Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

Abbreviations in Research: Common Errors in Academic Writing

“Provided they are not obscure to the reader, abbreviations communicate more with fewer letters. Writers have only to ensure that the abbreviations they use are too well known to need any introduction, or that they are introduced and explained on their first appearance.”

—From “The Cambridge Guide to English Usage” by Pam Peters 1

David Crystal defines abbreviations as “a major component of the English writing system, not a marginal feature. The largest dictionaries of abbreviations contain well over half a million entries, and their number is increasing all the time.” 2 Students and researchers often use abbreviations in research writing to save space, especially when facing restrictions of page or word limits. Abbreviations in research are also used in place of long or difficult phrases for ease of writing and reading. Exactly how abbreviations in research writing should be used depends on the style guide you follow. For example, in British English, the period (or full stop) is omitted in abbreviations that include the first and last letters of a single word (e.g., “Dr” or “Ms”). But in American English, such abbreviations in writing are followed by a period (e.g., “Dr.” or “Ms.”).

While using abbreviations in academic writing is a common feature in many academic and scientific papers, most journals prefer keeping their use to a minimum or restricting their use to standard abbreviations. As a general rule, all non-standard acronyms/abbreviations in research papers should be written out in full on first use (in both the abstract and the paper itself), followed by the abbreviated form in parentheses, as in the American Psychological Association (APA) style guide.

Table of Contents

- Mistakes to avoid when using acronyms and abbreviations in research writing3

- Tips to using abbreviations in research writing

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Mistakes to avoid when using acronyms and abbreviations in research writing 3.

- Avoid opening a sentence with an abbreviation in research papers; write the word out.

- Abbreviations such as a.m., p.m., B.C., and A.D. are never spelled out. Unless your style guide says otherwise, use lowercase or small capitals for a.m. and p.m. Use capital letters or small caps for B.C. and A.D. (the periods are optional).

- Avoid RAS Syndrome: RAS Syndrome stands for Redundant Acronym Syndrome…Syndrome. For example, DC Comics—DC already stands for “Detective Comics,” making Comics after DC redundant.

- Avoid Alphabet Soup: Alphabet soup refers to using too many abbreviations in academic writing. Do not abbreviate the words if their frequency of appearance in the document is less than three.

- Do not follow acronyms with a period unless at the end of a sentence.

- When pluralizing acronyms add a lowercase “s” at the end (“three ECGs”); acronyms can be made possessive with an apostrophe followed by a lowercase “s” (“DOD’s acknowledge”).

- Acronyms are treated as singulars, even when they stand for plurals. Therefore, they require a singular verb (“NASA is planning to…”).

- Articles “a” or “an” before an acronym should be based on the opening sound rather than the acronym’s meaning. This depends on whether they are pronounced as words or as a series of letters. Use “an” if a soft vowel sound opens the acronym; else, use “a.” For example, a NATO meeting; an MRI scan.

Tips to using abbreviations in research writing

1. When to abbreviate: Using too many abbreviations in research papers can make the document hard to read. While it makes sense to abbreviate every long word, it’s best to abbreviate terms you use repeatedly.

2. Acronyms and initialisms: Define all acronyms and initialisms on their first use by giving the full terminology followed by the abbreviation in brackets. Once defined, use the shortened version in place of the full term.

3. Contractions: Using contractions (isn’t, can’t, don’t, etc.) in academic writing, such as a research paper, is usually not encouraged because it can make your writing sound informal.

4. Latin abbreviations: Latin abbreviations in research are widely preferred as they contain much meaning in a tiny package. Most style manuals (APA, MLA, and Chicago) suggest limiting the use of Latin abbreviations in the main text. They recommend using etc. , e.g. , and i.e., in parentheses within the body of a text, but others should appear only in footnotes, endnotes, tables, and other forms of documentation. But APA allows using “ et al .” when citing works with multiple authors and v. in the titles of court cases.

5. Capitalization: Abbreviations in writing are in full capital letters (COBOL, HTML, etc.). Exceptions include acronyms such as “radar,” “scuba,” and “lidar,” which have become commonly accepted words.

6. Punctuation: Abbreviations in research can be written without adding periods between each letter. However, when shortening a word, we usually add a period as follows:

Figure → Fig.

Doctor → Dr.

January → Jan.

Note that units of measurement do not require a period after the abbreviation. But, to avoid confusion with the word “ in ,” we write “ inches ” as “ in. ” in documents.

7. Create a list: Make a list of the abbreviations in research as you write. Adding such a list at the start of your document can give the reader and yourself an easy point of reference.

References

- Peters, P. The Cambridge Guide to English Usage. Cambridge University Press (2004).

- Crystal, D. Spell it out: The singular story of English spelling (2013).

- Nordquist, R. 10 Tips for Using Abbreviations Correctly (July 25, 2019). Retrieved from https://www.thoughtco.com/tips-for-using-abbreviations-correctly-1691738

Create error-free research papers with Paperpal’s AI writing tool

Abbreviations in a research paper are shortened forms of words or phrases used to represent specific terms or concepts. They are employed to improve readability and conciseness, especially when there are strict word counts and terms are mentioned frequently throughout the paper. To ensure clarity, it is essential to define each abbreviation when it is first used in the research paper. This is typically done by providing the full term followed by its abbreviation in parentheses.

Some commonly used abbreviations in academic writing include e.g. (exempli gratia), i.e. (id est), et al. (et alia/et alii), etc. (et cetera), cf. (confer), and viz. (videlicet). Additionally, there are several subject-specific abbreviations that are known by and commonly used in a field of study. However, know that abbreviations may mean different things across different fields. This makes it important to consult style guides or specific guidelines provided by the academic institution or target publication to ensure consistent and appropriate use of abbreviations in your academic writing.

An acronym is an abbreviation formed from the initial letters of a series of words and is pronounced as a word itself. For example, NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration) and UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) are acronyms. An abbreviation is a shortened form of a word or phrase but they are usually pronounced as individual letters. Examples of abbreviations include “et al.” for “et alia/et alii” and “e.g.” for “exempli gratia.”

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- Breaking Down the Difference Between Further and Farther

- Decoding the Difference Between Insure and Ensure

- Principle vs. Principal: How Are They Different?

- Adapt vs. Adopt: Difference, Meaning and Examples Comparison

Academic Translation Simplified! Paperpal Introduces “Translate” Feature Aimed at ESL Researchers

Paperpal’s 7 most read research reads of 2022, you may also like, how to use ai to enhance your college..., how to use paperpal to generate emails &..., word choice problems: how to use the right..., how to paraphrase research papers effectively, 4 types of transition words for research papers , paraphrasing in academic writing: answering top author queries, sentence length: how to improve your research paper..., navigating language precision: complementary vs. complimentary, climatic vs. climactic: difference and examples, language and grammar rules for academic writing.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

