Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 1, Issue 1

Nursing, research, and the evidence

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Anne Mulhall , MSc, PhD

- Independent Training and Research Consultant West Cottage, Hook Hill Lane Woking, Surrey GU22 0PT, UK

https://doi.org/10.1136/ebn.1.1.4

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Why has research-based practice become so important and why is everyone talking about evidence-based health care? But most importantly, how is nursing best placed to maximise the benefits which evidence-based care can bring?

Part of the difficulty is that although nurses perceive research positively, 2 they either cannot access the information, or cannot judge the value of the studies which they find. 3 This journal has evolved as a direct response to the dilemma of practitioners who want to use research, but are thwarted by overwhelming clinical demands, an ever burgeoning research literature, and for many, a lack of skills in critical appraisal. Evidence-Based Nursing should therefore be exceptionally useful, and its target audience of practitioners is a refreshing move in the right direction. The worlds of researchers and practitioners have been separated by seemingly impenetrable barriers for too long. 4

Tiptoeing in the wake of the movement for evidence-based medicine, however, we must ensure that evidence-based nursing attends to what is important for nursing. Part of the difficulty that practitioners face relates to the ambiguity which research, and particularly “scientific” research, has within nursing. Ambiguous, because we need to be clear as to what nursing is, and what nurses do before we can identify the types of evidence needed to improve the effectiveness of patient care. Then we can explore the type of questions which practitioners need answers to and what sort of research might best provide those answers.

What is nursing about?

Increasingly, medicine and nursing are beginning to overlap. There is much talk of interprofessional training and multidisciplinary working, and nurses have been encouraged to adopt as their own some tasks traditionally undertaken by doctors. However, in their operation, practice, and culture, nursing and medicine remain quite different. The oft quoted suggestion is that doctors “cure” or “treat” and that nurses “care”, but this is not upheld by research. In a study of professional boundaries, the management of complex wounds was perceived by nurses as firmly within their domain. 5 Nurses justified their claim to “control” wound treatment by reference to scientific knowledge and practical experience, just as medicine justifies its claim in other areas of treatment. One of the most obvious distinctions between the professions in this study was the contrast between the continual presence of the nurse as opposed to the periodic appearance of the doctor. Lawler raises the same point, and suggests that nurses and patients are “captives” together. 6 Questioning the relevance of scientific knowledge, she argues that nurses and patients are “focused on more immediate concerns and on ways in which experiences can be endured and transcended”. This highlights the particular contribution of nursing, for it is not merely concerned with the body, but is also in an “intimate” and ongoing relationship with the person within the body. Thus nursing becomes concerned with “untidy” things such as emotions and feelings, which traditional natural and social sciences have difficulty accommodating. “It is about the interface between the biological and the social, as people reconcile the lived body with the object body in the experience of illness.” 7

What sort of evidence does nursing need?

These arguments suggest that nursing, through its particular relationship with patients and their sick or well bodies, will rely on many different ways of knowing and many different kinds of knowledge. Lawler's work on how the body is managed by nurses illustrates this. 6 She explains how an understanding of the physiological body is essential, but that this must be complemented by evidence from the social sciences because “we also practice with living, breathing, speaking humans.” Moreover, this must be grounded in experiential knowledge gained from being a nurse, and doing nursing. Knowledge, or evidence, for practice thus comes to us from a variety of disciplines, from particular paradigms or ways of “looking at” the world, and from our own professional and non-professional life experiences.

Picking the research design to fit the question

Scientists believe that the social world, just like the physical world, is orderly and rational, and thus it is possible to determine universal laws which can predict outcome. They propose the idea of an objective reality independent of the researcher, which can be measured quantitatively, and they are concerned with minimising bias. The other major paradigm is interpretism/naturalism which takes another approach, suggesting that a measurable and objective reality separate from the researcher does not exist; the researcher cannot therefore be separated from the “researched”. Thus who we are, what we are, and where we are will affect the sorts of questions we pose, and the way we collect and interpret data. Furthermore, in this paradigm, social life is not thought to be orderly and rational, knowledge of the world is relative and will change with time and place. Interpretism/naturalism is concerned with understanding situations and with studying things as they are. Research approaches in this paradigm try to capture the whole picture, rather than a small part of it.

This way of approaching research is very useful, especially to a discipline concerned with trying to understand the predicaments of patients and their relatives, who find themselves ill, recovering, or facing a lifetime of chronic illness or death. Questions which arise in these areas are less concerned with causation, treatment effectiveness, and economics and more with the meaning which situations have—why has this happened to me? What is my life going to be like from now on? The focus of these questions is on the process, not the outcome. Data about such issues are best obtained by interviews or participant observation. These are aspects of nursing which are less easily measured and quantified. Moreover, some aspects of nursing cannot even be formalised within the written word because they are perceived, or experienced, in an embodied way. For example, how do you record aspects of care such as trust, empathy, or “being there”? Can such aspects be captured within the confines of research as we know it?

Questions of causation, prognosis, and effectiveness are best answered using scientific methods. For example, rates of infection and thrombophlebitis are issues which concern nurses looking after intravenous cannulas. Therefore, nurses might want access to a randomised controlled trial of various ways in which cannula sites are cleansed and dressed to determine if this affects infection rates. Similarly, some very clear economic and organisational questions might be posed by nurses working in day surgery units. Is day surgery cost effective? What are the rates of early readmission to hospital? Other questions could include: what was it like for patients who had day surgery? Did nurses find this was a satisfying way to work? These would be better answered using interpretist approaches which focus on the meaning that different situations have for people. Nurses working with patients with senile dementia might also use this approach for questions such as how to keep these patients safe and yet ensure their right to freedom, or what it is like to live with a relative with senile dementia. Thus different questions require different research designs. No single design has precedence over another, rather the design chosen must fit the particular research question.

Research designs useful to nursing

Nursing presents a vast range of questions which straddle both the major paradigms, and it has therefore embraced an eclectic range of research designs and begun to explore the value of critical approaches and feminist methods in its research. 8 The current nursing literature contains a wide spectrum of research designs exemplified in this issue, ranging from randomised controlled trials, 9 and cohort studies, 10 at the scientific end of the spectrum, through to grounded theory, 11 ethnography, 12 and phenomenology at the interpretist/naturalistic end. 13 Future issues of this journal will explore these designs in depth.

Maximising the potential of evidence-based nursing

Evidence-based care concerns the incorporation of evidence from research, clinical expertise, and patient preferences into decisions about the health care of individual patients. 14 Most professionals seek to ensure that their care is effective, compassionate, and meets the needs of their patients. Therefore sound research evidence which tells us what does and does not work, and with whom and where it works best, is good news. Maximum use must be made of scientific and economic evidence, and the products of initiatives such as the Cochrane Collaboration. However, nurses and consumers of health care clearly need other evidence, arising from questions which cannot be framed in scientific or economic terms. Nursing could spark some insightful debate concerning the nature and contribution of other types of knowledge, such as clinical intuition, which are so important to practitioners. 15

In summary, in embracing evidence-based nursing we must heed these considerations:

Nursing must discard its suspicion of scientific, quantitative evidence, gather the skills to critique it, and design imaginative trials which will assist in improving many aspects of nursing

We must promulgate naturalistic/interpretist studies by indicating their usefulness and confirming/explaining their rigour in investigating the social world of health care

More research is needed into the reality and consequences of adopting evidence-based practice. Can practitioners act on the evidence, or are they being made responsible for activities beyond their control?

