Inquiry-Based Music Theory an open, interactive, online textbook for college music theory

CC BY-SA 2017.

Inquiry-Based Music Theory OER Text Book

Chapter 10) An Introduction to Part-writing ❮ Overview 10b - Part-writing Errors | Lesson 10b - Part-writing Errors ❯

Examples 10b - Part-writing Errors

Parallel perfect fifths and perfect octaves (pp5, pp8).

Part-writing errors result from poor voice-leading. For example, look at the progression below and try to find our first major error: parallel octaves . Once you have found it, look to see if a voicing rule has been broken. If the voicing error is not fixed, is there any way to avoid the parallel octaves without incorrectly resolving a tendency tone?

Parallel octaves and fifths undermine the independence of lines, so you should always avoid them in this style. Listen to the following example, and try to locate the parallel perfect fifths aurally before you look through the parts.

Once you have identified the voice that contains the PP5s, try singing the upper of the two voices, and then listen to the example again. Do you have a difficult time differentiating the upper voice from the lower of these two voices?

Contrary perfect fifths and octaves (CP5, CP8)

Our next part-writing error, contrary perfect fifths and perfect octaves are simply an attempt to cover up parallel perfect fifths and perfect octaves by displacing one voice by an octave. The next two examples attempt to fix the errors from the first two examples on this page by displacing one voice of the parallel perfect intervals. Identify these by comparing them to the previous example (i.e. P) Notice that it creates multiple voicing and spacing errors as well as nearly unsingable parts!

Unacceptable unequal fifths (UU5)

The last two common part-writing errors have specific clauses tied to them that specify which voices are acceptable and unacceptable. The first, unacceptable unequal fifths , must occur between the bass voice and one of the upper voices. In the following example, find the unacceptable unequal fifths where a d5 moves to a P5. What is wrong with the voice-leading here?

Note that we will consider a P5 moving to a d5 as acceptable unequal fifths, because a P5 to a d5 does not require incorrect resolutions of tendency tones. There are some stricter versions of chorale part-writing that do not allow any form of unequal fifths.

Unacceptable similar fifths or octaves (US5, US8)

The final common part-writing has many names, but we will use the term unacceptable similar fifths or octaves . This error can also be called “direct”, “hidden”, or “exposed”. I prefer to use similar because it implies the motion like the other categories, but I also think that exposed does a fine job describing the effect. (I dislike the term hidden because students often confuse this with contrary fifths (or octaves), because the goal of contrary fifths is to “hide” parallel fifths.) Unacceptable similar fifths or octaves have the most restrictions. The conditions are:

- They can only occur between the soprano and the bass voices.

- They require a skip of a third or more in the soprano voice.

- The two voices must move in similar (not parallel) motion.

- The second interval must be a P5 or P8.

If any one of these conditions are not met, then there is not a part-writing error. Look at the following example to find an example of similar octaves . Once you have found it, look at the voice-leading around it. What does it do to spacing? Does it create more errors? Unacceptable similar octaves and fifths also often create melodies that imply different harmonies. To demonstrate, sing the melody alone. Do you hear it as C major or a different key?

As a final demonstration of the difficulties that these part-writing errors create, try to fix each of the part-writing errors on this page. What do you have to change? Do you get to keep the harmony? Voice-leading? Voicing? In trying to fix it, do you just create further errors?

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Unit 1: Harmonic Error Detection

