What Are Religion and Spirituality? Essay

Introduction, spirituality, questioning, works cited.

Human beings are unique creatures characterized by the constant thirst for cognition, self-investigation, and unique beliefs that are an integral part of our mentality. The existence of these phenomena is the main feature that differs from the rest of animals and contributes to the further rise of human society and the appearance of numerous questions related to the nature of our conscience, mind, and soul. Therefore, the issue of the soul is closely connected to such phenomena as religion and spirituality. They are interrelated, but could also go alone at the same time. Very often a person might consider himself/herself to be spiritual but not religious and on the contrary. Moreover, these definitions might be confused. That is why improved comprehending of these issues is vital.

As for religion, it comes from the Latin word religio which means to tie together (Finucane 19). The given definition shows the essence of this unique phenomenon perfectly as people who belong to the same religion are tied together by the common beliefs. values, approaches, etc. From this perspective, religion could be defined as a set of ideas and concepts followed by a group of people who take these as the main guide. However, in a broader meaning of this very term, family, work, or occupation could also be considered religion (Finucane 20). A person might appreciate family values and consider them to be the most important thing in his/her life.

Besides, spirituality is different. All human beings are spiritual (Finucane 21). It means that they have a complex inner organization and can sympathize, feel some sophisticated feelings, emotions, etc. However, spirituality might be expressed through the idea of belonging to something more. An individual might also have an idea about powers that impact our lives and contribute to the appearance of one or another phenomenon. It could also be referred to as spirituality (Mueller et al. 26). At the same time, it is closely connected to religion which is often considered a form of spirituality as both these notions tie us together and contribute to the appearance of common inclinations, values, or desires.

Furthermore, spirituality and religion are the main cognition tools that a person uses to investigate the universe and find answers to the most important questions. However, there is a tendency to associate religion and faith, doubting the allowability of questioning as if a person believes, he/she should have no doubts. The given idea contradicts human nature. Curiosity and thirst for knowledge are its basic elements that contribute to the evolution of our society. That is why only asking questions an individual can understand the most important aspects of things, including religion and spirituality. In other words, the way to God or improved comprehending of spirituality should consist of numerous questions, and when a person can find answers, he/she will also be able to understand the real nature of religion or spirituality.

Altogether, religion and spirituality often come together, comprising an essential part of any individual. However, they should not be confused. Religion is a set of beliefs and values appreciated by a person and taken as the most significant thing when spirituality creates the basis for the appearance of these feelings and contributes to the development of sophisticated ideas, emotions, and feelings. However, both these unique phenomena help individuals to cognize the world and find answers to the most important questions.

Finucane, Dan. “Introduction. Religion, Spirituality, and the Question of God.” Theological Foundations Concepts and Methods for Understanding Christian Faith , edited by John Mueller, Anselm Academic, 2007, pp. 17-26.

Mueller, John et. al. Theological Foundations . Saint Marys Press, 2007.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, August 28). What Are Religion and Spirituality? https://ivypanda.com/essays/what-are-religion-and-spirituality/

"What Are Religion and Spirituality?" IvyPanda , 28 Aug. 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/what-are-religion-and-spirituality/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'What Are Religion and Spirituality'. 28 August.

IvyPanda . 2020. "What Are Religion and Spirituality?" August 28, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/what-are-religion-and-spirituality/.

1. IvyPanda . "What Are Religion and Spirituality?" August 28, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/what-are-religion-and-spirituality/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "What Are Religion and Spirituality?" August 28, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/what-are-religion-and-spirituality/.

- Spirituality in the Workplace Environment

- Spirituality Application in Family Therapy

- Spirituality in Toyota Corporation

- Religion as a Group Phenomenon and Its Levels

- Christian Doctrine of Sin and Women's Leadership

- "The Reverend and Me" by Robert Wineburg

- Church Discipline and Restoration

- Perception of Women in the Old Testament

Select Page

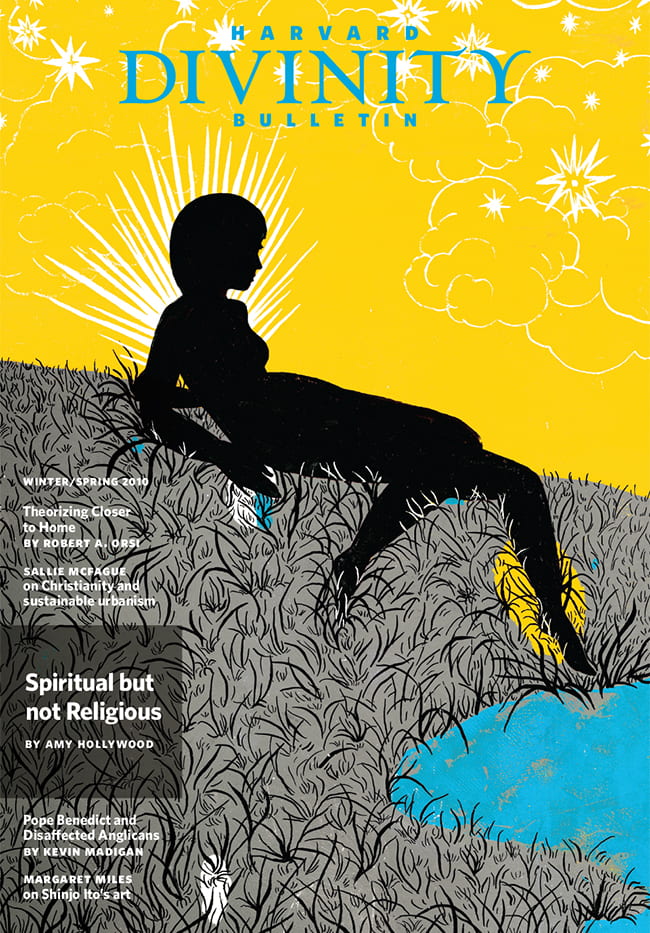

Spiritual but not Religious

Illustration by Rachel Salomon. Cover design by Point Five Design .

Winter/Spring 2010

By Amy Hollywood

Most of us who write, think, and talk about religion are by now used to hearing people say that they are spiritual, but not religious. With the phrase generally comes the presumption that religion has to do with doctrines, dogmas, and ritual practices, whereas spirituality has to do with the heart, feeling, and experience. The spiritual person has an immediate and spontaneous experience of the divine or of some higher power. She does not subscribe to beliefs handed to her by existing religious traditions, nor does she engage in the ritual life of any particular institution. At the heart of the distinction between religion and spirituality, then, lies the presumption that to think and act within an existing tradition—to practice religion—risks making one less spiritual. To be religious is to bow to the authority of another, to believe in doctrines determined for one in advance, to read ancient texts only as they are handed down through existing interpretative traditions, and blindly to perform formalized rituals. For the spiritual, religion is inert, arid, and dead; the practitioner of religion, whether consciously or not, is at best without feeling, at worst insincere. 1

You hear this kind of criticism of religious belief and practice not only among those who call themselves spiritual, but also within religious traditions. For centuries now, Christians have fought over the interplay between authority and tradition, on the one hand, and feeling, enthusiasm, and experience on the other. They have also fought over what kind of experience is properly spiritual or religious. What all sides in these debates share, and what they share with those who understand themselves as spiritual rather than religious, is the presumption that authority and tradition will kill—or, if you are on the other side of the debate, reign in or properly temper—experience. Whereas some American Protestants, for example, insist that one can best know, love, and be saved by God without extraordinary experiences of God’s presence—or with inward experiences rather than with those marked by bodily signs such as tears, shouts, convulsions, outcries, or visions—various revivalist, Holiness, and Pentecostal movements argue that without an intensely felt experience of God, one knows and feels nothing of the divine and so cannot be saved. 2

