How to Write a Customer Service Resume Objective with Examples

Quick Navigation:

Why is a strong customer service resume objective important?

How to write a customer service resume objective, examples of well-written resume objectives for customer service, examples of customer service resume objectives that are not well-written.

Customer service jobs can be competitive, and dozens of people may send in applications for the same position. A strong resume objective that shows an employer how useful you can be to the company can help you distinguish yourself from applicants who are responding to the same customer service position.

Generally, you should include your relevant qualifications, skills, experience and most notable past successes in your resume objective. Be sure to condense all the relevant information into an attention-grabbing statement. A good customer service objective should be no more than two or three sentences. This way, the employer can quickly and easily see how you’re qualified for the job.

You can create your resume objective for a customer service position by following these steps:

1. First, consider your qualifications

Take inventory of your prior experience, skills, qualifications and expertise, and include the most impressive accomplishments in your objective.

2. Second, use numbers to showcase your past achievements

Include quantifiable data and metrics that demonstrate the impact you had in past positions, such as the number of new accounts you opened, the volume of business you generated or the customer retention rate you helped your previous company achieve.

3. Next, highlight relevant skills

Indicate desirable skills or qualifications that show your usefulness to the company. Choose relevant skills such as communication, teamwork and time management.

4. Lastly, explain your experience

It can help to state how many years of work experience you have in customer service, especially if you’re looking for a leadership position.

Here are some examples of effective resume summaries that you can use as a guideline when writing your own:

‘Secure a job as a customer service representative with Seven Seas Company, which will enable me to use my communication skills and interpersonal skills to serve customers. Good problem solver, able to multitask and consistently finishes projects before their deadlines.’

‘Obtain a job as a customer representative where I can use my exceptional interpersonal and communication skills to resolve customer issues and foster a positive relationship between the customers and the company.’

‘Diligent and personable customer service representative seeking a position in which my communication skills combined with my problem-solving skills can be useful in serving customers. Capable of handling multiple tasks in a fast-paced environment. Able to keep customers happy and smiling while resolving their issues in the shortest time possible.’

‘Experienced customer care professional with three years of experience in the telecommunications industry. Now seeking a challenging but rewarding role in a position where I can use my interpersonal skills to provide the highest level of support to customers of DataSecure, LLC.’

‘Seeking a customer service position with NextGen Corporation to use my excellent customer service experience and people-oriented skills to enhance customer loyalty and deepen client relationships.’

Example 6

‘Customer service representative with five years’ experience providing excellent services to customers in a dynamic work environment. Solid communication skills, good interpersonal skills and fast in resolving customer complaints with excellent problem-solving skills.’

‘Confident and energetic customer service representative passionate about serving customers. Thrives in a challenging and fast-paced environment. Able to interact freely with customers and resolve issues quickly. Now looking for a rewarding position where I can serve customers and increase customer retention.’

‘Self-driven customer service professional with over 10 years of experience working in a dynamic call center. Strong verbal and written communication skills. Passionate about building lasting relationships with customers.’

‘Experienced customer service coordinator with strong leadership skills. Able to design, implement and maintain cost-effective shift schedules for Telkom’s call center of more than 200 customer representatives. Efficient in managing and tracking client’s attendance records. Results-oriented professional who’s able to ensure customer representatives deliver an outstanding experience.’

‘Detail-oriented professional with over four years of experience in a busy customer-service environment. Proven ability to handle customer issues quickly and discreetly while nurturing positive relationships and increasing customer retention rates by 54%. Seeking to leverage these skills as a reliable customer service representative.’

Example 11

‘Customer service representative with three years of experience in a busy IT help desk. Holds a bachelor’s degree in IT. Seeking to use my diagnostic skills and troubleshooting skills to help customers resolve a range of computer and networking problems.’

‘Seeking a customer service representative position where I can use my experience and communication skills to handle customer complaints and queries and deepen the relationship with customers.’

Example 13

‘Qualified customer service professional with over 14 years of experience in customer care roles, including sales, tech support and customer care. Good listener, astute problem solver and confident on the phone. Proficient with various CRM tools. Seeking to use my customer service skills to provide a positive experience to the customers in your firm.’

‘Personable and articulate customer care professional with a history of providing outstanding support to customers. Able to maintain a positive attitude when serving customers in the banking hall. Possesses good judgment and the ability to handle confidential information discreetly. Seeking a customer service role within a financial institution that offers rewarding opportunities for dedicated people.’

‘Customer-centric professional with three years of experience serving customers in different roles. Proven ability in engaging customers, resolving complaints and strengthening customer-client relationships. Seeking a rewarding position with a company that values its customers.’

Here are some examples of poor resume objectives:

‘Seeking a position as a customer service representative in a fast-growing company.’

The above resume objective doesn’t indicate the applicant’s qualifications or skills, which gives the employer no way to know what value they would bring to the company.

‘To obtain a customer service position with a company, which will require me to use my skills for the company’s success.’

Not only is this objective vague and generic, but it also doesn’t highlight the applicant’s experience and skills. It also doesn’t state what value they bring to the company.

‘Secure any position that requires me to use my interpersonal skills and analytical mind to resolve customer issues and complaints.’

While this objective states how the applicant’s skills are of value, it doesn’t clearly state the position they’re applying for.

In general, a poorly-written resume objective leaves out relevant details, doesn’t state the position being applied for, or otherwise fails to show how the applicant’s skills will benefit the employer.

30 Top Customer Service Resume Objective Examples + Sample

Your resume objective is your first chance to make an impression on a hiring manager.

For customer service roles, your objective highlights your top skills and experience.

It shows how you can provide excellent service that improves customer satisfaction.

This article will provide 30 examples of effective customer service resume objectives.

We’ll also discuss how to write a strong objective tailored to your own background.

With these tips, you can craft an objective that will grab attention and land more interviews.

Read Also : How to Apply for a Schlumberger Internship

How to Write a Customer Service Resume Objective

Your objective sits at the top of your resume under the header with your name and contact information.

It is usually 3-4 lines long and written in first person. Follow these best practices when writing your customer service resume objective:

1. Focus on the employer’s needs

Demonstrate how your skills will benefit the company and add value. Show how you can help improve customer experience and satisfaction.

2. Include relevant skills and experience

Mention professional strengths like communication, problem-solving, and product knowledge. Highlight any previous customer service experience you have.

3. Customize for each job

Tweak your objective to use keywords from the job description. Align your objective closely with the required qualifications.

4. Be concise and direct

Keep your objective short, clear, and easy to scan. Get right to the point of how you are a great fit for this role.

30 Customer Service Resume Objective Examples

Here are 30 resume objective examples you can reference to help craft your own:

Customer Service Resume Objective that Reflects Dedication to Work

1. Customer service representative with 5 years experience delivering excellent support. Seeking to leverage proven customer satisfaction skills to boost retention and loyalty for ACME Company.

2. Energetic customer service professional skilled in resolving complaints and calming frustrated customers. Eager to provide outstanding service and communication for customers and colleagues at XYZ Corp.

3. Reliable customer care agent adept at solving problems, answering questions, and improving customer experiences. Excited to provide quick and accurate support to customers of ABC Company.

4. Resourceful customer support specialist with 3 years experience in the e-commerce industry. Motivated to apply empathy, product knowledge, and patience to improve customer satisfaction for Acme Co.

5. Customer-focused rep with a background in retail sales and service. Skilled at building rapport, de-escalating conflicts, and exceeding customer expectations daily. I hope to bring these strengths to the customer service team at XYZ Company.

6. Enthusiastic customer care professional seeking a role at ABC Corporation. 2 years experience providing knowledgeable support with excellent listening and communication abilities. Ready to deliver fast and accurate solutions to customer inquiries.

7. Personable client services agent with a background in hospitality and administrative support. Able to connect well with clients to understand their needs. Seeking to apply these interpersonal abilities to benefit the customer service department at Acme Inc.

8. Dedicated customer support representative with a proven track record of resolving issues and improving satisfaction. Excited to leverage 4 years of experience and excellent communication skills to benefit ABC Company and their clients.

9. Dependable customer care specialist skilled in troubleshooting technical issues and calming upset clients. Seeking a position at XYZ Corp to utilize conflict resolution abilities and deliver empathetic customer support.

Customer Service Resume Objective That Reflects Problem-Solving Skills

10. Customer-focused representative with 3 years of managing high-volume call centers. Driven to apply active listening and problem-solving skills to improve customer loyalty for Acme Company.

11. Inbound call center agent passionate about providing exceptional service on every call. Savvy with CRM platforms, troubleshooting tech issues, and documenting interactions. I hope to join XYZ’s mission of quality support through diligent communication and follow-up.

12. Driven customer support professional successful at upselling products based on customer needs. Known for patience and empathy when assisting frustrated clients. Pursuing a role at ABC Co. to grow sales through excellent service.

13. Call center representative experienced in insurance and financial services support. Skilled at explaining complex policies and managing busy call queues. Seeking to leverage industry knowledge and multitasking strengths to benefit customers at Acme Inc.

