- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

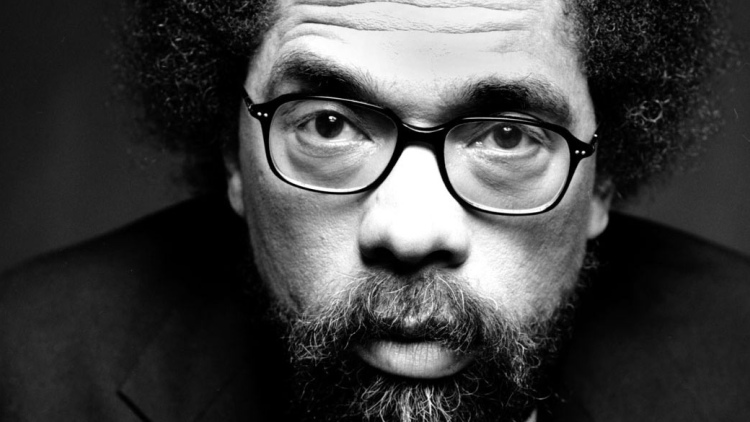

John Dewey (1859–1952) was one of American pragmatism’s early founders, along with Charles Sanders Peirce and William James, and arguably the most prominent American intellectual for the first half of the twentieth century. Dewey’s educational theories and experiments had global reach, his psychological theories influenced that growing science, and his writings about democratic theory and practice helped shape academic and practical debates for decades. Dewey developed extensive and often systematic views in ethics, epistemology, logic, metaphysics, aesthetics, and philosophy of religion. Because Dewey’s approach was typically genealogical, couching his views within philosophy’s larger history, one finds in Dewey a fully developed metaphilosophy.

Dewey’s “cultural naturalism” (which he favored over “pragmatism” and “instrumentalism”) is a critique and reconstruction of philosophy within the ambit of a Darwinian worldview (Lamont 1961; MW4: 3). Following William James, Dewey thought philosophy had become overly technical and intellectualistic, divorced from assessing everyday social conditions and values ( FAE , LW5: 157–58). Philosophy, he believed, needed to be reconnected with education-for-living (philosophy as “the general theory of education”), viz., social criticism at the most general level, a “criticism of criticisms” ( EN , LW1: 298; see also DE , MW9: 338).

Understood within the Darwinian evolutionary arena, philosophy becomes an activity taken by interdependent organisms-in- environments. From this standpoint of active adaptation, Dewey criticized traditional philosophers’ tendency to abstract and reify concepts derived from living contexts. Along with other classical pragmatists, Dewey critiqued metaphysical and epistemological dualisms (e.g., mind/body, nature/culture, self/society, and reason/emotion) reconstructing their elements as parts of larger continuities. For example, human thinking is not a phenomenon categorically external from the world it seeks to know; indeed, such knowing is not a purely rational attempt to escape illusion and discover ultimate “reality” or “truth”. Rather, knowing is one among many ways organisms with evolved capacities for thought and language cope with problems. Minds, then, are not passive observers but are engines of active adaptation, experimentation, and innovation; ideas and theories are not rational fulcrums to transcend culture, but rather function within culture, adjudged on situated, pragmatic grounds. Knowing, then, is no “divine spark”, for while knowing (or inquiry , to use Dewey’s term) includes calculative or rational elements, these are agentially entangled with the body and emotions.

Beyond academia, Dewey was an active public intellectual, infusing contemporary issues with insights found in philosophy. He addressed topics of broad moral significance, such as human freedom, economic alienation, race relations, women’s suffrage, war and peace, and educational methods and goals. Typically, he integrated discoveries made via public inquiries back into his academic theories. This practice-theory-practice rhythm powered every area of Dewey’s intellectual enterprise, and perhaps explains the enduring usefulness of his philosophy in many academic and practical arenas. The fecundity of Dewey’s ideas continues to manifest in aesthetics, education, environmental policy, information theory, journalism, medicine, political theory, psychiatry, public administration, sociology, and philosophy, per se.

Short Chronology of the Life and Work of John Dewey

2.1 associationism, introspectionism, and physiological psychology, 2.2 the “reflex arc” and dewey’s reconstruction of psychology, 2.3 instincts/impulses, 2.4 perception/sensation, 2.5 acts and habits, 2.6 emotion, consciousness, 3.1 the development of “experience”, 3.2 traditional views of experience and dewey’s critique, 3.3 dewey’s positive account of experience, 3.4 metaphysics, 3.5 the development of “metaphysics”, 3.6 the project of experience and nature, 3.7 empirical metaphysics and wisdom, 3.8 criticisms of dewey’s metaphysics, 4.1 the organic roots of instrumentalism, 4.2 beyond empiricism, rationalism, and kant, 4.3 inquiry, knowledge, and truth, 5.1 experiential learning and teaching, 5.2 traditionalists, romantics, and dewey, 5.3 democracy through education, 7. political philosophy, 8. art and aesthetic experience, 9.1 dewey’s religious background, 9.2 aligning naturalism and religion, 9.3 “religion” vs. “religious”, 9.4 faith and god, 9.5 religion as social intelligence—a common faith, collections, abbreviations of dewey works frequently cited, individual works, b. secondary sources, other internet resources, related entries, 1. biographical sketch.

John Dewey lead an active and multifarious life. He is the subject of numerous biographies and an enormous literature interpreting and evaluating his extraordinary body of work: forty books and approximately seven hundred articles in over one hundred and forty journals.

Dewey was born in Burlington, Vermont on October 20, 1859 to Archibald Dewey, a merchant, and Lucina Rich Dewey. Dewey was the third of four sons; the first, Dewey’s namesake, died in infancy. He grew up in Burlington, was raised in the Congregationalist Church, and attended public schools. After studying Latin and Greek in high school, Dewey entered the University of Vermont at fifteen and graduated in 1879 at nineteen. After college, Dewey taught high school for two years in Oil City, Pennsylvania. Subsequent time in Vermont studying philosophy with former professor H.A.P. Torrey, along with the encouragement of the editor of the Journal of Speculative Philosophy , W.T. Harris, helped Dewey decide to attend graduate school in philosophy at Johns Hopkins University in 1882. There, his study included logic with Charles S. Peirce (which Dewey found too “mathematical”, and did not pursue), the history of philosophy with George Sylvester Morris, and physiological and experimental psychology with Granville Stanley Hall (who trained with Wilhelm Wundt in Leipzig and with William James at Harvard). [ 1 ]

Though Dewey later attributed important credit to Peirce’s pragmatism for his mature views, Peirce had no sizable impact during graduate school. There, his main influences—Neo-Hegelian idealism, Darwinian biology, and Wundtian experimental psychology— created a tension he fought to resolve. Was the world fundamentally biological, functional, and material or was it inherently creative and spiritual? In no small part, Dewey’s career was launched by his attempt to mediate and harmonize these views. While sharing the idea of “organism”, Dewey also saw in both — and rejected— any aspects he deemed overly abstract, atomizing, or reductionistic. His earliest attempts to create a “new psychology” (aimed at merging experimental psychology with idealism) sought a method to understand experience as integrated and whole. As a result, Dewey’s early approach modified English absolute idealism. In 1884, two years after matriculating, Dewey graduated with a dissertation criticizing Kant from an Idealist position (“The Psychology of Kant”); it remains lost.

While scholars still debate the degree to which Dewey’s mature philosophy retained early Hegelian influences, Hegel’s personal influence on Dewey was profound. New England’s religious culture, Dewey recalled, imparted an “isolation of self from the world, of soul from body, [and] of nature from God”, and he reacted with “an inward laceration” and “a painful oppression”. His study (with George Sylvester Morris) of British Idealist T.H. Green and G.W.F. Hegel afforded Dewey personal and intellectual healing:

Hegel’s synthesis of subject and object, matter and spirit, the divine and the human, was, however, no mere intellectual formula; it operated as an immense release, a liberation. Hegel’s treatment of human culture, of institutions and the arts, involved the same dissolution of hard-and-fast dividing walls, and had a special attraction for me. ( FAE , LW5: 153)

Philosophically, early encounters with Hegelianism informed Dewey’s career-long quest to integrate, as dynamic wholes, the various dimensions of experience (practical, imaginative, bodily, psychical) that philosophy and psychology had defined as discrete.