Modern theologians and scholars of religion from Friedrich Schleiermacher and Samuel Taylor Coleridge to William James and his many followers have understood religion itself in terms of experience—and they have also wrestled with the question of what precisely we mean when we talk about religious experience. Yet Wayne Proudfoot and others critical of the emphasis on religious experience in contemporary theology and religious studies argue that what is at stake for Schleiermacher, James, and their heirs is an attempt to identify an independent realm of experience that is irreducible to other forms of experience. This can serve either as a protectionist strategy, whereby the religious person is able to safeguard her religious experience from naturalistic explanations, or as an academic strategy, whereby a realm is posited over which only specialists in religious studies can claim authority. 3

Running like a thread throughout all these debates—theological, antitheological, historical, philosophical, and those pursued in the interdisciplinary study of religion—lies the attempt to distinguish true from false, sincere from insincere, supernaturally from naturally caused religious or spiritual experience (the terms may differ, but the general point remains the same). With these distinctions comes the recurrent presumption that genuine religious experience is immediate, spontaneous, personal, and affective and, as such, potentially at odds with religious institutions and their texts, beliefs, and rituals. As a number of scholars of religion—as well as Christian theologians—have recently shown, the danger in these discussions is that they miss the ways in which, for many religious traditions, ancient texts, beliefs, and rituals do not replace experience as the vital center of spiritual life, but instead provide the means for engendering it. At the same time, human experience is the realm within which truth can best be epistemologically and affectively (if we can even separate the two) demonstrated. 4

Here I will focus on Christianity, the tradition I know best, and in particular on Christianity in early and medieval Western Europe. Some of the most sophisticated writing about experience in the early and medieval Christian West occurs in works describing and prescribing the best way to live the life of Christian perfection. 5 The various forms of monastic life that emerge in the third and fourth centuries of the Common Era all claim to provide the space in which such perfection might be—if not fully attained—most effectively pursued. The monks and nuns who became the self-described spiritual elite of Christianity through at least the high Middle Ages lived under rules that told them what, when, why, where, and how to act. The most successful of these rules in Western Christianity, the sixth-century Rule of Benedict, is often praised for its flexibility and moderation, yet within it the daily lives of the monks are carefully ordered. Written by Benedict of Nursia (ca. 480–550) for his own community, the rule, and variants of it written for the use of women, became the centerpiece of monastic life in Western Europe during the Middle Ages. If ritual is the repeated and formalized practice of particular actions within carefully determined times and places, the moment in which what we believe ought to be the case and what is the case in the messy realm of everyday action come together, then the Benedictine’s life is one in which the monk or nun strives to make every action a ritual action. 6

Benedict described the monastery as a “school for the Lord’s service”; the Latin schola is a governing metaphor throughout the rule and was initially used with reference to military schools, ones in which the student is trained in the methods of battle. 7 Similarly, Benedict describes the monastery as a training ground for eternal life; the battle to be waged is against the weaknesses of the body and of the spirit. Victory lies in love. For Benedict, through obedience, stability, poverty, and humility—and through the fear, dread, sorrow, and compunction that accompany them—the monk will “quickly arrive at that perfect love of God which casts out fear (1 John 4:18).” Transformed in and into love, “all that [the monk] performed with dread, he will now begin to observe without effort, as though naturally, with habit, no longer out of fear of hell, but out of love for Christ, good habit and delight in virtue.” 8

Central to the ritual life of the Benedictine are communal prayer, private reading and devotion, and physical labor. I want to focus here on the first pole of the monastic life, as it is the one that might seem most antithetical to contemporary conceptions of vital and living religious or spiritual experience. Benedict, following John Cassian (ca. 360–430) and other writers on early monasticism, argues that the monk seeks to attain a state of unceasing prayer. Benedict cites Psalm 119: “Seven times a day have I praised you” (verse 164) and “At midnight I arose to give you praise” (verse 62). He therefore calls on his monks to come together eight times a day for the communal recitation of the Psalms and other prayers and readings. Each of the Psalms was recited once a week, with many repeated once or more a day. Benedict provides a detailed schedule for his monks, one in which the biblical injunction always to have a prayer on one’s lips is enacted through the division of the day into the canonical hours.

To many modern ears the repetition of the Psalms—ancient Israelite prayers handed down by the Christian tradition in the context of particular, often Christological, interpretations—will likely sound rote and deadening. What of the immediacy of the monk’s relationship to God? What of his feelings in the face of the divine? What spontaneity can exist in the monk’s engagement with God within the context of such a regimented and uniform prayer life? If the monk is reciting another’s words rather than his own, how can the feelings engendered by these words be his own and so be sincere?

Yet, for Benedict, as for Cassian on whose work he liberally drew, the intensity and authenticity of one’s feeling for God is enabled through communal, ritualized prayer, as well as through private reading and devotion (itself carefully regulated). 9 Proper performance of “God’s work” in the liturgy requires that the monk not simply recite the Psalms. Instead, the monk was called on to feel what the psalmist felt, to learn to fear, desire, and love God in and through the words of the Psalms themselves. For Cassian, we know God, love God, and experience God when our experience and that of the Psalmist come together:

For divine Scripture is clearer and its inmost organs, so to speak, are revealed to us when our experience not only perceives but even anticipates its thought, and the meaning of the words are disclosed to us not by exegesis but by proof. When we have the same disposition in our heart with which each psalm was sung or written down, then we shall become like its author, grasping the significance beforehand rather than afterward. That is, we first take in the power of what is said, rather than the knowledge of it, recalling what has taken place or what does take place in us in daily assaults whenever we reflect on them. 10

When the monk can anticipate what words will follow in a Psalm, not because he has memorized them, but because his heart is so at one with the Psalmist that these words spontaneously come to his mind, then he knows and experiences God. 11

The word translated here as “disposition” is derived from the Latin affectus , from the verb afficio , to do something to someone, to exert an influence on another body or another person, to bring another into a particular state of mind. Affectus carries a range of meanings, from a state of mind or disposition produced in one by the influence of another, to that affection or mood itself. In many instances, affectus simply means love. At the center of ancient and medieval usages is the notion that love is brought into being in one person by the actions of another. Hence, for Cassian, as later for Bernard of Clairvaux (d. 1153), our love for God is always engendered by God’s love for us. God acts ( affico ); humans are the recipients of God’s actions (so affectus , the noun, is derived from the passive participle of afficio ). Hence the acquisition of proper spiritual dispositions through habit is itself the operation of the freely given grace that is God’s love. There is no distinction here between mediation (through the words of scripture) and immediacy (that of God’s presence), between habit and spontaneity, or between feeling and knowledge.

Of course, the affects, moods, or dispositions engendered by God are not only those of love and desire. Fear, dread, shame, and sorrow, gratitude, joy, triumph, and ecstasy are all expressed in the Psalms and in the other songs found within scripture. According to Cassian, the Psalms lay out the full realm of human emotion, and by coming to know God in and through these affects, the monk comes to know both himself and the divine:

or we find all of these dispositions expressed in the psalms, so that we may see whatever occurs as in a very clear mirror and recognize it more effectively. Having been instructed in this way, with our dispositions for our teachers, we shall grasp this as something seen rather than heard, and from the inner disposition of the heart we shall bring forth not what has been committed to memory but what is inborn in the very nature of things. Thus we shall penetrate its meaning not through the written text but with experience leading the way.

Here, experience is physical, mental, and emotional: the monk is said both to have passed beyond the body and to let forth in his spirit “unutterable groans and sighs,” to feel “an unspeakable ecstasy of heart,” and “an insatiable gladness of spirit.” 12 The entire body and soul of the monk is affected; he is transformed by the words of the Psalms so that he lives them, and through this experience he comes to know, with heart and body and mind, that God is great and good.

The entire body and soul of the monk is affected; he is transformed by the words of the Psalms so that he lives them.

