Essay vs. Short Story

What's the difference.

Essays and short stories are both forms of written expression, but they differ in their purpose and structure. Essays are typically non-fiction pieces that aim to inform or persuade the reader about a specific topic. They often follow a formal structure with an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. On the other hand, short stories are fictional narratives that focus on character development and plot. They can be written in various genres and styles, allowing for more creativity and imagination. While essays prioritize facts and logical arguments, short stories prioritize storytelling and evoking emotions in the reader.

| Attribute | Essay | Short Story |

|---|---|---|

| Length | Varies, can be short or long | Short, typically under 20,000 words |

| Structure | Introduction, body paragraphs, conclusion | Usually has a clear beginning, middle, and end |

| Plot | May or may not have a plot | Has a defined plot with conflict and resolution |

| Character Development | May or may not have in-depth character development | Characters are often developed within a limited scope |

| Theme | Explores a specific topic or idea | Focuses on a central theme or message |

| Tone | Varies depending on the purpose and subject matter | Can range from serious to humorous, depending on the story |

| Point of View | Can be written from various perspectives | Usually written from a single point of view |

| Language | Can be formal or informal, depending on the context | Varies, but often uses descriptive and concise language |

Further Detail

Introduction.

When it comes to literary forms, essays and short stories are two popular choices that captivate readers with their unique attributes. While both share the goal of conveying a message or exploring a theme, they differ in various aspects, including structure, length, and narrative techniques. In this article, we will delve into the characteristics of essays and short stories, highlighting their similarities and differences.

One of the primary distinctions between essays and short stories lies in their structure. Essays typically follow a more formal and structured format, often consisting of an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. The introduction sets the stage by presenting the topic and thesis statement, while the body paragraphs provide supporting evidence and analysis. Finally, the conclusion summarizes the main points and offers a closing thought.

On the other hand, short stories have a more flexible structure. They often begin with an exposition, introducing the characters, setting, and conflict. The plot then unfolds through rising action, climax, and resolution. Unlike essays, short stories allow for more creative freedom in terms of narrative structure, with authors employing various techniques such as flashbacks, foreshadowing, or nonlinear storytelling to engage readers.

Another significant difference between essays and short stories is their length. Essays are typically shorter in length, ranging from a few hundred to a few thousand words. The brevity of essays allows writers to present their ideas concisely and directly, making them suitable for conveying arguments or exploring specific topics in a focused manner.

On the contrary, short stories are longer and more expansive in nature. They can range from a few pages to several dozen pages, providing authors with ample space to develop characters, build suspense, and create intricate plotlines. The extended length of short stories allows for a deeper exploration of themes and emotions, often leaving readers with a more immersive and satisfying reading experience.

Narrative Techniques

While both essays and short stories employ narrative techniques to engage readers, they differ in their approach. Essays primarily rely on logical reasoning, evidence, and analysis to convey their message. Writers use persuasive techniques, such as ethos, pathos, and logos, to appeal to the reader's intellect and emotions. The narrative in essays is often more straightforward and focused on presenting a coherent argument or viewpoint.

In contrast, short stories utilize a wide range of narrative techniques to create a captivating and immersive experience. Authors employ descriptive language, dialogue, and vivid imagery to bring characters and settings to life. They can experiment with different points of view, shifting perspectives, and unreliable narrators to add depth and complexity to the story. The narrative in short stories is often more imaginative and allows for a greater exploration of the human experience.

Themes and Messages

Both essays and short stories aim to convey themes and messages to their readers, but they do so in distinct ways. Essays often focus on presenting an argument or discussing a specific topic, aiming to inform, persuade, or provoke thought. The themes in essays are typically more explicit and directly related to the subject matter being discussed.

On the other hand, short stories explore themes and messages through storytelling and the experiences of characters. They often delve into complex human emotions, moral dilemmas, or societal issues, allowing readers to reflect on the deeper meaning behind the narrative. The themes in short stories are often more implicit, requiring readers to analyze the story's events and characters to uncover the underlying messages.

In conclusion, while essays and short stories share the common goal of conveying a message or exploring a theme, they differ significantly in terms of structure, length, narrative techniques, and the way they approach themes. Essays offer a more formal and structured approach, focusing on presenting arguments and analysis concisely. On the other hand, short stories provide a more immersive and imaginative experience, allowing for the exploration of complex characters, plotlines, and themes. Both forms of writing have their unique merits and appeal, catering to different reading preferences and purposes.

Comparisons may contain inaccurate information about people, places, or facts. Please report any issues.

The short story is a fiction writer’s laboratory: here is where you can experiment with characters, plots, and ideas without the heavy lifting of writing a novel. Learning how to write a short story is essential to mastering the art of storytelling . With far fewer words to worry about, storytellers can make many more mistakes—and strokes of genius!—through experimentation and the fun of fiction writing.

Nonetheless, the art of writing short stories is not easy to master. How do you tell a complete story in so few words? What does a story need to have in order to be successful? Whether you’re struggling with how to write a short story outline, or how to fully develop a character in so few words, this guide is your starting point.

Famous authors like Virginia Woolf, Haruki Murakami, and Agatha Christie have used the short story form to play with ideas before turning those stories into novels. Whether you want to master the elements of fiction, experiment with novel ideas, or simply have fun with storytelling, here’s everything you need on how to write a short story step by step.

How to Write a Short Story: Contents

The Core Elements of a Short Story

How to write a short story outline, how to write a short story step by step, how to write a short story: length and setting, how to write a short story: point of view, how to write a short story: protagonist, antagonist, motivation, how to write a short story: characters, how to write a short story: prose, how to write a short story: story structure, how to write a short story: capturing reader interest, where to read and submit short stories.

There’s no secret formula to writing a short story. However, a good short story will have most or all of the following elements:

- A protagonist with a certain desire or need. It is essential for the protagonist to want something they don’t have, otherwise they will not drive the story forward.

- A clear dilemma. We don’t need much backstory to see how the dilemma started; we’re primarily concerned with how the protagonist resolves it.

- A decision. What does the protagonist do to resolve their dilemma?

- A climax. In Freytag’s Pyramid , the climax of a story is when the tension reaches its peak, and the reader discovers the outcome of the protagonist’s decision(s).

- An outcome. How does the climax change the protagonist? Are they a different person? Do they have a different philosophy or outlook on life?

Of course, short stories also utilize the elements of fiction , such as a setting , plot , and point of view . It helps to study these elements and to understand their intricacies. But, when it comes to laying down the skeleton of a short story, the above elements are what you need to get started.

Note: a short story rarely, if ever, has subplots. The focus should be entirely on a single, central storyline. Subplots will either pull focus away from the main story, or else push the story into the territory of novellas and novels.

The shorter the story is, the fewer of these elements are essentials. If you’re interested in writing short-short stories, check out our guide on how to write flash fiction .

Some writers are “pantsers”—they “write by the seat of their pants,” making things up on the go with little more than an idea for a story. Other writers are “plotters,” meaning they decide the story’s structure in advance of writing it.

You don’t need a short story outline to write a good short story. But, if you’d like to give yourself some scaffolding before putting words on the page, this article answers the question of how to write a short story outline:

https://writers.com/how-to-write-a-story-outline

There are many ways to approach the short story craft, but this method is tried-and-tested for writers of all levels. Here’s how to write a short story step-by-step.

1. Start With an Idea

Often, generating an idea is the hardest part. You want to write, but what will you write about?

What’s more, it’s easy to start coming up with ideas and then dismissing them. You want to tell an authentic, original story, but everything you come up with has already been written, it seems.

Here are a few tips:

- Originality presents itself in your storytelling, not in your ideas. For example, the premise of both Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Ostrovsky’s The Snow Maiden are very similar: two men and two women, in intertwining love triangles, sort out their feelings for each other amidst mischievous forest spirits, love potions, and friendship drama. The way each story is written makes them very distinct from one another, to the point where, unless it’s pointed out to you, you might not even notice the similarities.

