- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research Research Tools and Apps

Study Population: Characteristics & Sampling Techniques

How do you define a study population? Research studies require specific groups to draw conclusions and make decisions based on their results. This group of interest is known as a sample. The method used to select respondents is known as sampling.

What is a Study Population?

A study population is a group considered for a study or statistical reasoning. The study population is not limited to the human population only. It is a set of aspects that have something in common. They can be objects, animals, measurements, etc., with many characteristics within a group.

For example, suppose you are interested in the average time a person between the ages of 30 and 35 takes to recover from a particular condition after consuming a specific type of medication. In that case, the study population will be all people between the ages of 30 and 35.

A medical study examines the spread of a specific disease in stray dogs in a city. Here, the stray dogs belonging to that city are the study population. This population or sample represents the entire population you want to conclude about.

How to establish a study population?

Sampling is a powerful technique for collecting opinions from a wide range of people, chosen from a particular group, to learn more about the whole group in general.

For any research study to be effective, it is necessary to select the study population that truly represents the entire population. Before starting your study, the target population must be identified and agreed upon. By appointing and knowing your sample well in advance, any feedback deemed useless to the study will be largely eliminated.

If your survey aims to understand a product’s or service’s effectiveness, then the study population should be the customers who have used it or are best suited to their needs and who will use the product/service.

It would be costly and time-consuming to collect data from the entire population of your target market. By accurately sampling your study population, it is possible to build a true picture of the target market using the trends in the results.

LEARN ABOUT: Survey Sampling

Choosing an accurate sample from the study population

The decision on an appropriate sample depends on several key factors.

- First, you decide which population parameters you want to estimate.

- Don’t expect estimates from a sample to be exact. Always expect a margin of error when making assumptions based on the results of a sample.

- Understanding the cost of sampling helps us determine how precise our estimates need to be.

- Know how variable the population you want to measure is. It is not necessary to assume that a large sample is required if the study population is large.

- Take into account the response rate of your population. A 20% response rate is considered “good” for an online research study.

Sampling characteristics in the study population

- Sampling is a mechanism to collect data without surveying the entire target population.

- The study population is the entire unit of people you consider for your research. A sample is a subset of this group that represents the population.

- Sampling reduces survey fatigue as it is used to prevent pollsters from conducting too many surveys, thereby increasing response rates.

- Also, it is much cheaper and saves more time than measuring the entire group.

- Tracking the response rate patterns of different groups will help determine how many respondents to select.

- The study is not only limited to the selected part, but is applied to the entire target population.

Sampling techniques for your study population

Now that you understand that you cannot survey the entire study population due to various factors, you should adopt one of the sample selection methodologies that best suits your research study.

In general terms, two methodologies can be applied: probability sampling and non-probability sampling .

Sampling Techniques: Probability Sampling

This method is used to select sample objects from a population based on probability theory. Everyone is included in the sample and has an equal chance of being selected. There is no bias in this type of sample. Every person in the population has the opportunity to be part of the research.

Probability sampling can be categorized into four types:

- Simple Random Sampling : Simple random sampling is the easiest way to select a sample. Here, each member has an equal chance of being part of the sample. The objects in this sample are chosen at random, and each member has exactly the same probability of being selected.

- Cluster sampling : Cluster sampling is a method in which respondents are grouped into clusters. These groups can be defined based on age, gender, location, and demographic parameters.

- Systematic Sampling : In systematic sampling, individuals are chosen at equal intervals from the population. A starting point is selected, and then respondents are chosen at predefined sample intervals.

- Stratified Sampling: S tratified random sampling is a process of dividing respondents into distinct but predefined parameters. In this method, respondents do not overlap but collectively represent the entire population.

Sampling techniques: Non-probabilistic sampling

The non-probability sampling method uses the researcher’s preference regarding sample selection bias . This sampling method derives primarily from the researcher’s ability to access this sample. Here the population members do not have the same opportunities to be part of the sample.

Non-probability sampling can be further classified into four distinct types:

- Convenience Sampling: As the name implies, convenience sampling represents the convenience with which the researcher can reach the respondent. The researchers do not have the authority to select the samples and they are done solely for reasons of proximity and not representativeness.

- Deliberate, critical, or judgmental sampling: In this type of sampling the researcher judges and develops his sample on the nature of the study and the understanding of his target audience. Only people who meet the research criteria and the final objective are selected.

- Snowball Sampling: As a snowball speeds up, it accumulates more snow around itself. Similarly, with snowball sampling, respondents are tasked with providing references or recruiting samples for the study once their participation ends.

- Quota Sampling: Quota sampling is a method where the researcher has the privilege to select a sample based on its strata. In this method, two people cannot exist under two different conditions.

LEARN ABOUT: Theoretical Research

Advantages and disadvantages of sampling in a study population

In most cases, of the total study population, perceptions can only be obtained from predefined samples. This comes with its own advantages and disadvantages. Some of them are listed below.

- Highly accurate – low probability of sampling errors (if sampled well)

- Economically feasible by nature, highly reliable

- High fitness ratio to different surveys Takes less time compared to surveying the entire population Reduced resource deployment

- Data-intensive and comprehensive Properties are applied to a larger population wideIdeal when the study population is vast.

Disadvantages

- Insufficient samples

- Possibility of bias

- Precision problems (if sampling is poor)

- Difficulty obtaining the typical sample

- Lack of quality sources

- Possibility of making mistakes.

At QuestionPro we can help you carry out your study with your study population. Learn about all the features of our online survey software and start conducting your research today!

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

The Best Email Survey Tool to Boost Your Feedback Game

May 7, 2024

Top 10 Employee Engagement Survey Tools

Top 20 Employee Engagement Software Solutions

May 3, 2024

15 Best Customer Experience Software of 2024

May 2, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

- Foundations

- Write Paper

Search form

- Experiments

- Anthropology

- Self-Esteem

- Social Anxiety

Research Population

All research questions address issues that are of great relevance to important groups of individuals known as a research population.

This article is a part of the guide:

- Non-Probability Sampling

- Convenience Sampling

- Random Sampling

- Stratified Sampling

- Systematic Sampling

Browse Full Outline

- 1 What is Sampling?

- 2.1 Sample Group

- 2.2 Research Population

- 2.3 Sample Size

- 2.4 Randomization

- 3.1 Statistical Sampling

- 3.2 Sampling Distribution

- 3.3.1 Random Sampling Error

- 4.1 Random Sampling

- 4.2 Stratified Sampling

- 4.3 Systematic Sampling

- 4.4 Cluster Sampling

- 4.5 Disproportional Sampling

- 5.1 Convenience Sampling

- 5.2 Sequential Sampling

- 5.3 Quota Sampling

- 5.4 Judgmental Sampling

- 5.5 Snowball Sampling

A research population is generally a large collection of individuals or objects that is the main focus of a scientific query. It is for the benefit of the population that researches are done. However, due to the large sizes of populations, researchers often cannot test every individual in the population because it is too expensive and time-consuming. This is the reason why researchers rely on sampling techniques .