Learning Objectives

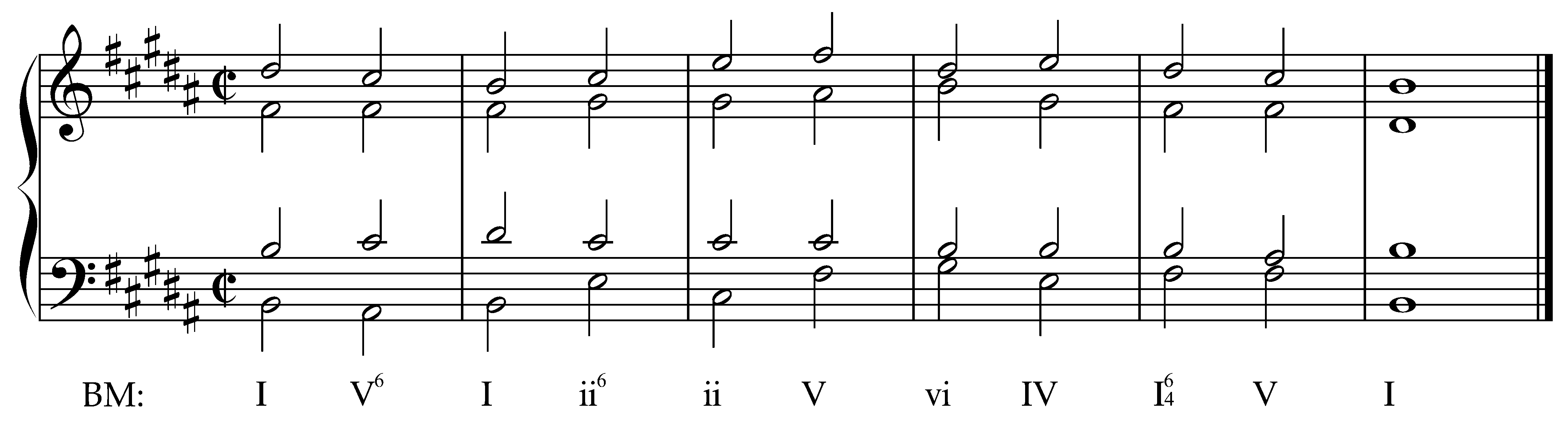

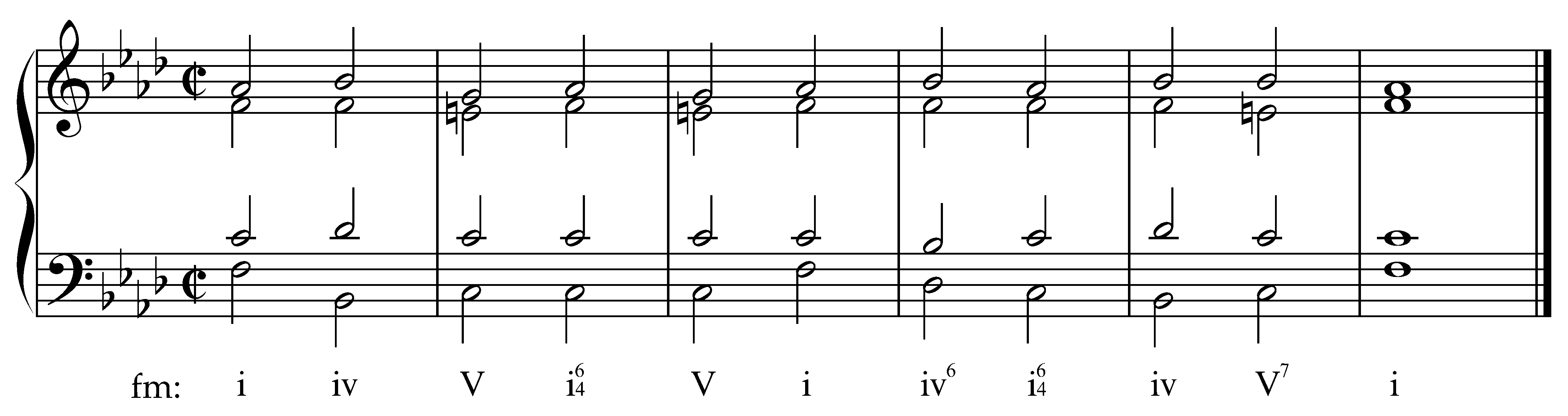

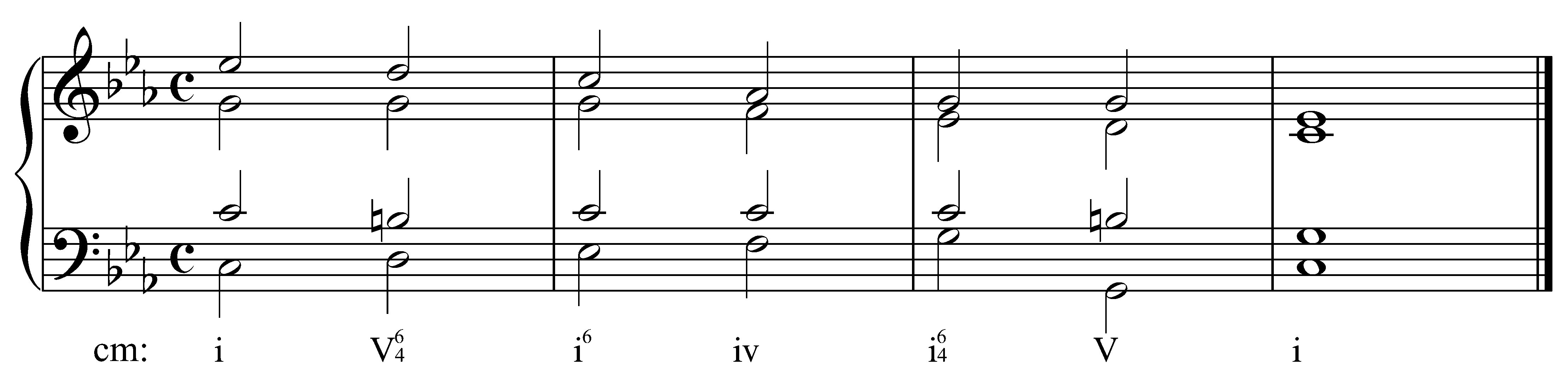

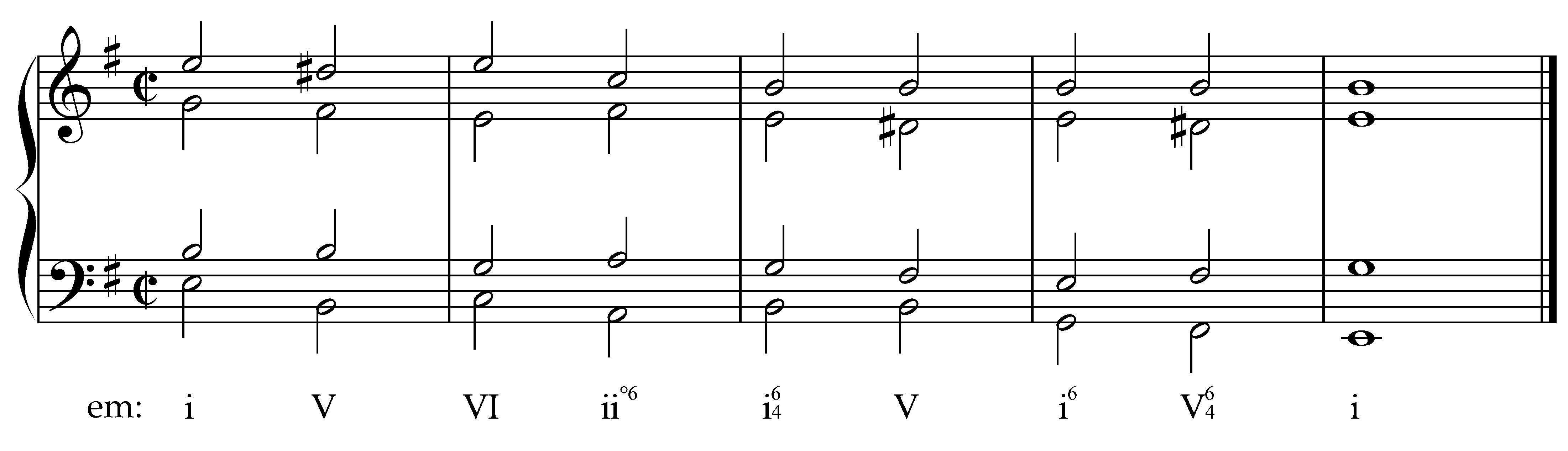

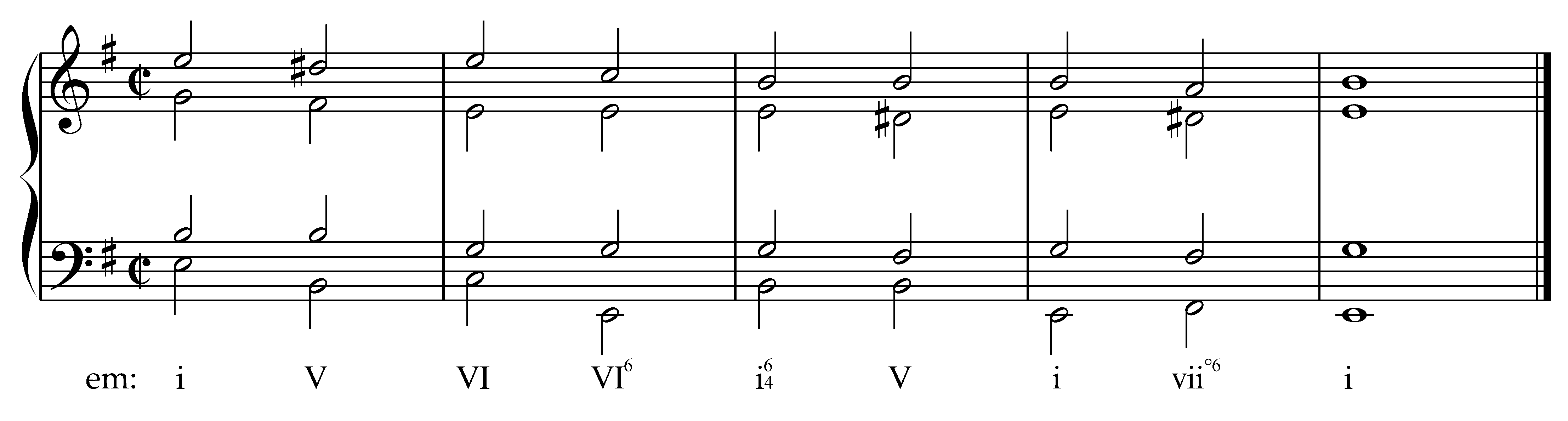

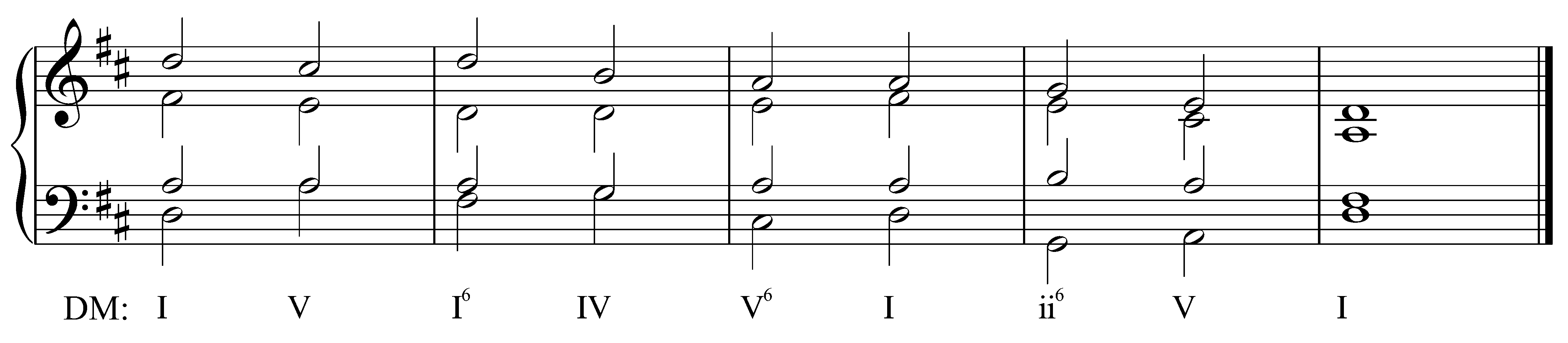

In this unit, our harmonic error detection work will focus on examples that include second inversion triads (and the occasional V 7 chord).

Instructions

The written score provided below may differ from the recording in one or more ways. For anything that is played differently than the notated version: 1) circle it and 2) write in what was played instead of the notated version. Note: differences may be in any of the four voices and in the Roman numeral analysis; you should circle and make changes to any pitches and any Roman numerals that are affected by errors.

https://openbooks.library.baylor.edu/app/uploads/sites/3/2022/07/1102_U1_harmED_hw_B_hear_audio.mp3

https://openbooks.library.baylor.edu/app/uploads/sites/3/2022/07/1102_U1_harmED_hw_C_hear_audio.mp3

https://openbooks.library.baylor.edu/app/uploads/sites/3/2022/07/1102_U1_harmED_hw_D_hear_audio.mp3

https://openbooks.library.baylor.edu/app/uploads/sites/3/2022/07/1102_U1_harmED_ex_A_hear_audio.mp3

https://openbooks.library.baylor.edu/app/uploads/sites/3/2022/07/1102_U1_harmED_ex_B_hear_audio.mp3

Musicianship 2 Copyright © by Amy Fleming; Edward Taylor; and Horace Maxile. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Guide to SATB part-writing

The idea of studying by creating is one that has been central to tonal Western art music for centuries. For as long as the tradition has existed, composers, performers, critics, and even casual enthusiasts have engaged in compositional exercises as a means of deepening understanding and appreciation. Although there are many valid ways to approach the study of this music, we feel that creating it oneself, following guidelines derived from observing compositional practice, is one of the most immersive and exciting paths.

Many of the exercises in this book will ask you to write or complete chord progressions of various lengths in four voices. This type of activity is particularly well suited to the study of tonal Western art music because it strikes a balance between the melodic and harmonic aspects of polyphonic music. When completing such an exercise, you must consider the musicality and independence of four individual voices or parts (hence “part-writing”)—one soprano, one alto, one tenor, and one bass (hence “SATB”). But you must also consider how the voices combine to form harmonic sonorities and how the music shifts from each sonority to the next.

This type of writing has a lot of moving parts, so to speak, and you must track all of them to be successful in completing these exercises. Keeping track of so many things can, naturally, be a bit overwhelming at first. So, our approach here is to introduce elements of the practice gradually. Many exercises will ask you to write just one or two chords, focusing on specific techniques or aspects of the part-writing process. In these cases, there is often just one or two solutions that adhere to constraints dictated by the tradition. Other exercises are more open-ended, giving you a greater degree of flexibility—and thereby offering more opportunity for creativity—in how you realize a given progression. For these lengthier exercises, the following guide to part-writing practice and proofreading will be invaluable and should be frequently consulted.

