Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11 Engaging in Group Problem-Solving

Learning Objectives

- Discuss the common components and characteristics of problems

- Explain the five steps of the group problem-solving process

Although the steps of problem-solving and decision-making that we will discuss next may seem obvious, we often don’t think to or choose not to use them. Instead, we start working on a problem and later realize we are lost and have to backtrack. I’m sure we’ve all reached a point in a project or task and had the “OK, now what?” moment. I’ve recently taken up some carpentry projects as a functional hobby, and I have developed a great respect for the importance of advanced planning. It’s frustrating to get to a crucial point in building or fixing something only to realize that you have to unscrew a support board that you already screwed in, have to drive back to the hardware store to get something that you didn’t think to get earlier, or have to completely start over. In this section, we will discuss group problem-solving and important steps in the process.

Group Problem Solving

The problem-solving process involves thoughts, discussions, actions, and decisions that occur from the first consideration of a problematic situation to the goal. The problems that groups face are varied, but some common problems include budgeting funds, raising funds, planning events, addressing customer or citizen complaints, creating or adapting products or services to fit needs, supporting members, and raising awareness about issues or causes.

According to Adams and Galanes (2009), problems of all sorts have three common components:

- An undesirable situation. When conditions are desirable, there isn’t a problem.

- The desired situation. Even though it may only be a vague idea, there is a drive to better the undesirable situation. The vague idea may develop into a more precise goal that can be achieved, although solutions are not yet generated.

- Obstacles between undesirable and desirable situations. These are things that stand in the way between the current situation and the group’s goal of addressing it. This component of a problem requires the most work, and it is the part where decision-making occurs. Some examples of obstacles include limited funding, resources, personnel, time, or information. Obstacles can also take the form of people who are working against the group, including people resistant to change or people who disagree.

Discussion of these three elements of a problem helps the group tailor its problem-solving process, as each problem will vary. While these three general elements are present in each problem, the group should also address specific characteristics of the problem. Five common and important characteristics to consider are task difficulty, the number of possible solutions, group member interest in the problem, group member familiarity with the problem, and the need for solution acceptance (Adams & Galanes, 2009).

- Task difficulty. Difficult tasks are also typically more complex. Groups should be prepared to spend time researching and discussing difficult and complex tasks to develop a shared foundational knowledge. This typically requires individual work outside of the group and frequent group meetings to share information.

- Number of possible solutions. There are usually multiple ways to solve a problem or complete a task, but some problems have more potential solutions than others. Figuring out how to prepare a beach house for an approaching hurricane is fairly complex and difficult, but there are still a limited number of things to do—for example, taping and boarding up windows; turning off water, electricity, and gas; trimming trees; and securing loose outside objects. Other problems may be more creatively based. For example, designing a new restaurant may entail using some standard solutions but could also entail many different types of innovation with layout and design.

- Group member interest in problem. When group members are interested in the problem, they will be more engaged with the problem-solving process and invested in finding a quality solution. Groups with high interest in and knowledge about the problem may want more freedom to develop and implement solutions, while groups with low interest may prefer a leader who provides structure and direction.

- Group familiarity with problem. Some groups encounter a problem regularly, while other problems are more unique or unexpected. A family who has lived in hurricane alley for decades probably has a better idea of how to prepare their house for a hurricane than does a family that just recently moved from the Midwest. Many groups that rely on funding have to revisit a budget every year, and in recent years, groups have had to get more creative with budgets as funding has been cut in nearly every sector. When group members aren’t familiar with a problem, they will need to do background research on what similar groups have done and may also need to bring in outside experts.

- Need for solution acceptance. In this step, groups must consider how many people the decision will affect and how much “buy-in” from others the group needs for their solution to be successfully implemented. Some small groups have many stakeholders on whom the success of a solution depends. Other groups are answerable only to themselves. When a small group is planning on building a new park in a crowded neighborhood or implementing a new policy in a large business, it can be very difficult to develop solutions that will be accepted by all. In such cases, groups will want to poll those who will be affected by the solution and may want to do a pilot implementation to see how people react. Imposing an excellent solution that doesn’t have buy-in from stakeholders can still lead to failure.

Group Problem-Solving Process

There are several variations of similar problem-solving models based on American scholar John Dewey’s reflective thinking process (Bormann & Bormann, 1988). As you read through the steps in the process, think about how you can apply what you learned regarding the general and specific elements of problems. Some of the following steps are straightforward, and they are things we would logically do when faced with a problem. However, taking a deliberate and systematic approach to problem-solving has been shown to benefit group functioning and performance. A deliberate approach is especially beneficial for groups that do not have an established history of working together and will only be able to meet occasionally. Although a group should attend to each step of the process, group leaders or other group members who facilitate problem-solving should be cautious not to dogmatically follow each element of the process or force a group along. Such a lack of flexibility could limit group member input and negatively affect the group’s cohesion and climate.

Step 1: Define the Problem

Define the problem by considering the three elements shared by every problem: the current undesirable situation, the goal or more desirable situation, and obstacles in the way (Adams & Galanes, 2009). At this stage, group members share what they know about the current situation, without proposing solutions or evaluating the information. Here are some good questions to ask during this stage:

- What is the current difficulty?

- How did we come to know that the difficulty exists?

- Who/what is involved?

- Why is it meaningful/urgent/important?

- What have the effects been so far?

- What, if any, elements of the difficulty require clarification?

At the end of this stage, the group should be able to compose a single sentence that summarizes the problem called a problem statement . Avoid wording in the problem statement or question that hints at potential solutions. A small group formed to investigate ethical violations of city officials could use the following problem statement: “Our state does not currently have a mechanism for citizens to report suspected ethical violations by city officials.”

Step 2: Analyze the Problem

During this step, a group should analyze the problem and the group’s relationship to the problem. Whereas the first step involved exploring the “what” related to the problem, this step focuses on the “why.” At this stage, group members can discuss the potential causes of the difficulty. Group members may also want to begin setting out an agenda or timeline for the group’s problem-solving process, looking forward to the other steps.

To fully analyze the problem, the group can discuss the five common problem variables discussed before. Here are two examples of questions that the group formed to address ethics violations might ask: Why doesn’t our city have an ethics reporting mechanism? Do cities of similar size have such a mechanism? Once the problem has been analyzed, the group can pose a problem question that will guide the group as it generates possible solutions. “How can citizens report suspected ethical violations of city officials and how will such reports be processed and addressed?” As you can see, the problem question is more complex than the problem statement, since the group has moved on to a more in-depth discussion of the problem during step 2.

Step 3: Generate Possible Solutions

During this step, group members generate possible solutions to the problem. This is where brainstorming techniques to enhance creativity may be useful to the group (see earlier chapter on “Enhancing Creativity”). Again, solutions should not be evaluated at this point, only proposed and clarified. The question should be what could we do to address this problem, not what should we do to address it. It is perfectly OK for a group member to question another person’s idea by asking something like “What do you mean?” or “Could you explain your reasoning more?” Discussions at this stage may reveal a need to return to previous steps to better define or more fully analyze a problem. Since many problems are multifaceted, group members must generate solutions for each part of the problem separately, making sure to have multiple solutions for each part. Stopping the solution-generating process prematurely can lead to groupthink.