A research population is also known as a well-defined collection of individuals or objects known to have similar characteristics. All individuals or objects within a certain population usually have a common, binding characteristic or trait.

Usually, the description of the population and the common binding characteristic of its members are the same. "Government officials" is a well-defined group of individuals which can be considered as a population and all the members of this population are indeed officials of the government.

Relationship of Sample and Population in Research

A sample is simply a subset of the population. The concept of sample arises from the inability of the researchers to test all the individuals in a given population. The sample must be representative of the population from which it was drawn and it must have good size to warrant statistical analysis.

The main function of the sample is to allow the researchers to conduct the study to individuals from the population so that the results of their study can be used to derive conclusions that will apply to the entire population. It is much like a give-and-take process. The population “gives” the sample, and then it “takes” conclusions from the results obtained from the sample.

Two Types of Population in Research

Target population.

Target population refers to the ENTIRE group of individuals or objects to which researchers are interested in generalizing the conclusions. The target population usually has varying characteristics and it is also known as the theoretical population.

Accessible Population

The accessible population is the population in research to which the researchers can apply their conclusions. This population is a subset of the target population and is also known as the study population. It is from the accessible population that researchers draw their samples.

- Psychology 101

- Flags and Countries

- Capitals and Countries

Explorable.com (Nov 15, 2009). Research Population. Retrieved May 11, 2024 from Explorable.com: https://explorable.com/research-population

You Are Allowed To Copy The Text

The text in this article is licensed under the Creative Commons-License Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) .

This means you're free to copy, share and adapt any parts (or all) of the text in the article, as long as you give appropriate credit and provide a link/reference to this page.

That is it. You don't need our permission to copy the article; just include a link/reference back to this page. You can use it freely (with some kind of link), and we're also okay with people reprinting in publications like books, blogs, newsletters, course-material, papers, wikipedia and presentations (with clear attribution).

Want to stay up to date? Follow us!

Save this course for later.

Don't have time for it all now? No problem, save it as a course and come back to it later.

Footer bottom

- Privacy Policy

- Subscribe to our RSS Feed

- Like us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

Introduction to Research Methods

7 samples and populations.

So you’ve developed your research question, figured out how you’re going to measure whatever you want to study, and have your survey or interviews ready to go. Now all your need is other people to become your data.

You might say ‘easy!’, there’s people all around you. You have a big family tree and surely them and their friends would have happy to take your survey. And then there’s your friends and people you’re in class with. Finding people is way easier than writing the interview questions or developing the survey. That reaction might be a strawman, maybe you’ve come to the conclusion none of this is easy. For your data to be valuable, you not only have to ask the right questions, you have to ask the right people. The “right people” aren’t the best or the smartest people, the right people are driven by what your study is trying to answer and the method you’re using to answer it.

Remember way back in chapter 2 when we looked at this chart and discussed the differences between qualitative and quantitative data.

One of the biggest differences between quantitative and qualitative data was whether we wanted to be able to explain something for a lot of people (what percentage of residents in Oklahoma support legalizing marijuana?) versus explaining the reasons for those opinions (why do some people support legalizing marijuana and others not?). The underlying differences there is whether our goal is explain something about everyone, or whether we’re content to explain it about just our respondents.

‘Everyone’ is called the population . The population in research is whatever group the research is trying to answer questions about. The population could be everyone on planet Earth, everyone in the United States, everyone in rural counties of Iowa, everyone at your university, and on and on. It is simply everyone within the unit you are intending to study.

In order to study the population, we typically take a sample or a subset. A sample is simply a smaller number of people from the population that are studied, which we can use to then understand the characteristics of the population based on that subset. That’s why a poll of 1300 likely voters can be used to guess at who will win your states Governor race. It isn’t perfect, and we’ll talk about the math behind all of it in a later chapter, but for now we’ll just focus on the different types of samples you might use to study a population with a survey.

If correctly sampled, we can use the sample to generalize information we get to the population. Generalizability , which we defined earlier, means we can assume the responses of people to our study match the responses everyone would have given us. We can only do that if the sample is representative of the population, meaning that they are alike on important characteristics such as race, gender, age, education. If something makes a large difference in people’s views on a topic in your research and your sample is not balanced, you’ll get inaccurate results.

Generalizability is more of a concern with surveys than with interviews. The goal of a survey is to explain something about people beyond the sample you get responses from. You’ll never see a news headline saying that “53% of 1250 Americans that responded to a poll approve of the President”. It’s only worth asking those 1250 people if we can assume the rest of the United States feels the same way overall. With interviews though we’re looking for depth from their responses, and so we are less hopefully that the 15 people we talk to will exactly match the American population. That doesn’t mean the data we collect from interviews doesn’t have value, it just has different uses.

There are two broad types of samples, with several different techniques clustered below those. Probability sampling is associated with surveys, and non-probability sampling is often used when conducting interviews. We’ll first describe probability samples, before discussing the non-probability options.

The type of sampling you’ll use will be based on the type of research you’re intending to do. There’s no sample that’s right or wrong, they can just be more or less appropriate for the question you’re trying to answer. And if you use a less appropriate sampling strategy, the answer you get through your research is less likely to be accurate.

7.1 Types of Probability Samples

So we just hinted at the idea that depending on the sample you use, you can generalize the data you collect from the sample to the population. That will depend though on whether your sample represents the population. To ensure that your sample is representative of the population, you will want to use a probability sample. A representative sample refers to whether the characteristics (race, age, income, education, etc) of the sample are the same as the population. Probability sampling is a sampling technique in which every individual in the population has an equal chance of being selected as a subject for the research.

There are several different types of probability samples you can use, depending on the resources you have available.

Let’s start with a simple random sample . In order to use a simple random sample all you have to do is take everyone in your population, throw them in a hat (not literally, you can just throw their names in a hat), and choose the number of names you want to use for your sample. By drawing blindly, you can eliminate human bias in constructing the sample and your sample should represent the population from which it is being taken.

However, a simple random sample isn’t quite that easy to build. The biggest issue is that you have to know who everyone is in order to randomly select them. What that requires is a sampling frame , a list of all residents in the population. But we don’t always have that. There is no list of residents of New York City (or any other city). Organizations that do have such a list wont just give it away. Try to ask your university for a list and contact information of everyone at your school so you can do a survey? They wont give it to you, for privacy reasons. It’s actually harder to think of popultions you could easily develop a sample frame for than those you can’t. If you can get or build a sampling frame, the work of a simple random sample is fairly simple, but that’s the biggest challenge.

Most of the time a true sampling frame is impossible to acquire, so researcher have to settle for something approximating a complete list. Earlier generations of researchers could use the random dial method to contact a random sample of Americans, because every household had a single phone. To use it you just pick up the phone and dial random numbers. Assuming the numbers are actually random, anyone might be called. That method actually worked somewhat well, until people stopped having home phone numbers and eventually stopped answering the phone. It’s a fun mental exercise to think about how you would go about creating a sampling frame for different groups though; think through where you would look to find a list of everyone in these groups:

Plumbers Recent first-time fathers Members of gyms

The best way to get an actual sampling frame is likely to purchase one from a private company that buys data on people from all the different websites we use.

