- Publications

- Key Findings

- Infographics

- Economy profiles

- Full report

Global Gender Gap Report 2023

Benchmarking gender gaps, 2023

The Global Gender Gap Index was first introduced by the World Economic Forum in 2006 to benchmark progress towards gender parity and compare countries’ gender gaps across four dimensions: economic opportunities, education, health and political leadership.

The goal of the report is to offer a consistent annual metric for the assessment of progress over time. Using the methodology introduced in 2006, the index and the analysis focus on benchmarking parity between women and men across countries and regions.

The level of progress toward gender parity (the parity score) for each indicator is calculated as the ratio of the value of each indicator for women to the value for men. A parity score of 1 indicates full parity. The gender gap is the distance from full parity.

The analysis in this report is focused on assessing gender gaps between women and men across economic, educational, health and political outcomes based on the data available (Figure 1.1).

For further information on the index methodology, please refer to Appendix B.

Country coverage

To ensure a global representation of the gender gap, the report aims to cover as many economies as possible. For a country to be included, it must report data for a minimum 12 of the 14 indicators that comprise the index. We also aim to include the latest data available, reported within the last 10 years.

The report this year covers 146 countries. In this edition, Croatia rejoins the index, whereas Guyana drops out.

Among the 146 countries included this year are a set of 102 countries that have been covered in all editions since the inaugural one in 2006. Scores based on this constant set of countries are used to compare regional and global aggregates across time.

It should be noted that there may be time lags in the data collection and validation processes across the organizations from which the data is sourced, and that all results should be interpreted within a range of global, regional and national contextual factors. The Economy Profiles at the end of the report provide a large range of additional data.

Global results

The Global Gender Gap score in 2023 for all 146 countries included in this edition stands at 68.4% closed. Considering the constant sample of 145 countries covered in the 2022 and 2023 editions, the overall score changed from 68.1% to 68.4%, an improvement of 0.3 percentage points compared to last year’s edition. When considering the 102 countries covered continuously from 2006 to 2023, the gap is 68.6% closed.

Compared to last year, progress towards narrowing the gender gap has been more widespread: 42 of the 145 economies covered in both the 2022 and 2023 editions improved their gender parity score by at least 1 percentage point since the previous edition and 40 other countries registered gains of less than 1 percentage point. The economies with the greatest increase in score (gains of 4 percentage points or more) are Liberia (score: 76%, +5.1 percentage points since the previous edition), Estonia (78.2%, +4.8 percentage points), Bhutan (68.2%, +4.5 percentage points), Malawi (67.6%, +4.4 percentage points), Colombia (75.1%, +4.1 percentage points) and Chile (77.7%, +4.1 percentage points).

While there is an increase in the number of countries registering at least a marginal improvement, such progress is mitigated by an increase in the number of countries with declining scores steeper than 1 percentage point (from 12 in 2022 to 35 in 2023).

Table 1.1 shows the 2023 Global Gender Gap rankings and the scores for all 146 countries included in this year’s report. Although no country has yet achieved full gender parity, the top nine countries (Iceland, Norway, Finland, New Zealand, Sweden, Germany, Nicaragua, Namibia and Lithuania) have closed at least 80% of their gap. For the 14th year running, Iceland (91.2%) takes the top position. It also continues to be the only country to have closed more than 90% of its gender gap. The global top five is completed by three other Nordic countries – Norway (87.9%, 2nd), Finland (86.3%, 3rd) and Sweden (81.5%, 5th) – and one country from East Asia and the Pacific – New Zealand (85.6%, 4th). Additionally, from Europe, Germany (81.5%) moves up to 6th place (from 10th), Lithuania (80.0.%) returns to the top 10 economies, taking 9th place, and Belgium (79.6%) joins the top 10 for the first time in 10th place. One country from Latin America (Nicaragua, 81.1%) and one from Sub-Saharan Africa (Namibia, 80.2%) – complete this year’s top 10, taking the 7th and 8th positions, respectively. The two countries that drop out of the top 10 in 2023 are Ireland (79.5%,11th, down from 9th place) and Rwanda (79.4%, 12th, down from 6th place in 2022).

Performance by subindex

This section discusses the global gender gap scores across the four main components (subindexes) of the index: Economic Participation and Opportunity, Educational Attainment, Health and Survival, and Political Empowerment. In doing so, it aims to illuminate and explore the factors that are driving the overall average global gender gap score.

Summarized in Figure 1.2, this year’s results show that across the 146 countries covered by the 2023 index, the Health and Survival gender gap has closed by 96%, Educational Attainment by 95.2%, Economic Participation and Opportunity by 60.1% and Political Empowerment by 22.1%.

When looking at the sample of 145 countries included in both the 2022 and 2023 editions, results show that this year’s progress is mainly caused by a significant improvement on the Educational Attainment gap and more modest increases for the Health and Survival and Political Empowerment subindexes. The Economic Participation and Opportunity gender parity score has, however, receded since last year.

The score distributions across each subindex offer a more detailed picture of the disparities in country-specific gender gaps across the four dimensions. Figure 1.3 marks the distribution of individual country scores attained both overall and by subindex.

More than two-thirds (69.2%) of countries score above the 2023 population-weighted average Gender Gap Index score (68.4%). Similar to 2022, Afghanistan (40.5%) ranks last, at the lower end of the distribution, with a difference of 27.8 percentage points compared to the mean. In fact, Afghanistan registers the lowest performance across all subindexes, with the exception of the Health and Survival subindex, where it takes the 141st position, ranking below the bottom 5th percentile. The country scoring penultimate in the global ranking is Chad (57.0%), which deviates from the average score by 11.3 percentage points.

Health and Survival, followed by Educational Attainment, continue to display the least amount of variation of scores, whereas the Economic Participation and Opportunity and Political Empowerment subindexes continue to show the widest dispersion of scores. The range of scores in this year’s gender gap in Economic Participation and Opportunity has not changed since last year: the difference between the highest scores (89.5%) and the country with the lowest scores (18.8%) remains extensive (70.8%).

Countries that report relatively even access for men and women when it comes to Economic Participation and Opportunity include economies as varied as Liberia (89.5%), Jamaica (89.4%), Moldova (86.3%), Lao PDR (85.1%), Belarus (81.9%), Burundi (81.0%) and Norway (80%). At the bottom of the distribution, apart from Afghanistan, the countries that attained less than 40% parity include Algeria (31.7%), Iran (34.4%), Pakistan (36.2%) and India (36.7%).

A closer look at performance across the five indicators composing this subindex reveals that an important source of gender inequality stems from the overall underrepresentation of women in the labour market. The global population-weighted score indicates that, on average, only 64.9% of the gender gap in labour-force participation has been closed. Comparing the 102-country constant sample scores of 63.8% for 2023 and 62.9% for 2022, this marks a partial recovery. Chapter 2 examines recent dynamics in labour-force participation and related labour-market outcomes in more detail.

Though stark income gaps continue to hinder economic gender parity, with almost half (48.1%) of the overall earned income gap yet to close, results indicate that many countries experienced improvements since last year. Ninety-six countries (out of the 145 included in 2022 and 2023) progressed in bridging income gaps. The highest-scoring countries on this dimension include Liberia, followed by Zimbabwe (97.6%), Tanzania (90.3%), Burundi (88.3%), Barbados (88.1%) and Norway (85.1%), which all stand at above 85% parity. At the bottom of the distribution, Iran (17.1%), Algeria (19.2%) and Egypt (19.7%) display some of the largest inequalities between the incomes of men and women, scoring less than 20% parity.

When it comes to wages for similar work, the only countries in which the gender gap is perceived as more than 80% closed are Albania (85.8%) and Burundi (84.1%). Merely a quarter of the 146 economies included in this year’s edition score between 70%-80% on this indicator. These include some of the most advanced economies, such as Iceland (78.4% of gap closed), Singapore (78.3%), United Arab Emirates (77.6%), United States (77.3%), Finland (76.3%), Qatar (74.5%), Saudi Arabia (74.1%), Lithuania (74.1%), Slovenia (73.5%), Bahrain (72.8%), Estonia (71.4%), Barbados (71.2%), Luxembourg (70.4%), New Zealand (70.4%), Switzerland (70.3%), and Latvia (70.1%). The lowest-ranking countries on this dimension are Croatia (49.7% of the gap closed) and Lesotho (49.4%). Compared to last year’s performance, Bolivia, El Salvador and South Africa registered the largest improvements in score, of 5 percentage points or more.

Cross-country disparities are more pronounced in terms of the gender gap in senior, managerial and legislative roles, which globally stands at 42.9%. Ten countries assessed this year – six of which located in Sub-Saharan Africa – report parity on this indicator. Afghanistan, Pakistan and Algeria rank at the bottom, with less than 5% of professionals in senior positions being women. When it comes to professional and technical positions, 71% of the gender gap has been closed globally. Whereas women’s representation in managerial roles relative to men’s has improved by at least 1 percentage points for 38 countries, gender parity in professional and technical roles has improved for only 20 countries by the same measure (at least 1 percentage points).

