- Where to Start?

- Join our Patreon!

- Circle of Fifths Ebook

- Nashville Number System Ebook

- Ebook Bundle

- MTFM YouTube Channel

- Music Alphabet

- Learning Music Theory Scales 3 Ways

- Pentatonics

- Increasing your Metronome SPEED!

- Fine Tuning Using Your Ears

- Intermediate

- Practice Tips

- Number System

- Circle of Fifths

- Basic Chords

- Reading Music

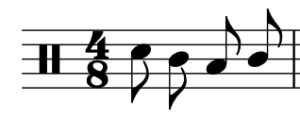

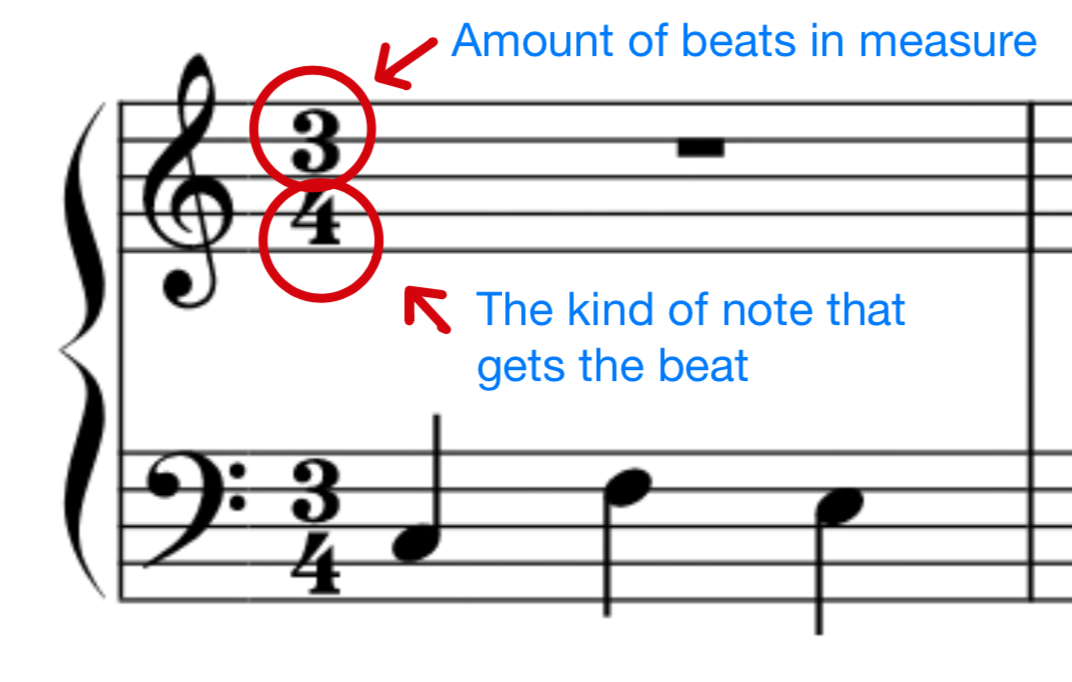

Reading Time Signatures

At the beginning of pieces of music we find the Time Signatures. This tells us the meter. Meter is the rhythmic form or structure to a song. The form is repeated in every measure so you could say that each measure is one cycle of the meter. So if the song is in a meter of 3, then the beats would be counted as 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3... with each new measure starting on 1.

A time signature is made up of 2 parts. The top number designates how many beats there are in each measure and the bottom number designates what kind of note each beat is. We'll start with the top number because it is easier to understand.

If we have a signatre of 3/4, that means that there will be 3 beats per measure. If we have a signature of 4/4, there will be 4 beats per measure. This doesn't mean that there are only 4 notes in the measure, just a total of 4 beats.

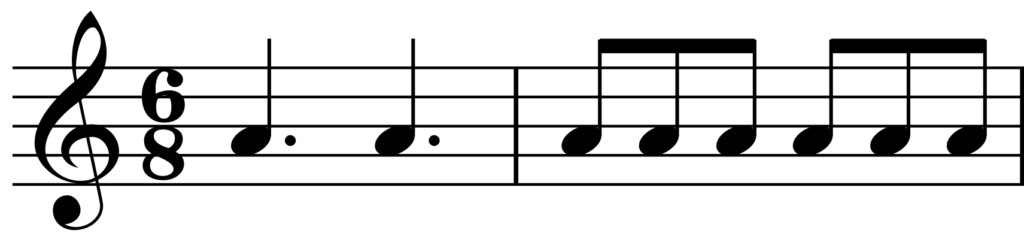

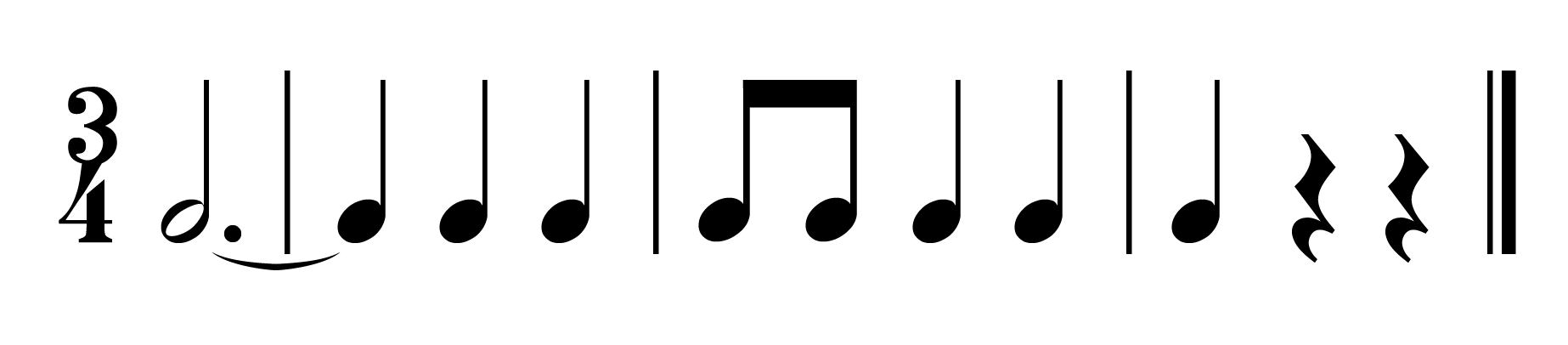

Now for the bottom number. If we have a signature of 3/4 then each beat will be represented as a quarter note. If it is 3/2, then each beat will be represented as half note. Now this doesn't mean that all of the notes in the measure will be half notes. This simply means that all of the notes in the measure have to add up to the total value of 3 half notes. Here are some examples below.

The most used signatures are 2/4, 3/4, 4/4, and 2/2. 4/4 is the most common, so we call it "common time" and it sometimes looks like this:

2/2 is the same thing cut in half so we call it "cut time" and it sometimes looks like this:

The time sigs. we have looked at here are called Basic time sigs. These are the easiest to read and count. When there is an 8 on the bottom, these become complex time signatures, and we will talk about them in a later lesson.

Very Important!

Don't get too worried about these. Some people try to figure out every single one possible and try to understand them intimately. They aren't THAT important. They simply tell you the meter of the song. That is all. They are not some cosmo-magical being that rules the universe of music.

To be quite honest, if you know basically how one works, and you can tell "Okay, there are 3 beats and each beat is a quarter note, so there should be a total value of 3 quarter notes, and the song will have a meter of 1, 2, 3, 1 2, 3," then you can already play music just as well as that guy that knows them to the finest degree.

If in doubt, re-read the title of this website: Music Theory for Musicians, not Theorists. If you want to be a theorist, there are textbooks that can explain more about these, but this should give you enough information to play most music out there.

Return from Reading: Time Signatures to Reading Music Return from Reading: Time Signatures to Homepage

Hope this helps! Practice hard and let me know if you have any questions!

Would you prefer to share this page with others by linking to it?

- Click on the HTML link code below.

- Copy and paste it, adding a note of your own, into your blog, a Web page, forums, a blog comment, your Facebook account, or anywhere that someone would find this page valuable.

Sign up for the newsletter!

Understanding Time Signatures and Meters: A Musical Guide

At the beginning of practically any score of music you have ever looked at there are numbers and symbols that clarify how to interpret the music notation in the score. As a music learner, you’ve become familiar with these symbols and you know that the numbers tell you how to interpret the music’s rhythms, how to count and keep track of the beat, and that if you’re playing with other performers—the numbers help you stay together!

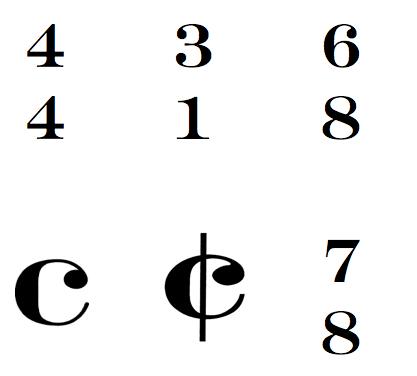

Yet, there are so many numbers and so many ways for these numbers to be written:

These are just some of the time signatures you might encounter. Notice also in the above image that there are time signatures in the form of letters instead of numbers, which adds even more possibilities and potential complications into the mix; however, these letters really just stand in for numbers with added special meanings.

All of these time signatures raise the questions: do we really need all of these different time signatures? Do they really mean different things? Why do composers and musicians prefer some time signatures over others? These time signatures really do have slightly different meanings and purposes in music, but some can sound the same to the ear. Some are quite rare and others are more common.

This article will explain the basics of reading time signatures and meters, show how the various time signatures are related to each other and can sound similar and different, and why composers might choose certain time signatures over others.

Sound in Time

Fundamental to the definition of music itself is that music must move through time—it is not static. Hence, music is sound organized through time. This organization of music through time is managed in the Western music system through time signatures.

The time signatures give us a way to notate our music so that we can play the music from scores, hear its organizational patterns, and discuss it with a common terminology known to other musicians. The organizational patterns of beats, as indicated by the time signature, is how we hear and/or feel the meter of said piece. When discussing music, the terms "time signature" and "meter" are frequently used interchangeably; but time signature refers specifically to the number and types of notes in each measure of music, while meter refers to how those notes are grouped together in the music in a repeated pattern to create a cohesive sounding composition. The methods for classifying the various time signatures into meters is discussed in detail later in this article.

Meters vs. Rhythms

Meter is the comprehensive tool we used to discuss how music moves through time. That said, there is another way that musicians also discuss how music moves through time, and that is through rhythm. Rhythms are the lengths of the notes in the music itself - which notes are long and which notes are short. Musicians learn how to play these rhythms in the context of each piece by using the time signature.

The Notation

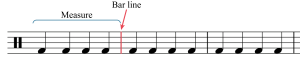

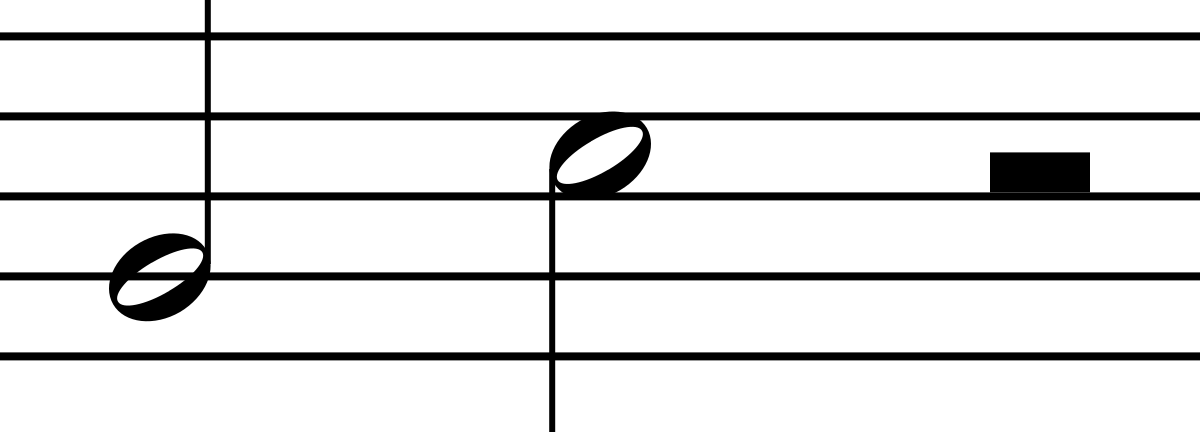

In musical scores, we organize the music into “ bars ” or measures . A “ barline ," or measure line, is where the five horizontal lines of a staff are intersected vertically with another line, indicating a separation:

Each measure has a specific number of notes allowed to be placed in it, and that number of notes is dependent upon the time signature.