Let’s say you do have a sampling frame though. For instance, you might be hired to do a survey of members of the Republican Party in the state of Utah to understand their political priorities this year, and the organization could give you a list of their members because they’ve hired you to do the reserach. One method of constructing a simple random sample would be to assign each name on the list a number, and then produce a list of random numbers. Once you’ve matched the random numbers to the list, you’ve got your sample. See the example using the list of 20 names below

and the list of 5 random numbers.

Systematic sampling is similar to simple random sampling in that it begins with a list of the population, but instead of choosing random numbers one would select every kth name on the list. What the heck is a kth? K just refers to how far apart the names are on the list you’re selecting. So if you want to sample one-tenth of the population, you’d select every tenth name. In order to know the k for your study you need to know your sample size (say 1000) and the size of the population (75000). You can divide the size of the population by the sample (75000/1000), which will produce your k (750). As long as the list does not contain any hidden order, this sampling method is as good as the random sampling method, but its only advantage over the random sampling technique is simplicity. If we used the same list as above and wanted to survey 1/5th of the population, we’d include 4 of the names on the list. It’s important with systematic samples to randomize the starting point in the list, otherwise people with A names will be oversampled. If we started with the 3rd name, we’d select Annabelle Frye, Cristobal Padilla, Jennie Vang, and Virginia Guzman, as shown below. So in order to use a systematic sample, we need three things, the population size (denoted as N ), the sample size we want ( n ) and k , which we calculate by dividing the population by the sample).

N= 20 (Population Size) n= 4 (Sample Size) k= 5 {20/4 (kth element) selection interval}

We can also use a stratified sample , but that requires knowing more about the population than just their names. A stratified sample divides the study population into relevant subgroups, and then draws a sample from each subgroup. Stratified sampling can be used if you’re very concerned about ensuring balance in the sample or there may be a problem of underrepresentation among certain groups when responses are received. Not everyone in your sample is equally likely to answer a survey. Say for instance we’re trying to predict who will win an election in a county with three cities. In city A there are 1 million college students, in city B there are 2 million families, and in City C there are 3 million retirees. You know that retirees are more likely than busy college students or parents to respond to a poll. So you break the sample into three parts, ensuring that you get 100 responses from City A, 200 from City B, and 300 from City C, so the three cities would match the population. A stratified sample provides the researcher control over the subgroups that are included in the sample, whereas simple random sampling does not guarantee that any one type of person will be included in the final sample. A disadvantage is that it is more complex to organize and analyze the results compared to simple random sampling.

Cluster sampling is an approach that begins by sampling groups (or clusters) of population elements and then selects elements from within those groups. A researcher would use cluster sampling if getting access to elements in an entrie population is too challenging. For instance, a study on students in schools would probably benefit from randomly selecting from all students at the 36 elementary schools in a fictional city. But getting contact information for all students would be very difficult. So the researcher might work with principals at several schools and survey those students. The researcher would need to ensure that the students surveyed at the schools are similar to students throughout the entire city, and greater access and participation within each cluster may make that possible.

The image below shows how this can work, although the example is oversimplified. Say we have 12 students that are in 6 classrooms. The school is in total 1/4th green (3/12), 1/4th yellow (3/12), and half blue (6/12). By selecting the right clusters from within the school our sample can be representative of the entire school, assuming these colors are the only significant difference between the students. In the real world, you’d want to match the clusters and population based on race, gender, age, income, etc. And I should point out that this is an overly simplified example. What if 5/12s of the school was yellow and 1/12th was green, how would I get the right proportions? I couldn’t, but you’d do the best you could. You still wouldn’t want 4 yellows in the sample, you’d just try to approximiate the population characteristics as best you can.

7.2 Actually Doing a Survey

All of that probably sounds pretty complicated. Identifying your population shouldn’t be too difficult, but how would you ever get a sampling frame? And then actually identifying who to include… It’s probably a bit overwhelming and makes doing a good survey sound impossible.

Researchers using surveys aren’t superhuman though. Often times, they use a little help. Because surveys are really valuable, and because researchers rely on them pretty often, there has been substantial growth in companies that can help to get one’s survey to its intended audience.

One popular resource is Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (more commonly known as MTurk). MTurk is at its most basic a website where workers look for jobs (called hits) to be listed by employers, and choose whether to do the task or not for a set reward. MTurk has grown over the last decade to be a common source of survey participants in the social sciences, in part because hiring workers costs very little (you can get some surveys completed for penny’s). That means you can get your survey completed with a small grant ($1-2k at the low end) and get the data back in a few hours. Really, it’s a quick and easy way to run a survey.

However, the workers aren’t perfectly representative of the average American. For instance, researchers have found that MTurk respondents are younger, better educated, and earn less than the average American.

One way to get around that issue, which can be used with MTurk or any survey, is to weight the responses. Because with MTurk you’ll get fewer responses from older, less educated, and richer Americans, those responses you do give you want to count for more to make your sample more representative of the population. Oversimplified example incoming!

Imagine you’re setting up a pizza party for your class. There are 9 people in your class, 4 men and 5 women. You only got 4 responses from the men, and 3 from the women. All 4 men wanted peperoni pizza, while the 3 women want a combination. Pepperoni wins right, 4 to 3? Not if you assume that the people that didn’t respond are the same as the ones that did. If you weight the responses to match the population (the full class of 9), a combination pizza is the winner.

Because you know the population of women is 5, you can weight the 3 responses from women by 5/3 = 1.6667. If we weight (or multiply) each vote we did receive from a woman by 1.6667, each vote for a combination now equals 1.6667, meaning that the 3 votes for combination total 5. Because we received a vote from every man in the class, we just weight their votes by 1. The big assumption we have to make is that the people we didn’t hear from (the 2 women that didn’t vote) are similar to the ones we did hear from. And if we don’t get any responses from a group we don’t have anything to infer their preferences or views from.

Let’s go through a slightly more complex example, still just considering one quality about people in the class. Let’s say your class actually has 100 students, but you only received votes from 50. And, what type of pizza people voted for is mixed, but men still prefer peperoni overall, and women still prefer combination. The class is 60% female and 40% male.

We received 21 votes from women out of the 60, so we can weight their responses by 60/21 to represent the population. We got 29 votes out of the 40 for men, so their responses can be weighted by 40/29. See the math below.

53.8 votes for combination? That might seem a little odd, but weighting isn’t a perfect science. We can’t identify what a non-respondent would have said exactly, all we can do is use the responses of other similar people to make a good guess. That issue often comes up in polling, where pollsters have to guess who is going to vote in a given election in order to project who will win. And we can weight on any characteristic of a person we think will be important, alone or in combination. Modern polls weight on age, gender, voting habits, education, and more to make the results as generalizable as possible.