Educational Attainment is the subindex with the second-highest global parity score, with only 4.8% of the gender gap left to close. When looking at the subset of 145 countries included in both 2022 and 2023, the number of economies with full gender parity in Educational Attainment has increased from 21 to 25. Cross-country scores on this dimension are less dispersed than for the Economic Participation or Political Empowerment subindices, with the majority (80.1%, or 117 out of 146) of participating countries having closed at least 95% of their educational gender gap. Similar to last year, Afghanistan is the only country where the educational gender parity score is below the 50% mark, at 48.2%. At the bottom of the distribution, we also encounter the Sub-Saharan countries of Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Guinea, Angola, Niger and Mali – all with scores above 60%, but below 80% in educational parity (between 63.7%-77.9%).

Across indicators of the subindex, gender parity is lowest for literacy rate: globally, 94% of the gender gap in the proportion of those over 15 years of age who are literate has closed. Fifty-six countries have achieved full parity in literacy rate, whereas Afghanistan and Sub-Saharan countries such as Mali, Liberia, Chad and Guinea all register parity scores below 55%. When it comes to enrolment in primary education, full parity scores are more widespread: 65 countries register equivalent rates of enrolment in primary education for boys and for girls. The rest of the countries included this year display at least 90% parity, apart from the Sub-Saharan countries of Mali, Guinea and Chad, which score within the 80.4%-89.9% range.

Cross-national variation is wider for both secondary and tertiary enrolment. Whereas most countries (135) included in this edition closed at least 80% of their gender gap in secondary enrolment, a handful of countries remain below this threshold, with Congo (64% of the gap closed), Chad (58.3%) and Afghanistan (57.1) ranking last. Geographical disparities are even starker for tertiary education. While 101 countries display full parity on this indicator, including Cambodia as the most recent to reach the 1 parity mark this year, 18 more countries stand within the 80.2%-99.5% range, while several countries from Sub-Saharan Africa (such as Burkina Faso, Mali and Côte d’Ivoire), Southern Asia (Afghanistan), and Eurasia and Central Asia (Tajikistan) still have between 21.7% (Côte d’Ivoire) and 71% (Afghanistan) of their gaps left to close.

The Health and Survival subindex displays the highest level of gender parity globally (at 96%) as well as the most clustered distribution of scores. The majority of countries (91.1%) register at most 2 percentage points above the average, and only a handful of others (13 out of 146) register at most 2.4 percentage points below the average. Twenty-six countries – most from Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Sub-Saharan Africa – display the top score of 98% parity, 1 whereas Qatar, Viet Nam and populous countries such as Azerbaijan, India and China all score below the 95% mark.

Qatar’s lower overall ranking is driven by relatively lower parity in terms of healthy life expectancy. Though in most countries women tend to outlive men, in five Middle Eastern and North African countries (Morocco, 99.9%; Bahrain, 99.3%; Algeria, 99%; Jordan, 98.7%; Qatar, 95.5%), one from Sub-Saharan Africa (Mali, 99.3%) and two from Southern Asia (Pakistan, 99.9%, and Afghanistan, 97.1%), the reverse is true.

For Viet Nam, Azerbaijan, India and China, the relatively low overall rankings on the Health and Survival subindex is explained by skewed sex ratios at birth. Compared to top scoring countries that register a 94.4% gender parity at birth, the indicator stands at 92.7% for India (albeit an improvement over last edition) and below 90% for Viet Nam, China and Azerbaijan.

Finally, the Political Empowerment subindex registers once again the largest gender gap, at only 22.1% of the gap closed and the greatest spread of scores across countries. Iceland stands out as best performer, with a 90.1% parity score, which is 13.6 percentage points greater than the country ranking second (Norway) and 69 percentage points above the median global score (21.1%). In addition to the first two ranked, only 10 other countries out of the 146 included this year score above the 50% parity score: New Zealand (72.5%), Finland (70%), Germany (63.4%), Nicaragua (62.6%), Bangladesh (55.2%), Mozambique (54.2%), Rwanda (54.1%), Costa Rica (52.4%), Sweden (51.2%) and Chile (50.2%). The lowest parity scores are found for: Myanmar (4.7%), Nigeria (4.1%), Iran (3.1%), Lebanon (2.1%), Vanuatu (0.6%) and Afghanistan (0%).

Iceland and Bangladesh are the only countries where women have held the highest political position in a country for a higher number of years than men. In 67 other countries, women have never served as head of state in the past 50 years.

In terms of the share of women in ministerial positions, 11 out of 146 countries, led by Albania, Finland and Spain, have 50% or more ministers who are women. However, 75 countries have 20% or less female ministers. Further, populous countries such as India, Türkiye and China have less than 7% ministers who are women and countries like Azerbaijan, Saudi Arabia and Lebanon have none.

As regards to parity in the number of seats in national parliaments, five countries stand at full parity: Mexico, Nicaragua, Rwanda, the United Arab Emirates and (as of this year’s edition) New Zealand. The countries with the least representation of women in parliament (less than 5%) are Maldives (4.8% of the gender gap closed), Qatar (4.6%), Nigeria (3.7%), Oman (2.4%) and Vanuatu (1.9%). Though still below the 40% parity threshold, Benin and Malta saw the largest improvements for this indicator, experiencing a rise of 26.6 and 23.2 percentage points, respectively.

Progress over time

By calculating how much the gap has, on average, reduced each year since the report’s first edition in 2006, using a constant sample of 102 countries, it is possible to project how many years it will take to close each of the gender gaps for each of the dimensions tracked. The 17-year trajectory of global gender gaps is charted accordingly in Figure 1.4.

This year’s results leave the total progress made towards gender parity at an overall 4.1 percentage-point gain since 2006. Hence, on average, over the past 17 years, the gap has been reduced by only 0.24 percentage points per year. If progress towards gender parity proceeds at the same average speed observed between the 2006 and 2023 editions, the overall global gender gap is projected to close in 131 years, compared to a projection of 132 years in 2022. This suggests that the year in which the gender gap is expected to close remains 2154, as progress is moving at the same rate as last year.

The Economic Participation and Opportunity subindex now stands at 59.8% based on the 102 countries in the constant sample (non-constant score 60.1%). This subindex is the only one that receded compared to 2022. There is a drop of 0.2 percentage points since 2022, but an improvement of 4.1 percentage points since 2006. The ebbing of the upward trend seen in last year’s edition can be partially attributed to the drop in the subindex scores for 66 economies including highly populated economies such as China, Indonesia, Nigeria, etc. As a result, it will take another 169 years to close the economic gender gap.

The Educational Attainment subindex displays the highest gender parity score (96.1%) on the basis of 102 countries in the constant sample (non-constant score 95.2%). The 0.8 percentage-point increase since last year places it from second to top-ranked across all subindices. While the development has not been unfaltering over time – accelerating then plateauing at various points in time and dropping in 2017-2018 and 2022 – the time-series analysis shows a definitive upward trend overall. Its improved performance as well as a steady pace of progress on average over the 2006-2023 period leads to an estimation of 16 years to close the gap.

The Health and Survival gender parity score stands at 95.9% based on the constant sample of 102 countries (non-constant score 96%). It is a modest improvement compared to last year (+0.2 percentage points) and an actual drop of 0.3 percentage points compared to 2006. Despite this slight long-term drop, the index has consistently stayed above the 95% mark since the inception of the index in 2006.

Based on the constant sample of 102 countries included in each edition from 2006 to 2023, the global Political Empowerment gender gap this year is 22.5% (non-constant score 22.1%), which is a slight improvement of 0.1 percentage points over 2022. A slower pace of improvement, however, means that it will now take another 162 years to completely close this gap, a significant step backwards compared to the 2022 edition. Yet, the 2023 score is the highest absolute increase of all four subindexes since 2006: 8.2 percentage points compared to 4.4 percentage points for Educational Attainment, which is the subindex with the second-greatest improvement.

