Research Basics

- What Is Research?

- Types of Research

- Secondary Research | Literature Review

- Developing Your Topic

- Primary vs. Secondary Sources

- Evaluating Sources

- Responsible Conduct of Research

- Additional Help

A good working definition of research might be:

Research is the deliberate, purposeful, and systematic gathering of data, information, facts, and/or opinions for the advancement of personal, societal, or overall human knowledge.

Based on this definition, we all do research all the time. Most of this research is casual research. Asking friends what they think of different restaurants, looking up reviews of various products online, learning more about celebrities; these are all research.

Formal research includes the type of research most people think of when they hear the term “research”: scientists in white coats working in a fully equipped laboratory. But formal research is a much broader category that just this. Most people will never do laboratory research after graduating from college, but almost everybody will have to do some sort of formal research at some point in their careers.

So What Do We Mean By “Formal Research?”

Casual research is inward facing: it’s done to satisfy our own curiosity or meet our own needs, whether that’s choosing a reliable car or figuring out what to watch on TV. Formal research is outward facing. While it may satisfy our own curiosity, it’s primarily intended to be shared in order to achieve some purpose. That purpose could be anything: finding a cure for cancer, securing funding for a new business, improving some process at your workplace, proving the latest theory in quantum physics, or even just getting a good grade in your Humanities 200 class.

What sets formal research apart from casual research is the documentation of where you gathered your information from. This is done in the form of “citations” and “bibliographies.” Citing sources is covered in the section "Citing Your Sources."

Formal research also follows certain common patterns depending on what the research is trying to show or prove. These are covered in the section “Types of Research.”

- Next: Types of Research >>

- Last Updated: Dec 21, 2023 3:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.iit.edu/research_basics

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Affective Science

- Biological Foundations of Psychology

- Clinical Psychology: Disorders and Therapies

- Cognitive Psychology/Neuroscience

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational/School Psychology

- Forensic Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems of Psychology

- Individual Differences

- Methods and Approaches in Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational and Institutional Psychology

- Personality

- Psychology and Other Disciplines

- Social Psychology

- Sports Psychology

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Job and work design.

- Anja Van den Broeck Anja Van den Broeck KU Leuven

- and Sharon K. Parker Sharon K. Parker University of Western Australia

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.15

- Published online: 24 May 2017

Job design or work design refers to the content, structure, and organization of tasks and activities. It is mostly studied in terms of job characteristics, such as autonomy, workload, role problems, and feedback. Throughout history, job design has moved away from a sole focus on efficiency and productivity to more motivational job designs, including the social approach toward work, Herzberg’s two-factor model, Hackman and Oldham’s job characteristics model, the job demand control model of Karasek, Warr’s vitamin model, and the job demands resources model of Bakker and Demerouti. The models make it clear that a variety of job characteristics make up the quality of job design that benefits employees and employers alike. Job design is crucial for a whole range of outcomes, including (a) employee health and well-being, (b) attitudes like job satisfaction and commitment, (c) employee cognitions and learning, and (d) behaviors like productivity, absenteeism, proactivity, and innovation. Employee personal characteristics play an important role in job design. They influence how employees themselves perceive and seek out particular job characteristics, help in understanding how job design exerts its influence, and have the potential to change the impact of job design.

- work design

- job characteristics

- satisfaction

- performance

- proactivity

“It is about a search, too, for daily meaning as well as daily bread, for recognition as well as cash, for astonishment rather than torpor; in short, for a sort of life rather than a Monday through Friday sort of dying” (Terkel, 1974 , p. xi).

Billions of people spend most of their waking lives at work, so it is fortunate that work can be a positive feature of living. Obviously, the associated salary helps to pay the bills and provides a means for a certain standard of living. But good work also structures one’s time, builds identity, allows for social contact, and enables engagement in meaningful activities (Jahoda, 1982 ). Nevertheless, although work can serve these important functions, it can also be a threat to people’s well-being, cause alienation, and result in burnout. As an extreme example of its negative effects, Chinese and French telecom workers have been reported committing suicide because of work-related issues.

Whether work is beneficial or detrimental is largely dependent upon how it is designed. Work design is defined as the content, structure, and organization of one’s task and activities (Parker, 2014 ). It is mostly studied in terms of job characteristics, such as job autonomy and workload, which are like the building blocks of work design. Meta-analytical results show that these job characteristics predict employees’ health and well-being, their cognitions and learning, and their attitudes and behavior (Humphrey, Nahrgang, & Morgeson, 2007 ; Nahrgang, Morgeson, & Hofmann, 2011 ). There is no doubt that work design is important, so it is not surprising that it has received considerable research attention (Parker, Morgeson, & Johns, 2017 ).