For Cassian, Christians attain the height of prayer and of the Christian life itself when

every love, every desire, every effort, every undertaking, every thought of ours, everything that we live, that we speak, that we breathe, will be God, and when that unity which the Father now has with the Son and which the Son has with the Father will be carried over into our understanding and our mind, so that, just as he loves us with a sincere and pure and indissoluble love, we too may be joined to him with a perpetual and inseparable love and so united with him that whatever we breathe, whatever we understand, whatever we speak, may be God. 13

Although the fullness of fruition in God will never occur in this life, the monk daily trains himself, through obedience, chastity, poverty, and most importantly prayer, to attain it.

Cassian’s understanding of the role of the Psalms in the monastic life lays the foundation for monastic thought and practice throughout the Middle Ages. Many of the most elegant and emotionally nuanced accounts of experience and its centrality to the religious life can be found in the commentary tradition, in which monks (and occasionally nuns) meditatively reflect on the multiple meanings of scriptural texts. 14 Among the masterworks of medieval commentary, Bernard of Clairvaux’s Sermons on the Song of Songs , opens with reference to the centrality of scriptural songs to monastic experience—not only the Psalms, but also the songs of Deborah (Judges 5:1), Judith (Judith 16:1), Samuel’s mother (1 Samuel 2:1), the authors of Lamentations and Job, and all of the other songs found throughout scripture. “If you consider your own experience,” Bernard writes, “surely it is in the victory by which your faith overcomes the world (1 John 5:4) and ‘in your leaving the lake of wretchedness and the filth of the marsh’ (Psalm 39:3) that you sing to the Lord himself a new song because he has done marvelous works (Psalm 97:1)?” 15 Using the language of the Psalms and other biblical texts, writings with which Bernard’s mind and heart is entirely imbued, he describes the path of the soul as sung with and in the words of scripture.

The Song of Songs is the preeminent of songs, the one through which one attains to the highest knowledge of God. “This sort of song,” Bernard explains, “only the touch of the Holy Spirit teaches (1 John 2:27), and it is learned by experience alone.” 16 He thereby calls on his listeners and readers to “read the book of experience” as they interpret the Song of Songs.

Today we read the book of experience. Let us turn to ourselves and let each of us search his own conscience about what is said. I want to investigate whether it has been given to any of you to say, “Let him kiss me with the kiss of his mouth” (Song of Songs 1:1).

Here Bernard suggests that it is through attention to “the book of experience” that the monk can determine what he has of God and what he lacks. Again, the goal is to see the gap between one’s experience of God’s love and one’s love for God and then to meditate on, chew over, and digest the words of the Song so that one might come more fully to inhabit them. The soul should strive, Bernard insists, to be able to sing with the Bride of the Song, “Let him kiss me with the kiss of his mouth.” “Few,” Bernard goes on to write, “can say this wholeheartedly.” His sermons are an attempt to bring about in himself and his readers precisely this desire. Only in this way can the soul ever hope to experience the kiss itself and hence to speak with the Bride in her experience of union with the Bridegroom. 17

For Bernard, such experiences of union with the divine are only ever fleeting in this life. Moreover, he is interested in interior experience rather than in any outward expression of God’s presence. Claims to more extended experiences of the divine presence and of the marking of that presence on the mind and body of the believer—in visions, verbal outcries, trances, convulsions, and other extraordinary experiences—will shortly follow (and will be particularly important in texts by and about women). They will spread, moreover, outside of the monastery and convent, into the world of the new religious orders, the semireligious, and the laity. The questions asked in North America about what constitutes true religious experience and what is false or misleading, generated not by God but by the devil or by natural causes, has its origins in similar deliberations generated by such experiences as they came to prominence in the later Middle Ages.

Most important for our discussion is the way in which ritual engagement with ancient texts leads to, articulates, and enriches the spiritual experience of the practitioner. “Mere ritual,” within this context, would be ritual badly performed. True engagement in ritual and devotional practice, on the other hand, is the very condition for spiritual experience. There is a full recognition of the work involved in transforming one’s experience in this way. 18 Yet, at the same time, medieval monastic writers insist that this transformation can occur only through grace. As I suggested above, there is no more contradiction here than there is in the claim that spiritual experience is both mediated and immediate, ritualized and spontaneous. If God acts through scripture, then in reading, reciting, and meditating on scripture one allows oneself to be acted on by God. Work and grace are here thoroughly entwined through love.

To many contemporary readers, however, there might still seem to be something profoundly different between medieval conceptions of spiritual experience and their own. Even among the growing number of Americans who understand certain kinds of practice—meditation, prayer, and devotional reading among them—as essential to their spiritual experience, there is a suspicion of the particular form such practices take within Christianity and other religious traditions. I suspect that what is at issue here is the association of experience itself, and spiritual experience in particular, with what, for lack of a better word, I will call individualism.

A series of common questions seem to underlie many people’s conception of spiritual experience. How am I to have my own experience of the divine? How can I experience the divine personally , and isn’t such a desire rendered impossible within the framework of institutions that direct my understanding and experience of God? What happens to that aspect of my experience that is irreducible to anyone else’s? On the one hand, many who consider themselves spiritual understand their spirituality in terms of an attunement with nature or spirit—something that is bigger than and lies beyond the boundaries of themselves. Yet, on the other hand, there is a keen desire for this experience to be one’s own. What the medieval monk or nun whose ritual performances I have described here strives to attain is an experience of God that is in conformity with that of the Psalmist and other scriptural authors. The experience must become one’s own, and Bernard insists on the continued specificity of the individual soul. Yet, at the same time, to be a true Christian is to share in a common experience of God.

Or perhaps the concern that many have with the rich spirituality of Christian monasticism may be understood in a slightly different way. Perhaps the concern is with the extent to which Christian monastic life—and the forms of devotional life that stem from it—demands a radical submission to something external to oneself. What happens, then, to individual freedom? What happens to the individual responsibility—religious, ethical, and political—that is concomitant with that freedom? Perhaps we can read the contemporary spiritual seeker less as one who makes seemingly solipsistic demands for an experience particular to herself than as one concerned with handing herself over to another—be it the abbot or abbess to whom one promises absolute obedience, the Psalmist whose words one understands as that of God, or divine love itself—that monastic practice demands. 19

Isn’t the desire to constitute oneself as a spiritual person outside of larger communities illusory, in that we are always constituted in and through our interactions with others?

From this perspective, the debate between the “spiritual” and the “religious” (or between “true” and “false” religious experience) is less about their relative authenticity, sincerity, and spontaneity than about the conceptions of the person, God, and their relationship that underlie competing conceptions of spiritual or religious life. Must we hand ourselves completely over to God—and to the texts, institutions, and practices through which God putatively speaks—in order to experience God? Is this what established religious traditions or their “mainline” instantiations demand? How, if this is the case, are these injunctions best understood in relationship to claims to individual autonomy and responsibility? On the other hand, can we ever claim to be fully autonomous and free? Isn’t the desire to constitute oneself as a spiritual person outside of the framework of larger communities illusory, in that we are always constituted in and through our interactions with others and their texts, practices, and traditions? If, as many contemporary philosophers and theorists argue, we are always born into sets of practices, beliefs, and affective relationships that are essential to who we are and who we become, can we ever claim the kind of radical freedom that some contemporary spiritual seekers seem to demand? How might we reconceive our experience—spiritual or religious, whichever term one prefers—in ways that demand neither absolute submission nor resolute autonomy?

