Importance of Religious Tolerance Essay

Introduction, hindu-buddhism, chinese religions, abraham monotheism.

Religious tolerance is imperative in modern societies because it allows people with separate faiths, beliefs or values to coexist with one another. Acknowledgment of the validity of other people’s religions requires placing these different religions in their traditional contexts in order to understand them.

Furthermore, understanding the history of other cultures allows one to appreciate how similar experiences led to different conceptual systems. One must realize that people created their belief systems in order to make sense of their worlds or the chaos around them. Therefore, every religion is reflective of the culture and history of its followers.

In order to become religiously tolerant, one must familiarize oneself with the history of this religion. The Hindu pattern is again evidence of the fact that all religions are depictions of the experiences of the people involved and the conceptual systems that they deduced from them.

The Hindu religion has more than one holy text, more than one religious authority, several deities, theological systems and understandings of morality. Adherents of this religion are highly tolerant because of its henotheistic nature. Nonetheless, most followers still believe in one Supreme Being who manifests his powers through different divinities.

Central aspects of Hinduism include Vishnu (the preserver), Brahma (the creator) and Shiva (the destroyer). Belief in the cycle of life i.e. the Samsara is central to the teaching of these adherents. However, it is possible for one to achieve enlightenment and thus escape this cycle. Many assert that one’s present life stems from the consequences of one’s past life.

This religion has four major doctrines that include dharma (righteousness in religion), artha (economic success) and kama (sense gratification) and nivritti (renunciation of the world). The latter is achieved through renunciation of the world in a process called moksha. Mankind’s supreme goal is to reach moksha.

Therefore, moksha is a solution of samsara. It is derived from the Buddhist faith. Doctrines from the latter religion were crucial in resolving complications in this religion. All these concepts can be traced back to the history of the Hindu religion. By dissecting the experiences of the Hindu people, one can understand why they came to follow their present practices and this should foster religious tolerance among non Hindus (Esposito et al., 2002).

The Hindu religion began as far back as 4000 BCE in the Indus Valley. It began with the Indus valley culture, which was held by native Indians. Thereafter, some Aryan tribes from Central Asia and Europe entered India and introduced Vedism. Since their immigration was done slowly or in waves (according to recent scholarly discoveries), most natives easily took up the Aryan religious with ease. This explains how the latter religion started amalgamating different belief systems. The Vedic belief system underwent various changes between 900 and 500 BCE. At first, the religion began with an emphasis on sacrificial rites. Emphasis was on perfecting people’s performance of the rites. However with time, some intellectuals decided that focusing too much on the rites instead of the wisdom associated with them was wrong.

They were called the Upanishads, and they introduced the focus on total dissociation from society in order to reach ultimate spirituality. They challenged the original structures of the Vedic religion because the latter was highly organized around sacrifices and priestly rituals. The priests who performed these rites were called Brahmans. They represented the capacity of the human to possess divine power.

When the Upanishads introduced their concept of total detachment from society or moksha, the Brahmans felt that this would threaten the organization of their society. As a result, they proposed a middle way in which one could strive towards moksha but still maintain the social hierarchies in society. It should be noted that the priestly class of the Brahmans arose earlier on in the Vedic faith because of some fire rituals that the Vedic believers carried out.

These rituals yielded successful results and led to the belief that their priests had a superior status. The Upanishads wanted to internalize the ritualistic process, hence their shift to the individual. This belief in developing the spiritual self led to the acceptance of moksha as a solution towards the problem of cyclical life (Fallows, 1998).

Thus far, one can appreciate why Hinduism has a hierarchical system that places the priestly class above all others. This was a way of preserving order in their society. One can also appreciate why the religion appears to be polytheistic. The god of fire and other gods were manifestations of a supreme being. One can also comprehend why these adherents believe in moksha; it provides them with a mechanism for solving the problems of this life.

It also gives them something to aspire to or work towards. This small history, therefore, heightens religious tolerance because it places these belief systems in context and establishes the experiences that led to their development. Some of them were social (entry of the Aryans into the Hindu culture), others were intellectual (internalizing rituals) while others were economic (preservation of social order for material prosperity).

In China, some people practice Taoism, others Confucianism and others believe in Buddhism. Certain followers combine elements of all three faiths. The experiences of members of these cultures also provide important insights concerning the influence of people’s experiences in the development of their belief system. By placing those occurrences in context, one can then gain religious tolerance of adherents of these faiths even though one does not ascribe to any of them.

In Confucianism, most adherents believe that social harmony is the most important goal (Hopfe & Woodward, 2004). This school of thought was started by Confucius. He lived at a time when his society was struggling with the reinforcement of laws. Confucius thought about the ineffectiveness of coercive laws.

People simply followed them without really understanding them. This meant that the method was reactive rather than proactive. The intellectual proposed that if people internalized behaviors before acting, then they would act in an appropriate manner. In this regard, they would abide by their mutual obligations, and thus prevent the occurrence of disorder in that society.

Confucius, therefore, created the concept of mutual relationships and the need to respect one another. From this small history, one can understand why loyalty, etiquette and humanness are so important in the Confucian faith today. It was an attempt at creating social harmony by ensuring that everyone understood his place. Through education and personal effort, it was possible for people to become better.

In the Taoist school of thought, it is held that the ideal way of life is to accept things as they are. When one resists nature, then one actually causes things to get worse. It is in line with this thinking that Taoists believe in the Ying and Yang.

One represents the strong and hard force and the other represents the soft and feminine force. Therefore, by finding a balance between these forces in the universe, then calmness will prevail. The Taoist faith came after the Confucian school of thought. Confucianism taught about personal involvement and striving to become better.

However, subsequent intellectuals realized that they needed a new way of thinking that promoted greater peace and harmony. They lived at a time when there was too much active striving as seen in the warring era. Therefore, it was imperative to introduce the concept of yielding to nature. In this school of thought, it was argued that there was a force of life called Tao that flows everywhere.

One’s major goal was to be in harmony with the Tao. Through the use compassion, moderation and humiliation, one can develop important virtues. Most problems arise when one tries to fight or interfere with the Tao by acting in opposition to nature. One must strive to find answers within through meditation. The story of the emergence of Taoism demonstrates that experiences are crucial to the formation of one’s belief systems.

It was a response to the challenges of Confucianism and the social upheavals it had created. Too much active strive led to war in that community; this prompted an alternative way of thinking. Once again, one can become tolerant to this religion by realizing that it was a natural creation of the political and social problems of that time. Taoism complemented Confucianism in this society. In fact, many individuals abide by the principles of both these faiths.

They epitomize religious tolerance because they understand that belief systems carry a certain purpose in one’s society or one’s history. The same reasoning allows one to understand why Buddhism plays an important role in the Chinese society as well as many others in Asia. It is philosophical in nature and has generated minimal conflict with other faiths hence its acceptance (Keown, 1996).

Judaism, Islam, and Christianity are the three main religions that have come to be associated with Abraham monotheism. A large part of Christian scriptures have been adopted from the Jewish faith. Similarly, many parts of the Islamic faith have stories or portions from the Jewish scriptures. In order to enhance religious tolerance, it is imperative to look at the history of the formation of these faiths in order to understand why their adherents hold the beliefs that they do.

Judaism is a religion in which people believe that they have a special relationship with God. This stems from the fact that they are a chosen people, having descended from Abraham. God gave them a gift of laws called the Torah to assist in maintaining their relationship with him and with one another.

