Explore millions of high-quality primary sources and images from around the world, including artworks, maps, photographs, and more.

Explore migration issues through a variety of media types

- Part of The Streets are Talking: Public Forms of Creative Expression from Around the World

- Part of The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Winter 2020)

- Part of Cato Institute (Aug. 3, 2021)

- Part of University of California Press

- Part of Open: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Part of Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, Vol. 19, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

- Part of R Street Institute (Nov. 1, 2020)

- Part of Leuven University Press

- Part of UN Secretary-General Papers: Ban Ki-moon (2007-2016)

- Part of Perspectives on Terrorism, Vol. 12, No. 4 (August 2018)

- Part of Leveraging Lives: Serbia and Illegal Tunisian Migration to Europe, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (Mar. 1, 2023)

- Part of UCL Press

Harness the power of visual materials—explore more than 3 million images now on JSTOR.

Enhance your scholarly research with underground newspapers, magazines, and journals.

Explore collections in the arts, sciences, and literature from the world’s leading museums, archives, and scholars.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Working with sources

How to Find Sources | Scholarly Articles, Books, Etc.

Published on June 13, 2022 by Eoghan Ryan . Revised on May 31, 2023.

It’s important to know how to find relevant sources when writing a research paper , literature review , or systematic review .

The types of sources you need will depend on the stage you are at in the research process , but all sources that you use should be credible , up to date, and relevant to your research topic.

There are three main places to look for sources to use in your research:

Research databases

- Your institution’s library

- Other online resources

Table of contents

Library resources, other online sources, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about finding sources.

You can search for scholarly sources online using databases and search engines like Google Scholar . These provide a range of search functions that can help you to find the most relevant sources.

If you are searching for a specific article or book, include the title or the author’s name. Alternatively, if you’re just looking for sources related to your research problem , you can search using keywords. In this case, it’s important to have a clear understanding of the scope of your project and of the most relevant keywords.

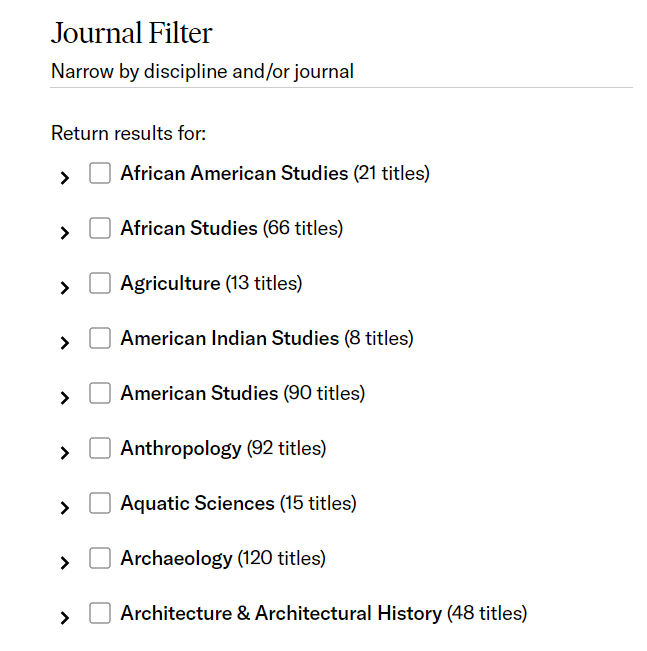

Databases can be general (interdisciplinary) or subject-specific.

- You can use subject-specific databases to ensure that the results are relevant to your field.

- When using a general database or search engine, you can still filter results by selecting specific subjects or disciplines.

Example: JSTOR discipline search filter

Check the table below to find a database that’s relevant to your research.

Google Scholar

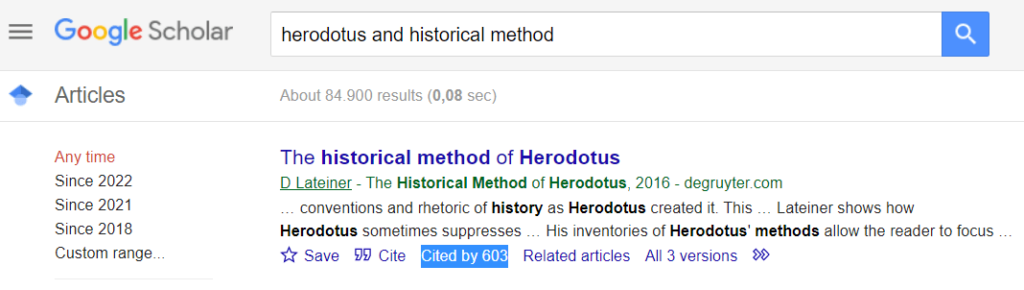

To get started, you might also try Google Scholar , an academic search engine that can help you find relevant books and articles. Its “Cited by” function lets you see the number of times a source has been cited. This can tell you something about a source’s credibility and importance to the field.

Example: Google Scholar “Cited by” function

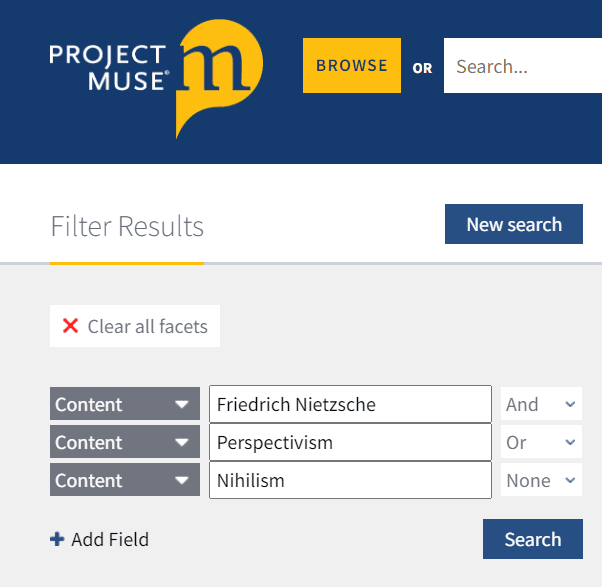

Boolean operators

Boolean operators can also help to narrow or expand your search.

Boolean operators are words and symbols like AND , OR , and NOT that you can use to include or exclude keywords to refine your results. For example, a search for “Nietzsche NOT nihilism” will provide results that include the word “Nietzsche” but exclude results that contain the word “nihilism.”

Many databases and search engines have an advanced search function that allows you to refine results in a similar way without typing the Boolean operators manually.

Example: Project Muse advanced search

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

You can find helpful print sources in your institution’s library. These include:

- Journal articles

- Encyclopedias

- Newspapers and magazines

Make sure that the sources you consult are appropriate to your research.

You can find these sources using your institution’s library database. This will allow you to explore the library’s catalog and to search relevant keywords. You can refine your results using Boolean operators .

Once you have found a relevant print source in the library:

- Consider what books are beside it. This can be a great way to find related sources, especially when you’ve found a secondary or tertiary source instead of a primary source .

- Consult the index and bibliography to find the bibliographic information of other relevant sources.

You can consult popular online sources to learn more about your topic. These include:

- Crowdsourced encyclopedias like Wikipedia

You can find these sources using search engines. To refine your search, use Boolean operators in combination with relevant keywords.

However, exercise caution when using online sources. Consider what kinds of sources are appropriate for your research and make sure the sites are credible .

Look for sites with trusted domain extensions:

- URLs that end with .edu are educational resources.

- URLs that end with .gov are government-related resources.

- DOIs often indicate that an article is published in a peer-reviewed , scientific article.

Other sites can still be used, but you should evaluate them carefully and consider alternatives.

If you want to know more about ChatGPT, AI tools , citation , and plagiarism , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- ChatGPT vs human editor

- ChatGPT citations

- Is ChatGPT trustworthy?

- Using ChatGPT for your studies

- What is ChatGPT?

- Chicago style

- Paraphrasing

Plagiarism

- Types of plagiarism

- Self-plagiarism

- Avoiding plagiarism

- Academic integrity

- Consequences of plagiarism

- Common knowledge

Scribbr Citation Checker New

The AI-powered Citation Checker helps you avoid common mistakes such as:

- Missing commas and periods

- Incorrect usage of “et al.”

