Thesis Statements

What this handout is about.

This handout describes what a thesis statement is, how thesis statements work in your writing, and how you can craft or refine one for your draft.

Introduction

Writing in college often takes the form of persuasion—convincing others that you have an interesting, logical point of view on the subject you are studying. Persuasion is a skill you practice regularly in your daily life. You persuade your roommate to clean up, your parents to let you borrow the car, your friend to vote for your favorite candidate or policy. In college, course assignments often ask you to make a persuasive case in writing. You are asked to convince your reader of your point of view. This form of persuasion, often called academic argument, follows a predictable pattern in writing. After a brief introduction of your topic, you state your point of view on the topic directly and often in one sentence. This sentence is the thesis statement, and it serves as a summary of the argument you’ll make in the rest of your paper.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement:

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- makes a claim that others might dispute.

- is usually a single sentence near the beginning of your paper (most often, at the end of the first paragraph) that presents your argument to the reader. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the reader of the logic of your interpretation.

If your assignment asks you to take a position or develop a claim about a subject, you may need to convey that position or claim in a thesis statement near the beginning of your draft. The assignment may not explicitly state that you need a thesis statement because your instructor may assume you will include one. When in doubt, ask your instructor if the assignment requires a thesis statement. When an assignment asks you to analyze, to interpret, to compare and contrast, to demonstrate cause and effect, or to take a stand on an issue, it is likely that you are being asked to develop a thesis and to support it persuasively. (Check out our handout on understanding assignments for more information.)

How do I create a thesis?

A thesis is the result of a lengthy thinking process. Formulating a thesis is not the first thing you do after reading an essay assignment. Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. Once you do this thinking, you will probably have a “working thesis” that presents a basic or main idea and an argument that you think you can support with evidence. Both the argument and your thesis are likely to need adjustment along the way.

Writers use all kinds of techniques to stimulate their thinking and to help them clarify relationships or comprehend the broader significance of a topic and arrive at a thesis statement. For more ideas on how to get started, see our handout on brainstorming .

How do I know if my thesis is strong?

If there’s time, run it by your instructor or make an appointment at the Writing Center to get some feedback. Even if you do not have time to get advice elsewhere, you can do some thesis evaluation of your own. When reviewing your first draft and its working thesis, ask yourself the following :

- Do I answer the question? Re-reading the question prompt after constructing a working thesis can help you fix an argument that misses the focus of the question. If the prompt isn’t phrased as a question, try to rephrase it. For example, “Discuss the effect of X on Y” can be rephrased as “What is the effect of X on Y?”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it’s possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like “good” or “successful,” see if you could be more specific: why is something “good”; what specifically makes something “successful”?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? If a reader’s first response is likely to be “So what?” then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering? If your thesis and the body of your essay do not seem to go together, one of them has to change. It’s okay to change your working thesis to reflect things you have figured out in the course of writing your paper. Remember, always reassess and revise your writing as necessary.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? If a reader’s first response is “how?” or “why?” your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

Suppose you are taking a course on contemporary communication, and the instructor hands out the following essay assignment: “Discuss the impact of social media on public awareness.” Looking back at your notes, you might start with this working thesis:

Social media impacts public awareness in both positive and negative ways.

You can use the questions above to help you revise this general statement into a stronger thesis.

- Do I answer the question? You can analyze this if you rephrase “discuss the impact” as “what is the impact?” This way, you can see that you’ve answered the question only very generally with the vague “positive and negative ways.”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not likely. Only people who maintain that social media has a solely positive or solely negative impact could disagree.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? No. What are the positive effects? What are the negative effects?

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? No. Why are they positive? How are they positive? What are their causes? Why are they negative? How are they negative? What are their causes?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? No. Why should anyone care about the positive and/or negative impact of social media?

After thinking about your answers to these questions, you decide to focus on the one impact you feel strongly about and have strong evidence for:

Because not every voice on social media is reliable, people have become much more critical consumers of information, and thus, more informed voters.

This version is a much stronger thesis! It answers the question, takes a specific position that others can challenge, and it gives a sense of why it matters.

Let’s try another. Suppose your literature professor hands out the following assignment in a class on the American novel: Write an analysis of some aspect of Mark Twain’s novel Huckleberry Finn. “This will be easy,” you think. “I loved Huckleberry Finn!” You grab a pad of paper and write:

Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is a great American novel.

You begin to analyze your thesis:

- Do I answer the question? No. The prompt asks you to analyze some aspect of the novel. Your working thesis is a statement of general appreciation for the entire novel.

Think about aspects of the novel that are important to its structure or meaning—for example, the role of storytelling, the contrasting scenes between the shore and the river, or the relationships between adults and children. Now you write:

In Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain develops a contrast between life on the river and life on the shore.

- Do I answer the question? Yes!

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not really. This contrast is well-known and accepted.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? It’s getting there–you have highlighted an important aspect of the novel for investigation. However, it’s still not clear what your analysis will reveal.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? Not yet. Compare scenes from the book and see what you discover. Free write, make lists, jot down Huck’s actions and reactions and anything else that seems interesting.

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? What’s the point of this contrast? What does it signify?”

After examining the evidence and considering your own insights, you write:

Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

This final thesis statement presents an interpretation of a literary work based on an analysis of its content. Of course, for the essay itself to be successful, you must now present evidence from the novel that will convince the reader of your interpretation.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ramage, John D., John C. Bean, and June Johnson. 2018. The Allyn & Bacon Guide to Writing , 8th ed. New York: Pearson.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Developing a Thesis Statement

Many papers you write require developing a thesis statement. In this section you’ll learn what a thesis statement is and how to write one.

Keep in mind that not all papers require thesis statements . If in doubt, please consult your instructor for assistance.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement . . .

- Makes an argumentative assertion about a topic; it states the conclusions that you have reached about your topic.

- Makes a promise to the reader about the scope, purpose, and direction of your paper.

- Is focused and specific enough to be “proven” within the boundaries of your paper.

- Is generally located near the end of the introduction ; sometimes, in a long paper, the thesis will be expressed in several sentences or in an entire paragraph.

- Identifies the relationships between the pieces of evidence that you are using to support your argument.

Not all papers require thesis statements! Ask your instructor if you’re in doubt whether you need one.

Identify a topic

Your topic is the subject about which you will write. Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic; or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper.

Consider what your assignment asks you to do

Inform yourself about your topic, focus on one aspect of your topic, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts, generate a topic from an assignment.

Below are some possible topics based on sample assignments.

Sample assignment 1

Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II.

Identified topic

Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis

This topic avoids generalities such as “Spain” and “World War II,” addressing instead on Franco’s role (a specific aspect of “Spain”) and the diplomatic relations between the Allies and Axis (a specific aspect of World War II).

Sample assignment 2

Analyze one of Homer’s epic similes in the Iliad.

The relationship between the portrayal of warfare and the epic simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64.

This topic focuses on a single simile and relates it to a single aspect of the Iliad ( warfare being a major theme in that work).

Developing a Thesis Statement–Additional information

Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic, or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper. You’ll want to read your assignment carefully, looking for key terms that you can use to focus your topic.

Sample assignment: Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II Key terms: analyze, Spain’s neutrality, World War II

After you’ve identified the key words in your topic, the next step is to read about them in several sources, or generate as much information as possible through an analysis of your topic. Obviously, the more material or knowledge you have, the more possibilities will be available for a strong argument. For the sample assignment above, you’ll want to look at books and articles on World War II in general, and Spain’s neutrality in particular.

