The qualitative research process, end-to-end

.css-1nrevy2{position:relative;display:inline-block;} The qualitative research process: step by step guide

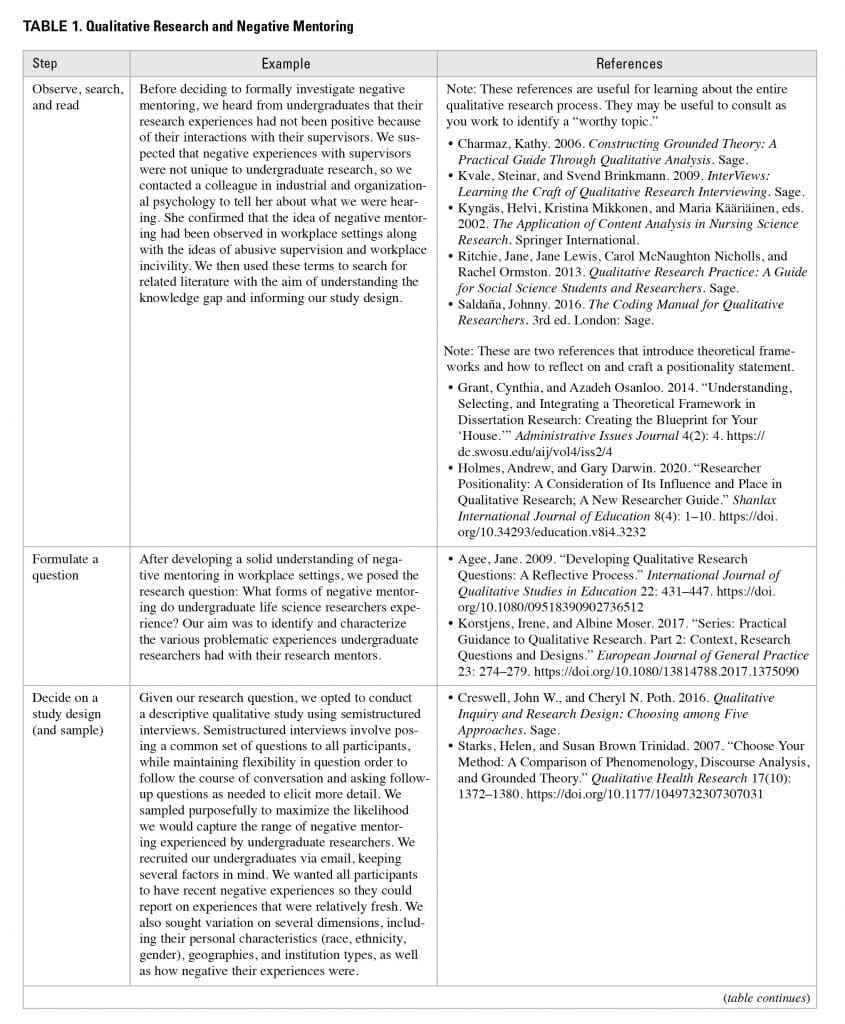

Although research processes may vary by methodology or project team, some fundamentals exist across research projects. Below outlines the collective experience that qualitative researchers undertake to conduct research.

Step 1: Determine what to research

Once a researcher has determined a list of potential projects to tackle, they will prioritize projects based on the business's impact, available resourcing, timelines & dependencies to create a research roadmap. For each project, they will also identify the key questions they need to answer in the research.

The researcher should identify the participants they plan to research, and any key attributes that are a 'must-have' or 'nice to have' as these can be influential in determining the research approach (e.g. a niche group may require a longer timeline to recruit).

Researchers will generally aim for a mix of project types. Some may be more tactical or requests from stakeholders, and some will be projects that the researcher has proactively identified as opportunities for strategic research.

Step 2: Identify how to research it

Once the researcher has finalized the research project, they will need to figure out how they will do the work.

Firstly, the researcher will look through secondary data and research (e.g. analytics, previous research reports). Secondary analysis will help determine if there are existing answers to any of the open questions, ensuring that any net-new study doesn't duplicate current work (unless previous research is out of date).

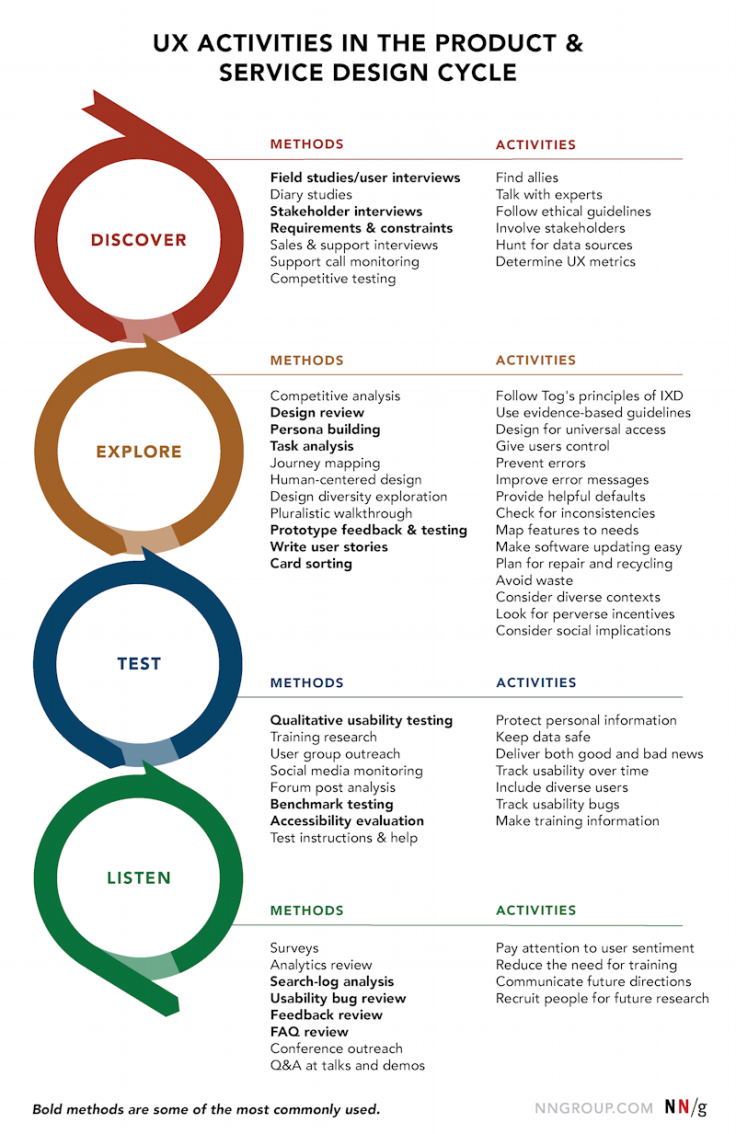

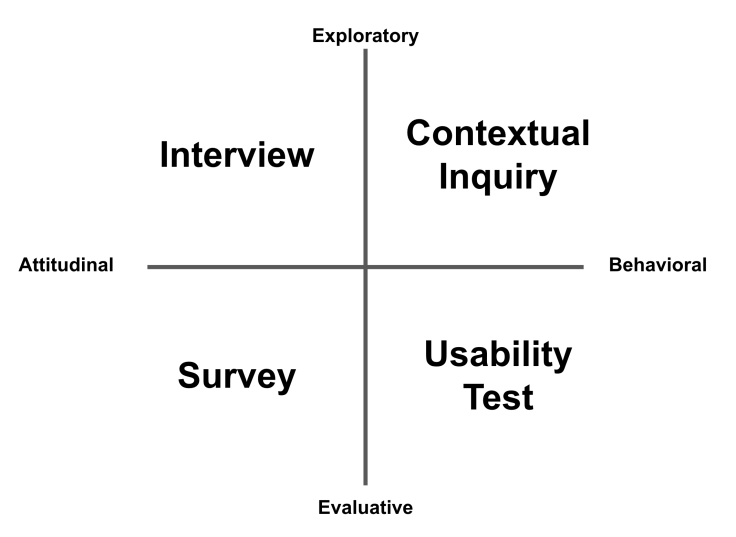

After scoping the research, researchers will determine if the research input needs to be attitudinal (i.e. what someone says) or behavioral (i.e. what someone does); as well as if they need to explore a problem space or evaluate a product – these help determine the methodology to use. There are many methodologies out there, but the main ones you generally will find from a qualitative perspective are:

Interviews [Attitudinal / Exploratory] – semi-structured conversation with a participant focused on a small set of topics. Runs for 30-60 minutes.

