How To Write A Thesis Introduction Chapter

Crafting the introductory chapter of a thesis can be confusing. If you are feeling the same, you are the at right place.

This post will explore how you can write a thesis introduction chapter, by outlining the essential components of a thesis introduction. We will look at the process, one section at a time, and explain them to help you get a hang of how to craft your thesis introduction.

How To Write A Good Thesis Introduction?

The opening section of a thesis introduction sets the stage for what’s to come, acting as a crucial hook to capture the reader’s attention.

Unlike the broader strokes found in the table of contents, this initial foray into your research is where you must distill the essence of your thesis into a potent, digestible form.

A skillful introduction begins with a concise preview of the chapter’s terrain, delineating the structure of the thesis with a clarity that avoids overwhelming the reader.

This is not the stage for exhaustive details; rather, it’s where you prime the reader with a snapshot of the intellectual journey ahead.

In crafting this segment, insiders advise adhering to a quartet of foundational sentences that offer an academic handshake to the reader.

First Section: I ntroduces the broad field of research, such as the significance of organisational skills development in business growth.

Second Section: Narrows the focus, pinpointing a specific research problem or gap — perhaps the debate on managing skill development in fast-paced industries like web development.

Third Section: Clearly state the research aims and objectives, guiding the reader to the ‘why’ behind your study. Finally, a sentence should outline the roadmap of the introduction chapter itself, forecasting the background context, research questions, significance, and limitations that will follow.

Such a calibrated approach ensures that every element from the research objective to the hypothesis is presented with precision.

This method, a well-guarded secret amongst seasoned researchers, transforms a mundane introduction into a compelling entrée into your dissertation or thesis.

Background To The Study

This section sets the tone for the research journey ahead. The goal here is to capture the reader’s attention by threading relevant background information into a coherent narrative that aligns with the research objectives of the thesis.

To write a good thesis introduction, one must carefully describe the background to highlight the context in which the research is grounded.

This involves not just a literature review but a strategic presentation of the current state of research, pinpointing where your work will wedge itself into the existing body of knowledge.

For instance, if the research project focuses on qualitative changes in urban planning, the introduction should spotlight key developmental milestones and policy shifts that foreground the study’s aims and objectives.

When writing this section, articulate the focus and scope of the research, ensuring the reader grasps the importance of the research questions and hypothesis.

This section must not only be informative but also engaging. By the end of the introductory chapter, the reader should be compelled to continue reading, having grasped a clear and easy-to-understand summary of each chapter that will follow.

It’s a good idea to address frequently asked questions and to clearly state any industry-specific terminology, assuming no prior expertise on the reader’s part.

This approach establishes a solid foundation for the rest of the thesis or dissertation, ensuring the reader is well-prepared to dive into the nuances of your research project.

Research Problem

Crafting the nucleus of your thesis or dissertation hinges on pinpointing a compelling research problem. This step is crucial; it is the keystone of a good thesis introduction chapter, drawing the reader’s attention and setting the stage for the rest of your thesis.

A well-defined research problem addresses a gap in the existing literature, underscored by a qualitative or quantitative body of research that lacks consensus or is outdated, especially in rapidly evolving fields.

Consider the dynamic sphere of organizational skills development. Established research might agree on strategies for industries where skills change at a snail’s pace.

However, if the landscape shifts more quickly—take web development for example, where new languages and platforms emerge incessantly—the literature gap becomes evident.

Herein lies the research problem: existing strategies may not suffice in industries characterized by a swift knowledge turnover.

When writing your introduction, your goal is to clearly state this gap. A great thesis introduction delineates what is known, what remains unknown, and why bridging this chasm is significant.

It should illuminate the research objectives and questions, laying out a roadmap for the reader in a language that’s clear and easy to understand, regardless of their familiarity with the topic.

You’ll be able to capture and maintain the reader’s interest by effectively communicating why your research matters—setting the scene for your hypothesis and subsequent investigation.

Remember, a good thesis introduction should not only provide background information but also articulate the focus and scope of the study, offering a preview of the structure of your thesis.

Research Aims, Objectives And Questions

This pivotal section lays out the foundation by providing relevant background information, but it is the articulation of research aims, objectives, and questions that clarifies the focus and scope of your study.

The research aim is the lighthouse of your thesis, illuminating the overarching purpose of your investigation.

For instance, a thesis exploring skills development in fast-paced industries might present an aim to evaluate the effectiveness of various strategies within UK web development companies. This broad goal sets the direction for more detailed planning.

Research objectives drill down into specifics, acting as stepping stones toward achieving your aim. They are the tangible checkpoints of your research project, often action-oriented, outlining what you will do.

Examples might include identifying common skills development strategies or evaluating their effectiveness. These objectives segment the monumental task into manageable portions, offering a clear and easy way to write a structured pathway for the research.

Equally critical are the research questions, which translate your objectives into inquiries that your thesis will answer. They narrow the focus even further, dictating the structure of the thesis.

For instance:

- “What are the prevalent skills development strategies employed by UK web development firms?”

- “How effective are these strategies?”

Such questions demand concrete responses and guide the reader through the rest of the thesis.

Significance Of The Study

The “Significance of the Study” section within the introduction chapter of your thesis or dissertation holds considerable weight in laying out the importance of your research.

This segment answers the pivotal question: “Why does this research matter?” It is strategically placed after the background information and literature review to underscore the contribution your study makes to the existing body of research.

In writing this section, you’ll be able to capture the reader’s attention by clearly stating the impact and added value your research project offers.

Whether it’s a qualitative or quantitative study, the significance must be articulated in terms of:

- Theoretical

- Academic, and

- Societal contributions.

For instance, it may fill gaps identified in the literature review, propose innovative solutions to pressing problems, or advance our understanding in a certain field.

A good thesis introduction will succinctly convey three main things: the research objective, the hypothesis or research questions, and the importance of your research.

It’s a good idea to provide your reader with a roadmap, foreshadowing the structure of the thesis and offering a summary of each chapter, thus enticing the reader to continue reading.

When you write the introduction section, it should also serve as a concise synopsis of the focus and scope of your research.

It’s often beneficial to include examples of introductions that clearly state the research objectives and questions, offering a snapshot of the whole thesis, and setting the stage for the rest of your thesis.

Limitations Of The Study

A thorough thesis introduction lays out specific research objectives and questions, yet it also sheds light on the study’s inherent boundaries. This is the purpose of the Limitation of The Study section.

The limitations section is not a confession of failure; instead, it’s a good idea to see it as demonstrating academic maturity.

Here, you clearly state the parameters within which the research was conducted.

For instance, a qualitative study might face scrutiny for subjectivity, or a quantitative one for potentially oversimplifying complexities. Other common constraints include the scope—perhaps focusing on a narrow aspect without considering variable interplay—resources, and generalizability.

For example, a study concentrated on a specific industry in Florida may not hold water in a different context, for example in Tokyo, Japan.

It’s essential to write this section with transparency. A good thesis introduction doesn’t shy away from limitations. Instead, it captures the reader’s attention by laying them out systematically, often in a dedicated paragraph for each chapter.

This honesty allows the reader to understand the research’s focus and scope while providing a clear and easy-to-follow structure of the thesis.

This approach also serves to manage the reader’s expectations. By preempting frequently asked questions about the scope of your research, the introductory chapter establishes a trust that encourages the reader to continue reading, aware of the contours shaping the body of research.

Thus, a well-articulated limitations section is not just part of the thesis; it is an integral piece of a responsibly woven research narrative.

Structural Outline Of Thesis, Thesis Statement

Within the thesis or dissertation, the structural outline section is akin to a compass, orienting the reader’s journey through the academic landscape laid out within the pages.

