- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Visual Communication

Introduction, general overviews.

- Visual Methodology

- Anthologies

- Visual Culture

- Iconography, Iconology, and Image Theories

- Technology and the Image

- Spectatorship, Vision, and Theories of Modernity

- Sociology and Anthropology

- Psychology and Visual Perception

- Photographic Representation Theories

- Photographic History

- Film Theories, the Gaze, and Visuality

- Film Semiotics

- Documentary

- Histories of National Cinema, Genre, and Style

- Information Graphics

- Television and Video

- Advertising

- Journalism and Photojournalism

- Political Communication

- Visual Media Technology

- Visual Rhetoric

- Visual Literacy

- Visual Representations of Social Groups

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Activist Media

- Approaches to Multimodal Discourse Analysis

- Celebrity and Public Persona

- Communication Campaigns

- Digital Intimacies

- Digital Literacy

- Documentary and Communication

- Entertainment-Education

- Feminist and Queer Game Studies

- Feminist Journalism

- Food Studies and Communication

- History of Global Media

- International Advertising

- Journalism Ethics

- Mass Communication

- Media Aesthetics

- Media Ecology

- Media Effects

- Media Ethics

- Media Events

- Media Literacy

- Message Characteristics and Persuasion

- Narrative Engagement

- Photojournalism

- Political Advertising

- Political Marketing

- Product Placement

- Resisting Persuasion

- Social Identity Theory and Communication

- Stereotypes

- The Civil Rights Movement and the Media

- Urban Communication

- Video Deficit

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Culture Shock and Communication

- LGBTQ+ Family Communication

- Queerbaiting

- Find more forthcoming titles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Visual Communication by Michael Griffin , Kevin Barnhurst , Robert Craig LAST REVIEWED: 24 July 2013 LAST MODIFIED: 24 July 2013 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756841-0034

The study of visual communication is inherently multidisciplinary, comprising the wide-reaching and voluminous literature of art history and the philosophy of art and aesthetics; the development and use of charts, diagrams, and cartography; the history and theory of graphic design and typography; the history and theory of photography, cinema, and television studies; the perceptual physiology and cognitive psychology of visual apprehension; the impact of new visual technologies (including digitization, multimedia, and virtual realities); the concepts and teaching of visual literacy; and the boundless social and cultural issues surrounding practices of visual representation. Such an eclectic and newly developing field has reached little consensus about canonical texts. Its boundaries remain indistinct. Even the concept of visual imagery is loose, aggregating everything from mental reproductions of perceptions in eidetic imagery, dreams, and memory to the physical creation of pictorial material. Images are the most obvious of the wide-ranging forms of visual communication, which extend beyond “pictures” or icons into realms of abstract symbols, indexical signals, designs, and ideas humans use to communicate experience. The following bibliography focuses on visual elements and images in communication media. It acknowledges literature from other disciplinary traditions that influenced the rise of visual studies, but centers primarily on the developing visual studies literature within communication as a discipline and field.

General overviews of visual representation and visual communication studies are available in encyclopedias of communication and in recent journals of communication and communication yearbook surveys. These include in the Oxford International Encyclopedia of Communications ( Summers 1989 ) and Blackwell International Encyclopedia of Communication ( Griffin 2008 ). Most of the reviews are products of the 2000s, as communication media scholarship came to acknowledge and incorporate visual analysis as a central component of media studies. Summers 1989 reviews the history of scholarly attention to the visual image, Griffin 2001 and Griffin 2008 attempt to trace the multidisciplinary roots of visual scholarship and the eventual convergence of work from the humanities and the social sciences in visual communication studies. Barnhurst, et al. 2004 contributes particularly on the emergence of academic and institutional networks supporting visual studies in communication and media studies departments and professional associations. Jewitt 2008 surveys associated theoretical developments and syntheses.

Barnhurst, Kevin G., Michael Vari, and Ígor Rodríguez. 2004. Mapping visual studies in communication. Journal of Communication 54.4: 616–644.

DOI: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2004.tb02648.x

Charts the main currents and topical categories of the visual communication literature, correlating them with underlying institutional and organizational connections and loci. Assesses the coalescence and formation of visual studies as a disciplinary area within scholarly societies such as the International Communication Association.

Griffin, Michael. 2001. Camera as witness, image as sign: The study of visual communication in communication research. In Communication yearbook . Vol. 24. Edited by William B. Gudykunst, 433–463. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

A historical review of the study of lens-based media representation and the multiple streams of theory and scholarship that have contributed to the emerging field of visual communication studies. Surveys contributions from film studies, the psychology of art and visual representation, semiotics, the anthropology and sociology of visual communication, and mass media studies.

Griffin, Michael. 2008. Visual communication. In International encyclopedia of communication . Vol. 11. Edited by Wolfgang Donsbach, 5304–5316. Oxford: Blackwell.

An overview of the multidisciplinary field of visual studies in communication, with attention to key interdisciplinary and theoretical cross-currents and issues. The entry focuses on the study of media and pictorial forms, still and moving, and the epistemological and political implications of mediated visual representations. Available online by subscription.

Jewitt, Carey. 2008. Visual representation. In International encyclopedia of communication . Vol. 11. Edited by Wolfgang Donsbach, 5319–5325. Oxford: Blackwell.

A brief summary of modernist and postmodernist approaches to the study of the visual that have increasingly conflated “looking,” “seeing,” and “knowing.” Highlights the role of cultural theories that connect visual representation with fundamental questions of reality, ideology and power, as well as procedures of signification and potentials for interpreting meaning. Available online by subscription.

Summers, David. 1989. Visual image. In International encyclopedia of communications . Vol. 4. Edited by Erik Barnouw, 294–305. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

An overview of scholarship on visual images prior to 1990, from ancient uses of images to European art history and the historical relationships between image and reality in pictorial representation. Attempts to specify the conceptual role of the picture plane in defining the visual image.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Communication »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Accounting Communication

- Acculturation Processes and Communication

- Action Assembly Theory

- Action-Implicative Discourse Analysis

- Adherence and Communication

- Adolescence and the Media

- Advertisements, Televised Political

- Advertising, Children and

- Advertising, International

- Advocacy Journalism

- Agenda Setting

- Annenberg, Walter H.

- Apologies and Accounts

- Applied Communication Research Methods

- Argumentation

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) Advertising

- Attitude-Behavior Consistency

- Audience Fragmentation

- Audience Studies

- Authoritarian Societies, Journalism in

- Bakhtin, Mikhail

- Bandwagon Effect

- Baudrillard, Jean

- Blockchain and Communication

- Bourdieu, Pierre

- Brand Equity

- British and Irish Magazine, History of the

- Broadcasting, Public Service

- Capture, Media

- Castells, Manuel

- Civil Rights Movement and the Media, The

- Co-Cultural Theory and Communication

- Codes and Cultural Discourse Analysis

- Cognitive Dissonance

- Collective Memory, Communication and

- Comedic News

- Communication Apprehension

- Communication, Definitions and Concepts of

- Communication History

- Communication Law

- Communication Management

- Communication Networks

- Communication, Philosophy of

- Community Attachment

- Community Journalism

- Community Structure Approach

- Computational Journalism

- Computer-Mediated Communication

- Content Analysis

- Corporate Social Responsibility and Communication

- Crisis Communication

- Critical and Cultural Studies

- Critical Race Theory and Communication

- Cross-tools and Cross-media Effects

- Cultivation

- Cultural and Creative Industries

- Cultural Imperialism Theories

- Cultural Mapping

- Cultural Persuadables

- Cultural Pluralism and Communication

- Cyberpolitics

- Death, Dying, and Communication

- Debates, Televised

- Deliberation

- Developmental Communication

- Diffusion of Innovations

- Digital Divide

- Digital Gender Diversity

- Diplomacy, Public

- Distributed Work, Comunication and

- E-democracy/E-participation

- E-Government

- Elaboration Likelihood Model

- Electronic Word-of-Mouth (eWOM)

- Embedded Coverage

- Entertainment

- Environmental Communication

- Ethnic Media

- Ethnography of Communication

- Experiments

- Families, Multicultural

- Family Communication

- Federal Communications Commission

- Feminist Data Studies

- Feminist Theory

- Focus Groups

- Freedom of the Press

- Friendships, Intercultural

- Gatekeeping

- Gender and the Media

- Global Englishes

- Global Media, History of

- Global Media Organizations

- Glocalization

- Goffman, Erving

- Habermas, Jürgen

- Habituation and Communication

- Health Communication

- Hermeneutic Communication Studies

- Homelessness and Communication

- Hook-Up and Dating Apps

- Hostile Media Effect

- Identification with Media Characters

- Identity, Cultural

- Image Repair Theory

- Implicit Measurement

- Impression Management

- Infographics

- Information and Communication Technology for Development

- Information Management

- Information Overload

- Information Processing

- Infotainment

- Innis, Harold

- Instructional Communication

- Integrated Marketing Communications

- Interactivity

- Intercultural Capital

- Intercultural Communication

- Intercultural Communication, Tourism and

- Intercultural Communication, Worldview in

- Intercultural Competence

- Intercultural Conflict Mediation

- Intercultural Dialogue

- Intercultural New Media

- Intergenerational Communication

- Intergroup Communication

- International Communications

- Interpersonal Communication

- Interpersonal LGBTQ Communication

- Interpretation/Reception

- Interpretive Communities

- Journalism, Accuracy in

- Journalism, Alternative

- Journalism and Trauma

- Journalism, Citizen

- Journalism, Citizen, History of

- Journalism, Interpretive

- Journalism, Peace

- Journalism, Tabloid

- Journalists, Violence against

- Knowledge Gap

- Lazarsfeld, Paul

- Leadership and Communication

- McLuhan, Marshall

- Media Activism

- Media and Time

- Media Convergence

- Media Credibility

- Media Dependency

- Media Economics

- Media Economics, Theories of

- Media, Educational

- Media Exposure Measurement

- Media, Gays and Lesbians in the

- Media Logic

- Media Management

- Media Policy and Governance

- Media Regulation

- Media, Social

- Media Sociology

- Media Systems Theory

- Merton, Robert K.

- Mobile Communication Studies

- Multimodal Discourse Analysis, Approaches to

- Multinational Organizations, Communication and Culture in

- Murdoch, Rupert

- Narrative Persuasion

- Net Neutrality

- News Framing

- News Media Coverage of Women

- NGOs, Communication and

- Online Campaigning

- Open Access

- Organizational Change and Organizational Change Communicat...