- Ampersands (&) in narrative citations

- Missing reference entries

You can find sources online using databases and search engines like Google Scholar . Use Boolean operators or advanced search functions to narrow or expand your search.

For print sources, you can use your institution’s library database. This will allow you to explore the library’s catalog and to search relevant keywords.

It is important to find credible sources and use those that you can be sure are sufficiently scholarly .

- Consult your institute’s library to find out what books, journals, research databases, and other types of sources they provide access to.

- Look for books published by respected academic publishing houses and university presses, as these are typically considered trustworthy sources.

- Look for journals that use a peer review process. This means that experts in the field assess the quality and credibility of an article before it is published.

When searching for sources in databases, think of specific keywords that are relevant to your topic , and consider variations on them or synonyms that might be relevant.

Once you have a clear idea of your research parameters and key terms, choose a database that is relevant to your research (e.g., Medline, JSTOR, Project MUSE).

Find out if the database has a “subject search” option. This can help to refine your search. Use Boolean operators to combine your keywords, exclude specific search terms, and search exact phrases to find the most relevant sources.

There are many types of sources commonly used in research. These include:

You’ll likely use a variety of these sources throughout the research process , and the kinds of sources you use will depend on your research topic and goals.

Scholarly sources are written by experts in their field and are typically subjected to peer review . They are intended for a scholarly audience, include a full bibliography, and use scholarly or technical language. For these reasons, they are typically considered credible sources .

Popular sources like magazines and news articles are typically written by journalists. These types of sources usually don’t include a bibliography and are written for a popular, rather than academic, audience. They are not always reliable and may be written from a biased or uninformed perspective, but they can still be cited in some contexts.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Ryan, E. (2023, May 31). How to Find Sources | Scholarly Articles, Books, Etc.. Scribbr. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/working-with-sources/finding-sources/

Is this article helpful?

Eoghan Ryan

Other students also liked, types of sources explained | examples & tips, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, boolean operators | quick guide, examples & tips, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Library Research at Cornell: Find Articles

- The Research Steps

- Which Topic?

- Find the Context

- Find Articles

- Evaluate Sources

- Cite Sources

- Review the Steps

- Find Primary Sources

- Find Images

- Library Jargon

Tips for Finding Articles

- Use online databases to find articles in journals, newspapers, and magazines (periodicals). You can search for periodical articles by the article author, title, or keyword by using databases in your subject area in Databases .

- Choose the database best suited to your particular topic--see details in the box below.

- Use our Ask a Librarian service for help for figuring out which databases are best for your topic.

- If the article full text is not linked from the citation in the database you are using, search for the title of the periodical in our Catalog . This catalog lists the print, microform, and electronic versions of journals, magazines, and newspapers available in the library.

Finding Periodicals and Periodical Articles

Topic outline for this page:

- What Are Periodicals?

Finding the Periodical When You Do Have the Article Citation

- Locating Periodicals in Olin and Uris Libraries

Distinguishing Scholarly Journals from Other Periodicals

- Evaluating Individual Periodical Titles

What are Periodicals?

Periodicals are continuing publications such as journals, newspapers, or magazines. They are issued regularly (daily, weekly, monthly, or quarterly).

The Cornell Library Catalog includes records for all the periodicals which are received by all the individual units of the Cornell University Library (Music Library, Mann Library, Law Library, Uris Library, etc.).

The Cornell Library Catalog does not include information on individual articles in periodicals. To find individual periodical articles by subject, article author, or article title, use periodical databases .

When you know the periodical title ( Scientific American, The New York Times, Newsweek ) search the Cornell Library Catalog by journal title .

Finding Articles When You Don't Have the Citation

To find an article, use databases.

When you don't have the citation to a specific article, but you do want to find articles on a subject, by a specific author or authors, or with a known article title, you need to use one or more periodical databases . But how do you know which periodical index to use?

What kind of periodicals are you looking for?

- scholarly journals?

- newspapers and substantive news sources?

- popular magazines?

- all three kinds?

[ Learn how to identify scholarly journals, news sources, and popular magazines. ]

If you want articles from scholarly, research, peer-reviewed journals , ask a reference librarian to recommend an index/database for your topic. Some databases index journals exclusively, like America: History and Life , EconLit , Engineering Village , MLA Bibliography , PsycINFO , PubMed , and Web of Science . Google Scholar searches across all scholarly disciplines and subjects. You can also use the subject menu in Databases linked from the library home page to locate databases that index scholarly publications.

If you want newspaper articles , see this guide to newspaper indexes and full-text newspaper databases . Online databases for finding newspaper articles are listed here: News Collections Online: News Databases .

If you want popular magazines , use Academic Search Premier or ProQuest Research Library . A printed index, Reader's Guide to Periodical Literature covering popular magazines from 1890 to 2011 is found in the Olin reference collection (Olin Reference AI 3 .R28).

The online index Reader's Guide Retrospective indexes popular magazines from 1890 to 1982 online. Periodical Contents Index covers some popular magazines for an even broader time period: 1770 to 1993.

If you want an index to all three kinds of articles, use Academic Search Premier or ProQuest Research Library . To find older articles, try Periodical Contents Index ; it indexes periodicals from 1770 to 1993.

If you want to search many databases simultaneously , use Articles & Full Text , also linked from the Library home page .

- If you're not sure which kind of periodical you want or you're not sure which periodical index to use, or if you want help searching, ask a reference librarian .

Remember you can always browse the titles of online periodical databases available online by clicking on this link to the subject categories in the Databases or on the Databases link in the search box on the Library home page .

When You Have a Citation to a Specific Article, Use the Cornell Library Catalog

When you do have the citation or reference to a periodical article--if you know at least the title of the periodical and the issue date of the article you want--you can find its location at Cornell by using the Cornell Library Catalog . Choose "Journal Title" in the drop-down menu to the right of the search box, click in the search box, type in the title of the periodical in the search box, and press <enter> . Don't use the abbreviated titles that are often used in periodical indexes; remember to omit "a," "an" or "the" when you type in the periodical title.

Search examples in the Cornell Library Catalog:

* When searching for the title, Journal of Modern History

Type the following in the search box: journal of modern history

* When searching for the title, Annales Musicologiques: Moyen-Age et Renaissance

You may type the following: annales musicologiques moyen age (Omit punctuation) (searching is not case sensitive)

Depending on the number of records your search retrieves, you will see either a list of entries or a single record for an individual periodical title. If there is a list of titles, scroll through it and click on the line that lists the journal title you want to see for the call number and location information or the online link(s).

If the journal is available in electronic form , there will be a link or links int the box labelled "Availability" in the catalog record. Click on this link. In most cases, this will take you to the opening screen for the journal, and you can choose the issue you want from there.

If the journal is available in print form , record the call number and any additional location information in the catalog record. Now you're ready to find it on the shelf. Consult the local stack directory for the call number locations in individual libraries.

Locating Print Periodicals in Olin and Uris Libraries

Current periodicals:.

Periodicals noted as "Current issues in Periodicals Room" in the Cornell Library Catalog are print journals shelved by title in the Current Periodicals Room on the main level in Olin Library. This room is immediately to the right and down the hall as you enter Olin Library. Only a small selection of current print periodicals is in this room : all other current periodical issues go directly to the Olin stacks where they are shelved by call number.

Back Issues of Periodicals

Back issues of periodicals are shelved by call number in the Olin and Uris Library stacks. Some back periodicals are shelved in specific subject rooms; watch for location notes in the Cornell Library Catalog record for the title you want.

Pay attention to the + and ++ indicators by the call number. Titles with the + and ++ (Oversize) designations and titles with no plus marks are each shelved in separate sections on each floor in Olin Library and separate floors in Uris Library.

Back issues on microfilm, microfiche, and microprint are housed on the lower or B Level in Olin Library.