- An idea is not a final draft. You will find that exploring the possibilities of your story will generate something far different than the idea you started out with. This is a good thing—it means you made the story your own!

- Experiment with genres and tropes. Even if you want to write literary fiction , pay attention to the narrative structures that drive genre stories, and practice your storytelling using those structures. Again, you will naturally make the story your own simply by playing with ideas.

If you’re struggling simply to find ideas, try out this prompt generator , or pull prompts from this Twitter .

2. Outline, OR Conceive Your Characters

If you plan to outline, do so once you’ve generated an idea. You can learn about how to write a short story outline earlier in this article.

If you don’t plan to outline, you should at least start with a character or characters. Certainly, you need a protagonist, but you should also think about any characters that aid or inhibit your protagonist’s journey.

When thinking about character development, ask the following questions:

- What is my character’s background? Where do they come from, how did they get here, where do they want to be?

- What does your character desire the most? This can be both material or conceptual, like “fitting in” or “being loved.”

- What is your character’s fatal flaw? In other words, what limitation prevents the protagonist from achieving their desire? Often, this flaw is a blind spot that directly counters their desire. For example, self hatred stands in the way of a protagonist searching for love.

- How does your character think and speak? Think of examples, both fictional and in the real world, who might resemble your character.

In short stories, there are rarely more characters than a protagonist, an antagonist (if relevant), and a small group of supporting characters. The more characters you include, the longer your story will be. Focus on making only one or two characters complex: it is absolutely okay to have the rest of the cast be flat characters that move the story along.

Learn more about character development here:

https://writers.com/character-development-definition

3. Write Scenes Around Conflict

Once you have an outline or some characters, start building scenes around conflict. Every part of your story, including the opening sentence, should in some way relate to the protagonist’s conflict.

Conflict is the lifeblood of storytelling: without it, the reader doesn’t have a clear reason to keep reading. Loveable characters are not enough, as the story has to give the reader something to root for.

Take, for example, Edgar Allan Poe’s classic short story The Cask of Amontillado . We start at the conflict: the narrator has been slighted by Fortunato, and plans to exact revenge. Every scene in the story builds tension and follows the protagonist as he exacts this revenge.

In your story, start writing scenes around conflict, and make sure each paragraph and piece of dialogue relates, in some way, to your protagonist’s unmet desires.

Read more about writing effective conflict here:

What is Conflict in a Story? Definition and Examples

4. Write Your First Draft

The scenes you build around conflict will eventually be stitched into a complete story. Make sure as the story progresses that each scene heightens the story’s tension, and that this tension remains unbroken until the climax resolves whether or not your protagonist meets their desires.

Don’t stress too hard on writing a perfect story. Rather, take Anne Lamott’s advice, and “write a shitty first draft.” The goal is not to pen a complete story at first draft; rather, it’s to set ideas down on paper. You are simply, as Shannon Hale suggests, “shoveling sand into a box so that later [you] can build castles.”

5. Step Away, Breathe, Revise

Whenever Stephen King finishes a novel, he puts it in a drawer and doesn’t think about it for 6 weeks. With short stories, you probably don’t need to take as long of a break. But, the idea itself is true: when you’ve finished your first draft, set it aside for a while. Let yourself come back to the story with fresh eyes, so that you can confidently revise, revise, revise .

In revision, you want to make sure each word has an essential place in the story, that each scene ramps up tension, and that each character is clearly defined. The culmination of these elements allows a story to explore complex themes and ideas, giving the reader something to think about after the story has ended.

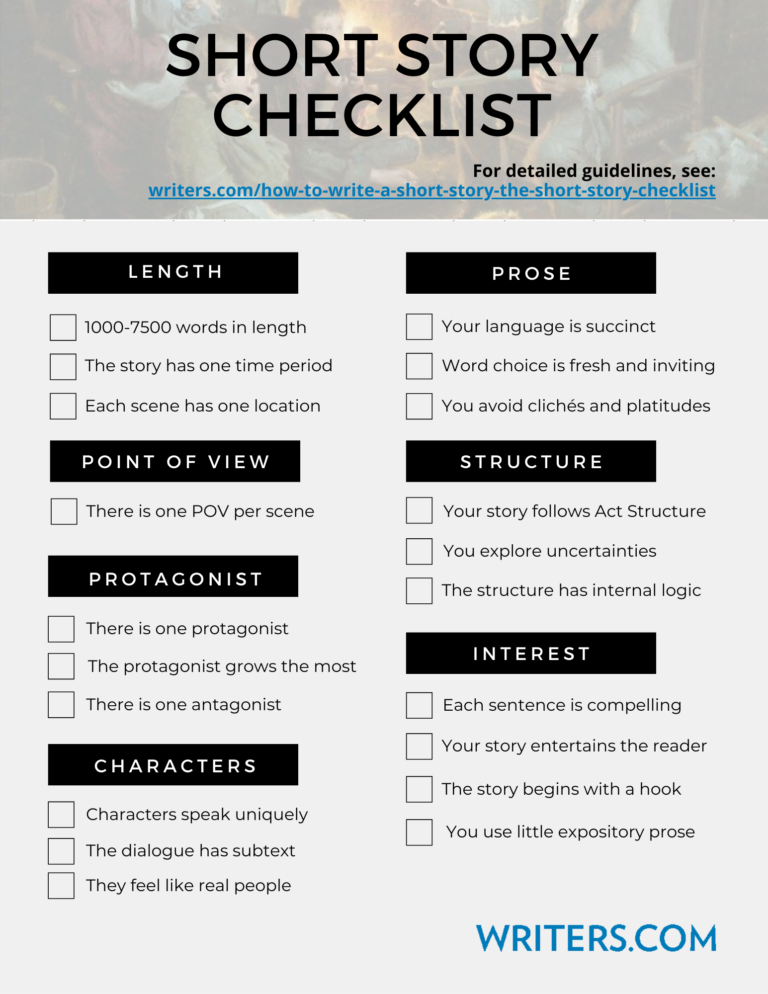

6. Compare Against Our Short Story Checklist

Does your story have everything it needs to succeed? Compare it against this short story checklist, as written by our instructor Rosemary Tantra Bensko.

Below is a collection of practical short story writing tips by Writers.com instructor Rosemary Tantra Bensko . Each paragraph is its own checklist item: a core element of short story writing advice to follow unless you have clear reasons to the contrary. We hope it’s a helpful resource in your own writing.

Update 9/1/2020: We’ve now made a summary of Rosemary’s short story checklist available as a PDF download . Enjoy!

Click to download

Your short story is 1000 to 7500 words in length.

The story takes place in one time period, not spread out or with gaps other than to drive someplace, sleep, etc. If there are those gaps, there is a space between the paragraphs, the new paragraph beginning flush left, to indicate a new scene.

Each scene takes place in one location, or in continual transit, such as driving a truck or flying in a plane.

Unless it’s a very lengthy Romance story, in which there may be two Point of View (POV) characters, there is one POV character. If we are told what any character secretly thinks, it will only be the POV character. The degree to which we are privy to the unexpressed thoughts, memories and hopes of the POV character remains consistent throughout the story.

You avoid head-hopping by only having one POV character per scene, even in a Romance. You avoid straying into even brief moments of telling us what other characters think other than the POV character. You use words like “apparently,” “obviously,” or “supposedly” to suggest how non-POV-characters think rather than stating it.

Your short story has one clear protagonist who is usually the character changing most.

Your story has a clear antagonist, who generally makes the protagonist change by thwarting his goals.

(Possible exception to the two short story writing tips above: In some types of Mystery and Action stories, particularly in a series, etc., the protagonist doesn’t necessarily grow personally, but instead his change relates to understanding the antagonist enough to arrest or kill him.)