14. Customer retention specialist eager to bring 4 years of experience to XYZ Company. Talented at addressing concerns, solving problems, and transforming dissatisfied clients into loyal brand advocates.

15. Polite customer care agent with excellent phone etiquette. Thrives in fast-paced environments juggling high call volumes. Hoping to deliver outstanding patience and product knowledge to support customers of ABC Inc.

16. Technical support representative well-versed in troubleshooting hardware and software issues. Adept at explaining intricate solutions in a simple, understandable manner. Looking to join Acme Co. to share tech knowledge and improve customer experiences.

17. Bilingual customer support rep fluent in Spanish and English. Background in hospitality service. Personable and cool under pressure. Seeking Spanish customer service role at growing XYZ Company.

18. Experienced customer service manager dedicated to agent development and optimal support operations. Known for reducing average handle times and improving first contact resolution. Excited to bring 5 years of expertise to the customer experience team at ABC Corp.

Customer Service Resume Objective that Shows Expertise

19. Custom service professional is driven by customer satisfaction and retention. Proven history of de-escalating issues and resolving complaints. Eager to leverage my skills to benefit Acme Inc. customers and exceed KPIs.

20. Reliable customer care specialist with a background in enterprise SaaS applications. Excited to apply software expertise and people skills to enable excellent customer support for XYZ Company users.

21. Motivated customer relations assistant able to manage high-volume inquiries with speed and accuracy. I can successfully using CRM systems and social media to engage clients. Seeking new challenges at ABC Inc. to further grow these capabilities.

22. Analytical customer care professional skilled in uncovering the roots of issues. Experienced kickstarting team initiatives to proactively address pain points and prevent future problems. Looking to collaborate with stakeholders at XYZ Corp for continuous improvement.

23. Composed customer service agent able to calmly handle hectic call center environments. Known for conflict resolution and stewardship of difficult clients. Eager to apply 3 years of experience to meet support goals at Acme Co.

24. Enthusiastic customer advocate with proven success driving brand loyalty. Skilled at establishing rapport and creating personalized experiences. Seeking new challenges and professional growth within ABC Company.

25. Diligent customer service specialist successfully managing enterprise accounts and VIP clients. I look forward to developing trusted advisor relationships with stakeholders at XYZ Inc.

Read Also : USA States with The Lowest Cost of Living and Highest Quality of Life

Customer Service Resume Objective That Reflects Language Skills

26. Upbeat customer support rep backed by 2 years of experience and a strong work ethic. Excel at troubleshooting tech problems with patience. Seeking role at growing Acme Inc. to contribute skills and gain knowledge.

27. Multilingual customer service professional fluent in English, Spanish, and French. Driven to apply cultural competence to creating global customer experiences at international XYZ Company.

28. Resourceful customer care agent skilled at collecting information to make accurate recommendations. Proficient in salesforce CRM. Excited to leverage client service experience at ABC Corp.

29. Friendly customer support representative able to diffuse anger and reduce churn. Known for follow-through and accountability with clients. Eager to build rapport and boost retention for Acme Inc.

30. Dedicated customer champion with 5 years of experience streamlining support operations. Proven results innovating new service solutions and improving CSAT for clients. Seeking leadership role at XYZ Company.

Customer Service Resume Objective Example

Here is an example of an effective customer service resume objective:

A customer-focused representative with 3 years of managing high-volume call centers. Driven to apply active listening and problem-solving skills to improve customer loyalty for Acme Company.

This objective highlights the candidate’s relevant customer service experience managing call centers.

It mentions their top skills like active listening and problem-solving.

The objective finishes by stating their goal of using these abilities to benefit the specific company they are applying to.

Your resume objective is key to making an effective first impression on hiring managers.

A strong customer service objective highlights your top skills and experience.

It convinces the employer you have what it takes to excel in the role and contribute to their goals.

Use the examples and tips in this article to craft an eye-catching objective tailored to each job opportunity.

With a compelling objective that grabs attention, you can get more interviews and land your dream customer service job.

Frequently Asked Questions

Here are answers to common questions job seekers have about writing resume objectives:

Should Customer Service Resumes Include an Objective?

Yes, objectives are highly recommended for customer service roles. They allow you to describe your strongest skills and abilities relevant to the position.

Customer service objectives help convince the employer you are the right candidate.

What Skills Should I Highlight in a Customer Service Objective?

The top skills to mention include communication, active listening, problem-solving, customer focus, empathy, and patience.

Mention skills that align with keywords from the job description. Quantify past experience in a number of years when possible.

How Should I Tailor My Customer Service Resume Objective for Each Job?

Research the company and role to identify important qualities being sought. Use keywords from the job ad in your objective.

Tweak it to highlight the experiences and abilities most relevant to that employer’s needs.

What Other Sections Should Be On My Customer Service Resume?

After your objective, include sections for your work history, education, relevant skills, and achievements.

Provide specific examples proving your customer handling abilities in your experience descriptions.

What Makes a Bad Customer Service Resume Objective?

Poor objectives are too generic and vague. They focus on your goals rather than the employer’s needs.

Avoid objectives that simply repeat the job title. Include details on your experience, knowledge, and abilities instead.

You may also like

Linkedin Job Slots vs. Job Posts: Which Are the Best

How to Announce Your New Job on LinkedIn (See Examples)

In-Demand Jobs: 20 Best Jobs in the Air Force

Top 6 Outplacement firms (Career Outplacement Services)

14 Best USA Recruitment Agencies that Recruit Foreign...

Day 1 CPT Colleges: Full List of Universities offering...

