Monetary policy framework in India

- Policy Review

- Published: 23 June 2020

- Volume 55 , pages 117–154, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Pami Dua 1

47k Accesses

20 Citations

31 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

In 2016, the monetary policy framework moved towards flexible inflation targeting and a six member Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) was constituted for setting the policy rate. With this step towards modernization of the monetary policy process, India joined the set of countries that have adopted inflation targeting as their monetary policy framework. The Consumer Price Index (CPI combined) inflation target was set by the Government of India at 4% with ± 2% tolerance band for the period from August 5, 2016 to March 31, 2021. In this backdrop, the paper reviews the evolution of monetary policy frameworks in India since the mid-1980s. It also describes the monetary policy transmission process and its limitations in terms of lags and rigidities. It highlights the importance of unconventional monetary policy measures in supplementing conventional tools especially during the easing cycle. Further, it examines the voting pattern of the MPC in India and compares this with that of various developed and emerging economies. The synchronization of cuts in the policy rate by MPCs of various countries during the global slowdown in 2019 and the COVID-19 pandemic in the early 2020s is also analysed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Monetary Policy Framework in India

Monetary Policy: Global Trends and the Development of Bank of Russia’s Approaches

Inflation Targeting, Monetary Policy: The Way Forward

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The monetary policy framework in India has evolved over the past few decades in response to financial developments and changing macroeconomic conditions. The operational framework of monetary policy has also gone through significant changes with respect to instruments and targeting mechanisms. The preamble of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Act, 1934 was also amended in 2016, which now clearly provides the mandate of the RBI. It reads as follows:

“to regulate the issue of Bank notes and keeping of reserves with a view to securing monetary stability in India and generally to operate the currency and credit system of the country to its advantage; to have a modern monetary policy framework to meet the challenge of an increasingly complex economy; to maintain price stability while keeping in mind the objective of growth.”

The aim of monetary policy in the initial years of inception of RBI was mainly to maintain the sterling parity, with exchange rate being the nominal anchor of monetary policy. Liquidity was regulated through open market operations (OMOs), bank rate and cash reserve ratio (CRR). Soon after independence and through the late 1960s, the role of the central bank was aligned with the planned development process of the nation in accordance with the 5-year plans. Thus, it played a major role in regulating credit availability, employing OMOs, bank rate, and reserve requirement towards this end.

With the nationalization of major banks in 1969, the main objective of monetary policy through the 1970s till the mid-1980s was the regulation of credit in accordance with the developmental needs of the country. This period was marked by monetization of fiscal deficit while inflationary consequences of high public expenditure necessitated frequent recourse to CRR.

In 1985, on the recommendation of the Committee set up to Review the Working of the Monetary System (Chairman: Dr. Sukhamoy Chakravarty), a new monetary policy framework, monetary targeting with feedback was implemented based on empirical evidence of a stable demand for money function. However, financial innovations in the 1990s implied that demand for money may be affected by factors other than income. Further, interest rates were deregulated in the mid-1990s and the Indian economy was getting increasingly integrated with the global economy. Therefore, the RBI began to deemphasize the role of monetary aggregates and implemented a multiple indicator approach (MIA) to monetary policy in 1998 encompassing all economic and financial variables that influence the major objectives outlined in the Preamble of the RBI Act. This was done in two phases—initially MIA and later augmented MIA (AMIA) which included forward looking variables and time series models.

Based on RBI’s Report of the Expert Committee to Revise and Strengthen the Monetary Policy Framework ( 2014 , Chairman: Dr Urjit R Patel), a formal transition was made in 2016 towards flexible inflation targeting and a six member Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) was constituted for setting the policy repo rate. The Monetary Policy Framework Agreement (MPFA) was signed between the Government of India and the RBI in February 2015 to formally adopt the flexible inflation targeting (FIT) framework. This was followed up with the amendment to the RBI Act, 1934 in May 2016 to provide a statutory basis for the implementation of the FIT framework. With this step towards modernization of the monetary policy process, India joined the set of countries that adopted inflation targeting, starting from 1990 by New Zealand, as their monetary policy framework. The Central Government notified in the Official Gazette dated August 5, 2016, that the Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation target would be 4% with ± 2% tolerance band for the period from August 5, 2016 to March 31, 2021. At the time of writing (April 2020), this period is drawing to a close in less than a year. In this backdrop, this paper discusses the evolution of the monetary policy framework in India and describes the workings of the current framework.

The paper is divided into the following sections. Section 2 presents a schematic representation of the main components of a general monetary policy framework and describes its key features. Section 3 describes the genesis of the monetary policy framework in India since 1985 covering the Monetary Targeting Framework, Multiple Indicator Approach and Flexible Inflation Targeting. The main recommendations of RBI’s Report of the Expert Committee to Revise and Strengthen the Monetary Policy Framework ( 2014 , Chairman: Dr Urjit R Patel) are also discussed. Composition, workings and voting pattern of the Monetary Policy Committee from October 2016 to March 2020 are also provided. Further, a comparison of voting patterns with various countries across the globe is undertaken.

Section 4 discusses a general framework for monetary policy transmission and applies the framework to India. It also describes interest rate linkages at the global level. Section 5 examines unconventional monetary policy measures adopted in late 2019 and early 2020. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2 Schematic representation of a monetary policy framework

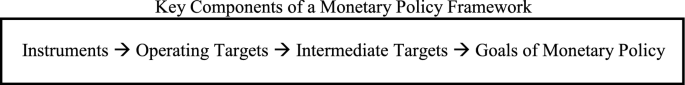

The specification of the monetary policy framework facilitates the conduct of monetary policy. The general framework comprises well-defined objectives/goals of monetary policy along with instruments, operating targets and intermediate targets that aid in the implementation of monetary policy and achievement of the ultimate objectives. A schematic representation of a monetary policy framework is shown in Fig. 1 (Laurens et al. 2015 ; Mishkin 2016 ).

Source: Author

Instruments are tools that the central bank has control over and are used to achieve the operational target. Examples of instruments include open market operations, reserve requirements, discount policy, lending to banks, policy rate. Operational targets are the financial variables that can be controlled by the central bank to a large extent through the monetary policy instruments and guide the day-to-day operations of the central bank. These can impact the intermediate target and thus help in the delivery of the final goal of monetary policy. Examples of operational targets include reserve money and short-term money market interest rates.

Intermediate targets are variables that are closely related with the final goals of monetary policy and can be affected by monetary policy. Intermediate targets may include monetary aggregates and short-term and long-term interest rates. Goals refer to the final policy objectives. These may include price stability, economic growth, financial stability and exchange rate stability.

This general framework is applied to the monetary targeting framework with feedback that prevailed from 1985 to 1998 and to the inflation targeting framework that exists from 2016 onwards. The multiple indicator approach that was operational from 1998 to 2016 was based on a number of financial and economic variables and was not exactly specified on the basis of this framework although broad money was treated as an intermediate target and the goals of monetary policy are the same across the various frameworks.

3 Genesis of monetary policy in India since 1985

3.1 monetary targeting with feedback: 1985–1998.

In the 1970s through the mid-1980s, monetization of the fiscal deficit exerted a dominant influence on monetary policy with inflationary consequences of high public expenditure necessitating frequent recourse to CRR. Against this backdrop, in 1985, on the recommendation of the Committee set up to Review the Working of the Monetary System (RBI 1985 ; Chairman: Dr. Sukhamoy Chakravarty), a new monetary policy framework, monetary targeting with feedback was implemented based on empirical evidence of a stable demand for money function. The recommendation of the committee was to control inflation within acceptable levels with desired output growth. Further, instead of following a fixed target for money supply growth, a range was followed which was subject to mid-year adjustments. This framework was termed “Monetary Targeting with Feedback” as it was flexible enough to accommodate changes in output growth.

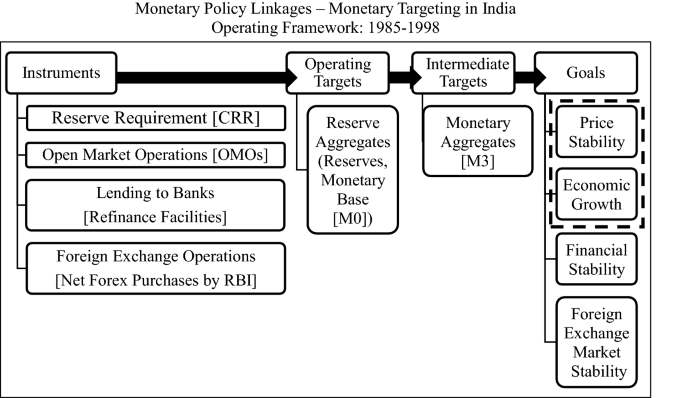

This operational framework is depicted in Fig. 2 . (Definitions of variables shown in Fig. 2 are given in Appendix 1 ). The main instruments in this framework were cash reserve ratio (CRR), open market operations (OMOs), refinance facilities and foreign exchange operations. Broad money (M3) was chosen as the intermediate target while reserve money (M0) was the main operating target. However, an analysis of money growth outcomes during the monetary targeting framework reveals that targets were rarely met (RBI 2009–2012). Even with increases in CRR, money supply growth remained high and fuelled inflation.

(1) Primary objective of monetary policy in India is to maintain price stability, while keeping in mind the objective of growth.