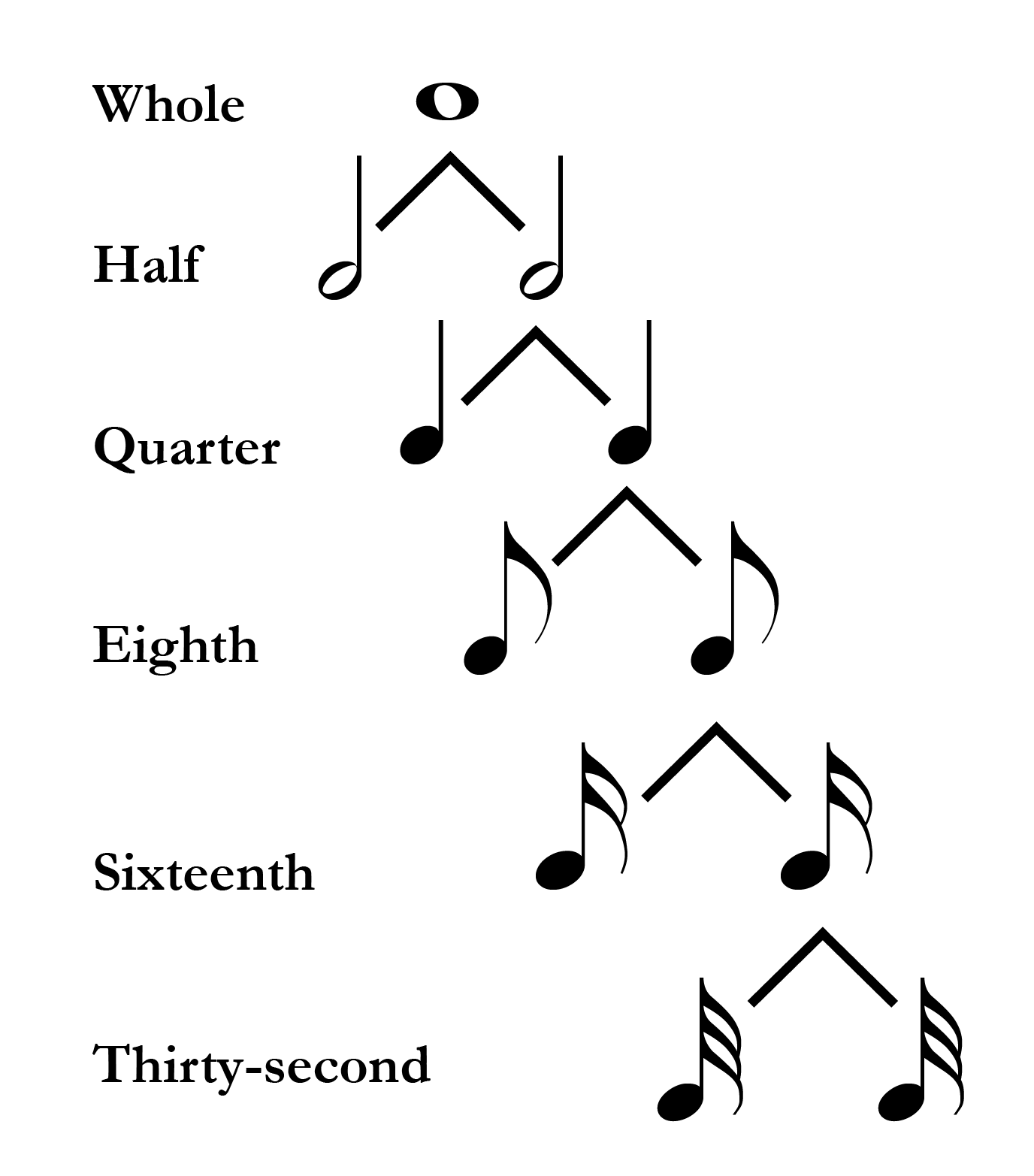

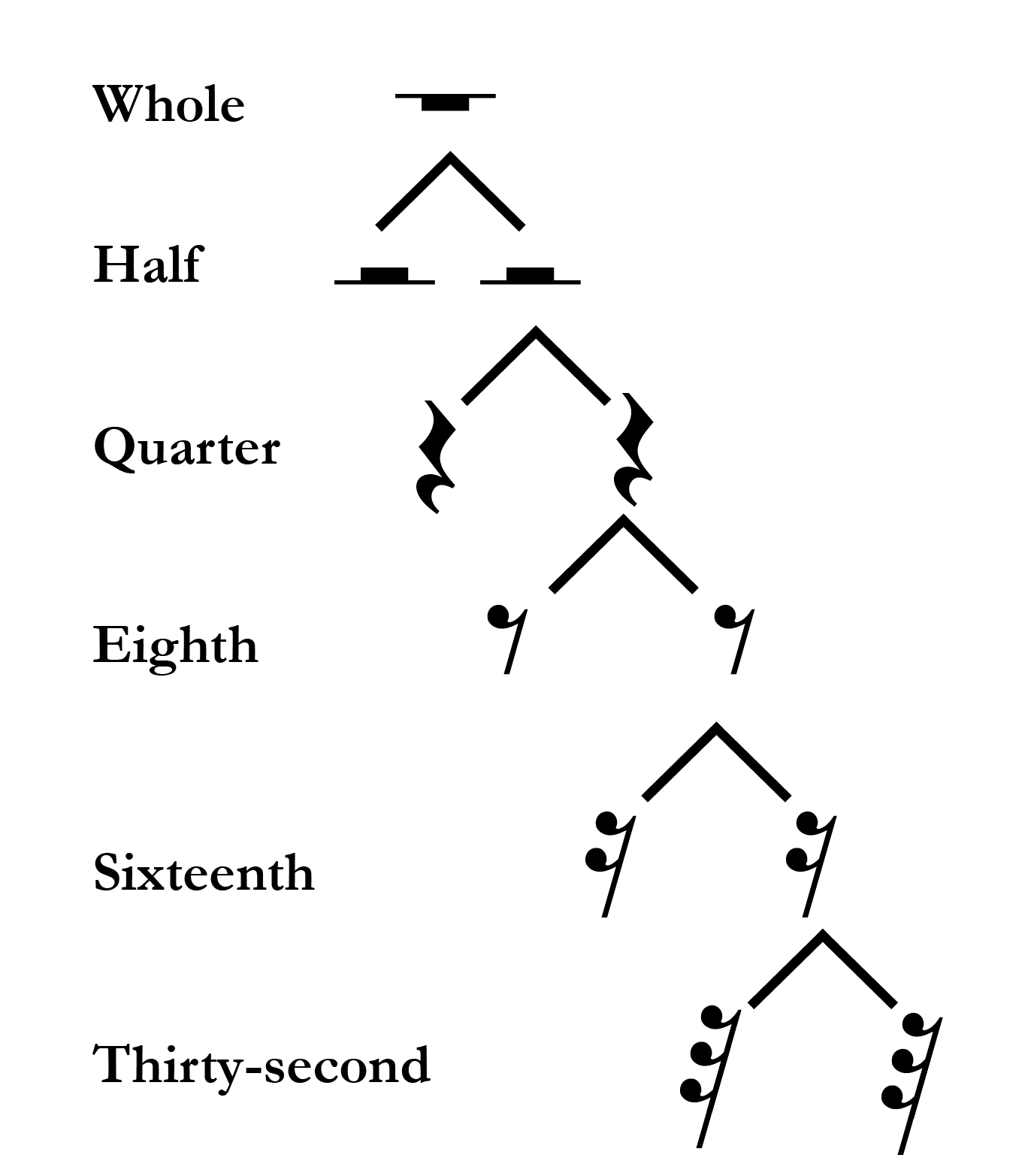

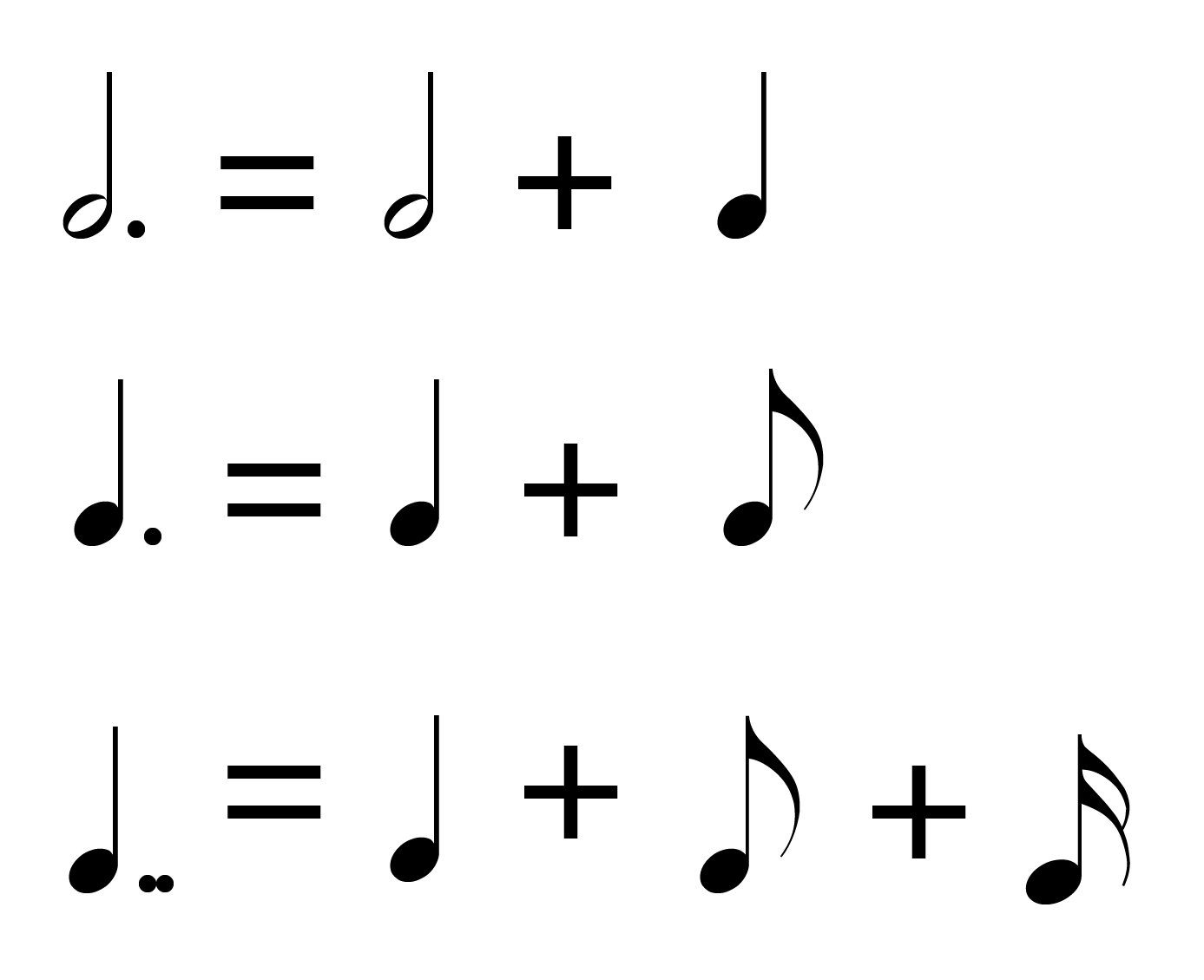

The most common notes which are used to make the short and long rhythms in the various meters are included in the chart below, beginning with the longest held notes and going to the shortest. This chart also mentions the length relationship between the note values.

As the notes in the various metric breakdowns get bigger or smaller, the equivalent relationships continue. For example, a double-whole note would last as long as eight quarter notes!

Reading the Time Signatures

The number of notes allowed in each measure is determined by the time signature . As you saw in the time signature examples above, each time signature has two numbers: a top number and a bottom number: 2/4 time, 3/4 time, 4/4 time, 3/8 time, 9/8 time, 4/2 time, 3/1 time, and so on. The bottom number of the time signature indicates a certain kind of note used to count the beat, and the top note reveals how many beats are in each measure. If you look at the American note names from the chart above, there is a fun little trick to it:

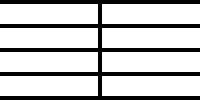

Take the 2/4 time signature for example - with the 2 on the top of the time signature you know there are 2 beats for one measure, and this leaves you with a fraction of 1/4 —a quarter, the note-length the time signature is indicating to you then is a quarter note. Therefore, you know that there are two quarter notes worth of time in every measure:

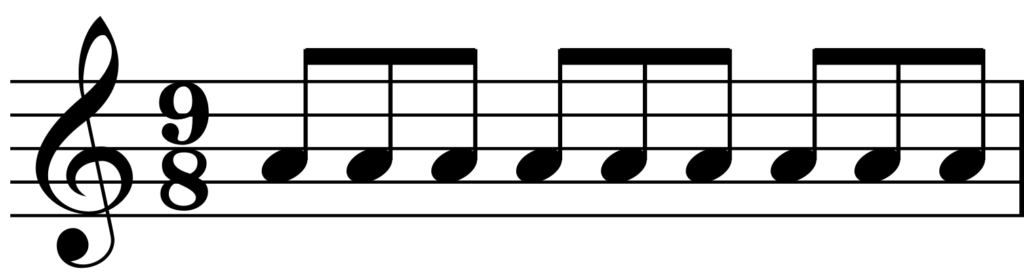

Let’s try another one. In 9/8 time, you know that in every measure there are 9 notes in a 1/8 length.

How about in 4/2 time?

In 4/2 time, each measure has 4 notes of 1/2, so we have 4 1/2 notes:

Now try 3/1 time.

In 3/1 time, so we have 3 notes of a 1/1 length, so 3 whole notes!

Common Time and Cut Time

The above steps are how you figure out the notes and beats of most time signatures, but what about the two time signatures that are letters? As a matter of fact, the two letter time signatures are actually shorthand and variations for the most common numerical time signatures, 4/4 and 2/2.

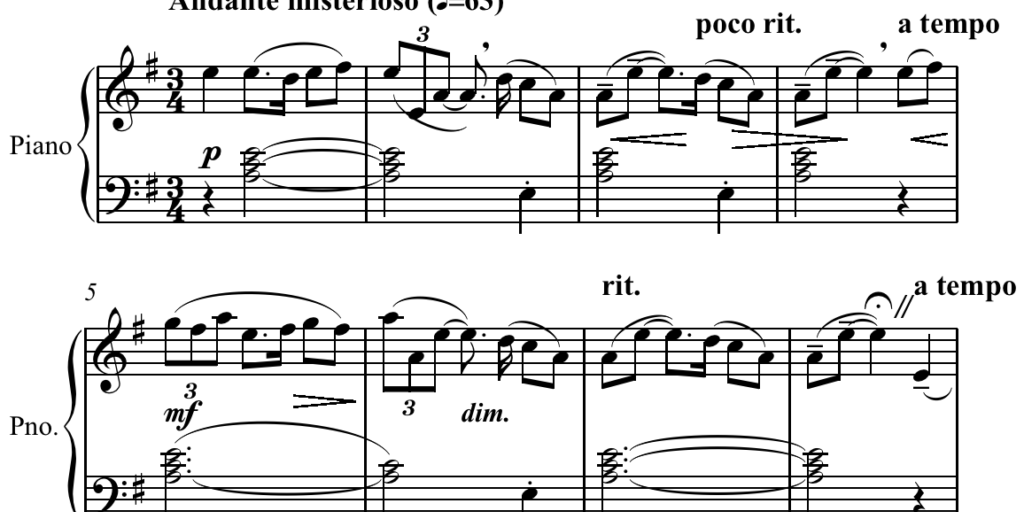

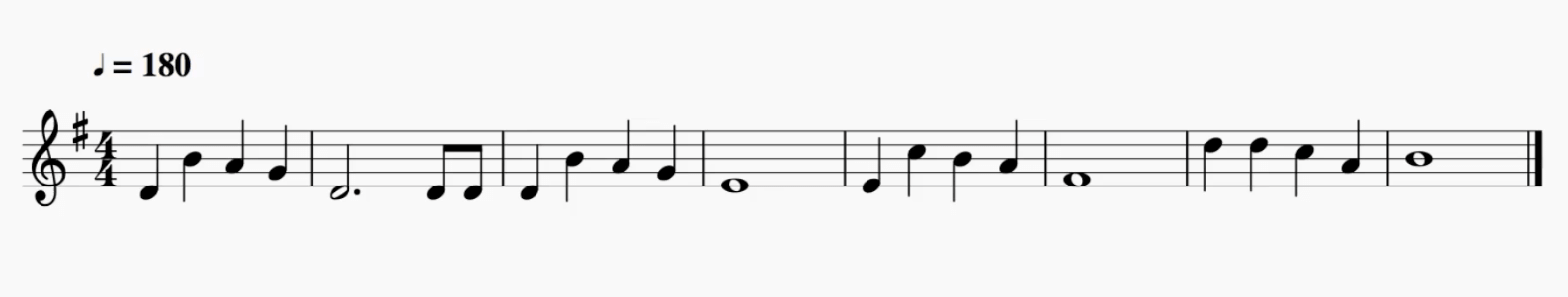

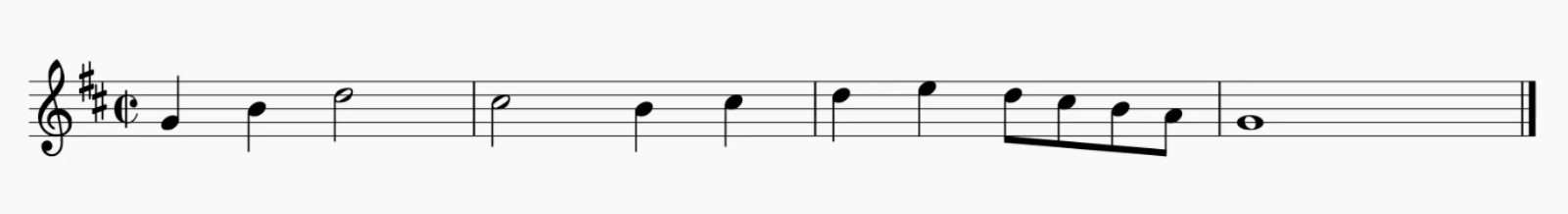

Below is an example from the opening of Edvard Grieg’s Peer Gynt Suite, “In the Hall of the Mountain King.” This excerpt is in marked in Common Time with a big C, which means 4/4. If you count the notes in the measures, you will see that there are four quarter-notes worth of time per measure.