- Knowledge Base

- Free Resume Templates

- Resume Builder

- Resume Examples

- Free Resume Review

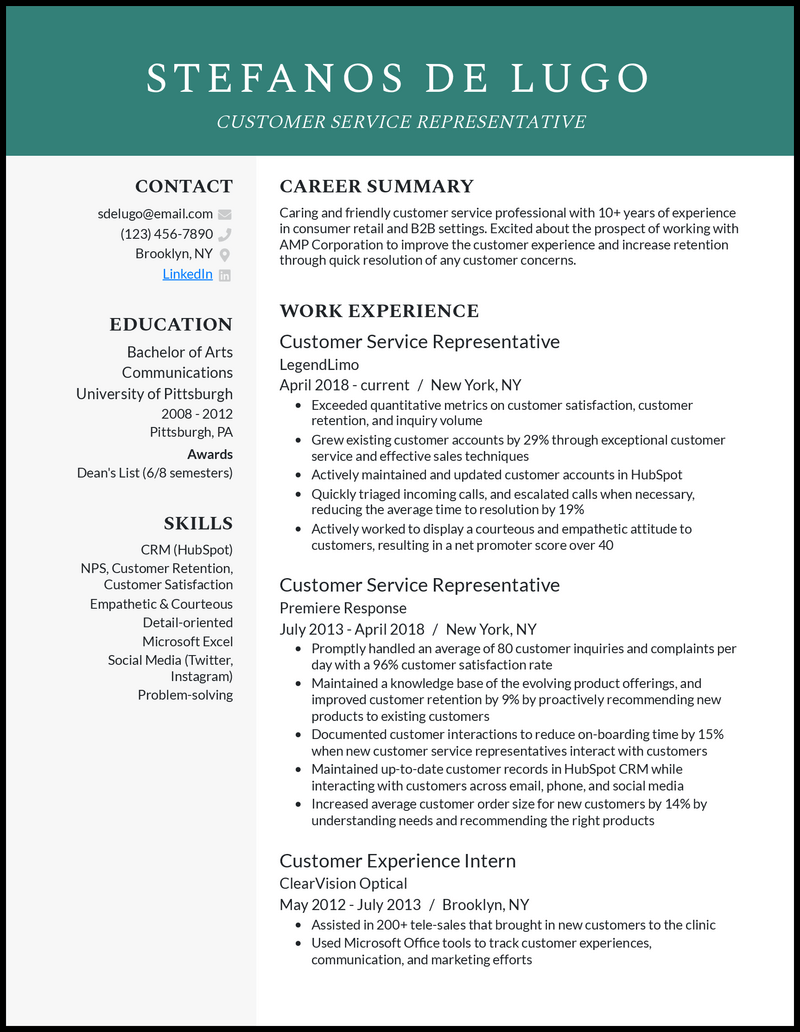

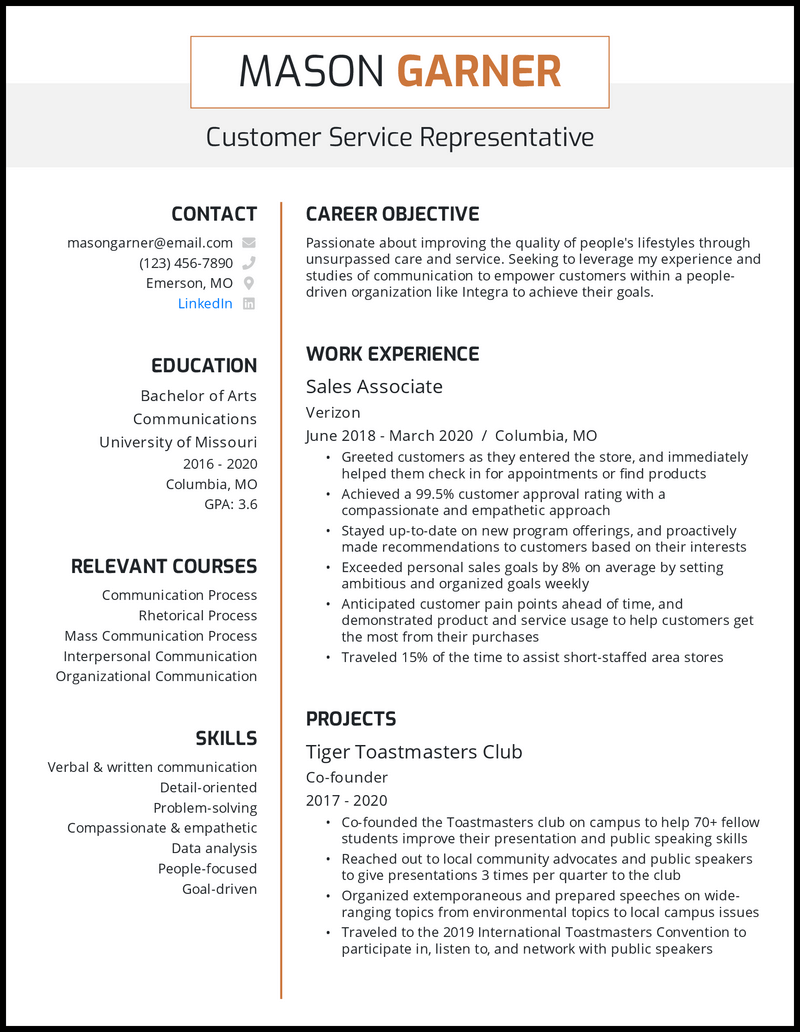

A strong resume is essential when it comes to landing a customer service job. On top of that, a well-crafted customer service resume objective can turn the events in your favor.

A customer service resume objective should be clear, concise, and compelling, and showcase how you can provide exceptional customer service and help the company achieve its goals.

We will provide tips and examples for crafting a compelling customer service resume objective that will make you a standout candidate.

- Define a customer service resume objective. How is it different from a summary?

- Why include a customer service resume objective?

- How to write a resume objective for customer service?

- What is a good objective for a customer service resume?

Definition & Purpose of Customer Service Resume Objective

A customer service resume objective is a brief statement at the top of your resume providing an overview of your career goals and the value you can bring to the table.

It should be tailored to the specific position you are applying for and highlight the skills and experience that align with the job description.

A customer service resume objective is different from a summary statement and professional profile.

A summary statement provides an overview of your career highlights and achievements, while a professional profile outlines your skills and expertise.

While a customer service resume objective is suitable for entry-level candidates, seasoned professionals would opt for a summary that highlights their expertise, achievements, and qualifications.

Also read : What is the step-by-step process of writing a customer service resume?

Importance of a Customer Service Resume Objective

We will break down the significance of a customer service resume objective for both job seekers and employers:

Importance of customer service resume objective for job seekers

- It allows you to tailor your resume to the specific job you are applying for, which shows potential employers your seriousness and commitment to the position.

- It can help you highlight your relevant skills and experience, increasing the likelihood of getting shortlisted via ATS and catching the employer’s attention.

- It can help you convey your enthusiasm for the position and your willingness to work hard.

Importance of customer service resume objective for employers

- It allows them to quickly gather if the applicant's career goals align with the company's mission and values.

- It provides a glimpse into the applicant's communication skills and level of professionalism.

Also read : Commonly asked interview questions for various customer service specialists: Customer service manager interview questions Customer service associate interview questions Customer service representative interview questions

5 Tips for Writing an Effective Customer Service Resume Objective

Here are 5 tips to keep in mind for crafting an effective customer service resume objective:

Keep it concise and specific : Your customer service resume objective should be brief and to the point, highlighting your key strengths and what you bring to the table as a customer service professional. Keep it up to 1 or 2 sentences, and avoid overusing jargon or buzzwords.

Tailor it to the job posting : Review the job posting carefully and tailor your customer service resume objective to match the requirements and qualifications mentioned. Use keywords from the job posting to help your resume parse and get noticed by the employer.

Highlight relevant skills and experience : Your customer service resume objective should showcase your relevant skills and experience as a customer service representative. This may include your ability to communicate effectively and resolve issues of difficult customers. Use specific examples of how you have demonstrated these skills in the past.

Use power verbs : Start your resume objective with action verbs to demonstrate your authority over a particular task and make your bullet point impactful. For example, instead of saying "I am looking for a customer service position," say "Seeking a customer service role where I can utilize my communication skills to improve customer satisfaction."

Avoid generic statements : Avoid using generic statements that could apply to any job seeker. Instead, make your resume objective unique to your skills and experience. For example, if you have experience working in a call center, you could say "Experienced call center representative seeking a position in a fast-paced customer service environment."

Also read : How to create a customer service associate resume?

Examples of Customer Service Resume Objectives

Crafting a strong customer service resume objective is crucial for impressing hiring managers and securing a job interview.

Here are some examples of effective customer service resume objectives that can help you land an entry-level job:

Seeking a customer service position with ABC company where I can leverage my communication and problem-solving skills to provide exceptional service to customers and contribute to the growth of the company.

This statement above clearly states the applicant's goal of obtaining a customer service position, highlights their relevant skills, and emphasizes their desire to contribute to the company's growth.

To obtain a customer service position in a fast-paced environment where I can utilize my multitasking and conflict resolution skills to exceed customer expectations and drive customer loyalty.

It is an effective customer service resume objective because it highlights the applicant's desired work environment, relevant skills, and goal of not only meeting but exceeding customer expectations.

Result-oriented customer service professional skilled at rendering effective and time-sensitive customer support in a high-pressure environment. Looking for an opportunity to utilize my customer-centric skills to provide top-notch service and contribute toward personal and professional growth.

Eager to utilize strong problem-solving abilities and a friendly demeanor in an entry-level customer service role to create positive customer experiences for [Company Name].

This objective expresses the candidate's eagerness without repeating the phrase. It emphasizes valuable attributes: problem-solving abilities and a friendly demeanor, aligning with entry-level roles.

Aiming to kick-start my career in customer service, I'll apply strong interpersonal skills and a genuine desire to meet customer needs. I'm eager to learn and grow with [Company Name].

This objective conveys the candidate's career aspirations without using the same phrase repeatedly. It highlights interpersonal skills and a willingness to learn and develop.

Aspiring customer service professional with a background in retail, looking to transfer my customer-centric approach and problem-solving skills to enhance the customer experience at [Company Name].

This objective communicates the candidate's aspirations and relevant experience without repeating the introductory phrase. It underscores the skills they aim to bring to the role and how they can benefit the company.

Also read : What are the roles and responsibilities of a customer service manager?

Key Takeaways

A customer service resume objective is a brief statement that highlights your career goals and how you can add value to a company in this field.

It is an essential component of your resume that can make a significant impact on a hiring manager's decision to call you in for an interview.

Including a customer service resume objective can be a valuable addition to your job application. It can help job seekers showcase their skills and enthusiasm, while also providing employers with a quick glimpse into the applicant's qualifications and career goals.

Remember to review and revise your resume objective for each job application to ensure it is tailored to the specific requirements of the position.

To optimize your customer service resume objective, use Hiration's next-gen ChatGPT-powered career platform, which offers a solution to every obstacle faced by job seekers across the US.

Try it out today to enhance your job search and take your career to the next level. You can also reach out to us at support{@}hiration{dot}com for any queries or concerns.

Share this blog

Subscribe to Free Resume Writing Blog by Hiration

Get the latest posts delivered right to your inbox

Stay up to date! Get all the latest & greatest posts delivered straight to your inbox

Is Your Resume ATS Friendly To Get Shortlisted?

Upload your resume for a free expert review.

How to Write a Customer Service Resume Objective (Examples Included)

Mike Simpson 0 Comments

By Mike Simpson

If you want to land a customer service job , you can’t assume your old resume will do. You need to make it engaging and intriguing, so having a standout customer service resume objective is a must. Otherwise, your application could get lost in the sea of other applicants.

Remember, as the coronavirus wreaks havoc across the nation, a stunning 22 million people became unexpectedly unemployed. Many started scrambling, trying to find opportunities that can help them weather the storm. And that led many to one particular niche: customer service.

From call centers to retail giants like Walmart and Home Depot , customer service jobs are available. In some cases, companies are hiring en masse. For example, after filling over 100,000 positions, Amazon still needs 75,000 more workers. And they aren’t the only company bringing on tens of thousands of new employees during the pandemic.

But, even with that many opportunities, you can’t throw in the towel when it comes to the quality of your application. There’s a ton of competition, so going the extra mile is still essential. Let’s take a look at how you can make your customer service resume objective stand out like a diamond in a sea of gravel.

What Is a Resume Objective?

Alright, before you get into how you’ll craft a stellar objective, let’s tackle this important question: what the heck is a resume objective?

In the simplest terms, it’s a statement that outlines your career goals. It’s more than just saying, “I want this job.” You applied, so that’s a given.