Historically, part-writing exercises are based in large part on the compositional practices of Johann Sebastian Bach, specifically in the 400 or so SATB chorale harmonizations he wrote in the 18th century. Countless other pieces by other composers share many of the characteristics found in these works and so, despite Bach’s unusually prominent reputation, we may view these exercises as representative of a much larger tradition. Within this body of work, however, one finds as much variety as commonality and so it would be impossible for a guide such as this to capture every aspect of compositional style in tonal Western art music.

We encourage you, then, to think of this guide not as a set of rules—or, worse, laws—that govern how all tonal music works or should work. It is better understood as a window into a particular mode of thinking about and creating one style of music. The guidelines described here are far more strict than one actually encounters in historical compositions. Bach himself, for example, occasionally wrote parallel fifths in his part-writing—the afterword of Fundamentals, Function, and Form describes one such case—and countless other composers took an even looser approach. The idea here is to narrow your focus on specific aspects of musical composition. Remember as you compose your own music or study the music of others that, more often than not, art does not confine itself to any rigid set of constraints.

General characteristics and guidelines

When completing a part-writing exercise, one must pay attention to many different things. The shape of each individual melody, the way the melodies interact, and the structure of the chords that result from the combination of voices all require careful planning. With so many things vying for your attention, part-writing exercises can feel a bit like juggling! The following sections of this guide break down the general characteristics and guidelines for each of these considerations.

Melodic considerations

The melody found in each individual part—soprano, alto, tenor, and bass—of a part-writing exercise should be singable. These exercises are, after all, rooted in vocal music. It is highly recommended that you sing each voice out loud, both while working on the exercise and especially when you have finished. If a melody is overly difficult to sing or even has just one or two small problem spots, you should consider revising.

Melodies should be mostly conjunct—that is, consisting primarily of stepwise motion. Held notes—pitches that are sustained through one or more chords—are very easy to sing and are therefore very desirable in this style. Intervals larger than a minor or major second are perfectly acceptable, of course, provided the melody does not become too jumpy. In general, it is considered good practice to balance out larger leaps—leaps greater than a third—with stepwise motion in the opposite direction.

Some intervals should be avoided entirely. Tritones, sevenths, and intervals larger than an octave are difficult to sing and tend to stand out, making the overall combination of voices sound unbalanced. Diminished and augmented intervals—such as the augmented second between scale degree [latex]\hat6[/latex] and the raised leading tone in a minor key—should also be avoided.

One should also be mindful of tendency tones. As the following example illustrates, certain scale degrees have a tendency to resolve by step in predictable directions:

Scale degrees [latex]\hat2[/latex] , [latex]\hat4[/latex] , and [latex]\hat6[/latex] tend to resolve down by step to [latex]\hat1[/latex] , [latex]\hat3[/latex] , and [latex]\hat5[/latex] , respectively. This is not to suggest that these scale degrees must resolve in the prescribed fashion. Rather, you should be aware that resolving a tendency tone will have one effect and avoiding the expected resolution will have another.