Journals, news publications, and magazines are important sources for up-to-date information across a wide variety of topics. With a collection as large and diverse as Cornell's it is often difficult to distinguish between the various levels of scholarship found in the collection. In this guide we have divided the criteria for evaluating periodical literature into four categories:

- Scholarly / VIDEO: How to Identify Scholarly Journal Articles

- Substantive News and General Interest / VIDEO: How to Identify Substantive News Articles

- Sensational and Tabloid

Definitions:

Webster's Third International Dictionary defines scholarly as:

- concerned with academic study, especially research,

- exhibiting the methods and attitudes of a scholar, and

- having the manner and appearance of a scholar.

Substantive is defined as having a solid base, being substantial.

Popular means fit for, or reflecting the taste and intelligence of, the people at large.

Sensational is defined as arousing or intending to arouse strong curiosity, interest or reaction.

Keeping these definitions in mind, and realizing that none of the lines drawn between types of journals can ever be totally clear cut, the general criteria are as follows.

Scholarly journals are also called academic, peer-reviewed, or refereed journals . Strictly speaking, peer-reviewed (also called refereed) journals refer only to those scholarly journals that submit articles to several other scholars, experts, or academics (peers) in the field for review and comment. These reviewers must agree that the article represents properly conducted original research or writing before it can be published.

To check if a journal is peer-reviewed/refereed, search the journal by title in Ulrich's Periodical Directory --look for the referee jersey icon.

What to look for:

- Scholarly journal articles often have an abstract, a descriptive summary of the article contents, before the main text of the article.

- Scholarly journals generally have a sober, serious look. They often contain many graphs and charts but few glossy pages or exciting pictures.

- Scholarly journals always cite their sources in the form of footnotes or bibliographies. These bibliographies are generally lengthy and cite other scholarly writings.

- Articles are written by a scholar in the field or by someone who has done research in the field. The affiliations of the authors are listed, usually at the bottom of the first page or at the end of the article--universities, research institutions, think tanks, and the like.

- The language of scholarly journals is that of the discipline covered. It assumes some technical background on the part of the reader.

- The main purpose of a scholarly journal is to report on original research or experimentation in order to make such information available to the rest of the scholarly world.

- Many scholarly journals, though by no means all, are published by a specific professional organization.

Examples of Scholarly Journals:

- American Economic Review

- Applied Geography

- Archives of Sexual Behavior

- JAMA : The Journal of the American Medical Association

- Journal of Marriage and the Family (published by the National Council on Family Relations)

- Journal of Theoretical Biology

- Modern Fiction Studies

Substantive News or General Interest

These periodicals may be quite attractive in appearance, although some are in newspaper format. Articles are often heavily illustrated, generally with photographs.

News and general interest periodicals sometimes cite sources, though more often do not.

Articles may be written by a member of the editorial staff, a scholar or a free lance writer.

The language of these publications is geared to any educated audience. There is no specialty assumed, only interest and a certain level of intelligence.

They are generally published by commercial enterprises or individuals, although some emanate from specific professional organizations.

The main purpose of periodicals in this category is to provide information, in a general manner, to a broad audience of concerned citizens.

Examples of Substantive News and General Interest Periodicals:

- The Economist

- National Geographic

- The New York Times

- Scientific American

- Vital Speeches of the Day

Popular periodicals come in many formats, although often slick and attractive in appearance with lots of color graphics (photographs, drawings, etc.).

These publications do not cite sources in a bibliography. Information published in popular periodicals is often second or third hand and the original source is rarely mentioned.

Articles are usually very short and written in simple language.

The main purpose of popular periodicals is to entertain the reader, to sell products (their own or their advertisers), or to promote a viewpoint.

Examples of Popular Periodicals:

- People Weekly

- Readers Digest

- Sports Illustrated

Sensational or Tabloid

Sensational periodicals come in a variety of styles, but often use a newspaper format.

Their language is elementary and occasionally inflammatory. They assume a certain gullibility in their audience.

The main purpose of sensational magazines seems to be to arouse curiosity and to cater to popular superstitions. They often do so with flashy headlines designed to astonish (e.g., Half-man Half-woman Makes Self Pregnant).

Examples of Sensational Periodicals:

- National Examiner

- Weekly World News

Evaluating Periodicals: Magazines for Libraries

Magazines for Libraries describes and evaluates journals, magazines, and newspapers:

Or ask for assistance at the reference desk .

Reference Help

- << Previous: Find Books

- Next: Evaluate Sources >>

- Last Updated: Mar 22, 2024 11:29 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.cornell.edu/sevensteps

Finding Scholarly Articles: Home

What's a Scholarly Article?

Your professor has specified that you are to use scholarly (or primary research or peer-reviewed or refereed or academic) articles only in your paper. What does that mean?

Scholarly or primary research articles are peer-reviewed , which means that they have gone through the process of being read by reviewers or referees before being accepted for publication. When a scholar submits an article to a scholarly journal, the manuscript is sent to experts in that field to read and decide if the research is valid and the article should be published. Typically the reviewers indicate to the journal editors whether they think the article should be accepted, sent back for revisions, or rejected.

To decide whether an article is a primary research article, look for the following:

- The author’s (or authors') credentials and academic affiliation(s) should be given;

- There should be an abstract summarizing the research;

- The methods and materials used should be given, often in a separate section;

- There are citations within the text or footnotes referencing sources used;

- Results of the research are given;

- There should be discussion and conclusion ;

- With a bibliography or list of references at the end.

Caution: even though a journal may be peer-reviewed, not all the items in it will be. For instance, there might be editorials, book reviews, news reports, etc. Check for the parts of the article to be sure.

You can limit your search results to primary research, peer-reviewed or refereed articles in many databases. To search for scholarly articles in HOLLIS , type your keywords in the box at the top, and select Catalog&Articles from the choices that appear next. On the search results screen, look for the Show Only section on the right and click on Peer-reviewed articles . (Make sure to login in with your HarvardKey to get full-text of the articles that Harvard has purchased.)

Many of the databases that Harvard offers have similar features to limit to peer-reviewed or scholarly articles. For example in Academic Search Premier , click on the box for Scholarly (Peer Reviewed) Journals on the search screen.

Review articles are another great way to find scholarly primary research articles. Review articles are not considered "primary research", but they pull together primary research articles on a topic, summarize and analyze them. In Google Scholar , click on Review Articles at the left of the search results screen. Ask your professor whether review articles can be cited for an assignment.

A note about Google searching. A regular Google search turns up a broad variety of results, which can include scholarly articles but Google results also contain commercial and popular sources which may be misleading, outdated, etc. Use Google Scholar through the Harvard Library instead.

About Wikipedia . W ikipedia is not considered scholarly, and should not be cited, but it frequently includes references to scholarly articles. Before using those references for an assignment, double check by finding them in Hollis or a more specific subject database .

Still not sure about a source? Consult the course syllabus for guidance, contact your professor or teaching fellow, or use the Ask A Librarian service.

- Last Updated: Oct 3, 2023 3:37 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/FindingScholarlyArticles

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

Getting Started with Library Research

Research needs and requirements vary with each assignment, project, or paper. Although there is no single “right” way to conduct research, certain methods and skills can make your research efforts more efficient and effective.

If you have questions or can’t find what you need, ask a librarian .

Developing a Research Topic

All research starts with a question.

- Discuss your ideas with a librarian or with your professor.

- Formulate a research question and identify keywords.

- Search subject-focused encyclopedias, books, and journals to see what kind of information already exists on your topic. If you are having trouble finding information, you may need to change your search terms or ask for help.

Additional resources:

- Library Research at Cornell

- Research Guides

Using the Library to Find Research Materials

The Library is the top resource when it comes to locating and accessing research materials.

- Use the library catalog to find materials such as books, music, videos, journals, and audio recordings in our collections.

- Search databases to find articles, book chapters, and other sources within a specific subject area or discipline.

- For materials the Library does not own, use BorrowDirect or Interlibrary Loan for quick and easy access.

- Each library unit has unique collections and subject knowledge. See individual library websites for additional resources in specific subject areas.

- Check out our library research guides for lists of resources curated by library staff. Browse by subject or find guides specific to course offerings.