For the problem question previously posed, the group would need to generate solutions for all three parts of the problem included in the question. Possible solutions for the first part of the problem (How can citizens report ethical violations?) may include “online reporting system, e-mail, in-person, anonymously, on-the-record,” and so on. Possible solutions for the second part of the problem (How will reports be processed?) may include “daily by a newly appointed ethics officer, weekly by a nonpartisan non-government employee,” and so on. Possible solutions for the third part of the problem (How will reports be addressed?) may include “by a newly appointed ethics commission, by the accused’s supervisor, by the city manager,” and so on.

Step 4: Evaluate Solutions

During this step, solutions can be critically evaluated based on their credibility, completeness, and worth. Once the potential solutions have been narrowed based on more obvious differences in relevance and/or merit, the group should analyze each solution based on its potential effects—especially negative effects. Groups that are required to report the rationale for their decision or whose decisions may be subject to public scrutiny would be wise to make a set list of criteria for evaluating each solution. Additionally, solutions can be evaluated based on how well they fit with the group’s charge and the abilities of the group. To do this, group members may ask, “Does this solution live up to the original purpose or mission of the group?” and “Can the solution actually be implemented with our current resources and connections?” and “How will this solution be supported, funded, enforced, and assessed?” Conflict may emerge during this step of problem-solving, and group members will need to employ effective critical thinking and listening skills.

Decision-making is part of the larger process of problem-solving and it plays a prominent role in this step. While there are several fairly similar models for problem-solving, there are many varied decision-making techniques that groups can use (see earlier chapter on “Decision-Making in Groups”). For example, to narrow the list of proposed solutions, group members may decide by majority vote, by weighing the pros and cons, or by discussing them until a consensus is reached. There are also more complex decision-making models like the “six hats method,” which we will discuss later. Once the final decision is reached, the group leader or facilitator should confirm that the group is in agreement. It may be beneficial to let the group break for a while or even to delay the final decision until a later meeting to allow people time to evaluate it outside of the group context.

Step 5: Implement and Assess the Solution

Implementing the solution requires some advanced planning, and it should not be rushed unless the group is operating under strict time restraints or delay may lead to some kind of harm. Although some solutions can be implemented immediately, others may take days, months, or years. As was noted earlier, it may be beneficial for groups to poll those who will be affected by the solution as to their opinion of it or even do a pilot test to observe the effectiveness of the solution and how people react to it. Before implementation, groups should also determine how and when they would assess the effectiveness of the solution by asking, “How will we know if the solution is working or not?” Since solution assessment will vary based on whether or not the group is disbanded, groups should also consider the following questions: If the group disbands after implementation, who will be responsible for assessing the solution? If the solution fails, will the same group reconvene or will a new group be formed?

Certain elements of the solution may need to be delegated out to various people inside and outside the group. Group members may also be assigned to implement a particular part of the solution based on their role in the decision-making or because it connects to their area of expertise. Likewise, group members may be tasked with publicizing the solution or “selling” it to a particular group of stakeholders. Last, the group should consider its future. In some cases, the group will get to decide if it will stay together and continue working on other tasks or if it will disband. In other cases, outside forces determine the group’s fate.

Six Thinking Hats Method

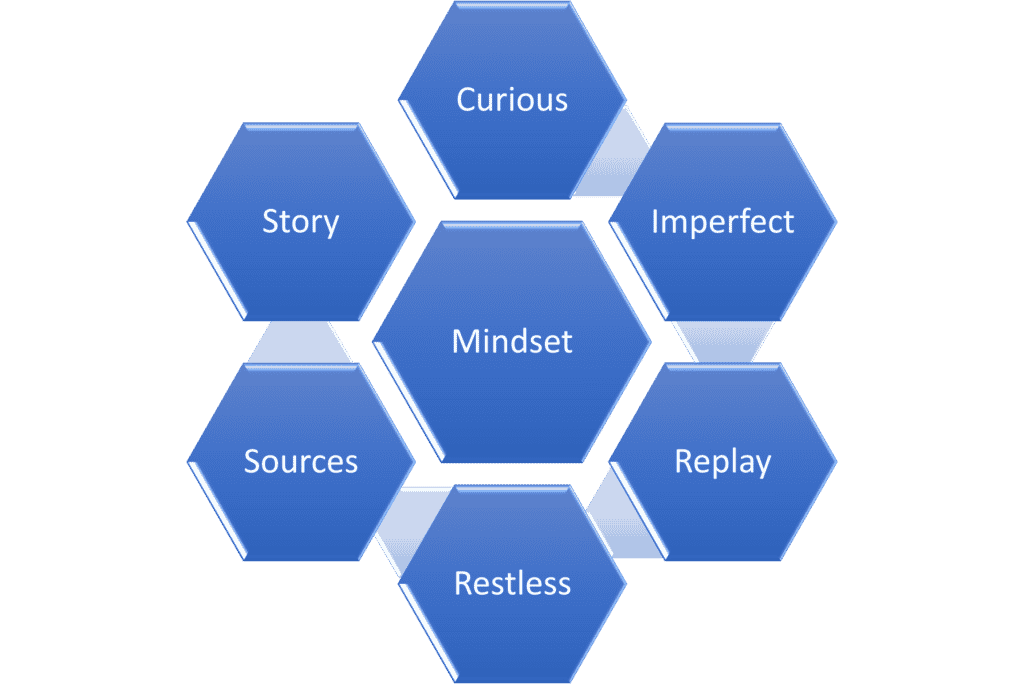

Edward de Bono developed the Six Thinking Hats method of thinking in the late 1980s, and it has since become a regular feature in problem-solving and decision-making training in business and professional contexts (de Bono, 1985). The method’s popularity lies in its ability to help people get out of habitual ways of thinking and to allow group members to play different roles and see a problem or decision from multiple points of view. The basic idea is that each of the six hats represents a different way of thinking, and when we figuratively switch hats, we switch the way we think. The hats and their style of thinking are as follows:

- White hat. Objective—focuses on seeking information such as data and facts and then neutrally processes that information.

- Red hat. Emotional—uses intuition, gut reactions, and feelings to judge information and suggestions.

- Black hat. Critical—focuses on potential risks, points out possibilities for failure, and evaluates information cautiously and defensively.

- Yellow hat. Positive—is optimistic about suggestions and future outcomes, gives constructive and positive feedback, points out benefits and advantages.

- Green hat. Creative—tries to generate new ideas and solutions, thinks “outside the box.”

- Blue hat. Process—uses metacommunication to organize and reflect on the thinking and communication taking place in the group, facilitates who wears what hat and when group members change hats.

Specific sequences or combinations of hats can be used to encourage strategic thinking. For example, the group leader may start off wearing the Blue Hat and suggest that the group start their decision-making process with some “White Hat thinking” to process through facts and other available information. During this stage, the group could also process through what other groups have done when faced with a similar problem. Then the leader could begin an evaluation sequence starting with two minutes of “Yellow Hat thinking” to identify potential positive outcomes, then “Black Hat thinking” to allow group members to express reservations about ideas and point out potential problems, then “Red Hat thinking” to get people’s gut reactions to the previous discussion, then “Green Hat thinking” to identify other possible solutions that are more tailored to the group’s situation or completely new approaches. At the end of a sequence, the Blue Hat would want to summarize what was said and begin a new sequence. To successfully use this method, the person wearing the Blue Hat should be familiar with different sequences and plan some of the thinking patterns ahead of time based on the problem and the group members. Each round of thinking should be limited to a certain time frame (two to five minutes) to keep the discussion moving.