Throughout the 20th century , several authors developed different job-design models, which have been expanded into various contemporary perspectives. The net effect is that the literature on work design is somewhat fragmented. Rather than providing one overall framework to study the design of jobs—similar to the Big 5 framework in personality, for example—job-design models consider the topic from different angles. This diversity may be an advantage in understanding the complexity of job design, but an overview—let alone on overarching model—is lacking, which inhibits the sharing of knowledge and ultimately our understanding of job design.

Against this background, it is necessary to review the approaches that have dominated the literature around the world and the contemporary models that have emerged from them. This overview reveals the basic principles that guide views on job design: how work is conceptualized, how job characteristics relate to important outcomes, and the roles personal aspects play in job design–outcome relationships.

This article makes several contributions to the literature. First, by providing an overview of important job-design models that have dominated the work-design literature around the globe, the article introduces job-design scholars working in one research tradition to other traditions. Second, the article explicates the most important assumptions about the impact of job design across the different models and brings the assumptions together in one integrative work design (IWD) model. Finally, the article supplies an overview of fruitful avenues for future research that might stimulate future research on the important topic of job design. Although previously it had been argued that “we know all there is to know” about job design (Ambrose & Kulik, 1999 ), one in three employees in Europe still has a job of poor intrinsic quality (Lorenz & Valeyre, 2005 ) and different influences put pressure on the quality of jobs (Parker, Holman, & Van den Broeck, 2017 ) . Building on this overall model, different pathways emerge for the rejuvenation of the literature (Parker et al., 2017 ) and for fostering knowledge on how jobs can be designed so that work brings out the best in people.

Historical Overview of Models Around the Globe

Job design has a long history. Ever since people organized themselves to hunt and gather for food, or even to build the Aztec temples, people identified activities, tasks, and roles and distributed them among collaborators. The scientific study of work design, however, started with the work of Adam Smith, who described in his book The Wealth of Nations how the division of labor could increase productivity. Previously, the timing and location of work fitted seamlessly in with everyday activities, and many industries were characterized by craftsmen, who developed a product from the beginning to the end (Barley & Kunda, 2001 ). A blacksmith would craft pins starting from iron ore, while a carpenter made cupboards out of trees. But Adam Smith advocated the dissection of labor into different tasks, and the division of these task among employees, so that each would repetitively execute small tasks: One employee would cut the metal plate, while another one would polish the pins.

Scientific Management

The principle of the division of labor was further developed into scientific management (Taylor, 2004 ). Adopting a scientific approach to work in order to increase efficiency, Taylor argued that ideal jobs included single, highly simplified, and specialized activities that were repeated throughout the working day, with little time to waste in between (Campion & Thayer, 1988 ). Taylor developed his ideas in the realm of the Industrial Revolution, which made it possible to automate many of the activities in people’s jobs. Employees were essentially considered parts of the machinery, with the idea they could easily be replaced. While previously employees inherited or chose their trades and learned on the job by trial and error, with Taylorism, employees were selected and trained to execute specific tasks according to prescribed procedures and standards. Supervisors were tasked with monitoring employees’ actions, leading to the division between unskilled manual labor and skilled managerial tasks, and to the rewarding of employees according to their performance (e.g., via piecework) so that the goals of the employees (i.e., making money) would be aligned with the goal of the company (i.e., making profit).

Essential principles of Taylorism thus include simplification and specialization, but also the selection and training of employees to achieve a fit between demands of the job and employees’ abilities. Because of these principles, efficiency rocketed, and Taylorism was soon also adopted for office jobs. Today, Taylorism still inspires the design of both manufacturing and service jobs in many organizations (Parker et al., 2017 ).

Despite its positive consequences in terms of productivity, one downside of this mechanical approach to job design was that employee morale dropped. For instance, in the Midvale Steel plant, where Taylorism was implemented, employees experienced mental and physical fatigue and boredom, resulting in sabotage and absenteeism (Walker & Guest, 1952 ). The negative effects of Taylorism eventually led to the development of several less mechanistic and more motivational work designs, including social and psychological approaches.

Social Approaches to Work

In further exploring the effects of Taylorism, Mayo and his colleagues uncovered the importance of individual attitudes toward work and teams. In the famous “Hawthorne studies,” focusing on a team of Western Electric Company workers, Mayo and colleagues aimed to improve employees’ working conditions, but they failed to find strong effects of interventions like increasing or decreasing illumination, or shortening or lengthening the working day, on individual employee performance, even though such effects would be expected based on Taylorism. Rather, production went up over the course of the period in which the employees were involved and consulted in the experiment. The free expression of ideas and feelings to the management, and sustained cooperation in teams, increased employee morale and ultimately efficiency. Group norms were shown to have a strong effect on employee attitudes and behavior and were more effective in generating employee productivity than individual rewards, potentially because being part of a group increased feelings of security. In a Taylorism model, people were seen as a part of a machine, but according to Mayo, employees should be regarded as part of a social group.