As you consider your options, you must decide to focus on one aspect of your topic. This means that you cannot include everything you’ve learned about your topic, nor should you go off in several directions. If you end up covering too many different aspects of a topic, your paper will sprawl and be unconvincing in its argument, and it most likely will not fulfull the assignment requirements.

For the sample assignment above, both Spain’s neutrality and World War II are topics far too broad to explore in a paper. You may instead decide to focus on Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis , which narrows down what aspects of Spain’s neutrality and World War II you want to discuss, as well as establishes a specific link between those two aspects.

Before you go too far, however, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts. Try to avoid topics that already have too much written about them (i.e., “eating disorders and body image among adolescent women”) or that simply are not important (i.e. “why I like ice cream”). These topics may lead to a thesis that is either dry fact or a weird claim that cannot be supported. A good thesis falls somewhere between the two extremes. To arrive at this point, ask yourself what is new, interesting, contestable, or controversial about your topic.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times . Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Derive a main point from topic

Once you have a topic, you will have to decide what the main point of your paper will be. This point, the “controlling idea,” becomes the core of your argument (thesis statement) and it is the unifying idea to which you will relate all your sub-theses. You can then turn this “controlling idea” into a purpose statement about what you intend to do in your paper.

Look for patterns in your evidence

Compose a purpose statement.

Consult the examples below for suggestions on how to look for patterns in your evidence and construct a purpose statement.

- Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis

- Franco turned to the Allies when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from the Axis

Possible conclusion:

Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: Franco’s desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power.

Purpose statement

This paper will analyze Franco’s diplomacy during World War II to see how it contributed to Spain’s neutrality.

- The simile compares Simoisius to a tree, which is a peaceful, natural image.

- The tree in the simile is chopped down to make wheels for a chariot, which is an object used in warfare.

At first, the simile seems to take the reader away from the world of warfare, but we end up back in that world by the end.

This paper will analyze the way the simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64 moves in and out of the world of warfare.

Derive purpose statement from topic

To find out what your “controlling idea” is, you have to examine and evaluate your evidence . As you consider your evidence, you may notice patterns emerging, data repeated in more than one source, or facts that favor one view more than another. These patterns or data may then lead you to some conclusions about your topic and suggest that you can successfully argue for one idea better than another.

For instance, you might find out that Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis, but when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from them, he turned to the Allies. As you read more about Franco’s decisions, you may conclude that Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: his desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power. Based on this conclusion, you can then write a trial thesis statement to help you decide what material belongs in your paper.

Sometimes you won’t be able to find a focus or identify your “spin” or specific argument immediately. Like some writers, you might begin with a purpose statement just to get yourself going. A purpose statement is one or more sentences that announce your topic and indicate the structure of the paper but do not state the conclusions you have drawn . Thus, you might begin with something like this:

- This paper will look at modern language to see if it reflects male dominance or female oppression.

- I plan to analyze anger and derision in offensive language to see if they represent a challenge of society’s authority.

At some point, you can turn a purpose statement into a thesis statement. As you think and write about your topic, you can restrict, clarify, and refine your argument, crafting your thesis statement to reflect your thinking.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Compose a draft thesis statement

If you are writing a paper that will have an argumentative thesis and are having trouble getting started, the techniques in the table below may help you develop a temporary or “working” thesis statement.

Begin with a purpose statement that you will later turn into a thesis statement.

Assignment: Discuss the history of the Reform Party and explain its influence on the 1990 presidential and Congressional election.

Purpose Statement: This paper briefly sketches the history of the grassroots, conservative, Perot-led Reform Party and analyzes how it influenced the economic and social ideologies of the two mainstream parties.

Question-to-Assertion

If your assignment asks a specific question(s), turn the question(s) into an assertion and give reasons why it is true or reasons for your opinion.

Assignment : What do Aylmer and Rappaccini have to be proud of? Why aren’t they satisfied with these things? How does pride, as demonstrated in “The Birthmark” and “Rappaccini’s Daughter,” lead to unexpected problems?

Beginning thesis statement: Alymer and Rappaccinni are proud of their great knowledge; however, they are also very greedy and are driven to use their knowledge to alter some aspect of nature as a test of their ability. Evil results when they try to “play God.”

Write a sentence that summarizes the main idea of the essay you plan to write.

Main idea: The reason some toys succeed in the market is that they appeal to the consumers’ sense of the ridiculous and their basic desire to laugh at themselves.

Make a list of the ideas that you want to include; consider the ideas and try to group them.

- nature = peaceful

- war matériel = violent (competes with 1?)

- need for time and space to mourn the dead

- war is inescapable (competes with 3?)

Use a formula to arrive at a working thesis statement (you will revise this later).

- although most readers of _______ have argued that _______, closer examination shows that _______.

- _______ uses _______ and _____ to prove that ________.

- phenomenon x is a result of the combination of __________, __________, and _________.

What to keep in mind as you draft an initial thesis statement

Beginning statements obtained through the methods illustrated above can serve as a framework for planning or drafting your paper, but remember they’re not yet the specific, argumentative thesis you want for the final version of your paper. In fact, in its first stages, a thesis statement usually is ill-formed or rough and serves only as a planning tool.

As you write, you may discover evidence that does not fit your temporary or “working” thesis. Or you may reach deeper insights about your topic as you do more research, and you will find that your thesis statement has to be more complicated to match the evidence that you want to use.

You must be willing to reject or omit some evidence in order to keep your paper cohesive and your reader focused. Or you may have to revise your thesis to match the evidence and insights that you want to discuss. Read your draft carefully, noting the conclusions you have drawn and the major ideas which support or prove those conclusions. These will be the elements of your final thesis statement.

Sometimes you will not be able to identify these elements in your early drafts, but as you consider how your argument is developing and how your evidence supports your main idea, ask yourself, “ What is the main point that I want to prove/discuss? ” and “ How will I convince the reader that this is true? ” When you can answer these questions, then you can begin to refine the thesis statement.

Refine and polish the thesis statement

To get to your final thesis, you’ll need to refine your draft thesis so that it’s specific and arguable.

- Ask if your draft thesis addresses the assignment

- Question each part of your draft thesis

- Clarify vague phrases and assertions

- Investigate alternatives to your draft thesis

Consult the example below for suggestions on how to refine your draft thesis statement.

Sample Assignment

Choose an activity and define it as a symbol of American culture. Your essay should cause the reader to think critically about the society which produces and enjoys that activity.

- Ask The phenomenon of drive-in facilities is an interesting symbol of american culture, and these facilities demonstrate significant characteristics of our society.This statement does not fulfill the assignment because it does not require the reader to think critically about society.

Drive-ins are an interesting symbol of American culture because they represent Americans’ significant creativity and business ingenuity.

Among the types of drive-in facilities familiar during the twentieth century, drive-in movie theaters best represent American creativity, not merely because they were the forerunner of later drive-ins and drive-throughs, but because of their impact on our culture: they changed our relationship to the automobile, changed the way people experienced movies, and changed movie-going into a family activity.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast-food establishments, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize America’s economic ingenuity, they also have affected our personal standards.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast- food restaurants, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize (1) Americans’ business ingenuity, they also have contributed (2) to an increasing homogenization of our culture, (3) a willingness to depersonalize relationships with others, and (4) a tendency to sacrifice quality for convenience.