- This problem-solving method has been praised because it allows group members to “switch gears” in their thinking and allows for role-playing, which lets people express ideas more freely. How can this help enhance critical thinking? Which combination of hats do you think would be best for a critical thinking sequence?

- What combinations of hats might be useful if the leader wanted to break the larger group up into pairs and why? For example, what kind of thinking would result from putting Yellow and Red together, Black and White together, or Red and White together, and so on?

- Based on your preferred ways of thinking and your personality, which hat would be the best fit for you? Which would be the most challenging? Why?

Review & Reflection Questions

- What are the three common components of a problem? Based on these, what problems have you encountered in your group?

- What are the five steps of the reflective thinking process?

- What challenges might you face during the process and what strategies could you use to address those challenges?

- Adams, K., & Galanes, G. G. (2009). Communicating in groups: Applications and skills (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Bormann, E. G., & Nancy C. Bormann, N. C. (1988). Effective small group communication ( 4th ed). Burgess CA.

- de Bono, E. (1985). Six thinking hats. Little Brown.

Authors & Attribution

The chapter is adapted from “ Problem Solving and Decision Making in Groups ” in Communication in the Real World from the University of Minnesota. The book was adapted from a work produced and distributed under a Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC-SA) by a publisher who has requested that they and the original author not receive attribution. This work is made available under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license .

involves thoughts, discussions, actions, and decisions that occur from the first consideration of a problematic situation to the goal

a five step process to aid in group problem solving involving (1) defining the problem, (2) analyzing the problem, (3) generating possible solutions, (4) evaluating solutions, and (5) implementing and assessing the solution

a method of problem-solving developed by Edward de Bono that aims to help people get out of habitual ways of thinking and to allow group members to play different roles and see a problem or decision from multiple points of view

Small Group Communication Copyright © 2020 by Jasmine R. Linabary, Ph.D. is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

7 Strategies for Better Group Decision-Making

- Torben Emmerling

- Duncan Rooders

What we’ve learned from behavioral science.

There are upsides and downsides to making decisions in a group. The main risks include falling into groupthink or other biases that will distort the process and the ultimate outcome. But bringing more minds together to solve a problem has its advantages. To make use of those upsides and increase the chances your team will land on a successful solution, the authors recommend using seven strategies, which have been backed by behavioral science research: Keep the group small, especially when you need to make an important decision. Bring a diverse group together. Appoint a devil’s advocate. Collect opinions independently. Provide a safe space to speak up. Don’t over-rely on experts. And share collective responsibility for the outcome.

When you have a tough business problem to solve, you likely bring it to a group. After all, more minds are better than one, right? Not necessarily. Larger pools of knowledge are by no means a guarantee of better outcomes. Because of an over-reliance on hierarchy, an instinct to prevent dissent, and a desire to preserve harmony, many groups fall into groupthink .

- Torben Emmerling is the founder and managing partner of Affective Advisory and the author of the D.R.I.V.E.® framework for behavioral insights in strategy and public policy. He is a founding member and nonexecutive director on the board of the Global Association of Applied Behavioural Scientists ( GAABS ) and a seasoned lecturer, keynote speaker, and author in behavioral science and applied consumer psychology.

- DR Duncan Rooders is the CEO of a Single Family Office and a strategic advisor to Affective Advisory . He is a former B747 pilot, a graduate of Harvard Business School’s Owner/President Management program. He is the founder of Behavioural Science for Business (BSB) and an advisor to several international organizations in strategic and team decision-making.”, and a consultant to several international organizations in strategic and financial decision making.

Partner Center

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

13.1 Understanding Small Groups

Learning objectives.

- Define small group communication.

- Discuss the characteristics of small groups.

- Explain the functions of small groups.

- Compare and contrast different types of small groups.

- Discuss advantages and disadvantages of small groups.

Most of the communication skills discussed in this book are directed toward dyadic communication, meaning that they are applied in two-person interactions. While many of these skills can be transferred to and used in small group contexts, the more complex nature of group interaction necessitates some adaptation and some additional skills. Small group communication refers to interactions among three or more people who are connected through a common purpose, mutual influence, and a shared identity. In this section, we will learn about the characteristics, functions, and types of small groups.

Characteristics of Small Groups

Different groups have different characteristics, serve different purposes, and can lead to positive, neutral, or negative experiences. While our interpersonal relationships primarily focus on relationship building, small groups usually focus on some sort of task completion or goal accomplishment. A college learning community focused on math and science, a campaign team for a state senator, and a group of local organic farmers are examples of small groups that would all have a different size, structure, identity, and interaction pattern.

Size of Small Groups

There is no set number of members for the ideal small group. A small group requires a minimum of three people (because two people would be a pair or dyad), but the upper range of group size is contingent on the purpose of the group. When groups grow beyond fifteen to twenty members, it becomes difficult to consider them a small group based on the previous definition. An analysis of the number of unique connections between members of small groups shows that they are deceptively complex. For example, within a six-person group, there are fifteen separate potential dyadic connections, and a twelve-person group would have sixty-six potential dyadic connections (Hargie, 2011). As you can see, when we double the number of group members, we more than double the number of connections, which shows that network connection points in small groups grow exponentially as membership increases. So, while there is no set upper limit on the number of group members, it makes sense that the number of group members should be limited to those necessary to accomplish the goal or serve the purpose of the group. Small groups that add too many members increase the potential for group members to feel overwhelmed or disconnected.

Structure of Small Groups

Internal and external influences affect a group’s structure. In terms of internal influences, member characteristics play a role in initial group formation. For instance, a person who is well informed about the group’s task and/or highly motivated as a group member may emerge as a leader and set into motion internal decision-making processes, such as recruiting new members or assigning group roles, that affect the structure of a group (Ellis & Fisher, 1994). Different members will also gravitate toward different roles within the group and will advocate for certain procedures and courses of action over others. External factors such as group size, task, and resources also affect group structure. Some groups will have more control over these external factors through decision making than others. For example, a commission that is put together by a legislative body to look into ethical violations in athletic organizations will likely have less control over its external factors than a self-created weekly book club.

A self-formed study group likely has a more flexible structure than a city council committee.

William Rotza – Group – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Group structure is also formed through formal and informal network connections. In terms of formal networks, groups may have clearly defined roles and responsibilities or a hierarchy that shows how members are connected. The group itself may also be a part of an organizational hierarchy that networks the group into a larger organizational structure. This type of formal network is especially important in groups that have to report to external stakeholders. These external stakeholders may influence the group’s formal network, leaving the group little or no control over its structure. Conversely, groups have more control over their informal networks, which are connections among individuals within the group and among group members and people outside of the group that aren’t official. For example, a group member’s friend or relative may be able to secure a space to hold a fundraiser at a discounted rate, which helps the group achieve its task. Both types of networks are important because they may help facilitate information exchange within a group and extend a group’s reach in order to access other resources.

