Motivation and What Really Drives Human Behavior

Our motivation is our most valuable commodity. Multiplied by action, its value fluctuates with how we invest our attention.

Why is it that we are all born with limitless potential, yet few people fulfill those possibilities?

Abraham Maslow

And what actually drives humans?

Some of our motives to act are biological, while others have personal and social origins. We are motivated to seek food, water, and sex, but our behavior is also influenced by social approval, acceptance, the need to achieve, and the motivation to take or to avoid risks, to name a few (Morsella, Bargh, & Gollwitzer, 2009).

This article introduces some of the core concepts in the science of motivation.

But before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques to create lasting behavior change.

This Article Contains

Types of motivation, motivation and emotion, motivation and personality, motivation for change, happiness and human motivation, a take-home message, frequently asked questions.

Motivation can be experienced as internal. Biological variables originate in a person’s brain and nervous system and psychological variables that represent properties of a person’s mind – psychological needs.

External sources of motivation are often understood in terms of environmental variables, like incentives or goals. Our internal sources of motivation interact with external sources to direct behavior (Deckers, 2014).

It is never too late to be what you might have been.

George Eliot

Our evolutionary history also explains aspects of motivation and behavior, and our individual personal histories shape our motives and determine the utility of goals and incentives.

Drive Motivation

When the sympathetic nervous system produces epinephrine and norepinephrine, it creates energy for action. This may be why motivation is often conceptualized in terms of drives . Our bodies aim to return to equilibrium and strive toward a desired end-state, reducing or eliminating the drive (Reeve, 2018).

Needs are internal motives that energize, direct and sustain behavior. They generate strivings necessary for the maintenance of life, growth and wellbeing.

A hungry stomach will not allow its owner to forget it, whatever his cares and sorrows.

Homer, 800 B.C.

Physiological needs – hunger, thirst, sex, etc. – are the biological beginnings that eventually manifest themselves as psychological drives. These biological events become psychological motives. It is important to distinguish the physiological need from the psychological drive it creates because only the later has motivational properties.

The drive theory of motivation tells us that physiological needs originate in our bodies. As our physiological system attempts to maintain health, it creates psychological drive and motivates us to bring the system from deficiency toward homeostasis (Reeve, 2018).

If you want to know more about this topic, see our articles on Motivation Science and Theory of Motivation .

Goal Motivation

When talking about motivation, the topic of goals inevitably comes up. As a cognitive mental event, a goal is a “spring to action” that functions like a moving force that energizes and directs our behavior in purposeful ways and motivates people to behave differently (Ames & Ames, 1984).

Goals, like mindset, beliefs, expectations, and self-concept, are sources of internal motives. These cognitive sources of motivation unite and spring us into action.

Goals are generated by what is NOT, or in other words, a discrepancy between where we are and where we want to be. The saying “ If you don’t know where you’re going, any road will get you there ” describes the difference in motivated behavior between those who have goals and those who do not (Locke, 1996; Locke & Latham, 1990, 2002).

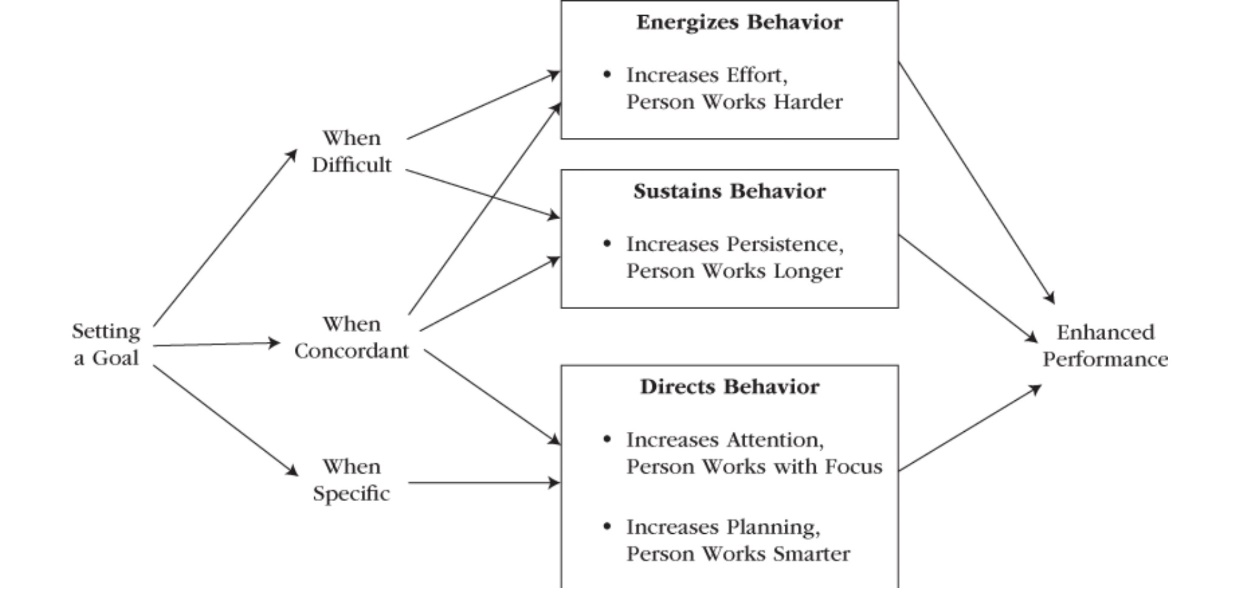

But it isn’t necessarily enlightening to simply formulate goals. As a motivational construct, goal setting translates into performance only when the goals are challenging, specific, and congruent with the self.

We exert more effort toward challenging goals (Locke & Latham, 1984, 1990, 2002), focus our attention to the extent of their specificity (Locke, Chah, Harrison, & Lustgarten, 1989), and draw energy from how those goals reflect our values (Sheldon & Elliot, 1999).

To learn more about making goals challenging, specific, and personal, check out our articles on The Science & Psychology of Goal Setting 101 and Goal-Setting: Templates & Worksheets for Achieving Goals .

Download 3 Free Goals Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques for lasting behavior change.

Download 3 Free Goals Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

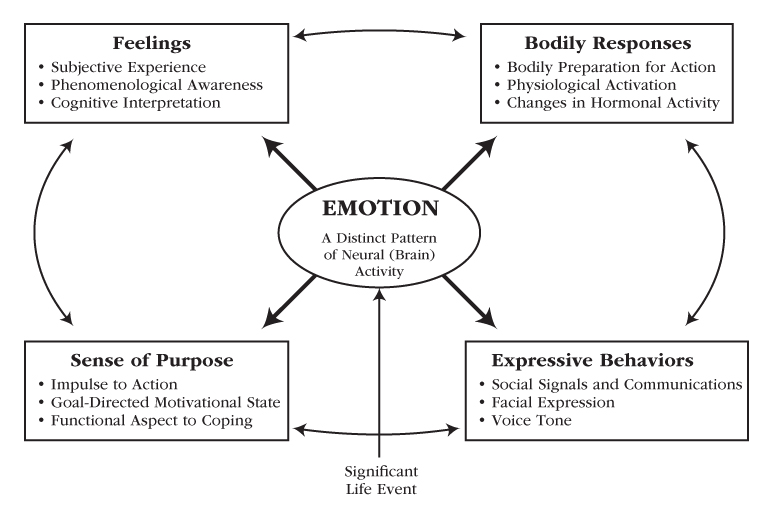

The concept of motivation is closely related to emotion. Both of these words are derived from the same underlying Latin root movere which means “to move.”

Emotions are considered motivational states because they generate bursts of energy that get our attention and cause our reactions to significant events in our lives (Izard, 1993).

Emotions generate an impulse to cope with the circumstances at hand (Keltner & Gross, 1999).

Together with emotion, motivation is part of a core psychological phenomenon referred to as affect.