It must be emphasised that those concerns which are easily measured or articulated are not the only ones of importance in health care. Space is needed to recognise and explore the knowledge which comes from doing nursing and reflecting on it, to find new channels for speaking of concepts which are not easily accommodated within the discourse of social or natural science—hope, despair, misery, love.

- ↵ Bostrum J, Suter WN. Research utilisation: making the link with practice. J Nurs Staff Dev 1993 ; 9 : 28 –34. OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ Lacey A. Facilitating research based practice by educational intervention. Nurs Educ Today 1996 ; 16 : 296 –301.

- ↵ Pearcey PA. Achieving research based nursing practice. J Adv Nurs 1995 ; 22 : 33 –9. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Mulhall A. Nursing research: our world not theirs? J Adv Nurs 1997 ; 25 : 969 –76. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Walby S, Greenwell J, Mackay L, et al. Medicine and nursing: professions in a changing health service . London: Sage, 1994.

- ↵ Lawler J. The body in nursing . Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1997.

- ↵ Lawler J. Behind the screens nursing . Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1991.

- ↵ Street AF. Inside nursing: a critical ethnography of clinical nursing practice . New York: State University Press of New York, 1992.

- ↵ Madge P, McColl J, Paton J. Impact of a nurse-led home management training programme in children admitted to hospital with acute asthma: a randomised controlled study. Thorax 1997 ; 52 : 223 –8. OpenUrl Abstract

- ↵ Kushi LH, Fee RM, Folsom AR, et al . Physical activity and mortality in postmenopausal women. JAMA 1997 ; 277 : 1287 –92. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Rogan F, Shmied V, Barclay L, et al . Becoming a mother: developing a new theory of early motherhood. J Adv Nurs 1997 ; 25 : 877 –85. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Barroso J. Reconstructing my life: becoming a long-term survivor of AIDS. Qual Health Res 1997 ; 7 : 57 –74. OpenUrl CrossRef Web of Science

- ↵ Thibodeau J, MacRae J. Breast cancer survival: a phenomenological inquiry. Adv Nurs Sci 1997 ; 19 : 65 –74. OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ Sackett D, Haynes RB. On the need for evidence-based medicine . Evidence-Based Medicine 1995 ; 1 : 5 –6. OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Gordon DR Tenacious assumptions in Western biomedicine. In: Lock M, Gordon DR , eds . Biomedicine Examined. London: Kluwer Academic Press, 1988;19–56.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

The power of nurses in research: understanding what matters and driving change

The next blog in our series focussing on how research evidence can be implemented into practice, Julie Bayley, Director of the Lincoln Impact Literacy Institute writes about the power of nurses in research and how nurses can support the whole research journey.

Research is a funny old beast isn’t it? It starts life as a glint in a researcher’s eye, then like a child needs nurturing, shuttling back and forth to events and usually requires constant checking to make sure it’s not doing something stupid.

As someone who spends the majority of their working life on impact – the provable benefits of research outside of the world of academia – it is extraordinarily clear to me how research can make the world better. And as a patient advocate – having chronically and not exactly willingly collected DVTs over the last decade – it’s even more clear how good research and good care together make a difference that matters.

Having had some AMAZING care, nursing strikes me as both an art and a science. A brilliant technical understanding of healthcare processes combined magically with kindness, compassion and care. Having been hugged by nurses as I cried being separated from my newborn (post DVT), and watching nurses let dad happily talk them through his army photo album as they check on his dementia, I am in no doubt that such compassion is what marks the difference between not just being a patient, but being a person .

One of the oddities about research is how we can so often get the impression that only big and shiny counts. ‘Superpower’ studies such as Randomised Controlled Trials, and multi-national patient cohort studies are amazing, but can mask the breadth of the millions of questions research can explore in endless different ways. Of course we need trials to determine ‘what works’, but we also need research to unveil the stories of those who feel their rarely heard, understand how things work, and connect research to people’s lives.

Research essentially is just the act of questioning in a structured, ethical and transparent way. It might seek to understand things through numbers (quantitative) or words and experiences (qualitative), and may reveal something new or confirm something we already believe. Research is the bedrock of evidence based care, allowing us – either through new (‘primary’) or existing (‘secondary’) data – to explore, understand, confirm or disprove ways patients can be helped. Some of you reading this will be very research active, some of you might think it’s not for you, some may not know where to start, and others may hate the idea altogether. Let’s face it, healthcare is an extremely pressured environment, so why would you add research into an already busy day job? The simple truth is that research gives us a way to add to this care magic, helping to ensure care pathways are the best, safest and most appropriate in every situation.

The pace and scale of research stories can make it easy to presume research is something ‘other people’ do, and whilst there are many brilliant professionals and professions within healthcare, nurses have a unique and phenomenally important place in research in at least three key ways:

- Understanding what matters to patients. A person is far more than their illness, and being so integral to day to day care, nurses have a lens not only on patients’ conditions, but how these interweave with concerns about their life, their livelihood, their loved ones and all else. And it is in this mix that the fuller impact of research can be really understood, way beyond clinical outcome measures, and into what it what matters .

- Understanding how to mobilise and implement new knowledge. Even if new research shows promise, the act of implementing it in a pressured healthcare system can be immensely challenging. Nurses are paramount for understanding – amongst many other things – how patients will engage (or not), what can be integrated into care pathways (or can’t), what unintended consequences could be foreseen and what (if any) added pressures new processes will bring for staff. This depth of insight borne from both experience and expertise is vital to mobilising, translating and otherwise ‘converting’ research promise into reality.

- Driving research . Nurses of course also drive research of all shapes and sizes. Numerous journals, such as BMC Nursing and the Journal of Research in Nursing bear testament to the wealth of research insights driven by nurses, and shared widely to inform practice.

Research isn’t owned by any single profession, or defined by any size. Whatever methods, scale or theories we use, research is the act of understanding, and if nurses aren’t at the heart of understanding the patient experience and the healthcare system, I don’t know who is. So when it comes to research:

- Recognise the value you already bring. You are front and centre in care which gives you a perspective on patient and system need that few others have. Ask yourself, what matters?

- Recognise the sheer breadth of research possibilities, and the million questions it hasn’t yet been used to answer. Ask yourself, what needs to be understood?

- Use – or develop – your skills to do research. Connect with researchers, read up, or just get involved. Ask yourself, how can I make my research mark?

Research is important because people are important. If you’re nearer the research-avoidant than the research-lead end of the spectrum, I’d absolutely urge you to get more involved. Whether you shine a light on problems research could address, critically inform the implementation of research, or do the research yourself….

….from this patient and research impact geek…

Comment and Opinion | Open Debate

The views and opinions expressed on this site are solely those of the original authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of BMJ and should not be used to replace medical advice. Please see our full website terms and conditions .

All BMJ blog posts are posted under a CC-BY-NC licence

BMJ Journals

Nursing Research

Nursing research worldwide is committed to rigorous scientific inquiry that provides a significant body of knowledge to advance nursing practice, shape health policy, and impact the health of people in all countries. The vision for nursing research is driven by the profession's mandate to society to optimize the health and well-being of populations (American Nurses Association, 2003; International Council of Nurses, 1999). Nurse researchers bring a holistic perspective to studying individuals, families, and communities involving a biobehavioral, interdisciplinary, and translational approach to science. The priorities for nursing research reflect nursing's commitment to the promotion of health and healthy lifestyles, the advancement of quality and excellence in health care, and the critical importance of basing professional nursing practice on research.