Size and structure also affect communication within a group (Ellis & Fisher, 1994). In terms of size, the more people in a group, the more issues with scheduling and coordination of communication. Remember that time is an important resource in most group interactions and a resource that is usually strained. Structure can increase or decrease the flow of communication. Reachability refers to the way in which one member is or isn’t connected to other group members. For example, the “Circle” group structure in Figure 13.1 “Small Group Structures” shows that each group member is connected to two other members. This can make coordination easy when only one or two people need to be brought in for a decision. In this case, Erik and Callie are very reachable by Winston, who could easily coordinate with them. However, if Winston needed to coordinate with Bill or Stephanie, he would have to wait on Erik or Callie to reach that person, which could create delays. The circle can be a good structure for groups who are passing along a task and in which each member is expected to progressively build on the others’ work. A group of scholars coauthoring a research paper may work in such a manner, with each person adding to the paper and then passing it on to the next person in the circle. In this case, they can ask the previous person questions and write with the next person’s area of expertise in mind. The “Wheel” group structure in Figure 13.1 “Small Group Structures” shows an alternative organization pattern. In this structure, Tara is very reachable by all members of the group. This can be a useful structure when Tara is the person with the most expertise in the task or the leader who needs to review and approve work at each step before it is passed along to other group members. But Phillip and Shadow, for example, wouldn’t likely work together without Tara being involved.

Figure 13.1 Small Group Structures

Looking at the group structures, we can make some assumptions about the communication that takes place in them. The wheel is an example of a centralized structure, while the circle is decentralized. Research has shown that centralized groups are better than decentralized groups in terms of speed and efficiency (Ellis & Fisher, 1994). But decentralized groups are more effective at solving complex problems. In centralized groups like the wheel, the person with the most connections, person C, is also more likely to be the leader of the group or at least have more status among group members, largely because that person has a broad perspective of what’s going on in the group. The most central person can also act as a gatekeeper. Since this person has access to the most information, which is usually a sign of leadership or status, he or she could consciously decide to limit the flow of information. But in complex tasks, that person could become overwhelmed by the burden of processing and sharing information with all the other group members. The circle structure is more likely to emerge in groups where collaboration is the goal and a specific task and course of action isn’t required under time constraints. While the person who initiated the group or has the most expertise in regards to the task may emerge as a leader in a decentralized group, the equal access to information lessens the hierarchy and potential for gatekeeping that is present in the more centralized groups.

Interdependence

Small groups exhibit interdependence , meaning they share a common purpose and a common fate. If the actions of one or two group members lead to a group deviating from or not achieving their purpose, then all members of the group are affected. Conversely, if the actions of only a few of the group members lead to success, then all members of the group benefit. This is a major contributor to many college students’ dislike of group assignments, because they feel a loss of control and independence that they have when they complete an assignment alone. This concern is valid in that their grades might suffer because of the negative actions of someone else or their hard work may go to benefit the group member who just skated by. Group meeting attendance is a clear example of the interdependent nature of group interaction. Many of us have arrived at a group meeting only to find half of the members present. In some cases, the group members who show up have to leave and reschedule because they can’t accomplish their task without the other members present. Group members who attend meetings but withdraw or don’t participate can also derail group progress. Although it can be frustrating to have your job, grade, or reputation partially dependent on the actions of others, the interdependent nature of groups can also lead to higher-quality performance and output, especially when group members are accountable for their actions.

Shared Identity

The shared identity of a group manifests in several ways. Groups may have official charters or mission and vision statements that lay out the identity of a group. For example, the Girl Scout mission states that “Girl Scouting builds girls of courage, confidence, and character, who make the world a better place” (Girl Scouts, 2012). The mission for this large organization influences the identities of the thousands of small groups called troops. Group identity is often formed around a shared goal and/or previous accomplishments, which adds dynamism to the group as it looks toward the future and back on the past to inform its present. Shared identity can also be exhibited through group names, slogans, songs, handshakes, clothing, or other symbols. At a family reunion, for example, matching t-shirts specially made for the occasion, dishes made from recipes passed down from generation to generation, and shared stories of family members that have passed away help establish a shared identity and social reality.

A key element of the formation of a shared identity within a group is the establishment of the in-group as opposed to the out-group. The degree to which members share in the in-group identity varies from person to person and group to group. Even within a family, some members may not attend a reunion or get as excited about the matching t-shirts as others. Shared identity also emerges as groups become cohesive, meaning they identify with and like the group’s task and other group members. The presence of cohesion and a shared identity leads to a building of trust, which can also positively influence productivity and members’ satisfaction.

Functions of Small Groups

Why do we join groups? Even with the challenges of group membership that we have all faced, we still seek out and desire to be a part of numerous groups. In some cases, we join a group because we need a service or access to information. We may also be drawn to a group because we admire the group or its members. Whether we are conscious of it or not, our identities and self-concepts are built on the groups with which we identify. So, to answer the earlier question, we join groups because they function to help us meet instrumental, interpersonal, and identity needs.

Groups Meet Instrumental Needs

Groups have long served the instrumental needs of humans, helping with the most basic elements of survival since ancient humans first evolved. Groups helped humans survive by providing security and protection through increased numbers and access to resources. Today, groups are rarely such a matter of life and death, but they still serve important instrumental functions. Labor unions, for example, pool efforts and resources to attain material security in the form of pay increases and health benefits for their members, which protects them by providing a stable and dependable livelihood. Individual group members must also work to secure the instrumental needs of the group, creating a reciprocal relationship. Members of labor unions pay dues that help support the group’s efforts. Some groups also meet our informational needs. Although they may not provide material resources, they enrich our knowledge or provide information that we can use to then meet our own instrumental needs. Many groups provide referrals to resources or offer advice. For example, several consumer protection and advocacy groups have been formed to offer referrals for people who have been the victim of fraudulent business practices. Whether a group forms to provide services to members that they couldn’t get otherwise, advocate for changes that will affect members’ lives, or provide information, many groups meet some type of instrumental need.

Groups Meet Interpersonal Needs

Group membership meets interpersonal needs by giving us access to inclusion, control, and support. In terms of inclusion, people have a fundamental drive to be a part of a group and to create and maintain social bonds. As we’ve learned, humans have always lived and worked in small groups. Family and friendship groups, shared-interest groups, and activity groups all provide us with a sense of belonging and being included in an in-group. People also join groups because they want to have some control over a decision-making process or to influence the outcome of a group. Being a part of a group allows people to share opinions and influence others. Conversely, some people join a group to be controlled, because they don’t want to be the sole decision maker or leader and instead want to be given a role to follow.

Just as we enter into interpersonal relationships because we like someone, we are drawn toward a group when we are attracted to it and/or its members. Groups also provide support for others in ways that supplement the support that we get from significant others in interpersonal relationships. Some groups, like therapy groups for survivors of sexual assault or support groups for people with cancer, exist primarily to provide emotional support. While these groups may also meet instrumental needs through connections and referrals to resources, they fulfill the interpersonal need for belonging that is a central human need.