We feel these experiences, physiologically and emotionally, and they motivate and guide our behavior and decision making. Most importantly, they have a significant impact on our mental and physical health. See our article on the Importance and Benefits of Motivation .

Are we predisposed to be motivated in different ways?

Personality theory and research show that we are, in fact, motivated in different ways based on our personality traits. A high level of a particular trait will often make us act as the trait implies: We will be more open to experience, conscientious, extraverted, agreeable, and neurotic. We will be motivated by different incentives, goals, and activities but also choose to be in different situations.

The task of psychology is to determine what those situations and behaviors are.

The trait–environment correlation studies show that if we exhibit characteristics at one end of a personality dimension we will seek out, create, or modify situations differently than individuals at the other end of the spectrum would (Deckers, 2014).

In addition to each of the big five personality traits, our tendency to seek sensation plays a significant role in how willing we are to take risks to experience varied, novel, complex, and intense sensations and experiences (Deckers, 2014).

The cybernetic big five theory linked personality traits with the type of goals we choose, and showed that specific goals would motivate appropriate personality state behaviors that are effective for achieving that goal (Deckers, 2014). For example, although people with extraverted and introverted personality traits react similarly to stimuli designed to put them in a pleasant hedonic mood, those high in extraversion have greater sensitivity to rewards.

They react with greater energetic arousal in response to the pursuit of rewards and are more likely than introverts to seek social stimulation in a variety of situations (Deckers, 2014).

The channeling hypothesis examines how specific personality traits determine how we express motivation and how we may respond to our personal motivation drives. It proposes that (Deckers, 2014):

- Extraverts tend to enter high-impact careers to satisfy their power motive and are more likely than introverts to do volunteer work to fulfill their affiliation motive.

- Those who are high in neuroticism are easier to put in a bad mood, less satisfied with their relationships and careers, and more likely to choose to drink in solitude following negative social exchanges.

- Individuals high in conscientiousness earn higher grades and are more likely to engage in health-enhancing behaviors.

- Highly agreeable people were found more likely to help friends and siblings in distress.

The selection hypothesis suggests that frequently, a composite of trait levels will be associated with a particular behavior . Many of these studies produced some very interesting results, which showed that (Deckers, 2014):

- Students low in extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness spend more time using the internet.

- Individuals high in openness to experience sought out contact with individuals from minority groups more and reported less prejudice than did individuals high in agreeableness.

- Happiness was associated with high levels of extraversion and agreeableness and low levels of neuroticism.

There are other personality factors that may affect motivation and what drives us toward our goals (Deckers, 2014):

- Those who are high in conscientiousness experience fewer stressors because of planning.

- Individuals high in agreeableness experience fewer interpersonal stressors because they are more cooperative.

- Those high in neuroticism experience more interpersonal stressors.

- Individuals high in conscientiousness, extraversion, and openness to experience cope through direct engagement with stressors.

- Those high in neuroticism cope through disengagement, such as escaping from a stressor or not thinking about it.

- Weight gain over people’s lifetimes is more significant when they are high in their neuroticism and extraversion, and low in their conscientiousness.

- Aspects of low agreeableness also contribute to weight gain.

- High-sensation seekers respond positively to risky events, drugs, and unusual experiences and are more likely to seek out and engage in risky sports, prefer unusual stimuli and situations, and experiment with things out of the ordinary.

- Low-sensation seekers respond negatively to risky events.

- Different components of sensation seeking are associated with a preference for nonsense humor or sexual humor.

Finally, personality traits of conscientiousness, openness, and extraversion have been positively associated with intrinsic motivation. Conscientiousness, extraversion, and neuroticism on the other hand have been positively related to extrinsic achievement motivation (Deckers, 2014).

Although agreeableness was found to be negatively associated with extrinsic achievement motivation, conscientiousness was anomalous, in that it was positively related to both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. These results suggest that both forms of motivation may be more complicated than expected initially (Hart et al., 2007).

See our article on the Importance and Benefits of Motivation to learn more about what constitutes self-motivation and full self-determination.

The topic of motivation is frequently discussed in the context of change.

Many of us join a gym or a training program; others enter therapy or coaching because we desire change. But change is rarely a simple or a linear process. Part of the reason has to do with how difficult it is to find the motivation to engage in activities that are not intrinsically motivating.

When an activity is autotelic, or rewarding and interesting in its own right, we do it for the sheer enjoyment of it and motivation is hardly necessary (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990).

Some changes look negative on the surface but you will soon realize that space is being created in your life for something new to emerge.

Eckhart Tolle

More often than not, however, what we want to change requires self-control to abstain from behaviors that don’t serve us but are enjoyable. Not to mention that commitment is required to pursue these often challenging and unrewarding activities that move us in the direction of a valued outcome.

Deci and Ryan (1995), who studied autonomous self-regulation, suggested that we need to move away from extrinsically motivated action, (e.g., when we have to do something because we fear consequences), and toward introjected and even fully self-determined regulation, where we value the new behavior and align it with other aspects of our life.

See our blog post entitled What is Motivation to learn more about self-motivation.

“Stage-based” approaches to behavioral changes have proven to be particularly effective in increasing motivation toward the pursuit of difficult and non-intrinsically motivating goals as they allow for realistic expectations of progress (Zimmerman, Olsen, & Bosworth, 2000).

The Stages of Change model of Prochaska, et al. (DiClemente, & Prochaska, 1998), also known as the Trans-theoretical Model of Change (TMC), is one such approach commonly used in clinical settings. In this model, change is regarded as gradual, sequential, and controllable. Its real-world applications are seen in motivational interviewing techniques, a client-centered method of facilitating change.

Here motivation is increased together with readiness for change which is determined by our:

- Willingness to change.

- Confidence in making the desire changed.

- Actions taken to make the change.

See our article on Motivational Interviewing for an in-depth analysis of this model of change and its many applications.

The answer to that question depends both on how we define happiness and whom we ask.

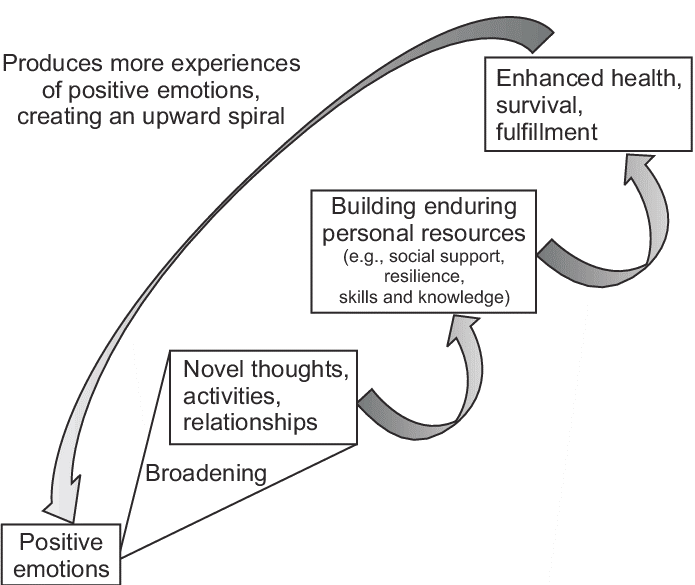

Thanks to the rapidly growing research in positive psychology, the science behind what makes life worth living, we know a lot about what makes us happy and what leads to psychological wellbeing. There is also plenty of evidence that positive subjective experiences contribute to increased motivation.

From Barbara Fredrickson’s (2004) research on how positive emotions broaden our perception and increase positive affect and wellbeing to the research of Teresa Amabile and Steven Kramer (2011) that shows how happy employees are more productive, we can see how cultivating optimism and positive emotions can serve an adaptive role and be a distinct motivational factor.