The Jews have been misunderstood by many as a ritualistic and legalistic religion as seen through their scriptures, which are called Torah (interpreted as laws). In order to negate these misunderstandings, one must understand why the Jews called their scriptures the Torah.

The Jews think of themselves as God’s special people. It is believed that in order to promote harmony with God, they needed some guidance. Also, God needed to give them a commentary on how they could act towards one another; this was the reason why he gave them the guidance of the Torah.

Therefore, one can become tolerant of this religion by understanding the origin of their ritualistic practices. Judaism is also a religion that is highly diverse. The diversity stems from some cultural and theological experiences of members of this religion. Some individuals resettled along the Mediterranean or other parts of Europe and thus created their own version of the religion.

Conversely, some individuals understood the rituals and religious practices differently. These theological differences led to the birth of reconstructionists, reform Jews, Liberal Jews, Orthodox and Conservative Jews. Therefore, a cultural dissection of the Jewish religious system allows one to understand it. In this regard, one can accept adherents of the faith based on the premise that their history and their values led them to that place.

Christianity is the most predominant faith in the world today. In the US, most citizens associate themselves with some form of Christianity. It is still necessary to understand the development of Christianity in order to foster tolerance among the various sects if one happens to be a Christian or to build tolerance for non Christians.

The Christian faith began when Jesus of Nazareth was born in Jerusalem; a Jewish community. He was regarded as the incarnation of God as he was his son. This was seen through the fulfillment of prophecy as well as his life on earth – he performed miracles and did other divine things.

After he died and resurrected, the first Christian church officially began. Therefore, for non Christians, it is possible to understand why Christians focus on Jesus; they believe that he was God living amongst men. Furthermore, Christianity is monotheistic because having such a supreme being is the only consistent way to understand what their Holy Scriptures say about nature and the universe.

Religious tolerance can be effectively promoted when one understands the experiences and the history of the people who abide by them. Hindu-Buddhism, Chinese religions and Abraham Monotheism all emanated from a series of events or encounters that shaped those faith systems.

Some issues were political such as the warring states in China and Taoism; others were social such as the need to stick to certain social structures as in Hinduism. In essence different experiences led to different conceptual frameworks hence religions. It is this statement that makes religious tolerance possible.

Esposito, J. Fasching, D. and Lewis, T. (2002). World Religions Today . Oxford: OUP

Fallows, W. (1998). Religions East and West . Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace Publishers

Hopfe, M. & Woodward, R. (2004). Religions of the World . London: Pearson-Prentice hall

Keown, D. (1996). Buddhism: a very short introduction . Oxford: Oxford University press

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, June 19). Importance of Religious Tolerance Essay. https://ivypanda.com/essays/religious-tolerance/

"Importance of Religious Tolerance Essay." IvyPanda , 19 June 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/religious-tolerance/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Importance of Religious Tolerance Essay'. 19 June.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Importance of Religious Tolerance Essay." June 19, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/religious-tolerance/.

1. IvyPanda . "Importance of Religious Tolerance Essay." June 19, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/religious-tolerance/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Importance of Religious Tolerance Essay." June 19, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/religious-tolerance/.

- Vedic Religion Analysis and Interpretation

- Religion Doctrines: Moksha and Salvation

- Vedic Hinduism, Classical Hinduism, and Buddhism: A Uniting Belief Systems

- Confucianism and Taoism

- Taoism: Growth of Religion

- Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism Elements

- Torah and Qur'an: The Laws and Ethical Norms

- Taoism: The Origin and Basic Beliefs

- Salvation and Self in Hinduism and Theravada Buddhism

- The Comparison of Buddhism and Taoism Philosophies

- Navigating Religious Beliefs in the Workplace

- Dr. Baxter's video lecture Response paper

- The Divine Life Church

- Role of Religion in Public Life (Church and State)

- Religion in America: Past, Present, and Future

America’s True History of Religious Tolerance

The idea that the United States has always been a bastion of religious freedom is reassuring—and utterly at odds with the historical record

Kenneth C. Davis

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Presence-God-Country-Bible-Riots-631.jpg)

Wading into the controversy surrounding an Islamic center planned for a site near New York City’s Ground Zero memorial this past August, President Obama declared: “This is America. And our commitment to religious freedom must be unshakeable. The principle that people of all faiths are welcome in this country and that they will not be treated differently by their government is essential to who we are.” In doing so, he paid homage to a vision that politicians and preachers have extolled for more than two centuries—that America historically has been a place of religious tolerance. It was a sentiment George Washington voiced shortly after taking the oath of office just a few blocks from Ground Zero.

But is it so?

In the storybook version most of us learned in school, the Pilgrims came to America aboard the Mayflower in search of religious freedom in 1620. The Puritans soon followed, for the same reason. Ever since these religious dissidents arrived at their shining “city upon a hill,” as their governor John Winthrop called it, millions from around the world have done the same, coming to an America where they found a welcome melting pot in which everyone was free to practice his or her own faith.

The problem is that this tidy narrative is an American myth. The real story of religion in America’s past is an often awkward, frequently embarrassing and occasionally bloody tale that most civics books and high-school texts either paper over or shunt to the side. And much of the recent conversation about America’s ideal of religious freedom has paid lip service to this comforting tableau.

From the earliest arrival of Europeans on America’s shores, religion has often been a cudgel, used to discriminate, suppress and even kill the foreign, the “heretic” and the “unbeliever”—including the “heathen” natives already here. Moreover, while it is true that the vast majority of early-generation Americans were Christian, the pitched battles between various Protestant sects and, more explosively, between Protestants and Catholics, present an unavoidable contradiction to the widely held notion that America is a “Christian nation.”

First, a little overlooked history: the initial encounter between Europeans in the future United States came with the establishment of a Huguenot (French Protestant) colony in 1564 at Fort Caroline (near modern Jacksonville, Florida). More than half a century before the Mayflower set sail, French pilgrims had come to America in search of religious freedom.

The Spanish had other ideas. In 1565, they established a forward operating base at St. Augustine and proceeded to wipe out the Fort Caroline colony. The Spanish commander, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, wrote to the Spanish King Philip II that he had “hanged all those we had found in [Fort Caroline] because...they were scattering the odious Lutheran doctrine in these Provinces.” When hundreds of survivors of a shipwrecked French fleet washed up on the beaches of Florida, they were put to the sword, beside a river the Spanish called Matanzas (“slaughters”). In other words, the first encounter between European Christians in America ended in a blood bath.

The much-ballyhooed arrival of the Pilgrims and Puritans in New England in the early 1600s was indeed a response to persecution that these religious dissenters had experienced in England. But the Puritan fathers of the Massachusetts Bay Colony did not countenance tolerance of opposing religious views. Their “city upon a hill” was a theocracy that brooked no dissent, religious or political.

The most famous dissidents within the Puritan community, Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson, were banished following disagreements over theology and policy. From Puritan Boston’s earliest days, Catholics (“Papists”) were anathema and were banned from the colonies, along with other non-Puritans. Four Quakers were hanged in Boston between 1659 and 1661 for persistently returning to the city to stand up for their beliefs.

Throughout the colonial era, Anglo-American antipathy toward Catholics—especially French and Spanish Catholics—was pronounced and often reflected in the sermons of such famous clerics as Cotton Mather and in statutes that discriminated against Catholics in matters of property and voting. Anti-Catholic feelings even contributed to the revolutionary mood in America after King George III extended an olive branch to French Catholics in Canada with the Quebec Act of 1774, which recognized their religion.