Dewey’s family, as well as his reputation as a philosopher and psychologist, grew while at various universities, including the University of Michigan (1886– 88, 1889–1894) and the University of Minnesota (1888–89). At Michigan, Dewey developed long-term professional relationships with James Hayden Tufts and George Herbert Mead. In 1886, Dewey married Harriet Alice Chipman; they had six children and adopted one. Two of the boys died tragically young (two and eight). Chipman had a significant influence on Dewey’s advocacy for women and his shift away from religious orthodoxy. During this period, Dewey wrote articles critical of British idealists from a Hegelian perspective; he taught James’ Principles of Psychology (1890), and labeled his own view “experimental idealism” (1894a, The Study of Ethics , EW4: 264).

In 1894, at Tuft’s urging, President William Rainey Harper offered Dewey leadership of the Philosophy Department at the University of Chicago, which also included Psychology and Pedagogy. Motivated to put these disciplines into active collaboration, Dewey accepted and began building the department by hiring G.H. Mead from Michigan and J.R. Angell, a former student at Michigan (who also studied with James at Harvard). Dubbed the “Chicago School” by William James, Dewey, Tufts, Angell, Mead and several others developed “psychological functionalism”. He also published the seminal “Reflex Arc Concept in Psychology” (1896, EW5; hereafter RAC ), and broke from transcendental idealism and his church.

At Chicago, Dewey founded The Laboratory School, a site to test psychological and educational theories. Dewey’s wife Alice was the principal from 1896–1904. Dewey became active in Chicago’s social and political causes, including Jane Addams’ Hull House; Addams became a close personal friend of the Dewey’s. Dewey and his biographer, daughter Jane Dewey, credited Addams with helping him develop his views on democracy, education, and philosophy. The significance of Dewey’s intellectual debt to Addams is still being uncovered (“Biography of John Dewey”, Dewey 1939a; see also Seigfried 1999, Fischer 2013).

In 1904, conflicts related to the Laboratory School lead Dewey to resign his Chicago positions and move to the philosophy department at Columbia University in New York City. There, he established an affiliation with Columbia’s Teacher’s College. Important influences at Columbia included F.J.E. Woodbridge, Wendell T. Bush, W.P. Montague, Charles A. Beard (political theory) and Franz Boas (anthropology). Dewey retired from Columbia in 1930, going on to produce eleven more books.

In addition to many significant academic publications, Dewey wrote for various non-academic audiences, notably in the New Republic ; he was active in leading, supporting, or founding a number of important organizations including the American Civil Liberties Union, the American Association of University Professors, the American Philosophical Association, the American Psychological Association, and the New School for Social Research. Dewey spoke out to support progressive politics and social change. His renown as a philosopher and educator lead to numerous invitations; in 1922, he inaugurated the Paul Carus Lectures (revised and published as Experience and Nature , 1925), gave the 1928 Gifford Lectures (revised and published as The Quest for Certainty , 1929), and gave the 1933–34 Terry Lectures at Yale (published as A Common Faith , 1934a). He traveled for two years in Japan and China, and made notable trips to Turkey, Mexico, the Soviet Union, and South Africa.

In 1946, almost two decades after Alice Chipman Dewey died (1927), Dewey married Roberta Lowitz Grant. John Dewey died of pneumonia in his home in New York City on June 1, 1952.

Source: H&A 1998, xiv

- 1859 Oct. 20. Born in Burlington, Vermont

- 1879 Receives A.B. from the University of Vermont

- 1879–81 Teaches at high school in Oil City, Pennsylvania

- 1881–82 Teaches at Lake View Seminary, Charlotte, Vermont

- 1882–84 Attends graduate school at Johns Hopkins University

- 1884 Receives Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins University

- 1884 Instructor in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Michigan

- 1886 Married to Alice Chipman

- 1888–89 Professor of Philosophy at the University of Minnesota

- 1889 Chair of Department of Philosophy at the University of Michigan

- 1894 Professor and Chair of Department of Philosophy (including psychology and pedagogy) at the University of Chicago

- 1897 Elected to Board of Trustees, Hull-House Association

- 1899 The School and Society

- 1889–1900 President of the American Psychological Association; Studies in Logical Theory

- 1904 Professor of Philosophy at Columbia University

- 1905–06 President of the American Philosophical Society

- 1908 Ethics

- 1910 How We Think

- 1916 The Influence of Darwin on Philosophy, Democracy and Education, Essays in Experimental Logic

- 1919 Lectures in Japan

- 1919–21 Lectures in China

- 1920 Reconstruction in Philosophy

- 1922 Human Nature and Conduct

- 1924 Visits schools in Turkey

- 1925 Experience and Nature

- 1926 Visits schools in Mexico

- 1927 The Public and its Problems

- 1927 Death of Alice Chipman Dewey

- 1928 Visits schools in Soviet Russia

- 1929 The Quest for Certainty

- 1930 Individualism, Old and New

- 1930 Retires from position at Columbia University, appointed Professor Emeritus

- 1932 Ethics

- 1934 A Common Faith, Art as Experience

- 1935 Liberalism and Social Action

- 1937 Chair of the Trotsky Commission, Mexico City

- 1938 Logic: The Theory of Inquiry, Experience and Education

- 1939 Freedom and Culture, Theory of Valuation

- 1946 Married to Roberta (Lowitz) Grant; Knowing and the Known

- 1952 June 1. Dies in New York City

2. Psychology

Dewey’s involvement with psychology began early. He hoped the emerging discipline would answer philosophy’s deepest questions. His initial approach resembled Hegelian Idealism, though it did not incorporate Hegel’s dialectical logic; instead he sought new methods in psychology (Alexander 2020). By overcoming longstanding divisions (between subject and object, matter and spirit, etc.) he would show how human experiences —physical, psychical, practical, and imaginative —all integrate in one, dynamic person ( FAE , LW5: 153). Dewey’s large ambitions for psychology (as the new science of self-consciousness), imagined it as the “completed method of philosophy” (“Psychology as Philosophic Method”, EW1: 157). Nominally a textbook, Psychology (1887 EW2) introduced psychology’s study of the self as ultimate reality.

Dewey developed his own psychological theories. Extant accounts of behavior were flawed, premised upon outdated and false philosophical assumptions. (He eventually judged that such larger questions about the meaning of human existence exceeded the resources of psychology.) Dewey’s work at this time reconstructed components of human conduct (instincts, perceptions, habits, acts, emotions, and conscious thought) and these proved integral to later, mature accounts of experience. They informed his lifelong contention that mind, contrary to long tradition, is not fundamentally subjective and isolated, but social and interactive, emerging in nature and culture.

Dewey’s entry into psychology coincided with two dominant trends: introspectionism (arising from associationism, a.k.a., “mentalism”) and the newer physiological psychology (imported from Germany). Earlier British empiricists, such as John Locke and David Hume, explained intelligent behavior with (1) internally inspected (“introspected”) entities, including perceptual experiences (e.g., “impressions”), and (2) thoughts or ideas (e.g., “images”). These accrue toward intelligence via an elaborate process of associative learning. Discovery-by-introspection was indispensable to many empiricists, and to physiological cum experimental psychologists (e.g., Wundt).

Dewey was deeply influenced by graduate study of physiological psychology with G. Stanley Hall, whose classes included theoretical, physiological, and experimental psychology. Dewey conducted laboratory experiments on attention. Unlike the introspectionists, Hall’s methods incorporated strict experimental controls, a biology-based approach which proffered Dewey an organic and holistic model of experience capable of overcoming the subjectivist dualisms plaguing the older, associationist models. [ 2 ] However, Dewey still found experience atomized and mechanistic in physiological psychology, stemming from a reliance upon “sense data”. From his Hegelian perspective, this psychology could never account for a wider, socio-cultural world. Briefly, for Dewey, “organism” entails “environment” and “environment” entails “culture”. A rigorously empirical psychology could restrict study to “the” mind but was bound to forge connections with other sciences. [ 3 ]

Dewey sought an account of psychological experience that respected experimental limits and culture’s pervasive influences. James’s tour de force, The Principles of Psychology (1890), modeled how to explain the conscious and intelligent self without appealing to a transcendental Absolute. The Principles’ emphatically biological conception of mind, Dewey recalled, gave his thinking “a new direction and quality” and “worked its way more and more into all my ideas and acted as a ferment to transform old beliefs” ( FAE , LW5: 157). Rather than measuring psychic phenomena against preexisting abstractions, it deployed a “radical empiricism” that starts from lived experience’s actual phases and elements and aims to understand its functional origins.