Contextual Inquiry [Behavioral / Exploratory] – observation of a participant in their environment. Probing questions may be asked during the observation. Runs for 2-3 hours.

Survey [Attitudinal / Evaluative] – gathering structured information from a sample of people, traditionally to generalize the results to a larger population. Surveys should generally not take participants more than 10 minutes to complete.

Usability Test [Behavioral / Evaluative] – evaluating how representative users are, or are not, able to achieve critical tasks within an experience.

Check out these articles for more information about different methodologies:

When to Use Which User-Experience Research Methods

UX Research Cheat Sheet

Usability.gov

Design Research Kit

Step 3: Get buy-in and alignment from others

Once a researcher has determined what they will be researching and how they will research it, they will generally write up a research plan that includes additional information about the research goals, participant scope, timelines, and dependencies. The plan is typically either a document or presentation shared with stakeholders depending on the company and how they work.

After the research plan is complete, researchers will share the plan for feedback and input from their stakeholders to ensure that the stakeholders have the right expectations going into the research. Stakeholders may ask for additional question topics to be added, ensure that research will be executed against specific timelines, or provide recommendations on how the study will help make product decisions.

At organizations where there is a research team, researchers may also share their plan with other researchers informally or through a 'crit' process. Generally, researchers will provide feedback on the research craft, such as methodologies, participant mixes, and the research goals or questions.

Once the researcher feels confident in their plan, they will either begin to plan the research, or in the case of more junior researchers, get approval from their manager to begin the study.

Step 4: Prepare research

This step is where the researcher will get all of their ducks in a row to execute the research. Preparation activities include:

Equipment: Booking venues, labs, observation rooms, and procuring any appropriate equipment needed to run the study (e.g. cameras, mobile devices).

Participants: Sourcing participants from internal / external databases, reaching out/scheduling participants, managing schedule changes.

Incentives: Find budget, identify incentive type (e.g. Amazon gift card? customer credit? gift baskets), and purchasing.

Assets: Building relevant designs / prototypes (with design or design technologists), creating interview / observation guides and other research tools needed for sessions (e.g. physical cards for in-person card sorts).

Legal & Procurement: Participant waivers or NDAs preparation to ensure they are sent in advance of the research session to participants, vendor procurement, and management.

If Research Operations exists within an organization, they will generally take on most of the load in this area. The researcher will focus on assets required for executing research, such as interview guides.

In some cases, vendors may be engaged for some of these requirements (e.g. labs, participants, and incentive management) if resourcing is not available internally or if a researcher wants a blinded study (i.e. the participant doesn't know what company is running the research). In this case, additional time is incorporated to brief, onboard, and get approvals to work with the vendor.

Step 5: Execute research

Now the researcher gets to research!

Researchers will generally aim to execute research activities for 1–2 weeks, depending on the methodology to ensure they can be efficient in execution. In some more longitudinal methods (e.g., diary studies), or if a participant type is harder to recruit, it may take longer.

In consumer research, there will usually be back up participants available in case of no shows. However, in business or enterprise research, researchers will engage will all recruited participants as participants will generally have relationships with other parts of the company (e.g. sales). It is essential to maintain those relationships post-research.

During sessions, in a perfect world, there is one facilitator (principal researcher). In some cases, a secondary attendee who takes notes – this can be a stakeholder or a more junior researcher who can then learn soft skills from the primary researcher. By delegating note-taking, the principal researcher can focus on driving and managing the participant's conversation.

However, in most cases (especially if there is a "research team of one"), researchers will try to have to do both facilitation and documentation – this can lead to a clunkier conversation as the facilitator attempts to quickly write notes between trying to think of the next question. If a researcher decides to record a session instead, they will have to spend additional time after the research listening to the full recordings and writing notes.

In qualitative research, researchers may begin to see patterns in the findings after five sessions . They may start to tailor the research questions to be more specific to gaps in their understanding.

Researchers may also set up an observation room for stakeholders (or share links to remote sessions) to attend live. Generally, researchers will have a backchannel (e.g., slack, chat, or SMS), so if a stakeholder has a follow-up question to an answer, the researcher can dig deeper. In some cases, researchers will give stakeholders an input form to take their notes that can be shared with the researcher afterward - this can be useful for the researcher to understand how the stakeholder views the research and what the stakeholder perceives as necessary to the research insights.

Step 6: Synthesize and find insights

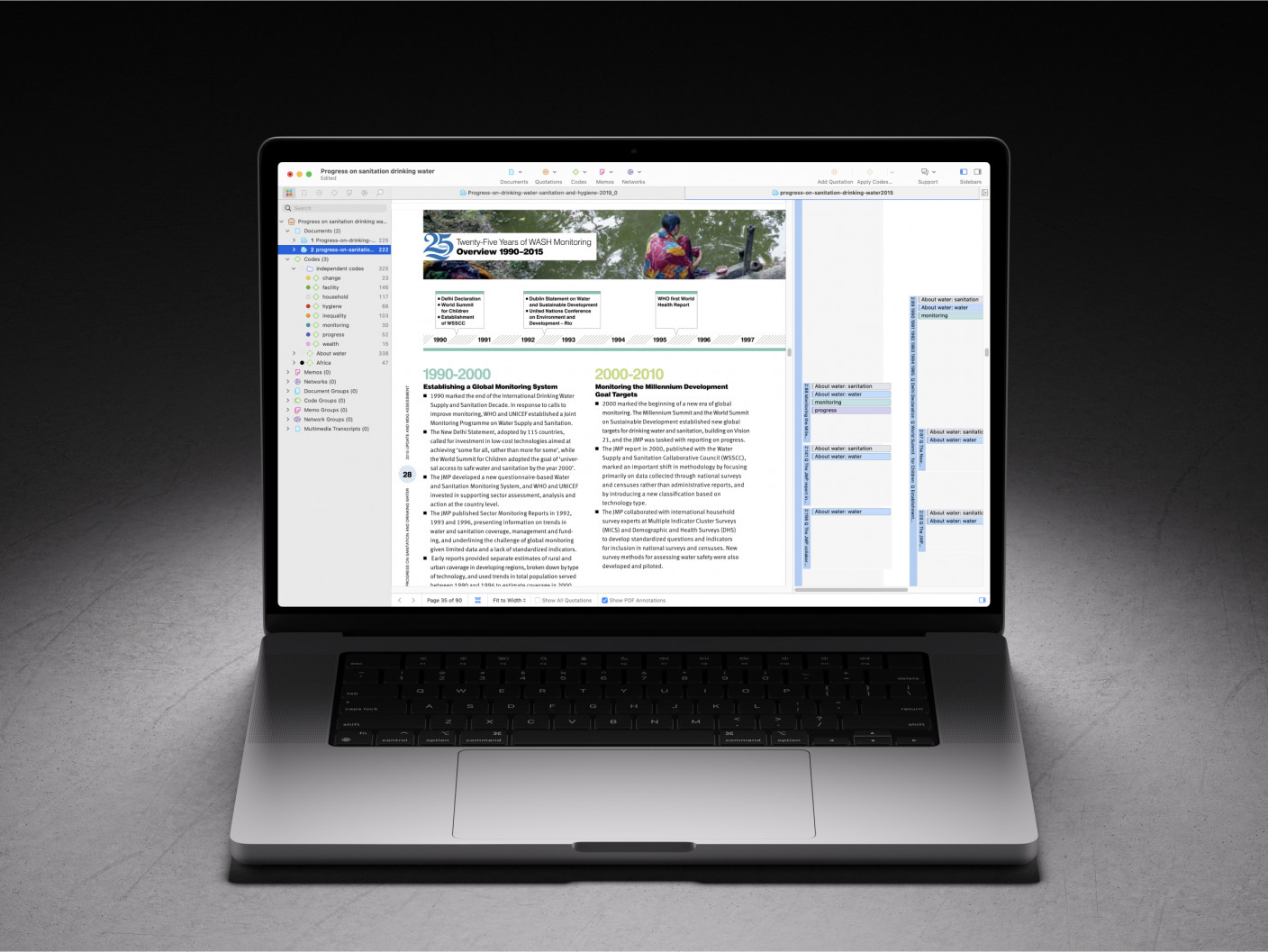

Once the research capture is complete, the researcher will then aggregate findings to begin to look for common themes (in exploratory) or success rates (in evaluative). Both of these will then lead to insight generation that researchers will then look to tie back to the project's original research goals.

