Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Doing Survey Research | A Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Doing Survey Research | A Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 10 October 2022.

Survey research means collecting information about a group of people by asking them questions and analysing the results. To conduct an effective survey, follow these six steps:

- Determine who will participate in the survey

- Decide the type of survey (mail, online, or in-person)

- Design the survey questions and layout

- Distribute the survey

- Analyse the responses

- Write up the results

Surveys are a flexible method of data collection that can be used in many different types of research .

Table of contents

What are surveys used for, step 1: define the population and sample, step 2: decide on the type of survey, step 3: design the survey questions, step 4: distribute the survey and collect responses, step 5: analyse the survey results, step 6: write up the survey results, frequently asked questions about surveys.

Surveys are used as a method of gathering data in many different fields. They are a good choice when you want to find out about the characteristics, preferences, opinions, or beliefs of a group of people.

Common uses of survey research include:

- Social research: Investigating the experiences and characteristics of different social groups

- Market research: Finding out what customers think about products, services, and companies

- Health research: Collecting data from patients about symptoms and treatments

- Politics: Measuring public opinion about parties and policies

- Psychology: Researching personality traits, preferences, and behaviours

Surveys can be used in both cross-sectional studies , where you collect data just once, and longitudinal studies , where you survey the same sample several times over an extended period.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Before you start conducting survey research, you should already have a clear research question that defines what you want to find out. Based on this question, you need to determine exactly who you will target to participate in the survey.

Populations

The target population is the specific group of people that you want to find out about. This group can be very broad or relatively narrow. For example:

- The population of Brazil

- University students in the UK

- Second-generation immigrants in the Netherlands

- Customers of a specific company aged 18 to 24

- British transgender women over the age of 50

Your survey should aim to produce results that can be generalised to the whole population. That means you need to carefully define exactly who you want to draw conclusions about.

It’s rarely possible to survey the entire population of your research – it would be very difficult to get a response from every person in Brazil or every university student in the UK. Instead, you will usually survey a sample from the population.

The sample size depends on how big the population is. You can use an online sample calculator to work out how many responses you need.

There are many sampling methods that allow you to generalise to broad populations. In general, though, the sample should aim to be representative of the population as a whole. The larger and more representative your sample, the more valid your conclusions.

There are two main types of survey:

- A questionnaire , where a list of questions is distributed by post, online, or in person, and respondents fill it out themselves

- An interview , where the researcher asks a set of questions by phone or in person and records the responses

Which type you choose depends on the sample size and location, as well as the focus of the research.

Questionnaires

Sending out a paper survey by post is a common method of gathering demographic information (for example, in a government census of the population).

- You can easily access a large sample.

- You have some control over who is included in the sample (e.g., residents of a specific region).

- The response rate is often low.

Online surveys are a popular choice for students doing dissertation research , due to the low cost and flexibility of this method. There are many online tools available for constructing surveys, such as SurveyMonkey and Google Forms .

- You can quickly access a large sample without constraints on time or location.

- The data is easy to process and analyse.

- The anonymity and accessibility of online surveys mean you have less control over who responds.

If your research focuses on a specific location, you can distribute a written questionnaire to be completed by respondents on the spot. For example, you could approach the customers of a shopping centre or ask all students to complete a questionnaire at the end of a class.

- You can screen respondents to make sure only people in the target population are included in the sample.

- You can collect time- and location-specific data (e.g., the opinions of a shop’s weekday customers).

- The sample size will be smaller, so this method is less suitable for collecting data on broad populations.

Oral interviews are a useful method for smaller sample sizes. They allow you to gather more in-depth information on people’s opinions and preferences. You can conduct interviews by phone or in person.

- You have personal contact with respondents, so you know exactly who will be included in the sample in advance.

- You can clarify questions and ask for follow-up information when necessary.

- The lack of anonymity may cause respondents to answer less honestly, and there is more risk of researcher bias.

Like questionnaires, interviews can be used to collect quantitative data : the researcher records each response as a category or rating and statistically analyses the results. But they are more commonly used to collect qualitative data : the interviewees’ full responses are transcribed and analysed individually to gain a richer understanding of their opinions and feelings.

Next, you need to decide which questions you will ask and how you will ask them. It’s important to consider:

- The type of questions

- The content of the questions

- The phrasing of the questions

- The ordering and layout of the survey

Open-ended vs closed-ended questions

There are two main forms of survey questions: open-ended and closed-ended. Many surveys use a combination of both.

Closed-ended questions give the respondent a predetermined set of answers to choose from. A closed-ended question can include:

- A binary answer (e.g., yes/no or agree/disagree )

- A scale (e.g., a Likert scale with five points ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree )

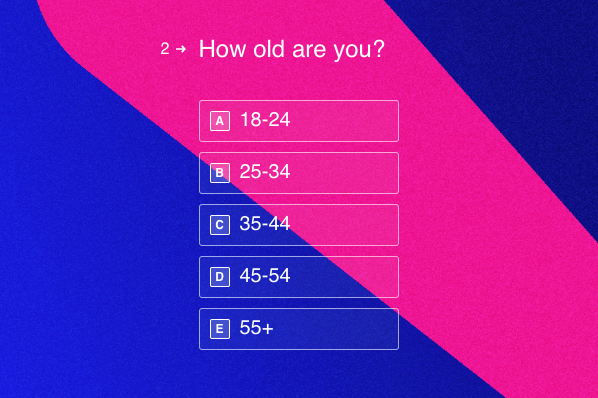

- A list of options with a single answer possible (e.g., age categories)

- A list of options with multiple answers possible (e.g., leisure interests)

Closed-ended questions are best for quantitative research . They provide you with numerical data that can be statistically analysed to find patterns, trends, and correlations .

Open-ended questions are best for qualitative research. This type of question has no predetermined answers to choose from. Instead, the respondent answers in their own words.

Open questions are most common in interviews, but you can also use them in questionnaires. They are often useful as follow-up questions to ask for more detailed explanations of responses to the closed questions.

The content of the survey questions

To ensure the validity and reliability of your results, you need to carefully consider each question in the survey. All questions should be narrowly focused with enough context for the respondent to answer accurately. Avoid questions that are not directly relevant to the survey’s purpose.

When constructing closed-ended questions, ensure that the options cover all possibilities. If you include a list of options that isn’t exhaustive, you can add an ‘other’ field.

Phrasing the survey questions

In terms of language, the survey questions should be as clear and precise as possible. Tailor the questions to your target population, keeping in mind their level of knowledge of the topic.

Use language that respondents will easily understand, and avoid words with vague or ambiguous meanings. Make sure your questions are phrased neutrally, with no bias towards one answer or another.

Ordering the survey questions

The questions should be arranged in a logical order. Start with easy, non-sensitive, closed-ended questions that will encourage the respondent to continue.

If the survey covers several different topics or themes, group together related questions. You can divide a questionnaire into sections to help respondents understand what is being asked in each part.

If a question refers back to or depends on the answer to a previous question, they should be placed directly next to one another.

Before you start, create a clear plan for where, when, how, and with whom you will conduct the survey. Determine in advance how many responses you require and how you will gain access to the sample.

When you are satisfied that you have created a strong research design suitable for answering your research questions, you can conduct the survey through your method of choice – by post, online, or in person.