There’s an appendix later in this book where I walk through the actual steps of creating weights for a sample in R, if anyone actually does a survey. I intended this section to show that doing a good survey might be simpler than it seemed, but now it might sound even more difficult. A good lesson to take though is that there’s always another door to go through, another hurdle to improve your methods. Being good at research just means being constantly prepared to be given a new challenge, and being able to find another solution.

7.3 Non-Probability Sampling

Qualitative researchers’ main objective is to gain an in-depth understanding on the subject matter they are studying, rather than attempting to generalize results to the population. As such, non-probability sampling is more common because of the researchers desire to gain information not from random elements of the population, but rather from specific individuals.

Random selection is not used in nonprobability sampling. Instead, the personal judgment of the researcher determines who will be included in the sample. Typically, researchers may base their selection on availability, quotas, or other criteria. However, not all members of the population are given an equal chance to be included in the sample. This nonrandom approach results in not knowing whether the sample represents the entire population. Consequently, researchers are not able to make valid generalizations about the population.

As with probability sampling, there are several types of non-probability samples. Convenience sampling , also known as accidental or opportunity sampling, is a process of choosing a sample that is easily accessible and readily available to the researcher. Researchers tend to collect samples from convenient locations such as their place of employment, a location, school, or other close affiliation. Although this technique allows for quick and easy access to available participants, a large part of the population is excluded from the sample.

For example, researchers (particularly in psychology) often rely on research subjects that are at their universities. That is highly convenient, students are cheap to hire and readily available on campuses. However, it means the results of the study may have limited ability to predict motivations or behaviors of people that aren’t included in the sample, i.e., people outside the age of 18-22 that are going to college.

If I ask you to get find out whether people approve of the mayor or not, and tell you I want 500 people’s opinions, should you go stand in front of the local grocery store? That would be convinient, and the people coming will be random, right? Not really. If you stand outside a rural Piggly Wiggly or an urban Whole Foods, do you think you’ll see the same people? Probably not, people’s chracteristics make the more or less likely to be in those locations. This technique runs the high risk of over- or under-representation, biased results, as well as an inability to make generalizations about the larger population. As the name implies though, it is convenient.

Purposive sampling , also known as judgmental or selective sampling, refers to a method in which the researcher decides who will be selected for the sample based on who or what is relevant to the study’s purpose. The researcher must first identify a specific characteristic of the population that can best help answer the research question. Then, they can deliberately select a sample that meets that particular criterion. Typically, the sample is small with very specific experiences and perspectives. For instance, if I wanted to understand the experiences of prominent foreign-born politicians in the United States, I would purposefully build a sample of… prominent foreign-born politicians in the United States. That would exclude anyone that was born in the United States or and that wasn’t a politician, and I’d have to define what I meant by prominent. Purposive sampling is susceptible to errors in judgment by the researcher and selection bias due to a lack of random sampling, but when attempting to research small communities it can be effective.

When dealing with small and difficult to reach communities researchers sometimes use snowball samples , also known as chain referral sampling. Snowball sampling is a process in which the researcher selects an initial participant for the sample, then asks that participant to recruit or refer additional participants who have similar traits as them. The cycle continues until the needed sample size is obtained.

This technique is used when the study calls for participants who are hard to find because of a unique or rare quality or when a participant does not want to be found because they are part of a stigmatized group or behavior. Examples may include people with rare diseases, sex workers, or a child sex offenders. It would be impossible to find an accurate list of sex workers anywhere, and surveying the general population about whether that is their job will produce false responses as people will be unwilling to identify themselves. As such, a common method is to gain the trust of one individual within the community, who can then introduce you to others. It is important that the researcher builds rapport and gains trust so that participants can be comfortable contributing to the study, but that must also be balanced by mainting objectivity in the research.

Snowball sampling is a useful method for locating hard to reach populations but cannot guarantee a representative sample because each contact will be based upon your last. For instance, let’s say you’re studying illegal fight clubs in your state. Some fight clubs allow weapons in the fights, while others completely ban them; those two types of clubs never interreact because of their disagreement about whether weapons should be allowed, and there’s no overlap between them (no members in both type of club). If your initial contact is with a club that uses weapons, all of your subsequent contacts will be within that community and so you’ll never understand the differences. If you didn’t know there were two types of clubs when you started, you’ll never even know you’re only researching half of the community. As such, snowball sampling can be a necessary technique when there are no other options, but it does have limitations.

Quota Sampling is a process in which the researcher must first divide a population into mutually exclusive subgroups, similar to stratified sampling. Depending on what is relevant to the study, subgroups can be based on a known characteristic such as age, race, gender, etc. Secondly, the researcher must select a sample from each subgroup to fit their predefined quotas. Quota sampling is used for the same reason as stratified sampling, to ensure that your sample has representation of certain groups. For instance, let’s say that you’re studying sexual harassment in the workplace, and men are much more willing to discuss their experiences than women. You might choose to decide that half of your final sample will be women, and stop requesting interviews with men once you fill your quota. The core difference is that while stratified sampling chooses randomly from within the different groups, quota sampling does not. A quota sample can either be proportional or non-proportional . Proportional quota sampling refers to ensuring that the quotas in the sample match the population (if 35% of the company is female, 35% of the sample should be female). Non-proportional sampling allows you to select your own quota sizes. If you think the experiences of females with sexual harassment are more important to your research, you can include whatever percentage of females you desire.

7.4 Dangers in sampling

Now that we’ve described all the different ways that one could create a sample, we can talk more about the pitfalls of sampling. Ensuring a quality sample means asking yourself some basic questions:

- Who is in the sample?

- How were they sampled?

- Why were they sampled?

A meal is often only as good as the ingredients you use, and your data will only be as good as the sample. If you collect data from the wrong people, you’ll get the wrong answer. You’ll still get an answer, it’ll just be inaccurate. And I want to reemphasize here wrong people just refers to inappropriate for your study. If I want to study bullying in middle schools, but I only talk to people that live in a retirement home, how accurate or relevant will the information I gather be? Sure, they might have grandchildren in middle school, and they may remember their experiences. But wouldn’t my information be more relevant if I talked to students in middle school, or perhaps a mix of teachers, parents, and students? I’ll get an answer from retirees, but it wont be the one I need. The sample has to be appropriate to the research question.

Is a bigger sample always better? Not necessarily. A larger sample can be useful, but a more representative one of the population is better. That was made painfully clear when the magazine Literary Digest ran a poll to predict who would win the 1936 presidential election between Alf Landon and incumbent Franklin Roosevelt. Literary Digest had run the poll since 1916, and had been correct in predicting the outcome every time. It was the largest poll ever, and they received responses for 2.27 million people. They essentially received responses from 1 percent of the American population, while many modern polls use only 1000 responses for a much more populous country. What did they predict? They showed that Alf Landon would be the overwhelming winner, yet when the election was held Roosevelt won every state except Maine and Vermont. It was one of the most decisive victories in Presidential history.