Those who feel good or show positive affect are:

- more creative (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005),

- help others more (Feingold, 1983),

- persistent in the face of failure (Erez & Isen, 2002; Kavanagh, 1987),

- make decisions efficiently (Schwartz et al., 2002), and

- show high intrinsic motivation (Graef et al., 1983).

Studies show that short-term positive affect helps us be successful in many areas in our lives, including marriage, friendship, income, work, and health (Lyubomirsky, King, & Diener, 2005).

Model of the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions Reprinted with permission of Guilford Press, Fredrickson, and Cohn (2008, Figure 48.1) [17]. Figure 2. Conceptual framework of the study.

The good life consists in deriving happiness by using your signature strengths every day in the main realms of living. The meaningful life adds one more component: using these same strengths to forward knowledge, power or goodness.

Martin Seligman

Martin Seligman (2002) argued that genuine happiness and life satisfaction have little to do with pleasure, and much to do with developing personal strengths and character. If cognition operates in the service of motivation (Vohs & Baumeister, 2011), then developing personal strengths and character should lead to increased motivation.

When talking about eudaimonia as a form of wellbeing, the recurring concepts include meaning, higher inspiration, connection, and mastery (David, Boniwell, & Ayers, 2014), all attributes related to cognitive mechanisms of motivation.

The best moments in our lives are not the passive, receptive, relaxing times…the best moments usually occur when a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

These higher motives and their behavioral expressions can also be described as consequences of eudaimonia. According to Haidt (2000), elevating experiences can motivate virtuous behavior.

Seligman (2002) called it a higher pleasure, and Maslow (1973) described a eudemonic person as autonomous, accepting of self, positively relating to others, and possessing a sense of mastery in all of life’s domains (David, Boniwell, & Ayers, 2014). And as this description indicates, these individuals would be highly motivated.

Positive psychology looks at a person and asks, “What could be?” Most importantly, however, positive psychology brings attention to the proactive building of personal strengths and competencies, and these cannot be bad for motivation.

17 Tools To Increase Motivation and Goal Achievement

These 17 Motivation & Goal Achievement Exercises [PDF] contain all you need to help others set meaningful goals, increase self-drive, and experience greater accomplishment and life satisfaction.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

Understanding the principles of motivation gives us the capacity to find workable solutions to real-world motivational problems. For what could ever be more important than empowering those around us toward more intentional action, goal attainment, optimal experience, full functioning, healthy development, and a resilient sense of self?

Studying and applying motivational science can also help us reverse or cope with impulsive urges, habitual experience, goal failure, counterproductive functioning, negative emotion, boredom, maladaptive or dysfunctional development, and fragile sense of self.

If the greatest victory is over self, should we not aspire to rise above our limitations?

Leave us your thoughts on this topic.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free .

According to Self-Determination Theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000), the three motivators of human behavior are:

- autonomy – the need to have control and choice over one’s actions,

- competence – the need to feel capable and effective, and

- relatedness – the need for social connection and interaction with others.

According to the Four-Drive Theory proposed by Paul R. Lawrence and Nitin Nohria, (2002) there are four basic human drives that motivate behavior, the drive to:

- comprehend, and

The four C’s of motivation are (Niemiec & Ryan, 2009);

- competence,

- confidence,

- connection, and

By fostering the four C’s, individuals are more likely to experience a sense of autonomy, relatedness, and competence, which are key components of intrinsic motivation.

- Amabile, T. M., & Kramer, S. J. (2011). The power of small wins. Harvard Business Review . Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2011/05/the-power-of-small-wins.

- Ames, C. (1984). Achievement attributions and self-instructions under competitive and individualistic goal structures. Journal of Educational Psychology, 76 (3), 478-487.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience . Harper & Row.

- David, S. A., Boniwell, I., & Ayers, A. C. (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Happiness. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1995). Human autonomy: The basis for true self-esteem. In M. H. Kernis (Ed.), Efficacy, agency, and self-esteem (pp. 31–49). Plenum Press.

- Deckers, L. (2014). Motivation: Biological, psychological, and environmental (4th ed.) . Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- DiClemente, C. C., & Prochaska, J. O. (1998). Toward a Comprehensive, Transtheoretical Model of Change: Stages of Change and Addictive Behaviors. In W.R. Miller & N. Heather (Eds.). Treating Addictive Behaviors , (2nd. Ed.). New York, NY: Plenum Press.

- Erez, A., & Isen, A. M. (2002). The influence of positive affect on the components of expectancy motivation. Journal of Applied Psychology , 87, 1055–1067.

- Feingold, A. (1983). Happiness, unselfishness, and popularity. Journal of Psychology , 115, 3–5.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences , 359(1449), 1367-1377.

- Graef, R., Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Gianinno, S. M. (1983). Measuring intrinsic motivation in everyday life. Leisure Studies , 2, 155–168.

- Haidt, J. (2000) The Positive emotion of elevation. Prevention & Treatment , Vol 3(1), Mar 2000, No Pagination Specified Article 3c.

- Hart, J. W., Stasson, M. F., Mahoney, J. M. & Story, P. (2007). The Big Five and Achievement Motivation: Exploring the Relationship Between Personality and a Two-Factor Model of Motivation. Individual Differences Research 2007 , Vol. 5, (No. 4), 267–274.

- Izard, C. E. (1993). Emotions . Irvington.

- Kavanagh, D. J. (1987). Mood, persistence, and success. Australian Journal of Psychology , 39, 307–318.

- Keltner, D., & Gross, J. J. (1999). Functional accounts of emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 13 (5), 467-480.

- Lawrence, P. R., & Nohria, N. (2002). Driven: How human nature shapes our choices . John Wiley & Sons.

- Locke, E. A. (1996). Motivation through conscious goal setting. Applied & Preventive Psychology , 5, 117-124.

- Locke, E., Chah, D., Harrison, S., & Lustgarten, N. (1989). Separating the effects of goal specificity from goal level. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes . 43, (2), 270-287.

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1984). Goal setting: A motivational technique that works! Prentice Hall.

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1990). A theory of goal setting & task performance . Prentice-Hall.

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey, American Psychologist , 57, 705-717.

- Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The Benefits of Frequent Positive Affect: Does Happiness Lead to Success? Psychological Bulletin, 131 (6), 803-855.

- Maslow A. H. (1973). Dominance, self-esteem, self-actualization: germinal papers of AH Maslow . Thomson Brooks/Cole.

- Morsella, E., Bargh, J. A., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2009). Oxford Handbook of Human Action . New York, NY: Oxford University Press, USA.

- Niemiec, C. P., & Ryan, R. M. (2009). Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom: Applying self-determination theory to educational practice. Theory and Research in Education, 7(2) , 133-144.

- Reeve, J. (2015). Understanding motivation and emotion (6th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1) , 68-78.

- Schwartz, B., Ward, A. H., Monterosso, J., Lyubomirsky, S., White, K., & Lehman, D. (2002). Maximizing versus satisficing: Happiness is a matter of choice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 83, 1178–1197.

- Seligman, M. E. (2002). Authentic Happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. Simon and Schuster.

- Sheldon, K. M., & Elliot, A. J. (1999). Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: The self-concordance model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(3) , 482-497.

- Vohs, K. D., & Baumeister, R. F. (Eds.). (2011). Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications (2nd ed.). New York, NY, US: Guilford Press.

- Zimmerman, G. L., Olsen C. G., & Bosworth, M. F. (2000). A “Stages of Change” Approach to Helping Patients Change Behavior, American Family Physician. 61 , 1409-1416.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Great teaching, super message 👏

Interesting read, but it appears to be the neurotypical point of view. As an autistic person, most of the article and information did not resonate with me.

Why would you assume that an article that doesn’t mention autism once would take into account the differences in motivation between people with and without autism? Pointless to even leave a comment like this.