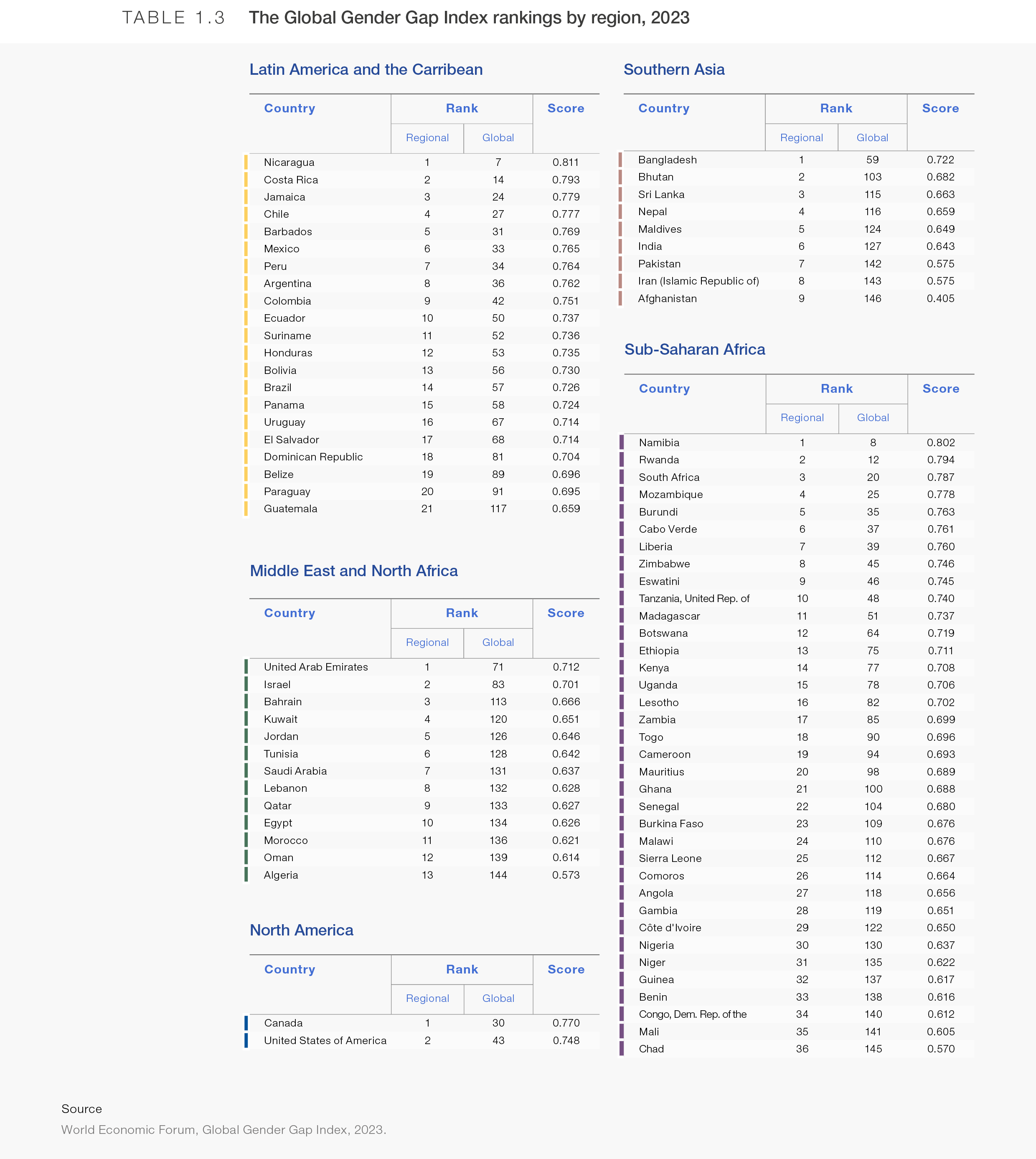

Performance by region

The Global Gender Gap Report 2023 categorizes countries into eight regions: Eurasia and Central Asia, East Asia and the Pacific, Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, Middle East and North Africa, North America, Southern Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa. Countries in each regional group are listed in Appendix A.

Gender parity in Europe (76.3%) surpasses the parity level in North America (75%) this year to rank first among regions. Closely behind Europe and North America is Latin America and the Caribbean, with 74.3% parity. Trailing more than 5 percentage points behind Latin America and the Caribbean are Eurasia and Central Asia (69%) as well as East Asia and the Pacific (68.8%). Sub-Saharan Africa ranks 6th (68.2%), slightly below the global weighted average score (68.3%). Southern Asia (63.4%) overtakes the Middle East and North Africa (62.6%), which is, in 2023, the region furthest away from parity.

Using the 102-country constant sample to assess trends over time suggests that Southern Asia as well as Latin America and the Caribbean experienced an improvement of 1.1 percentage points and 1.7 percentage points, respectively, since the last edition. Sub-Saharan Africa improves marginally (+0.1 percentage points) while Eurasia and Central Asia (-0.01 percentage points), East Asia and the Pacific (-0.02 percentage points), and Europe (-0.02 percentage points) show a slight decline. North America (-1.9 percentage points) and the Middle East and North Africa (-0.09 percentage points) suffer more significant setbacks in overall gender parity.

The longer-term trends offer further insights into progress in the regional gender parity profiles. In comparison to the inaugural edition in 2006, the Latin America and the Caribbean region has improved the most, with an increase of 8.4 percentage points over the past 17 years. Europe (+6.1 percentage points) and Sub-Saharan Africa (+5.2 percentage points) are the other two regions that have improved by more than 5 percentage points. North America (+4.5 percentage points), the Middle East and North Africa (+4.2 percentage points) and Southern Asia (+4.1 percentage points) have improved by more than 4 percentage points, though parity scores in all three regions have backslid in recent editions. Eurasia and Central Asia (+ 3.2 percentage points) and East Asia and the Pacific (+ 2.8 percentage points) have seen the slowest to progress since 2006.

A more nuanced picture emerges from the heat map in Figure 1.6, which disaggregates regional scores by subindex and represents higher levels of parity using a darker colour. Most regions have achieved relatively higher parity in Educational Attainment and Health and Survival. The advancement in Economic Participation and Opportunity is more uneven, with Southern Asia closing 37.2% of the gender gap and North America closing more than double. Regions continue to have the most significant gaps in the Political Empowerment subindex, with only Latin America and the Caribbean as well as Europe recording more than 35% parity.

Eurasia and Central Asia

At 69% parity, Eurasia and Central Asia ranks 4th out of the eight regions on the overall Gender Gap Index. Based on the aggregated scores of the constant sample of countries included since 2006, the parity score since the 2020 edition has stagnated, although there has been an improvement of 3.2 percentage points since 2006. Moldova, Belarus and Armenia are the highest-ranking countries in the region, while Azerbaijan, Tajikistan and Türkiye rank the lowest. The difference in parity between the highest- and the lowest-ranked country is 14.9 percentage points. At the current rate of progress, it will take 167 years for the Eurasia and Central Asia region to reach gender parity.

Regional gender parity on Economic Participation and Opportunity has been steadily increasing. Overall, 68.8% of the gender gap has closed, which is a 0.5 percentage-point improvement since the last edition. Six out of 10 countries, led by Moldova, Belarus and Azerbaijan, have at least 70% parity on this subindex. All countries in the region except Kyrgyzstan have made varying degrees of progress since the 2022 edition, with Moldova and Armenia making the most progress. Furthermore, all countries in the region have advanced towards parity in estimated earned income. Türkiye and Tajikistan demonstrate the least parity on Economic Participation and Opportunity, with Türkiye being the only country that has closed less than 60% of the gap on this subindex.

Eight out of 10 countries have more than 99% parity on the Educational Attainment subindex, resulting in 98.9% parity for the region. Türkiye and Ukraine, the region’s two most populous countries, have a persistent disparity in secondary enrolment. Barring Türkiye and Tajikistan, all countries have attained parity in enrolment in tertiary education.

At 97.4% parity, Eurasia and Central Asia has only three out of 10 countries that have less than 97% parity for the Health and Survival subindex. Azerbaijan and Armenia, home to more than 13 million people combined, have some of the lowest sex ratios at birth in the world. Finally, seven out of the 10 countries have reached parity in healthy life expectancy.

Compared to other regions, Eurasia and Central Asia has the lowest gender parity in Political Empowerment and suffers a 1 percentage-point setback since 2022. Its score of 10.9% is barely half the global score of 22.1%. Only Armenia, Ukraine and Tajikistan have made at least a 1 percentage-point improvement. While more than one-fifth of ministers in Moldova and Ukraine are women, Azerbaijan continues to be one of the handful countries with a male-only cabinet. Further, five of the 10 countries in the region have more than 25% women parliamentarians. With female presidents in Georgia and Moldova, there has been some improvement in female head-of-state representation in the last 50 years.

East Asia and the Pacific

East Asia and Pacific is at 68.8% parity, marking the fifth-highest score out of the eight regions. Progress towards parity has been stagnating for over a decade and the region registers a 0.2 percentage-point decline since the last edition. While 11 out of 19 countries improve, one stays the same and eight (including China, the world’s second-most populous country) recede on the overall index. New Zealand, the Philippines and Australia have the highest parity at the regional level, with Australia and New Zealand also being the two most-improved economies in the region. On the other hand, Fiji, Myanmar and Japan are at the bottom of the list, with Fiji, Myanmar and Timor-Leste registering the highest declines. At the current rate of progress, it will take 189 years for the region to reach gender parity.