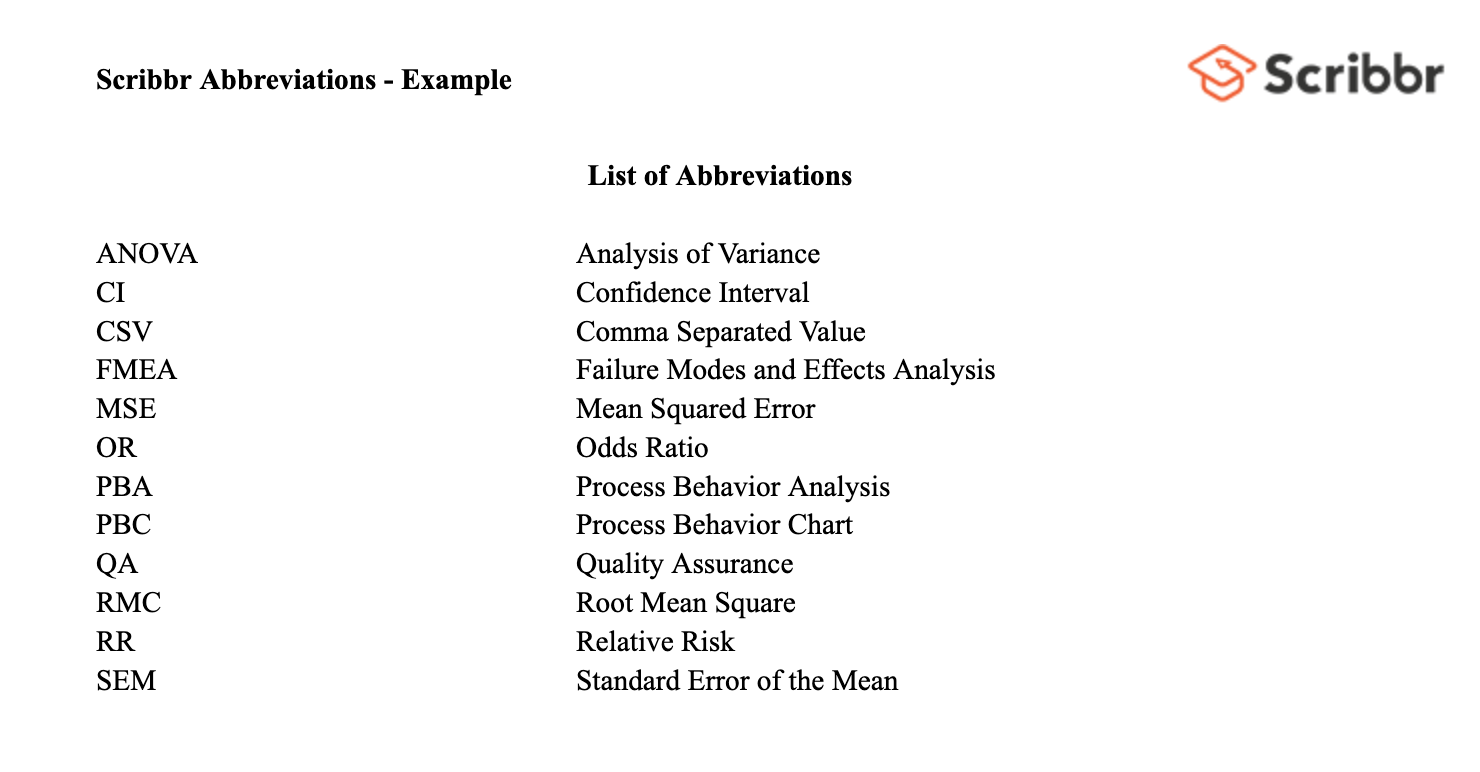

- List of Abbreviations | Example, Template & Best Practices

List of Abbreviations | Example, Template & Best Practices

Published on 23 May 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on 25 October 2022.

A list of abbreviations is an alphabetical list of abbreviations that you can add to your thesis or dissertation. If you choose to include it, it should appear at the beginning of your document, just after your table of contents .

Abbreviation lists improve readability, minimising confusion about abbreviations unfamiliar to your reader. This can be a worthwhile addition to your thesis or dissertation if you find that you’ve used a lot of abbreviations in your paper.

If you only use a few abbreviations, you don’t necessarily need to include a list. However, it’s never a bad idea to add one if your abbreviations are numerous, or if you think they will not be known to your audience.

You can download our template below in the format of your choice to help you get started.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

- Table of contents

Example list of abbreviations

Best practices for abbreviations and acronyms, additional lists to include, frequently asked questions.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

There are a few rules to keep in mind about using abbreviations in academic writing. Here are a few tips.

- Acronyms are formed using the first letter of each word in a phrase. The first time you use an acronym, write the phrase in full and place the acronym in parentheses immediately after it. You can then use the acronym throughout the rest of the text.

- The same guidance goes for abbreviations: write the explanation in full the first time you use it, then proceed with the abbreviated version.

- If you’re using very common acronyms or abbreviations, such as UK or DNA, you can abbreviate them from the first use. If you’re in doubt, just write it out in full the first time.

As well as the list of abbreviations, you can also use a list of tables and figures and a glossary for your thesis or dissertation.

Include your lists in the following order:

- List of figures and tables

- List of abbreviations

As a rule of thumb, write the explanation in full the first time you use an acronym or abbreviation. You can then proceed with the shortened version. However, if the abbreviation is very common (like UK or PC), then you can just use the abbreviated version straight away.

Be sure to add each abbreviation in your list of abbreviations !

If you only used a few abbreviations in your thesis or dissertation, you don’t necessarily need to include a list of abbreviations .

If your abbreviations are numerous, or if you think they won’t be known to your audience, it’s never a bad idea to add one. They can also improve readability, minimising confusion about abbreviations unfamiliar to your reader.

A list of abbreviations is a list of all the abbreviations you used in your thesis or dissertation. It should appear at the beginning of your document, immediately after your table of contents . It should always be in alphabetical order.

An abbreviation is a shortened version of an existing word, such as Dr for Doctor. In contrast, an acronym uses the first letter of each word to create a wholly new word, such as UNESCO (an acronym for the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization).

Your dissertation sometimes contains a list of abbreviations .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

George, T. (2022, October 25). List of Abbreviations | Example, Template & Best Practices. Scribbr. Retrieved 22 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/abbreviations-list/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, dissertation table of contents in word | instructions & examples, dissertation title page, research paper appendix | example & templates.

Using abbreviations in scientific papers

It’s time to know more about abbreviations in scientific papers and learn ways to avoid mistakes when using them.

The use of abbreviations in academic and scientific publications is common, but authors are often asked to keep their usage as brief as possible.

They are usually limited to universal abbreviations for weights and measurements. We would like to provide some tips in this article on how to use abbreviations effectively in your writing.

If you are going to use abbreviations in scientific papers , then you should pay attention to the following tips.

What do abbreviations in scientific papers mean?

Abbreviations are shortened versions of terms and phrases, such as kg for kilograms, CEO for chief executive officer and Dr. for doctors. The use of abbreviations is ideally suited to situations in which you wish to reduce the number of words the text contains.

However, there is a tendency for abbreviations to be widely used in one field of study but unknown in another. It is important to use the article that corresponds to the pronounced form of the abbreviation

Are abbreviations allowed in research papers and where do you put them?

Your paper should include a list of abbreviations at the beginning of each of the following segments: heading, abstract, text, and figure/table legends.

A common rule of thumb is to write all non-standard abbreviations in their entirety on their first appearance both in abstracts and papers themselves.

After the first mention of an abbreviation, it is essential that you use it frequently. Additionally, the format should be consistently followed throughout the paper.

Abbreviations and acronyms: what’s the difference?

The terms abbreviation and acronym are both shorthand versions of words and phrases. While abbreviations shorten longer words (like Dr. or Prof.), acronyms use the first letter of each word in a phrase to create a new word (like NASA or FBI).

There is a difference between abbreviations and acronyms, even though authors often use them the same way. An acronym, initialism, or other word contraction form is an abbreviation.

Acronyms are abbreviations formed by condensing the first letters of multiple words into one. Although not all abbreviations are acronyms, all acronyms are abbreviations. Abbreviations and acronyms differ primarily in this regard.

The most common mistakes to avoid when using abbreviations

Abbreviation errors in academic publications are sometimes common. The following are a few ways you can avoid this from happening in the future.

- It is usually advisable to define abbreviations only once when you decide to use them. Exceptions do exist, however. An abbreviation may be used at the beginning of a section in a report or chapter in a book.

- Having an inconsistent approach is the top mistake you can make. The journals will provide guidelines on how to submit your work, so please read them carefully. Generally, abbreviations in scholarly articles are introduced only after three or more instances of the term.

- It is important to use standard abbreviations if you are writing in a field that uses them – for instance, elements in the physical sciences are often abbreviated for word count constraints. Standard formatting should always be used (both spelling and case-sensitive formatting). Capitalization is typically used only for proper nouns.

- Remember that for well-known abbreviations, lowercase is recommended over uppercase for competing terms, if the same letters are used in other abbreviations in the manuscript.

- The abbreviation “et al.” can be confusing to use in scientific writing because it is often misspelt or misused. As the name suggests, this term means “and others”. In-text citations or references are often shortened with this abbreviation, and it can be used wherever it precedes a name in the text.

Here is a list of some scientific abbreviations

And the list goes on.