As analysis can be one of the most high-effort tasks in research, researchers will lean towards how to be efficient in their study, generally using digital tools, hacks, or workarounds. Researchers will usually create the analysis process they refine throughout their careers to help them become more efficient.

In cases where researchers are looking to get buy-in for research or capture stakeholder input, they may seem to more visual approaches (e.g. post-it affinity analysis) in war rooms. This process can take longer to process (especially if there is a high volume of data). Still, there can be a higher impact on analyzing research in this way – especially if the researcher is looking to get buy-in for future projects.

Step 7: Create research outputs

After a researcher identifies the key themes and insights, the researcher will reframe these findings to a relevant research output to ensure that stakeholders understand and buy-in to the outcomes. Outputs may include:

Report: Outlines vital findings from research in a document or presentation format. Will most likely include an executive summary, insight themes, and supporting evidence.

Videos: A highlight reel of supporting evidence from crucial findings. Generally seen as more useful and engaging compared to just a report. In most cases, the video will help the research report.

Personas : A written representation of a product's intended users to understand different types of user goals, needs, and behaviors. Also used to help stakeholders build empathy for the end-user of the product.

Journey Map : A visualization of the process that a person goes through to accomplish a goal. Generally created in conjunction with a persona.

Concepts / Wireframes / Designs: If research is evaluative, designs can visualize recommendations.

Storyboarding

Before a researcher makes the output, researchers will spend time planning the structure and storyboarding. Storyboarding is incredibly essential to help researchers define information requirements and ensure they present their findings in the most impactful way to stakeholders.

Having a point of view in outputs

Historically, researchers have tried to stay neutral to the data and not try to have a strong opinion or perspective to let the data speak. However, as researchers become more embedded in the industry, this has shifted to stakeholders wanting a strong point of view or recommendations from researchers that can help other stakeholders (especially product managers and designers) decide the knowledge captured as part of the research.

Having a strong perspective helps researchers have a seat at the table and appear as a trusted advisor/partner in cross-functional settings.

Step 8: Share and follow up on findings

After the research outputs are complete, some researchers will do a "pre-share" or walkthrough with key stakeholders or potential detractors to the research. The purpose of these meetings is to align with stakeholders' expectations and find potential 'watch-outs' (things that may derail a presentation).

Researchers will generally have to share their findings out multiple times to different stakeholder groups and tailor them for each audience. For example, executive meetings will be more higher level than a meeting with a product manager.

After sharing, researchers will follow up with key stakeholders (especially those who provided input to the research) to confirm they understand the findings and identify next steps. Next steps may include incorporating results in product strategy documents, proposals / PRDs, or user stories to ensure that the recommendations or findings have been reflected or sourced.

Keep reading

.css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} Decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next

Decide what to build next.

Users report unexpectedly high data usage, especially during streaming sessions.

Users find it hard to navigate from the home page to relevant playlists in the app.

It would be great to have a sleep timer feature, especially for bedtime listening.

I need better filters to find the songs or artists I’m looking for.

Log in or sign up

Get started for free

7 Steps to Conducting Better Qualitative Research

While qualitative research is the collection and analysis of primarily non-numerical activities (words, pictures and actions), it doesn’t mean you can’t apply a structured approach to your research efforts.

Usability testing is often characterized as a qualitative activity. Summarizing findings from watching participants in a usability test generates a lot of utterances, actions and images.

In reality, usability testing is (or at least should be) a mixed-method approach: both qualitative and quantitative data are collected.

Here are seven steps to help structure your next qualitative research effort. These have been adapted from Johnson & Christensen 2012 to focus on the type of qualitative research more typical in User Experience such as usability tests or contextual inquires (where an interface is usually involved).

You don’t need to follow these steps linearly, or even include them all in your research, but having these steps should both help structure your next project and help focus the discussion the next time you’re working with someone who proposes a qualitative research approach.

- Determine Research Questions : Focused questions are at the heart of actionable qualitative research. In fact, they are at the heart of good quantitative research as well and play a key role in Lean UX thinking . Are users not using the mobile app because of usability, security concerns or something else? How do users make decisions about how to invest: do they ask a friend, use a financial advisor, or research on their own?

- Collect Data : The qualitative researcher should assume the role of an unobtrusive observer and have little impact on the settings being observed—whether it be watching participants use existing products at home or in a more controlled lab environment. Qualitative is often used synonymously with small samples, but one can take a qualitative approach to larger sample sizes (more than 50 participants) just as one can take a quantitative approach to small sample sizes (less than 10).

- Analyze Data : Most qualitative research studies generate a lot of data. Creating a system for coding actions and notable quotes helps speed through the process of turning utterances into actionable insights .

- Generate Findings : What was learned from engaging users? This step involves synthesizing the copious amount of notes, videos and artifacts. As many of the responses from participants will be open-ended, there will be a need to identify patterns . For example, when we were interviewing users about why they didn’t pay their credit card bill on their mobile phone, we didn’t ask users if they had security concerns. Instead, many of them voiced the concern in their own words and stories.

- Validate findings : One of the best ways to validate findings is to triangulate using other methods , including surveys or additional sources. One weakness of qualitative research is that it is hard to establish external validity, that is, to provide corroborating evidence that the findings aren’t just the opinion of the researcher. Every researcher, of course, does bring with her biases on the problems with a product or what deserves emphasis in the interview.One approach to minimize this researcher bias is to include a section on the interviewer or principal investigator’s background and how it might influence their conclusions. Having recordings of sessions and detailed notes helps other interested parties come to their own conclusions and can help validate findings. Including verbatims along with the interpretation also helps others see how the conclusions were drawn.

- Report : We usually deliver a power point with backup notes or an appendix with more detailed findings and verbatims. While information comes in sequentially from each participant, we find reporting the data in an inverted pyramid by issue works best. We start with the most important findings, and then note the number of participants that supported these findings and some good quotes to support what we concluded. We also provide confidence intervals around the issue and insight frequency so readers have some idea about the prevalence of an issue in the larger user population.

You might also be interested in

Chapter 1. Introduction

“Science is in danger, and for that reason it is becoming dangerous” -Pierre Bourdieu, Science of Science and Reflexivity

Why an Open Access Textbook on Qualitative Research Methods?

I have been teaching qualitative research methods to both undergraduates and graduate students for many years. Although there are some excellent textbooks out there, they are often costly, and none of them, to my mind, properly introduces qualitative research methods to the beginning student (whether undergraduate or graduate student). In contrast, this open-access textbook is designed as a (free) true introduction to the subject, with helpful, practical pointers on how to conduct research and how to access more advanced instruction.

Textbooks are typically arranged in one of two ways: (1) by technique (each chapter covers one method used in qualitative research); or (2) by process (chapters advance from research design through publication). But both of these approaches are necessary for the beginner student. This textbook will have sections dedicated to the process as well as the techniques of qualitative research. This is a true “comprehensive” book for the beginning student. In addition to covering techniques of data collection and data analysis, it provides a road map of how to get started and how to keep going and where to go for advanced instruction. It covers aspects of research design and research communication as well as methods employed. Along the way, it includes examples from many different disciplines in the social sciences.

The primary goal has been to create a useful, accessible, engaging textbook for use across many disciplines. And, let’s face it. Textbooks can be boring. I hope readers find this to be a little different. I have tried to write in a practical and forthright manner, with many lively examples and references to good and intellectually creative qualitative research. Woven throughout the text are short textual asides (in colored textboxes) by professional (academic) qualitative researchers in various disciplines. These short accounts by practitioners should help inspire students. So, let’s begin!

What is Research?