There are two types of tendency tones which should be resolved in a predictable way. Scale degree [latex]\hat7[/latex] , the leading tone, has an even stronger tendency to resolve up to [latex]\hat1[/latex] . When the leading tone appears in a dominant chord— V (7) or vii o (7) —it almost always resolves by step up to the tonic. Occasionally it will leap down to scale degree [latex]\hat5[/latex] instead, but this should be restricted to cases where it appears in an inner voice (the alto or tenor). The other type of tendency tone that should be resolved consistently is not a scale degree but a chord member. Chordal sevenths, notes that form a dissonant seventh above a root (or a dissonant second if the chord is inverted), should always resolve down by step.

Rhythmically, part-writing exercises tend to be very clear and simple. For the most part, all voices follow the same rhythm and the duration of each note tends to be equal to—or longer than—the duration of a single beat in the meter.

Counterpoint restrictions

As much as you must consider the musicality of each melodic line in a polyphonic exercise, you must also consider the counterpoint resulting from how each voice interacts with each other voice. An abundance of contrary motion between voices will help project a sense of independence between the four parts, but you should strive for a variety of motion types by including parallel, direct, and oblique interval progressions as well.

The use of standard interval progressions should be your primary concern here. The majority of interactions between voices in a part-writing exercise should be comprised of standard interval progressions. (See Chapter 12 and Appendix A of Fundamentals, Function, and Form for detailed descriptions of standard interval progressions.)

Of course, other interval progressions are found in this style of music as well and may include what we refer to as “resultant intervals” in Chapter 14 of Fundamentals, Function, and Form . Unlike the intervals used in standard interval progressions, resultant intervals may include dissonances. They arise when two voices separately form standard progressions with some third voice but not with each other, and therefore appear only in textures with three or more voices.

Some interval progressions, on the other hand, are strictly avoided in this style of music: parallel unisons, parallel fifths, and parallel octaves:

Pitches forming unisons, fifths, and octaves blend together so well it can become difficult to distinguish between the two voices. When two or more of these intervals are used with parallel motion, the effect is more like a single, strengthened melody than two unique voices. Standing out in the texture in this way, parallel unisons, fifths, and octaves undermine the independence of the voices and should therefore be considered impermissible.

Parallel motion from one fifth to another is considered acceptable in this style, however, when the second fifth is diminished:

The reverse progression—a diminished fifth leading to a perfect fifth—is typically avoided. (See Example 17-7 in Chapter 17 of Fundamentals, Function, and Form for further discussion.)

Note that guidelines concerning forbidden interval progressions may vary. Many instructors, for example, may advise you to avoid consecutive fifths by contrary motion since such progressions are effectively equivalent to parallel fifths with an octave displacement:

Some instructors advise their students to avoid direct motion to a perfect fifth or octave. This type of progression is sometimes referred to as “hidden fifths” or “hidden octaves” because in historical performance practice a singer might embellish their part by adding passing tones to fill in a melodic leap, thereby creating a parallel interval progression:

Generally speaking, direct motion to a perfect fifth or octave is acceptable when it involves either of the inner voices. When it involves both outer voices, it is best if the soprano moves by step. Students working with an instructor should seek clarification on which progressions to avoid.

Keeping track of the contrapuntal relationship between two voices is hard enough, but in an SATB setting there is a lot more happening. With four voices, there are six unique voice pairs: 1) soprano against alto, 2) soprano against tenor, 3) soprano against bass, 4) alto against tenor, 5) alto against bass, and 6) tenor against bass. When completing a part-writing exercise, it is important that you be mindful of each of the six pairs of voices.

Chord spelling

At its core, a part-writing exercise is a four-part realization of a chord progression. The notes that appear among the four voices, in other words, are determined by a given series of Roman numerals or other chord symbols. To spell a chord, you must determine the letter name (e.g., F or E b ) of each chord member. Familiarity with different chord types, then, is a necessary prerequisite.

The key of a particular exercise is indicated by the key signature as well as in letter-based shorthand below. You can recognize the key name at the beginning by the colon (“:”) which appears after the letter or accidental. Uppercase letters represent major keys and lowercase letters represent minor keys. The shorthand “G:” stands for “G major:” while “f # :” stands for “F-sharp minor:” and so on. Note that some exercises modulate, changing keys one or more times before they reach the end. This is represented by an asymmetrical bracket with a new key name and Roman numerals written on a lower level:

In most cases, the Roman numeral represents the scale degree of the chord root in the key at hand. In G major, for example, a IV chord will have C as its root since C is scale degree [latex]\hat4[/latex] in that key. The quality of the chord is indicated by the case of the Roman numeral as well as any additional symbols appearing to the left or right. (See Chapter 13 of Fundamentals, Function, and Form for review with Roman numeral representations of triads and Chapter 18 for the same with seventh chords.)

Pay careful attention to the quality of each chord, particularly in minor keys. One of the most common errors students make in chord spelling is forgetting to raise scale degree [latex]\hat7[/latex] in minor-key dominant chords. In the following example, a V 7 chord in G minor must have F # instead of F § to match the case of the Roman numeral:

Chord position—the indication of which chord member appears in the lowest voice—is indicated by bass figures. These stacked Arabic numerals are written to the right of the Roman numeral. The tables below summarize the common figured bass representations of triads and seventh chords in various positions:

It is often wise to start by writing out the bass line since that part is restricted by the provided progression.

Chord doubling

A triad consists of a root, a third, and a fifth. In part-writing exercises, the various notes of each chord are performed by the soprano, alto, tenor, and bass. This raises a question that must be answered time and time again when realizing a chord progression: How should one distribute the three notes of a triad among the four voices of the exercise? The matter of deciding which chord member should appear in two (or more) voices is referred to as chord doubling.

The preferred doubling in a triad is generally determined by the position of the chord. Since the soprano, alto, and tenor tend to work together as a unit against the bass, it is desirable to have all three chord members represented in the upper voices. In other words, doubling whichever chord member appears in the bass is often a good idea. First-inversion chords, however, offer a bit more flexibility. When the third of a chord appears in the bass, any of the chord members may be doubled. The following table summarizes:

There are several additional restrictions to keep in mind as well. The leading tone should never be doubled, regardless of where it appears in the chord. It has such a strong tendency to resolve to the tonic that a pair of leading tones suggests parallel octaves even if they resolve to different scale degrees. A V (7) chord, then, should never have a doubled third and a vii o (7) should never have a doubled root. Chromatic chords like augmented sixth sonorities also have strong tendency tones which should not be doubled. (See Section III of Fundamentals, Function, and Form for guidance on voicing and resolving various types of chromatic harmony.)

Occasionally, a chord member will be tripled. In the resolution of V 7 , for example, it is common for the tonic resolution to have three roots, one third, and no fifth. (See Chapter 19 of Fundamentals, Function, and Form .) In other cases, a chord may have two roots, two thirds, and no fifth. This is sometimes found when a chord shifts positions (e.g., I moving to I 6 ). The fifth is generally considered the least essential member and for this reason is sometimes omitted.

Seventh chords have four chord members: the root, third, fifth, and seventh. This works out nicely in a four-voice setting since each voice can be assigned a different chord member. To avoid voice-leading errors, a seventh chord may occasionally be written without its fifth. As with triads, the root is generally doubled in these cases. Note that since chordal sevenths have such a strong tendency to resolve down by step, they should never be doubled since, like a doubled leading tone, it would imply parallel octaves.