A professional graphical abstract that doesn’t require any effort

When you use Mind the Graph , you can make a fantastic graphical abstract in a short amount of time. What’s the hold up, well don’t wait any longer, use it today for free!

Subscribe to our newsletter

Exclusive high quality content about effective visual communication in science.

Unlock Your Creativity

Create infographics, presentations and other scientifically-accurate designs without hassle — absolutely free for 7 days!

About Aayushi Zaveri

Aayushi Zaveri majored in biotechnology engineering. She is currently pursuing a master's degree in Bioentrepreneurship from Karolinska Institute. She is interested in health and diseases, global health, socioeconomic development, and women's health. As a science enthusiast, she is keen in learning more about the scientific world and wants to play a part in making a difference.

Content tags

Community Blog

Keep up-to-date on postgraduate related issues with our quick reads written by students, postdocs, professors and industry leaders.

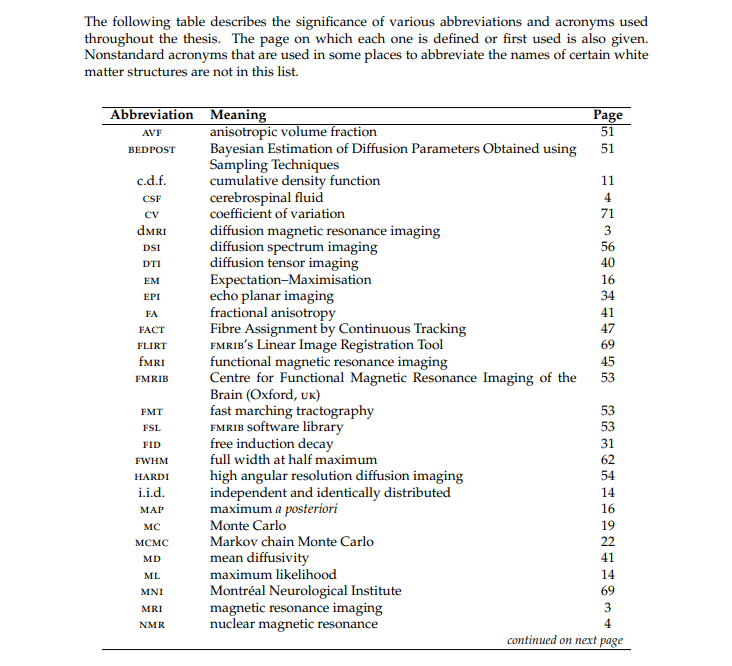

List of Abbreviations for a Thesis or Dissertation

- By DiscoverPhDs

- September 14, 2020

What are Abbreviations and Acronyms?

An abbreviation is a shortened version of a term or phrase, e.g. kg for kilogram or Dr. for doctor.

An acronym is a type of abbreviation constructed from the first letters of a term, e.g. FRP for Fibre Reinforced Polymer or STEM for Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths.

List of Abbreviations in a Thesis or Dissertation

If your thesis or dissertation contains several symbols or abbreviations, it would be beneficial to include a list of abbreviations to assist your reader. This is a list sorted in alphabetical order that gives their definitions.

This will not only help the reader better understand your research, but it will also improve the flow of your paper, as it prevents continually having to define abbreviations in your main text.

Where Does a List of Abbreviations Go?

When including a list of abbreviations, insert them near the start of the report after your table of contents. To make it clear that your document contains an abbreviated list, also add a separate heading to your table of contents.

Note: The page number for your list of abbreviations should continue from the page number that proceeds it; there is no need to reset it for this section.

Rules for Using Abbreviations and Acronyms

The first time you use an abbreviation or acronym, it is good practice to write out the full terminology or phrase followed by the abbreviation or acronym encased in parenthesis.

After defining an abbreviation or acronym for the first time in your main text, you no longer need to use the full term; for example:

Example of Acronyms in a Thesis or Dissertation

This allows the reader to understand your report without having to rely on the list of abbreviations; it is only there to help the reader if they forget what an abbreviation stands for and needs to look it up.

Note: In academic writing, abbreviations that are not listed should always be defined in your thesis text at their first appearance.

Abbreviated Exceptions

Very common abbreviations should not be included in your list because they needlessly overload your list with terms that your readers already know, which discourages them from using it.

Some examples of common abbreviations and acronyms that should not be included in your standard abbreviation list are USA, PhD , Dr. and Ltd. etc.

Example of List of Abbreviations for a Thesis or Dissertation

An example abbreviation list is as follows:

The above example has been extracted from here .

List of Symbols

You can add symbols and their definitions to your list of abbreviations, however, some people like to keep them separate, especially if they have many of them. While this format will come down to personal preference, most STEM students create a separate list of symbols and most non-STEM students incorporate them into their list of abbreviations.

Note: If you are writing your report to APA style, you will need to consider additional requirements when writing your list of abbreviations. You can find further information here .

Further Reading

Whether you’re writing a Ph.D. thesis or a dissertation paper, the following resources will also be of use:

- Title Page for an Academic Paper

- List of Appendices

Finding a PhD has never been this easy – search for a PhD by keyword, location or academic area of interest.

This post explains where and how to write the list of figures in your thesis or dissertation.

The Thurstone Scale is used to quantify the attitudes of people being surveyed, using a format of ‘agree-disagree’ statements.

Learning how to effectively collaborate with others is an important skill for anyone in academia to develop.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Browse PhDs Now

An abstract and introduction are the first two sections of your paper or thesis. This guide explains the differences between them and how to write them.

A science investigatory project is a science-based research project or study that is performed by school children in a classroom, exhibition or science fair.

Freya’s in the final year of her PhD at the University of Leeds. Her project is about improving the precision of observations between collocated ground-based weather radar and airborne platforms.

Amy recently entered her third and final year of her PhD at the University of Strathclyde. Her research has focussed on young people’s understanding of mental health stigma in Scotland.

Join Thousands of Students

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Other APA Guidelines: Abbreviations

Basics of abbreviations.

Using abbreviations can be an effective way to avoid repeating lengthy, technical terms throughout a piece of writing, but they should be used sparingly to prevent your text from becoming difficult to read.

Many abbreviations take the form of acronyms or initialisms, which are abbreviations consisting of the first letter of each word in a phrase. Examples are National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and Better Business Bureau (BBB). Note that the abbreviation uses all capital letters, and there are no periods between the letters.

To use an abbreviation, write out the term or phrase on first use, followed by the abbreviation in parentheses. See these examples:

The patient had been diagnosed with traumatic brain injury (TBI) in March of the previous year. Walden students need to know how to cite information using the American Psychological Association (APA) guidelines.

Using an Abbreviation in a Draft

After introducing the abbreviation, use the abbreviation by itself, without parentheses, throughout the rest of the document.

The patient had been diagnosed with traumatic brain injury (TBI) in March of 2014. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2015), people with TBI often have difficulty with memory and concentration, physical symptoms such as headaches, emotional symptoms such as sadness and irritability, and difficulty falling asleep. Although the patient explained that she experienced frequent headaches and difficulty concentrating, she had not been regularly taking any medication for her TBI symptoms when she visited the clinic 6 months after her diagnosis.

Note: When introducing an abbreviation within a narrative citation, use a comma between the abbreviation and the year.

Making an Abbreviation Plural

Simply add an “s” to an abbreviation to make it plural. (Do not add an apostrophe.)

I work with five other RNs during a typical shift.

Note: RN is a commonly used acronym found in Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary , so it does not need to be introduced. See the “Exceptions to the Rules” section below for more information about commonly used abbreviations.

Exceptions to the Rules

There are a few exceptions to the basic rules:

- If you use the phrase three times or fewer, it should be written out every time. However, a standard abbreviation for a term familiar in its abbreviated form is clearer and more concise, even if it is used fewer than three times.

- Commonly used acronyms and abbreviations may not need to be written out. If an abbreviation appears as a word in Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary , then it does not need to be written it out on first use. Examples include words such as IQ, REM, and HIV.

- Other than abbreviations prescribed by APA in reference list elements (e.g., “ed.” for “edition,” “n.d.” for “no date,” etc.), do not use abbreviations in the references list. For example, a source authored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention would not be abbreviated as CDC in the references list.