In a way, this is precisely what the medieval Christian monastic texts to which I attend here require. Submission must always be submission freely given. Without the will to submit, one’s practices are meaningless and empty. (And if one is forced, by external means, to submit, that too undermines the potential sacrality of one’s practices.) Yet, paradoxically, one’s freely given submission is engendered by God’s love, just as one receives God’s love—and the ever-deepening experience of that love—through engagement in human practices. Whether one accepts the theological claims of medieval Christian monastic writing, it opens up the vital interplay between practice and gift, submission and freedom, the experience of loving and being loved, that plays a continuing role in Western spirituality. Following Cassian, Benedict, and Bernard, I would suggest that it is only when we understand the way in which we are constituted as subjects through practice—all of us, spiritual, religious, and those who make claims to be neither—that we can begin to understand the real nature of our differences.

- For a wonderful study of the development of conceptions of spirituality in the United States, see Leigh Schmidt, Restless Souls: The Making of American Spirituality (HarperOne, 2006).

- See Ann Taves, Fits, Trances, and Visions: Experiencing Religion and Explaining Experience From Wesley to James (Princeton University Press, 1999); and David Hall, “What Is the Place of ‘Experience’ in Religious History?” Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation 13 (2002): 241–250.

- See Wayne Proudfoot, Religious Experience (University of California Press, 1987); Robert Scharf, “Experience,” in Critical Terms for Religious Studies , ed. Mark C. Taylor (University of Chicago Press, 2000), 94–116; Amy Hollywood, “Gender, Agency, and the Divine in Medieval Historiography,” Journal of Religion 84 (2004): 514–528; and Hall, “Place of ‘Experience,'” 247.

- See, for example, Thinking Through Rituals: Philosophical Perspectives , ed. Kevin Schilbrack (Routledge, 2004); and Robert Wuthnow, After Heaven: Spirituality in America Since the 1950s (University of California Press, 1998).

- This despite the fact that historians and philosophers interested in the category of experience often suggest that there is nothing worthwhile said about it in the Middle Ages. See, most recently, Martin Jay, Songs of Experience: Modern American and European Variations on a Universal Theme (University of California Press, 2005).

- For this account of ritual, see Jonathan Z. Smith, “The Bare Facts of Ritual,” in his Imagining Religion: From Babylon to Jonestown (University of Chicago Press, 1988), 53–65.

- Benedict of Nursia, The Rule of St. Benedict 1980 , ed. Timothy Frye, O.S.B. (The Liturgical Press, 1981), “Prologue,” 165.

- Ibid., chap. 7, pp. 201–203.

- The rule also calls on the monks to read, both in private and communally. Specially recommended are the Old and New Testaments, the writings of the Fathers, Cassian’s Conferences and his Institutes , and the Rule of Basil. According to Benedict, all of these works provide “tools for the cultivation of the virtues; but as for us, they make us blush for shame at being so slothful, so unobservant, so negligent. Are you hastening toward your heaving home?” Ibid., chap. 73, p. 297.

- John Cassian, Conferences, trans. Boniface Ramsey, O.P. (Newman Press, 1997), X, XI, p. 384.

- My account throughout is profoundly influenced by Jean Leclercq, O.S.B., The Love of Learning and the Desire for God: A Study of Monastic Culture , trans. Catherine Misrahi (Fordham University Press, 1961). For a more recent analysis of monastic practice and the formation of the self, one deeply influenced by Leclercq as well, see Talal Asad, “On Discipline and Humility in Medieval Christian Monasticism,” in his Genealogies of Religions: Discipline and Reasons of Power in Christianity and Islam (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993), 125–167.

- Cassian, Conferences , X, XI, p. 385.

- Ibid., X, VII, pp. 375–376.

- In part because of prohibitions against women publicly interpreting scripture, their reflections on experience often take other forms, among them accounts of visions, auditions, and ecstatic experiences of God’s presence or of union with God and—here paralleling Bernard’s practice—commentaries on these experiences.

- Bernard of Clairvaux, Sermons on the Song of Songs , in Selected Works , trans. G. R. Evans (Paulist Press, 1987), Sermon 1, V.9, p. 213.

- Ibid., Sermon 1, V.10–11, p. 214.

- Ibid., Sermon 3, I.1, p. 221.

- Here, I would take issue with the simplistic formulation of the relationship between belief and practice suggested by Louis Althusser. Althusser claims that Blaise Pascal said, “more or less: ‘Kneel down, move your lips in prayer, and you will believe.’ ” Althusser’s position is more complicated than these lines would suggest, but they have had an enormous purchase as indicators of an almost behavioralist account of the efficacy of religious (and other forms) of practice. Lost is the sense that mere repetition does little to transform the subject, but rather that one must look to one’s own experience, think, reflect, meditate, and feel the words of scripture, and work constantly to conform the former to the latter. See Louis Althusser, “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses: Notes Towards an Investigation,” in Lenin and Philosophy, and Other Essays , trans. Ben Brewster (Monthly Review Press, 2001), 114.

- This is precisely the issue faced by Sarah Farmer, the founder in 1884 of the Greenacre community in Eliot, Maine. Farmer brought an eclectic mix of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century spiritual movements together at Greenacre, among them Transcendentalism, New Thought, Ethical Culture, and Theosophy, as well as vibrant interest in non-Western religious traditions. Yet when Farmer became a member of the Baha’i faith—despite that movement’s call for “religious unity, racial reconciliation, gender equality, and global peace,” the more “free-ranging seekers” among her cohort objected strongly to what they saw as her submission to a single religious authority, its texts, beliefs, and practices. On Farmer, see Schmidt, Restless Souls , 181–225. The phrases cited here are on page 186.

Amy Hollywood is the Elizabeth H. Monrad Professor of Christian Studies at HDS.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.

Spirituality is a broad and subjective concept that encompasses a sense of connection to something greater than oneself. It often involves exploring questions about the meaning of life, the nature of existence, and the purpose of our existence.

Different cultures, belief systems, and philosophies have their own interpretations of spirituality. For some, it is linked to organized religion and faith in a higher power or deity. For others, it may be more secular, focusing on inner peace, mindfulness, and a sense of interconnectedness with the universe.

Hello, I have a similar line of thought. I am atheist but things fell into place about all this a few months ago I did not need to throw away the idea of the all-powerful after all. It is not God. It is greater than all Gods and religions. Some religions believe almost the same thing. The “all powerful all” is simply the totality of what is. It had no mind or beingness at first. It was what we call the big bang. Life evolved with no designer or God. This totality still is all and still has all power. Sentients is within it. We serve the all powerful and its servant. This is a very big very old universe. I speculate very advanced extremely advanced beings are here and can be connected to with prayer and mediation. Of course they agree with spiritual atheism. They also know about the all powerful all. It is where they came from just like us. please check out my website www/thewayoffairness.com.

Leave a reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

About | Commentary Guidelines | Harvard University Privacy | Accessibility | Digital Accessibility | Trademark Notice | Reporting Copyright Infringements Copyright © 2024 President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved.

- Spirituality

- Dream Interpretation

- Signs & Symbols

- Advertise With Us

Understanding and following Spirituality via Buddhism

Image source

Spirituality is a widely misunderstood term in common perception. People often attribute spirituality in terms of religion and religious practices. Many times, spiritual progress is assessed on a scale that is based on rituals, routine practices, and the search for an unknown divine being. The divine wisdom of Shri Ram Chandra, the founder of Raja yoga is quite remarkable when he says that ‘Spirituality begins when religion ends’. These words are significant in the essential philosophy of Buddhism.

Siddhartha Gautama- the first Buddha developed a path of self-inquiry and not a religion based on dogmas. At a time when the whole world was indulged in outward rituals, he devised meditation or ‘Dhyana’ as the door to knowing thyself. In the history of spirituality, this became a watershed movement permeating all the existing wisdom ever known to man.