Chord voicing

The way the individual notes in a chord are distributed among the voices and laid out on the staff is called “chord voicing.” The part-writing exercises in this book consist of four voices: soprano, alto, tenor, and bass. To save space, all four parts are traditionally written on a grand staff. The soprano and alto occupy the upper (treble) staff while the tenor and bass share the lower (bass) staff. Stem directions are used to indicate which notes belong to which voice:

Each of these voice types has a standard range of about one and a half octaves. Soprano notes range from C4 to A5, alto notes from F3 to D5, tenor notes from C3 to A4, and bass notes from F2 to E4:

These ranges are, of course, approximate. Different singers have different ranges. Some sopranos, for example, can sing up to C6 or even higher! Nonetheless, for part-writing exercises you should restrict each of your notes in the four parts to their respective standard ranges.

In addition to making sure that each voice stays within its respective range, you should also ensure that the four parts remain in the same vertical order: soprano above alto, alto above tenor, and tenor above bass. When chord voicings do not follow the typical ordering of voices—soprano above alto, alto above tenor, and tenor above bass—it is known as a “voice crossing.”

Voice crossings are found in this style from time to time, but only rarely and usually to avoid a more glaring problem. Note that voice crossings are generally easy to track between the soprano and alto or tenor and bass, since these voice pairs share a staff. They can be harder to notice between the alto and tenor, however, since these voices are written on separate staves:

You should also be mindful of the intervals found between the voices in each chord. When considering the spacing of a chord, it is helpful to think of the upper voices—the soprano, alto, and tenor—as forming a unit separate from the bass. Neighboring upper voices are rarely more than an octave apart. Again, careful attention is required to avoid spacing errors between the alto and tenor.

Unlike the spacing of the upper voices, the tenor and bass are often more than an octave apart since the bass note is determined by the position of the chord.

Basic part-writing strategy

This book includes several different types of part-writing exercises (see below), but they are all variations on the same basic activity. We recommend taking the following steps to convert an abstract series of chord symbols into a fully-realized four-voice progression.

Collect your materials: Part-writing exercises often involve a bit of trial and error. Having a few sheets of staff paper handy will be very helpful. Use a sharp pencil with a good eraser. Be prepared to identify and correct mistakes.

Spell each chord: Determine the letter names of each member of each chord in the progression. You may find it helpful to work with an extra sheet of staff paper, writing the chords in simple form first before voicing them in four parts. Write the key name and signature under a single staff as well as the provided Roman numerals. Write each chord in a simple, visually intuitive format. Do not worry about voice-leading yet. This sheet will simply serve as a reference later on, a catalog of notes to be included in each chord. Here is an example for the progression i – i 6 – ii ø 6 / 5 – V – i in C minor:

Write the bass line: Since bass notes are pre-determined by the Roman numerals, write the bass part first. Keep within the standard range for a bass voice and follow the melodic considerations described above as closely as possible, but remember that bass lines are often more disjunct than the other parts. Here is one possible bass line for the progression shown above:

Add the upper voices: After writing out the bass line, you could complete each of the upper voices, one after another, but we recommend working on all three upper voices simultaneously. Work carefully, chord by chord, from beginning to end. Follow the guidelines listed above and check for errors as you go. It is much easier to fix problems when they appear than to go back and make corrections later on. Here is a full realization of the progression shown above:

Proofread: Checking for errors is an essential part of the process. Plan on setting aside plenty of time for proofreading, especially if you are new to this type of exercise. Use the proofreading checklists below to help ensure that your work is problem-free in every regard. Address any issues by rewriting the chord(s) in question and note that fixing a problem often requires rewriting everything from that point until the end—or at least rearranging the voices. Once you finish with any changes, proofread the whole progression once again.

Detailed directions

Although the different types of part-writing exercises contained in this book are all variations on the same basic idea, each provides you with different preliminary information and each has its own idiosyncrasies. Below, you will find detailed directions and strategies for each of the three types: figured bass realization, Roman numeral realization, and melody harmonization.

Figured bass realization

In this type of exercise, you need only complete the soprano, alto, and tenor parts since a fully realized bassline is provided. Below the given bass line, you will see a series of Arabic numerals and accidentals. These symbols, combined with the corresponding bass note, provide all the information needed to determine the chords to be used at any given moment. The first step, then, is to convert the figured bass line to Roman numerals. Here is a quick guide (see Chapter 21 of Fundamentals, Function, and Form for a more detailed explanation):

- Arabic numerals under a bass note indicate the position of the chord according to the tables shown above. A bass note with 6 / 5 , for example, is the third of a seventh chord in first inversion.

- A bass note with no accompanying Arabic numerals is the root of a triad.

- A numeral with an accidental (e.g., [latex]\hat6[/latex] # or b [latex]\hat3[/latex] ) indicates that the voice forming that interval above the bass should be raised or lowered accordingly. (Note that in some cases raising or lowering a voice may cancel out part of the key signature. In these cases, the accidental in the figured bass may not match the corresponding accidental on the staff.)

- A numeral with a slash through it indicates that the voice forming that interval above the bass should be raised one semitone with an accidental.

- An accidental with no numeral attached alters the voice that forms a third above the bass.

The following example shows realizations of several figured bass notes as well as their corresponding Roman numerals:

To complete a figured bass exercise, first find and write out the corresponding Roman numerals for each chord. Then, follow the basic part-writing strategy described above, starting at Step 4.

Because the bass line is already set, figured-bass exercises are the most restrictive type of part-writing activity included in this book since one part is locked in and cannot be changed to avoid voice-leading problems. But, for the most part, this also makes figured-bass exercises the easiest type of part-writing. More restrictions make for fewer decisions and fewer decisions mean less risk of errors. The biggest difference between this type of exercise and those described below is the added task of converting the figured bass line into Roman numerals.

Roman numeral realization

In this type of exercise, you are provided with a key, a starting chord, and a series of Roman numerals. Here you will need to realize all four voice parts. To complete a Roman numeral realization, follow the basic part-writing strategy described above.

Melody harmonization

Compared to figured bass or Roman numeral realization activities, this type of exercise is much more open-ended. Here you are presented with just a soprano melody and you will need to determine how you want to harmonize it. The chords used to harmonize each note must be selected carefully, keeping in mind the common chord progressions found in this style of music.