When George Washington dispatched Benedict Arnold on a mission to court French Canadians’ support for the American Revolution in 1775, he cautioned Arnold not to let their religion get in the way. “Prudence, policy and a true Christian Spirit,” Washington advised, “will lead us to look with compassion upon their errors, without insulting them.” (After Arnold betrayed the American cause, he publicly cited America’s alliance with Catholic France as one of his reasons for doing so.)

In newly independent America, there was a crazy quilt of state laws regarding religion. In Massachusetts, only Christians were allowed to hold public office, and Catholics were allowed to do so only after renouncing papal authority. In 1777, New York State’s constitution banned Catholics from public office (and would do so until 1806). In Maryland, Catholics had full civil rights, but Jews did not. Delaware required an oath affirming belief in the Trinity. Several states, including Massachusetts and South Carolina, had official, state-supported churches.

In 1779, as Virginia’s governor, Thomas Jefferson had drafted a bill that guaranteed legal equality for citizens of all religions—including those of no religion—in the state. It was around then that Jefferson famously wrote, “But it does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods or no God. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.” But Jefferson’s plan did not advance—until after Patrick (“Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death”) Henry introduced a bill in 1784 calling for state support for “teachers of the Christian religion.”

Future President James Madison stepped into the breach. In a carefully argued essay titled “Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments,” the soon-to-be father of the Constitution eloquently laid out reasons why the state had no business supporting Christian instruction. Signed by some 2,000 Virginians, Madison’s argument became a fundamental piece of American political philosophy, a ringing endorsement of the secular state that “should be as familiar to students of American history as the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution,” as Susan Jacoby has written in Freethinkers , her excellent history of American secularism.

Among Madison’s 15 points was his declaration that “the Religion then of every man must be left to the conviction and conscience of every...man to exercise it as these may dictate. This right is in its nature an inalienable right.”

Madison also made a point that any believer of any religion should understand: that the government sanction of a religion was, in essence, a threat to religion. “Who does not see,” he wrote, “that the same authority which can establish Christianity, in exclusion of all other Religions, may establish with the same ease any particular sect of Christians, in exclusion of all other Sects?” Madison was writing from his memory of Baptist ministers being arrested in his native Virginia.

As a Christian, Madison also noted that Christianity had spread in the face of persecution from worldly powers, not with their help. Christianity, he contended, “disavows a dependence on the powers of this world...for it is known that this Religion both existed and flourished, not only without the support of human laws, but in spite of every opposition from them.”

Recognizing the idea of America as a refuge for the protester or rebel, Madison also argued that Henry’s proposal was “a departure from that generous policy, which offering an Asylum to the persecuted and oppressed of every Nation and Religion, promised a lustre to our country.”

After long debate, Patrick Henry’s bill was defeated, with the opposition outnumbering supporters 12 to 1. Instead, the Virginia legislature took up Jefferson’s plan for the separation of church and state. In 1786, the Virginia Act for Establishing Religious Freedom, modified somewhat from Jefferson’s original draft, became law. The act is one of three accomplishments Jefferson included on his tombstone, along with writing the Declaration and founding the University of Virginia. (He omitted his presidency of the United States.) After the bill was passed, Jefferson proudly wrote that the law “meant to comprehend, within the mantle of its protection, the Jew, the Gentile, the Christian and the Mahometan, the Hindoo and Infidel of every denomination.”

Madison wanted Jefferson’s view to become the law of the land when he went to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. And as framed in Philadelphia that year, the U.S. Constitution clearly stated in Article VI that federal elective and appointed officials “shall be bound by Oath or Affirmation, to support this Constitution, but no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States.”

This passage—along with the facts that the Constitution does not mention God or a deity (except for a pro forma “year of our Lord” date) and that its very first amendment forbids Congress from making laws that would infringe of the free exercise of religion—attests to the founders’ resolve that America be a secular republic. The men who fought the Revolution may have thanked Providence and attended church regularly—or not. But they also fought a war against a country in which the head of state was the head of the church. Knowing well the history of religious warfare that led to America’s settlement, they clearly understood both the dangers of that system and of sectarian conflict.

It was the recognition of that divisive past by the founders—notably Washington, Jefferson, Adams and Madison—that secured America as a secular republic. As president, Washington wrote in 1790: “All possess alike liberty of conscience and immunity of citizenship. ...For happily the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens.”

He was addressing the members of America’s oldest synagogue, the Touro Synagogue in Newport, Rhode Island (where his letter is read aloud every August). In closing, he wrote specifically to the Jews a phrase that applies to Muslims as well: “May the children of the Stock of Abraham, who dwell in this land, continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other inhabitants, while every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and figtree, and there shall be none to make him afraid.”

As for Adams and Jefferson, they would disagree vehemently over policy, but on the question of religious freedom they were united. “In their seventies,” Jacoby writes, “with a friendship that had survived serious political conflicts, Adams and Jefferson could look back with satisfaction on what they both considered their greatest achievement—their role in establishing a secular government whose legislators would never be required, or permitted, to rule on the legality of theological views.”

Late in his life, James Madison wrote a letter summarizing his views: “And I have no doubt that every new example, will succeed, as every past one has done, in shewing that religion & Govt. will both exist in greater purity, the less they are mixed together.”

While some of America’s early leaders were models of virtuous tolerance, American attitudes were slow to change. The anti-Catholicism of America’s Calvinist past found new voice in the 19th century. The belief widely held and preached by some of the most prominent ministers in America was that Catholics would, if permitted, turn America over to the pope. Anti-Catholic venom was part of the typical American school day, along with Bible readings. In Massachusetts, a convent—coincidentally near the site of the Bunker Hill Monument—was burned to the ground in 1834 by an anti-Catholic mob incited by reports that young women were being abused in the convent school. In Philadelphia, the City of Brotherly Love, anti-Catholic sentiment, combined with the country’s anti-immigrant mood, fueled the Bible Riots of 1844, in which houses were torched, two Catholic churches were destroyed and at least 20 people were killed.

At about the same time, Joseph Smith founded a new American religion—and soon met with the wrath of the mainstream Protestant majority. In 1832, a mob tarred and feathered him, marking the beginning of a long battle between Christian America and Smith’s Mormonism. In October 1838, after a series of conflicts over land and religious tension, Missouri Governor Lilburn Boggs ordered that all Mormons be expelled from his state. Three days later, rogue militiamen massacred 17 church members, including children, at the Mormon settlement of Haun’s Mill. In 1844, a mob murdered Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum while they were jailed in Carthage, Illinois. No one was ever convicted of the crime.

Even as late as 1960, Catholic presidential candidate John F. Kennedy felt compelled to make a major speech declaring that his loyalty was to America, not the pope. (And as recently as the 2008 Republican primary campaign, Mormon candidate Mitt Romney felt compelled to address the suspicions still directed toward the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.) Of course, America’s anti-Semitism was practiced institutionally as well as socially for decades. With the great threat of “godless” Communism looming in the 1950s, the country’s fear of atheism also reached new heights.

America can still be, as Madison perceived the nation in 1785, “an Asylum to the persecuted and oppressed of every Nation and Religion.” But recognizing that deep religious discord has been part of America’s social DNA is a healthy and necessary step. When we acknowledge that dark past, perhaps the nation will return to that “promised...lustre” of which Madison so grandiloquently wrote.