Crafting this section is a strategic exercise, one that requires an understanding of the work’s skeleton.

In essence, it’s the blueprint for the construction of a scholarly argument, and writing a good thesis necessitates a clear and easy-to-follow outline.

When you write a thesis outline, it’s not only about catching the reader’s attention; it’s also about holding it throughout the rest of the thesis.

This is where the structural outline comes into play, often beginning with an introduction chapter that presents the thesis statement, research objectives, and the importance of your research.

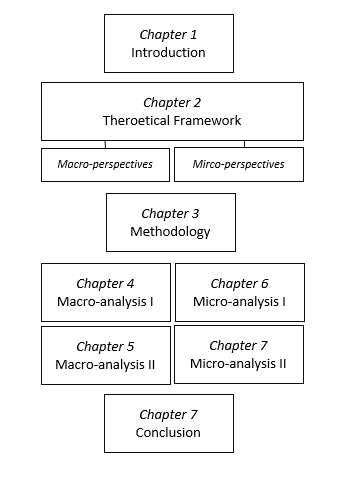

Following the introduction, a typical outline might proceed with Chapter 2, offering a literature review to acquaint the reader with existing literature and how this piece of research fits within it.

Subsequent chapters, each with a paragraph in the outline, detail the methodological approach—whether it’s qualitative or quantitative—and the research’s focus and scope.

A well-thought-out outline should also preview the structure of the thesis, succinctly:

- Summarizing the main aim and objectives of each chapter, and

- Indicating the type of data and analysis that will be presented.

This roadmap reassures the reader that the dissertation or thesis will cover the necessary ground in a logical progression, continuing from where the introduction first captivated their interest.

The structural outline is not only part of the thesis—it’s a strategic framework that informs the reader what to expect in each subsequent chapter.

Done correctly, this section allows the reader to understand the whole thesis in a nutshell and can often serve as a checklist for both the reader and the writer.

This ensures that the key stages of the research project are clearly stated and that the reader is provided with a roadmap to guide them through the detailed landscape of your scholarly work.

Write An Introduction Chapter With Ease

Mastering the thesis introduction chapter is a critical step towards a successful dissertation. It’s about striking a balance between engagement and information, presenting a snapshot of your research with clarity and intrigue.

Remember to start with a hook, establish the context, clarify your aims, and highlight the significance, all while being mindful of the study’s scope and limitations.

By adhering to these principles, your introduction will not only guide but also inspire your readers, laying a strong foundation for the in-depth exploration that follows in your thesis or dissertation.

Dr Andrew Stapleton has a Masters and PhD in Chemistry from the UK and Australia. He has many years of research experience and has worked as a Postdoctoral Fellow and Associate at a number of Universities. Although having secured funding for his own research, he left academia to help others with his YouTube channel all about the inner workings of academia and how to make it work for you.

Thank you for visiting Academia Insider.

We are here to help you navigate Academia as painlessly as possible. We are supported by our readers and by visiting you are helping us earn a small amount through ads and affiliate revenue - Thank you!

2024 © Academia Insider

How to write a fantastic thesis introduction (+15 examples)

The thesis introduction, usually chapter 1, is one of the most important chapters of a thesis. It sets the scene. It previews key arguments and findings. And it helps the reader to understand the structure of the thesis. In short, a lot is riding on this first chapter. With the following tips, you can write a powerful thesis introduction.

Disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase using the links below at no additional cost to you . I only recommend products or services that I truly believe can benefit my audience. As always, my opinions are my own.

Elements of a fantastic thesis introduction

Open with a (personal) story, begin with a problem, define a clear research gap, describe the scientific relevance of the thesis, describe the societal relevance of the thesis, write down the thesis’ core claim in 1-2 sentences, support your argument with sufficient evidence, consider possible objections, address the empirical research context, give a taste of the thesis’ empirical analysis, hint at the practical implications of the research, provide a reading guide, briefly summarise all chapters to come, design a figure illustrating the thesis structure.

An introductory chapter plays an integral part in every thesis. The first chapter has to include quite a lot of information to contextualise the research. At the same time, a good thesis introduction is not too long, but clear and to the point.

A powerful thesis introduction does the following:

- It captures the reader’s attention.

- It presents a clear research gap and emphasises the thesis’ relevance.

- It provides a compelling argument.

- It previews the research findings.

- It explains the structure of the thesis.

In addition, a powerful thesis introduction is well-written, logically structured, and free of grammar and spelling errors. Reputable thesis editors can elevate the quality of your introduction to the next level. If you are in search of a trustworthy thesis or dissertation editor who upholds high-quality standards and offers efficient turnaround times, I recommend the professional thesis and dissertation editing service provided by Editage .

This list can feel quite overwhelming. However, with some easy tips and tricks, you can accomplish all these goals in your thesis introduction. (And if you struggle with finding the right wording, have a look at academic key phrases for introductions .)

Ways to capture the reader’s attention

A powerful thesis introduction should spark the reader’s interest on the first pages. A reader should be enticed to continue reading! There are three common ways to capture the reader’s attention.

An established way to capture the reader’s attention in a thesis introduction is by starting with a story. Regardless of how abstract and ‘scientific’ the actual thesis content is, it can be useful to ease the reader into the topic with a short story.

This story can be, for instance, based on one of your study participants. It can also be a very personal account of one of your own experiences, which drew you to study the thesis topic in the first place.

Start by providing data or statistics

Data and statistics are another established way to immediately draw in your reader. Especially surprising or shocking numbers can highlight the importance of a thesis topic in the first few sentences!

So if your thesis topic lends itself to being kick-started with data or statistics, you are in for a quick and easy way to write a memorable thesis introduction.

The third established way to capture the reader’s attention is by starting with the problem that underlies your thesis. It is advisable to keep the problem simple. A few sentences at the start of the chapter should suffice.

Usually, at a later stage in the introductory chapter, it is common to go more in-depth, describing the research problem (and its scientific and societal relevance) in more detail.

You may also like: Minimalist writing for a better thesis

Emphasising the thesis’ relevance

A good thesis is a relevant thesis. No one wants to read about a concept that has already been explored hundreds of times, or that no one cares about.

Of course, a thesis heavily relies on the work of other scholars. However, each thesis is – and should be – unique. If you want to write a fantastic thesis introduction, your job is to point out this uniqueness!

In academic research, a research gap signifies a research area or research question that has not been explored yet, that has been insufficiently explored, or whose insights and findings are outdated.

Every thesis needs a crystal-clear research gap. Spell it out instead of letting your reader figure out why your thesis is relevant.

* This example has been taken from an actual academic paper on toxic behaviour in online games: Liu, J. and Agur, C. (2022). “After All, They Don’t Know Me” Exploring the Psychological Mechanisms of Toxic Behavior in Online Games. Games and Culture 1–24, DOI: 10.1177/15554120221115397

The scientific relevance of a thesis highlights the importance of your work in terms of advancing theoretical insights on a topic. You can think of this part as your contribution to the (international) academic literature.

Scientific relevance comes in different forms. For instance, you can critically assess a prominent theory explaining a specific phenomenon. Maybe something is missing? Or you can develop a novel framework that combines different frameworks used by other scholars. Or you can draw attention to the context-specific nature of a phenomenon that is discussed in the international literature.

The societal relevance of a thesis highlights the importance of your research in more practical terms. You can think of this part as your contribution beyond theoretical insights and academic publications.

Why are your insights useful? Who can benefit from your insights? How can your insights improve existing practices?

Formulating a compelling argument

Arguments are sets of reasons supporting an idea, which – in academia – often integrate theoretical and empirical insights. Think of an argument as an umbrella statement, or core claim. It should be no longer than one or two sentences.