(2) Definitions of variables are given in Appendix 1

Further, financial innovations in the 1990s implied that demand for money may be affected by factors other than income. Since the mid-1990s, with global integration, factors such as swings in capital flows, volatility in the exchange rate and global growth also impacted the economy. Moreover, interest rates were deregulated allowing for changing interest rates and a market determined management system of exchange rates was also adopted.

3.2 Multiple Indicator Approach: 1998–2016

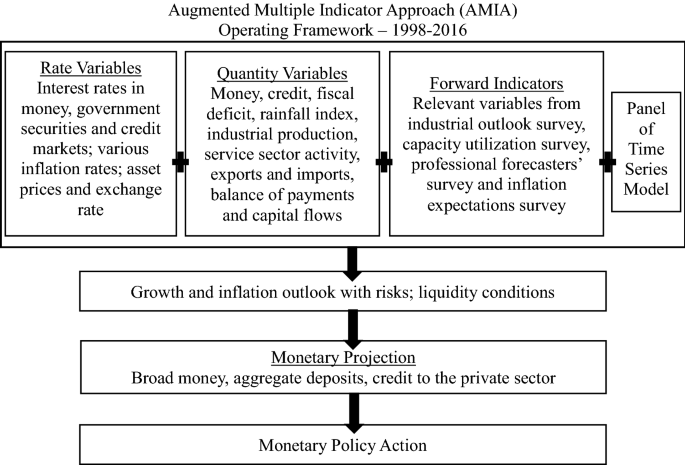

Against the backdrop of changing domestic and global dynamics, RBI implemented a multiple indicator approach (MIA) to monetary policy in 1998 encompassing various economic and financial variables based on the recommendations of RBI’s Working Group on Money Supply (RBI 1998 ; Chairman: Dr YV Reddy). These variables included several quantity variables such as money, credit, output, trade, capital flows, fiscal indicators as well as rate variables such as interest rates, inflation rate and the exchange rate. The information on these variables provided a broad-based monetary policy formulation, which not only encompassed a diverse set of information, but also accorded flexibility to the conduct of monetary management. The MIA was conceptualized when Dr Bimal Jalan was Governor and was implemented in two stages—MIA and later augmented MIA, by including forward looking variables and a panel of time series models, in addition to the economic and financial variables (Mohanty 2010 ; Reddy 1999 ). Forward looking indicators were drawn from RBI’s industrial outlook survey, capacity utilization survey, inflation expectations survey and professional forecasters’ survey. All the variables together with time series models provided the projection of growth and inflation while RBI provided the projection for broad money (M3) and treated this as the intermediate target.

The operational framework of AMIA is illustrated in Fig. 3 . Compared to the Monetary Targeting Framework, the goals of monetary policy remained the same and broad money continued to serve as the intermediate target while the underlying operating mechanism of MIA evolved over time. In May 2011, the weighted average call money rate (WACR) was explicitly recognized as the operating target of monetary policy while the repo rate was made the only one independently varying policy rate. These measures improved the implementation and transmission of monetary policy along with enhancing the accuracy of signaling of monetary policy stance (Mohanty 2011 ).

Source: RBI Bulletin, December 2011

Shift towards inflation targeting

The importance of focusing on inflation was first highlighted in the Report of the Committee on Financial Sector Reforms (Government of India 2009 ; Chairman: Dr. Raghuram Rajan) constituted by the Government of India. The report recommended that RBI can best serve the cause of growth by focusing on controlling inflation and intervening in currency markets only to limit excessive volatility. The report pointed out that the cause of inclusion can also be best served by maintaining this focus because the poorer sections are least hedged against inflation. Further, the report recommended that there should be a single objective of staying close to a low inflation number, or within a range, in the medium term, moving steadily to a single instrument, the short-term interest rate to achieve it.

Former RBI Governor, Dr. Raghuram Rajan set up an Expert Committee in 2013 to Review and Strengthen the Monetary Policy Framework (RBI 2014 ; Chairman: Dr Urjit R Patel). The mandate of the Committee, amongst others, was to review the objectives and conduct of monetary policy in a globalized and highly inter-connected environment. The committee was also required to review the organizational structure, operating framework and instruments of monetary policy, liquidity management framework, to ensure compatibility with macroeconomic and financial stability, as well as market development. The impediments to monetary policy transmission were to be identified and measures along with institutional pre-conditions to improve transmission across financial markets and real economy were to be suggested.

Some issues central to the report were selecting the nominal anchor for monetary policy, defining the inflation metric and specifying the inflation target. A nominal anchor is central to a credible monetary policy framework as it ties down the price level or the change in the price level to attain the final goal of monetary policy. It is a numerical objective that is defined for a nominal variable to signal the commitment of monetary policy towards price stability.

Generally five types of nominal anchors have been used, namely, monetary aggregates, exchange rate, inflation rate, national income and price level. The Expert Committee recommended inflation to be the nominal anchor of the monetary policy framework in India as flexible inflation targeting recognizes the existence of growth-inflation trade-off in the short-run and stabilizing and anchoring inflation expectations is critical for ensuring price stability on an enduring basis. Further, low and stable inflation is a necessary precondition for sustainable high growth and inflation is also easily understood by the public.

Regarding the inflation metric, the Committee recommended that RBI should adopt the all India CPI (combined) inflation as the measure of the nominal anchor. This is to be defined in terms of headline CPI inflation, which closely reflects the cost of living and influences inflation expectations relative to other available metrics. CPI is also easily understood as it is used as a reference in wage contracts and negotiations. Headline inflation was preferred against core inflation (headline inflation excluding food and fuel inflation) since food and fuel comprise more than 50% of the consumption basket and cannot be discarded.

The Committee recommended the target level of inflation at 4% with a band of ± 2% around it. The tolerance band was formulated in the light of the vulnerability of the Indian economy to supply and external shocks and the relatively large weight of food in the CPI basket.

The Expert Committee also recommended that decision-making should be vested in a Monetary Policy Committee (MPC).

3.3 Flexible inflation targeting: 2016 onwards

With the signing of the Monetary Policy Framework Agreement (MPFA) between the Government of India and the RBI on Feb 20, 2015, Flexible Inflation Targeting (FIT) was formally adopted in India. In May 2016, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Act, 1934 was amended to provide a statutory basis for the implementation of the FIT framework. The amended RBI Act, 1934 also provided that the Central Government shall, in consultation with the Bank, determine the inflation target in terms of the Consumer Price Index, once in every 5 years.

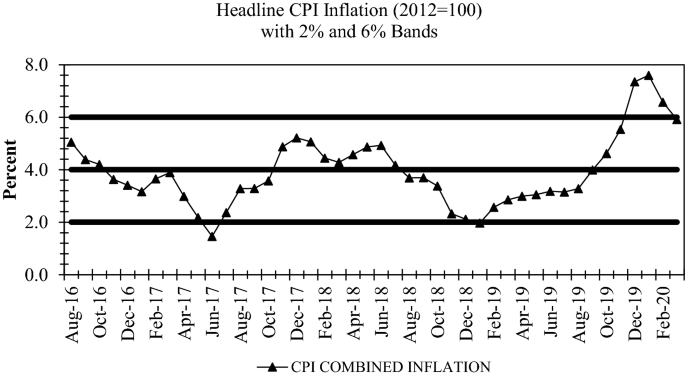

Accordingly, the Central Government has notified in the Official Gazette 4% Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation as the target for the period from August 5, 2016 to March 31, 2021 with the upper tolerance limit of 6% and the lower tolerance limit of 2%. The amended RBI Act, 1934 also provides that RBI shall be seen to have failed to meet the target if inflation remains above 6% or below 2% for three consecutive quarters. In such circumstances, RBI is required to provide the reasons for the failure, and propose remedial measures and the expected time to return inflation to the target.

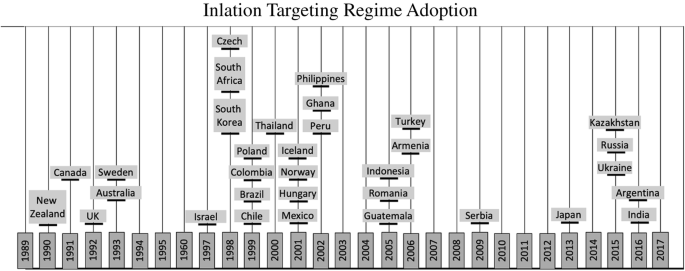

In 2016, India thus joined several developed and emerging market economies that have implemented inflation targeting. Figure 4 shows the timeline for implementation of inflation targeting for countries in this category, starting in 1990.

Source: Centre for Central Banking Studies (2012), Bank for International Settlements (2017), Russian Journal of Economics (2017), The Economist (2016), Central Bank websites of Kazakhstan and Ukraine

Monetary Policy Committee: composition, monetary policy framework and voting patterns

The amended RBI Act, 1934 provides for a statutory and institutionalized framework for a six-member Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) to be constituted by the Central Government by notification in the Official Gazette. The Central Government in September 2016 thus constituted the MPC with three members from RBI including the Governor as Chairperson and three external members as per Gazette Notification dated September 29, 2016. (Details of the composition of MPC are given in Appendix 3 ). The Committee is required to meet at least four times a year although it has been meeting on a bi-monthly basis since October 2016. Each member of the MPC has one vote, and in the event of equality of votes, the Governor has a second or casting vote. The resolution adopted by the MPC is published after conclusion of every meeting of the MPC. On the 14th day, the minutes of the proceedings of the MPC are published which includes the resolution adopted by the MPC, the vote of each member on the resolution, and the statement of each member on the resolution.

