Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 09 June 2023

Disentangling the cultural evolution of ancient China: a digital humanities perspective

- Siyu Duan 1 , 2 ,

- Jun Wang 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Hao Yang 2 , 3 &

- Qi Su 2 , 3 , 4

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 310 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

5887 Accesses

2 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Anthropology

- Cultural and media studies

- Language and linguistics

Being recognized among the cradles of human civilization, ancient China nurtured the longest continuous academic traditions and humanistic spirits, which continue to impact today’s society. With an unprecedented large-scale corpus spanning 3000 years, this paper presents a quantitative analysis of cultural evolution in ancient China. Millions of intertextual associations are identified and modelled with a hierarchical framework via deep neural network and graph computation, thus allowing us to answer three progressive questions quantitatively: (1) What is the interaction between individual scholars and philosophical schools? (2) What are the vicissitudes of schools in ancient Chinese history? (3) How did ancient China develop a cross-cultural exchange with an externally introduced religion such as Buddhism? The results suggest that the proposed hierarchical framework for intertextuality modelling can provide sound suggestions for large-scale quantitative studies of ancient literature. An online platform is developed for custom data analysis within this corpus, which encourages researchers and enthusiasts to gain insight into this work. This interdisciplinary study inspires the re-understanding of ancient Chinese culture from a digital humanities perspective and prompts the collaboration between humanities and computer science.

Similar content being viewed by others

Evol project: a comprehensive online platform for quantitative analysis of ancient literature

Network analysis reveals insights about the interconnections of Judaism and Christianity in the first centuries CE

Evolution and transformation of early modern cosmological knowledge: a network study

Introduction.

Although still in its infancy, digital humanities research supported by big data and deep learning has become a hot topic in recent years. Researchers began to use digital methods to study cultural issues quantitatively, such as examining cultural evolution (Lewens 2015 ) through the diachronic changes of n-gram frequency (Michel et al. 2011 ; Lansdall-Welfare et al. 2017 ; Alshaabi et al. 2021 ; Newberry and Plotkin 2022 ) and word-level semantics (Newberry et al. 2017 ; Garg et al. 2018 ; Kozlowski et al. 2019 ; Giulianelli et al. 2020 ). This trend also spread to the study of ancient civilizations. Scholars from different cultural backgrounds have investigated the culture of ancient Rome (Dexter et al. 2017 ), ancient Greece (Assael et al. 2022 ), and Natufian (Resler et al. 2021 ) with the assistance of computer technology. It is acknowledged that ancient China was one of the longest-standing civilizations in human history, with a culture that evolved over the past thousands of years. Various ancient literature has been handed down over time, providing extensive textual records of Chinese culture. With the digitized versions of these classics, we can gain a glimpse into the cultural evolution in ancient China.

Ancient Chinese classics are highly intertextual texts. Since the doctrine “A transmitter and not a maker, believing in and loving the ancients” proposed in Analects (Legge 1861 . VII.I), quoting previous texts became a convention of literary creation in ancient China. Chinese scholars have long studied this cultural phenomenon from different perspectives. For example, Pan-ma i-t’ung (published around AD 1200) demonstrated the character differences between two history books, Records of the Grand Historian (published around 91 BC) and Book of Han (published around AD 82). Since Qing Dynasty, scholars began to enumerate parallel intertextual associations between ancient classics (Chen 1989 ; He et al. 2004 ). However, intertextuality (Kristeva 1980 ) is not only the connections of words and phrases but also manifests at higher levels hierarchically (Riffaterre 1994 ; Alfaro 1996 ), such as document, author, and community. The traditional form of high-level intertextuality studies was the overall literary criticism by scholars. For example, Ming dynasty scholar Ling Zhilong compiled previous scholars’ literary criticism of the above two history books. Literary criticism was themed on the style, skill, and viewpoints of literature, which was seen as a formidable endeavour due to the complexity of Chinese culture. Both parallel enumeration and literary criticism are limited by the reading and memory of scholars, which restricts the discussion on the large-scale corpus. Assisted by computer technology and digital literature, scholars recently began to study intertextuality within large-scale data.

Various natural language processing (NLP) methods have been applied to the intertextuality modelling of ancient literature. The previous automatic detection methods of text-level intertextuality aimed to discover similar phrases or sequences by lexical matching approach (Lee 2007 ; Coffee et al. 2012a ; Coffee et al. 2012b ; Ganascia et al. 2014 ; Forstall et al. 2015 ), which are insufficient and rigid in semantic modelling. The non-literal feature like synonym (Büchler et al. 2014 ; Moritz et al. 2016 ) and rhythm (Neidorf et al. 2019 ) also implies intertextuality, yet it requires language-specific design. Topic modelling lends a hand to passage-level modelling (Scheirer et al. 2016 ), while its dependence on expert annotation limits its generalization on diverse corpora. Simple statistics on text-level results contribute to document-level modelling (Hartberg and Wilson 2017 ). However, it ignores their overall connections. Besides, graph structure seems to be an appropriate way for the community-level modelling of intertextuality (Romanello 2016 ; Rockmore et al. 2018 ). Intertextuality modelling on classical literature widely supports cultural studies, such as quantitative literary criticism and stylometry (Forstall et al. 2011 ; Burns et al. 2021 ). Existing related studies on Chinese literature were limited to the detection methods (Liang et al. 2021 ; Li et al. 2022 ; Yu et al. 2022 ) and shallow studies of intertextual texts on small corpora (Sturgeon 2018a ; Sturgeon 2018b ; Huang et al. 2021 ; Deng et al. 2022 ), short of macroanalysis (Jockers 2013 ) on Chinese culture.

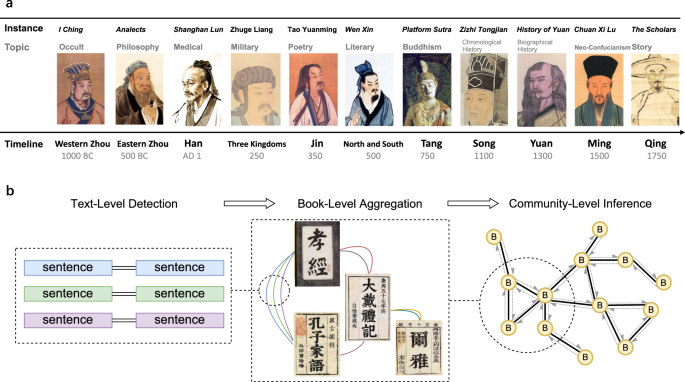

In this paper, we conducted a macroanalysis of ancient Chinese culture on an unprecedented large-scale corpus spanning nearly 3000 years. Figure 1a presents a schematic of this corpus. This corpus consists of 30,880 articles from 201 ancient Chinese books (or anthologies). It covers various topics, such as philosophy, religion, and politics, including the famous works of major cultural groups (e.g., Analects of Confucianism; Tao Te Ching of Taoism). The history books (e.g., Book of Han) and comprehensive anthologies (e.g., Collected Works of Han) of each era are also involved.

a The dataset of ancient Chinese literature with an instance in each era. The names of the dynasties and the approximate AD years are marked on the timeline. For each period, it gives one instance book and indicates its subject. b Hierarchical framework with three modules for multilevel intertextuality modelling.

In this work, we modelled ancient Chinese literature with a hierarchical framework. The cultural thought of civilization is composed of multiple levels, such as doctrines, individuals, and communities. Moreover, cultural evolution manifests hierarchically with microevolution and macroevolution (Mesoudi 2017 ; Gray and Watts 2017 ). A comprehensive discussion of cultural evolution requires multilevel perspectives. Therefore, this framework models intertextual associations from the text level to the community level with three modules. A schematic of the framework is shown in Fig. 1b . The text-level detection module tracks intertextual sentences with deep-learning models. The book-level aggregation module gathers text-level clues and abstracts various books into an association graph. The community-level inference module applies topological propagation to explore intertextual associations in the cultural community. After the modelling, millions of intertextual sentence pairs and a book-level intertextual association graph are ready for cultural analysis.

In the experiment, we detected 2.6 million pairs of intertextual sentences and then built them into an association graph. For a specific text collection, its intertextual distribution refers to its quantitative intertextual associations with other texts. Based on the modelling results, we can study ancient Chinese culture through the intertextual distribution among ancient literature.

In the cultural analysis, we considered cultural evolution from the perspective of cultural groups and religions. Schools of thought and religions were part and parcel of ancient Chinese culture (Schwartz 1985 ). The Hundred Schools of Thought that originated in the axial age were the prototype of ancient Chinese philosophy (Graham 1989 ). They rose and fell over the millennia that followed. The introduction of foreign cultures, like Buddhism (Chen 1964 ), also influenced the evolution of native culture. In this paper, we disentangled the cultural evolution of ancient China on three levels: (1) The interaction between individual scholars and philosophical schools; (2) The rise and fall of schools in Chinese history and culture; (3) The cross-culture communication with Buddhism.