The protagonist changes with an Arc arising out of how he is stuck in his Flaw at the beginning of the story, which makes the reader bond with him as a human, and feel the pain of his problems he causes himself. (Or if it’s the non-personal growth type plot: he’s presented at the beginning of the story with a high-stakes problem that requires him to prevent or punish a crime.)

The protagonist usually is shown to Want something, because that’s what people normally do, defining their personalities and behavior patterns, pushing them onward from day to day. This may be obvious from the beginning of the story, though it may not become heightened until the Inciting Incident , which happens near the beginning of Act 1. The Want is usually something the reader sort of wants the character to succeed in, while at the same time, knows the Want is not in his authentic best interests. This mixed feeling in the reader creates tension.

The protagonist is usually shown to Need something valid and beneficial, but at first, he doesn’t recognize it, admit it, honor it, integrate it with his Want, or let the Want go so he can achieve the Need instead. Ideally, the Want and Need can be combined in a satisfying way toward the end for the sake of continuity of forward momentum of victoriously achieving the goals set out from the beginning. It’s the encounters with the antagonist that forcibly teach the protagonist to prioritize his Needs correctly and overcome his Flaw so he can defeat the obstacles put in his path.

The protagonist in a personal growth plot needs to change his Flaw/Want but like most people, doesn’t automatically do that when faced with the problem. He tries the easy way, which doesn’t work. Only when the Crisis takes him to a low point does he boldly change enough to become victorious over himself and the external situation. What he learns becomes the Theme.

Each scene shows its main character’s goal at its beginning, which aligns in a significant way with the protagonist’s overall goal for the story. The scene has a “charge,” showing either progress toward the goal or regression away from the goal by the ending. Most scenes end with a negative charge, because a story is about not obtaining one’s goals easily, until the end, in which the scene/s end with a positive charge.

The protagonist’s goal of the story becomes triggered until the Inciting Incident near the beginning, when something happens to shake up his life. This is the only major thing in the story that is allowed to be a random event that occurs to him.

Your characters speak differently from one another, and their dialogue suggests subtext, what they are really thinking but not saying: subtle passive-aggressive jibes, their underlying emotions, etc.

Your characters are not illustrative of ideas and beliefs you are pushing for, but come across as real people.

Your language is succinct, fresh and exciting, specific, colorful, avoiding clichés and platitudes. Sentence structures vary. In Genre stories, the language is simple, the symbolism is direct, and words are well-known, and sentences are relatively short. In Literary stories , you are freer to use more sophisticated ideas, words, sentence structures, styles , and underlying metaphors and implied motifs.

Your plot elements occur in the proper places according to classical Three Act Structure (or Freytag’s Pyramid ) so the reader feels he has vicariously gone through a harrowing trial with the protagonist and won, raising his sense of hope and possibility. Literary short stories may be more subtle, with lower stakes, experimenting beyond classical structures like the Hero’s Journey. They can be more like vignettes sometimes, or even slice-of-life, though these types are hard to place in publications.

In Genre stories, all the questions are answered, threads are tied up, problems are solved, though the results of carnage may be spread over the landscape. In Literary short stories, you are free to explore uncertainty, ambiguity, and inchoate, realistic endings that suggest multiple interpretations, and unresolved issues.

Some Literary stories may be nonrealistic, such as with Surrealism, Absurdism, New Wave Fabulism, Weird and Magical Realism . If this is what you write, they still need their own internal logic and they should not be bewildering as to the what the reader is meant to experience, whether it’s a nuanced, unnameable mood or a trip into the subconscious.

Literary stories may also go beyond any label other than Experimental. For example, a story could be a list of To Do items on a paper held by a magnet to a refrigerator for the housemate to read. The person writing the list may grow more passive-aggressive and manipulative as the list grows, and we learn about the relationship between the housemates through the implied threats and cajoling.

Your short story is suspenseful, meaning readers hope the protagonist will achieve his best goal, his Need, by the Climax battle against the antagonist.

Your story entertains. This is especially necessary for Genre short stories.

The story captivates readers at the very beginning with a Hook, which can be a puzzling mystery to solve, an amazing character’s or narrator’s Voice, an astounding location, humor, a startling image, or a world the reader wants to become immersed in.

Expository prose (telling, like an essay) takes up very, very little space in your short story, and it does not appear near the beginning. The story is in Narrative format instead, in which one action follows the next. You’ve removed every unnecessary instance of Expository prose and replaced it with showing Narrative. Distancing words like “used to,” “he would often,” “over the years, he,” “each morning, he” indicate that you are reporting on a lengthy time period, summing it up, rather than sticking to Narrative format, in which immediacy makes the story engaging.

You’ve earned the right to include Expository Backstory by making the reader yearn for knowing what happened in the past to solve a mystery. This can’t possibly happen at the beginning, obviously. Expository Backstory does not take place in the first pages of your story.

Your reader cares what happens and there are high stakes (especially important in Genre stories). Your reader worries until the end, when the protagonist survives, succeeds in his quest to help the community, gets the girl, solves or prevents the crime, achieves new scientific developments, takes over rule of his realm, etc.

Every sentence is compelling enough to urge the reader to read the next one—because he really, really wants to—instead of doing something else he could be doing. Your story is not going to be assigned to people to analyze in school like the ones you studied, so you have found a way from the beginning to intrigue strangers to want to spend their time with your words.

Whether you’re looking for inspiration or want to publish your own stories, you’ll find great literary journals for writers of all backgrounds at this article:

https://writers.com/short-story-submissions

Learn How to Write a Short Story at Writers.com

The short story takes an hour to learn and a lifetime to master. Learn how to write a short story with Writers.com. Our upcoming fiction courses will give you the ropes to tell authentic, original short stories that captivate and entrance your readers.

Rosemary – Is there any chance you could add a little something to your checklist? I’d love to know the best places to submit our short stories for publication. Thanks so much.

Hi, Kim Hanson,

Some good places to find publications specific to your story are NewPages, Poets and Writers, Duotrope, and The Submission Grinder.

“ In Genre stories, all the questions are answered, threads are tied up, problems are solved, though the results of carnage may be spread over the landscape.”

Not just no but NO.

See for example the work of MacArthur Fellow Kelly Link.

[…] How to Write a Short Story: The Short Story Checklist […]

Thank you for these directions and tips. It’s very encouraging to someone like me, just NOW taking up writing.

[…] Writers.com. A great intro to writing. https://writers.com/how-to-write-a-short-story […]

Hello: I started to write seriously in the late 70’s. I loved to write in High School in the early 60’s but life got in the way. Around the 00’s many of the obstacles disappeared. Since then I have been writing more, and some of my work was vanilla transgender stories. Here in 2024 transgender stories have become tiresome because I really don’t have much in common with that mind set.

The glare of an editor that could potentially pay me is quite daunting, so I would like to start out unpaid to see where that goes. I am not sure if a writer’s agent would be a good fit for me. My work life was in the Trades, not as some sort of Academic. That alone causes timidity, but I did read about a fiction writer who had been a house painter.

This is my first effort to publish since the late 70’s. My pseudonym would perhaps include Ahabidah.

Gwen Boucher.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Short Story Analysis Essay

Short story analysis essay generator.

Almost everyone has read a couple of short stories from the time they were kids up until today. Although, depending on how old you are, you analyze the stories you read differently. As a kid, you often point out who is the good guy and the bad guy. You even express your complaints if you do not like the ending. Now, in high school or maybe in college, you pretty much do the same, but you need to incorporate your critical thinking skills and follow appropriate formatting. That said, to present the results of your literature review, compose a short story analysis essay.

3+ Short Story Analysis Essay Examples

1. short story analysis essay template.