Compared to the last edition, six out of 19 countries improved on the Economic Participation and Opportunity subindex, depleting the regional parity score by 1.1% to 71.1%. Nine out of 17 countries that have the data have shown drops in the share of women in senior official positions. However, 13 out of 19 countries improved parity in estimated earned income since the last edition. Overall, Lao PDR, the Philippines and Singapore register the highest parity for the subindex and Fiji, Timor-Leste and Japan register the lowest.

At 95.5%, East Asia and the Pacific has the second-lowest score on the Educational Attainment subindex compared to other regions. Malaysia and New Zealand are at full parity, along with nine other countries in the region, with more than 99% scores. China, Lao PDR and Indonesia, with more than 1.7 billion people, have the lowest parity. Cambodia and Thailand are the only countries in this region with more than 1 percentage-point increase in parity over 2022. Thailand improves parity in enrolment in secondary education while Cambodia improves on literacy rate and enrolment in primary and tertiary education.

On the Health and Survival subindex, Singapore attains gender parity in sex ratio at birth, joining seven other countries across the world with the same achievement. However, 11 out of 19 countries saw declining parity in sex ratio. This contributes to the region’s slight depletion of parity on this subindex, by 0.02% to 94.9%.

Parity in Political Empowerment sees a partial recovery of 0.7 percentage points to 14.1% since the last edition. However, this is still below the 2018 edition score of 17.1%. Seven countries – including the populous countries such as China, Japan and Indonesia – have regressed on this subindex since 2017. Compared to the previous edition, 13 countries have improved, led by Australia, New Zealand and Philippines. Australia and New Zealand had a considerable increase in the share of women ministers. Fiji, Myanmar and Korea have regressed the most among the six other countries where progress on Political Empowerment has reversed.

Across all subindexes, Europe has the highest gender parity of all regions at 76.3%, with one-third of countries in the region ranking in the top 20 and 20 out of 36 countries with at least 75% parity. Iceland, Norway and Finland are the best-performing countries, both in the region and in the world, while Hungary, Czech Republic and Cyprus rank at the bottom of the region. Overall, there is a decline of 0.2 percentage points in the regional score based on the constant sample of countries. Out of the 35 countries covered in the previous and the current edition, 10 countries, led by Estonia, Norway and Slovenia, have made at least a 1 percentage-point improvement since the last edition. Ten countries show a decline of at least 1 percentage point, with Austria, France and Bulgaria receding the most. At the current rate of progress, Europe is projected to attain gender parity in 67 years.

At 69.7% parity in Economic Participation and Opportunity, Europe stands third behind North America and East Asia and Pacific on this dimension. Gender parity has receded by 0.5 percentage points compared to last year based on the constant sample of 102 countries. Norway, Iceland and Sweden have the highest parity on Economic Participation and Opportunity, while Italy, North Macedonia and Bosnia and Herzegovina have the lowest. In comparison to the last edition, 13 countries (including populous France and Germany) have declined by at least 1% and eight countries have improved by at least 1 percentage point. The shares of senior officer positions held by women have reduced in 17 out of 35 countries that have data. Only 10 countries have at least 60% parity in senior officer positions, yet 28 out of 36 countries have full parity in women’s share of technical roles.

On Educational Attainment, the region is almost at parity and all countries score more than 97%. There is full parity in enrolment in tertiary education, while 20 out of 35 countries reach parity in secondary education and 21 countries in primary education.

On Health and Survival, 97% parity is achieved. The trend, however, is negative. There has been a 0.6 percentage-point decline since the 2015 edition, driven by the reduction in gender parity in healthy life expectancy by at least 1 percentage point in 23 out of 36 countries. On sex ratio at birth, 20 out of 36 countries are at full parity and the other countries are close to parity.

Gender parity in Political Empowerment had been consistently increasing in the last decade until last year; currently, it stands at 39.1%. Based on the constant sample of countries, there has been a decline of 0.5 percentage points since the last edition. Overall, Iceland, Norway and Finland have the highest score on the Political Empowerment subindex, while Romania, Cyprus and Hungary are at the bottom of the table. Led by Estonia, Slovenia and Latvia, 15 out of 35 countries have had at least a 1 percentage-point improvement while 13 countries have seen at least 1 percentage-point decline.

Latin America and the Caribbean

With incremental progress towards gender parity since 2017, Latin America and the Caribbean has bridged 74.3% of its overall gender gap. After Europe and North America, the region has the third-highest level of parity. Since the last edition, seven out of 21 countries (including relatively populous countries like Colombia, Chile, Honduras and Brazil) have improved their gender parity scores by at least 0.5 percentage points, while five countries have seen a decline in their parity scores by at least 0.5 percentage points. This has led to a 1.7 percentage-point increase in overall gender parity since last year. Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Jamaica register the highest parity scores in this region and Belize, Paraguay and Guatemala the lowest. At the current rate of progress, Latin America and the Caribbean will take 53 years to attain full gender parity.

Parity in Economic Participation and Opportunity in Latin America and the Caribbean is at 65.2%, the third-lowest regional score, ahead of the Middle East and North Africa as well as Southern Asia. Yet it marks an 0.7 percentage-point improvement since the last edition, with all countries except four improving their scores. Jamaica, Honduras and the Dominican Republic have seen the most progress on this subindex since the last edition. These three countries, along with 14 others have improved their parity scores in estimated earned income since 2022. Further, eight countries have a one-percentage-point higher share of senior positions held by women compared with the last edition.

Latin America and the Caribbean has achieved 99.2% parity on the Educational Attainment subindex: 14 out of 20 countries have more than 99% parity on their literacy rates. In addition, all of the 18 countries that have data on enrolment in tertiary education have attained full parity on this indicator. Further, the number of countries with parity in enrolment in secondary education is 16, while nine countries have attained full parity in enrolment in primary education.

In comparison to other regions, Latin America and the Caribbean has the highest parity on the Health and Survival subindex, at 97.6%. All countries have attained parity in sex ratio at birth and six out of 21 countries have perfect parity in healthy life expectancy.

At 35% parity, the region has the second-highest score, after Europe, on the Political Empowerment subindex. Based on the constant sample of countries there has been a 0.6 percentage-point improvement in parity since 2022. Overall, nine out of 21 countries have experienced at least a 0.5 percentage-point improvement and nine have seen a decline of more than 0.5%. Colombia, Chile and Brazil are not only the region’s top-ranked countries; they are also the most improved. Five out of 21 countries in this region have seen at least a 1 percentage-point improvement in the share of parliamentary positions held by women.

Middle East and North Africa

In comparison to other regions, Middle East and North Africa remains the furthest away from parity, with a 62.6% parity score. This is a 0.9 percentage-point decline in parity since the last edition for this region, based on the constant sample of countries covered since 2006. The United Arab Emirates, Israel and Bahrain have achieved the highest parity in the region, while Morocco, Oman and Algeria rank the lowest. The three most populous countries – Egypt, Algeria and Morocco – register declines in their parity scores since the last edition. On the other hand, five countries, led by Bahrain, Kuwait and Qatar, have increased their parity by 0.5% or more. At the current rate of progress, full regional parity will be attained in 152 years.

When it comes to Economic Participation and Opportunity, 44% of the gender gap has been closed, ranking the region 7th out of eight regions, just above Southern Asia. There is highly uneven progress in parity on this subindex among different countries. Algeria’s level of parity, 31.7%, is less than half of that of Israel which has closed 68.9% of the gender gap. The United Arab Emirates and Egypt have registered increases in both the share of women senior officer positions and the share of women in technical positions. Further 10 out of 13 countries in the region have advanced towards parity in estimated earned income by at least 0.5 percentage points.

The Middle East and North Africa is at 95.9% parity on the Educational Attainment subindex, and Israel is the only country in the region to have full parity. Kuwait, Bahrain and Jordan come close, with more than 99% gender parity. Relatively more populous countries such as Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Egypt have the lowest parity on this subindex, and they also have the lowest parity in literacy rate. Only four countries (Israel, Bahrain, Qatar and Jordan) have more than 99% parity in literacy rate. Seven countries achieve parity in secondary education and 10 countries in tertiary education.

The region records 96.4% parity in Health and Survival, and all countries except Qatar have achieved more than 95% parity, while all countries have attained perfect parity in sex ratio at birth. However, in five countries healthy life expectancy for women is lower than that of men.

The Middle East and North Africa also has the second-lowest regional parity in political empowerment at 14%. Based on the sample of countries covered continuously since 2006, parity on the Political Empowerment subindex has regressed by 1 percentage point since last year. Parity has declined in seven out of 13 countries, including the region’s most populous countries – Egypt, Algeria and Tunisia – and increased in six other countries, led by Bahrain, Qatar and Kuwait. Bahrain, Kuwait and Lebanon have also seen significant increases in the share of parliamentary positions held by women, while Israel and Tunisia have seen a drop on this indicator since 2022. In terms of ministerial positions held by women, only Tunisia, Bahrain and Morocco have more than 20% female ministers, while Saudi Arabia and Lebanon continue to have an all-male cabinet. Apart from Tunisia and Israel, no country in this region has had a female head of state in the last 50 years.