Including an argument in the introduction of your thesis may seem counterintuitive. After all, the reader will be introduced to your core claim before reading all the chapters of your thesis that led you to this claim in the first place.

But rest assured: A clear argument at the start of your thesis introduction is a sign of a good thesis. It works like a movie teaser to generate interest. And it helps the reader to follow your subsequent line of argumentation.

The core claim of your thesis should be accompanied by sufficient evidence. This does not mean that you have to write 10 pages about your results at this point.

However, you do need to show the reader that your claim is credible and legitimate because of the work you have done.

A good argument already anticipates possible objections. Not everyone will agree with your core claim. Therefore, it is smart to think ahead. What criticism can you expect?

Think about reasons or opposing positions that people can come up with to disagree with your claim. Then, try to address them head-on.

Providing a captivating preview of findings

Similar to presenting a compelling argument, a fantastic thesis introduction also previews some of the findings. When reading an introduction, the reader wants to learn a bit more about the research context. Furthermore, a reader should get a taste of the type of analysis that will be conducted. And lastly, a hint at the practical implications of the findings encourages the reader to read until the end.

If you focus on a specific empirical context, make sure to provide some information about it. The empirical context could be, for instance, a country, an island, a school or city. Make sure the reader understands why you chose this context for your research, and why it fits to your research objective.

If you did all your research in a lab, this section is obviously irrelevant. However, in that case you should explain the setup of your experiment, etcetera.

The empirical part of your thesis centers around the collection and analysis of information. What information, and what evidence, did you generate? And what are some of the key findings?

For instance, you can provide a short summary of the different research methods that you used to collect data. Followed by a short overview of how you analysed this data, and some of the key findings. The reader needs to understand why your empirical analysis is worth reading.

You already highlighted the practical relevance of your thesis in the introductory chapter. However, you should also provide a preview of some of the practical implications that you will develop in your thesis based on your findings.

Presenting a crystal clear thesis structure

A fantastic thesis introduction helps the reader to understand the structure and logic of your whole thesis. This is probably the easiest part to write in a thesis introduction. However, this part can be best written at the very end, once everything else is ready.

A reading guide is an essential part in a thesis introduction! Usually, the reading guide can be found toward the end of the introductory chapter.

The reading guide basically tells the reader what to expect in the chapters to come.

In a longer thesis, such as a PhD thesis, it can be smart to provide a summary of each chapter to come. Think of a paragraph for each chapter, almost in the form of an abstract.

For shorter theses, which also have a shorter introduction, this step is not necessary.

Especially for longer theses, it tends to be a good idea to design a simple figure that illustrates the structure of your thesis. It helps the reader to better grasp the logic of your thesis.

Master Academia

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox.

Subscribe and receive Master Academia's quarterly newsletter.

The most useful academic social networking sites for PhD students

10 reasons not to do a master's degree, related articles.

How to prepare your viva opening speech

Minimalist writing for a better thesis

Dealing with conflicting feedback from different supervisors

Better thesis writing with the Pomodoro® technique

How to Write an Impressive Thesis Results Section

After collecting and analyzing your research data, it’s time to write the results section. This article explains how to write and organize the thesis results section, the differences in reporting qualitative and quantitative data, the differences in the thesis results section across different fields, and the best practices for tables and figures.

What is the thesis results section?

The thesis results section factually and concisely describes what was observed and measured during the study but does not interpret the findings. It presents the findings in a logical order.

What should the thesis results section include?

- Include all relevant results as text, tables, or figures

- Report the results of subject recruitment and data collection

- For qualitative research, present the data from all statistical analyses, whether or not the results are significant

- For quantitative research, present the data by coding or categorizing themes and topics

- Present all secondary findings (e.g., subgroup analyses)

- Include all results, even if they do not fit in with your assumptions or support your hypothesis

What should the thesis results section not include?

- If the study involves the thematic analysis of an interview, don’t include complete transcripts of all interviews. Instead, add these as appendices

- Don’t present raw data. These may be included in appendices

- Don’t include background information (this should be in the introduction section )

- Don’t speculate on the meaning of results that do not support your hypothesis. This will be addressed later in the discussion and conclusion sections.

- Don’t repeat results that have been presented in tables and figures. Only highlight the pertinent points or elaborate on specific aspects

How should the thesis results section be organized?

The opening paragraph of the thesis results section should briefly restate the thesis question. Then, present the results objectively as text, figures, or tables.

Quantitative research presents the results from experiments and statistical tests , usually in the form of tables and figures (graphs, diagrams, and images), with any pertinent findings emphasized in the text. The results are structured around the thesis question. Demographic data are usually presented first in this section.

For each statistical test used, the following information must be mentioned:

- The type of analysis used (e.g., Mann–Whitney U test or multiple regression analysis)

- A concise summary of each result, including descriptive statistics (e.g., means, medians, and modes) and inferential statistics (e.g., correlation, regression, and p values) and whether the results are significant

- Any trends or differences identified through comparisons

- How the findings relate to your research and if they support or contradict your hypothesis

Qualitative research presents results around key themes or topics identified from your data analysis and explains how these themes evolved. The data are usually presented as text because it is hard to present the findings as figures.

For each theme presented, describe:

- General trends or patterns observed

- Significant or representative responses

- Relevant quotations from your study subjects

Relevant characteristics about your study subjects

Differences among the results section in different fields of research

Nevertheless, results should be presented logically across all disciplines and reflect the thesis question and any hypotheses that were tested.

The presentation of results varies considerably across disciplines. For example, a thesis documenting how a particular population interprets a specific event and a thesis investigating customer service may both have collected data using interviews and analyzed it using similar methods. Still, the presentation of the results will vastly differ because they are answering different thesis questions. A science thesis may have used experiments to generate data, and these would be presented differently again, probably involving statistics. Nevertheless, results should be presented logically across all disciplines and reflect the thesis question and any hypotheses that were tested.

Differences between reporting thesis results in the Sciences and the Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS) domains

In the Sciences domain (qualitative and experimental research), the results and discussion sections are considered separate entities, and the results from experiments and statistical tests are presented. In the HSS domain (qualitative research), the results and discussion sections may be combined.

There are two approaches to presenting results in the HSS field:

- If you want to highlight important findings, first present a synopsis of the results and then explain the key findings.

- If you have multiple results of equal significance, present one result and explain it. Then present another result and explain that, and so on. Conclude with an overall synopsis.

Best practices for using tables and figures

The use of figures and tables is highly encouraged because they provide a standalone overview of the research findings that are much easier to understand than wading through dry text mentioning one result after another. The text in the results section should not repeat the information presented in figures and tables. Instead, it should focus on the pertinent findings or elaborate on specific points.

Some popular software programs that can be used for the analysis and presentation of statistical data include Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS ) , R software , MATLAB , Microsoft Excel, Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) , GraphPad Prism , and Minitab .

The easiest way to construct tables is to use the Table function in Microsoft Word . Microsoft Excel can also be used; however, Word is the easier option.

General guidelines for figures and tables

- Figures and tables must be interpretable independent from the text

- Number tables and figures consecutively (in separate lists) in the order in which they are mentioned in the text

- All tables and figures must be cited in the text

- Provide clear, descriptive titles for all figures and tables

- Include a legend to concisely describe what is presented in the figure or table

Figure guidelines

- Label figures so that the reader can easily understand what is being shown

- Use a consistent font type and font size for all labels in figure panels

- All abbreviations used in the figure artwork should be defined in the figure legend

Table guidelines

- All table columns should have a heading abbreviation used in tables should be defined in the table footnotes

- All numbers and text presented in tables must correlate with the data presented in the manuscript body

Quantitative results example : Figure 3 presents the characteristics of unemployed subjects and their rate of criminal convictions. A statistically significant association was observed between unemployed people <20 years old, the male sex, and no household income.