Groups Meet Identity Needs

Our affiliations are building blocks for our identities, because group membership allows us to use reference groups for social comparison—in short, identifying us with some groups and characteristics and separating us from others. Some people join groups to be affiliated with people who share similar or desirable characteristics in terms of beliefs, attitudes, values, or cultural identities. For example, people may join the National Organization for Women because they want to affiliate with others who support women’s rights or a local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) because they want to affiliate with African Americans, people concerned with civil rights, or a combination of the two. Group memberships vary in terms of how much they affect our identity, as some are more prominent than others at various times in our lives. While religious groups as a whole are too large to be considered small groups, the work that people do as a part of a religious community—as a lay leader, deacon, member of a prayer group, or committee—may have deep ties to a person’s identity.

Group membership helps meet our interpersonal needs by providing an opportunity for affection and inclusion.

Lostintheredwoods – Spiral of Hands – CC BY-ND 2.0.

The prestige of a group can initially attract us because we want that group’s identity to “rub off” on our own identity. Likewise, the achievements we make as a group member can enhance our self-esteem, add to our reputation, and allow us to create or project certain identity characteristics to engage in impression management. For example, a person may take numerous tests to become a part of Mensa, which is an organization for people with high IQs, for no material gain but for the recognition or sense of achievement that the affiliation may bring. Likewise, people may join sports teams, professional organizations, and honor societies for the sense of achievement and affiliation. Such groups allow us opportunities to better ourselves by encouraging further development of skills or knowledge. For example, a person who used to play the oboe in high school may join the community band to continue to improve on his or her ability.

Types of Small Groups

There are many types of small groups, but the most common distinction made between types of small groups is that of task-oriented and relational-oriented groups (Hargie, 2011). Task-oriented groups are formed to solve a problem, promote a cause, or generate ideas or information (McKay, Davis, & Fanning, 1995). In such groups, like a committee or study group, interactions and decisions are primarily evaluated based on the quality of the final product or output. The three main types of tasks are production, discussion, and problem-solving tasks (Ellis & Fisher, 1994). Groups faced with production tasks are asked to produce something tangible from their group interactions such as a report, design for a playground, musical performance, or fundraiser event. Groups faced with discussion tasks are asked to talk through something without trying to come up with a right or wrong answer. Examples of this type of group include a support group for people with HIV/AIDS, a book club, or a group for new fathers. Groups faced with problem-solving tasks have to devise a course of action to meet a specific need. These groups also usually include a production and discussion component, but the end goal isn’t necessarily a tangible product or a shared social reality through discussion. Instead, the end goal is a well-thought-out idea. Task-oriented groups require honed problem-solving skills to accomplish goals, and the structure of these groups is more rigid than that of relational-oriented groups.

Relational-oriented groups are formed to promote interpersonal connections and are more focused on quality interactions that contribute to the well-being of group members. Decision making is directed at strengthening or repairing relationships rather than completing discrete tasks or debating specific ideas or courses of action. All groups include task and relational elements, so it’s best to think of these orientations as two ends of a continuum rather than as mutually exclusive. For example, although a family unit works together daily to accomplish tasks like getting the kids ready for school and friendship groups may plan a surprise party for one of the members, their primary and most meaningful interactions are still relational. Since other chapters in this book focus specifically on interpersonal relationships, this chapter focuses more on task-oriented groups and the dynamics that operate within these groups.

To more specifically look at the types of small groups that exist, we can examine why groups form. Some groups are formed based on interpersonal relationships. Our family and friends are considered primary groups , or long-lasting groups that are formed based on relationships and include significant others. These are the small groups in which we interact most frequently. They form the basis of our society and our individual social realities. Kinship networks provide important support early in life and meet physiological and safety needs, which are essential for survival. They also meet higher-order needs such as social and self-esteem needs. When people do not interact with their biological family, whether voluntarily or involuntarily, they can establish fictive kinship networks, which are composed of people who are not biologically related but fulfill family roles and help provide the same support.

We also interact in many secondary groups , which are characterized by less frequent face-to-face interactions, less emotional and relational communication, and more task-related communication than primary groups (Barker, 1991). While we are more likely to participate in secondary groups based on self-interest, our primary-group interactions are often more reciprocal or other oriented. For example, we may join groups because of a shared interest or need.

Groups formed based on shared interest include social groups and leisure groups such as a group of independent film buffs, science fiction fans, or bird watchers. Some groups form to meet the needs of individuals or of a particular group of people. Examples of groups that meet the needs of individuals include study groups or support groups like a weight loss group. These groups are focused on individual needs, even though they meet as a group, and they are also often discussion oriented. Service groups, on the other hand, work to meet the needs of individuals but are task oriented. Service groups include Habitat for Humanity and Rotary Club chapters, among others. Still other groups form around a shared need, and their primary task is advocacy. For example, the Gay Men’s Health Crisis is a group that was formed by a small group of eight people in the early 1980s to advocate for resources and support for the still relatively unknown disease that would later be known as AIDS. Similar groups form to advocate for everything from a stop sign at a neighborhood intersection to the end of human trafficking.

As we already learned, other groups are formed primarily to accomplish a task. Teams are task-oriented groups in which members are especially loyal and dedicated to the task and other group members (Larson & LaFasto, 1989). In professional and civic contexts, the word team has become popularized as a means of drawing on the positive connotations of the term—connotations such as “high-spirited,” “cooperative,” and “hardworking.” Scholars who have spent years studying highly effective teams have identified several common factors related to their success. Successful teams have (Adler & Elmhorst, 2005)

- clear and inspiring shared goals,

- a results-driven structure,

- competent team members,

- a collaborative climate,

- high standards for performance,

- external support and recognition, and

- ethical and accountable leadership.

Increasingly, small groups and teams are engaging in more virtual interaction. Virtual groups take advantage of new technologies and meet exclusively or primarily online to achieve their purpose or goal. Some virtual groups may complete their task without ever being physically face-to-face. Virtual groups bring with them distinct advantages and disadvantages that you can read more about in the “Getting Plugged In” feature next.

“Getting Plugged In”

Virtual Groups

Virtual groups are now common in academic, professional, and personal contexts, as classes meet entirely online, work teams interface using webinar or video-conferencing programs, and people connect around shared interests in a variety of online settings. Virtual groups are popular in professional contexts because they can bring together people who are geographically dispersed (Ahuja & Galvin, 2003). Virtual groups also increase the possibility for the inclusion of diverse members. The ability to transcend distance means that people with diverse backgrounds and diverse perspectives are more easily accessed than in many offline groups.

One disadvantage of virtual groups stems from the difficulties that technological mediation presents for the relational and social dimensions of group interactions (Walther & Bunz, 2005). As we will learn later in this chapter, an important part of coming together as a group is the socialization of group members into the desired norms of the group. Since norms are implicit, much of this information is learned through observation or conveyed informally from one group member to another. In fact, in traditional groups, group members passively acquire 50 percent or more of their knowledge about group norms and procedures, meaning they observe rather than directly ask (Comer, 1991). Virtual groups experience more difficulty with this part of socialization than copresent traditional groups do, since any form of electronic mediation takes away some of the richness present in face-to-face interaction.

