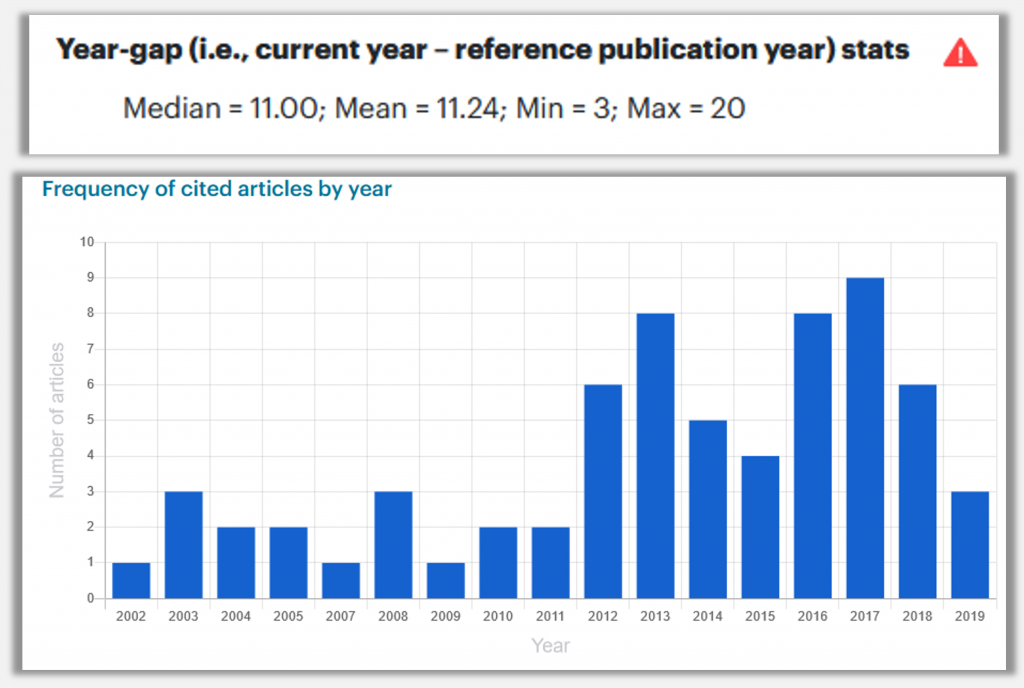

To build a robust understanding of the matter, nXr team analyzed how old references of 69 research papers (published in three highly acclaimed journals: Nature, Science, and Cell) were.

The graph clearly shows that 50% of references in the articles published in highly acclaimed journals are less than 6 years old. This indicates that well-written articles have the characteristic to cite more recent research papers.

How to get similar information for the references in the research paper you are writing?

No worries! When you cite using nXr reference manager and citation tool , nXr automatically creates a dashboard (accessible from your nXr.iLibrary) for the references in your research paper containing various data visualizations.

In one such visualization, you can see the publication year distribution of the references (see below). nXr also gives you an alert if 50% of the references are more than 5 years old so that you can check them.

Stack Exchange Network

Stack Exchange network consists of 183 Q&A communities including Stack Overflow , the largest, most trusted online community for developers to learn, share their knowledge, and build their careers.

Q&A for work

Connect and share knowledge within a single location that is structured and easy to search.

When is it appropriate to describe research as "recent"?

I want to write: "A recent study ..." ,

The particular study I want to cite was published two years ago. I don't think that this is very recent in terms of journal appearances. But it is the most recent I could find compared to similar studies, which is what I want to emphasize.

But what are the general semantics of "recent" when referencing sources?

- 10 If the date of the study matters, why not "A study from 2014...."? – mdd Commented Mar 9, 2016 at 0:44

- 8 It is an ineffective way of saying "This is important!" As a reviewer I would probably tolerate descriptions of anything from the past ten years as "recent." – Anonymous Physicist Commented Mar 9, 2016 at 1:32

- 3 In my mind recent is anything that is new enough that it hasn't been fully absorbed (worked its way into later research, publications and into people's minds). That might depend on recent to whom -- a 20 year-old mathematical theory might well be too recent to have fully worked its way into engineering practice, so if you're writing to the engineering audience it could be appropriate to call it recent. – Owen Commented Mar 9, 2016 at 3:40

- 4 Redundancy is not a bad thing in academic writing. – Dirk Commented Mar 9, 2016 at 5:23

- 4 Keep in mind that recent to you may not be recent to a future reader. If you have something more specific to convey ("most recent at the time of writing", "unsettled", "currently the hip and trendy thing that gets grants"), you'd be best served being more specific. Otherwise, your reader will have to look at your paper's publication date and try to work out what you meant from context. – Jeffrey Bosboom Commented Mar 9, 2016 at 10:26

4 Answers 4

Good question. The semantics of the word "recent", in general, and in academic writing, in particular, is not clearly defined (that is, fuzzy), which makes its practical use quite tricky, as evidenced by your question.

While @vonbrand's answer offers some valuable insights, such as considering the fluidity of a particular scientific field or domain, I would suggest a more practical solution to this problem, as follows. Consider literature that you reference in a particular paper. What is the temporal range of the sources? I think that this aspect could guide you in to where the word "recent" is appropriate and where not so much.

For example, if you cite sources from the current century as well as 1930s, then a paper from 2010 should be considered recent, but not one from 1950. If, on the other hand, your temporal range of references is rather narrow, say, recent 20 years, then you should refer to as "recent" for sources that are from approximately last 4-5 years. You can come up with your own rule of thumb (10-20% of the total range sounds pretty reasonable). The most important aspect would be not the actual value (for the rule of thumb), but rather your consistency in applying it throughout the paper.

- @thrau: My pleasure! Thank you for kind words and accepting. – Aleksandr Blekh Commented Mar 10, 2016 at 20:45

It depends on the area. If you are talking about slow moving areas, "recent" could be a decade ago; for something that moves fast, what was published last year is old hat.

Perhaps the easiest way out is to be more specific, "a study three years back..." (besides, the study might be several years back, or be a decade long study, but the journal issue just came out, so the publication date isn't necessarily telling).

As previously mentioned, the meaning of 'recent' depends on the topic of study. What is considered recent in mathematics may not be considered recent enough for computer science. My computer science professors have generally stuck with anything five years old as being the 'oldest' an article can be. Two to three years is generally better, especially in the tech field as things progress at a much higher rate. A good thing to look out for is when an article might pass the 5 year mark, someone will most likely have adapted the methodology or research findings in a more recent article. Best of luck!