Qualitative results example: Table 5 shows the themes identified during the face-to-face interviews about the application that we developed to anonymously report corruption in the workplace. There was positive feedback on the app layout and ease of use. Concerns that emerged from the interviews included breaches of confidentiality and the inability to report incidents because of unstable cellphone network coverage.

Table 5. Themes and selected quotes from the evaluation of our app designed to anonymously report workplace corruption.

Tips for writing the thesis results section

- Do not state that a difference was present between the two groups unless this can be supported by a significant p-value .

- Present the findings only . Do not comment or speculate on their interpretation.

- Every result included must have a corresponding method in the methods section. Conversely, all methods must have associated results presented in the results section.

- Do not explain commonly used methods. Instead, cite a reference.

- Be consistent with the units of measurement used in your thesis study. If you start with kg, then use the same unit all throughout your thesis. Also, be consistent with the capitalization of units of measurement. For example, use either “ml” or “mL” for milliliters, but not both.

- Never manipulate measurement outcomes, even if the result is unexpected. Remain objective.

Results vs. discussion vs. conclusion

Results are presented in three sections of your thesis: the results, discussion, and conclusion.

- In the results section, the data are presented simply and objectively. No speculation or interpretation is given.

- In the discussion section, the meaning of the results is interpreted and put into context (e.g., compared with other findings in the literature ), and its importance is assigned.

- In the conclusion section, the results and the main conclusions are summarized.

A thesis is the most crucial document that you will write during your academic studies. For professional thesis editing and thesis proofreading services , visit Enago Thesis Editing for more information.

Editor’s pick

Get free updates.

Subscribe to our newsletter for regular insights from the research and publishing industry!

Review Checklist

Have you completed all data collection procedures and analyzed all results ?

Have you included all results relevant to your thesis question, even if they do not support your hypothesis?

Have you reported the results objectively , with no interpretation or speculation?

For quantitative research, have you included both descriptive and inferential statistical results and stated whether they support or contradict your hypothesis?

Have you used tables and figures to present all results?

In your thesis body, have you presented only the pertinent results and elaborated on specific aspects that were presented in the tables and figures?

Are all tables and figures correctly labeled and cited in numerical order in the text?

Frequently Asked Questions

What file formats do you accept +.

We accept all file formats, including Microsoft Word, Microsoft Excel, PDF, Latex, etc.

How to identify whether paraphrasing is required? +

We provide a report entailing recommendations for a single Plagiarism Check service. You can also write to us at [email protected] for further assistance as paraphrasing is sold offline and has a relatively high conversion in most geographies.

What information do i need to provide? +

Please upload your research manuscript when you place the order. If you want to include the tables, charts, and figure legends in the plagiarism check, please ensure that all content is in editable formats and in one single document.

Is repetition percentage of 25-30% considered acceptable by the journal for my manuscript? +

Acceptable repetition rate varies by journal but aim for low percentages (usually <5%). Avoid plagiarism, cite sources, and use detection tools. High plagiarism can lead to rejection, reputation damage, and serious consequences. Consult your institution for guidance on addressing plagiarism concerns.

Do you offer help to rewrite and paraphrase the plagiarized text in my manuscript? +

We can certainly help you rewrite and paraphrase text in your manuscript to ensure it is not plagiarized under our Developmental Content rewriting service. You can provide specific passages or sentences that you suspect may be plagiarized, and we can assist you in rephrasing them to ensure originality.

Which international languages does iThenticate have content for in its database? +

iThenticate searches for content matches in the following 30 languages: Chinese (Simplified and Traditional), Japanese, Thai, Korean, Catalan, Croatian, Czech, Danish, Dutch, Finnish, French, German, Hungarian, Italian, Norwegian (Bokmal, Nynorsk), Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Serbian, Slovak, Slovenian, Spanish, Swedish, Arabic, Greek, Hebrew, Farsi, Russian, and Turkish. Please note that iThenticate will match your text with text of the same language.

- How it works

How to Write the Thesis Or Dissertation Introduction – Guide

Published by Carmen Troy at August 31st, 2021 , Revised On January 24, 2024

Introducing your Dissertation Topic

What would you tell someone if they asked you to introduce yourself? You’d probably start with your name, what you do for a living…etc., etc., etc. Think of your dissertation. How would you go about it if you had to introduce it to the world for the first time?

Keep this forefront in your mind for the remainder of this guide: you are introducing your research to the world that doesn’t even know it exists. Every word, phrase and line you write in your introduction will stand for the strength of your dissertation’s character.

This is not very different from how, in real life, if someone fails to introduce themselves properly (such as leaving out what they do for a living, where they live, etc.) to a stranger, it leaves a lasting impression on the stranger.

Don’t leave your dissertation a stranger among other strangers. Let’s review the little, basic concepts we already have at the back of our minds, perhaps, to piece them together in one body: an introduction.

What Goes Inside an Introduction

The exact ingredients of a dissertation or thesis introduction chapter vary depending on your chosen research topic, your university’s guidelines, and your academic subject – but they are generally mixed in one sequence or another to introduce an academic argument.

The critical elements of an excellent dissertation introduction include a definition of the selected research topic , a reference to previous studies on the subject, a statement of the value of the subject for academic and scientific communities, a clear aim/purpose of the study, a list of your objectives, a reference to viewpoints of other researchers and a justification for the research.

Topic Discussion versus Topic Introduction

Discussing and introducing a topic are two highly different aspects of dissertation introduction writing. You might find it easy to discuss a topic, but introducing it is much trickier.

The introduction is the first thing a reader reads; thus, it must be to the point, informative, engaging, and enjoyable. Even if one of these elements is missing, the reader will not be motivated to continue reading the paper and will move on to something different.

So, it’s critical to fully understand how to write the introduction of a dissertation before starting the actual write-up.

When writing a dissertation introduction, one has to explain the title, discuss the topic and present a background so that readers understand what your research is about and what results you expect to achieve at the end of the research work.

As a standard practice, you might work on your dissertation introduction chapter several times. Once when you’re working on your proposal and the second time when writing your actual dissertation.

“ Want to keep up with the progress of the work done by your writer? ResearchProspect can deliver your dissertation order in three parts; outline, first half, and final dissertation delivery. Here is the link to our online order form .

Many academics argue that the Introduction chapter should be the last section of the dissertation paper you should complete, but by no means is it the last part you would think of because this is where your research starts from.

Write the draft introduction as early as possible. You should write it at the same time as the proposal submission, although you must revise and edit it many times before it takes the final shape.

Considering its importance, many students remain unsure of how to write the introduction of a dissertation. Here are some of the essential elements of how to write the introduction of a dissertation that’ll provide much-needed dissertation introduction writing help.

Below are some guidelines for you to learn to write a flawless first-class dissertation paper.