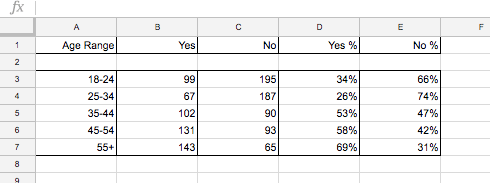

There are many methods of analysing the results of your survey. First you have to process the data, usually with the help of a computer program to sort all the responses. You should also cleanse the data by removing incomplete or incorrectly completed responses.

If you asked open-ended questions, you will have to code the responses by assigning labels to each response and organising them into categories or themes. You can also use more qualitative methods, such as thematic analysis , which is especially suitable for analysing interviews.

Statistical analysis is usually conducted using programs like SPSS or Stata. The same set of survey data can be subject to many analyses.

Finally, when you have collected and analysed all the necessary data, you will write it up as part of your thesis, dissertation , or research paper .

In the methodology section, you describe exactly how you conducted the survey. You should explain the types of questions you used, the sampling method, when and where the survey took place, and the response rate. You can include the full questionnaire as an appendix and refer to it in the text if relevant.

Then introduce the analysis by describing how you prepared the data and the statistical methods you used to analyse it. In the results section, you summarise the key results from your analysis.

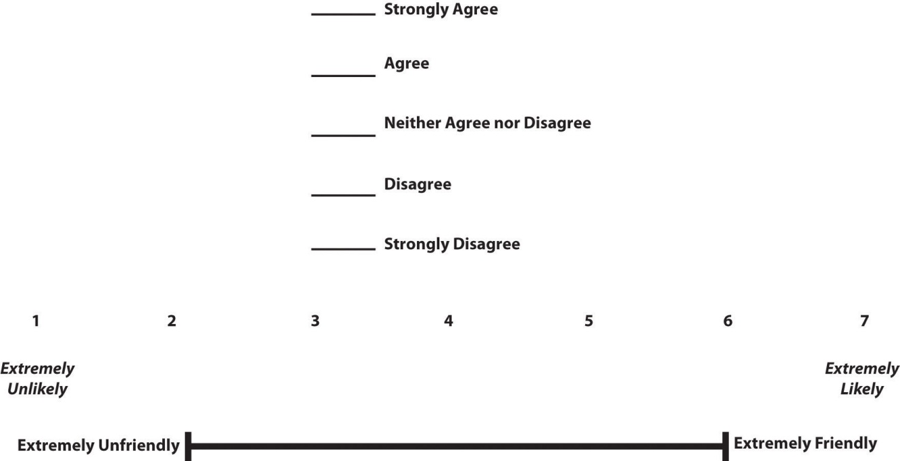

A Likert scale is a rating scale that quantitatively assesses opinions, attitudes, or behaviours. It is made up of four or more questions that measure a single attitude or trait when response scores are combined.

To use a Likert scale in a survey , you present participants with Likert-type questions or statements, and a continuum of items, usually with five or seven possible responses, to capture their degree of agreement.

Individual Likert-type questions are generally considered ordinal data , because the items have clear rank order, but don’t have an even distribution.

Overall Likert scale scores are sometimes treated as interval data. These scores are considered to have directionality and even spacing between them.

The type of data determines what statistical tests you should use to analyse your data.

A questionnaire is a data collection tool or instrument, while a survey is an overarching research method that involves collecting and analysing data from people using questionnaires.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, October 10). Doing Survey Research | A Step-by-Step Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 14 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/surveys/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, qualitative vs quantitative research | examples & methods, construct validity | definition, types, & examples, what is a likert scale | guide & examples.

Dissertation & Thesis Survey Design 101

5 Common Mistakes To Avoid (+ Examples)

By: David Phair (PhD) & Kerryn Warren (PhD) | April 2022

Surveys are a powerful way to collect data for your dissertation, thesis or research project. Done right, a good survey allows you to collect large swathes of useful data with (relatively) little effort. However, if not designed well, you can run into serious issues.

Over the years, we’ve encountered numerous common mistakes students make when it comes to survey design. In this post, we’ll unpack five of these costly mistakes.

Overview: 5 Survey Design Mistakes

- Having poor overall survey structure and flow

- Using poorly constructed questions and/or statements

- Implementing inappropriate response types

- Using unreliable and/or invalid scales and measures

- Designing without consideration for analysis techniques

Mistake #1: Having poor structure and flow

One of the most common issues we see is poor overall survey structure and flow . If a survey is designed badly, it will discourage participants from completing it. As a result, few participants will take the time to respond to the survey, which can lead to a small sample size and poor or even unusable results . Let’s look at a few best practices to ensure good overall structure and flow.

1. Make sure your survey is aligned with your study’s “golden thread”.

The first step might seem obvious, but it’s important to develop survey questions that are tightly aligned with your research question(s), aims and objectives – in other words, “your golden thread”. Your survey serves to generate the data that will answer these key ideas in your thesis; if it doesn’t do that, you’ve got a serious problem. To put it simply, it’s critically important to design your survey questions with the golden thread of your study front of mind at all times.

2. Order your questions in an intuitive, logical way.

The types of questions you ask and when you ask them are vital aspects when designing an effective survey. To avoid losing respondents, you need to order your questions clearly and logically.

In general, it’s a good idea to ask exclusion questions upfront . For example, if your research is focused on an aspect of women’s lives, your first question should be one to determine the gender of the respondent (and filter out unsuitable respondents). Once that’s out of the way, the exclusion questions can be followed by questions related to the key constructs or ideas and/or the dependent and independent variables in your study.

Lastly, the demographics-related questions are usually positioned at the end of the survey. These are questions related to the characteristics of your respondents (e.g., age, race, occupation). It’s a good idea to position these questions at the end of your survey because respondents can get caught up in these identity-related questions as they move through the rest of your survey. Placing them at the end of your survey helps ensure that the questions related to the core constructs of your study will have the respondents’ full attention.

3. Design for user experience and ease of use.

This might seem obvious, but it’s essential to carefully consider your respondents’ “journey” when designing your survey. In other words, you need to keep user experience and engagement front of mind when designing your survey.

One way of creating a good user experience is to have a clear introduction or cover page upfront. On this intro page, it’s good to communicate the estimated time required to complete the survey (generally, 15 to 20 minutes is reasonable). Also, make u se of headings and short explainers to help respondents understand the context of each question or section in your survey. It’s also helpful if you provide a progress indicator to indicate how far they are in completing the survey.

Naturally, readability is important to a successful survey. So, keep the survey content as concise as possible, as people tend to drop out of long surveys. A general rule of thumb is to make use of plain, easy-to-understand language . Related to this, always carefully edit and proofread your survey before launching it. Typos, grammar and formatting issues will heavily detract from the credibility of your work and will likely increase respondent dropout.

In cases where you have no choice but to use a technical term or industry jargon, be sure to explain the meaning (define the term) first. You don’t want respondents to be distracted or confused by the technical aspects of your survey. In addition to this, create a logical flow by grouping related topics together and moving from general to more specific questions.

You should also think about what devices respondents will use to access your survey. Because many people use their phones to complete your survey, making it mobile-friendly means more people will be able to respond, which is hugely beneficial. By hosting your survey on a trusted provider (e.g., SurveyMonkey or Qualtrix), the mobile aspect should be taken care of, but always test your survey on a few devices. Aside from making the data collection easier, using a well-established survey platform will also make processing your survey data easier.

4. Prioritise ethics and data privacy.

The last (and very important) point to consider when designing your survey is the ethical requirements. Your survey design must adhere to all ethics policies and data protection laws of your country. If you (or your respondents) are in Europe for instance, you’ll need to comply with GDPR. It’s also essential to highlight to your respondents that all data collected will be handled and stored securely , to minimise any concerns about the confidentiality and safety of their data.