Size: 310 KB

2. Sample Short Story Analysis Essay

Size: 75 KB

3. Short Story Analysis Essay Example

Size: 298 KB

4. Printable Short Story Analysis Essay

Size: 121 KB

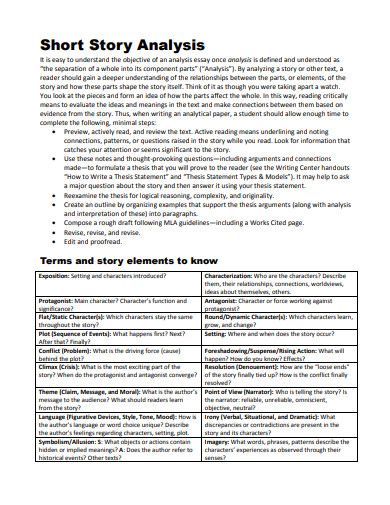

What Is a Short Story Analysis Essay?

A short story analysis essay is a composition that aims to examine the plot and the aspects of the story. In writing this document, the writer needs to take the necessary elements of a short story into account. In addition, one purpose of writing this type of analysis essay is to identify the theme of the story. As well as try to make connections between the different aspects.

How to Compose a Critical Short Story Analysis Essay

Having the assignment to write a short story analysis can be overwhelming. Reading the short story is easy enough. Evaluating and writing down your essay is the challenging part. A short story analysis essay follows a different format from other literature essays . That said, to help with that, here are instructive steps and helpful tips.

1. Take Down Notes

Considering that you have read the short story a couple of times, the first step you should take before writing your essay is to summarize and write down your notes. To help you with this, you can utilize flow charts to determine the arcs the twists of the short story. Include the parts and segments that affected you the most, as well as the ones that hold significance for the whole story.

2. Compose Your Thesis Statement

Before composing your thesis statement for the introductory paragraph of your essay, first, you need to identify the thematic statement of the story. This sentence should present the underlying message of the entire literature. It is where the story revolves around. After that, you can use it as a basis and proceed with composing your thesis statement. It should provide the readers an overview of the content of your analysis paper.

3. Analyze the Concepts

One of the essential segments of your paper is, of course, the analysis part. In the body of your essay, you should present arguments that discuss the concepts that you were able to identify. To support your point, you should provide evidence and quote sentences from the story. If you present strong supporting sentences, it will make your composition more effective. To help with the organization and the structure, you can utilize an analysis paper outline .

4. Craft Your Conclusion

The last part of the process is to craft a conclusion for your essay . Aside from restating the crucial points and the thesis statement, there is another factor that you should consider for the ending paragraph. That said, you should also present your understanding regarding why the author wrote the story that way. In addition, you can also wrap it up by expressing how the story made you feel.

How to run an in-depth analysis of a short story?

In analyzing a short story, you should individually examine the elements of a short story. That said, you need to study the characters, setting, tone, and plot. In addition, you should also consider evaluating the author’s point of view, writing style, and story-telling method. Also, it involves studying how the story affects you personally.

Why is it necessary to compose analysis essays?

Composing analysis essays tests how well a person understands a reading material. It is a good alternative for reading comprehension worksheets . Another advantage of devising this paper is it encourages people to look at a story from different angles and perspectives. In addition to this, it lets the students enhance their article writing potential.

What is critical writing?

Conducting a critical analysis requires an individual to examine the details and facts in the literature closely. It involves breaking down ideas as well as linking them to develop a point or argument. Despite that, the prime purpose of a critical essay is to give a literary criticism of the things the author did well and the things they did poorly.

People enjoy reading short stories. It is for the reason that aside from being brief, they also present meaningful messages and themes. In addition to that, it also brings you to a memorable ride with its entertaining conflicts and plot twists. That said, as a sign of respect to the well-crafted literature, you should present your thoughts about it by generating a well-founded short story analysis essay.

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

Short Story Analysis Essay on the theme of courage in

Short Story Analysis Essay on symbolism in

Home » Writing » What is a short story?

What is the history of the short story?

Short-form storytelling can be traced back to ancient legends, mythology, folklore, and fables found in communities all over the world. Some of these stories existed in written form, but many were passed down through oral traditions. By the 14 th century, the most well-known stories included One Thousand and One Nights (Middle Eastern folk tales by multiple authors, later known as Arabian Nights ) and Canterbury Tales (by Geoffrey Chaucer).

It wasn’t until the early 19th century that short story collections by individual authors appeared more regularly in print. First, it was the publication of the Brothers Grimm fairy tales, then Edgar Allen Poe’s Gothic fiction, and eventually, stories by Anton Chekhov, who is often credited as a founder of the modern short story.

The popularity of short stories grew along with the surge of print magazines and journals. Newspaper and magazine editors began publishing stories as entertainment, creating a demand for short, plot-driven narratives with mass appeal. By the early 1900s, The Atlantic Monthly , The New Yorker , and Harper’s Magazine were paying good money for short stories that showed more literary techniques. That golden era of publishing gave rise to the short story as we know it today.

What are the different types of short stories?

Short stories come in all kinds of categories: action, adventure, biography, comedy, crime, detective, drama, dystopia, fable, fantasy, history, horror, mystery, philosophy, politics, romance, satire, science fiction, supernatural, thriller, tragedy, and Western. Here are some popular types of short stories, literary styles, and authors associated with them:

- Fable: A tale that provides a moral lesson, often using animals, mythical creatures, forces of nature, or inanimate objects to come to life (Brothers Grimm, Aesop)

- Flash fiction : A story between 5 to 2,000 words that lacks traditional plot structure or character development and is often characterized by a surprise or twist of fate (Lydia Davis)

- Mini saga: A type of micro-fiction using exactly 50 words (!) to tell a story

- Vignette: A descriptive scene or defining moment that does not contain a complete plot or narrative but reveals an important detail about a character or idea (Sandra Cisneros)

- Modernism: Experimenting with narrative form, style, and chronology (inner monologues, stream of consciousness) to capture the experience of an individual (James Joyce, Virginia Woolf)

- Postmodernism: Using fragmentation, paradox, or unreliable narrators to explore the relationship between the author, reader, and text (Donald Barthelme, Jorge Luis Borges)

- Magical realism: Combining realistic narrative or setting with elements of surrealism, dreams, or fantasy (Gabriel García Márquez)

- Minimalism: Writing characterized by brevity, straightforward language, and a lack of plot resolutions (Raymond Carver, Amy Hempel)

What are some famous short stories?

- “The Tell-Tale Heart” (1843) – Edgar Allen Poe

- “The Necklace” (1884) – Guy de Maupassant

- “The Yellow Wallpaper” (1892) – Charlotte Perkins Gilman

- “The Story of an Hour” (1894) – Kate Chopin

- “Gift of the Magi” (1905) – O. Henry

- “The Dead,” “The Dubliners” (1914) – James Joyce

- “The Garden Party” (1920) – Katherine Mansfield

- “Hills Like White Elephants” (1927), “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” (1936) – Ernest Hemingway

- “The Lottery” (1948) – Shirley Jackson

- “Lamb to the Slaughter” (1953) – Roald Dahl

- “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings” (1955) – Gabriel García Márquez

- “Sonny’s Blues” (1957) – James Baldwin

- “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” (1953), “Everything That Rises Must Converge” (1961) – Flannery O’Connor

What are some popular short story collections?

- The Things They Carried – Tim O’Brien

- Labyrinths – Jorge Luis Borges

- Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman – Haruki Murakami

- Nine Stories – J.D. Salinger

- What We Talk About When We Talk About Love – Raymond Carver

- The Stories of John Cheever – John Cheever

- Welcome to the Monkey House – Kurt Vonnegut

- Complete Stories – Dorothy Parker

- Interpreter of Maladies – Jhumpa Lahiri

- Suddenly a Knock at the Door – Etgar Keret

Do you have a short story collection or another book project in the works? Download our free layout software , BookWright, today and start envisioning the pages of your next book!