North America

Just behind Europe, North America ranks second, having closed 75% of the gap, which is 1.9 percentage points lower than the previous edition. While Canada has registered a 0.2 percentage-point decline in the overall parity score since the last edition, the United States has seen a reduction of 2.1 percentage points. At the current rate of progress, 95 years will be needed to close the gender gap for the region.

North America has achieved the highest gender parity score among all regions, 77.6%, on the Economic Participation and Opportunity subindex. This marks a 0.2 percentage-point increase in the parity score since the last edition. Canada improved by 0.5 percentage points and the United States by 0.2 percentage points. Parity in wage equality for similar work and estimated earned income increased in both countries.

Regional parity on the Educational Attainment subindex stands at 99.5%. While Canada has achieved full parity, the United States barring enrolment in secondary education, is virtually at parity for literacy rate, enrolment in primary education and enrolment in tertiary education.

With a score of 96.9%, North America ranks 5th out of eight regions on the Health and Survival subindex. The region has seen a 1 percentage-point decline in parity in health since 2013. For example, parity for healthy life expectancy, at 1.03, is more than just Middle East and North Africa and Southern Asia. Women’s healthy life expectancy has declined more than that of men since 2013 in both Canada and the United States, further contributing the reduction in parity on this subindex.

The decline in the overall regional gender parity score can be partially attributed to the 7.7 percentage-point decline on the Political Empowerment subindex, which currently stands at 26.1%. Both the United States and Canada have increased the share of parliamentary positions held by women. However, the measured share of women ministers has dropped significantly – particularly in the United States, where the share declined from 46.2% to 33.3% – which has affected the overall regional score on this subindex. This is partly explained by a stricter definition of what qualifies as a ministerial position being applied in the source database produced by UN Women. See Appendix B for more detail.

Southern Asia

Southern Asia has achieved 63.4% gender parity, the second-lowest score of the eight regions. The score has risen by 1.1 percentage points since the last edition on the basis of the constant sample of countries covered since 2006, which can be partially attributed to the rise in scores of populous countries such as India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Along with Bhutan, these are the countries in this region that have seen an improvement of 0.5 percentage points or more in their scores since the last edition. On the other hand, parity has backslid by 0.5 percentage points or more in Sri Lanka, Afghanistan and Nepal. Bangladesh, Bhutan and Sri Lanka are the best-performing countries in the region, while Pakistan and Afghanistan are at the bottom of both the regional and global ranking tables. At the current rate of progress, full parity will be achieved in 149 years.

Compared to other regions, Southern Asia remains the furthest away from parity on the Economic Participation and Opportunity subindex, having closed 37.2% of the gap. However, based on the constant sample of countries covered since 2006, there has been an improvement of 1.4 percentage points since the last edition. This can be partially attributed to the progress of Pakistan, India and Bangladesh. All three have advanced towards parity on the labour-force participation rate and estimated earned income indicators. On the other hand, parity has receded in the Maldives and Nepal. Bhutan, Sri Lanka and Maldives have the region’s highest parity scores on the Economic Participation and Opportunity subindex, while Pakistan and Afghanistan are the countries that lag the most behind.

Ranking fifth out of eight regions, Southern Asia has closed 96% of the gender gap on the Educational Attainment subindex. India, Sri Lanka and Maldives have the highest regional parity scores, while. Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan and Afghanistan have achieved less than 95% parity. Afghanistan is a negative outlier, having closed only 48.1% of the gender gap. Bangladesh, Bhutan, Sri Lanka and India are either at parity or close to parity in enrolment in secondary education. On enrolment in tertiary education – barring Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan – all countries are at full parity, though levels are low for both men and women.

Southern Asia has the second-lowest regional parity score on the Health and Survival subindex, at 95.3%. Based on the constant sample of countries covered by the index since 2006, that is a 1.1 percentage-point improvement since the last edition. Pakistan, India, the Maldives and Nepal have improved by varying degrees. All four countries have bettered their sex ratios at birth, with Pakistan and India making the most improvement. No country except Sri Lanka has attained full parity in healthy life expectancy.

Similar to other regions, the widest gender gap on the index is on the Political Empowerment subindex. Behind Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, and North America, Southern Asia’s is the fourth-highest score among the eight regions, at 25.1% parity. Based on the constant sample of countries, this is the only subindex for this region that has experienced a setback: there has been a 1% reduction in parity since the last edition. Only the Maldives, Bangladesh and Nepal improved their scores. Parity has backslid in Iran, Sri Lanka and Afghanistan, as the share of ministerial positions held by women has dropped in these countries since 2022. Further, Nepal and Afghanistan have seen negative changes in parity in parliamentary positions, while other countries have not seen much change.

Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa’s parity score is the sixth-highest among the eight regions at 68.2%, ranking above Southern Asia and the Middle East and North Africa. Progress in the region has been uneven. Namibia, Rwanda and South Africa, along with 13 other countries, have closed more than 70% of the overall gender gap. The Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mali and Chad are the lowest-performing countries, with scores below 62%. And while there has been progress of 0.5 percentage points or more in 17 out of 36 countries, scores for 17 countries have seen decline of 0.5 percentage points or more since the last edition. Based on the constant sample, this marks a marginal improvement of 0.1 percentage points. At the current rate of progress, it will take 102 years to close the gender gap in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Sub-Saharan Africa has closed 67.2% of the gender gap on the Economic Participation and Opportunity subindex. Liberia, Eswatini and Burundi are at the top of the ranking table, while Benin, Mali and Senegal have attained the least parity. At the indicator level, there has been an improvement of 0.5 percentage points or more in parity in estimated earned income in 20 out of 36 countries. Further, the share of technical positions assumed by women has increased for more than 1 percentage point in six countries, including populous countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo and Ethiopia. Seven countries – including the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania and Rwanda – have seen greater than 1 percentage-point rise in the share of senior officer positions held by women.

Sub-Saharan Africa is the lowest-ranked region in closing the gender gap on Educational Attainment, with a parity score of 86%, and only Botswana, Lesotho and Namibia have achieved full parity. Sixteen countries have achieved less than 90% parity on this subindex, with the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Chad achieving the lowest scores. There has been an improvement of 0.5 percentage points or more in parity in 23 out of 36 countries, with gains in parity in literacy rate in 23 out of 36 countries. However, the number of countries with 90% or more parity decreases with enrolment in successive levels of education. Apart from Mali, Guinea and Chad, all countries have more than 90% parity in enrolment in primary education, and 16 have reached full parity. Ten countries have less than 90% parity in secondary education and 21 countries less than 90% parity in tertiary education.

Sub-Saharan Africa has the third-highest parity score, 97.2%, on the Health and Survival subindex, following Latin America and the Caribbean and Eurasia and Central Asia. Twenty-five countries have more than 97% parity. Niger, Liberia and Mali are lowest-performing countries on this subindex. All countries have attained parity in sex ratio at birth, and 11 out of 36 countries are at parity for healthy life expectancy.

With five countries having less than 10% parity and five countries with more than 40% parity, progress has been highly uneven when it comes to Political Empowerment. On average across the region, 22.6% parity has been achieved. Based on the constant sample of countries covered on the index since 2006, this is an improvement of 1.1 percentage points compared to the last edition. Nineteen countries, including the populous Nigeria, Ethiopia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, have improved on this subindex by 0.5 percentage points or more. Further, Ethiopia, Togo, Tanzania, Namibia and Uganda currently have heads of states who are women.

In-focus country performances: Top 10 and 15 most populous

This section illustrates the state of country-level gender parity across the four dimensions and sheds light on important dynamics. The share of the global female population represented by the countries discussed in this section is both statistically and strategically significant to monitoring and benchmarking efforts. Based on the data that was officially reported for the period covered in this edition, distinct trends and shifts were observed in the index’s top 10 as well as the 15 most populous countries, 2 which, combined, represent two-thirds of the world’s female population.

Top 10 countries

Iceland continues to incrementally advance towards gender parity since the inaugural 2006 edition and ranks 1st for the 14th consecutive year. Iceland has closed 91.2% of the gender gap, which is 0.4 percentage points higher than the previous edition. The overall gender parity ranking is buoyed by its relatively strong performance across the Political Empowerment and Economic Participation and Opportunity subindexes. Iceland has almost doubled its gender parity score in Political Empowerment since 2006. Iceland has been led by a female head of state for 25 of the last 50 years and more than two-fifth of its ministerial and parliamentary positions are held by women, which has propelled the country to close 90.1% of the gender gap. While Iceland ranks relatively high at 14th (score 79.6%) on the Economic Participation and Opportunity subindex, the gender parity score has suffered setbacks since 2021 (84.6%) and now is closer to its 2017 level. Specifically, parity in wages and in representation among senior officials has declined since 2021. However, since 2006, Iceland maintains parity in the share of women in technical roles. On Health and Survival, parity marginally regresses, partly owing to the 1.5 years decline in the healthy life expectancy of women since the 2020 edition. On Education Attainment (99.1%) Iceland remains almost at parity.

