- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Problem-Solving Strategies and Obstacles

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Sean is a fact-checker and researcher with experience in sociology, field research, and data analytics.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Sean-Blackburn-1000-a8b2229366944421bc4b2f2ba26a1003.jpg)

JGI / Jamie Grill / Getty Images

- Application

- Improvement

From deciding what to eat for dinner to considering whether it's the right time to buy a house, problem-solving is a large part of our daily lives. Learn some of the problem-solving strategies that exist and how to use them in real life, along with ways to overcome obstacles that are making it harder to resolve the issues you face.

What Is Problem-Solving?

In cognitive psychology , the term 'problem-solving' refers to the mental process that people go through to discover, analyze, and solve problems.

A problem exists when there is a goal that we want to achieve but the process by which we will achieve it is not obvious to us. Put another way, there is something that we want to occur in our life, yet we are not immediately certain how to make it happen.

Maybe you want a better relationship with your spouse or another family member but you're not sure how to improve it. Or you want to start a business but are unsure what steps to take. Problem-solving helps you figure out how to achieve these desires.

The problem-solving process involves:

- Discovery of the problem

- Deciding to tackle the issue

- Seeking to understand the problem more fully

- Researching available options or solutions

- Taking action to resolve the issue

Before problem-solving can occur, it is important to first understand the exact nature of the problem itself. If your understanding of the issue is faulty, your attempts to resolve it will also be incorrect or flawed.

Problem-Solving Mental Processes

Several mental processes are at work during problem-solving. Among them are:

- Perceptually recognizing the problem

- Representing the problem in memory

- Considering relevant information that applies to the problem

- Identifying different aspects of the problem

- Labeling and describing the problem

Problem-Solving Strategies

There are many ways to go about solving a problem. Some of these strategies might be used on their own, or you may decide to employ multiple approaches when working to figure out and fix a problem.

An algorithm is a step-by-step procedure that, by following certain "rules" produces a solution. Algorithms are commonly used in mathematics to solve division or multiplication problems. But they can be used in other fields as well.

In psychology, algorithms can be used to help identify individuals with a greater risk of mental health issues. For instance, research suggests that certain algorithms might help us recognize children with an elevated risk of suicide or self-harm.

One benefit of algorithms is that they guarantee an accurate answer. However, they aren't always the best approach to problem-solving, in part because detecting patterns can be incredibly time-consuming.

There are also concerns when machine learning is involved—also known as artificial intelligence (AI)—such as whether they can accurately predict human behaviors.

Heuristics are shortcut strategies that people can use to solve a problem at hand. These "rule of thumb" approaches allow you to simplify complex problems, reducing the total number of possible solutions to a more manageable set.

If you find yourself sitting in a traffic jam, for example, you may quickly consider other routes, taking one to get moving once again. When shopping for a new car, you might think back to a prior experience when negotiating got you a lower price, then employ the same tactics.

While heuristics may be helpful when facing smaller issues, major decisions shouldn't necessarily be made using a shortcut approach. Heuristics also don't guarantee an effective solution, such as when trying to drive around a traffic jam only to find yourself on an equally crowded route.

Trial and Error

A trial-and-error approach to problem-solving involves trying a number of potential solutions to a particular issue, then ruling out those that do not work. If you're not sure whether to buy a shirt in blue or green, for instance, you may try on each before deciding which one to purchase.

This can be a good strategy to use if you have a limited number of solutions available. But if there are many different choices available, narrowing down the possible options using another problem-solving technique can be helpful before attempting trial and error.

In some cases, the solution to a problem can appear as a sudden insight. You are facing an issue in a relationship or your career when, out of nowhere, the solution appears in your mind and you know exactly what to do.

Insight can occur when the problem in front of you is similar to an issue that you've dealt with in the past. Although, you may not recognize what is occurring since the underlying mental processes that lead to insight often happen outside of conscious awareness .

Research indicates that insight is most likely to occur during times when you are alone—such as when going on a walk by yourself, when you're in the shower, or when lying in bed after waking up.