Evaluating Sources

When using a book, article, report, or website for your research, it is important to gauge how reliable the source is. Visit these research guides for more information:

- How to distinguish scholarly vs non-scholarly sources

- Tips for critically analyzing information sources

- Identify misinformation, disinformation, and propaganda

Citing Sources

When writing a research paper, it is important to cite the sources you used in a way that would enable a reader to easily find them.

- Citation Management

- How to Prepare an Annotated Bibliography

- Code of Academic Integrity

How to Start Your Research

- Choose a Topic

- Search Library Databases

- Search the Library Catalog

- Search Google

- Stay Organized

Your Librarian

Off Campus Access

Off-Campus Access Information

In This Section

In this section, you'll find help with:.

- Understanding what databases are and what they can do for your research

- Where to find databases

- The differences between library databases and Google

Phrase searching

Subject headings.

- Video tutorials for our three major database platforms

What's a Database?

A tool for finding information

A library database is a tool that collects and organizes information so that we can find it more easily. Databases contain records for articles from newspapers, magazines, trade journals, and academic journals, as well as records for other items such as videos, conference proceedings, dissertations, book chapters, and more. A database record contains citation information for articles and other items, and may also point to the full text of the resource. Most databases will have the full-text for some items, but not for others. Some databases are entirely full-text; others have none at all.

Databases can be general and cover many subjects or focus on specific subjects or types of resources. Deciding which database to search depends on what kind of research you’re doing.

- Examples: Academic Search Premier, Academic OneFile, and reference databases like Credo

- Examples: CINAHL (nursing), PsycArticles (psychology), ERIC (education), and JSTOR (humanities subjects)

- Examples: US Newsstream (news articles), EBSCO SWOT Analyses (SWOT analyses), or GPO Monthly Catalog (government reports and publications)

Where to Find Databases

There are several ways to get to relevant databases. The table below will help you get your bearings and find a path that works for your research.

Google vs. Library Databases

When you search Google, do you type in a full-sentence question? No shame - it works there because Google has a sophisticated algorithm that can parse through your question to find the most important words, search with those terms, and ditch the rest. Google even corrects your spelling and searches what it thinks you mean based on your search history.

Library databases, however, can't do that.

Instead, you have to do the first step of parsing out the most important words yourself - which is to say, you'll have to develop keywords . Keywords are search terms that are the most essential words in your research question, topic, or thesis statement.

Developing Keywords:

- Locate the essential words in your research question, problem statement, hypothesis, or thesis.

- What are the nouns, proper nouns, and action verbs that make up your question?

- What are the major concepts or themes that your question addresses?

- Think of a few synonyms or related terms for each keyword.

- Which words will it be useful to search together?

How to Search Databases

Mix and match your keywords - and your strategies..

Watch this quick video and click on each heading below to learn more about some useful search strategies. As you search, try a few of these strategies at the same time! These strategies can help you create complex, specific searches and gather focused information on your topic.

Is your topic a phrase or a string of words?

To search for a phrase in which word order matters, put quotation marks (" ") around your search terms.

- For example: "social media" ; "higher education" ; "reality television"

AND, OR, NOT (Boolean)

Connect your search terms.

Boolean operators AND , OR , and NOT can help you combine and exclude terms from your searches. They're used directly in a database's search bar, between your keywords.

Some databases will have multiple search boxes so that you can split up your search terms and select a Boolean operator from a drop-down menu to combine the terms.

- For example, video games AND violence

- For example, lions OR tigers

- For example, enterprise NOT star trek

Remember Venn Diagrams? They're a great way to visualize what the Boolean operators AND, OR, and NOT can do for your research.

One step further

You can combine phrase searching and more than one Boolean operator to make complex, specific searches.

Placing parentheses () around your search terms is a way to group concepts and tell the database exactly what order to use when processing your search. It's just like the idea of order of operations in mathematics.

- (lions OR Tigers) AND poaching

- "video games" AND (violence OR aggression)

- "higher education" AND testing NOT gre

Use the terms librarians use to classify and organize information!

As you browse the catalog or a database and find a resource that looks promising, look for hyperlinked subjects , also called subject headings. These subject headings can be found in the detailed record for an article--what you get to when you click on a title from your search results list.

Use what you've already found to find more

This strategy involves tracking down the sources that an article (or any piece of information) cites, or following a citation chain . This strategy is a great example of why it's important to cite your sources - citations help your readers find information that is similar or crucial to your own arguments. When you find an article or source that is relevant to your research, take a look at the sources they're citing!

Database Tutorials

Check out these video tutorials for the three major database platforms we use at UJ: EBSCO, ProQuest, and Gale:

Basic Search tutorial for EBSCOhost databases such as Academic Search Premier, CINAHL, and ERIC.

Basic search tutorial for ProQuest databases such as PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, and US Newsstream.

A quick overview of some features of Gale databases such as Academic OneFile and Literature Resource Center.

- << Previous: Find Sources

- Next: Search the Library Catalog >>

- Last Updated: Dec 12, 2023 10:57 AM

- URL: https://libguides.uj.edu/research

Holman Library

Library Research: A Step-By-Step Guide

- 2d. Find Articles

- Library Research: A Step-by-Step Guide

- 1a. Understand Your Assignment

- 1b. Select a Topic

- 1c. Develop Research Questions

- 1d. Identify Search Words

- 1e. Find Background Info

- 1f. Refine Your Topic

- 2a. Use Smart Search Strategies

- 2b. Find Books

- 2c. Find Audio and Video

- 2e. Find Websites

- 2f. Find Info in Holman Library One Search

- 3a. Evaluate By Specific Criteria

- 3b. Distinguish Between Scholarly/Popular Sources

- Step 4: Write

- Step 5: Cite Your Sources

Related guide

- Research Guide: Scholarly Journals by Jennifer Rohan Last Updated Mar 15, 2024 2185 views this year

Interlibrary Loan for finding articles

Can't find the full text of an article.

- Note down the author, title of article, name of the magazine, journal or newspaper, and date of publication

- Note: Requesting electronic articles from another library often takes 1-3 business days, or up to a week for physical item requests.

- Or Ask a Librarian for help by using the chat feature on the "Get Help" tab of this guide!

- Interlibrary Loan (ILL) Request books and articles from other libraries using ILL

Step 2d: Find articles

Why use different types of articles, different articles give you different flavors of info:.

- Scholarly or Peer-Reviewed or Academic Journal articles are good to find results of scientific or academic research. They are written for scholars and provide in-depth analysis of a very specific area of your topic *** For more in-depth info on scholarly journals, click:

- Scholarly Journals

- Trade Journal articles are good for finding articles written for specific professions (police officer, veterinarian...etc.) They often analyze new trends, research, tools or techniques important to their area of work

- Popular Magazine articles are good for summarizing information on a topic for the general public. They often provide a background, summarize research findings, and provide some analysis of a topic

- Newspaper articles are good for facts and up-to-date information. They often provide little analysis of a topic.

- Evaluate articles to determine if they are credible sources for your research

Find articles in the databases

Finding articles in the databases.

The databases listed below are just a few that can help you find journal, magazine, and newspaper articles that are often not freely available through the internet.

- Holman Library Databases by Subject See all of the library's database collections, sorted by subject area. This list is a good place to see the entire list of electronic article resources available in a specific field. You will need to log in with your GRC email address and password to access off-campus.

Search Articles Using Primo One Search

Instead of searching in the databases directly, you can use the main catalog on the Holman Library homepage to search for books, ebooks, videos, and articles from journals, magazines, newspapers, and more.