Steps of Writing a Dissertation Introduction

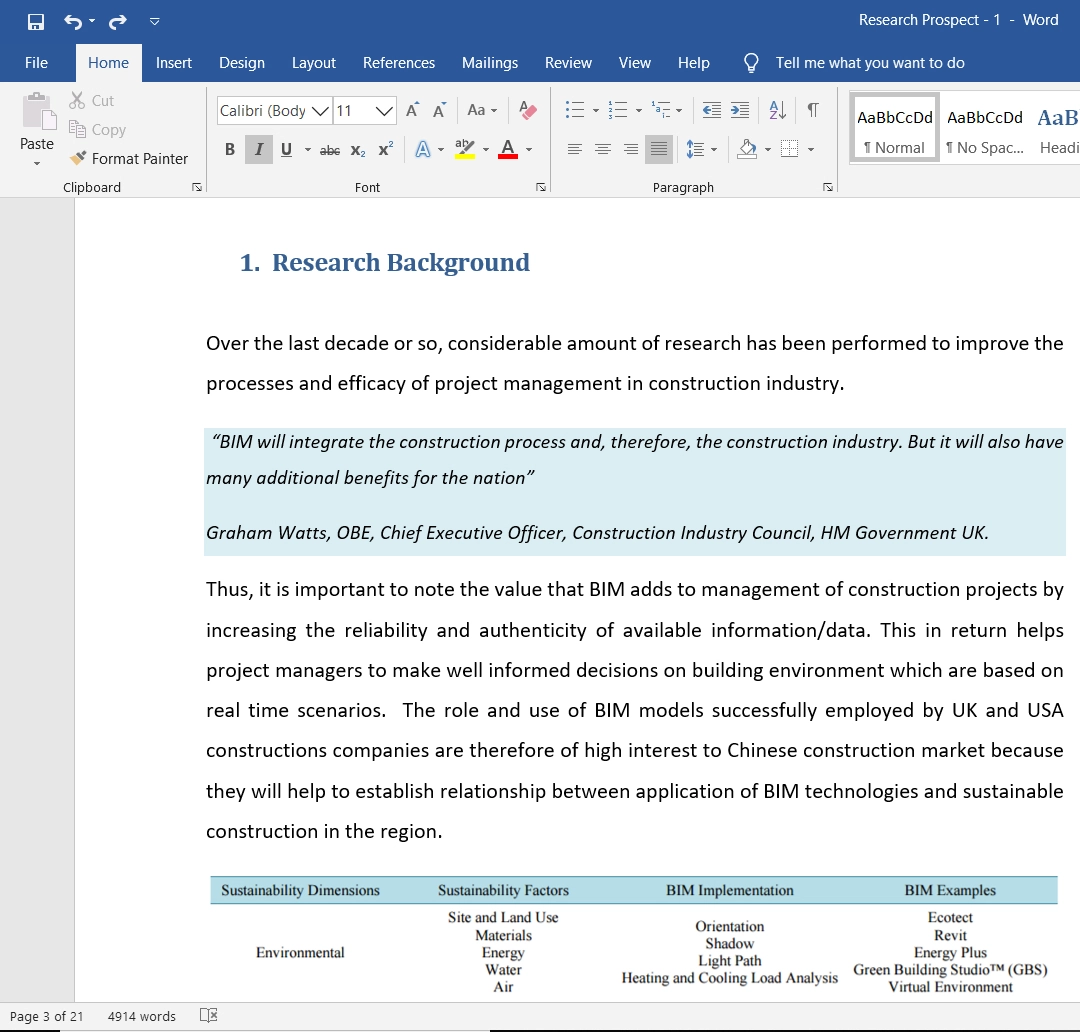

1. research background – writing a dissertation introduction.

This is the very first section of your introduction. Building a background of your chosen topic will help you understand more about the topic and help readers know why the general research area is problematic, interesting, central, important, etc.

Your research background should include significant concepts related to your dissertation topic. This will give your supervisor and markers an idea that you’ve investigated the research problem thoroughly and know the various aspects of your topic.

The introduction to a dissertation shouldn’t talk only about other research work in the same area, as this will be discussed in the literature review section. Moreover, this section should not include the research design and data collection method(s) .

All about research strategy should be covered in the methodology chapter . Research background only helps to build up your research in general.

For instance, if your research is based on job satisfaction measures of a specific country, the content of the introduction chapter will generally be about job satisfaction and its impact.

Hire an Expert Writer

Orders completed by our expert writers are

- Formally drafted in academic style

- Plagiarism free

- Never resold

- Include unlimited free revisions

- Completed to match exact client requirements

2. Significance of the Research

As a researcher, you must demonstrate how your research will provide value to the scientific and academic communities. If your dissertation is based on a specific company or industry, you need to explain why that industry and company were chosen.

If you’re comparing, explain why you’re doing so and what this research will yield. Regardless of your chosen research topic, explain thoroughly in this section why this research is being conducted and what benefits it will serve.

The idea here is to convince your supervisor and readers that the concept should be researched to find a solution to a problem.

3. Research Problem

Once you’ve described the main research problem and the importance of your research, the next step would be to present your problem statement , i.e., why this research is being conducted and its purpose.

This is one of the essential aspects of writing a dissertation’s introduction. Doing so will help your readers understand what you intend to do in this research and what they should expect from this study.

Presenting the research problem competently is crucial in persuading your readers to read other parts of the dissertation paper . This research problem is the crux of your dissertation, i.e., it gives a direction as to why this research is being carried out, and what issues the study will consider.

For example, if your dissertation is based on measuring the job satisfaction of a specific organisation, your research problem should talk about the problem the company is facing and how your research will help the company to solve that.

If your dissertation is not based on any specific organisation, you can explain the common issues that companies face when they do not consider job satisfaction as a pillar of business growth and elaborate on how your research will help them realise its importance.

Citing too many references in the introduction chapter isn’t recommended because here, you must explain why you chose to study a specific area and what your research will accomplish. Any citations only set the context, and you should leave the bulk of the literature for a later section.

4. Research Question(s)

The central part of your introduction is the research question , which should be based on your research problem and the dissertation title. Combining these two aspects will help you formulate an exciting yet manageable research question.

Your research question is what your research aims to answer and around which your dissertation will revolve. The research question should be specific and concise.

It should be a one- or two-line question you’ve set out to answer through your dissertation. For the job satisfaction example, a sample research question could be, how does job satisfaction positively impact employee performance?

Look up dissertation introduction examples online or ask your friends to get an idea of how an ideal research question is formed. Or you can review our dissertation introduction example here and research question examples here .

Once you’ve formed your research question, pick out vital elements from it, based on which you will then prepare your theoretical framework and literature review. You will come back to your research question again when concluding your dissertation .

Sometimes, you might have to formulate a hypothesis in place of a research question. The hypothesis is a simple statement you prove with your results , discussion and analysis .

A sample hypothesis could be job satisfaction is positively linked to employee job performance . The results of your dissertation could be in favour of this dissertation or against it.

Tip: Read up about what alternative, null, one-tailed and two-tailed hypotheses are so you can better formulate the hypothesis for your dissertation. Following are the definitions for each term, as retrieved from Trochim et al.’s Research Methods: The Essential Knowledge Base (2016):

- Alternative hypothesis (H 1 ): “A specific statement of prediction that usually states what you expect will happen in your study.”

- Null hypothesis (H 0 ): “The hypothesis that describes the possible outcomes other than the alternative hypothesis. Usually, the null hypothesis predicts there will be no effect of a program or treatment you are studying.”

- One-tailed hypothesis: “A hypothesis that specifies a direction; for example, when your hypothesis predicts that your program will increase the outcome.”

- Two-tailed hypothesis: “A hypothesis that does not specify a direction. For example, if you hypothesise that your program or intervention will affect an outcome, but you are unwilling to specify whether that effect will be positive or negative, you are using a two-tailed hypothesis.”

Get Help with Any Part of Your Dissertation!

UK’s best academic support services. How would you know until you try?

Interesting read: 10 ways to write a practical introduction fast .

Get Help With Any Part of Your Dissertation!

Uk’s best academic support services. how would you know until you try, 5. research aims and objectives.

Next, the research aims and objectives. Aims and objectives are broad statements of desired results of your dissertation . They reflect the expectations of the topic and research and address the long-term project outcomes.

These statements should use the concepts accurately, must be focused, should be able to convey your research intentions and serve as steps that communicate how your research question will be answered.

You should formulate your aims and objectives based on your topic, research question, or hypothesis. These are simple statements and are an extension of your research question.