This is a unique website which will require a more modern browser to work! Please upgrade today!

This is a modern website which will require Javascript to work.

Please turn it on!

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

Analysis of the genre

- From Egypt to India

- Proliferation of forms

- Spreading popularity

- Decline of short fiction

- The 19th century

- The “impressionist” story

- Respect for the story

- French writers

- Russian writers

- The 20th century

- When did Mark Twain start writing?

- What are some of Mark Twain’s most famous works?

- What was Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s family like?

- What did Johann Wolfgang von Goethe write?

- When did Johann Wolfgang von Goethe get married?

short story

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- PressbooksOER - Introduction to Short Fiction

- Ipwa Universitiy Libraries - The Short Story: A Singular Effort

- Pressbooks at TAMU - Surface and Subtext: Literature, Research, Writing - Key Components of Short Stories

- short story - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

short story , brief fictional prose narrative that is shorter than a novel and that usually deals with only a few characters.

The short story is usually concerned with a single effect conveyed in only one or a few significant episodes or scenes. The form encourages economy of setting , concise narrative, and the omission of a complex plot ; character is disclosed in action and dramatic encounter but is seldom fully developed. Despite its relatively limited scope, though, a short story is often judged by its ability to provide a “complete” or satisfying treatment of its characters and subject.

Before the 19th century the short story was not generally regarded as a distinct literary form. But although in this sense it may seem to be a uniquely modern genre , the fact is that short prose fiction is nearly as old as language itself. Throughout history humankind has enjoyed various types of brief narratives: jests, anecdotes , studied digressions , short allegorical romances, moralizing fairy tales, short myths , and abbreviated historical legends . None of these constitutes a short story as it has been defined since the 19th century, but they do make up a large part of the milieu from which the modern short story emerged.

As a genre , the short story received relatively little critical attention through the middle of the 20th century, and the most valuable studies of the form were often limited by region or era. In his The Lonely Voice (1963), the Irish short story writer Frank O’Connor attempted to account for the genre by suggesting that stories are a means for “submerged population groups” to address a dominating community . Most other theoretical discussions, however, were predicated in one way or another on Edgar Allan Poe ’s thesis that stories must have a compact unified effect.

By far the majority of criticism on the short story focused on techniques of writing. Many, and often the best of the technical works, advise the young reader—alerting the reader to the variety of devices and tactics employed by the skilled writer. On the other hand, many of these works are no more than treatises on “how to write stories” for the young writer rather than serious critical material.

The prevalence in the 19th century of two words, “ sketch ” and “tale,” affords one way of looking at the genre. In the United States alone there were virtually hundreds of books claiming to be collections of sketches ( Washington Irving ’s The Sketch Book , William Dean Howells ’s Suburban Sketches ) or collections of tales (Poe’s Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque , Herman Melville ’s The Piazza Tales ). These two terms establish the polarities of the milieu out of which the modern short story grew.

The tale is much older than the sketch. Basically, the tale is a manifestation of a culture’s unaging desire to name and conceptualize its place in the cosmos. It provides a culture’s narrative framework for such things as its vision of itself and its homeland or for expressing its conception of its ancestors and its gods. Usually filled with cryptic and uniquely deployed motifs, personages, and symbols , tales are frequently fully understood only by members of the particular culture to which they belong. Simply, tales are intracultural. Seldom created to address an outside culture, a tale is a medium through which a culture speaks to itself and thus perpetuates its own values and stabilizes its own identity. The old speak to the young through tales.

The sketch, by contrast, is intercultural, depicting some phenomenon of one culture for the benefit or pleasure of a second culture. Factual and journalistic, in essence the sketch is generally more analytic or descriptive and less narrative or dramatic than the tale. Moreover, the sketch by nature is suggestive , incomplete; the tale is often hyperbolic , overstated.

The primary mode of the sketch is written; that of the tale, spoken . This difference alone accounts for their strikingly different effects. The sketch writer can have, or pretend to have, his eye on his subject. The tale, recounted at court or campfire—or at some place similarly removed in time from the event—is nearly always a re-creation of the past. The tale-teller is an agent of time , bringing together a culture’s past and its present. The sketch writer is more an agent of space , bringing an aspect of one culture to the attention of a second.

It is only a slight oversimplification to suggest that the tale was the only kind of short fiction until the 16th century, when a rising middle class interest in social realism on the one hand and in exotic lands on the other put a premium on sketches of subcultures and foreign regions. In the 19th century certain writers—those one might call the “fathers” of the modern story: Nikolay Gogol , Hawthorne, E.T.A. Hoffmann , Heinrich von Kleist , Prosper Mérimée , Poe—combined elements of the tale with elements of the sketch. Each writer worked in his own way, but the general effect was to mitigate some of the fantasy and stultifying conventionality of the tale and, at the same time, to liberate the sketch from its bondage to strict factuality. The modern short story, then, ranges between the highly imaginative tale and the photographic sketch and in some ways draws on both.

The short stories of Ernest Hemingway , for example, may often gain their force from an exploitation of traditional mythic symbols (water, fish, groin wounds), but they are more closely related to the sketch than to the tale. Indeed, Hemingway was able at times to submit his apparently factual stories as newspaper copy. In contrast, the stories of Hemingway’s contemporary William Faulkner more closely resemble the tale. Faulkner seldom seems to understate, and his stories carry a heavy flavour of the past. Both his language and his subject matter are rich in traditional material. A Southerner might well suspect that only a reader steeped in sympathetic knowledge of the traditional South could fully understand Faulkner. Faulkner may seem, at times, to be a Southerner speaking to and for Southerners. But, as, by virtue of their imaginative and symbolic qualities, Hemingway’s narratives are more than journalistic sketches, so, by virtue of their explorative and analytic qualities, Faulkner’s narratives are more than Southern tales.

Whether or not one sees the modern short story as a fusion of sketch and tale, it is hardly disputable that today the short story is a distinct and autonomous , though still developing, genre.

TRY OUR FREE APP

Write your book in Reedsy Studio. Try the beloved writing app for free today.

Craft your masterpiece in Reedsy Studio

Plan, write, edit, and format your book in our free app made for authors.

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Posted on May 17, 2021

What is a Short Story? Definitions and Examples

A short story is a form of fiction writing defined by its brevity . A short story usually falls between 3,000 and 7,000 words — the average short story length is around the 5,000 mark. Short stories primarily work to encapsulate a mood, typically covering minimal incidents with a limited cast of characters — in some cases, they might even forgo a plot altogether.

Many early-career novelists have dabbled in the form and had their work featured in literary magazines and anthologies. Others, like Raymond Carver and Alice Munro, have made it their bread and butter. From “starter” short story writers to short story experts, there’s an incredible range of short stories out there.

In this series of guides, we'll be looking into short stories and showing you how any writer can write a powerful piece of short fiction — and even get it published. But before we get into the weeds, let's look at a few examples to demonstrate the range and flexibility of this form.

Broadly speaking, you could answer the question of "what is a short story" in a few ways, starting with the most obvious.

A classic short narrative

Though short stories must inherently be concise pieces of writing, they often incorporate elements of the novel to retain a similar impact. A ‘classic short narrative’ is the most story-telling-by-the-numbers that a short story can get — the plot will imitate long-form fiction by having a defined exposition, escalating rising action , a climax, and a resolution.

Short stories do differ from longer prose works in some respects: they’re unlikely to contain a huge cast of characters, multiple points of view , or successive climaxes like those found in novellas and novels. But despite these cuts, if the author does their job right, a ‘classic’ short story will be just as affecting and memorable as a novel — if not more so.