Mistake #2: Using poorly constructed questions

Another common survey design issue we encounter is poorly constructed questions and statements. There are a few ways in which questions can be poorly constructed. These usually fall into four broad categories:

- Loaded questions

- Leading questions

- Double-barreled questions

- Vague questions

Let’s look at each of these.

A loaded question assumes something about the respondent without having any data to support that assumption. For example, if the question asks, “Where is your favourite place to eat steak?”, it assumes that the respondent eats steak. Clearly, this is problematic for respondents that are vegetarians or vegans, or people that simply don’t like steak.

A leading question pushes the respondent to answer in a certain way. For example, a question such as, “How would you rate the excellent service at our restaurant?” is trying to influence the way that the respondent thinks about the service at the restaurant. This can be annoying to the respondent (at best) or lead them to respond in a way they wouldn’t have, had the question been more objective.

Need a helping hand?

A double-barreled question is a question that contains two (or more) variables within it. It essentially tries to ask two questions at the same time. An example of this is

“ Do you enjoy eating peanut butter and cheese on bread?”

As you can see, this question makes it unclear whether you are being asked about whether they like eating the two together on bread, or whether they like eating one at a time. This is problematic, as there are multiple ways to interpret this question, which means that the resultant data will be unusable.

A vague question , as the name suggests, is one where it is unclear what is being asked or one that is very open-ended . Of course, sometimes you do indeed want open questions, as they can provide richer information from respondents. However, if you ask a vague question, you’ll likely get a vague answer. So, you need to be careful. Consider the following fairly vague question:

“What was your experience at this restaurant?”.

A respondent could answer this question by just saying “good” or “bad” – or nothing at all. This isn’t particularly helpful. Alternatively, someone might respond extensively about something unrelated to the question. If you want to ask open-ended questions, interviewing may be a better (or additional) data method to consider, so give some thought to what you’re trying to achieve. Only use open-ended questions in a survey if they’re central to your research aims .

To make sure that your questions don’t fall into one of these problematic categories, it’s important to keep your golden thread (i.e., your research aims, objectives and research questions ) in mind and consider the type of data you want to generate. Also, it’s always a good idea to make use of a pilot study to test your survey questions and responses to see whether any questions are problematic and whether the data generated is useful.

Mistake #3: Using inappropriate response types

When designing your survey, it’s essential to choose the best-suited response type/format for each question. In other words, you need to consider how the respondents will input their responses into your survey. Broadly speaking, there are three response types .

The first response type is categorical.

These are questions where the respondent will choose one of the pre-determined options that you provide, for example: yes/no, gender, ethnicity, etc.

For categorical responses, there will be a limited number of choices and respondents will only be able to pick one. This is useful for basic demographic data where all potential responses can be easily grouped into categories.

The second response type is scales .

Scales offer respondents the opportunity to express their opinion on a spectrum . For example, you could design a 3-point scale with the options of agree, neutral and disagree. Scales are useful when you’re trying to assess the extent to which respondents agree with specific statements or claims. This data can then be statistically analysed in powerful ways.

Scales can, however, be problematic if they have too many or too few points . For example, if you only have “strongly agree”, “neutral” and “strongly disagree”, your respondent might resort to selecting “neutral” because they don’t feel strongly about the subject. Conversely, if there are too many points on the scale, your respondents might take too much time to complete the survey and become frustrated in the process of agonising over what exactly they feel.

The third response type is the free form text box (open-ended response).

We mentioned open-ended questions earlier and looked at some of the ways in which they can be problematic. But, because free-form responses are useful for understanding nuances and finer details, this response type does have its benefits. For example, some respondents might have a problem with how the other questions in your survey are presented or asked, and therefore an open-ended response option gives them an opportunity to respond in a way that reflects their true feelings.

As you can see, it’s important to carefully consider which response types you use, as each one has its own purpose, pros and cons . Make sure that each response option is appropriate for the type of question and generates data that you will be able to analyse in a meaningful way.

It’s also good to keep in mind that you as the researcher will need to process all the data generated by the survey. Therefore, you need to consider how you will analyse the data from each response type. Use the response type that makes sense for the specific question and keep the analysis aspect in mind when choosing your response types.

Mistake #4: Using poorly design scales/measures

We’ve spoken about the design of the survey as a whole, but it’s also important to think carefully about the design of individual measures/scales. Theoretical constructs are typically measured using Likert scales. To measure these constructs effectively, you’ll need to ensure that your scales produce valid and reliable data.

Validity refers to whether the scale measures what you’re trying to measure . This might sound like a no-brainer, but oftentimes people can interpret questions or statements in diverse ways. Therefore, it’s important to think of whether the interpretations of the responses to each measure are sound relative to the original construct you are measuring and the existing literature relating to it.

Reliability, on the other hand, is related to whether multiple scales measuring the same construct get the same response (on average, of course). In other words, if you have three scales measuring employee satisfaction, they should correlate, as they all measure the same construct. A good survey should make use of multiple scales to measure any given construct, and these should “move” together – in other words, be “reliable”.

If you’re designing a survey, you’ll need to demonstrate the validity and reliability of your measures. This can be done in several ways, using both statistical and non-statistical techniques. We won’t get into detail about those here, but it’s important to remember that validity and reliability are central to making sure that your survey is measuring what it is meant to measure.

Importantly, when thinking about the scales for your survey, you don’t need to reinvent the wheel. There are pre-developed and tested scales available for most areas of research, and it’s preferable to use a “tried and tested” scale, rather than developing one from scratch. If there isn’t already something that fits your research, you can often modify existing scales to suit your specific needs.

Mistake #5: Not designing with analysis in mind

Naturally, you’ll want to use the data gathered from your survey as effectively as possible. Therefore, it’s always a good idea to start with the end (i.e., the analysis phase) in mind when designing your survey. The analysis methods that you’ll be able to use in your study will be dictated by the design of the survey, as it will produce certain types of data. Therefore, it’s essential that you design your survey in a way that will allow you to undertake the analyses you need to achieve your research aims.

Importantly, you should have a clear idea of what statistical methods you plan to use before you start designing your survey. Be clear about which specific descriptive and inferential tests you plan to do (and why). Make sure that you understand the assumptions of all the statistical tests you’ll be using and the type of data (i.e., nominal, ordinal, interval, or ratio ) that each test requires. Only once you have that level of clarity can you get started designing your survey.

Finally, and as we’ve emphasized before, it’s essential that you keep your study’s golden thread front of mind during the design process. If your analysis methods don’t aid you in answering your research questions, they’ll be largely useless. So, keep the big picture and the end goal front of mind from the outset.

Recap: Survey Design Mistakes

In this post we’ve discussed some important aspects of survey design and five common mistakes to avoid while designing your own survey. To recap, these include:

If you have any questions about these survey design mistakes, drop a comment below. Alternatively, if you’re interested in getting 1-on-1 help with your research , check out our dissertation coaching service or book a free initial consultation with a friendly coach.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

Thank you much for this article. I really appreciate it.

Please do you handle someone’s project write up or you can guide someone through out the project write up?

Very useful and understandable for a user like me. I thank you very much !!

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Adv Pract Oncol

- v.6(2); Mar-Apr 2015

Understanding and Evaluating Survey Research

A variety of methodologic approaches exist for individuals interested in conducting research. Selection of a research approach depends on a number of factors, including the purpose of the research, the type of research questions to be answered, and the availability of resources. The purpose of this article is to describe survey research as one approach to the conduct of research so that the reader can critically evaluate the appropriateness of the conclusions from studies employing survey research.