As one of the world leaders in nursing research, it is important to delineate the position of the academic leaders in the U.S. on research advancement and facilitation, as signified by the membership of the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN). In order to enhance the science of the discipline and facilitate nursing research, several factors need to be understood separately and in interaction: the vision and importance of nursing research as a scientific basis for the health of the public; the scope of nursing research; the cultural environment and workforce required for cutting edge and high-impact nursing research; the importance of a research intensive environment for faculty and students; and the challenges and opportunities impacting the research mission of the discipline and profession.

Approved by AACN Membership: October 26, 1998 Revisions Approved by the Membership: March 15, 1999 and March 13, 2006

Masks Strongly Recommended but Not Required in Maryland, Starting Immediately

Due to the downward trend in respiratory viruses in Maryland, masking is no longer required but remains strongly recommended in Johns Hopkins Medicine clinical locations in Maryland. Read more .

- Vaccines

- Masking Guidelines

- Visitor Guidelines

News & Publications

Research benefits from nursing insight.

The Johns Hopkins Clinical Research Network’s nursing collaboration brings clinical nurses into the research realm.

How can novice nurses best learn about the difficulties that older LGBTQ adults face in dealing with the health care system?

Suzanne Dutton, a geriatric advanced practice nurse at Sibley Memorial Hospital, decided to screen Gen Silent , a 2010 documentary that follows six LGBTQ seniors who are trying to decide whether to be open about their sexuality while navigating options in long-term care.

Afterward, according to a 2021 study she published in Nurse Education Today , Dutton found a statistically significant increase in knowledge and inclusive attitudes among the 379 nurses who watched the film.

“If we’re not showing these things — that LGBTQ people had to be closeted and that homosexuality was classified as a pathological disease until 1974 — nurses won’t fully understand their health care challenges and emotional hardships,” Dutton says.

Her study was one of several conducted within the Johns Hopkins Clinical Research Network (JHCRN) nursing research collaboration. The network, founded in 2009, connects physician-scientists and staff members from Johns Hopkins Medicine with community health care systems for multisite clinical research. The nursing portion, started in 2014, engages nurses in research that addresses ways to improve working conditions for nurses as well as outcomes for patients.

“Nursing research is looking at ways to overcome barriers in health care, refine education, promote cultural sensitivity and achieve resilience in nursing,” says Melissa Gerstenhaber, the JHCRN research nurse navigator who started the nursing collaboration. “There are plenty of reasons to study nurses themselves because they’re the ones who are really out there in the grind.”

Along with Johns Hopkins hospitals, partners in the network include Luminis Health, TidalHealth, Reading Hospital, George Mason University and WellSpan. The network offers a triple win: The research benefits from a diverse pool of subjects, the partner hospitals benefit by gaining access to cutting-edge treatments and ideas, and patients benefit by receiving those new treatments at their local hospitals.

In addition to engaging in multisite studies, the research collaboration helps nurses stay abreast of emerging nursing and interdisciplinary research; provides peer review on grant proposals, abstracts and publications; serves as a think tank for future research ideas through sharing possible resources, funding options, journals and conferences; and helps mentor clinical nurses and share best practices to engage them in research. So far, about two dozen nurses have taken part in research throughout the network.

Topics of other published studies from the nursing collaboration include how to engage nurses in research, and burnout and resilience in health care workers (see sidebar).

Dutton’s LGBTQ study won the systemwide award for outstanding research project at the 2021 SHINE Conference (the Johns Hopkins Health System Showcase for Hopkins Inquiry and Nursing Excellence).

Gerstenhaber mentions an upcoming study by Rebecca Wright, an assistant professor and director for diversity, equity and inclusion in the school of nursing, who has received a $10,000 grant from the Dorothy Evans Lyne Fund to study how health care professionals can partner with Puerto Rican and Korean American communities to facilitate culturally sensitive decision-making at the end of life. Additionally, a follow-up looking at the role of mid-level managers in research — led by principal investigator Mary Jo Lombardo, clinical education program manager at Howard County General Hospital — should be published soon.

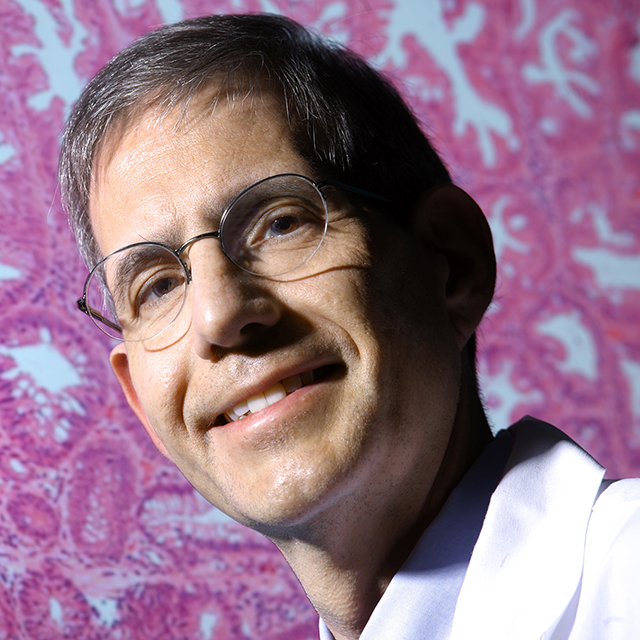

Adrian Dobs , director of the JHCRN and a professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, says the nursing collaboration is an important part of the network. She notes that because nurses are highly involved in caring for patients, they often have more interactions with them than doctors do.

“Nurses see things and hear things that doctors don’t, which affects conditions and diseases,” Dobs says. “Nursing care needs to be studied. We’re excited that we have this opportunity of working with groups of nurses at many medical institutions.”

Nurses interested in learning more can contact Melissa Gerstenhaber at [email protected] .

Related Reading

Alliance expands research potential.

The Johns Hopkins Clinical Research Network connects investigators to patients in other hospitals.

Making Their Voices Heard

Revised nursing governance structure helps bedside nurses at The Johns Hopkins Hospital brainstorm about problems and possible solutions.

- Login / Register

‘This month’s issue highlights innovations in continence care’

STEVE FORD, EDITOR

- You are here: Hospital nurses

How research can improve patient care and nurse wellbeing

07 September, 2020

Research evidence can inform the delivery of nursing practice in ways that not only improve patient care but also protect nurses’ wellbeing. This article, the first in a four-part series, discusses four studies evaluating interventions to support the delivery of compassionate care in acute settings recommended by the findings of the Francis Inquiry report

This article, the first in a four-part series about using research evidence to inform the delivery of nursing care, discusses four studies that were funded following the two Francis inquiries into care failings at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust. Each study evaluated an intervention method in an acute hospital setting that aimed to improve patient care and protect the wellbeing of nursing staff; these included a team-based practice development programme, a relational care training intervention for healthcare assistants, a regular bedside ward round (intentional rounding), and monthly group meetings during which staff discussed the emotional challenges of care. The remaining articles in this series will explore the results of the studies and how they can be applied to nursing care during, and after, the coronavirus pandemic.

Citation: Bridges J et al (2020) Research that supports nursing teams 1: how research can improve patient care and nurse wellbeing. Nursing Times [online]; 116: 10, 23-25.

Authors: Jackie Bridges is professor of older people’s care, University of Southampton; Ruth Harris is professor of health care for older adults, King’s College London; Jill Maben is professor of health services research and nursing, University of Surrey; Antony Arthur is professor of nursing science, University of East Anglia.