Instead, it’s a spot on your resume where you can showcase what you bring to the table but also provide insights into why you are pursuing this role. It lets the hiring manager know what you have your sights set on as well as why you’re an excellent fit.

If you’re interested in learning more, we’ve covered it in-depth in the past. So, let’s pivot this discussion and look at customer service resume objective statements specifically.

What is Unique About a Customer Service Resume Objective?

In many ways, a customer service resume objective is going to be substantially different from those other kinds of candidates use. Mainly, this is because customer service isn’t a technical capability. Instead, it’s a soft skill. You have to rely on a combination of capabilities to thrive in a customer service role, many of which have to do with your personality and mentality.

If you have prior customer service experience in a similar role, you might actually be able to bypass the objective statement. Usually, for customer service jobs, you only need to use this approach for certain reasons, including:

- You’re pivoting into customer service from a different field

- You’re an entry-level candidate new to the workforce

- You’ve got your eye on a specific position or job type

In any of those cases, using a customer service resume objective is a smart move. It lets you showcase that you have what it takes to excel, even if your work history is non-existent or doesn’t look like it aligns with the job.

Think of it this way. If you want to shift into customer service from another field, you have skills that transfer into this niche. But, since you used them in different ways, your work history might not make that abundantly clear.

With an objective statement, you can spotlight those transferable skills and assert your interest in applying them to the world of customer service. Not only are you showcasing critical capabilities, but you’re also telling the hiring manager why you are applying to this job (and not something in your previous niche).

Hiring managers can be skeptical if someone is transitioning to a new field. They might worry that you’re being a professional “tourist” and have no intention of staying long-term, for instance. With a resume objective , you can give them peace of mind by letting them know that isn’t true. Pretty amazing, right?

In most cases, a customer service resume objective isn’t required. Instead, it’s supplemental information that can help a hiring manager understand why they should take a chance on you, even if you’re new to customer service (or the workforce as a whole).

Common Mistakes When Writing a Customer Service Resume Objective

If you talk to some people and mention you put an objective statement on your resume, you’re going to get inundated with eye rolls.

Because, not long ago, all people did in their objectives was state the obvious: that they wanted the job. That was a huge mistake.

You know why that was so ridiculous. Because everyone knows you want the job. If you didn’t, then you wouldn’t have submitted an application. But, you did, so you must want the position, right? Yeah, it’s pretty obvious that you do.

But that wasn’t the only misstep people make. Another doozy?

Vague resume objectives.

While brevity can be your friend, ambiguity isn’t. If you think creating a generic statement is a good idea – mainly because you can use the same one every time you apply – you couldn’t be more wrong. Not only is that approach boring, but it also reduces relevancy. If your objective doesn’t speak to a specific position, you’re just wasting space.

Ultimately, whatever you do, avoid saying you want the job. Instead, you want to focus on your desire to use specific skills in ways that allow you to provide value in the role. That’s a much better approach.

Plus, make it specific. Look at the job description and tailor your objective. That way, it provides meaning, increasing the odds that the hiring manager will appreciate this resume addition.

3 Tips for Writing a Customer Service Resume Objective

If you want to write a stand out customer service resume objective, here are three tips you can use right now:

1. Embrace Brevity

When it comes to objective statements, short and sweet is the way to go. Try to limit yourself to a few sentences at most. You don’t want it to look like a giant block of text.

2. Talk Value

Your customer service resume objective needs to showcase the value you bring to the table. Consider how you can be an asset to the company above all else and focus on that.

3. Be Specific

You want your objective to include details, not generic overviews. Mention individual skills and achievements that relate to the role. It’s all about highlighting why you’re an exceptional candidate for this job , not customer service in general.

3 Customer Service Resume Objective Examples

Alright, now that you have an idea of how to write an objective statement, let’s show you how to put those tips to work. Here are three customer service resume objective examples, focusing on different roles in the field.

1. Entry Level

“Diligent and energetic sales professional looking to pivot into the customer service industry and leverage strong communication skills in a fast-paced role that directly enhances the customer experience at ABC Company.”

2. Middle Management

“Customer service professional with over five years of experience in the field and a proven ability to lead team members through challenging projects, boost customer relationships, and enhance both customer and employee retention. Seeking an opportunity to leverage leadership skills in a formal management role.”

3. Executive

“Twenty-year veteran of customer service management aiming to bring a proven track record of successful customer relationship building and employee development to enhance the customer experience, increase loyalty, and enhance performance.”

Putting It All Together

So, there you go. Now you know not just what a customer service resume objective is, but also when and how to use it. That’s powerful stuff as, when executed properly, it can help you stand out from the crowd.

While some may still think that an objective statement is a bit old-fashioned, remember, if it helps you showcase the value you bring, it can be a wise addition. Make it all about the company and hiring manager’s needs, and you might find yourself at the top of the resume pile.

Just keep in mind that if you have a decent amount of experience, the resume summary approach is generally the better choice. But, if you are pivoting into customer service, new to the workforce, or targeting one specific opportunity, an objective statement might be a difference-maker that lands you the interview.

Co-Founder and CEO of TheInterviewGuys.com. Mike is a job interview and career expert and the head writer at TheInterviewGuys.com.

His advice and insights have been shared and featured by publications such as Forbes , Entrepreneur , CNBC and more as well as educational institutions such as the University of Michigan , Penn State , Northeastern and others.

Learn more about The Interview Guys on our About Us page .

About The Author

Mike simpson.

Co-Founder and CEO of TheInterviewGuys.com. Mike is a job interview and career expert and the head writer at TheInterviewGuys.com. His advice and insights have been shared and featured by publications such as Forbes , Entrepreneur , CNBC and more as well as educational institutions such as the University of Michigan , Penn State , Northeastern and others. Learn more about The Interview Guys on our About Us page .

Copyright © 2024 · TheInterviewguys.com · All Rights Reserved

- Our Products

- Case Studies

- Interview Questions

- Jobs Articles

- Members Login

Resume Worded | Career Strategy

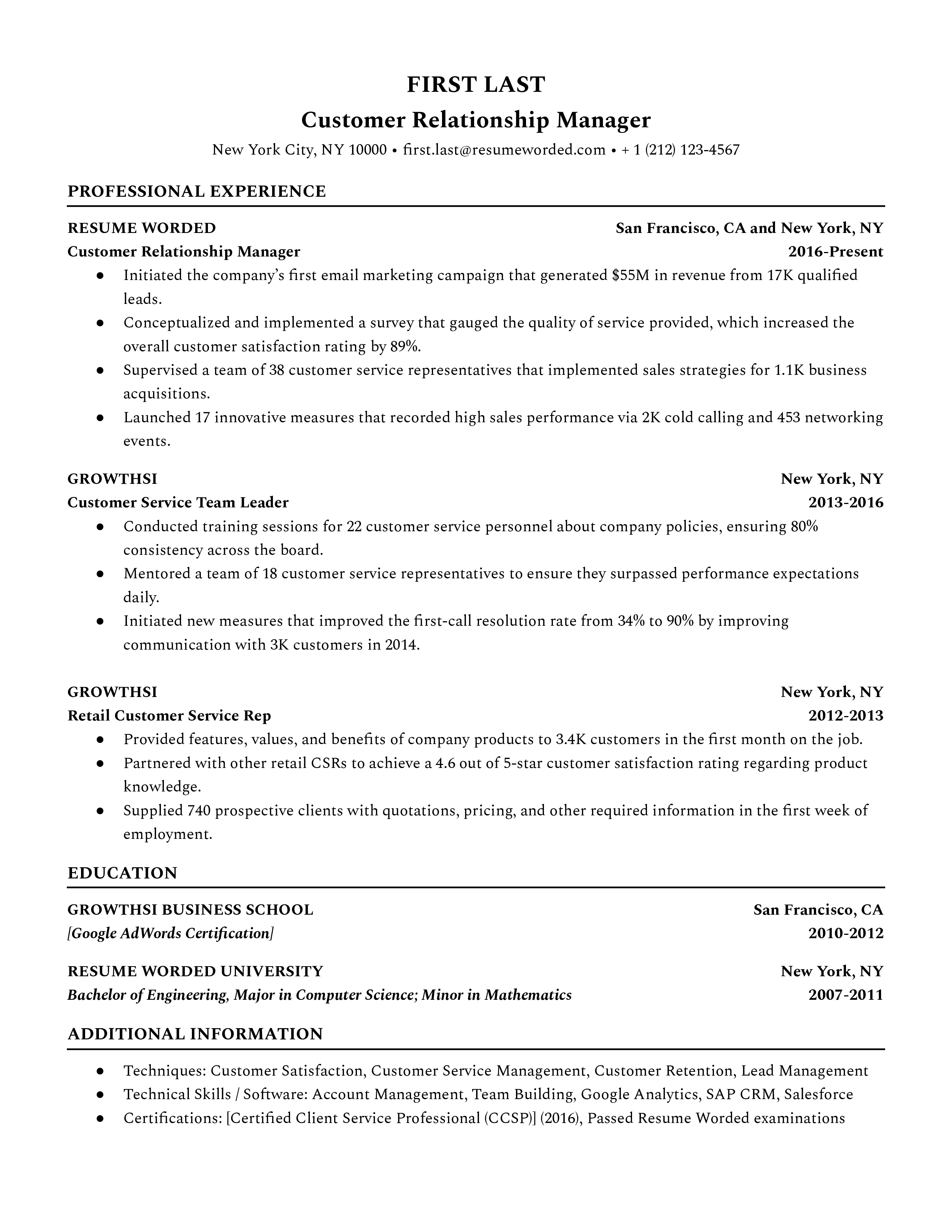

Customer service resume objective examples.