- Organizational Communication

- Organizational Communication, Aging and

- Parasocial Theory in Communication

- Participation, Civic/Political

- Participatory Action Research

- Patient-Provider Communication

- Peacebuilding and Communication

- Perceived Realism

- Personalized Communication

- Persuasion and Social Influence

- Persuasion, Resisting

- Political Communication, Normative Analysis of

- Political Economy

- Political Knowledge

- Political Scandals

- Political Socialization

- Polls, Opinion

- Public Interest Communication

- Public Opinion

- Public Relations

- Public Sphere

- Queer Intercultural Communication

- Queer Migration and Digital Media

- Race and Communication

- Racism and Communication

- Radio Studies

- Reality Television

- Reasoned Action Frameworks

- Religion and the Media

- Reporting, Investigative

- Rhetoric and Communication

- Rhetoric and Intercultural Communication

- Rhetoric and Social Movements

- Rhetoric, Religious

- Rhetoric, Visual

- Risk Communication

- Rumor and Communication

- Schramm, Wilbur

- Science Communication

- Scripps, E. W.

- Selective Exposure

- Sense-Making/Sensemaking

- Sesame Street

- Sex in the Media

- Small-Group Communication

- Social Capital

- Social Change

- Social Cognition

- Social Construction

- Social Interaction

- Social Movements

- Social Network Analysis

- Social Protest

- Sports Communication

- Strategic Communication

- Superdiversity

- Surveillance and Communication

- Symbolic Interactionism in Communication

- Synchrony in Intercultural Communication

- Tabloidization

- Telecommunications History/Policy

- Television, Cable

- Textual Analysis and Communication

- Third Culture Kids

- Third-Person Effect

- Time Warner

- Transgender Media Studies

- Transmedia Storytelling

- Two-Step Flow

- United Nations and Communication

- Uses and Gratifications

- Video Games and Communication

- Violence in the Media

- Virtual Reality and Communication

- Visual Communication

- Web Archiving

- Whistleblowing

- Whiteness Theory in Intercultural Communication

- Youth and Media

- Zines and Communication

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.66.14.236]

- 185.66.14.236

Visual Communication and Learning

- Reference work entry

- pp 3411–3414

- Cite this reference work entry

- Ann Marie Barry 2

322 Accesses

Brain-based visual learning ; Emotional and cognitive learning ; Imitative learning ; Media effects ; Social learning ; Visual cognition ; Visual mind

Visual communication may best be thought of as an umbrella concept. It is essentially a horizontal discipline that cuts across a number of separate fields of study and includes understandings based in cognitive neuroscience, art and visual representation, visual semiotics, visual rhetoric, mass communication, image and visualization, visual technologies, critical and cultural studies, and aesthetics. Because of this, crossover theories rather than area-specific theories provide a productive path of study to the discipline as a whole. Visual communication scholars, in fact, continue to debate exactly which areas should be included in any given program of visual communication study.

The idea of visual learning is also problematic. A lifelong developmental process, visual learning has often been seen as the province of...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Damasio, A. (2000). The feeling of what happens . New York: Harvest Books.

Google Scholar

Gazzaniga, M. (1998). The mind’s past . Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gibson, J. J. (1979). The ecological approach to visual perception . Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Horner, V., & Whiten, A. (2005). Causal knowledge and imitation/emulation switching in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and children (Homo sapiens). Animal Cognition, 8 , 164–181.

Iacoboni, M. (2008). Mirroring people: The new science of how we connect with others . New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.

James, W. (1907). Pragmatism: A new name for some old ways of thinking . New York: Longman Green.

Koffka, K. (1935/1963). Principles of gestalt psychology . New York: Harcourt, Brace, and World.

Kohler, W. (1938). Some gestalt problems. In W. D. Ellis (Ed.), A source book of gestalt psychology (pp. 55–70). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

LeDoux, J. (1998). The emotional brain: The mysterious underpinnings of emotional life . New York: Simon & Schuster Touchstone.

Livingston, M. (2002). Vision and art: The biology of seeing . New York: Harry N. Abrams.

Pinker, S. (1997). How the mind works . New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

Wertheimer, M. (1938). The general theoretical situation. In W. D. Ellis (Ed.), A source book of gestalt psychology (pp. 12–16). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Zeki, S. (1999). Inner vision . New York: Oxford University Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Communication, Boston College, 140 Commonwealth Avenue, 02467-3804, Chestnut Hill, MA, USA

Dr. Ann Marie Barry

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ann Marie Barry .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Faculty of Economics and Behavioral Sciences, Department of Education, University of Freiburg, 79085, Freiburg, Germany

Norbert M. Seel

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2012 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Barry, A.M. (2012). Visual Communication and Learning. In: Seel, N.M. (eds) Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_607

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_607

Publisher Name : Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN : 978-1-4419-1427-9

Online ISBN : 978-1-4419-1428-6

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Communication

iResearchNet

Custom Writing Services

Visual communication.

The study of visual communication comprises such wide-reaching and voluminous literatures as art history, the philosophy of art and aesthetics, semiotics, cinema studies, television and mass media studies, the history and theory of photography, the history and theory of graphic design and typography, the study of word–image relationships in literary, aesthetic, and rhetorical theory, the development and use of charts, diagrams, cartography and questions of geographic visualization (images of place and space), the physiology and psychology of visual perception, the impact of new visual technologies (including the impact of digitalization and the construction of “virtual realities”), growing concerns with the concept and/or acquisition of “visual literacy,” and the boundless social and cultural issues embedded in practices of visual representation.

Amid such an eclectic field no consensus has emerged regarding canonical texts. Even the concept of “imagery” itself seems to have no clear boundaries, encompassing concepts of the image that extend from the perceptual process, through the mental reproduction of perceptions in eidetic imagery, dreams, and memory, to the realms of abstract symbols and ideas by which we mentally map experience, and the physical creation of pictures and visual media. Consequently, the study of imagery is as integral to the study of language, cognition, psychoanalysis, and ethology as it is to the study of pictorial or graphic representation.

Social Relevance of the Field

This article notes key themes and theories in this cross-disciplinary area of study. For purposes of manageability the focus is on pictures rather than the broader concept of the visual , and with a bent toward the study of twentieth-century mass communication media rather than the larger history of art and visual representation. The term “picture” is used here in a sense that is similar to the Albertian definition of a picture noted by Alpers: “a framed surface or pane situated at a certain distance from a viewer who looks through it at a second or substitute world” (1983, xix). I do not, however, wish to limit my definition to a strictly Renaissance model of picture-making but rather would include all types of visual image-making that address viewers in a picture-like manner. The choice to concentrate on the pictorial directs the emphasis toward the production and interpretation of communication media and avoids the insurmountable problem of addressing a diffuse and boundless range of the visual. The focus on recent history reflects the concern for contemporary media and cultural environments that is such a prominent part of communication studies.

In this context the study of visual communication as an institutional interest area has grown primarily in response to perceived gaps in the more widely established field of mass communication research. The relationship to mass communication may not be readily apparent, for visual communication study did not emerge within established traditions of mass communication research, nor was it bound by the same theoretical or methodological paradigms. Yet the study of visual communication (as opposed to the study of art, art history, design, or architecture) has been defined in relation to the mechanical reproduction of imagery that has characterized modern mass media (Ivins 1953; Benjamin 1969; Berger 1972).

Those intrigued by the role and influence of visual imagery in mass circulation publications, television, and the entire range of commercial advertising have often been disappointed by the lack of attention given to pictures in established traditions of mass communication research. Prominent strains of mass communication research – public opinion and attitude research, social psychological studies of behavior and cognition, experimental studies of media exposure, marketing research, correlational studies of media effects, content analysis, studies of media uses and gratifications, agenda-setting research, or sociologies of media organizations and media production – have only sparsely and inconsistently incorporated the analysis of visual forms and their role in communication processes. For years content studies of television news were conducted solely from verbal transcripts, and audience studies often documented viewer responses to program stories and characters without attending to the nature of the specific visual presentations of those programs (Griffin 1992b).

Even studies of political communication , where one might expect a keen interest in the role of visual images, focus overwhelmingly on rhetorical strategies, issue framing, and a concern for the tactical effect of linguistic symbols and slogans, and lack a sustained attention to the contributions of the visual. A 1990 survey of political communication literature, for example, found that only five out of more than 600 articles and studies actually examined the concrete visual components of televised election coverage and advertising, and that when the term “image” was used it most often referred to conceptual interpretations of the public ethos of political candidates rather than specific concrete visual attributes of media presentations (Johnston 1990). Consciousness of the importance of visual images in political communication expanded greatly in the wake of the Reagan presidency, when such Reagan advisers as Michael Deaver averred that the control and manipulation of images overpowered anything that the public heard or read (Deaver 1987). Following the 1988 campaign, prominent political rhetoricians, such as Kathleen Hall Jamieson, began for the first time to explicitly call for the visual analysis of political spots and contemporary political discourse (Jamieson 1992).

Against this background the growing interest in visual communication throughout the 1970s and 1980s was often perceived as a corrective response. The increasingly ubiquitous visual appeals of advertising, both commercial and political, and the alarming number of hours most people spent watching television, had certainly made media researchers aware of the potential impact of images and triggered interest in some to include visual analysis in their work. Yet, few examples of research specifically focused on the visual mode could be found in the mass communication literature, and those hoping to pursue such research needed to look beyond the boundaries of communication scholarship for theories, templates, and inspiration.

Often, this meant foraging purposefully among literatures institutionally separated from communications: aesthetics, anthropology, art history, graphic design, electronic and video arts, film theory and history, the philosophy of perception and knowledge, literary theory, linguistics, semiology. Sometimes it meant opening the door to the developments within communications that were more attentive to the impact of images: to feminist scholars, and others, interested in gender portrayals; to those concerned with representations of homosexuality; and to those concerned with the stereotyping of various racial, cultural, and social groups. And sometimes it meant reframing or redefining entrenched areas of professional and technical training: in film and video production, photography and photojournalism, broadcast journalism, typography and publication design.