Being Spiritual

The practice of spirituality in any religion requires deep faith and persistence. Every tradition has its own set of practices both ritualistic and non-ritualistic, helping the follower to permeate the ordinary experience. Following these practices meticulously with an open mind exposes the individual to spiritual experiences that are beyond our imagination. In Buddhism, this is a mix of both mind and body working together in tandem achieving a balance. But there is no one-stop- solution for attaining this psychomotor balance. Each individual has to explore and seek this experience through an inward journey.

Roots of Buddhist Spirituality

The roots of Buddhist spirituality evolves from the personal experience of Siddhartha Gautama, a prince with all his luxuries haunted by the hollowness of seeing worldly sufferings. This led him to the path of self-discovery, leaving behind all his material possessions and relationships. Owing to this Buddhist spirituality often directs towards understanding the basic existential paradoxes. The religious belief until that time emphasized too much on repentance based on rituals prescribed by high priests. It divided the entire society based on caste often marginalizing the poor ones. Buddha understood that the whole point of life itself is to escape the continuous cycle of birth and death that causes suffering.

Buddhism is also different from other religions primarily because it doesn’t believe in a particular entity/ power as a god. It doesn’t belong to the category of revealed religions with a specific messenger of God. The spiritual traditions in Buddhism put the onus on an individual to seek the ultimate truth by proper actions and not worship. It heavily relies on practice and experimentation for attaining the truth and breaking the karmic bondage. He urged his followers to experiment by saying “ Believe nothing until you have experienced it and found it to be true. Accept my words only after you have examined them for yourselves- do not accept them simply because of the reverence you have for me ”.

It is a constant journey of trial and error and an intense urge to reach the truth. Such a journey requires discipline and the foremost step for achieving this is by becoming aware. Awareness about the surroundings and the individual (self) as a part of the bigger system. This awareness will normally raise a lot of questions within the individual- a kind of self-talk. The very self-talk is the reason behind the formulation ‘ 4 Noble Truths’ in Buddhist spirituality.

1) Dukkha – The truth of suffering

2) Samudya – The cause of suffering

3) Nirodha -The cessation of suffering

4) Magga – The path to the cessation of suffering

The 4 th Noble truth paved the way for the eightfold path that Buddhism considers as the complete guide to living a fulfilled life. A life that is blissful, compassionate, and radiating with grace. The eightfold path can be seen as the practical application of the noble truths by which a person can escape the endless cycle of suffering. Collectively the eightfold path covers various aspects such as consciousness, knowledge, morality, and contemplation.

Attaining Buddha hood- Knowing Thyself

The great philosopher Osho said “Before Buddha, all religious quests were concerned with searching a God who was unknown and invisible. Aspects of spiritual growth such as liberation and ultimate truth were also to be searched outside an individual”. Buddha created a spiritual rebellion by asking people to search within themselves.

Buddhism as a philosophy believes that everyone is born with the potential to be an enlightened individual- becoming a Buddha. But this inherent capacity has to be nurtured and manifested through constant practice and detachment. Buddhist spirituality also considers the aspect of the impermanence of all creatures. According to this, everything in life is dependent, momentary, and relative. This implies that clinging to a thought process is not at all worth it. This negation of extreme beliefs can be understood from the aspect of embracing a middle path in life. The path that doesn’t get attached or detached too much to anything on this earth.

Our minds have an inherent tendency to wander through different thoughts all the time. The major process in attaining a middle path is to understand the mind and become its master. Every action is originated in the mind before we execute it. In this context, Buddha clarifies that “Mind is everything. What you think you become”. Even though Buddhism is an action-oriented (Karmic) practice, the initial emphasis is on understanding, focusing, and orienting ones’ mind on the right path. But remember that, the process is orienting your mind not controlling it. Usually, Buddhist monks follow a step-by-step routine process to attain this focus and the key to achieving this is becoming mindful.

Mindfulness is now a celebrated term in all meditative techniques. But this goes beyond the usual clichés and auto suggestions. Mindfulness is not a separate practice. It is a dedicated effort of becoming aware of every action we perform. The ability to become the doer and the observer all at the same time. It is not an easy practice at all. The moment a person decides to be mindful, the mind naturally starts to wander. Mindfulness can be achieved by following the Buddhist spiritual practices consistently. Different Buddhist schools of thought have their own methods for achieving this. Initially, it is advisable for an individual to seek the guidance of a spiritual master for understanding and following this path. The spiritual master through his/her experience can guide the seeker to the correct path and help in making constant progress towards the end goal.

Buddhism in Daily Life

Buddhism and its practices are not confined to a group of monks or celibates. The wisdom from Buddhist spirituality is open for all and any layperson can practice it for attaining spiritual progress. The basic practices of Buddhist spirituality are focused on enriching the mind and achieving a perfect balance with the body. Various practices for following Buddhist spirituality is given below,

1)Meditation: it covers a major aspect of Buddhist practices with a goal of achieving mindfulness and peace of mind for an individual. Different types of meditation techniques in Buddhism are breath meditation, mindfulness meditation, transcendental meditation, etc. Meditation doesn’t require any particular tools for it is completely a mind technique. A beginner can start practicing as little as 5-10 minutes of sitting still and gradually progress towards a deep meditative experience. Most of the meditative techniques are premised on observing the breath and gradually acknowledging its rhythm. Consistent practice of meditation calms the mind and helps achieve a balance necessary for spiritual attainment.

2) Mantra (Chanting): repetitive chanting of mantras or sacred verses from the Buddhist texts is also a common practice intended to focus and calm the mind. The repetitive action creates a vibration paving the way for the flow of divine energy throughout a person’s body. “ Om Mani Padme Hum ” is a famous Buddhist mantra that is often referred to as compassion mantra. Repeated chanting of this mantra is believed to develop intense compassion in the individual.

3) Offering: a spiritual person not only dwells in the mind practices but should support his fellow beings with necessary material support in times of despair. A person can dedicate weekends or free time for voluntary activity without expecting any monetary benefits. This can be teaching unprivileged kids, nursing senior citizens. Apart from their valuable time, a person may donate food, money, or other essentials to monks or spiritual practitioners.

4)Practicing Dharma: the practices for spiritual attainment should bear fruits in our daily actions. The practice of dharma or righteousness in our day-to-day life at the home, office, etc is very important while following this path. Showing empathy and compassion to all fellow beings will eventually elevate our spiritual experience. Refraining from unfair practices, controlling anger, and practicing frugality are all such practices that increase spiritual power in daily life.

5)Studying Sacred Texts: Buddhist texts are huge treasures of wisdom. Most of these original scriptures are in Pali and Sanskrit languages. A practitioner can start learning them by referring to commentaries on these scriptures written by famous Buddhist monks in English. It is also advisable to take part in regular sermons given by the monks either in person or through online media.

Buddhist spirituality is unique in its beliefs and practices as it puts the individual on the center stage of spirituality. Moksha or attainment of liberation is the ultimate responsibility of an individual and is not connected to any religious beliefs or priestly rituals.

Similarly, it doesn’t even project the idea of god but encourages and individual to attain self-awareness. This awareness will naturally blossom the divine energy in each individual and breaks the bondage of birth and suffering. It is a way of life that welcomes any person irrespective of their class, caste creed, and nationality to be a part of that journey.

About author

You might also like, did jesus die spiritually an in-depth discussion, how you can use the bible to grow your spiritual self, the role of religion in a relationship, all you need to know about biblical angels, recent posts.

- Spirituality What Is Ego Death? Understanding the Concept of Losing One’s Self

- Spirituality The Role Of Music In Spirituality

- Spirituality God Loves The Broken: How Does Spiritual Brokenness Bring Us Closer to God?