Curated by hiring managers, here are proven resume objectives you can use as inspiration while writing your Customer Service resume.

- Customer Service

- Career Changer into Customer Service

- Experienced Professional transitioning to Customer Service

- Recent Graduate for Customer Service

- Customer Service resume templates

- Similar objective examples

Customer Service Resume Objective Example

Highlighting years of experience.

Remember, experience can be a real game-changer. By stating your years of experience upfront, you're essentially saying that you're not a newbie. You've been in the trenches, and you know what it takes to get the job done. This can give you an edge over other applicants with less experience.

Showcasing Problem-Solving Skills

Customer service is about solving problems, so to show that you're a pro at this can win you big points. By highlighting your ability to resolve complex issues, you're sending a message that you're not easily flustered and can handle the heat under pressure.

Impressing with Satisfaction Rates

Numbers tell a story. By mentioning a high satisfaction rate, you're offering proof of your effectiveness in the role. It's one thing to say you're good at customer service, but it's another to show that 97% of customers were satisfied with your service. This makes your claim more credible.

Career Changer into Customer Service Resume Objective Example

Leveraging transferable skills.

When changing careers, it's important to highlight your transferable skills. By showing that your previous experiences allowed you to increase customer engagement, you're telling recruiters that you have the ability to attract and hold customers' attention, which is crucial in customer service.

Communicating Effectively

Communication is key in customer service. By demonstrating that you've implemented effective communication strategies in previous roles, you're showing that you understand the importance of clear, concise, and respectful communication in resolving customer issues and building relationships.

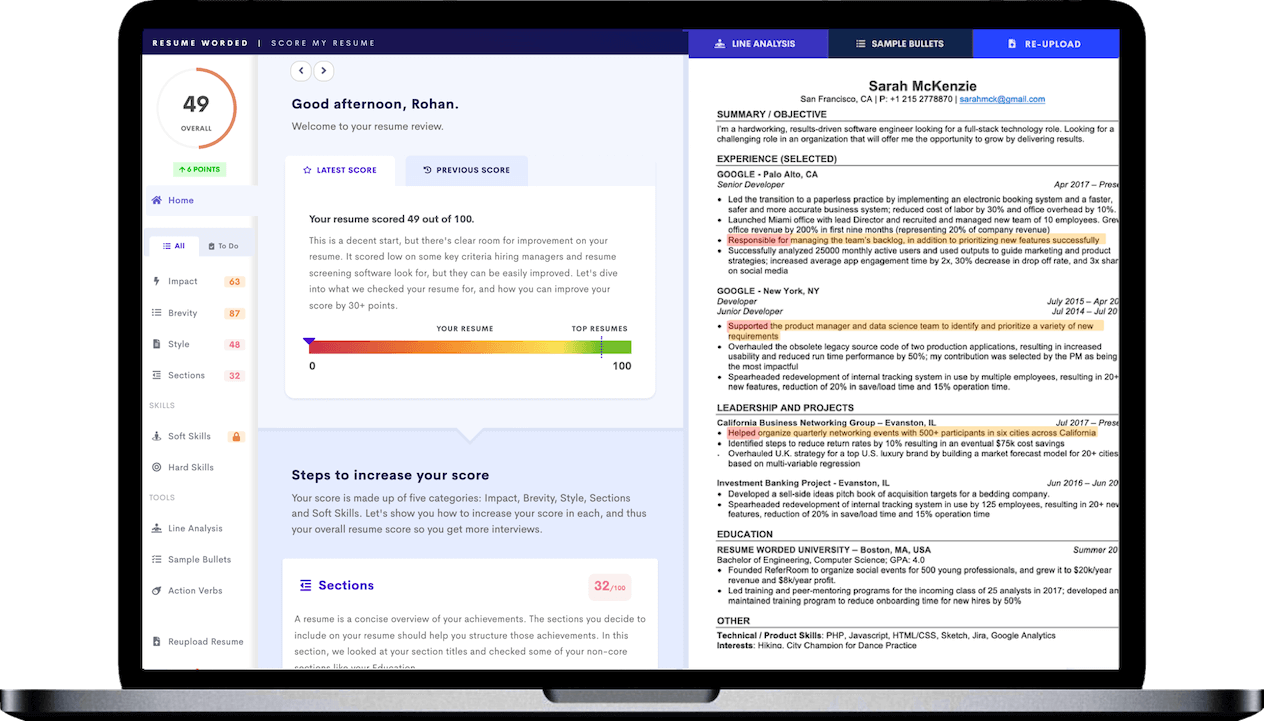

Crafting the perfect resume is a science. Our tool uses data from thousands of successful resumes in your industry to help you optimize yours. Get an instant score and find out how to make your resume stand out to hiring managers.

Experienced Professional transitioning to Customer Service Resume Objective Example

Leveraging leadership experience.

Even if you're transitioning to a different role, your leadership experience is still valuable. It shows that you understand the dynamics of a team and can guide others to achieve common goals. This can be particularly helpful if you're applying to a customer service role within a team environment.

Training and Motivating Teams

Showing your ability to train and motivate teams not only speaks to your leadership skills, but also your dedication to improving the overall performance of a team. This can translate well into a customer service role, as it shows your commitment to delivering the best possible service.

Increasing Customer Retention

Customer retention is paramount in any business. If you can show that you've been successful in keeping customers loyal, it shows that you understand the value of a long-term customer relationship and can create strategies to maintain it.

Recent Graduate for Customer Service Resume Objective Example

Demonstrating resilience.

Customer service can be tough. Customers can be difficult and even rude. By showcasing your ability to handle customer complaints, you're showing that you have the patience, resilience, and emotional intelligence to deal with challenging situations.

Driving Satisfaction

Customer satisfaction is the ultimate goal in customer service. By showcasing your ability to improve customer satisfaction, you're showing recruiters that you understand the significance of a satisfied customer and have the skills to achieve it.

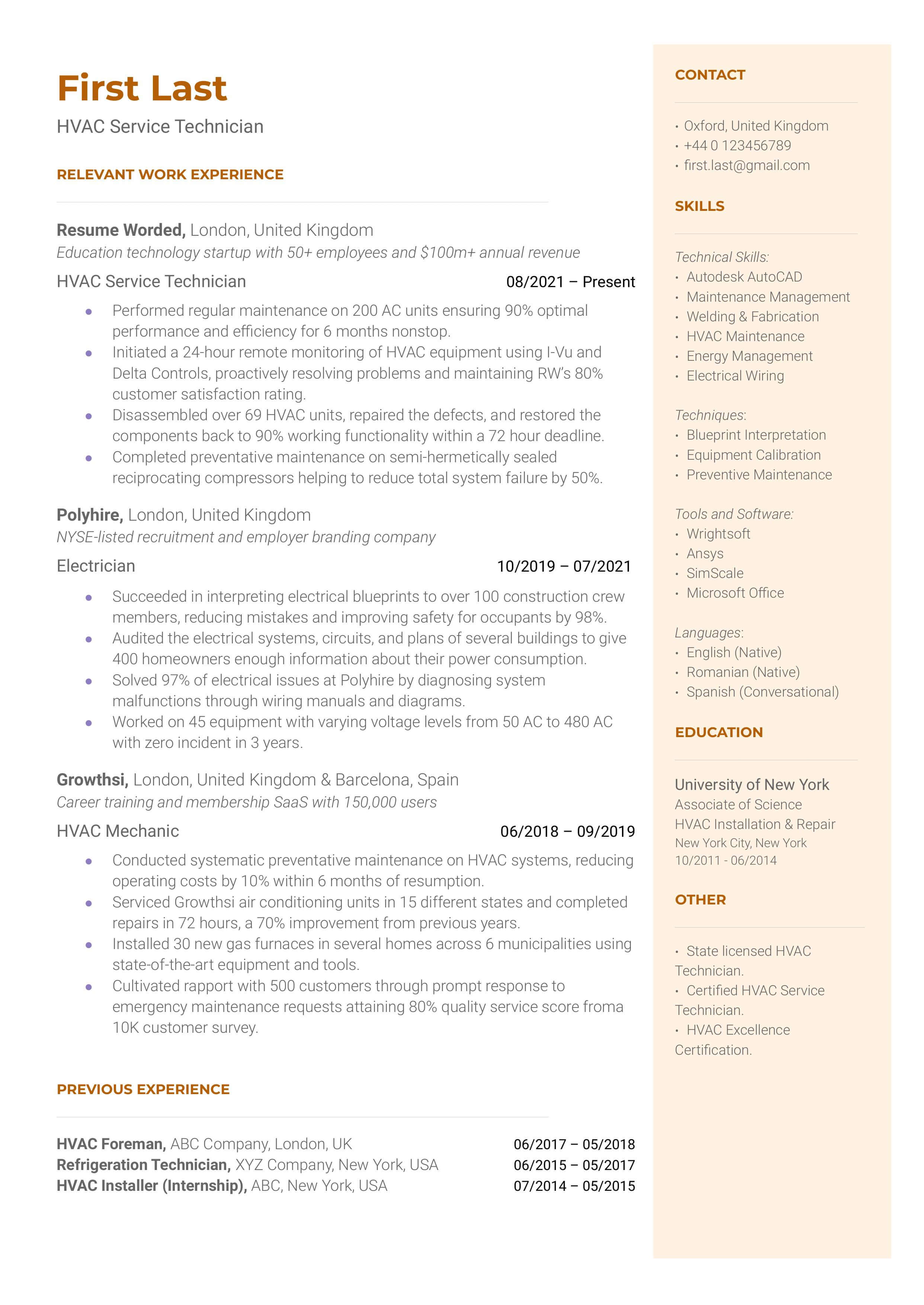

Customer Service Resume Templates

Cloud developer.