How to Apply Problem-Solving Strategies in Real Life

If you're facing a problem, you can implement one or more of these strategies to find a potential solution. Here's how to use them in real life:

- Create a flow chart . If you have time, you can take advantage of the algorithm approach to problem-solving by sitting down and making a flow chart of each potential solution, its consequences, and what happens next.

- Recall your past experiences . When a problem needs to be solved fairly quickly, heuristics may be a better approach. Think back to when you faced a similar issue, then use your knowledge and experience to choose the best option possible.

- Start trying potential solutions . If your options are limited, start trying them one by one to see which solution is best for achieving your desired goal. If a particular solution doesn't work, move on to the next.

- Take some time alone . Since insight is often achieved when you're alone, carve out time to be by yourself for a while. The answer to your problem may come to you, seemingly out of the blue, if you spend some time away from others.

Obstacles to Problem-Solving

Problem-solving is not a flawless process as there are a number of obstacles that can interfere with our ability to solve a problem quickly and efficiently. These obstacles include:

- Assumptions: When dealing with a problem, people can make assumptions about the constraints and obstacles that prevent certain solutions. Thus, they may not even try some potential options.

- Functional fixedness : This term refers to the tendency to view problems only in their customary manner. Functional fixedness prevents people from fully seeing all of the different options that might be available to find a solution.

- Irrelevant or misleading information: When trying to solve a problem, it's important to distinguish between information that is relevant to the issue and irrelevant data that can lead to faulty solutions. The more complex the problem, the easier it is to focus on misleading or irrelevant information.

- Mental set: A mental set is a tendency to only use solutions that have worked in the past rather than looking for alternative ideas. A mental set can work as a heuristic, making it a useful problem-solving tool. However, mental sets can also lead to inflexibility, making it more difficult to find effective solutions.

How to Improve Your Problem-Solving Skills

In the end, if your goal is to become a better problem-solver, it's helpful to remember that this is a process. Thus, if you want to improve your problem-solving skills, following these steps can help lead you to your solution:

- Recognize that a problem exists . If you are facing a problem, there are generally signs. For instance, if you have a mental illness , you may experience excessive fear or sadness, mood changes, and changes in sleeping or eating habits. Recognizing these signs can help you realize that an issue exists.

- Decide to solve the problem . Make a conscious decision to solve the issue at hand. Commit to yourself that you will go through the steps necessary to find a solution.

- Seek to fully understand the issue . Analyze the problem you face, looking at it from all sides. If your problem is relationship-related, for instance, ask yourself how the other person may be interpreting the issue. You might also consider how your actions might be contributing to the situation.

- Research potential options . Using the problem-solving strategies mentioned, research potential solutions. Make a list of options, then consider each one individually. What are some pros and cons of taking the available routes? What would you need to do to make them happen?

- Take action . Select the best solution possible and take action. Action is one of the steps required for change . So, go through the motions needed to resolve the issue.

- Try another option, if needed . If the solution you chose didn't work, don't give up. Either go through the problem-solving process again or simply try another option.

You can find a way to solve your problems as long as you keep working toward this goal—even if the best solution is simply to let go because no other good solution exists.

Sarathy V. Real world problem-solving . Front Hum Neurosci . 2018;12:261. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2018.00261

Dunbar K. Problem solving . A Companion to Cognitive Science . 2017. doi:10.1002/9781405164535.ch20

Stewart SL, Celebre A, Hirdes JP, Poss JW. Risk of suicide and self-harm in kids: The development of an algorithm to identify high-risk individuals within the children's mental health system . Child Psychiat Human Develop . 2020;51:913-924. doi:10.1007/s10578-020-00968-9

Rosenbusch H, Soldner F, Evans AM, Zeelenberg M. Supervised machine learning methods in psychology: A practical introduction with annotated R code . Soc Personal Psychol Compass . 2021;15(2):e12579. doi:10.1111/spc3.12579

Mishra S. Decision-making under risk: Integrating perspectives from biology, economics, and psychology . Personal Soc Psychol Rev . 2014;18(3):280-307. doi:10.1177/1088868314530517

Csikszentmihalyi M, Sawyer K. Creative insight: The social dimension of a solitary moment . In: The Systems Model of Creativity . 2015:73-98. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9085-7_7

Chrysikou EG, Motyka K, Nigro C, Yang SI, Thompson-Schill SL. Functional fixedness in creative thinking tasks depends on stimulus modality . Psychol Aesthet Creat Arts . 2016;10(4):425‐435. doi:10.1037/aca0000050

Huang F, Tang S, Hu Z. Unconditional perseveration of the short-term mental set in chunk decomposition . Front Psychol . 2018;9:2568. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02568

National Alliance on Mental Illness. Warning signs and symptoms .