- This article is open access and can be freely distributed

- Scroll down to read the article or download a print-friendly PDF here (if the PDF fails to fully download please try again using a different browser)

- Click here to see other articles in this series

Introduction

When asked what would make their working life easier or how they could be better supported to deliver the care to which they aspire, nurses most often say “better staffing”, according to a body of research evidence linking nurse staffing with staff wellbeing, care quality and patient outcomes (Bridges et al, 2019; Aiken et al, 2012). What is not always given much attention by nursing teams and managers is the ‘taken-for-granted’ context in which individual nurses work – the way nursing care is organised, the learning opportunities available to the team and the attention paid to staff wellbeing. It may be possible to change these to support nurses and the care on which they lead and deliver, but opportunities may be missed to think differently about them. The evidence base is growing in this area but does not always reach those nurses who are managing and delivering care.

This is the first in a series of four articles highlighting nursing research findings that can directly inform the management and delivery of nursing care in acute hospital settings. The articles highlight four studies that were funded after publication of Francis’ (2013; 2010) reports on the independent and public inquiries into care failings at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust. However, as this series will argue, the inquiries’ findings have relevance for nursing practice during, and beyond, the coronavirus pandemic, as nursing teams regroup and reset what they do in response to a rapidly changing care environment.

Using research evidence to improve patient care

Change in the complex, adaptive system of healthcare is usually incremental, rather than transformative, and it is unusual for events to lead to a ‘phase transition’, in which radical and transformative change occurs (Braithwaite et al, 2017). Arguably the coronavirus pandemic has stimulated a phase transition in healthcare (and in wider society), disrupting certainties about healthcare and how it should, and can, be delivered. As we move through this system shock, there are opportunities to think about new ways of working; however, it is also important to retain the valuable knowledge gained from other events that have affected the healthcare system.

The lessons learned from the care failings at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust during the late 2000s and the inquiries that followed had an important impact on hospital nursing and the wider system, stimulating reflection, innovation and research to improve nursing care quality. The evidence generated as a result, some of which is explained below, is a reminder of aspects of care that are at risk of being overlooked during the current pandemic. These include the:

- Complexities of caring for older people;

- Importance of nurses’ relational work;

- Importance of nursing care, especially when there is no surgical/medical ‘cure’.

In the absence of a cure for Covid-19, nursing is at the forefront of the supportive care needed by people with the most severe symptoms. As such, it is important to draw on evidence that supports good nursing care and how best to support nurses’ wellbeing, which can be negatively affected by their caring work.

Research studies investigating intervention

The research world responded to the Francis inquiries: the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) funded several studies to inform policy and practice improvements in this area. The research delivered through four such studies (Box 1) – each of which was led by an author of this article – is summarised below.

Box 1. The four studies

Creating Learning Environments for Compassionate Care (CLECC)

This study trialled a pilot intervention focusing on team building and understanding patient experiences. Participants felt it improved their capacity to be compassionate.

Chief investigator: Jackie Bridges

Full study report available here

Older People’s Shoes

This study trialled an interactive programme to help healthcare assistants (HCAs) get to know older people and understand the challenges they face. The programme was well received by participants, especially as HCAs’ training needs are often overlooked.

Chief investigator: Antony Arthur

Intentional Rounding

This study aimed to evaluate how intentional rounding works in diverse ward and hospital settings. Participants expressed concern that rounding oversimplifies nursing, and favoured a transactional and prescriptive approach over relational nursing care.

Chief investigator: Ruth Harris Full study report available here

Schwartz Center Rounds

This study aimed to understand the unique features of Schwartz Rounds, comparing them with 11 similar interventions. Attending rounds increased staff members’ empathy and compassion for colleagues and patients, and improved their psychological health.

Chief investigator: Jill Maben

Study 1: Creating Learning Environments for Compassionate Care

Bridges et al (2018) investigated the feasibility of implementing a team-based practice development programme into acute care hospital settings. Under the Creating Learning Environments for Compassionate Care (CLECC) programme, all registered nurses and healthcare assistants (HCAs) from participating teams attended a study day, with a focus on team building and understanding patient experiences. A senior nurse educator supported the teams to try new ways of working on the ward, including holding regular, supportive discussions on improving care. Each ward manager attended learning groups to develop their compassionate care leadership role, and two team members received additional training in carrying out observations of care and feeding back to colleagues.

The programme was piloted on four wards in two English hospitals, with two control wards continuing with business as usual. Researchers interviewed staff and observed activities related to the project to understand whether these could be easily put into practice and whether changes were needed. They also tested evaluation methods, including ways to measure compassion and ensuring enough older patients could be recruited to a future study.

The study found that the CLECC programme can be made to work with nursing teams on NHS hospital wards and that staff felt it improved their capacity to be compassionate. Researchers also learned they could improve the programme to help staff continue using it, for example, by helping senior nurses to understand their role in supporting staff with this.

Study 2: Older People’s Shoes

Arthur et al (2017) studied the feasibility of a relational care training intervention for HCAs to improve the relational care of older people in acute hospitals. They initially conducted a telephone survey of acute NHS hospitals in England to understand what training HCAs received. They undertook group interviews with older people and individual interviews with HCAs and staff working with them to establish what participants thought should be included in HCA training. Training was highly variable and focused on new, not existing, staff; relational care was not a high priority.

In response to their findings, the study team designed and produced an innovative interactive training programme called Older People’s Shoes, which aimed to encourage HCAs to consider how to get to know older people and understand the challenges they face. A train-the-trainer model was used to allow the intervention to be viable beyond the testing sites. To see whether they could formally test this new training, the team conducted a pilot cluster-randomised trial in 12 wards from three acute hospitals; it concluded that a larger study to examine whether changes in patient outcomes could be observed would be challenging, but possible.

Older People’s Shoes was well received by participants. This was particularly so for the HCAs, whose training needs were often overlooked or restricted to mandatory requirements, where the focus is almost exclusively on safety.

Study 3: Intentional Rounding

Originating in the US, intentional rounding is a timed, planned intervention that aims to address fundamental elements of nursing care through a regular bedside ward round. Harris et al’s (2019) study aimed to explain which aspects of intentional rounding work, for whom and under what circumstances. It aimed to do this by exploring how intentional rounding works when used with different types of patient, by different nurses, in diverse ward and hospital settings, and whether and how these differences influence outcomes. The study methods included:

- An evidence review to create a theory of why intentional rounding may work;

- A national survey of how intentional rounding had been implemented;

- A case study evaluation exploring the perspectives of senior managers, health professionals, patients and carers;

- Observations of intentional rounding being undertaken;

- An analysis of costs.

The national survey found that 97% of NHS trusts had implemented intentional rounding, although with considerable variation: fidelity to the intentional rounding protocol was observed to be low. All nursing staff thought intentional rounding should be tailored to individual patient need and not delivered in a standardised way. Few felt intentional rounding improved either the quality or frequency of their interactions with patients; they perceived the main benefit of intentional rounding to be the documented evidence of care delivery, despite concerns that documentation was not always reliable. Patients and carers valued the relational aspects of communication with staff, but this was rarely linked to intentional rounding. It is suggested these results should feed into a wider conversation and review of intentional rounding.

Study 4: Schwartz Center Rounds

These were developed in the US to support healthcare staff to deliver compassionate care by helping them to reflect on their work. Schwartz Rounds are monthly group meetings, in which staff discuss the emotional, social and ethical challenges of care in a safe environment. The number of organisations hosting Schwartz Rounds has increased markedly over recent years.