Specifically, we validated several acknowledged cultural phenomena: the evolutionary paths of Confucianism and Taoism, and the booms and declines of the Hundred Schools of Thought. We also provided quantitative suggestions for cultural problems that are yet to be definitely resolved, such as the school attribution of Lüshi Chunqiu , the authorship attribution of Collected Works of Tao Yuanming , and the influence of Confucianism and Taoism across different cultural domains. Furthermore, we quantitatively discussed the interaction between Buddhism and native culture, revealing how cultural integration has evolved over time.

In addition, we have developed an online platform to display this corpus, along with millions of intertextual associations detected in this work. The platform supports custom data analysis, which encourages researchers and enthusiasts to gain insight into this work.

Two datasets were built respectively, the classic dataset and the era-text dataset. We considered several factors when building the dataset: era balance, representativeness, and official-folk balance. Two datasets consist of 30,880 articles from 201 books (or anthologies).

Classic dataset

The classic dataset is composed of the most prominent and influential books that represent the core culture of ancient China. Before the Tang Dynasty (618–907), literature was copied manually. Due to the long history and the limitations of publishing technology, only time-tested classics have been handed down to this day. Therefore, we added all the collected pre-Tang literature to the classic dataset. In the Tang Dynasty, the invention of block printing led to the rapid development of the publishing industry, resulting in explosive growth in the amount of literature. Until the mid-18th century, China printed more books than the rest of the world combined (Gernet 1996 ). Considering that this study focuses on the evolution of early thought in ancient China, we selected several most famous classics after Tang Dynasty. The well-known digital library of ancient Chinese classics, CTEXT ( https://ctext.org/ ), also adopted similar rules to build a collection of core classics. We considered the literature samples of CTEXT and built the classic dataset.

Our research focuses on ideological evolution, so books in the classic dataset should reflect cultural thought with good data quality. Therefore, we further screened the classic dataset to filter out inappropriate books, including commentary books, mathematics books, dictionaries, excavated literature (e.g., Mawangdui Silk Texts), and lengthy novels.

Finally, the dataset of ancient Chinese classics contains 133 books, including 8984 articles. Table 1 shows the time-period statistics of this corpus. It covers various aspects of culture, such as philosophy, mythology, politics, and religion. In this dataset, the earliest book was created around 1000 BC (e.g., Book of Documents), while the latest book was published around AD 1750 (e.g., The Scholars).

Era-text dataset

We aim for the era-text dataset to reflect the contemporary culture of each period, encompassing both official and folk traditions. To achieve this, we set our sights on history books and anthologies. As ancient China had a tradition of producing history books for each dynasty, history books typically reflected official attitudes. We added the official history (Twenty-Four Histories), large-scale chronicle history books ( Zizhi Tongjian and Continued Zizhi Tongjian Changbian ), and 15 other influential history books to the era dataset. In addition, we included Quan shang gu san dai Qin Han San guo Liu chao wen , a series of large-scale anthologies organized by era. It collected a wide variety of works from numerous authors, including prose, essays, religious scriptures, inscriptions, etc. These anthologies comprehensively record the contemporary culture of ancient China. To further enrich the era-text dataset, we added 13 well-proofread anthologies.

We categorized these history books and anthologies by era. For history books (e.g., Zizhi Tongjian ) that cover multiple eras, we divided them into corresponding eras. Finally, we got 55 history books and 13 anthologies, containing 21,896 articles. Table 2 shows the time-period statistics of this corpus. These works chronicle Chinese history and culture from the legendary period (e.g., Bamboo Annals , from 2600 BC) to the Ming Dynasty (e.g., History of Ming , ending in AD 1644).

Data processing

Ancient Chinese characters may have multiple written forms, we use the open-source toolkit OpenCC ( https://github.com/BYVoid/OpenCC ) to map them to a unique root character before encoding them using deep learning models. The maximum sentence length was set to 50 characters. Sentences exceeding this length were divided into two sentences. This setting can cover more than 99% of sentences.

Intertextuality detection usually aims to discover meaningful textual connections. It is important to note that texts without actual meaning cannot indicate the ideological connection between texts. Therefore, we use additional computational rules to avoid inappropriate text pairs. First, we filtered out sentences (clauses) with less than three remaining characters after removing the stopwords (such as prepositions and pronouns). Then, with predefined rules, we filtered out meaningless sentences, such as tone, dates, lengths, quantities, and formats. After filtering, there are about 436,000 sentences with 840,000 clauses in the classic’s dataset, and 2,113,000 sentences with 4,526,000 clauses in the era-text dataset.

Challenge and limitation

The collection and processing of ancient Chinese literature present challenges and limitations. Although we used punctuated text in this work, the original ancient Chinese literature has no punctuation. When it comes to no-punctuation data, an automatic punctuation model should be applied beforehand. Moreover, ancient literature could have multiple versions. In our dataset, we opted to include only one widely circulated version of each book. It may restrict the applicability of the dataset for researchers interested in different versions.

Additionally, the selection of appropriate literature collections for cultural analysis from a vast pool of ancient literature requires expert knowledge. In our study, humanities scholars specializing in Chinese history and philosophy were consulted.

Modelling framework

Considering that intertextuality and cultural evolution can manifest at multiple levels, we developed a hierarchical framework to analyze ancient literature. This framework captures intertextuality at three levels, ranging from micro to macro. At the text level, similar sentence pairs shared between books are detected by deep neural networks. At the book level, books are abstracted into an intertextual association graph based on the text-level results. At the community level, information propagates through the topological structure of the book-level graph, thus exploring intertextuality in the cultural community. This hierarchical approach provides both micro-evidence and macro-quantification for intertextual associations and cultural evolution.

Text-level detection

The study of cultural evolution is concerned with the connections of thoughts. Each sentence often expresses a distinct thought, making it a suitable quantitative unit. Therefore, we traced the intertextuality at the sentence level. We considered that the more similar sentences the two books share, the more closely connected they are.

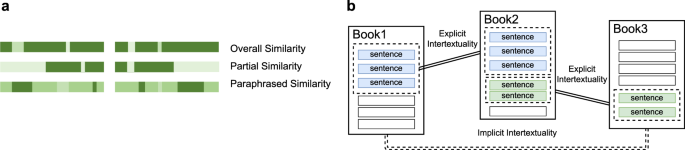

The dissemination of text is not static but mutates. The micro-evolution of texts has multiple patterns (Tamariz 2019 ), such as replication, expansion, and succession. Therefore, this module traced similar sentence pairs shared between books with three patterns: overall similarity, partial similarity, and paraphrased similarity. A sketch is given in Fig. 2a .

a Three patterns of similarity between sentences. Darker colour indicates more similar text. b The explicit intertextuality and implicit intertextuality between the three books.

Overall similarity

Two sentences explain the similar meaning with close language expressions.

Partial similarity

Two sentences share similar parts.

Paraphrased similarity

The similar meaning is explained by different language expressions. The text may be disrupted and reorganized.

Deep neural networks (Vaswani et al. 2017 ) and pre-train methods (Devlin et al. 2019 ) have shown excellent performance in text feature extraction. Contrastive learning (Chen et al. 2020 ) can help to obtain personal-defined text similarity models without supervision, which is suitable for text-level intertextuality detection. To get sentence representation for these three patterns, we introduced the RoBERTa base (Liu et al. 2019 ), a pre-trained language model that can be further fine-tuned for our task using different training strategies.

For the overall similarity pattern, it can be treated as the overall semantic similarity between sentences. To train the model 1 , we used SimCSE (Gao et al. 2021 ), a contrastive learning method for extracting sentence embeddings.

For the paraphrased similarity pattern, the sentence structure could be reconstructed. We trained another model 2 for this pattern, with its loss being a weighted sum of loss 1 and loss 2 . The loss 1 was calculated in the same way as for model 1 .

For loss 2 , we randomly dropped and shuffled the clauses and n-grams in the original sentence to obtain a new sentence. It serves as another positive sample of contrastive learning. Negative samples are other sentences in the batch. The final loss for the model 2 is:

r is a hyperparameter that modulates the emphasis between sentence structure and semantics.

For the partial similarity pattern, sentences are considered similar if they share similar clauses. We detected similarities at the clause level using both model 1 and model 2 .

In large-scale information retrieval, brute-force search is often impractical due to the time and resources required. Therefore, it usually follows a multi-step process for the balance of precision and efficiency.

The first step is to recall potential candidates. In our work, we identified K members that were most similar to each sentence embedding. Then, we selected appropriate candidates and calculated a threshold to further filter out similar candidates.

For each pattern, we used the following steps to detect:

1. Extract embeddings of all sentences using the RoBERTa model.

2. De-duplicate embeddings. For each embedding, find its Top K similar embeddings. Denote all embedding pairs obtained as P .