By the 1980s this trend led to movements within academic communication associations to provide expanded forums for visual communication research presentations. In the International Communication Association (ICA) nondivisional paper sessions were organized around visual communication themes, eventually leading to the establishment of a Visual Communication Interest Group. In the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (AEJMC) attempts were made to encourage the presentation of scholarly research in the Visual Communication Division, a division previously focused almost exclusively on professional training in graphic design and photojournalism, and seen largely as an area of technical support for the primary work of writing and editing. In the Speech Communication Association (SCA) in the US, an interest group on “visual literacy” was formed. These developments have continued to have a bearing on the place of visual communication studies within the larger field of communication research. However, primary sources of new theory and new research have continued to originate from outside these institutional parameters.

History and Theory

The rise of contemporary visual communication studies was, of course, preceded by centuries of thought and writing concerning the arts and the visual image. Yet the last decades of the twentieth century have seen a renewed philosophical concern with the visual that Mitchell (1994), following Rorty’s (1979) notion of “the linguistic turn,” has called “the pictorial turn.” In Picture theory (1994) Mitchell argues, “The simplest way to put this is to say that, in what is often characterized as an age of ‘spectacle’ (Debord), ‘surveillance’ (Foucault), and all-pervasive image-making, we still do not know exactly what pictures are, what their relation to language is, how they operate on observers and on the world, how their history is to be understood, and what is to be done with or about them” (1994, 13). He adds, “while the problem of pictorial representation has always been with us, it presses inescapably now, and with an unprecedented force, on every level of culture, from the most refined philosophical speculations to the most vulgar productions of the mass media” (1994, 16). In this, Mitchell echoes the challenge described by Worth in the early 1970s (Worth 1981). An extensive body of literature explores the ontology and epistemology of photography and the cinema , the foundations of contemporary lens-based media. Writings on photography since the middle of the nineteenth century have continually explored, and revisited, the nature of the photographic image as art vs science, pictorial expression vs mechanical record, trace vs transformation. Meanwhile, the practice of photography has been dogged by the ongoing contradictions between the craft of picturemaking and the status of photographs as “reflections of the real” (Sekula 1975; Brennen & Hardt 1999). Similarly, the extensive literature of film theory , going back at least to the treatises of Lindsay, Munsterberg, Arnheim, and Balazs, has struggled with the nature of cinema and its proper aesthetic and communicational development (Andrew 1976). A wellspring of analytic concepts regarding the composition and juxtaposition of images have been applied to sophisticated analyses of mise-en-scène (the construction of the shot) and montage (the structuring of sequences of shots through editing). The synthesis of realist theories of mise-en-scène, formalist theories of montage, and structural theories of narrative in the work of Jean Mitry (1963–1965), and the subsequent application of linguistically based semiotic theory to cinema by Christian Metz (1974) pushed film analysis into new territories of narrative and syntactical exegesis in the attempt to identify a “language of film.” We are still looking.

Film Studies

An important foundation for the development of visual communication studies, film theory comprises a body of concepts and tools borrowed from the study of art, psychology, sociology, language, and literature. Work in visual communication has often returned to these various sources for new applications to photography, design, electronic imaging, or virtual reality. A central theoretical parameter of debate has involved the distinction between formative and realist theories (Andrew 1976; 1984), but has also involved questions concerning the scope and centrality of narrative, an issue that has preoccupied the philosophy of representation across numerous fields.

Formative film theories treat cinematic presentations as wholly constructed visual expressions, or rhetoric, and seek to build schematic explanations for the semantic and syntactic capacity and operation of the medium. Realist theories argue that there is a natural relationship between life and image. They assert that photographic motion pictures inherently mirror everyday perception and moreover that the goal for filmmakers should be to employ that essential capacity to create the most realistic possible simulations of actual experience. All film students learn about the concepts of film art posited by early formalists such as Munsterberg, Arnheim, Kuleshov, Pudovkin, Eisenstein, and Balazs, and countered by realists such as Bazin and Kracauer. Many aspects of this theoretical opposition have re-emerged repeatedly as visual communication studies have come to encompass parallel issues in television, photojournalism, news, advertising, and most recently digital image creation and manipulation.

The heart of the matter, and arguably the central question of all visual communication study, is the precise status of the image as a copy or analogue . As Andrew writes of the work of Bazin and Mitry, “Bazin spent his life discussing the importance of the ‘snugness’ with which the filmic analogue fits the world, whereas Mitry has spent his life investigating the crucial differences which keep this asymptote forever distinct from the world it runs beside and so faithfully mirrors” (1976, 190). Historically, film and photographic theory and criticism were absorbed with these questions as they pertained to the properties of the image-text itself. As will be discussed at a later point, visual communication studies turned the question toward the manner in which images were utilized and interpreted by media production institutions and viewing audiences.

The key point here, to be revisited throughout this article, is that the study of pictures brought into even greater relief questions of reflection and construction in human representation. And although these issues are not confined to modern visual media, and perhaps are questions that cannot be asked of pictures as if they were a purely visual medium, somehow outside of intertextual contexts, they have become defining issues for visual communication study in an era of constant photographic reproduction when it is so often taken for granted that visual media technologically mimic reality. These issues relate as well to spatial and temporal constructs in literature and the earlier plastic arts, and were raised by writers at least as early as the eighteenth century (Mitchell 1986).

Various technical advances have seemed to provide an inexorable progression toward ever more convincing recreations of the “real world” and have consistently raised the ante on illusion and simulation. Yet film theory has persistently directed attention toward the processes of constructing visual representations, constantly reminding us of the inherent tension between the craft of picture-making and the perception of pictures as records. Against the commonsense assumptions so often made that visual media give us a window on the world with which to witness “reality,” film theory from the beginning has interrogated the ways in which such “windows” are created and structured to shape our view. Even in the practice of documentary film, theorists such as Nichols (1991) identify patterns or “modes” of representational strategy that make each documentary a formal and rhetorical articulation. Writers on still photography, perhaps ironically, followed the development of film theory in fully theorizing the ontology of the photograph, but in the last 50 years have also contributed an extensive literature on the relationship of photo images to their subjects.

The fact that film studies provided an important stock of conceptual tools for the study of pictorial communication of all types was not lost on communication scholars who hoped to better understand the growing prominence of visual mass media in late industrial society. British cultural studies also borrowed freely from film studies (much of it centered around the British Film Institute and its sponsored book and journal publications) and the resulting sensitivity to the culturally constructed nature of visual representation in much cultural studies work made it attractive to visual communication scholars in America. Writings on visual media by British and Australian cultural critics and scholars such as John Berger (1972); Raymond Williams (1974), Laura Mulvey (1989), Judith Williamson (1978), and John Fiske and John Hartley (1978) drew the attention of those tuned into what the British increasingly called “lens theory.”

The influence of this brand of cultural studies on the American scene fueled a nascent interest in semiotic analysis and the interpretation of media texts, and it was not a far leap to imagine the incorporation of visual analysis into studies of representation, meaning, and ideology. An early example of the incorporation of visual analysis in the study of representation and ideology is Stuart Hall’s essay “The determination of news photographs” (1973). In this essay he attempts to apply the cultural and ideological analysis derived from Birmingham Center studies of popular culture to news photographs in order to demonstrate how pictures enhance and frame the ideological positions of accompanying linguistic text. In the mid 1970s the Glasgow University Media Group (1976; 1980) carried out some of the first detailed visual analyses of television news footage in order to expose the ideological nature of BBC reporting on industrial labor disputes. Moreover, the fastgrowing popularity of cultural studies often helped to open up additional curricular space for addressing the nature of visual symbol systems and processes of meaning construction. A convergence of interest in the study of photographically mediated culture was building from several directions, including anthropology, sociology, and the psychology of art.

The Psychology of the Visual: Language and Image

The work of E. H. Gombrich serves to represent the essential themes of this tradition, although its roots lie in the earlier work of Panofsky (1991; 1st pub. 1924) and others. In his highly influential book Art and illusion (1960) Gombrich makes a powerful case for the conventionality of schemes for visual representation. With an art historian’s knowledge of the traditions of western art, and particularly the development of linear perspective, he argues that picture forms of all kinds are conventionally constructed according to learned schemata, not copied from nature. Building from the idea that perceptual gestalts are not necessarily innate but often learned (a concept fully developed in the perceptual research of R. L. Gregory [1970]), Gombrich argued that perceptions of visual representations in art operate by means of gestalts that are culturally based and that, in this sense, pictures are read on the basis of prior knowledge of cultural conventions.

Gombrich develops the metaphor of “reading images” in his article, “The visual image,” written for Scientific American (1972). Here he reiterates the ways in which images are intertwined within cultural systems of language and function and depend upon “code, caption, and context” for understanding. Pictures rarely stand alone, and rarely communicate unambiguously when they do. The mutual support of language and image facilitates memory and interpretation, making visual communication (as separate from artistic expression) possible. Without using the same structuralist paradigm or terminology, Gombrich comes very close to reproducing the semiological notions of icon, index, and symbol in his analysis. Most images seem to combine all three qualities of signification in some measure, although it is most often the iconic prevalence and/or limits of images that preoccupies scholars of the visual, the iconic being that which most clearly distinguishes visual signs from lexical, mathematical, musical, and socio-gestural (Gross 1974).

Although a substantial body of research by perceptual psychologists contradicts Gombrich’s suggestion that visual apprehension is culturally learned – providing evidence instead that many aspects of visual perception derive from a natural, hard-wired set of sensory, neurological, and perceptual processes – the impact of Gombrich’s analysis has still been enormous. His writings provide a strong case against the equation of art and communication, and help to lay a basis for the study of visual communication as distinct from the study of art. They also demonstrate the need to understand the history of art, and the various traditions of depiction and symbolization that have influenced visual practices, before we can hope to explain the role of visual communication in modern media systems.

Together with film theory, semiotics, the social history of art, and anthropological concerns with art and visual representation, the psychology of visual representation has contributed to an eclectic body of theory and research on which communications scholars began to draw for conceptualizing approaches to visual communication analysis.

Other strains in the history of art and aesthetics that have contributed much to contemporary thinking about visual communication include the social history of art and aesthetic theories regarding the relationship between pictures and language. The social history of art, particularly in the work of writers such as Michael Baxandall (1972) and Svetlana Alpers (1983), offers models for investigating relationships between the production of images and the social contexts of their sponsorship, use, and interpretation. Alpers has explored the relation between picture-making and description, from the ekphrastic tradition of the Sophists in which they used the subject matter of paintings as jumpingoff points for discursive monologues and storytelling, a model, she argues, for Vasari’s famous descriptions of Renaissance paintings (Alpers 1960), to the seventeenth-century tradition of Dutch painting, when northern European painters broke with the narrative tradition of Italian painting to create a new “descriptive pictorial mode.”