So what went wrong for the Literary Digest? Their poll was large (gigantic!), but it wasn’t representative of likely voters. They polled their own readership, which tended to be more educated and wealthy on average, along with people on a list of those with registered automobiles and telephone users (both of which tended to be owned by the wealthy at that time). Thus, the poll largely ignored the majority of Americans, who ended up voting for Roosevelt. The Literary Digest poll is famous for being wrong, but led to significant improvements in the science of polling to avoid similar mistakes in the future. Researchers have learned a lot in the century since that mistake, even if polling and surveys still aren’t (and can’t be) perfect.

What kind of sampling strategy did Literary Digest use? Convenience, they relied on lists they had available, rather than try to ensure every American was included on their list. A representative poll of 2 million people will give you more accurate results than a representative poll of 2 thousand, but I’ll take the smaller more representative poll than a larger one that uses convenience sampling any day.

7.5 Summary

Picking the right type of sample is critical to getting an accurate answer to your reserach question. There are a lot of differnet options in how you can select the people to participate in your research, but typically only one that is both correct and possible depending on the research you’re doing. In the next chapter we’ll talk about a few other methods for conducting reseach, some that don’t include any sampling by you.

ISI Journals

- Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline (InformingSciJ)

- Journal of Information Technology Education: Research (JITE:Research)

- Journal of Information Technology Education: Innovations in Practice (JITE:IIP)

- Journal of Information Technology Education: Discussion Cases (JITE: DC)

- Interdisciplinary Journal of e-Skills and Lifelong Learning (IJELL)

- Interdisciplinary Journal of Information, Knowledge, and Management (IJIKM)

- International Journal of Doctoral Studies (IJDS)

- Issues in Informing Science and Information Technology (IISIT)

- Journal for the Study of Postsecondary and Tertiary Education (JSPTE)

- Informing Faculty (IF)

Collaborative Journals

- Muma Case Review (MCR)

- Muma Business Review (MBR)

- International Journal of Community Development and Management Studies (IJCDMS)

- InSITE2024 : Jul 24 - 25 2024,

- All Conferences »

- Publications

- Journals

- Conferences

Describing Populations and Samples in Doctoral Student Research

Aim/Purpose The purpose of this article is to present clear definitions of the population structures essential to research, to provide examples of how these structures are described within research, and to propose a basic structure that novice researchers may use to ensure a clearly and completely defined population of interest and sample from which they will collect data.

Background Novice researchers, especially doctoral students, experience challenges when describing and distinguishing between populations and samples. Clearly defining and describing research structural elements, to include populations and the sample, provides needed scaffolding to doctoral students.

Methodology The systematic review of 65 empirical research articles and research texts provided peer-reviewed support for presenting consistent population- and sample-related definitions and exemplars.

Contribution This article provides clear definitions of the population structures essential to research, with examples of how these structures, beginning with the unit of analysis, are described within research. With this defined, we examine the population subsets and what characterizes them. The proposed writing structure provides doctoral students a model for developing the relevant population and sample descriptions in their dissertations and other research.

Findings The article describes that although many definitions and uses are relatively consistent within the literature, there are epistemological differences between research designs that do not allow for a one-size-fits-all definition for all terms. We provide methods for defining populations and the sample, selecting a sample from the population, and the arguments for and against each of the methods.

Recommendations for Practitioners Social science research faculty seek structured ways in which to present key research elements to doctoral students and to provide a model by which they may write the dissertation. The article offers contemporary examples from the peer-reviewed literature to support these aims.

Recommendation for Researchers Novice researchers may wish to use the recommended framework within this article when developing the relevant section of the dissertation. Doing so provides an itemized checklist of writing descriptions, ensuring a more complete and comprehensive description of the study population and sample.

Impact on Society The scientific method provides a consistent methodological approach to researching and presenting research. By reemphasizing the definitions and applications of populations and samples in research, and by providing a writing structure that doctoral students may model in their own writing, the article supports doctoral students’ growth and development in using the scientific method.

Future Research Future researchers may wish to further advance novice researcher knowledge in developing models to guide dissertation writing. Future studies may focus on other essential areas of research, including studies about recruitment methods and attrition strategies, data collection procedures, and overall research alignment. Additionally, future researchers may wish to consider evaluating doctoral student foundational knowledge about populations and samples as part of the research process.

Back to Top ↑

- Become a Reviewer

- Privacy Policy

- Ethics Policy

- Legal Disclaimer

SEARCH PUBLICATIONS

The Growth of World Population: Analysis of the Problems and Recommendations for Research and Training (1963)

Chapter: introduction, introduction.

All nations are committed to achieving a higher standard of living for their people—adequate food, good health, literacy, education, and gainful employment. These are the goals of millions now living in privation. An important barrier to the achievement of these goals is the current rate of population growth. The present world population is likely to double in the next 35 years, producing a population of six billion by the year 2000. If the same rate of growth continues, there will be 12 billion people on earth in 70 years and over 25 billion by the year 2070. Such rapid population growth, which is out of proportion to present and prospective rates of increase in economic development, imposes a heavy burden on all efforts to improve human welfare. Moreover, since we live in an interconnected world, it is an international problem from which no one can escape.

In our judgment, this problem can be successfully attacked by developing new methods of fertility regulation, and implementing programs of voluntary family planning widely and rapidly throughout the world. Although only a few nations have made any concerted efforts in this direction, responsible groups in the social, economic, and scientific communities of many countries have become increasingly aware of the problem and the need for intelligent and forthright action. We recommend that these groups now join in a common effort to disseminate present knowledge on population problems, family planning, and related bio-medical matters, and to initiate programs of research that will advance our knowledge in these fields.

More than bio-medical research will be required, for control of population growth by means of voluntary regulation within each family poses major social and economic problems that can be solved only in part by biological means. Of special importance is the need for extensive and immediate research in the field to learn how we can make family planning more effective in societies that recognize the need for it. The challenge to students of social problems can hardly be overstated.

In view of its relationship to the welfare of all men, individually and collectively, the problem of population growth can no longer be ignored. Increased understanding of present procedures and development of new methods for regulating fertility will maximize the freedom of all parents to determine the size of their families even in those countries where population growth is not an urgent social problem but where fertility regulation can have great personal significance. It should be emphasized that the kinds of basic bio-medical investigations that will contribute to solutions of problems of human fertility will also provide information that can be applied to the development of methods for overcoming sterility, for influencing embryonic development in order to repair genetically determined biochemical deficiencies, for avoiding harmful influences of drugs taken during pregnancy, and, in general, for assuring optimum conditions for embryonic and fetal development.

In pursuit of these objectives, many different kinds of institutions in the United States, both public and private, have important contributions to make. Other than the search for lasting peace, no problem is more urgent.

READ FREE ONLINE

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

Switch between the Original Pages , where you can read the report as it appeared in print, and Text Pages for the web version, where you can highlight and search the text.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis testing is a tool for making statistical inferences about the population data. It is an analysis tool that tests assumptions and determines how likely something is within a given standard of accuracy. Hypothesis testing provides a way to verify whether the results of an experiment are valid.