It depends.

If you refer to something that has a precise date, you should be precise. I see no advantage in writing "A recent study showed..." over "The study X from 2010 showed..." The latter contains more information and reads as least as good (in my opinion even better, because it's more precise). A similar case is "The problem posed by X at the meeting Y in 2010..." (better than "The recently posed problem...").

One case in which "recent" could make sense is "The field X has attracted much attention recently" because usually one can not pin down an exact date for this event. However, in most cases this reads more like a self-perpetuating empty statement (if there is a simple reason why the reader should care about the field X then give that!). I have to admit that I myself also wrote sentences like this, but looking back it reads a bit weird. Nowadays, if I read "this field has attracted much attention recently" I really read that the authors do not know a good reason why their problem is interesting but feel that they should.

- On a slightly related note, how would you feel about "This field has attracted much attention recently because reasons "? – svavil Commented Mar 9, 2016 at 22:40

- I would say, the more precise the better. Probably in such a sentence just giving the reason that you feel that make the field exciting is enough. The additional information that these exciting facts resulted in "much attention recently" seems not so important. I would find it even better if the sentence would tell that the field is relevant and not that its fancy right now. – Dirk Commented Mar 10, 2016 at 10:51

You must log in to answer this question.

Not the answer you're looking for browse other questions tagged citations ..

- Featured on Meta

- Announcing a change to the data-dump process

- Upcoming initiatives on Stack Overflow and across the Stack Exchange network...

- We spent a sprint addressing your requests — here’s how it went

Hot Network Questions

- How to request for a package to be added to the Fedora repositories?

- Could today's flash memory be used instead of RAM in 1980s 8 bit machines?

- The book where someone can serve a sentence in advance

- How do cables and cooling lines transverse the pressure hull of the International Space Station?

- Can loops/cycles (in a temporal sense) exist without beginnings?

- Introducing a fixed number of random substitutions in a sequence

- Is increasing Average Product(AP) always implying increasing Marginal Product(MP) in microeconomics?

- What was the Night in Genesis 1?

- How should I run cable across a steel beam?

- Why does "They be naked" use the base form of "be"?

- How could double damage be explained in-universe?

- Jellium Hamiltonian in the thermodynamic limit

- What are the ways compilers recognize complex patterns?

- Holding *west* on the 090 radial?

- Purpose of Green/Orange switch on old flash unit

- Parking ticket for parking in a private lot reserved for customers of X, Y, and Z business's

- Why do protocol developers work on maximizing miner revenue?

- How can a Warlock learn Magic Missile?

- How can I insert new arguments to this block of function calls that follow a pattern?

- Domestic Air Travel within the US with Limited Term Driver's License and no passport, for non-resident aliens?

- How could warfare be kept using pike and shot like tactics for 700 years?

- How accurate does the ISS's velocity and altitude need to be to maintain orbit?

- Welch t-test p-values are poorly calibrated for N=2 samples

- Was supposed to be co-signer on auto for daughter but I’m listed the buyer

More From Forbes

The role of research at universities: why it matters.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

(Photo by William B. Plowman/Getty Images)

Teaching and learning, research and discovery, synthesis and creativity, understanding and engagement, service and outreach. There are many “core elements” to the mission of a great university. Teaching would seem the most obvious, but for those outside of the university, “research” (taken to include scientific research, scholarship more broadly, as well as creative activity) may be the least well understood. This creates misunderstanding of how universities invest resources, especially those deriving from undergraduate tuition and state (or other public) support, and the misperception that those resources are being diverted away from what is believed should be the core (and sole) focus, teaching. This has led to a loss of trust, confidence, and willingness to continue to invest or otherwise support (especially our public) universities.

Why are universities engaged in the conduct of research? Who pays? Who benefits? And why does it all matter? Good questions. Let’s get to some straightforward answers. Because the academic research enterprise really is not that difficult to explain, and its impacts are profound.

So let’s demystify university-based research. And in doing so, hopefully we can begin building both better understanding and a better relationship between the public and higher education, both of which are essential to the future of US higher education.

Why are universities engaged in the conduct of research?

Universities engage in research as part of their missions around learning and discovery. This, in turn, contributes directly and indirectly to their primary mission of teaching. Universities and many colleges (the exception being those dedicated exclusively to undergraduate teaching) have as part of their mission the pursuit of scholarship. This can come in the form of fundamental or applied research (both are most common in the STEM fields, broadly defined), research-based scholarship or what often is called “scholarly activity” (most common in the social sciences and humanities), or creative activity (most common in the arts). Increasingly, these simple categorizations are being blurred, for all good reasons and to the good of the discovery of new knowledge and greater understanding of complex (transdisciplinary) challenges and the creation of increasingly interrelated fields needed to address them.

It goes without saying that the advancement of knowledge (discovery, innovation, creation) is essential to any civilization. Our nation’s research universities represent some of the most concentrated communities of scholars, facilities, and collective expertise engaged in these activities. But more importantly, this is where higher education is delivered, where students develop breadth and depth of knowledge in foundational and advanced subjects, where the skills for knowledge acquisition and understanding (including contextualization, interpretation, and inference) are honed, and where students are educated, trained, and otherwise prepared for successful careers. Part of that training and preparation derives from exposure to faculty who are engaged at the leading-edge of their fields, through their research and scholarly work. The best faculty, the teacher-scholars, seamlessly weave their teaching and research efforts together, to their mutual benefit, and in a way that excites and engages their students. In this way, the next generation of scholars (academic or otherwise) is trained, research and discovery continue to advance inter-generationally, and the cycle is perpetuated.

Best High-Yield Savings Accounts Of 2024

Best 5% interest savings accounts of 2024.

University research can be expensive, particularly in laboratory-intensive fields. But the responsibility for much (indeed most) of the cost of conducting research falls to the faculty member. Faculty who are engaged in research write grants for funding (e.g., from federal and state agencies, foundations, and private companies) to support their work and the work of their students and staff. In some cases, the universities do need to invest heavily in equipment, facilities, and personnel to support select research activities. But they do so judiciously, with an eye toward both their mission, their strategic priorities, and their available resources.