Baxandall’s (1972) study of painting and experience in fifteenth-century Italy provides an example of what reviewer Larry Gross (1974) called a historical “ethnography of visual communication,” demonstrating how patronage and contractual obligations, on the one hand, and viewer expectations and understandings of convention, on the other, combined to make of painting a currency of social communication. Becker’s Art worlds (1982) applies a similar approach to twentieth-century social worlds of artistic production with specific attention paid to painting and photography, among other arts. Gross’s On the margin of art worlds (1995) follows in this vein with a collection of studies explicitly devoted to the social definitions and boundaries that have emerged among worlds of visual art and communication.

Related to these extra-textual studies of visual communication practice and meaning is a long history of attention to the intertextual relationships between word and image . Whether in studies of the relationship between religious painting and scripture, pictures and narrative, or in attempts to pursue the study of iconology (the general field of images and their relation to discourse), the existence of pictures within larger multi-textual contexts has led to several rich traditions of scholarship (Panofsky 1939; Mitchell 1986; 1994). Here the dispersed boundaries of visual communication studies become especially apparent. Its coherence as a field diffuses into myriad strains of philosophy, literary theory, linguistics, cultural theory, art history, and media studies – the concerns with the subject/spectator (the look, the gaze, the glance, observation, surveillance, and visual pleasure) and with the interpreter/reader (decipherment, decoding, visual experience, “visual literacy,” or “visual culture”) running through numerous disciplines and theories.

The Sociology and Anthropology of Visual Communication

This tradition of research emerged in the 1960s and 1970s in the US largely in association with the work of Sol Worth, Jay Ruby, Richard Chalfen, Larry Gross, Howard S. Becker, and their students. It was carried forward by scholars particularly interested in the cultural codes and social contexts of image-making within particular communities, sub-cultures, and social groups. This movement was influenced by work in the psychology of art and representation, film theory, semiotics, and the social history of art. For example, attempts to assess and compare the types of psychological schemata suggested by Gombrich in image-making and image interpretation across different cultures suggested that processes of visual communication were not universal and needed to be explored within specific socio-cultural settings.

The anthropology of visual communication was also heavily influenced by new approaches to the study of linguistics, not only by structuralist tendencies and the semiological theories and methods that structural linguistics engendered, but in particular by the rise of sociolinguistics (Hymes 1964). Sociolinguists had begun to examine the differing uses of language across sub-cultures, social classes, and ethnic groups, and provided exemplars for the similar study of visual “languages” in varying social contexts. A key figure in adapting these influences to the study of visual communication was Sol Worth. The collection of his writings, Studying visual communication (1981), edited posthumously by his colleague and co-author Larry Gross, is perhaps the best starting point for those interested in gaining a sense of the origins of the field of visual communication research. “The central thread that runs through Worth’s research and writings is the question of how meaning is communicated through visual images” (Gross 1981).

This interest led to the landmark Navajo Filmmakers Project, in which Worth collaborated with anthropologist John Adair and graduate assistant Richard Chalfen to study film made not as records about Navajo culture, but as examples of Navajo culture, reflecting the value systems, coding patterns, and cognitive processes of the maker (Worth & Adair 1972). The Navajo films (now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York), and the published results of the project, were praised by such commentators as Margaret Mead as a “breakthrough in cross-cultural communications” (Mead 1977, 67).

The critique of documentary practice led Worth to propose “a shift from visual anthropology to the anthropology of visual communication” (1981) suggesting the need to abandon taken-for-granted assumptions about the capacity of film and photography to portray culture from the outside. Instead, he suggested, it would be better to study the forms and uses given to visual media by the members of different cultures and social groups themselves. Worth vigorously distinguished this work from traditional “visual anthropology,” much of which he considered naïve and unreflective in its reliance on photographic records about culture, and increasingly became identified with the alternative of studying all forms of visual communication as examples of culture, to be analyzed for the patterns of culture that they reveal.

Interdisciplinary Cross-Currents

Worth’s idea of an “anthropology of visual communication” dovetailed with the work of numerous students, colleagues, and scholars working along cognate trajectories, leaving a fruitful legacy. These included, among others: ground-breaking studies of family photography and home moviemaking (Chalfen 1987); explorations of the nature and limits of documentary representation (Ruby 2000); the study of pictorial perception, learning, and interpretation (Worth & Gross 1974; Messaris & Gross 1977); children’s socialization to visual forms (Griffin 1985); the nature of visual rhetoric and persuasion and questions of visual literacy (Messaris 1994; 1997); institutionalized standards and practices in picture-making and use; the study of social worlds of visual production and legitimization – from art to advertising, to news (Tuchman 1978; Rosenblum 1978; Schwartz & Griffin, 1987); and the ethics of visual representation (Gross et al. 1988; 2003).

It also led to the establishment of the first scholarly journal in the US devoted specifically to visual communication research, Studies in Visual Communication . The journal published contributions from a wide range of disciplinary sources, representing the new critical histories of photography, work on the visual languages of science and cartography, research on caricature and political cartoons, essays on public art, new interpretations of the documentary tradition in photography and film, and a greater emphasis on television and media events. The pioneering study Gender advertisements (1976) by Erving Goffman was first published as a special issue of Studies in Visual Communication , and for a time the journal provided impressive evidence that scholarly attention to visual imagery was growing across the social sciences and humanities. An attempt to extend this attention led directly to the organization of a Visual Communication Interest Group in the International Communication Association, which in 2004 became the Visual Communication Studies Division of the ICA.

By the 1980s traditional notions of visual media were being re-evaluated across programs of art, communications, and journalism. A few journalism schools attempted to recast their photojournalism and publication graphics tracks into more integrated and multidisciplinary visual communication curricula. Communication scholars increasingly pointed out that, given the pervasively visual nature of contemporary mass media, it was no longer tenable to study mass communication separately from visual communication (Griffin 1992a), and that even a medium such as the newspaper needs to be understood as an inherently visual phenomenon (Barnhurst 1994).

Key Issues and Current Trends

The key issues for visual communication in the new millennium are surprisingly similar to those of 30 years ago. The major difference is that greater attention is being paid to these issues within communications scholarship itself, and the application of these ideas is being made across an even greater diversity of media forms and technologies, including digital ones. Recent attempts to examine the state of visual research, and its application to new media, remind us that the kinds of questions asked by Sol Worth decades ago have not been settled (Manovich 2001; Elkins 2003). We are still exploring “how, and what kinds of things, pictures mean.” And “how the way that pictures mean differs from the way such things as ‘words’ or ‘languages’ mean” (Worth 1981, 162). Barthes wrote that photography, “by virtue of its absolutely analogical nature, seems to constitute a message without a code” (1977, 42–43). This quality not only lends itself to the proliferation of pseudo-events, and the ever new developments and consequences of virtual realities, but makes of images a kind of automatic evidence that is rarely questioned. Therefore, the ontological questions regarding the status of images as simulated reality blur together with epistemological questions concerning the validity of images as evidence.

These compounded theoretical issues continually re-emerge in nearly every area of visual communication studies. A great, but still largely unmet challenge for visual communication scholars is to scan, chart, and interrogate the various levels at which images seem to operate: as evidence in visual rhetoric, as simulated reality bolstering and legitimizing the presence and status of media operations themselves, as abstract symbols and textual indices, and as “stylistic excess” – the self-conscious performance of style (Caldwell 1995). Visual style itself, apart from content-related denotation, connotation, and allusion, can be a powerful index of culture – sub-cultures, professional cultures, political cultures, commercial fashion. Initial forays suggest that scrutinizing visual forms of simulated “reality” tell us a great deal about the nature of media rhetoric, the limits of veridical representation, and the self-conscious performance of style in entertainment, advertising, and news. These issues are perhaps more significant than ever for the processes of “remediation” that characterize “new” digital media and the emphases on “transparent immediacy” and “hypermediacy” that distinguish digital visualization (Bolter & Grusin 1999).

Visual communication research, more than anything else, has been a path into the examination of the specific forms of our increasingly visual media surround. In the early stages of mass communication research Lang & Lang reported on “The unique perspective of television and its effect” (1953). The heart of the study was their comparison of the televised coverage of Chicago’s MacArthur Day parade with the reported observations and experiences of informants on the scene, a comparison that found the representation of the parade on television, the “TV screen reality,” to be very different from, even contradictory of, the “reality” seen and experienced by those attending the event. They concluded that television’s need to create a coherent presentational structure from separate, fragmented, and often only indirectly related scenes and activities resulted in a “televisual perspective” or televisual form specific to the nature and workings of that medium. Visual communication research is often distinctive precisely for its attention to forms of representation, forms created by the intersection of aesthetic and pictorial traditions, shifting industrial uses of visual media, and evolving media technologies. To many it seemed that the movement toward visual communication studies in fact best fulfilled cultural studies pioneer Raymond Williams’s exhortation to focus attention on the forms and practices of media production and representation (Williams 1974).

This is not a return to a McLuhanesque essentialism regarding media technology. Rather it is a recognition (following Raymond Williams) that the historically and culturally specific forms of representation that have evolved in particular industrial and commercial systems inexorably shape and delimit the nature of media discourse. This is an issue of particular concern to visual communication researchers as we proceed into an era of increasingly convincing virtual realism on the one hand, and an increasingly systemic textualization of images in cyberspace on the other. More and more visual practices are moving away from the ideal that visual media can and should explore and reveal our social and natural environment and toward self-contained visual lexicons that reduce all visual elements to characters in digital texts. For both economic and technological reasons digital designers and television producers increasingly create “virtual worlds of excessive videographics” in place of the realist style of conventional production techniques (Caldwell 1995). It is as if we seek to follow French structuralist philosophy to its logical conclusion, taming the potential autonomy and power of images and making them subservient to structural linguistic interpretation (Jay 1993). It is not just what we can do with new digital technologies of manipulation but to what purposes we seek to use the production of images in a “post-photographic age.”

Finally, in that emerging condition often referred to as the “global media environment” visual images have become a new sort of transnational cultural currency. Not the “universal language” that promoters such as Eastman Kodak Company claimed for photography earlier in the century, but a currency of media control and power, indices of the predominant cultural visions of predominant media industries.

References:

- Alpers, S. (1960). Ekphrasis and Aesthetic Attitudes in Vasari’s Lives. Journal of the WarburgCourtauld Institute , 23, 190–215.