SURVEY RESEARCH

Survey research is defined as "the collection of information from a sample of individuals through their responses to questions" ( Check & Schutt, 2012, p. 160 ). This type of research allows for a variety of methods to recruit participants, collect data, and utilize various methods of instrumentation. Survey research can use quantitative research strategies (e.g., using questionnaires with numerically rated items), qualitative research strategies (e.g., using open-ended questions), or both strategies (i.e., mixed methods). As it is often used to describe and explore human behavior, surveys are therefore frequently used in social and psychological research ( Singleton & Straits, 2009 ).

Information has been obtained from individuals and groups through the use of survey research for decades. It can range from asking a few targeted questions of individuals on a street corner to obtain information related to behaviors and preferences, to a more rigorous study using multiple valid and reliable instruments. Common examples of less rigorous surveys include marketing or political surveys of consumer patterns and public opinion polls.

Survey research has historically included large population-based data collection. The primary purpose of this type of survey research was to obtain information describing characteristics of a large sample of individuals of interest relatively quickly. Large census surveys obtaining information reflecting demographic and personal characteristics and consumer feedback surveys are prime examples. These surveys were often provided through the mail and were intended to describe demographic characteristics of individuals or obtain opinions on which to base programs or products for a population or group.

More recently, survey research has developed into a rigorous approach to research, with scientifically tested strategies detailing who to include (representative sample), what and how to distribute (survey method), and when to initiate the survey and follow up with nonresponders (reducing nonresponse error), in order to ensure a high-quality research process and outcome. Currently, the term "survey" can reflect a range of research aims, sampling and recruitment strategies, data collection instruments, and methods of survey administration.

Given this range of options in the conduct of survey research, it is imperative for the consumer/reader of survey research to understand the potential for bias in survey research as well as the tested techniques for reducing bias, in order to draw appropriate conclusions about the information reported in this manner. Common types of error in research, along with the sources of error and strategies for reducing error as described throughout this article, are summarized in the Table .

Sources of Error in Survey Research and Strategies to Reduce Error

The goal of sampling strategies in survey research is to obtain a sufficient sample that is representative of the population of interest. It is often not feasible to collect data from an entire population of interest (e.g., all individuals with lung cancer); therefore, a subset of the population or sample is used to estimate the population responses (e.g., individuals with lung cancer currently receiving treatment). A large random sample increases the likelihood that the responses from the sample will accurately reflect the entire population. In order to accurately draw conclusions about the population, the sample must include individuals with characteristics similar to the population.

It is therefore necessary to correctly identify the population of interest (e.g., individuals with lung cancer currently receiving treatment vs. all individuals with lung cancer). The sample will ideally include individuals who reflect the intended population in terms of all characteristics of the population (e.g., sex, socioeconomic characteristics, symptom experience) and contain a similar distribution of individuals with those characteristics. As discussed by Mady Stovall beginning on page 162, Fujimori et al. ( 2014 ), for example, were interested in the population of oncologists. The authors obtained a sample of oncologists from two hospitals in Japan. These participants may or may not have similar characteristics to all oncologists in Japan.

Participant recruitment strategies can affect the adequacy and representativeness of the sample obtained. Using diverse recruitment strategies can help improve the size of the sample and help ensure adequate coverage of the intended population. For example, if a survey researcher intends to obtain a sample of individuals with breast cancer representative of all individuals with breast cancer in the United States, the researcher would want to use recruitment strategies that would recruit both women and men, individuals from rural and urban settings, individuals receiving and not receiving active treatment, and so on. Because of the difficulty in obtaining samples representative of a large population, researchers may focus the population of interest to a subset of individuals (e.g., women with stage III or IV breast cancer). Large census surveys require extremely large samples to adequately represent the characteristics of the population because they are intended to represent the entire population.

DATA COLLECTION METHODS

Survey research may use a variety of data collection methods with the most common being questionnaires and interviews. Questionnaires may be self-administered or administered by a professional, may be administered individually or in a group, and typically include a series of items reflecting the research aims. Questionnaires may include demographic questions in addition to valid and reliable research instruments ( Costanzo, Stawski, Ryff, Coe, & Almeida, 2012 ; DuBenske et al., 2014 ; Ponto, Ellington, Mellon, & Beck, 2010 ). It is helpful to the reader when authors describe the contents of the survey questionnaire so that the reader can interpret and evaluate the potential for errors of validity (e.g., items or instruments that do not measure what they are intended to measure) and reliability (e.g., items or instruments that do not measure a construct consistently). Helpful examples of articles that describe the survey instruments exist in the literature ( Buerhaus et al., 2012 ).

Questionnaires may be in paper form and mailed to participants, delivered in an electronic format via email or an Internet-based program such as SurveyMonkey, or a combination of both, giving the participant the option to choose which method is preferred ( Ponto et al., 2010 ). Using a combination of methods of survey administration can help to ensure better sample coverage (i.e., all individuals in the population having a chance of inclusion in the sample) therefore reducing coverage error ( Dillman, Smyth, & Christian, 2014 ; Singleton & Straits, 2009 ). For example, if a researcher were to only use an Internet-delivered questionnaire, individuals without access to a computer would be excluded from participation. Self-administered mailed, group, or Internet-based questionnaires are relatively low cost and practical for a large sample ( Check & Schutt, 2012 ).

Dillman et al. ( 2014 ) have described and tested a tailored design method for survey research. Improving the visual appeal and graphics of surveys by using a font size appropriate for the respondents, ordering items logically without creating unintended response bias, and arranging items clearly on each page can increase the response rate to electronic questionnaires. Attending to these and other issues in electronic questionnaires can help reduce measurement error (i.e., lack of validity or reliability) and help ensure a better response rate.

Conducting interviews is another approach to data collection used in survey research. Interviews may be conducted by phone, computer, or in person and have the benefit of visually identifying the nonverbal response(s) of the interviewee and subsequently being able to clarify the intended question. An interviewer can use probing comments to obtain more information about a question or topic and can request clarification of an unclear response ( Singleton & Straits, 2009 ). Interviews can be costly and time intensive, and therefore are relatively impractical for large samples.

Some authors advocate for using mixed methods for survey research when no one method is adequate to address the planned research aims, to reduce the potential for measurement and non-response error, and to better tailor the study methods to the intended sample ( Dillman et al., 2014 ; Singleton & Straits, 2009 ). For example, a mixed methods survey research approach may begin with distributing a questionnaire and following up with telephone interviews to clarify unclear survey responses ( Singleton & Straits, 2009 ). Mixed methods might also be used when visual or auditory deficits preclude an individual from completing a questionnaire or participating in an interview.

FUJIMORI ET AL.: SURVEY RESEARCH

Fujimori et al. ( 2014 ) described the use of survey research in a study of the effect of communication skills training for oncologists on oncologist and patient outcomes (e.g., oncologist’s performance and confidence and patient’s distress, satisfaction, and trust). A sample of 30 oncologists from two hospitals was obtained and though the authors provided a power analysis concluding an adequate number of oncologist participants to detect differences between baseline and follow-up scores, the conclusions of the study may not be generalizable to a broader population of oncologists. Oncologists were randomized to either an intervention group (i.e., communication skills training) or a control group (i.e., no training).