Medical research, and medical education more broadly, is expensive and often requires substantial institutional investment beyond what can be covered by clinical operations or externally funded research. But universities with medical schools/medical centers have determined that the value to their educational and training missions as well as to their communities justifies the investment. And most would agree that university-based medical centers are of significant value to their communities, often providing best-in-class treatment and care in midsize and smaller communities at a level more often seen in larger metropolitan areas.

Research in the STEM fields (broadly defined) can also be expensive. Scientific (including medical) and engineering research often involves specialized facilities or pieces of equipment, advanced computing capabilities, materials requiring controlled handling and storage, and so forth. But much of this work is funded, in large part, by federal agencies such as the National Science Foundation, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Energy, US Department of Agriculture, and many others.

Research in the social sciences is often (not always) less expensive, requiring smaller amount of grant funding. As mentioned previously, however, it is now becoming common to have physical, natural, and social scientist teams pursuing large grant funding. This is an exciting and very promising trend for many reasons, not the least of which is the nature of the complex problems being studied.

Research in the arts and humanities typically requires the least amount of funding as it rarely requires the expensive items listed previously. Funding from such organizations as the National Endowment for the Arts, National Endowment for the Humanities, and private foundations may be able to support significant scholarship and creation of new knowledge or works through much more modest grants than would be required in the natural or physical sciences, for example.

Philanthropy may also be directed toward the support of research and scholarly activity at universities. Support from individual donors, family foundations, private or corporate foundations may be directed to support students, faculty, labs or other facilities, research programs, galleries, centers, and institutes.

Who benefits?

Students, both undergraduate and graduate, benefit from studying in an environment rich with research and discovery. Besides what the faculty can bring back to the classroom, there are opportunities to engage with faculty as part of their research teams and even conduct independent research under their supervision, often for credit. There are opportunities to learn about and learn on state-of-the-art equipment, in state-of-the-art laboratories, and from those working on the leading edge in a discipline. There are opportunities to co-author, present at conferences, make important connections, and explore post-graduate pathways.

The broader university benefits from active research programs. Research on timely and important topics attracts attention, which in turn leads to greater institutional visibility and reputation. As a university becomes known for its research in certain fields, they become magnets for students, faculty, grants, media coverage, and even philanthropy. Strength in research helps to define a university’s “brand” in the national and international marketplace, impacting everything from student recruitment, to faculty retention, to attracting new investments.

The community, region, and state benefits from the research activity of the university. This is especially true for public research universities. Research also contributes directly to economic development, clinical, commercial, and business opportunities. Resources brought into the university through grants and contracts support faculty, staff, and student salaries, often adding additional jobs, contributing directly to the tax base. Research universities, through their expertise, reputation, and facilities, can attract new businesses into their communities or states. They can also launch and incubate startup companies, or license and sell their technologies to other companies. Research universities often host meeting and conferences which creates revenue for local hotels, restaurants, event centers, and more. And as mentioned previously, university medical centers provide high-quality medical care, often in midsize communities that wouldn’t otherwise have such outstanding services and state-of-the-art facilities.

(Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

And finally, why does this all matter?

Research is essential to advancing society, strengthening the economy, driving innovation, and addressing the vexing and challenging problems we face as a people, place, and planet. It’s through research, scholarship, and discovery that we learn about our history and ourselves, understand the present context in which we live, and plan for and secure our future.

Research universities are vibrant, exciting, and inspiring places to learn and to work. They offer opportunities for students that few other institutions can match – whether small liberal arts colleges, mid-size teaching universities, or community colleges – and while not right for every learner or every educator, they are right for many, if not most. The advantages simply cannot be ignored. Neither can the importance or the need for these institutions. They need not be for everyone, and everyone need not find their way to study or work at our research universities, and we stipulate that there are many outstanding options to meet and support different learning styles and provide different environments for teaching and learning. But it’s critically important that we continue to support, protect, and respect research universities for all they do for their students, their communities and states, our standing in the global scientific community, our economy, and our nation.

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

Join The Conversation

One Community. Many Voices. Create a free account to share your thoughts.

Forbes Community Guidelines

Our community is about connecting people through open and thoughtful conversations. We want our readers to share their views and exchange ideas and facts in a safe space.

In order to do so, please follow the posting rules in our site's Terms of Service. We've summarized some of those key rules below. Simply put, keep it civil.

Your post will be rejected if we notice that it seems to contain:

- False or intentionally out-of-context or misleading information

- Insults, profanity, incoherent, obscene or inflammatory language or threats of any kind

- Attacks on the identity of other commenters or the article's author

- Content that otherwise violates our site's terms.

User accounts will be blocked if we notice or believe that users are engaged in:

- Continuous attempts to re-post comments that have been previously moderated/rejected

- Racist, sexist, homophobic or other discriminatory comments

- Attempts or tactics that put the site security at risk

- Actions that otherwise violate our site's terms.

So, how can you be a power user?

- Stay on topic and share your insights

- Feel free to be clear and thoughtful to get your point across

- ‘Like’ or ‘Dislike’ to show your point of view.

- Protect your community.

- Use the report tool to alert us when someone breaks the rules.

Thanks for reading our community guidelines. Please read the full list of posting rules found in our site's Terms of Service.

When is the evidence too old?

A few weeks ago, when submitting an abstract to a nursing conference, I was suddenly faced with a dilemma about age. Not my own age, but the age of evidence I was using to support my work. One key element of the submission criteria was to provide five research citations to support the abstract, and all citations were to be less than ten years old. This requirement left me stumped for a while. The research I wanted to cite was more than ten years old, yet it was excellent research within a very small body of work on the topic. Suddenly I struggled to meet the criteria and almost gave up on the submission, thinking my abstract would not tick all of the boxes if I used research now deemed to be ‘out of date’. I suddenly thought about all of the work I had published more than ten years ago – all that hard work past its use-by date.

Way back in the mid 1990s, a colleague and I started to have conversations with Australian nurses about the importance of evidence based practice (EBP) for the future of Australian nursing. The movement away from the comfort of ‘ritual and routine’ to the uncertainty of EBP was challenging. At the time we described EBP according to the principle that “all interventions should be based on the best currently available scientific evidence” 1 . We had embraced the ideas of authors such as Ian Chalmers 2 and were keen to educate nurses and nursing students about “practices that had been clearly shown to work and question practices for which no evidence exists and discard those which have been shown to do harm” 1 It was very much about the importance of using the most ‘robust’ and ‘reliable’ evidence that we had available to guide us in clinical decision making, taking into account individual patients at the centre of care. It was also about teaching nurses and nursing students about how to ask the right questions, where to look for answers and how to recognize when you have found the right answer to support individualized patient care.