One expression of this Jamesean turn was Dewey’s seminal critique of the reflex arc concept (1896). The “reflex arc” model of behavior was an influential way to empirically and experimentally explain human behavior using stimulus-response (cause-effect) pairings. It sought to displace less observable and testable approaches relying upon “psychic entities” or “mental substance”. In the model, a passive organism encounters an external stimulus, causing a sensory and motor response — a child sees a candle (stimulus), grasps it (response), burns her hand (stimulus), and pulls her hand back (response). This makes explicit the event’s basic stimuli and responses, describing connections in mechanistic and physiological terms. No recourse to mysterious and unobservable entities is necessary.

Dewey criticized the reflex arc on several grounds. First, events (sensory stimulus, central response, and act) are artificially separated for purposes of analysis. “The reflex arc”, Dewey wrote, “is not a comprehensive, or organic unity, but a patchwork of disjointed parts, a mechanical conjunction of unallied processes” ( RAC , EW5: 97). Second, the model falsifies genuine interaction; organisms do not passively receive stimuli and then actively respond; rather, organisms continuously interact with environments in cumulative and modifying ways. The child encountering a candle is already actively exploring, anticipating; noticing a flame modifies ongoing actions. “The real beginning is with the act of seeing; it is looking, and not a sensation of light” ( RAC , EW5: 97). Third, the model too rigidly designates certain events ( the stimulus, the response); it reifies them and ignores a wider, ongoing matrix of activity. Effectively, Dewey was pointing out the ironic fact that the reflex arc model — intending to shed metaphysical assumptions — was inadvertently creating new ones. We are seeking to discover, Dewey argued, “what stimulus or sensation, what movement and response mean ” and we are finding that “they mean distinctions of flexible function only, not of fixed existence ” ( RAC , EW5: 102; emphasis mine). His suggestion is pragmatic; rather than an underlying reality ( pure stimulus, pure response), psychology should look to meanings. Pragmatically, then, terms such as stimulus, response, sensation, and movement “mean distinctions of flexible function only, not of fixed existence” ( RAC , EW5: 102). Meanings of terms are understood once they are seen as functional acts in a dynamic context that includes aims and interests. [ 4 ]

Dewey’s critique and reconstruction of the reflex arc presaged other important developments in his pragmatism. The wider lesson was the need to pay greater attention to context and function, and he applied it over his career to science more broadly, and to logic and mathematics. This was a warning not to mistake analyses’ eventual outcomes as evidence for already-existing entities. [ 5 ] It was also a reminder that specific applications of theory earned salience by their value in a longer temporal context, checked both prospectively and retrospectively.

Rather than recount Dewey’s extensive reconstruction of the human self, here is a cursory review to illustrate how he developed some basic notions: instincts/impulses, perceptions, sensations, habits, emotions, sentiency, consciousness, and mind.

James had already attacked attempts to explain complex, developed behavior by reference to preexisting impulses and instincts (e.g., “Habit”, James 1890: chapter 4); Dewey continued the assault. Such explanations fail to consider instinct’s plastic and pliable character. Across a variety of individuals, instincts considered simple or basic are anything but—they blossom into many different habits and customs. [ 6 ] Also, instincts are not pushing an essentially passive creature, but are actively taken up in diverse circumstances, for diverse purposes. “Instinct”, like “stimulus”, has meaning depending upon contextual factors which may include biological and socio-linguistic responses. There is no psychology without social psychology, no plausible inquiry into pure, biological instincts (or other “natural” powers) without consideration of social and environmental factors, let alone the particularities of a given inquiry. As interactive phenomena-in-environment, instincts/impulses are better framed as transactions ( HNC , MW14: 66).

Dewey’s argument about instincts applied to perception and sensation as well — do not base an empirical science on unquestioned, metaphysical posits, and do not rely upon strictly analytical methods that use simple elements to build up complex behavior. Too often, such methods are inadequate to explain psychological phenomena. Accordingly, Dewey attacked the then-common view that a perception (1) was simply and externally caused, (2) completely occupied a mental state, and (3) was passively received into an empty mental space.

Such elements grow out of an erroneous “psychophysical dualism” that radically separates perceiver from world. Consider (1), perception as causation. Perception as simply and externally caused is contravened by the Darwinian, ecological model. There, organism-environment interactions include, but are not ontologically reducible to , “minds”, “bodies”, and their impingements— the so-called “impressions” and “ideas” of modern philosophy. We do encounter surprising, unbidden events but such occurrences do not justify leaping to metaphysical conclusions, that there is a world “out there” and a mind “in here”.

While experience is profoundly qualitative, qualities are never simply received nor are they contextless. This new view of qualities rejects the longstanding dualism between “objective” and “subjective”. A lemon’s “yellowness” or “tartness” are neither in a perceiver nor in a lemon; each quality emerges from complex interactions that can later be characterized ( as “tartness”) for reasons germane to the inquiry. Dewey wrote,

The qualities never were ‘in’ the organism; they always were qualities of interactions in which both extra-organic things and organisms partake. ( EN , LW1: 198–199)

Thus, as discriminated, perceptions and qualities are made in inquiry and language, not reports of ontological entities that are simple, discrete, or ultimate. “Perception”, then, is shorthand for more complicated interacting events. “Red” abstracts from a more complex experience (e.g., red-car-merging-into-my-lane), and the pragmatic question becomes, What is the function of this abstraction? How does it mediate thought or action for future experiences? (“A Naturalistic Theory of Sense-Perception”, LW2: 51; EN , LW1: 198–199)

Regarding (2), perceptions pervading mental states, Dewey echoes James in “The Stream of Thought” (James 1890: chapter 9). While a perception may occupy mental focus, there is also an attendant “fringe” which contributes contrast and creates, in the wider situation, an “underlying qualitative character” (“Qualitative Thought”, LW5: 238 fn. 1). The aforementioned “tartness” of the lemon relies for its character upon a slew of “fringe” conditions (e.g., immediate past flavors, gustatory anticipations, etc.).

Finally, regarding passive reception (3), perception is already a “taking up” by organisms already functioning in situations; there is no instantaneous and passive apprehension of stimuli. Taking up always means selectivity, a process of adjustment that take some time. Perception is never naïve, never a confrontation with some “given” content already imbued with inherent meaning. Long before Wilfred Sellars (see entry on Sellars ) dismissed the passive-perception-encounter as modern empiricism’s “Myth of the Given”, Dewey had rebuked such claims. All seeing is seeing as —adjustments within larger acts. These habits of adjustment can change (subsequent selections and interpretations are modified), so what is perceived can shift ( DE , MW9: 346).

The 1896 “Reflex Arc” paper argued that simpler constituents are insufficient to explain complex behavior; Dewey found that the “act” provided a better starting point ( HNC , MW14: 105). Acts help organisms cope with their environment; they direct movement. Acts exhibit selectivity and express interest, which make things meaningful. Our ancestors’ selective acts to satisfy instinctive hunger resulted in choosing certain foods (safe) over others. Over time, more elaborate interest in food becomes social norms (dining, e.g.) and aesthetic expectations (cuisine).

Following James and Peirce, Dewey integrates “habit” deeply into his philosophy, using it to explain various dimensions of human experience (biological, ethical, political, and aesthetic) as manifested in complex and social behaviors—walking, talking, cooking, conversing. [ 7 ] Habits are complex, composed of acts which unfold in time. Acts may begin with instinct borne of need and muddle toward reintegration and satisfaction. To become a habit, an act-series changes gradually and cumulatively; one act leads to the next. “Habit” emerges when acts cumulatively link to structure experience. Habit, Dewey wrote, “is an acquired predisposition to ways or modes of response, not to particular acts” ( HNC , MW14: 32). Such “ways” draw on past experiences, including social and linguistic interaction. Habits shared by groups are “customs”.

Dewey challenged assumptions about the routine nature of habits. Habits may become routine, but are not strictly automatic or insulated from conscious reformulation. Indeed, they cannot be literally automatic because every situation is somehow new. Thus, the same exact acts never repeat. Unlike machine routines, organic habits remain plastic, changeable. Habitually eating sweets is subject to contingency (toothache) and modification (restraint); thus, conscious reflection is the first stage of habits’ revision.