3. Calculate the Euclidean distance of embedding in P and find the t th percentile as the similarity threshold d thr .

4. Filter out sentence pairs whose embedding distance is closer than d thr .

We detected similar pairs with these three strategies separately and gathered their results. The detected similar sentence pairs give concrete evidence of text-level intertextuality.

Book-level aggregation

Text-level results can support textual research on microevolution. However, to analyze at the macro level, text-level results must be gathered and aggregated. In this module, we aggregated text-level intertextuality results and synthesized them into a book-level intertextual association graph g . In this graph, each node B i represents a book, and there are N books in total. The edges indicate the intertextual associations between books. Suppose there are two books B i and B j , they contain n i and n j distinct sentences, respectively, and s ij distinct similar sentence pairs were detected between them. The edge weight α ij between B i and B j is calculated as follows:

For node B i , it has a one-hot node feature \(x_i = [x_{i1},x_{i2} \ldots x_{iN}]\) , where \({x_{ii}} = {1}\) .

Community-level inference

Text-level intertextuality can be observed explicitly. However, some intertextual connections can be implicit, with no direct textual association. In this study, we treated these classics as a cultural community and explored the implicit intertextuality at the community level. A schematic is shown in Fig. 2b .

Explicit intertextuality

If two books share similar sentences, they are explicitly intertextual.

Implicit intertextuality

If Book 1 and Book 2 are explicitly intertextual, and Book 2 and Book 3 are explicitly intertextual, then it can be inferred that Book 1 and Book 3 are implicitly intertextual.

This module performs inference by propagating and aggregating information through the topology of the intertextual association graph:

The first operation gathers explicit intertextuality I ex to the node feature. The second operation infers and integrates the implicit intertextuality I im . r ′ is a custom weight that adjusts the emphasis of implicit intertextuality. After twice graph computations, the node feature of B i is \(y_i = [y_{i1},y_{i2} \ldots y_{iN}]\) , where y ij indicates the united intertextual score I ij between B i and B j .

The node feature reflects the distribution of intertextuality for each book within the community. Excessive aggregation of information on the graph can lead to over-smoothing, which is detrimental to node features. Therefore, we set the number of graph computations to twice. Sparsity is an issue that often plagues text-based cultural analysis. With this method, the sparsity of intertextuality detection results can be alleviated.

Settings and modelling results

In text-level detection, we trained the model on an Nvidia 1080ti GPU. The optimizer is Adam (Kingma and Ba 2015 ). We took the pre-trained ancient Chinese RoBERTa base model as a basis. For both model 1 and model 2 , we fine-tuned the base model 10 epochs at a learning rate of 1e-6. The batch size was 32. The r for the loss of model 2 was set to 0.2. For similarity detection, we set K to 100 and t to 1 based on our data scale and observations. The large-scale vector searching tool Faiss (Johnson et al. 2019 ) was applied to speed up vector retrieval.

In book-level aggregation, we found that diverse genres have variant punctuation styles, disturbing the total number of sentences. After observation, we found that in this dataset, the number of sentences with at least two clauses is relatively stable. Therefore, we set the number of sentences n i of the book B i to the number of sentences with at least two clauses.

In community-level inference, r ′ was set to a value that makes implicit intertextuality one-fifth of explicit intertextuality. \(x_i^\prime\) and I im were clipped with a ten-fold mean. In the modelling after adding era-text, the information propagation between era-text nodes was blocked to evaluate each era independently.

As a result, the detection module identified over 411,000 pairs of similar sentences between classics and 2,209,000 pairs between classics and era-text. An intertextual association graph was built from these pairs.

Manual evaluation of text-level detection

Note that in this corpus, each sentence has millions of intertextual candidates from books on diverse topics. As a result, the likelihood of any two sentences being intertextual is extremely low. Building a hand-labelled test set to evaluate the recall rate is nearly impossible. Therefore, we manually evaluated the accuracy rate with the same number of recalled sentences.

We invited three people with graduate degrees and research experience in Chinese classical literature to conduct the manual evaluation. The evaluators were asked to assess the intertextuality of each detected sentence pair. If the two sentences share a similar meaning, topic, or structural style, give 1 point. Otherwise, give 0 points. We took the single-pattern methods as baselines. We used the SIMCSE (Gao et al. 2021 ) model to detect the same number of pairs at the sentence and clause levels, respectively. One pair is randomly sampled from each book in the dataset of classics. There are three groups with 133 pairs each.

The results are shown in Table 3 . The average accuracy of our proposed multi-pattern detection model is 82.22% ( Pearson ’ s r = 0.74), while the single-pattern baseline is 73.70% and 45.92%. It suggests that the multi-pattern design can improve intertextuality detection performance.

Ablation of community-level inference

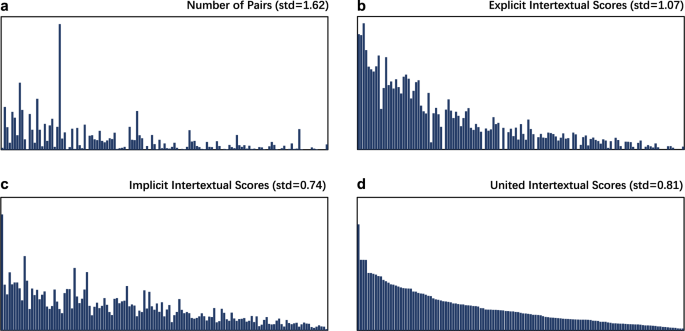

We performed an ablation study on a specific book to validate the designed inference module. Figure 3 shows the intertextual connection between Analects and other classics. To compare the modules fairly, we adjusted the weights r ′ so that explicit and implicit intertextuality have equal status in united intertextuality.

They are mean-normalized, and their standard deviations are given respectively. a Number of similar sentence pairs s . b Explicit intertextual scores I ex . c Implicit intertextual scores I im . d United intertextual scores I .

The number of similar pairs varies widely due to the varying length of books. After aggregation, normalized explicit intertextual scores are obtained. However, some books do not share similar sentences, resulting in vacancies. Implicit intertextual scores are positively correlated with explicit intertextuality. It fills the gap of explicit intertextuality and alleviates sparsity. In addition, the introduction of implicit intertextuality brings smoothness, leading to more robust united intertextual scores ( std = 0.81) than explicit intertextual scores ( std = 1.07).

Indicator robustness

A metric that is susceptible to data variance is not ideal. Therefore, we examined these two concerns regarding the intertextual score I :

• Q 1 : Is the intertextual score affected evidently by data size?

• Q 2 : Does the intertextual score decrease noticeably due to language discrepancy in different eras?

For Q 1 , we calculated the correlation between data size and intertextuality with the classic dataset. The two variables used in the correlation calculation are as follows:

Data Size: the number of sentences involved in intertextuality detection for each book.

Intertextual Score: The average intertextual score of each book with all other books.

Our results show that there was no significant correlation between data size and intertextual score ( \(r = - 0.1427,\,P = 0.1025,\,n = 133\) ). Therefore, we considered that the decrease in the H index is not due to data size.

For Q 2 , let us examine some cases. Jin Si Lu of the Song Dynasty (published around 1175) and Chuan Xi Lu of the Ming Dynasty (published around 1472–1529) are two famous works of Neo-Confucianism, which emerged as a continuation of Confucianism thousands of years after its birth. Compared with previous books, is the intertextuality between these two books and Confucianism prominent?

To answer this question, we ranked the intertextual scores between all books and keystone works of Confucianism and observed where these two books are placed. We found that these two books rank highly (1/131, 2/131), even surpassing Confucian books that are more recent to the Axial period. Therefore, we consider that language differences across different eras do not have an obvious impact on the intertextual score.

Through these two examinations, we can conclude that the indicator, intertextual score I , is robust to data variance.

Study 1. Interaction between scholars and schools

At the first level, we discussed the interaction between scholars and schools. Schools can be remoulded by later generations of scholars during their thousands of years of evolution. Confucianism and Taoism were the most influential philosophical schools in ancient China. We examined their evolutionary paths by assessing the preference of their followers through intertextual distributions of literary works. Besides, some literature is controversial or ambiguous in the mists of antiquity. To clarify the true path of cultural evolution, we provided quantitative suggestions for the school attribution of Lüshi Chunqiu and the authorship attribution of the Collected Works of Tao Yuanming .

In the axial age, religion and philosophy transformed drastically in various civilizations. The Hundred Schools of Thought, which arose in the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (500 BC), were the prototype of Chinese philosophy. The enduring and pervasive influence of schools such as Confucianism, Taoism, Mohism, Legalism, and Military make them essential to any discussion of ancient Chinese culture (Sima 1959 ; Ban 1962 ).