This statement is now specific and fulfills all parts of the assignment. This version, like any good thesis, is not self-evident; its points, 1-4, will have to be proven with evidence in the body of the paper. The numbers in this statement indicate the order in which the points will be presented. Depending on the length of the paper, there could be one paragraph for each numbered item or there could be blocks of paragraph for even pages for each one.

Complete the final thesis statement

The bottom line.

As you move through the process of crafting a thesis, you’ll need to remember four things:

- Context matters! Think about your course materials and lectures. Try to relate your thesis to the ideas your instructor is discussing.

- As you go through the process described in this section, always keep your assignment in mind . You will be more successful when your thesis (and paper) responds to the assignment than if it argues a semi-related idea.

- Your thesis statement should be precise, focused, and contestable ; it should predict the sub-theses or blocks of information that you will use to prove your argument.

- Make sure that you keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Change your thesis as your paper evolves, because you do not want your thesis to promise more than your paper actually delivers.

In the beginning, the thesis statement was a tool to help you sharpen your focus, limit material and establish the paper’s purpose. When your paper is finished, however, the thesis statement becomes a tool for your reader. It tells the reader what you have learned about your topic and what evidence led you to your conclusion. It keeps the reader on track–well able to understand and appreciate your argument.

Writing Process and Structure

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Getting Started with Your Paper

Interpreting Writing Assignments from Your Courses

Generating Ideas for

Creating an Argument

Thesis vs. Purpose Statements

Architecture of Arguments

Working with Sources

Quoting and Paraphrasing Sources

Using Literary Quotations

Citing Sources in Your Paper

Drafting Your Paper

Generating Ideas for Your Paper

Introductions

Paragraphing

Developing Strategic Transitions

Conclusions

Revising Your Paper

Peer Reviews

Reverse Outlines

Revising an Argumentative Paper

Revision Strategies for Longer Projects

Finishing Your Paper

Twelve Common Errors: An Editing Checklist

How to Proofread your Paper

Writing Collaboratively

Collaborative and Group Writing

Think of yourself as a member of a jury, listening to a lawyer who is presenting an opening argument. You'll want to know very soon whether the lawyer believes the accused to be guilty or not guilty, and how the lawyer plans to convince you. Readers of academic essays are like jury members: before they have read too far, they want to know what the essay argues as well as how the writer plans to make the argument. After reading your thesis statement, the reader should think, "This essay is going to try to convince me of something. I'm not convinced yet, but I'm interested to see how I might be."

An effective thesis cannot be answered with a simple "yes" or "no." A thesis is not a topic; nor is it a fact; nor is it an opinion. "Reasons for the fall of communism" is a topic. "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe" is a fact known by educated people. "The fall of communism is the best thing that ever happened in Europe" is an opinion. (Superlatives like "the best" almost always lead to trouble. It's impossible to weigh every "thing" that ever happened in Europe. And what about the fall of Hitler? Couldn't that be "the best thing"?)

A good thesis has two parts. It should tell what you plan to argue, and it should "telegraph" how you plan to argue—that is, what particular support for your claim is going where in your essay.

Steps in Constructing a Thesis

First, analyze your primary sources. Look for tension, interest, ambiguity, controversy, and/or complication. Does the author contradict himself or herself? Is a point made and later reversed? What are the deeper implications of the author's argument? Figuring out the why to one or more of these questions, or to related questions, will put you on the path to developing a working thesis. (Without the why, you probably have only come up with an observation—that there are, for instance, many different metaphors in such-and-such a poem—which is not a thesis.)

Once you have a working thesis, write it down. There is nothing as frustrating as hitting on a great idea for a thesis, then forgetting it when you lose concentration. And by writing down your thesis you will be forced to think of it clearly, logically, and concisely. You probably will not be able to write out a final-draft version of your thesis the first time you try, but you'll get yourself on the right track by writing down what you have.

Keep your thesis prominent in your introduction. A good, standard place for your thesis statement is at the end of an introductory paragraph, especially in shorter (5-15 page) essays. Readers are used to finding theses there, so they automatically pay more attention when they read the last sentence of your introduction. Although this is not required in all academic essays, it is a good rule of thumb.

Anticipate the counterarguments. Once you have a working thesis, you should think about what might be said against it. This will help you to refine your thesis, and it will also make you think of the arguments that you'll need to refute later on in your essay. (Every argument has a counterargument. If yours doesn't, then it's not an argument—it may be a fact, or an opinion, but it is not an argument.)

This statement is on its way to being a thesis. However, it is too easy to imagine possible counterarguments. For example, a political observer might believe that Dukakis lost because he suffered from a "soft-on-crime" image. If you complicate your thesis by anticipating the counterargument, you'll strengthen your argument, as shown in the sentence below.

Some Caveats and Some Examples

A thesis is never a question. Readers of academic essays expect to have questions discussed, explored, or even answered. A question ("Why did communism collapse in Eastern Europe?") is not an argument, and without an argument, a thesis is dead in the water.

A thesis is never a list. "For political, economic, social and cultural reasons, communism collapsed in Eastern Europe" does a good job of "telegraphing" the reader what to expect in the essay—a section about political reasons, a section about economic reasons, a section about social reasons, and a section about cultural reasons. However, political, economic, social and cultural reasons are pretty much the only possible reasons why communism could collapse. This sentence lacks tension and doesn't advance an argument. Everyone knows that politics, economics, and culture are important.

A thesis should never be vague, combative or confrontational. An ineffective thesis would be, "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe because communism is evil." This is hard to argue (evil from whose perspective? what does evil mean?) and it is likely to mark you as moralistic and judgmental rather than rational and thorough. It also may spark a defensive reaction from readers sympathetic to communism. If readers strongly disagree with you right off the bat, they may stop reading.

An effective thesis has a definable, arguable claim. "While cultural forces contributed to the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe, the disintegration of economies played the key role in driving its decline" is an effective thesis sentence that "telegraphs," so that the reader expects the essay to have a section about cultural forces and another about the disintegration of economies. This thesis makes a definite, arguable claim: that the disintegration of economies played a more important role than cultural forces in defeating communism in Eastern Europe. The reader would react to this statement by thinking, "Perhaps what the author says is true, but I am not convinced. I want to read further to see how the author argues this claim."

A thesis should be as clear and specific as possible. Avoid overused, general terms and abstractions. For example, "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe because of the ruling elite's inability to address the economic concerns of the people" is more powerful than "Communism collapsed due to societal discontent."