He also challenged the notion that habits were dormant powers, waiting to be invoked. Instead, habits are “energetic and dominating ways of acting” determining what we do and are: “All habits are demands for certain kinds of activity; and they constitute the self” ( HNC , MW14: 22, 21). Habits are not individual possessions or inner forces; rather, they are transactions between organisms and environments, functions making adaptation or reconstruction possible.

Habits enter into the constitution of the situation; they are in and of it, not, so far as it is concerned, something outside of it. (“Brief Studies in Realism”, MW6: 120)

Because situations are cultural as well as bio-physical, habits are ineliminably social. So-called “individual” habits emerge within the social world of friends, family, home, work, media, etc. Change of habit, then, is not a project of invoking sheer willpower, but rather one of intelligent inquiry into relevant, frequently wider and social, conditions (psychological, sociological, economic, etc.).

Dewey redescribed “emotion” as he did “habit” — a basic form of involvement in “coordinated circuits” of activity. But while habits are controlled responses to problematic situations, emotion is not predominantly controlled or organized; emotion is an organism’s “perturbation from clash or failure of habit” ( HNC , MW14: 54). As with the other psychological accounts, Dewey reconstructs emotion as transactional with other experiences (also typically analyzed as discrete — “rational,” “physical,” etc.).

Dewey’s account draws upon Darwin and James. Darwin argued that internal emotional states cause organic expressions which, depending on their survival value, may be subject to natural selection. James sought to decrease the distance between emotion and accompanying bodily expression. In cases of emotion, a perception excites a pre- organized physiological mechanism; recognizing such changes just is the emotional experience: “we feel sorry because we cry, angry because we strike” (James 1890 [1981: 450]). Dewey’s “The Theory of Emotion” (1894b & 1895, EW4) pushed James’ point further, toward an integrated whole (feeling-and-expression). Being sad is not merely feeling sad or acting sad but is the purposive organism’s overall experience. In effect, Dewey is gently correcting James’ (1890) reiteration of mind-body dualism. To understand emotion, we must see that “the mode of behavior is the primary thing” (“The Theory of Emotion”, EW4: 174). Like habits, emotions are not private possessions but emerge from the dynamic organism-environment complex; emotions are “called out by objects, physical and personal” as an intentional “response to an objective situation” ( EN , LW1: 292). As I encounter a strange dog, I am perplexed about how to react; usual habits are inhibited and there is emotion. (“The Theory of Emotion”, EW4: 182) We may say emotions are intentional insofar as they are “ to or from or about something objective, whether in fact or in idea” and not merely reactions “in the head” ( AE , LW10: 72).

Philosophically, emotion is a central feature of Dewey’s critique of traditional epistemology and metaphysics. By pursuing simple or pure rational access (to truth, reality) such systems misrepresent and castigate emotion as distraction, confused thought, or bodily interference; naturally, emotion becomes something needing to be suppressed, controlled, or bracketed. For Dewey, emotion is courses through individuals (reasoning, acting) and social groups (creating cultural meanings). He connects the traditional balkanization of emotion to non-philosophical motives, such as the segregation of leisure from labor and men from women. On Dewey’s reading, traditional rationalistic approaches require not just logical but moral critique.

2.7 Sentiency, Mind, and Consciousness

Dewey’s accounts of sentiency, mind, and consciousness build upon those of impulse, perception, act, habit, and emotion. A cursory view completes this sketch of Dewey’s psychology.

As with other psychic phenomena, sentience emerges through organism-environment transactions. Creatures seek to satisfy needs and escape peril; when precarity disrupts stability a struggle to reestablish balance begins, and what follows is adjustment of self, environment, or both. Sometimes previously successful methods (pre-organized responses) fail, and we become ambivalent. Divided against ourselves about what to do next, it proves advantageous to inhibit practiced responses (look before leaping). It is this inhibitory pause of action that, Dewey wrote, “introduces mental confusion, but also, in need for redirection, opportunity for observation, recollection, anticipation” ( EN , LW1: 237). In other words, inhibition makes new ways of considering alternatives possible, imbuing crude, physical situations with new meaning. Thus, Dewey wrote, sentiency or feeling

is in general a name for the newly actualized quality acquired by events previously occurring upon a physical level, when these events come into more extensive and delicate relationships of interaction. ( EN , LW1: 204)

At this stage, the new relationships are not yet known ; they do, however, provide the conditions for knowing. Symbolization, language, liberates these now-noticed relationships using tools of abstraction, memory, and imagination ( EN , LW1: 199).

Dewey rejected traditional accounts of mind-as-substance (or container) and more contemporary reductions of mind to brain states ( EN , LW1: 224–225). Rather, mind is activity, a range of dynamic processes of interaction between organism and world. Language offers some clues to the diversity of ways we can think of mind: as memory (I am re mind ed of X); as attention (I keep her in mind , I mind my manners); as purpose (I have an aim in mind ); as care or solicitude (I mind the child); as heed (I mind the traffic stop). “Mind”, then, ranges over many activities: intellectual, affectional, volitional, or purposeful. It is

primarily a verb…[that] denotes every mode and variety of interest in, and concern for, things: practical, intellectual, and emotional. It never denotes anything self-contained, isolated from the world of persons and things, but is always used with respect to situations, events, objects, persons and groups. ( AE , LW10: 267–68)

As Wittgenstein ( entry on Wittgenstein, section on rule-following and private language ) pointed out 30 years later, no private language (see entry on private language ) is possible given this account of meaning. While meanings might be privately entertained, they are not privately invented; meanings are social and emerge from symbol systems arising through collective communication and action ( EN , LW1: 147).

Active, complex animals are sentient due to the variety of distinctive connections they have with their environment. But “mentality” (mindfulness) arises due to the eventual ability to recognize and use meaningful signs. With language, creatures can identify and differentiate feelings as feelings, objects as objects, etc.

Without language, the qualities of organic action that are feelings are pains, pleasures, odors, colors, noises, tones, only potentially and proleptically. With language they are discriminated and identified. They are then “objectified”; they are immediate traits of things. ( EN , LW1: 198)

The bull’s charge is stimulated by the red flag, but the automobile driver takes the red stoplight as a sign.

Dewey thus de-divinized mind while accentuating new aspects of mind’s significance. No longer our spark of divinity, as some ancients held, mind is also no mere ghost in a machine. Mind is vital , investigating problems and inventing tools, aims, and ideals. Mind bridges past and future, an “agency of novel reconstruction of a pre- existing order” ( EN , LW1: 168).

Like mind, consciousness is also activity—the brisk transitioning of felt, qualitative events. Profoundly influenced by James’s metaphor of consciousness as a constantly moving “stream of thought” ( FAE , LW5: 157), Dewey did not conclude that an account of consciousness could be adequately captured in words. Talk about consciousness is always elliptical—it is “vivid” or “conspicuous” or “dull”—always falling shy of the phenomenon. Because the experience of consciousness is ever-evanescent, we cannot fix it as with objects of our attention— for example, “powers”, “things”, or “causes”. Dewey, then, evokes but does not define consciousness. Consider these contrasts in Experience and Nature , ( EN , LW1: 230)

As the comparison makes obvious, psychological life is processual and active; accordingly, Dewey describes consciousness in terms suiting dynamic organisms. Consciousness is thinking-in-motion, ever-reconfiguring series of events that are felt as qualitative experience proceeds. If mind is a “stock” of meanings, consciousness is the realization-and-reconstruction of meanings, reconstructions which can reorganize and redirect activity ( EN , LW1: 233).

Dewey occasionally tried to convey his notion of consciousness performatively, inviting readers to reflect about consciousness while they were reading about it. Here, again, “focus” and “fringe” play a crucial role. ( EN , LW1: 231). As physical balance controls walking, mental meanings adjust and direct ongoing foci and interpretation.

3. Experience and Metaphysics

Dewey’s notion of “experience” evolved over the course of his career. Initially, it contributed to his idealism and psychology. After he developed instrumentalism in Chicago during the 1890’s, Dewey moved to Columbia, revising and expanding the concept in 1905 with his historically significant “The Postulate of Immediate Empiricism” ( PIE , MW3). “The Subject-matter of Metaphysical Inquiry” (1915, MW8) and the “Introduction” to Essays in Experimental Logic (1916, MW10) developed the concept, showing “experience” did more than rebut subjectivism in psychology, but was also central to his metaphysical accounts of existence and nature (Dykhuizen 1973: 175–76). This was concretized in Dewey’s 1923 Carus Lectures, revised and expanded as Experience and Nature (1925, revised edition, 1929; EN , LW1). Further extensions and elaborations followed, notably in Art as Experience (1934b, AE , LW10). [ 8 ]

Pivotal to his oeuvre, interested readers should track experience across this entry; here, the focus will be on Dewey’s philosophical method and metaphysics.