How can those with high level of neuroticism find significant motivation to take actions towards realizing their potentials? How can they get more enjoyment from their achievements? Thanks.

Motive of Being (By definition)

I AM .ie ” THE CREATOR” therefore I .ie “ones self” thinks. Ones conscious connects ones conscious self to ones unconscious self that’s why some humans have no idea why they do or don’t do something. The process of quantum mechanics can be manipulated to bend the laws of physics in the physical world just as one’s conscious self can be manipulated by ones unconscious self. This process can be observed in quantum dynamics, whereas the Effects sometimes comes before the Cause, and we are only aware of this because we observed the process, just as an police officers looking over a crime scene to find an motive to a crime.

Can it be really possible that one is given all tips and guides in counselling to achieve greater and greater wellbeing or wellness, but completely divorced of having any thought or concern or even attention to the plight or suffering of fellow humans living perhaps in the next slums or shanties or country sides.? Or as fellow human beings, one needs to be in some way socially caring and reaching out to others, as long as we fall short of creating an egalitarian and equal society. In some developing countries, some self styled gurus and counsellors promise to take people to the land of perfect happiness and wellbeing through all types of workshops and meditation methods etc but no word on their brotherly concern for other fellow humans. Aren’t people being taken for a ride?

Thank you for your heart- warming comment. I couldn’t agree with you more. I truly believe we are made in such a way that we can never get ” to the land of perfect happiness ” unless we take our less fortunate fellow brothers and sisters there with us.

Very nice happy family and other person

I WOULD LIKE TO TALK IF POSSIBLE. I teach gratitude courses, and I am also an active business consultant. I am presently writing essay for Brill publications on “Soulful Exemplar Leadership and Spiritual Motivation. I am most interested in Motivational Psychology, especially in the Pandemic chaos. I am doing webinars on this topic. I think all leadership is about the motivational leadership. I am very Aristotelian in my approach to motivational psychology A William McVey Ph.D. Holy Apostles College and Seminary 913 669-3934

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Victor Vroom’s Expectancy Theory of Motivation

Motivation is vital to beginning and maintaining healthy behavior in the workplace, education, and beyond, and it drives us toward our desired outcomes (Zajda, 2023). [...]

SMART Goals, HARD Goals, PACT, or OKRs: What Works?

Goal setting is vital in business, education, and performance environments such as sports, yet it is also a key component of many coaching and counseling [...]

How to Assess and Improve Readiness for Change

Clients seeking professional help from a counselor or therapist are often aware they need to change yet may not be ready to begin their journey. [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (50)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (29)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (33)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (38)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

3 Goal Achievement Exercises Pack

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Motivation: The Driving Force Behind Our Actions

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Verywell / Emily Roberts

- Improvement

The term motivation describes why a person does something. It is the driving force behind human actions. Motivation is the process that initiates, guides, and maintains goal-oriented behaviors.

For instance, motivation is what helps you lose extra weight, or pushes you to get that promotion at work. In short, motivation causes you to act in a way that gets you closer to your goals. Motivation includes the biological , emotional , social , and cognitive forces that activate human behavior.

Motivation also involves factors that direct and maintain goal-directed actions. Although, such motives are rarely directly observable. As a result, we must often infer the reasons why people do the things that they do based on observable behaviors.

Learn the types of motivation that exist and how we use them in our everyday lives. And if it feels like you've lost your motivation, do not worry. There are many ways to develop or improve your self-motivation levels.

Press Play for Advice on Motivation

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast shares an exercise you can use to help you perform your best. Click below to listen now.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

What Are the Types of Motivation?

The two main types of motivation are frequently described as being either extrinsic or intrinsic.

- Extrinsic motivation arises from outside of the individual and often involves external rewards such as trophies, money, social recognition, or praise.

- Intrinsic motivation is internal and arises from within the individual, such as doing a complicated crossword puzzle purely for the gratification of solving a problem.

A Third Type of Motivation?

Some research suggests that there is a third type of motivation: family motivation. An example of this type is going to work when you are not motivated to do so internally (no intrinsic motivation), but because it is a means to support your family financially.

Why Motivation Is Important

Motivation serves as a guiding force for all human behavior. So, understanding how motivation works and the factors that may impact it can be important for several reasons.

Understanding motivation can:

- Increase your efficiency as you work toward your goals

- Drive you to take action

- Encourage you to engage in health-oriented behaviors

- Help you avoid unhealthy or maladaptive behaviors, such as risk-taking and addiction

- Help you feel more in control of your life

- Improve your overall well-being and happiness

Click Play to Learn More About Motivation

This video has been medically reviewed by John C. Umhau, MD, MPH, CPE .

What Are the 3 Components of Motivation?

If you've ever had a goal (like wanting to lose 20 pounds or run a marathon), you probably already know that simply having the desire to accomplish these things is not enough. You must also be able to persist through obstacles and have the endurance to keep going in spite of difficulties faced.

These different elements or components are needed to get and stay motivated. Researchers have identified three major components of motivation: activation, persistence, and intensity.

- Activation is the decision to initiate a behavior. An example of activation would be enrolling in psychology courses in order to earn your degree.

- Persistence is the continued effort toward a goal even though obstacles may exist. An example of persistence would be showing up for your psychology class even though you are tired from staying up late the night before.

- Intensity is the concentration and vigor that goes into pursuing a goal. For example, one student might coast by without much effort (minimal intensity) while another student studies regularly, participates in classroom discussions, and takes advantage of research opportunities outside of class (greater intensity).

The degree of each of these components of motivation can impact whether you achieve your goal. Strong activation, for example, means that you are more likely to start pursuing a goal. Persistence and intensity will determine if you keep working toward that goal and how much effort you devote to reaching it.

Tips for Improving Your Motivation

All people experience fluctuations in their motivation and willpower . Sometimes you feel fired up and highly driven to reach your goals. Other times, you might feel listless or unsure of what you want or how to achieve it.

If you're feeling low on motivation, there are steps you can take to help increase your drive. Some things you can do to develop or improve your motivation include:

- Adjust your goals to focus on things that really matter to you. Focusing on things that are highly important to you will help push you through your challenges more than goals based on things that are low in importance.

- If you're tackling something that feels too big or too overwhelming, break it up into smaller, more manageable steps. Then, set your sights on achieving only the first step. Instead of trying to lose 50 pounds, for example, break this goal down into five-pound increments.

- Improve your confidence . Research suggests that there is a connection between confidence and motivation. So, gaining more confidence in yourself and your skills can impact your ability to achieve your goals.

- Remind yourself about what you've achieved in the past and where your strengths lie. This helps keep self-doubts from limiting your motivation.

- If there are things you feel insecure about, try working on making improvements in those areas so you feel more skilled and capable.

Causes of Low Motivation

There are a few things you should watch for that might hurt or inhibit your motivation levels. These include:

- All-or-nothing thinking : If you think that you must be absolutely perfect when trying to reach your goal or there is no point in trying, one small slip-up or relapse can zap your motivation to keep pushing forward.

- Believing in quick fixes : It's easy to feel unmotivated if you can't reach your goal immediately but reaching goals often takes time.

- Thinking that one size fits all : Just because an approach or method worked for someone else does not mean that it will work for you. If you don't feel motivated to pursue your goals, look for other things that will work better for you.

Motivation and Mental Health

Sometimes a persistent lack of motivation is tied to a mental health condition such as depression . Talk to your doctor if you are feeling symptoms of apathy and low mood that last longer than two weeks.

Theories of Motivation

Throughout history, psychologists have proposed different theories to explain what motivates human behavior. The following are some of the major theories of motivation.

The instinct theory of motivation suggests that behaviors are motivated by instincts, which are fixed and inborn patterns of behavior. Psychologists such as William James, Sigmund Freud , and William McDougal have proposed several basic human drives that motivate behavior. They include biological instincts that are important for an organism's survival—such as fear, cleanliness, and love.