- If using an abbreviation for a unit of measure with a numerical value, you do not need to write the term out on first use. For example, instead of writing “12 grams;” you can simply use “12 g.” If, however, you use a unit of measure without a numerical value, write the term out (e.g., “several grams”).

- Abbreviations for time, common Latin terms, and statistical abbreviations also follow specific rules. See APA 7, Sections 6.28, 6.29, and 6.44 for more information.

United States and U.S.

In APA style, "United States" should always be spelled out when it is used as a noun or location.

Example: In the United States, 67% reported this experience.

United States can be abbreviated as "U.S." when it is used as an adjective.

Examples: U.S. population and U.S. Census Bureau.

Abbreviations Video

- APA Formatting & Style: Abbreviations (video transcript)

Related Resources

Knowledge Check: Abbreviations

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Overview

- Next Page: Active and Passive Voice

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The growth of acronyms in the scientific literature

Adrian barnett.

1 School of Public Health and Social Work, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia

Zoe Doubleday

2 Future Industries Institute, University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia

Associated Data

The analysis code and data to replicate all parts of the analyses and generate the figures and tables are available from GitHub: https://github.com/agbarnett/acronyms ( Barnett, 2020 ; copy archived at https://github.com/elifesciences-publications/acronyms ). We welcome re-use and the repository is licensed under the terms of the MIT license.

The analysis code and data to replicate all parts of the analyses and generate the figures and tables are available from GitHub: https://github.com/agbarnett/acronyms (copy archived at https://github.com/elifesciences-publications/acronyms ). We welcome re-use and the repository is licensed under the terms of the MIT license. Data was originally downloaded from the PubMed Baseline Repository (March 23, 2020; https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/baseline/ ).

Some acronyms are useful and are widely understood, but many of the acronyms used in scientific papers hinder understanding and contribute to the increasing fragmentation of science. Here we report the results of an analysis of more than 24 million article titles and 18 million article abstracts published between 1950 and 2019. There was at least one acronym in 19% of the titles and 73% of the abstracts. Acronym use has also increased over time, but the re-use of acronyms has declined. We found that from more than one million unique acronyms in our data, just over 2,000 (0.2%) were used regularly, and most acronyms (79%) appeared fewer than 10 times. Acronyms are not the biggest current problem in science communication, but reducing their use is a simple change that would help readers and potentially increase the value of science.

Introduction

As the number of scientific papers published every year continues to grow, individual papers are also becoming increasingly specialised and complex ( Delanty, 1998 ; Bornmann and Mutz, 2015 ; Doubleday and Connell, 2017 ; Cordero et al., 2016 ; Plavén-Sigray et al., 2017 ). This information overload is driving a ‘knowledge-ignorance paradox’ whereby information increases but knowledge that can be put to good use does not ( Jeschke et al., 2019 ). Writing scientific papers that are clearer to read could help to close this gap and increase the usefulness of scientific research ( Freeling et al., 2019 ; Letchford et al., 2015 ; Heard, 2014 ; Glasziou et al., 2014 ).

One feature that can make scientific papers difficult to read is the widespread use of acronyms ( Sword, 2012 ; Pinker, 2015 ; Hales et al., 2017 ; Lowe, 2019 ), and many researchers have given examples of the overuse of acronyms, and highlighted the ambiguities, misunderstandings and inefficiencies they cause ( Fred and Cheng, 2003 ; Narod et al., 2016 ; Patel and Rashid, 2009 ; Pottegård et al., 2014 ; Weale et al., 2018 ; Parvaiz et al., 2006 ; Chang et al., 2002 ). For example, the acronym UA has 18 different meanings in medicine ( Lang, 2019 ). Box 1 contains four sentences from published papers that show how acronyms can hinder understanding.

Examples of sentences with multiple acronyms.

The four sentences below are taken from abstracts published since 2000, and reflect the increasing complexity and specialisation of science.

- "Applying PROBAST showed that ADO, B-AE-D, B-AE-D-C, extended ADO, updated ADO, updated BODE, and a model developed by Bertens et al were derived in studies assessed as being at low risk of bias.’ (2019)

- "Toward this goal, the CNNT, the CRN, and the CNSW will each propose programs to the NKF for improving the knowledge and skills of the professionals within these councils.’ (2000)

- ‘After their co-culture with HC-MVECs, SSc BM-MSCs underwent to a phenotypic modulation which re-programs these cells toward a pro-angiogenic behaviour.’ (2013)

- "RUN had significantly (p<0.05) greater size-adjusted CSMI and BSI than C, SWIM, and CYC; and higher size, age, and YST-adjusted CSMI and BSI than SWIM and CYC." (2002)

In this article we report trends in the use of acronyms in the scientific literature from 1950 to the present. We examined acronyms because they can be objectively identified and reflect changes in specialisation and clarity in writing.

We analysed 24,873,372 titles and 18,249,091 abstracts published between 1950 and 2019, which yielded 1,112,345 unique acronyms. We defined an acronym as a word in which half or more of the characters are upper case letters. For example, mRNA and BRCA1 are both acronyms according to this definition, but N95 is not because two of the three characters are not upper case letters.

We found that the proportion of acronyms in titles increased from 0.7 per 100 words in 1950 to 2.4 per 100 words in 2019 ( Figure 1 ); the proportion of acronyms in abstracts also increased, from 0.4 per 100 words in 1956 to 4.1 per 100 words in 2019. There was at least one acronym in 19% of titles and 73% of abstracts. Three letter acronyms (jokingly called TLAs) were also more popular than acronyms of two and four letters.

The proportion of acronyms (purple line) has risen steadily over time in abstracts both for acronyms that are letters and/or numbers (top left) or just letters (top right). Acronyms are generally less common in titles than abstracts, and the proportion in titles has been relatively stable since 2000, but there was an increase from 1960 to 2000 (bottom left and right). Three-character acronyms (blue lines) are more common than two-character acronyms (brown-orange lines) and four-character acronyms (olive green lines) in both titles and abstracts. A sufficient number of abstracts only became available from 1956. The spikes in titles for acronyms of length 2+ in 1952 and 1964 are because of the relatively small number of papers in those years, with over 78,000 papers being excluded in 1964 because the title was in capitals.

Figure 1—figure supplement 1.

Each line shows the trend after excluding up to the n most popular acronyms ( n = 1, ..., 100). The darkest line is for n = 1, and the lightest line is for n = 100. The number of titles and journals in the early 1950s is much smaller, hence the more erratic trend for titles in that decade.

Figure 1—figure supplement 2.

Data for six article types (journal article, clinical trial, case report, comment, editorial, and other). The high proportion of acronyms in the 1950s and 1960s for ‘other’ is driven by a relatively large number of obituaries that include qualifications, such as FRCP (Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians) or DSO (Distinguished Service Order). The drop in the proportion of acronyms in 2019 for ‘clinical trials’ and ‘other’ may be due to a delay in papers from some journals appearing in PubMed.

Figure 1—figure supplement 3.

Using a truncated y−axis more clearly shows the upward trend in the use of acronyms in titles for all article types over time (by reducing the influence of ‘other’ in the 1950s and 1960s; see Figure 1—figure supplement 2 ).

The proportion of acronyms in titles has flattened since around the year 2000, whereas the proportion in abstracts continued to increase. Moreover, when the 100 most popular acronyms were removed, there was still a clear increase in acronym use over time ( Figure 1—figure supplement 1 ). Furthermore, the increase was visible in all the article types we studied (including articles, clinical trials, case reports, comments and editorials: Figure 1—figure supplement 2 ; Figure 1—figure supplement 3 ). Video 1 shows the top ten acronyms in titles for every year from 1950 to 2019, and Video 2 shows the top ten acronyms in abstracts over the same period.

There are 17,576 possible three-letter acronyms using the upper case letters of the alphabet. We found that 94% of these combinations had been used at least once. Strikingly, out of the 1.1 million acronyms analysed, we found that the majority were rarely used, with 30% occurring only once, and 49% occurring between two and ten time times. Only 0.2% of acronyms (just over 2,000) occurred more than 10,000 times. One year after their first use, only 11% of acronyms had been re-used in a different paper in the same journal. Longer acronyms were less likely to be re-used, with a 17% re-use for two-character acronyms, compared with just 8% for acronyms of five characters or longer. The time taken for acronyms to be re-used has also increased over time ( Figure 2 ), indicating that acronyms created today are less likely to be re-used than previously created acronyms.