Progress towards gender parity in Norway has been steady, resulting in Norway improving its gender parity score to 87.9% and climbing one rank to the 2nd position in this year’s index. A major part of Norway’s continuous improvement can be ascribed to its achievements on Political Empowerment (score 76.5%), which has increased by 27.1 percentage points since 2006. Women now assume 50% of the ministerial positions and 46.2% of parliamentary positions. Further, the country had a female head of state for 18 of the last 50 years. Norway also reaches parity in enrolment rates in primary education and tertiary education. However, gender parity on the Economic Opportunity and Participation (80%) subindex – though recovered slightly since the last edition – is still 1.8 percentage points below the 2016 level. Since 2016, the gender gap in estimated earned income has shrunk and full parity in technical roles has been achieved and maintained. However, the gender gap in senior roles (score 50.3%) has been widening and its labour-force participation rate (84.5%) is yet to recover since the pandemic hit. Additionally, women’s healthy life expectancy at birth of 71.6 years is still 2.7 years below the 2020 edition, worsening the gap in health attainment by 1.1 percentage point to 96.1% compared to results from the 2020 edition.

After a sharp rebound in gender parity scores between 2017 and 2021, Finland’s progress has been marginal. It advances by 0.3 percentage points since the last edition to register 86.3% parity in the 2023 edition, ranking 3rd globally. Finland maintains its longstanding gender parity on Educational Attainment. The recent tenure of a female head of state and parity at ministerial position boosts parity on Political Empowerment to 70%, which is the fourth highest score on this pillar globally. Yet, progress on Economic Participation and Opportunity (78.3%) seems to be stagnating, marked by slight reversals in parity at senior positions and wage equality since the last edition. However, women have been representing 50% or more of technical positions since the inaugural 2006 edition. On the other hand, like several other high-income economies, 3 the healthy life expectancy of women declined by almost 1.5 years since 2006, partly widening the present gender gap on Health and Survival (97%).

In the last five years, New Zealand has gained more than 5 percentage points to close 85.6% of the overall gender gap, ranking 4th globally in 2023. With parity in parliamentary positions, and a female head of state for 16 of the last 50 years, New Zealand has the world’s third-highest level of parity on Political Empowerment. New Zealand has bridged the gender divide in enrolment across all levels of education and literacy rate. In terms of Economic Participation and Opportunity (73.2%), there remains a 12.5% gender gap in labour-force participation. Estimated earned incomes of both men and women have been increasing since 2006, but men’s income increased at a higher rate than that of women, worsening the gap (score 64.2%) by 4 percentage points since. On Health and Survival, women have lost three years of healthy life expectancy since the 2020 edition, reducing parity on the subindex (score 96.6%).

Sweden maintains its rank of 5th since the last edition; it has closed 81.5% of the gender gap, 0.7 percentage points lower than the 2018 edition. With 46.4% women parliamentarians and 47.8% women ministers who head ministries, Political Empowerment is at 50.3% parity. Parity on Economic Participation and Opportunity (79.5%) has also stagnated recently, and even reversed by 1.7 percentage points since the last edition. The gap in labour-force participation seems to be at a standstill, while parity in estimated earned income declined by 7.3 percentage points since the last edition. On the upside, the share of women in technical positions has remained at more than 50% since the 2006 edition and there has mostly been steady progress in the share of women in senior positions over the last decade. Sweden also achieves a full parity score on Educational Attainment. However, parity in Health and Survival (96.3%) has been sliding because of an almost 1.3 years loss in female healthy life expectancy at birth since the 2020 edition.

Germany sustains its upward trajectory in gender parity, climbing four ranks since last year to 6th position and registering an additional 1.4 percentage points to a score of 81.5%. This advancement is due mainly to the increase of the share of women in parliamentary and ministerial positions, which have boosted the Political Empowerment subindex (63.4%) by 8.4 percentage points since 2022. Germany has also attained parity in enrolment in all levels of education except for secondary education. However, a backslide in parity in wage equality and estimated earned income has depleted the parity on Economic Participation and Opportunity (66.5%) by 6.9 percentage points since 2018. While parity has been achieved and sustained in technical roles, the share of women in senior positions is back at the 2018 level (parity score 41.3%). On Health and Survival, Germany is plateauing at 97.2% parity.

Nicaragua is the highest-ranking Latin American country on the index. It maintains its 7th rank from the last edition and only marginally improves to 81.1% parity. Progress has been plateauing since 2017 on the overall index. Nicaragua has achieved gender parity on Educational Attainment and has been at a standstill at 97.8% parity on the Health and Survival subindex. The share of women in ministerial and parliamentary positions has been surpassing the 50% mark in recent years. However, the overall parity score on Political Empowerment has stagnated, at 62.6% since the last edition. Despite ranking relatively high on the other dimensions, Nicaragua’s performance lags on the Economic Participation and Opportunity subindex, where only 64% parity is attained. The widest gap exists in the share of women in senior positions followed by wage equality.

Ranked 8th is Namibia , the highest-ranking Sub-Saharan African country in this edition, which has attained 80.2% gender parity, a 0.5 percentage-point decline since the last edition. Namibia has achieved full parity on both the Health and Survival and Educational Attainment subindexes, although their absolute levels of attainment are low for both women and men. With 56% of technical workers and 43.6% of senior officers being women, Economic Participation and Opportunity is at 78.4% parity and is ranked 19th globally. However, after a phase of rapid and broad-based increase in economic parity up until 2018, parity has been flagging. This is mostly due to a 4.8 percentage-point decline in parity in estimated earned income and 2 percentage-point decline in parity in labour-force participation rate since 2018. Namibia has achieved 44.3% parity in Political Empowerment with 44.2% women parliamentarians, 31.6% women ministers and a female prime minister in power since 2015.

Lithuania re-enters the top 10 and ascends two ranks since the 2022 edition to 9th position. The parity score at 80.0%, is 0.1 percentage point higher than previous edition. Lithuania’s improvement in its gender parity profile after 2020 can be attributed to the surge in share of women in parliamentary positions and electing a female prime minister, resulting in 46.6% parity on the Political Empowerment subindex. Lithuania has covered 76.7% of the gender gap on the Economic Participation and Opportunity subindex. This dimension is however marked by mixed performance across the indicators. While parity has backtracked in senior positions and estimated earned income since 2022, full party in technical roles has been sustained, and perceptions of wage equality for similar jobs have improved by 0.2 percentage points. For Educational Attainment (98.9%) and Health and Survival (98%), Lithuania edges towards parity.

The newest entrant to the top 10 is Belgium at 10th position. It has closed 79.6% of the overall gender gap, indicating a recovery of 5.7 percentage points since 2017. Most of the development is on the Political Empowerment subindex, where it has reached full parity in ministerial positions and women in 42.7% of parliamentary seats, marking significant improvements since 2017. Further, Belgium remains at parity on Educational Attainment. Perception of wage equality for similar jobs and share of women in senior positions have also been increasing incrementally, and parity has been achieved in technical roles. Overall, 72.8% of the gender gap is closed on Economic Participation and Opportunity subindex. However, a decline in gender parity in healthy life expectancy since 2017 has been gradually depleting its parity in the Health and Survival subindex (96.8%).

15 most populous countries

China ranks 107th and has achieved 67.8% gender parity. Compared to the previous edition, this represents an 0.4 percentage-point decline in score and a decline of five positions in rank. China is at 93.5% parity on Educational Attainment, with full parity on tertiary education. On Economic Participation and Opportunity, China has closed 72.7% of the gender gap and attains 81.5% parity in labour-force participation rate. It also secures 11.4% parity on Political Empowerment, with 4.2% women ministers and 24.9% women parliamentarians. China continues to have one of the lowest sex ratios at birth (89%), affecting parity levels on the Health and Survival subindex (93.7%, 145th).

India has closed 64.3% of the overall gender gap, ranking 127th on the global index. It has improved by 1.4 percentage points and eight positions since the last edition, marking a partial recovery towards its 2019 (66.8%) parity level. The country has attained parity in enrolment across all levels of education. However, it has reached only 36.7% parity on Economic Participation and Opportunity. On the one hand, there are upticks in parity in wages and income; on the other hand, the shares of women in senior positions and technical roles have dropped slightly since the last edition. On Political Empowerment, India has registered 25.3% parity, with women representing 15.1% of parliamentarians, the highest for India since the inaugural 2006 edition. On the Health and Survival index (95%), the improvement in sex ratio at birth by 1.9 percentage points to 92.7% has driven up parity after more than a decade of slow progress.