Drives and Needs

Many behaviors such as eating, drinking, and sleeping are motivated by biology. We have a biological need for food, water, and sleep. Therefore, we are motivated to eat, drink, and sleep. The drive reduction theory of motivation suggests that people have these basic biological drives, and our behaviors are motivated by the need to fulfill these drives.

Abraham Maslow's hierarchy of needs is another motivation theory based on a desire to fulfill basic physiological needs. Once those needs are met, it expands to our other needs, such as those related to safety and security, social needs, self-esteem, and self-actualization.

Arousal Levels

The arousal theory of motivation suggests that people are motivated to engage in behaviors that help them maintain their optimal level of arousal. A person with low arousal needs might pursue relaxing activities such as reading a book, while those with high arousal needs might be motivated to engage in exciting, thrill-seeking behaviors such as motorcycle racing.

The Bottom Line

Psychologists have proposed many different theories of motivation . The reality is that there are numerous different forces that guide and direct our motivations.

Understanding motivation is important in many areas of life beyond psychology, from parenting to the workplace. You may want to set the best goals and establish the right reward systems to motivate others as well as to increase your own motivation .

Knowledge of motivating factors (and how to manipulate them) is used in marketing and other aspects of industrial psychology. It's an area where there are many myths, and everyone can benefit from knowing what works with motivation and what doesn't.

Nevid JS. Psychology: Concepts and Applications .

Tranquillo J, Stecker M. Using intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in continuing professional education . Surg Neurol Int. 2016;7(Suppl 7):S197-9. doi:10.4103/2152-7806.179231

Menges JI, Tussing DV, Wihler A, Grant AM. When job performance is all relative: How family motivation energizes effort and compensates for intrinsic motivation . Acad Managem J . 2016;60(2):695-719. doi:10.5465/amj.2014.0898

Hockenbury DH, Hockenbury SE. Discovering Psychology .

Zhou Y, Siu AF. Motivational intensity modulates the effects of positive emotions on set shifting after controlling physiological arousal . Scand J Psychol . 2015;56(6):613-21. doi:10.1111/sjop.12247

Mystkowska-Wiertelak A, Pawlak M. Designing a tool for measuring the interrelationships between L2 WTC, confidence, beliefs, motivation, and context . Classroom-Oriented Research . 2016. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-30373-4_2

Myers DG. Exploring Social Psychology .

Siegling AB, Petrides KV. Drive: Theory and construct validation . PLoS One . 2016;11(7):e0157295. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157295

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Writing Philosophy Newsletter

The Philosophy and Psychology of Motivation

"in a mildly disturbing fashion,".

Hello again, nothing to say really so let’s get right into it.

Motivation is a good feeling to have. It gives you the power and confidence to move forward even in the most terrible situations. It's what keeps us going, it's what keeps us dreaming and pushing toward the ideal lives we've always wanted. But is this concept actually true? It is difficult to say since we've all at least once experienced a feeling that might have been motivation. But it always disappears the next day. That isn't real motivation, that's just us being in a good mood. But then, of course, there is the motivation of having a reward on the other side, like an increase in salary, or a gift from your parents. But the idea that on a random day your soul is going to set a light with a passionate drive is simply, as far as I've seen, not true. A random day will not forever impact your life, in fact, the opposite is actually the most correct. A planned day will forever impact your life. People, as a general rule of thumb, are lazy. They don't wish to strive for a goal through work and effort, they instead wait, thinking that a miracle will come knocking on their door. This is a sad lie that was taught to them at a very young age. Waiting around for your life and your work to fix itself is a waste of time. If you don't do something no one else will. No one is going to save you. If you want a nice trick to take away from this letter, here it is. No one is going to save you. Imagine you are drinking soup at a restaurant and you start to feel sick. Now imagine the person sitting next to you said, "I've just put poison in your soup, and if you don't finish these math problems within the next twenty minutes I'm not giving you the antidote." And hands you a worksheet with some math problems. You're not passionately driven to do these math problems, but if you don't, you won't get the antidote and you'll die. So you end up doing the math problems. It's the same with life. It doesn't matter whether or not you like doing things, as long as you develop the mentality of no one saving you from living a pointless existence, you can do them. No matter how difficult it is. Sure it's more difficult and risky, but sitting around doing nothing is riskier. That's the lesson you should take away from today. No one is going to save you from having a pointless life except you. So if I were you, I'd be doing something to insure that I don't.

Thanks for reading all the way through, also I’m going to try to post every day now.

Leave a comment

Thanks for reading Writing Philosophy Newsletter! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Other sites

Sign-up page for more blogs onBeehiive

None this time

Ready for more?

‘You never stop grieving…’ Laurent Fignon lost the 1989 Tour de France by eight seconds after more than 3000 km of racing. Photo by Jean-Yves Ruszniewski/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

Don’t beat yourself up

Learning to be kind to yourself when you (inevitably) make mistakes could have a remarkable effect on your happiness.

by Mark Leary + BIO

Human beings are the only creatures who can make themselves miserable. Other animals certainly suffer when they experience negative events, but only humans can induce negative emotions through self-views, judgments, expectations, regrets and comparisons with others. Because self-thought plays such a central role in human happiness and wellbeing, psychologists have devoted a good deal of attention to understanding how people think about themselves.

For many years, the experts have focused on self-esteem. Research has consistently shown that self-esteem is related to psychological wellbeing, suggesting that a positive self-image is an important ingredient in the recipe for a happy and successful life. Seeing this link between self-esteem and an array of desirable life outcomes, many parents bent over backwards to ensure that their children had positive views of themselves, teachers tried to provide feedback in ways that protected students’ self-esteem, and many people became convinced that self-esteem should be widely promoted as a remedy for personal problems and social ills. The high-water mark of the self-esteem movement occurred in the 1980s when the California State Assembly authorised funds to raise the self-esteem of its citizens, with the lofty goal of solving problems such as child abuse, crime, addiction, unwanted pregnancy and welfare dependence. Some legislators even hoped that, as a side benefit, boosting self-esteem would enhance the state’s economy.

On one level, this emphasis on self-esteem seemed well-founded. Psychological research shows that success and wellbeing are associated with high self-esteem, and that people with lower self-esteem suffer a disproportionate share of emotional and behavioural problems. Yet, self-esteem has not lived up to its billing. Not only are the relationships between self-esteem and positive outcomes weaker than many suppose, but a closer look at the evidence shows that self-esteem appears to be the result of success and wellbeing rather than their cause. Although thousands of studies demonstrate that high self-esteem is associated with many good things, virtually no evidence shows that self-esteem actually causes success, happiness or other desired outcomes.

Despite the failure of the self-esteem movement, no one would doubt that certain ways of thinking about oneself are more beneficial than others. We all know people who create a great deal of unhappiness for themselves simply by how they think about and react to the events in their lives. Many people push themselves to meet their own unreasonable expectations, berate themselves for their flubs and failures, and blow their difficulties out of proportion. In an odd sort of way, these people are rather mean to themselves, treating themselves far more harshly than they treat other people. However, we all also know people who take a kinder and gentler approach to themselves. They might not always be happy with themselves, but they accept the fact that everyone has shortcomings and problems, and don’t criticise and condemn themselves unnecessarily for the normal problems of everyday life.

These two reactions to shortcomings, failures and problems might appear to reflect a difference in self-esteem but, in fact, the key difference involves not self-esteem but rather self-compassion. That is, the difference lies not so much in how people evaluate themselves (their self-esteem) but rather in how they treat themselves (their self-compassion). And, as it turns out, the latter appears to be far more important for wellbeing than the former. Of course, people prefer to evaluate themselves favourably rather than unfavourably, but self-compassion has the power to influence people’s emotions and behaviours in ways that self-esteem does not.