It may be noted that before the constitution of the MPC, a Technical Advisory Committee (TAC) on Monetary Policy was set up in 2005 which consisted of external experts from monetary economics, central banking, financial markets and public finance. The role of this committee was to enhance the consultative process of monetary policy by reviewing the macroeconomic and monetary developments in the economy and advising RBI on the stance of monetary policy. With the formation of MPC, the TAC on Monetary Policy ceased to exist.

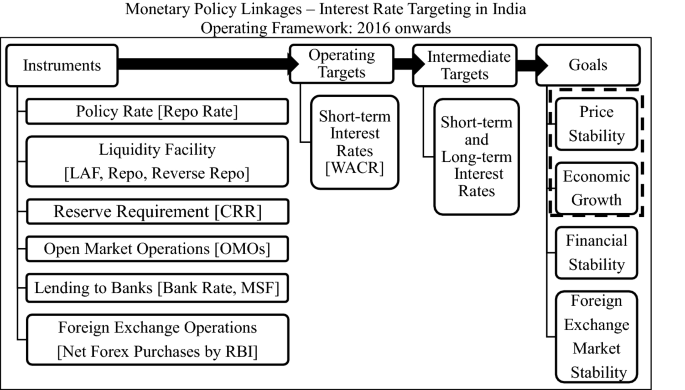

The MPC is entrusted with the task of fixing the benchmark policy rate (repo rate) required to contain inflation within the specified tolerance band. The framework entails setting the policy rate on the basis of current and evolving macroeconomic conditions. Once the repo rate is announced, the operating framework looks at liquidity management on a day-to-day basis with the aim to anchor the operating target—the weighted average call rate (WACR)—around the repo rate. This is illustrated in Fig. 5 , where the intermediate targets are the short-term and long-term interest rates and the goals of price stability and economic growth are aligned with the primary objective of monetary policy to maintain price stability, keeping in mind the objective of growth. In addition to the repo rate, the instruments include liquidity facility, CRR, OMOs, lending to banks and foreign exchange operations (RBI 2018 ).

It is imperative here to note some of the key elements of the revised framework for liquidity management (RBI 2019 ) that are particularly relevant for the operating framework shown in Fig. 5 . As noted in the RBI Monetary Policy Report, 2020.

Liquidity management remains the operating procedure of monetary policy; the weighted average call rate (WACR) continues to be its operating target.

The liquidity management corridor is retained, with the marginal standing facility (MSF) rate as its upper bound (ceiling) and the fixed reverse repo rate as the lower bound (floor), with the policy repo rate in the middle of the corridor.

The width of the corridor is retained at 50 basis points—the reverse repo rate being 25 basis points below the repo rate and the MSF rate 25 basis points above the repo rate. (The corridor width was asymmetrically widened on March 27 and April 17, 2020.)

Instruments of liquidity management continue to include fixed and variable rate repo/reverse repo auctions, outright open market operations, forex swaps and other instruments as may be deployed from time to time to ensure that the system has adequate liquidity at all times.

The current requirement of maintaining a minimum of 90% of the prescribed CRR on a daily basis will continue. (This was reduced to 80% on March 27, 2020.)

The first meeting of the MPC was held in October 2016. Between October 2016 and March 2020, the MPC has met 22 times. Table 1 shows the voting patterns for each meeting with respect to the direction of change in the policy rate, magnitude of change and the stance of monetary policy. Table 2 , on the other hand, provides an overall summary of the voting of all the meetings. It is interesting to note in Table 2 , that with respect to direction of change/status quo of the policy rate, consensus was achieved in 12 meetings out of 22. Of these 12 meetings, there were three meetings where there were differences in the magnitude of the change voted for although there was consensus regarding the direction of change. The diversity in voting of the MPC members reflects the differences in the assessment and expectations of individual members as well as their policy preferences.

To examine if this diversity exists in MPCs of other countries as well, we analyse the voting patterns of 18 countries across the globe during October 2018 to March 2020 in Table 3 . For many countries, we find dissents in some of the meetings, similar to the lack of consensus in some of the meetings of the Indian MPC.

It merits mention that the committee approach towards the conduct of monetary policy has gained prominence across globe. The advantages of this approach include confluence of specialized knowledge and expertise on the subject domain, bringing together different stakeholders and diverse opinions, improving representativeness and collective wisdom, thus making the whole greater than the sum of parts (Blinder and Morgan 2005 ; Maier 2010 ). Further, Rajan ( 2017 ) notes that MPC would bring more minds to bear on policy setting, preserve continuity in case a member has to quit or retire, and be less subject to political pressures.

4 Monetary policy transmission framework

This section presents a stylized representation of a framework for monetary policy transmission and also applies this framework to India.

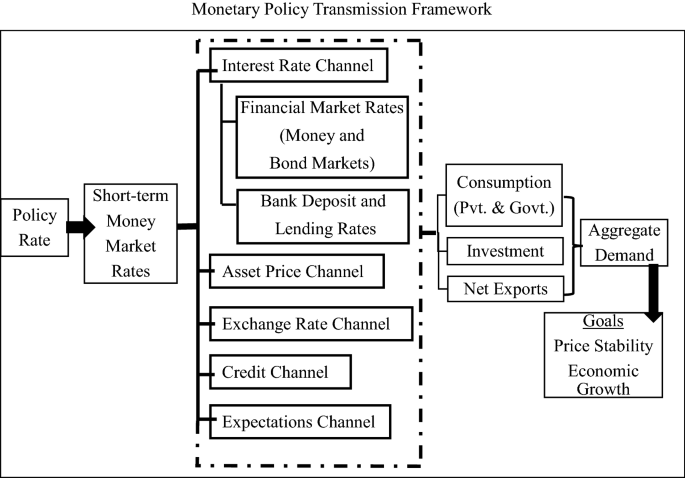

Monetary policy transmission is the process through which changes in monetary policy affect economic activity in general as well as the price level. With developments in financial systems, the world over, and growing sophistication of financial markets, most central banks use the short-term interest rate as the policy instrument for the conduct of monetary policy. Monetary policy transmission is thus the process through which a change in the policy rate is transmitted first to the short-term money market rate and then to the entire maturity spectrum of interest rates covering the money and bond markets as well as banks’ deposit and lending rates. These impulses, in turn, impact consumption (private and government), investment and net exports, which affect aggregate demand and hence output and inflation.

There are five channels of monetary transmission—interest rate channel; exchange rate channel; asset price channel; credit channel and expectations channel. The interest rate channel is described above. Monetary transmission takes place through the exchange rate channel when changes in monetary policy impact the interest rate differential between domestic and foreign rates leading to capital flows (inflow or outflow) which in turn affects the exchange rate and hence the relative demand for exports and imports. Transmission through the asset price channel occurs when changes in monetary policy influence the price of assets such as equity and real estate that lead to changes in consumption and investment. A change in prices of assets can lead to a change in consumption spending due to the associated wealth effect. For example, if interest rates fall, people may consider purchasing assets that are non-interest bearing such as real estate and equity. A rise in demand for these assets may result in higher prices, a positive wealth effect and thus higher consumption. Further if equity prices rise, firms may increase investment spending. Transmission through the credit channel happens if monetary policy influences the quantity of available credit. This may happen if the willingness of financial institutions to lend changes due to a change in monetary policy. Further, debt obligations of businesses may also change due to a change in the interest rate. For instance, if the policy rate falls, debt obligations of firms may decrease, strengthening their balance sheets. As a result, financial institutions may be more willing to lend to businesses, thus increasing investment spending. Monetary policy changes can impact public’s expectations of output and inflation and accordingly, aggregate demand can be impacted via the expectations channel . For instance, expected future changes in the policy rate can impact medium-term and long-term expected interest rates through market expectations and thus affect aggregate demand. Further, if inflation expectations are firmly anchored by the central bank, this would imply price stability.

A stylized representation of the monetary policy transmission framework of a change in the policy rate is shown in Fig. 6 . Figure 7 depicts the monetary transmission through the interest rate channel with specific reference to India. (Definitions of all variables shown in Fig. 6 are given in Appendix 2 .) This shows that a change in the policy rate (repo rate) first impacts the call money rate (weighted average call money rate—WACR) and in turn all other money market rates as well as bond market rates including the repo market, certificates of deposit (CD) and commercial paper (CP) markets, Treasury Bill (T-Bill) market, Government Securities (G-Sec) market and the Bond Market. The lending rate of banks also changes as depicted by the marginal cost of funds based lending rate (MCLR). This further impacts consumption and investment decisions as well as net exports and through these, aggregate demand and ultimately the goals of monetary policy. Details of the monetary transmission process are given in RBI ( 2020c ).

(1) Definitions of variables are given in Appendix 2

The transmission mechanism is beset with lags. As explained in simple terms in Rangarajan ( 2020 ), there are two components of the transmission mechanism. The first is how far the signals sent out by the central bank are picked by the banks and the second is how far the signals sent out by the banking system impact the real economy. Rangarajan ( 2020 ) labels the first component as “inner leg” and the second as “outer leg”.