To help overcome these challenges, members of virtual groups should be prepared to put more time and effort into building the relational dimensions of their group. Members of virtual groups need to make the social cues that guide new members’ socialization more explicit than they would in an offline group (Ahuja & Galvin, 2003). Group members should also contribute often, even if just supporting someone else’s contribution, because increased participation has been shown to increase liking among members of virtual groups (Walther & Bunz, 2005). Virtual group members should also make an effort to put relational content that might otherwise be conveyed through nonverbal or contextual means into the verbal part of a message, as members who include little social content in their messages or only communicate about the group’s task are more negatively evaluated. Virtual groups who do not overcome these challenges will likely struggle to meet deadlines, interact less frequently, and experience more absenteeism. What follows are some guidelines to help optimize virtual groups (Walter & Bunz, 2005):

- Get started interacting as a group as early as possible, since it takes longer to build social cohesion.

- Interact frequently to stay on task and avoid having work build up.

- Start working toward completing the task while initial communication about setup, organization, and procedures are taking place.

- Respond overtly to other people’s messages and contributions.

- Be explicit about your reactions and thoughts since typical nonverbal expressions may not be received as easily in virtual groups as they would be in colocated groups.

- Set deadlines and stick to them.

- Make a list of some virtual groups to which you currently belong or have belonged to in the past. What are some differences between your experiences in virtual groups versus traditional colocated groups?

- What are some group tasks or purposes that you think lend themselves to being accomplished in a virtual setting? What are some group tasks or purposes that you think would be best handled in a traditional colocated setting? Explain your answers for each.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Small Groups

As with anything, small groups have their advantages and disadvantages. Advantages of small groups include shared decision making, shared resources, synergy, and exposure to diversity. It is within small groups that most of the decisions that guide our country, introduce local laws, and influence our family interactions are made. In a democratic society, participation in decision making is a key part of citizenship. Groups also help in making decisions involving judgment calls that have ethical implications or the potential to negatively affect people. Individuals making such high-stakes decisions in a vacuum could have negative consequences given the lack of feedback, input, questioning, and proposals for alternatives that would come from group interaction. Group members also help expand our social networks, which provide access to more resources. A local community-theater group may be able to put on a production with a limited budget by drawing on these connections to get set-building supplies, props, costumes, actors, and publicity in ways that an individual could not. The increased knowledge, diverse perspectives, and access to resources that groups possess relates to another advantage of small groups—synergy.

Synergy refers to the potential for gains in performance or heightened quality of interactions when complementary members or member characteristics are added to existing ones (Larson Jr., 2010). Because of synergy, the final group product can be better than what any individual could have produced alone. When I worked in housing and residence life, I helped coordinate a “World Cup Soccer Tournament” for the international students that lived in my residence hall. As a group, we created teams representing different countries around the world, made brackets for people to track progress and predict winners, got sponsors, gathered prizes, and ended up with a very successful event that would not have been possible without the synergy created by our collective group membership. The members of this group were also exposed to international diversity that enriched our experiences, which is also an advantage of group communication.

Participating in groups can also increase our exposure to diversity and broaden our perspectives. Although groups vary in the diversity of their members, we can strategically choose groups that expand our diversity, or we can unintentionally end up in a diverse group. When we participate in small groups, we expand our social networks, which increase the possibility to interact with people who have different cultural identities than ourselves. Since group members work together toward a common goal, shared identification with the task or group can give people with diverse backgrounds a sense of commonality that they might not have otherwise. Even when group members share cultural identities, the diversity of experience and opinion within a group can lead to broadened perspectives as alternative ideas are presented and opinions are challenged and defended. One of my favorite parts of facilitating class discussion is when students with different identities and/or perspectives teach one another things in ways that I could not on my own. This example brings together the potential of synergy and diversity. People who are more introverted or just avoid group communication and voluntarily distance themselves from groups—or are rejected from groups—risk losing opportunities to learn more about others and themselves.

A social loafer is a dreaded group member who doesn’t do his or her share of the work, expecting that others on the group won’t notice or will pick up the slack.

Henry Burrows – Sleeping On The Job – CC BY-SA 2.0.

There are also disadvantages to small group interaction. In some cases, one person can be just as or more effective than a group of people. Think about a situation in which a highly specialized skill or knowledge is needed to get something done. In this situation, one very knowledgeable person is probably a better fit for the task than a group of less knowledgeable people. Group interaction also has a tendency to slow down the decision-making process. Individuals connected through a hierarchy or chain of command often work better in situations where decisions must be made under time constraints. When group interaction does occur under time constraints, having one “point person” or leader who coordinates action and gives final approval or disapproval on ideas or suggestions for actions is best.

Group communication also presents interpersonal challenges. A common problem is coordinating and planning group meetings due to busy and conflicting schedules. Some people also have difficulty with the other-centeredness and self-sacrifice that some groups require. The interdependence of group members that we discussed earlier can also create some disadvantages. Group members may take advantage of the anonymity of a group and engage in social loafing , meaning they contribute less to the group than other members or than they would if working alone (Karau & Williams, 1993). Social loafers expect that no one will notice their behaviors or that others will pick up their slack. It is this potential for social loafing that makes many students and professionals dread group work, especially those who have a tendency to cover for other group members to prevent the social loafer from diminishing the group’s productivity or output.

“Getting Competent”

Improving Your Group Experiences

Like many of you, I also had some negative group experiences in college that made me think similarly to a student who posted the following on a teaching blog: “Group work is code for ‘work as a group for a grade less than what you can get if you work alone’” (Weimer, 2008). But then I took a course called “Small Group and Team Communication” with an amazing teacher who later became one of my most influential mentors. She emphasized the fact that we all needed to increase our knowledge about group communication and group dynamics in order to better our group communication experiences—and she was right. So the first piece of advice to help you start improving your group experiences is to closely study the group communication chapters in this textbook and to apply what you learn to your group interactions. Neither students nor faculty are born knowing how to function as a group, yet students and faculty often think we’re supposed to learn as we go, which increases the likelihood of a negative experience.

A second piece of advice is to meet often with your group (Myers & Goodboy, 2005). Of course, to do this you have to overcome some scheduling and coordination difficulties, but putting other things aside to work as a group helps set up a norm that group work is important and worthwhile. Regular meetings also allow members to interact with each other, which can increase social bonds, build a sense of interdependence that can help diminish social loafing, and establish other important rules and norms that will guide future group interaction. Instead of committing to frequent meetings, many student groups use their first meeting to equally divide up the group’s tasks so they can then go off and work alone (not as a group). While some group work can definitely be done independently, dividing up the work and assigning someone to put it all together doesn’t allow group members to take advantage of one of the most powerful advantages of group work—synergy.

Last, establish group expectations and follow through with them. I recommend that my students come up with a group name and create a contract of group guidelines during their first meeting (both of which I learned from my group communication teacher whom I referenced earlier). The group name helps begin to establish a shared identity, which then contributes to interdependence and improves performance. The contract of group guidelines helps make explicit the group norms that might have otherwise been left implicit. Each group member contributes to the contract and then they all sign it. Groups often make guidelines about how meetings will be run, what to do about lateness and attendance, the type of climate they’d like for discussion, and other relevant expectations. If group members end up falling short of these expectations, the other group members can remind the straying member of the contact and the fact that he or she signed it. If the group encounters further issues, they can use the contract as a basis for evaluating the other group member or for communicating with the instructor.