When we use the word research , what exactly do we mean by that? This is one of those words that everyone thinks they understand, but it is worth beginning this textbook with a short explanation. We use the term to refer to “empirical research,” which is actually a historically specific approach to understanding the world around us. Think about how you know things about the world. [1] You might know your mother loves you because she’s told you she does. Or because that is what “mothers” do by tradition. Or you might know because you’ve looked for evidence that she does, like taking care of you when you are sick or reading to you in bed or working two jobs so you can have the things you need to do OK in life. Maybe it seems churlish to look for evidence; you just take it “on faith” that you are loved.

Only one of the above comes close to what we mean by research. Empirical research is research (investigation) based on evidence. Conclusions can then be drawn from observable data. This observable data can also be “tested” or checked. If the data cannot be tested, that is a good indication that we are not doing research. Note that we can never “prove” conclusively, through observable data, that our mothers love us. We might have some “disconfirming evidence” (that time she didn’t show up to your graduation, for example) that could push you to question an original hypothesis , but no amount of “confirming evidence” will ever allow us to say with 100% certainty, “my mother loves me.” Faith and tradition and authority work differently. Our knowledge can be 100% certain using each of those alternative methods of knowledge, but our certainty in those cases will not be based on facts or evidence.

For many periods of history, those in power have been nervous about “science” because it uses evidence and facts as the primary source of understanding the world, and facts can be at odds with what power or authority or tradition want you to believe. That is why I say that scientific empirical research is a historically specific approach to understand the world. You are in college or university now partly to learn how to engage in this historically specific approach.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in Europe, there was a newfound respect for empirical research, some of which was seriously challenging to the established church. Using observations and testing them, scientists found that the earth was not at the center of the universe, for example, but rather that it was but one planet of many which circled the sun. [2] For the next two centuries, the science of astronomy, physics, biology, and chemistry emerged and became disciplines taught in universities. All used the scientific method of observation and testing to advance knowledge. Knowledge about people , however, and social institutions, however, was still left to faith, tradition, and authority. Historians and philosophers and poets wrote about the human condition, but none of them used research to do so. [3]

It was not until the nineteenth century that “social science” really emerged, using the scientific method (empirical observation) to understand people and social institutions. New fields of sociology, economics, political science, and anthropology emerged. The first sociologists, people like Auguste Comte and Karl Marx, sought specifically to apply the scientific method of research to understand society, Engels famously claiming that Marx had done for the social world what Darwin did for the natural world, tracings its laws of development. Today we tend to take for granted the naturalness of science here, but it is actually a pretty recent and radical development.

To return to the question, “does your mother love you?” Well, this is actually not really how a researcher would frame the question, as it is too specific to your case. It doesn’t tell us much about the world at large, even if it does tell us something about you and your relationship with your mother. A social science researcher might ask, “do mothers love their children?” Or maybe they would be more interested in how this loving relationship might change over time (e.g., “do mothers love their children more now than they did in the 18th century when so many children died before reaching adulthood?”) or perhaps they might be interested in measuring quality of love across cultures or time periods, or even establishing “what love looks like” using the mother/child relationship as a site of exploration. All of these make good research questions because we can use observable data to answer them.

What is Qualitative Research?

“All we know is how to learn. How to study, how to listen, how to talk, how to tell. If we don’t tell the world, we don’t know the world. We’re lost in it, we die.” -Ursula LeGuin, The Telling

At its simplest, qualitative research is research about the social world that does not use numbers in its analyses. All those who fear statistics can breathe a sigh of relief – there are no mathematical formulae or regression models in this book! But this definition is less about what qualitative research can be and more about what it is not. To be honest, any simple statement will fail to capture the power and depth of qualitative research. One way of contrasting qualitative research to quantitative research is to note that the focus of qualitative research is less about explaining and predicting relationships between variables and more about understanding the social world. To use our mother love example, the question about “what love looks like” is a good question for the qualitative researcher while all questions measuring love or comparing incidences of love (both of which require measurement) are good questions for quantitative researchers. Patton writes,

Qualitative data describe. They take us, as readers, into the time and place of the observation so that we know what it was like to have been there. They capture and communicate someone else’s experience of the world in his or her own words. Qualitative data tell a story. ( Patton 2002:47 )

Qualitative researchers are asking different questions about the world than their quantitative colleagues. Even when researchers are employed in “mixed methods” research ( both quantitative and qualitative), they are using different methods to address different questions of the study. I do a lot of research about first-generation and working-college college students. Where a quantitative researcher might ask, how many first-generation college students graduate from college within four years? Or does first-generation college status predict high student debt loads? A qualitative researcher might ask, how does the college experience differ for first-generation college students? What is it like to carry a lot of debt, and how does this impact the ability to complete college on time? Both sets of questions are important, but they can only be answered using specific tools tailored to those questions. For the former, you need large numbers to make adequate comparisons. For the latter, you need to talk to people, find out what they are thinking and feeling, and try to inhabit their shoes for a little while so you can make sense of their experiences and beliefs.

Examples of Qualitative Research

You have probably seen examples of qualitative research before, but you might not have paid particular attention to how they were produced or realized that the accounts you were reading were the result of hours, months, even years of research “in the field.” A good qualitative researcher will present the product of their hours of work in such a way that it seems natural, even obvious, to the reader. Because we are trying to convey what it is like answers, qualitative research is often presented as stories – stories about how people live their lives, go to work, raise their children, interact with one another. In some ways, this can seem like reading particularly insightful novels. But, unlike novels, there are very specific rules and guidelines that qualitative researchers follow to ensure that the “story” they are telling is accurate , a truthful rendition of what life is like for the people being studied. Most of this textbook will be spent conveying those rules and guidelines. Let’s take a look, first, however, at three examples of what the end product looks like. I have chosen these three examples to showcase very different approaches to qualitative research, and I will return to these five examples throughout the book. They were all published as whole books (not chapters or articles), and they are worth the long read, if you have the time. I will also provide some information on how these books came to be and the length of time it takes to get them into book version. It is important you know about this process, and the rest of this textbook will help explain why it takes so long to conduct good qualitative research!

Example 1 : The End Game (ethnography + interviews)

Corey Abramson is a sociologist who teaches at the University of Arizona. In 2015 he published The End Game: How Inequality Shapes our Final Years ( 2015 ). This book was based on the research he did for his dissertation at the University of California-Berkeley in 2012. Actually, the dissertation was completed in 2012 but the work that was produced that took several years. The dissertation was entitled, “This is How We Live, This is How We Die: Social Stratification, Aging, and Health in Urban America” ( 2012 ). You can see how the book version, which was written for a more general audience, has a more engaging sound to it, but that the dissertation version, which is what academic faculty read and evaluate, has a more descriptive title. You can read the title and know that this is a study about aging and health and that the focus is going to be inequality and that the context (place) is going to be “urban America.” It’s a study about “how” people do something – in this case, how they deal with aging and death. This is the very first sentence of the dissertation, “From our first breath in the hospital to the day we die, we live in a society characterized by unequal opportunities for maintaining health and taking care of ourselves when ill. These disparities reflect persistent racial, socio-economic, and gender-based inequalities and contribute to their persistence over time” ( 1 ). What follows is a truthful account of how that is so.