Fujimori et al. ( 2014 ) chose a quantitative approach to collect data from oncologist and patient participants regarding the study outcome variables. Self-report numeric ratings were used to measure oncologist confidence and patient distress, satisfaction, and trust. Oncologist confidence was measured using two instruments each using 10-point Likert rating scales. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was used to measure patient distress and has demonstrated validity and reliability in a number of populations including individuals with cancer ( Bjelland, Dahl, Haug, & Neckelmann, 2002 ). Patient satisfaction and trust were measured using 0 to 10 numeric rating scales. Numeric observer ratings were used to measure oncologist performance of communication skills based on a videotaped interaction with a standardized patient. Participants completed the same questionnaires at baseline and follow-up.

The authors clearly describe what data were collected from all participants. Providing additional information about the manner in which questionnaires were distributed (i.e., electronic, mail), the setting in which data were collected (e.g., home, clinic), and the design of the survey instruments (e.g., visual appeal, format, content, arrangement of items) would assist the reader in drawing conclusions about the potential for measurement and nonresponse error. The authors describe conducting a follow-up phone call or mail inquiry for nonresponders, using the Dillman et al. ( 2014 ) tailored design for survey research follow-up may have reduced nonresponse error.

CONCLUSIONS

Survey research is a useful and legitimate approach to research that has clear benefits in helping to describe and explore variables and constructs of interest. Survey research, like all research, has the potential for a variety of sources of error, but several strategies exist to reduce the potential for error. Advanced practitioners aware of the potential sources of error and strategies to improve survey research can better determine how and whether the conclusions from a survey research study apply to practice.

The author has no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Faculty and researchers : We want to hear from you! We are launching a survey to learn more about your library collection needs for teaching, learning, and research. If you would like to participate, please complete the survey by May 17, 2024. Thank you for your participation!

- University of Massachusetts Lowell

- University Libraries

Survey Research: Design and Presentation

- Planning a Thesis Proposal

- Introduction to Survey Research Design

- Literature Review: Definition and Context

- Slides, Articles

- Evaluating Survey Results

- Related Library Databases

The goal of a proposal is to demonstrate that you are ready to start your research project by presenting a distinct idea, question or issue which has great interest for you, along with the method you have chosen to explore it.

The process of developing your research question is related to the literature review. As you discover more from your research, your question will be shaped by what you find.

The clarity of your idea dictates the plan for your dissertation or thesis work.

From the University of North Texas faculty member Dr. Abraham Benavides:

Elements of a Thesis Proposal

(Adapted from the Department of Communication, University of Washington)

Dissertation proposals vary but most share the following elements, though not necessarily in this order.

1. The Introduction

In three paragraphs to three or four pages very simply introduce your question. Use a narrative to style to engage readers. A well-known issue in your field, controversy surrounding some texts, or the policy implications of your topic are some ways to add context to the proposal.

2. Research Questions

State your question early in your proposal. Even if you are going to restate your research questionas part of the literature review, you may wish to mention it briefly at the end of the introduction.

Make sure if you have questions which follow from your main question that this is clearly indicated. The research questions should include any boundaries you have placed on your inquiry, for instance time, place, and topics. Terms with unusual meanings should be defined.

3. Literature Synthesis or Review

The proposal must be described within the broader body of scholarship around the topic. This is part of establishing the significance of your research. The discussion of the literature typically shows how your project will extend what’s already known.

In writing your literature review, think about the important theories and concepts related to your project and organize your discussion accordingly; you usually want to avoid a strictly chronological discussion (i.e., earliest study, next study, etc.).

What research is directly related to your topic? Discuss it thoroughly.

What literature provides context for your research? Discuss it briefly.

In your proposal you should avoid writing a genealogy of your field’s research. For instance, you don’t need to tell your committee about the development of research in the entire field in order to justify the particular project you propose. Instead, isolate the major areas of research within your field that are relevant to your project.

4. Significance of your Research Question

Good proposals leave readers with a clear understanding of the dissertation project’s overall significance. Consider the following:

- advancing theoretical understandings

- introducing new interpretations

- analyzing the relationship between variables

- testing a theory

- replicating earlier studies

- exploring the whether earlier findings can be demonstrated to hold true in new times, places, or circumstances

- refining a method of inquiry.

5. Research Method

The research method that will be used involves three levels of concern:

- overall research design

- delineation of the method

- procedures for executing it.

At the outset you have to show that your overall design is appropriate for the questions you’re posing.

Next, you need to outline your specific research method. What data will you analyze?

How will you collect the data? Supervisors sometimes expect proposals to sketch instruments (e.g., coding sheets, questionnaires, protocols) central to the project.

Third, what procedures will you follow as you conduct your research? What will you do with your data? A key here is your plan for analyzing data. You want to gather data in a form in which you can analyze it. [In this case the method is a survey administered to a group of people]. If appropriate, you should indicate what rules for interpretation or what kinds of statistical tests that you’ll use.

6. Tentative Dissertation Outline

Give your committee a sense of how your thesis will be organized. You can write a short (two- or three-sentence) paragraph summarizing what you expect to include in each section of the thesis.

7. Tentative Schedule for Completion

Be realistic in projecting your timeline. Don’t forget to include time for human subjects review, if appropriate .

8. References

If you didn’t use footnotes or endnotes throughout, you should include a list of references to the literature cited in the proposal.

9. Selected Bibliography of Other Sources

You might want to append a more extensive bibliography (check with your supervisor). If you include one, you might want to divide it into several subsections, for instance by concept, topic or field.

- << Previous: Introduction to Survey Research Design

- Next: Literature Review: Definition and Context >>

- Last Updated: Jan 22, 2024 2:05 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uml.edu/rohland_surveys

How to Write an Impressive Thesis Results Section

After collecting and analyzing your research data, it’s time to write the results section. This article explains how to write and organize the thesis results section, the differences in reporting qualitative and quantitative data, the differences in the thesis results section across different fields, and the best practices for tables and figures.

What is the thesis results section?

The thesis results section factually and concisely describes what was observed and measured during the study but does not interpret the findings. It presents the findings in a logical order.

What should the thesis results section include?

- Include all relevant results as text, tables, or figures

- Report the results of subject recruitment and data collection

- For qualitative research, present the data from all statistical analyses, whether or not the results are significant

- For quantitative research, present the data by coding or categorizing themes and topics

- Present all secondary findings (e.g., subgroup analyses)

- Include all results, even if they do not fit in with your assumptions or support your hypothesis

What should the thesis results section not include?