Tips: How to Use the Holman Library One Search

Find Scholarly Articles

- Scholarly articles are housed inside of journals - sometimes those journals/articles are called Academic or Peer-Reviewed or Refereed

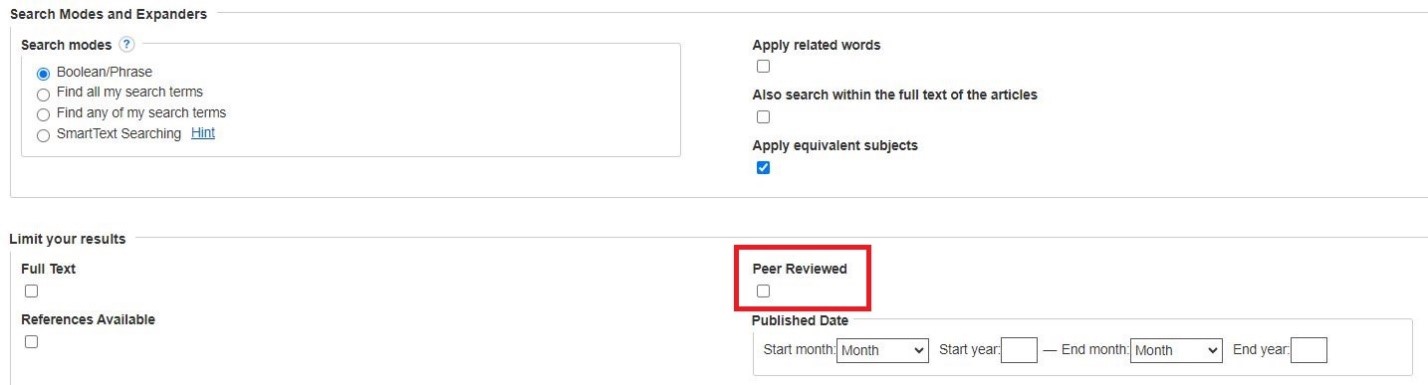

- Often library article databases will help you limit your results to scholarly articles (see image below)

- The image on the left shows how and where to limit in the EBSCO databases, like Academic Search Complete and ERIC.

- The image on the right shows how and where to limit in the ProQuest databases, like ProQuest Combined Databases or Nursing and Allied Health Source

(Click on images to enlarge)

Search strategies

Using the advanced search options in the database.

The image below shows how you can use quotation marks to limit to exact phrases

- for example "Washington State" or "Genetically modified foods" or "stand your ground laws"

- using quotation marks around an exact title is also helpful "Gun Laws in Washington State: A Geographic Study"

The image also shows how you can use the built in Boolean tools using the drop down to change from AND, OR, NOT or how you can add those tools to the search yourself.

(Click on image to enlarge)

Using Google Scholar to find Peer-Reviewed Research

Understanding how to use google scholar .

Google Scholar can be very useful in finding about articles on a topic. You may not always get free, immediate access to the content it shows you, but Google Scholar can certainly be a great place to get started and see what kinds of content is out there.

Here are some features as highlighted in the image below.

- You can click on the title of an article to read the abstract and information about where the article was published.

- By clicking on the small quotation mark icon that appears under the article, you can see a list of citations , in various citation styles including MLA and APA, for the source. Be sure to check these against a style guide as they may be incorrect or incomplete.

- You can limit by date , or a date range to ensure you're finding the most relevant content - and depending on your topic, that might be important.

- If the article is freely available online, there is often a PDF icon and link off to the left.

- And, if in your settings, you at GRC as one of your libraries, the results page will even note and link you to articles housed in the GRC library databases.

- You can request any articles that you learn about here, but are not given full-text access to, through Interlibrary Loan . Use the links for more information about this process or talk to a librarian if you need help!

- Google Scholar Google Scholar allows you to search the web for peer-reviewed article and book citations. You can use these citations to track down the items at Green River or request them by Interlibrary Loan.

- Google Scholar - Search Settings Click on "Library Links" from the menu on the left and then search for "Green River College"

- Research Guide: Interlibrary Loan by Philip Whitford Last Updated Nov 7, 2023 12 views this year

- << Previous: 2c. Find Audio and Video

- Next: 2e. Find Websites >>

- Last Updated: Apr 10, 2024 8:47 AM

- URL: https://libguides.greenriver.edu/library-research

Articles & Media

Books & eBooks

How to Find Articles

How do i get started, what's in the databases, search for articles, books & more, com library databases v. google.

- More Articles

- Fewer Articles

- Grab citations for your articles. You can see step by step how to grab the citations and tweak them in our APA and MLA guides.

- Articles can be printed, downloaded or emailed.

- You can save time by using full text time limits and more.

- You can create free personal database accounts that lat you save and organize your articles and searches.

- Find out how to use these great database features step by step in our guides .

Our most popular databases with students and instructors are Academic OneFile , Academic Search Complete and Research Library . They have articles and article citations from thousands of journals and magazines on virtually every academic subject.

COM Library Guides collect the best databases to search for your subjects, as well as some top articles. Look for the page Articles in the guides.

You can get started now by going Straight to the Good Stuff.

- Medical resources and health information

- Academic reference materials

- Newspapers and magazines from around the world

- Transcripts from TV and Radio

- Research on public and private companies, here and abroad

- Consumer marketing data and emerging technology reports

- Genealogy resources

- Latest breaking news and daily updates from newspaper wire services

- Hundreds of popular periodicals, including Business Week, Rolling Stone, and Smithsonian

- Streaming media

Search OneSearch to search print books, eBooks articles and streaming media simultaneously, or select Go! to get started with all our databases.

Here's Why Databases Are Better

- A search engine won't turn up many websites containing full-text articles from the kind of publications your instructors are looking for.

- Sad, but true: not everything is on the Internet. Few substantive materials are on the Internet for free.

- There is no quality control for information on the Internet.

- 2/3 college students said the Internet doesn't offer a range of resources wide enough for their research needs.

--Source: The Top Ten Reasons TexShare Is Better Than Just Surfing the Internet, Texas State Library.

Wait, There's More!

Some magazine and journal publishers do publish articles on the Internet. Generally this is limited to sample articles or even just abstracts of the articles, so if you do search the Internet for articles you generally will not find many on your topic.

Since all the library's databases can be accessed at home and have thousands more journals available than what is freely available on the Internet, using the databases makes more sense. You will get you a lot more articles at the college level that your instructors expect and in less time.

- Next: More Articles >>

- Last Updated: Jul 5, 2023 1:07 PM

- URL: https://libguides.com.edu/findarticles

© 2023 COM Library 1200 Amburn Road, Texas City, Texas 77591 409-933-8448 . FAX 409-933-8030 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License Class Poll

Library Research 101: Start Your Research

What is an article, what are the different types of articles, where can i find an article, how to access articles behind paywalls.

- Books--what are they and where are they?

- How do I choose a topic?

- How do I write a research question?

- How do I write a thesis statement?

- How do I cite?

- Glossary: Library terms

These are some of the places you can find articles. In general the library's resources (print and online journals, online databases) are best when you are looking for peer-reviewed scholarly or trade articles.

Open web resources include things from Google or other search engines and information provided from social media sites. While it is possible to find some scholarly articles this way you will often face a paywall to access them. Also information from these sources is harder to verify for things like accuracy and may be biased.

- a library database (can search by topic for scholarly peer-reviewed and trade articles)

- One Search (scholarly peer-reviewed, trade and popular articles)

- Individual journal titles (scholarly, peer-reviewed or trade articles)

- In a ' bound journal ' in the library (print)

- In a newspaper

- Google (best for popular and news articles, the occasional journal article)

- Google Scholar (some scholarly and peer-reviewed articles) (Hint: you can first register with Fogler through Google Scholar )

- Newspaper websites (New York Times, Wall Street Journal etc.) (newspaper articles)

- Magazine websites (Time, The Economist, etc.)

Sometimes you find an article, but can't open the full text. If that happens, you still have several options:

- I f you are searching on the open Web (i.e. through Google), you can download the URSUS Proxy Bookmarklet. Once you have this downloaded, if you find an article you are asked to pay for, you can click on the Bookmarklet to see if Fogler Library has free access.

- If you are searching with OneSearch, or some other database, and you don't get the full text of an article, you can search for the journal title in Fogler's ejournal list . You will need to make note of the year, volume, issue number, and pages for the article before you do this search.

- If you still can't find the full text, you can use Fogler's free Interlibrary Loan service to request a copy of the article, which generally takes 24 hours. You first need to set up your free account, by clicking on Create an Account . Then you choose the format of the information you want to request (i.e. New Request/Article) and fill out the form.

And, at any point in your search process, you can contact a librarian to ask for help!