This example is particularly relevant to our discussion of Common and Cut time, because as this piece continues, it gradually increases in speed, moving from sounding like a 4/4 to 2/2. And this is actually what happens! By the end of the piece, the conductor directs the orchestra in Cut Time rather than Common Time. Listen to this performance to hear the beats get faster and see if you can hear when the orchestra switches into Cut Time!

Meter Classifications

We've talking about the basics of reading and deciphering time signatures - now we get to learn how those time signatures can be understood as meters.

There are two levels of classifying meters. The first level of classification focuses on how the beat indicated by the time signature is subdivided.

There are only two ways for the beat to be regularly subdivided in Western music, and that is into two or into three smaller notes. Refer to the note value charts above. All other subdivisions are either multiples of these two subdivisions, or some complex form of adding them together. For ease of notation and classifying the subdivisions as meters then, we have: Simple Time , Compound Time , and Irregular Time .

Simple Time

Simple time is any meter whose basic note division is in groups of two. Examples of these meters include: Common Time, Cut Time, 4/4, 3/4, 2/4, 2/2, 2/1, and so on. These meters are simple time because the quarter note divides equally into two eighth notes, the half-note divides equally into two quarter notes, or the whole note divides equally into two half notes. You can see these divisions if you refer back to the above note length chart.

Compound Time

Slightly more complicated is compound time , which is any meter whose basic note division is into groups of three. You automatically know you are not in simple time if there is an 8 as the bottom number of your time signature. An 8 to mark simple time would be pointless, as will be demonstrated below in the beat hierarchies and accents section.

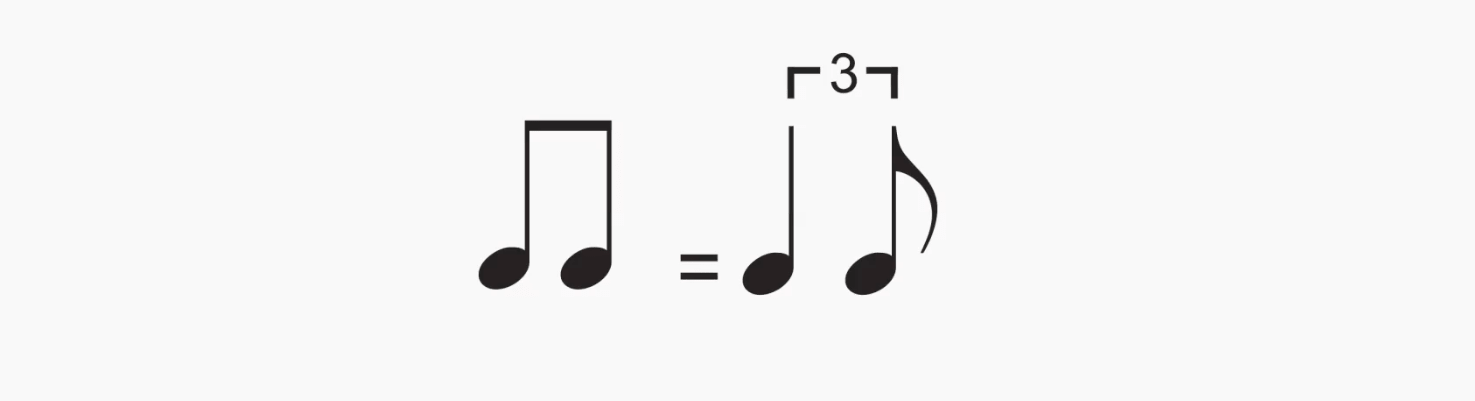

Technically, to get a compound time sound, composers could use a simple time signature and then mark all of the main beat subdivisions in triplets - making a duple division into a triple division - throughout an entire piece to get the same effect. However, using triplets throughout an entire piece to get a compound time sound would appear quite messy and cluttered on the page.

An example of the 12/8 against the 4/4 using triplets is in the table below. To the listener, these examples sound exactly the same, and in practice there is the added risk of confusing performers unused to switching between time signatures.

Even though it's more common to see a simple time signature with the duple divisions in Western music for music of the past five or six centuries, it was actually compound time which developed and was notated first! Because Western music notation developed alongside church music, much of the underlying theory surrounding music had a theological basis. For meter, the most common subdivision was in compound or triple divisions to relate musical time being three in one, similar to the Christian Trinity of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost.

Irregular Time

The final option for beat subdivision is an irregular or unequal subdivision of the beat.

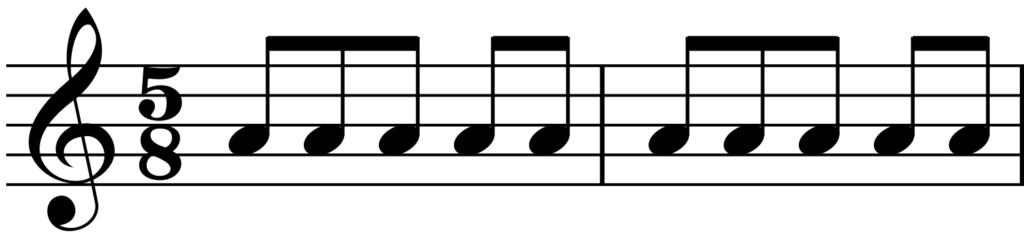

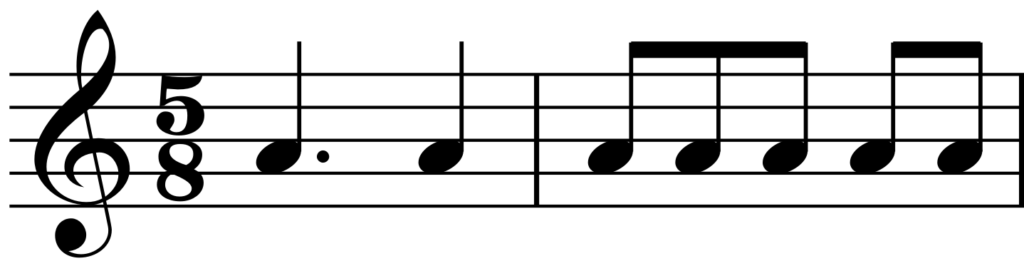

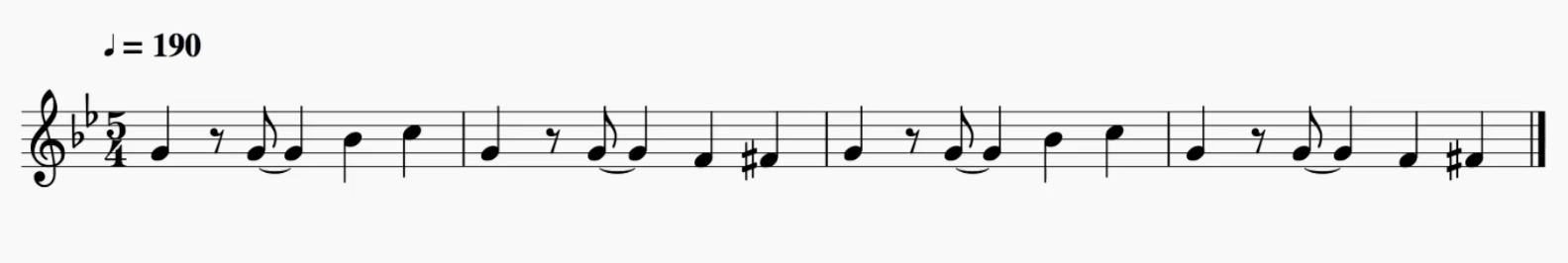

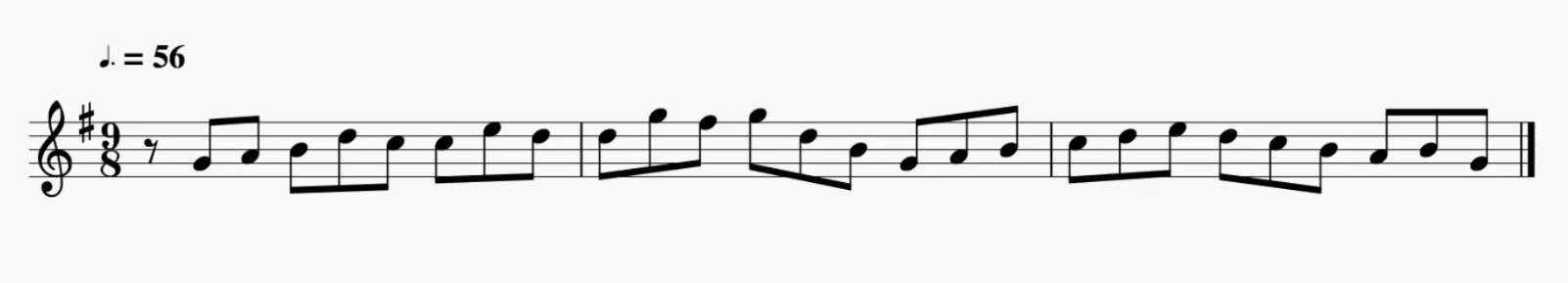

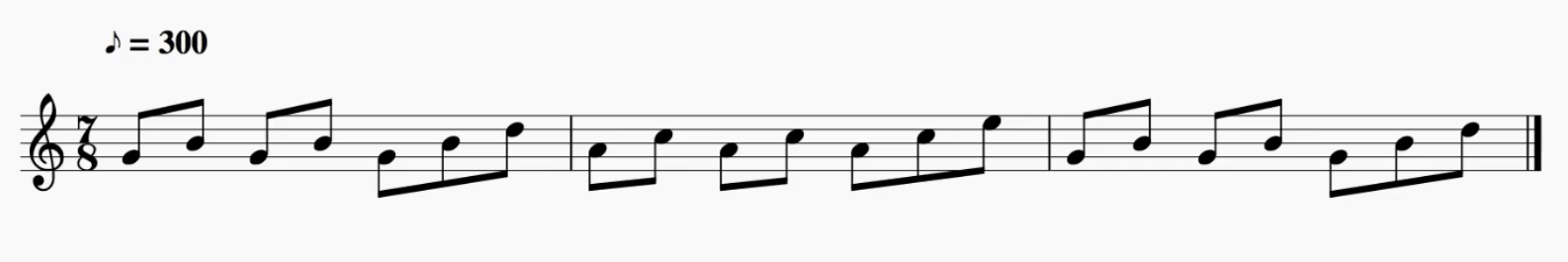

Even though these are “irregular” meters, they do have patterns that are discernable for the performer. The most common irregular meters actually mix simple time and compound time together within a single measure. Thus, in each measure, there are beats with three subdivisions and there are beats with two subdivisions. Examples include such time signatures as 5/8 and 7/8. Because there are 5 eighth notes per measure or 7 eighth notes per measure, you cannot have equal groupings of 2 or 3 eighth notes. Therefore, similarly to 6/8, 9/8, and 12/8, in which the groups of eighth-notes are beamed together to a larger count, in 5/8 and 7/8 they are also beamed together to make a larger count. However, because the number of eighth notes in 5/8 and 7/8 is odd (and prime), the count lengths in each measure are uneven—or irregular. The eighth note typically stays the same length, but because some counts have two and some counts have three eighth notes, they are irregular!

You can see the groupings of three eighth notes with two eighth notes in each measure of 5/8 above, and groups of two eighth notes against two groups of two eighth notes in each measure of 7/8. In 5/8 and 7/8 then, the first count of each measure is one eighth-note longer than the rest of the counts. Depending on where the placement of the longer beat, composers can create different accents and atmospheres.

Russian composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky (1840—1893) uses an irregular meter in the second movement of his Sixth Symphony. When you listen to the movement, it sounds like it should be a waltz with three beats per measure, but the “beats” of the meter are uneven, sometimes the first beat is longer, sometimes it is shorter because the subdivisions are irregular. To the listener, because it sounds like a waltz and like a dance, it feels at once familiar, but then also lopsided and distant. The irregular beat patterns are unexpected and un-danceable (at least without some serious practice and memorization!). The familiar becomes distorted, distant, potentially dangerous and frightening.

Duple, Triple, and Quadruple Classifications

The second level of classification for meters is how many beats there are in a measure. There are three which are the most common: duple (2/2, 2/4, 6/8), triple (3/4, 9/8, 3/2), and quadruple (4/4, 12/8, 4/2). A duple meter has two beats per measure, a triple meter has three beats per measure, and a quadruple meter has four beats per measure. It is rare to see any larger or smaller that are not an equivalent to one of these three.