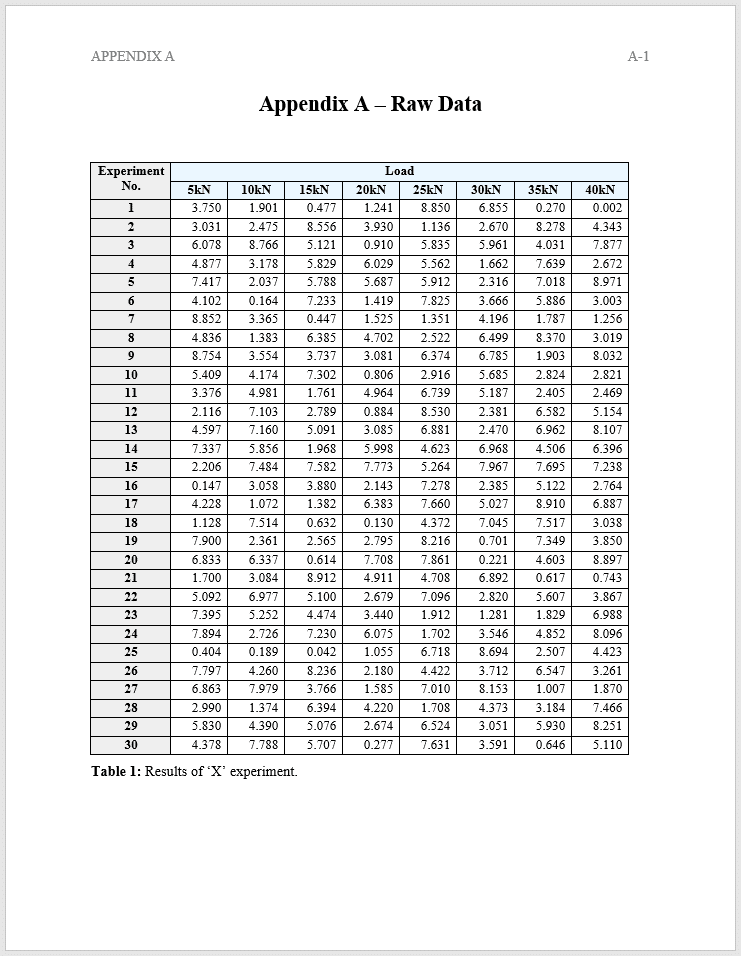

- If the study involves the thematic analysis of an interview, don’t include complete transcripts of all interviews. Instead, add these as appendices

- Don’t present raw data. These may be included in appendices

- Don’t include background information (this should be in the introduction section )

- Don’t speculate on the meaning of results that do not support your hypothesis. This will be addressed later in the discussion and conclusion sections.

- Don’t repeat results that have been presented in tables and figures. Only highlight the pertinent points or elaborate on specific aspects

How should the thesis results section be organized?

The opening paragraph of the thesis results section should briefly restate the thesis question. Then, present the results objectively as text, figures, or tables.

Quantitative research presents the results from experiments and statistical tests , usually in the form of tables and figures (graphs, diagrams, and images), with any pertinent findings emphasized in the text. The results are structured around the thesis question. Demographic data are usually presented first in this section.

For each statistical test used, the following information must be mentioned:

- The type of analysis used (e.g., Mann–Whitney U test or multiple regression analysis)

- A concise summary of each result, including descriptive statistics (e.g., means, medians, and modes) and inferential statistics (e.g., correlation, regression, and p values) and whether the results are significant

- Any trends or differences identified through comparisons

- How the findings relate to your research and if they support or contradict your hypothesis

Qualitative research presents results around key themes or topics identified from your data analysis and explains how these themes evolved. The data are usually presented as text because it is hard to present the findings as figures.

For each theme presented, describe:

- General trends or patterns observed

- Significant or representative responses

- Relevant quotations from your study subjects

Relevant characteristics about your study subjects

Differences among the results section in different fields of research

Nevertheless, results should be presented logically across all disciplines and reflect the thesis question and any hypotheses that were tested.

The presentation of results varies considerably across disciplines. For example, a thesis documenting how a particular population interprets a specific event and a thesis investigating customer service may both have collected data using interviews and analyzed it using similar methods. Still, the presentation of the results will vastly differ because they are answering different thesis questions. A science thesis may have used experiments to generate data, and these would be presented differently again, probably involving statistics. Nevertheless, results should be presented logically across all disciplines and reflect the thesis question and any hypotheses that were tested.

Differences between reporting thesis results in the Sciences and the Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS) domains

In the Sciences domain (qualitative and experimental research), the results and discussion sections are considered separate entities, and the results from experiments and statistical tests are presented. In the HSS domain (qualitative research), the results and discussion sections may be combined.

There are two approaches to presenting results in the HSS field:

- If you want to highlight important findings, first present a synopsis of the results and then explain the key findings.

- If you have multiple results of equal significance, present one result and explain it. Then present another result and explain that, and so on. Conclude with an overall synopsis.

Best practices for using tables and figures

The use of figures and tables is highly encouraged because they provide a standalone overview of the research findings that are much easier to understand than wading through dry text mentioning one result after another. The text in the results section should not repeat the information presented in figures and tables. Instead, it should focus on the pertinent findings or elaborate on specific points.

Some popular software programs that can be used for the analysis and presentation of statistical data include Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS ) , R software , MATLAB , Microsoft Excel, Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) , GraphPad Prism , and Minitab .

The easiest way to construct tables is to use the Table function in Microsoft Word . Microsoft Excel can also be used; however, Word is the easier option.

General guidelines for figures and tables

- Figures and tables must be interpretable independent from the text

- Number tables and figures consecutively (in separate lists) in the order in which they are mentioned in the text

- All tables and figures must be cited in the text

- Provide clear, descriptive titles for all figures and tables

- Include a legend to concisely describe what is presented in the figure or table

Figure guidelines

- Label figures so that the reader can easily understand what is being shown

- Use a consistent font type and font size for all labels in figure panels

- All abbreviations used in the figure artwork should be defined in the figure legend

Table guidelines

- All table columns should have a heading abbreviation used in tables should be defined in the table footnotes

- All numbers and text presented in tables must correlate with the data presented in the manuscript body

Quantitative results example : Figure 3 presents the characteristics of unemployed subjects and their rate of criminal convictions. A statistically significant association was observed between unemployed people <20 years old, the male sex, and no household income.

Qualitative results example: Table 5 shows the themes identified during the face-to-face interviews about the application that we developed to anonymously report corruption in the workplace. There was positive feedback on the app layout and ease of use. Concerns that emerged from the interviews included breaches of confidentiality and the inability to report incidents because of unstable cellphone network coverage.

Table 5. Themes and selected quotes from the evaluation of our app designed to anonymously report workplace corruption.

Tips for writing the thesis results section

- Do not state that a difference was present between the two groups unless this can be supported by a significant p-value .

- Present the findings only . Do not comment or speculate on their interpretation.

- Every result included must have a corresponding method in the methods section. Conversely, all methods must have associated results presented in the results section.

- Do not explain commonly used methods. Instead, cite a reference.

- Be consistent with the units of measurement used in your thesis study. If you start with kg, then use the same unit all throughout your thesis. Also, be consistent with the capitalization of units of measurement. For example, use either “ml” or “mL” for milliliters, but not both.

- Never manipulate measurement outcomes, even if the result is unexpected. Remain objective.

Results vs. discussion vs. conclusion

Results are presented in three sections of your thesis: the results, discussion, and conclusion.

- In the results section, the data are presented simply and objectively. No speculation or interpretation is given.

- In the discussion section, the meaning of the results is interpreted and put into context (e.g., compared with other findings in the literature ), and its importance is assigned.

- In the conclusion section, the results and the main conclusions are summarized.

A thesis is the most crucial document that you will write during your academic studies. For professional thesis editing and thesis proofreading services , visit Enago Thesis Editing for more information.

Editor’s pick

Get free updates.

Subscribe to our newsletter for regular insights from the research and publishing industry!

Review Checklist

Have you completed all data collection procedures and analyzed all results ?

Have you included all results relevant to your thesis question, even if they do not support your hypothesis?

Have you reported the results objectively , with no interpretation or speculation?

For quantitative research, have you included both descriptive and inferential statistical results and stated whether they support or contradict your hypothesis?

Have you used tables and figures to present all results?

In your thesis body, have you presented only the pertinent results and elaborated on specific aspects that were presented in the tables and figures?

Are all tables and figures correctly labeled and cited in numerical order in the text?