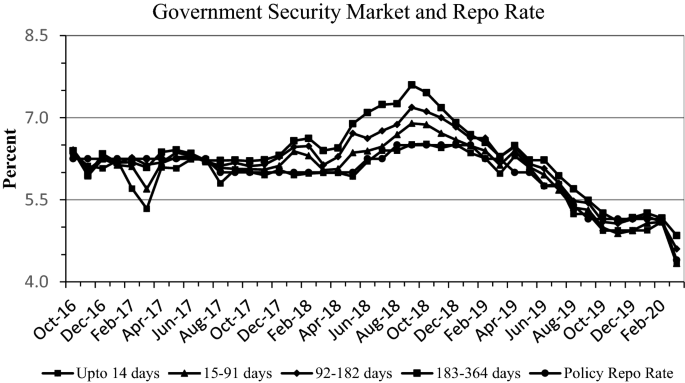

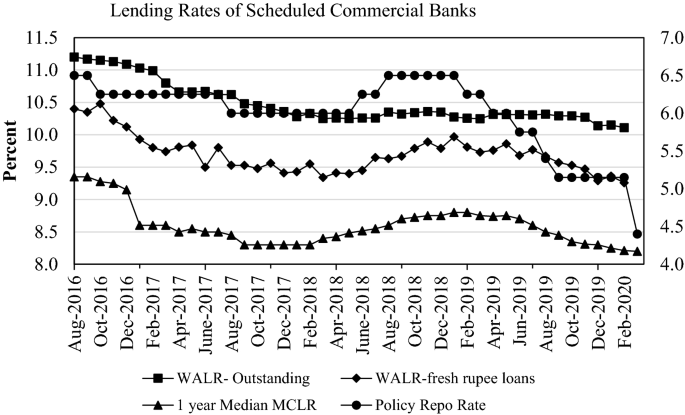

To illustrate monetary transmission of the first kind, we examine the impact of a cumulative reduction in the policy repo rate by 135 basis points between February 2019 and January 2020. During this period, transmission to various money and bond markets ranged from 146 basis points in the overnight call money market to 73 basis points in the market for 5-year government securities to 76 basis points in the market for 10-year government securities. Transmission to the credit market was also modest with the 1-year median marginal cost of funds-based lending rate (MCLR) declining by 55 basis points during February 2019 and January 2020. The weighted average lending rate (WALR) on fresh rupee loans sanctioned by banks fell by 69 basis points while the WALR on outstanding rupee loans declined by 13 basis points during February to December 2019.

Monetary transmission increased somewhat after the introduction of the external benchmark system in October 2019 whereby most banks have linked their lending rates to the policy repo rate of the Reserve Bank. During October to December 2019, the WALRs of domestic banks on fresh rupee loans fell by 18 basis points for housing loans, 87 basis points for vehicle loans and 23 basis points for loans to micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs).

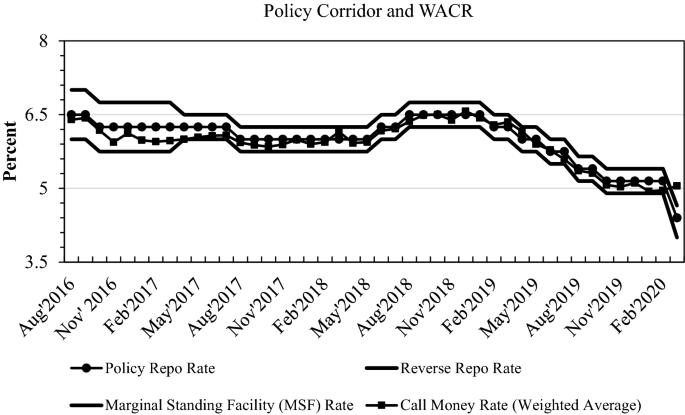

Monetary transmission in various markets is depicted in Figs. 8 , 9 and 10 . Figure 8 shows the policy corridor with the MSF rate as the ceiling and the reverse repo rate as the floor for the daily movement in the weighted average call money rate. The figure shows that the WACR moved closely in tandem with the policy rate (repo rate). Figure 9 shows that the G-Sec market rates followed the movements in the policy rate. Figure 10 shows that the direction of change of MCLR was more or less in synchronization with that of the repo rate. The WALR for fresh rupee loans tracked the repo rate much more than the WALR on outstanding loans.

Source: RBI Database on Indian Economy, RBI Weekly Statistical Supplement

Source: RBI Database on Indian Economy

Source: RBI Website

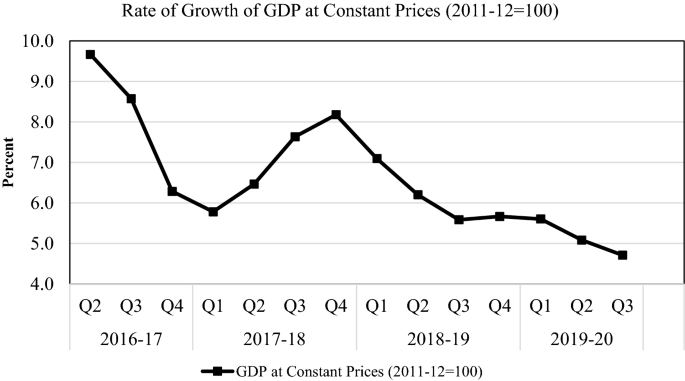

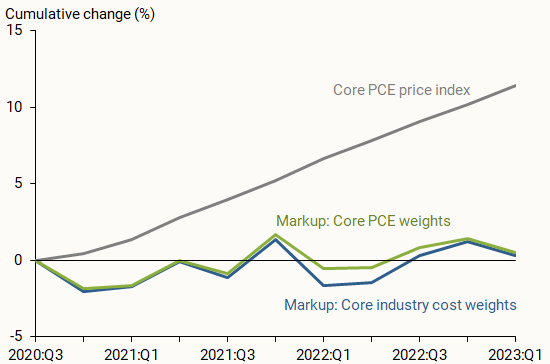

Figure 11 shows the 4% target inflation rate with the ± 2% tolerance band along with the headline inflation rate. This shows that the headline inflation generally stayed within the band. The average inflation rate from August 2016 to March 2020 was 3.93% and up to December 2019, it was 3.72%, i.e. close to 4%. The average GDP growth between Q2: 2016–2017 and Q3: 2019–2020 was 6.6% (Fig. 12 ).

Source: Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, GOI

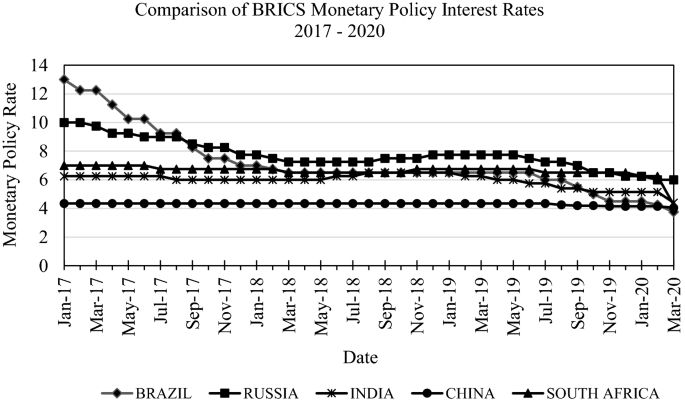

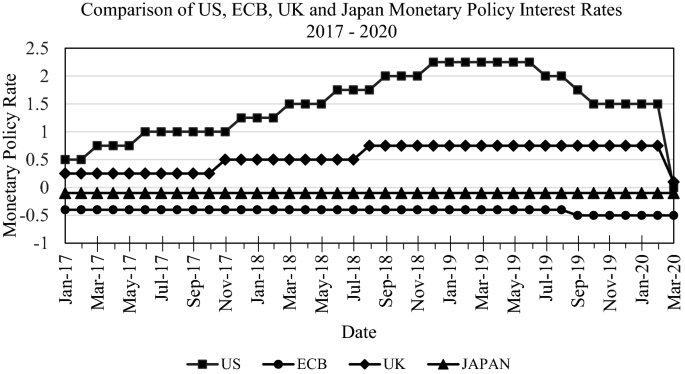

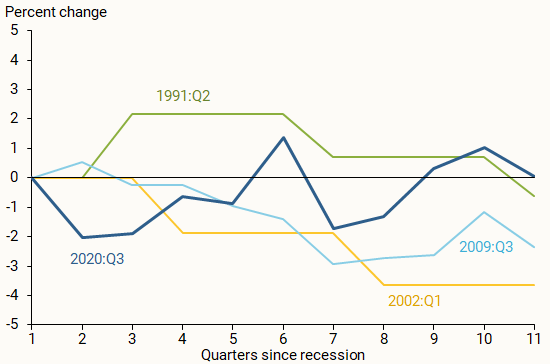

An interesting phenomena, world-wide is the synchronization in the movements in interest rates across the globe. Table 4 shows that MPCs in various countries have voted for a cut in their policy rate in 2019 at a time when many countries were simultaneously experiencing a slowdown. Due to COVID-19 pandemic, in early 2020, some countries have cut the policy rate sharply. This pattern of rate cuts in 2019 up to March 2020 is almost perfectly aligned with the movements in the repo rate (policy rate) in India. These global patterns are illustrated in Figs. 13 and 14 . Figure 13 shows that the policy rates for the BRICS nations moved in tandem from 2017 to 2020. Figure 14 indicates a similar pattern amongst policy rates of US, ECB, UK and Japan.