The solid line is the estimated time in years for 10% of newly coined acronyms to be re-used in the same journal. 10% was chosen based on the overall percentage of acronyms being re-used within a year. Newly coined acronyms are grouped by year. The dotted lines show the 95% confidence interval for the time to re-use, which narrows over time as the sample size increases. The general trend is of an increasing time to re-use from 1965 onwards, which indicates that acronyms are being re-used less often. The relatively slow times to re-use in the 1950s and early 1960s are likely due to the very different mix of journals in that time.

DNA is by far the most common acronym and is universally recognised by scientists and the public ( Table 1 ). However, not all the top 20 may be so widely recognised, and it is an interesting individual exercise to test whether you, the reader, recognise them all. Six of the top 20 acronyms also have multiple common meanings in the health and medical literature, such as US and HR‚ although the meaning can usually be inferred from the sentence.

How many do you recognise?

In parallel with increasing acronym use, the average number of words in titles and abstracts has increased over time, with a steady and predominantly linear increase for titles, and a more nonlinear increase for abstracts ( Figure 3 ). The average title length increased from 9.0 words in 1950 to 14.6 words in 2019, and shows no sign of flattening. The average abstract length has also increased, from 128 words in 1962 to 220 words in 2019, and again this trend shows no sign of flattening. It is worth pointing out that these increases have happened despite the word and character limits that many journals place on the length of titles and abstracts.

The average title length has increased linearly between 1950 and 2019 (left). The average length of abstracts has also increased since 1960, except for a brief reduction in the late 1970s and a short period of no change after 2000 (right). A sufficient number of abstracts only became available from 1956. Note that the y-axes in the two panels are different, and that neither starts at zero, because we are interested in the relative trend.

Our results show a clear increase over time in the use of acronyms titles and abstracts ( Figure 1 ), with most acronyms being used less than 10 times. Titles and abstracts are also getting longer ( Figure 3 ), meaning readers are now required to read more content of greater complexity.

There have been many calls to reduce the use of acronyms and jargon in scientific papers (see, for example, Talk Medicine BMJ, 2019 , which recommends a maximum of three acronyms per paper), and many journal and academic writing guides recommend a sparing use of acronyms ( Sword, 2012 ). However, the trends we report suggest that many scientists either ignore these guidelines or simply emulate what has come before. Entrenched writing styles in science are difficult to shift ( Doubleday and Connell, 2017 ), and the creation of new acronyms has become an acceptable part of scientific practice, and for clinical trials is a recognised form of branding ( Pottegård et al., 2014 ).

We believe that scientists should use fewer acronyms when writing scientific papers. In particular, they should avoid using acronyms that might save a small amount of ink but do not save any syllables, such as writing HR instead of heart rate ( Pinker, 2015 ; Lang, 2019 ). This approach might also make articles easier to read and understand, and even help avoid potential confusion (as HR can also mean hazard ratio or hour). For more complex phrases with multiple syllables and specialist words, such as methylcyclopentadienyl manganese tricarbonyl (MMT), acronyms may ease reading and aid understanding, although MMT might mean methadone maintenance treatment to some readers.

It is difficult to make a general rule about which acronyms to keep and which to spell out. However, there is scope for journals to reduce the use of acronyms by, for example, only permitting the use of certain established acronyms (although the list of allowed acronyms would have to vary from journal to journal). In the future it might be possible, software permitting, for journals to offer two versions of the same paper, one with acronyms and without, so that the reader can select the version they prefer.

Our work shows that new acronyms are too common, and common acronyms are too rare. Reducing acronyms should boost understanding and reduce the gap between the information we produce and the knowledge that we use ( Jeschke et al., 2019 ) ‚ without 'dumbing down' the science. We suggest a second use for DNA: do not abbreviate.

Materials and methods

We use the word acronym to refer to acronyms (such as AIDS), initialisms (such as WHO) and abbreviations that include capital letters (such as BRCA). We use this broad definition because we were interested in shortened words that a reader is either expected to know or could potentially misunderstand. We did not define acronyms as those defined by the authors using parentheses, because many acronyms were not defined.

We defined an acronym as a word in which half or more of the characters are upper case letters. For example, mRNA is an acronym because it has three upper case letters out of four characters. Characters include numbers, so BRCA1 is also an acronym according to our definition, but N95 is not because two of the three characters are not upper case letters. (It should, however, be noted that N95 is an abbreviation for National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health mask that filters at least 95% of airborne particles). Our definition of an acronym was arrived at using trial and error based on the number of acronyms captured and missed.

We included common acronyms (such as AIDS) because it is difficult to make a simple ruling about what is common and hence well accepted. We instead used a sensitivity analysis that excluded the most common acronyms. We did not include acronyms that have become common words and are generally now not written in upper case letters (such as laser).

Data extraction

The data were extracted from the PubMed repository of health and medical journals provided by the National Library of Medicine. Data were downloaded between 14 and 22 April 2020. Although the PubMed repository includes papers going back to the year 1781, we used 1950 as the first year. This is because although acronyms have been around for 5,000 years, their use greatly increased after the Second World War ( Cannon, 1989 ) and there were a relatively small number of papers in PubMed prior to 1950. The details of the algorithm to extract acronyms are in Appendix 1.

Random checks of the algorithm

One researcher (AB) randomly checked 300 of each of the following by hand to verify our acronym-finding algorithm:

- Titles that were excluded

- Titles defined as having no acronyms

- Titles defined as having at least one acronym

- Abstracts defined as having no acronyms

- Abstracts defined as having at least one acronym

The numbers in Table 2 are the count of errors and estimated upper bound for the error percentage using a Bayesian calculation based on the 95th percentile of a beta distribution using the observed number of papers with and without errors. The average error rates were between 0.3% and 6.3%. Zero error rates are unlikely given the great variety of styles across journals and authors. Examples of acronyms missed by our algorithm include those with a relatively large number of lower case letters, numbers, symbols or punctuation (such as circRNA). Examples of acronyms wrongly included by our algorithm include words written in capitals for emphasis and the initials of someone's name appearing in the title as part of a Festschrift.

Exclusion reasons and numbers

Table 3 lists the most common reasons why papers were excluded from our analysis. Papers were excluded if they were not written in English, and this was the main exclusion reason for titles. Over 7 million papers had no abstract and around 10,000 had an abstract that was empty or just one word long. Over 298,000 titles and 112,000 abstracts had 60% or more of words in capital letters, making it difficult to distinguish acronyms. This 60% threshold for exclusion was found using trial and error.

Statistical analysis

We examined trends over time by plotting annual averages. The trends were the average number of words in the title and abstract, and the proportion of acronyms in abstracts and titles using word count as the denominator. To examine varied types of acronyms, we split the trends according to acronyms that were letters only compared with those using letters and numbers. We also examined trends according to the length of the acronym. We calculated 95% confidence intervals for the annual means, but in general these were very close to the mean because of the enormous sample size, and hence we do not present them.

We examined the re-use of acronyms after their first use by calculating the number of acronyms re-used in a different paper in the same journal up to one year after their first use. We used the same journal in an attempt to standardise by field and so reduce the probability of counting re-uses for different meanings (such as ED meaning emergency department in the field of emergency medicine and eating disorder in the field of psychology). We counted re-use in the title or abstract. We censored times according to the last issue of the journal. We examined whether re-use was associated with the length of the acronym.

All data management and analyses were made using R version 3.6.1 ( R Core Team, 2020 ).

Data and code availability

Limitations.

Our algorithm missed a relatively large number of acronyms that included symbols, punctuation and lower case letters. This means our estimates likely underestimate the total number of acronyms. We assumed this error is balanced over time, meaning our trends reflect a real increase in acronym use. We only examined abstracts and titles, not the main text. This is because we used an automated procedure to extract the data, and large numbers of main texts are only available for open access journals and only for recent years, making these data unsuitable for examining broad trends across the scientific literature. We took a broad look at overall trends and did not examine trends within journals or fields. However, our code and data are freely available, and hence other trends and patterns could be examined.