- Do you agree with the student’s quote about group work that was included at the beginning? Why or why not?

- The second recommendation is to meet more with your group. Acknowledging that schedules are difficult to coordinate and that that is not really going to change, what are some strategies that you could use to overcome that challenge in order to get time together as a group?

- What are some guidelines that you think you’d like to include in your contract with a future group?

Key Takeaways

- Getting integrated: Small group communication refers to interactions among three or more people who are connected through a common purpose, mutual influence, and a shared identity. Small groups are important communication units in academic, professional, civic, and personal contexts.

Several characteristics influence small groups, including size, structure, interdependence, and shared identity.

- In terms of size, small groups must consist of at least three people, but there is no set upper limit on the number of group members. The ideal number of group members is the smallest number needed to competently complete the group’s task or achieve the group’s purpose.

- Internal influences such as member characteristics and external factors such as the group’s size, task, and access to resources affect a group’s structure. A group’s structure also affects how group members communicate, as some structures are more centralized and hierarchical and other structures are more decentralized and equal.

- Groups are interdependent in that they have a shared purpose and a shared fate, meaning that each group member’s actions affect every other group member.

- Groups develop a shared identity based on their task or purpose, previous accomplishments, future goals, and an identity that sets their members apart from other groups.

Small groups serve several functions as they meet instrumental, interpersonal, and identity needs.

- Groups meet instrumental needs, as they allow us to pool resources and provide access to information to better help us survive and succeed.

- Groups meet interpersonal needs, as they provide a sense of belonging (inclusion), an opportunity to participate in decision making and influence others (control), and emotional support.

- Groups meet identity needs, as they offer us a chance to affiliate ourselves with others whom we perceive to be like us or whom we admire and would like to be associated with.

There are various types of groups, including task-oriented, relational-oriented, primary, and secondary groups, as well as teams.

- Task-oriented groups are formed to solve a problem, promote a cause, or generate ideas or information, while relational-oriented groups are formed to promote interpersonal connections. While there are elements of both in every group, the overall purpose of a group can usually be categorized as primarily task or relational oriented.

- Primary groups are long-lasting groups that are formed based on interpersonal relationships and include family and friendship groups, and secondary groups are characterized by less frequent interaction and less emotional and relational communication than in primary groups. Our communication in primary groups is more frequently other oriented than our communication in secondary groups, which is often self-oriented.

- Teams are similar to task-oriented groups, but they are characterized by a high degree of loyalty and dedication to the group’s task and to other group members.

- Advantages of group communication include shared decision making, shared resources, synergy, and exposure to diversity. Disadvantages of group communication include unnecessary group formation (when the task would be better performed by one person), difficulty coordinating schedules, and difficulty with accountability and social loafing.

- A study group for this class

- A committee to decide on library renovation plans

- An upper-level college class in your major

- A group to advocate for more awareness of and support for abandoned animals

- List some groups to which you have belonged that focused primarily on tasks and then list some that focused primarily on relationships. Compare and contrast your experiences in these groups.

- Synergy is one of the main advantages of small group communication. Explain a time when a group you were in benefited from or failed to achieve synergy. What contributed to your success/failure?

Adler, R. B., and Jeanne Marquardt Elmhorst, Communicating at Work: Principles and Practices for Businesses and the Professions , 8th ed. (Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill, 2005), 248–50.

Ahuja, M. K., and John E. Galvin, “Socialization in Virtual Groups,” Journal of Management 29, no. 2 (2003): 163.

Barker, D. B., “The Behavioral Analysis of Interpersonal Intimacy in Group Development,” Small Group Research 22, no. 1 (1991): 79.

Comer, D. R., “Organizational Newcomers’ Acquisition of Information from Peers,” Management Communication Quarterly 5, no. 1 (1991): 64–89.

Ellis, D. G., and B. Aubrey Fisher, Small Group Decision Making: Communication and the Group Process , 4th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994), 57.

Girl Scouts, “Facts,” accessed July 15, 2012, http://www.girlscouts.org/who_we_are/facts .

Hargie, O., Skilled Interpersonal Interaction: Research, Theory, and Practice , 5th ed. (London: Routledge, 2011), 452–53.

Karau, S. J., and Kipling D. Williams, “Social Loafing: A Meta-Analytic Review and Theoretical Integration,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 65, no. 4 (1993): 681.

Larson, C. E., and Frank M. J. LaFasto, TeamWork: What Must Go Right/What Must Go Wrong (Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1989), 73.

Larson Jr., J. R., In Search of Synergy in Small Group Performance (New York: Psychology Press, 2010).

McKay, M., Martha Davis, and Patrick Fanning, Messages: Communication Skills Book , 2nd ed. (Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, 1995), 254.

Myers, S. A., and Alan K. Goodboy, “A Study of Grouphate in a Course on Small Group Communication,” Psychological Reports 97, no. 2 (2005): 385.

Walther, J. B., and Ulla Bunz, “The Rules of Virtual Groups: Trust, Liking, and Performance in Computer-Mediated Communication,” Journal of Communication 55, no. 4 (2005): 830.

Weimer, M., “Why Students Hate Groups,” The Teaching Professor , July 1, 2008, accessed July 15, 2012, http://www.teachingprofessor.com/articles/teaching-and-learning/why-students-hate-groups .

Communication in the Real World Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

13 Leadership, Roles, and Problem Solving in Groups

Introduction

13.1 Group Member Roles

Task-related roles and behaviors.

Task roles and their related behaviors contribute directly to the group’s completion of a task or achievement of its goal or purpose. Task-related roles typically serve leadership, informational, or procedural functions. In this section, we will discuss the following roles and behaviors: task leader, expediter, information provider, information seeker, gatekeeper, and recorder.

Task Leader

Within any group, there may be a task leader. This person may have a high group status because of his or her maturity, problem-solving abilities, knowledge, and/or leadership experience and skills. This person acts to help the group complete its task (Cragan & Wright, 1991). This person may be a designated or emergent leader, but in either case, task leaders tend to talk more during group interactions than other group members and also tend to do more work in the group. Depending on the number of tasks a group has, there may be more than one task leader, especially if the tasks require different sets of skills or knowledge. Because of the added responsibilities of being a task leader, people in these roles may experience higher levels of stress. A task leader could lessen these stresses, however, through some of the maintenance role behaviors that will be discussed later.

We can divide task-leader behaviors two types: substantive and procedural (Pavitt, 1999). The substantive leader is the “idea person” who communicates “big picture” thoughts and suggestions that feed group discussion. The procedural leader is the person who gives the most guidance, perhaps following up on the ideas generated by the substantive leader. A skilled and experienced task leader may be able to perform both of these roles, but when the roles are filled by two different people, the person considered the procedural leader is more likely than the substantive leader to be viewed by members as the overall group leader. This indicates that task-focused groups assign more status to the person who actually guides the group toward the completion of the task (a “doer”) than the person who comes up with ideas (the “thinker”).