A null hypothesis and an alternative hypothesis are set up before performing the hypothesis testing. This helps to arrive at a conclusion regarding the sample obtained from the population. In this article, we will learn more about hypothesis testing, its types, steps to perform the testing, and associated examples.

What is Hypothesis Testing in Statistics?

Hypothesis testing uses sample data from the population to draw useful conclusions regarding the population probability distribution . It tests an assumption made about the data using different types of hypothesis testing methodologies. The hypothesis testing results in either rejecting or not rejecting the null hypothesis.

Hypothesis Testing Definition

Hypothesis testing can be defined as a statistical tool that is used to identify if the results of an experiment are meaningful or not. It involves setting up a null hypothesis and an alternative hypothesis. These two hypotheses will always be mutually exclusive. This means that if the null hypothesis is true then the alternative hypothesis is false and vice versa. An example of hypothesis testing is setting up a test to check if a new medicine works on a disease in a more efficient manner.

Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis is a concise mathematical statement that is used to indicate that there is no difference between two possibilities. In other words, there is no difference between certain characteristics of data. This hypothesis assumes that the outcomes of an experiment are based on chance alone. It is denoted as \(H_{0}\). Hypothesis testing is used to conclude if the null hypothesis can be rejected or not. Suppose an experiment is conducted to check if girls are shorter than boys at the age of 5. The null hypothesis will say that they are the same height.

Alternative Hypothesis

The alternative hypothesis is an alternative to the null hypothesis. It is used to show that the observations of an experiment are due to some real effect. It indicates that there is a statistical significance between two possible outcomes and can be denoted as \(H_{1}\) or \(H_{a}\). For the above-mentioned example, the alternative hypothesis would be that girls are shorter than boys at the age of 5.

Hypothesis Testing P Value

In hypothesis testing, the p value is used to indicate whether the results obtained after conducting a test are statistically significant or not. It also indicates the probability of making an error in rejecting or not rejecting the null hypothesis.This value is always a number between 0 and 1. The p value is compared to an alpha level, \(\alpha\) or significance level. The alpha level can be defined as the acceptable risk of incorrectly rejecting the null hypothesis. The alpha level is usually chosen between 1% to 5%.

Hypothesis Testing Critical region

All sets of values that lead to rejecting the null hypothesis lie in the critical region. Furthermore, the value that separates the critical region from the non-critical region is known as the critical value.

Hypothesis Testing Formula

Depending upon the type of data available and the size, different types of hypothesis testing are used to determine whether the null hypothesis can be rejected or not. The hypothesis testing formula for some important test statistics are given below:

- z = \(\frac{\overline{x}-\mu}{\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}}\). \(\overline{x}\) is the sample mean, \(\mu\) is the population mean, \(\sigma\) is the population standard deviation and n is the size of the sample.

- t = \(\frac{\overline{x}-\mu}{\frac{s}{\sqrt{n}}}\). s is the sample standard deviation.

- \(\chi ^{2} = \sum \frac{(O_{i}-E_{i})^{2}}{E_{i}}\). \(O_{i}\) is the observed value and \(E_{i}\) is the expected value.

We will learn more about these test statistics in the upcoming section.

Types of Hypothesis Testing

Selecting the correct test for performing hypothesis testing can be confusing. These tests are used to determine a test statistic on the basis of which the null hypothesis can either be rejected or not rejected. Some of the important tests used for hypothesis testing are given below.

Hypothesis Testing Z Test

A z test is a way of hypothesis testing that is used for a large sample size (n ≥ 30). It is used to determine whether there is a difference between the population mean and the sample mean when the population standard deviation is known. It can also be used to compare the mean of two samples. It is used to compute the z test statistic. The formulas are given as follows:

- One sample: z = \(\frac{\overline{x}-\mu}{\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}}\).

- Two samples: z = \(\frac{(\overline{x_{1}}-\overline{x_{2}})-(\mu_{1}-\mu_{2})}{\sqrt{\frac{\sigma_{1}^{2}}{n_{1}}+\frac{\sigma_{2}^{2}}{n_{2}}}}\).

Hypothesis Testing t Test

The t test is another method of hypothesis testing that is used for a small sample size (n < 30). It is also used to compare the sample mean and population mean. However, the population standard deviation is not known. Instead, the sample standard deviation is known. The mean of two samples can also be compared using the t test.

- One sample: t = \(\frac{\overline{x}-\mu}{\frac{s}{\sqrt{n}}}\).

- Two samples: t = \(\frac{(\overline{x_{1}}-\overline{x_{2}})-(\mu_{1}-\mu_{2})}{\sqrt{\frac{s_{1}^{2}}{n_{1}}+\frac{s_{2}^{2}}{n_{2}}}}\).

Hypothesis Testing Chi Square

The Chi square test is a hypothesis testing method that is used to check whether the variables in a population are independent or not. It is used when the test statistic is chi-squared distributed.

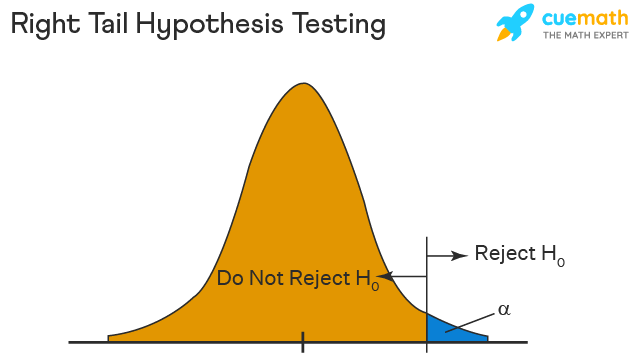

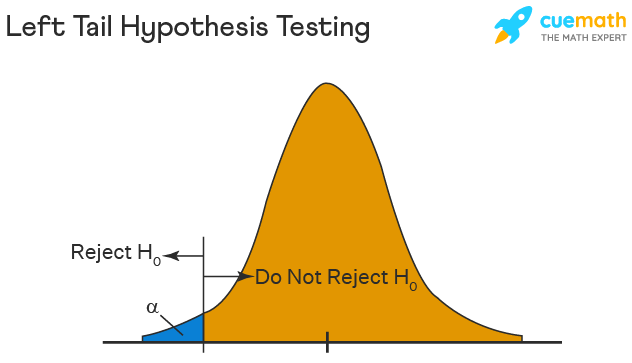

One Tailed Hypothesis Testing

One tailed hypothesis testing is done when the rejection region is only in one direction. It can also be known as directional hypothesis testing because the effects can be tested in one direction only. This type of testing is further classified into the right tailed test and left tailed test.

Right Tailed Hypothesis Testing

The right tail test is also known as the upper tail test. This test is used to check whether the population parameter is greater than some value. The null and alternative hypotheses for this test are given as follows:

\(H_{0}\): The population parameter is ≤ some value

\(H_{1}\): The population parameter is > some value.