Acknowledgements

Computational resources and services were provided by the eResearch Office at Queensland University of Technology. We thank Ruth Tulleners for help with searching the literature and checking the data, and Angela Dean for comments on a draft.

Biographies

Adrian Barnett is in the School of Public Health and Social Work, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia

Zoe Doubleday is in the Future Industries Institute, University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia

Text processing algorithm

- The data were downloaded in eXtensible Markup Language (XML) format and read into R for processing. The complete R code is freely available on GitHub. The list of key processing steps in order are below. Unless otherwise stated, each step was applied to the title and abstract.

- Remove commonly used copyright sentences such as ‘This article is protected by copyright’ from the abstract.

- Extract the PubMed ID, date the paper was added to PubMed, title, abstract, journal name, article type, language, and number of authors.

- Remove copyright sections and sub-headings from the abstract (such as ‘BACKGROUND’).

- Remove systematic review registrations from the abstract.

- Exclude papers not in English.

- Exclude titles and abstracts that are empty.

- Exclude abstracts of 10 words or fewer that have the article type Published Erratum because they are usually just a citation/note.

- Remove Roman numerals from 1 to 30 (that is, from I to XXX). The upper limit of 30 was based on trial and error. Also remove Roman numerals suffixed with a lower case letter or ‘th’.

- Remove the chromosomes: XX, XY, XO, ZO, XXYY, ZW, ZWW, XXX, XXXX, XXXXX, YYYYY.

- Remove symbols, including mathematical symbols, spacing symbols, punctuation, currencies, trademarks, arrows, superscripts and subscripts.

- Remove common capitals from the title (such as WITHDRAWN, CORRIGENDUM and EDITORIAL).

- Remove sub-headings (such as SETTING and SUBJECTS) from the abstract. (This step is performed in addition to the sub-heading removal step mentioned above).

- Replace common units in the abstract with ‘dummy’ (for example, change ‘kg/m2’ to ‘dummy’) so that they are counted as one word during word counts.

- Remove full-stops in acronyms (so that, for example, W.H.O. becomes WHO).

- Replace all plurals by replacing "s " with a space. This removes plurals from acronyms: for example, EDs becomes ED.

- Break the title and abstract into words.

- Exclude the title or abstract if 60% or more of the words are in capitals as this is a journal style and makes it hard to find acronyms.

- Exclude abstracts with strings of four or more words in capitals. Trial and error showed that this was a journal style and it makes it hard to spot acronyms.

- Exclude the title if the first four words or last four words are in capitals. This is a journal style.

- Remove gene sequences defined as characters of six or more than only contain the letters A, T, C, G, U and p.

- Find and exclude citations to the current paper in the abstract, as these often have author initials which look like acronyms.

- Exclude titles of just one word.

- Exclude papers with a missing PubMed Date.

- Extract acronyms, defined as a word where half or more of the characters are upper case.

- Exclude acronyms longer than 15 characters, as these are often gene strings.

We did not include the following as acronyms:

- Common units of measurement like pH‚ hr or mL.

- Chemical symbols like Na or Ca.

- Acronyms that have become common words (such as laser).

- e.g. and i.e.

Funding Statement

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Contributor Information

Peter Rodgers, eLife, United Kingdom.

Funding Information

This paper was supported by the following grants:

- National Health and Medical Research Council APP1117784 to Adrian Barnett.

- Australian Research Council FT190100244 to Zoe Doubleday.

Additional information

No competing interests declared.

Conceptualization, Software, Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft.

Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing - original draft.

Additional files

Transparent reporting form, data availability.

- Barnett A. Analysing acronyms in PubMed data. 1.05 GitHub. 2020 https://github.com/agbarnett/acronyms

- Bornmann L, Mutz R. Growth rates of modern science: a bibliometric analysis based on the number of publications and cited references. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology. 2015; 66 :2215–2222. doi: 10.1002/asi.23329. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cannon G. Abbreviations and acronyms in English word-formation. American Speech. 1989; 64 :99–127. doi: 10.2307/455038. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chang JT, Schütze H, Altman RB. Creating an online dictionary of abbreviations from MEDLINE. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2002; 9 :612–620. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1139. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cordero RJ, de León-Rodriguez CM, Alvarado-Torres JK, Rodriguez AR, Casadevall A. Life science's average publishable unit (APU) has Increased over the past two decades. PLOS ONE. 2016; 11 :e0156983. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156983. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Delanty G. The Idea of the university in the global era: from knowledge as an end to the end of knowledge? Social Epistemology. 1998; 12 :3–25. doi: 10.1080/02691729808578856. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Doubleday ZA, Connell SD. Publishing with objective charisma: breaking science's paradox. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2017; 32 :803–805. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2017.06.011. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fred HL, Cheng TO. Acronymesis: the exploding misuse of acronyms. Texas Heart Institute Journal. 2003; 30 :255. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Freeling B, Doubleday ZA, Connell SD. Opinion: How can we boost the impact of publications? Try better writing. PNAS. 2019; 116 :341–343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1819937116. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Glasziou P, Altman DG, Bossuyt P, Boutron I, Clarke M, Julious S, Michie S, Moher D, Wager E. Reducing waste from incomplete or unusable reports of biomedical research. The Lancet. 2014; 383 :267–276. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62228-X. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hales AH, Williams KD, Rector J. Alienating the audience: how abbreviations hamper scientific communication. [July 9, 2020]; 2017 https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/alienating-the-audience-how-abbreviations-hamper-scientific-communication

- Heard S. On whimsy, jokes, and beauty: can scientific writing be enjoyed? Ideas in Ecology and Evolution. 2014; 7 :64–72. doi: 10.4033/iee.2014.7.14.f. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jeschke JM, Lokatis S, Bartram I, Tockner K. Knowledge in the dark: scientific challenges and ways forward. Facets. 2019; 4 :423–441. doi: 10.1139/facets-2019-0007. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lang T. The long and the short of abbreviations. European Science Editing. 2019; 45 :1114 [ Google Scholar ]

- Letchford A, Moat HS, Preis T. The advantage of short paper titles. Royal Society Open Science. 2015; 2 :150266. doi: 10.1098/rsos.150266. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lowe D. Acronym fever: we need an acronym for that. [July 9, 2020]; 2019 https://blogs.sciencemag.org/pipeline/archives/2019/07/18/acronym-fever-we-need-an-acronym-for-that

- Narod S, Ahmed H, Akbari M. Do acronyms belong in the medical literature? Current Oncology. 2016; 23 :295–296. doi: 10.3747/co.23.3122. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Parvaiz M, Singh G, Hafeez R, Sharma H. Do multidisciplinary team members correctly interpret the abbreviations used in the medical records? Scottish Medical Journal. 2006; 51 :1–6. doi: 10.1258/RSMSMJ.51.4.49E. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Patel CB, Rashid RM. Averting the proliferation of acronymophilia in dermatology: effectively avoiding ADCOMSUBORDCOMPHIBSPAC. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2009; 60 :340–344. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.10.035. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pinker S. The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person's Guide to Writing in the 21st Century. Penguin Books; 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- Plavén-Sigray P, Matheson GJ, Schiffler BC, Thompson WH. The readability of scientific texts is decreasing over time. eLife. 2017; 6 :e27725. doi: 10.7554/eLife.27725. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pottegård A, Haastrup MB, Stage TB, Hansen MR, Larsen KS, Meegaard PM, Meegaard LH, Horneberg H, Gils C, Dideriksen D, Aagaard L, Almarsdottir AB, Hallas J, Damkier P. SearCh for humourIstic and extravagant acroNyms and thoroughly inappropriate names for important clinical trials (SCIENTIFIC): qualitative and quantitative systematic study. BMJ. 2014; 349 :g7092. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7092. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- R Core Team The R project for statistical computing. [July 9, 2020]; 2020 https://www.R-project.org/

- Sword H. Stylish Academic Writing. Harvard University Press; 2012. [ Google Scholar ]

- Talk Medicine BMJ Podcast: Talk evidence – aggravating acronyms and screening (again) [July 9, 2020]; 2019 https://soundcloud.com/bmjpodcasts/talk-evidence-november-2019-acronyms-timing-of-dose-and-screening

- Weale J, Soysa R, Yentis SM. Use of acronyms in anaesthetic and associated investigations: appropriate or unnecessary? - the UOAIAAAIAOU study. Anaesthesia. 2018; 73 :1531–1534. doi: 10.1111/anae.14450. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Writing academically: Abbreviations

- Academic style

- Personal pronouns

- Contractions

Abbreviations

- Signposting

- Paragraph structure

- Using sources in your writing

Jump to content on this page:

“Quote” Author, Book

Abbreviations and acronyms are shortened forms of words or phrases. Generally, abbreviations are not acceptable in academic writing (with some exceptions, see below) and acronyms are (providing they are used as shown below).