- Alpers, S. (1983). The art of describing: Dutch art in the seventeenth century . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Andrew, D. (1976). The major film theories . New York: Oxford University Press.

- Andrew, D. (1984). Concepts in film theory . New York: Oxford University Press.

- Barnhurst, K. (1994). Seeing the newspaper . New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Barthes, R. (1977). The rhetoric of the image. In Image-Music-Text . New York: Noonday Press, pp. 32–51.

- Baxandall, M. (1972). Painting and experience in fifteenth century Italy . New York: Oxford University Press.

- Becker, H. S. (1982). Art worlds . Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Benjamin, W. (1969). The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction. In Illuminations (trans. H. Zohn). New York: Schocken, pp. 221–264. (Original work published 1936). Berger, J. (1972). Ways of seeing . New York: Penguin.

- Bolter, J. D., & Grusin, R. (1999). Remediation: Understanding new media . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Brennen, B., & Hardt, H. (eds.) (1999). Picturing the past: Media, history and photography . Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Caldwell, J. T. (1995). Televisuality: Style, crisis, and authority in American television . New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Chalfen, R. (1987). Snapshot versions of life . Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University Popular Press.

- Deaver, M. (1987). Behind the scenes . New York: William Morrow.

- Elkins, J. (2003). Visual studies: A skeptical introduction . New York and London: Routledge.

- Fiske, J., & Hartley, J. (1978). Reading television . London: Methuen.

- Glasgow University Media Group (1976). Bad news . London: Routledge.

- Glasgow University Media Group (1980). More bad news . London: Routledge.

- Goffman, E. (1976). Gender advertisements. Studies in the Anthropology of Visual Communication (special issue), 3(2). (Republished as Gender advertisements , New York: Harper and Row, 1979).

- Gombrich, E. H. (1960). Art and illusion: A study in the psychology of pictorial representation . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Gombrich, E. H. (1972). The visual image. Scientific American , 227(3), 82–96.

- Gregory, R. L. (1970). The intelligent eye . New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Griffin, M. (1985). What young filmmakers learn from television: A study of structure in films made by children. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media , 29(1), 79–92.

- Griffin, M. (ed.) (1992a). Visual communication studies in mass media research, Parts I and II. Communication (special double issue), 13(2/3).

- Griffin, M. (1992b). Looking at TV news: Strategies for research. Communication 13(2), 121–141.

- Gross, L. (1974). Modes of communication and the acquisition of symbolic competence. In D. R. Olson (ed.), Media and symbols: The forms of expression, communication, and education . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 56–80.

- Gross, L. (1981). Introduction. In S. Worth, Studying visual communication . Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Gross, L. (ed.) (1995). On the margins of art worlds . Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Gross, L., Katz, J. S., & Ruby, J. (eds.) (1988). Image ethics . New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gross, L., Katz, J. S., & Ruby, J. (eds.) (2003). Image ethics in a digital age . Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Hall, S. (1973). The determinations of news photographs. In S. Cohen & J. Young (eds.), The manufacture of news: Social problems, deviance and the mass media . Beverly Hills, CA: Constable/ Sage, pp. 226–243.

- Hymes, D. (1964). Toward ethnographies of communication. In J. J. Gumpert & D. Hymes (eds.), The ethnography of communication . Washington, DC: American Anthropological Association.

- Ivins, W., Jr. (1953). Prints and visual communication . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Jamieson, K. H. (1992). Dirty politics: Deception, distraction, and democracy . New York: Oxford University Press.

- Jay, M. (1993). Downcast eyes: The denigration of vision in twentieth-century French thought . Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Johnston, A. (1990). Trends in political communication: A selective review of research in the 1980s. In D. L. Swanson & D. Nimmo (eds.), New directions in political communication . Newbury Park, CA: Sage, pp. 329–362.

- Lang, K., & Lang, G. (1953). The unique perspective of television and its effect: A pilot study. American Sociological Review , 18(1), 3–12.

- Manovich, L. (2001). The language of new media . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Mead, M. (1977). The contribution of Sol Worth to anthropology. Studies in the Anthropology of Visual Communication , 4(4), 67.

- Messaris, P. (1994). Visual literacy: Image, mind, reality . Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Messaris, P. (1997). Visual persuasion: The role of images in advertising . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Messaris, P., & Gross, L. (1977). Interpretations of a photographic narrative by viewers in four age groups. Studies in the Anthropology of Visual Communication , 4(2), 99–111.

- Metz, C. (1974). Film language . New York: Oxford University Press.

- Mitchell, W. J. T. (1986). Iconology: Image, text, ideology . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Mitchell, W. J. T. (1994). Picture theory . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Mitry, J. (1963–1965). Esthetique et psychologie du cinema , 2 vols. Paris: Editions Universitaires.

- Mulvey, L. (1989). Visual pleasure and narrative cinema. In Visual and other pleasures .

- Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 14–26. (Original work published 1975).

- Nichols, B. (1991). Representing reality . Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Panofsky, E. (1939). Studies in iconology . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Panofsky, E. (1991). Perspective as symbolic form (trans. C. S. Wood). New York: Zone Books. (Original work published 1924).

- Rorty, R. (1979). Philosophy and the mirror of nature . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Rosenblum, B. (1978). Photographers at work . New York: Holmes and Meier.

- Ruby, J. (2000). Picturing culture: Explorations in film and anthropology . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Schwartz, D., & Griffin, M. (1987). Amateur photography: The organizational maintenance of an aesthetic code. Natural audiences: Qualitative research of media uses and effects (ed. T. Lindlof). Norwood, NJ: Ablex, pp. 198–224.

- Sekula, A. (1975). On the invention of photographic meaning. Art Forum , January, 37–45.

- Tuchman, G. (1978). Representation and the news narrative. In Making news: A study in the construction of reality . New York: Free Press.

- Williams, R. (1974). Television: Technology and cultural form . London: Fontana/Collins.

- Williamson, J. (1978). Decoding advertisements . London: Marion Boyars.

- Worth, S. (1981). Studying visual communication . Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Worth, S., & Adair, J. (1972). Through Navajo eyes . Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Worth, S., & Gross, L. (1974). Symbolic strategies. Journal of Communication , 24, 27–39. (Reprinted in S. Worth, Studying visual communication , Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1981.)

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Research of visual attention networks in deaf individuals: a systematic review.