Definitions of evidence-based practice are quite varied and I have heard nurses talk about using “current best evidence” while others use the “most current evidence”. These are quite different approaches, with the latter statement suggesting that more recent is best. This is sometimes reinforced in nursing education, where students are graded according to the use of recent research, with limitations placed on the age of resources used to support their work. However, I wonder if we are losing something in this translation about the meaning of ‘best evidence’ to support care. When does the published evidence get too old and where do we draw the line and stop reading research from our past?

Personally I have always expected my students to use up to date research when supporting their recommendations for care. However, I have also encouraged them to look back to see where the new research has come from and to acknowledge the foundation it has been built on. I am always keen to hear about the latest developments in healthcare and work to support the readers of EBN who need and want to know about what is new and important in the health care literature. Keeping up to date with new evidence is critically important for change. But I wonder how we strike a balance between absorbing recent research and taking into account robust research that preceded its publication by more than a decade?

So, let’s think about these ideas for a minute. If we put our blinkers on and ignore important research from the recently ‘outdated’ literature from the 1990s (when I first became interested in doing research), we could miss some important foundational work that still influences practice today. The two references I have used below, both from the 1990s, would not be included in the discussion at all. If we only consider literature that is recent, and value that more highly than if it is robust, then we will be missing important evidence to inform practice. Researchers could start asking the same research questions over and over (I have seen some of this already in nursing literature) and even feel pressured to repeat previous studies all over again to check if the findings still hold true in the contemporary world. Perhaps that is something to watch for in the future.

It is important to keep up to date with current research findings, new innovations in care, recent trends in patient problems, trends in patient outcomes and changes in the social, political and system context of the care we provide. But it is also important to look back as we move forward, thinking about the strength of the evidence as well as its age.

Allison Shorten RN RM PhD

Yale University School of Nursing

References:

- Shorten A. & Wallace MC. ‘Evidence-based practice – The future is clear’. Australian Nurses Journal, 1996, Vol. 4, No. 6, pp. 22-24.

- Chalmers I. The Cochrane collaboration: Preparing, maintaining, and disseminating systematic reviews of the effects of health care, Annals New York Academy of Science, 1993, Vol. 703, pp. 156-165.

Comment and Opinion | Open Debate

The views and opinions expressed on this site are solely those of the original authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of BMJ and should not be used to replace medical advice. Please see our full website terms and conditions .

All BMJ blog posts are posted under a CC-BY-NC licence

BMJ Journals

The “outdated sources” myth

- In-Text Citations

- Reference List

- Research and Publication

In this series, we will look at common APA Style misconceptions and debunk these myths one by one.

We often receive questions about whether sources must have been published within a certain time frame to be cited in a scholarly paper. Many writers incorrectly believe in the “outdated sources” myth, which is that sources must have been published recently, such as the last 5 to 10 years.

However, there is no timeliness requirement in APA Style guidelines (as defined in the Concise Guide to APA Style, Seventh Edition and Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, Seventh Edition ). Properly citing relevant sources is a key task for writers of any APA Style paper. You should “cite the work of those individuals whose ideas, theories, or research have directly influenced your work. The works you cite provide key background information, support or dispute your thesis, or offer critical definitions and data” (American Psychological Association, 2020, p. 253). We recommend citing reliable, primary sources with the most current information whenever possible.

What it means to be “timely” varies across fields or disciplines. Seminal research articles and/or foundational books can remain relevant for a long time and help establish the context for a given paper. For example, Albert Bandura’s Bobo doll experiment (Bandura et al., 1961) is often cited in contemporary social and child psychology articles. Remember, APA Style has no year-related cutoff.

As always, defer to your instructor’s guidelines when writing student papers. For example, your instructor may require sources be published within a certain timeframe for student papers. If so, follow that guideline for work in that class. Similarly, consider the discipline and audience for whom you are writing. For example, if you are submitting an article to a journal in a fast-developing field like neuroscience, more recent sources—if relevant and important for your readers to consider in the context of your paper—might make your article more competitive.

Now that we’ve debunked another myth, go forth APA Style writers, and cite noteworthy and relevant sources!

What myth should we debunk next? Leave a comment below.

American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1037/0000165-000

Bandura, A., Ross, D., & Ross, S. A. (1961). Transmission of aggression through imitation of aggressive models. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology , 63 (3), 575–582. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0045925

Related and recent

Comments are disabled due to your privacy settings. To re-enable, please adjust your cookie preferences.

APA Style Monthly

Subscribe to the APA Style Monthly newsletter to get tips, updates, and resources delivered directly to your inbox.

Welcome! Thank you for subscribing.

APA Style Guidelines

Browse APA Style writing guidelines by category

- Abbreviations

- Bias-Free Language

- Capitalization

- Italics and Quotation Marks

- Paper Format

- Punctuation

- Spelling and Hyphenation

- Tables and Figures

Full index of topics

Cookies on the NHS England website

We’ve put some small files called cookies on your device to make our site work.

We’d also like to use analytics cookies. These send information about how our site is used to a service called Google Analytics. We use this information to improve our site.

Let us know if this is OK. We’ll use a cookie to save your choice. You can read more about our cookies before you choose.

Change my preferences I'm OK with analytics cookies

Maximising the benefits of research: Guidance for integrated care systems

England has a vibrant research and development ecosystem, with well-developed research infrastructure and research expertise within our health and care workforce. The value of research in transforming health and care is significant; additionally, staff satisfaction, recruitment and retention is higher among staff who are involved in research. The inception of integrated care systems (ICSs) provides the opportunity for systems to embed research within health and care for the benefit of our population. Supporting this opportunity, a clear research thread runs through ICS strategies and plans, from joint strategic needs assessments and joint health and wellbeing strategies , integrated care strategies , joint forwards plans , integrated care board (ICB) annual reports and the assessment by NHS England of the discharge of duties by ICBs.

The Health and Care Act 2022 (the 2022 Act) sets new legal duties on ICBs around the facilitation and promotion of research in matters relevant to the health service, and the use in the health service of evidence obtained from research. NHS England will assess ICBs for their discharge of these duties. The ICS design framework sets the expectation that in arranging provision of health services, ICBs will facilitate their partners in the health and care system to work together, combining expertise and resources to foster and deploy research and innovations. This guidance supports ICBs in fulfilling their research duties.