If the test statistic has a greater value than the critical value then the null hypothesis is rejected

Left Tailed Hypothesis Testing

The left tail test is also known as the lower tail test. It is used to check whether the population parameter is less than some value. The hypotheses for this hypothesis testing can be written as follows:

\(H_{0}\): The population parameter is ≥ some value

\(H_{1}\): The population parameter is < some value.

The null hypothesis is rejected if the test statistic has a value lesser than the critical value.

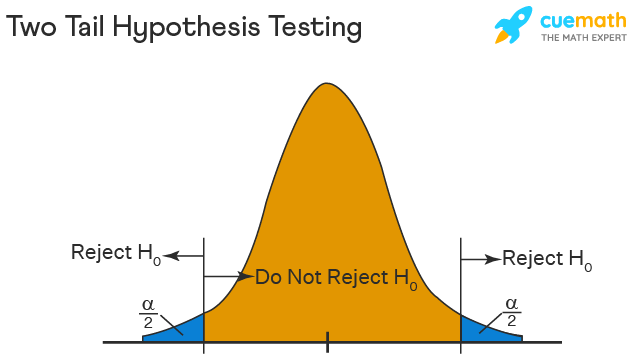

Two Tailed Hypothesis Testing

In this hypothesis testing method, the critical region lies on both sides of the sampling distribution. It is also known as a non - directional hypothesis testing method. The two-tailed test is used when it needs to be determined if the population parameter is assumed to be different than some value. The hypotheses can be set up as follows:

\(H_{0}\): the population parameter = some value

\(H_{1}\): the population parameter ≠ some value

The null hypothesis is rejected if the test statistic has a value that is not equal to the critical value.

Hypothesis Testing Steps

Hypothesis testing can be easily performed in five simple steps. The most important step is to correctly set up the hypotheses and identify the right method for hypothesis testing. The basic steps to perform hypothesis testing are as follows:

- Step 1: Set up the null hypothesis by correctly identifying whether it is the left-tailed, right-tailed, or two-tailed hypothesis testing.

- Step 2: Set up the alternative hypothesis.

- Step 3: Choose the correct significance level, \(\alpha\), and find the critical value.

- Step 4: Calculate the correct test statistic (z, t or \(\chi\)) and p-value.

- Step 5: Compare the test statistic with the critical value or compare the p-value with \(\alpha\) to arrive at a conclusion. In other words, decide if the null hypothesis is to be rejected or not.

Hypothesis Testing Example

The best way to solve a problem on hypothesis testing is by applying the 5 steps mentioned in the previous section. Suppose a researcher claims that the mean average weight of men is greater than 100kgs with a standard deviation of 15kgs. 30 men are chosen with an average weight of 112.5 Kgs. Using hypothesis testing, check if there is enough evidence to support the researcher's claim. The confidence interval is given as 95%.

Step 1: This is an example of a right-tailed test. Set up the null hypothesis as \(H_{0}\): \(\mu\) = 100.

Step 2: The alternative hypothesis is given by \(H_{1}\): \(\mu\) > 100.

Step 3: As this is a one-tailed test, \(\alpha\) = 100% - 95% = 5%. This can be used to determine the critical value.

1 - \(\alpha\) = 1 - 0.05 = 0.95

0.95 gives the required area under the curve. Now using a normal distribution table, the area 0.95 is at z = 1.645. A similar process can be followed for a t-test. The only additional requirement is to calculate the degrees of freedom given by n - 1.

Step 4: Calculate the z test statistic. This is because the sample size is 30. Furthermore, the sample and population means are known along with the standard deviation.

z = \(\frac{\overline{x}-\mu}{\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}}\).

\(\mu\) = 100, \(\overline{x}\) = 112.5, n = 30, \(\sigma\) = 15

z = \(\frac{112.5-100}{\frac{15}{\sqrt{30}}}\) = 4.56

Step 5: Conclusion. As 4.56 > 1.645 thus, the null hypothesis can be rejected.

Hypothesis Testing and Confidence Intervals

Confidence intervals form an important part of hypothesis testing. This is because the alpha level can be determined from a given confidence interval. Suppose a confidence interval is given as 95%. Subtract the confidence interval from 100%. This gives 100 - 95 = 5% or 0.05. This is the alpha value of a one-tailed hypothesis testing. To obtain the alpha value for a two-tailed hypothesis testing, divide this value by 2. This gives 0.05 / 2 = 0.025.

Related Articles:

- Probability and Statistics

- Data Handling

Important Notes on Hypothesis Testing

- Hypothesis testing is a technique that is used to verify whether the results of an experiment are statistically significant.

- It involves the setting up of a null hypothesis and an alternate hypothesis.

- There are three types of tests that can be conducted under hypothesis testing - z test, t test, and chi square test.

- Hypothesis testing can be classified as right tail, left tail, and two tail tests.

Examples on Hypothesis Testing

- Example 1: The average weight of a dumbbell in a gym is 90lbs. However, a physical trainer believes that the average weight might be higher. A random sample of 5 dumbbells with an average weight of 110lbs and a standard deviation of 18lbs. Using hypothesis testing check if the physical trainer's claim can be supported for a 95% confidence level. Solution: As the sample size is lesser than 30, the t-test is used. \(H_{0}\): \(\mu\) = 90, \(H_{1}\): \(\mu\) > 90 \(\overline{x}\) = 110, \(\mu\) = 90, n = 5, s = 18. \(\alpha\) = 0.05 Using the t-distribution table, the critical value is 2.132 t = \(\frac{\overline{x}-\mu}{\frac{s}{\sqrt{n}}}\) t = 2.484 As 2.484 > 2.132, the null hypothesis is rejected. Answer: The average weight of the dumbbells may be greater than 90lbs

- Example 2: The average score on a test is 80 with a standard deviation of 10. With a new teaching curriculum introduced it is believed that this score will change. On random testing, the score of 38 students, the mean was found to be 88. With a 0.05 significance level, is there any evidence to support this claim? Solution: This is an example of two-tail hypothesis testing. The z test will be used. \(H_{0}\): \(\mu\) = 80, \(H_{1}\): \(\mu\) ≠ 80 \(\overline{x}\) = 88, \(\mu\) = 80, n = 36, \(\sigma\) = 10. \(\alpha\) = 0.05 / 2 = 0.025 The critical value using the normal distribution table is 1.96 z = \(\frac{\overline{x}-\mu}{\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}}\) z = \(\frac{88-80}{\frac{10}{\sqrt{36}}}\) = 4.8 As 4.8 > 1.96, the null hypothesis is rejected. Answer: There is a difference in the scores after the new curriculum was introduced.

- Example 3: The average score of a class is 90. However, a teacher believes that the average score might be lower. The scores of 6 students were randomly measured. The mean was 82 with a standard deviation of 18. With a 0.05 significance level use hypothesis testing to check if this claim is true. Solution: The t test will be used. \(H_{0}\): \(\mu\) = 90, \(H_{1}\): \(\mu\) < 90 \(\overline{x}\) = 110, \(\mu\) = 90, n = 6, s = 18 The critical value from the t table is -2.015 t = \(\frac{\overline{x}-\mu}{\frac{s}{\sqrt{n}}}\) t = \(\frac{82-90}{\frac{18}{\sqrt{6}}}\) t = -1.088 As -1.088 > -2.015, we fail to reject the null hypothesis. Answer: There is not enough evidence to support the claim.

go to slide go to slide go to slide

Book a Free Trial Class

FAQs on Hypothesis Testing

What is hypothesis testing.