- 1 Department of Psychology, University of Almería, Almería, Spain

- 2 CIBIS Research Center, University of Almería, Almería, Spain

- 3 Growing Brains, Washington, DC, United States

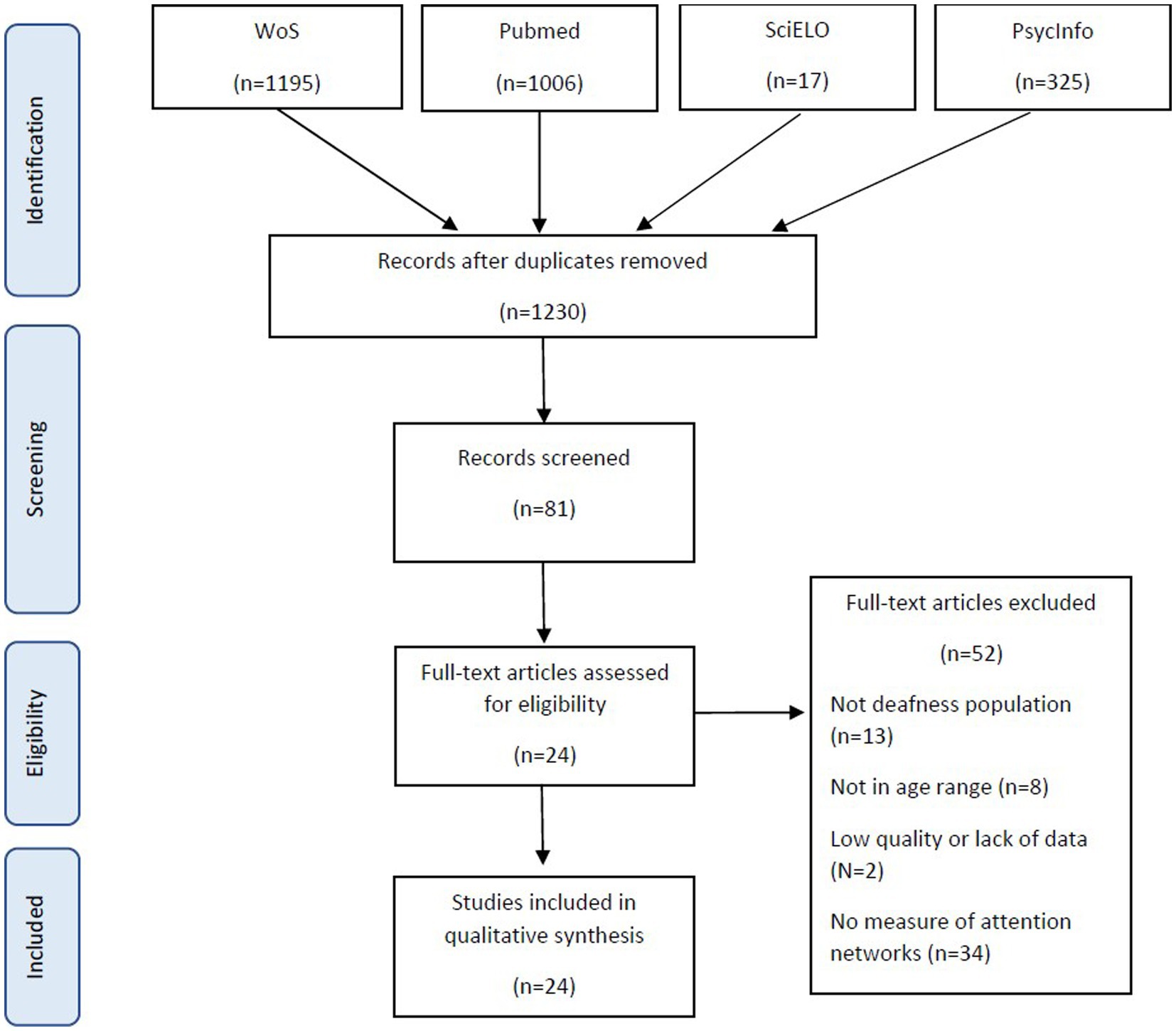

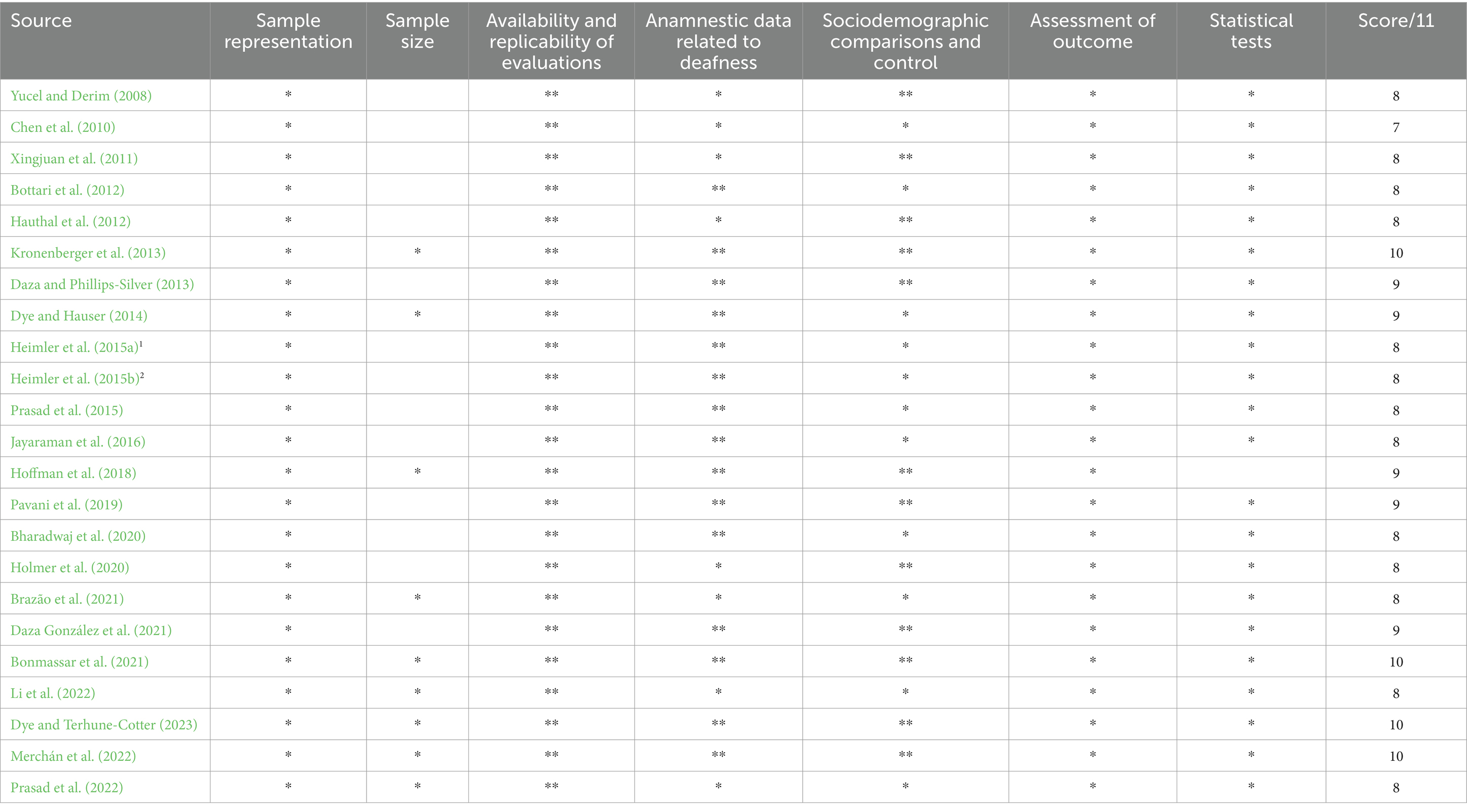

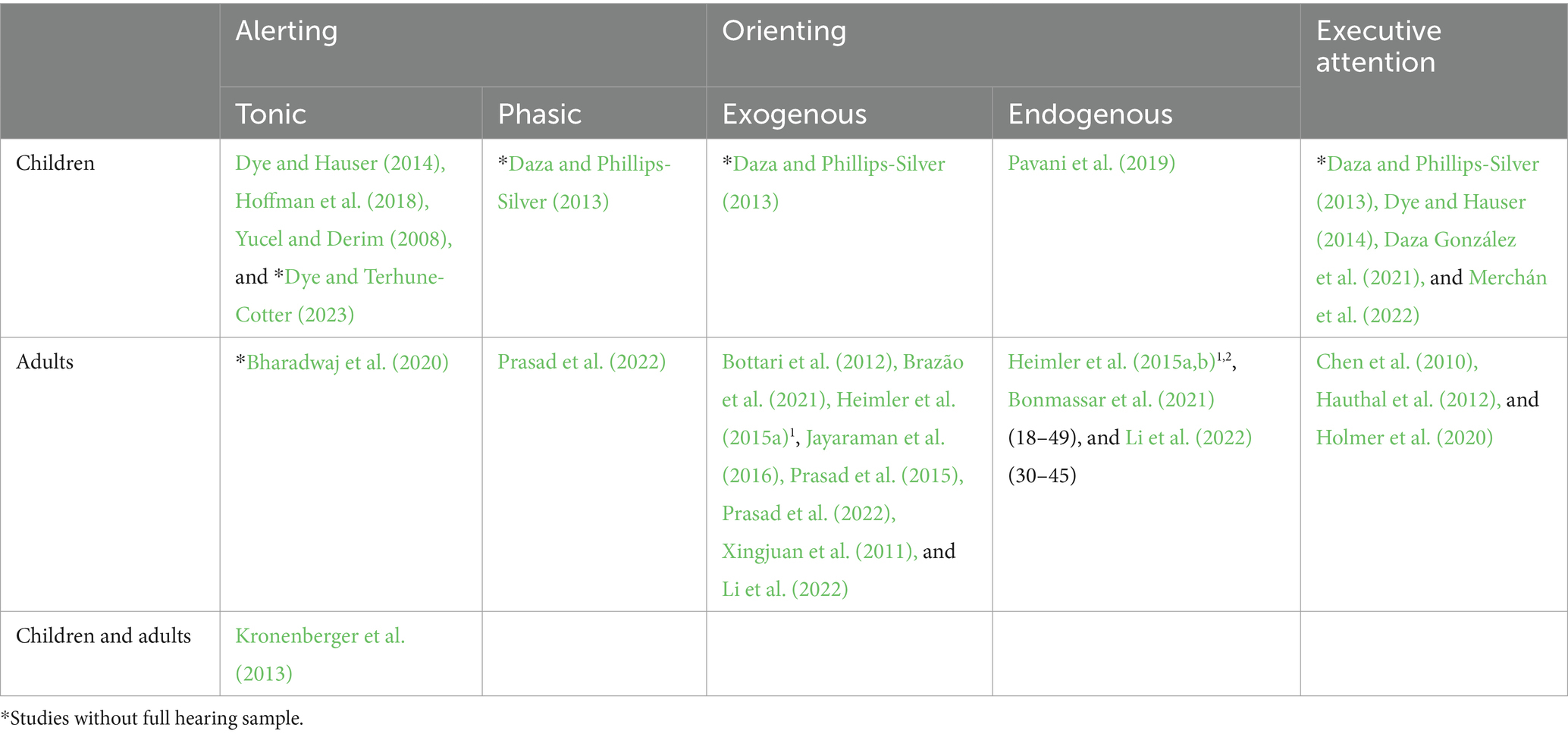

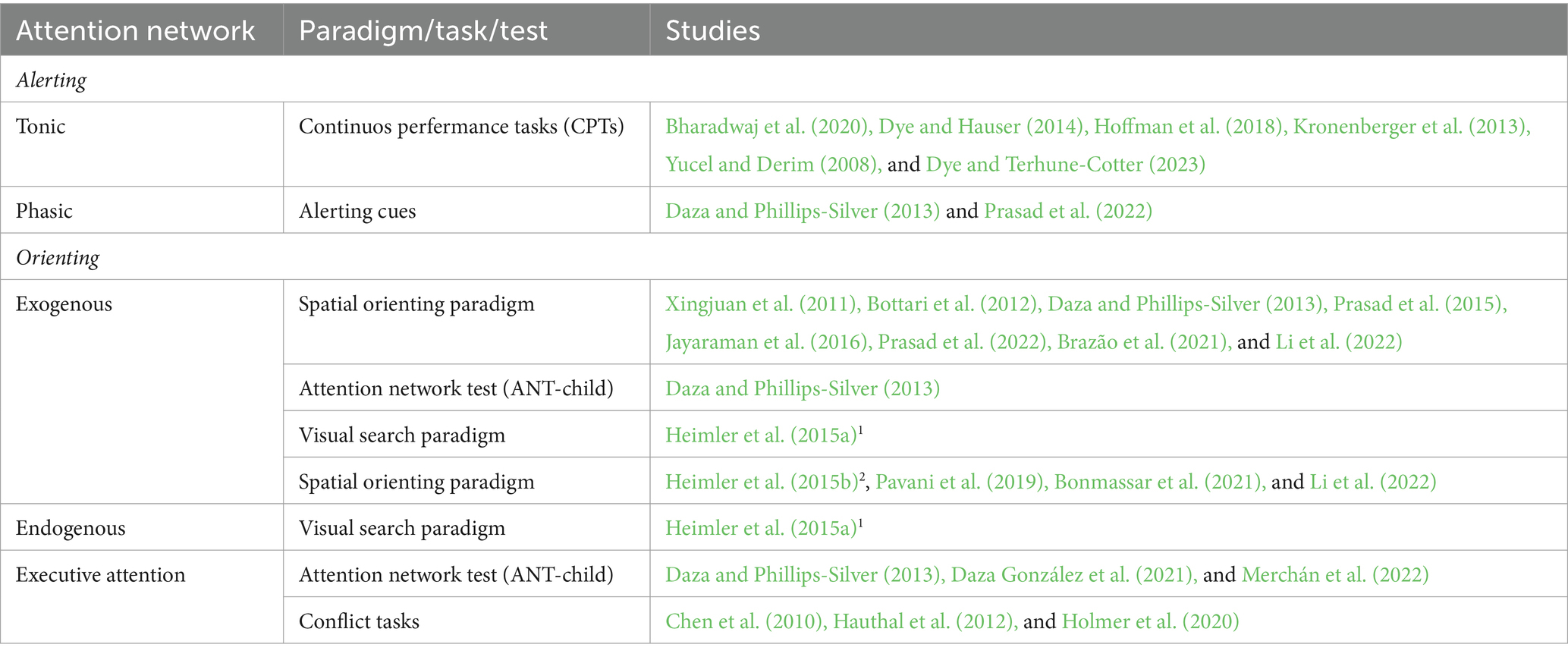

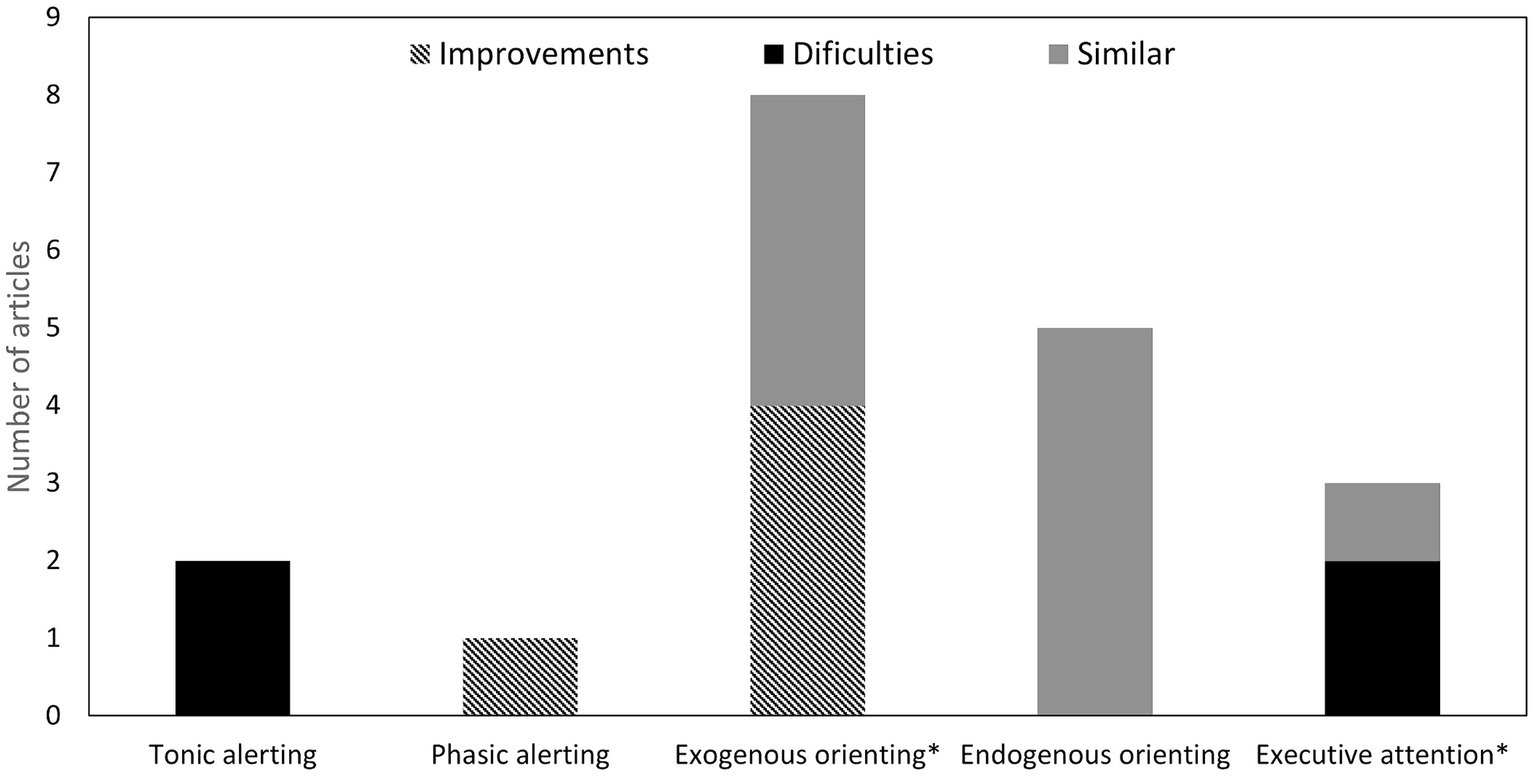

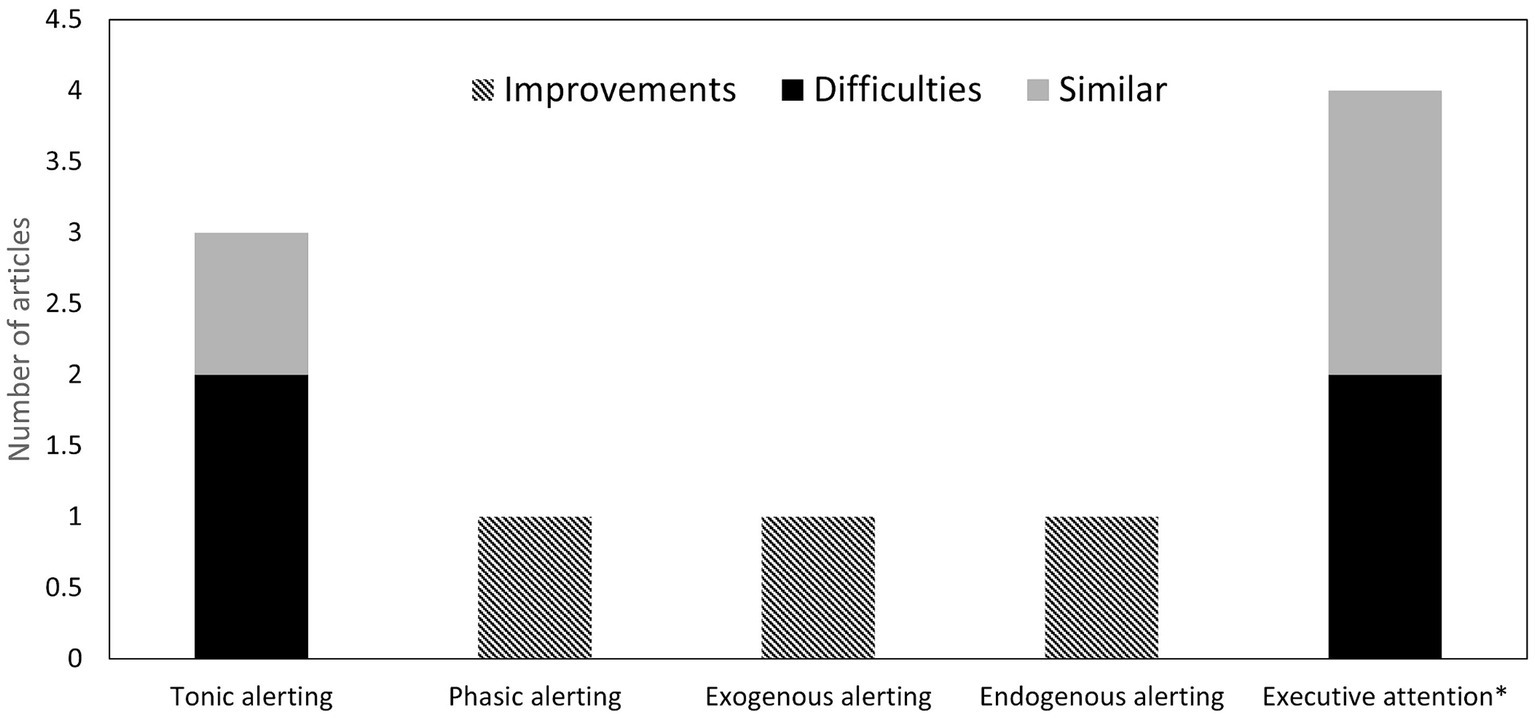

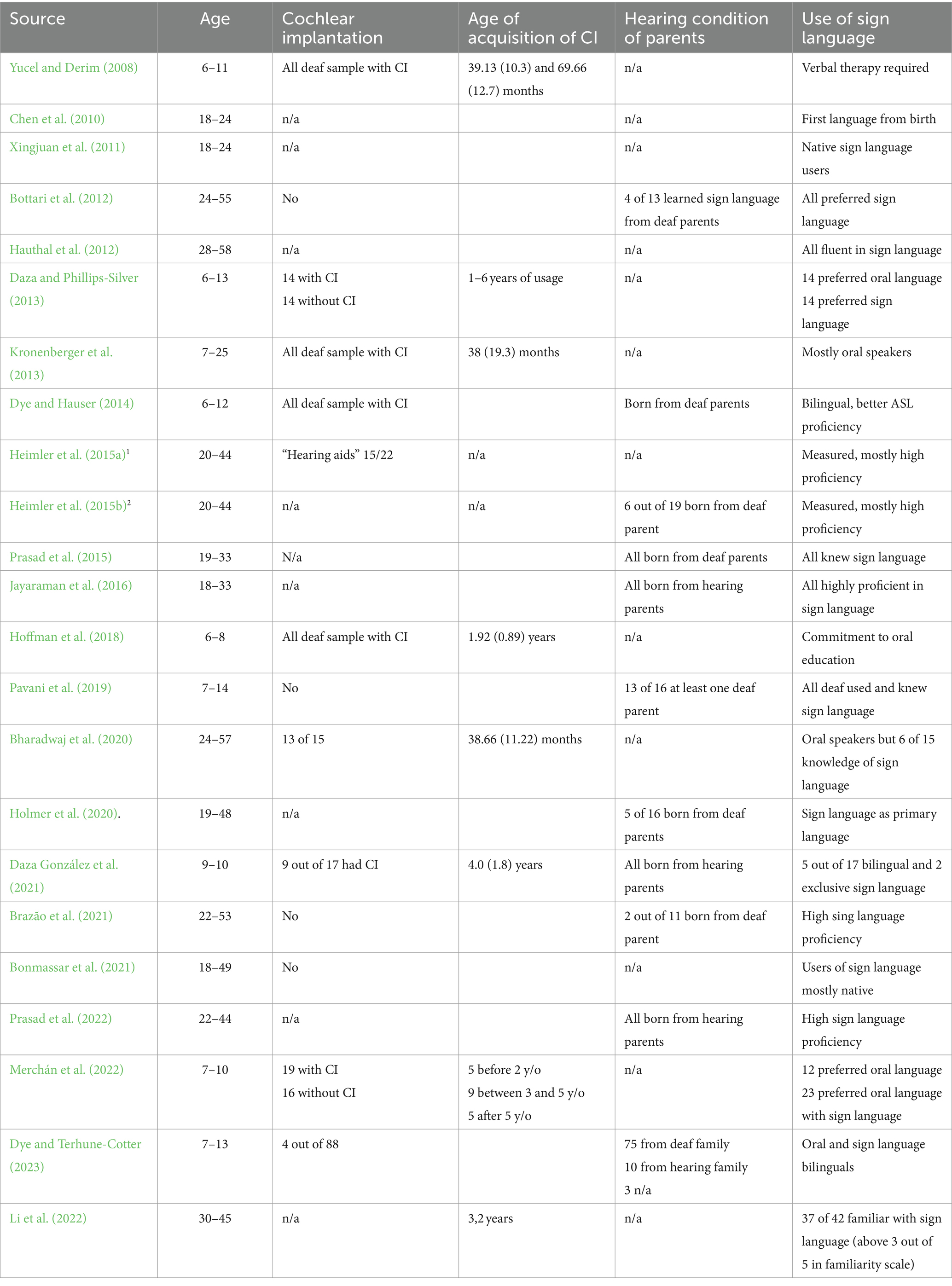

The impact of deafness on visual attention has been widely discussed in previous research. It has been noted that deficiencies and strengths of previous research can be attributed to temporal or spatial aspects of attention, as well as variations in development and clinical characteristics. Visual attention is categorized into three networks: orienting (exogenous and endogenous), alerting (phasic and tonic), and executive control. This study aims to contribute new neuroscientific evidence supporting this hypothesis. This paper presents a systematic review of the international literature from the past 15 years focused on visual attention in the deaf population. The final review included 24 articles. The function of the orienting network is found to be enhanced in deaf adults and children, primarily observed in native signers without cochlear implants, while endogenous orienting is observed only in the context of gaze cues in children, with no differences found in adults. Results regarding alerting and executive function vary depending on clinical characteristics and paradigms used. Implications for future research on visual attention in the deaf population are discussed.

1 Introduction

1.1 background.

Early auditory deprivation is recognized as a factor influencing the development of visual attention in deaf individuals ( Colmenero et al., 2004 ; Bavelier et al., 2006 ; Stevens and Neville, 2006 ). However, existing evidence on the nature of this effect is conflicting and, crucially for the present review, unclear concerning the temporal versus spatial distribution of visual attention. Historically, research on this topic has been centered on two seemingly opposing hypotheses: the deficiency hypothesis, positing that early profound deafness leads to visual attention deficits, and the enhancement hypothesis, suggesting compensatory changes to visual attention processes ( Dye and Bavelier, 2010 ).

According to the deficiency hypothesis , integrating information from different senses is essential for the normal development of attention functioning within each sensory modality. Consequently, the absence of auditory input results in underdeveloped selective attention capacities. For deaf individuals, the lack of audition impairs the development of multisensory integration, thereby impeding the typical development of visual attention skills. Put simply, while hearing people can selectively attend to a narrow visual field and still monitor the broader environment through sounds, deaf individuals must use vision to accomplish both specific tasks and monitor the broader environment ( Smith et al., 1998 ).

This view has been primarily supported by studies examining sustained visual attention or vigilance using the Continuous Performance Test or “CPT.” For example, using the Gordon Diagnostic System (GDS), a widely used CPT, the participant is presented with digits and must respond when a “1” is followed by a “9” for around 10 min ( Dye and Hauser, 2014 ). These studies have found consistent underperformance in CPTs among the deaf population, indicating that auditory input plays a role in organizing visual attention. These results are consistent with a deficit view of cross-modal reorganization stemming from early sensory deprivation ( Mitchell and Quittner, 1996 ; Smith et al., 1998 ; Quittner et al., 2004 ).

Although CPTs have been widely used to assess sustained visual attention, these tasks are sensitive to certain additional cognitive factors ( Parasnis et al., 2003 ). Specifically, CPTs require sustained attention and the ability to hold information about the target sequence in working memory, and performance is negatively affected by the inability to inhibit responses to non-target stimuli.