Relationship Manager

Service Technician

Administrative Resume Summary Examples

- > Administrative Assistant Summary Examples

- > Executive Assistant Summary Examples

- > Office Manager Summary Examples

- > Research Assistant Summary Examples

Administrative Resume Objective Examples

- > Administrative Assistant Objective Examples

- > Executive Assistant Objective Examples

- > Office Manager Objective Examples

- > Research Assistant Objective Examples

Administrative Resume Guides

- > Administrative Assistant Resume Guides

- > Executive Assistant Resume Guides

- > Office Manager Resume Guides

- > Research Assistant Resume Guides

Thank you for the checklist! I realized I was making so many mistakes on my resume that I've now fixed. I'm much more confident in my resume now.

Write a Killer Customer Service Resume Objective

Viktoriya maya, in this article, subscribe to our newsletter.

- First Name *

Write an Excellent Customer Service Resume Objective (Free Sample!)

To stand out in the highly competitive customer service industry you’ll need to know how to write a killer customer service resume objective. Crafting a top-notch objective statement is the best way to differentiate yourself and prevent your resume from being passed over by hiring managers. Luckily, this article is here to help you do just that.

Why You Should Include an Objective in Your Resume

The purpose of your objective statement may vary depending on where you are in your career. The general purpose is to provide a short description of your goals and what you can bring to a potential employer. This gives you an opportunity to show how your skills would be an asset in the position, even if you may not have direct experience in the industry. A good objective statement can make the difference between getting the job of your dreams or finding your resume lining the trash can of the HR department.

What Makes a Winning Objective?

The ideal objective statement should be concise, ideally only a sentence or two in length, and tailored to fit each job you apply for. It should quickly highlight who you are, what you offer, and your goals in a way that demonstrates value to potential employers.

A good objective should also reflect some level of understanding of the position and company you are applying to, for a customer service job this may include previous experience in the industry. If you don’t have experience it may also include relevant training you may have received or skills that could apply to the position. This small bit of customization will go a long way in showing hiring managers that you are a serious applicant and that you have done your research.

Writing a Professional C ustomer Service Resume Objective

Now that you know why you need a strong objective for your resume, you are probably wondering how to write one for yourself. Here are five simple tips that will help you get started:

#1. Know Your Goals

Customer service is a huge industry with a variety of roles available. When constructing your customer service resume objective, it’s important to have a clear direction in mind. For example, are you looking to work with customers face to face, in a call center , or in a virtual support type of role?

Knowing the specifics will allow you to further tailor your objective for the job you want. Narrowing your focus to only the most relevant skills, experience, and training will help your resume stand out.

#2. Demonstrate your value

It’s important to highlight your skills in the objective, but it’s more impactful if you also explain how you will use them to bring value to the company and carry out the required duties. Demonstrating how your skills are transferable to the new job can also help you show a deeper understanding of the position.

#3. Be concise

A good job will receive dozens, if not hundreds or even thousands of applicants. Competition means you will need to put in the work to make a positive first impression to stand out from other applicants. If your resume has a long objective, it’s not going to get read, and it might even get your resume pulled from consideration.

#4. Use the right keywords

In the interest of keeping your objective concise, you want to make sure every word counts, and that means using the right keywords. Every objective should include the name of the company you are applying to and the position as listed in the job posting. You can also look for keyword clues within the job posting, such as ideal qualifications, like experience working with specific software.

In a customer service resume objective, you may consider using keywords like communication, problem-solving, and conflict resolution .

#5. Adapt your Objective to Each Position and Company

It can’t be said enough. The single most important thing you can do when writing a resume objective is to write a new objective for every single job you apply for. If you want to stand out, customizing your objective is an effective way to do it. Each objective should highlight the skills and experience required for that job, and if possible, reflect the values of the company you are applying to.

Writing a Killer Customer Service Resume Objective: Dos and Don’ts

- Tailor the skills and qualifications you highlight for each job application.

- Include the company name and the title of the position you are filing for.

- Keep the objective short, no more than one or two sentences in length.

- Focus on how you can benefit the employer, not how they can benefit you.

- Avoid using vague statements that say little about your career goals (i.e. “looking for a job with opportunities for advancement”).

- Read and reread what you’ve written. Is it clear and concise? Does it make an impression?

- Reuse an objective statement to apply to multiple jobs.

- Omit the company name or leave out the title of the position you are applying for.

- Focus your objective on your wants and needs.

- Write a wordy unfocused objective statement.

Examples of High-Value Customer Service Resume Objectives

“Experienced customer service representative with 98.6% customer satisfaction rating over five years in a fast-paced call center role. Seeking the position of customer satisfaction manager with Smith Industries.”

“Hardworking hospitality graduate seeking the position of junior help desk associate at ICC Strategies.”

“Experienced human resources manager looking to use my extensive background in interpersonal relations and conflict resolution to add value to the customer relations team at J.R. and associates .”

Examples of a low-value customer service resume objective

“Customer service rep seeking employment with a large company with room to grow.”

“Recent graduate looking for work in a fast-paced team environment.”

“I am a friendly, hard-working, people person with five years of experience in customer support. Looking to secure a long-term employment opportunity with benefits in a team environment for a large company. I have experience working as a virtual assistant in call-centers and as a front desk manager at a major hotel chain for two years.”

Top Strategies For Writing A Customer Service Resume Objective

#1. create a long version.

The best way to construct an impactful and concise resume objective is to start by writing a longer version. Include everything you would like to communicate to the company and all of your relevant experience before paring it down to the bare essentials. It can be helpful to break down the information and rank it in order of importance for the specific position.

#2. Do Your Research

When you are trying to write an objective, it can be helpful to research the kind of work you are pursuing while looking out for recurring skills or other requirements. These recurring keywords will give you a good idea of what to focus on and which skills you should highlight in your objective.

#3. Get feedback

After you’ve written, read, and re-read your objective, it can be helpful to get an outside opinion before you submit your resume. A neutral party will have no attachment to what you’ve written and can offer unbiased feedback that can improve the quality of your objective.

5 Templates You Can Use to Craft Your Own Objectives

If you need a little more direction to get started writing resume objectives, check out the five templates below for inspiration:

- Dedicated customer service professional with [years of experience] looking to utilize my interpersonal and conflict resolution skills in the role of the position of [job title] at [company name].

- [Years of experience] working in the customer service industry in various roles. Looking to use my time management and communication skills to add value as a member of the support team at [company name].

- [Years of experience] working in a fast-paced call center setting where I maintained a 98.7% customer satisfaction rate. I’m looking to bring my problem solving, de-escalation, and communication skills to the help desk team at [company name].

- Experienced IT Professional looking to transition my problem-solving abilities, technical knowledge, and typing skills into a virtual support role with [company name].

- 2021 Communications graduate looking to apply my knowledge and experience in an entry-level help-desk position with [company name]. Feel free to use these templates, but remember to include the most relevant details for your position and skill set. Good luck job hunting!

Quick Summary

- A strong objective can improve your customer service resume and help you stand out.

- If you don’t have industry experience, a resume objective can help you transition careers.

- Resume objectives should be clear, concise, and tailored to each job you apply for.

- A good objective will focus on how your skills can benefit the employer.

- Your objective should always include specific details, like company name and job title.

Other Resources:

CustomersFirst Academy offers comprehensive customer service training designed to help you grow your skills and advance your career.

To keep learning and developing your knowledge of customer service, we highly recommend the additional resources below:

10 Transferable Retail Skills to Add to Your Resume How To Write A Successful Customer Service Cover Letter (Includes Free Sample) Top 10 Customer Service Rep Interview Questions Strategies to grow and keep your customer base

Share this post

Accelerate your success.

Career Resources

Communication skills, customer service.

- Empathy vs. Sympathy vs. Compassion: What’s the Difference?