Mayer RE. Thinking, problem solving, cognition, 2nd ed .

Schooler JW, Ohlsson S, Brooks K. Thoughts beyond words: When language overshadows insight. J Experiment Psychol: General . 1993;122:166-183. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.2.166

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10.5 Identifying and Overcoming Problem-Solving Barriers

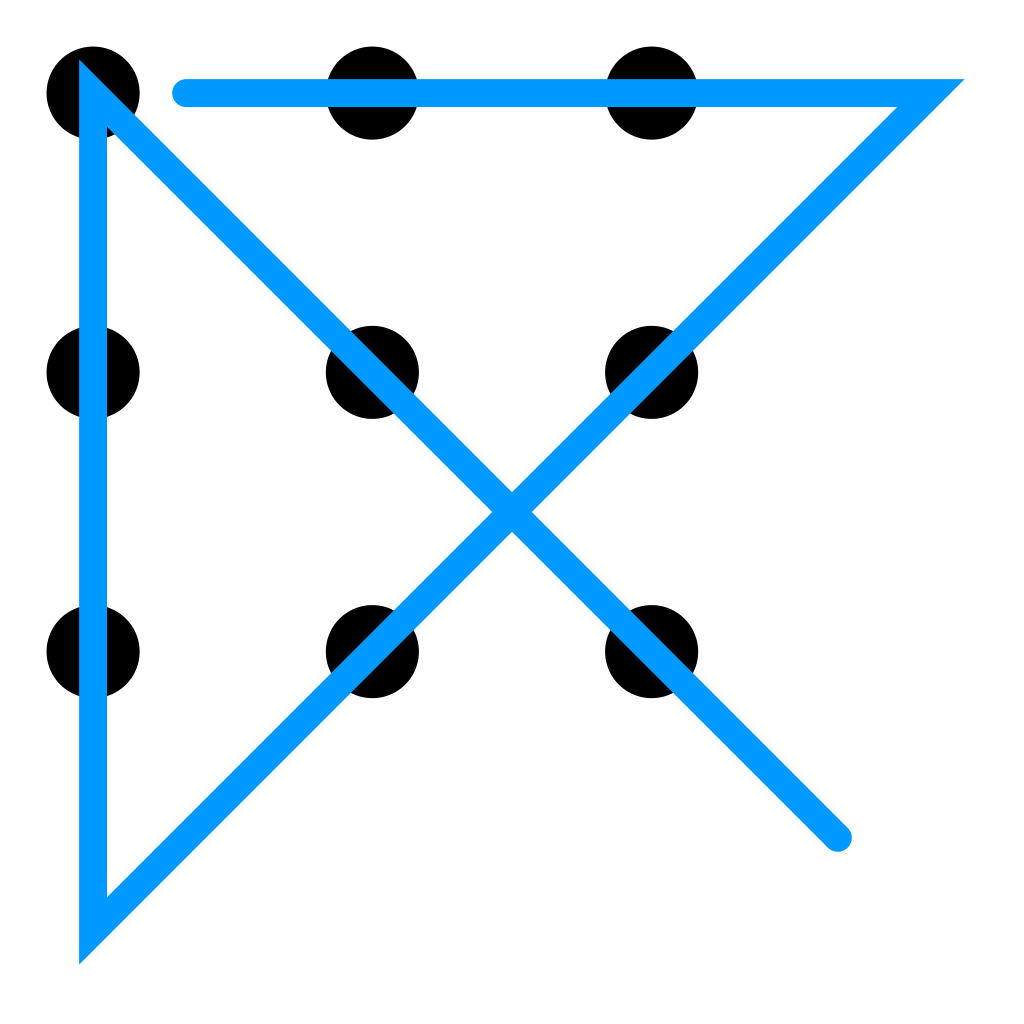

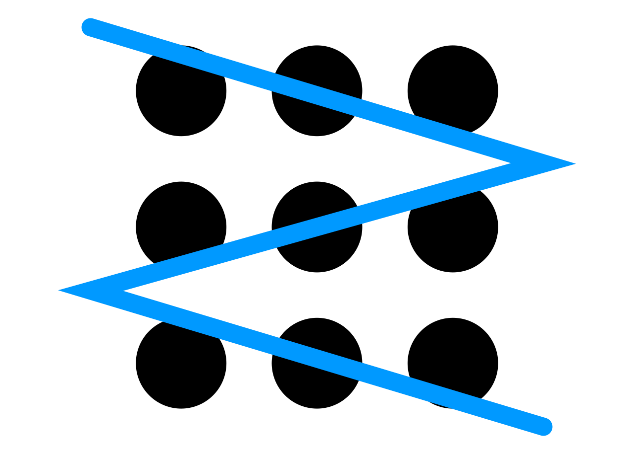

The 9 dot problem.

Here is another popular type of puzzle that challenges your spatial reasoning skills. Connect all nine dots with four connecting straight lines without lifting your pencil from the paper (Mayer, 1992).

Did you figure it out?

Solve the puzzle with 4 contiguous segments:

Now, solve the puzzle with just 3 contiguous segments!

Remember, the way that a person understands and organizes information provided in a problem or represents a problem often facilitates or hinders problem solving. If information is misunderstood, thought about, or used inappropriately, then mistakes are likely – if indeed the problem can be solved at all.

So we not only metaphorically, but sometimes literally, want to “think outside the box” to facilitate creative problem solving. Until we had this insight with the problem, we were having “ representation failure . ”

Put differently, there were obstacles in problem representation, the way that a person understands and organizes information provided in a problem. Initially, we were understanding and organizing information the information in a manner that hindered successful problem solving.

Likely related to our initial representation failure, we likely made the unwarranted assumption or unwarranted expectation that we needed to stay inside some imaginary box. Note that in some contexts, we do want to stay inside some imaginary box. Further, we often have a history of parents and teachers encouraging us to stay inside the lines, leading to a negative transfer of learning in which past learning or training negatively impacts performance on new tasks.