Maben et al (2018) conducted a study to evaluate Schwartz Rounds and understand how the system works. The study used mixed methods, including:

- An evidence review to understand the unique features of Schwartz Rounds;

- A comparison with 11 other similar interventions, such as action learning sets;

- A national survey of 48 staff running Schwartz Rounds in 46 organisations, using telephone interviews to discuss how these had been implemented;

- A survey of 500 staff in 10 organisations to examine how Schwartz Rounds affect work engagement and wellbeing;

- A case study evaluation investigating the perspectives of people who shared their stories at Schwartz Rounds (panellists), audience members who listened and contributed, facilitators, and people who did not attend.

The researchers also observed preparation meetings, actual Schwartz Rounds and steering group meetings to determine how the rounds worked, and under which circumstances they worked optimally.

Their survey found psychological health improved in those attending Schwartz Rounds but not in those who did not attend. Participants described Schwartz Rounds as interesting, engaging and supportive. How they were run varied, creating different levels of trust and safety, and who attended varied – frontline staff found attendance difficult.

It was concluded that Schwartz Rounds are a ‘slow intervention’ that increases its impact over time and creates a safe, reflective space for staff to talk together confidentially. In the staff observed, attending Schwartz Rounds increased their empathy and compassion for colleagues and patients, supported them in their work and helped them make changes in practice.

Applying research findings

The findings from the above studies not only tell us about the impact of each of these four interventions, but also highlight the changes required to better support nursing teams to deliver high-quality care. Written by nursing professors, who were the chief investigators on each of these studies, this series will bring together the findings from the four studies to:

- Highlight the impact of care organisation and related learning opportunities on nurses and on care delivery, as well as the need for staff wellbeing interventions to support nurses;

- Signpost to practical, evidence-based ways in which individuals and teams can improve support for nurses and nursing care;

- Pose questions that individuals and teams can ask in the context of the coronavirus pandemic to optimise support for nurses and care.

The series is part of a collaboration funded by the NIHR to bring the findings of the individual studies to a wider audience; more details about the collaboration and the individual projects can be found at go.soton.ac.uk/cn4. This work will culminate in an event, due to be held in spring 2021, to engage a range of stakeholders in considering how nursing policy and practice should respond to the findings. Readers interested in finding out more can register their interest at Bit.ly/NursingTeams.

The series aims to provide evidence to support nursing teams as they work to recover from the coronavirus pandemic, review ways of working to retain the better areas of nursing care that existed before it took hold and, also, to embrace any lessons learned through their experiences during the pandemic.

- Care failings at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust generated the need for evidence about how to improve patient care

- In response to this, four studies have each investigated a different intervention method in acute hospital settings

- The studies’ findings highlight changes that can help nursing teams to deliver high-quality care and protect nurses’ wellbeing

Also in this series

- Learning opportunities that help staff to deliver better care

- Research that supports nursing teams, part 3 of 4

- Nursing interventions that promote team members’ psychological wellbeing

- The four featured studies were funded by NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research programme. The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Health Services and Delivery Research programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Related files

200909-how-research-can-improve-patient-care-and-nurse-wellbeing1.

- Add to Bookmarks

Related articles

Have your say.

Sign in or Register a new account to join the discussion.

Cookies on the NHS England website

We’ve put some small files called cookies on your device to make our site work.

We’d also like to use analytics cookies. These send information about how our site is used to a service called Google Analytics. We use this information to improve our site.

Let us know if this is OK. We’ll use a cookie to save your choice. You can read more about our cookies before you choose.

Change my preferences I'm OK with analytics cookies

Nursing research and evidence underpinning practice, policy and system transformation

Research led by nurses and the contributions they make as members of multidisciplinary research teams can drive change. Evidence from research influences and shapes the nursing profession, and informs and underpins policy, professional decision-making and nursing actions. It is the cornerstone of high-quality, evidence-based nursing.

Making research matter – The Chief Nursing Officer (CNO) for England’s strategic plan for research is for all nurses working in health and social care, whether they are already or thinking about getting involved in research), colleagues in academia and the third sector and all those who support research.

The CNO for England’s strategic plan for research sets out the ambition to “create a people-centred research environment that empowers nurses to lead, participate in and deliver research, where research is fully embedded in practice and professional decision-making, for public benefit”. Fulfilling this ambition will strengthen and expand nurses’ contribution to health and care outcomes through research of global significance. This provides the scientific basis for: the care of people across the lifespan; during illness, through to recovery and at the end of life, preventing illness, protecting health and promoting wellbeing.

Five themes underpin this ambition:

- Aligning nurse-led research with public need – so the portfolios of relevant funders reflect the research priorities of patients, carers, service users, residents, the public and our profession.

- Releasing nurses’ research potential – to create a climate in which nurses are empowered to lead, use, deliver and participate in research as part of their job, and the voice of the profession is valued.

- Building the best research system – so that England is the best place for nurses to lead, deliver and get involved in cutting-edge research.

- Developing future nurse leaders of research – to offer rewarding opportunities and sustainable careers that support growth in the number and diversity of nurse leaders of research .

- Digitally-enabled nurse-led research – to create a digitally-enabled practice environment for nursing that supports research and delivers better outcomes for the public.

The plan builds on existing commitments and priorities set out in the NHS Long Term Plan and closely aligns with the UK Clinical Research Recovery, Resilience and Growth (RRG) Programme , which brings together partners from across the NHS, academia, government, universities, regulators, charities, patients and the public. This alignment means the nursing profession will be able go further in tackling challenges and embedding sustainable, effective and innovative practices that reflect system-wide priorities.

Publication links

- The Chief Nursing Officer (CNO) for England’s strategic plan for research – full version.

- The Chief Nursing Officer (CNO) for England’s strategic plan for research – executive summary .

Implementation plan

We are delivering the strategic plan through close collaboration with colleagues across NHS England and Health Education England (HEE), the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), National Institute of Health and Care Research (NIHR), Council of Deans of Health (CoDH) and Royal College of Nursing (RCN).

Below is a summary of the activities underway in 2022 or planned for 2023 that start turning the plan into reality, organised by the five themes listed above.

Strategic focus 1: Aligning nurse-led research with public need

- Research demand signalling – to identify, prioritise and articulate research questions most pertinent to nursing practice. We are first doing this for mental health building on the research demand signalling of national mental health programme , working with the Deputy Director of Mental Health Nursing and the Innovation, Research and Life Sciences Group (IRLS).

Impact : A clear understanding of the research questions in mental health that the nursing profession is best placed to address. This process will also inform how we adopt it for other areas of nursing.

- Explore how the top 3 evidence uncertainties identified by the Community Nursing James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership should be signalled to academics and funders of research.

Impact: By developing research questions for the top 3 community nursing priorities, funders will know what research is most needed to underpin this field of practice and improve population health and patient care.

- Working with the IRLS and stakeholders, develop an action plan in response to the commissioned report ‘Implementation Strategies in Respect of Addressing Inequalities in Race and Health in the CNO for England’s Strategic Plan for Research’.

Impact: Co-production of this action plan will support development of an inclusive health and care research system for people, communities and the profession.

Strategic focus 2: Releasing nurses’ research potential

- With NIHR help establish a research interest group and develop a research toolkit for clinical matrons, to support their role in enabling research and innovation across nursing teams.

Impact: Giving this group of nursing leaders a suite of resources and network of support will help research become business as usual, increasing nurse engagement in supporting, leading and delivering research.

- Scope what trust and integrated care board (ICB) executive nurse leaders require to make research matter in every nurse’s practice and design a programme of learning and development in response to this.