Copyright 1999, Maxine Rodburg and The Tutors of the Writing Center at Harvard University

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

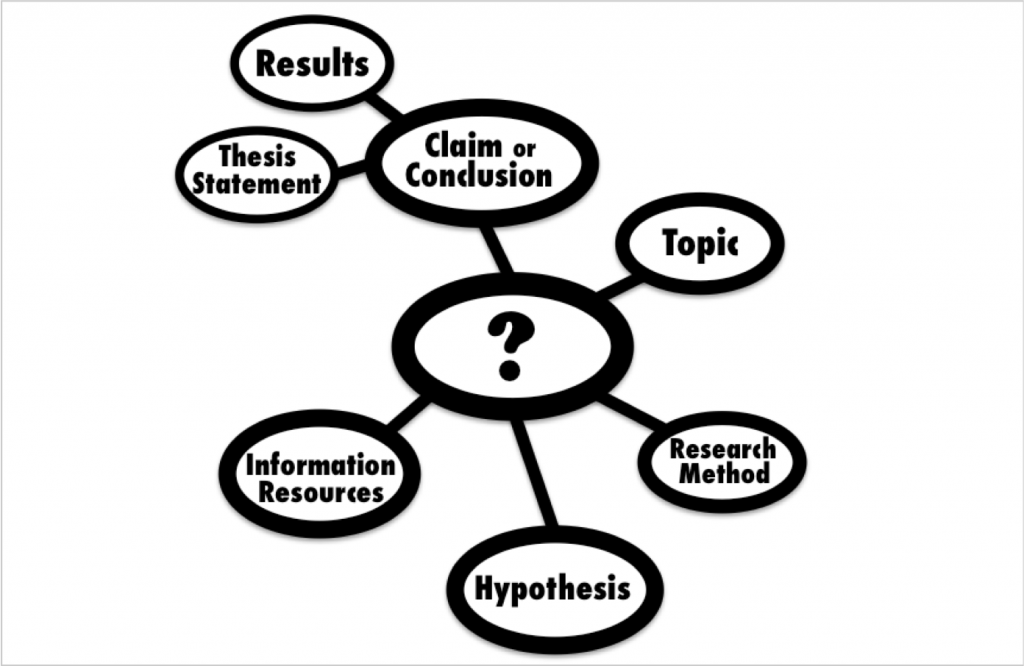

Whether you’re developing research questions for your personal life, your work for an employer, or for academic purposes, the process always forces you to figure out exactly:

- What you’re interested in finding out.

- What is feasible for you to find out given your time, money, and access to information sources.

- How to find information, including what research methods will be necessary and what information sources will be relevant.

- What kind of claims you’ll be able to make or conclusions you’ll be able to draw about what you found out.

For academic purposes, you may have to develop research questions to carry out both small and large assignments. A smaller assignment may include doing research for a class discussion or to, say, write a blog post for a class; larger assignments may have you conduct research and critical assessment, then report it in a lab report, poster, term paper, or article. For large projects, the research question (or questions) you develop will define or at least heavily influence:

- Your topic , which is a part of your research question, effectively narrows the topic you’ve first chosen or been assigned by your instructor.

- What, if any, hypotheses you test.

- Which information sources are relevant to your project.

- Which research methods are appropriate.

- What claims you can make or conclusions you can come to as a result of your research, including what thesis statement you should write for a term paper or what you should write about in the results section based on the data you collected in your science or social science study.

Influence on Thesis

Within an essay, poster, or term paper, the thesis is the researcher’s answer to the research question(s). So as you develop research questions, you are effectively specifying what any thesis in your project will be about. While perhaps many research questions could have come from your original topic, your question states exactly which one(s) your thesis will be answering . For example, a topic that starts as “desert symbiosis” could eventually lead to a research question that is “how does the diversity of bacteria in the gut of the Sonoran Desert termite contribute to the termite’s survival?” In turn, the researcher’s thesis will answer that particular research question instead of the numerous other questions that could have come from the desert symbiosis topic.

Developing research questions is all part of a process that leads to the specificity of your project.

Tip: Don’t Make These Mistakes

Sometimes students inexperienced at working with research questions confuse them with the search statements they will type into the search box of a search engine or database when looking for sources for their project. Or, they confuse research questions with the thesis statement they will write when they report their research. The activity below will help you sort things out.

Influence on Hypothesis

If you’re doing a study that predicts how variables are related, you’ll have to write at least one hypothesis. The research questions you write will contain the variables that will later appear in your hypothesis(es).

Influence on Resources

You can’t tell whether an information source is relevant to your research until you know exactly what you’re trying to find out. Since it’s the research questions that define that, they divide all information sources into two groups: those that are relevant to your research and those that are not—all based on whether each source can help you find out what you want to find out and/or report the answer.

Influence on Research Methods

Your research question(s) will help you figure out what research methods you should use because the questions reflect what your research is intended to do. For instance, if your research question relates to describing a group, survey methods may work well. But they can’t answer cause-and-effect questions.

Influence on Claims or Conclusions

The research questions you write will reflect whether your research is intended to describe a group or situation, to explain or predict outcomes, or to demonstrate a cause-and-effect relationship(s) among variables. It’s those intentions and how well you carry out the study, including whether you used methods appropriate to the intentions, that will determine what claims or conclusions you can make as a result of your research.

Exercise: From Topic to Thesis Statement

Critical Thinking in Academic Research Copyright © 2022 by Cindy Gruwell and Robin Ewing is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.5 Critical Thinking and Research Applications

Learning objectives.

- Analyze source materials to determine how they support or refute the working thesis.

- Identify connections between source materials and eliminate redundant or irrelevant source materials.

- Identify instances when it is appropriate to use human sources, such as interviews or eyewitness testimony.

- Select information from sources to begin answering the research questions.

- Determine an appropriate organizational structure for the research paper that uses critical analysis to connect the writer’s ideas and information taken from sources.

At this point in your project, you are preparing to move from the research phase to the writing phase. You have gathered much of the information you will use, and soon you will be ready to begin writing your draft. This section helps you transition smoothly from one phase to the next.

Beginning writers sometimes attempt to transform a pile of note cards into a formal research paper without any intermediary step. This approach presents problems. The writer’s original question and thesis may be buried in a flood of disconnected details taken from research sources. The first draft may present redundant or contradictory information. Worst of all, the writer’s ideas and voice may be lost.

An effective research paper focuses on the writer’s ideas—from the question that sparked the research process to how the writer answers that question based on the research findings. Before beginning a draft, or even an outline, good writers pause and reflect. They ask themselves questions such as the following:

- How has my thinking changed based on my research? What have I learned?

- Was my working thesis on target? Do I need to rework my thesis based on what I have learned?

- How does the information in my sources mesh with my research questions and help me answer those questions? Have any additional important questions or subtopics come up that I will need to address in my paper?

- How do my sources complement each other? What ideas or facts recur in multiple sources?

- Where do my sources disagree with each other, and why?

In this section, you will reflect on your research and review the information you have gathered. You will determine what you now think about your topic. You will synthesize , or put together, different pieces of information that help you answer your research questions. Finally, you will determine the organizational structure that works best for your paper and begin planning your outline.

Review the research questions and working thesis you developed in Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” , Section 11.2 “Steps in Developing a Research Proposal” . Set a timer for ten minutes and write about your topic, using your questions and thesis to guide your writing. Complete this exercise without looking over your notes or sources. Base your writing on the overall impressions and concepts you have absorbed while conducting research. If additional, related questions come to mind, jot them down.

Selecting Useful Information

At this point in the research process, you have gathered information from a wide variety of sources. Now it is time to think about how you will use this information as a writer.

When you conduct research, you keep an open mind and seek out many promising sources. You take notes on any information that looks like it might help you answer your research questions. Often, new ideas and terms come up in your reading, and these, too, find their way into your notes. You may record facts or quotations that catch your attention even if they did not seem immediately relevant to your research question. By now, you have probably amassed an impressively detailed collection of notes.

You will not use all of your notes in your paper.

Good researchers are thorough. They look at multiple perspectives, facts, and ideas related to their topic, and they gather a great deal of information. Effective writers, however, are selective. They determine which information is most relevant and appropriate for their purpose. They include details that develop or explain their ideas—and they leave out details that do not. The writer, not the pile of notes, is the controlling force. The writer shapes the content of the research paper.

While working through Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” , Section 11.4 “Strategies for Gathering Reliable Information” , you used strategies to filter out unreliable or irrelevant sources and details. Now you will apply your critical-thinking skills to the information you recorded—analyzing how it is relevant, determining how it meshes with your ideas, and finding how it forms connections and patterns.