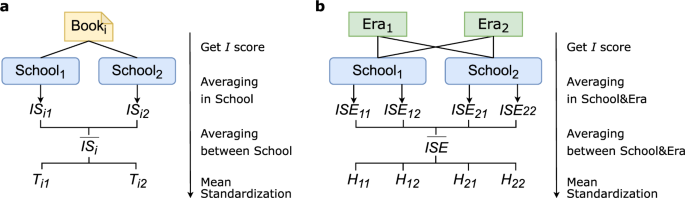

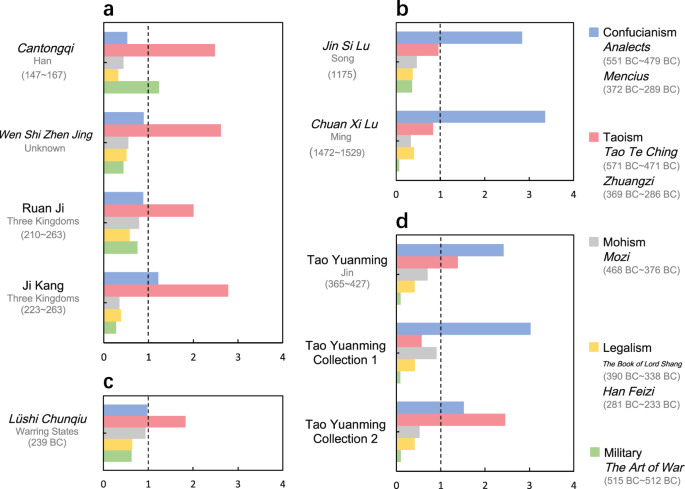

Scholars and schools are symbiotic. Scholars were inevitably exposed to mainstream schools of their periods, while the doctrines of schools needed to be passed down to subsequent scholars. In this section, we investigated the interaction between scholars and schools through the intertextual associations of their literature. We calculated the Tendency Index T between 125 ancient Chinese classics and the five schools mentioned above. This index shows the ideological tendency of a particular collection of texts toward each school. The schematic diagram of this index is shown in Fig. 4a , and the details of its design are as follows.

a Calculation of Tendency Index T . b Calculation of Historical Status Index H .

Based on the consensus of Chinese philosophy (Feng and Bodde 1948 ), we selected the keystone works as the benchmarks for each school. We first calculated the average intertextual score between a book and the keystone works of each school. The Tendency Index is defined as the ratio of the average intertextual score with a specific school to its means across all schools. Suppose there are books \(B = \{ B_1,B_2 \ldots B_m\}\) and schools \(S = \{ S_1,S_2 \ldots S_v\}\) . The intertextual score between any two books B i and B j is I ij , which can be obtained from the node features of the association graph. For the book B i and the school S k , the school S k has l keystone works, T ik is calculated as follows:

T ik reflects the tendency of book B i for school S k compared to other schools. When T ik > 1, Book B i has an above-average preference for school S k .

We also examined the significance of text-level intertextuality. Specifically, we investigated whether sentences from a specific book have a significantly greater probability of being detected in the keystone works of a school than the average of other schools. Considering that these books typically contain a large number of sentences \(({\text{Median}} = 2739)\) , we employed a one-tailed Z -test statistic. This statistic was constructed from the similar sentence pairs detected. Suppose there are books B i and B j containing n i and n j sentences after data processing. There are s ij distinct similar sentence pairs detected between them. For book B i and school S k , the calculation of test statistic Z is as follows:

We set the significance level α to 0.05. With the Tendency Index and P-value , we developed quantitative discussions on the scholar-school linkages.

Evolutionary path of philosophical schools

The schools in ancient China were constantly evolving as scholars reshaped previous theories. As acknowledged in the history of Chinese philosophy (Feng and Bodde 1948 ), the original Taoist philosophy inspired the Taoist religion and Wei Jin metaphysics, while Neo-Confucianism inherited the theories of Confucianism. This section validates these evolutionary paths of Taoism and Confucianism quantitatively.

Taoism was a philosophical school that mainly advocated conformity to nature. Taoist religion evolved from Taoist philosophy, developing into the most prominent native religion until now (Raz 2012 ). The representatives of Taoist philosophy, Laozi and Zhuangzi, were revered as the founder and patriarch of the Taoist religion respectively. Figure 5a shows the Tendency Index of two Taoist religious classics, Cantongqi and Wen Shi Zhen Jing . They were significantly inclined towards Taoist philosophy ( Cantongqi , \(T = 2.48\) , \(P = 0.0142\) , \(n = 529\) ; Wen Shi Zhen Jing , \(T = 2.62\) , \(P = 0.0019\) , \(n = 879\) , for Taoism). It demonstrates the consistency between Taoist religion and Taoist philosophy in their evolution.

The dynasty of publication and the corresponding AD years of each book are shown below. The keystone works of each school are listed on the right, including the time of the publication. a Tendency Index of two Taoist classics, Cantongqi and Wen Shi Zhen Jing . And the Tendency Index of the collected works of two scholars, Ruan Ji and Ji Kang. b Tendency Index of two Neo-Confucianism classics, Jin Si Lu and Chuan Xi Lu . c Tendency Index of Lüshi Chunqiu . d Tendency Index of the Collected Works of Tao Yuanming . And the Tendency Index of its widely accepted and controversial parts.

Apart from the religious re-creation, Taoism inspired a new school of philosophy. Wei Jin metaphysics, a variant of Taoist philosophy, arose during the Three Kingdoms period (220–280) and flourished in the Jin Dynasty (266–420). Ruan Ji and Ji Kang were two representative scholars. Figure 5a shows the Tendency Index of their collected works. Compared with the other four schools, scholars of Wei Jin metaphysics were closer to the theories of Taoism ( Collected Works of Ruan Ji , \(n = 1590\) ; Collected Works of Ji Kang , \(P = 3.57e - 06\) , \(n = 2209\) , for Taoism).

This kind of transformation also occurred in Confucianism. Confucianism, which originated in 500 BC (Yao 2000 ), had an extensive impact on ancient Chinese culture and spread throughout East Asia. Over millennia, the philosophy evolved, and Neo-Confucianism became the new representative of Confucianism in the Song Dynasty (960–1279) and Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) (Bol 2008 ). Jin Si Lu and Chuan Xi Lu , written by Zhu Xi, Lv Zuqian, and Wang Yanming, were two of the most famous classics. Their Tendency Index is shown in Fig. 5b . The significant intertextual connection between the two works and Confucianism confirms their inheritance ( Jin Si Lu , \(T = 2.84\) , \(P = 1.01e - 13\) , \(n = 2914\) ; Chuan Xi Lu , \(T = 3.36\) , \(P = 2.33e - 15\) , \(n = 2495\) , for Confucianism).

Controversial literature attribution

Because of its antiquity, the information of some classics has become vague over thousands of years of circulation. Attributing ancient literature to appropriate schools and original authors has been a long-discussed issue in Chinese cultural studies, and in recent times, scholars have embarked upon quantitative investigations in this regard (Zhu et al. 2021 ; Zhou et al. 2023 ). In this section, we provide quantitative suggestions for controversial literature based on its intertextual distributions among schools.

Appropriate school attribution could contribute to the study of the influence and evolution of cultural thought. For example, Lüshi Chunqiu , an encyclopedic classic from the Warring States Period, was compiled in 239 BC with the support of the politician Lü Buwei. It brought together doctrines from various schools. However, there is no conclusion about its predilection among them (e.g., Syncretism theory, Taoism theory, and Confucianism theory (Chen 2001 )).

In Fig. 5c , our quantitative modelling result shows that Lüshi Chunqiu is a syncretic work ( \(T = 0.78\sim 1.43\) ) led by Taoism ( \(T = 1.43\) , \(P = 0.0004\) , \(n = 6118\) , for Taoism). It indicates that the editors have done a syncretic compilation of the theories in that period, with a slight inclination toward Taoism.

The variation of intertextual distributions can also be applied to controversial authorship attribution. Some ancient books were published in the name of famous scholars, but the real authors maybe someone else. However, the creations by different people have their own styles. The thought divergence between the real celebrity and their impostor could be implied in the intertextual variation of their works.

For example, Tao Yuanming is widely recognized as a representative of Chinese individual liberalism (Swartz 2008 ). He refused to serve the government and pursued a pastoral life. His yearning for a free life was depicted in his poems, which is highly consistent with the claim of Taoism. He is considered to have a strong predilection for Taoism and was slightly affected by Confucianism. Therefore, it is puzzling to find that the Tendency Index shown in Fig. 5d indicates a significant predilection for Confucianism in the Collected Works of Tao Yuanming ( \(T = 2.41\) , \(P = 0.0007\) , \(n = 2119\) , for Confucianism).

Further investigation revealed that the authorship of some parts of the Collected Works of Tao Yuanming is controversial. The version compiled by Xiao Tong (501–531) did not contain Five Sets of Filial Piety Biographies and Book of Ministers , while the version of Yang Xiuzhi (509–582) added them. Yang Xiuzhi mentioned in the preface that Xiao Tong’s version was missing these two parts, so he added them to prevent them from being lost in future generations.