Through the aims and objectives, you communicate to your readers what aspects of research you’ve considered and how you intend to answer your research question.

Usually, these statements initiate with words like ‘to explore’, ‘to study’, ‘to assess’, ‘to critically assess’, ‘to understand’, ‘to evaluate’ etc.

You could ask your supervisor to provide some thesis introduction examples to help you understand better how aims and objectives are formulated. More examples are here .

Your aims and objectives should be interrelated and connect to your research question and problem. If they do not, they’ll be considered vague and too broad in scope.

Always ensure your research aims and objectives are concise, brief, and relevant.

Once you conclude your dissertation , you will have to revert back to address whether your research aims and objectives have been met.

You will have to reflect on how your dissertation’s findings , analysis, and discussion related to your aims and objectives and how your research has helped in achieving them.

6. Research Limitations

This section is sometimes a part of the dissertation methodology section ; however, it is usually included in the introduction of a dissertation.

Every research has some limitations. Thus, it is normal for you to experience certain limitations when conducting your study.

You could experience research design limitations, data limitations or even financial limitations. Regardless of which type of limitation you may experience, your dissertation would be impacted. Thus, it would be best if you mentioned them without any hesitation.

When including this section in the introduction, make sure that you clearly state the type of constraint you experienced. This will help your supervisor understand what problems you went through while working on your dissertation.

However, one aspect that you should take care of is that your results, in no way, should be influenced by these restrictions. The results should not be compromised, or your dissertation will not be deemed authentic and reliable.

After you’ve mentioned your research limitations, discuss how you overcame them to produce a perfect dissertation .

Also, mention that your limitations do not adversely impact your results and that you’ve produced research with accurate results the academic community can rely on.

Also read: How to Write Dissertation Methodology .

7. Outline of the Dissertation

Even though this isn’t a mandatory sub-section of the introduction chapter, good introductory chapters in dissertations outline what’s to follow in the preceding chapters.

It is also usual to set out an outline of the rest of the dissertation . Depending on your university and academic subject, you might also be asked to include it in your research proposal .

Because your tutor might want to glance over it to see how you plan your dissertation and what sections you’d include; based on what sections you include and how you intend to research and cover them, they’d provide feedback for you to improve.

Usually, this section discusses what sections you plan to include and what concepts and aspects each section entails. A standard dissertation consists of five sections : chapters, introduction, literature review , methodology , results and discussion , and conclusion .

Some dissertation assignments do not use the same chapter for results and discussion. Instead, they split it into two different chapters, making six chapters. Check with your supervisor regarding which format you should follow.

When discussing the outline of your dissertation , remember that you’d have to mention what each section involves. Discuss all the significant aspects of each section to give a brief overview of what your dissertation contains, and this is precisely what our dissertation outline service provides.

Writing a dissertation introduction might seem complicated, but it is not if you understand what is expected of you. To understand the required elements and make sure that you focus on all of them.

Include all the aspects to ensure your supervisor and other readers can easily understand how you intend to undertake your research.

“If you find yourself stuck at any stage of your dissertation introduction, get introduction writing help from our writers! At ResearchProspect, we offer a dissertation writing service , and our qualified team of writers will also assist you in conducting in-depth research for your dissertation.

Dissertation Introduction Samples & Examples

Check out some basic samples of dissertation introduction chapters to get started.

FAQs about Dissertation Introduction

What is the purpose of an introduction chapter.

It’s used to introduce key constructs, ideas, models and/or theories etc. relating to the topic; things that you will be basing the remainder of your dissertation on.

How do you start an introduction in a dissertation?

There is more than one way of starting a dissertation’s introductory chapter. You can begin by stating a problem in your area of interest, review relevant literature, identify the gap, and introduce your topic. Or, you can go the opposite way, too. It’s all entirely up to your discretion. However, be consistent in the format you choose to write in.

How long can an introduction get?

It can range from 1000 to 2000 words for a master’s dissertation , but for a higher-level dissertation, it mostly ranges from 8,000 to 10,000 words ’ introduction chapter. In the end, though, it depends on the guidelines provided to you by your department.

Steps to Writing a Dissertation Introduction

You may also like.

Make sure that your selected topic is intriguing, manageable, and relevant. Here are some guidelines to help understand how to find a good dissertation topic.

If your dissertation includes many abbreviations, it would make sense to define all these abbreviations in a list of abbreviations in alphabetical order.

Dissertation conclusion is perhaps the most underrated part of a dissertation or thesis paper. Learn how to write a dissertation conclusion.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

Student Learning

Writing the results chapter.

The results section describes the data that you gathered and the outcomes of the analysis of that data.

In this section, you will typically find:

- graphs, tables, and charts supported by written descriptions and made identifiable by a title or legend

- key findings emphasized—qualitative research often includes historical sources or interview excerpts, while quantitative research will often include measurements or observations from experiments

- in-text citations are infrequent or absent.

This chapter of your thesis lays the foundations for your Discussion chapter where you can elaborate on the implications of your results for theory or practice in your discipline.

Presenting your data will involve making decisions about what is most important for your reader to understand about how you have addressed your research questions. Make decisions about what specific data to present in this section by thinking back to your research question or your research aims.

You might think of the metaphor of the carpenter who has more than enough wood to build with but will only succeed by selecting what is most suitable for the particular task:

“[Data] is a resource you can use to support the claims you want to make. Carpenters don’t try to use all the wood in the woodshed to make a particular table. They don’t see the variety of materials they have available as a problem to be solved... Think of the abundance of your data in the same way.” —from Inframethodology

Video resource

The video below details the features of a good results chapter and the process that goes into preparing it.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Thesis – Structure, Example and Writing Guide

Thesis – Structure, Example and Writing Guide

Table of contents.

Definition:

Thesis is a scholarly document that presents a student’s original research and findings on a particular topic or question. It is usually written as a requirement for a graduate degree program and is intended to demonstrate the student’s mastery of the subject matter and their ability to conduct independent research.

History of Thesis

The concept of a thesis can be traced back to ancient Greece, where it was used as a way for students to demonstrate their knowledge of a particular subject. However, the modern form of the thesis as a scholarly document used to earn a degree is a relatively recent development.

The origin of the modern thesis can be traced back to medieval universities in Europe. During this time, students were required to present a “disputation” in which they would defend a particular thesis in front of their peers and faculty members. These disputations served as a way to demonstrate the student’s mastery of the subject matter and were often the final requirement for earning a degree.

In the 17th century, the concept of the thesis was formalized further with the creation of the modern research university. Students were now required to complete a research project and present their findings in a written document, which would serve as the basis for their degree.

The modern thesis as we know it today has evolved over time, with different disciplines and institutions adopting their own standards and formats. However, the basic elements of a thesis – original research, a clear research question, a thorough review of the literature, and a well-argued conclusion – remain the same.

Structure of Thesis

The structure of a thesis may vary slightly depending on the specific requirements of the institution, department, or field of study, but generally, it follows a specific format.

Here’s a breakdown of the structure of a thesis:

This is the first page of the thesis that includes the title of the thesis, the name of the author, the name of the institution, the department, the date, and any other relevant information required by the institution.

This is a brief summary of the thesis that provides an overview of the research question, methodology, findings, and conclusions.

This page provides a list of all the chapters and sections in the thesis and their page numbers.

Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the research question, the context of the research, and the purpose of the study. The introduction should also outline the methodology and the scope of the research.

Literature Review

This chapter provides a critical analysis of the relevant literature on the research topic. It should demonstrate the gap in the existing knowledge and justify the need for the research.

Methodology

This chapter provides a detailed description of the research methods used to gather and analyze data. It should explain the research design, the sampling method, data collection techniques, and data analysis procedures.