Source: Central Bank Websites. Brazil: Selic Rate; Russia: Key Rate; India: Repo Rate; China: Interest Rate; South Africa: Repo Rate

Source: Central Bank Websites. US: Fed Funds Rate; ECB: Interest Rate on the Deposit Facility; UK: Bank Rate; Japan: Policy Interest Rate

5 Unconventional monetary policy measures

We have so far discussed conventional monetary policy. As already described, monetary transmission of conventional monetary policy entails a change in the policy rate impacting financial markets from short-term interest rates to longer-term bonds and bank funding and lending rates. A change in the policy rate is thus expected to permeate through the entire spectrum of rates that further translates into affecting interest sensitive spending and thus economic activity. However, if there are problems in the monetary policy transmission mechanism or if additional monetary stimulus is required in the circumstances that the policy rate cannot be reduced further (or in addition to a change in the policy rate), then the central banks may employ unconventional monetary policy tools. Unconventional monetary measures target financial variables other than the short-term interest rate such as term spreads (e.g., interest rates on risk free bonds), liquidity, credit spreads (e.g. interest rates on risky assets) and asset prices. The objective of unconventional tools is to supplement the conventional monetary policy tools especially in the easing cycle to boost economic growth.

In the recent past, RBI has utilized various unconventional tools in addition to conventional monetary policy measures. To better understand the use of unconventional tools in the Indian economy, examples of unconventional monetary policy tools are first analysed and their applications to the Indian scenario are described. Broadly, unconventional measures can be classified into four categories—large scale asset purchases, lending operations, forward guidance and negative interest rates (BIS 2019 ). The key features of the measures and their applications in India are described in Table 5 .

Large scale asset purchases (also referred to as quantitative easing) by a central bank involve purchase of long-term government securities financed by crediting reserve accounts that commercial banks hold at the central bank. This purchase would lower government bond yields and serve as a signal that the policy rate will stay at a lower level for a longer period. Sellers of government bonds may, in turn, change their investment portfolios and invest in more risky assets (e.g., corporate bonds) leading to a decrease in the relevant interest rate and higher asset price and thus boost economic growth. Central banks can also purchase assets from the private sector.

Lending operations entail provision of liquidity to financial institutions by the central bank through the creation of new or extension of existing lending facilities. This mechanism is different from conventional lending since this is undertaken at looser or specific conditions, e.g., expanding the set of eligible collateral, extending maturity of the loan, providing funding at lower cost and channel/target lending to desired areas or activities with explicit conditions on loans. This lending increases the credit flows to the private sector and helps to restart flow of credit to credit-starved sectors. It can also lead to lower borrowing costs for the financial and real economy sectors.

Forward guidance involves central banks communicating future policy intentions and commitments regarding the policy rate to influence policy expectations. Forward guidance is given routinely by most central banks. Its use as an unconventional tool implies that a central bank uses this to signal that it is open to undertaking extraordinary policy actions for a longer duration. Forward guidance can be ‘time specific’ or ‘state specific’. Under the former, the central bank makes a commitment to keep interest rates low for a specified period. Under the latter, the central bank maintains low rates until specific economic conditions are met.

The rationale of a negative interest rate is that if an interest rate is charged on the reserves that commercial banks hold at the central bank, the banks may be induced to reduce their excess reserves by increasing lending.

The first three of these have been applied to India and are reported in Table 4 . These include Operations Twist in December 2019 and January as well as April 2020, long-term repo operation (LTRO) in February 2020, targeted long-term repo operations (TLTRO) in March and April 2020, and special refinance facilities to National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD), Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI) and National Housing Bank (NHB) in April 2020.

The application of these unconventional monetary tools was necessitated, first by the slowdown in the Indian economy in 2019, and second, by the impact of COVID-19 pandemic due to which economic activity and financial markets, the world over, came under severe stress. It was thus necessary for the Reserve Bank to employ measures to mitigate the impact of COVID-19, revive growth and preserve financial stability. Thus the unconventional monetary policy tools supplemented the conventional monetary policy measures to stimulate growth in the economy.

6 Conclusions

This paper reviews the evolution of monetary policy frameworks in India since the mid-1980s. It also describes the monetary policy transmission process and its limitations in terms of lags in transmission as well as the rigidities in the process. It also highlights the importance of unconventional monetary policy measures in supplementing conventional tools especially during the easing cycle.

At the time of writing (April 2020), three and a half years have passed since the implementation of the Flexible Inflation Targeting Framework and the constitution of the Monetary Policy Committee. With the implementation of FIT, India joined the group of various developed, emerging and developing countries that have implemented inflation targeting since 1990.

The inflation target specified by the Central Government was 4% for the Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation for the period from August 5, 2016 to March 31, 2021 with the upper tolerance limit of 6% and the lower tolerance bound of 2%. As shown in Fig. 11 , from August 2016 through March 2020, the headline inflation generally stayed within the tolerance band with the average inflation rate slightly less than 4% during this period. There were episodes of high/unusual inflation due to supply shocks (food inflation, oil prices) but these were suitably integrated in the policy decisions.

The Monetary Policy Committee has also been in existence since October 2016. The mandate of the MPC is to set the policy repo rate while taking cognizance of the primary objective of monetary policy—to maintain price stability while keeping in mind the objective of growth—as well as the target inflation rate within the tolerance band. Once the policy repo rate is set, the monetary transmission process facilitates the percolation of the change in the policy rate to all financial markets (money and bond markets) as well as the banking sector which further impacts interest sensitive spending in the economy and eventually increases aggregate demand and output growth.

In practice, however, there are rigidities as well as lags in the transmission process that impede the speed and magnitude of the transmission and thus question the efficacy of monetary policy with respect to the policy repo rate. Nevertheless, the external benchmarking system introduced by RBI from October 1, 2019 whereby all new floating rate personal or retail loans (housing, auto etc.) and floating rate loans to micro and small enterprises extended by banks were benchmarked to an external rate, strengthened the monetary transmission process with several banks benchmarking their lending rate to the policy repo rate. This requirement of an external benchmark system was further expanded to cover new floating loans to Medium Enterprises extended by banks with effect from April 1, 2020. This is expected to further improve the transmission process.

Of course, the policy repo rate is not a panacea for all ills but serves well as a signaling rate. The RBI routinely brings out the Statement on Developmental and Regulatory Policies Footnote 1 that is released simultaneously with the resolution of the MPC. RBI has also taken recourse to unconventional measures to supplement the conventional tools to boost economic growth. More recently, with the slowdown in 2019 followed by the extraordinary slump in economic activity due to COVID-19 pandemic, RBI has been compelled to use rather innovative and unconventional tools starting in December 2019 as discussed in Table 5 .

Needless to say, in the unprecedented times of the global pandemic (and, in general, in periods of severe crises), a multi-pronged approach comprising monetary, fiscal and other policy measures is required to protect economic activity and minimize the negative impact of the pandemic (crisis) on economic growth. The importance of monetary-fiscal coordination is highlighted in the resolution of the Monetary Policy Committee dated March 27, 2020 (available on the RBI website) that states the following: “Strong fiscal measures are critical to deal with the situation.” Thus, in addition to monetary policy, fiscal policy has a major role in combating the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. In response to the need of the hour, the Government of India has implemented various fiscal measures to provide a boost to the economy. While central banks across the globe have responded to the global pandemic with monetary and regulatory measures, various governments have reinforced the monetary measures by deploying massive fiscal measures to shield economic activity from the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic.

A few words about the workings of the MPC are also warranted. As discussed in the paper, the voting pattern of the Indian MPC is comparable to international standards, reflecting the healthy diversity in the assessment of the members. The workings of the MPC are transparent with the resolution being made available soon after the end of the meetings. Furthermore, each member of the Committee has to submit a statement that is made available in the public domain on the 14th day after the meeting. Thus, each member is individually accountable, making the process perhaps more stringent than that of MPCs in other countries.

Statement on Developmental and Regulatory Policies sets out various developmental and regulatory policy measures and macroprudential policies for strengthening financial markets and systems, regulation and supervision, banking sector etc. from time to time.

Interest rates on fixed rate loans of tenor below 3 years shall not be less than the benchmark rate for similar tenor.

In case of newly set up banks (either domestic or foreign banks operating as branches in India) where lending operations are mainly financed by capital, the weightage for this component may be higher in proportion to the extent of capital deployed for lending. This dispensation will be available for a period of three years from the date of commencing operations.

Bank for International Settlements. (2019). Unconventional monetary policy tools: a cross-country analysis. Report by a Working Group (Chaired by: Simon M. Potter, Federal Reserve Bank of New York and Frank Smets, European Central Bank). Committee on the Global Financial System. BIS.

Blinder, A., & Morgan, J. (2005). Are two heads better than one? An experimental analysis of group versus individual decision-making. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 35 (5), 789–811.

Google Scholar

Government of India. (2009). A hundred small steps: Report of the committee on financial sector reforms (Chairman: Raghuram Rajan) . New Delhi: Planning Commission.