However, later scholars gradually became suspicious of these two parts. The most famous one is the assertion in Siku Quanshu (Ji 1997 ). For its “self-contradictory” and “meaningless”, Siku Quanshu declared that Five Sets of Filial Piety Biographies and Book of Ministers were counterfeit. This view remains popular today, owing to the authority of Siku Quanshu .

To find clues to this dispute, we compared the intertextual distributions of the widely accepted and controversial parts. We divided the Collected Works of Tao Yuanming into two parts: collection 1 included Five Sets of Filial Piety Biographies and Book of Ministers , while collection 2 contains the remaining works. The Tendency Index for the two collections is shown in Fig. 5d . The “Tao Yuanming” of collection 1 exhibited a significant preference for Confucianism ( \(T = 3.02\) , \(P = 0.0002\) , \(n = 436\) , for Confucianism), while the “Tao Yuanming” of collection 2 inclined towards Taoism ( \(T = 2.45\) , \(P = 0.0658\) , \(n=1683\) , for Taoism) and has an above-average preference for Confucianism ( \(T = 1.51\) , \(P = 0.1985\) , \(n = 1683\) , for Confucianism). The modelling result of collection 2 is consistent with the actual behaviours and mainstream cognition of Tao Yuanming.

The Tendency Index shows an antithesis between the controversial sections and other parts in terms of their intertextual connections to Confucianism and Taoism. Considering the life experience of Tao Yuanming, our finding lends further support to the speculation: Five Sets of Filial Piety Biographies and Book of Ministers were forged by others in the name of Tao Yuanming.

Nevertheless, it is also worth considering that these two books were intended as textbooks for family education. If we treat them as the original works of Tao Yuanming, the intertextual discrepancy in the results reveals the divergence between the personal pursuits of Tao Yuanming (Taoism) and his aim to educate future generations (Confucianism).

Study 2. Vicissitudes of schools

At the second level, we studied the rise and fall of schools in different eras and domains. Scholars have employed character co-occurrence (Yang and Song 2022 ), syntactic patterns (Lee et al. 2018 ), and topic analysis (Nichols et al. 2018 ) to quantitatively measure the grammatical and ideological connections in ancient Chinese literature, thus supporting research into cultural differences and thought evolution. In this section, we studied cultural phenomena through diachronic and field-specific intertextual distributions. We investigated quantitative evidence for the connections between historical events and school status. Besides, schools’ claims have their own focus, making them favoured by different aspects of culture. We quantitatively discussed the status of Confucianism and Taoism in various cultural domains.

To achieve this, we divided ancient China into 12 eras and built an era-text corpus from history books and anthologies. The era-text corpus is a comprehensive collection of literature from official and folk sources, allowing them to be taken as indicators of the prevailing thought of that time. The era-text was then classified into 12 eras and added to the intertextuality modelling. For a specific collection of text, its intertextual association with the era-text implies its popularity in that era. The Historical Status Index H was designed to measure the school status in each era. The schematic diagram of this index is shown in Fig. 4b , and the details of the calculation are as follows.

We first calculated the average intertextual score between the keystone works of each school and the era-text in each era. For each school, its index H is defined as the ratio of the average intertextual score in a specific era to its mean across all eras and schools. Let \(S = \{ S_1,S_2 \ldots S_v\}\) denote the set of schools, and \(E = \{ E_1,E_2 \ldots E_f\}\) denote the set of eras. For a given school S k and era E e , where school S k has l keystone works and era E e has c books in era-text, the Historical Status Index H ke is calculated as follows:

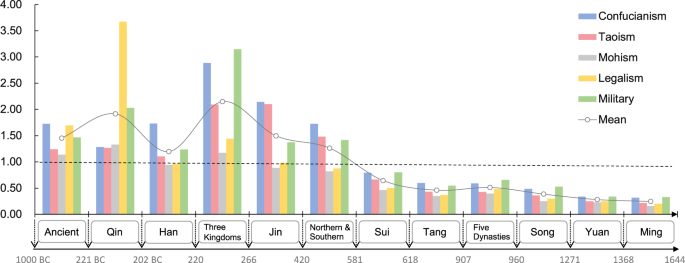

H ke reflects the status of school S k in the era E e . If its mean value \(\bar H\) in era E e exceeds 1.00, it suggests that the school had an above-average influence in era E e . The Historical Status Index of five schools in 12 eras is shown in Fig. 6 .

The timeline gives the name of each era, with the approximate AD years of its beginning and end. The histogram shows the H of each school, while the line chart indicates its mean value in each era.

School transformation in history

As society changed, schools of thought experienced booms and declines in Chinese history. Historical events like wars, policies and regime changes have impacted the school’s evolution. In this section, we investigated the quantitative textual evidence of these connections through the diachronic changes in their intertextual distributions.

The results show that the keystone classics of these five schools were highly intertextual with era-text within about a thousand years ( \(\bar H > 1\) ) and then gradually decreased ( \(\bar H < 1\) ). Although the original texts created during the axial period were still classic, they gradually became unsuitable for the new era (Feng and Bodde 1948 ). This could be the reason for the decrease in the \(\bar H\) index. Throughout the millennium of prosperity, we can observe the connections between school transformation and historical events.

The popularity of the school of Military was affected by the division of the country in the Three Kingdoms period (220–280), when China was divided into three comparable kingdoms. The country was in turmoil, and wars often broke out between these three kingdoms. Against this background, the school of Military, which was themed on the philosophy of war, reached its heyday ( \(H = 3.15\) , for Military in the Three Kingdoms period).

The linkage between political events and the prosperity and decline of the school manifested in the quantitative results. Confucianism was a school of humanism (Juergensmeyer 2005 ), while Legalism was a school that advocated legal institutions. Some scholars believe that ancient China was influenced by both Confucianism and Legalism (Zhou 2011 ; Zhao 2015 ). In Qin (221 BC - 207 BC) and Han (202 BC - 220) Dynasties, favour from the government made two schools stand out rapidly. The Shang Yang Reform (356 BC & 350 BC) and the advocation from the emperor Qin Shi Huang brought Legalism to a peak in the Qin Dynasty ( \(H = 3.67\) , for Legalism in the Qin Dynasty). However, this brief prosperity ended with the demise of the Qin Dynasty. The policy implemented in the Han Dynasty, which banned other philosophical schools and venerated Confucianism, caused the drop of \(\bar H\) and made Confucianism ( \(H = 1.73\) , for Confucianism in the Han Dynasty) exceed others ( \(H = 0.94\sim 1.23\) , other schools in the Han Dynasty). This advantage continued since then, and Confucianism had long been the dominant philosophical school in ancient China.

School influence in various domains

Confucianism and Taoism were representative schools of collectivism and individualism in ancient China (Munro 1985 ). As the two most prominent native philosophical schools, Confucianism and Taoism have often been compared. In this section, we studied the influence of Confucianism and Taoism through their intertextual distributions among various cultural domains.

Confucianism placed greater emphasis on family and social relations, whereas Taoism focused more on nature and the spirit. For most of the time since the Han Dynasty (202 BC - 220), Confucianism was far superior to other schools of thought. Nevertheless, there was an anomaly in history. As shown in Fig. 6 , Taoism experienced a revival from the Three Kingdoms period (220–280) to the Jin Dynasty (266–420). In the Jin Dynasty, the status of Confucianism ( \(H = 2.14\) , for Confucianism in the Jin Dynasty) and Taoism ( \(H = 2.10\) , for Taoism in the Jin Dynasty) was very close. It stemmed from the collapse of the Han Dynasty, which advocated Confucianism. During this period, people sought to find a successor from the theories of other schools (Feng and Bodde, 1948 ). In the background, Wei Jin metaphysics developed from Taoism theory. However, this prosperity did not last long. After the brief revival, Taoism decayed while Confucianism remained the mainstream.