This chapter presents the findings of the research. It should include tables, graphs, and charts to illustrate the results.

This chapter interprets the results and relates them to the research question. It should explain the significance of the findings and their implications for the research topic.

This chapter summarizes the key findings and the main conclusions of the research. It should also provide recommendations for future research.

This section provides a list of all the sources cited in the thesis. The citation style may vary depending on the requirements of the institution or the field of study.

This section includes any additional material that supports the research, such as raw data, survey questionnaires, or other relevant documents.

How to write Thesis

Here are some steps to help you write a thesis:

- Choose a Topic: The first step in writing a thesis is to choose a topic that interests you and is relevant to your field of study. You should also consider the scope of the topic and the availability of resources for research.

- Develop a Research Question: Once you have chosen a topic, you need to develop a research question that you will answer in your thesis. The research question should be specific, clear, and feasible.

- Conduct a Literature Review: Before you start your research, you need to conduct a literature review to identify the existing knowledge and gaps in the field. This will help you refine your research question and develop a research methodology.

- Develop a Research Methodology: Once you have refined your research question, you need to develop a research methodology that includes the research design, data collection methods, and data analysis procedures.

- Collect and Analyze Data: After developing your research methodology, you need to collect and analyze data. This may involve conducting surveys, interviews, experiments, or analyzing existing data.

- Write the Thesis: Once you have analyzed the data, you need to write the thesis. The thesis should follow a specific structure that includes an introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, conclusion, and references.

- Edit and Proofread: After completing the thesis, you need to edit and proofread it carefully. You should also have someone else review it to ensure that it is clear, concise, and free of errors.

- Submit the Thesis: Finally, you need to submit the thesis to your academic advisor or committee for review and evaluation.

Example of Thesis

Example of Thesis template for Students:

Title of Thesis

Table of Contents:

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: Literature Review

Chapter 3: Research Methodology

Chapter 4: Results

Chapter 5: Discussion

Chapter 6: Conclusion

References:

Appendices:

Note: That’s just a basic template, but it should give you an idea of the structure and content that a typical thesis might include. Be sure to consult with your department or supervisor for any specific formatting requirements they may have. Good luck with your thesis!

Application of Thesis

Thesis is an important academic document that serves several purposes. Here are some of the applications of thesis:

- Academic Requirement: A thesis is a requirement for many academic programs, especially at the graduate level. It is an essential component of the evaluation process and demonstrates the student’s ability to conduct original research and contribute to the knowledge in their field.

- Career Advancement: A thesis can also help in career advancement. Employers often value candidates who have completed a thesis as it demonstrates their research skills, critical thinking abilities, and their dedication to their field of study.

- Publication : A thesis can serve as a basis for future publications in academic journals, books, or conference proceedings. It provides the researcher with an opportunity to present their research to a wider audience and contribute to the body of knowledge in their field.

- Personal Development: Writing a thesis is a challenging task that requires time, dedication, and perseverance. It provides the student with an opportunity to develop critical thinking, research, and writing skills that are essential for their personal and professional development.

- Impact on Society: The findings of a thesis can have an impact on society by addressing important issues, providing insights into complex problems, and contributing to the development of policies and practices.

Purpose of Thesis

The purpose of a thesis is to present original research findings in a clear and organized manner. It is a formal document that demonstrates a student’s ability to conduct independent research and contribute to the knowledge in their field of study. The primary purposes of a thesis are:

- To Contribute to Knowledge: The main purpose of a thesis is to contribute to the knowledge in a particular field of study. By conducting original research and presenting their findings, the student adds new insights and perspectives to the existing body of knowledge.

- To Demonstrate Research Skills: A thesis is an opportunity for the student to demonstrate their research skills. This includes the ability to formulate a research question, design a research methodology, collect and analyze data, and draw conclusions based on their findings.

- To Develop Critical Thinking: Writing a thesis requires critical thinking and analysis. The student must evaluate existing literature and identify gaps in the field, as well as develop and defend their own ideas.

- To Provide Evidence of Competence : A thesis provides evidence of the student’s competence in their field of study. It demonstrates their ability to apply theoretical concepts to real-world problems, and their ability to communicate their ideas effectively.

- To Facilitate Career Advancement : Completing a thesis can help the student advance their career by demonstrating their research skills and dedication to their field of study. It can also provide a basis for future publications, presentations, or research projects.

When to Write Thesis

The timing for writing a thesis depends on the specific requirements of the academic program or institution. In most cases, the opportunity to write a thesis is typically offered at the graduate level, but there may be exceptions.

Generally, students should plan to write their thesis during the final year of their graduate program. This allows sufficient time for conducting research, analyzing data, and writing the thesis. It is important to start planning the thesis early and to identify a research topic and research advisor as soon as possible.

In some cases, students may be able to write a thesis as part of an undergraduate program or as an independent research project outside of an academic program. In such cases, it is important to consult with faculty advisors or mentors to ensure that the research is appropriately designed and executed.

It is important to note that the process of writing a thesis can be time-consuming and requires a significant amount of effort and dedication. It is important to plan accordingly and to allocate sufficient time for conducting research, analyzing data, and writing the thesis.

Characteristics of Thesis

The characteristics of a thesis vary depending on the specific academic program or institution. However, some general characteristics of a thesis include:

- Originality : A thesis should present original research findings or insights. It should demonstrate the student’s ability to conduct independent research and contribute to the knowledge in their field of study.

- Clarity : A thesis should be clear and concise. It should present the research question, methodology, findings, and conclusions in a logical and organized manner. It should also be well-written, with proper grammar, spelling, and punctuation.

- Research-Based: A thesis should be based on rigorous research, which involves collecting and analyzing data from various sources. The research should be well-designed, with appropriate research methods and techniques.

- Evidence-Based : A thesis should be based on evidence, which means that all claims made in the thesis should be supported by data or literature. The evidence should be properly cited using appropriate citation styles.

- Critical Thinking: A thesis should demonstrate the student’s ability to critically analyze and evaluate information. It should present the student’s own ideas and arguments, and engage with existing literature in the field.

- Academic Style : A thesis should adhere to the conventions of academic writing. It should be well-structured, with clear headings and subheadings, and should use appropriate academic language.

Advantages of Thesis

There are several advantages to writing a thesis, including:

- Development of Research Skills: Writing a thesis requires extensive research and analytical skills. It helps to develop the student’s research skills, including the ability to formulate research questions, design and execute research methodologies, collect and analyze data, and draw conclusions based on their findings.

- Contribution to Knowledge: Writing a thesis provides an opportunity for the student to contribute to the knowledge in their field of study. By conducting original research, they can add new insights and perspectives to the existing body of knowledge.

- Preparation for Future Research: Completing a thesis prepares the student for future research projects. It provides them with the necessary skills to design and execute research methodologies, analyze data, and draw conclusions based on their findings.

- Career Advancement: Writing a thesis can help to advance the student’s career. It demonstrates their research skills and dedication to their field of study, and provides a basis for future publications, presentations, or research projects.

- Personal Growth: Completing a thesis can be a challenging and rewarding experience. It requires dedication, hard work, and perseverance. It can help the student to develop self-confidence, independence, and a sense of accomplishment.

Limitations of Thesis

There are also some limitations to writing a thesis, including:

- Time and Resources: Writing a thesis requires a significant amount of time and resources. It can be a time-consuming and expensive process, as it may involve conducting original research, analyzing data, and producing a lengthy document.

- Narrow Focus: A thesis is typically focused on a specific research question or topic, which may limit the student’s exposure to other areas within their field of study.

- Limited Audience: A thesis is usually only read by a small number of people, such as the student’s thesis advisor and committee members. This limits the potential impact of the research findings.