Ranked 43rd, the United States has closed 74.8% of its overall gender gap. On Educational Attainment, the country is at parity or virtually at parity across all levels of education except secondary education. On the Economic Participation and Opportunity subindex (78%), the United States has recovered almost to its 2018 level of parity. Income parity (67.5%) has been gradually improving, however the share of women in senior positions has been receding over the last two editions of the index. Further, over the last decade, women’s healthy life expectancy has declined by five years and men’s by close to three years. This has worsened gender parity in Health and Survival outcomes (97%) by 0.9 percentage points since the 2013 edition. The country’s parity on Political Empowerment stands at 24.8%, with a marginal improvement in the share of women parliamentarians and still no female head of state.

Indonesia ’s gender parity scores were improving steadily until they dropped in 2021. In this edition, Indonesia (87th) maintains the same 69.7% score as last year, sustaining a recovery to almost match its 2020 parity level. On Economic Participation and Opportunity, there is 66.6% parity, indicating a partial recovery to its 2020 parity level (68.5%). Since 2020, the share of women senior officials has dropped from 55% to 31.7%, while the share of technical workers has increased from 40.1% to more than 50%, thus attaining parity. Further, there has been marginal improvement in parity in estimated earned income, though the gap remains wide: for every dollar of income earned by a man, a woman earns just 51.9 cents. The Political Empowerment subindex is at 18.1% parity, with 21.6% women parliamentarians and 20.7% women ministers. Parity across Educational Attainment (97.2%) and Health and Survival (97%) remain virtually unchanged compared to the 2022 edition.

Pakistan (142nd) is at 57.5% parity, its highest since 2006. It has improved by 5.1 percentage points on the Economic Participation and Opportunity subindex in the last decade to attain 36.2% parity, though this level of parity remains one of the lowest globally. There is broad progress across all indicators on this subindex, but particularly in the share of women technical workers and the achievement of parity in wage equality for similar work. Despite relatively high disparities, parity in literacy rate and enrolment in secondary and tertiary education are gradually advancing, leading to 82.5% parity on the Educational Attainment subindex. On Health and Survival, Pakistan secures parity in sex ratio at birth, boosting subindex parity by 1.7 percentage points since 2022. Like most other countries, Pakistan’s widest gender gap is on Political Empowerment (15.2%). It has had a female head of state for 4.7 years of the last 50 years, and one-tenth of the ministers as well as one-fifth of parliamentarians are women.

Brazil’s parity at 72.6% is 57th globally and at its highest parity level since 2006. Brazil has appointed women in 36.7% of ministerial positions, the highest in its history. Further, there has also been a 2.9 percentage-point increase in women parliamentarians (share, 17.7%). Combined, they have almost doubled the parity level on Political Empowerment (26.3%) since the previous edition. There has also been marginal improvement on the Economic Participation and Opportunity dimension. While parity in technical positions is sustained, parity in estimated incomes is at 62.8%, despite registering some improvement compared to the 2022 edition. There is full parity in Health and Survival outcomes, based on sex ratio at birth and healthy life expectancy. On the Educational Attainment subindex (99.2%), apart from enrolment in primary education, there is full gender parity in literacy rate, secondary education and tertiary education.

Nigeria’s parity is at 63.7% (130th), 1 percentage point lower than its 2013 level. Since then, parity on the Political Empowerment subindex has receded from 11.9% to 4.1%, due to a decline in parity in both parliamentary and ministerial positions. Further, parity on Educational Attainment has been fluctuating in recent years and has only marginally improved over the last decade; currently, its 82.6% parity is one of the lowest in the world. Its absolute levels of women’s literacy rates and enrolment rates across levels of education have also been lagging. Nigeria has perfect parity for sex ratio at birth, which has contributed to a 96.7% parity on the Health and Survival subindex. Further, with a global ranking of 54th, its Economic Participation and Opportunity score (71.5%) has experienced both advances and setbacks over the last decade. Nigeria has more than 64% representation of women in senior positions, but women earn only 50% of the income earned by men.

With the highest gender parity in Southern Asia, Bangladesh ranks 59th globally, with a score of 72.2%. The country’s trajectory is mostly characterized by continuous progress on Political Empowerment. At 55.2% parity, Bangladesh ranks seventh globally on this subindex. It has had a woman head of state for 29.3 years out of the last 50 years, the longest duration in the world. However, its shares of women in ministerial (10%) and parliamentary positions (20.9%) are relatively low. On Health and Survival (96.2%), there is parity in sex ratio at birth. However, gender parity in healthy life expectancy has been dropping as men’s life expectancy has been increasing faster than that of women since the 2020 edition. Bangladesh’s Educational Attainment parity is at 93.6%. Both women and men’s literacy rate and enrolment in secondary and tertiary education has been increasing steadily over the last decade. While there is now full parity in enrolment in secondary education, for literacy rate and enrolment in tertiary education, there remains a persistent gap. At 43.8% parity, Bangladesh’s Economic Participation and Opportunity subindex performance is one of the lowest globally (139th). However, this marks a recovery to its 2020 parity level. Improvement in the estimated earned income since 2021 edition has helped drive this recovery, as the gaps across the other indicators show less change.

Ranked 33rd, Mexico’s 76.5% parity is 0.1 percentage points better than the previous edition, though its rank drops by two positions. On Educational Attainment, Mexico is close to subindex parity, with full parity in enrolment in secondary and tertiary education and 98.4% parity in literacy rate. Despite this, there is persistent gender disparity in labour-force participation (57.6%), and women’s estimated earned income is only 52.3% of that of men. Further, only 38.5% of senior officers are women. However, women represent almost half of the country’s technical workers. Overall, Mexico’s 60.1% parity on Economic Participation and Opportunity stands at 110th globally. On Health and Survival, women have lost 2.4 years and men have lost 1.5 years of healthy life expectancy since the 2020 edition, widening the subindex gender gap by 0.4 percentage points (97.5%). With parity in parliamentary positions, 42.1% women ministers and no woman head of state yet, the Political Empowerment subindex is at 49% parity, the same as the last edition.

Japan’s parity declines slightly for the second consecutive year since the 2021 edition. With a parity of 64.7% (125th), it has slipped 0.25 percentage points compared to the previous editions and now stands nine positions lower in the rankings. Japan’s parity in Political Empowerment at 5.7% is one of the lowest in the world (ranking 138th). Ten percent of its parliamentary positions and 8.3% of ministerial positions are held by women, while there has not been any female head of state. There is almost full parity on both the Educational Attainment and Health and Survival subindexes. There has been 1.1% improvement in parity at estimated earned income since the last edition; 54.2% of women are in the labour force and 12.9% of senior officers are women. Japan’s Economic Participation and Opportunity parity is at 56.1% and ranks 123rd out of 146 countries.

Ethiopia ranks 75th, having closed 71.1% of the gender gap. Compared to the previous edition, it has improved by 0.6 percentage points. Ethiopia has had a woman president the past 4.35 years, along with 41.3% incumbent woman parliamentarians and 40.9% women ministers. This results in a closing 43.1% of the gender gap on the Political Empowerment subindex, almost triple its score since a decade back (14.6% in 2013). On Health and Survival, Ethiopia is close to parity (97.1%). By contrast, on Educational Attainment, though parity across the indicators is gradually improving, Ethiopia has one of the lowest parity levels globally (135th) at 85.4%. After some fluctuations, parity on Economic Participation and Opportunity is also low, at 58.7%. Labour-force participation parity is at 72.7% and women earn 66.1% of men’s estimated earned income. Only 25.4% of senior officers and 34.3% of technical positions are held by women.

The Philippines has achieved 79.1% gender parity and ranks 16th globally. Despite an improvement of three positions and 0.88 percentage points since last year, this is only a partial recovery towards its 2018 parity level (79.9%). With 26% women cabinet ministers, the Philippines has recovered on that indicator. However, the gap widened in the share of parliamentarians who are women (37.6% parity), thus effectively decreasing overall parity on the Political Empowerment subindex (40.9%) by 0.7 percentage points since 2018. The Philippines is almost at parity on Educational Attainment (99.9%). After being close to parity on Health and Survival since 2006, the country has regressed on this subindex (96.8%) due to a slight decline in sex ratio at birth. On Economic Participation and Opportunity, the Philippines maintains full parity in senior officer and technical workers, though women’s income is just 71.6% that of men.

Egypt is at 62.6% parity and ranks 134th. Egypt advanced towards parity between the 2017 editions (60.8%) and 2021 editions (63.9%), before regressing for the subsequent 2022 (63.5%) and the current edition. Since 2021, there has been a 3 percentage-point decline in parity on the Educational Attainment subindex, due to slight backslides in parity in enrolment in secondary and tertiary education. At 96.8% parity, Health and survival remains virtually unchanged. However, on Economic Participation and Opportunity, a 6.8 percentage-point increase in the share of women in senior officer (share 12.4%) and a 4.3 percentage-point increase in the share of women in technical positions (35.1%) since the 2022 edition have boosted subindex parity by 1.7 percentage points to 42%. Further, with 27.5% women parliamentarians and 18.8% women ministers, there is 17.5% parity on Political Empowerment.