Example #1: “Speaking in Tongues” by ZZ Packer

Tia, disillusioned with her strict Pentecostal upbringing in a sleepy Southern town, escapes her great-aunt’s clutches to find her mother in Atlanta. This story starts with a classic expository beat — Tia at school, flicking through a religious textbook, dreaming of another life. This is followed by a crisis: Tia travels by bus to the big city, befriends a man on the street, and goes to stay with him, only to learn that he is a drug dealer and a pimp. Eventually, Tia returns home to her great-aunt. In all, it’s a sensitive story about the vulnerability of youth and the longing for family.

As short stories go, “Speaking In Tongues” has a pretty impressive narrative. You can see how the premise and plot could work as a longer piece of fiction, but they pack even more of a punch in this shorter form.

A vignette is a short story that presents a neatly packaged moment in time, usually in quite a technically accomplished fashion. ‘Vignette’ is French word more frequently used to signify a small portrait, but in a literary sense, it means “a brief evocative description, account, or episode”. This could be of a person, event or place.

Fleetingness is at the crux of a vignette short story. For that reason, it is likely to be heavy on description, light on plot. You might find a particularly embellished description of a character or setting, often with a strong dose of symbolism that corresponds with a central theme.

Example #2: “Viewfinder” by Raymond Carver

“Viewfinder” has a simple premise: a traveling photographer takes a photo of the narrator’s house, sells it to him on his doorstep, and is invited in for coffee. The story emphasizes feelings of loneliness that come to the fore in their interaction, captured brilliantly by Carver’s unadorned writing style. Tales like this that attribute importance to the mundane are arguably best served by a concise form as Carver's fascination with banal events could have become repetitive and rudderless in a longer piece of work.

Many critics agree that no one writes the American working classes quite like Carver. His stories chronicle the everyday experiences of Midwestern men and women eking out a living then fish, play cards, and shoot the breeze as life passes them by. It won Carver immense critical acclaim in his lifetime and is a great example of short-form writing that emphasizes mood rather than plot.

An anecdote

An anecdote recounted to friends is most successful when it’s pacey, humorous, and has a quick crescendo. The same can be said of short stories that capitalize on this storytelling device.

Anecdotal stories take on a more conversational tone and are more meandering in style, in contrast to the directness of other short stories and flash fiction . It can have a conventional story structure, like the classic short narrative, or it may focus on a particular stylistic recounting of an event. Basically, an anecdote allows a writer to have fun with the way a story is told — though exactly how it unfolds remains important too.

Example #3: “We Love You Crispina” by Jenny Zhang

Zhang’s 2017 short story collection Sour Heart chronicles the rough-and-tumble lives of recently immigrated Chinese-Americans living in downtown Manhattan. The stories in this collection are told from the perspectives of children, and the narrative takes full advantage of the impish, filterless way in which children relate their own experiences to themselves and others.

In “We Love You Crispina”, young Christina’s life in a crowded Washington Heights tenement block is refracted through her naive, contradictory understandings of the world. Her parents are struggling to get a leg up and are contemplating sending her back to Shanghai — but Christina is more concerned with how the bed bugs in their cramped apartment are making her itchy, and dissecting the interactions she has in the school playground. It’s a wonderfully nuanced exercise in contrast, as well as a reminder of what feels most important to us when we’re small, rendered potently through Christina’s 'anecdotal' voice.

What short story should you read next?

Find out here! Takes 30 seconds

An experiment with genre

Short stories, by nature, are more flexible pieces of fiction that aren’t wedded to the diktat of longer-form fiction. It means they can play around with and challenge the expectations of a genre’s expected conventions, in a relatively ‘low stakes’ way compared to a full-blown novel.

Oftentimes, an experiment won’t be a complete reinvention of the genre. Instead, one might find a refreshing twist on a classic trope — or, as in the example below, upping the ante and taking a genre to heights it has never been before.

Example #4: “A Good Man is Hard to Find” by Flannery O’Connor

This short story sent shock waves through the American literary establishment when it was first published in 1953. It follows a Southern family on a road trip to visit the children’s grandmother — who end up crashing their car and happening upon a mysterious group of men. I won’t spoil the rest for you, but one word of warning: don’t expect a happy ending.

“A Good Man Is Hard To Find” incorporates common themes of Southern gothic literature , like religious imagery, and — surprise surprise — characters meeting a gruesome demise, but its controversial final scene marks it out. The macabre detail was shocking to audiences at the time but is now held up as a stellar example of the genre (and also exemplifies how a well-executed bit of subversion can become the golden standard in literature!). You might want to sleep with one eye open after reading this, but that’s half the point, right?

An exercise in extreme brevity

How many words do you actually need to tell a great story? If you were to ask that to someone who writes flash fiction , they tell you "fewer than 1,000 words."

The defining element that sets flash fiction apart from the standard-issue short story — other than word count — is that much more needs to be implied, rather than said upfront. Flash fiction, and especially mega-short microfiction, perfectly embody this principle of inference, which itself derives from Ernest Hemingway ’s Iceberg Theory of story development.

Example #5 “Curriculum” by Sejal Shah

“ Curriculum ”, clocking in at exactly 500 words, is a great sampling of the emotional, personal language that appears frequently in flash fiction. A handkerchief, some cream cloth, and a pair of glasses become important symbols around which Shah contemplates identity and womanhood, in the form of a series of questions that follow her descriptions of the objects.

This kind of deliberate, highly considered structure ensures that Shah’s flash fiction makes a razor-sharp point, whilst also allowing for a contemplative tone that transcends the words on the page. When done well, this style of short fiction can be a greater-than-expected vehicle for thoughtful comments on a range of issues.

If you’re in the mood to read more around the form, check out our picks for the 31 best short stories .

As you can see, the short story is an art form on its own that requires deftness, clarity, and a strong grasp of how to make an economy of words compelling and innovative. If you’re feeling ready to write a short story of your own, proceed to the next post in this series.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

We have an app for that

Build a writing routine with our free writing app.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

Columns > Published on June 6th, 2024

How to Write a Short Story in 9 Simple Steps

The joy of writing short stories is, in many ways, tied to its limitations. Developing characters, conflict, and a premise within a few pages is a thrilling challenge that many writers relish — even after they've "graduated" to long-form fiction.

In this article, I’ll take you through the process of writing a short story, from idea conception to the final draft.

But first, let’s talk about what makes a short story different from a novel.

1. Know what a short story is versus a novel

The simple answer to this question, of course, is that the short story is shorter than the novel, usually coming in at between, say, 1,000-15,000 words. Any shorter and you’re into flash fiction territory. Any longer and you’re approaching novella length.

As far as other features are concerned, it’s easier to define the short story by what it lacks compared to the novel. For example, the short story usually has:

- fewer characters than a novel

- a single point of view, either first person or third person

- a single storyline without subplots

- less in the way of back story or exposition than a novel

If backstory is needed at all, it should come late in the story and be kept to a minimum.

It’s worth remembering, too, that some of the best short stories consist of a single dramatic episode in the form of a vignette or epiphany.

2. Pick a simple, central premise

A short story can begin life in all sorts of ways.

It may be suggested by a simple but powerful image that imprints itself on the mind. It may derive from the contemplation of a particular character type — someone you know perhaps — that you’re keen to understand and explore. It may arise out of a memorable incident in your own life.

But in most of these cases, it seems to me, the first heartbeat (the “throb,” as Vladimir Nabokov puts it) of a new story is similar: it’s a brief capsule premise that contains within itself the germ of a more complex and sophisticated narrative.

For example:

- Kafka began “The Metamorphosis” with the intuition that a premise in which the protagonist wakes one morning to find he’s been transformed into a giant insect would allow him to explore questions about human relationships and the human condition.

- Herman Melville’s “Bartleby the Scrivener” takes the basic idea of a lowly clerk who decides he will no longer do anything he doesn’t personally wish to do, and turns it into a multi-layered tale capable of a variety of interpretations.