ICSs are encouraged to develop a research strategy that aligns to or could be included in their integrated care strategy. This strategy will enable the unification of research across ICS partners, and be consistently embedded to:

- identify and address local research priorities and needs, and work collaboratively to address national research priorities

- improve the quality of health and care and outcomes for all through the evidence generated by research

- increase the quality, quantity and breadth of research undertaken locally

- extend and expand research in settings such as primary care, community care, mental health services, public health and social care

- drive the use of research evidence for quality improvement and evidence-based practice

- influence the national research agenda to better meet local priorities and needs

- improve co-ordination and standardisation within and between localities for the set up and delivery of research

- harness the patient and economic benefits of commercial contract research

- co-ordinate and develop the research workforce across all settings.

1. Introduction

This guidance sets out what good research practice looks like. It supports integrated care systems (ICSs) to maximise the value of their duties around research for the benefit of their population’s health and care and, through co-ordination across ICSs, for national and international impact. It supports integrated care boards (ICBs), integrated care partnerships (ICPs) and their partners to develop a research strategy that aligns to or can be incorporated into their integrated care strategy, and helps them and their workforce to build on existing research initiatives and activities across health and social care to improve sector-wide performance and best practice

- explains the ICB legal duties and other requirements around research and the use of evidence from research, and that research is included in forward planning and reporting

- encourages system leaders to develop a footprint-wide research strategy that aligns to local and national research priorities, develops and supports their workforce, takes the opportunities offered by commercial research and includes plans to embed research in their system’s governance and leadership

- identifies best practice examples and other resources that ICBs may find useful as they develop their research strategies.

This guidance provides comprehensive information for use by:

- those with senior responsibility, including at board level, for research strategy development and/or operationalising research

- managers responsible for developing joint strategic needs assessments, integrated care strategies, joint health and wellbeing strategies, joint forward plans, other linked strategies, or reporting on ICB activities

- research managers

- research and development/innovation leads

- heads of services

- knowledge and library specialists.

It may also be useful to individuals involved in research, education, and partner organisations such as local authorities, social care services, the voluntary, community and social enterprise sector (VCSE) and other providers of healthcare services.

NHS England provides guidance on embedding research in the NHS and secure data environments, and the Office for Life Sciences (OLS ) champions research, innovation and the use of technology to transform health and care service. Other sources of guidance, support and information are signposted in this guidance to support ICSs in aligning to national visions, strategies and plans around research.

1.1 Definition of research

NHS England uses the UK Policy Framework for Health and Social Care Research definition of research:

“… the attempt to derive generalisable or transferable new knowledge to answer or refine relevant questions with scientifically sound methods. This excludes audits of practice and service evaluation. It includes activities that are carried out in preparation for or as a consequence of the interventional part of the research, such as screening potential participants for eligibility, obtaining participants’ consent and publishing results. It also includes non-interventional health and social care research (that is, projects that do not involve any change in standard treatment, care, or other services), projects that aim to generate hypotheses, methodological research and descriptive research”.

This broad definition encompasses the range of types of research:

- clinical trials and other clinical investigations into the safety and effectiveness of medicines, devices and health technologies

- public health research

- observational studies

- discovery science and experimental medicine

- translational research in which results from basic research are developed into results that directly benefit people

- applied research

- research to support policy-making and commissioning

- social care research and research in social care settings

- research into NHS services and care pathways.

1.2 Why research is important

The UK is a world leader for research and invention in healthcare, with around 25% of the world’s top 100 prescription medicines being discovered and developed in the UK ( The impact of collaboration: The value of UK medical research to EU science and health ). Research in the health and care system is important because it underpins all advances in health and care and is the basis for evidence-based practice. Engaging clinicians and healthcare organisations in research is associated with improvements in delivery of healthcare ( Does the engagement of clinicians and organisations in research improve healthcare performance: a three-stage review) . To benefit service users and the public, the NHS and local government, and achieve return on investment, it is vital that research is disseminated, shared and translated into practice.

The National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) is funded by the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) to transform research in the health and social care system, including through support for NHS research. Research led to the first proven treatments for Covid, for example the use of dexamethasone, estimated to have saved over a million lives worldwide . This success was in part due to how research is undertaken in the unique environment of the NHS, innovative trial designs, the support provided by the NIHR, frontline staff enabling research, and the awareness and readiness of the public to support research. We need to learn from these and other successes, and translate this across all health and care settings. ICSs will play a vital role in enabling research to be embedded in evolving patient pathways across their footprints.

Example: PRINCIPLE trial – finding treatments for Covid recovery at home

The Platform Randomised Trial of Treatment in the Community for Epidemic and Pandemic Illnesses (PRINCIPLE) was a UK-wide, clinical study to find Covid treatments for recovery at home without the need to attend hospital. The study was open to all with ongoing Covid symptoms, registration was easy, and the trial was run entirely remotely by delivering ‘participant packs’ to people’s homes. It was one of the first trials in the world to show that azithromycin and doxycycline did not benefit patients with Covid and to identify the effectiveness of a commonly used drug – inhaled budesonide –in reducing time to recovery.

The PRINCIPLE study team demonstrated the integral role that primary, secondary and ambulatory care staff can play in the delivery of studies. Local collaborators were trained in good clinical practice to allow them to assess and confirm the eligibility of potential participants, and were commended specifically for their use of patient data to contact people soon after they received a positive test result. It is this network of local staff contributing to research within their healthcare setting that has enabled over 10,000 people to be recruited onto this study so far – one of the largest at home Covid treatment studies worldwide.

This is an example of a study design that incorporates the vital contributions of healthcare providers across the system.

Policy-makers and commissioners need evidence to support their decision-making around the delivery and system-wide transformation of health and care services, including how health inequalities will be reduced.

There is also evidence that:

- staff involved in research have greater job satisfaction and staff turnover is lower in research active trusts ( Academic factors in medical recruitment: evidence to support improvements in medical recruitment and retention by improving the academic content in medical posts)

- research active hospitals have lower mortality rates, and not just among research participants ( Research activity and the association with mortality )

- 83% of people believe that health research is very important ( Survey of the general public: attitudes towards health research)

- healthcare performance improvements have been seen from the creation of academic research placements ( Experiences of hospital allied health professionals in collaborative student research projects: a qualitative study )

- clinical academic research, and in particular the practice changes resulting from it, is associated with improved patient and carer experiences ( A qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis exploring the impacts of clinical academic activity by healthcare professionals outside medicine ).