Cut-Time is duple and simple meter because there are two beats per measure and those beats are divisible by two:

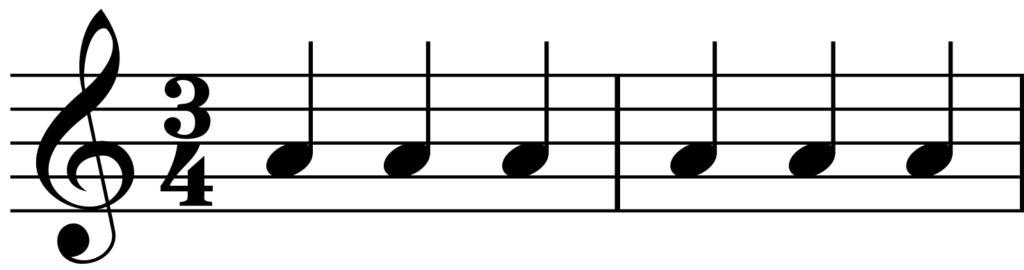

3/4 time is triple and simple meter because there are three beats per measure and each beat is divisible by two:

4/2 is quadruple and simple meter because there are four beats per measure and each beat is divisible by two:

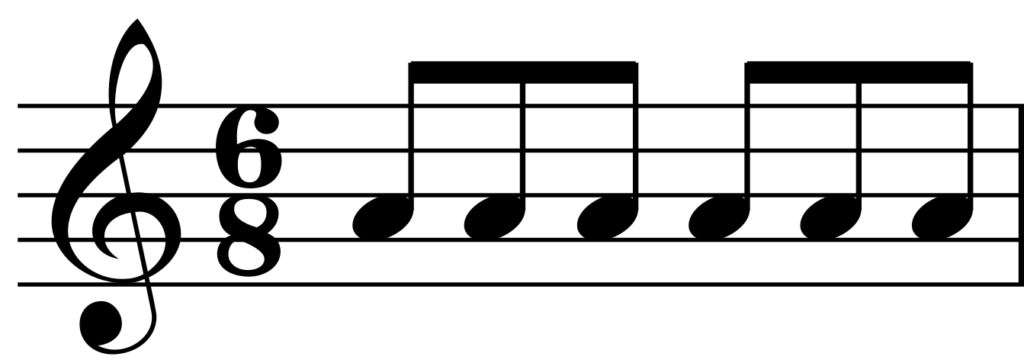

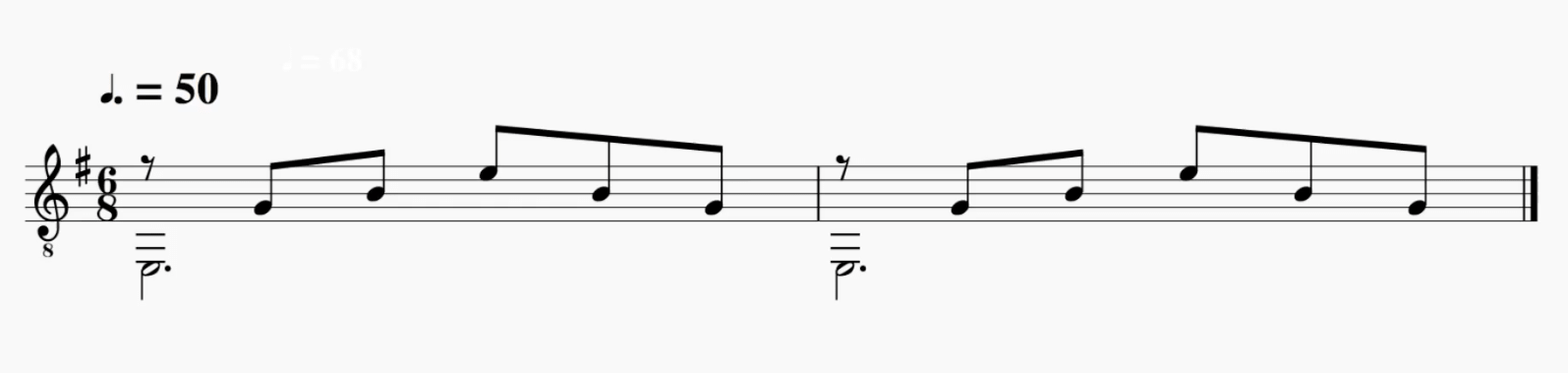

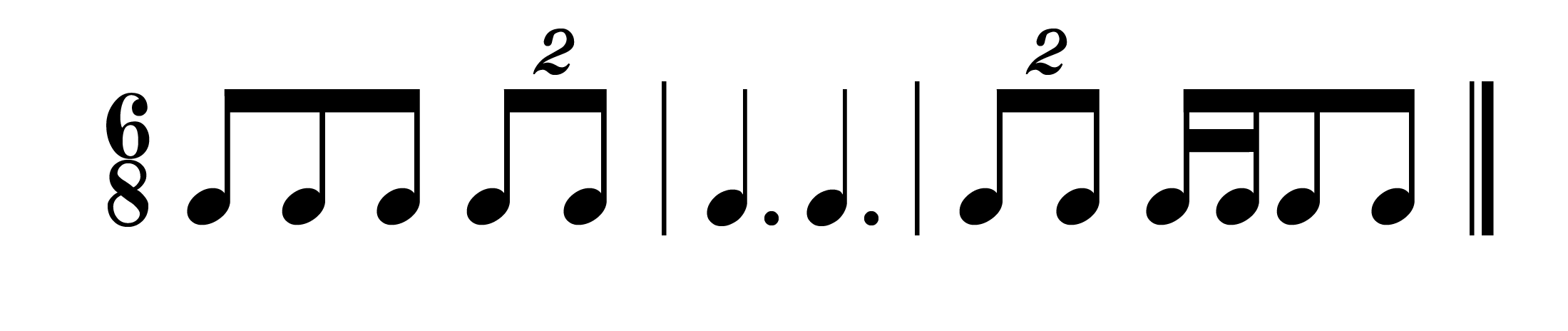

6/8 time is duple and compound meter because there are two beats per measure and each beat is divided into three:

9/8 time is triple and compound meter because there are three beats per measure and each beat is divided into three:

5/8 time is duple and irregular meter because there are two beats per measure and each beat is divided irregularly:

Look through your scores at home: what are some of the meter classifications that you have been playing?

As you can see from the above explanations of the various time signatures and their meters, there are a lot of similarities and subtle nuances between all of these meters. For example, all of the duple and quadruple time meters are similar in that they have two and four beats per measure. This trait makes them sound very similar to the ear.

Depending on the tempo of the piece, triple and simple time pieces can sound compound and some compound pieces (i.e. 6/8) can sound like they have a simple beat subdivision but triple (i.e. the 6/8 sounding like 3/4)! What helps to distinguish a lot of these meters is the beat hierarchies and typical styles of music in which they are employed.

Beat Hierarchies

Music is sound organized through time, and the time signature tells us how to structure that music in time.

Another important piece of information within that time signature is which notes — which beats — are more important and should get accented. This accentuation of beats is known as a “ beat hierarchy .” In almost all Western Classical music, the first beat of every measure is the strongest and most important beat, and should carry the most weight. In duple meters then, the second beat is weak and any subdivisions of the beat are weaker still. In quadruple meters, beat three of the measure is actually stronger than beat two, but not quite as strong as beat one, and beat four should lead into the next downbeat (beat one of the next measure). Triple time starts with a strong beat one, has a weak beat two, and then begins to build on beat three (leading to beat one again).

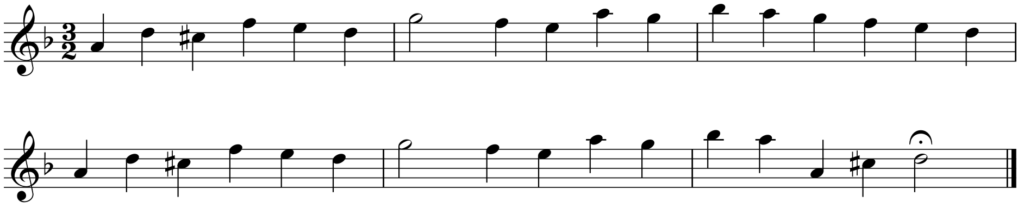

Understanding the beat hierarchies of the different time signatures can help you to interpret repertoire, especially those that use minimal articulation. For example, check out this 3/2 example from the Spirtuoso movement in Telemann’s Fantasia #6 for solo flute:

Because this piece is marked in 3/2 time, it should be in triple and simple time. However, there are no phrase markings and some musicians who have studied Baroque performance practices have argued for sections of this piece being in two instead of three. Switching the meter from a two to three feel is like giving the piece a 6/8 time signature and making the 6/8 eighth note equal to a 3/2 quarter note. With a 6/8 type meter, the Fantasia would be duple and compound, changing the beat hierarchy and accents from every second quarter note to every third quarter note.

The particular Telemann example above, when performed with a changing beat hierarchy, can be an example of a metric and rhythmic technique called hemiola . Hemiola is a two against three subdivision of beats being played against — and right next — to each other.

Syncopation

Another way to disrupt the beat hierarchy of meters in music is to use syncopation . Syncopation is the rhythmic shifting of the accented beat from the traditionally strong beats of one and three. In most cases this is done by a really short note on the downbeat which is immediately followed by an accented long note, or having a tie to an un-articulated downbeat, so that the downbeat gets completely lost. A textbook example of how syncopation can disrupt beat hierarchy can be seen in the ragtime piece “The Entertainer” by Scott Joplin.

From the very first verse, the melody line bounces quickly off the sixteenth-note downbeat onto the accented eighth-note. Then, the next measure’s melody downbeat is tied over from the previous measure. Without the score or the repeated eighth-note chords in the left hand of the piano, you would not know where the downbeats were or be able to track the movement of the measures as easily!

So we have all of these meters and this is how they’re broken down, but… why?

We have all of these different meters and possibilities for subdividing meters to fit the wide variety of music we have! Essentially, different kinds of music require different Simple or Compound time signatures and duple or triple meters. When we connect the music to how it is or was supposed to be used, we find some of the answers to this.

Take a March for example: marches are meant to be, well, marched to, in strict time, and as humans we only have two legs! So out of necessity, marches have to be in a duple or quadruple time. That is why marches are (almost) always in Cut Time, 2/4, 4/4, or on occasion, 6/8. Sousa’s iconic “Stars and Stripes Forever” is in Cut Time . Even though “Stars and Stripes,” and other marches still being composed through today, are rarely still marched to, they are still written in a duple time.

Dance music is another example of music that has to be in a specific meter. Most dances throughout history have had a prescribed number of steps and the music that accompanies the dances must match. For example, waltzes have to be in triple time because they follow a pattern of three steps before repeating the cycle.

The choice of meter and note length provided in the time signature is also a possible indicator of tempo. Generally speaking, one would expect a piece notated in 4/1 to move at a slower tempo than 4/4.

So, that's how you read time signatures! We've investigated how they’re similar and different, how they’re used, and how they can change the music we hear. Many are interchangeable and can sound the same, but have slightly different origins or uses. Meters are how composers organize music through time and communicate that organization to the performers.

For fun, try seeing if you can “play” with any of the meters of your repertoire as if they were in a different meter and tell us about your experiments below!

Learn with LPM

If you are looking to review time signatures, check out our lesson on the Music Theory: How to Read Music course.

About the Author: Michele Aichele

Michele Aichele is a PhD candidate in Musicology from the University of Iowa, with a MA from the University of Oregon and a BA from Whitman College (Washington). Her interests are in the role of women in composing, performing, teaching, and patronage in music. Her love of learning translates easily to her work with Liberty Park Music. Not only does she get to share her passion for great music and learn from the talented Liberty Park Music teachers, she also gets to help educate more people across the globe through Liberty Park Music’s services.

Related Articles

The Importance of Music Theory

Three Step Guide to Master Italian Words in Music Theory

What are Keys and Why Should We Know About Them?

Recommended lessons.

ABRSM Music Theory

Learn Music Theory: How to Read Music

Music Theory 2: Intervals, Scales, Triads, and Harmony

23 thoughts on “understanding time signatures and meters: a musical guide”.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *.

I’m struggling with understanding signatures and some of the jumps that are made or not explained and it’s doing my head in.

Reading the Time Signatures 9/8 Time, Why are the notes suddenly grouped into threes with no explanation of why?

Common time and cut time. I get common time (or at least I think I do) but I don’t really understand the explanation of cut time. You say “Technically, these measures have four quarter notes in them as well … This “Cut Time” change to “Common Time” means it goes twice as fast, so instead of the quarter note getting the beat, the half note gets the beat!” What half note? If its twice as fast won’t they be 1/8 notes?

In the score for the Peer Gynt Suite why are there 1/8 notes went time is 4/4. Are you allowed to have notes of different duration to the one identified in the bottom of the signature? How does that work? Why are they grouped as 4 x 1/8 and then 2 x 1/8. Whats the rule an why is this done.

Dear Steve, Thank you for reaching out to us with your questions!

As explained later in the article, the eighth notes are grouped in threes instead of twos because 9/8 is a compound time signature. In compound time, each individual beat gets divided into three notes rather than two. The 9/8 eighth notes are grouped in threes to show that all three notes belong to the same beat. In simple time, which includes time signatures like common time and 2/4, the beat is divided into two notes and are thus the eighth notes are grouped in twos and fours in the other examples.

In cut-time, if the eighth note were to get the beat instead of the quarter note, then the music would move twice as slow, as in, you would double the number of beats in each measure—making it twice as long to get through. The rhythms stay the same in proportion to each other, but they go twice as fast. To go twice as fast as the quarter note beat, you would need a beat that fits two quarter notes in length, and that note, based on the diagram in the article, is a half note.

Regarding the Peer Gynt Suite questions, you are allowed to have notes of different duration to the one identified in the bottom of the time signature. The number at the bottom of the time signature simply tells what type of note gets the beat so that the musician knows how to interpret the rhythms of the notes. If you could only have the note-lengths that are indicated by the bottom of the time signature, then there would be no difference in rhythms—no long notes, no short notes, all the notes would have the same duration in every piece.

The eighth notes of the Peer Gynt Suite are grouped in 4 and then 2 because of the time signature. The 4 and 2 groupings reinforce that this time signature is a simple time signature and when you have a series of eighth notes then, you can only group them in groups of four or two. If they were grouped as a group of 6, that would indicate compound time and a different subdivision of the beat. Because we’re going to be going into cut-time with this example, the composer or publisher of the piece grouped the eighth notes to show the emphasis on two “beats” per measure rather than the common time four beats. That is why the first four eighth notes are grouped together—the four eighth notes equal the same length as one half note, which is one beat in cut time. The next two eighth notes are grouped together because they are on the next beat of the measure, but as they are eighth notes, they cannot be barred with the quarter note that follows. And these two eighth notes and the quarter note make up the second beat of the measure.

How do you conduct 1/4 time, I have theory work sheet and am having a hard time understanding how I would draw that.

Hey Laura, it depends on the piece. A good way to start conducting 1/4 would be to try in one beat per measure.

Hi Michele,

How do we distinguish between 3/2 and 6/4?

Thanks for your question Jithin, The main difference between 3/2 and 6/4 is how you count it. Both time signatures have the same number of quarter notes per measure. In 6/4 you count 6 beats, one for every quarter note. In 3/2 you count 3 beats, one for every half-note.