Take the following melody, for example:

We recommend following these steps to harmonize it:

Consider the key: Write the scale degree of each melody in the key at hand. This will help you identify potential chords in the next step. This melody is in C major, so the G at the beginning is labeled [latex]\hat5[/latex] . The next note, B, is the leading and is labeled [latex]\hat7[/latex] . We continue in this manner until every note is labeled:

Consider the possibilities: Write out the Roman numerals for every chord that may be used to harmonize each note in the melody. Each soprano pitch can act as the root, third, fifth, or even seventh of a chord. Note that some possibilities will make more sense than others. Regardless, don’t worry about picking chords just yet. For now, simply catalog the full list of possibilities for each note. In this case the first note is a G which, in C major, may serve as the root of a V chord, the third of a iii chord, the fifth of a I chord, or the seventh of a vi 7 chord:

Plan the beginning: Since most phrases begin with a tonic, you will likely want to start your harmonization on a I chord. Since this melody starts with scale degree [latex]\hat5[/latex] , we will begin with a tonic triad:

Plan the ending: Determine the type of cadence you would like to have at the end of your phrase. Depending on the melody, this will most likely be a half or authentic cadence. Consider, too, the lead-up to the cadential dominant. Is it possible to include a cadential 6 / 4 or a pre-dominant chord in the cadence? In this case, the melody will allow for a pre-dominant ii chord as well as an authentic cadence with a cadential 6 / 4 :

Plot a course through the middle: Consider the various types of progressions one commonly encounters in this style of music. Does this progression have a place for a passing 6 / 4 chord? How can you prolong the tonic at the beginning of the phrase? The diagram shown in Example 24-22 in Chapter 24 of Fundamentals, Function, and Form is a useful tool for plotting idiomatic chord progressions. ( Hint: You can also use the progressions provided in other exercises as models.) In this case, we can prolong the initial tonic with a deceptive gesture on beats two and three of the first measure:

Write out the bass line: Once you have settled on a sequence of chords, write in the bass melody. Keep an eye out for any counterpoint errors such as parallel fifths or octaves. In some cases, forbidden parallels can be avoided by inverting one or both of the chords. In other cases, you may need to select a new chord altogether. Here is a bass line to go along with our melody:

Fill in the alto and tenor parts: Follow the voice-leading conventions described above as closely as possible while you add the inner voices. Here is our finished progression, now with inner voices:

Proofread: As always, check for errors as you go and when you are done. Make the necessary changes and proofread one more time.

Proofreading part-writing

As we have indicated in the preceding sections, proofreading is essential to good part-writing. Checking for voice-leading errors will immeasurably enhance your ability to write music in this style. Desirable results, however, do not come easily and you should expect this part of the part-writing process to be fairly time consuming. Although slow at first, you will eventually find the process becoming faster and faster as you become more and more familiar with common patterns and voice-leading formulae.

As with any music theory assignment, you should also attempt to perform your work in some way. Try singing through each line independently. Try playing through the progression on the piano. Music notation software is also useful for quickly converting notation to sound. Listening to the notes you write is, perhaps, the most efficient way to both check the musicality of your composition and internalize the underlying concepts in a meaningful way.

Proofreading checklists

The following checklists will help you avoid common errors. Use them repeatedly as you write and revise your part-writing. When you finish an exercise, go back and systematically check each note, melody, interval progression (in all six pairs of voices), chord, and overall shape.

Melody (check each voice part individually):

- the melody in each part is singable and musical

- melodies are primarily conjunct (stepwise)

- larger melodic leaps are balanced with stepwise motion in the opposite direction

- melodies contain no tritones

- melodies contain no diminished or augmented intervals

- leading tones in dominant chords— V (7) or vii o (7) —resolve up by step, especially in the bass or soprano

- chordal sevenths resolve down by step

Counterpoint (check all six voice pairs):

- counterpoint comprises mostly standard interval progressions

- voices that form resultant intervals form standard interval progressions with some other part

- counterpoint includes no parallel unisons

- counterpoint includes no parallel fifths

- counterpoint includes no parallel octaves

- counterpoint includes no d5–P5 progressions (P5–d5 is permissible)

- instances of direct motion to a perfect fifth between soprano and bass have soprano moving by step

Chord spelling:

- each notated pitch is a member of the chord at hand

- scale degree seven is raised to form a leading tone for dominant chords— V (7) or vii o (7) —in minor keys

- chord member in the bass corresponds with the position—root position or inversion—of the chord at hand

Chord doubling:

- root position chords double the bass (the root)

- second inversion chords double the bass (the root)

- chords contain no doubled leading tones

- chords contain no doubled sevenths

- chords contain no strong (chromatic) tendency tones

Chord voicing:

- soprano notes are all within the C4 to A5 range

- alto notes are all within the F3 to D5 range

- tenor notes are all within the C3 to A4 range

- bass notes are all within the F2 to E4 range

- voice crossings are avoided ( hint: take special care in checking for voice crossings between the alto and tenor)

- neighboring upper-voice pairs (soprano and alto or alto and tenor) are never more than an octave apart

A time-saving tip

Nothing is more frustrating in completing a part-writing exercise than to think you have finished only to find a glaring error. Re-writing the offending chord often requires further revision as the new voicing creates new problems with each chord that follows. In many cases, however, you do not need to abandon all your hard work.

Take the following progression, for example:

As you can see, there are parallel octaves between the soprano and bass at the end of the first measure. To solve this problem, we could revoice the V chord by putting the C in the soprano, F in the alto, and A in the tenor. However, revoicing only the V chord leads to a new problem since it will create parallel fifths between the soprano and alto at the beginning of the second measure:

Since the voice-leading in the rest of the passage was fine in the first place, we can keep the individual melodies in mm. 2-3 intact. We simply rearrange them among the voices. The following example takes the soprano melody in mm. 2-3 and puts it in the alto part. It also takes the alto and tenor melodies and puts them in the tenor and soprano parts, respectively:

The passage is now error free and we did not have to rewrite mm. 2-3 from scratch. With a bit of rearranging—and some scrap paper and a good eraser—we were able to save ourselves a lot of extra work. Keep this strategy in mind whenever you need to revise your part-writing.

A note to instructors

There are many different ways to evaluate student part-writing exercises and the specifics of assessment are a matter of personal preference. The following mark-up symbols may be used to highlight errors in student part-writing exercises:

The following example shows these symbols in use in a sample exercise:

Fundamentals, Function, and Form Copyright © 2023 by Ivette Herryman Rodriguez, Andre Mount, and Jerod Sommerfeldt is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Integrated Music Theory an open, interactive, online textbook for college music theory

CC BY-NC-SA 2020.

Integrated Music Theory 2020-21

Chapter 10) Introduction to Part-writing ❮ Discussion 10a - Basic Voice Leading Errors | Discussion 10b - Part-writing Errors ❯

Lesson 10b - Part-writing Errors

Part-writing.

The term part-writing can imply many things depending on its context, but for our purposes, this will be our first attempt to combine the fundamentals of melody (counterpoint) and harmony (voice-leading from circle-of-fifths progressions) into functional music using diatonic tonality.

By applying the various rules and techniques that we have studied thus far, we will be able to:

- Harmonize a melody

- Compose a melody given a harmony

- Fully voice four-part harmonies

- Create independent melodic lines that function harmonically together

Units 10 and 11 will help you solidify this process. First, we will establish a reference model by looking at the rules–and resulting errors from breaking those rules–that occur when writing in a four-part chorale style. We will then apply these guidelines to our own attempts to compose basic four-part chorales in order to better understand the voice-leading principles of diatonic music.

We will be referring to this handout, Part-Writing Error Checklist and Guide , for the next two units, so you may want to print this out or open it in a separate window.

Why part-writing?

Before we begin, I would like to address a question that I have received many times from students. Why do we study part-writing rather than just analysis, particularly in a strict style that is not performed regularly by modern musicians?

There are many answers for this, but there is one in particular that I think justifies the study of this in this course. Part-writing is the simplest way to study how voice-leading creates harmony. Even though most of its rules are archaic, and a modern student’s ear is not nearly as offended by certain style characteristics (e.g. parallel perfect fifths), this is the most direct way to study every aspect of how music functions: voice-leading, chord progressions, voicing chords, chordal structure, tendency tones, melodic construction, and so on.