Key to having research embedded in health and care is having staff who can understand, undertake, use and generate new research, and share actionable research finding as part of a pro-research culture. Education and training are therefore critical for research to be sustainably embedded within health and care, and for people to develop careers in research and support it in their clinical or care roles.

DHSC, NHS England, the devolved administrations, NIHR and other partners expect to publish a clinical research workforce strategy in 2023/24 to help the UK realise the national clinical research vision outlined in Saving and Improving Lives: The Future of UK Clinical Research Delivery and deliver the Life Sciences Vision to see research embedded in the NHS as part of health and care pathways.

Research will support ICSs to deliver on their four key aims:

Improving outcomes

The NHS 2023/34 priorities and operational planning guidance emphasises the importance of research in improving patient care, outcomes and experience.

Research evidence will inform commissioning decisions to improve experience and outcomes. Research activities should align with the local health priorities identified through local joint strategic needs assessments, and may be best designed and delivered by collaborating with partners. Research priorities may be best addressed by collaborating with partners nationally to design and deliver research.

Tackling inequalities

Research can give a better understanding of local populations and the wider determinants of health, and with this the steps to maintain health and narrow health inequalities.

Enhancing productivity

The development of ICSs creates the opportunity to consider research delivery within the ICS and across ICS boundaries, increasing flexibility of workforce or recruitment while reducing bureaucracy and improving research productivity and value for money.

Supporting social and economic development

An active research ecosystem working in a co-ordinated way and to national standards brings revenue and jobs to regions. The NIHR Clinical Research Network (CRN) supports service users, the public and health and care organisations across England to participate in high-quality research. The 2019 impact and value report detailed the significant income and cost savings that commercial research generates for NHS trusts. Between 2016/17 and 2018/19 the NHS received on average £9,000 per patient recruited to a commercial clinical trial and saved over £5,800 in drug costs for each of these patients. This equates to income of £355 million and cost savings of £26.8 million in 2018/19.

In 2021 150 members of the Association of Medical Research Charities funded £1.55 billion of medical research, including the salaries of 20,000 researchers. Every £1 million spent by charities on medical research in the UK contributes £1.83 million to the economy.

Example: Research that cut problematic prescribing and generated cost savings in general practice – a local health priority

Analysis of routine patient data identified the need for strategies targeting clinicians and patients to curb rising opioid prescribing. From this, the Campaign to Reduce Opioid Prescription (CROP) was launched in 2016, urging GPs across West Yorkshire to ‘think-twice’ before prescribing opioids. This promoted the NICE guidance on chronic pain , which recommends reducing the use of opioids because there is little or no evidence that they make any difference to people’s quality of life, pain or psychological distress, but they can cause harm, including possible addiction.

Over a year 15,000 fewer people were prescribed opioids (a 5.63% relative reduction), a net saving to the NHS of £700,000. The biggest reduction was in people aged over 75, who are at higher risk of opioid-related falls and death, and there was no compensatory rise in the prescribing of other painkillers or referrals to musculoskeletal services.

The CROP campaign, led by researchers at the University of Leeds, has subsequently been rolled out across all ICBs in Yorkshire and the Humber, and the North East and North Cumbria ICB, and the 1,045 practices to which it has been delivered are reporting results similar to the above.

Foy R, Leaman B, McCrorie C, Petty D, House A, Bennett M, et al (2016) Prescribed opioids in primary care: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses of influence of patient and practice characteristics | BMJ Open 69(5).

Alderson SL, Faragher TM, Willis TA, Carder P, Johnson S, Foy R (2021) The effects of an evidence- and theory-informed feedback intervention on opioid prescribing for non-cancer pain in primary care: A controlled interrupted time series analysis. PLOS Med .

2. ICS, ICP and ICB responsibilities and requirements

ICBs have legal duties and other requirements that relate to research. These are additional to the duties and responsibilities of individual providers within ICS footprints. This section sets out what these duties mean in practical terms and gives examples of how to meet them.

2.1 Legal duties relating to research in the Health and Care Act 2022

Part 1 of the 2022 Act includes specific legal duties for ICBs and NHS England in respect of research. In the Explanatory Notes to the 2022 Act, government sets out how ICBs could discharge their research duty.

Duty to facilitate or otherwise promote research

The ICB duty builds on the previous clinical commissioning group (CCG) duty to promote research, by requiring each ICB, in the exercise of its functions, to facilitate or otherwise promote research on matters relevant to the health service. This duty is intended to include a range of activities to enable research. Section 3 of this guidance outlines ways in which ICBs can do this.

The NHS Constitution also makes clear that patients should be enabled to take part in research: “the NHS pledges … to inform you of research studies in which you may be eligible to participate”.

The Provider Selection Regime (PSR) will be a new set of rules for arranging healthcare services in England, introduced by regulations made under the 2022 Act. The research component should be referred to once the PSR is published.

Duty to facilitate or otherwise promote the use in the health service of evidence obtained from research

This duty similarly builds on the CCG requirement to promote the use of evidence. ICBs must, in the exercise of their functions, facilitate or otherwise promote the use in the health service of evidence obtained from research. For example, ICBs should facilitate or otherwise promote the use of evidence in care, clinical and commissioning decisions.

Duty for ICSs to include research in their joint forward plans and annual reports

Joint forward plans are five-year plans developed by ICBs and their partner NHS trusts and foundation trusts. Systems are encouraged to use the joint forward plan as a shared delivery plan for the integrated care strategy and joint health and wellbeing strategy, aligned to the NHS’s universal commitments. The plan must explain how the ICB will discharge its duties around research, and the ICB must report on the discharge of its research duties in its annual report. These inclusions will raise the profile of research at board level and help embed research as a business-as-usual activity.

The joint forward plan and NHS Oversight Framework guidance set the minimum requirements for what needs to be included in plans and reports.

NHS England duty to include how each ICB is carrying out its duties relating to research in its annual performance assessment of each ICB

NHS England has a new legal duty to annually assess the performance of each ICB and publish a summary of its findings. For 2022/23 NHS England will complete a narrative assessment, identifying areas of good and/or outstanding performance, areas for improvement and any areas that are particularly challenged, drawing on national expertise as required and having regard to relevant guidance. This assessment will include a section considering how effectively the ICB has discharged its duties to facilitate or otherwise promote research and the use of evidence obtained from research.