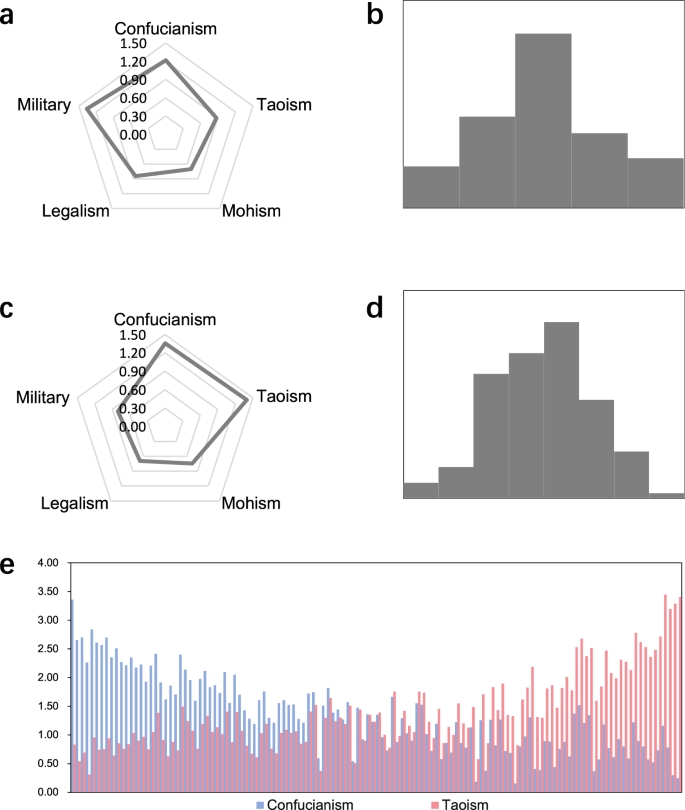

In addition to the diachronic investigation, we discussed the status of Confucianism and Taoism in different cultural domains according to their intertextuality with texts on related topics. History books in ancient China tended to record political events. Therefore, we took the intertextual associations with history books to indicate the political status of a school. The average Tendency Index of history books is shown in Fig. 7a . We also test whether the Tendency Index of Confucianism exceeds Taoism significantly with a one-tailed paired samples t-test. The distribution of their difference value is shown in Fig. 7b , which corresponds to normal distribution. The significance level α is set to 0.05. Confucianism exceeded Taoism significantly in the political domain ( \(P = 2.22e - 15\) , \(n = 55\) ).

a The average Tendency Index of history books. b Difference value distribution of Tendency Index between Confucianism and Taoism among 55 history books. c The average Tendency Index of 125 classics from various cultural domains. d Difference value distribution of Tendency Index between Confucianism and Taoism among 125 classics. e Tendency Index of 125 classics towards Confucianism and Taoism, sorted by their difference value.

Although Taoism did not replace Confucianism in the political domain, it is comparable to Confucianism in broader cultural communities. We calculated the average Tendency Index of 125 classics from various cultural domains, and the result is shown in Fig. 7c . We test whether their Tendency Index is variant with a two-tailed paired samples t -test. The distribution of their difference value is shown in Fig. 7d , which corresponds to normal distribution. The significance level α is set to 0.05. There is no significant difference between Confucianism and Taoism among these classics ( \(P = 0.8014\) , \(n = 125\) , not rejecting the null hypothesis). Specifically, Fig. 7e shows the Tendency Index of 125 classics towards two schools. Among these classics, Confucianism and Taoism had respective advocacy groups. Books on politics and regulations are highly intertextual with Confucianism, while books on mythology, occultism, and medicine are close to Taoism.

These indicators show that Confucianism has advantages in the political field, while Taoism attempted to surpass Confucianism yet failed. However, Taoism was on par with Confucianism in other fields of ancient Chinese culture. Thus, it is suggested that in ancient China, the political domain was the territory of collectivism, while individualism flourished in the diverse cultural fields.

Study 3. Communication with foreign culture

At the third level, we investigated the communication between ancient China and foreign cultures, with a focus on Buddhism, one of the most influential foreign religions in ancient China. The preaching of Buddhism experienced imitation and integration (Zürcher 2007 ). We started by identifying the native schools that are most intertextual with Buddhism and then discussed the different stages of the infiltration between Buddhism and native Chinese culture.

Although the dissemination of information in ancient times was much slower than it is now, ancient China had extensive communication with foreign cultures. As a result, the cultural evolution of ancient China was not isolated. Buddhism, a religion that originated in ancient India, spread to ancient China during Han Dynasty. Buddhist scriptures were translated into Chinese versions, which were widely disseminated over the next millennia.

In this section, we investigated the preaching of Buddhism in ancient China through the intertextual association between Buddhist scriptures and native classics. We selected the four most influential Buddhist scriptures in ancient China ( Diamond Sutra , Lotus Sutra , Shurangama Sutra , and Avatamsaka Sutra ) as the keystone work of Buddhism and added them to the modelling. The diachronic changes of intertextual distributions reveal the evolution of cultural integration in different stages. The topics of intertextual associations show the commonalities between Buddhism and native culture.

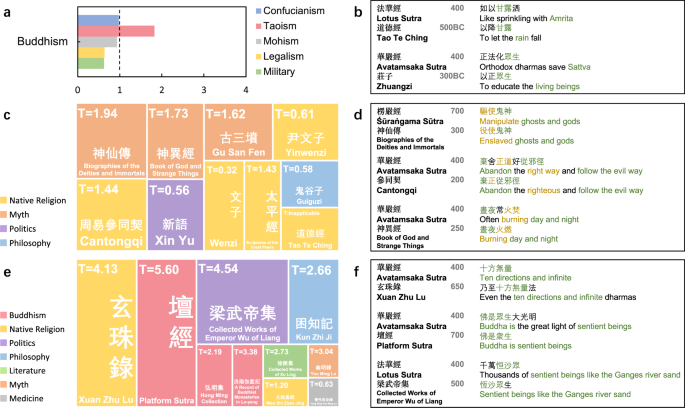

Analogue in native cultural groups

As a newly introduced religion, Buddhism inevitably interacted with the existing native cultural groups in its preaching. Taoist religion, which developed from Taoist philosophy, was the dominant indigenous religion in China. Scholars generally believe that Buddhism and Taoism imitated each other in many ways (Mollier 2008 ), including textual scriptures, image symbols, and organization. In this study, we concentrate on textual scriptures. Figure 8a shows the Tendency Index of Buddhist scriptures towards the five native schools. Taoism is the closest native school as expected ( \(T = 1.83\) , \(P = 0.0131\) , \(n = 62693\) , for Taoism).

Besides, we found that Buddhist scriptures borrowed language expressions from existing Chinese terms in the translations of Buddhist concepts. Figure 8b shows two cases from the detected intertextual sentences. The term “Amrita” (meaning “immortality drink”) was borrowed from the word “甘露“ (gan lu, meaning “sweet dew”) when translated into Chinese. This word refers to “rain” in the native Taoist classic Tao Te Ching . Similarly, the Chinese translation of “Sattva” (meaning “sentient beings”) employed the term “众生“ (zhong sheng, meaning “all living beings”), as found in the Taoist classic Zhuangzi .

Evolution of cultural integration

Apart from the philosophical schools, intercultural communication manifested in various aspects of society. Therefore, we expanded the horizons to broader cultural domains. In this section, we compared the intertextual associations between Buddhism and native literature before and after its introduction.

During the Jin Dynasty (266–420), these four Buddhist scriptures were translated into Chinese, paving the way for Buddhism to flourish in ancient China. After separating the texts before and after AD 420, we ranked native classics based on their intertextual scores with Buddhist scriptures. The top 10 classics are shown in Fig. 8c and e . We also juxtaposed Buddhism with five native schools and calculated the Tendency Index of these classics.

Before the introduction of Buddhism, its similar native classics often focused on myth and religion, implying that the Chinese version of Buddhist scriptures retained the original theme. Besides, it may attribute to their assimilation of the corresponding native literature in the Chinese translation of Buddhist scriptures. Specifically, three similar cases from the top three classics are shown in Fig. 8d . The Chinese version of Buddhist scriptures shares similar phrases with native myths in their discussions of mysteries, including the control of ghosts and gods, and the description of the mysterious phenomenon of “burning day and night”. It also mimicked the language expression of native religious discourses. For example, the description of the choice between justice and evil is highly consistent between Cantongqi and Avatamsaka Sutra .

After the introduction of Buddhism, Buddhist doctrines diffused into various domains of native culture. Compared to the previous period, there was an overall increase in the Tendency Index of Buddhism among the top 10 classics. It indicates the promotion of Buddhism’s influence on Chinese culture. One notable change is the emergence of three native Buddhist works. It symbolizes that Buddhism built its advocacy group in ancient China. These works remoulded Buddhism in a new cultural environment with localized doctrines. In addition to expanding its own religious territory, Buddhism integrated into other native religions (Zürcher 1980 ). For example, the top 1 work shown in Fig. 8e is the native religious classic named Xuan Zhu Lu , which deeply absorbed Buddhist theories. In terms of missionary targets, the preaching of Buddhism was not limited to ordinary people and even reached the supreme ruler, such as the Emperor Wu of Liang (464–549), which ranks third in Fig. 8e . With the advocacy of the emperor, the Liang Dynasty was the heyday of Buddhism in the Southern Dynasty (Strange 2011 ). For details, Fig. 8f shows three similar cases from the top three native classics after the introduction of Buddhism. Religious concepts from Buddhism were mixed into Chinese as new words (e.g., ten directions, immeasurable and Buddha). India’s “Ganges River” flowed into ancient China along with Buddhist scriptures.