In contrast to the deficiency hypothesis, the enhancement hypothesis or compensation view is based on the common assumption that deficits in one sensory modality lead to heightened sensitivities in the remaining modalities ( Bavelier et al., 2006 ). In the case of early deafness, this perspective posits that the visual system is reorganized to compensate for the lack of auditory input. Consequently, visual skills assume the functional roles previously performed by audition in the typically developing child, such as monitoring the environment or discriminating temporally complex stimuli ( Bottari et al., 2014 ; Benetti et al., 2017 ; Bola et al., 2017 ; Seymour et al., 2017 ).

The enhancement or compensation hypothesis has primarily received support from studies measuring the allocation of attention across space. The results of these studies suggest that in deaf individuals, there is a spatial redistribution of visual attention toward the periphery, allowing them to better monitor their peripheral environment based on visual rather than auditory cues ( Loke and Song, 1991 ; Sladen et al., 2005 ). For example, deaf individuals can be faster than hearing controls in detecting the onset of peripheral visual targets ( Chen et al., 2006 ; Bottari et al., 2010 ; Codina et al., 2011 , 2017 ) or in discriminating the direction of visual motion with attention to peripheral locations ( Neville and Lawson, 1987 ; Bavelier et al., 2001 ).

This redistribution of visual attention can alter the trade-off in the responses of deaf people to the periphery versus the centre. Specifically, in situations where central and peripheral static stimuli compete for selective attention resources, deaf participants are more likely to orient visual attention toward peripheral than central locations ( Sladen et al., 2005 ; Chen et al., 2006 ). Consistent with these findings, Proksch and Bavelier (2002) observed that deaf individuals are more distracted by irrelevant peripheral information, whereas hearing individuals are more distracted by irrelevant central information. However, while deaf individuals have been shown to possess a field of view that extends further toward the periphery than hearing controls ( Sladen et al., 2005 ), no differences between deaf individuals and hearing controls have been documented when processing targets presented toward the centre of the visual field ( Neville and Lawson, 1987 ; Loke and Song, 1991 ).

In an initial review conducted by Tharpe et al. (2008) to examine evidence-based literature on visual attention and deafness, various paradigms were explored, including the CPT, the letter cancellation task, and conflict tasks. No conclusive evidence was found to support general enhancement or deficits in visual attention or enhanced fundamental visual sensory abilities ( Tharpe et al., 2002 ). Rather, the authors propose that the variability in performance across these paradigms could be explained by the extensive allocation of attentional resources across the visual field, driven by increased monitoring demands. This hypothesis explains why deaf individuals tend to show poorer performance on tasks requiring sustained attention to central stimuli over time compared to those involving the detection of peripheral stimuli. This idea has been supported by results found using a modified flanker paradigm incorporating several degrees of distance between distractor and target ( Sladen et al., 2005 ).

Functional brain studies have also revealed significant differences between deaf and hearing individuals that support the compensation view. These differences are related to alterations in the visual areas and the activation of visual and attention-related brain networks. For instance, Bavelier et al. (2001) found that the absence of auditory input and sign language use in the deaf population was associated with greater activation of visual cortex areas when processing peripheral and moving stimuli. Furthermore, Mayberry et al. (2011) reported that deaf individuals exhibited greater activation of visual and attention-related brain networks during peripheral visual tasks.