Impact: By promoting understanding of the benefits of involving nurses in the leadership, delivery and support of research among senior nursing leaders, the voice of the profession will be heard when and where decisions are made about prioritisation, commissioning, management and translation of research.

- Scope systems, processes and approaches that facilitate use of research evidence – the first step of an initiative to encourage transfer and implementation of evidence into nursing practice.

Impact: Strategies to strengthen the transfer and implementation of research evidence by the nursing profession will improve population health and the provision of safe and effective nursing care.

- With the Chief Midwifery Officer (CMidO) research teams, support NIHR to identify features of successful research-related roles for nurses and midwives in community, public health, and social care.

Impact: By identifying what makes these roles succeed in settings outside acute hospitals, interventions can be designed to increase capacity and capability in these settings, diversifying opportunities for participation and engagement in research.

Strategic focus 3: Building the best research system

- Work with the CMidO research teams and IRLS, NIHR Director of Nursing and Midwifery, HEE Chief Nurse, DHSC and RCN to ensure strategic alignment of respective work programmes.

Impact: By co-ordinating activity across England, stay on track to deliver the ambition and communicate a clear and consistent message.

- Clarify roles and responsibilities of regional, integrated care board and trust executive nurse leaders in building nurse-related research capacity and capability, as well as the actions they might take to support implementation of the plan.

Impact: Clarity about duties and responsibilities, supporting sustainable change through system-wide leadership.

- Support delivery of the NIHR Senior Research Leader: Nursing and Midwifery programme by offering regional and national internship opportunities.

Impact: Programme participants will be pivotal in implementing the CNO strategic plan for research, as well as the Future of Clinical Research Delivery 2022-2025 Implementation Plan and Best Research for Best Health: Next Chapter , propagating effective system leadership.

- Ensure strategic co-ordination and harmonisation of work with relevant NHS England deputy directors/heads of nursing (for example but not limited to, community nursing, mental health, children and learning disabilities) and the Chief Nurse for Adult Social Care and Chief Nurse at the Office of Health Improvement and Disparities (both at DHSC).

Impact: Cross-programme connections will ensure efficient and effective plan implementation, provide opportunities to address diverse population health needs and health inequalities, and maximise impact across the different fields of nursing and sectors.

- Supporting delivery of commitments in the NHS Long Term plan and RRG work programme, IRLS are developing research metrics for provider and ICB assurance, aligned to this with CMidO research teams,, explore which metrics and reporting increase the visibility of nurse – led research across the NHS and strengthen incentives for trusts and boards to support nurses’ involvement in leadership and delivery of research.

Impact: A data-based approach will enable sustainable change across the NHS, and by giving leaders insight into performance against the ambitions of the strategic plan for research, is a means of demonstrating the impact of research on patient outcomes and improvements in patient care and population health.

- Commission a tool for organisations to self-assess their readiness and progress towards achieving the ambitions of the strategic plan for research.

Impact: This tool will facilitate planning by establishing a baseline against which an organisation’s progress can be measured.

Strategic focus 4: Developing future nurse leaders of research

- Agree work to overcome challenges limiting growth in number and diversity of nurses wishing to pursue a research-focused career in the NHS, social care and public health settings resulting from discussions at the NIHR/NHS England nursing summit in June 2022.

Impact: By building and securing a sustainable clinical academic and research delivery nursing workforce and making research-related roles more appealing, NHS and social care providers will be equipped to attract and retain the best talent and augment overall system capacity.

- HEE Centre for Advancing Practice, with the CNO and CMidO research teams, will develop a research-related capability framework and career pathway(s) that align with enhanced, advanced and consultant levels of practice.

Impact: Clear career structures and associated roles that align with levels of practice will increase the value and attractiveness of research roles for the health and care professions; more nurses will get involved in research and for some become a major part of their career plans.

- Led by the IRLS, working with CNO and CMidO research teams and lead officers for other registered health professions, explore use of workforce intelligence to inform workforce planning for those involved in research.

Impact: Workforce intelligence data will enable ICBs and trusts to develop workforce plans that reflect the ambition for the nursing workforce to lead, participate in and deliver research as part of providing high quality patient care and the business of every nurse and midwife.

- In collaboration with NIHR, CoDH and other partners, promote growth of ethnic minority nurse research leaders.

Impact: Targeted activities will diversify the profile of research leaders and widen access for nurses aspiring to academic and clinical academic roles.

- With the CMidO research team, collaborate with the NIHR supported Nursing and Midwifery Incubator on initiatives to identify and address barriers to increasing research capacity in nursing and midwifery.

Impact: Attracting, training and supporting future nurse and midwife research leaders of research will complement and maximise other investments to develop a skilled research workforce.

- With the CMidO research team, support NIHR Nursing and Midwifery’s development of flexible career pathways for research nurses: a programme for nurse/midwife principal investigators and better integration of clinical and research roles.

Impact: Flexible career options encourage movement between supporting, delivering and leading research, promoting a culture in which research is the business of every nurse and midwife.

Strategic focus 5: Digitally enabled nurse-led research

- Scoping and discovery work to understand the opportunities and challenges associated with establishing a minimum dataset for nursing (the standardised collection of essential nursing data).

Impact: This element of digital architecture – that is, a nursing minimum dataset – will be the foundation for the standardised collection of essential nursing data to enable analysis and comparison of data across populations, settings, geographical areas and time.

- With the CMidO research team, contribute to the work of the UK Clinical Research RRG programme using data-driven methods and digital tools to transform the way people-centred clinical research studies are designed, managed and delivered.

Impact: Improved nurse-led research study planning, recruitment and follow-up, and access to data, ensuring research is enabled by data and digital tools.

- Collaborate with HEE to deliver the actions the Phillips Ives Nursing & Midwifery Review recommends to ensure nurses and midwives can access the knowledge, skills and education they require for safe, effective digitally-enabled practice.

Impact: Empowers nurses and midwives to practise in and lead a digitally-enabled health and social care system, with practice fully supported by digital technology and data science.

- Establish a digital nursing journal club to build a community of digitally enabled nurse-led practice.

Impact: This community of practice will connect nurse academics with provider chief nursing information officers, to build knowledge and expertise in this growing sphere of nursing.

We will keep you updated on progress and plans by making updates to this page and via the CNO’s Bulletin Nursing and Midwifery Matters .

If you would like to get involved in the CNO’s strategic plan for research, please contact [email protected] .

Why Is Research Important in Nursing?

Research is essential for the advancement of any profession. Healthcare is no different, and research in nursing could revolutionize it. The use of evidence-based practice by nurses ensures better standards of care.

Nursing is a career that requires strong research skills. Why? Patients and caregivers rely on nurses for information so they can make informed decisions about their health care.

Research helps to shape the nursing profession as it evolves with the needs of society and advances in medical science, assisting nurses in providing effective, evidence-based care.

Research is also essential because it is a crucial predictor of nurse retention rates, which is necessary for ensuring access to high-quality nursing care over time.

Five Types of Qualitative Research:

Why does research matter in nursing programs.

The research process is an integral component of the nursing profession. Nurses work together with other healthcare professionals to provide quality care for patients and their families.

Research can be defined as “the systematic investigation into a particular subject or field of knowledge, typically using methods that are empirical or scientific.”

It isn’t easy to think of a time when nurses didn’t use research in their practice. Before hospitals became more specialized, many nurses would have been responsible for carrying out clinical laboratory tests on patient samples themselves.

Today, nurses still rely heavily on the findings from research studies to improve patient outcomes and reduce risk factors associated with illness.