The expediter is a task-related role that functions to keep the group on track toward completing its task by managing the agenda and setting and assessing goals in order to monitor the group’s progress (Burke, Georganta, & Marlow, 2019). An expediter doesn’t push group members mindlessly along toward the completion of their task; an expediter must have a good sense of when a topic has been sufficiently discussed or when a group’s extended focus on one area has led to diminishing returns. In such cases, the expediter may say, “Now that we’ve had a thorough discussion of the pros and cons of switching the office from PCs to Macs, which side do you think has more support?” or “We’ve spent half of this meeting looking for examples of what other libraries have done and haven’t found anything useful. Maybe we should switch gears so we can get something concrete done tonight.”

To avoid the perception that group members are being rushed, a skilled expediter can demonstrate good active-listening skills by paraphrasing what has been discussed and summarizing what has been accomplished in such a way that makes it easier for group members to see the need to move on.

Information Provider

The information provider role includes behaviors that are more evenly shared compared to other roles, as ideally, all group members present new ideas, initiate discussions of new topics, and contribute their own relevant knowledge and experiences Burke, Georganta, & Marlow, 2019). When group members meet, they each possess different types of information. Early group meetings may consist of group members taking turns briefing each other on their area of expertise. In other situations, one group member may be chosen because of his or her specialized knowledge. This person may be the primary information provider for all other group members. For example, one of our colleagues was selected to serve on a university committee reviewing our undergraduate learning goals. Since her official role was to serve as the “faculty expert” on the subcommittee related to speaking, she played a more central information-provider function for the group during most of the initial meetings. Since other people on the subcommittee were not as familiar with speaking and its place within higher education curriculum, it made sense that information-providing behaviors were not as evenly distributed.

Information Seeker

The information seeker asks for more information, elaboration, or clarification on items relevant to the group’s task Burke, Georganta, & Marlow, 2019). The information sought may include facts or group member opinions. In general, information seekers ask questions for clarification, but they can also ask questions that help provide an important evaluative function. Most groups could benefit from more critically oriented information-seeking behaviors. As our discussion of groupthink notes, critical questioning helps increase the quality of ideas and group outcomes and helps avoid groupthink. By asking for more information, people have to defend (in a non-adversarial way) and/or support their claims, which can help ensure that the information is credible, relevant, and thoroughly considered. When information seeking or questioning occurs because of poor listening skills, it risks negatively affecting the group. Skilled information providers and seekers are also good active listeners. They increase all group members’ knowledge when they paraphrase and ask clarifying questions about the information presented.

The gatekeeper manages the flow of conversation in a group in order to achieve an appropriate balance so that all group members get to participate in a meaningful way Burke, Georganta, & Marlow, 2019). The gatekeeper may prompt others to provide information by saying something like “Let’s each share one idea we have for a movie to show during Black History Month.” He or she may also help correct an imbalance between members who have provided much information already and members who have been quiet by saying something like “Aretha, we’ve heard a lot from you today. Let us hear from someone else. Beau, what are your thoughts on Aretha’s suggestion?” Gatekeepers should be cautious about “calling people out” or at least making them feel that way. Instead of scolding someone for not participating, the gatekeeper should be ask a member to contribute something specific instead of just asking if that person has anything to add. Since gatekeepers make group members feel included, they also service the relational aspects of the group.

The recorder takes notes on the discussion and activities that occur during a group meeting. The recorder is the only role that is essentially limited to one person at a time since in most cases it would not be necessary or beneficial to have more than one person recording. At less formal meetings, there may be no recorder, while at formal meetings there is usually a person who records meeting minutes, which are an overview of what occurred at the meeting. Each committee will have different rules or norms regarding the level of detail within and availability of the minutes.

Maintenance Roles and Behaviors

Maintenance roles and their corresponding behaviors function to create and maintain social cohesion and fulfill the interpersonal needs of group members. All these role behaviors require strong and sensitive interpersonal skills. The maintenance roles we will discuss in this section include social-emotional leader, supporter, tension releaser, harmonizer, and interpreter.

Social-Emotional Leader

The social-emotional leader within a group may perform a variety of maintenance roles and is generally someone who is well liked by the other group members and whose role behaviors complement but do not compete with the task leader. The social-emotional leader may also reassure and support the task leader when he or she is stressed (Koch, 2013). In general, the social-emotional leader is a reflective thinker who has good perception skills that he or she uses to analyze the group dynamics and climate and then initiate the appropriate role behaviors to maintain a positive climate. This is not a role that shifts from person to person. While all members of the group perform some maintenance role behaviors at various times, the socioemotional leader reliably functions to support group members and maintain a positive relational climate. Social-emotional leadership functions can actually become detrimental to the group and lead to less satisfaction among members when they view maintenance behaviors as redundant or as too distracting from the task (Pavitt, 1999).

The role of supporter is characterized by communication behaviors that encourage other group members and provide emotional support as needed (Koch, 2013). The supporter’s work primarily occurs in one-on-one exchanges that are more intimate and in-depth than the exchanges that take place during full group meetings. While many group members may make supporting comments publicly at group meetings, these comments are typically superficial and/or brief. A supporter uses active empathetic listening skills to connect with group members who may seem down or frustrated by saying something like “Tayesha, you seemed kind of down today. Is there anything you’d like to talk about?” Supporters also follow up on previous conversations with group members to maintain the connections they have already established by saying things like “Alan, I remember you said your mom is having surgery this weekend. I hope it goes well. Let me know if you need anything.”

Tension Releaser

The tension releaser is someone who is naturally funny and sensitive to the personalities of the group and the dynamics of any given situation and who uses these qualities to manage the frustration level of the group (Koch, 2013). Being funny is not enough to fulfill this role, as jokes or comments could indeed be humorous to other group members but are delivered at an inopportune time, which ultimately creates rather than releases tension. The healthy use of humor by the tension releaser performs the same maintenance function as the empathy employed by the harmonizer or the social-emotional leader, but it is less intimate and is typically directed toward the whole group instead of just one person.

Group members who help manage the various types of group conflict that emerge during group communication plays the harmonizer role (Koch, 2013). They keep their eyes and ears open for signs of conflict among group members and ideally intervene before it escalates. For example, the harmonizer may sense that one group member’s critique of another member’s idea was not received positively, and he or she may be able to rephrase the critique in a more constructive way, which can help diminish the other group member’s defensiveness. Harmonizers also deescalate conflict once it has already started—for example, by suggesting that the group take a break and then mediating between group members in a side conversation.

These actions can help prevent conflict from spilling over into other group interactions. In cases where the whole group experiences conflict, the harmonizer may help lead the group in perception-checking discussions that help members see an issue from multiple perspectives. For a harmonizer to be effective, he or she must be viewed as impartial and committed to the group as a whole rather than to one side, person, or faction within the larger group. A special kind of harmonizer that helps manage cultural differences within the group is the interpreter.

Interpreter

An interpreter helps manage the diversity within a group by mediating intercultural conflict, articulating common ground between different people, and generally creating a climate where difference is seen as an opportunity rather than as something to be feared (Koch, 2013). Just as an interpreter at the United Nations acts as a bridge between two different languages, the interpreter can bridge identity differences between group members. Interpreters can help perform the other maintenance roles discussed with a special awareness of and sensitivity toward cultural differences. Interpreters, because of their cultural sensitivity, may also take a proactive role to help address conflict before it emerges—for example, by taking a group member aside and explaining why his or her behavior or comments may be perceived as offensive.

Negative Roles and Behaviors