Hammond, G. (2012). State of the art of inflation targeting. Handbooks, Centre for Central Banking Studies, Bank of England, 4th edn, number 29

Hattori, M., Yetman, J. (2017). The evolution of inflation expectations in Japan. Bank of International Settlements Working Papers, No. 647. Bank of International Settlements, pp 1–3

Korhonen, L., & Nuutilainen, R. (2017). Breaking monetary policy rules in Russia. Russian Journal of Economics, 3 (4), 366–378.

Article Google Scholar

Laurens, B.J., Eckhold, K., King, D., Maehle, N., Naseer, A., Durré, A. (2015). The journey of inflation targeting: Easier said than done the case for transitional arrangements along the road. International Monetary Fund, WP/15/136.

Maier, P. (2010). How central banks take decisions: an analysis of monetary policy meetings. In P. L. Siklos, M. T. Bohl, & M. E. Woher (Eds.), Challenges in central banking: the current institutional environment and forces affecting monetary policy . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mishkin, F. S. (2016). The economics of money, banking, and financial markets . Pearson: Columbia University.

Mohanty, D. (2010). Monetary policy framework in India: Experience with multiple-indicators approach. In: Speech delivered at the Conference of the Orissa Economic Association in Baripada, Orissa on 21st February, 2010. Orissa

Mohanty, D. (2011). Changing contours of monetary policy in India . Mumbai: Reserve Bank of India Bulletin. (Dec 2011)

Rajan, R. G. (2017). I do what I do . New Delhi: Harper Collins.

Rangarajan, C. (2020). The new monetary policy framework—What it means. In: Prof. Sukhamoy Chakravarty Memorial Lecture, delivered at Annual Conference of the Indian Econometric Society at Madurai Kamaraj University in January 2020 . https://www.nipfp.org.in/media/medialibrary/2020/02/WP_297_2020.pdf

Reddy, Y.V. (1999) Monetary policy operating procedures in India. In: Bank of International Settlements. (Ed.) Monetary policy operating procedures in emerging market economies. BIS Policy Papers No. 5 , pp 99–109

Reserve Bank of India. (1985). Report of the committee to review the working of the monetary system (Chairman: Dr. Sukhamoy Chakravarty). Mumbai

Reserve Bank of India. (1998). Report of the working group on money supply: analytics and methodology of compilation (Chairman: Dr. Y. V. Reddy). Mumbai.

Reserve Bank of India. (2013). Report on currency and finance 2009–2012: fiscal-monetary co-ordination. Mumbai.

Reserve Bank of India. (2014). Report of the expert committee to revise and strengthen the monetary policy framework (Chairman: Dr. Urjit Patel). Mumbai.

Reserve Bank of India. (2017). Report of the internal study group to review the working of the marginal cost of funds based lending rate system (Chairman: Dr. Janak Raj). Mumbai.

Reserve Bank of India. (2018). Forex market operations and liquidity management (by—Janak Raj, Sitikantha Pattanaik, Indranil Bhattacharya and Abhilasha) . Mumbai: Reserve Bank of India Bulletin.

Reserve Bank of India. (2019). Report of the internal working group to review the liquidity management framework. Mumbai.

Reserve Bank of India. (2020a). Governor’s statement, sixth bi-monthly monetary policy statement, February 6, 2020. Mumbai.

Reserve Bank of India. (2020b). Governor’s statement, seventh bi-monthly monetary policy statement, March 27, 2020. Mumbai.

Reserve Bank of India. (2020c). Monetary policy transmission in India—Recent trends and impediments (by—Arghya Kusum Mitra and Sadhan Kumar Chattopadhyay). Reserve Bank of India Bulletin, March. Mumbai.

Reserve Bank of India. (2020d). Monetary Policy Report, April. Mumbai.

Reserve Bank of India. (2020e). Governor’s Statement, April 17, 2020. Mumbai.

The Economist Intelligence Unit. (2016). Argentine Central Bank adopts inflation-targeting regime. Financial Services, The Economist Group, September.

Vasudevan, A. (2017). Reflections on analytical issues in monetary policy: The Indian Economic Realities. Economic and Political Weekly, 52 (12), 45–52.

Download references

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Michael Patra and Janak Raj, Deputy Governor and Executive Director respectively, Reserve Bank of India for useful and constructive suggestions. I also gratefully acknowledge help and support from Hema Kapur, Deepika Goel and Neha Verma, teachers in colleges of the University of Delhi, who also motivated me to write in a student-friendly manner. Special thanks are due to Naina Prasad for competent and diligent research assistance. I am grateful to the Editors of the Indian Economic Review for inviting me to contribute to the newly instituted section on Policy Review. Earlier versions of this paper were presented as a Public Lecture at the Delhi School of Economics in March 2020 and as a Keynote Address at the Annual Conference of the Indian Econometric Society at Madurai Kamaraj University in January 2020. I am grateful to the participants of these events for their feedback.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Economics, Delhi School of Economics, University of Delhi, Delhi, India

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Pami Dua .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The views expressed in this paper are of the author and not of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), of which she is a member.

Appendix 1: Glossary (Figs. 2 and 5 )

Source: Handbook on RBI’s Weekly Statistical Supplement; Reserve Bank of India Website

Appendix 2: Glossary (Fig. 8 )

Appendix 3: constitution of the monetary policy committee.

The Gazette Notification of the Ministry of Finance dated September 29, 2016 notes the following.

“In exercise of the powers conferred by Section 45ZB of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934 (2 of 1934), the Central Government hereby constitutes the Monetary Policy Committee of the Reserve Bank of India, consisting of the following, namely:

The Governor of the Bank—Chairperson, ex officio;

Deputy Governor of the Bank, in charge of Monetary Policy—Member, ex officio;

One officer of the Bank to be nominated by the Central Board—Member, ex officio;

Shri Chetan Ghate, Professor, Indian Statistical Institute (ISI)—Member;

Professor Pami Dua, Director, Delhi School of Economics (DSE)—Member; and

Dr. Ravindra H. Dholakia, Professor, Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, Member.”

The three external members have served on the Committee since its inception and continue to serve. There have been some changes in the RBI members as follows.

Former Governor, Dr. Urjit Patel chaired the Committee from October 2016 to December 2018. Governor, Shri Shaktikanta Das presided from the February 2019 meeting onwards.

Shri R. Gandhi, Former Deputy Governor attended the October and December meetings in 2016.

Dr. Viral Acharya, Former Deputy Governor in charge of Monetary Policy attended the meetings from February 2017 to June 2019.

Shri Bibhu Prasad Kanungo, Deputy Governor attended the meetings from August to December 2019.

Dr, Michael Patra attended all the meetings, first as Executive Director till December 2019 and continues to attend meetings as Deputy Governor in charge of Monetary Policy.

Dr. Janak Raj has attended meetings since February 2020 as Executive Director.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Dua, P. Monetary policy framework in India. Ind. Econ. Rev. 55 , 117–154 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41775-020-00085-3

Download citation

Published : 23 June 2020

Issue Date : June 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s41775-020-00085-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Inflation targeting

- Monetary Policy Committee

- Monetary transmission process

- Unconventional monetary policy measures

JEL Classification

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

The Official Journal of the Pan-Pacific Association of Input-Output Studies (PAPAIOS)

- Open access

- Published: 09 May 2020

Tax structure and economic growth: a study of selected Indian states

- Yadawananda Neog ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3578-0460 1 &

- Achal Kumar Gaur 1

Journal of Economic Structures volume 9 , Article number: 38 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

49k Accesses

27 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

The present study examines the long-run and short-run relationship between tax structure and state-level growth performance in India for the period 1991–2016. The analysis in this paper is based on the model of Acosta-Ormaechea and Yoo ( 2012 ), and for the verification of the relationship between taxation and economic growth the panel regression method is used. With the use of 14 Indian states data, Panel Pool mean group estimation indicates that income tax and commodity–service tax have negative effects whilst property and capital transaction tax have a significant positive effect on state economic growth. This study finds ‘U’ shape relationship between tax structure and growth performance. Based on the analysis, we conclude that for faster growth of Indian states, policymakers should give more focus on property taxes along with the reduction in income taxes.

1 Introduction

The study on the potential association between tax structure and growth performance has gathered a great deal of attention from policymakers, academicians and regulatory circles for several reasons. First, the developing and emerging economies require a large volume of tax revenues for the smooth and efficient functioning of the state at both the national and sub-national levels. Globalization has laid down the foundation for Goods and Service Tax (GST) in many developing countries (Mcnabb 2018 ). Due to competition, developing countries are also facing the difficulties to maintain existing tax revenues (Bird and Zolt 2011 ). Second, tax collection and structure of it create distortionary impacts in the economy through tax burden. Thus, the positive and negative impact of tax made the ‘tax–growth’ relationship more complex and the structure of taxation has a definite role in the development process of an economy.

In a budget constraint economy like India, investigation of tax–growth relationship enables us to formulate the suitable policy measure for the more inclusive and equitable growth process. The budget crisis is usually resolved through the cut-down of public spending or/and an increase in tax revenues (Macek 2014 ). Rapid reduction in spending or increase in taxes is harmful to long-run growth performance. Thus, the concern of the government lies with the problem of fiscal consolidation with sustainable growth performance where tax policies are vital.