An area of the cortex that has been extensively studied in the context of deafness is the middle temporal (MT) or medial superior temporal (MST) area. MT/MST areas play a key role in detecting and analyzing movement and activity in these areas is modulated by attentional processes ( O’Craven et al., 1997 ). When observing unattended moving stimuli, both deaf and hearing participants show similar recruitment of the MT/MST cortex. However, when required to attend to peripheral movement and ignore concurrent central motion, enhanced recruitment of the MT/MST is observed in deaf individuals relative to hearing controls ( Bavelier et al., 2001 ; Fine et al., 2005 ). This pattern echoes a general trend in the literature, where the most significant population differences have been reported for motion stimuli in the visual periphery under conditions that engage selective attention, such as when the location or time of arrival of the stimulus is unknown or when the stimulus must be selected from distractors ( Bavelier et al., 2006 ). These findings suggest that deafness is associated with alterations in visual attention, resulting in changes in the recruitment of brain networks involved in the processing of visual information.

These apparently contradictory hypotheses highlight the necessity of organising previous research within a recognized model of attention. This review aims to respond to this need by systematically analysing the tasks employed to measure various aspects of attention in each study.

1.2 The integrative hypothesis

The contradictory results mentioned previously prompted an integrative review published by Dye and Bavelier (2010) . These authors proposed that while the deficiency hypothesis and enhancement hypothesis may appear to be mutually exclusive, the conflicting evidence concerning the impact of deafness on visual attention could arise from measuring different aspects of visual attention. Consequently, the deficit view is predominantly supported by studies focused on the allocation of attention over time, whereas the compensation view is backed by studies measuring the allocation of attention across space. Therefore, when considering different aspects of visual attention, a striking pattern of attentional enhancements and deficits emerges as a consequence of early deafness.

In addition, these two perspectives consider groups of different ages and backgrounds. Individuals in the deaf and hard of hearing population are quite diverse regarding their preferred mode of communication (sign language versus oral language), the age of acquisition of their native language, the hearing status of their parents, the aetiology of hearing loss (e.g., genetic, infection), and the implantation of cochlear implants [CI—a small electronic device that is surgically implanted into the inner ear to help provide a sense of sound to individuals with severe to profound hearing loss ( Wilson and Dorman, 2008 )]. Most of the research suggesting that deaf children have problems with visual attention has focused on deaf children learning spoken language, examining changes in sustained visual attention after restoration of auditory input through a CI ( Mitchell and Quittner, 1996 ; Smith et al., 1998 ; Quittner et al., 2004 ). In contrast, studies suggesting that the visual system compensates for the lack of auditory input by enhancing the monitoring of the peripheral visual field have primarily involved deaf adults. Specifically, these studies have focused on culturally deaf individuals born to Deaf parents, acquiring American Sign Language (ASL) as their first language and lacking CI. This group is compared to those who received oral speech therapy and have CI ( Bavelier et al., 2006 ; Dye et al., 2009 ).

Dye and Bavelier (2010) suggested that the deficiency and compensatory views were not necessarily contradictory but complementary in explaining the cross-modal reorganization of visual attention after early deafness. They propose an integrative view in which early auditory deprivation does not have an overall positive or negative impact on visual attention, but rather, selected aspects of visual attention are modified in various ways throughout the developmental trajectory.