Kenneth C. Davis is the author of Don’t Know Much About History and A Nation Rising , among other books.

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

Religious Literacy Resource Guide: Defining and Measuring Religious Tolerance

- Video Resources

- Organizational Resources

- Professional Development

- Teaching About Religion in Public Schools

- Muslim Communities in America

- Lived Religion Abroad

- Jewish Communities in America

- Christian Communities in America

- Religious Diversity in America

- Defining and Measuring Religious Tolerance

- Sociological and Historical Approaches

- Critique and Reflections

- Application and Lived Experiences

- 9/11 Educator's Toolkit

- Resources for Racial Justice

- Religious Diversity and Tolerance in the University Setting

- Religious Diversity and Tolerance in the Workplace

- Maps This link opens in a new window

Textual Resources

More Journal Articles

- Ferrar, Jane. “ The Dimensions of Tolerance.” The Pacific Sociological Review 19.1 (1976): 63-81.

Though tolerance is often treated as a unidimensional concept, there are at least three components of tolerance: extent of approval, extent of permission, and origins of belief. This paper explains why these dimensions should be examined separately, rather than fused together as they are in much of the tolerance literature.

- Francis, L. J., & Kay, W. K. " Attitude Towards Religion: Definition, Measurement and Evaluation ." British Journal of Educational Studies 32.1 (1984): 45–50.

This paper reexamines the issues introduced in Greer's "Attitude Toward Religion Reconsidered"—definition, measurement, and evaluation of attitudes toward religion—in order to come to more positive conclusions about religious attitudes and attitudes towards religion.

Journal Articles

- Gibson, J. L., & Bingham, R. D. “ On the Conceptualization and Measurement of Political Tolerance ." The American Political Science Review 76.3 (1982): 603–620.

This article presents a new approach to measuring political tolerance, with scales measuring support for freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and freedom of political association, in hopes that they will serve as better predictors of opinions and behaviors in actual disputes.

- Gibson, J. L. “ Alternative Measures of Political Tolerance: Must Tolerance be "Least-Liked"? " American Journal of Political Science 36.2 (1992): 560–577.

This article considers how to measure political intolerance. The traditional Stouffer-based measure of intolerance is compared to the Sullivan, Piereson, and Marcus "least-liked" measure using data from a national survey. The traditional predictors of intolerance perform very similarly irrespective of which of the tolerance measures is used. Future tolerance research can profitably utilize either measurement approach.

- Newman, Jay. “ The Idea of Religious Tolerance .” American Philosophical Quarterly 15.3 (1978): 187-195.

There are many obstacles to religious tolerance, but we often overlook the most basic obstacle: few people have a clear idea of what religious tolerance is. This essay illuminates the nebulous concept of religious tolerance in depth in hopes that reason will inform the good will of people hoping to practice tolerance.

- " Prospects for Inter-Religious Understanding ." Pew Research Center, 2006.

This analysis suggests that the tensions that once existed between Protestants and Catholics, and the hostility that Jews faced from both groups, have largely diminished in America. These findings strongly suggest that the United States has the capacity to overcome historical religious divisions and prejudices.

- << Previous: Academic Perspectives on Tolerance

- Next: Sociological and Historical Approaches >>

- Last Updated: May 20, 2022 12:48 PM

- URL: https://libguides.rice.edu/religious_literacy

- Donate Today

- Access Lesson Plans LOG IN or SIGN UP

- Mission & Awards

- Testimonials

- American History & Western Civilization Challenge Bowl

- Miracle of America

- America’s Heritage: An Adventure in Liberty

- America’s Heritage: An Experiment in Self-Government

- American Heritage Month

- Seminars & Teacher Workshops

- The Founding Blog

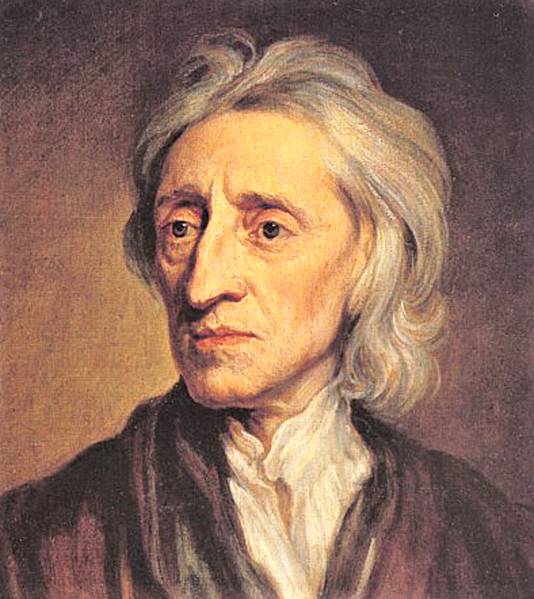

Philosopher John Locke & His Letters Concerning Toleration

Portrait of John Locke by Sir Godfrey Kneller, 1697.

British Enlightenment philosopher, physician, and civil servant John Locke—later influential to the American Founders and the Declaration of Independence—was a relatively early proponent of religious tolerance and freedom of belief. While known as a secular thinker of the Enlightenment era, Locke asserted a remarkably similar, Bible-based position as American colonizers Roger Williams, who wrote The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution for the Cause of Conscience in 1644, and William Penn, who wrote The Great Case of Liberty of Conscience Debated and Defended by the Authority of Reason, Scripture, and Antiquity in 1670, on the issues of freedom of belief and religious tolerance.

Locke, who attended Oxford University in England, favored the use of man’s reason to search for and understand truth in life and society. This rational search was, he believed, part of man’s God-given purpose. His sensible views may have influenced his support for tolerance as necessary in man’s search for truth.

In 1669, Locke wrote the constitution for the colony of Carolina in America which notably allowed for freedom of belief despite having an official state church. Carolina’s state church was more tolerant than those in other colonies like Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Virginia. Alongside the tolerant colonies of Rhode Island (founded by Roger Williams in 1643), Maryland (founded by George and Cecil Calvert in 1634), and Pennsylvania (founded by William Penn in 1681); Carolina demonstrated a more moderate but important move toward tolerance in early America.

A Letter Concerning Toleration , 1689, by John Locke

In the wake of the Protestant Reformation and religious persecution in England and Europe, Locke wrote a series of letters supporting toleration—his 1689 Letter Concerning Toleration , 1690 Second Letter Concerning Toleration , and 1692 Third Letter Concerning Toleration —in defense of religious tolerance from a Bible-based viewpoint. He argued that freedom of belief was a God-given, natural right and that regulation of religion should be outside the realm of civil government. Since only God can ascertain religious truth and judge a person’s faith, government’s imposition on religious belief and practice is unauthorized and ineffective. Moreover, freedom is the only means by which people can arrive at genuine Christian faith. Locke notably believed that truth—in his mind, the Christian Gospel—can prevail amidst other ideas. In his 1707 Paraphrase and Notes on the Epistles of St. Paul , he defended tolerance as an aspect of Christian charity or love. In his 1695 The Reasonableness of Christianity , he argued that the teachings of Christianity are compatible with reason.

Locke’s Bible-based writings on freedom of belief and religious tolerance, so reminiscent of Williams and Penn, influenced the views of many in England and colonial America. His first Letter likely influenced the English Toleration Act of 1689 which gave freedom of worship to Protestant non-conformists who dissented from the Church of England yet pledged allegiance to Britain. Locke’s first Letter was also studied by many American Founders and informed their approach to and support for religious freedom in the new nation of the United States.