Empirical evidence on the impact of tax structure on growth performance is not conclusive. India has adopted the Goods and Service Tax (GST) policy in 2017 intending to raise indirect tax collections and transform the indirect tax structure into a single market to avoid tax evasions and double taxation. GST is regarded as one of the major tax policy changes in independent India and economists are an optimist about its impact on revenue generations and growth performance. But this policy is not the only policy that shaped in independent India; other major policy changes also take place after independence. Footnote 1 Tax Reform Committee (TRC) report of 1991 regarded one of the productive and structured policy recommendations in the recent decade. At the state level, sales tax reform in the form of Value Added Tax (VAT) in 2005 becomes a fruitful policy initiative. However, the tax collections in both national and sub-national level are still low as compared to the international standards. Changes in tax policy also change in the tax structure in the economy and India witnessed these changes at both levels of governments. Recent studies proved that the changes in tax structure have decisive implication in the growth performance through work–leisure behaviour, investment decisions and overall productivity (Arnold et al. 2011 ; Gemmell et al. 2011 ; Macek 2014 ; Mdanat et al. 2018 ; Durusu-Ciftci 2018 ). In India, very few empirical studies are available which analyse the impact of these changes in tax structure on growth performance and this study will be first to investigate tax–growth nexus in India with the use of state-level data.

This analysis primarily concerned with tax structure rather than to tax levels (usually measured as a tax–GDP ratio). The main advantage of tax structure analysis is that it provides revenue-neutral tax policy changes which remove the difficulties related with the question of how aggregate tax revenue changes relates with expenditure changes (Arnold et al. 2011 ). The empirical results from linear panel regression suggest us that property and capital transection tax are positively affecting the state’s growth performance, where commodity and service tax effect negatively. However, the non-linear panel regression indicates that the positive effect is only visible for property taxes at a higher level where the negative effect of commodity and service taxes becomes positive after a threshold point. The effect of income tax is not significant in long run irrespective of panel regression models.

The structure of the paper is as follows: Sect. 2 deals with the theoretical framework and empirical literature, followed by a brief description of data and methodology in Sect. 3 . Empirical results and discussion are presented in Sect. 4 and our last Sect. 5 is for conclusions and recommendations.

2 Theoretical framework and empirical literature

Growth literature very recently acknowledges the role of taxation in the growth process of an economy. Until recently, growth models are more concerned with the steady-state process and exogenous changes. On the theoretical ground, taxation does not have any impact on growth (Myles 2000 ). Development of endogenous growth models creates the space for fiscal policy especially tax policy in determining the growth performance. Barro ( 1990 ), King and Rebello ( 1990 ) and Jones et al. ( 1993 ) were the pioneer in this regard. Tax level and tax structure have an impact on the saving behaviour of the household and investment in human capital. On the other hand, the firm also changes its investment decisions and innovations following tax policies (Johansson et al. 2008 ). These decisions and incentives in the accumulation of physical and human capital create the ‘Growth’ disparities amongst the countries and state economies.

A large body of literature available on “Tax-Growth” relationship is mostly dedicated to cross-country settings (Martin and Fardmanesh 1990 ; Karras 1999 ; Myles 2000 ; Tosun and Abizadeh 2005 ; Johansson et al. 2008 ; Vartia et al. 2008 ; Arnold 2011 ; Szarowska 2013; Macek 2014 ; Stoilova 2017 ; Safi et al. 2017 ; Durusu-Ciftci 2018 ) that investigates the effect of tax policy on economic performance. Income and corporation taxes are the major tax instruments for the governments irrespective of the level of developments of a country. The formation of tax structure with these two taxes has many implications in the growth performance. The study made by Arnold et al. ( 2011 ), Macek ( 2014 ) and Dackehag and Hansson ( 2012 ) has explored the negative relation of income and corporation tax with growth performance. Vartia et al. ( 2008 ) find the negative impact of corporation tax for OECD countries. If we consider the average and marginal tax rate, marginal tax is very influential than to average tax rate in investment decisions and labour supply. Empirical studies prove that marginal tax has a negative relation with growth, which indicate raising of marginal tax rate is associated with compromises with growth performance (Padovano and Galli 2001 ; Lee and Gordon 2005 ; Poulson and Kaplani 2008 ). Studies also established that other type of taxes also has a significant impact on growth performance, like consumption tax (Johansson et al. 2008 ; Durusu-Ciftci 2018 ), GST and Payroll (Tosun and Abizadeh 2005 ), property tax (Xing 2011 ), labour tax (Szarowska 2014 ), sales tax (Ojede and Yamarik 2012 ), excise (Reynolds 2006 ), etc.

However, looking at the single country’s perspective, we find very little evidence on the same. Stockey and Rebelo ( 1995 ) with the use of the endogenous growth model study the role of tax reforms on U.S. growth performance. They have found that tax reforms have very minor implication with economic outcomes. There are several studies exist for US economy where they empirically try to establish the link between tax and growth. Atems ( 2015 ) finds the spatial spillover effect of income taxes on the growth of 48 contiguous states. On the other hand, Ojede and Yamarik ( 2012 ) have not found any kind of impact of income taxes on growth in these states. Their panel pool mean group estimation indicates that property and sales tax has detrimental consequences in development. With the use of data for the U.S. covering the period of 1912–2006, Barro and Redlick ( 2009 ) find that average marginal income taxes were halting the economic growth. However, they have provided an interesting argument that in wartime, the tax does not have any kind of relation with growth. In search of an answer to the question that whether corporate tax rise destroys jobs in the U.S., Ljungqvist and Smolyansky ( 2016 ) use firm-level data for the period 1970–2010. The main conclusion of the paper is that a rise in corporate tax is not good for employment and income and has very little impact on economic activity. Using the error correction model, Mdanat et al. ( 2018 ) find for Jordan that income tax, corporation tax and personal tax negatively impact the growth. They suggest that irrespective of tax collection, the prime focus of the government should be social justice of the people. Dladla and Khobai ( 2018 ) also find similar results for South Africa where income taxes are coming out to be negative. For the case of Italy, Federici and Parisi ( 2015 ) used the 880 firms’ data and results show that corporation tax is bad for investments with the consideration of both effective average and marginal taxes rates.

Looking at the literature, the empirical relationship of tax structure with growth performance is still unclear for India. This study attempts to fill the gap by examining the effect of tax policy on economic performance in an emerging economy such as India at the state level. Second, with the use of panel Pool Mean Group (PMG) estimator which assumes slope homogeneity in the long run and heterogeneity in the short run, we can incorporate the dynamic behaviour of the variables which will be new to tax structure–growth study in India. Third, the tax–growth nexus may show a non-linear relationship due to the threshold effect. We consider this non-linearity in our panel regression model which will be a contribution to the existing literature.

3 Data and methodology

To study the effect of tax policy on economic performance in India, we employed three models and included each tax instruments in the models separately to avoid the problem of Multicollinearity. Following the works of Arnold et al. ( 2011 ) and Acosta-Ormaechea and Yoo ( 2012 ), the tax structure is measured by the share of individual tax to the total state tax revenues. We investigate the tax–growth relationship with the following equation.

Here, Y it is the growth rate of Per capita net state domestic product (NSDP), SGI is the state gross investment as a percentage of state domestic product, TAX is one of the tax shares (Property, Commodity & Services and Income), Tax Burden Footnote 2 is the ratio of total tax revenues to state domestic product and ϵ is the error term. Per the work of Acosta-Ormaechea and Yoo ( 2012 ), this study is more concerned with the impact of tax structure on growth rate rather than level effect. In model 1, we include property tax share, and in model 2 and model 3, we incorporate commodity & service tax and income tax, respectively. By following the approach of Arnold et al. ( 2011 ), we include total tax burden as a control variable which will reduce the biases that may occur from correlation in between tax mix and tax burden. We also included Secondary Enrollment Rate as a proxy variable for human capital in our model, but the inconsistent and insignificant results make us drop the variable from the final estimation model.

In search of a possible non-linear relationship, we introduce a separate panel regression by introducing the square of each tax share into the models.

If the coefficient of α 3 significant and carries an opposite sign to α 2 , then we can conclude that there is a non-linear relationship exist.

In this study, we included 14 Indian states for the period 1991 to 2016 and excluded North-Eastern states due to their relatively small tax revenue collections. Data have been taken from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) and Handbook of Statistics on the Indian States, published by Reserve Bank of India. The states that are included in this study are Andhra Pradesh (undivided), Footnote 3 Assam, Gujarat, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu & Kashmir, Karnataka, Kerala, Maharashtra, Punjab, Tamil Nadu, Orissa, Rajasthan and West Bengal. All the states are included in model 1 and model 2. For model 3, due to the data availability, we include only seven states Footnote 4 namely Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Gujarat, Karnataka, Kerala, Maharashtra, and West Bengal.

The selection of the study period is primarily driven by the argument provided by Rao and Rao ( 2006 ) that after the market-oriented economic reform of 1991, more systematic and long-term goal-oriented tax reforms were initiated in state level for India. The economic reform also brings rapid growth in India and it becomes very interesting to look at the tax–growth nexus after the economic reform. The second restriction related to the use of long data span is the availability of data for each tax head for each of the states under this study.