Online platform

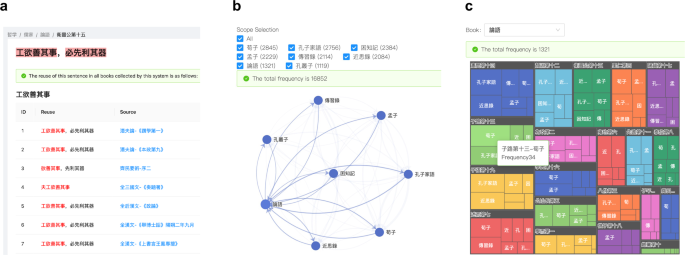

In this paper, we focused on the theme of cultural evolution. However, there are many other meaningful findings in our modelling results, which await further explanation by relevant scholars. Therefore, we have developed an online platform ( http://evolution.pkudh.xyz/ ) featuring an interactive visualization system that displays the corpus and intertextual sentences. This platform shows millions of intertextual cases detected in this work and provides support for further data analysis. Even researchers without programming backgrounds can gain valuable insights into our work and develop further studies using this convenient tool. We gave several screenshots of the platform in Fig. 9 .

a Intertextual sentence browsing from corpus. b Intertextual sentence statistics and visualization within a custom collection. c Visualization of intertextual sentences distribution among different chapters of a book within a custom collection.

With the leap forward of big data and AI technology, computer-assisted cultural studies have expanded in both scale and depth. Intricate cultural problems can be discussed quantitatively with the support of large-scale data. In this paper, we used digital methods to quantify the cultural evolution of China over the past thousands of years within a large-scale corpus of ancient literature.

We gave validated results for several acknowledged cultural phenomena. The two evolutionary paths of Taoism and Confucianism, inspiring new branches of school and migrating to religious fields, were confirmed by intertextual associations. Besides, we provided quantitative evidence for the connections between the schools’ status and several historical events. It shows the intertwining of philosophical schools and politics in ancient China.

Through our analysis, we gained quantitative insights into some long-debated cultural problems. For literature with controversial school attribution, our findings suggest that Lüshi Chunqiu is a syncretic work headed by the theory of Taoism. As for literature with controversial authorship attribution, we revealed that Five Sets of Filial Piety Biographies and Book of Ministers are divergent from other works of Tao Yuanming in ideological preference. In the comparison between Confucianism and Taoism, we propose that collectivism represented by Confucianism was mainstream in the political domain, while individualism represented by Taoism was active in extensive fields of ancient Chinese culture.

Furthermore, we investigated intercultural communication between Buddhism and Chinese native culture. The results suggest that the influence of this foreign culture evolved at different stages, from imitation to integration. In the early days, Buddhism imitated similar aspects of native culture to ease resistance (Kohn 1995 ). After the initial prosperity of Buddhism in China, it was remoulded through localized Buddhist works. As time went by, Buddhism became a part of the local culture. It was evident in various cultural domains of ancient China.

Our study demonstrates that hierarchical intertextuality modelling is a promising tool for cultural analysis within the large-scale corpus. However, there are still limitations in quantitative intertextuality research on Chinese literature. The evolution of language over time presents challenges in detecting intertextuality between ancient Chinese and modern Chinese is challenging. Besides, intercultural communication from different languages requires cross-lingual detection, which is still an area that remains underexplored.

This research represents an innovative attempt to study the evolution of Chinese culture from a digital perspective. It provides new insights into the interpretation of ancient Chinese culture and raises important questions for further exploration: How did ancient Chinese culture evolve into its modern form? What was the impact of global culture on this process of evolution? To conduct more comprehensive research, interdisciplinary and intercultural collaboration is necessary.

Data availability

The open-sourced code, data catalogue and online platform can be found here: https://github.com/CissyDuan/Evol . The textual data can be downloaded from open websites: http://www.xueheng.net and http://www.daizhige.org/ . The pre-trained model is accessed from an open-sourced model: https://github.com/ethan-yt/guwenbert .

Alfaro MJM (1996) Intertextuality: origins and development of the concept. Atlantis 18:268–285. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41054827

Google Scholar

Alshaabi T, Adams JL, Arnold MV et al. (2021) Storywrangler: a massive exploratorium for sociolinguistic, cultural, socioeconomic, and political timelines using Twitter. Sci Adv 7(29):eabe6534. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abe6534

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Assael Y, Sommerschield T, Shillingford B et al. (2022) Restoring and attributing ancient texts using deep neural networks. Nature 603(7900):280–283. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04448-z

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ban G (1962) Book of Han. Zhonghua Book Company, Beijing

Bol PK (2008) Neo-Confucianism in history. Harvard University Asia Center, Cambridge, MA

Burns PJ, Brofos JA, Li K, et al. (2021) Profiling of intertextuality in Latin literature using word embeddings. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (pp. 4900–4907). https://aclanthology.org/2021.naacl-main.389

Büchler M, Burns PR, Müller M, et al. (2014) Towards a historical text re-use detection. In Text Mining (pp. 221–238). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12655-5_11

Chen KKS (1964) Buddhism in China: a historical survey. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv131bw1p

Chen S (1989) Han Shi Waizhuan Shu Zheng. Shin Wen Feng Print Co., Taipei

Chen H (2001) Survey of research on lüshi chunqiu. J Chin Cult 2:64–72

ADS Google Scholar

Chen T, Kornblith S, Norouzi M, et al. (2020) A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations. In International conference on machine learning (pp. 1597–1607). PMLR. http://proceedings.mlr.press/v119/chen20j.html

Coffee N, Koenig JP, Poornima S et al. (2012a) The Tesserae Project: intertextual analysis of Latin poetry. Literary and linguistic computing 28(2):221–228. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqs033

Article Google Scholar

Coffee N, Koenig JP, Poornima S et al. (2012b) Intertextuality in the digital age. Transactions of the American Philological Association 1974:383–422. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23324457

Deng Z, Yang H, Wang J (2022) A Comparative Study of Shiji and Hanshu from the Perspective of Digital Humanities. In Proceedings of the 21st Chinese National Conference on Computational Linguistics (pp. 656–670). https://aclanthology.org/2022.ccl-1.59

Devlin J, Chang M-W, Lee K et al. (2019) BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of NAACL-HLT (pp 4171–4186). https://aclanthology.org/N19-1423

Dexter JP, Katz T, Tripuraneni N et al. (2017) Quantitative criticism of literary relationships. Proc Natl Acad Sci 114(16):E3195–E3204. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1611910114

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Feng Y, Bodde D (1948) A Short History of Chinese Philosophy. Macmillan Inc., New York

Forstall CW, Jacobson SL, Scheirer WJ (2011) Evidence of intertextuality: investigating Paul the Deacon’s Angustae Vitae. Lit Linguist Comput 26(3):285–296. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqr029

Forstall C, Coffee N, Buck T et al. (2015) Modeling the scholars: detecting intertextuality through enhanced word-level n-gram matching. Digit Scholarsh Humanit 30(4):503–515. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqu014

Ganascia J-G, Glaudes P, Del Lungo A (2014) Automatic detection of reuses and citations in literary texts. Lit Linguist Comput 29(3):412–421. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqu020

Gao T, Yao X, Chen D (2021) SimCSE: simple contrastive learning of sentence embeddings. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (pp. 6894–6910). https://aclanthology.org/2021.emnlp-main.552

Garg N, Schiebinger L, Jurafsky D et al. (2018) Word embeddings quantify 100 years of gender and ethnic stereotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci 115(16):E3635–E3644. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1720347115

Gernet J (1996) A history of Chinese civilization. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Giulianelli M, Del Tredici M, Fernández R (2020) Analysing lexical semantic change with contextualised word representations. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (pp 3960–3973). https://aclanthology.org/2020.acl-main.365

Graham AC (1989) Disputers of the Tao: Philosophical argument in ancient China. Open Court, Chicago

Gray RD, Watts J (2017) Cultural macroevolution matters. Proc Natl Acad Sci 114(30):7846–7852. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1620746114

Hartberg YM, Wilson DS (2017) Sacred text as cultural genome: an inheritance mechanism and method for studying cultural evolution. Religion Brain Behav 7(3):178–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/2153599X.2016.1195766

He Z, Zhu G, Fan S (2004) Parallel Passages from Pre-Han and Han Texts Series. The Chinese University Press, Hong Kong

Huang S, Zhou H, Peng Q et al. (2021) Automatic recognition and bibliometric analysis of cited books. J China Soc Sci Tech Inform 40(12):1325–1337. https://doi.org/10.3772/j.issn.1000-0135.2021.12.010

Ji Y (1997) Qin Ding Siku Quanshu Zongmu, Zhonghua Book Company, Beijing

Jockers ML (2013) Macroanalysis: Digital methods and literary history. University of Illinois Press, Urbana

Johnson J, Douze M, Jegou H (2019) Billion-scale similarity search with gpus. IEEE Trans Big Data 7(3):535–547. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBDATA.2019.2921572

Juergensmeyer M (2005) Religion in Global Civil Society. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Kingma DP, Ba J (2015) Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1412.6980