Cory Abramson spent three years conducting his research in four different urban neighborhoods. We call the type of research he conducted “comparative ethnographic” because he designed his study to compare groups of seniors as they went about their everyday business. It’s comparative because he is comparing different groups (based on race, class, gender) and ethnographic because he is studying the culture/way of life of a group. [4] He had an educated guess, rooted in what previous research had shown and what social theory would suggest, that people’s experiences of aging differ by race, class, and gender. So, he set up a research design that would allow him to observe differences. He chose two primarily middle-class (one was racially diverse and the other was predominantly White) and two primarily poor neighborhoods (one was racially diverse and the other was predominantly African American). He hung out in senior centers and other places seniors congregated, watched them as they took the bus to get prescriptions filled, sat in doctor’s offices with them, and listened to their conversations with each other. He also conducted more formal conversations, what we call in-depth interviews, with sixty seniors from each of the four neighborhoods. As with a lot of fieldwork , as he got closer to the people involved, he both expanded and deepened his reach –

By the end of the project, I expanded my pool of general observations to include various settings frequented by seniors: apartment building common rooms, doctors’ offices, emergency rooms, pharmacies, senior centers, bars, parks, corner stores, shopping centers, pool halls, hair salons, coffee shops, and discount stores. Over the course of the three years of fieldwork, I observed hundreds of elders, and developed close relationships with a number of them. ( 2012:10 )

When Abramson rewrote the dissertation for a general audience and published his book in 2015, it got a lot of attention. It is a beautifully written book and it provided insight into a common human experience that we surprisingly know very little about. It won the Outstanding Publication Award by the American Sociological Association Section on Aging and the Life Course and was featured in the New York Times . The book was about aging, and specifically how inequality shapes the aging process, but it was also about much more than that. It helped show how inequality affects people’s everyday lives. For example, by observing the difficulties the poor had in setting up appointments and getting to them using public transportation and then being made to wait to see a doctor, sometimes in standing-room-only situations, when they are unwell, and then being treated dismissively by hospital staff, Abramson allowed readers to feel the material reality of being poor in the US. Comparing these examples with seniors with adequate supplemental insurance who have the resources to hire car services or have others assist them in arranging care when they need it, jolts the reader to understand and appreciate the difference money makes in the lives and circumstances of us all, and in a way that is different than simply reading a statistic (“80% of the poor do not keep regular doctor’s appointments”) does. Qualitative research can reach into spaces and places that often go unexamined and then reports back to the rest of us what it is like in those spaces and places.

Example 2: Racing for Innocence (Interviews + Content Analysis + Fictional Stories)

Jennifer Pierce is a Professor of American Studies at the University of Minnesota. Trained as a sociologist, she has written a number of books about gender, race, and power. Her very first book, Gender Trials: Emotional Lives in Contemporary Law Firms, published in 1995, is a brilliant look at gender dynamics within two law firms. Pierce was a participant observer, working as a paralegal, and she observed how female lawyers and female paralegals struggled to obtain parity with their male colleagues.

Fifteen years later, she reexamined the context of the law firm to include an examination of racial dynamics, particularly how elite white men working in these spaces created and maintained a culture that made it difficult for both female attorneys and attorneys of color to thrive. Her book, Racing for Innocence: Whiteness, Gender, and the Backlash Against Affirmative Action , published in 2012, is an interesting and creative blending of interviews with attorneys, content analyses of popular films during this period, and fictional accounts of racial discrimination and sexual harassment. The law firm she chose to study had come under an affirmative action order and was in the process of implementing equitable policies and programs. She wanted to understand how recipients of white privilege (the elite white male attorneys) come to deny the role they play in reproducing inequality. Through interviews with attorneys who were present both before and during the affirmative action order, she creates a historical record of the “bad behavior” that necessitated new policies and procedures, but also, and more importantly , probed the participants ’ understanding of this behavior. It should come as no surprise that most (but not all) of the white male attorneys saw little need for change, and that almost everyone else had accounts that were different if not sometimes downright harrowing.

I’ve used Pierce’s book in my qualitative research methods courses as an example of an interesting blend of techniques and presentation styles. My students often have a very difficult time with the fictional accounts she includes. But they serve an important communicative purpose here. They are her attempts at presenting “both sides” to an objective reality – something happens (Pierce writes this something so it is very clear what it is), and the two participants to the thing that happened have very different understandings of what this means. By including these stories, Pierce presents one of her key findings – people remember things differently and these different memories tend to support their own ideological positions. I wonder what Pierce would have written had she studied the murder of George Floyd or the storming of the US Capitol on January 6 or any number of other historic events whose observers and participants record very different happenings.

This is not to say that qualitative researchers write fictional accounts. In fact, the use of fiction in our work remains controversial. When used, it must be clearly identified as a presentation device, as Pierce did. I include Racing for Innocence here as an example of the multiple uses of methods and techniques and the way that these work together to produce better understandings by us, the readers, of what Pierce studied. We readers come away with a better grasp of how and why advantaged people understate their own involvement in situations and structures that advantage them. This is normal human behavior , in other words. This case may have been about elite white men in law firms, but the general insights here can be transposed to other settings. Indeed, Pierce argues that more research needs to be done about the role elites play in the reproduction of inequality in the workplace in general.

Example 3: Amplified Advantage (Mixed Methods: Survey Interviews + Focus Groups + Archives)

The final example comes from my own work with college students, particularly the ways in which class background affects the experience of college and outcomes for graduates. I include it here as an example of mixed methods, and for the use of supplementary archival research. I’ve done a lot of research over the years on first-generation, low-income, and working-class college students. I am curious (and skeptical) about the possibility of social mobility today, particularly with the rising cost of college and growing inequality in general. As one of the few people in my family to go to college, I didn’t grow up with a lot of examples of what college was like or how to make the most of it. And when I entered graduate school, I realized with dismay that there were very few people like me there. I worried about becoming too different from my family and friends back home. And I wasn’t at all sure that I would ever be able to pay back the huge load of debt I was taking on. And so I wrote my dissertation and first two books about working-class college students. These books focused on experiences in college and the difficulties of navigating between family and school ( Hurst 2010a, 2012 ). But even after all that research, I kept coming back to wondering if working-class students who made it through college had an equal chance at finding good jobs and happy lives,

What happens to students after college? Do working-class students fare as well as their peers? I knew from my own experience that barriers continued through graduate school and beyond, and that my debtload was higher than that of my peers, constraining some of the choices I made when I graduated. To answer these questions, I designed a study of students attending small liberal arts colleges, the type of college that tried to equalize the experience of students by requiring all students to live on campus and offering small classes with lots of interaction with faculty. These private colleges tend to have more money and resources so they can provide financial aid to low-income students. They also attract some very wealthy students. Because they enroll students across the class spectrum, I would be able to draw comparisons. I ended up spending about four years collecting data, both a survey of more than 2000 students (which formed the basis for quantitative analyses) and qualitative data collection (interviews, focus groups, archival research, and participant observation). This is what we call a “mixed methods” approach because we use both quantitative and qualitative data. The survey gave me a large enough number of students that I could make comparisons of the how many kind, and to be able to say with some authority that there were in fact significant differences in experience and outcome by class (e.g., wealthier students earned more money and had little debt; working-class students often found jobs that were not in their chosen careers and were very affected by debt, upper-middle-class students were more likely to go to graduate school). But the survey analyses could not explain why these differences existed. For that, I needed to talk to people and ask them about their motivations and aspirations. I needed to understand their perceptions of the world, and it is very hard to do this through a survey.

By interviewing students and recent graduates, I was able to discern particular patterns and pathways through college and beyond. Specifically, I identified three versions of gameplay. Upper-middle-class students, whose parents were themselves professionals (academics, lawyers, managers of non-profits), saw college as the first stage of their education and took classes and declared majors that would prepare them for graduate school. They also spent a lot of time building their resumes, taking advantage of opportunities to help professors with their research, or study abroad. This helped them gain admission to highly-ranked graduate schools and interesting jobs in the public sector. In contrast, upper-class students, whose parents were wealthy and more likely to be engaged in business (as CEOs or other high-level directors), prioritized building social capital. They did this by joining fraternities and sororities and playing club sports. This helped them when they graduated as they called on friends and parents of friends to find them well-paying jobs. Finally, low-income, first-generation, and working-class students were often adrift. They took the classes that were recommended to them but without the knowledge of how to connect them to life beyond college. They spent time working and studying rather than partying or building their resumes. All three sets of students thought they were “doing college” the right way, the way that one was supposed to do college. But these three versions of gameplay led to distinct outcomes that advantaged some students over others. I titled my work “Amplified Advantage” to highlight this process.

These three examples, Cory Abramson’s The End Game , Jennifer Peirce’s Racing for Innocence, and my own Amplified Advantage, demonstrate the range of approaches and tools available to the qualitative researcher. They also help explain why qualitative research is so important. Numbers can tell us some things about the world, but they cannot get at the hearts and minds, motivations and beliefs of the people who make up the social worlds we inhabit. For that, we need tools that allow us to listen and make sense of what people tell us and show us. That is what good qualitative research offers us.

How Is This Book Organized?