Contributed by AHEF and Angela E. Kamrath.

—–

Source for more information: Kamrath, Angela E. The Miracle of America: The Influence of the Bible on the Founding History and Principles of the United States of America for a People of Every Belief . Second Edition. Houston, TX: American Heritage Education Foundation, 2014, 2015.

Additional Reading/Handout: Why Religious Freedom Became an Unalienable Right & First Freedom in America by Angela E. Kamrath, American Heritage Education Foundation. Paper available to download from member resources, americanheritage.org .

Related posts/videos: 1. An Introduction t o Popular Sovereignty 2. Challenges in the Early Puritan Colonies: The Dilemma of Religious Laws and Dissent 3. The Two Kingdoms Doctrine : Religious Reformers Recognize the Civil and Spiritual Kingdom 4. The First Experiments in Freedom of Belief & Religious Tolerance in America 5. Roger Williams: His Quest for Religious Purity and Founding of Rhode Island 6. Roger Williams: First Call for Separation of Church and State in America 7. William Penn and His “Holy Experiment” in Religious Tolerance 8. Early Americans supported Religious Tolerance based on God as Judge of Conscience 9. Early Americans opposed Religious Persecution as contrary to the Biblical Teachings of Christ . 10. Early Americans argued Religious Coercion opposes Order of Nature 11. Early Americans Believed Religious Coercion Opposes Reason 12. Early Americans Supported Religious Tolerance within Civil Peace and Order 13. The Religious Landscape of the Thirteen Colonies in Early 1700s America

Activity: Miracle of America High School Teacher Course Guide, Unit 4, Part 2 of 2, Activity 7: A Closer Look at Locke, p. 147-8. MS-HS.

A Closer Look at Locke

Purpose/Objective: Students learn about the arguments & works of John Locke who influenced the tolerant colony of Carolina and the views/arguments of the American Founders in support of religious freedom in the United States.

Suggested Readings: 1) Chapter 4 of Miracle of America sourcebook/text. Students read sections 4.1, 4.5, 4.6, 4.8, 4.10, 4.12, 4.15, 4.18. 2) Letters Concerning Toleration by John Locke (three letters). 3) Paper/handout titled Why Religious Freedom Became an Unalienable Right & First Freedom in America by Angela E. Kamrath (AHEF). Paper available to download from member resources, americanheritage.org . 4) Related Blog: What were the first experiments in freedom of belief and religious tolerance in America?

Activity: 1) Text Analysis. Students read selected excerpt(s) from Miracle of America text and Locke’s Letters Concerning Toleration . Students working individually or in pairs, recap in writing the main ideas and Biblical references in the selections. They may use an outline format, two-column notes, or graphic organizer as needed/directed. The teacher may prepare students for the reading with a review of vocabulary/terms in reading. As an alternative, additional text analysis, have students rephrase and discuss two or more quotes from Locke. For example:

“The care of souls cannot belong to the civil magistrate, because his power consists only in outward force. True and saving religion consists in the inward persuasion of the mind, without which nothing can be acceptable to God. Such is the nature of understanding, that it cannot be compelled by outward force.”

2) Short Paragraph Test. Students think about, write on, and/or discuss the following questions below in small groups/whole class. Students may use this activity as test preparation for a short-answer test on the same or similar questions: a. What main points from the Bible and other sources were used by Locke to argue against religious coercion and in support of religious tolerance and freedom of belief? b. How does Locke argue that religious coercion opposes reason?

To download this whole unit, sign up as an AHEF member (no cost) to access the “resources” page on americanheritage.org . To order the printed binder format of the course guide with all the units, go to the AHEF bookstore .

Copyright © American Heritage Education Foundation. All rights reserved.

Dr. Danilo Petranovich is an Advising Scholar for AHEF. Dr. Petranovich is the Director of the Abigail Adams Institute at Harvard University in Cambridge, MA. Previously, he taught political science at Duke University and Yale University. His scholarly expertise is in nineteenth-century European and American political and social thought, with a special emphasis on American culture and Abraham Lincoln. He has authored a number of articles on Lincoln and is currently writing a book on nationalism and the North in antebellum America. He is a member of Harvard’s Kirkland House. He holds a B. A. from Harvard and a Ph. D. in Political Science from Yale University.

Dr. Richard J. Gonzalez (1912-1998) is Co-Founder of AHEF. Dr. Gonzalez served as Chief Economist and a member of the Board of Directors for Humble Oil and Refining Company (later Exxon Mobil) in Houston, Texas, for 28 years. Later, he served as an economic consultant to various federal agencies and studies including the Department of Defense and the National Energy Study.

He consulted with the Petroleum Administration for Defense and the Office of Defense Mobilization. In 1970, he was appointed by the U. S. Secretary of the Interior to the National Energy Study. In addition, Gonzalez chaired and directed many petroleum industry boards and committees. He served as director of the National Industrial Conference Board, chairman of the Economics Advisory Committee-Interstate Oil Compact Commission, and chairman of the National Petroleum Council Drafting Committee on National Oil Policy. Gonzalez also held visiting professorships at the University of Texas, University of Houston, University of New Mexico, Stanford University, and Northwestern University. From 1983-1991, he was a Senior Research Fellow at the University of Texas IC2 Institute (Innovation, Creativity, and Capital).

Gonzalez authored many articles and papers on topics ranging from energy economics to the role of progress in America. His articles include “Economics of the Mineral Industry” (1976), “Energy and the Environment: A Risk Benefit Approach” (1976), “Exploration and Economics of the Petroleum Industry” (1976), “Exploration for U. S. Oil and Gas” (1977), “National Energy Security” (1978), and “How Can U.S. Energy Production Be Increased?” (1979).

Born in San Antonio, Texas, Gonzalez earned his B.A. in Mathematics, M.A. in Economics, and Ph.D. in Economics (Phi Beta Kappa with highest honors) from the University of Texas at Austin. He was and still is the youngest candidate ever to earn his Ph.D. from UT-Austin at the age of 21 in 1934.

In 1993, Dr. and Mrs. Gonzalez were recognized by the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution (NSSAR) with the Bronze Good Citizenship Medals for “Notable Services on Behalf of American Principles.”

Selected Articles: 1. “What Makes America Great? An Address before the Dallas Chapter Society for the Advancement of Management” (1951) 2. “Power for Progress” (1952) 3. “Increasing Importance of Economic Education” (1953) 4. “Federal Spending and Deficits Must Be Controlled to Stop Inflation” (1978) 5. “What Enabled Americans to Achieve Great Progress? Keys to Remarkable Economic Progress of the United States of America” (1989) 6. “The Establishment of the United States of America” (1991)

Eugenie Gonzalez is Co-Founder of AHEF. Mrs. Gonzalez was elected to the Houston Independent School District (HISD) Board of Trustees with Dr. Herman Barnett III and David Lopez from 1972-1976 and was a key designer and advocate for HISD’s Magnet School program. With HISD and AHEF in 1993, she designed and implemented HISD’s annual American Heritage Month held every November throughout HISD.

Jeannie was recognized in 1993 by the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution (NSSAR) for “Notable Services on Behalf of American Principles” with the Bronze Good Citizenship Medal and in 2011 by the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution (NSDAR) for “Outstanding Achievement through Education Pursuits” with the Mary Smith Lockwood Medal. In 2004, she was honored to receive HISD’s first American Heritage Month Exemplary Citizenship Award.