T o understand what it means to be self-compassionate, think about what it means to treat another person compassionately, and then turn that same orientation toward oneself. Just as compassion involves a desire to minimise the suffering of others, self-compassion reflects a desire to minimise one’s own suffering and, just as importantly, to avoid creating unnecessary unhappiness and distress for oneself. Self-compassionate people treat themselves in much the same caring, kind and supportive ways that compassionate people treat their friends and family when they are struggling. When they confront life’s problems, self-compassionate people respond with warmth and concern rather than judgment and self-criticism. Whether their problems are the result of their own incompetence, stupidity or lack of self-control, or occur through no fault of their own, self-compassionate people recognise that difficulties are a normal part of life. As a result, they approach their problems with equanimity, neither downplaying the seriousness of their challenges nor being overwhelmed by negative thoughts and feelings.

Kristin Neff, a developmental psychologist at the University of Texas at Austin, first brought the construct of self-compassion to the attention of psychological scientists and practitioners in 2003 . Since then, research has shown that self-compassion is robustly associated with every indicator of psychological wellbeing that has been investigated. People who are higher in self-compassion show greater emotional stability, are more resilient, have a more optimistic perspective, and report greater life satisfaction. They are also less likely to display signs of psychological problems such as depression and chronic anxiety.

People who are high in self-compassion deal more successfully with negative events – such as failure, rejection and loss – than people who are low in self-compassion. Whether the problem is a minor daily hassle, a major traumatic event or a chronic problem, people who treat themselves with compassion respond more adaptively than people who don’t. Just as receiving compassion from another person helps us to cope with the slings and arrows of life, being compassionate to ourselves has much the same effect.

In one study , we asked people to answer questions about the worst thing that had happened to them in the past four days. Although self-compassion was not related to how ‘bad’ participants rated the events they reported, people who were high in self-compassion had less negative, pessimistic and self-critical thoughts about the events, and experienced fewer negative emotions. Self-compassionate people also indicated that they tried to be kind to themselves in the face of whatever difficulties they experienced, much as they would respond to a friend with similar problems.

Self-compassion was particularly helpful for older people who were in poor physical health

Self-compassion might be particularly useful when people confront serious, life-changing experiences. For example, a recent study showed that those who had recently separated from their long-term romantic partners showed less distress about the breakup if they were high in self-compassion.

Getting older brings undesired changes, many of which involve lapses or failures, as when people can’t remember things or have trouble performing everyday tasks. Even though they would treat their friends’ struggles with kindness and compassion, many older people become intolerant and angry, criticising themselves and bemoaning their inability to function as they once did. Others, meanwhile, seem to take ageing more in their stride, accepting their lapses, and treating themselves especially nicely when they have particularly bad days.

Our research shows that people who are higher in self-compassion cope better with the challenges of ageing than those who are less self-compassionate: they had higher wellbeing, fewer emotional problems, greater satisfaction with life, and felt that they were ageing more successfully. Self-compassion was particularly helpful for older people who were in poor physical health. In fact, as long as they were high in self-compassion, people with health problems reported wellbeing and life satisfaction that was as high as those without such problems.

Likewise, we found that self-compassion was related to lower stress, anxiety and shame among people who were living with HIV. Because they were less self-critical and ashamed, those who were higher in self-compassion were also more likely to disclose their HIV status to others. Something about being self-compassionate led individuals confronting a serious, life-changing illness to adapt more successfully.

T o understand how self-compassion works, consider how people respond to negative events. When we are upset about something, our reactions stem from three distinct sources. First is the instigating problem and our analysis of the threat that it poses to our wellbeing – what psychologists call the primary appraisal. Whether we are dealing with a failure, rejection, a health problem, losing a job, a speeding ticket or simply a misplaced set of car keys, a portion of our emotional distress is a reaction to the negative implications of the event.

Second, people analyse their ability to cope with the consequences of the problem. Those who think that they cannot handle the problem emotionally will be more upset than those who think that they’ll make it through.

Third comes blame and guilt. When problems arise, we often think about the role that we played – the extent to which we were responsible and what, if anything, this says about us. People often experience additional distress when they believe that the problem arose through their own incompetence, stupidity or lack of self-control. Of course, assessing one’s responsibility is sometimes useful, but people often go beyond an objective assessment of their responsibility to blaming, criticising and even punishing themselves. This self-inflicted cruelty increases whatever distress the original problem is already causing.

Treating oneself compassionately helps to ameliorate all three of these sources of distress. One can reduce some of the initial angst by soothing oneself, just as one might soothe another person’s upset through concern and kindness.

In The Compassionate Mind (2009), Paul Gilbert, a British psychologist who has explored the therapeutic benefits of self-compassion, suggests that self-directed compassion triggers the same physiological systems as receiving care from other people. Treating ourselves in a kind and caring way has many of the same effects as being supported by others.

When people do not add to their distress through self-recrimination, they can look life more squarely in the eye and see it for how it really is

Just as importantly, self-compassion eliminates the additional distress that people often heap on themselves through criticism and self-blame. Again, the parallel with other-directed compassion is informative. I might not be able to make my friend who lost his job feel better, but I certainly won’t make him feel worse by telling him what a failure he is. Yet, people who are low in self-compassion talk to themselves in precisely such discourteous ways.

One central feature of self-compassion that helps to lower distress is what Neff calls common humanity . People high in self-compassion recognise that everyone has problems and suffers. Millions of other people have experienced similar events, and many are dealing with similar problems right now. Although recognising one’s connections with the shared human experience might not reduce our reactions to the original problem, it does remind us not to personalise what has happened or to conclude that our problems are somehow worse than everyone else’s. Viewing one’s problems through the lens of common humanity also lowers the sense of isolation people sometimes experience when they are suffering. It helps to remember that we’re all in this together.

Importantly, self-compassion is not just positive thinking. In fact, self-compassion is associated with a more realistic appraisal of one’s situation and one’s responsibility for it. When people do not add to their distress through self-recrimination and catastrophising, they can look life more squarely in the eye and see it for how it really is. Self-compassionate people have a more accurate, balanced and non-defensive reaction to the events they experience.

Most research on self-compassion has examined its relationship to emotion, but it also has implications for people’s motivation and behaviour. Strong emotions can undermine effective behaviour by leading people to focus on reducing their distress rather than managing the original problem. If unchecked because a person lacks self-compassion, negative reactions foster denial, avoidance and a difficulty or unwillingness to face the problem, leading to dysfunctional coping behaviours. To the extent that self-compassionate people respond with greater equanimity, they respond more effectively to the challenges they confront.

For example, in one study, university students who fared worse than desired on an exam subsequently performed better on the next test if they were high rather than low in self-compassion. Presumably, students low in self-compassion beat themselves up and overreacted, which led them to avoid the issue. Students high in self-compassion surveyed the situation and their role in it, and took steps to improve in the future. Similarly, in our study of people living with HIV, participants who were low in self-compassion indicated that shame about being HIV-positive interfered with their willingness to seek medical and psychological care, whereas those high in self-compassion took better care of themselves. Self-compassion was related both to better psychological adjustment and more adaptive behaviours.

S ome people resist the idea that they should be more self-compassionate. Many people assume that self-compassion reflects Pollyanna-ish thinking, denying reality or, worse, self-indulgence. In this view, self-compassion means ignoring one’s problems, shirking responsibility, having low standards, and going easy on oneself. People who believe that being tough on oneself motivates hard work, appropriate behaviour and success worry that self-compassion will undermine their performance.