If information is misunderstood or used inappropriately and/or unwarranted assumptions are made, then mistakes are likely – if indeed the problem can be solved at all. With the nine-dot matrix problem, for example, construing the instruction to draw four lines as meaning “draw four lines entirely within the imaginary box matrix” means that the problem simply could not be solved.

A mental set is where you persist in approaching a problem in a way that has worked in the past but is clearly not working now .

In the example of the Nine-Dot Problem described above, students often tried one solution after another, but each solution was constrained by being stuck or set in their way of thinking about and response not to extend any line beyond the matrix of an imaginary box.

Imagine a person in a room that has four doorways. One doorway that has always been open in the past is now locked . The person, accustomed to exiting the room by that particular doorway , keeps trying to get out through the same doorway even though the other three doorways are open. The person is stuck , but she just needs to go to another doorway instead of trying to get out through the locked door.

Functional Fixedness

Fu nctional fixedness is a type of mental set where you do not consider using something for a purpose other than what it was designed for or is typically used for.

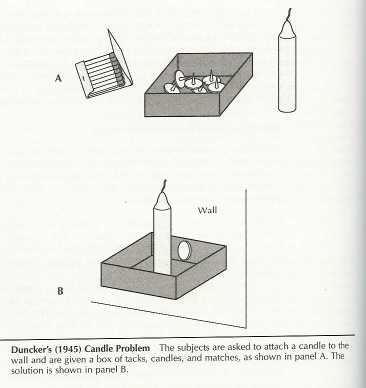

Functional fixedness concerns the solution of object-use problems. The basic idea is that when the usual way of using an object is emphasized , it will be far more difficult for a person to use that object in a novel manner . An example of this effect of being fixed on the typical use of objects is Duncker’s (194 5 ) candle problem .