Hypothesis testing in statistics is a tool that is used to make inferences about the population data. It is also used to check if the results of an experiment are valid.

What is the z Test in Hypothesis Testing?

The z test in hypothesis testing is used to find the z test statistic for normally distributed data . The z test is used when the standard deviation of the population is known and the sample size is greater than or equal to 30.

What is the t Test in Hypothesis Testing?

The t test in hypothesis testing is used when the data follows a student t distribution . It is used when the sample size is less than 30 and standard deviation of the population is not known.

What is the formula for z test in Hypothesis Testing?

The formula for a one sample z test in hypothesis testing is z = \(\frac{\overline{x}-\mu}{\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}}\) and for two samples is z = \(\frac{(\overline{x_{1}}-\overline{x_{2}})-(\mu_{1}-\mu_{2})}{\sqrt{\frac{\sigma_{1}^{2}}{n_{1}}+\frac{\sigma_{2}^{2}}{n_{2}}}}\).

What is the p Value in Hypothesis Testing?

The p value helps to determine if the test results are statistically significant or not. In hypothesis testing, the null hypothesis can either be rejected or not rejected based on the comparison between the p value and the alpha level.

What is One Tail Hypothesis Testing?

When the rejection region is only on one side of the distribution curve then it is known as one tail hypothesis testing. The right tail test and the left tail test are two types of directional hypothesis testing.

What is the Alpha Level in Two Tail Hypothesis Testing?

To get the alpha level in a two tail hypothesis testing divide \(\alpha\) by 2. This is done as there are two rejection regions in the curve.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The first step in addressing the population in research is to clearly define the target population. This involves specifying the characteristics of the larger group to which the study's findings will be generalized. The target population should be explicitly defined in terms of relevant factors such as demographic characteristics, geographic ...

A population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about.. A sample is the specific group that you will collect data from. The size of the sample is always less than the total size of the population. In research, a population doesn't always refer to people. It can mean a group containing elements of anything you want to study, such as objects, events, organizations, countries ...

A study population is a group considered for a study or statistical reasoning. The study population is not limited to the human population only. It is a set of aspects that have something in common. They can be objects, animals, measurements, etc., with many characteristics within a group. For example, suppose you are interested in the average ...

A research population is generally a large collection of individuals or objects that is the main focus of a scientific query. It is for the benefit of the population that researches are done. However, due to the large sizes of populations, researchers often cannot test every individual in the population because it is too expensive and time ...

So if you want to sample one-tenth of the population, you'd select every tenth name. In order to know the k for your study you need to know your sample size (say 1000) and the size of the population (75000). You can divide the size of the population by the sample (75000/1000), which will produce your k (750).

The null hypothesis (H 0) answers "No, there's no effect in the population." The alternative hypothesis (H a) answers "Yes, there is an effect in the population." The null and alternative are always claims about the population. That's because the goal of hypothesis testing is to make inferences about a population based on a sample.

The sampling frame intersects the target population. The sam-ple and sampling frame described extends outside of the target population and population of interest as occa-sionally the sampling frame may include individuals not qualified for the study. Figure 1. The relationship between populations within research.

A population is a complete set of people with a specialized set of characteristics, and a sample is a subset of the population. The usual criteria we use in defining population are geographic, for example, "the population of Uttar Pradesh". In medical research, the criteria for population may be clinical, demographic and time related.

Survey research means collecting information about a group of people by asking them questions and analyzing the results. To conduct an effective survey, follow these six steps: Determine who will participate in the survey. Decide the type of survey (mail, online, or in-person) Design the survey questions and layout.

From its inception in 1946, Population Studies has taken a broad view of demography, reflecting the outlook of its founding editor, David Glass, and carried forward during its first 50 years by Eugene Grebenik. The aim of its 50th anniversary issue in 1996 was to describe developments in demographic research during its first 50 years of existence.

of research that is meaningful and applicable [1,2]. These terms serve as the foundation for study design, participant selection, data collection, and analysis [3]. Understanding the distinction between population and target population allows researchers to precisely identify the group of individuals under investigation

Research Popula tion and Sampling in Quantitative Study. Dalowar Hossan 1*, Zuraina Dato' Mansor and Nor Siah Jaharuddin 1. 1 School of Business & Economics, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 ...

It is a notion that has to do with business market segmentation tactics. A target population is typically a group or collection of factors you want to learn more about. The target population is a subset of the general public identified as the targeted market for a given product, advertising, or research. It is a subset of the entire population ...

The proposed writing structure provides doctoral students a model for developing the relevant population and sample descriptions in their dissertations and other research. Findings The article describes that although many definitions and uses are relatively consistent within the literature, there are epistemological differences between research ...

A sampling frame lists all members of the population you're studying. Your target population is the general concept of the group you're assessing, while a sampling frame specifically lists all population members and how to contact them. It might also include demographic information for each person because some methods, such as stratified ...

Table of contents. When to use stratified sampling. Step 1: Define your population and subgroups. Step 2: Separate the population into strata. Step 3: Decide on the sample size for each stratum. Step 4: Randomly sample from each stratum. Other interesting articles.

Abstract. This paper deals with the concept of Population and Sample in research, especially in educational and psychological researches and the researches carried out in the field of Sociology ...

Sampling design can be very simple or very complex. In the simplest, one stage sample design where there is no explicit stratification and a member of the population is chosen at random, each unit has the probability. n/N. of being in the sample, where: n is the total number of units to be sampled, N is number of units in the total population.

These are the goals of millions now living in privation. An important barrier to the achievement of these goals is the current rate of population growth. The present world population is likely to double in the next 35 years, producing a population of six billion by the year 2000.

Hypothesis testing is a tool for making statistical inferences about the population data. It is an analysis tool that tests assumptions and determines how likely something is within a given standard of accuracy. Hypothesis testing provides a way to verify whether the results of an experiment are valid. A null hypothesis and an alternative ...

Revised on June 22, 2023. Descriptive research aims to accurately and systematically describe a population, situation or phenomenon. It can answer what, where, when and how questions, but not why questions. A descriptive research design can use a wide variety of research methods to investigate one or more variables.

Solution. When people move from one place to another place, or one city to another city or one country to another country, it is called migration. The place where people go out is called the donor region. The place where people migrate is called the recipient region. Due to migration, there are changes in the total population in both regions.

Step 1: Consider your aims and approach. Step 2: Choose a type of research design. Step 3: Identify your population and sampling method. Step 4: Choose your data collection methods. Step 5: Plan your data collection procedures. Step 6: Decide on your data analysis strategies. Other interesting articles.