Jeannie was a volunteer, participant, and supporter of M. D. Anderson Cancer Hospital, St. Luke’s United Methodist Church, Gethsemane United Methodist Church, Houston Grand Jury Association (board member), League of Women Voters, Houston Area Forum, the Mayor’s Charter Study Committee, Vision America, Houston Parks Department, and Houston Tennis Association. She was instrumental in the founding of the Houston Tennis Association and Houston Tennis Patrons.

In her youth, Jeannie was the leading women’s tennis player in the Midwest Section of the US Lawn Tennis Association and competed at the U. S. National Championships. She attended by invitation and became the first women’s tennis player at the University of Texas at Austin. In 1932, 1933, and 1934, Jeannie was women’s finalist at the Houston Invitational Tennis Tournament which became the River Oaks Invitational Tennis Tournament and is now the USTA Clay Court Championships. She was instrumental in bringing some of the nation’s top amateur tennis players to that event. Jeannie became the first teaching tennis professional at Houston Country Club and River Oaks Country Club, starting active junior programs at each. Jeannie and her father, Jack Sampson, were jointly inducted into the Texas Tennis Hall of Fame in 2012.

Claudine Kamrath is Outreach Coordinator, Office Manager, and Resource Designer for AHEF. She oversees outreach efforts and office administration. She also collaborates on educational resource formatting and design. She has served as an Elementary Art Teacher in Texas as well as a Communications and Design Manager for West University United Methodist Church in Houston. She also worked as a childrens’ Camp Counselor at St. Luke’s United Methodist Church in Houston. She holds a B.A. in Art and a Bachelor of Fine Art from the University of Texas at Austin as well as Texas Teacher Certification from the University of Houston. She has served in various children’s and student ministries.

Dr. Brian Domitrovic is an Advising Scholar for AHEF. Dr. Domitrovic is a Senior Associate and the Richard S. Strong Scholar at the Laffer Center for Supply-Side Economics. He is also Department Chair and Professor of History at Same Houston State University. He teaches American and European History and Economics. His specialties also include Economic History, Intellectual History, Monetary Policy, and Fiscal Policy. He has written articles, papers, and books–including Econoclasts –in these subjects. He is a board member of the Center for Western Civilization, Thought & Policy at the University of Colorado-Boulder and a trustee of the Philadelphia Society. He has received several awards including the Director’s Award from Intercollegiate Studies Institute and fellowship grants from Earhart Foundation, Krupp Foundation, Princeton, Texas A&M, and SHSU. He holds a B. A. in History & Mathematics from Columbia University, an M. A. in History from Harvard University, and a Ph. D. in History, with graduate studies in Economics, from Harvard University.

Jack Kamrath is Co-Founder and Vice-President of AHEF. A Texas state champion and nationally-ranked tennis player during his high school and college years, Kamrath is the Co-Founder and Principal of Tennis Planning Consultants (TPC) in Houston, Texas, since 1970. TPC is the first, oldest, and most prolific tennis facility design and consulting firm in the United States and world. Mr. Kamrath is also the founder and owner of Kamrath Construction Company and has owned and managed various real estate operating companies. He worked with Brown and Root in construction and human resources in Vietnam during the Vietnam War from 1966-1970. He holds a Bachelor of Business Administration from the University of Texas at Austin. He is a member of St. Luke’s United Methodist Church in Houston. In 2008, AHEF President Mr. Kamrath and AHEF received the Distinguished Patriot Award from the Society of the Sons of the American Revolution (NSSAR) for leadership in preserving America’s heritage and the teaching of good citizenship principles.

Essays: 1. 1776: From Oppression to Freedom 2. FUPR: The Formula for the American Experiment 2. In Support of Our Pledge of Allegiance 3. A Summation of America’s Greatest Ever Threat to Its Survival and Perpetuation 4. A Brief Overview: The Moral Dimension of Rule of Law in the U. S. Constitution (editor)

Dr. Michael Owens is Director of Education of AHEF. He has served as a Presenter/Trainer of AHEF teacher training workshops. Owens has taken on a number of administration leadership roles in Texas public education throughout his career–including Superintendent in Dripping Springs ISD, Assistant Superintendent in Friendswood ISD, and Associate Executive Director of Instruction Services for Region IV Education Service Center. He has also served as Director of Exemplary Programs for the Texas Education Agency, Director of Curriculum and Instruction for College Station ISD, and Director of Elementary and Secondary Education for College Station ISD. Owens has led many professional development worships for the Texas School Boards Association, Texas Assessment, Texas Education Agency, and others. He has specialization in educational technology systems and educational assessments, and has Texas teaching experience. He currently serves as Texas Technology Engineering Literacy (TEL) test administrator for the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) for part of Texas. He holds a B.S. and a M.Ed. from Stephen F. Austin State University and a Ed.D. from the University of North Texas. He retired in 2021.

Angela E. Kamrath is President and Editorial Director of AHEF. She is the author of the critically-acclaimed The Miracle of America: The Influence of the Bible on the Founding History and Principles of the United States of America for a People of Every Belief . She is editor and co-contributor of AHEF’s widely-distributed teacher resources, America’s Heritage: An Adventure in Liberty , America’s Heritage: An Experiment in Self-Government , and The Miracle of America High School Teacher Course Guide . In addition, she is editor and contributor for The Founding Blog and AHEF websites. Kamrath has taught, tutored, and consulted in writing and research at the University of Houston, Belhaven College, and Houston Christian University. She also served as a Secondary English Teacher in Texas and as a Communications Assistant for St. Luke’s United Methodist Church in Houston. She served as a Research Assistant intern in the Office of National Service during the George H. W. Bush administration. She holds a B.A. in Government from the University of Texas at Austin, a M.A. in Journalism from Regent University, and a M.Ed. in Curriculum and Instruction as well as Texas Teacher Certification from the University of Houston. She has served in various children’s and student ministries.

Dr. Steve Balch is an Advising Scholar for AHEF. Dr. Balch is the Principal Founder and former President of the National Association of Scholars (NAS). He served as a Professor of Government at City University of New York from 1974-1987. Dr. Balch has co-authored several NAS studies on education curriculum evolution and problems including The Dissolution of General Education: 1914-1993 , The Dissolution of the Curriculum 1914-1996 , and The Vanishing West . He is the author of Economic and Political Change After Crisis: Prospects for Government, Liberty and Rule of Law and numerous articles relating to issues in academia. Dr. Balch has also founded and/or led many education organizations including the Institute for the Study of Western Civilization at Texas Tech University, Alexander Hamilton Institute for the Study of Western Civilization, Association for the Study of Free Institutions, American Academy for Liberal Education, Philadelphia Society, Historical Society, and Association of Literary Scholars. He has also served on the National Advisory Board of the U. S. Department of Education’s Fund for the Improvement of Post-Secondary Education (FIPSE), Educational Excellence Network, and New Jersey State Advisory Committee to the U. S. Commission on Civil Rights. Dr. Balch was awarded the National Humanities Medal by President George W. Bush in 2007, and the Jeanne Jordan Kirkpatrick Academic Freedom Award by the Bradley Foundation and American Conservative Union Foundation in 2009. He holds a B. A. in Political Science from City University of New York and a M. A. and Ph. D. in Political Science from the University of California-Berkeley.