As academic writing is formal in style, most abbreviations should be avoided. Even the common ones shown below:

Some common ones to avoid

Avoid e.g. and i.e. , instead use for example and for instance .

Avoid etc . There isn't really an alternative, so rewrite the sentence.

Avoid dept , govt . Use department , government .

Avoid NB , instead use note that .

Avoid vs or v , instead use versus or against (except in Law reports or cases)

Some acceptable abbreviations

Titles such as Mr. Dr. Prof. are acceptable when using them in conjunction with the individual's name i.e. Dr. Smith.

Some Latin phrases

et al. (short form of et alia - and others is acceptable when giving in text citations with multiple authors. The full stop should always be included afterwards to acknowledge the abbreviation. It does not need to be italicised as it is in common usage.

ibid. (short form of ibidim - in the same place) is acceptable if using footnote references to indicate that a reference is the same as the previous one. Again, always include the full stop to acknowledge the abbreviation. It is the convention to italicise this as it is less commonly used.

sic (short form of sic erat scriptum - thus it was written). This is used to indicate there was an error in something you are quoting (either an interviewee or an author) and it is not a misquote. It is added in square brackets but is neither italicised nor followed by a full stop i.e.

"it'd be great if unis [sic] could develop a person's self-knowledge"

Acronyms are acceptable, but use the name in full on its first use in a particular document (e.g. an assignment), no matter how well known the acronym is. For example, on its first use in an essay you might refer to "the World Health Organisation (WHO)" - it would be fine to simply refer to "the WHO" for the remainder of the essay.

- << Previous: Italics

- Next: Signposting >>

- Last Updated: Nov 10, 2023 4:11 PM

- URL: https://libguides.hull.ac.uk/writing

- Login to LibApps

- Library websites Privacy Policy

- University of Hull privacy policy & cookies

- Website terms and conditions

- Accessibility

- Report a problem

- Mardigian Library

- Subject Guides

Formatting Your Thesis or Dissertation with Microsoft Word

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Copyright Page

- Dedication, Acknowledgements, & Preface

- Headings and Subheadings

- Citations and Bibliography

- Page Numbers

- Tables and Figures

- Rotated (Landscape) Pages

- Table of Contents

- Lists of Tables and Figures

- Some Things to Watch For

- PDF with Embedded Fonts

List of abbreviations

Microsoft Word can automatically create a List of Abbreviations and Acronyms. If you use a lot of abbreviations and acronyms in your thesis — and even if you only use a few — there is no reason not to include a list. The process is not at all difficult. See the video tutorial below to see how to create such a list.

- << Previous: Lists of Tables and Figures

- Next: Some Things to Watch For >>

- Last Updated: Mar 21, 2024 2:35 PM

- URL: https://guides.umd.umich.edu/Word_for_Theses

Call us at 313-593-5559

Chat with us

Text us: 313-486-5399

Email us your question

- 4901 Evergreen Road Dearborn, MI 48128, USA

- Phone: 313-593-5000

- Maps & Directions

- M+Google Mail

- Emergency Information

- UM-Dearborn Connect

- Wolverine Access

- Subject guides

- Citing and referencing

- Abbreviations used in referencing

Citing and referencing: Abbreviations used in referencing

- In-text citations

- Reference list

- Books and book chapters

- Journals/Periodicals

- Newspapers/Magazines

- Government and other reports

- Legal sources

- Websites and social media

- Audio, music and visual media

- Conferences

- Dictionaries/Encyclopedias/Guides

- Theses/Dissertations

- University course materials

- Company and Industry reports

- Patents and Standards

- Tables and Figures

- Medicine and Health sources

- Foreign language sources

- Music scores

- Journals and periodicals

- Government sources

- News sources

- Web and social media

- Games and apps

- Ancient and sacred sources

- Primary sources

- Audiovisual media and music scores

- Images and captions

- University lectures, theses and dissertations

- Interviews and personal communication

- Archival material

- In-Text Citations: Further Information

- Reference List: Standard Abbreviations

- Data Sheets (inc. Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS))

- Figures & Tables (inc. Images)

- Lecture Materials (inc. PowerPoint Presentations)

- Reports & Technical Reports

- Theses and Dissertations

- Reference list guidelines

- Journal articles

- Government and industry publications

- Websites, newspaper and social media

- Conference papers, theses and university material

- Video and audio

- Images, graphs, tables, data sets

- Personal communications

- In-text Citations

- Journals / Periodicals

- Encyclopedias and Dictionaries

- Interviews and lectures

- Music Scores / Recordings

- Film / Video Recording

- Television / Radio Broadcast

- Online Communication / Social Media

- Live Performances

- Government and Organisation Publications

- Medicine & health sources

- Government/organisational/technical reports

- Images, graphs, tables, figures & data sets

- Websites newspaper & magazine articles, socia media

- Conferences, theses & university materials

- Personal communication & confidential unpublished material

- Video, audio & other media

- Generative AI

- Indigenous knowledges

APA Contents

- Introduction to APA style

- In-Text Citations

Abbreviations

- Audio and Visual media

- Journals/periodicals

- Tables and figures

- Sample reference list

- Standard abbreviations can be used in your citations.

- Some of the more commonly used examples of abbreviations are listed below.

Compiled or custom textbook

No page numbers, revised edition, translator(s).

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

MLA Abbreviations

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

There are a few common trends in abbreviating that you should follow when using MLA, though there are always exceptions to these rules. For a complete list of common abbreviations used in academic writing, see Appendix 1 in the MLA Handbook (9 th ed.).

Uppercase letter abbreviations

Do not use periods or spaces in abbreviations composed solely of capital letters, except in the case of proper names:

unless the name is only composed of initials:

Lowercase letter abbreviations

Use a period if the abbreviation ends in a lowercase letter, unless referring to an Internet suffix, where the period should come before the abbreviation:

Note: Degree names are a notable exception to the lowercase abbreviation rule.

Use periods between letters without spacing if each letter represents a word in common lowercase abbreviations:

Other notable exceptions:

Abbreviations in citations

Condense citations as much as possible using abbreviations.

Time Designations

Remember to follow common trends in abbreviating time and location within citations. Month names longer than four letters used in journal and magazine citations should be abbreviated:

Geographic Names

Use geographic names of states and countries. Abbreviate country, province, and state names.

Scholarly Abbreviations

The MLA Handbook (9 th ed.) encourages users to adhere to the common scholarly abbreviations for both in-text citations and in the works-cited page. Here is the list of common scholarly abbreviations from Appendix 1 of the MLA Handbook (9 th ed.) with a few additions:

- anon. for anonymous

- app. for appendix

- bk. for book

- c. or ca. for circa

- ch. for chapter

- col. for column

- def. for definition

- dept. for department

- e.g. for example

- ed. for edition

- et al. for multiple names (translates to "and others")

- etc. for "and so forth"

- fig. for figure

- fwd. for foreword

- i.e. for that is

- jour. for journal

- lib. for library

- MS, MSS for manuscript(s)

- no. for number

- P for Press (used for academic presses)

- p. for page, pp. for pages

- par. for paragraph when page numbers are unavailable

- qtd. in for quoted in

- rev. for revised

- sec. or sect. for section

- ser. for series

- trans. for translation

- U for University (for example, Purdue U)

- UP for University Press (for example, Yale UP or U of California P)

- vers. for version

- var. for variant

- vol. for volume

Publisher Names

Cite publishers’ names in full as they appear on title or copyright pages. For example, cite the entire name for a publisher (e.g. W. W. Norton or Liveright Publishing).