3.1 Unit root

Pool Mean Group (PMG) specification is very fruitful and widely used model to capture the dynamic behaviour of policy variables. This model is very powerful as it can investigate both I (0) and I (1) variables in a single autoregressive distributive lag (ARDL) model setup. A necessary condition in the ARDL model is that the model cannot deal with the I(2) variables. Thus, the investigation of stationarity becomes a compulsion. We used popular panel unit root tests like LLC (Levin et al. 2002 ), the IPS (Im et al. 2003 ), the ADF-Fisher Chi square (Maddala and Wu 1999 ) and PP-Fisher Chi square (Choi 2001 ) in this study.

3.2 Panel PMG model

The Mean Group (MG) estimator was developed by Pesaran and Smith ( 1995 ) to solve the issue of bias related to heterogeneous slopes in dynamic panels. Traditional panel models like instrumental variables’ estimator of Anderson and Hsiao ( 1981 , 1982 ) and Arellano and Bond ( 1991 ) may produce inconsistent results in a dynamic panel framework (Pesaran et al. 1999 ). MG estimator takes the average value of every cross-section and provides the long-run estimate for ARDL or PMG. On the other hand, Pooled Mean Group (PMG) estimator developed by Pesaran et al. ( 1999 ) assumes slope homogeneity in the long run but heterogeneous slopes in the short run for cross-section units. Dynamic Fixed Effect (DFE) also works like PMG and restricts cointegrating vector to be equal across all panels and restricts the speed of adjustment to be equal.

Under these assumptions, PMG is more efficient estimator than to MG and DFE estimator. The prime requirement for PMG estimator is that T should be sufficiently large to N. Panel ARDL or PMG works through maximum likelihood. Our basic PMG begins with the following equation.

Here, x it is the vector explanatory variables and y i is the lag dependent variable. X it allows the inclusion of both I (0) and I (1) variables. State fixed effect is captured through μ i . Above equation can be re-parameterized to ARDL format.

ɸ i measures the state-specific speed of adjustment and known as Error Correction Term. Β i is the vector of long-run relationships and α ij and θ ij are the vectors of short-run dynamic relationships. Pesaran et al. ( 1999 ) did not provide any statistical test for checking long-run relationship but it can be concluded form sign and magnitude of Error Correction Term (ECT). If it is negative and less than − 2, a long-run relationship can be established.

4 Results and discussion

Panel unit root test results from Table 1 suggest that in the case of Model 1 & 2, the Growth rate of Per Capita Net State Domestic Product (PC-NSDP), Property tax and commodity taxes are stationary at level. Gross investment and total tax revenue share to GDP are stationary at the 1st difference in all models and income tax share is also stationary at the same order.

5 PMG model results

We have reported MG, PMG and DFE estimation in the Tables 2 and 3 . The Hausman test indicates that the PMG model is the best model for our data than to MG model. Negative and significant error correction terms in all the models show the long-run relationship in between variable. One major issue related to the tax–growth equation is the problem of endogeneity of the variables. As growth in per capita GDP is our dependent variables, there is a possibility that tax collections behave along with business cycles. Therefore, we tested the weak/strong exogeneity of the tax variables through the correlation analysis between business cycles and tax shares. Business cycles have been calculated using the Hodrick-Prescott (HP) Filter. We have found that all the tax instruments are very weakly related to the business cycles movement and thus, we conclude that variables are not truly endogenous.

The speed of adjustment in PMG model 1, 2 and 3 are 78.9%, 78.4% and 79.6%, respectively. For the sake of completeness, we have reported MG and DFE Footnote 5 model results also. But we are more concerned with the results of PMG estimator as Hausman test suggested that PMG is a better model than to MG. The sign of the property tax is positive and significant in the long run as well as in the short run. Results are in line with the findings of Acosta-Ormaechea and Yoo ( 2012 ). Property tax generally considered a good revenue source for state and municipal governments for providing economic and social services in the city. This tax is also able to establish cost–benefit linkages and feasible decisions for the citizens. The positive impact of property taxes indicates that the revenue generation and productive utilization of these revenues exceed the distortionary effect in these states. As we expected, the tax burden is negatively associated with growth performance in both long run and short run. The relationship is showing the distortionary effect of the tax collection in the state economy. In all models, gross investment enhancing the growth in per capita SDP in the long run. Signs are readily justified as enlargement of capital formation has a positive impact on output and employment which channelized to the development outcomes (Swan 1956 , Solow 1956 ).

Commodity and service taxes are negatively related to the growth in per-capita SDP in the long run as well as in short run and findings are similar to the work of Ojede and Yamarik ( 2012 ). Footnote 6 This tax now comes under the Goods & Services taxes, but in the pre-GST period, commodity and service taxes are reducing growth in per capita NSDP. Commodity taxes are indirect taxes and state own tax revenues mostly come from indirect taxes. As indirect taxes, it has certain disadvantages like inflationary pressure in the economy and regressive to the poor section of the society. Our results also support the same hypothesis that increased commodity tax share is harmful. In India, commodity and service tax includes central sale tax, state excise duty, vehicle tax, goods & passenger tax, electricity duty and entertainment tax. Central sale tax was imposed on interstate trade of commodities which is now transformed to Inter-State GST (IGST). According to Das ( 2017 ), if the IGST rate is high to the Revenue Neutral Rate, it will harm the aggregate demand in the economy through the reduction of disposable income. Heavy vehicle and passenger tax collections are creating an abysmal environment for industrial activities. The tax burden variable is also carrying a negative sign in both long run and short run and magnitude is very similar to model 1. Income tax share has become insignificant and positive in the long run and negative insignificant in the short run.

After examining the linear relationships, we extended our analysis to the examination of a non-linear relationship with the use of PMG estimation model. The result from Tables 4 and 5 indicates the existence of a non-linear relationship between tax structure and growth performance for Indian states. The linear coefficient for property taxes has now become negative and the square of it turns out to be positive. Thus, the property taxes show a ‘U’-shaped relationship with states’ growth performance which implies that a rise in property taxes is bad for growth initially and after a threshold point, it becomes growth enhancing. The threshold point for property taxes is 1.88 which indicates that more than 80.77% observation is more than to threshold point.

In the case of commodity and service taxes, both the linear and non-linear coefficients are significant with different signs. However, the coefficient magnitudes are abnormally large and this is due to the inclusion of both linear and quadratic terms into the single equation. The small commodity and service taxes are very bad for the state economy, whereas the large amount of it shows a positive relation. The threshold point for this tax is 4.45 which implies that 79.95% observation lies above the threshold. This is a very interesting result as high commodity and service taxes could lead to high inflation in the economy and high inflation regarded as atrocious for growth. Further investigation of these findings is highly recommendable. As like linear panel regression, the income tax shows no relation in our non-linear regression model also. However, the short-run coefficient for income tax is significant and shows a negative relationship. Income tax is considered to be distortionary tax to the economy in the presence of income and substitution effect (Kotlan 2011 ). Income tax mostly impacts the savings of the households and labour supply which is regarded as an engine of growth.

6 Conclusions and recommendations

In this study, we try to find out the long-run and short-run relationship between different tax structure and economic growth in states of India. Empirical evidence from linear regression suggests that the property tax enhancing growth and commodity & service taxes reduce it. The non-linear regression validates these findings for property taxes where high property taxes are good for growth. In the case of commodity & service taxes, the results become opposite after the threshold point and affecting the growth negatively. Interestingly, we do not find any significant impact of income taxes on growth in both linear and non-linear regressions in the long run.

As far as the total tax burden is concerned, negative relation with the growth performance is verified and results are in line with Arnold et al. ( 2011 ). The negative effect of commodity and service taxes in the short run is expected to be neutralized through the implementation of GST in India. Promotion of growth performance at the state level concerning income taxes is also very crucial. Income tax has a direct effect on individuals and their saving and investment behaviour. On the other side, tax revenues should be placed in productive investments. With the spending, the government can promote inclusive growth, equality and efficiency in the economy.

The most promising path emerged through this study for long-run growth performance in Indian states is to lower the total tax burden and shifting from income and commodity taxes to property tax for revenue generations. The conclusion may be debatable on various grounds as the studied variables do not take into account institutional quality, administrative efficiency in tax collection, fiscal balance and condition of the states and existence of informal sectors. Future research can be done to incorporate these issues.

Availability of data and materials

Dataset analysed in this study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

One can see the writings of Rao and Rao ( 2006 ) for brief discussion.

This is the proxy for total tax burden in the economy with certain limitations. It does not include informal economy and expenditure policies.

Telangana state was established in 2014. We merged the data of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana to achieve aggregate data for undivided Andhra Pradesh.

Data for Income tax are available for ten states, but inclusion of these states made the model inconsistent due to huge fluctuations in tax revenue collections.

Most of the coefficients of PMG and DFE are in similar range and smaller than to MG estimator. This is due to MG estimator only takes the information of each state time series to estimate long-run and short-run coefficients.

They use sale tax, where our study takes aggregate revenue for commodity and services. However, inference can be drawn as sale tax and is one of the dominant contributors in total commodity and service tax revenue in India.

Abbreviations

Net state domestic product

Goods and service tax

Foreign direct investments

- Pool mean group

Dynamic fixed effect

Auto-regressive distributed lag

The organization for economic co-operation and development

Anderson TW, Hsiao C (1981) Estimation of dynamic models with error components. J Am Stat Assoc 76(375):598–606

Article Google Scholar