Writing at Work

When you create workplace documents based on research, selectivity remains important. A project team may spend months conducting market surveys to prepare for rolling out a new product, but few managers have time to read the research in its entirety. Most employees want the research distilled into a few well-supported points. Focused, concise writing is highly valued in the workplace.

Identify Information That Supports Your Thesis

In Note 11.81 “Exercise 1” , you revisited your research questions and working thesis. The process of writing informally helped you see how you might begin to pull together what you have learned from your research. Do not feel anxious, however, if you still have trouble seeing the big picture. Systematically looking through your notes will help you.

Begin by identifying the notes that clearly support your thesis. Mark or group these, either physically or using the cut-and-paste function in your word-processing program. As you identify the crucial details that support your thesis, make sure you analyze them critically. Ask the following questions to focus your thinking:

- Is this detail from a reliable, high-quality source? Is it appropriate for me to cite this source in an academic paper? The bulk of the support for your thesis should come from reliable, reputable sources. If most of the details that support your thesis are from less-reliable sources, you may need to do additional research or modify your thesis.

- Is the link between this information and my thesis obvious—or will I need to explain it to my readers? Remember, you have spent more time thinking and reading about this topic than your audience. Some connections might be obvious to both you and your readers. More often, however, you will need to provide the analysis or explanation that shows how the information supports your thesis. As you read through your notes, jot down ideas you have for making those connections clear.

- What personal biases or experiences might affect the way I interpret this information? No researcher is 100 percent objective. We all have personal opinions and experiences that influence our reactions to what we read and learn. Good researchers are aware of this human tendency. They keep an open mind when they read opinions or facts that contradict their beliefs.

It can be tempting to ignore information that does not support your thesis or that contradicts it outright. However, such information is important. At the very least, it gives you a sense of what has been written about the issue. More importantly, it can help you question and refine your own thinking so that writing your research paper is a true learning process.

Find Connections between Your Sources

As you find connections between your ideas and information in your sources, also look for information that connects your sources. Do most sources seem to agree on a particular idea? Are some facts mentioned repeatedly in many different sources? What key terms or major concepts come up in most of your sources regardless of whether the sources agree on the finer points? Identifying these connections will help you identify important ideas to discuss in your paper.

Look for subtler ways your sources complement one another, too. Does one author refer to another’s book or article? How do sources that are more recent build upon the ideas developed in earlier sources?

Be aware of any redundancies in your sources. If you have amassed solid support from a reputable source, such as a scholarly journal, there is no need to cite the same facts from an online encyclopedia article that is many steps removed from any primary research. If a given source adds nothing new to your discussion and you can cite a stronger source for the same information, use the stronger source.

Determine how you will address any contradictions found among different sources. For instance, if one source cites a startling fact that you cannot confirm anywhere else, it is safe to dismiss the information as unreliable. However, if you find significant disagreements among reliable sources, you will need to review them and evaluate each source. Which source presents a sounder argument or more solid evidence? It is up to you to determine which source is the most credible and why.

Finally, do not ignore any information simply because it does not support your thesis. Carefully consider how that information fits into the big picture of your research. You may decide that the source is unreliable or the information is not relevant, or you may decide that it is an important point you need to bring up. What matters is that you give it careful consideration.

As Jorge reviewed his research, he realized that some of the information was not especially useful for his purpose. His notes included several statements about the relationship between soft drinks that are high in sugar and childhood obesity—a subtopic that was too far outside of the main focus of the paper. Jorge decided to cut this material.

Reevaluate Your Working Thesis

A careful analysis of your notes will help you reevaluate your working thesis and determine whether you need to revise it. Remember that your working thesis was the starting point—not necessarily the end point—of your research. You should revise your working thesis if your ideas changed based on what you read. Even if your sources generally confirmed your preliminary thinking on the topic, it is still a good idea to tweak the wording of your thesis to incorporate the specific details you learned from research.

Jorge realized that his working thesis oversimplified the issues. He still believed that the media was exaggerating the benefits of low-carb diets. However, his research led him to conclude that these diets did have some advantages. Read Jorge’s revised thesis.

Although following a low-carbohydrate diet can benefit some people, these diets are not necessarily the best option for everyone who wants to lose weight or improve their health.

Synthesizing and Organizing Information

By now your thinking on your topic is taking shape. You have a sense of what major ideas to address in your paper, what points you can easily support, and what questions or subtopics might need a little more thought. In short, you have begun the process of synthesizing information—that is, of putting the pieces together into a coherent whole.

It is normal to find this part of the process a little difficult. Some questions or concepts may still be unclear to you. You may not yet know how you will tie all of your research together. Synthesizing information is a complex, demanding mental task, and even experienced researchers struggle with it at times. A little uncertainty is often a good sign! It means you are challenging yourself to work thoughtfully with your topic instead of simply restating the same information.

Use Your Research Questions to Synthesize Information

You have already considered how your notes fit with your working thesis. Now, take your synthesis a step further. Analyze how your notes relate to your major research question and the subquestions you identified in Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” , Section 11.2 “Steps in Developing a Research Proposal” . Organize your notes with headings that correspond to those questions. As you proceed, you might identify some important subtopics that were not part of your original plan, or you might decide that some questions are not relevant to your paper.

Categorize information carefully and continue to think critically about the material. Ask yourself whether the sources are reliable and whether the connections between ideas are clear.

Remember, your ideas and conclusions will shape the paper. They are the glue that holds the rest of the content together. As you work, begin jotting down the big ideas you will use to connect the dots for your reader. (If you are not sure where to begin, try answering your major research question and subquestions. Add and answer new questions as appropriate.) You might record these big ideas on sticky notes or type and highlight them within an electronic document.