Many swing band arrangements use the cut time time signature. However, we count off 1,2,1,2,3,4 and play the music as if the time signature was originally in common time or in 4,4. Why is that? The usual answer is “That’s the way it’s always been done.” It’s not a satisfying answer. Any thoughts?

[Response from our drum kit teacher Brendan Bache] This is a really good point. For me cut time, just like common time, is still 4/4. The only difference is the way the beats are felt with the stress on 1 and 3 as opposed to every quarter note pulse. This is often down to the tempo of the piece and when I see cut time in a swing or Latin chart I usually interpret it as 4/4 at a fast tempo. In short, I’ve always counted it that way, (unless the tempo is so fast that it makes no sense to count quarter notes out loud) partly because that’s what I’ve heard other musicians do but also because I think it makes musical sense. Thanks for the comment!

thanks for the information

This was a very clear explanation of time signatures. Thank you.

I am naive about music history, and I have a very limited understanding of music theory, but I’ve often wondered how the time signature symbols evolved the way that they did. It seems to me that we have 2 symbols that represent 3 variables (length per base note, base notes per beat, and beats per measure). The 2 symbols provide a compact notation, but is can be more confusing to people who are new to music signatures.

Over the years, has anyone considered time signatures that make all three variables explicit and which have accommodations for uneven time signatures? I was thinking of something like the following:

4/4 time: 4(4𝅘𝅥) 3/4 time: 3(4𝅘𝅥) 6/8 time: 2(3𝅘𝅥𝅮) 9/8 time: 3(3𝅘𝅥𝅮) 5/8 time: 1(3𝅘𝅥𝅮,2𝅘𝅥𝅮) 7/8 time: 1(3𝅘𝅥𝅮,2𝅘𝅥𝅮,2𝅘𝅥𝅮)

Greetings Dennis and thank you for your question! In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, a lot of composers and theorists have come up with more explicit (and less explicit) time signatures to use in their scores. However, each of these is unique to the composer; there is no universal agreement on anything that works better than the current system. Most of the music musicians learn to play use the time signatures explained in the article.

Oops, it should be more like this (I won’t give up my day job):

4/4 time: 4(1𝅘𝅥) or 4(𝅘𝅥) or (𝅘𝅥,𝅘𝅥,𝅘𝅥,𝅘𝅥) 3/4 time: 3(1𝅘𝅥) or 3(𝅘𝅥) or (𝅘𝅥,𝅘𝅥,𝅘𝅥) 6/8 time: 2(3𝅘𝅥𝅮) or (3𝅘𝅥𝅮,3𝅘𝅥𝅮) 9/8 time: 3(3𝅘𝅥𝅮) or (3𝅘𝅥𝅮,3𝅘𝅥𝅮,3𝅘𝅥𝅮) 5/8 time: (3𝅘𝅥𝅮,2𝅘𝅥𝅮) 7/8 time: (3𝅘𝅥𝅮,2𝅘𝅥𝅮,2𝅘𝅥𝅮)

Prior to the 16th century, and the introduction of bar lines, what was the Latin term for the measurement of the length of a beat?

Thanks for your question Lyle! I frequently see the beat of pre-16th century music referred to as the “tactus.”

I understand there are no constraints as to what tempo certain meters in a musical piece can be played (if composer decides two measures of 4/4 be played at 120bpm and next 3 measures of 4/4 at 140bpm),but how do we calculate a new tempo to have a different meter “sound/feel” the same. For example we start with 7/8 (has 3 beats, 7 8th notes) at 130bpm moving into 4/4 (4 beats, eight 8ths for the purpose of common denominator) how to get the tempo for 4/4 part? Should we look at beats ratio 3 to 4 or notes ratio 7 to 8? I’ve seen a formula like this but don’t know if it’s right, new tempo=number of notes in new tempo X old tempo / num of notes in old tempo. So in our case 8×130/7=114bpm rounded up

Hi Arek, I’m not sure quite what you’re asking. It depends on if the composer wants the overall beat to stay the same or keep the length of the eighth-notes or quarter-notes the same. If the beat stays the same, then moving from 4/4 to 6/8 would mean that instead of dividing each beat into two, you would divide it into three, so the subdivisions get faster, but the length of the beat would stay exactly the same. The same would go for 7/8. I imagine your formula would work if the composer wanted the eighth-notes to stay the same.

Hey Steve. Very insightful article. I understand that 2/4 as a simple quadruple time has a different feel from 6/8. I also know that 6/8 can be re-written as 2/4 without the song losing its feel. Does it mean that the aural feel of 2/4 time signature is always the same as 6/8?

Thanks for your question Jones! No, the aural feel of a 6/8 time signature will not always feel the same as 2/4. It can depend on the tempo. Sometimes it will feel the same, but sometimes, the 6/8 can be stretched out, for example, in some Baroque dance suites.

Wow.. I am indeed blessed with alot of techniques and knowledge on time or measure signature here. Thanks to libertyparkmisic

Michele, Thanks for the most comprehensive and clear explanation of the time signatures I have ever read, and I think I’ve read all of them. I think I get it now. As a nubie bass player, getting time and emphasis under control is one of my biggest challenges. This is exasperated by picking Money by Pink Floyd as a piece to show off to my mates. During this bass line the time switches from 7/4 to 3/4 to 5/4 to 3/4 back to 7/4 and, just for irony I suspect, ends in 4/4 for a couple of bars. It’s a beautiful mess. (Yes, various recording have whole ‘bridge?’ sections in 4/4 included, I know) I learned to play it by listening to the recordings, but now that I have read your article, I can follow the score, and tell my guitar playing mates that ‘I KNOW how it goes’. Thanks for your great work.

Thanks, makes bit more sense now

It will be tomorrow… actually today now, before my subconscious parses this and returns a verdict. My misinterpretation that bars or measures were finite and restricted has been delightfully dismantled. As a singer-songwriter who breathes music I never paid attention to the signature of my breathing. Now, confronting a world of DAW, I need the software to understand my timing, so it can follow and respond well. Today, I learned what a hole, half, quarter and eighth note looks like. As I reverse engineer my fifty+ creations, perhaps soon theory and music will meet and play nice together, so I can record and perform with more weapons in my arsenal. But in three minutes it will be 2am and my brain is full. Thank you

how tempo marking note value is found in irregular meters? ones like 5/4 and 7/8.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Faculty Library

- Piano Patterns

- The Choral Musician

- The General Musician

- Free Courses

- Out in the Field with MLT

- Tunes for Teaching

- Student Library

- Parents Start Here

Rhythm Reading 101: Fundamentals

- Duple, Macrobeats and Microbeats

Rhythm Cells and Rhythm Patterns in 2/4

Watch the video lesson below. The essential content appears below the lesson.

Take a moment to review macrobeats and microbeats in duple meter in the pre-requisites module. Remember: we are learning to read familiar material.

Syllable Review

Say the following to yourself: “Macrobeats in duple meter are DU DU DU DU.” “Microbeats in duple meter are DU DE, DU DE, DU DE, DU DE.”

Time Signature

The stacked numbers circled in the picture above are called a time signature . It tells you what to audiate rhythmically.Technically, it’s a mathematical representation of how much of a whole note is in a measure. However, that theoretical knowledge is not important when first learning how to read. (When you first learned to read the word “cat,” did you need to know it was a noun??) To guide you when you are first learning to read, I will simply tell you what each time signature is telling you to audiate.

Reading Macrobeats and Microbeats in 2/4

The time signature 2/4 usually tells us that the macrobeats (DU) will be represented by a quarter note, and that microbeats (DU DE) will be represented by paired eighth notes.

Rhythm Cells

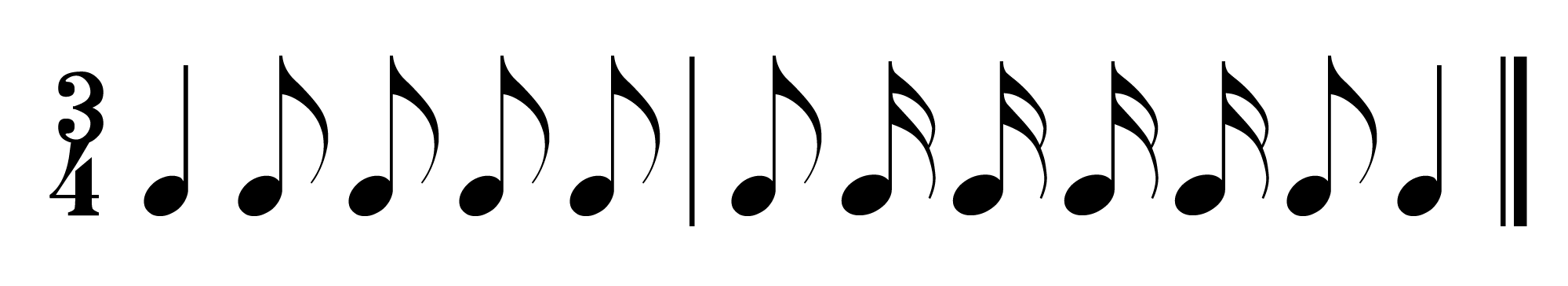

Let’s look at the possible combinations of macrobeats and microbeats in duple meter. There are only four possible combinations. These are called rhythm cells . You might think of these as musical words. Chant each of these rhythm cells several times.

Reading Familiar Patterns

Now we will combine these rhythm cells into four-macrobeat rhythm patterns. You might think of these as very simple musical sentences . These eight rhythm patterns will be part of your musical vocabulary.

Read the above patterns using rhythm syllables (DU and DU DE). Read them both in their familiar and unfamiliar orders. Try varying the tempo. For optimal results, use the video in the next lesson. As you are reading these patterns, continue to move as you read. Move your heels to the macrobeats and gently tap the microbeats on your lap with “spider fingers.”

Feel the thrill of Australia at Stay Casino ! Spin, win, and grin with top slots and games. Your adventure starts here!

Ready for unbeatable fun? Unique Casino offers Aussies the ultimate gaming adventure. Join the action today!

Dive into the heart of Australia with Slots Capital Casino! Enjoy a world-class gaming experience at Slots Capital . Spin and win today!

Hop into big wins at Casino Mate , where Australia's finest casino games await! Start your thrilling journey now!

Aussie players, your quest for the ultimate jackpot begins at bitstarz casino . Are you in?

Feeling lucky, mate? Winport Casino brings the thrill of Vegas to Australia. Bet, win, celebrate!

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

POSTLUDE: An Introduction to Music Theory (Fundamentals)

27 Simple Meter and Time Signatures

Chelsey Hamm; Kris Shaffer; and Mark Gotham

Key Takeaways

- A beat is a pulse in music that regularly recurs.

- Simple meters are meters in which the beat divides into two, and then further subdivides into four.

- Duple meters have groupings of two beats, triple meters have groupings of three beats, and quadruple meters have groupings of four beats.

- There are different conducting patterns for duple, triple, and quadruple meters.

- A measure is equivalent to one group of beats (duple, triple, or quadruple). Measures are separated by bar lines.

- Time signatures in simple meters express two things: how many beats are contained in each measure (the top number), and the beat unit (the bottom number), which refers to the note value that is the beat.

- A beam visually connects notes together, grouping them by beat. Beaming changes in different time signatures.

- Notes below the middle line on a staff are up-stemmed, while notes above the middle line on a staff are down-stemmed. Flag direction works similarly.

Chapter Playlist

In Rhythmic and Rest Values , we discussed the different rhythmic values of notes and rests. Musicians organize rhythmic values into various meters, which are—broadly speaking—formed as the result of recurrent patterns of accents in musical performances.

Terminology

Listen to the following performance by the contemporary musical group Postmodern Jukebox ( Example 1 ). They are performing a cover of the song “Wannabe” by the Spice Girls (originally released in 1996). Beginning at 0:11, it is easy to tap or clap along to this recording. What you are tapping along to is called a beat—a pulse in music that regularly recurs.

Example 1. A cover of “Wannabe” performed by Postmodern Jukebox; listen starting at 0:11.

Example 1 is in a simple meter: a meter in which the beat divides into two, and then further subdivides into four. You can feel this yourself by tapping your beat twice as fast; you might also think of this as dividing your beat into two smaller beats.

Different numbers of beats group into different meters. Duple meters contain beats that are grouped into twos, while Triple meters contain beats that are grouped into threes, and Quadruple meters contain beats that are grouped into fours.

Listening to Simple Meters

Let’s listen to examples of simple duple, simple triple, and simple quadruple meters. A simple duple meter contains two beats, each of which divides into two (and further subdivides into four). “The Stars and Stripes Forever” (1896), written by John Philip Sousa, is in a simple duple meter.

Listen to Example 2 , and tap along, feeling how the beats group into sets of two:

Example 2. “The Stars and Stripes Forever” played by the Dallas Winds.

A simple triple meter contains three beats, each of which divides into two (and further subdivides into four). Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s “Minuet in F major,” K.2 (1774) is in a simple triple meter. Listen to Example 3 , and tap along, feeling how the beats group into sets of three:

Example 3. Mozart’s “Minuet in F major,” played by Alan Huckleberry.

Finally, a simple quadruple meter contains four beats, each of which divides into two (and further subdivides into four). The song “Cake” (2017) by Flo Rida is in a simple quadruple meter. Listen to Example 4 starting at 0:45 and tap along, feeling how the beats group into sets of four:

Example 4. “Cake” by Flo Rida; listen starting at 0:45.

As you can hear and feel (by tapping along), musical compositions in a wide variety of styles are governed by meter. You might practice identifying the meters of some of your favorite songs or musical compositions as simple duple, simple triple, or simple quadruple; listening carefully and tapping along is the best way to do this. Note that simple quadruple meters feel similar to simple duple meters, since four beats can be divided into two groups of two beats. It may not always be immediately apparent if a work is in a simple duple or simple quadruple meter by listening alone.

Conducting Patterns

If you have ever sung in a choir or played an instrument in a band or orchestra, then you have likely had experience with a conductor. Conductors have many jobs. One of these jobs is to provide conducting patterns for the musicians in their choir, band, or orchestra. Conducting patterns serve two main purposes: first, they establish a tempo, and second, they establish a meter.

The three most common conducting patterns outline duple, triple, and quadruple meters. Duple meters are conducted with a downward/outward motion (step 1), followed by an upward motion (step 2), as seen in Example 5 . Triple meters are conducted with a downward motion (step 1), an outward motion (step 2), and an upward motion (step 3), as seen in Example 6 . Quadruple meters are conducted with a downward motion (step 1), an inward motion (step 2), an outward motion (step 3), and an upward motion (step 4), as seen in Example 7 :

Beat 1 of each of these measures is considered a downbeat . A downbeat is conducted with a downward motion, and you may hear and feel that it has more “weight” or “heaviness” then the other beats. An upbeat is the last beat of any measure. Upbeats are conducted with an upward motion, and you may feel and hear that they are anticipatory in nature.