Imagine you are given a box of matches, some candles and tacks. On the wall of the room there is a corkboard. Your task is to fix the candle to the corkboard in such a way that no wax will drop on the floor when the candle is lit. – Got an idea?

Explanation: The clue is just the following. When people are confronted with a problem and given certain objects to solve it, it is difficult for them to figure out that they could use them in a different (not so familiar or obvious) way s .

In this example the box needs to be recognized as a support for the candle rather than as a container. People tend to be stuck or fixed on the box as a container, and not think of or notice other uses or functions (like to support a candle).

Until we had this insight with the Candle Problem, we were having “ representation failure ”, or we were understanding and organizing information the information in a manner that hindered successful problem solving.

Likely related to our initial representation failure, we likely made the unwarranted assumption or unwarranted expectation that we needed to think about and use the box as a container (only).

Finally, check this link as an interesting way to review some of these concepts and relate them to your life. https://prezi.com/3o1o7yqdsabl/functional-fixedness/

A process in which previous learning obstructs or interferes with present learning. For instance, tennis players who learn racquetball must often unlearn their tendency to take huge, muscular swings with the shoulder and upper arm.

A temporary readiness to perform certain psychological functions that influences the response to a situation or stimulus, such as the tendency to apply a previously successful technique in solving a new problem.

The tendency to perceive an object only in terms of its most common (or intended) use.

Cognitive Psychology Copyright © by Robert Graham and Scott Griffin. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

Barriers to Effective Problem Solving

Learning how to effectively solve problems is difficult and takes time and continual adaptation. There are several common barriers to successful CPS, including:

- Confirmation Bias: The tendency to only search for or interpret information that confirms a person’s existing ideas. People misinterpret or disregard data that doesn’t align with their beliefs.

- Mental Set: People’s inclination to solve problems using the same tactics they have used to solve problems in the past. While this can sometimes be a useful strategy (see Analogical Thinking in a later section), it often limits inventiveness and creativity.

- Functional Fixedness: This is another form of narrow thinking, where people become “stuck” thinking in a certain way and are unable to be flexible or change perspective.

- Unnecessary Constraints: When people are overwhelmed with a problem, they can invent and impose additional limits on solution avenues. To avoid doing this, maintain a structured, level-headed approach to evaluating causes, effects, and potential solutions.

- Groupthink: Be wary of the tendency for group members to agree with each other — this might be out of conflict avoidance, path of least resistance, or fear of speaking up. While this agreeableness might make meetings run smoothly, it can actually stunt creativity and idea generation, therefore limiting the success of your chosen solution.

- Irrelevant Information: The tendency to pile on multiple problems and factors that may not even be related to the challenge at hand. This can cloud the team’s ability to find direct, targeted solutions.

- Paradigm Blindness : This is found in people who are unwilling to adapt or change their worldview, outlook on a particular problem, or typical way of processing information. This can erode the effectiveness of problem solving techniques because they are not aware of the narrowness of their thinking, and therefore cannot think or act outside of their comfort zone.

According to Jaffa, the primary barrier of effective problem solving is rigidity. “The most common things people say are, ‘We’ve never done it before,’ or ‘We’ve always done it this way.’” While these feelings are natural, Jaffa explains that this rigid thinking actually precludes teams from identifying creative, inventive solutions that result in the greatest benefit. “The biggest barrier to creative problem solving is a lack of awareness – and commitment to – training employees in state-of-the-art creative problem-solving techniques,” Mattimore explains. “We teach our clients how to use ideation techniques (as many as two-dozen different creative thinking techniques) to help them generate more and better ideas. Ideation techniques use specific and customized stimuli, or ‘thought triggers’ to inspire new thinking and new ideas.” MacLeod adds that ineffective or rushed leadership is another common culprit. “We're always in a rush to fix quickly,” she says. “Sometimes leaders just solve problems themselves, making unilateral decisions to save time. But the investment is well worth it — leaders will have less on their plates if they can teach and eventually trust the team to resolve. Teams feel empowered and engagement and investment increases.”

Image Courtesy of Pexels.

IMAGES

VIDEO