Kohn L (1995) Laughing at the Tao: Debates among Buddhists and Taoists in Medieval China. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Kozlowski AC, Taddy M, Evans JA (2019) The geometry of culture: analyzing the meanings of class through word embeddings. Am Sociol Rev 84(5):905–949. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419877135

Kristeva J (1980) Word, dialogue, and novel. In Leon S. Roudiez, editor, Desire in Language: A Semiotic Approach to Literature and Art, pp. 64–91. Columbia University Press, New York

Lansdall-Welfare T, Sudhahar S, Thompson J et al. (2017) Content analysis of 150 years of British periodicals. Proc Natl Acad Sci 114(4):E457–E465. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1606380114

Lee JS (2007) A computational model of text reuse in ancient literary texts. In Proceedings of the 45th Annual Meeting of the Association of Computational Linguistics (pp 472–479). https://aclanthology.org/P07-1060

Lee J, Kong YH, Luo M (2018) Syntactic patterns in classical Chinese poems: a quantitative study. Digit Scholarsh Humanit 33(1):82–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqw059

Legge J (1861) Confucian analects: the great learning, and the doctrine of the mean. Courier Corporation. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/4094

Lewens T (2015) Cultural evolution: conceptual challenges. OUP, Oxford

Book Google Scholar

Li W, Shao Y, Bi M (2022) Data construction and matching method for the task of ancient classics reference detection. In Proceedings of the 21st Chinese National Conference on Computational Linguistics (pp 600–610). https://aclanthology.org/2022.ccl-1.54

Liang Y, Wang D, Huang S (2021) Research on automatic mining of variants expressing the same event in the ancient books. Library Inform Service 65(09):97–104. https://doi.org/10.13266/j.issn.0252-3116.2021.09.011

Liu Y, Ott M, Goyal N et al. (2019) Roberta: A robustly optimized bert pretraining approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.11692. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1907.11692

Mesoudi A (2017) Pursuing Darwin’s curious parallel: prospects for a science of cultural evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci 114(30):7853–7860. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1620741114

Michel JB, Shen YK, Aiden AP et al. (2011) Quantitative analysis of culture using millions of digitized books. Science 331(6014):176–182. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1199644

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Mollier C (2008) Buddhism and Taoism face to face. In Buddhism and Taoism Face to Face. University of Hawaii Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780824861698

Moritz M, Wiederhold A, Pavlek B et al. (2016) Non-literal text reuse in historical texts: an approach to identify reuse transformations and its application to bible reuse. In Proceedings of the 2016 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing pp 1849–1859. https://aclanthology.org/D16-1190

Munro DJ (1985) Individualism and holism: Studies in Confucian and Taoist values. Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

Neidorf L, Krieger MS, Yakubek M et al. (2019) Large-scale quantitative profiling of the Old English verse tradition. Nat Hum Behav 3(6):560–567. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-019-0570-1

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Newberry MG, Plotkin JB (2022) Measuring frequency-dependent selection in culture. Nat Hum Behav, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01342-6

Newberry MG, Ahern CA, Clark R et al. (2017) Detecting evolutionary forces in language change. Nature 551(7679):223–226. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature24455

Nichols R, Slingerland E, Nielbo K et al. (2018) Modeling the contested relationship between Analects, Mencius, and Xunzi: Preliminary evidence from a machine-learning approach. J Asian Stud 77(1):19–57. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021911817000973

Raz G (2012) The Emergence of Daoism: Creation of Tradition. Routledge, Milton Park

Resler A, Yeshurun R, Natalio F et al. (2021) A deep-learning model for predictive archaeology and archaeological community detection. Humanit Social Sci Commun 8(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00970-z

Riffaterre M (1994) Intertextuality vs. hypertextuality. New Literary History 25(4):779–788. https://doi.org/10.2307/469373

Rockmore DN, Fang C, Foti NJ et al. (2018) The cultural evolution of national constitutions. J Assoc Inform Sci Technol 69(3):483–494. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23971

Romanello M (2016) Exploring citation networks to study intertextuality in classics. DHQ: Digital Humanities Quarterly, 10(2). http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/10/2/000255/000255.html

Scheirer W, Forstall C, Coffee N (2016) The sense of a connection: automatic tracing of intertextuality by meaning. Digit Scholarsh Humanit 31(1):204–217. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqu058

Schwartz BI (1985) The world of thought in ancient China. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Sima Q (1959) Records of the Grand Historian, Zhonghua Book Company, Beijing

Strange M (2011) Representations of Liang Emperor Wu as a Buddhist Ruler in Sixth-and Seventh-century Texts. Asia Major, THIRD SERIES, Vol. 24, No. 2 (2011), pp. 53–112. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41650011

Sturgeon D (2018a) Digital approaches to text reuse in the early Chinese corpus. J Chin Lit Culture 5(2):186–213. https://doi.org/10.1215/23290048-7256963

Sturgeon D (2018b) Unsupervised identification of text reuse in early Chinese literature. Digit Scholarsh Humanit 33(3):670–684. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqx024

Swartz W (2008) Reading Tao Yuanming. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1x07x16

Tamariz M (2019) Replication and emergence in cultural transmission. Phys Life Rev 30:47–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plrev.2019.04.004

Article ADS PubMed Google Scholar

Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N et al. (2017) Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems, 30. https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2017/file/3f5ee243547dee91fbd053c1c4a845aa-Paper.pdf

Yang Y, Song Y (2022) Exploring the similarity between Han’s and non-Han’s Yuan poetry: resistance distance metrics over character co-occurrence networks. Digit Scholarsh Humanit 37(3):880–893. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqab082

Yao X (2000) An introduction to Confucianism. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511800887

Yu K, Shao Y, Li W (2022) Research on Sentence Alignment of Ancient and Modern Chinese based on Reinforcement Learning). In Proceedings of the 21st Chinese National Conference on Computational Linguistics (pp. 704–715). https://aclanthology.org/2022.ccl-1.63

Zhao D (2015) The Confucian-legalist state: a new theory of Chinese history. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199351732.001.0001

Zhou H (2011) Confucianism and the Legalism: a model of the national strategy of governance in ancient China. Front Econ China 6(4):616–637. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11459-011-0150-4

Zhou H, Jiang Y, Wang L (2023) Are Daojing and Dejing stylistically independent of each other: a stylometric analysis with activity and descriptivity. Digit Scholarsh Humanit 38(1):434–450. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqac042

Zhu H, Lei L, Craig H (2021) Prose, verse and authorship in dream of the red chamber: a stylometric analysis. J Quant Linguist 28(4):289–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/09296174.2020.1724677

Zürcher E (1980) Buddhist influence on early Taoism. T’oung Pao 66(1):84–147. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853280X00039

Zürcher E (2007) The Buddhist conquest of China: the spread and adaptation of Buddhism in early medieval China. Brill, Leiden

Download references

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the NSFC project ‘the Construction of the Knowledge Graph for the History of Chinese Confucianism’ (Grant No. 72010107003).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Information Management, Peking University, Beijing, China

Siyu Duan & Jun Wang

Center for Digital Humanities, Peking University, Beijing, China

Siyu Duan, Jun Wang, Hao Yang & Qi Su

Institute for Artificial Intelligence, Peking University, Beijing, China

Jun Wang, Hao Yang & Qi Su

School of Foreign Languages, Peking University, Beijing, China

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

SD wrote code and paper, conducted experiments and data analysis, and designed the online platform. JW initiated this research, proposed research questions and technical paths, and revised the paper. HY collected and processed the data and revised the paper from a humanities perspective. QS directed this work, including technical innovation, cultural analysis and paper writing. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Qi Su .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Additional information.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Duan, S., Wang, J., Yang, H. et al. Disentangling the cultural evolution of ancient China: a digital humanities perspective. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10 , 310 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01811-x

Download citation

Received : 08 December 2022

Accepted : 30 May 2023

Published : 09 June 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01811-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Original article

- Open access

- Published: 28 April 2022

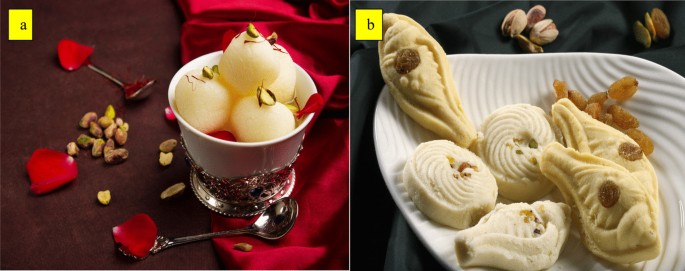

Evolution of Indian cuisine: a socio-historical review

- Vishu Antani 1 , 2 &

- Santosh Mahapatra ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0077-2882 3

Journal of Ethnic Foods volume 9 , Article number: 15 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

42k Accesses

2 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details