- 10 Techniques To Enhance Your Client Relations Skills

- The Difference Between Verbal and Nonverbal Communication

- 10 Inspiring Quotes About Serving Others In Customer Service

- 7 Steps to Cultivating a Customer Service Culture

- Full Name *

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Keep Reading

Become a certified customer service professional today, certifications for customer service: boost your career, top customer service certifications: customersfirst academy, essential customer service training – philippines, customer service training for hvac technicians and teams, customer service elearning: the future of professional development, stand out with a customer service certification, exploring the customer service representative certification, it help desk training: what you need to know, help desk resume: essential skills for success, canadian universities for international students: top picks and tips, top universities in canada for international students: pros and cons, the best certificate program for working in customer service, jobs that help people and pay well: the best careers for you, 10 best customer service jobs for introverts, how to get a job in canada for new immigrants 2022, courses and certifications.

At CustomersFirst Academy, we empower professionals with customer service training programs and in-demand industry skills that are practical and easy to implement.

Privacy Overview

- CustomersFirst Academy Masterclass

- CustomersFirst De-Escalation Training

- Free Resource Library

- Preparation Tips

- Interview Checklist

- Questions&Answers

- Difficult Questions

- Questions to Ask

Interview Tips

- Dress for Success

- Job Interview Advice

- Behavioral Interview

- Entry Level Interview

- Information Interview

- Panel Interviews

- Group Interviews

- Phone Interviews

- Skype Interviews

- Second Interviews

- Zoom Interviews

- Job Interview Guides

- Administrative

- Call Center

- Clerical Interview

- Customer Service

- Human Resources

- Office Manager

- Project Manager

- Restaurant Jobs

- Social Work

- Interview Follow Up

- Thank You Letters

- Job References

- Employment Tests

- Background Checks

- Character References

- Accepting a Job Offer

- Decline a Job Offer

- Verbal Job Offer

- Negotiate Salary

- How to Resign

- Job Search Strategy

- Job Search Tips

- Respond to Interview Request

- Letters of Recommendation

- Surviving a Layoff

- Sample Resumes

- Resume Objectives

Cover Letters

Job Descriptions

- Job Interview Blog

- Best Articles

Privacy Policy

- Customer Service Resume Objective

Customer Service Resume Objective Examples

Customer service resume objective examples that highlight the skills and strengths you bring to the customer service job opportunity.

Your resume objective statement or summary should clearly and quickly articulate why the employer should take your job application seriously. It is the most important paragraph in your resume so take the time to get it right.

We know that a resume objective statement that answers the question "Why should I read this resume?" is far more effective than the single sentence that outlines your career objective.

These persuasive summaries of what you can bring to the job opportunity can easily be edited for your own resume. Your customer service resume objective or summary should be relevant and targeted to each different job opportunity.

Customer Service Resume Objective Examples - Paragraph Format

Dedicated customer service professional with 5 years experience in a fast-paced environment seeking an opportunity in a team-orientated company. Adept at handling a wide range of contact methods while accurately documenting customer issues and providing first class service with every interaction.

Track record of quickly acquiring competency in all products and transactions while readily and positively adapting to change.

Energetic customer service specialist eager to obtain a position that makes full use of expertise in building customer relations. Advanced customer service experience includes successfully implementing innovative customer programs that increased the customer base by X%.

A high level of computer knowledge and proven competency in multitasking enables optimal performance in a challenging environment .

Customer Service Resume Objective Examples - Bullet Format

Self-motivated and resourceful customer service representative with proven competency in:

- resolving a wide range of product and service issues speedily and satisfactorily

- exceeding customer's post-sales needs with energetic follow-up

- maintaining composure while handling challenging customer demands

- learning new processes from beginning to end

Focused customer service agent looking for a new challenge in a results-driven environment. Expertise includes:

- solid experience in defining and analyzing customer requests to resolve issues accurately and quickly with high first contact resolution rates.

- strong computer skills in a Windows-based environment and proven ability to learn unique software.

- confident and effective communicator who receives excellent customer feedback.

Customer Service Resume Objective Statement - Useful Phrases

These sample resume objective phrases articulate the skills, strengths and achievements employers are generally seeking in customer service staff.

Personalize these to build your own customer service resume objective statement that clearly addresses the needs of the position you are applying for.

Actively seeking a customer service position where I can optimize my problem-solving and organizational skills to contribute to increased customer satisfaction.

Strong multitasking skills and fast learning ability ensure quick contribution to your customer service team.

Able to effectively communicate with customers using a multitude of channels to provide world class service with every interaction.

Recognized for proactively maintaining an in-depth knowledge of all products and promotions.

Able to work successfully as a team member and as an individual contributor.

Exceptional communication skills with the ability to remain calm and convincing in negative situations.

Solid track record of analyzing product failure for problem identification and prioritization of necessary corrective actions.

Documented increase in customer retention by delivering a fully-integrated customer service solution.

Able to efficiently navigate multiple systems while handling complex queries.

Track record of providing high quality customer-focused service using in-depth knowledge of products and processes resulting in enhanced customer retention.

Highly resourceful customer service professional willing and able to adapt effectively to a constantly changing environment.

Experience in working collaboratively with other departments to facilitate the best user experience.

A creative problem-solver who is energized by dealing with a variety of challenges in a fast-paced environment.

In-depth computer knowledge and competency in a wide range of CRM software.

Able to swiftly and accurately collect relevant data to determine solutions to customer issues.

Proven ability to grasp and apply new concepts quickly and effectively in a results-driven environment.

How to Create a Customer Service Resume and Cover Letter

Use this customer service resume template to complete a job-winning resume.

Send a well written customer service cover letter .

Entry Level Customer Service Resume

Customer Service Manager Resume

Call Center Resume

Customer Service Keywords for Resumes

Using the right customer service resume keywords ensures that your resume gets past the Applicant Tracking System and gets noticed by employers.

Customer Service Resumes

CUSTOMER SERVICE

Customer Service Resume

Help Desk Resume Sample

Customer Service Cover Letters

Customer Service Cover Letter

Call Center Cover Letter

Sample Cover Letter Template

How do you Describe Customer Service Skills on a Resume?

Gain a good understanding of the customer role and the duties and skills required in this job.

Customer Service Job Description

Definition of Customer Service

Customer Service Job Interviews

Customer Service Interview Guide

Customer Service Interview Q&A

Behavioral Interview Questions

Call Center Interview

Help Desk Interview

To Top of Page

Don't Miss These Latest Updates

Problem-solving is a key skill for today's workplace. Problem-solving behavioral interview questions

Compelling sample interview answers to "Why do you want to work for this company?"

11 essential supervisor interview questions and answers plus industry specific supervisor Q&A .

How to ask for a letter of recommendation with this sample email requesting letter of recommendation .

What are the top 10 reasons for leaving your job? Find out acceptable reasons for leaving a job.

Sample employment acceptance letter and email to properly confirm your acceptance of the job offer and employment contract.

What are your strengths? Find out the 11 essential workplace strengths at list of strengths and weaknesses

Interview Preparation

Interview Questions & Answers

Interview Guides

After the Interview

The Job Offer

Latest News

© Copyright 2023 | Best-Job-Interview.com | All Rights Reserved.

30 Examples of Customer Service Resume Objective

By Status.net Editorial Team on March 6, 2024 — 9 minutes to read

Crafting a strong customer service resume objective is a vital step in landing your desired role. An effective objective succinctly highlights your relevant skills and passion for helping others, setting the tone for the rest of your resume. When you’re writing your resume objective, you want to focus on what you can bring to the employer, showing that you understand the importance of customer satisfaction and possess the necessary skills to excel in a service-oriented position.

Understanding Resume Objectives

When you’re crafting your resume, your objective statement is your opening pitch. It’s the first thing employers read, so you need to make it count. Think of it as a quick snapshot of who you are as a professional and what you offer to the company.

Your objective should be specific to the role you’re applying for. For example, if you’re aiming for a customer service position, an objective like, “Seeking a challenging customer service role where I can utilize my problem-solving skills and commitment to excellent customer experience” directly relates to the job.

Remember, your resume objective is different from a summary. It focuses on your goals for employment, rather than detailing your past work history. While your objective can mention a key strength or skill, ensure it aligns with the job description.

Here are some elements you might include in a customer service resume objective:

- Specific Position : You’re applying for a customer service position, so state it.

- Skills : Highlight customer-oriented skills like communication, problem-solving, or conflict resolution.

- Experience : Mention relevant experience only if it strengthens your objective.

- Career Goals: Include how the position fits your career plans without overshadowing the company’s needs.

Examples of Effective Resume Objectives

When crafting your resume objective, you’re setting the stage for your professional narrative. It’s important to tailor this short statement to reflect your skills and goals, grabbing the employer’s attention right from the start.

Entry-Level Objectives

If you’re starting your career, your resume objective should highlight your enthusiasm and dedication to learning and contributing to the company. For example:

- “Eager to bring fresh and innovative ideas to a dynamic team at [Company Name] as a Junior Developer, leveraging recent training in full-stack development and a commitment to building user-friendly applications.”

- “Aspiring Customer Service Specialist with a strong academic background in Communication Studies, aiming to leverage my problem-solving skills and passion for helping others to enhance client relationships at [Company Name].”