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Books--what are they and where are they? >>

- Last Updated: Feb 8, 2024 9:04 AM

- URL: https://libguides.library.umaine.edu/libraryresearch101

5729 Fogler Library · University of Maine · Orono, ME 04469-5729 | (207) 581-1673

Finding scholarly, peer reviewed articles

Learn how to search for only scholarly and peer-reviewed journal articles.

Scholarly articles are written by researchers and intended for an audience of other researchers. Scholarly writers may assume that the reader already has some understanding of the topic and its vocabulary. Peer-reviewed articles are evaluated by other scholars or experts within the same field as the author before they are published, to help ensure the validity of the research being done. Learn more about the peer review process .

Many scholarly articles are peer-reviewed and vice versa, but this may not always be the case. In addition, an article can be from a peer-reviewed journal and not actually be peer reviewed. Components such as editorials, news items, and book reviews do not go through the same review process.

Many professors will require that you use only scholarly, peer-reviewed journal articles in your research papers and assignments. To simplify the research process, you can limit your search to only see peer-reviewed articles in Library Search and many library databases.

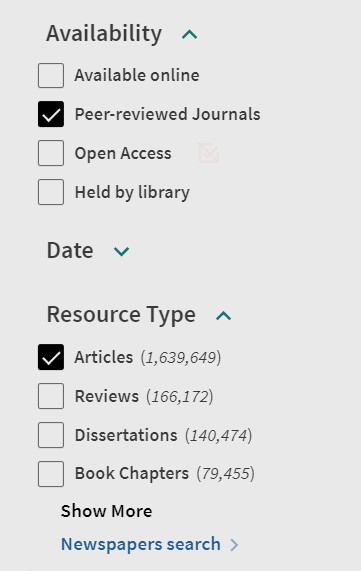

Limiting to peer-reviewed articles in Library Search

In Library Search, you can refine your results to peer-reviewed articles by selecting two filters. Under “Availability,” choose “Peer-reviewed Journals.” Under “Resource Type,” choose “Articles.” If you plan to do multiple searches, be sure to click the lock icon that says “Remember all filters” underneath “Active Filters” at the top. This will ensure your results continue to show only peer-reviewed articles even if you try different keywords. Peer-reviewed articles will display a purple icon of a book with an eye over it under their title and citation information.

Filter options in Library Search. The "Peer-reviewed Journals" and "Articles" options have filled checkboxes next to their names, which indicates these options have been selected.

Limiting to peer-reviewed articles in databases

Many databases have an option to limit your search results to peer-reviewed articles. This will usually appear either in advanced search options or in a bank of filters in the search results screen.

Search options for a database hosted in EBSCO. Under the subheading “Limit your results,” a checkbox with the words “Peer Reviewed” above it is enclosed in a red square to indicate its position on the screen.

Checking the status of your article

If you need further confirmation of whether an article comes from a peer-reviewed journal, you can follow one of the procedures below.

Search for a journal title in the library’s Journals search list. Titles that are peer reviewed will have a small purple icon of an eye above an open book with the words “Peer-Reviewed” next to it.

A small purple icon of an eye above an open book, and the words "Peer-Reviewed" are enclosed in a red rectangle.

If you don’t find a journal in the Journals’ list as described above, you can consult the UlrichsWeb database . It includes information on journals that are not owned by the University, so you might want to check a journal title there before you make an Interlibrary Loan request. When you search for a journal title in this database, you will see a small black and white referee icon. This indicates that the journal is peer reviewed. You can also check the journal publisher's website. It should indicate whether articles go through a peer-review process on a page that contains instructions for authors.

In this entry for the "Journal of Social Work," there is a small black and white "referee" icon, which indicates that the journal is peer reviewed. The "referee" icon is enclosed in a red square.

University Library

Start your research.

- Research Process

- Find Background Info

- Find Sources through the Library

- Evaluate Your Info

- Cite Your Sources

- Evaluate, Write & Cite

WHY START WITH LIBRARY SEARCH?

Library search.

► Is a search platform with ONLINE TEXTS (and print ones as well)

► Covers a broad range of research TOPICS

► It includes academic and other sources TYPES relevant to the needs of researchers

► Has FILTERS that make sorting through sources convenient and easy!

HOW TO USE LIBRARY SEARCH & MANAGE RESULTS

Library search has two entry points:.

Image Caption: On the left, The Library home page search box. On the right, The Library Search homepage.

Depending on where you begin your search (Library home page or the Library Search itself) this may affect how you employ the following things:

Search . Simply enter your keywords as you would on a search engine like Google.

► Try a keyword search;

► Add or remove words as needed;

► If a word doesn't seem to be working replace it with a synonym.

► Search is iterative. The more you learn about a topic the more confident you'll become with your searches. If you're not feeling confident after a day or so, let one of us at the library know [link to appointments]

Sign in. This truly depends on where you start your search. Signing in provides you with access to materials that are available only to UCSC students and other affiliates. The moment you have a chance, Sign in:

► Look for the yellow banner reminding you to sign in, or

► Look for the Sign in link in the upper right hand corner.

Results. Results can be overwhelming. Or maybe you only look at the first page of results anyway. Notice:

► The results count;

► LOAD MORE RESULTS link at the end/bottom of the results.

Filters. Are your friend. Use these to focus your results. Filters to make note of:

► SHOW ONLY: "Peer Review" & "Open Access"

► RESOURCE TYPES: "Articles," "Book Chapters," "Books," "Newspaper articles," "Images" and MANY OTHERS

► DATES

Access. Some things will be available online only and some will be available in the library only (for you to check out). Look for:

► Available online and follow the links provided

► For physical items in the library, look for a call number to be able to find these

WHEN & HOW TO MOVE ON TO OTHER DATABASES

Library search should provide sufficient research materials for most student research projects. Reasons to use different database:

- Your Library Search results lack the depth needed for your research project.

- You're conducting searches for a paper in your major, and feel lost by the results in Library Search.

- You need sources from a disciplinary perspective, for example methods, theories, scholarly conversations, etc.

Start by findind a database in your discipline or subject:

- All Library Subject Guides These guides are organized by Subject. They list the most relevant databases for finding journal articles and other research by subject.

Some frequently used databases include:

Database Tutorial

Take the Academic Search Complete Tutorial!

This tutorial provides an intro to this multidisciplinary database. This database includes articles from a broad range of topics, many with full text. After completing this tutorial you'll be able to:

- conduct and focus a basic search

- view full text if available

cite and email search results to yourself

- << Previous: Find Background Info

- Next: Evaluate Your Info >>

Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License except where otherwise noted.

Land Acknowledgement

The land on which we gather is the unceded territory of the Awaswas-speaking Uypi Tribe. The Amah Mutsun Tribal Band, comprised of the descendants of indigenous people taken to missions Santa Cruz and San Juan Bautista during Spanish colonization of the Central Coast, is today working hard to restore traditional stewardship practices on these lands and heal from historical trauma.

The land acknowledgement used at UC Santa Cruz was developed in partnership with the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band Chairman and the Amah Mutsun Relearning Program at the UCSC Arboretum .

*Get Started with Research*

- Identify your topic

- Create a search strategy

- Find Books and ebooks

- Find Articles

- Find Articles in Newspapers

- Types of Sources

- Evaluate Sources

- Understanding Plagiarism

Need research assistance? Click to Meet with a Librarian

Contact the library: Call us at 401-341-2289 Email us at [email protected] Chat with us from any library web page Visit us at the information desk Find us in the staff directory

Finding the right database

To find articles at the library, you need to use databases. Databases are organized collections of resources (articles, ebooks, music, videos, images, datasets, etc.) that are structured to make the information accessible to users. Databases can be interdisciplinary, containing resources on many subjects and fields of study, or they can be subject-specific with resources that are especially useful for particular disciplines.

To access the library databases available at McKillop Library, see the A-Z Databases list for an alphabetical listing of over 140 databases available to the Salve community.

To view databases by subject, simply navigate to the "All Subjects" pull-menu. See below.

Basic and Advanced Searching in the Databases

Basic Searching

The most basic way to begin searching for articles is to place your search statement (see Creating Search Statements ) in the first box. If you were interested in exploring how attitudes towards tattoos have evolved in America, you could start out by search "tattoo AND America."