These concerns reflect a lack of understanding of what self-compassion actually involves. It is not indifference to what happens or how one behaves. Nor is it a blindly positive outlook or an excuse to be lazy or shirk responsibility. Instead, self-compassion is based on wanting the best for oneself. Just as compassion for other people arises from a concern for their wellbeing and a desire to relieve their suffering, self-compassion involves desiring the best for oneself and responding in ways that promote one’s wellbeing. Self-compassionate people want to reduce their current problems, but they also want to respond in ways that promote their wellbeing down the road, and being lazy and unmotivated is not likely to help. Self-compassionate people realise when they have behaved badly, made poor decisions or failed, and they are sometimes unhappy with themselves or with events that occur. But, paradoxically, taking an accepting and compassionate approach to oneself at such times can help to maintain motivation and improve performance.

In one study , inviting people to think about a negative behaviour in a self-compassionate manner led participants to accept more personal responsibility for that behaviour. Viewing one’s problems with a gentle, caring perspective allows people to confront their difficulties head-on without minimising them. They know that a certain amount of self-judgment is needed to maintain desired behaviour, but they are no more critical toward themselves than needed. People who seek what’s best for themselves recognise that they don’t need to punish themselves to know that good behaviour and hard work are important.

Self-compassion is a teachable skill: people can learn to become more self-compassionate. Studies have demonstrated that even brief exercises instructing people to think about a problem in a self-compassionate manner can have positive effects. Other studies show that when psychologists help their clients to master the techniques, their level of anguish abates.

The first step in cultivating self-compassion is to start noticing instances in which you are not being nice to yourself. Are you telling yourself harsh and unkind things in your mind? Do you punish yourself by pushing yourself too hard or depriving yourself of pleasure when things go wrong? Would you treat a loved one this way under similar circumstances?

A self-compassionate person recognises the problem, fixes it if possible, and moves on without making a dramatic production out of it

If you catch yourself treating yourself badly and increasing your distress, ask yourself why. Is it because you think that being hard on yourself helps to motivate you, makes you behave appropriately, or increases your success? To some extent, you might be correct: negative thoughts and feelings do help us to manage our behaviour. The question, though, is how badly you need to feel in order to motivate yourself. People who are low in self-compassion often make themselves feel far worse than needed to stay on track. A little bit of self-criticism can go a long way.

When bad things happen or you behave in a less-than-desirable way, remind yourself that everyone fails, misbehaves, is rejected, experiences loss, is humiliated, and experiences myriad negative events. That doesn’t mean that these events are OK, but it does mean that there’s nothing unusual or personal in what happened. A self-compassionate person recognises the problem, fixes it if possible, deals with it emotionally, and moves on without making a dramatic production out of it.

Finally, learn to cultivate self-kindness. Treat yourself nicely, both in your own mind and in how you behave toward yourself. Many people are surprised to see that they are often much nicer to other people than to themselves.

Fortunately, people can respond self-compassionately no matter how they feel about themselves at the time. Unlike self-esteem, which is based on favourable judgments of one’s personal characteristics, self-compassion does not depend on viewing oneself positively or liking oneself. In fact, self-compassion is often most beneficial when events undermine one’s sense of competence, desirability, control or value. It is much easier to treat oneself nicely than to evaluate oneself positively.

Self-compassion is hardly a panacea for the struggles of life, but it can be an antidote to the cruelty we sometimes inflict on ourselves. Most of us want to be nice people, so why not be as nice to ourselves as we are to others?

Metaphysics

The enchanted vision

Love is much more than a mere emotion or moral ideal. It imbues the world itself and we should learn to move with its power

Mark Vernon

Human rights and justice

My elusive pain

The lives of North Africans in France are shaped by a harrowing struggle to belong, marked by postcolonial trauma

Farah Abdessamad

Neuroscience

How to make a map of smell

We can split light by a prism, sounds by tones, but surely the world of odour is too complex and personal? Strangely, no

Jason Castro

Psychiatry and psychotherapy

The therapist who hated me

Going to a child psychoanalyst four times a week for three years was bad enough. Reading what she wrote about me was worse

Michael Bacon

Consciousness and altered states

A reader’s guide to microdosing

How to use small doses of psychedelics to lift your mood, enhance your focus, and fire your creativity

Tunde Aideyan

Family life

A patchwork family

After my marriage failed, I strove to create a new family – one made beautiful by the loving way it’s stitched together

(Stanford users can avoid this Captcha by logging in.)

- Send to text email RefWorks EndNote printer

Autonomy : an essay in philosophical psychology and ethics

Available online, at the library.

Green Library

More options.

- Find it at other libraries via WorldCat

- Contributors

Description

Creators/contributors, contents/summary, bibliographic information, browse related items.

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

1-800-488-6040

- My Career or Business

- My Health & Vitality

- My Mental Health

- My Finances & Building Wealth

- My Relationship

- My Leadership Skills

- My Productivity

- Growth Solutions

- About Tony Robbins

- The Science of Tony Robbins

- Contribution

- Company Culture

- Get Involved

- Success Stories

- Case Studies

- Events Calendar

- The Unshakeable Business

- Unleash the Power Within

- Business Mastery

- Date With Destiny

- Life Mastery Virtual

- Wealth Mastery Virtual

- Life & Wealth Mastery Fiji

- Leadership Academy

- Inner Circle Community

- Pinnacle Enterprise

- Platinum Partnership

- Unleash Her Power Within

- Business Coaching

- Results Coaching

- Business Results Training

- Life Coaching

- Health Coaching

- Meet Tony’s Coaches

- All Products

- Nutraceuticals

- Life Force Book

- Tony Robbins Books

- Training Systems

- Breakthrough App

- Netflix Documentary

- Free Tools & Quizzes

Home » Personal growth » What is self-motivation?

How to self-motivate

What goal are you working toward right now? Maybe it’s getting in better shape or advancing in your career. Perhaps it’s discovering how to be a better romantic partner or parent to your children. Whatever the goal, think about why you haven’t reached it yet. What’s holding you back?

The answers that first come to mind might be external factors. You don’t have the time. You don’t have the skills. You don’t have the money. While these things might play a role in your lack of progress , what it really comes down to is a lack of self-motivation . When you’re driven and resourceful, you can accomplish anything you set your mind to – as long as you have the willpower to achieve it .

What is self-motivation?

Most self-motivation definitions consider how you can find the ability to do what needs to be done without influence from other people or situations. Self-motivation is encouraging yourself to continue making progress toward a goal even when it feels challenging. It’s turning your shoulds into musts.

Think of some of the most successful people you know. Are they the smartest people you’ve ever met? The wealthiest? Chances are, they’re not – but they are the most motivated to succeed. As Tony Robbins says, “The one common denominator of all successful people is their hunger to push through their fears.” When you have enough hunger, you can easily learn how to self-motivate to meet the goals you’ve set your mind and focus on.

Boost your focus and motivation with Tony’s priming method

Why is self-motivation essential?

The ability to self-motivate is the only sure-fire way to achieve your goals and get everything you want in life. You won’t always have parents, teachers or bosses to direct your energy or provide external motivations. You need to cultivate and draw on inner strength – a deep confidence in yourself that is completely unaffected by outside events and experiences. When you have this type of belief in yourself , you’ll be unstoppable.

Self-motivation is also essential to finding a fulfilling career – and to acing job interviews. The question “Are you self-motivated?” often comes up during the interview process, and it’s not always easy to answer. Employers ask this to see if you’re a good culture fit and if you’ll be enthusiastic about the work you’ll be doing. To be prepared, think of a few examples: times that you felt especially motivated about your work or when you set a big goal and achieved it with self-motivation . You’ll demonstrate your passion and make a connection with the interviewer.

What drives self-motivation?

So, why do so many people find themselves lacking motivation? The truth is that self-motivation techniques all come down to your psychology. First, you have to clearly know what it is you want. Why do you want to improve your connection with your partner ? Is it so you can deepen the trust and love between you, ultimately creating a healthy relationship and long-lasting bond? Think of the reason why you want to succeed and turn to this when things seem tough and you need help with self-motivation .

Then, you need to assess the emotion and meaning you’re attaching to your successes and failures.