Experienced Professional Objectives

As an experienced professional, your resume objective can reflect your expertise and how you can add value to the employer’s organization with your seasoned skills. Consider these examples:

- “Seasoned Marketing Manager interested in bringing over 10 years of experience in campaign development and team leadership to [Company Name], driving impactful brand strategies and boosting market presence.”

- “Dedicated Nurse Practitioner with a decade of experience in patient care, committed to offering compassionate and evidence-based treatment to patients at [Healthcare Center or Hospital], with a focus on preventive care and patient education.”

Your resume objective is your chance to make a great first impression. You’ll want to be precise, align with what the employer is looking for, and showcase the best of your abilities and experience right at the top of your resume.

Tailoring to the Job Description

To engage the hiring manager quickly, you can mirror language from the job description in your resume objective. This shows you’ve read and understood the job posting, and your skills match their needs.

- Experienced customer service representative seeking to leverage strong communication skills and a track record of maintaining customer satisfaction from the job description in a fast-paced retail environment.

- Looking for a customer service role where I can apply my experience handling complex queries detailed in the job description to improve customer engagement for the company.

- Eager to bring my detailed-oriented nature and exemplary problem-solving abilities mentioned in the job listing to a dynamic customer service team.

- To join a tech-savvy support team, as described in the job posting, where I can contribute my extensive knowledge of software products to enhance user experience.

- Aiming to utilize my proven patience and communication skills, as required by the role, to provide exceptional service at [Company Name].

- Intent on using my multilingual skills and hospitality background from the job description to enhance customer satisfaction at [Company Name].

- Pursuing a customer service position with [Company Name] where my commitment to addressing customer needs as described can drive loyalty and growth.

- Seeking to apply my strong organization skills and attention to detail, as the job demands, within a customer support role at a fast-growing tech company.

- Dedicated to bringing my conflict resolution abilities and positive attitude, which are highlighted in the job advertisement, to a rewarding customer service position.

- Motivated to join [Company Name] where my track record of increasing customer retention, as laid out in the job needs, can be put to excellent use.

Highlighting Your Skills

In customer service, certain skills make you stand out. Here’s a list of phrases you can use, each featuring a different key skill:

- Bringing to the table exceptional interpersonal skills and a commitment to customer satisfaction.

- Offering adept problem-solving abilities to handle even the most challenging customer inquiries.

- Proven expertise in using CRM software to streamline customer interactions and maintain organized records.

- Seasoned in providing support via phone, email, and live chat, ensuring comprehensive assistance across all channels.

- Adept at multitasking in fast-paced environments to meet and exceed customer service goals.

- Keen ability to quickly adapt to new products and technologies to provide informed customer support.

- Strong work ethic and a team player attitude to positively contribute to a cohesive customer service unit.

- Capable of fostering positive customer relations, building loyalty, and increasing customer engagement.

- Committed to maintaining customer confidentiality and ensuring secure handling of sensitive information.

- Proficient in conflict resolution, ready to diffuse tense situations and promote a calm service environment.

Showcasing Experience

Your experience can be a testament to your abilities.

- Bringing three years of high-volume call center experience to the customer service role at [Company Name].

- Offering extensive experience in face-to-face customer service within the retail sector, aiming to bring that expertise to [Company Name].

- Ready to apply five years of experience in the hospitality industry to improve customer satisfaction rates at [Company Name].

- Transitioning seven years of freelance customer support experience to a dedicated full-time role with your team.

- Applying a decade of management experience in customer service departments to lead and inspire your team.

- Ready to transfer a diverse background of customer support in tech, retail, and telecommunications to your company.

- Leveraging my track record of improving first contact resolution rates in previous customer service roles.

- Looking to utilize four years of experience in a supervisory customer service position to foster team excellence at [Company Name].

- With a history of successfully managing customer service for a startup, I’m ready to bring that growth mindset to your company.

- Aim to enhance customer service strategies with over eight years’ experience leading successful teams.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

When crafting your customer service resume objective, you might be tempted to emphasize your desire to get a job, but you should instead focus on how you can meet the needs of the employer. For example, avoid statements like “ I want to improve my skills at a reputable company ” and instead try “ Dedicated customer service professional aiming to contribute to (…) Company’s customer satisfaction goals with proven communication skills. ”

- Steer clear of vague phrases. For instance, rather than saying “ I am a hard worker, ” use specific examples to demonstrate your work ethic, like “ Consistently met customer service satisfaction scores above 95%. “

- Keep your objective statement short and avoid lengthy paragraphs. A good rule of thumb is to keep it under two to three sentences. Your goal is to quickly show your potential value to the hiring manager, not to provide your entire work history.

- Resist the temptation to use overly technical jargon or acronyms unless you are certain they are common in your field. If you’re applying for a role in a specific industry where certain terms are well-known, it’s fine to use them, but in general, plain language is more accessible.

- Proofread your resume objective to avoid typos and grammatical errors, which can make you seem careless. Also, failure to customize your objective for each role could convey a lack of genuine interest in the position. Tailoring your statement to the job and company shows that you’ve done your research and understand what they’re looking for.

Tips for Polishing Your Objective

- Try to tailor your objective for each job application. Highlight particular strengths that match the job description. If the job emphasizes teamwork, mention your collaborative skills.

- Use action words to convey energy and enthusiasm. Words like “achieve,” “deliver,” and “enhance” can be powerful starters. Related: Writing a Summary of Qualifications: Examples & Action Words

- Keep your customer at the forefront. After all, your role is about service. Phrase your objective to reflect that your priority is their satisfaction. You might say, “Aiming to deliver exceptional customer service and support by efficiently addressing customer needs and feedback.”

- Show off your industry knowledge with specific terms. Mention if you’re familiar with any CRM software, chat platforms, or other customer service tools.

Your resume objective should be tailored to reflect your unique strengths and the specific job you are applying for. It’s important to use keywords from the job description and to be clear about what you aim to achieve in the position.

Frequently Asked Questions

What can i put as an objective on my resume if i’m new to customer service.

For your first foray into customer service, focus on your eagerness to learn and contribute. For example, you might write “Enthusiastic and personable individual seeking a Customer Service Representative position to leverage my strong communication skills and commitment to providing excellent customer support.”

How should I craft a resume objective for a customer service position with no prior experience?

Highlight your transferable skills, such as problem-solving and active listening, which are vital in customer service. Example: “Seeking a role as a Customer Support Specialist where I can apply my adeptness at resolving conflicts and my ability to work well under pressure.”

What are some good objectives to include on a resume for a customer service role at a call center?

When applying for a call center role, showcase your ability to handle high call volumes gracefully. An example objective could be “To obtain a position as a Call Center Representative where I can employ my proficiency in customer care and my excellent verbal communication skills.”

How do I write a compelling customer service resume summary for a retail position?

Your summary should reflect your understanding of retail service excellence. An example might be “Customer Service enthusiast with a passion for fostering long-lasting client relationships and a proven track record in a fast-paced retail environment looking to bring dedication and an outstanding work ethic to XYZ Retail.”

Can you provide examples of effective resume objectives for fresh graduates applying for customer service jobs?

Fresh graduates should highlight their academic achievements and relevant skills. Example “Recent graduate with a Bachelor’s in Communication eager to contribute to (…) Company’s customer service team with strong interpersonal skills and a commitment to improving customer satisfaction.”

What should I include in a customer service resume objective if I have extensive experience?

For those with significant experience, it’s important to bring attention to your track record and leadership qualities. An objective like “Seasoned customer service professional with over 10 years of experience in resolving complex customer inquiries seeking a managerial role to drive customer loyalty and team efficiency at ABC Corp.” would be appropriate.

- 3 Examples: How to Write a Customer Service Resume Summary

- 40 Customer Service Self Evaluation Examples

- How to Deliver Excellent Customer Service (with Examples)

- 2 Examples of Customer Service Representative Cover Letters

- Customer Service Skills: Performance Review Examples (Rating 1 - 5)

- Empathy in Customer Service (50 Example Phrases)

Top 25 Customer Service Resume Objective Examples

This post provides a guide on how to make a compelling customer service resume objective statement, as well as great examples, to help boost the effectiveness of your resume and increase your chances of being hired for the customer service position that you are seeking.

Before your resume or CV can convince the recruiter that you are the best candidate for the customer service job, it must begin with a superior objective statement.

It is essential to have the employer get into your customer service resume and read it to the end, and not just a part of it.

This will make your offer clear before the recruiter and increase your chances of being invited for interview.

With what you learn from this post, you can make an effective career objective statement for your resume and make your chances for recruitment for the customer service role brighter.

How to Make a Great Customer Service Resume Objective Statement

To make an eye-catching resume objective for a customer service position, you need to know what exactly the recruiter wants.

Once you are able to give the recruiter exactly what they want their right candidate for the customer service position to have, they will be interested in your resume and want to read it to the end.

The recruiter or employer normally has a set of specific standards and requirements that applicants should meet to qualify to access the available customer service position.

So, in writing a great customer service resume objective, you need to focus on offering the recruiter exactly what they have specified in the job requirements.