Dr. Rob Koons is an Advising Scholar for AHEF. Dr. Koons is a Professor of Philosophy and Co-Founder of The Western Civilization and American Institutions Program at The University of Texas at Austin. He teaches ancient, medieval, contemporary Christian, and political philosophy as well as philosophy of religion. He has authored/co-authored countless articles and several books including Realism Regained , The Atlas of Reality, Fundamentals of Metaphysics, and Neo-Aristotelian Perspectives on Contemporary Science . He has been awarded numerous fellowships and is a member of the American Philosophical Association, Society of Christian Philosophers, and American Catholic Philosophical Association. He holds a B. A. in Philosophy from Michigan State University, an M. A. in Philosophy and Theology from Oxford University, and a Ph. D. in Philosophy from the University of California-Los Angeles (UCLA).

Dr. Mark David Hall is an Advising Scholar for AHEF. Dr. Hall is a Professor of Political Science in the Robertson School of Government at Regent University and a Senior Research Fellow in the Center for Religion, Culture & Democracy at First Liberty Institute. He is also a Distinguished Scholar of Christianity & Public Life at George Fox University, Associate Faculty in the Center for the Study of Law and Religion at Emory University, and Senior Fellow in the Institute for Studies of Religion at Baylor University. His teaching interests include American Political Theory, Religion and Politics, Constitutional Law, and Great Books. Dr. Hall is a nationally recognized expert on religious freedom and has written or edited a dozen books on religion and politics in America including Proclaim Liberty Throughout All the Land: How Christianity Has Advanced Freedom and Equality for All Americans , Did America Have a Christian Founding? Separating Modern Myth from Historical Truth , Great Christian Jurists in American History , America’s Wars: A Just War Perspective , Faith and the Founders of the American Republic , The Sacred Rights of Conscience , The Founders on God and Government , and The Political and Legal Philosophy of James Wilson . He writes for the online publications Law & Liberty and Intercollegiate Studies Review and has appeared regularly on a number of radio shows, including Jerry Newcomb’s Truth in Action, Tim Wildman’s Today’s Issues, the Janet Mefferd Show, and the Michael Medved Show. He has been awarded numerous fellowships and the Freedom Project Award by the John Templeton Foundation in 1999 and 2000. He holds a B. A. in Political Science from Wheaton College and a Ph. D. in Government from the University of Virginia.

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

- Get New Issue Alerts

- American Academy of Arts and Sciences

on religious diversity & tolerance

Philip L. Quinn, a Fellow of the American Academy since 2003, was John A. O’Brien Professor of Philosophy at Notre Dame University. An expert on the philosophy of religion, he wrote on the Augustinian legacy, the virtue of obedience, and the ethics of Søren Kierkegaard. He was the author of “Divine Commands and Moral Requirements” (1978) and coeditor of “A Companion to Philosophy of Religion” (1997). This is the last work Professor Quinn completed before his death on November 13, 2004.

Since September 11, 2001, the fragility of tolerance has become a source of acute anxiety in scholarly reflection on religion–as shown by some of the contributions to the Summer 2003 issue of Dædalus on secularism and religion. In that context, James Carroll asked how it was possible for people committed to democracy to embrace religious creeds that underwrite intolerance. Daniel C. Tosteson identified conflicting religious beliefs as a particularly serious cause of the plague of war.

Such anxieties are reasonable. After all, Osama bin Laden professes to fight in the name of Islam. And in the aftermath of 9/11, the United States has experienced a significant rise in reported incidents of intolerant behavior directed at Muslims.

Moreover, tolerance has long been under assault in more limited conflicts fueled in part by religious differences. Religious disagreement has been a cause of violence in Belfast, Beirut, and Bosnia during recent decades. The terrorism of Al Qaeda threatens to project the religious strife involved in such localized clashes onto a global stage. In short, early in the twenty-first century, the practice of tolerance is in peril, and religious diversity is a major source of the danger.

During the past two decades, diversity has also been a topic of lively discussion among philosophers and theologians. What philosophers have found especially challenging about religious diversity is an epistemological problem it poses. Here the philosophical debates have focused primarily on the so-called world religions–Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Though most of the philosophers involved in these debates have not addressed the topic of tolerance directly, there is a clear connection between the epistemological problems posed by religious belief and the political problems posed by religious diversity.

Take the case of Christianity. One way to justify a Christian’s belief in God is the arguments offered by natural theologians for the existence of God. Another source of justification is distinctively Christian religious experiences, including both the spectacular experiences reported by mystical virtuosi and the more mundane experiences that pervade the lives of many ordinary Christians. A third source is the divine revelation Christians purport to find in canonical scripture. And, for many Christians, a fourth source is the authoritative teaching of a church believed to be guided by the Holy Spirit. When combined, such sources constitute a cumulative case for the rationality of the belief in God professed by most Christians.

Let us suppose, if only for the sake of argument, that these sources provide sufficient justification to ensure the rational acceptability of the Christian belief system. But this will be so only if there are no countervailing considerations or sources that present conflicting evidence. Before we can render a final verdict on the rational acceptability of that belief system, challenges to the Christian worldview must be taken into account. One of the most famous challenges is, of course, the existence of evil. The sheer diversity of religions and religious beliefs presents an equally vexing challenge. And the growth of religiously pluralistic societies, global media, and transportation channels has rendered this challenge increasingly salient in recent times.

A Christian today who is sufficiently aware of religious diversity will realize that other world religions also have impressive sources of justification: They too can mobilize powerful philosophical arguments for the fundamental doctrines of their worldviews. They are supported by rich experiential traditions. They also contain both texts and authoritative individuals or institutions that profess to teach deep lessons about paths to salvation or liberation from the ills of the human condition.

Yet quite a few of the distinctive claims of the Christian belief system, understood in traditional ways, conflict with central doctrines of other world religions. Though each world religion derives justification from its own sources, at most one of them can be completely true. Each religion is therefore an unvanquished rival of all the rest.

To be sure, Christian sources yield reasons to believe that the Christian worldview is closer to the truth than its rivals. But many of these reasons are internal to the Christian perspective. Each of the other competitors can derive from its sources internal reasons for thinking it has the best access to truth. Adjudication of the competition without begging the question would require reasons independent of the rival perspectives. It seems that agreement on independent reasons sufficient to adjudicate the rivalry is currently well beyond our grasp.

It is clear that this unresolved conflict will have a negative impact on the level of justification Christian belief derives from its sources. In his magisterial book Perceiving God (1991), William Alston investigated the matter of justification for the Christian practice of forming beliefs about God’s manifestations to believers. He argued persuasively that the unresolved conflict does not drop the level of justification for beliefs resulting from this practice below the threshold minimally sufficient for rational acceptability. He acknowledged, however, that the level of justification for such Christian beliefs is considerably lowered by the conflict, and that similar conclusions hold, mutatis mutandis , for analogous experiential practices in other world religions.

A generalization from the special case seems to be in order. For those Christians who are sufficiently aware of religious diversity, the justification that the distinctively Christian worldview receives from all its sources is a good deal less than would be the case were there no such diversity, even if the level of justification for the Christian belief system were not on that account reduced below the threshold for rational acceptability. And, other things being equal, the same goes for other world religions. This reduction of justification across the board can contribute to a philosophical strategy for defending religious toleration.