Why was experience so important that it permeated Dewey’s approach to philosophy? Three influences were paramount. First, Dewey inherited Darwin’s idea of nature as a complex congeries of changing, transactional processes without fixed ends; in this context, experience means the undergoing and doing of organisms-in-environments, “a matter of functions and habits, of active adjustments and readjustments, of coordinations and activities, rather than of states of consciousness” (“A Short Catechism Concerning Truth”, MW6: 5). Second, Dewey took from James a radically empirical approach to philosophy—the insistence that perspectival experience, (e.g., the personal , emotional , or temperamental ) was philosophically relevant, including to abstract and logical theories. Finally, Dewey accepted Hegel’s emphasis on experience beyond the subjective consciousness — manifest in social, historical, and cultural modes. The self is constituted through experiential transactions with the community, and this vitiates the Cartesian model of simple, atomic selves (and any methods based upon that presumption). Understood this way, philosophy starts where we start, personally — with complex, symbolic, and cultural forms.

These influences, plus Dewey’s own inquiries, convinced him “experience” was the linch-pin to a broader theory of human beings and the natural world. This renewed focus on experience also amounted to a metaphilosophy; it discarded the assumption that philosophy gave special insights into ultimate truth or reality. Philosophy was equipment for living.

As both sheer terminology and as Dewey deployed it, “experience” generated much confusion and debate. Dewey commented about this toward the end of his life. [ 9 ] Decades later, one of Dewey’s foremost philosophical celebrants, Richard Rorty, lambasted Dewey for both the term and (what Rorty perceived as) Dewey’s intentions. [ 10 ] (Rorty 1977, 1995, 2006) (Rorty 1977, 1995, 2006) Nevertheless, since the term lives on, both in Dewey’s work and in everyday discourse, it deserves continued analysis.

Understanding Dewey’s view of experience requires, first, some notion of what he rejected. It was typical for many philosophers to construe experience narrowly, as the private contents of consciousness. These might be perceptions (sensing), or reflections (calculating, associating, imagining) done by the subjective mind. Some, such as Plato and Descartes, denigrated experience as a flux which confused or diverted rational inquiry. Others, such as Hume and Locke, thought experience (as atomic sensations) provided the mind at least some resources for knowing, but with limits. All agreed that percepts and concepts were different and in tension; they agreed that sensation was perspectival and context-relative; they also agreed that this relativity problematized the assumed mission of philosophy—to know with certainty—and differed only about the degree of the problem.

Dewey disputed the empiricist conviction that sensations are categorically separable contents of consciousness. This belief produced a “whole epistemological industry” devoted to the general problem of “correspondence” and a host of specific puzzles (about the existence of an external world, other minds, free will, etc.) (“Propositions, Warranted Assertibility, and Truth”, LW14: 179). This “industry” isolates philosophy from empirically informed accounts of experience and from pressing, practical problems. Regarding mental privacy, Dewey argued that while we have episodes of what might be called mental interiority, it is a later development: “Personality, selfhood, subjectivity, are eventual functions that emerge with complexly organized interactions, organic and social” ( EN , LW1: 162; see also 178–79). Regarding sensorial atomicity, discussed previously in the section on psychology ,

Dewey explained sensation as embedded in a larger sensori-motor circuit, a transaction which should not be quarantined to any single phase—nor to consciousness.

Dewey levied similar criticisms against traditional accounts of reflective thought. He denied a substantial view of mind, especially one ontological apart from body, history, or culture. Reasoning is one function of mind, not the exercise of a separate “faculty”. There is no reason to purify reasoning of feeling, either; reasoning is always permeated with feelings and practical exigencies. It may be practical, at times to “bracket out” a feeling or exigency when they interfere with mental calculating, but it is nevertheless true that reasoning subsists in a wider and “qualitative world” (“Psychology and Work”, LW5: 243).

We have, already, an outline of Dewey’s view: experience is processual, transactional, socially mediated, and not categorically prefigured as “rational” or “emotional”. We add three additional, positive characterizations of experience: first, as experimental ; second, as primary (“had”) or secondary (“known”); and third, as methodological .

First, experience exhibits a fundamentally experimental character. Dewey’s saw, during decades in education, how children’s experiences alternate between acting and being acted upon. Such phases become “experimental” when agents (students) consciously relate what is tried with what eventuates as they come to understand which actions are significant for controlling future events. When experience is experimental, we name the outcome “learning”. [ 11 ]

Second, most of experience is not known or reflective; it is barely regulated or reflected upon. As such, it is “felt” or “had”. Dewey also calls such experience direct and primary. The other kind experience, the focus of philosophy, is characterized by “knowing” or mediation-by-reflection. Dewey labels these “indirect”, “secondary”, or “known”. Known experience abstracts from had (or direct) experience purposefully and selectively, isolating certain relations or connections. The Quest for Certainty provides a cogent description:

[E]xperienced situations come about in two ways and are of two distinct types. Some take place with only a minimum of regulation, with little foresight, preparation and intent. Others occur because, in part, of the prior occurrence of intelligent action. Both kinds are had ; they are undergone, enjoyed or suffered. The first are not known; they are not understood; they are dispensations of fortune or providence. The second have, as they are experienced, meanings that present the funded outcome of operations that substitute definite continuity for experienced discontinuity and for the fragmentary quality due to isolation. ( QC , LW4: 194) [ 12 ]

Dewey’s had/known distinction describes existence without presupposing a dualism between appearance/reality. Much can be unknown without therefore being illusory or merely apparent. Pace Plato, we are not trapped in a cave of illusions with reason as our only escape. We cope with a world that is often confusing or opaque; as we try to make meaning, we keep track of ideas especially helpful predicting and controlling circumstances. Some other experiences are simply enjoyed without making them less real .

Third, Dewey’s renewed and expanded focus on experience was methodological. This requires some unpacking. Dewey’s distinction between experience “had” and “known” was more than a phenomenological observation; it was directive about how philosophy should be done. (We can see this kind of move embedded in Peirce’s pragmatic maxim and James’s radical empiricism.) For Dewey, experience is not just “stuff” presented to (or witnessed by) consciousness; experience is activity, engagement with life. Philosophy, too, is a form of lived activity, which means that doing philosophy properly requires a different starting point. In life, even philosophers do not start with a theory. Theories undoubtedly enter in, but not first. “The vine of pendant theory”, Dewey wrote about the denotative method, “is attached at both ends to the pillars of observed subject-matter” ( EN , LW1: 11; see also 386). [ 13 ]

Following James and Peirce, Dewey is challenging the theoretical assumptions of previous philosophies—“substances”, “mind vs. body”, “pleasure as natural aim”, and so on. Dewey’s philosophical work did critique those concepts, but the point here is metaphilosophical—that we do not start with what is abstract, conceptual. Dewey’s concern with such theoretical starting points was that they isolate philosophy from a more thoroughgoing empiricism capable of engaging actual human problems.

“Experience as method”, then, is both a warning and a positive recommendation. It warns philosophers to recognize that while intellectual terms may seem “original, primitive and simple” they should be understood as the historically and normatively situated “products of discrimination and classification” ( EN , LW1: 386; see also 371–372, 375). “Knowing” does not stand beyond experience or nature, but is an activity with its own standpoint and qualitative character. Whatever theory is eventually devised, a genuinely experiential method will check it against ordinary experience ( EN , LW1: 26). [ 14 ]

The experiential or denotative method tells us that we must go behind the refinements and elaborations of reflective experience to the gross and compulsory things of our doings, enjoyments and sufferings—to the things that force us to labor, that satisfy needs, that surprise us with beauty, that compel obedience under penalty. ( EN , LW1: 375–76)

Such a method is critical because it forces inquirers to check previous interpretations and judgments against their live encounters in a new situation ( EN , LW1: 364). Philosophy has to engage with new subject matters (and theories), accept challenges beyond the traditional “problems of philosophy”, and embrace the idea that “the starting point is the actually problematic ” ( EN , LW1: 61).