Example 8 shows a short video demonstrating these three conducting patterns:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EEQezQNVldo

Example 8. Dr. John Lopez (Texas A&M University, Kingsville) demonstrates duple, triple, and quadruple conducting patterns.

You can practice these conducting patterns while listening to Example 2 (duple), Example 3 (triple), and Example 4 (quadruple) above.

Time Signatures

In Western musical notation, beat groupings (duple, triple, quadruple, etc.) are shown using bar lines, which separate music into measures (also called bars), as shown in Example 9 . Each measure is equivalent to one beat grouping.

In simple meters, time signatures (also called meter signatures) express two things: 1) how many beats are contained in each measure, and 2) the beat unit (which note value gets the beat). Time signatures are expressed by two numbers, one above the other, placed after the clef ( Example 10 ).

A time signature is not a fraction, though it may look like one; note that there is no line between the two numbers. In simple meters, the top number of a time signature represents the number of beats in each measure, while the bottom number represents the beat unit.

In simple meters, the top number is always 2, 3, or 4, corresponding to duple, triple, or quadruple beat patterns. The bottom number is usually one of the following:

- 2, which means the half note gets the beat.

- 4, which means the quarter note gets the beat.

- 8, which means the eighth note gets the beat.

You may also see the bottom number 16 (the sixteenth note gets the beat) or 1 (the whole note gets the beat) in simple meter time signatures.

Counting in Simple Meter

Counting rhythms aloud is important for musical performance; as a singer or instrumentalist, you must be able to perform rhythms that are written in Western musical notation. Conducting while counting rhythms is highly recommended and will help you to keep a steady tempo. Please note that your instructor may employ a different counting system. Open Music Theory privileges American traditional counting, but this is not the only method.

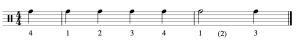

- In each measure, each quarter note gets a count, expressed with Arabic numerals—”1, 2, 3, 4.”

- When notes last longer than one beat (such as a half or whole note in this example), the count is held over multiple beats. Beats that are not counted out loud are written in parentheses.

- When the beat in a simple meter is divided into two, the divisions are counted aloud with the syllable “and,” which is usually notated with the plus sign (+). So, if the quarter note gets the beat, the second eighth note in each beat would be counted as “and.”

- Further subdivisions at the sixteenth-note level are counted as “e” (pronounced as a long vowel, as in the word “see”) and “a” (pronounced “uh”). At the thirty-second-note level, further subdivisions add the syllable “ta” in between each of the previous syllables.

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/6293132/embed

Example 11. Rhythm in 4/4 time.

Simple duple meters have only two beats and simple triple meters have only three, but the subdivisions are counted the same way ( Example 12 ).

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/6296048/embed Example 12. Simple duple meters have two beats per measure; simple triple meters have three.

Like with notes that last for two or more beats, beats that are not articulated because of rests, ties, and dots are also not counted out loud. These beats are usually written in parentheses, as shown in Example 13 :

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/6296065/embed Example 13. Beats that are not counted out loud are put in parentheses.

When an example begins with a pickup note (anacrusis), your count will not begin on “1,” as shown in Example 14 . An anacrusis is counted as the last note(s) of an imaginary measure. When a work begins with an anacrusis, the last measure is usually shortened by the length of the anacrusis. This is demonstrated in Example 14 : the anacrusis is one quarter note in length, so the last measure is only three beats long (i.e., it is missing one quarter note).

Counting with Beat Units of 2, 8, and 16

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/8422379/embed Example 15. The same counted rhythm, as written in a meter with (a) a quarter-note beat, (b) a half-note beat, (c) an eighth-note beat, and (d) a sixteenth-note beat.

Beaming, Stems, Flags, and Multi-Measure Rests

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/6296072/embed Example 16. Beaming in two different meters.

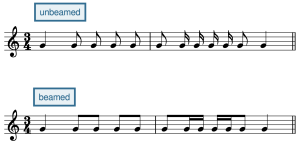

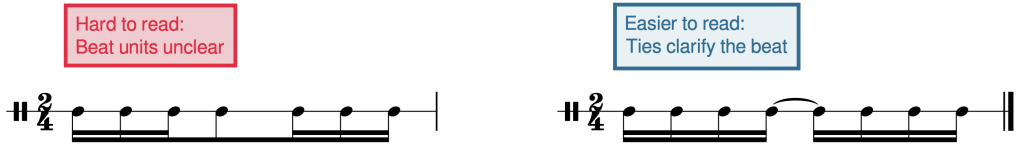

Note that in vocal music, beaming is sometimes only used to connect notes sung on the same syllable. If you are accustomed to music without beaming, you may need to pay special attention to beaming conventions until you have mastered them. In the top staff of Example 17 , the eighth notes are not grouped with beams, making it difficult to see where beats 2 and 3 in the triple meter begin. The bottom staff shows that if we re-notate the rhythm so that the notes that fall within the same beat are grouped together with a beam, it makes the music much easier to read. Note that these two rhythms sound the same, even though they are beamed differently. The ability to group events according to a hierarchy is an important part of human perception, which is why beaming helps us visually parse notated musical rhythms—the metrical structure provides a hierarchy that we show using notational tools like beaming.

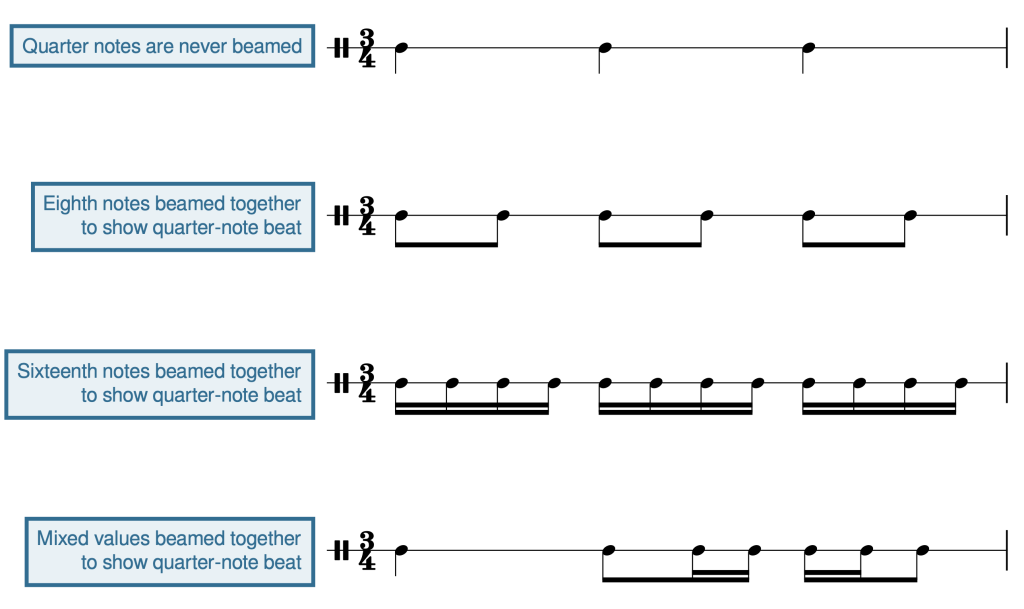

Example 18 shows several different note values beamed together to show the beat unit. The first line does not require beams because quarter notes are never beamed, but all subsequent lines do need beams to clarify beats.

The second measure of Example 19 shows that when notes are grouped together with beams, the stem direction is determined by the note farthest from the middle line. On beat 1 of measure 2, this note is E 5 , which is above the middle line, so down-stems are used. Beat 2 uses up-stems because the note farthest from the middle line is the E 4 below it.

Flagging is determined by stem direction ( Example 20 ). Notes above the middle line receive a down-stem (on the left) and an inward-facing flag (facing right). Notes below the middle line receive an up-stem (on the right) and an outward-facing flag (facing left). Notes on the middle line can be flagged in either direction, usually depending on the contour of the musical line.

Partial beams can be used for mixed rhythmic groupings, as shown in Example 21 . Sometimes these beaming conventions look strange to students who have had less experience with reading beamed music. If this is the case, you will want to pay special attention to how the notes in Example 21 are beamed.

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/8422418/embed

Example 21. Partial beams are used for some mixed rhythmic groupings.

Rests that last for multiple full measures are sometimes notated as seen in Example 22 . This example indicates that the musician is to rest for a duration of four full measures.

A Note on Ties

We have already encountered ties that can be used to extend a note over a measure line. But ties can also be used like beams to clarify the metrical structure within a measure. In the first measure of Example 23 , beat 2 begins in the middle of the eighth note, making it difficult to see the metrical structure. Breaking the eighth note into two sixteenth notes connected by a tie, as shown in the second measure, clearly shows the beginning of beat 2.

- Simple Meter Tutorial (musictheory.net)

- Video Tutorial on Simple Meter, Beats, and Beaming (YouTube)

- Conducting Patterns (YouTube)

- Simple Meter Time Signatures (liveabout.com)

- Video Tutorial on Counting Simple Meters (One Minute Music Lessons)

- Simple Meter Counting (YouTube)

- Beaming Rules (Music Notes Now)

- Beaming Examples (Dr. Sebastian Anthony Birch)

- Time Signatures and Rhythms ( .pdf )

- Terminology, Bar Lines, Fill-in-rhythms, Re-beaming ( .pdf )

- Meters, Time Signatures, Re-beaming ( website )

- Bar Lines, Time Signatures, Counting ( .pdf )

- Time Signatures, Re-beaming, p. 4 ( .pdf )

- Fill-in-rhythms ( .pdf )

- Time Signatures ( .pdf , .pdf )

- Bar Lines ( .pdf , .pdf , .pdf )

- Notes, Rests, Bar Lines ( .pdf , .docx )

- Re-beaming ( .pdf , .musx )

The process of dividing a passage or piece of music into its component parts.

Simple Meter and Time Signatures Copyright © 2023 by Chelsey Hamm; Kris Shaffer; and Mark Gotham is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Understanding Time Signatures

Read Time: 5 Minutes

What Are Time Signatures in Music?

A time signature tells us the structure of the beat or the pulse of a piece of music. They tell us how many beats are in a bar, and how those beats might be grouped together into “strong” and “weak”, and they also provide some context for how we can expect the written notation to look.

How to Read Time Signatures

A time signature has two parts:

- The top number, which tells us how many beats are in a bar

- The bottom number, which tells us the note value of each beat

There are two types of time signature: simple and compound.

Simple: A simple time signature will usually have either a 2, 3 or 4 as the top number. It will also usually have a 4 as the bottom number, which tells us that each beat is equal to a one-quarter note (one crotchet). For example, the 4/4 time signature will have 4 beats worth one-quarter note in every bar.

Compound: A compound time signature will usually have the number, 6, 9 or 12 as the top number, and an 8 as the bottom number. This tells us two things: each beat is equal to one-eighth note (one quaver), and they are structured in groups of three.

For example, the 6/8 time signature has 6 beats, each beat is equal to one eighth note, and they are split into two groups of three.

Common Types of Time Signatures

Save or bookmark this page so you can use it as a time signature chart to reference later!

2/4 Time Signature

This is like a marching time signature, “1, 2, 1, 2” or “left, right, left, right”.

There are two crotchet beats in a bar, and they are both strong (though the first is slightly stronger than the second).

Because there are two beats, it is called “duple time” or “duple meter”, so it would be “simple duple time”.

As an example, here’s a playlist of classical marching tunes:

3/4 Time Signature

Also known as the waltz time signature, this one has 3 quarter note beats. The first beat is the strongest, while the next one is slightly weaker and the third is even weaker. “Oom pah pah, oom pah pah”.

As there are 3 beats, it is called “triple” time.

This time signature fell out of fashion in popular music and is now mainly associated with classical music.

It was more popular around the 60s-80s – here’s Elvis for an example:

4/4 Time Signature

This is also sometimes called “common time” in the classical world, and it’s the most commonly used time signature.

The first beat is the strongest, with the 3rd slightly less strong.

4 beats means this is “quadruple time”.

You don’t need to go far to find examples of this, but here’s a classic from Scott Joplin:

6/8 Time Signature

This time signature has two groups of three eighth-note beats. The first note is the strongest, and the fourth is also quite strong, while the rest are weak. “1-and-a 2-and-a”.

It is often confused with the 3/4 time signature, but the 6/8 time signature is actually “duple” time – it has two strong beats, just like 2/4!

Here’s an example from everyone’s favorite rockstars – Queen:

12/8 Time Signature

Following what we’ve learned from 6/8, this time signature has four groups of three eighth notes. “1-and-a 2-and-a 3-and-a 4-and-a”.

It’s quadruple time, and quite similar to 4/4!

A much-loved example of this is Tears for Fears’ 1985 hit “Everybody Wants to Rule the World”:

Irregular Time Signatures

What happens if we have an odd number on the top of our time signature?

These time signatures are called “irregular”. They most commonly appear in jazz and classical, but you’ll see them in other genres too. Examples might include:

These types of time signatures generally split their beats into groups of two and three.

For instance, a song in 5/8 might go something like “1-and-a 2-and, 1-and-a 2-and”, where the first and fourth beats are the strong ones.

The jazz hit “Take Five” by the Dave Brubeck Quartet is a very famous example of this pattern:

While there are two strong beats in 5/4 and 5/8, they aren’t considered “duple time” because the strong beats aren’t equal in length. Instead, it is called “quintuple time”, and time signatures with 7 beats are called “septuple time”.

How To Change Time Signature

Time signatures can change at any point in a composition. It’s quite common to add single bars of 2/4 in 4/4 to create interesting variations in phrase length.

In order to change the time signature, we just put the new one at the start of the bar. Easy!

We can also switch between regular and irregular time signatures. Check out this example from Snarky Puppy – at 1:51 it switches from 4/4 to 7/8 in a pattern of 2+2+3.

To wrap up, here are the main points to remember about time signatures:

- They tell us the structure of the pulse of our music.

- The top number tells us how many beats are in a bar.

- The bottom number tells us whether those are a quarter note (4) or eighth note (8) in length.

- Simple time signatures have a top number of 2, 3 or 4.

- Compound time signatures have a top number of 6, 9 or 12, and their beats are grouped together in threes.

- Irregular time signatures have an odd number on top.

Join Our Community

Stay right up to date with new expert tips, production guides, and free lessons. Delivered straight to your inbox!

AP Notes, Outlines, Study Guides, Vocabulary, Practice Exams and more!

Class Notes

Social science.

- European History

- Human Geography

- US Gov and Politics

- World History

- Trigonometry

- Environmental Science

- Art History

- Music Theory

Textbook Notes

Members only.

- Textbook Request

You are here

Meter and time signature.