The basic idea is not new. The strategy is implicitly at work in a famous example discussed by Immanuel Kant in his Religion within the Boundaries of Mere Reason (1793). Kant asks the reader to consider an inquisitor who must judge someone, otherwise a good citizen, charged with heresy. The inquisitor thinks a supernaturally revealed divine command permits him to extirpate “unbelief together with the unbelievers.” Kant suggests that the inquisitor might take such a command to be revealed in the parable of the great feast in Luke’s Gospel. According to the parable, when invited guests fail to show up for the feast and poor folk brought in from the neighborhood do not fill the empty places, the angry host orders a servant to go out into the roads and lanes and compel people to come in (Luke 14: 23). Kant wonders whether it is rationally acceptable for the inquisitor to conclude, on grounds such as this, that it is permissible for him to condemn the heretic to death.

Kant holds that it is not. As he sees it, it is certainly wrong to take a person’s life on account of her religious faith, unless the divine will, revealed in some extraordinary fashion, has decreed otherwise. But it cannot be certain that such a revelation has occurred. If the inquisitor relies on sources such as the parable, uncertainty arises from the possibility that error may have crept into the human transmission or interpretation of the story. Moreover, even if it were to seem that such a revelation came directly from God, as in the story told in Genesis 22 of God’s command to Abraham to kill Isaac, the inquisitor still could not be certain that the source of the command really was God.

For Kant, certainty is an epistemic concept. It is a matter of having a very high degree of justification, not a question of psychological strength of belief. Thus his argumentative strategy may be rendered explicit in the following way: All of us, even the inquisitor, have a very high degree of justification for the moral principle that it is generally wrong to kill people because of their religious beliefs. Our justification for this principle vastly exceeds the threshold for rational acceptability. It may be conceded to religious believers that there would be an exception to this general rule if there were divine command to the contrary. However, none of us, not even the inquisitor, can have enough justification for the claim that God has issued such a command to elevate that claim above the threshold for rational acceptability. Hence it is not rationally acceptable for the inquisitor to conclude that condemning a heretic to death is morally permissible.

No doubt, almost all of us will recoil with horror from the extreme form of persecution involved in Kant’s famous example. Other cases may not elicit the same kind of easy agreement.

Suppose the leaders of the established church of a certain nation insist that God wills that all children who reside within the nation’s borders are to receive education in that orthodox faith. No other form of public religious education is to be tolerated. These leaders are not so naive as to imagine that the policy of mandatory religious education they propose will completely eradicate heresy. But they argue that its enactment is likely to lower the numbers of those who fall away from orthodoxy and, hence, to reduce the risk of the faithful being seduced into heresy. And they go on to contend that the costs associated with their policy are worth paying, since what is at stake is nothing less than the eternal salvation of the nation’s people.

The claim that God has commanded mandatory education in orthodoxy might, it seems, derive a good deal of justification from sources recognized by members of the established church. It is the sort of thing a good God, deeply concerned about the salvation of human beings, might favor. Perhaps the parable about compelling people to come in could, with some plausibility, be interpreted as an expression of such a command. So if the challenge of religious diversity were not taken into consideration, the claim that God commands mandatory education in orthodoxy might derive enough justification from various sources to put it above the threshold for rational acceptability for members of the established church. But the factoring in of religious diversity may be enough to lower the claim’s justification below that threshold, thereby rendering it rationally unacceptable even for members of the church who are sufficiently aware of such diversity. And an appeal to the epistemological consequences of religious diversity may be the only factor capable of performing this function in numerous instances. Thus such an appeal may be an essential component of a successful strategy for arguing against forms of intolerance less atrocious than extirpating “unbelief together with the unbelievers.”

Of course, the strategy being suggested here is no panacea. It is not guaranteed to vindicate the full range of tolerant practices found in contemporary liberal democracies; it may fail to show that the religious claims on which citizens ground opposition to tolerant practices fall short of rational acceptability by their own best lights. This is because the strategy must be employed on a case-by-case basis. However, such a piecemeal strategy has some advantages. It does not impose on defenders of tolerance the apparently impossible task of showing that the whole belief system of any world religion falls short of rational acceptability according to standards to which the adherents of that religion are committed. It targets for criticism only individual claims made within particular religions, claims that are often sharply disputed in those religions by believers themselves.

Nor can this strategy be expected to convert all religious zealots to tolerant modes of behavior. All too often religious zealots turn out to be fanatics who will not be moved by any appeal to reason. But in any event, the strategy should not be faulted because it cannot do something that no philosophical argument for tolerance, or for any other practice, could possibly do.

Religious diversity must be counted among the causes of the great ills of intolerance. It also happily shows some promise of contributing to a remedy for the very malady it has helped to create.

Home / Essay Samples / Religion / Religious Tolerance

Religious Tolerance Essay Examples

Religious pluralism: equality of all world religions.

Religious pluralism is a widely discussed view of religion and is very present in today’s society, and some may even say that it is present now more than at any other time in the history of Western civilization. John Hick, a philosopher of religion and...

The Connection Between Religion and Culture

Religion and culture are deeply interconnected, often influencing and shaping each other in significant ways. This essay will explore the relationship between religion and culture, discussing how they intersect and influence one another. Religion is an integral part of human culture. It encompasses beliefs, rituals,...

Religious Intolerance: a Barrier to Unity and Understanding

Religious intolerance, marked by prejudice and hostility toward individuals or groups based on their religious beliefs, stands as a significant challenge to social harmony and global progress. This phenomenon, often fueled by misunderstandings and fear, undermines the principles of empathy, respect, and coexistence that are...

Impact of Religion on the Lives of Its Followers

Religion holds a significant place in human society, influencing various aspects of individuals' lives. From shaping beliefs and values to guiding daily practices and providing a sense of purpose, religion has a profound impact on its followers. This essay explores the ways in which religion...

Discovering the Concept of Inculturation in the Religion

It is a dialogue whereby faith and culture are talking together. It is also adopting of liturgy to different cultures and find a common goal to work together. The bible also teaches us that inculturation also took place at the time of Apostle Paul when...

Religious Conflict in the New World

Religious tolerance has always been a topic that fascinates me, raising probing questions which I can’t easily answer. One aspect that has regularly confused me is the one discussed in this article: why America is seen as an example of freedom of worship when in...

The American Model of Religion: the Adoption of Religious Pluralism and the Problems of the 'True Believers'

In regards to the American model of religion, Magagna does not call it superior but is supportive of separations which is similar to the “religious influx” because of the social changes that are associated with the balance of power between sacred and secular. This stems...

Religion and Pakistani Society: a Realistic Perspective

First of all I want to define the religion. Religion is the set of beliefs and feelings that the people of a specific society or a community or a group of people have and spend their life and do practices of routine life according to...

Concerns of Religion About LGBT

Based on Journal of Adolescence, the negative outcomes were emerged as shared feelings of inadequacy, religious- related guilt from the young participants, struggles with depressive symptoms, and social strain, difficulty in social relationships in both families and friends. First, feelings of inadequacy, the feeling of...

Religious Pluralism and Religious Tolerance Versus How Religions Are Treated in Society

Religion has been a part of history for many years and has been based around God. However, in today’s society, Christianity, among other religions has been facing a rapid decline in terms of people’s faith and is on the path of extinction. Furthermore, religious beliefs...

Trying to find an excellent essay sample but no results?

Don’t waste your time and get a professional writer to help!

You may also like

- Biblical Worldview

- Problem of Evil Essays

- Pilgrimage Essays

- Faith Essays

- Spirituality Essays

- Hell Essays

- Karma Essays

- Church Essays

- Hinduism Essays

- Influence of Christianity Essays

samplius.com uses cookies to offer you the best service possible.By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .--> -->