Much that is central to Dewey’s metaphysics has been discussed—the transactional organism-environment setting, mind, consciousness, and experience. Accordingly, this section will examine how Dewey conceived of “metaphysics”, the main project in Experience and Nature , how he attempted to reconnect empirical metaphysics with an ancient idea (philosophy as wisdom), and some of the criticisms his conception received.

Debate over a definite meaning for the term “metaphysics”, was as alive in Dewey’s day as in ours. From the beginning, Dewey sought to critique and reconstruct metaphysical concepts (e.g., reality, self, consciousness, time, necessity, and individuality) and systems (e.g., Spinoza, Leibniz, Kant, and Hegel). Like his fellow pragmatists Peirce, James, and Mead, Dewey wished to transform not eradicate metaphysics. Dewey’s early metaphysical views were closest to idealism, but engagements with experimental science and instrumentalism convinced him to abandon the traditional goal of ultimate and complete accounts of reality.

His interest in metaphysics was revivified at Columbia by colleague F. J. E. Woodbridge, who thought metaphysics could be done in a “descriptive” rather than an extra-physical way (“Biography of John Dewey”, in Schilpp 1939: 36). While many of Dewey’s most important metaphysical works focused on experience (discussed above), special attention is due to “The Postulate of Immediate Empiricism” (1905, PIE , MW3), “The Subject-Matter of Metaphysical Inquiry” (1915, MW8), and his “Introduction” to Essays in Experimental Logic (1916c, MW10). [ 15 ] These were all vital precursors to his magnum opus, Experience and Nature . EN ’s final chapters, dealing with art and consummatory experience, were further developed in Art as Experience (1934b, LW10), a text containing additional and significant metaphysical discussions.

While labels tend to obscure what was innovative in his work, it is safe to say Dewey composed a realist, naturalistic, non-reductive, emergentist, process metaphysics. [ 16 ] He described nature’s most general features (“generic traits”) while trying to do empirical justice to the world as encountered. His account also aimed to remain fallible and useful for future researchers seeking to improve life with philosophy. In the end, Dewey described his efforts as a “metaphysics” and as a “system”: “the hanging together of various problems and various hypotheses in a perspective” (“Nature in Experience”, LW14: 141–142). He did not propose a metaphysics from a god’s eye point of view, but one informed and motivated by “a definite point of view” and linked to the contemporary, human world (“Half-hearted Naturalism”, LW3: 75–76 ).

Experience and Nature provides extended criticism of past metaphysical approaches, especially their quest for certainty and assumption of an Appearance/Reality framework, and a positive, general theory regarding how human existence is situated in nature. It is empirical, descriptive, and hypothetical, eschewing claims of special access beyond “experience in unsophisticated forms”. Such experience, Dewey argued, gives us “evidence of a different world and points to a different metaphysics” ( EN , LW1: 47). EN looks to existing characteristics of human culture, anthropologically, to see what they reveal, more generally, about nature. One significant product is Dewey’s isolation, analysis, and description of “generic traits of existence” and their relations to one another.

While this entry lacks space for even a bare summary, it is noteworthy that EN begins with an extensive discussion of method and experience as a new starting point for philosophy. An extensive presentation of the generic traits follows, which later informs discussions about science, technology, body, mind, language, art, and value. While the traits are not presented systematically (à la other metaphysicians such as Spinoza or Whitehead) there is a progression moving from the more basic to the more complex. [ 17 ]

One might ask, How can metaphysics contribute to the world beyond academic philosophy? Dewey aimed to return philosophy to an older, ancient mission—the pursuit of wisdom. And while Dewey describes philosophy as inherently critical, a “criticism of criticisms”, it still raises questions about the objectives of an empirical, hypothetical, naturalistic metaphysics? ( EN , LW1: 298) Dewey raises the issue, himself, prophylactically:

As a statement of the generic traits manifested by existences of all kinds without regard to their differentiation into physical and mental, [metaphysics] seems to have nothing to do with criticism and choice, with an effective love of wisdom. ( EN , LW1: 308)

His answer comes by way of an account of existence’s generic traits, which purportedly provides “a ground-map of the province of criticism, establishing base lines to be employed in more intricate triangulations” ( EN , LW1: 308). [ 18 ] A new metaphysics, like a new map, offers new possibilities for framing and explaining the world. This could discredit entrenched truisms—e.g., men are rational, women are emotional, humans are intelligent, animals are dumb, etc.— or facilitate new connections and new meanings. As Dewey saw it, the long tradition of philosophy had rendered too basic conceptual tools (kinds, categories, dualisms, aims, and values) unassailable; his reconsideration offered a new basis for metaphysics, one which would be relevant and revisable.

"Map-making" suggested a new way to do metaphysics and a new role for philosophers. Philosophers, on this model, become “liaison officers”, intermediators able to facilitate communication between those speaking at cross purposes or in different jargons ( EN , LW1: 306). Drawing from contemporary circumstances and purposes, the maps drawn could not promise certainty or permanency but would need to be redrawn according to changing needs and purposes. Their test, as with the rest of Dewey’s pragmatist philosophy, would lay in their capacity to sharpen criticisms and secure values.

Dewey received and responded to many criticisms of his metaphysical views. Critics often overlooked that his aim was to undercut prevailing metaphysical genres; often, his view was rashly consigned to some other extant camp. (He was characterized, variously, as a realist, idealist, relativist, subjectivist, etc. See Hildebrand 2003.) One recurrent criticism was that his statement in PIE (that “things are what they are experienced as” ) could not yield a metaphysics because it merely reported subjective and immediate experience; such reports, the criticism went, prevented a more mediated and (properly) objective account. Twenty years later, EN received similar reactions by critics who attacked Dewey’s non-binary approach to experience and nature. [ 19 ]

Subsequent criticisms focused upon Dewey’s supposed neglect of a tension between “qualities” vs. “relations”. Qualities, the argument ran, are immediate, whereas relations are mediate; how could Dewey claim they coexist in the same item of experience? This seemed to embody a contradiction. [ 20 ] Richard Bernstein (1961) seized on this issue, and claimed that Dewey harbored two irreconcilable strains, a “metaphysical strain” and a “phenomenological strain”, but failed to sufficiently account for them with his “principle of continuity”. One response to Bernstein argued that his critique unwittingly reenacted the very spectatorial standpoint Dewey’s experiential starting point seeking to overcome. [ 21 ]

In recent years, some debate whether Dewey should have engaged in metaphysics at all. Richard Rorty and Charlene Haddock Seigfried argued that Dewey’s critique of traditional metaphysics was as far as he should have gone; his further efforts diverted him from more important ethical work (Seigfried 2001a, 2004) or plunged him into foundationalist projects previously disavowed (“Dewey’s Metaphysics” in Rorty 1977). Defenders argue that Dewey’s genuinely new approach to metaphysics avoids old problems while contributing something salutary to culture at large (Myers 2020, Garrison 2005, Boisvert 1998a, Alexander 2020).

4. Inquiry and Knowledge

The interactional, organic model Dewey developed in his psychology informed his theories of learning and knowledge. Within this framework, a range of traditional epistemological proposals and puzzles (premised on metaphysical divisions such as appearance/reality, mind/world) lost credibility. “So far as the question of the relation of the self to known objects is concerned”, Dewey wrote, “knowing is but one special case of the agent-patient, of the behaver-enjoyer-sufferer situation” (“Brief Studies in Realism”, MW6: 120). As with psychology, Dewey’s wholesale repudiation of the traditional metaphysical framework required extensive reconstruction in every other area; “instrumentalism” was one popular name for Dewey’s reconstruction of epistemology (or “theory of inquiry”, as Dewey preferred). [ 22 ]

As with his earlier functional approach to psychology, Dewey’s instrumentalism leveraged Darwin to dissolve entrenched divisions between, for example, realism/idealism, science/religion, and empiricism/rationalism. Change and transformation become natural features of the actual world, and knowledge and logic are recast as ways to adapt, survive, and thrive. The better way to understand reasoning is by looking to the dynamic and biological world which harbors it, rather than the traditional paradigms of static precision, physics or mathematics. [ 23 ]

Early statements of instrumentalism (and definitive breaks by Dewey with Hegelian logic) may be seen in “Some Stages of Logical Thought” (Dewey 1900 [1916], MW1); that essay follows Peirce ( entry on Peirce section on pragmatism, pragmaticism, and the scientific method ], [ 24 ] especially the well known 1877–78 articles championing the larger framework of scientific thinking, namely the “doubt-inquiry process” (MW1: 173; see also Peirce 1877, 1878). This account is developed in Studies in Logical Theory (Dewey 1903b, MW2), by Dewey and his collaborators at Chicago. In the work, Dewey acknowledges a “preeminent obligation” to James (Perry 1935: 308–309). [ 25 ]