We could attempt to focus on only one style of modern music–whether pop, jazz, classical, or otherwise–but because each is a fully developed, complex language, you would still need to learn basic harmonic movement before beginning to write in that style. And because each of these musics has its roots in diatonic harmony, an understanding of basic chorale style part-writing will allow you to study and develop a process to analyze all of these styles, rather than focusing your studies into only one area and being ignorant of the others.

In short, focus on the process of the part-writing rather than trying to memorize every rule as if it is unbreakable. Even within a style, rules are guidelines, so an inflexible mindset will lead to nothing but frustration. Once you have grasped the basics of part-writing, you will have advanced another step toward the goal of improving your musicianship.

Traditional errors

In the last topic , we first looked at some basic rules for voicing a chord in a four-part chorale style. These rules included:

- In this style, voices generally should not cross

- Exception: alto and tenor may cross briefly if musically necessary

- In this style, the top three voices–soprano, alto, and tenor–should always be within an octave of the adjacent voices. To be more specific, there can never be more than an octave between soprano and alto , and there can never be more than an octave bteween alto and tenor .

- There can be more than an octave between bass and tenor .

- A closed voicing has less than an octave between soprano and tenor .

- An open voicing has more than an octave between soprano and tenor .

- Each part must stay within the typical range for that voice/instrument?

- You can double the root of a chord when possible.

- This is actually more preferable if the triad is in second inversion.

- Do not double the third because it is a tendency tone. If this is doubled, it will force you to choose between the incorrect resolution of a tendency tone or unacceptable parallel octaves. Also, the third should also be least present chord tone in the balance for the chord to sound best.

- Do not double the seventh because it is a tendency tone. If this is doubled, it will force you to choose between the incorrect resolution of a tendency tone or unacceptable parallel octaves.

- Do not double the fifth of a seventh chord. This would require omitting the root, third, or seventh, and none of these are expendable.

Part-writing errors

In addition to the voicing rules, there are a number of standard part-writing errors that should be avoided as well:

- Parallel perfect octaves or perfect fifths

- Similar octaves or fifths (sometimes referred to as “direct”, “hidden”, or “exposed”)

- Unacceptable unequal fifths

- Contrary perfect octaves or perfect fifths

Please note that these errors must be within the same two voices across both chords. Due to the effects of consistently doubling roots, there will almost always be consecutive perfect octaves and perfect fifths between two triads, but this is not parallel . For example, a root position C major triad moving to a root position G triad likely will have two voices on C in the first chord and two voices on G in the second chord, if standard doubling practices are observed. This is fine as long as its not in the same two voices in both chords (e.g. soprano and bass both have C and then both have a G).

Each of the four primary categories of part-writing errors are symptoms of voice-leading issues. If you understand the underlying voice-leading issues of each of these errors, you can find them more easily and avoid them in your own part-writing.

Once you are comfortable with the descriptions of each of the errors below, try to fix each of the errors using the interface. What do you have to change? Do you have to alter the harmony? Voice-leading? Voicing? In trying to fix it, do you just create further errors?

Parallel perfect fifths and perfect octaves (PP5, PP8)

Part-writing errors result from poor voice-leading. For example, look at the progression below and try to find our first major error: parallel perfect octaves (PP8). Once you have found it, look to see if a voicing rule (e.g. spacing, doubling, etc.) has been broken. If the voicing error is not fixed, is there any way to avoid the parallel octaves without incorrectly resolving a tendency tone?

Listen to the following example, and try to locate the parallel perfect fifths aurally before you look through the parts. Once you have identified the voices that contain the PP5, try singing the upper of the two voices, and then listen to the example again. Do you have a difficult time differentiating the upper voice from the lower of these two voices?

Conclusions

PP8 and PP5 undermine the independence of lines, so you should always avoid them in this style. Unacceptable parallel fifths and octaves occur when two voices have consecutive perfect fifths/octaves and move in parallel motion. It is not parallel perfect fifths/octaves if the intervals change voices. (e.g. The first P8/P5 is between the soprano and tenor, but the second P8/P5 is between the soprano and alto.)

In the first example, there are two examples of parallel perfect octaves:

- between the soprano and tenor moving from ii 6 to V 7

- between the soprano and tenor moving from V 7 to I

There is a larger underlying issue, however, because a doubling rule was broken on the V 7 . Because the third was doubled, you are forced to choose between incorrectly resolving one of the leading tones or undermining the independence of the two voices by locking them into consecutive perfect octaves.

In the second example, there are two examples of parallel perfect fifths:

- between the bass and tenor from I to ii

- between the bass and tenor moving from ii to V 7

Parallel perfect fifths and octaves undermine the independence of the individual voices. If you repeatedly listen to the the PP5 example repeatedly, you will find it difficult to distinguish the tenor voice from the bass voice. This effect would be even more pronounced if the chords were tuned using just intonation, because the upper note will blend into the overtone series of the lower note.

In summary, you may never have parallel perfect octaves or parallel perfect fifths in this style of music. Please note that for an interval to be considered parallel , the interval must occur consecutively in the same two voices. For example, if your first P8 is between the bass and alto, the second P8 must also be in the bass and alto. If you find a P8 between the bass and tenor on the second chord, this is acceptable because it does not undermine the independence of the voices.

Contrary perfect fifths and octaves (CP5, CP8)

Our next part-writing error, contrary perfect fifths and contrary perfect octaves (CP5 or CP8) are simply an attempt to cover up parallel perfect fifths and parallel perfect octaves by displacing one voice by an octave. The next two examples attempt to fix the errors from the first two examples on this page by displacing one voice of the parallel perfect intervals. Identify these by comparing them to the previous example (i.e. P) Notice that it creates multiple voicing and spacing errors as well as nearly unsingable parts!

In the second example above, the CP5s occur between bass and tenor voices between:

- the I chord and ii chord

- the ii chord and the V 7 chord

Contrary perfect 5ths/8ves occur when two voices have consecutive perfect fifths/octaves and move in contrary motion. Contrary fifths and octaves occur when trying to mask parallel perfect fifths and octaves, so they will exhibit most of the traits of PP5/PP8 including the fact that the intervals must occur between the same two voices If the interval changes voices, it does not undermine the independence of the voices.

Unacceptable unequal fifths (UU5)

The last two common part-writing errors have specific clauses tied to them that specify which voices are acceptable and unacceptable. The first, unacceptable unequal fifths (UU5), must occur between the bass voice and one of the upper voices. In the following example, find the unacceptable unequal fifths where a d5 moves to a P5. What is wrong with the voice-leading here?

Unacceptable unequal fifths are one of the easier part-writing errors to understand, because we are actually focusing on only one voice-leading issue. And because it is limited to certain voices, it is relatively easy to find compared to parallel and contrary fifths/octaves which are not acceptable between any voices.