Advanced Searching

In addition to basic searching, you can also use advanced search features to create a more precise search. You can use different Boolean operators to build your search string. You can also utilize the "Select a Field" option to search by a range of fields including author, title, and journal name.

*Note: All pictured examples of database searching on this page are from Academic Search Complete, an interdisciplinary database that is managed by EBSCOhost. Other databases will likely have similar features, but they will look a little different.

Finding Relevant Subject Terms

Like the library catalog, many databases will provide subject terms for specific resources. These may be referred to under different terminology, including subjects, subject thesaurus terms, or thesaurus terms. Subject terms are standardized words or phrases that describe the main idea of the source you are looking at. These terms are hyperlinked in databases, so you can select them to have the database generate a new result list with other resources that share the same subject term. Subject terms will vary from one database to another. Likewise, they will probably be different from the subject terms in the library catalog. As with your keywords, you should note any especially helpful subject terms as you conduct your research (as well as which database or search tool you found them in!).

Search for articles

Find Articles in Select Ebscohost Databases...

Google scholar: linking salve's resources to your google scholar account.

Google Scholar is a great tool for certain type of research questions that require journal articles. If you have a Google account you have a Google Scholar account. You can link this account to Salve's library to have your Google Scholar results directly link to the full-text of articles Salve subscribes to.

1. Sign into your Google account

2. Go to Google Scholar settings: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_preferences

3. Select “library links,” enter “Salve Regina” check “Salve Regina University Library – Find @ Salve,” and click Save.

5. In the results, you'll see a "Find @ Salve" link to the right of the article.

Google Scholar does not include all of Salve’s article subscriptions in its results. If you don’t find your article there, search using the library’s journals button.

- << Previous: Find Books and ebooks

- Next: Find Articles in Newspapers >>

- Last Updated: Apr 10, 2024 12:10 PM

- URL: https://salve.libguides.com/researchbasics

- University of Michigan Library

- Research Guides

Essentials of Library Research

- Finding Articles & Journals

- Getting Started

- Choosing Your Topic

- Finding Books & Media

- Evaluating Information

- Citing Sources

Why Use Library Databases

Recommended Databases

Need articles for your library research project, but not sure where to start? We recommend these top ten article databases for kicking off your research. If you can't find what you need searching in one of these top ten databases, browse the list of all library databases by subject (academic discipline) or title .

- U-M Library Articles Search This link opens in a new window Use Articles Search to locate scholarly and popular articles, as well as reference works and materials from open access archives.

- ABI/INFORM Global This link opens in a new window Indexes 3,000+ business-related periodicals (with full text for 2,000+), including Wall Street Journal.

- Academic OneFile This link opens in a new window Provides indexing for over 8,000 scholarly journals, industry periodicals, general interest magazines and newspapers.

- Access World News [NewsBank] This link opens in a new window Full text of 600+ U.S. newspapers and 260+ English-language newspapers from other countries worldwide.

- CQ Researcher This link opens in a new window Noted for its in-depth, unbiased coverage of health, social trends, criminal justice, international affairs, education, the environment, technology, and the economy.

- Gale Health and Wellness This link opens in a new window Provides access to medical, health, and wellness information from authoritative medical sources.

- Humanities Abstracts (with Full Text) This link opens in a new window Covers 700 periodicals in art, film, journalism, linguistics, music, performing arts, philosophy, religion, history, literature, etc.

- JSTOR This link opens in a new window Full-text access to the archives of 2,600+ journals and 35,000+ books in the arts, humanities, social sciences and sciences.

- ProQuest Research Library This link opens in a new window Indexes over 5,000 journals and magazines, academic and popular, with full text included for over 3,600.

- PsycInfo (APA) This link opens in a new window Premier resource for surveying the literature of psychology and adjunct fields. Covers 1887-present. Produced by the APA.

Finding Databases

The U-M Library subscribes to hundreds of databases which gives you access to thousands of journals and articles. The following video explains how you can find the appropriate database for your research needs

In addition to finding datases, the Journal search allows you to search for journals available at U-M. If you know the title of the journal you can enter it into the search box. If you are not looking for a specific journal you can browse by discipline. If U-M doesn’t own the journal you are looking for, we can obtain copies of articles for you via interlibrary loan .

Finding & Accessing Articles Using Library Search

The U-M Library Articles Search is a gateway to discovering a wide range of library resources. Please watch the video below on how to effectively and efficiently use Library Search.

Articles & Databases

Explore our collection of hundreds of online resources and databases. Use our free online content to help with your research, whether it's finding a single article, tracing a family tree, learning a new language, or anything in between.

Featured Resources

.css-1t84354{transition-property:var(--nypl-transition-property-common);transition-duration:var(--nypl-transition-duration-fast);transition-timing-function:var(--nypl-transition-easing-ease-out);cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;outline:2px solid transparent;outline-offset:2px;color:var(--nypl-colors-ui-link-primary);text-decoration-style:dotted;text-decoration-thickness:1px;text-underline-offset:2px;}.css-1t84354:hover,.css-1t84354[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;color:var(--nypl-colors-ui-link-secondary);text-decoration-style:dotted;text-decoration-thickness:1px;}.chakra-ui-dark .css-1t84354:hover:not([data-theme]),.chakra-ui-dark .css-1t84354[data-hover]:not([data-theme]),[data-theme=dark] .css-1t84354:hover:not([data-theme]),[data-theme=dark] .css-1t84354[data-hover]:not([data-theme]),.css-1t84354:hover[data-theme=dark],.css-1t84354[data-hover][data-theme=dark]{color:var(--nypl-colors-dark-ui-link-secondary);}.css-1t84354:focus,.css-1t84354[data-focus]{box-shadow:var(--nypl-shadows-outline);}.chakra-ui-dark .css-1t84354:not([data-theme]),[data-theme=dark] .css-1t84354:not([data-theme]),.css-1t84354[data-theme=dark]{color:var(--nypl-colors-dark-ui-link-primary);}.css-1t84354:visited{color:var(--nypl-colors-ui-link-tertiary);}.chakra-ui-dark .css-1t84354:visited:not([data-theme]),[data-theme=dark] .css-1t84354:visited:not([data-theme]),.css-1t84354:visited[data-theme=dark]{color:var(--nypl-colors-dark-ui-link-tertiary);}.css-1t84354 a:hover,.css-1t84354 a[data-hover]{color:var(--nypl-colors-ui-link-secondary);}.css-1t84354 screenreaderOnly{clip:rect(1px, 1px, 1px, 1px);height:1px;overflow:hidden;position:absolute!important;width:1px;word-wrap:normal;} Start Your Research

Not sure where to begin? From primary sources to scholarly articles, start your research with resources chosen by our expert librarians.

Homework Help

Discover the wide range of learning resources the Library has to offer students of all ages, from chemistry and history to English and math.

Newspapers and Magazines

Browse popular contemporary and historic publications including The New York Times , People magazine, and Sports Illustrated among others.

World Languages

Read e-books, newspapers, and more in languages including Spanish, Chinese, Russian, and French.

African American Studies

Explore a variety of academic, historic, and cultural resources curated by the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Performing Arts

Find materials about theatre, film, dance, music, and recorded sound selected by The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

New York City History

Uncover primary and secondary sources about the five boroughs, including neighborhood data, historic photos, newspaper archives, and more.

Trace ancestry information and family trees through public records, historical documents, and other genealogical archives.

Job Search and Career Development

Whether you’re looking for a new job or changing careers, these resources will help you find training tutorials, resume guides, and more.