Studies criticizes transcendentalist logic extensively, concluding that logic should not assume either thought or reality’s existence in general but should rest content with the function or use of ideas in experience :

The test of validity of [an] idea is its functional or instrumental use in effecting the transition from a relatively conflicting experience to a relatively integrated one. ( Studies , MW2: 359)

Thus, instrumentalism abandons all psycho-physical dualisms and all correspondentist theories of knowing. Dewey wrote,

In the logical process the datum is not just external existence, and the idea mere psychical existence. Both are modes of existence—one of given existence, the other of possible , of inferred existence….In other words, datum and ideatum are divisions of labor, cooperative instrumentalities, for economical dealing with the problem of the maintenance of the integrity of experience. ( Studies , MW2: 339–340)

While instrumentalism was of a piece with Dewey’s other views, it was also responding to dialectic within philosophy’s epistemological positions, particularly between British empiricism, rationalism (see entry on rationalism vs. empiricism ), and the Kantian synthesis.

Classical empiricists insisted that sensory experience provided the origins of knowledge. They were motivated, in part, by the concern that rationalistic accounts effort to link knowledge with thought alone (away from particular sense stimuli), were too unchecked. Without the constraints of sense experience, philosophy was doomed to keep producing wildly divergent systems. Classical empiricists, like Dewey, shared a genuine interest in scientific progress; such progress required, first, escape from unfettered speculation. The account developed by figures such as Locke, Berkeley, and Hume claimed that (in Locke’s version) the world writes on a receptive blank slate, the mind, in the language of ideas. Using faculties of memory, association, and imagination, knowledge is generated; extension of knowledge must, on this account, be traceable to origination in sense experience.

Rationalists, in contrast, argued that knowledge was both abstract and deductively certain. Sensory experiences are fluid, individualized, and permeated by the relativity borne of innumerable external conditions. How could a philosophical account of genuine knowledge—necessarily certain, self-evident, and unchanging—be derived using sensorial flux? No, knowledge must be derived from inner and certain concepts. Knowledge, then, is produced by an immaterial entity, mind, with an innate power to reason, independent of the contingencies of practical ends and physical bodies.

Kant responded to the empiricist-rationalist tension by reigning in their ambitions; philosophy must stop attempting to transcend the limits of thought and experience. Philosophy’s more modest and proper aspiration is to discover what can be known in the phenomenal world. Kant, then, refused an originary role to either percepts or concepts, arguing that sense and reason are co-constitutive of knowledge. More important, Kant argued for mind as systematizing and constructive.

Dewey’s response to this three-way epistemological conflict was foreshadowed in the earlier discussion of the “Reflex Arc” paper and the idea of sensori-motor circuits. For Dewey, any proposal premised on a disconnected mind and body—or upon one assuming that stimuli (causes, impressions, or what have you) were atomic and in need of synthesis—was a non-starter. [ 26 ]

Accepting some of Kant’s criticisms of rationalism and empiricism, Dewey rejected Kant’s propagation of several significant but unjustified assumptions: that knowledge must be certain; that nature and intellect were categorically distinct; and that it was justified to posit a noumenal realm (things-in-themselves). Dewey also questioned Kant’s supposition that the sensations ingredient to knowledge are initially inchoate; such a claim was, Dewey believed, driven by Kant’s architectonic. Methodologically, perhaps most significantly, Dewey followed James in criticizing Kant’s standpoint as too spectatorial. From a pragmatic, Jamesean, “radical empiricist” standpoint, one may accept a wide variety of phenomenon (clear, vague, felt, remembered, anticipated, etc.) as real even though they are not known .

Thus, for Dewey, Kant falls short of the philosophical perspective needed to synthesize perception and conception, nature and reason, practice and theory. While Kant’s model of an active and structuring mind was a clear advance over passive ones, it retained the retrograde picture of knowledge as reality’s faithful mirror. Kant failed to see knowledge as a dynamic instrument for managing (predicting, controlling, guiding) future experience. This pragmatic conception of knowledge judges it as one would an eye or hand, gauging how it affects the organism’s ability to cope:

What measures [knowledge’s] value, its correctness and truth, is the degree of its availability for conducting to a successful issue the activities of living beings. (“The Bearings of Pragmatism Upon Education”, in MW4: 180)

Thus, Dewey replaced Kant’s mind-centered system with one centered upon experience-nature transactions—“a reversal”, Dewey wrote, “comparable to a Copernican revolution” ( QC , LW4: 232).

In the context of instrumentalism, what is “logic” and “epistemology”? Dewey does not discard these but insists on a more empirical approach. How do reasoning and learning actually happen? [ 27 ] Dewey comprehensively addresses logic in his 1938 Logic: The Theory of Inquiry ( LTI , LW12), which calls logic the “inquiry into inquiry”. LTI attempts to systematically collect, organize, and explicate the actual conditions of different kinds of inquiry; the aim, previewed in his 1917 “The Need for a Recovery of Philosophy”, is pragmatic and ameliorative: to provide an “important aid in proper guidance of further attempts at knowing” (MW10: 23).

Throughout his career, Dewey described the processes and patterns evinced in active problem solving. Here, we consider three: inquiry, knowledge, and truth. There is, Dewey argued, a “pattern of inquiry” which prevails in problem solving. “Analysis of Reflective Thinking” (1933, LW8) and LTI (LW12) describes five phases. Disavowing the usual divide between emotion and reason, inquiry begins (1) with a feeling of something amiss, a unique and particular doubtfulness; this feeling endures as a pervasive quality imbued in inquiry and serves as a kind of “guide” to subsequent phases. Next, because what is initially present is indeterminate, (2) a problem must be specifically formulated; note that problems do not preexist inquiry, as typically assumed. [ 28 ] Next, (3) a hypothesis is constructed, one which imaginatively utilizes both theoretical ideas and perceptual facts in order to forecast possible consequences of eventual operations. Next, (4) one reasons through the meanings involved in the hypothesis, estimating implications or possible contradictions; frequently, discoveries here direct one return to an earlier phase (to reformulate the hypothesis or redescribe the problem). [ 29 ] Finally, inquiry closes, (5) acting to evaluate and test the hypothesis; here, inquiry discovers whether a proposed solution resolves the problem, whether (in LTI ’s terminology) inquiry has converted an “indeterminate situation” into a “determinate one”.

The inquiry pattern Dewey sketched is schematic; actual cases of reasoning often lack such discreteness or linearity. Thus, the pattern is not a summary of how people always think but rather how exemplary cases of inquirential thinking unfold (e.g., in the empirical sciences).

Knowledge, on Dewey’s transactional model of inquiry, departs from tradition and brought to earth. “Knowledge, as an abstract term”, Dewey wrote,

is a name for the product of competent inquiries. Apart from this relation, its meaning is so empty that any content or filling may be arbitrarily poured in. ( LTI , LW12: 16)

To understand a product, one must understand the process; this is Dewey’s approach. By denying that knowledge is an isolated product, he effectively denies a metaphysics that makes mind- the-substance separate from everything else. He does not depreciate knowing as an activity , and strongly maintains that “intelligence” is crucial to mediating individual and societal conflicts. [ 30 ]

Truth is also radically reevaluated. Truth long connoted an ideal— an epistemic fixity (a correspondence, a coherence) capable of satisfying the need for further inquiry. Since this is not the actual situation human beings (or philosophy) inhabits, the ideal should be set aside. Still, Dewey was ever the (re)constructivist; in “Experience, Knowledge, and Value” (1939c) he provided an account. Truth no longer points toward something transcendental but toward the process of inquiry (“Experience, Knowledge, and Value”, LW14: 56–57). A proposition is “true” insofar as it serves as a reliable resource:

In scientific inquiry, the criterion of what is taken to be settled, or to be knowledge, is being so settled that it is available as a resource in further inquiry; not being settled in such a way as not to be subject to revision in further inquiry. ( LTI , LW12: 16)

Truth is not beyond experience, but is an experienced relation, particularly one socially shared. In How We Think , Dewey wrote,

Truth, in final analysis, is the statement of things “as they are,” not as they are in the inane and desolate void of isolation from human concern, but as they are in a shared and progressive experience….Truth, truthfulness, transparent and brave publicity of intercourse, are the source and the reward of friendship. Truth is having things in common. ( HWT , MW6: 67; see also “The Experimental Theory of Knowledge”, 1910b, MW3: 118)

In Dewey’s instrumentalism, then, knowledge and truth are adjectival not nominative, describing a process which, as Peirce tells us, can persist as long as we do. “There is no belief so settled as not to be exposed to further inquiry” (LTI, LW12: 16). Words like “knowledge” and “truth” are honored because of their historic service as tools for past inquiries and their aid in securing values.