They review these studies at conferences and in journals they subscribe to through professional organizations such as The Organization of Nurse Executives (ONE) and The American Association of Colleges for Nursing.

Nurses still rely heavily on the findings from research studies to improve patient outcomes and reduce risk factors associated with illness.

Nurses are also responsible for informing patients about new developments in their field by keeping up with current trends over time to make informed decisions when treating themselves or asking others for care advice.

Communicating this information is essential because it creates a better understanding between healthcare providers and those who use their services.

Information Literacy and Nursing

Literacy is not the same as information literacy. Literacy is an essential skill, and information literacy can access, evaluate and use this knowledge for personal decision making or in collaboration with others to solve problems.

Information literacy is a life-long learning process and will be required to work with new technologies in the future.

Information literacy should not just be taught for its own sake, but because of what it offers learners when they can search effectively for information from multiple sources on their topic, evaluate this literature according to accepted standards, synthesize findings into coherent arguments or summaries that advance understanding about an issue, develop logical explanations or solutions based on evidence found through online searches and library databases as well as other resources.

Evidence-Based Practice

Consider these four factors when evaluating published research:

Validity: Is the study valid, reliable, and accurate? A study’s validity is an essential factor to consider. A significant percentage of published studies are not good, and some even have sufficient evidence that they’re false.

For example, in 1974, psychologists asked participants about their sexual orientation; this was when homosexuality was still illegal in many states. The researchers found that self-reported gay men were much more likely than heterosexual males to report having sex with over 100 women, a number far higher than any other group surveyed written for themselves or others (Bancroft).

Reliability: Is the result of the measurement consistent? Nursing is an occupation that requires ongoing education. Research informs the decisions made in nursing, and therefore it’s important to have access to research findings. The process of gathering information from various sources provides more diverse knowledge than found if only one source were used exclusively.

Relevance: Are there logical connections between two events, concepts, or tasks? To find this out, you might look up the topic in a research database.

It also helps define which new areas of study deserve attention. Researchers often use data from extensive studies that gather information on many people over long periods ( called cohort studies ) or smaller group-based tests designed to assess a person’s response to something like a drug ( called case-control studies ).

Outcome: What were the researchers’ conclusions? The result of every research is not exact because the researchers have different goals for the study.

The research outcomes are also affected by how well a researcher understands and applies design principles to test their hypotheses, define problems in advance, and collect data efficiently with appropriate methods that control for unwanted variability from external sources like confounding variables.

There are many advantages when doing this, such as avoiding duplicate work, which would increase costs without providing any additional benefits (eHealth Literacy).

Types of Research

The research used in evidence-based practice and practice guidelines is research that has been conducted and analyzed by experts in the field of nursing. Nurses work in clinical research as well as participate in collaborative interdisciplinary studies with other healthcare professionals.

Types of Research are following:

Quantitative research: Data is interpreted with the help of numbers, percentages, and variables.

Qualitative research: The results are based on thoughts, perceptions, and experiences.

Three Types of Quantitative Research:

- The descriptive type of research describes an individual, situation, or group of individuals or their characteristics. Based on observed traits, this kind of research searches for conclusions and connections that can be made.

- The purpose of quasi-experimental research is to determine the cause-and-effect relationships between variables.

- Correlational research examines the relationships between variables but does not reveal a cause-and-effect relationship.

- In ethnography, customs and practices are observed or analyzed to learn how particular cultures understand disease and health.

- In grounded theory, theories are built in response to questions, problems, and observations.

- Interpretations, reactions, and paradigms of interaction, communication, and symbolism are studied in symbolic interactionism. Over time, these factors can affect how people change their health practices.

- Historical research examines topics, cultures, or groups in the past systematically.

- Phenomenology is based on the author’s personal experiences and insights.

Role of Nursing Research in Online Programs

Nurses interested in online health care degrees may find the research aspect is what interests them.

Research has been a significant player in nursing practices for many years now. It continues to be important as discoveries are made about human beings on every level of analysis.

Research also plays an essential role when developing programs that will help people heal more quickly or prevent injury before it happens.

There is no shortage of information available for nurses who want to learn more about their career path into either education or administration through online classes at most universities with nursing programs today.

Conclusion:

For nurses to improve their practice, stay current, and offer better care to patients, they need to conduct research. Nurses who possess information literacy skills can use the information to develop their conclusions more effectively. Nurses need to practice evidence-based practice.

Nurses should be able to understand, evaluate and use research in their careers. These skills are taught in nursing schools to help nurses advance in their careers.

You May Also Like:

- Why Ethics Is Important in Nursing

- Why Is the Nursing Process Important?

- Why Evidence-Based Practice Is Important in Nursing

- How to Become a Nurse Researcher?

About The Author

Brittney wilson, bsn, rn, related posts.

Top 10 Highest Paying States for Nurses

9 Effective Ways For Building Confidence In Nursing

This is Why You Need to Join a Nurses Support Group Online

7 Best Brooks Nursing Shoes

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Start typing and press enter to search

Why should I participate in nursing research?

By Marian Altman, PhD, RN, CNS-BC, CCRN-K Jul 14, 2020

- Orientation

Add to Collection

Added to Collection

When someone mentions research, do some of the following thoughts come to mind? Nursing research is important, but I don’t have time. Nursing research is vital to move the profession forward, but I think it’s boring. Nursing research contributes to the empirical body of knowledge, and the criteria necessary for professional status, but research is too complicated and I don’t really understand it. If so, you are not alone.

Nursing research started with Florence Nightingale. She measured illness and infection rates among wounded soldiers in the Crimean War and used those results to petition the British government to improve conditions.

Think about it…Without research, Flo wouldn’t have been able to convince others that sanitation was important to surviving sepsis. This is one reason that research, especially nursing research, is important. Through research, we demonstrate our contribution to health and wellness, answer questions about our practice and confirm our knowledge. The purpose of nursing research from her time until today is to provide empirical evidence to support nursing practice and help us provide excellent patient care.

Participation Barriers

Personal and environmental barriers to participating in nursing research include the following:

- I’m too busy with work.

- Nursing research is for graduate-prepared nurses.

- There’s too much math and statistics.

- I don’t understand research methodology.

- My organization’s culture doesn’t support clinical nurse research participation.

- I don’t work at a Magnet hospital, so I don’t need to know about research.

- I have other priorities.

- I’m not interested in the research.

- I won’t use nursing research.

Participation Benefits

Here’s how nursing research impacts you, our nursing community and ultimately patients and families:

- Improves nursing activities, interventions or approaches to enhance professional practice

- Addresses current issues such as COVID-19

- Helps improve patient outcomes, reduce the length of stay in hospitals and costs

- Helps improve your quality of life, your work environment and your health

- Shapes health policy and the healthcare model to optimize the health and well-being of all populations, which helps prevent, diagnose and cure diseases

- Improves the health and well-being of people around the world

- Offers possible compensation for your participation

- Ensures nursing practice remains relevant and supportive, and protects our patients.

- The ANA Code of Ethics, Provision 7 , encourages nurses to participate in the advancement of the profession through knowledge development, evaluation and application to practice.

You can support research by participating in a study. Access AACN's webpage, Participate in Research Studies , which lists a variety of nursing research opportunities. Select a study that speaks to you and your values and participate if you can. You can also bookmark this page and check it regularly, as new studies are added frequently. We can help improve nursing practice and the patient experience by participating in nursing research.

Please tell us about the research you are supporting in your unit, your organization or elsewhere.