Most Popular

.css-1t84354{transition-property:var(--nypl-transition-property-common);transition-duration:var(--nypl-transition-duration-fast);transition-timing-function:var(--nypl-transition-easing-ease-out);cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;outline:2px solid transparent;outline-offset:2px;color:var(--nypl-colors-ui-link-primary);text-decoration-style:dotted;text-decoration-thickness:1px;text-underline-offset:2px;}.css-1t84354:hover,.css-1t84354[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;color:var(--nypl-colors-ui-link-secondary);text-decoration-style:dotted;text-decoration-thickness:1px;}.chakra-ui-dark .css-1t84354:hover:not([data-theme]),.chakra-ui-dark .css-1t84354[data-hover]:not([data-theme]),[data-theme=dark] .css-1t84354:hover:not([data-theme]),[data-theme=dark] .css-1t84354[data-hover]:not([data-theme]),.css-1t84354:hover[data-theme=dark],.css-1t84354[data-hover][data-theme=dark]{color:var(--nypl-colors-dark-ui-link-secondary);}.css-1t84354:focus,.css-1t84354[data-focus]{box-shadow:var(--nypl-shadows-outline);}.chakra-ui-dark .css-1t84354:not([data-theme]),[data-theme=dark] .css-1t84354:not([data-theme]),.css-1t84354[data-theme=dark]{color:var(--nypl-colors-dark-ui-link-primary);}.css-1t84354:visited{color:var(--nypl-colors-ui-link-tertiary);}.chakra-ui-dark .css-1t84354:visited:not([data-theme]),[data-theme=dark] .css-1t84354:visited:not([data-theme]),.css-1t84354:visited[data-theme=dark]{color:var(--nypl-colors-dark-ui-link-tertiary);}.css-1t84354 a:hover,.css-1t84354 a[data-hover]{color:var(--nypl-colors-ui-link-secondary);}.css-1t84354 screenreaderonly{clip:rect(1px, 1px, 1px, 1px);height:1px;overflow:hidden;position:absoluteimportant;width:1px;word-wrap:normal;} novelny resources.

NOVELny Resources are available to all New Yorkers without a password as long as one is in New York State, via a NY driver or non-driver ID if not currently in New York State and/or via a Library Card.

A searchable, digitized archive -- from the first date of publication to the last three to five years -- of major scholarly journals in many academic fields.

Access to this resource has been temporarily expanded to NYPL cardholders working from home, courtesy of JSTOR.

Ancestry Library Edition

Access billions of names in thousands of genealogical databases including Census and Vital Records, birth, marriage and death notices, the Social Security Death Index, Passenger lists and naturalizations, Military and Holocaust Records, City Directories, New York Emigrant Savings Bank records, and African American and Native American Records. Library version of Ancestry.com.

***PLEASE NOTE THAT TEMPORARY REMOTE ACCESS TO THIS DATABASE HAS BEEN TERMINATED.***

Library DIY for Online and Distance Students

- Get Started

- Library Accounts and Services

- Starting Research

- Finding Articles

- Finding Ebooks

- Finding Specific Items

- Accessing Physical Items for Distance Students

- Using Databases

- Evaluating Sources

- Citing Sources

Chat with a Librarian

Finding Articles Options

I need to find peer-reviewed articles I don't know if this article is peer-reviewed I need to find newspaper articles I need to find a specific article A website wants me to pay for this article I found too many or too few articles on my topic I found one perfect article for my topic and need more like it I can't find the full-text of this article

Finding Peer-Reviewed Articles

- Finding Peer-Reviewed Articles Tutorial - PDF Version A text and image based version of the Finding Peer-Reviewed Articles tutorial for offline use.

In order to find peer-reviewed articles, first make sure you're familiar with what peer-reviewed articles are .

The most common place to find peer-reviewed articles is in library databases. Library databases have advanced search features that make finding appropriate articles easier, and provide the most options for obtaining the full text of articles. The quickest way to find the article databases is the Article Databases link under Find, Borrow, Request on the library homepage. Tutorials are available for learning how to use specific databases .

If you're not sure which database you need to be searching in, or just want to start with a very broad search, you can use the Articles Search , which is the second tab on the library's main search box. It searches several different databases at once.

You can also find scholarly articles - though not always the full-text of them - in Google Scholar. This works best if you follow the logging in instructions to set up Google Scholar to work with Bradley's library.

- How to Get Bradley Library Resources Through Google Scholar These instructions will show you how to adjust the settings in Google Scholar so that it can show you full-text options available through the library.

Many databases contain a mixture of both peer-reviewed articles and non-scholarly, non-peer-reviewed articles. Most databases also provide a filter to let you limit your results to only articles from peer-reviewed journals. Look for a checkbox or a filter option labelled "Peer-Reviewed Journals" and make sure it is checked. Sometimes it will be on the advanced search screen.

Sometimes you can apply the peer-reviewed filter after you have gotten your initial search results.

These filters apply only to peer-reviewed journals. This means that the journal has a peer-review process in place for its research articles. However, these journals may still contain other kinds of articles, such as book reviews or essays. Therefore, when you find an article that looks relevant to your topic, you still need to evaluate whether an individual article has been peer-reviewed .

Main Menu ^ Top of Page

What are Peer-Reviewed Articles?

- What are Peer-Reviewed Articles - PDF Tutorial A text and image based version of the 'what are peer-reviewed articles' tutorial.

Peer-reviewed articles play an important role in the spreading of new research in a given field. These articles have the following characteristics:

- They contain original research completed by experts in the field

- Before being published, they have been reviewed both by editors and by the authors' peers, who are also experts in the field

- The review process includes questioning the content, methodology, and findings of the article

- Authors are expected to revise and improve their work based on feedback from this process before the article can be published

Peer-reviewed articles may also be referred to as research articles, scholarly articles, or academic articles. All these terms describe the same type of article.

Who publishes Peer-Reviewed Articles?

Peer-reviewed articles are normally to be found in scholarly journals. Scholarly journals are easiest to access through library databases, which often have features that can help you recognize this kind of journal. A journal that publishes peer-reviewed articles may also publish content that is not peer-reviewed, such as book reviews or opinion columns, so identifying a journal as scholarly doesn't mean everything inside it is a scholarly article. You'll need to evaluate the article by itself as well. However, confirming that the journal is scholarly and has a peer-review process in place makes it more likely that an article you find inside it will be peer-reviewed.

Here are ways you can identify a scholarly journal :

When searching in a database, search results will sometimes have icons next to them that indicate what kind of publication they come from. Here is one example from a psychology database.

Here is an example from a nursing database.

In most databases, if you click on the title of the article, and then click on the title of the journal from the item page, it will give you more information about that journal, including whether or not it uses peer-review.

How Can I Recognize Peer-Reviewed Articles?

Peer-reviewed articles often follow very specific guidelines for how they are written and formatted. These guidelines may vary based on what discipline the author is doing research in, but generally a scholarly article will have the following attributes:

- The authors' names are listed, along with any positions they may hold at academic institutions, indicating that they writing from their position as academics/researchers

- An abstract, or summary of the article's contents, is provided at the beginning of the article

- A list of references or works cited is included

- The body of the article quotes or refers to work from other scholarly articles (check the references or works cited page to see if the quoted works were published in scholarly journals!)

- The body of the article describes research performed by the authors, including their methodology or process, their results, and any conclusions they drew from their research

Articles that are not scholarly may sometimes include some of the same attributes as scholarly articles. To identify a scholarly article, look to see if the article has a majority of these characteristics.

Resources for Understanding and Identifying Peer-Reviewed Articles

- Anatomy of a Scholarly Article An interactive example from NCSU Libraries that can show you how to identify common elements of a scholarly/peer-reviewed article.

Finding Newspaper Articles

- Findings Newspaper Articles PDF Version A text and image based version of the finding newspaper articles tutorial.

If you specifically need to find newspaper articles on your topic, there are two options through the library website. Using the library website is a starting point is a good way to make sure you don't run into a paywall or have to pay unnecessarily for news articles.

Find a Specific Newspaper

If you would like to find articles from a specific newspaper, you can search for the title of the newspaper using the Journals Available search within the catalog. Even though it's called Journals Available, it includes magazines and newspapers as well.

You can find the Journals Available search within the library catalog, in the row of links at the top.

Once there, you can search for the title or ISSN of the newspaper you are interested in. After hitting search, results will be listed below the search box. Newspapers that are available online will have links labelled Available Online underneath their title. You can click on this link to be taken directly to the database that contains the newspaper, or click on the title of the newspaper to get more information about it.

Search Inside a News Database