Viet Nam , with a score of 71.1% and a global rank of 72nd, continues its gradual progress towards gender parity. It has progressed by 2.3 percentage points since 2007 (score 68.9%) when it was first covered. As compared to the last edition, it has advanced by 0.62 percentage points as well as 11 positions in rank. While the 2022 edition reported no female ministers, there are now 11.1% women ministers, driving up the parity score on the Political Empowerment subindex from 13.5% to 16.6%. Viet Nam’s sex ratio at birth has been one of the country’s lowest-performing indicators and it suffered further setbacks, worsening the Health and Survival parity by 0.4 percentage points to 94.6%, which is among the lowest in the world. On Educational Attainment, Viet Nam is at 98.5% parity. There is also full parity in the share of women as technical workers, and women earn 81.4% of men’s estimated earned income. Labour-force participation parity is at 88.1%, though only 25.6% of the senior officials are women. Overall, Viet Nam is at 74.9% parity on the Economic Participation and Opportunity subindex.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo ranks 140th, with 61.2% of the gender gap closed. This is a 3 percentage-point improvement since 2018 when the country was first included in the index. Most of this improvement can be attributed to its progress on the Economic Participation and Opportunity and Political Empowerment subindexes. The country has advanced its parity in estimated earned income, senior officials and technical workers. Further, on the Political Empowerment subindex, the share of women in parliamentary and ministerial positions has also risen since the 2018 edition. The other dimension where the Democratic Republic of the Congo has advanced is Educational Attainment (68.3% parity), although it still ranks among the lowest (144th) globally. This increase is driven by progress in parity in literacy rate and enrolment in secondary education. On Health and Survival, the country has achieved full parity in sex ratio at birth, attaining 97.6% subindex parity.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Gender pay gap in U.S. hasn’t changed much in two decades

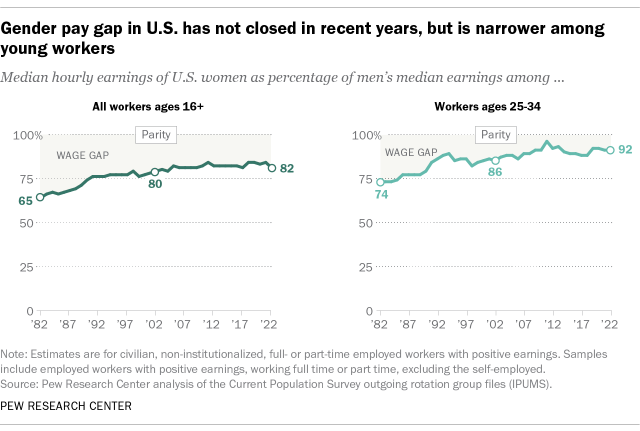

The gender gap in pay has remained relatively stable in the United States over the past 20 years or so. In 2022, women earned an average of 82% of what men earned, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of median hourly earnings of both full- and part-time workers. These results are similar to where the pay gap stood in 2002, when women earned 80% as much as men.

As has long been the case, the wage gap is smaller for workers ages 25 to 34 than for all workers 16 and older. In 2022, women ages 25 to 34 earned an average of 92 cents for every dollar earned by a man in the same age group – an 8-cent gap. By comparison, the gender pay gap among workers of all ages that year was 18 cents.

While the gender pay gap has not changed much in the last two decades, it has narrowed considerably when looking at the longer term, both among all workers ages 16 and older and among those ages 25 to 34. The estimated 18-cent gender pay gap among all workers in 2022 was down from 35 cents in 1982. And the 8-cent gap among workers ages 25 to 34 in 2022 was down from a 26-cent gap four decades earlier.

The gender pay gap measures the difference in median hourly earnings between men and women who work full or part time in the United States. Pew Research Center’s estimate of the pay gap is based on an analysis of Current Population Survey (CPS) monthly outgoing rotation group files ( IPUMS ) from January 1982 to December 2022, combined to create annual files. To understand how we calculate the gender pay gap, read our 2013 post, “How Pew Research Center measured the gender pay gap.”

The COVID-19 outbreak affected data collection efforts by the U.S. government in its surveys, especially in 2020 and 2021, limiting in-person data collection and affecting response rates. It is possible that some measures of economic outcomes and how they vary across demographic groups are affected by these changes in data collection.

In addition to findings about the gender wage gap, this analysis includes information from a Pew Research Center survey about the perceived reasons for the pay gap, as well as the pressures and career goals of U.S. men and women. The survey was conducted among 5,098 adults and includes a subset of questions asked only for 2,048 adults who are employed part time or full time, from Oct. 10-16, 2022. Everyone who took part is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Here are the questions used in this analysis, along with responses, and its methodology .

The U.S. Census Bureau has also analyzed the gender pay gap, though its analysis looks only at full-time workers (as opposed to full- and part-time workers). In 2021, full-time, year-round working women earned 84% of what their male counterparts earned, on average, according to the Census Bureau’s most recent analysis.

Much of the gender pay gap has been explained by measurable factors such as educational attainment, occupational segregation and work experience. The narrowing of the gap over the long term is attributable in large part to gains women have made in each of these dimensions.

Related: The Enduring Grip of the Gender Pay Gap

Even though women have increased their presence in higher-paying jobs traditionally dominated by men, such as professional and managerial positions, women as a whole continue to be overrepresented in lower-paying occupations relative to their share of the workforce. This may contribute to gender differences in pay.

Other factors that are difficult to measure, including gender discrimination, may also contribute to the ongoing wage discrepancy.

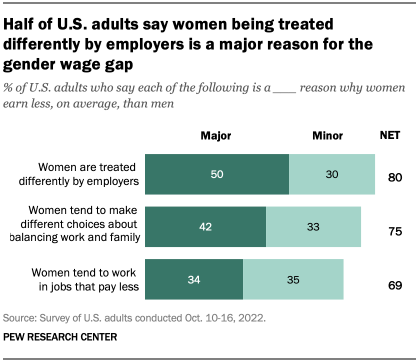

Perceived reasons for the gender wage gap

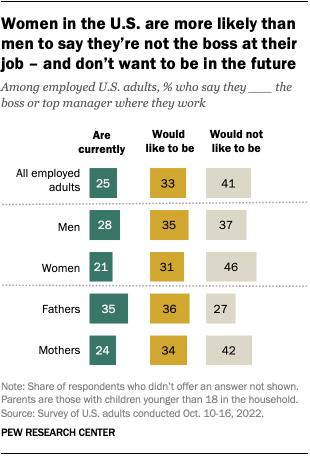

When asked about the factors that may play a role in the gender wage gap, half of U.S. adults point to women being treated differently by employers as a major reason, according to a Pew Research Center survey conducted in October 2022. Smaller shares point to women making different choices about how to balance work and family (42%) and working in jobs that pay less (34%).

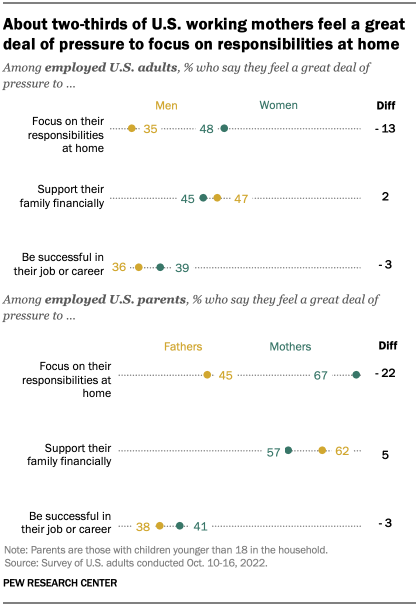

There are some notable differences between men and women in views of what’s behind the gender wage gap. Women are much more likely than men (61% vs. 37%) to say a major reason for the gap is that employers treat women differently. And while 45% of women say a major factor is that women make different choices about how to balance work and family, men are slightly less likely to hold that view (40% say this).

Parents with children younger than 18 in the household are more likely than those who don’t have young kids at home (48% vs. 40%) to say a major reason for the pay gap is the choices that women make about how to balance family and work. On this question, differences by parental status are evident among both men and women.

Views about reasons for the gender wage gap also differ by party. About two-thirds of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (68%) say a major factor behind wage differences is that employers treat women differently, but far fewer Republicans and Republican leaners (30%) say the same. Conversely, Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say women’s choices about how to balance family and work (50% vs. 36%) and their tendency to work in jobs that pay less (39% vs. 30%) are major reasons why women earn less than men.