- Lack of Real-World Application : Some thesis topics may be highly theoretical or academic in nature, which may limit their practical application in the real world.

- Pressure and Stress : Writing a thesis can be a stressful and pressure-filled experience, as it may involve meeting strict deadlines, conducting original research, and producing a high-quality document.

- Potential for Isolation: Writing a thesis can be a solitary experience, as the student may spend a significant amount of time working independently on their research and writing.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

- Directories

Chapter introductions

Your overall thesis objectives or questions can be distinguished from specific objectives of each chapter, however, it should be broad enough to embody the latter. So whenever you have difficulty deciding what information to include in the thesis introduction and what to include in the introductory sections of individual chapters, remember it's primarily a matter of scale (see the table below).

Introductions

- ANU Library Academic Skills

- +61 2 6125 2972

Dissertation Structure & Layout 101: How to structure your dissertation, thesis or research project.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) Reviewed By: David Phair (PhD) | July 2019

So, you’ve got a decent understanding of what a dissertation is , you’ve chosen your topic and hopefully you’ve received approval for your research proposal . Awesome! Now its time to start the actual dissertation or thesis writing journey.

To craft a high-quality document, the very first thing you need to understand is dissertation structure . In this post, we’ll walk you through the generic dissertation structure and layout, step by step. We’ll start with the big picture, and then zoom into each chapter to briefly discuss the core contents. If you’re just starting out on your research journey, you should start with this post, which covers the big-picture process of how to write a dissertation or thesis .

*The Caveat *

In this post, we’ll be discussing a traditional dissertation/thesis structure and layout, which is generally used for social science research across universities, whether in the US, UK, Europe or Australia. However, some universities may have small variations on this structure (extra chapters, merged chapters, slightly different ordering, etc).

So, always check with your university if they have a prescribed structure or layout that they expect you to work with. If not, it’s safe to assume the structure we’ll discuss here is suitable. And even if they do have a prescribed structure, you’ll still get value from this post as we’ll explain the core contents of each section.

Overview: S tructuring a dissertation or thesis

- Acknowledgements page

- Abstract (or executive summary)

- Table of contents , list of figures and tables

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Literature review

- Chapter 3: Methodology

- Chapter 4: Results

- Chapter 5: Discussion

- Chapter 6: Conclusion

- Reference list

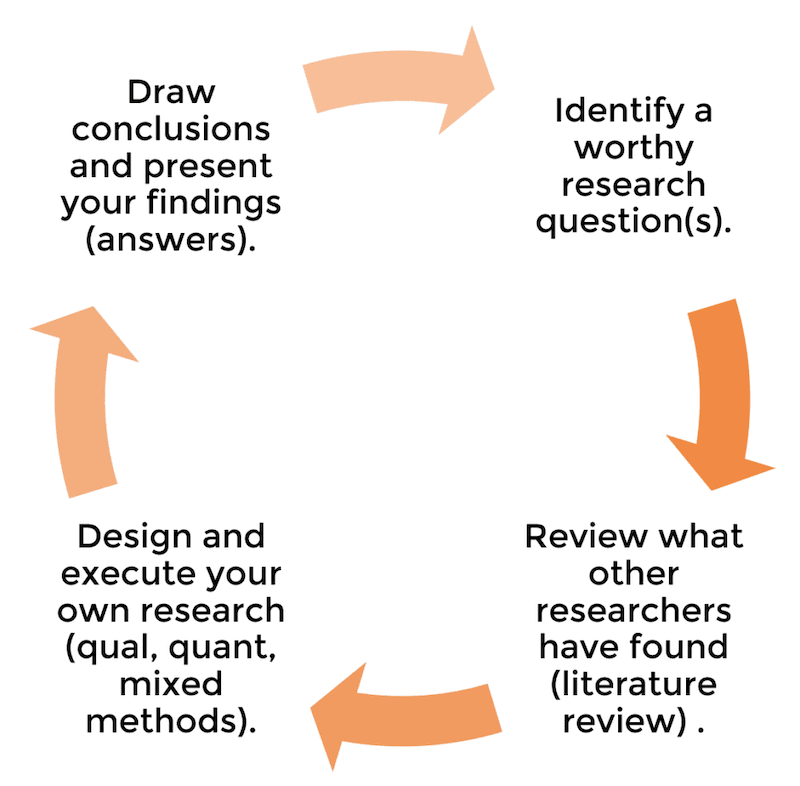

As I mentioned, some universities will have slight variations on this structure. For example, they want an additional “personal reflection chapter”, or they might prefer the results and discussion chapter to be merged into one. Regardless, the overarching flow will always be the same, as this flow reflects the research process , which we discussed here – i.e.:

- The introduction chapter presents the core research question and aims .

- The literature review chapter assesses what the current research says about this question.

- The methodology, results and discussion chapters go about undertaking new research about this question.

- The conclusion chapter (attempts to) answer the core research question .

In other words, the dissertation structure and layout reflect the research process of asking a well-defined question(s), investigating, and then answering the question – see below.

To restate that – the structure and layout of a dissertation reflect the flow of the overall research process . This is essential to understand, as each chapter will make a lot more sense if you “get” this concept. If you’re not familiar with the research process, read this post before going further.

Right. Now that we’ve covered the big picture, let’s dive a little deeper into the details of each section and chapter. Oh and by the way, you can also grab our free dissertation/thesis template here to help speed things up.

The title page of your dissertation is the very first impression the marker will get of your work, so it pays to invest some time thinking about your title. But what makes for a good title? A strong title needs to be 3 things:

- Succinct (not overly lengthy or verbose)

- Specific (not vague or ambiguous)

- Representative of the research you’re undertaking (clearly linked to your research questions)

Typically, a good title includes mention of the following:

- The broader area of the research (i.e. the overarching topic)

- The specific focus of your research (i.e. your specific context)

- Indication of research design (e.g. quantitative , qualitative , or mixed methods ).

For example:

A quantitative investigation [research design] into the antecedents of organisational trust [broader area] in the UK retail forex trading market [specific context/area of focus].

Again, some universities may have specific requirements regarding the format and structure of the title, so it’s worth double-checking expectations with your institution (if there’s no mention in the brief or study material).

Acknowledgements

This page provides you with an opportunity to say thank you to those who helped you along your research journey. Generally, it’s optional (and won’t count towards your marks), but it is academic best practice to include this.

So, who do you say thanks to? Well, there’s no prescribed requirements, but it’s common to mention the following people:

- Your dissertation supervisor or committee.

- Any professors, lecturers or academics that helped you understand the topic or methodologies.

- Any tutors, mentors or advisors.

- Your family and friends, especially spouse (for adult learners studying part-time).

There’s no need for lengthy rambling. Just state who you’re thankful to and for what (e.g. thank you to my supervisor, John Doe, for his endless patience and attentiveness) – be sincere. In terms of length, you should keep this to a page or less.

Abstract or executive summary

The dissertation abstract (or executive summary for some degrees) serves to provide the first-time reader (and marker or moderator) with a big-picture view of your research project. It should give them an understanding of the key insights and findings from the research, without them needing to read the rest of the report – in other words, it should be able to stand alone .

For it to stand alone, your abstract should cover the following key points (at a minimum):

- Your research questions and aims – what key question(s) did your research aim to answer?

- Your methodology – how did you go about investigating the topic and finding answers to your research question(s)?

- Your findings – following your own research, what did do you discover?

- Your conclusions – based on your findings, what conclusions did you draw? What answers did you find to your research question(s)?

So, in much the same way the dissertation structure mimics the research process, your abstract or executive summary should reflect the research process, from the initial stage of asking the original question to the final stage of answering that question.