When you face a setback, do you tell yourself you’re not good enough to succeed? If so, it’s time to seriously change your psychology. To truly answer the question “ What is self-motivation ?,” you need to be in the mindset that you’re already motivated. When it’s time to self-motivate, think of the positive state you want to be in to get things done. How does your body feel when you’re motivated? Where are your energy levels? What messages are you conveying with your body language?

By tapping into the positive state that you associate with self-motivation , you’ll be able to self-motivate more easily and often.

13 self-motivation techniques for reaching your goals

1) take responsibility for your life.

Self-motivation is often difficult because it comes from you. If you don’t take care of the underlying issues that keep you from making progress, you can fall back on blaming others for your failure. In some cases, you can rely on external factors and friends for motivation, but at the end of the day, you’re the one who has to put in the work. You’re the one who must take charge of your life.

2) Find your why

Tony often says that, “People are not lazy. They simply have impotent goals – that is, goals that do not inspire them.” Before you can learn how to self-motivate , you need to find your why . You need a compelling purpose that goes beyond material things or climbing the career ladder. Why do you want to build a business? It likely goes back to the ability to do what you want, when you want and with whom you want – the true definition of success . Connect your goals back to your purpose and you’ll never lack self-motivation .

3) Reevaluate your goals

Tony also says, “At any moment, the decision you make can change the course of your life forever.” If you’re focused on your vision and purpose, but you’re still not feeling inspired, you may need to make a decision to go in a new direction. In other words, if your why isn’t motivating you, then you may need a new why. Reevaluate your blueprint for your life and don’t hesitate to create new goals. As long as you’re making progress, you’re ahead of everyone who isn’t making an effort.

4) Create empowering beliefs

The only limitations in our lives are the ones we put on ourselves. If you don’t have enough self-motivation , it comes down to one reason: you don’t see yourself as a self-motivated person. Change your negative beliefs into positive ones by conditioning your mind and creating empowering beliefs . Catch yourself when you think negatively about yourself and transform that self-talk so that it motivates you instead of holding you back.

5) Learn better time management strategies

Sometimes the key to self-motivation is having the necessary time-management tools and strategies under your belt. How are you managing your time? Find ways to stop procrastinating and start making progress, like chunking, the Rapid Planning Method TM and N.E.T. time (No Extra Time time).

6) Create a massive action plan

Self-motivation techniques can be as straightforward as creating a massive action plan : writing down what it is you want, identifying your purpose behind it and creating a series of steps to help you reach your goal. Once you have your plan documented, you can refer to this for additional motivation when things get challenging along the way.

7) Look to the success of others

Turning to inspirational quotes for motivation or looking toward a mentor for advice can help you on your path to success. Read more about famous role models or leaders you look up to and see how they utilize self-motivation . You may be able to pick up some t echniques or gain some inspira tion as you read about their strategies and struggles.

8) Use the power of music

Our brains are hardwired to respond to music . Tapping into the types of beats and rhythms that boost your mood and energy levels is a great way to get yourself out of a slump and more focused on the task at hand. Always have a pair of earbuds and your favorite playlist nearby so you can harness the power of music when you need a jolt of self-motivation .

9) Schedule outdoors time

Even the most energized people will eventually get run down if they spend too much time in cramped spaces with artificial light . When learning how to self-motivate to reach your goals, don’t make the mistake of burning the midnight oil and staying confined to your office. Getting outside and spending time in nature every day is a perfect way to take a break, boost energy and replenish your self-motivation .

10) Banish multitasking

You may think that working on three projects at the same time is the best way to get things done and that your self-motivation will soar when you can simultaneously check multiple to-dos off your list. You’re wrong. Multi-tasking diminishes focus , and as Tony says , where focus goes, energy flows. Select the most important task you need to work on and concentrate solely on that until you’ve accomplished what you need to, then move on to the next one.

11) Get moving

Self-motivation becomes much easier when you’re already in motion. It doesn’t matter whether you are figuring out how to self-motivate toward working out, tackling your tasks at work or preparing for that big presentation; the more you move, the more energy you will have. Movement doesn’t have to be limited to the gym. You can easily incorporate movement throughout your day by taking the stairs, walking around your home while on the phone or incorporating these desk exercises into your day .

12) Visualize your self-motivation

Having trouble taking those first steps toward a goal? Visualize yourself as already active in that part of your life, when the goal is achieved. Use this priming exercise first thing in the morning: When you do this, you bridge that gap from inaction to action just by priming yourself for success.

13) Focus on gratitude

It can be very difficult to learn how to self-motivate when you get caught up in negativity. Focus on gratitude and adopt an abundance mindset . Be thankful for all the good things in your life and steer your focus from all the things you wish you had. Stop comparing yourself to others and understand that life is happening for you , not to you. The more you look at everything good in your life, the more of it you will attract and the easier it will be to self-motivate to attract even more.

Ready for the motivation boost you need?

Find the self-motivation you need to conquer the obstacles hindering your progress. Take Tony Robbins’ Driving Force quiz and discover what drives your every action.

© 2024 Robbins Research International, Inc. All rights reserved.

Welcome to the new, improved Literate Lizard! We're excited to see you. *** RETURNING USERS WILL NEED TO RESET THEIR PASSWORD FOR THIS NEW SITE. CLICK HERE TO RESET YOUR PASSWORD.*** Close this alert

Self-theories: Their Role in Motivation, Personality, and Development (Essays in Social Psychology)

Description.

This innovative text sheds light on how people work -- why they sometimes function well and, at other times, behave in ways that are self-defeating or destructive. The author presents her groundbreaking research on adaptive and maladaptive cognitive-motivational patterns and shows:

* How these patterns originate in people's self-theories * Their consequences for the person -- for achievement, social relationships, and emotional well-being * Their consequences for society, from issues of human potential to stereotyping and intergroup relations * The experiences that create them

This outstanding text is a must-read for researchers in social psychology, child development, and education, and is appropriate for both graduate and senior undergraduate students in these areas.

Other Books in Series

Nostalgia: A Psychological Resource (Essays in Social Psychology)

The Psychology of Closed Mindedness (Essays in Social Psychology)

Complex Interpersonal Conflict Behaviour: Theoretical Frontiers (Essays in Social Psychology)

Self-Insight: Roadblocks and Detours on the Path to Knowing Thyself (Essays in Social Psychology)

When Groups Meet: The Dynamics of Intergroup Contact (Essays in Social Psychology)

Reducing Intergroup Bias: The Common Ingroup Identity Model (Essays in Social Psychology)

Motivated Cognition in Relationships: The Pursuit of Belonging (Essays in Social Psychology)

Standards and Expectancies: Contrast and Assimilation in Judgments of Self and Others (Essays in Social Psychology)

Conceptual Metaphor in Social Psychology: The Poetics of Everyday Life (Essays in Social Psychology)

The Uncertain Mind: Individual Differences in Facing the Unknown (Essays in Social Psychology)

Cooperation in Groups: Procedural Justice, Social Identity, and Behavioral Engagement (Essays in Social Psychology)

You may also like.

The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma

Subscribe to our newsletter.

You'll receive discounts, book reviews and publishing news.

Mindset Theory and School Psychology

Abstract: mindset theory is an achievement motivation theory that centers on the concept of the malleability of abilities. according to mindset theory, students tend to have either a growth mindset or a fixed mindset about their intelligence; students with a growth mindset tend to believe that intelligence is malleable, whereas students with fixed mindsets tend to believe that intelligence is unchangeable. as described in many empirical and theoretical papers, the mindset a student holds can influence important psycholo… show more.

Search citation statements

Paper Sections

Citation Types

Year Published

Publication Types

Relationship

Cited by 9 publication s

References 49 publication s, the influence of achievement motivation on college students’ employability: a chain mediation analysis of self-efficacy and academic performance.