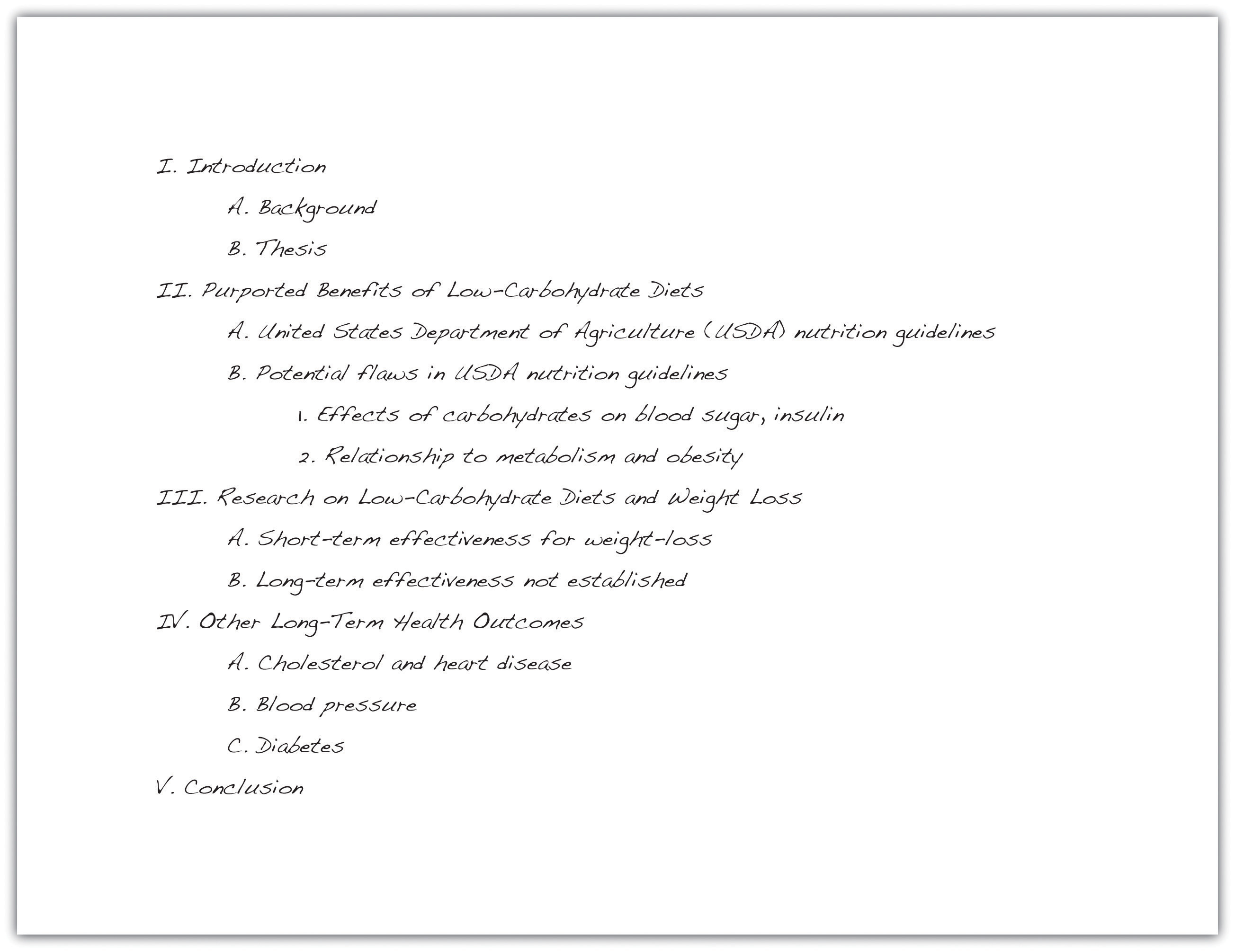

Jorge looked back on the list of research questions that he had written down earlier. He changed a few to match his new thesis, and he began a rough outline for his paper.

Review your research questions and working thesis again. This time, keep them nearby as you review your research notes.

- Identify information that supports your working thesis.

- Identify details that call your thesis into question. Determine whether you need to modify your thesis.

- Use your research questions to identify key ideas in your paper. Begin categorizing your notes according to which topics are addressed. (You may find yourself adding important topics or deleting unimportant ones as you proceed.)

- Write out your revised thesis and at least two or three big ideas.

You may be wondering how your ideas are supposed to shape the paper, especially since you are writing a research paper based on your research. Integrating your ideas and your information from research is a complex process, and sometimes it can be difficult to separate the two.

Some paragraphs in your paper will consist mostly of details from your research. That is fine, as long as you explain what those details mean or how they are linked. You should also include sentences and transitions that show the relationship between different facts from your research by grouping related ideas or pointing out connections or contrasts. The result is that you are not simply presenting information; you are synthesizing, analyzing, and interpreting it.

Plan How to Organize Your Paper

The final step to complete before beginning your draft is to choose an organizational structure. For some assignments, this may be determined by the instructor’s requirements. For instance, if you are asked to explore the impact of a new communications device, a cause-and-effect structure is obviously appropriate. In other cases, you will need to determine the structure based on what suits your topic and purpose. For more information about the structures used in writing, see Chapter 10 “Rhetorical Modes” .

The purpose of Jorge’s paper was primarily to persuade. With that in mind, he planned the following outline.

Review the organizational structures discussed in this section and Chapter 10 “Rhetorical Modes” . Working with the notes you organized earlier, follow these steps to begin planning how to organize your paper.

- Create an outline that includes your thesis, major subtopics, and supporting points.

- The major headings in your outline will become sections or paragraphs in your paper. Remember that your ideas should form the backbone of the paper. For each major section of your outline, write out a topic sentence stating the main point you will make in that section.

- As you complete step 2, you may find that some points are too complex to explain in a sentence. Consider whether any major sections of your outline need to be broken up and jot down additional topic sentences as needed.

- Review your notes and determine how the different pieces of information fit into your outline as supporting points.

Collaboration

Please share the outline you created with a classmate. Examine your classmate’s outline and see if any questions come to mind or if you see any area that would benefit from an additional point or clarification. Return the outlines to each other and compare observations.

The structures described in this section and Chapter 10 “Rhetorical Modes” can also help you organize information in different types of workplace documents. For instance, medical incident reports and police reports follow a chronological structure. If the company must choose between two vendors to provide a service, you might write an e-mail to your supervisor comparing and contrasting the choices. Understanding when and how to use each organizational structure can help you write workplace documents efficiently and effectively.

Key Takeaways

- An effective research paper focuses on presenting the writer’s ideas using information from research as support.

- Effective writers spend time reviewing, synthesizing, and organizing their research notes before they begin drafting a research paper.

- It is important for writers to revisit their research questions and working thesis as they transition from the research phase to the writing phrase of a project. Usually, the working thesis will need at least minor adjustments.

- To organize a research paper, writers choose a structure that is appropriate for the topic and purpose. Longer papers may make use of more than one structure.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

LBST 2301 (SOCY): Critical Thinking & Communication - Karen Cushing

- How to Develop a Research Question

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Popular vs. Scholarly Resources

- Annotated Bibliography

- Citing Your Sources

Developing a Research Question

Developing Strong Research Questions

A good research question is essential to guide your research paper, project or thesis. It pinpoints exactly what you want to find out and gives your work a clear focus and purpose. All research questions should be:

- Focused on a single problem or issue

- Researchable using primary and/or secondary sources

- Feasible to answer within the timeframe and practical constraints

- Specific enough to answer thoroughly

- Complex enough to develop the answer over the space of a paper or thesis

- Relevant to your field of study and/or society more broadly

In a research paper or essay, you will usually write a single research question to guide your reading and thinking. The answer that you develop is your thesis statement — the central assertion or position that your paper will argue for.

In a bigger research project, such as a thesis or dissertation, you might have multiple research questions, but they should all be clearly connected and focused around a central research problem.

From: Scribbr

How to Write a Research Question

How to write a research question.

The process of developing your research question follows several steps:

- Choose a broad topic

- Do some preliminary reading to find out about topical debates and issues

- Narrow down a specific niche that you want to focus on

- Identify a practical or theoretical research problem that you will address

When you have a clearly-defined problem, you need to formulate one or more questions. Think about exactly what you want to know and how it will contribute to resolving the problem.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Writing a Research Proposal >>

- Last Updated: May 15, 2024 1:18 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.charlotte.edu/c.php?g=1218501

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- CBE Life Sci Educ

- v.17(1); Spring 2018

Understanding the Complex Relationship between Critical Thinking and Science Reasoning among Undergraduate Thesis Writers

Jason e. dowd.

† Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708

Robert J. Thompson, Jr.

‡ Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708

Leslie A. Schiff

§ Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455

Julie A. Reynolds

Associated data.

This study empirically examines the relationship between students’ critical-thinking skills and scientific reasoning as reflected in undergraduate thesis writing in biology. Writing offers a unique window into studying this relationship, and the findings raise potential implications for instruction.