This textbook is organized as a comprehensive introduction to the use of qualitative research methods. The first half covers general topics (e.g., approaches to qualitative research, ethics) and research design (necessary steps for building a successful qualitative research study). The second half reviews various data collection and data analysis techniques. Of course, building a successful qualitative research study requires some knowledge of data collection and data analysis so the chapters in the first half and the chapters in the second half should be read in conversation with each other. That said, each chapter can be read on its own for assistance with a particular narrow topic. In addition to the chapters, a helpful glossary can be found in the back of the book. Rummage around in the text as needed.

Chapter Descriptions

Chapter 2 provides an overview of the Research Design Process. How does one begin a study? What is an appropriate research question? How is the study to be done – with what methods ? Involving what people and sites? Although qualitative research studies can and often do change and develop over the course of data collection, it is important to have a good idea of what the aims and goals of your study are at the outset and a good plan of how to achieve those aims and goals. Chapter 2 provides a road map of the process.

Chapter 3 describes and explains various ways of knowing the (social) world. What is it possible for us to know about how other people think or why they behave the way they do? What does it mean to say something is a “fact” or that it is “well-known” and understood? Qualitative researchers are particularly interested in these questions because of the types of research questions we are interested in answering (the how questions rather than the how many questions of quantitative research). Qualitative researchers have adopted various epistemological approaches. Chapter 3 will explore these approaches, highlighting interpretivist approaches that acknowledge the subjective aspect of reality – in other words, reality and knowledge are not objective but rather influenced by (interpreted through) people.

Chapter 4 focuses on the practical matter of developing a research question and finding the right approach to data collection. In any given study (think of Cory Abramson’s study of aging, for example), there may be years of collected data, thousands of observations , hundreds of pages of notes to read and review and make sense of. If all you had was a general interest area (“aging”), it would be very difficult, nearly impossible, to make sense of all of that data. The research question provides a helpful lens to refine and clarify (and simplify) everything you find and collect. For that reason, it is important to pull out that lens (articulate the research question) before you get started. In the case of the aging study, Cory Abramson was interested in how inequalities affected understandings and responses to aging. It is for this reason he designed a study that would allow him to compare different groups of seniors (some middle-class, some poor). Inevitably, he saw much more in the three years in the field than what made it into his book (or dissertation), but he was able to narrow down the complexity of the social world to provide us with this rich account linked to the original research question. Developing a good research question is thus crucial to effective design and a successful outcome. Chapter 4 will provide pointers on how to do this. Chapter 4 also provides an overview of general approaches taken to doing qualitative research and various “traditions of inquiry.”

Chapter 5 explores sampling . After you have developed a research question and have a general idea of how you will collect data (Observations? Interviews?), how do you go about actually finding people and sites to study? Although there is no “correct number” of people to interview , the sample should follow the research question and research design. Unlike quantitative research, qualitative research involves nonprobability sampling. Chapter 5 explains why this is so and what qualities instead make a good sample for qualitative research.

Chapter 6 addresses the importance of reflexivity in qualitative research. Related to epistemological issues of how we know anything about the social world, qualitative researchers understand that we the researchers can never be truly neutral or outside the study we are conducting. As observers, we see things that make sense to us and may entirely miss what is either too obvious to note or too different to comprehend. As interviewers, as much as we would like to ask questions neutrally and remain in the background, interviews are a form of conversation, and the persons we interview are responding to us . Therefore, it is important to reflect upon our social positions and the knowledges and expectations we bring to our work and to work through any blind spots that we may have. Chapter 6 provides some examples of reflexivity in practice and exercises for thinking through one’s own biases.

Chapter 7 is a very important chapter and should not be overlooked. As a practical matter, it should also be read closely with chapters 6 and 8. Because qualitative researchers deal with people and the social world, it is imperative they develop and adhere to a strong ethical code for conducting research in a way that does not harm. There are legal requirements and guidelines for doing so (see chapter 8), but these requirements should not be considered synonymous with the ethical code required of us. Each researcher must constantly interrogate every aspect of their research, from research question to design to sample through analysis and presentation, to ensure that a minimum of harm (ideally, zero harm) is caused. Because each research project is unique, the standards of care for each study are unique. Part of being a professional researcher is carrying this code in one’s heart, being constantly attentive to what is required under particular circumstances. Chapter 7 provides various research scenarios and asks readers to weigh in on the suitability and appropriateness of the research. If done in a class setting, it will become obvious fairly quickly that there are often no absolutely correct answers, as different people find different aspects of the scenarios of greatest importance. Minimizing the harm in one area may require possible harm in another. Being attentive to all the ethical aspects of one’s research and making the best judgments one can, clearly and consciously, is an integral part of being a good researcher.

Chapter 8 , best to be read in conjunction with chapter 7, explains the role and importance of Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) . Under federal guidelines, an IRB is an appropriately constituted group that has been formally designated to review and monitor research involving human subjects . Every institution that receives funding from the federal government has an IRB. IRBs have the authority to approve, require modifications to (to secure approval), or disapprove research. This group review serves an important role in the protection of the rights and welfare of human research subjects. Chapter 8 reviews the history of IRBs and the work they do but also argues that IRBs’ review of qualitative research is often both over-inclusive and under-inclusive. Some aspects of qualitative research are not well understood by IRBs, given that they were developed to prevent abuses in biomedical research. Thus, it is important not to rely on IRBs to identify all the potential ethical issues that emerge in our research (see chapter 7).

Chapter 9 provides help for getting started on formulating a research question based on gaps in the pre-existing literature. Research is conducted as part of a community, even if particular studies are done by single individuals (or small teams). What any of us finds and reports back becomes part of a much larger body of knowledge. Thus, it is important that we look at the larger body of knowledge before we actually start our bit to see how we can best contribute. When I first began interviewing working-class college students, there was only one other similar study I could find, and it hadn’t been published (it was a dissertation of students from poor backgrounds). But there had been a lot published by professors who had grown up working class and made it through college despite the odds. These accounts by “working-class academics” became an important inspiration for my study and helped me frame the questions I asked the students I interviewed. Chapter 9 will provide some pointers on how to search for relevant literature and how to use this to refine your research question.

Chapter 10 serves as a bridge between the two parts of the textbook, by introducing techniques of data collection. Qualitative research is often characterized by the form of data collection – for example, an ethnographic study is one that employs primarily observational data collection for the purpose of documenting and presenting a particular culture or ethnos. Techniques can be effectively combined, depending on the research question and the aims and goals of the study. Chapter 10 provides a general overview of all the various techniques and how they can be combined.

The second part of the textbook moves into the doing part of qualitative research once the research question has been articulated and the study designed. Chapters 11 through 17 cover various data collection techniques and approaches. Chapters 18 and 19 provide a very simple overview of basic data analysis. Chapter 20 covers communication of the data to various audiences, and in various formats.

Chapter 11 begins our overview of data collection techniques with a focus on interviewing , the true heart of qualitative research. This technique can serve as the primary and exclusive form of data collection, or it can be used to supplement other forms (observation, archival). An interview is distinct from a survey, where questions are asked in a specific order and often with a range of predetermined responses available. Interviews can be conversational and unstructured or, more conventionally, semistructured , where a general set of interview questions “guides” the conversation. Chapter 11 covers the basics of interviews: how to create interview guides, how many people to interview, where to conduct the interview, what to watch out for (how to prepare against things going wrong), and how to get the most out of your interviews.

Chapter 12 covers an important variant of interviewing, the focus group. Focus groups are semistructured interviews with a group of people moderated by a facilitator (the researcher or researcher’s assistant). Focus groups explicitly use group interaction to assist in the data collection. They are best used to collect data on a specific topic that is non-personal and shared among the group. For example, asking a group of college students about a common experience such as taking classes by remote delivery during the pandemic year of 2020. Chapter 12 covers the basics of focus groups: when to use them, how to create interview guides for them, and how to run them effectively.

Chapter 13 moves away from interviewing to the second major form of data collection unique to qualitative researchers – observation . Qualitative research that employs observation can best be understood as falling on a continuum of “fly on the wall” observation (e.g., observing how strangers interact in a doctor’s waiting room) to “participant” observation, where the researcher is also an active participant of the activity being observed. For example, an activist in the Black Lives Matter movement might want to study the movement, using her inside position to gain access to observe key meetings and interactions. Chapter 13 covers the basics of participant observation studies: advantages and disadvantages, gaining access, ethical concerns related to insider/outsider status and entanglement, and recording techniques.