When I look back on some of my own short stories, I find a similar dynamic at work: a simple originating idea slowly expands to become something more nuanced and less formulaic.

So how do you find this “first heartbeat” of your own short story? Here are several ways to do so.

Experiment with writing prompts

Eagle-eyed readers will notice that the story premises mentioned above actually have a great deal in common with writing prompts like the ones put forward each week in Reedsy’s short story competition . Try it out! These prompts are often themed in a way that’s designed to narrow the focus for the writer so that one isn’t confronted with a completely blank canvas.

Turn to the originals

Take a story or novel you admire and think about how you might rework it, changing a key element. (“Pride and Prejudice and Vampires” is perhaps an extreme product of this exercise.) It doesn’t matter that your proposed reworking will probably never amount to more than a skimpy mental reimagining — it may well throw up collateral narrative possibilities along the way.

Keep a notebook

Finally, keep a notebook in which to jot down stray observations and story ideas whenever they occur to you. Again, most of what you write will be stuff you never return to, and it may even fail to make sense when you reread it. But lurking among the dross may be that one rough diamond that makes all the rest worthwhile.

3. Build a small but distinct cast of characters

Like I mentioned earlier, short stories usually contain far fewer characters than novels. Readers also need to know far less about the characters in a short story than we do in a novel (sometimes it’s the lack of information about a particular character in a story that adds to the mystery surrounding them, making them more compelling).

Yet it remains the case that creating memorable characters should be one of your principal goals. Think of your own family, friends and colleagues. Do you ever get them confused with one another? Probably not.

Your dramatis personae should be just as easily distinguishable from one another, either through their appearance, behavior, speech patterns, or some other unique trait. If you find yourself struggling, a character profile template like the one you can download for free below is particularly helpful in this stage of writing.

- “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman features a cast of two: the narrator and her husband. How does Gilman give her narrator uniquely identifying features?

- “The Tell-Tale Heart” by Edgar Allan Poe features a cast of three: the narrator, the old man, and the police. How does Poe use speech patterns in dialogue and within the text itself to convey important information about the narrator?

- “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” by Flannery O’Connor is perhaps an exception: its cast of characters amounts to a whopping (for a short story) nine. How does she introduce each character? In what way does she make each character, in particular The Misfit, distinct?

4. Begin writing close to the end

It was Kurt Vonnegut who said you should start as close to the story end as possible.

He’s right: avoid the preliminary exposition or extended scene-setting. Begin your story by plunging straight into the heart of the action. What most readers want from a story is drama and conflict, and this is often best achieved by beginning in media res . You have no time to waste in a short story. The first sentence of your story is crucial, and needs to grab the reader’s attention to make them want to read on.

One way to do this is to write an opening sentence that makes the reader ask questions. For example, Kingsley Amis once said, tongue-in-cheek, that in the future he would only read novels that began with the words: “A shot rang out.”

This simple sentence is actually quite telling. It introduces the stakes: there’s an immediate element of physical danger, and therefore jeopardy for someone. But it also raises questions that the reader will want answered. Who fired the shot? Who or what were they aiming at, and why? Where is this happening?

We read fiction for the most part to get answers to questions. For example, if you begin your story with a character who behaves in an unexpected way, the reader will want to know why he or she is behaving like this. What motivates their unusual behavior? Do they know that what they’re doing or saying is odd? Do they perhaps have something to hide? Can we trust this character?

As the author, you can answer these questions later (that is, answer them dramatically rather than through exposition). But since we’re speaking of the beginning of a story, at the moment it’s enough simply to deliver an opening sentence that piques the reader’s curiosity, raises questions, and keeps them reading.

5. Shut out your internal editor

“Anything goes” should be your maxim when embarking on your first draft.

By that, I mean: kill the editor in your head and give your imagination free rein. Remember, you’re beginning with a blank page. Anything you put down will improve what’s currently there, which is nothing. And there’s a prescription for any obstacle you might encounter at this stage of writing.

- Worried that you’re overwriting? Don’t worry. It’s easier to cut material in later drafts once you’ve sketched out the whole story.

- Got stuck, but know what happens later? Leave a gap. There’s no necessity to write the story sequentially. You can always come back and fill in the gap once the rest of the story is complete.

- Have a half-developed scene that’s hard for you to get onto the page? Write it in note form for the time being. You might find that it relieves the pressure of having to write in complete sentences from the get-go.

Most of my stories were begun with no idea of their eventual destination, but merely an approximate direction of travel. To put it another way, I’m a ‘pantser’ (flying by the seat of my pants, making it up as I go along) rather than a planner. There is, of course, no right way to write your first draft. What matters is that you have a first draft on your hands at the end of the day.

6. Finish the first draft

It’s hard to overstate the importance of the ending of a short story: it can rescue an inferior story or ruin an otherwise superior one.

If you’re a planner, you will already know the broad outlines of the ending. If you’re a pantser like me, you won’t — though you’ll hope that a number of possible endings will have occurred to you in the course of writing and rewriting the story!

In both cases, keep in mind that what you’re after is an ending that’s true to the internal logic of the story without being obvious or predictable. What you want to avoid is an ending that evokes one of two reactions:

- “Is that it?” aka “The author has failed to resolve the questions raised by the story.”

- “WTF!” aka “This ending is simply confusing.”

7. Edit the short story

Like Truman Capote said, “Good writing is rewriting.”

Once you have a first draft, the real work begins. This is when you move things around, tightening the nuts and bolts of the piece to make sure it holds together and resembles the shape it took in your mind when you first conceived it.

In most cases, this means reading through your first draft again (and again). In this stage of editing, think to yourself:

- Which narrative threads are already in place?

- Which may need to be added or developed further?

- Which need to perhaps be eliminated altogether?

All that’s left afterward is the final polish. Here’s where you interrogate every word, every sentence, to make sure it’s earned its place in the story:

- Is that really what I mean?

- Could I have said that better?

- Have I used that word correctly?

- Is that sentence too long?

- Have I removed any clichés?

Trust me: this can be the most satisfying part of the writing process. The heavy lifting is done, the walls have been painted, the furniture is in place. All you have to do now is hang a few pictures, plump the cushions and put some flowers in a vase.

8. Share the story with beta readers

Eventually, you may reach a point where you’ve reread and rewritten your story so many times that you simply can’t bear to look at it again. If this happens, put the story aside and try to forget about it.

When you do finally return to it, weeks or even months later, you’ll probably be surprised at how the intervening period has allowed you to see the story with a fresh pair of eyes. And whereas it might have felt like removing one of your own internal organs to cut such a sentence or paragraph before, now it feels like a liberation.

The story, you can see, is better as a result. It was only your bloated appendix you removed, not a vital organ.

It’s at this point that you should call on the services of beta readers if you have them. This can be a daunting prospect: what if the response is less enthusiastic than you’re hoping for? But think about it this way: if you’re expecting complete strangers to read and enjoy your story, then you shouldn’t be afraid of trying it out first on a more sympathetic audience.

This is also why I’d suggest delaying this stage of the writing process until you feel sure your story is complete. It’s one thing to ask a friend to read and comment on your new story. It’s quite another thing to return to them sometime later with, “I’ve made some changes to the story — would you mind reading it again?”

9. Submit the short story to publications

So how do you know your story’s really finished? This is a question that people have put to me. My reply tends to be: I know the story’s finished when I can’t see how to make it any better.

This is when you can finally put down your pencil (or keyboard), rest content with your work for a few days, then submit it so that people can read your work. And you can start with this directory of literary magazines once you're at this step.

The truth is, in my experience, there’s actually no such thing as a final draft. Even after you’ve submitted your story somewhere — and even if you’re lucky enough to have it accepted — there will probably be the odd word here or there that you’d like to change.