I've been enrolled in the Covid Symptom Study since March. I think it is pretty reputable as it was sent to me by a longitudinal cancer study I have b ... een enrolled in for several years (initially presented through the hospital where I work) Presently over 4 million people enrolled, but they ask for more people to report to give more data. So far from their data, they have revealed six distinct "types" of Covid-19. They say: "Please help by taking 1 min daily to report how you feel 🙏. You also get an estimate of COVID in your area. Download the app https://covid.joinzoe.com/us COVID Symptom Study - Help slow the spread of COVID-19 Help slow the spread of COVID-19 by self-reporting your symptoms daily, even if you feel well. Join millions of people supporting scientists to fight the virus. Help identify (a) How fast the virus is spreading in your area (b) High-risk areas (c) Who is most at risk, by better understanding symptoms linked to underlying health conditions. covid.joinzoe.com" Read More

Are you sure you want to delete this Comment?

- Alzheimer's disease & dementia

- Arthritis & Rheumatism

- Attention deficit disorders

- Autism spectrum disorders

- Biomedical technology

- Diseases, Conditions, Syndromes

- Endocrinology & Metabolism

- Gastroenterology

- Gerontology & Geriatrics

- Health informatics

- Inflammatory disorders

- Medical economics

- Medical research

- Medications

- Neuroscience

- Obstetrics & gynaecology

- Oncology & Cancer

- Ophthalmology

- Overweight & Obesity

- Parkinson's & Movement disorders

- Psychology & Psychiatry

- Radiology & Imaging

- Sleep disorders

- Sports medicine & Kinesiology

- Vaccination

- Breast cancer

- Cardiovascular disease

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Colon cancer

- Coronary artery disease

- Heart attack

- Heart disease

- High blood pressure

- Kidney disease

- Lung cancer

- Multiple sclerosis

- Myocardial infarction

- Ovarian cancer

- Post traumatic stress disorder

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Schizophrenia

- Skin cancer

- Type 2 diabetes

- Full List »

share this!

April 29, 2024

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies . Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

Researchers suggest expanding health equity by including nursing home residents in clinical trials

by Regenstrief Institute

Clinical trials are constantly being designed and study participants enrolled to determine if medical treatments and therapies are safe and effective. Much has been written about the importance of including diverse populations in these trials.

However, the nearly 1.4 million individuals who live in the 15,600 nursing homes across the U.S. have been largely left out of clinical trials , despite the prevalence of such common conditions as hypertension, depression, diabetes and Alzheimer's disease in this population.

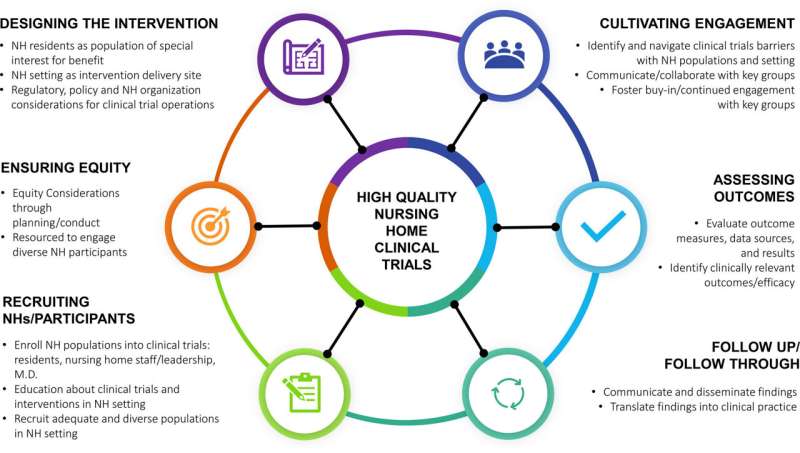

A commentary by faculty of Regenstrief Institute, Indiana University, UCLA and the universities of North Carolina, Colorado and Massachusetts, published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (JAGS) , focuses on the importance of including nursing home residents, a population with significant medical complexity, in clinical trials.

The essay highlights the benefits and challenges of conducting research on medical therapies in nursing homes. The authors identify key elements for successful nursing home clinical trials and propose a nursing home clinical trials network, noting that ensuring diversity, equity and inclusion in any trial design is imperative.

"Among the questions we want to ask are: Is this therapy appropriate for a nursing home population? Does it work in a nursing home population but are there issues around implementation? Are there challenges to delivering it in a nursing home setting?" notes corresponding author Kathleen Unroe, M.D., MHA, M.S., a Regenstrief Institute and IU School of Medicine researcher-clinician.

"Nursing homes were not built to facilitate research. We as researchers need to fit in. We need to appreciate the realities of providing clinical care in this setting and adjust and adapt our protocols to work within that system."

Among the topics discussed in the commentary:

- The need for clinical trials in nursing homes

- Gaps that can be filled with these clinical trials

- Challenges conducting these clinical trials

- Next steps in conducting clinical trials in nursing homes

- A framework for making a nursing home clinical trials network a reality

"It is imperative that we build the science of nursing home care around testing, prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. It is a unique setting that merits more focus given the essential role it plays in the continuum of care for seriously ill adults," said commentary co-author Susan Hickman, Ph.D., director of Regenstrief Institute's Center for Aging Research and a faculty member of IU schools of nursing and medicine.

Citing a missed opportunity, the authors write, "Inclusion of nursing home residents in COVID-19 therapeutics trials might have identified specific issues relating to dosing, administration and monitoring, spurred creation of training materials specifically for nursing home staff, and promoted the development of consistent policies to identify appropriate candidates and deliver treatments promptly, safely, and optimally."

Dr. Unroe adds, "Nursing home residents should have access to evidence-based therapies. When we choose not to do the hard work to test them in the nursing home setting, we are setting ourselves up for a much more difficult implementation."

She notes that "Conducting trials in the nursing home may generate generalizable knowledge that also would be highly relevant to people who are cared for in assisted living facilities or even the broader geriatric population living at home."

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Repurposed cancer drug could treat diabetes by nudging pancreatic acinar cells to produce insulin

7 hours ago

Brain activity related to craving and heavy drinking differs across sexes, study reveals

8 hours ago

Biomolecular atlas for bone marrow offers unprecedented window into blood production

Nerves prompt muscle to release factors that boost brain health, study finds

Online patient portal usage increasing, study shows

10 hours ago

Using advanced genetic techniques, scientists create mice with traits of Tourette disorder

11 hours ago

Study shows rising child mortality in the US has the most impact on Black and Native American youth

Massive study identifies new biomarkers for renal cancer subtypes, improving diagnosis and—eventually—treatment

Improved nutrition, sanitation linked to beneficial changes in child stress and epigenetic programming

Study uncovers at least one cause of roadblocks to cancer immunotherapy

Related stories.

Improving dementia care in nursing homes: Learning from the pandemic years

Apr 10, 2024

Making transitions from nursing home to hospital safer during COVID-19 outbreak

Apr 28, 2020

Specialized nursing facility clinicians found to improve end-of-life care

Mar 15, 2024

Novel nurse-driven virtual care model supports nursing home residents and nurses who care for them

Jun 20, 2023

Looking beyond the numbers to see pandemic's effect on nursing home residents

Jul 14, 2021

New app to bridge information gap between hospitals, nursing homes and offer better care for patients

Dec 14, 2023

Recommended for you

Study finds that the transport of mRNAs into axons along with lysosomal vesicles prevents axon degeneration

14 hours ago

Researchers discover compounds produced by gut bacteria that can treat inflammation