Developing critical-thinking and scientific reasoning skills are core learning objectives of science education, but little empirical evidence exists regarding the interrelationships between these constructs. Writing effectively fosters students’ development of these constructs, and it offers a unique window into studying how they relate. In this study of undergraduate thesis writing in biology at two universities, we examine how scientific reasoning exhibited in writing (assessed using the Biology Thesis Assessment Protocol) relates to general and specific critical-thinking skills (assessed using the California Critical Thinking Skills Test), and we consider implications for instruction. We find that scientific reasoning in writing is strongly related to inference , while other aspects of science reasoning that emerge in writing (epistemological considerations, writing conventions, etc.) are not significantly related to critical-thinking skills. Science reasoning in writing is not merely a proxy for critical thinking. In linking features of students’ writing to their critical-thinking skills, this study 1) provides a bridge to prior work suggesting that engagement in science writing enhances critical thinking and 2) serves as a foundational step for subsequently determining whether instruction focused explicitly on developing critical-thinking skills (particularly inference ) can actually improve students’ scientific reasoning in their writing.

INTRODUCTION

Critical-thinking and scientific reasoning skills are core learning objectives of science education for all students, regardless of whether or not they intend to pursue a career in science or engineering. Consistent with the view of learning as construction of understanding and meaning ( National Research Council, 2000 ), the pedagogical practice of writing has been found to be effective not only in fostering the development of students’ conceptual and procedural knowledge ( Gerdeman et al. , 2007 ) and communication skills ( Clase et al. , 2010 ), but also scientific reasoning ( Reynolds et al. , 2012 ) and critical-thinking skills ( Quitadamo and Kurtz, 2007 ).

Critical thinking and scientific reasoning are similar but different constructs that include various types of higher-order cognitive processes, metacognitive strategies, and dispositions involved in making meaning of information. Critical thinking is generally understood as the broader construct ( Holyoak and Morrison, 2005 ), comprising an array of cognitive processes and dispostions that are drawn upon differentially in everyday life and across domains of inquiry such as the natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities. Scientific reasoning, then, may be interpreted as the subset of critical-thinking skills (cognitive and metacognitive processes and dispositions) that 1) are involved in making meaning of information in scientific domains and 2) support the epistemological commitment to scientific methodology and paradigm(s).

Although there has been an enduring focus in higher education on promoting critical thinking and reasoning as general or “transferable” skills, research evidence provides increasing support for the view that reasoning and critical thinking are also situational or domain specific ( Beyer et al. , 2013 ). Some researchers, such as Lawson (2010) , present frameworks in which science reasoning is characterized explicitly in terms of critical-thinking skills. There are, however, limited coherent frameworks and empirical evidence regarding either the general or domain-specific interrelationships of scientific reasoning, as it is most broadly defined, and critical-thinking skills.

The Vision and Change in Undergraduate Biology Education Initiative provides a framework for thinking about these constructs and their interrelationship in the context of the core competencies and disciplinary practice they describe ( American Association for the Advancement of Science, 2011 ). These learning objectives aim for undergraduates to “understand the process of science, the interdisciplinary nature of the new biology and how science is closely integrated within society; be competent in communication and collaboration; have quantitative competency and a basic ability to interpret data; and have some experience with modeling, simulation and computational and systems level approaches as well as with using large databases” ( Woodin et al. , 2010 , pp. 71–72). This framework makes clear that science reasoning and critical-thinking skills play key roles in major learning outcomes; for example, “understanding the process of science” requires students to engage in (and be metacognitive about) scientific reasoning, and having the “ability to interpret data” requires critical-thinking skills. To help students better achieve these core competencies, we must better understand the interrelationships of their composite parts. Thus, the next step is to determine which specific critical-thinking skills are drawn upon when students engage in science reasoning in general and with regard to the particular scientific domain being studied. Such a determination could be applied to improve science education for both majors and nonmajors through pedagogical approaches that foster critical-thinking skills that are most relevant to science reasoning.

Writing affords one of the most effective means for making thinking visible ( Reynolds et al. , 2012 ) and learning how to “think like” and “write like” disciplinary experts ( Meizlish et al. , 2013 ). As a result, student writing affords the opportunities to both foster and examine the interrelationship of scientific reasoning and critical-thinking skills within and across disciplinary contexts. The purpose of this study was to better understand the relationship between students’ critical-thinking skills and scientific reasoning skills as reflected in the genre of undergraduate thesis writing in biology departments at two research universities, the University of Minnesota and Duke University.

In the following subsections, we discuss in greater detail the constructs of scientific reasoning and critical thinking, as well as the assessment of scientific reasoning in students’ thesis writing. In subsequent sections, we discuss our study design, findings, and the implications for enhancing educational practices.

Critical Thinking

The advances in cognitive science in the 21st century have increased our understanding of the mental processes involved in thinking and reasoning, as well as memory, learning, and problem solving. Critical thinking is understood to include both a cognitive dimension and a disposition dimension (e.g., reflective thinking) and is defined as “purposeful, self-regulatory judgment which results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference, as well as explanation of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations upon which that judgment is based” ( Facione, 1990, p. 3 ). Although various other definitions of critical thinking have been proposed, researchers have generally coalesced on this consensus: expert view ( Blattner and Frazier, 2002 ; Condon and Kelly-Riley, 2004 ; Bissell and Lemons, 2006 ; Quitadamo and Kurtz, 2007 ) and the corresponding measures of critical-thinking skills ( August, 2016 ; Stephenson and Sadler-McKnight, 2016 ).

Both the cognitive skills and dispositional components of critical thinking have been recognized as important to science education ( Quitadamo and Kurtz, 2007 ). Empirical research demonstrates that specific pedagogical practices in science courses are effective in fostering students’ critical-thinking skills. Quitadamo and Kurtz (2007) found that students who engaged in a laboratory writing component in the context of a general education biology course significantly improved their overall critical-thinking skills (and their analytical and inference skills, in particular), whereas students engaged in a traditional quiz-based laboratory did not improve their critical-thinking skills. In related work, Quitadamo et al. (2008) found that a community-based inquiry experience, involving inquiry, writing, research, and analysis, was associated with improved critical thinking in a biology course for nonmajors, compared with traditionally taught sections. In both studies, students who exhibited stronger presemester critical-thinking skills exhibited stronger gains, suggesting that “students who have not been explicitly taught how to think critically may not reach the same potential as peers who have been taught these skills” ( Quitadamo and Kurtz, 2007 , p. 151).

Recently, Stephenson and Sadler-McKnight (2016) found that first-year general chemistry students who engaged in a science writing heuristic laboratory, which is an inquiry-based, writing-to-learn approach to instruction ( Hand and Keys, 1999 ), had significantly greater gains in total critical-thinking scores than students who received traditional laboratory instruction. Each of the four components—inquiry, writing, collaboration, and reflection—have been linked to critical thinking ( Stephenson and Sadler-McKnight, 2016 ). Like the other studies, this work highlights the value of targeting critical-thinking skills and the effectiveness of an inquiry-based, writing-to-learn approach to enhance critical thinking. Across studies, authors advocate adopting critical thinking as the course framework ( Pukkila, 2004 ) and developing explicit examples of how critical thinking relates to the scientific method ( Miri et al. , 2007 ).

In these examples, the important connection between writing and critical thinking is highlighted by the fact that each intervention involves the incorporation of writing into science, technology, engineering, and mathematics education (either alone or in combination with other pedagogical practices). However, critical-thinking skills are not always the primary learning outcome; in some contexts, scientific reasoning is the primary outcome that is assessed.