This, alongside the implementation of the NHS Long Term Plan commitment to develop research metrics for NHS providers, will increase transparency across the system and enable more targeted support for research. Research metrics from NHS England, the Care Quality Commission (CQC) and NIHR will enable the monitoring of progress over time, and are under development with sector colleagues, including providers.

2.2 Legal requirement to work with people and communities

Working with people and communities is a requirement of ICBs, and statutory guidance is available to support them and their partner providers meet this legal duty. A co-ordinated approach across healthcare delivery and research will make it more likely that research reflects what matters to people and communities.

This will also help ICBs to fulfil their legal duty in the 2022 Act to reduce health inequalities in access to health services and the outcomes achieved. Section 3.9 includes links to resources to help guide engagement with underserved communities around research.

The Public Sector Equality Duty also applies and requires equality of opportunities between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not.

2.3 Research governance

While research can address local priorities, it typically operates across ICS boundaries and at national and international levels. Health and social care research is governed by a range of laws, policies, and international, national and professional standards.

The Health Research Authority (HRA ) is responsible for ensuring such regulation is co-ordinated and standardised across the UK to make it easier to do research that people can trust. The HRA is an executive non-departmental public body created by the Care Act 2014 to protect and promote the interests of patients and the public in health and social care research, including by co-ordinating and standardising the practice of research regulation. Local authorities and the NHS are obliged to have regard to its guidance on the management and conduct of research.

Before a research project can start in the NHS in England it must receive approval from the HRA. This includes research taking place in NHS trusts, NHS foundation trusts, ICBs or primary care providers of NHS commissioned services in England, and all research under an NHS duty of care, including that undertaken by NHS staff working in social care or other non-NHS environments.

The HRA schemes indemnify NHS organisations accepting these assurances against any claim covered by the NHS Litigation Authority arising as a result of incorrect assurances. If an NHS organisation duplicates the HRA assessments, it will be liable for any consequences of the decisions it bases on its own checks.

ICBs and partner organisations should have processes for the set up and delivery of research that comply with national laws and systems, and does not duplicate them. Such national systems include confirmation of capacity, National Contract Value Review (NCVR), management of Excess Treatment Costs (ETCs) and contracting arrangements (see section 2.4).

The UK Policy Framework for Health and Social Care sets out the roles and responsibilities of individuals and organisations involved in research.

2.4 Contractual requirements around research

NHS England mandates commissioner use of the NHS Standard Contract for all contracts for healthcare services other than primary care. The contract is updated annually. References to research in the current NHS Standard Contract and service conditions fall into three main areas.

Recruitment of service users and staff into approved research studies

The NHS Standard Contract obliges every provider of NHS-funded services to assist the recruitment of suitable subjects (whether patients or staff) into approved research studies. This requirement aligns to those in the 2022 Act that require ICBs to facilitate or otherwise promote research (see section 2.1). Section 3 considers how this requirement can best be met. Research involving people or their data requires ethical and potentially other approvals (see section 2.3).

National Directive on Commercial Contract Research Studies

Adherence to the National Directive is mandated as part of the NHS Standard Contract. The directive states that providers must:

- Use the unmodified model agreements for sponsor-to-site contracting; HRA and Health and Care Research Wales (HCRW) approval of studies will be dependent on use of these templates.

- Use the standard costing methodology to set prices for commercial contract research undertaken by NHS providers; this is currently in the NIHR interactive costing tool (NIHR iCT).

- Introduce the National Contract Value Review (NCVR) process in line with national rollout. NCVR is a standardised national approach to costing commercial contract research within the NHS. It currently covers acute, specialist and mental health trusts, but the intention is to roll it out to all NHS providers. The creation of ICSs is the ideal opportunity to explore how commercial study set up can be supported across these footprints, reducing the resource needed and time taken.

Comply with HRA/NIHR research reporting guidance

The provider must comply with HRA/NIHR research reporting guidance, as applicable.

2.5 Excess treatment costs

Patients in a research study may receive healthcare that differs from what is standard in the NHS, requires more clinician time or is delivered in a different location. The associated NHS treatment costs may exceed or be less than those of standard treatment. If greater, the difference is referred to as the NHS Excess Treatment Costs (ETCs).

In the case of commercial contract research, the commercial funder will pay the full cost of the study. In the case of non-commercial research, the commissioner of the service in which the study operates is responsible for funding the ETCs.

ICBs as commissioners of services are responsible for ETCs in services that they commission. Guidance for the management of ETCs is available.

DHSC and NIHR are piloting interim arrangements to support non-NHS ETCs for research in public health and social care (non-NHS intervention costs). Please refer to the further detail on the NIHR website .

2.6 Care Quality Commission

The CQC is currently developing its approach for ICS-level assessments, and its new assessment framework will be introduced towards the end of 2023 .

CQC inspection of NHS providers continue, with research assessed as part of the review of the trust-level Well-led framework. Providers are asked:

- Are divisional staff aware of research undertaken in and through the trust, how it contributes to improvement and the service level needed across departments to support it?

- How do senior leaders support internal investigators initiating and managing clinical studies?

- Does the vision and strategy incorporate plans for supporting clinical research activity as a key contributor to best patient care?

- Does the trust have clear internal reporting systems for its research range, volume, activity, safety and performance?

- How are service users and carers given the opportunity to participate in or become actively involved in clinical research studies in the trust?

3. Developing a research strategy

3.1 why develop a research strategy.

Like the health and care system, the research environment is complex. Developing a research strategy will help bring together the legal and other duties around research in a coherent way, and help the ICS understand its local research capability, workforce, activity and needs, set ambitions around research and maximise the benefits associated with commercial research. It will help demonstrate the benefit of research locally, nationally and internationally, and guide the production of clear plans.

Example: Value of research partnerships and integration with ICSs

Bristol Health Partners (BHP) Academic Health Science Centre (AHSC) has a fully integrated relationship as the new Research and Innovation Steering Group for the Bristol, North Somerset and South Gloucestershire (BNSSG) ICS, and reports directly to ICB chief executives.

The group provides the strategic direction and oversight for all research undertaken and delivered across the system. Membership includes directors of research, clinical strategy, public health, social care, senior innovation and education leaders from its core funding partners. It also includes public contributors and senior representatives from primary care, NIHR Applied Research Collaboration West, NIHR CRN West of England, West of England Academic Health Science Network (WEAHSN), Healthier Together ICS, university research institutes and People in Health West of England.