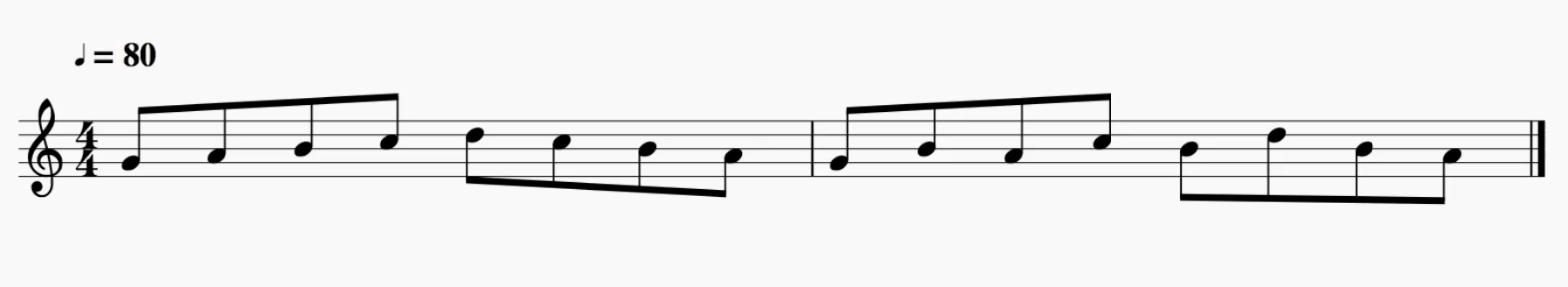

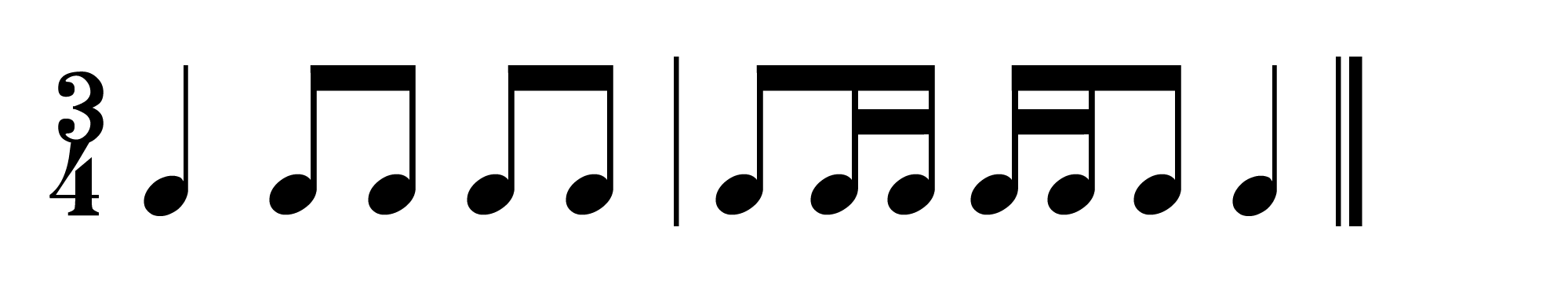

Meter is the pattern of pulses or beats on which the rhythms of a piece are based. The rhythms of a meledy can go faster or slower, but the beat marches on at a steady pace. It is like drawing a picture on a piece of graph paper. Each square on the graph is like a beat. When you count out the beats, you are counting the meter. Most pieces have either 2, 3, or 4 regular beats per measure. When you play a melody, you usually accent the notes which start on the beat. When you play faster notes, they usually divide the beat into either 2 or 3 parts. Fer examp|e, the song "Yankee Doodle" has two beats per measure and the beat divides into 2 parts:

Hickory Dockery Doc also has two beats per measure, but the rhythms divide the beat into three parts:

A time signature is a sign which helps show you what the meter is. The most common time signatures are 2/4, 3/4, 4/4. For these simple time signatures, the top number tells you how many beats per measure and the bottom number reminds you that a quarter-note (1/4) gets the beat. "Yankee Doodle" would use a time signature of 2/4. Here is an example of a piece with 3 quarter—notes per measure (3/4 time):

6/8 is another frequent time signature. Unfortunately, it is not simple; it is rather confusing. Many people think that 6/8 means 6 beats per measure with an eighth-note getting the beat. Not true. 6/8 is used fer pieces where the beat divides into 3 parts, like Hickory Dickory Dock". The time signature fer "Hockery Dockery" is supposed to show 2 beats per measure with a dotted quarter-note getting the beat, like the examp|e below:

Remember, keys don't come from key signatures and meters don't come from time signatures. When you are listening to actual music, you often can imagine counting it out in different ways (fast and slow). Follow this basic guideline: Question: How many beats are in a measure? Answer: As few as possible. For examp|e, when you see 6/8, trust the music itself (not the sign post) and count it in two, not six: 1 la li 2 la li (never 1 23 4 56).

We hope your visit has been a productive one. If you're having any problems, or would like to give some feedback, we'd love to hear from you.

For general help, questions, and suggestions, try our dedicated support forums .

If you need to contact the Course-Notes.Org web experience team, please use our contact form .

Need Notes?

While we strive to provide the most comprehensive notes for as many high school textbooks as possible, there are certainly going to be some that we miss. Drop us a note and let us know which textbooks you need. Be sure to include which edition of the textbook you are using! If we see enough demand, we'll do whatever we can to get those notes up on the site for you!

About Course-Notes.Org

- Advertising Opportunities

- Newsletter Archive

- Plagiarism Policy

- Privacy Policy

- DMCA Takedown Request

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

I. Fundamentals

Compound Meter and Time Signatures

Chelsey Hamm and Mark Gotham

Key Takeaways

- Compound meters are meters in which the beat divides into three and then further subdivides into six.

- Duple meters have groupings of two beats, triple meters have groupings of three beats, and quadruple meters have groupings of four beats. You can determine these groupings aurally by listening carefully and tapping along to the beat.

- There are different conducting patterns for duple, triple, and quadruple meters; these are the same in both compound and simple meters.

- Time signatures in compound meters express two things: how many divisions are contained in each measure (the top number), and the division unit — which note gets the division (the bottom number).

- Rhythms in compound meters get different counts based upon their division unit. Beats that are not articulated (because they contain more than one beat or because of ties, rests, or dots) receive parentheses around their counts.

Chapter Playlist

In the previous chapter, Simple Meter and Time Signatures, we explored rhythm and time signatures in simple meters —meters in which the beat divides into two and further subdivides into four. In this chapter, we will learn about compound meters —meters in which the beat divides into three and further subdivides into six.

Listening to and Conducting Compound Meters

Compound meters can be duple , triple , or quadruple , just like simple meters. In other words, the beats of compound meters group into sets of either two, three, or four. The difference is that each beat divides into three divisions instead of two, as you can hear by listening carefully to the following examples:

“End of the Road” (1992) by Boyz II Men is in a duple meter —the beats group into a two pattern. Tap along to the beat and notice how it divides into three parts instead of two. If you further divide the beat (by tapping twice as fast), you will feel that the beat subdivides into six parts.

- T he second movement (Minuet) of Franz Joseph Haydn’s Sonata no. 42 in G Major (1784) is in a compound triple meter . Listen for the groupings of three beats, each of which divides into three.

- Finally, a compound quadruple meter contains four beats, each of which divides into three. Listen to “Exogenesis Symphony Part III” (2010) by the alternative rock band Muse. This is in a compound quadruple meter; in other words, the beats are grouped into a four pattern.

In general, it is less common for music to be written in compound meters. Nonetheless, you must learn how to read music and perform in these meters in order to master Western musical notation.

Review the conducting patterns for simple meters in the previous chapter , as they are the same for compound meters.

Time Signatures

Measures in compound meters are equivalent to one beat grouping (duple, triple, or quadruple), just as they are in simple meters. However, the two numbers in the time signature express different information for compound meters. The top number of a time signature in compound meter expresses the number of divisions in a measure, while the bottom number expresses the division unit —which note value is the division. Example 1 shows a common compound-meter time signature.

Just like in simple meter, compound-meter time signatures are not fractions (and there is no line between the two numbers), and they are placed after the clef on the staff. In Example 1 , the top number (6) means that each measure will contain six divisions; the bottom number (8) means that the eighth note is the division. This means that each measure in this time signature will contain six eighth notes, as you can verify by examining Example 1 .

In compound meters, the top number is always a multiple of three. Divide this number by three to find the corresponding number of beats in simple meter: top numbers of 6, 9, and 12 correspond to duple, triple, and quadruple meters respectively. In compound meters, the bottom number is usually one of the following:

- 8, which means the eighth note receives the division.

- 4, which means the quarter note receives the division.

- 16, which means the sixteenth note receives the division.

The following table summarizes the six categories of meters that we have covered so far:

Example 2. Categories of meters.

Counting in Compound Meter

While counting compound meter rhythms, it is recommended that you conduct in order to keep a steady tempo. Because beats in compound meter divide into three, they are always dotted. Beats in compound meter are as follows:

- If 8 is the bottom number, the beat is a dotted quarter note (equivalent to three eighth notes).

- If 4 is the bottom number, the beat is a dotted half note (equivalent to three quarter notes).

- If 16 is the bottom number, the beat is a dotted eighth note (equivalent to three sixteenth notes).

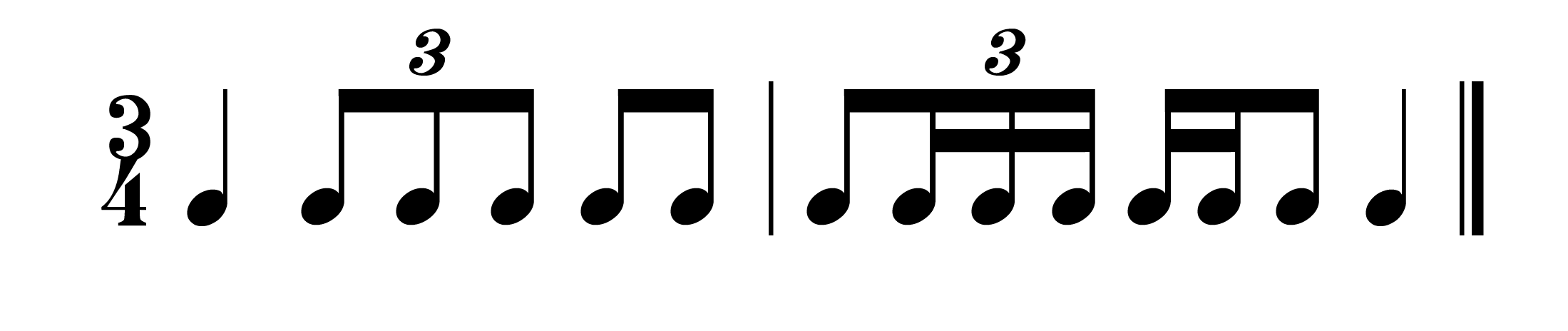

In simple meters, the beat divides into two parts, the first accented and the second non-accented. In compound meters, the beat divides into three parts, the first accented and the second and third non-accented. The counts for compound meter are different from simple meter, as demonstrated in Example 3 , which is in [latex]\mathbf{^6_8}[/latex].

Example 3. Counting in a compound duple meter.

In this time signature, each measure has two beats (6÷3=2), indicating duple meter. Each dotted quarter note (the beat) gets a count, which is expressed in Arabic numerals, like in simple meter. For notes that are longer than one beat (such as the dotted half note in the fourth measure of Example 3 ), the beats that are not counted out loud are still written in parentheses. Divisions are counted using the syllables “la” (first division) and “li” (second division). As the final measure of Example 3 shows, further subdivisions at the sixteenth-note level are counted as “ta,” with the “la” and “li” syllables on the eighth-note subdivisions remaining consistent.

The third measure of Example 3 presents two of the most common compound-meter rhythms with divisions, so make sure to review this measure carefully if you are not familiar with compound meter.

Please note that your instructor may employ a different counting system. Open Music Theory privileges American traditional counting, but this is not the only method.

Example 4 gives examples of rhythms in (a) duple, (b) triple, and (c) quadruple meter. Just as with simple meters, compound duple meters have only two beats, compound triple meters have three beats, and compound quadruple meters have four beats.

Like in simple meters, beats that are not articulated because of rests and ties are written in parentheses and not counted out loud, as shown in Example 5 . However, because dotted notes receive the beat in compound meters, dotted rhythms do not cause beats to be written in parentheses the way they do in simple meters.

Example 5. Beats that are not counted out loud are put in parentheses.

Counting with Division Units of 4 and 16

So far, we have focused on meters with a dotted-quarter beat. In compound meters with other beat units (shown in the bottom number of the time signature), the same counting patterns are used for the beats and subdivisions, but they correspond to different note values ( Example 6 ).

Example 6. The same rhythm written with three different beat units: (a) dotted quarter, (b) dotted half, and (c) dotted eighth.

Each of these rhythms sounds the same and is counted the same. They are also all considered compound triple meters. The difference in each example is the bottom number—which note gets the division unit (eighth, quarter, or sixteenth), which then determines the beat unit.

Beaming, Stems, and Flags

In compound meters, beams still connect notes together by beat; beaming therefore changes in different time signatures. In the first measure of Example 7 , sixteenth notes are grouped into sets of six, because six sixteenth notes in a [latex]\mathbf{^6_8}[/latex] time signature are equivalent to one beat. In the second measure of Example 7 , sixteenth notes are grouped into sets of three, because three sixteenth notes in a [latex]\mathbf{^{\:6}_{16}}[/latex] time signature are equivalent to one beat.

When the music involves note values smaller than a quarter note, you should always clarify the meter with beams, regardless of whether the time signature is simple or compound. Example 8 shows twelve sixteenth notes beamed properly in two different meters. The first measure is in simple meter, so the notes are grouped by beat into sets of four; in the second measure, the compound meter requires the notes to be grouped by beat into sets of six.

The same rules of stemming and flagging that applied in simple meter still apply in compound meter. For notes above the middle line, stems and flags point downward on the left side of the note, and for notes below the middle line, stems and flags point upward on the right side of the note. Stems and flags on notes on the middle line can point in either direction, depending on the surrounding notes.

Like in simple meters, partial beams can be used for mixed rhythmic groupings. If you aren’t yet familiar with these conventions, pay special attention to how the notes in Example 9 are beamed.