Chapter 14 takes a closer look at “deep ethnography” – immersion in the field of a particularly long duration for the purpose of gaining a deeper understanding and appreciation of a particular culture or social world. Clifford Geertz called this “deep hanging out.” Whereas participant observation is often combined with semistructured interview techniques, deep ethnography’s commitment to “living the life” or experiencing the situation as it really is demands more conversational and natural interactions with people. These interactions and conversations may take place over months or even years. As can be expected, there are some costs to this technique, as well as some very large rewards when done competently. Chapter 14 provides some examples of deep ethnographies that will inspire some beginning researchers and intimidate others.

Chapter 15 moves in the opposite direction of deep ethnography, a technique that is the least positivist of all those discussed here, to mixed methods , a set of techniques that is arguably the most positivist . A mixed methods approach combines both qualitative data collection and quantitative data collection, commonly by combining a survey that is analyzed statistically (e.g., cross-tabs or regression analyses of large number probability samples) with semi-structured interviews. Although it is somewhat unconventional to discuss mixed methods in textbooks on qualitative research, I think it is important to recognize this often-employed approach here. There are several advantages and some disadvantages to taking this route. Chapter 16 will describe those advantages and disadvantages and provide some particular guidance on how to design a mixed methods study for maximum effectiveness.

Chapter 16 covers data collection that does not involve live human subjects at all – archival and historical research (chapter 17 will also cover data that does not involve interacting with human subjects). Sometimes people are unavailable to us, either because they do not wish to be interviewed or observed (as is the case with many “elites”) or because they are too far away, in both place and time. Fortunately, humans leave many traces and we can often answer questions we have by examining those traces. Special collections and archives can be goldmines for social science research. This chapter will explain how to access these places, for what purposes, and how to begin to make sense of what you find.

Chapter 17 covers another data collection area that does not involve face-to-face interaction with humans: content analysis . Although content analysis may be understood more properly as a data analysis technique, the term is often used for the entire approach, which will be the case here. Content analysis involves interpreting meaning from a body of text. This body of text might be something found in historical records (see chapter 16) or something collected by the researcher, as in the case of comment posts on a popular blog post. I once used the stories told by student loan debtors on the website studentloanjustice.org as the content I analyzed. Content analysis is particularly useful when attempting to define and understand prevalent stories or communication about a topic of interest. In other words, when we are less interested in what particular people (our defined sample) are doing or believing and more interested in what general narratives exist about a particular topic or issue. This chapter will explore different approaches to content analysis and provide helpful tips on how to collect data, how to turn that data into codes for analysis, and how to go about presenting what is found through analysis.

Where chapter 17 has pushed us towards data analysis, chapters 18 and 19 are all about what to do with the data collected, whether that data be in the form of interview transcripts or fieldnotes from observations. Chapter 18 introduces the basics of coding , the iterative process of assigning meaning to the data in order to both simplify and identify patterns. What is a code and how does it work? What are the different ways of coding data, and when should you use them? What is a codebook, and why do you need one? What does the process of data analysis look like?

Chapter 19 goes further into detail on codes and how to use them, particularly the later stages of coding in which our codes are refined, simplified, combined, and organized. These later rounds of coding are essential to getting the most out of the data we’ve collected. As students are often overwhelmed with the amount of data (a corpus of interview transcripts typically runs into the hundreds of pages; fieldnotes can easily top that), this chapter will also address time management and provide suggestions for dealing with chaos and reminders that feeling overwhelmed at the analysis stage is part of the process. By the end of the chapter, you should understand how “findings” are actually found.

The book concludes with a chapter dedicated to the effective presentation of data results. Chapter 20 covers the many ways that researchers communicate their studies to various audiences (academic, personal, political), what elements must be included in these various publications, and the hallmarks of excellent qualitative research that various audiences will be expecting. Because qualitative researchers are motivated by understanding and conveying meaning , effective communication is not only an essential skill but a fundamental facet of the entire research project. Ethnographers must be able to convey a certain sense of verisimilitude , the appearance of true reality. Those employing interviews must faithfully depict the key meanings of the people they interviewed in a way that rings true to those people, even if the end result surprises them. And all researchers must strive for clarity in their publications so that various audiences can understand what was found and why it is important.

The book concludes with a short chapter ( chapter 21 ) discussing the value of qualitative research. At the very end of this book, you will find a glossary of terms. I recommend you make frequent use of the glossary and add to each entry as you find examples. Although the entries are meant to be simple and clear, you may also want to paraphrase the definition—make it “make sense” to you, in other words. In addition to the standard reference list (all works cited here), you will find various recommendations for further reading at the end of many chapters. Some of these recommendations will be examples of excellent qualitative research, indicated with an asterisk (*) at the end of the entry. As they say, a picture is worth a thousand words. A good example of qualitative research can teach you more about conducting research than any textbook can (this one included). I highly recommend you select one to three examples from these lists and read them along with the textbook.

A final note on the choice of examples – you will note that many of the examples used in the text come from research on college students. This is for two reasons. First, as most of my research falls in this area, I am most familiar with this literature and have contacts with those who do research here and can call upon them to share their stories with you. Second, and more importantly, my hope is that this textbook reaches a wide audience of beginning researchers who study widely and deeply across the range of what can be known about the social world (from marine resources management to public policy to nursing to political science to sexuality studies and beyond). It is sometimes difficult to find examples that speak to all those research interests, however. A focus on college students is something that all readers can understand and, hopefully, appreciate, as we are all now or have been at some point a college student.

Recommended Reading: Other Qualitative Research Textbooks

I’ve included a brief list of some of my favorite qualitative research textbooks and guidebooks if you need more than what you will find in this introductory text. For each, I’ve also indicated if these are for “beginning” or “advanced” (graduate-level) readers. Many of these books have several editions that do not significantly vary; the edition recommended is merely the edition I have used in teaching and to whose page numbers any specific references made in the text agree.

Barbour, Rosaline. 2014. Introducing Qualitative Research: A Student’s Guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. A good introduction to qualitative research, with abundant examples (often from the discipline of health care) and clear definitions. Includes quick summaries at the ends of each chapter. However, some US students might find the British context distracting and can be a bit advanced in some places. Beginning .

Bloomberg, Linda Dale, and Marie F. Volpe. 2012. Completing Your Qualitative Dissertation . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Specifically designed to guide graduate students through the research process. Advanced .

Creswell, John W., and Cheryl Poth. 2018 Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Traditions . 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. This is a classic and one of the go-to books I used myself as a graduate student. One of the best things about this text is its clear presentation of five distinct traditions in qualitative research. Despite the title, this reasonably sized book is about more than research design, including both data analysis and how to write about qualitative research. Advanced .

Lareau, Annette. 2021. Listening to People: A Practical Guide to Interviewing, Participant Observation, Data Analysis, and Writing It All Up . Chicago: University of Chicago Press. A readable and personal account of conducting qualitative research by an eminent sociologist, with a heavy emphasis on the kinds of participant-observation research conducted by the author. Despite its reader-friendliness, this is really a book targeted to graduate students learning the craft. Advanced .

Lune, Howard, and Bruce L. Berg. 2018. 9th edition. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences. Pearson . Although a good introduction to qualitative methods, the authors favor symbolic interactionist and dramaturgical approaches, which limits the appeal primarily to sociologists. Beginning .

Marshall, Catherine, and Gretchen B. Rossman. 2016. 6th edition. Designing Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Very readable and accessible guide to research design by two educational scholars. Although the presentation is sometimes fairly dry, personal vignettes and illustrations enliven the text. Beginning .

Maxwell, Joseph A. 2013. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach . 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. A short and accessible introduction to qualitative research design, particularly helpful for graduate students contemplating theses and dissertations. This has been a standard textbook in my graduate-level courses for years. Advanced .

Patton, Michael Quinn. 2002. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. This is a comprehensive text that served as my “go-to” reference when I was a graduate student. It is particularly helpful for those involved in program evaluation and other forms of evaluation studies and uses examples from a wide range of disciplines. Advanced .