The group has reviewed ICS programmes, identified current and potential research and innovation connections, and begun to establish new connections. It has also supported work with the ICS Ageing Well programme and secured funding for innovative pilots to improve dementia care and increase physical activity for older adults.

Since 2016 BHP has directly contributed an estimated additional £1.1 million to support ICS priorities through Health Integration Team projects and other activities, and has attracted more than £33 million of external research, service redesign and infrastructure into the region.

3.2 General considerations

In developing its research strategy, the ICS may find it helpful to consider these overarching questions alongside the suggested focused content covered in the sections below:

- What do you hope to achieve within a given timeframe?

- Are all the right organisations involved in developing the research strategy?

- How will the health and care workforce be enabled to deliver the research strategy?

- How can research be embedded in existing health and care delivery and pathways?

- What mechanisms are in place to translate actionable research findings into practice and decision-making?

- What inequalities exist in different areas, communities or groups? How will you ensure planning and delivery of research aligns to CORE20plus5 priorities?

- Are you considering equality, diversity and inclusivity and the Public Sector Equality Duty in facilitating and promoting research opportunities for service users and for health and care staff?

- Is the ICS considering the opportunities of developing their commercial research portfolio?

- Is research informing or being informed by population health management?

- How will you plan and deliver research in a sustainable manner, aligning it to the Greener NHS agenda and the ICB’s duties in relation to climate change ?

Buy-in from NHS staff, patients and the public will be vital if ICBs are to discharge their research duties and deliver on their research plans. An important consideration is how to develop sustainable, routine and accessible information flows to ensure the ICB, partners, staff, patients and public can access up-to-date and appropriate information around local research activity, regional, national and international research opportunities and findings, and contact information.

3.3 Leadership and governance across the ICS

Executive leadership.

The Explanatory Notes to the 2022 Act suggest that ICBs have board-level discussions on research activity, the use of the evidence from research, the research workforce and research culture within the ICS. ICSs should refer to the NHS Leadership Competency Framework for board-level leaders at organisation and ICS level for the competencies relating to the research duties of ICSs, once published.

All ICBs are encouraged to have an executive lead responsible for fulfilling the research duties conferred by the 2022 Act. They should help give the ICB a clear understanding of research across the area, regularly reporting on progress towards agreed aims. An executive lead can take responsibility for ensuring clear research ambitions and a research strategy are developed; oversight of organisational research portfolios, diversity in research, alignment to national priorities; promotion of research skills and the need for research skills training; and succession planning.

Senior leaders could engage, consult and be supported by representatives of each registered health and social care professional group when developing strategic plans, and for oversight of training, succession planning, and equality and inclusivity. They could use the capacity and capability of the research and development leads within provider organisations, although established lead roles across social care settings are rare so extra effort may be needed to garner social care research insight.

Research steering group, board or forum

Some CCGs had research steering groups and some of these have expanded with the widening remit of ICBs. ICSs that do not have a such a group should consider adopting a model similar to one in other ICSs where research is effectively embedded in ICS governance structures.

A dedicated steering research group, board and/or forum can:

- provide dedicated time to plan, oversee and report on research

- bring a range of representatives from research infrastructure organisations, patients and the public together with representation from across the ICS, to develop a common aim and objective

- ensure board-level sight of research

- take a cross-ICS approach to research, increasing participation and diversity in research, and reducing bureaucracy.

Example: A dedicated research and innovation subgroup

East and North Hertfordshire Health Care Partnership established a formal research and innovation subgroup to support its objectives to transform services, reduce health inequalities and improve patient health and wellbeing. This subgroup is dedicated to determining and supporting local research priorities and developing an innovation agenda. With effective patient and public involvement, it is working to ensure the local population has access to more research opportunities.

Bringing together the NIHR, academia, industry and local health and care services, the subgroup develops collaborative work plans that support the design, implementation and evaluation of local transformation needs, sharing resources, staff, expertise and facilities. Its work exemplifies a sustainable approach to partnership working and supports Hertfordshire and West Essex ICS’s developing strategy.

HWE ICS Partnership Board 14 September 2021

3.4 Understanding your research activity and working with local and national research infrastructure

Research in NHS and non-NHS settings across an ICS footprint will be supported by different organisations. In some areas networks or collaboratives already exist to bring these organisations together, but in others the links are not as well formed. ICBs would benefit from having a clear map of the research infrastructure and pre-existing local or national investment into research in their area.

It may be valuable to consider:

- Who are the research leaders in your local health and care system, NIHR, higher education institutions, VCSE sector and businesses?

- Are there any pre-existing local or regional research, researcher or research engagement networks?

- What are the opportunities to inform, participate in, collaborate with or lead national and international research efforts in addition to local opportunities?

A list of organisations involved in research including NIHR-funded infrastructure and programmes is included in Annex 1 .

Much of the research undertaken in NHS and other health and care settings is funded though national calls and grants provided by funders such as NIHR, research charities , UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) , including the Medical Research Council (MRC ) and Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) , and is aligned to national priorities. Other research may include national or international commercial or non-commercial clinical trials funders.

Partners within ICS systems can use NIHR research portfolio data to monitor and plan research activity; however, not all research is included within the NIHR’s portfolio, so this will not give a full picture of the research within the footprint. Mechanisms to map and monitor research more widely could be incorporated in ICB research strategies.

Some local needs may best be addressed through public health or social care research rather than research in primary, secondary or tertiary healthcare settings. Public health and social care research are described in Annex 2 .

Example: Mapping health and care research activity, expertise, interests and infrastructure

The Nottingham and Nottinghamshire Integrated Care System Research Partners Group meets bi-monthly and is chaired by the ICB Head of Research and Evidence. It brings together senior managers from the NHS providers, ICB, two local authorities, two universities and the NIHR CRN East Midlands, providing a forum for ICS-wide research discussions and the development of a system-wide collaborative approach to health and care research across the ICS. Among its aims, the group seeks to increase participation in research at both the organisational and population level, enable equity of access to research opportunities and generate impact on health and care pathways.

The group have mapped health and care research activity, expertise, interests and infrastructure in the constituent organisations. With this the ICS can see the research capabilities, strengths, expertise, and areas of synergy and opportunities for future collaboration that align to its needs and priorities, and also gaps for future development, recognising that organisations are at different stages of research development.

3.5 Understanding local needs