- Spirituality What is New Age Spirituality? (Explained)

- Spirituality How To Build Your Meditation Garden (An Easy Guide)

Popular Posts

- 1 Signs & Symbols What is The Spiritual Meaning of Your Left Ear Ringing? September 25, 2020

- 2 Signs & Symbols What is The Spiritual Meaning of Your Right Ear Ringing? October 17, 2020

- 3 Signs & Symbols What does it mean spiritually if your left ear is hot January 15, 2021

- 4 Life What happens after Kundalini Awakening November 9, 2020

A 501(c)(3) Nonprofit

A 501(c)(3) Non-profit Organization

Changing Humanity's Future

Exploring Spirituality: A Guide to Understanding and Practice

Welcome to Humanity's Team's exploration of spirituality. In this detailed guide, we'll delve into the most commonly asked questions about spirituality, offering insights and guidance for your own spiritual journey.

What is Spirituality?

Spirituality is a concept that transcends a single definition, encapsulating a myriad of personal beliefs and experiences. At its core, spirituality involves a sense of connection to something greater than ourselves, often leading to a quest for meaning in life. Unlike religion, which is often structured and doctrine-based, spirituality focuses more on individual belief and personal experience. It can include belief in a higher power, a sense of interconnectedness, a quest for self-discovery, and a lasting and beautiful search for answers to life's big questions.

How do we become more Spiritual?

Embarking on a spiritual journey is a deeply personal process. Central to this journey is the cultivation of inner awareness and mindfulness. This can be achieved through various practices including meditation, yoga, spending time in nature, or engaging in art and music. Helping to still the mind, these activities allow for introspection and a deeper connection with one's inner self. The key is to find the practices that most resonate with your soul and to incorporate them into your daily life.

What are the benefits of Spirituality?

Engaging in spiritual practices can lead to numerous benefits in both the mind and body. Studies have shown that spirituality can contribute to better mental health, reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety. It can foster a sense of peace and well-being, enhance our resilience against stress, and improve overall quality of life. On a physical level, certain practices such as meditation can lower blood pressure, reduce chronic pain, and enhance sleep quality.

Can Spirituality and Science coexist?

The relationship between spirituality and science is a fascinating area of exploration. While they may seem contradictory, many find that the two complement one another. Science offers a way to understand the physical world, while spirituality provides a framework for understanding the non-material aspects of existence. By integrating both, one can find a more holistic understanding of life and existence.

What is the difference between Spirituality and Religion?

Spirituality and religion, while related concepts, have distinct differences. Religion typically involves specific beliefs, rituals, and practices often centered around a deity or deities and is organized in a structured community. Spirituality, on the other hand, is more about an individual's personal relationship with the divine or the universe. It is a broader concept that can encompass religious beliefs but can also be entirely separate from them.

How do we meditate for Spiritual Growth?

Meditation is a cornerstone of many spiritual traditions and a powerful tool for personal growth. To begin meditating, find a quiet space and dedicate a few minutes each day to practice. Focus on your breath, a mantra, or even a candle flame, and gently bring your attention back whenever your mind wanders. The goal is not to empty the mind, but to observe it, understand its patterns and learn to be present in the moment.

What are Spiritual practices?

Spiritual practices are activities that deepen one's spiritual connection and understanding. These can range from traditional practices like prayer and fasting to more contemporary practices like eco-spirituality or volunteer work. The key is to engage in practices that feel meaningful and enriching to you, whether they are introspective practices like journaling or more active activities like community service.

How do we find a Spiritual Path?

Finding a spiritual path is a journey of exploration and discovery. It often involves reading about different spiritual traditions, experimenting with various practices, and reflecting on personal beliefs and experiences. It's important to remain open-minded and patient, as finding a path that resonates can take some time. Keep tuning into your intuition and trust that in time the right path will reveal itself to you.

What is a Spiritual Awakening?

A spiritual awakening is often described as a profound realization or shift in consciousness. It can manifest in various ways, such as a newfound sense of clarity, a deep understanding of one's purpose, or a feeling of unity with all existence. Such awakenings can be spontaneous or the result of prolonged spiritual practice. They often lead to significant changes in one's perspective and lifestyle.

How does Spirituality affect Mental Health?

Spirituality can play a vital role in mental health and well-being. It can offer a sense of purpose, provide comfort in times of stress or grief, and create a sense of community and belonging. However, it's important to approach spirituality in a way that is healthy and supportive of your mental health, recognizing that it's just one component of a holistic approach to well-being.

Discover Your Spiritual Path: A Personalized Quiz

Embark on a journey of self-discovery with our quiz. Answer these questions to uncover insights into your spiritual path and find practices that may resonate with you.

What draws you most in your exploration of spirituality?

A. Understanding the deeper meaning of life.

B. Feeling a connection with a higher power or the universe.

C. Finding inner peace and mental clarity.

D. Experiencing a sense of community and belonging.

Which activity do you find most fulfilling?

A. Reading and learning about different philosophies.

B. Spending time in nature.

C. Practicing meditation or yoga.

D. Volunteering or helping others.

Which qualities do you seek most in your spiritual practice?

A. Wisdom and knowledge.

B. Mystery and awe.

C. Calmness and balance.

D. Compassion and service.

How do you prefer to explore spirituality?

A. Through structured study or religious texts.

B. Through personal experiences and intuition.

C. Through guided practices like meditation or retreats.

D. Through community service and social activism.

When facing challenges, you prefer to:

A. Reflect and seek insights from various teachings.

B. Connect with nature or a higher power for guidance.

C. Engage in mindfulness or calming techniques.

D. Seek support from a community or group.

Mostly A's: The Seeker of Wisdom

You are drawn to the intellectual aspects of spirituality. You may find fulfillment in studying spiritual texts, engaging in philosophical discussions, and exploring various religious and spiritual traditions.

Mostly B's: The Mystic

Your path is one of personal experience and intuition. You may be drawn to practices that connect you with the natural world, contemplative activities, and an exploration of the mystical aspects of spirituality.

Mostly C's: The Inner Explorer

You value inner peace and balance. Mindfulness practices, meditation, and yoga might be particularly beneficial for you as you seek to understand your inner self and find tranquility.

Mostly D's: The Compassionate Activist

Your spirituality is deeply connected with community and service. Engaging in social activism, volunteering, and being part of spiritual communities align with your desire to make a positive impact on the world.

Remember, your spiritual journey is unique to you. This quiz serves as a starting point for an exploration into various practices and methods. I encourage you to blend elements from each area that resonate with your personal beliefs and experiences.

Resources offered by Humanity's Team to support Your Spiritual Journey

At Humanity's Team, we are dedicated to supporting your spiritual growth and exploration. Recognizing that each journey is unique, we offer a variety of resources tailored to meet the growing diversity of needs and interests:

Free Programs and Masterclasses

Our free programs are designed to provide valuable insights and teachings from renowned spiritual leaders and thinkers like Gregg Braden , Neale Donald Walsch , Michael Bernard Beckwith , Suzanne Giesemann , Nassim Haramein , James Van Praagh, and many more. These masterclasses cover a wide range of topics, from mindfulness and meditation to deeper philosophical discussions about spirituality and its role in today's world.

Humanity Stream+

Our streaming platform, Humanity Stream+ , offers a wealth of spiritual content at your fingertips. It features a diverse collection of talks, workshops, and documentaries focused on spirituality, interconnectedness, and personal development. This platform is an excellent resource for those seeking to deepen their understanding and practice of spirituality in daily life.

As we've explored these common questions about spirituality, it's clear that spirituality is a deeply personal and unique journey for each individual. We hope this exploration has provided valuable insights and guidance for your own spiritual path. Remember, the journey is as much about the process of discovery as it is about the destination. Be well on your journey, and Namaste.

< Older Post

Newer Post >

Ep. 209: ‘Envisioning a New Tomorrow’ with Gregg Braden and Nassim Haramein

Ep. 207:‘Awakening our Cosmic Consciousness’ with Jude Currivan

Ep. 206: ‘The Transformative Power of Creativity’ with Barnet Bain

Ep. 205: ‘Awakening the Divine Feminine’ with Anodea Judith

Share this post!