Rubin, Ashley T. 2021. Rocking Qualitative Social Science: An Irreverent Guide to Rigorous Research. Stanford : Stanford University Press. A delightful and personal read. Rubin uses rock climbing as an extended metaphor for learning how to conduct qualitative research. A bit slanted toward ethnographic and archival methods of data collection, with frequent examples from her own studies in criminology. Beginning .

Weis, Lois, and Michelle Fine. 2000. Speed Bumps: A Student-Friendly Guide to Qualitative Research . New York: Teachers College Press. Readable and accessibly written in a quasi-conversational style. Particularly strong in its discussion of ethical issues throughout the qualitative research process. Not comprehensive, however, and very much tied to ethnographic research. Although designed for graduate students, this is a recommended read for students of all levels. Beginning .

Patton’s Ten Suggestions for Doing Qualitative Research

The following ten suggestions were made by Michael Quinn Patton in his massive textbooks Qualitative Research and Evaluations Methods . This book is highly recommended for those of you who want more than an introduction to qualitative methods. It is the book I relied on heavily when I was a graduate student, although it is much easier to “dip into” when necessary than to read through as a whole. Patton is asked for “just one bit of advice” for a graduate student considering using qualitative research methods for their dissertation. Here are his top ten responses, in short form, heavily paraphrased, and with additional comments and emphases from me:

- Make sure that a qualitative approach fits the research question. The following are the kinds of questions that call out for qualitative methods or where qualitative methods are particularly appropriate: questions about people’s experiences or how they make sense of those experiences; studying a person in their natural environment; researching a phenomenon so unknown that it would be impossible to study it with standardized instruments or other forms of quantitative data collection.

- Study qualitative research by going to the original sources for the design and analysis appropriate to the particular approach you want to take (e.g., read Glaser and Straus if you are using grounded theory )

- Find a dissertation adviser who understands or at least who will support your use of qualitative research methods. You are asking for trouble if your entire committee is populated by quantitative researchers, even if they are all very knowledgeable about the subject or focus of your study (maybe even more so if they are!)

- Really work on design. Doing qualitative research effectively takes a lot of planning. Even if things are more flexible than in quantitative research, a good design is absolutely essential when starting out.

- Practice data collection techniques, particularly interviewing and observing. There is definitely a set of learned skills here! Do not expect your first interview to be perfect. You will continue to grow as a researcher the more interviews you conduct, and you will probably come to understand yourself a bit more in the process, too. This is not easy, despite what others who don’t work with qualitative methods may assume (and tell you!)

- Have a plan for analysis before you begin data collection. This is often a requirement in IRB protocols , although you can get away with writing something fairly simple. And even if you are taking an approach, such as grounded theory, that pushes you to remain fairly open-minded during the data collection process, you still want to know what you will be doing with all the data collected – creating a codebook? Writing analytical memos? Comparing cases? Having a plan in hand will also help prevent you from collecting too much extraneous data.

- Be prepared to confront controversies both within the qualitative research community and between qualitative research and quantitative research. Don’t be naïve about this – qualitative research, particularly some approaches, will be derided by many more “positivist” researchers and audiences. For example, is an “n” of 1 really sufficient? Yes! But not everyone will agree.

- Do not make the mistake of using qualitative research methods because someone told you it was easier, or because you are intimidated by the math required of statistical analyses. Qualitative research is difficult in its own way (and many would claim much more time-consuming than quantitative research). Do it because you are convinced it is right for your goals, aims, and research questions.

- Find a good support network. This could be a research mentor, or it could be a group of friends or colleagues who are also using qualitative research, or it could be just someone who will listen to you work through all of the issues you will confront out in the field and during the writing process. Even though qualitative research often involves human subjects, it can be pretty lonely. A lot of times you will feel like you are working without a net. You have to create one for yourself. Take care of yourself.

- And, finally, in the words of Patton, “Prepare to be changed. Looking deeply at other people’s lives will force you to look deeply at yourself.”

- We will actually spend an entire chapter ( chapter 3 ) looking at this question in much more detail! ↵

- Note that this might have been news to Europeans at the time, but many other societies around the world had also come to this conclusion through observation. There is often a tendency to equate “the scientific revolution” with the European world in which it took place, but this is somewhat misleading. ↵

- Historians are a special case here. Historians have scrupulously and rigorously investigated the social world, but not for the purpose of understanding general laws about how things work, which is the point of scientific empirical research. History is often referred to as an idiographic field of study, meaning that it studies things that happened or are happening in themselves and not for general observations or conclusions. ↵

- Don’t worry, we’ll spend more time later in this book unpacking the meaning of ethnography and other terms that are important here. Note the available glossary ↵

An approach to research that is “multimethod in focus, involving an interpretative, naturalistic approach to its subject matter. This means that qualitative researchers study things in their natural settings, attempting to make sense of, or interpret, phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them. Qualitative research involves the studied use and collection of a variety of empirical materials – case study, personal experience, introspective, life story, interview, observational, historical, interactional, and visual texts – that describe routine and problematic moments and meanings in individuals’ lives." ( Denzin and Lincoln 2005:2 ). Contrast with quantitative research .

In contrast to methodology, methods are more simply the practices and tools used to collect and analyze data. Examples of common methods in qualitative research are interviews , observations , and documentary analysis . One’s methodology should connect to one’s choice of methods, of course, but they are distinguishable terms. See also methodology .

A proposed explanation for an observation, phenomenon, or scientific problem that can be tested by further investigation. The positing of a hypothesis is often the first step in quantitative research but not in qualitative research. Even when qualitative researchers offer possible explanations in advance of conducting research, they will tend to not use the word “hypothesis” as it conjures up the kind of positivist research they are not conducting.

The foundational question to be addressed by the research study. This will form the anchor of the research design, collection, and analysis. Note that in qualitative research, the research question may, and probably will, alter or develop during the course of the research.

An approach to research that collects and analyzes numerical data for the purpose of finding patterns and averages, making predictions, testing causal relationships, and generalizing results to wider populations. Contrast with qualitative research .

Data collection that takes place in real-world settings, referred to as “the field;” a key component of much Grounded Theory and ethnographic research. Patton ( 2002 ) calls fieldwork “the central activity of qualitative inquiry” where “‘going into the field’ means having direct and personal contact with people under study in their own environments – getting close to people and situations being studied to personally understand the realities of minutiae of daily life” (48).

The people who are the subjects of a qualitative study. In interview-based studies, they may be the respondents to the interviewer; for purposes of IRBs, they are often referred to as the human subjects of the research.

The branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. For researchers, it is important to recognize and adopt one of the many distinguishing epistemological perspectives as part of our understanding of what questions research can address or fully answer. See, e.g., constructivism , subjectivism, and objectivism .

An approach that refutes the possibility of neutrality in social science research. All research is “guided by a set of beliefs and feelings about the world and how it should be understood and studied” (Denzin and Lincoln 2005: 13). In contrast to positivism , interpretivism recognizes the social constructedness of reality, and researchers adopting this approach focus on capturing interpretations and understandings people have about the world rather than “the world” as it is (which is a chimera).

The cluster of data-collection tools and techniques that involve observing interactions between people, the behaviors, and practices of individuals (sometimes in contrast to what they say about how they act and behave), and cultures in context. Observational methods are the key tools employed by ethnographers and Grounded Theory .

Research based on data collected and analyzed by the research (in contrast to secondary “library” research).

The process of selecting people or other units of analysis to represent a larger population. In quantitative research, this representation is taken quite literally, as statistically representative. In qualitative research, in contrast, sample selection is often made based on potential to generate insight about a particular topic or phenomenon.

A method of data collection in which the researcher asks the participant questions; the answers to these questions are often recorded and transcribed verbatim. There are many different kinds of interviews - see also semistructured interview , structured interview , and unstructured interview .

The specific group of individuals that you will collect data from. Contrast population.

The practice of being conscious of and reflective upon one’s own social location and presence when conducting research. Because qualitative research often requires interaction with live humans, failing to take into account how one’s presence and prior expectations and social location affect the data collected and how analyzed may limit the reliability of the findings. This remains true even when dealing with historical archives and other content. Who we are matters when asking questions about how people experience the world because we, too, are a part of that world.

The science and practice of right conduct; in research, it is also the delineation of moral obligations towards research participants, communities to which we belong, and communities in which we conduct our research.