For this course, we will consider a d5 moving to a P5 unacceptable unequal fifths, but we will consider a P5 moving to a d5 as acceptable –a P5 to a d5 does not require poor resolutions of tendency tones. Remember that these errors are best thought of as symptoms of the actual problem. In this case, the real issue is that the only two notes in a diatonic key that can form a d5 are ti and fa , and as discussed many times in this course, these two notes imply a dominant harmony that wants to resolve inward with ti moving to do and fa moving to mi . For a d5 to be followed by a P5, it would mean that fa must resolve to sol –or less commonly, ti resolving to la as part of a deceptive progression–which is poor voice-leading and therefore the error we are trying to avoid. There are some stricter versions of chorale part-writing that do not allow any form of unequal fifths.

Unacceptable similar fifths or octaves (US5, US8)

The final common part-writing has many names, but we will use the term unacceptable similar fifths or octaves . The term similar can also be replaced with “direct”, “hidden”, or “exposed”. I prefer the term similar because it describes the motion like the other categories, but I also think that exposed does a fine job describing the effect. (I dislike the term hidden because students often confuse this with contrary fifths (or octaves), because the goal of contrary fifths is to “hide” parallel fifths.) Unacceptable similar fifths or octaves have the most restrictions. The conditions are:

- They can only occur between the soprano and the bass voices.

- They require a skip of a third or more in the soprano voice.

- The two voices must move in similar (not parallel) motion.

- The second interval must be a P5 or P8.

If any one of these conditions are not met, then this error does not exist in that case. Look at the following example to find an example of similar octaves . Once you have found it, look at the voice-leading around it. What does it do to spacing? Does it create more errors? Unacceptable similar octaves and fifths also often create melodies that imply different harmonies. To demonstrate, sing the melody alone. Do you hear it as C major or a different key?

Similar fifths/octaves occur when 1) the soprano and bass voices 2) move in similar motion to a 3) perfect fifth/octave, and 4) the soprano voice has a skip of a third or larger. You can see an example of this between the first two chords in this example.

Similar fifths/octaves are sometimes called “exposed” fifths/octaves, and both of these terms demonstrate a key feature about the part-writing error. Obviously, they must move in similar motion, but the term “exposed” highlights the fact that these must occur between the outer voices. By having similar motion to a perfect interval in the outer voices, it creates the impression of a parallel perfect interval. Most importantly, the leap in the soprano typically creates a poor soprano line in which the melody outlines/implies an unintentional harmony. In the example above, if you sing the melody line without the harmony it outlines A minor instead of C major.

COMMENTS

When a leap is found, look to see if there is similar motion in the bass (not parallel) Determine the interval between the outer voices of the second chord. - If this interval is either a P5 or P8, there is a similar 5th or 8ve. Parallel Perfect 5ths and 8ves. Determine the interval between each pitch horizontally (melodically - NOT within ...

This is most commonly used as an ending chord of the piece (often after a V7). Doubling in a seventh chord is similar, but because you have four notes for four voices, there is less freedom. There must always be a root, third, and seventh in the chord, because without any of them, the chord is no longer a functional seventh chord.

In addition to the voicing rules, there are a number of standard part-writing errors that should be avoided as well: Parallel perfect octaves or perfect fifths. Similar octaves or fifths (sometimes referred to as "direct", "hidden", or "exposed") Unacceptable unequal fifths. Contrary perfect octaves or perfect fifths.

Music Theory for the 21st-Century Classroom

26.6. Rules of Spacing. Generally, the upper three voice parts (soprano, alto, and tenor) are kept close together. The general rule of spacing is to keep the distance between soprano and alto as well as the distance between alto to tenor within an octave of each other. Allowing a distance greater than an octave between soprano and alto (or ...

Q The musicians guide to theory and analysis workbook chapter 12 analyzing chorale-style voicing and spacing writing basic Answered over 90d ago Q assignment 13.5 I. writing basic phrases with predominants write the following progressions in SATB voicing in the meter

Q Compose2, 8 Bar Melodies - Choose 2 different Major Keys - 1 in either 4/4 or 2/2 - 1 in 3/4 Answered over 90d ago Q I need help providing an analysis for chords.

Overview 10b - Part-writing Errors. In Unit 6b, we first looked at some basic rules for voicing a chord in a four-part style. These rules included: Voice-crossing. In this style, voices should generally not cross. Exception: alto and tenor may cross briefly if musically necessary. Spacing.

About Press Copyright Contact us Creators Advertise Developers Terms Privacy Policy & Safety How YouTube works Test new features NFL Sunday Ticket Press Copyright ...

Similar 5ths and 8ves. Follow the soprano line looking for skip of a 3rd or more. When a skip is found, look to see if there is similar motion in the bass (not parallel) Determine the interval between the outer voices of the second chord. - If this interval is either a P5 or P8, there is a similar 5th or 8ve. Practice on this example.

The last two common part-writing errors have specific clauses tied to them that specify which voices are acceptable and unacceptable. The first, unacceptable unequal fifths, must occur between the bass voice and one of the upper voices. In the following example, find the unacceptable unequal fifths where a d5 moves to a P5.

12) Instrument Transpositions, Ranges, and Score Reduction ... Have soprano sing a D on the second and third chords? BASICALLY: fixing the errors is never as simple as you want it, and there's a bunch of different ways to do it. ... It isn't ideal to sing and usually creates spacing errors as a result; Red flag: if there's a HUGE leap in ...

For anything that is played differently than the notated version: 1) circle it and 2) write in what was played instead of the notated version. Note: differences may be in any of the four voices and in the Roman numeral analysis; you should circle and make changes to any pitches and any Roman numerals that are affected by errors.

NAME 12 The Basic Phrase and Four-Part Writing ASSIGNMENT 12.1 1, Analyzing cadence types Identify the key of each excerpt, and write Roman numerals for the two chords that end each phrase. Circle Q&A

Richmond County School System / Welcome

B C E. 40. Dairy The diameter of the base of a 59 in. cylindrical milk tank is 59 in.The length of the tank is 470 in.You estimate that the depth of the milk in the tank is 20 in. 20 in. 470 in. Find the number of gallons of milk in the. not to scale. tank to the nearest gallon.(1 gal 231 in.3) 1661 gal. =.

Create independent melodic lines that function harmonically together. Units 10 and 11 will help you solidify this process, beginning with a demonstration of the fundamentals of part-writing using only our basic knowledge, then exploring the stylistic errors of four-part chorale writing, and finally fully applying part-writing in a chorale style.

View image.jpg from CIS MISC at Thomas S. Wootton High. e Assignment 12.2 L. Error detection in chord spacing, Write the root, quality, and inversion (§, §, or ...

Pay careful attention to the quality of each chord, particularly in minor keys. One of the most common errors students make in chord spelling is forgetting to raise scale degree [latex]\hat7[/latex] in minor-key dominant chords. In the following example, a V 7 chord in G minor must have F # instead of F § to match the case of the Roman numeral:

Doc Nov 07, 2018, 18:37 - Read online for free. Music theory hknework

In addition to the voicing rules, there are a number of standard part-writing errors that should be avoided as well: Parallel perfect octaves or perfect fifths. Similar octaves or fifths (sometimes referred to as "direct", "hidden", or "exposed") Unacceptable unequal fifths. Contrary perfect octaves or perfect fifths.

Unformatted text preview: Assignment 12.2 I. Scale-degree triads in inversion , doubling, and spacing. In minor keys, g, stem direction SATB voicin use the leading tone to spell the chords built on 3 and 77' staff in the specified inversion. Use proper M Chapter 12 The Basic Phrase in SATB Style Assignment 12.3