Frequently Asked Questions

What file formats do you accept +.

We accept all file formats, including Microsoft Word, Microsoft Excel, PDF, Latex, etc.

How to identify whether paraphrasing is required? +

We provide a report entailing recommendations for a single Plagiarism Check service. You can also write to us at [email protected] for further assistance as paraphrasing is sold offline and has a relatively high conversion in most geographies.

What information do i need to provide? +

Please upload your research manuscript when you place the order. If you want to include the tables, charts, and figure legends in the plagiarism check, please ensure that all content is in editable formats and in one single document.

Is repetition percentage of 25-30% considered acceptable by the journal for my manuscript? +

Acceptable repetition rate varies by journal but aim for low percentages (usually <5%). Avoid plagiarism, cite sources, and use detection tools. High plagiarism can lead to rejection, reputation damage, and serious consequences. Consult your institution for guidance on addressing plagiarism concerns.

Do you offer help to rewrite and paraphrase the plagiarized text in my manuscript? +

We can certainly help you rewrite and paraphrase text in your manuscript to ensure it is not plagiarized under our Developmental Content rewriting service. You can provide specific passages or sentences that you suspect may be plagiarized, and we can assist you in rephrasing them to ensure originality.

Which international languages does iThenticate have content for in its database? +

iThenticate searches for content matches in the following 30 languages: Chinese (Simplified and Traditional), Japanese, Thai, Korean, Catalan, Croatian, Czech, Danish, Dutch, Finnish, French, German, Hungarian, Italian, Norwegian (Bokmal, Nynorsk), Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Serbian, Slovak, Slovenian, Spanish, Swedish, Arabic, Greek, Hebrew, Farsi, Russian, and Turkish. Please note that iThenticate will match your text with text of the same language.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 9: Survey Research

Constructing Survey Questionnaires

Learning Objectives

- Describe the cognitive processes involved in responding to a survey item.

- Explain what a context effect is and give some examples.

- Create a simple survey questionnaire based on principles of effective item writing and organization.

The heart of any survey research project is the survey questionnaire itself. Although it is easy to think of interesting questions to ask people, constructing a good survey questionnaire is not easy at all. The problem is that the answers people give can be influenced in unintended ways by the wording of the items, the order of the items, the response options provided, and many other factors. At best, these influences add noise to the data. At worst, they result in systematic biases and misleading results. In this section, therefore, we consider some principles for constructing survey questionnaires to minimize these unintended effects and thereby maximize the reliability and validity of respondents’ answers.

Survey Responding as a Psychological Process

Before looking at specific principles of survey questionnaire construction, it will help to consider survey responding as a psychological process.

A Cognitive Model

Figure 9.1 presents a model of the cognitive processes that people engage in when responding to a survey item (Sudman, Bradburn, & Schwarz, 1996) [1] . Respondents must interpret the question, retrieve relevant information from memory, form a tentative judgment, convert the tentative judgment into one of the response options provided (e.g., a rating on a 1-to-7 scale), and finally edit their response as necessary.

Consider, for example, the following questionnaire item:

How many alcoholic drinks do you consume in a typical day?

- _____ a lot more than average

- _____ somewhat more than average

- _____ average

- _____ somewhat fewer than average

- _____ a lot fewer than average

Although this item at first seems straightforward, it poses several difficulties for respondents. First, they must interpret the question. For example, they must decide whether “alcoholic drinks” include beer and wine (as opposed to just hard liquor) and whether a “typical day” is a typical weekday, typical weekend day, or both . Even though Chang and Krosnick (2003) [2] found that asking about “typical” behaviour has been shown to be more valid than asking about “past” behaviour, their study compared “typical week” to “past week” and may be different when considering typical weekdays or weekend days) . Once they have interpreted the question, they must retrieve relevant information from memory to answer it. But what information should they retrieve, and how should they go about retrieving it? They might think vaguely about some recent occasions on which they drank alcohol, they might carefully try to recall and count the number of alcoholic drinks they consumed last week, or they might retrieve some existing beliefs that they have about themselves (e.g., “I am not much of a drinker”). Then they must use this information to arrive at a tentative judgment about how many alcoholic drinks they consume in a typical day. For example, this mental calculation might mean dividing the number of alcoholic drinks they consumed last week by seven to come up with an average number per day. Then they must format this tentative answer in terms of the response options actually provided. In this case, the options pose additional problems of interpretation. For example, what does “average” mean, and what would count as “somewhat more” than average? Finally, they must decide whether they want to report the response they have come up with or whether they want to edit it in some way. For example, if they believe that they drink much more than average, they might not want to report th e higher number for fear of looking bad in the eyes of the researcher.

From this perspective, what at first appears to be a simple matter of asking people how much they drink (and receiving a straightforward answer from them) turns out to be much more complex.

Context Effects on Questionnaire Responses

Again, this complexity can lead to unintended influences on respondents’ answers. These are often referred to as context effects because they are not related to the content of the item but to the context in which the item appears (Schwarz & Strack, 1990) [3] . For example, there is an item-order effect when the order in which the items are presented affects people’s responses. One item can change how participants interpret a later item or change the information that they retrieve to respond to later items. For example, researcher Fritz Strack and his colleagues asked college students about both their general life satisfaction and their dating frequency (Strack, Martin, & Schwarz, 1988) [4] . When the life satisfaction item came first, the correlation between the two was only −.12, suggesting that the two variables are only weakly related. But when the dating frequency item came first, the correlation between the two was +.66, suggesting that those who date more have a strong tendency to be more satisfied with their lives. Reporting the dating frequency first made that information more accessible in memory so that they were more likely to base their life satisfaction rating on it.

The response options provided can also have unintended effects on people’s responses (Schwarz, 1999) [5] . For example, when people are asked how often they are “really irritated” and given response options ranging from “less than once a year” to “more than once a month,” they tend to think of major irritations and report being irritated infrequently. But when they are given response options ranging from “less than once a day” to “several times a month,” they tend to think of minor irritations and report being irritated frequently. People also tend to assume that middle response options represent what is normal or typical. So if they think of themselves as normal or typical, they tend to choose middle response options. For example, people are likely to report watching more television when the response options are centred on a middle option of 4 hours than when centred on a middle option of 2 hours. To mitigate against order effects, rotate questions and response items when there is no natural order. Counterbalancing is a good practice for survey questions and can reduce response order effects which show that among undecided voters, the first candidate listed in a ballot receives a 2.5% boost simply by virtue of being listed first [6] !

Writing Survey Questionnaire Items

Types of items.

Questionnaire items can be either open-ended or closed-ended. Open-ended items simply ask a question and allow participants to answer in whatever way they choose. The following are examples of open-ended questionnaire items.

- “What is the most important thing to teach children to prepare them for life?”

- “Please describe a time when you were discriminated against because of your age.”

- “Is there anything else you would like to tell us about?”

Open-ended items are useful when researchers do not know how participants might respond or want to avoid influencing their responses. They tend to be used when researchers have more vaguely defined research questions—often in the early stages of a research project. Open-ended items are relatively easy to write because there are no response options to worry about. However, they take more time and effort on the part of participants, and they are more difficult for the researcher to analy z e because the answers must be transcribed, coded, and submitted to some form of qualitative analysis, such as content analysis. The advantage to open-ended items is that they are unbiased and do not provide respondents with expectations of what the researcher might be looking for. Open-ended items are also more valid and more reliable. The disadvantage is that respondents are more likely to skip open-ended items because they take longer to answer. It is best to use open-ended questions when the answer is unsure and for quantities which can easily be converted to categories later in the analysis.