- Compound Meter Tutorial (musictheory.net) (compound meter starts about halfway through)

- Simple vs. Compound Time Signatures (YouTube) (start at 1:49 for compound meter)

- Compound Meter Counting and Time Signatures (John Ellinger)

- Compound Meter Counting (YouTube)

- Compound Meter Rhythmic Practice (YouTube)

- Compound Meter Beaming (Michael Sult)

- Meter Identification (Simple and Compound) ( .pdf ,), and with Bar Lines ( .pdf )

- Meter Beaming (Simple and Compound) ( .pdf ), and pp. 4 and 5 ( .pdf )

- Time Signatures (Simple and Compound) ( .pdf )

- Counting in 6/8 ( .pdf , .pdf , .pdf )

- Time Signatures ( .pdf , .pdf , .pdf )

- Bar Lines ( .pdf ), and p. 2 ( .pdf )

- Notes, Rests, Bar Lines ( .pdf , .docx )

- Re-beaming ( .pdf , .musx )

Media Attributions

- Compound Meter Time Signature © Chelsey Hamm is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Simple and Compound Beaming © Mark Gotham is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

A meter that divides the beat into three parts.

A meter with two beats per measure.

A meter with three beats per measure.

A meter with four beats per measure.

An indication of meter in Western music notation, often made up of two numbers stacked vertically.

The note value that divides the beat into two or three parts (in simple or compound meters, respectively); for example, the eighth note in 4/4 or 6/8.

A meter that divides the beat into two parts.

Created by bar lines, a measure (or bar) is equivalent to one beat grouping.

The horizontal lines that connect certain groups of notes together.

OPEN MUSIC THEORY Copyright © 2023 by Chelsey Hamm and Mark Gotham is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Find what you need to study

Unit 1 Overview: Pitch, Major Scales and Key Signatures, Rhythm, Meter, and Expressive Elements

10 min read • january 30, 2023

1.1: Pitch and Pitch Notation

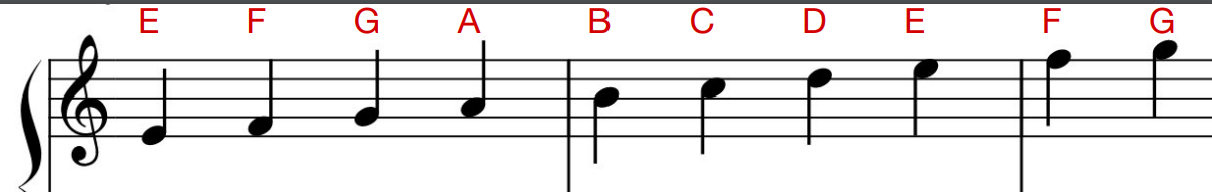

Reading notes on a staff.

The first thing that we will learn in this course is how to read music written on the staff. One staff contains 5 lines and the spaces between those lines are also significant. The grand staff is a series of two staves, which are used to notate pitches that come from a wide range of voices. The grand staff consists of two clefs: the treble clef and the bass clef .

Here are the pitches of the lines of the treble clef:

The bottom line on the treble clef is an E. The space right above that is an F. The next line is a G. We read the first three notes of this example as E-F-G. You might already see a pattern here! For each line and subsequent space, we go through the alphabet. What happens when we get to G? We start over again at A. The fourth note is A, the 5th note is a B, and the 6th note is a C. See how that works?

There are several ways to remember all the different lines and spaces on the treble clef. Many people use a mnemonic device to remember the order of the lines (E-G-B-D-F). For example, the age-old sentence is: "Every Good Boy Does Fine."

The spaces on the treble clef spell one easy word: FACE!

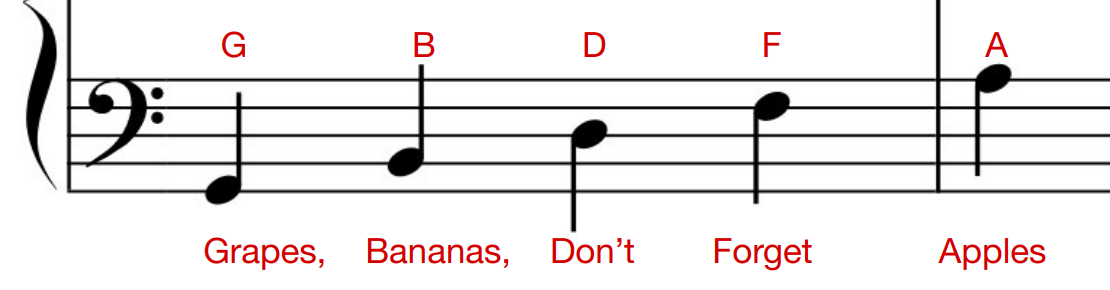

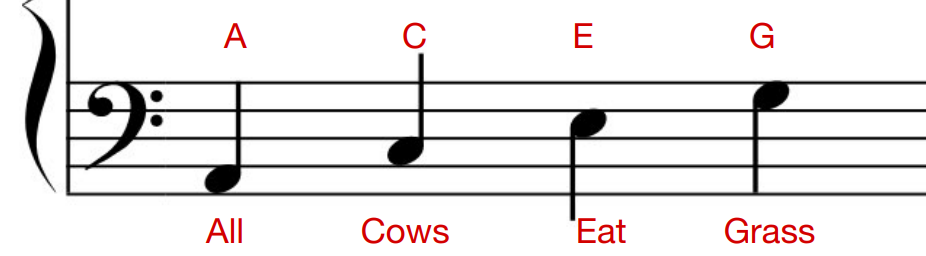

On the bass clef, the lowest line is a G, and the lowest space is an A. Here are some ways to remember the bass clef lines (G-B-D-F-A):

"Good Birds Don't Fly Away"

"Go Buy Donuts For Al"

"Grapes, Bananas, Don't Forget Apples"

"Good Boys Do Fine Always"

Last, but not least, we have the spaces on the bass clef (A-C-E-G)

Accidentals

Accidentals alter pitches by a half step. The sharp ♯ indicates that a pitch will go up by one half step. The flat ♭ indicates that a pitch will go down by one half step. And, the natural ♮ cancels any flat or sharp that a pitch may have had.

Notes are organized into measures . The vertical line that spans between the treble and bass clefs indicate the end of a measure. Sometimes measures are called bars . The line can also be called a bar line .

1.2: Rhythmic Values

The beat is the most basic unit of time in a measure. Some notes can take up multiple beats, and others will take up only a portion of a beat.

The number of beats per measure depends on the time signature . The time signature not only determines how many beats there are per measure, but it also tells you which note value gets counted as one beat. For simplicity's sake, however, we'll just assume that a quarter note is one full beat for now.

Beats are important to know in music because they help us organize the rhythmical symbols. These are called quarter notes . Each quarter note has a value of 1 beat.

If you divide a quarter note in half, you get an 8th note . This means there are two 8th notes for every quarter note beat.

If you divide an 8th note in half, you get a 16th note .

There are also half notes and whole notes. A half note takes up two beats. A half note looks just like a quarter note, but with an open circle instead of a full circle.

Whole notes take up 4 beats, and they are just one open circle with no stem.

Each note value has a corresponding rest , which tells us to pause for that amount of time. There are quarter rests, eighth rests, sixteenth rests, half rests, and whole rests.

1.3: Half Steps and Whole Steps

Imagine that you are sitting in front of a piano or a keyboard, and you play every single note, black or white, in order. You might play A-Bb-B-C-C#-D-Eb-E-F-F#-G-G#-A. This is called the chromatic scale . Notice that not all of the transitions have accidentals . For example, B# is enharmonically equivalent to C natural, and E# is enharmonically equivalent to F natural.

A chromatic scale is special because all of the notes are a half step apart. In other words, these notes are right next to each other on the keyboard. For example, C is a half step away from C#, and E is a half step away from F.

A whole step is just two half steps. C is a whole step away from D, and E is a whole step away from F#, for example.

1.4: Major Scales and Scale Degrees

When we arrange certain pitches in a specific ascending or descending pattern of whole steps and half steps, we call that a scale . Western music is comprised of major and minor scales. There are many other types of scales that are used in other parts of the world.

How do you create a major scale ? Let's first see what it looks like.

This is a C Major scale . It starts on a C, and ends on a C. A scale will always end on same note an octave higher (or lower). An octave is an interval of 8 pitches. We usually write major scales (and chords) using capital letters.

There is a very specific space between each pitch in a major scale : whole step-whole step-half step-whole step-whole step-whole step-half step. You don't really have to memorize this. You can just try deriving it from the C Major scale (the C major scale has no accidentals ), or you can memorize which sharps and flats each major scale has. This is why the major scale is also known as the diatonic scale -- it is made up of five whole steps and two half steps, which are also known as "tones" and "semitones" respectively.

When we are writing in a certain key, for example C Major, we say that we are "in C Major." You can imagine all the notes that are a member of C Major as being in the key, and all the notes that are not a member of C Major as being out of the key. For example, D is in C Major, and D# is not in C Major. Another way to say this is to say that D is diatonic, and D# is chromatic.

The starting pitch of a major or minor scale is called the tonic . Each pitch is considered to be a degree of the scale, and each scale degree has a special name. For example, in a C Major scale , the first scale degree is C, the second scale degree is D, and so on. Each scale degree has a special name that is indicative of its role in the key.

The degrees of a scale, in order, are the tonic , supertonic , mediant , subdominant , dominant , submediant , and leading tone . They correspond to the seven scale degrees of a major or minor scale.

The major scale degrees are often abbreviated using Roman numerals, with uppercase numerals representing major chords and lowercase numerals representing minor chords. For example, the tonic of a C major scale would be represented as "I," the dominant would be represented as "V," and the submediant would be represented as "vi."

1.5: Major Keys and Key SIgnatures

When the majority of a musical passage congregates around the pitches of a major or minor scale, we consider it to be within a certain key. For example, if the notes of an F major scale are used and F is considered a central pitch, the piece of music is referred to as "in the key of F major".

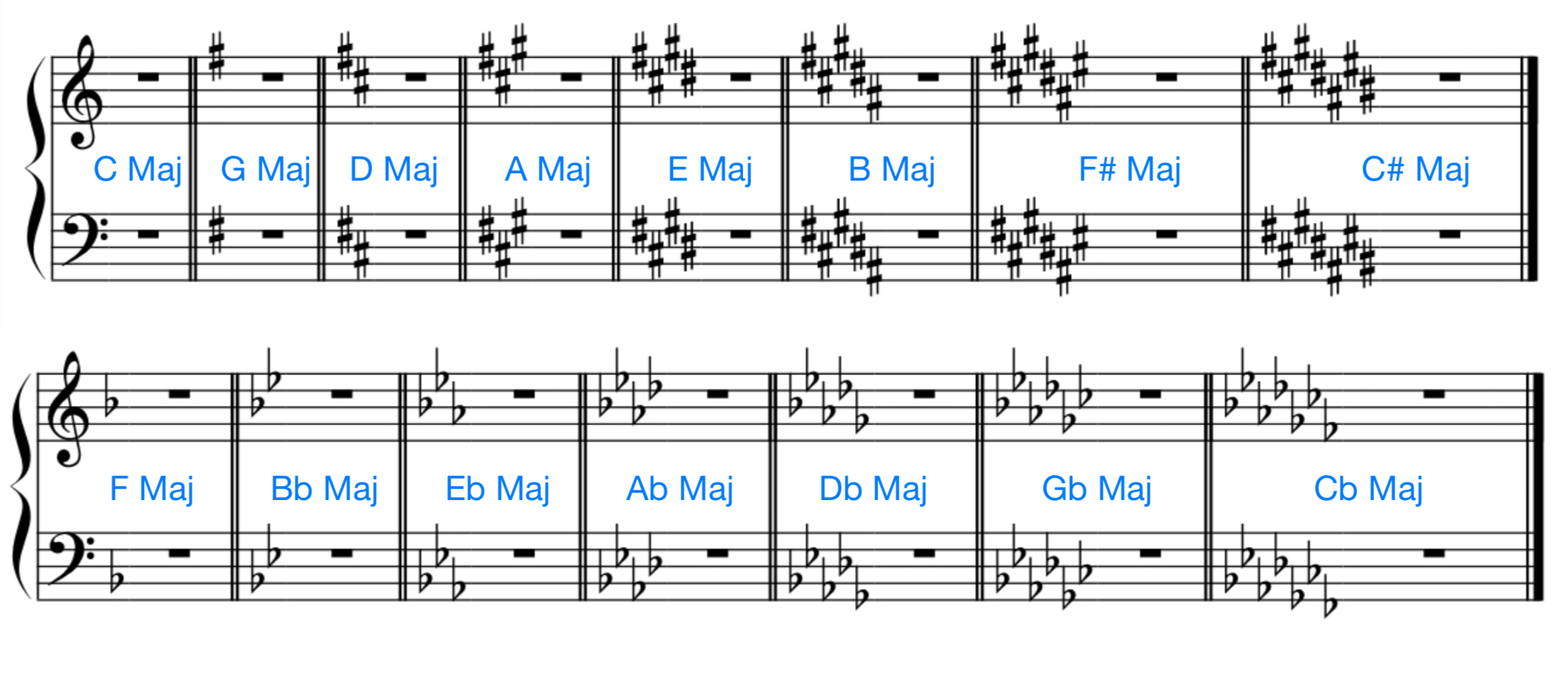

The key signature is placed on the same line as the treble clef and the time signature , and it appears immediately after the clef and time signature . It consists of one or more sharp or flat symbols, placed in a specific order, that indicate which notes are to be played as sharp or flat.

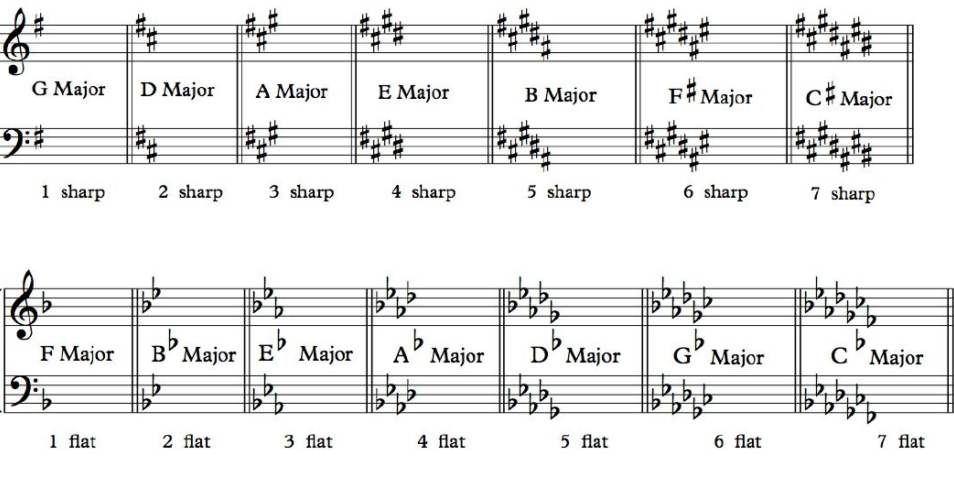

Below are all of the different key signatures. Note that Maj is short for major—you may frequently see that abbreviation.

1.6: Simple and Compound Beat Division