HUMANITY'S TEAM BLOG CATEGORIES

From the Heart

with Steve Farrell

Conscious Thought Leaders

From The Desk of:

Neale Donald Walsch

Humanity's Team Leaders

LISTEN TO ONE OF OUR RECENT PODCASTS

Sign up now so you never miss a blog post, podcast,

or free event with Humanity's Team!

Exploring Good vs. Evil: Navigating Today's Global Landscape

Oracles and Divination: Communicating with Your Higher Self

Navigating the Ether: Exploring the Akashic Records for Spiritual Insight and Growth

Everyone Is On Their Own Journey

Service to the Whole: Finding Joy in Elevating the Collective

Seeking Souls: 7 Essential Questions for Finding Your Spiritual Lifetime Friends

Social media.

Humanity’s Team is a tax-exempt organization in the United States under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Federal Tax ID: 86-1088741. Your donation is tax deductible to the extent permitted by law.

Humanity's Team, 2735B Iris Avenue Suite 3 Boulder, Colorado 80304 United States

Essay on Religion And Spirituality

Students are often asked to write an essay on Religion And Spirituality in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Religion And Spirituality

Understanding religion.

Religion is a system of beliefs that people follow. It includes rules about how to behave, what to eat, and how to worship. Some well-known religions are Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism. These religions have holy books, like the Bible or the Quran, which guide their followers.

Exploring Spirituality

Spirituality is more about a personal journey. It’s about finding inner peace and understanding the deeper meaning of life. It’s not tied to a specific set of rules or a holy book. Some people find spirituality through meditation, nature, or art.

Religion and Spirituality: The Connection

Religion and spirituality are often linked but they are not the same. Religion can be a path to spirituality. For example, praying can help people feel more connected to something bigger than themselves. But you can also be spiritual without following a religion.

Differences Between Religion and Spirituality

The main difference between religion and spirituality is freedom. With religion, you follow a set of rules. With spirituality, you make your own path. Some people prefer the structure of religion. Others prefer the freedom of spirituality.

Combining Religion and Spirituality

Many people combine religion and spirituality. They might follow a religion but also have their own spiritual practices. This can help them feel more connected to their religion and find more meaning in their lives.

250 Words Essay on Religion And Spirituality

Understanding religion and spirituality.

Religion and spirituality are two terms often used together, but they have different meanings. Religion refers to a set of beliefs and practices agreed upon by a group of people. These beliefs often involve a higher power or deity. On the other hand, spirituality is a personal journey. It involves a person’s connection with their inner self, the world around them, and sometimes, a higher power.

Religion: A Group Experience

Religions like Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism have many followers. Each religion has its own rules, rituals, and holy books. These guide how people should live their lives. For example, Christians read the Bible and Muslims read the Quran. These books give people a path to follow to live a good life.

Spirituality: A Personal Journey

Spirituality is different. It is not about following a set path. It is about finding one’s own path. This could involve meditation, spending time in nature, or helping others. Some people may even choose to follow parts of different religions. The goal is to find peace and happiness within oneself.

The Connection Between Religion and Spirituality

Religion and spirituality can be connected. Many people find spirituality in their religion. They feel a deep connection with the higher power they worship. Others may not follow a religion but still be spiritual. They may find a connection with the world around them or within themselves.

In conclusion, religion and spirituality are two sides of the same coin. They both seek to answer big questions about life, purpose, and connection. Each person chooses their own way to explore these questions. Whether through religion, spirituality, or both, the journey is a personal one.

500 Words Essay on Religion And Spirituality

Religion and spirituality are two terms often used together. They may seem the same, but they are different in many ways. Let’s try to understand them in simple terms.

What is Religion?

Religion is a set of beliefs, rituals, and practices that people follow. These are often shared by a group or community. Religions usually have holy books, like the Bible for Christians or the Quran for Muslims. These books guide people on how to live their lives. People who follow a religion often go to a special place, like a church or a mosque, to pray or worship.

What is Spirituality?

Spirituality is more about personal experience. It is about finding your own path and making sense of your life. It does not have set rules like religion. Some people find spirituality in nature, while others find it in art or music. It is a personal journey that is different for everyone.

Difference Between Religion and Spirituality

The main difference between religion and spirituality is that religion is organized and shared among people, while spirituality is personal and unique to each person. Religion often involves following rules and rituals. Spirituality, on the other hand, is more about personal growth and self-discovery.

Connection Between Religion and Spirituality

While religion and spirituality are different, they are also connected. Many people find spirituality through their religion. They use their religious beliefs to guide their spiritual journey. At the same time, some people who do not follow a religion still consider themselves spiritual. They may not follow a set of religious rules, but they still seek meaning and purpose in their lives.

Importance of Religion and Spirituality

Both religion and spirituality play a big role in people’s lives. They can provide comfort, guidance, and a sense of purpose. They can help people cope with difficulties and make sense of the world around them. They can also bring people together and create a sense of community.

In conclusion, religion and spirituality are two sides of the same coin. They are different but also connected. They can both play a big role in helping people find meaning and purpose in their lives. It is important to respect and understand both, as they can offer different paths to the same goal: understanding ourselves and the world around us.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Reparations For Slavery

- Essay on Reservation Boon Or Bane

- Essay on Responsible Use Of Social Media For Students

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Spirituality

The power of spirituality and psychology, is it possible to unite these powerful influences on the meaning of life.

Posted March 29, 2024 | Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Before we discuss spirituality , we must be clear, for the purposes of this article, that we are not specifically referring to any religion. Obviously, we know that there are many different religions, each with its own persuasion on the nature of life and the transcendent. Spirituality, as we shall define it here, may or may not be a part of these religions—though most of them seek it in some particular way.

Spirituality is very personal, and though it may be defined by a specific doctrine or belief by various religions, it is practiced and lived in a personal way. Spirituality is defined here as access and relatedness to the meaning of life from a very personal perspective. By necessity, then, it involves an understanding of a person’s being, a transformation toward a deeper sense of self, and a connection of that self, even a oneness that transcends self and/or identity .

Those in the mental health field, defining psychology as the scientific study of the mind and behavior, previously swore off any relationship with spirituality as it seemed to be unrelated to science. Indeed, many religions often also swore off science, for it seemed unrelated to any particular form of religion. But as time has gone by there has been much research done on the benefits of spirituality and religion for mental health.

Many now understand that spirituality benefits mental health, particularly in the event of a crisis or personal difficulty. Through religion or spirituality, one can gain a sense of perspective that enables them to walk through the crisis or dilemma and even be transformed by it. In fact, research has shown that an inclusion of spiritual support is more effective than purely secular forms of support. 1

On the other hand, there are times when religion or spirituality may be problematic during a serious crisis, when, for example, the crisis makes the individual question long-held beliefs or the nature of the Divine. The outcome of these problems with religion or spirituality may be that the person becomes bitter and unable to access the transcendent in any meaningful way, or they may work through their doubts and confusion to develop an even deeper understanding of self and transcendence.

Given this understanding, then, it must be concluded that spirituality itself—whether it is a personal practice under the auspices of a religion or not—involves going into the interiority of self to connect with something higher. That something may be defined in various ways, but it definitely involves some sense of self. While it is true that that sense of self may be damaged by certain beliefs that eschew self as bad or evil and in need of constant surveillance to make sure that it does not misbehave—these beliefs speak more of morality than they do of spirituality.

We sometimes get morality mixed up with spirituality. They are not the same. While some religions espouse strong beliefs regarding morality, spirituality is, as defined above, a very personal experience of that something found deep within the self that relates self to the transcendent. Of course, that doesn’t mean that we should not also live a life that is not harmful to self or other. But it does connote a difference between an external view of behavior and an internal connection to transcendence.