Closed-ended items ask a question and provide a set of response options for participants to choose from. The alcohol item just mentioned is an example, as are the following:

How old are you?

- _____ Under 18

- _____ 18 to 34

- _____ 35 to 49

- _____ 50 to 70

- _____ Over 70

On a scale of 0 (no pain at all) to 10 (worst pain ever experienced), how much pain are you in right now?

Have you ever in your adult life been depressed for a period of 2 weeks or more?

Closed-ended items are used when researchers have a good idea of the different responses that participants might make. They are also used when researchers are interested in a well-defined variable or construct such as participants’ level of agreement with some statement, perceptions of risk, or frequency of a particular behaviour. Closed-ended items are more difficult to write because they must include an appropriate set of response options. However, they are relatively quick and easy for participants to complete. They are also much easier for researchers to analyze because the responses can be easily converted to numbers and entered into a spreadsheet. For these reasons, closed-ended items are much more common.

All closed-ended items include a set of response options from which a participant must choose. For categorical variables like sex, race, or political party preference, the categories are usually listed and participants choose the one (or ones) that they belong to. For quantitative variables, a rating scale is typically provided. A rating scale is an ordered set of responses that participants must choose from. Figure 9.2 shows several examples. The number of response options on a typical rating scale ranges from three to 11—although five and seven are probably most common. Five-point scales are best for unipolar scales where only one construct is tested, such as frequency (Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, Always). Seven-point scales are best for bipolar scales where there is a dichotomous spectrum, such as liking (Like very much, Like somewhat, Like slightly, Neither like nor dislike, Dislike slightly, Dislike somewhat, Dislike very much). For bipolar questions, it is useful to offer an earlier question that branches them into an area of the scale; if asking about liking ice cream, first ask “Do you generally like or dislike ice cream?” Once the respondent chooses like or dislike, refine it by offering them one of choices from the seven-point scale. Branching improves both reliability and validity (Krosnick & Berent, 1993) [7] . Although you often see scales with numerical labels, it is best to only present verbal labels to the respondents but convert them to numerical values in the analyses. Avoid partial labels or length or overly specific labels. In some cases, the verbal labels can be supplemented with (or even replaced by) meaningful graphics. The last rating scale shown in Figure 9.2 is a visual-analog scale, on which participants make a mark somewhere along the horizontal line to indicate the magnitude of their response.

What is a Likert Scale?

In reading about psychological research, you are likely to encounter the term Likert scale . Although this term is sometimes used to refer to almost any rating scale (e.g., a 0-to-10 life satisfaction scale), it has a much more precise meaning.

In the 1930s, researcher Rensis Likert (pronounced LICK-ert) created a new approach for measuring people’s attitudes (Likert, 1932) [8] . It involves presenting people with several statements—including both favourable and unfavourable statements—about some person, group, or idea. Respondents then express their agreement or disagreement with each statement on a 5-point scale: Strongly Agree , Agree , Neither Agree nor Disagree , Disagree , Strongly Disagree . Numbers are assigned to each response (with reverse coding as necessary) and then summed across all items to produce a score representing the attitude toward the person, group, or idea. The entire set of items came to be called a Likert scale.

Thus unless you are measuring people’s attitude toward something by assessing their level of agreement with several statements about it, it is best to avoid calling it a Likert scale. You are probably just using a “rating scale.”

Writing Effective Items

We can now consider some principles of writing questionnaire items that minimize unintended context effects and maximize the reliability and validity of participants’ responses. A rough guideline for writing questionnaire items is provided by the BRUSO model (Peterson, 2000) [9] . An acronym, BRUSO stands for “brief,” “relevant,” “unambiguous,” “specific,” and “objective.” Effective questionnaire items are brief and to the point. They avoid long, overly technical, or unnecessary words. This brevity makes them easier for respondents to understand and faster for them to complete. Effective questionnaire items are also relevant to the research question. If a respondent’s sexual orientation, marital status, or income is not relevant, then items on them should probably not be included. Again, this makes the questionnaire faster to complete, but it also avoids annoying respondents with what they will rightly perceive as irrelevant or even “nosy” questions. Effective questionnaire items are also unambiguous ; they can be interpreted in only one way. Part of the problem with the alcohol item presented earlier in this section is that different respondents might have different ideas about what constitutes “an alcoholic drink” or “a typical day.” Effective questionnaire items are also specific , so that it is clear to respondents what their response should be about and clear to researchers what it is about. A common problem here is closed-ended items that are “double barrelled.” They ask about two conceptually separate issues but allow only one response. For example, “Please rate the extent to which you have been feeling anxious and depressed.” This item should probably be split into two separate items—one about anxiety and one about depression. Finally, effective questionnaire items are objective in the sense that they do not reveal the researcher’s own opinions or lead participants to answer in a particular way. Table 9.2 shows some examples of poor and effective questionnaire items based on the BRUSO criteria. The best way to know how people interpret the wording of the question is to conduct pre-tests and ask a few people to explain how they interpreted the question.

For closed-ended items, it is also important to create an appropriate response scale. For categorical variables, the categories presented should generally be mutually exclusive and exhaustive. Mutually exclusive categories do not overlap. For a religion item, for example, the categories of Christian and Catholic are not mutually exclusive but Protestant and Catholic are. Exhaustive categories cover all possible responses.

Although Protestant and Catholic are mutually exclusive, they are not exhaustive because there are many other religious categories that a respondent might select: Jewish , Hindu , Buddhist , and so on. In many cases, it is not feasible to include every possible category, in which case an Other category, with a space for the respondent to fill in a more specific response, is a good solution. If respondents could belong to more than one category (e.g., race), they should be instructed to choose all categories that apply.

For rating scales, five or seven response options generally allow about as much precision as respondents are capable of. However, numerical scales with more options can sometimes be appropriate. For dimensions such as attractiveness, pain, and likelihood, a 0-to-10 scale will be familiar to many respondents and easy for them to use. Regardless of the number of response options, the most extreme ones should generally be “balanced” around a neutral or modal midpoint. An example of an unbalanced rating scale measuring perceived likelihood might look like this:

Unlikely | Somewhat Likely | Likely | Very Likely | Extremely Likely

A balanced version might look like this:

Extremely Unlikely | Somewhat Unlikely | As Likely as Not | Somewhat Likely | Extremely Likely

Note, however, that a middle or neutral response option does not have to be included. Researchers sometimes choose to leave it out because they want to encourage respondents to think more deeply about their response and not simply choose the middle option by default. Including middle alternatives on bipolar dimensions is useful to allow people to genuinely choose an option that is neither.

Formatting the Questionnaire

Writing effective items is only one part of constructing a survey questionnaire. For one thing, every survey questionnaire should have a written or spoken introduction that serves two basic functions (Peterson, 2000) [10] . One is to encourage respondents to participate in the survey. In many types of research, such encouragement is not necessary either because participants do not know they are in a study (as in naturalistic observation) or because they are part of a subject pool and have already shown their willingness to participate by signing up and showing up for the study. Survey research usually catches respondents by surprise when they answer their phone, go to their mailbox, or check their e-mail—and the researcher must make a good case for why they should agree to participate. Thus the introduction should briefly explain the purpose of the survey and its importance, provide information about the sponsor of the survey (university-based surveys tend to generate higher response rates), acknowledge the importance of the respondent’s participation, and describe any incentives for participating.