5. Philosophy of Education

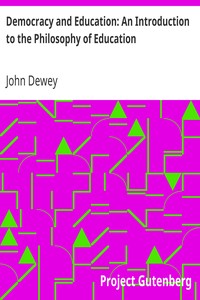

Around the world, Dewey remains as well known for his educational theories (see entry on philosophy of education, section Rousseau, Dewey, and the progressive movement ) as for his philosophical ones. A closer look shows how often these theories align. Recognizing this, Dewey reflected that his 1916 magnum opus in education, Democracy and Education ( DE , MW9) “was for many years that [work] in which my philosophy, such as it is, was most fully expounded” ( FAE , LW5: 156). DE argued that philosophy itself could be understood as “the general theory of education”, avoiding further hyper-specialization and investing more earnestly in everyday problems.

This was a call to see philosophy from an educational standpoint:

Education offers a vantage ground from which to penetrate to the human, as distinct from the technical, significance of philosophic discussions….The educational point of view enables one to envisage the philosophic problems where they arise and thrive, where they are at home, and where acceptance or rejection makes a difference in practice. If we are willing to conceive education as the process of forming fundamental dispositions, intellectual and emotional, toward nature and fellow-men, philosophy may even be defined as the general theory of education . ( DE , MW9: 338)

Dewey was active in education his entire life. Besides high school and college teaching, he devised curricula, established, reviewed and administered schools and departments of education, participated in collective organizing, consulted and lectured internationally, and wrote extensively on many facets of education. He established the University of Chicago’s Laboratory School as an experimental site for theories in instrumental logic and psychological functionalism. This school also became a site for democratic expression by the local community.

Dewey’s “Reflex Arc” paper applied functionalism to education. “Reflex” argued that human experience is not a disjointed sequence of fits and starts, but a developing circuit of activities. Framed this way, learning is a cumulative, progressive process where inquirers move from dissatisfying doubt toward satisfying resolutions of problems. “Reflex” also shows that the subject of a stimulus (e.g., the pupil) is not a passive recipient but an agent actively selecting stimuli within a larger field of activities.

Cognizance of these facts, Dewey argued, compelled educators to discard pedagogies based on the mind as “blank slate”. In The School and Society Dewey wrote, “the question of education is the question of taking hold of [children’s] activities, of giving them direction” (MW1: 25). How We Think (1910c, MW6) primarily aimed to help teachers apply instrumentalism. Overall, education’s intellectual goals would advance by acquainting children using the general intellectual habits of scientific inquiry.

The native and unspoiled attitude of childhood, marked by ardent curiosity, fertile imagination, and love of experimental inquiry, is near, very near, to the attitude of the scientific mind. ( HWT , MW6: 179)

These proposals entailed the revision of the teacher’s role; while teachers still had to know their subject matter, they also needed to understand students’ cultural and personal backgrounds. If learning was to incorporate actual problems, more careful integration of content with particular learners was needed. Motivational tactics also had to change. Rather than rewards or punishments, Deweyan teachers were to reimagine the whole learning environment, merging the school’s existing goals with pupils’ present interests. One strategy was to identify specific problems that could bridge curriculum and student and then formulate learning situations to exercise them. [ 31 ] This problem-centered approach was demanding, requiring teachers to train in subject matters, child psychology, and pedagogies for weaving these together. [ 32 ]

Dewey’s educational philosophy emerged amidst a fierce 1890’s debate between educational “romantics” and “traditionalists”. Romantics (also called “New” or “Progressive” education by Dewey), urged a “child- centered” approach; the child’s natural impulses provided education’s proper starting point. Education should not fetter creativity and growth, even if content must sometimes be attenuated. Traditionalists (called “Old” education by Dewey) pressed for “curriculum-centered” approaches. Children were empty cabinets curriculum fills with civilization’s contents; the main job of instruction was to ensure receptivity with discipline.

Dewey developed an interactional model to move beyond that debate, refusing to privilege either child or society. (See “My Pedagogic Creed”, 1897b, EW5; The School and Society , 1899, MW1; Democracy and Education , 1916b, MW9; Experience and Education , 1938b, LW13, etc.) While Romantics correctly identified the child (replete with instincts, powers, habits, and histories) as an indispensable starting point for pedagogy, Dewey denied that the child was the only starting point. Larger social groups (family, community, nation) have a legitimate stake in passing along extant interests, needs, and values as part of an educational synthesis.

Still, of these two approaches, Dewey more adamantly rejected traditionalists’ (overly) high premium on discipline and memorization. While recognizing the legitimacy of conveying content (facts, values), it is paramount that schools eschew indoctrination. Educating meant incorporating , giving wide latitude for unique individuals who, after all, would inherit and have dominion over the changing society. This is why who the child was mattered so much. Following colleague and lifelong friend G.H. Mead’s ideas about the social self, Dewey argued that schools had to become micro-communities to reflect children’s growing interests and needs. “The school cannot be a preparation for social life excepting as it reproduces, within itself, the typical conditions of social life” (“Ethical Principles Underlying Education”, 1897a, EW5: 61–62). [ 33 ]

Connecting child, school, and society aimed not only to improve pedagogy, but democracy as well. Because character, rights, and duties are informed by and contribute to the social realm, schools were critical sites to learn and experiment with democracy. Democratic life includes not only civics and economics, but epistemic and communicative habits as well: problem solving, compassionate imagination, creative expression, and civic self-governance. The range of roles a child might inhabit is vast; this creates a societal obligation to make education its highest political and economic priority. During WWII, Dewey wrote,

There will be almost a revolution in school education when study and learning are treated not as acquisition of what others know but as development of capital to be invested in eager alertness in observing and judging the conditions under which one lives. Yet until this happens, we shall be ill-prepared to deal with a world whose outstanding trait is change. (“Between Two Worlds”, 1944, LW17: 463)

Democracy is much more comprehensive than a form of government, it is “not an alternative to other principles of associated life [but] the idea of community life itself” ( PP , LW2: 328). Individuals exist in communities; as their lives change, needs and conflicts emerge that require intelligent management; we must make sense out of new experiences. Education empowers that by teaching the attitudes and habits (imaginative, empirical) that made the experimental sciences so successful. Dewey called these attitudes and habits “intelligence”. [ 34 ]

Informing these areas—science, education, and democratic life—is Dewey’s naturalism, which redirects hope away from what is immutable or ultimate (God, Nature, Reason, Ends) toward the human capacity to learn from experience. In “Creative Democracy—The Task Before Us” (1939b) Dewey wrote,

Democracy is the faith that the process of experience is more important than any special result attained, so that special results achieved are of ultimate value only as they are used to enrich and order the ongoing process. Since the process of experience is capable of being educative, faith in democracy is all one with faith in experience and education. All ends and values that are cut off from the ongoing process become arrests, fixations. They strive to fixate what has been gained instead of using it to open the road and point the way to new and better experiences. (“Creative Democracy”, LW14: 229)

Democracy’s success or failure rests on education. Education is most determinative of whether citizens develop the habits needed to investigate problematic beliefs and situations while communicating openly. While every culture aims to convey values and beliefs to the coming generation, the most important thing is to distinguish between education which inculcates collaborative and creative hypothesizing from education which foments obeisance to parochialism and dogma. This same caution applies to philosophy itself.

Dewey wrote and spoke extensively on ethics throughout his career; some writings were explicitly about ethics, but ethical analyses appear in works with other foci. [ 35 ] As elsewhere, Dewey critiques then reconstructs traditional views; he argued it is typical for traditional systems (e.g., teleological, deontological, or virtue-based) to seek comprehensive and monocausal accounts of, for example, ultimate aims, duties, or values. Such ideal theorizing is obligated to explain morality’s requirements for all individuals, actions, or characters.