Don’t worry about this. Large-scale changes are probably out of the question at this stage, but a sympathetic editor should be willing to implement any small changes right up to the time of publication.

About the author

Robert Grossmith is a UK writer based near Norwich. In addition to his short stories, he has also published two novels as well as poems, scholarly articles and (as Bob Grossmith) book reviews. He has a BA in Philosophy & Psychology and a PhD on Vladimir Nabokov, and worked for many years as a lexicographer at Collins Dictionaries. He is now semi-retired and works part-time as a freelance fiction editor for authors .

Similar Columns

Explore other columns from across the blog.

Book Brawl: Geek Love vs. Water for Elephants

In Book Brawl, two books that are somehow related will get in the ring and fight it out for the coveted honor of being declared literary champion. Two books enter. One book leaves. This month,...

The 10 Best Sci-Fi Books That Should Be Box Office Blockbusters

It seems as if Hollywood is entirely bereft of fresh material. Next year, three different live-action Snow White films will be released in the States. Disney is still terrorizing audiences with t...

Books Without Borders: Life after Liquidation

Though many true book enthusiasts, particularly in the Northwest where locally owned retailers are more common than paperback novels with Fabio on the cover, would never have set foot in a mega-c...

From Silk Purses to Sows’ Ears

Photo via Freeimages.com Moviegoers whose taste in cinema consists entirely of keeping up with the Joneses, or if they’re confident in their ignorance, being the Joneses - the middlebrow, the ...

Cliche, the Literary Default

Original Photo by Gerhard Lipold As writers, we’re constantly told to avoid the cliché. MFA programs in particular indoctrinate an almost Pavlovian shock response against it; workshops in...

A Recap Of... The Wicked Universe

Out of Oz marks Gregory Maguire’s fourth and final book in the series beginning with his brilliant, beloved Wicked. Maguire’s Wicked universe is richly complex, politically contentious, and fille...

Bring your short stories to life

Fuse character, story, and conflict with tools in the Reedsy Book Editor. 100% free.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Short Story

Short story definition, features of a short story, difference between short story, novella, and novel, how to write and plot a short story, five (5) major elements of a short story, examples of short stories from literature, short story meaning and function, synonyms of short story, related posts:, post navigation.

9 Key Elements of a Short Story: What They Are and How to Apply Them

by Sarah Gribble | 1 comment

If you're new to short story writing, it can be intimidating to think of fitting everything you need in a story into a small word count. Are there certain elements of a short story you'll need to know in order for your story to be great?

Writers struggle with this all the time.

You might want to develop deep character backgrounds with a huge cast of characters, amazing settings, and at least two subplots. And that's great. But that wouldn't be writing a short story.

You might try to cut some of these things, and then all the sudden you don't have a character arc or a climax or an ending.

Every story has basic elements; a short story's basic elements are just more focused than a novel's. But all those elements must be there, and yes, they need to fit into a short word count.

In this article, you'll learn what you need to make sure your short story is a complete story—with three famous short story examples. These story elements are what you should focus on when writing a short piece of fiction.

The Key to Compelling Stories: It's NOT Dun, Dun, DUUN!

When I first started writing, I mainly worked on horror short stories. I wanted to create that dun, dun, DUUUN! moment at the end of all of them. You know the one. In the movies it's where the screen goes to black and you’re left feeling goosebumps.

I remember the first writing contest I entered (right here at The Write Practice!), I submitted a story that I thought was pretty decent, but didn’t really think would win.

I was right; it did not win.

But mainly I wanted the upgrade I’d purchased: feedback from the judge. She was great and told me my writing was good and tight, but there was one major issue with my story.

The dun, dun, DUUN!

I’d tried to cultivate actually meant my story just . . . cut off. There was no ending. There wasn’t even a complete climax. I got it ramped up and then just . . . stopped.

That feedback changed me as a short story writer. It made me really pay attention to what needed to be in a story versus what was unnecessary.

I studied short stories. I made note of what an author did and where. I basically taught myself story structure.

This may seem obvious, but a short story, even though it’s short, still needs to be a story.

So let’s start with the basics.

P.S. If you want to learn more about the five major steps you need to complete to write a short story, read this article .

What Is a Story?

I know a man who consistently tells stories during parties. (Sort of like this guy !)

He starts out well but then goes off on tangent after tangent, ultimately not really getting to any sort of point.

New people (re: characters ) are introduced, then dropped. New events are mentioned, but not resolved. By the time he gets to the end of his “stories,” eyes have glazed over and the “punchline,” as it were, falls flat.

What this man is telling is a short story, and he’s doing it terribly.

A story, no matter the length, can be boiled down to a character wanting something, having a hard time getting it, and finally either getting it or not.

Stories are actually simple when you look at the basics. This is why writing short stories will make you a better writer.

Short stories force a writer to practice nailing structure and pace. If you nail those things, you’ll be able to write stories of any length (and not bore people at parties).

And like novel-length stories, short stories contain certain elements in order to hold up the structure and pace.

For each story element below, I'll use three classic stories as examples:

- Shirley Jackson's “The Lottery”

- Edgar Allen Poe's “The Cask of Amontillado”

- O. Henry's “The Gift of the Magi”

Take a few minutes to refresh your memory by clicking on the links of each, if you wish.

9 Key Elements of a Short Story

When it comes down to the elements of a short story, focus on nine key elements that determine if the short story is a complete story or a half-baked one.

1. Character

Characters in books are well-drawn. There's a lot of time spent on character development and backstory. That's not needed for short stories.

Short stories need one central character and one or two other major characters. That’s about it. There isn't enough room to have a ton of characters and a story will veer away from the central plotline if a large cast is present.

The reader doesn't need to know everything about this character . They don't even need to know their physical appearance if it's not vital to the story. Your character traits in short stories can be so minimal, they don't even need a name.

This doesn't mean the protagonist is a static character who is basically a zombie on a couch. They still have to be a dynamic character, one that changes throughout the story.

When you're thinking of character creation for short stories, you don't need to dive into too much detail. Two to three character details are normally enough.

See how the three short story examples used in this article develop characters:

The Lottery

The main character is Tessie Hutchinson.

We don't know much about Tessie, other than she's unkempt and arrives late with a slew of jokes. You'll no doubt note here that this story has a lot of characters, not just two or three.

But notice only a few of the other characters are fleshed out much at all. The other characters of note here are:

- Mr. Hutchinson

- Mr. Summers

- Old Man Warner.

The Cask of Amontillado

This short story has significantly fewer characters:

- The main character

The Gift of the Magi

There are only two named characters:

- Della, the main character

- Jim, Della's husband

2. Want/Goal

The central character needs to want something—even if it’s a glass of water, as Kurt Vonnegut famously said. (They can also not want something. But they have to have an opinion either way.) The story is their quest to get said something.

Obviously, in real life people want multiple things, often at once and often in contrast to each other. But in a short story, the goal needs to be focused and relatively simple.

This want/goal is important to the story plot. This is what drives the character's decisions as they move throughout the space of your story. The goals in the short story examples are:

Tessie, as with every other person who shows up at the lottery, doesn't want to get chosen.

Montresor wants revenge for an insult Fortunato threw his way while drunk.

Della wants to give her husband a Christmas gift.

3. Conflict

Obstacles and complications need to make the protagonist's journey hard, and these types of conflicts should raise the stakes as the protagonist tries to achieve their want/goal.

In books, multiple things need to get in the way of the character completing the goal, but in short stories, there can be as little as one central conflict .

Conflict stems from the antagonist, whether that’s an external baddie (character conflicts with each other), an internal issue, forces of nature, or society being against them. Here's how conflict works in our three examples:

The Lottery

Tessie conflicts with the other townsfolk, her husband (who is more rule-abiding than she is), and the overall way of life the lottery is forcing.