Scientific Reasoning

Scientific reasoning is a complex process that is broadly defined as “the skills involved in inquiry, experimentation, evidence evaluation, and inference that are done in the service of conceptual change or scientific understanding” ( Zimmerman, 2007 , p. 172). Scientific reasoning is understood to include both conceptual knowledge and the cognitive processes involved with generation of hypotheses (i.e., inductive processes involved in the generation of hypotheses and the deductive processes used in the testing of hypotheses), experimentation strategies, and evidence evaluation strategies. These dimensions are interrelated, in that “experimentation and inference strategies are selected based on prior conceptual knowledge of the domain” ( Zimmerman, 2000 , p. 139). Furthermore, conceptual and procedural knowledge and cognitive process dimensions can be general and domain specific (or discipline specific).

With regard to conceptual knowledge, attention has been focused on the acquisition of core methodological concepts fundamental to scientists’ causal reasoning and metacognitive distancing (or decontextualized thinking), which is the ability to reason independently of prior knowledge or beliefs ( Greenhoot et al. , 2004 ). The latter involves what Kuhn and Dean (2004) refer to as the coordination of theory and evidence, which requires that one question existing theories (i.e., prior knowledge and beliefs), seek contradictory evidence, eliminate alternative explanations, and revise one’s prior beliefs in the face of contradictory evidence. Kuhn and colleagues (2008) further elaborate that scientific thinking requires “a mature understanding of the epistemological foundations of science, recognizing scientific knowledge as constructed by humans rather than simply discovered in the world,” and “the ability to engage in skilled argumentation in the scientific domain, with an appreciation of argumentation as entailing the coordination of theory and evidence” ( Kuhn et al. , 2008 , p. 435). “This approach to scientific reasoning not only highlights the skills of generating and evaluating evidence-based inferences, but also encompasses epistemological appreciation of the functions of evidence and theory” ( Ding et al. , 2016 , p. 616). Evaluating evidence-based inferences involves epistemic cognition, which Moshman (2015) defines as the subset of metacognition that is concerned with justification, truth, and associated forms of reasoning. Epistemic cognition is both general and domain specific (or discipline specific; Moshman, 2015 ).

There is empirical support for the contributions of both prior knowledge and an understanding of the epistemological foundations of science to scientific reasoning. In a study of undergraduate science students, advanced scientific reasoning was most often accompanied by accurate prior knowledge as well as sophisticated epistemological commitments; additionally, for students who had comparable levels of prior knowledge, skillful reasoning was associated with a strong epistemological commitment to the consistency of theory with evidence ( Zeineddin and Abd-El-Khalick, 2010 ). These findings highlight the importance of the need for instructional activities that intentionally help learners develop sophisticated epistemological commitments focused on the nature of knowledge and the role of evidence in supporting knowledge claims ( Zeineddin and Abd-El-Khalick, 2010 ).

Scientific Reasoning in Students’ Thesis Writing

Pedagogical approaches that incorporate writing have also focused on enhancing scientific reasoning. Many rubrics have been developed to assess aspects of scientific reasoning in written artifacts. For example, Timmerman and colleagues (2011) , in the course of describing their own rubric for assessing scientific reasoning, highlight several examples of scientific reasoning assessment criteria ( Haaga, 1993 ; Tariq et al. , 1998 ; Topping et al. , 2000 ; Kelly and Takao, 2002 ; Halonen et al. , 2003 ; Willison and O’Regan, 2007 ).

At both the University of Minnesota and Duke University, we have focused on the genre of the undergraduate honors thesis as the rhetorical context in which to study and improve students’ scientific reasoning and writing. We view the process of writing an undergraduate honors thesis as a form of professional development in the sciences (i.e., a way of engaging students in the practices of a community of discourse). We have found that structured courses designed to scaffold the thesis-writing process and promote metacognition can improve writing and reasoning skills in biology, chemistry, and economics ( Reynolds and Thompson, 2011 ; Dowd et al. , 2015a , b ). In the context of this prior work, we have defined scientific reasoning in writing as the emergent, underlying construct measured across distinct aspects of students’ written discussion of independent research in their undergraduate theses.

The Biology Thesis Assessment Protocol (BioTAP) was developed at Duke University as a tool for systematically guiding students and faculty through a “draft–feedback–revision” writing process, modeled after professional scientific peer-review processes ( Reynolds et al. , 2009 ). BioTAP includes activities and worksheets that allow students to engage in critical peer review and provides detailed descriptions, presented as rubrics, of the questions (i.e., dimensions, shown in Table 1 ) upon which such review should focus. Nine rubric dimensions focus on communication to the broader scientific community, and four rubric dimensions focus on the accuracy and appropriateness of the research. These rubric dimensions provide criteria by which the thesis is assessed, and therefore allow BioTAP to be used as an assessment tool as well as a teaching resource ( Reynolds et al. , 2009 ). Full details are available at www.science-writing.org/biotap.html .

Theses assessment protocol dimensions

In previous work, we have used BioTAP to quantitatively assess students’ undergraduate honors theses and explore the relationship between thesis-writing courses (or specific interventions within the courses) and the strength of students’ science reasoning in writing across different science disciplines: biology ( Reynolds and Thompson, 2011 ); chemistry ( Dowd et al. , 2015b ); and economics ( Dowd et al. , 2015a ). We have focused exclusively on the nine dimensions related to reasoning and writing (questions 1–9), as the other four dimensions (questions 10–13) require topic-specific expertise and are intended to be used by the student’s thesis supervisor.

Beyond considering individual dimensions, we have investigated whether meaningful constructs underlie students’ thesis scores. We conducted exploratory factor analysis of students’ theses in biology, economics, and chemistry and found one dominant underlying factor in each discipline; we termed the factor “scientific reasoning in writing” ( Dowd et al. , 2015a , b , 2016 ). That is, each of the nine dimensions could be understood as reflecting, in different ways and to different degrees, the construct of scientific reasoning in writing. The findings indicated evidence of both general and discipline-specific components to scientific reasoning in writing that relate to epistemic beliefs and paradigms, in keeping with broader ideas about science reasoning discussed earlier. Specifically, scientific reasoning in writing is more strongly associated with formulating a compelling argument for the significance of the research in the context of current literature in biology, making meaning regarding the implications of the findings in chemistry, and providing an organizational framework for interpreting the thesis in economics. We suggested that instruction, whether occurring in writing studios or in writing courses to facilitate thesis preparation, should attend to both components.

Research Question and Study Design

The genre of thesis writing combines the pedagogies of writing and inquiry found to foster scientific reasoning ( Reynolds et al. , 2012 ) and critical thinking ( Quitadamo and Kurtz, 2007 ; Quitadamo et al. , 2008 ; Stephenson and Sadler-McKnight, 2016 ). However, there is no empirical evidence regarding the general or domain-specific interrelationships of scientific reasoning and critical-thinking skills, particularly in the rhetorical context of the undergraduate thesis. The BioTAP studies discussed earlier indicate that the rubric-based assessment produces evidence of scientific reasoning in the undergraduate thesis, but it was not designed to foster or measure critical thinking. The current study was undertaken to address the research question: How are students’ critical-thinking skills related to scientific reasoning as reflected in the genre of undergraduate thesis writing in biology? Determining these interrelationships could guide efforts to enhance students’ scientific reasoning and writing skills through focusing instruction on specific critical-thinking skills as well as disciplinary conventions.