Exceptions:

- Omit articles and business abbreviations (like Corp., Inc., Co., and Ltd.).

- Use the acronym of the publisher if the company is commonly known by that abbreviation (e.g. MLA, ERIC, GPO). For publishers who are not known by an abbreviation, write the entire name.

- Use only U and P when referring to university presses (e.g. Cambridge UP or U of Arkansas P)

For more information on scholarly abbreviations, see Appendix 1 of the MLA Handbook (9 th ed.) . See also the following examples:

Advarra Clinical Research Network

Onsemble Community

Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion

Participants & Advocacy

Advarra Partner Network

Community Advocacy

Institutional Review Board (IRB)

Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC)

Data Monitoring Committee (DMC)

Endpoint Adjudication (EAC)

GxP Services

Research Compliance & Site Operations

Professional Services

Coverage Analysis

Budget Negotiation

Calendar Build

Technology Staffing

Clinical Research Site Training

Research-Ready Training

Virtual Investigator Meetings

Custom eLearning

Services for

Sponsors & CROs

Sites & Institutions

BioPharma & Medical Tech

Oncology Research

Decentralized Clinical Trials

Early Phase Research

Research Staffing

Cell and Gene Therapy

Ready to Increase Your Research Productivity?

Solutions for need.

Clinical Trial Management

Clinical Data Management

Research Administration

Study Startup

Site Support and Engagement

Secure Document Exchange

Research Site Cloud

Solutions for Sites

Enterprise Institution CTMS

Health System/Network/Site CTMS

Electronic Consenting System

eSource and Electronic Data Capture

eRegulatory Management System

Research ROI Reporting

Automated Participant Payments

Life Sciences Cloud

Solutions for Sponsors/CROs

Clinical Research Experience Technology

Center for IRB Intelligence

Insights for Feasibility

Not Sure Where To Start?

Resource library.

White Papers

Case Studies

Ask the Experts

Frequently Asked Questions

COVID-19 Support

About Advarra

Consulting Opportunities

Leadership Team

Our Experts

Accreditation & Compliance

Join Advarra

Learn more about our company team, careers, and values. Join Advarra’s Talented team to take on engaging work in a dynamic environment.

Clinical Research Acronyms and Abbreviations You Should Know

We all know there are numerous acronyms and abbreviations used in clinical research. While some can be easily deciphered, others may take some searching to find their meaning. Particularly with the recent surge in electronic systems and regulations, it can be hard to keep track of necessary abbreviations and terms.

Whether you’re new to the clinical research world or need a refresher, here’s a condensed list of common acronyms and abbreviations you may come across.

AACI: Association of American Cancer Institutes

AAHRPP: Association for the Accreditation of Human Research Protection Programs

ABSA: Association of Biosafety and Biosecurity

ACRP: Association of Clinical Research Professionals

ACTS: Association for Clinical and Translational Science

ADME: Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Elimination

ADR: Adverse Drug Reaction

AE: Adverse Event

ALCOA: Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original, Accurate

AMC: Academic Medical Center

API: Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient

API: Application Program Interface

ARO: Academic Research Organization

ASCO: American Society of Clinical Oncology

ASCPT: American Society for Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

ASGCT: American Society of Gene & Cell Therapy

BA/BE: Bioavailability/Bioequivalance

BLA: Biological Licensing Application

BSM: Biospecimen Management

caBIG: Cancer Biomedical

CAPA: Corrective and Preventive Action

CAR-T: Chimeric Antigen Receptors and T cells

CBER: Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research

CBRN: California Board of Registered Nursing

CCEA: Complete, Consistent, Enduring, Available

CCOP: Community Clinical Oncology Program

CCR: Center for Cancer Research

CCSG: Cancer Center Support Grant

CCTO or CTO: Centralized Clinical Trials Office or Clinical Trials Office

CDASH: Clinical Data Acquisition Standards Harmonization

CDER: Center for Drug Evaluation and Research

CDM: Clinical Data Management

Related article: “Improve Data Quality with 5 Fundamentals of Clinical Data Management”

CDP: Clinical Development Plan

CDRH: Center for Devices and Radiological Health

CDS: Clinical Data System

CDUS: Clinical Data Update System

CFR: Code of Federal Regulations

CMO: Contract Manufacturing Organization

CMS: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

CRA: Clinical Research Associate

CRC: Clinical Research Coordinator

Related article: “Deciphering the CRC Career Path: Key Skills and Responsibilities”

CRF: Case Report Form

CRMS: Clinical Research Management System

CRO: Contract Research Organization

CRPC: Clinical Research Process Content

CSO: Contract Safety Organization

CSR: Clinical Study Report

CTA: Clinical Trial Authorization

CTCAE: Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

CTMS: Clinical Trial Management System

CTRP: Clinical Trials Reporting Program

CTSA: Clinical and Translational Science Award

DDI: Drug-Drug Interaction

DHHS: Department of Health and Human Services

DM: Data Manager

DMC: Data Monitoring Committee

DSMB: Data and Safety Monitoring Board

EC: Ethics Committee

eCOA: Electronic Clinical Outcome Assessment

eCRF: Electronic Case Report Form

EDC: Electronic Data Capture

Learn more about Advarra’s electronic data capture system, Advarra EDC .

EHR: Electronic Health Record

EMR: Electronic Medical Record

ePRO: Electronic Patient-Reported Outcomes

eTMF: Electronic Trial Master File

FAIR: Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable

FDA: Food and Drug Administration

FE: Food Effect

FIH: First In Human

FWA: Federalwide Assurance

GCP: Good Clinical Practice

GCRC: General Clinical Research Center

GDP: Good Documentation Practice

GLP: Good Laboratory Practice

GMP: Good Manufacturing Practice

GVP: Good Pharmacovigilance Practice

HIPAA: Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

HRPP: Human Research Protection Program

IBC: Institutional Biosafety Committee

ICF: Informed Consent Form

ICH: International Council for Harmonization

IDE: Investigational Device Exemptions

IEC: Independent Ethics Committee

IHCRA: In House Clinical Research Associate

IIT: Investigator Initiated Trial

IND: Investigational New Drug (Application)

IP: Investigational Product

IRB: Institutional Review Board

ITT: Intent to Treat

IVRS: Interactive Voice Response System

IWRS: Interactive Web Response System

LTFU: Long Term Follow Up

LRAA: Local Regulatory Affairs Associate

MAC: Medicare Administrative Contractor

MAD: Multiple Ascending Dose

MCA: Medicare Coverage Analysis

Related webinar: Build a Better Budget: Using Medicare Coverage Analysis to Streamline Study Startup .

MRN: Medical Record Number

NCI: National Cancer Institute

NDA: New Drug Application

NHV: Normal Healthy Volunteer

NIH: National Institutes of Health

NLM: National Library of Medicine

OCT: Office of Clinical Trials

OHRP: Office for Human Research Protections

OSR: Outside Safety Report

PAC: Post Approval Commitments

PC: Protocol Coordinator

PD: Protocol Director

PHI: Protected Health Information

PI: Principal Investigator

PK/PD: Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic

PRE: Prompt Reporting Event

PRMC: Protocol Review and Monitoring Committee

PRMS: Protocol Review and Monitoring System

QC: Quality Control

QCT: Qualifying Clinical Trial

QMS: Quality Management System

SAD: Single Ascending Dose

SAE: Serious Adverse Event

SC: Study Coordinator

SDR: Source Document Review (Also Source Data Review)

SDTM: Study Data Tabulation Model

SDV: Source Document Verification

SIF: Site Investigator File

SMO: Site Management Organization

SOC: Standard of Care

SOE: Schedule of Events

SOP: Standard Operating Procedure

Related article: “Data Collection in Clinical Trials: 4 Steps for Creating an SOP”

SPOREs: Specialized Programs for Research Excellence

SRB: Scientific Review Board

SRC: Scientific Review Committee

SUSAR: Suspected Unexpected Serious Adverse Reaction