What does this mean then for the average client coming to therapy to get help with a mental health problem? First, it means that spirituality and religion should no longer be excluded from the conversation between a client and their therapist. Clients should be free to talk about their experiences with the transcendent, regardless of religion. Clients should also be free to discuss their atheism or their dissatisfaction with religion or spirituality. In fact, this exploration may be initiated in an assessment of the client's needs, with a question like “what are your spiritual resources, if any?”

Therapists are required by ethical codes to be understanding and sensitive to any religion or spiritual experience without trying to influence the client’s beliefs. This leaves the client free to explore the benefits of, and the problems with, their own beliefs. The hope, then, is that the client will become more clearly aware of a differentiated self, its connection to the transcendent, and a connection to the meaning of life. This consciousness may facilitate a much more fulfilling life.

The American Psychological Association. (2013). What role do religion and spirituality play in mental health? https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2013/03/religion-spirituality Retrieved 3/26/2024.

Andrea Mathews, LPC, NCC , is a cognitive and transpersonal therapist, internet radio show host, and the author of Letting Go of Good: Dispel the Myth of Goodness to Find Your Genuine Self.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

RELIGION AND SPIRITUALITY IN SRI AUROBINDO'S PHILOSOPHY

Related Papers

Patrick Beldio

Sri Aurobindo (nèe Aurobindo Ghose, 1872-1950), a native of India, spent his youth studying poetry and the classics in England. Upon his return to colonial India, he became influential in Indian revolutionary politics. Inspired by his own spiritual experience, Śaktism, Vedānta, Tantra, and the Bhagavad Gītā, he later developed his own “integral yoga” in the French colonial city of Pondicherry. Instead of transcending the Earth, his yoga seeks to transform matter into what he calls “the new supramental creation.” He wrote over 30 books in the areas of yoga theory and practice, social, political, and cultural reflection, art and poetry. He wrote his most important work, his epic poem Savitri, over a 35-year period as a way to develop his spiritual practice. Mirra Alfassa (1878-1973) shared Sri Aurobindo’s goals and joined him in 1920. She was a gifted painter and musician and a spiritual seeker from Paris whom he named “the Mother” when they established the Sri Aurobindo Ashram in 1926. He considered her the feminine Śakti to his masculine Īśvara role, and their followers believe them to be their Avatāras (God/dess in human form). After he died, the Mother continued to guide the Ashram until her death. For 52 years she used painting to grow in her spiritual practice. Both gurus encouraged many of their disciples to use the arts for spiritual growth. Sri Aurobindo’s work has inspired various prominent thinkers, and is considered a significant contribution to Hindu studies, as well as 20th-century colonial Indian history. He is regarded as one of the pioneers of the modern yoga renaissance; however, since the 1980s there has been a lack of scholarship on his thought, and particularly as this applies to art and religion. Also, the Mother’s participation has never been critically examined in this tradition. This dissertation investigates the following question: What are the Mother’s and Sri Aurobindo’s aesthetic theory and to what extent does their artwork and their collaboration with their disciples demonstrate their aesthetics? This study uses a historical-critical methodology to examine the development of thought in their written texts on culture and aesthetics, and a visual culture approach to interpret their use of art, architecture, and visual culture. It relies upon disciples’s diaries, reproductions of drawings and paintings by the Mother and her disciples, and the author’s ethnographic data collected during his stay in the Ashram in India in 2012-13. The results of this dissertation: 1) their yoga is “descendant,” demanding a principle of growth that welcomes oppositions found in life to stimulate the universalization of the basic consciousness and to divinize the Earth; the arts aid this process by helping the disciple to face oppositions with sincerity and resilience, and to unveil spiritual potentials that were not known until the creative process uncovered them; 2) they prize the intuition and higher spiritual faculties of consciousness in their creative process and spiritual experience, which diminishes and potentially annihilates the importance of the intellect; 3) for them, the arts are essentially tied to beauty, which aids their goal of the “new creation;” their ideal of beauty occurs when the physical art media harmonizes with the meaning of the artwork, uniting qualities of beauty with the value of beauty. This study concludes that if Sri Aurobindo is a guru who is primarily an artist, his teaching is principally found in an examination of his creative process, his poetry, and his work with his and the Mother’s disciples. Likewise, as an artist-guru, the Mother’s teaching is chiefly encountered in an investigation of her guidance of the Ashram, her painting, music, architecture, and visual culture, and most importantly her claims to the transformation of her own body. Their combined teaching is intended to be a transformative experience of growth through beauty, which for them is a way to create a non-sectarian sacred gaze in their followers. Their aesthetic goals might be characterized as expanding the basic consciousness in order to critique past uses of beauty that have become an abuse of others; to reinterpret past achievements in beauty with an intent to include all; and still further, to create new, more inclusive expressions of beauty in one’s own historical context.

suruchi dubey

Religions of South Asia

Alex Wolfers

Sri Aurobindo Ghose (1872-1950), the revolutionary yogi of Pondicherry, was one of India's first global gurus of the modern age. Eluding easy classification , at different stages in his life he played the role of scholar, politician, poet, philosopher and mystic. Despite being the subject of considerable scholarship , Aurobindo has generally been presented as a disjointed figure, fragmented and constrained by disciplinary boundaries. ongoing disputes within the wider Aurobindo community regarding his contested legacy have drawn attention to his (mis)appropriation by a resurgent Hindutva ethno-nationalism. Against the attempts by some to monumentalize Aurobindo as an infallible Avatar, this inter-disciplinary review of the field of Aurobindo studies seeks to bring together a wide range of scholarly perspectives so as to serve as a meeting ground for multiple overlapping interpretations and future integral research. Indeed, only if we place Aurobindo's accession to Avatarhood in the context of his poetic, political and prophetic vision can we better understand how he reconciled the revolutionary and the mystic in his own life. Just as Aurobindo's theo-political reconfiguration of Hinduism under colonial conditions invokes an anticipatory horizon of individual and collective transformation, his conception of Avatarhood demands a mode of spiritual envisioning that sets the stage for utopian struggle.

Deliberate Distortions of Sri Aurobindo's Life and Yoga

Raman Reddy

On the gross distortions regarding Sri Aurobindo's Life and Yoga in Peter Heehs's book "Lives of Sri Aurobindo" (2008, Columbia Press, U.S.A.)

Dr. Debashri Banerjee

The social political thought of Sri Aurobindo is most astonishing one as it is not devoid of spiritual touch. I am dealing with its uniqueness in this regard. This is not my PhD dissertation thesis.

Scaria Thuruthiyil

aurobindo's educational system traces back to the ancient guru-sishya system of hinduism

Kit Hildyard

Nova Religio

Peter Heehs

The Sri Aurobindo Ashram was founded by Sri Aurobindo Ghose and Mirra Alfassa as a place for individuals to practice yoga in a community setting. Some observers regard the ashram as the center of a religious movement, but Aurobindo said that any attempt to base a movement on his teachings would end in failure. Nevertheless, some of his followers who view themselves as part of a movement use mass mobilization techniques, litigation and political lobbying to advance their agenda, which includes the dismissal of current ashram trustees and amendment of the ashram’s trust deed. In this article, I examine Aurobindo’s ideas on the relationship between individual and community, and I sketch the history of the ashram with reference to these ideas. As a member of the ashram, I approach this study from a hybrid insider/ outsider stance.

In this to be published book I aim to consider several aspects of swaraj & boycott theories as conceived by Sri Aurobindo. Both of them were important tools of Indian agitation started from 1905 but here my main focus would be upon simply the implications of Sri Aurobindo deprived of their political consequences.

RELATED PAPERS

Nehru Memorial Museum and Library Occasional Paper

Christian Hackbarth-Johnson