The focus on groups was further developed into sociotechnical systems theory by human relations scholars at the Tavistock Institute in the United Kingdom (Pasmore, 1995 ). The scholars aimed to optimize the alignment of technical systems and employees. To make optimal use of the available technology, the scholars were convinced that teams of employees should have the autonomy to organize themselves (without too much supervision) and to manage technological problems and to suggest improvements, thereby breaking with the previous division between manual labor and managerial tasks. Furthermore, rather than advocating specialization, human relations scholars argued that, within the teams, employees should work on a meaningful and relatively broad set of tasks and that team members should be allowed to rotate, so that they would have some variety and become multi-skilled (Pasmore, 1995 ).

Sociotechnical systems theory gave rise to the use of autonomous working groups, later labeled self-managing teams . Several studies provided evidence for the positive effects of autonomous working groups on job satisfaction and performance, but the positive effects were not always found Some have therefore argued that autonomous work teams need to be implemented with care and may be most effective in uncertain contexts, where individuals can make a difference (Wageman, 1997 ; Wright & Cordery, 1999 ).

Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory

Building on the importance of employees’ attitudes, the first major model that made an explicit link between job design and employee motivation is the two-factor theory of Herzberg ( 1968 ). Herzberg started from Maslow’s need pyramid ( 1954 ) and argued that, while some job aspects caused job satisfaction, other were responsible for employee dissatisfaction. Satisfaction and dissatisfaction were thus considered independent states, with different antecedents. Dissatisfaction was said to occur when employees feel deprived of their physical, animal needs, due to a lack of “hygiene factors,” such as a decent salary, security, safe working conditions, status, good relationships at work, and attention to one’s personal life. Satisfaction, in contrast, was said to be intertwined with growth-oriented human needs and is influenced by the availability of motivators like achievement, recognition, responsibility, and growth.

Although Herzberg’s model has been criticized and has received little empirical support (Wall & Stephenson, 1970 ), it has had a vast impact on the literature on job design. First, Herzberg provided the building blocks for the meta-theory underlying job design. In building on the differentiation between basic animal needs and more human, higher order growth needs, Herzberg inspired McGregor ( 1960 ) to develop Theory X and Theory Y, two views on humankind that managers may hold that have implications for how jobs should be designed. Theory X assumes that employees are passive and lazy and need to be pushed (i.e., the stick approach to motivation) or pulled (i.e., the carrot approach to motivation) using the principles of Taylorism. In contrast, managers who hold Theory Y see employees as active and growth-oriented human beings who like to interact with their environment. Adopting this theory likely stimulates managers to design highly satisfying and motivational jobs that make optimal use of the interest and energy of employees.

Second, Herzberg was the first to develop a well-defined job-design model and to advocate the empirical study of people’s jobs, thereby paving the way for the tradition of job-design research that we know today. Moreover, Herzberg pointed out the importance of a fair wage and good working conditions, similar to Taylorism and social relations at work, as did the human relations movement. In addition, he called for attention to opportunities to learn and develop oneself, which were to be found in the content of the job. As such, Herzberg was arguably the first to advance that the true motivational potential of work is linked to the content of one’s job. He further advanced that jobs could become more motivating by job enlargement (i.e., adding additional tasks of similar difficulty) and—most importantly—job enrichment (i.e., by adding more complex task and decision authority). As in the case of autonomous teams, these practices can lead to beneficial outcomes, although the effects ultimately depend on the context and manner in which they are implemented (Axtell & Parker, 2003 ; Campion, Mumford, Morgeson, & Nahrgang, 2005 )

Hackman and Oldham’s Job Characteristics Model

Hackman and Oldham followed through on the idea of motivational jobs and exclusively focused on job content in their job characteristics model (JCM; Hackman & Oldham, 1976 ). Specifically, they argued that the motivating potential of jobs could be determined by assessing the degree of task significance, task identity, and variety, as well as the autonomy and feedback directly from the job. Moving beyond mere job satisfaction, these job characteristics were argued to lead to an expanded set of outcomes of job design, including internal motivation, performance, absenteeism, and turnover. Furthermore, where previous models were silent about the psychological process through which job design may have its impact, Hackman and Oldham proposed three psychological states as mediating mechanism: having knowledge of results, feelings responsible, and experiencing meaningfulness in the job. These states were expected to be influenced by feedback, autonomy, and the combination of task identity, task significance, and variety, respectively. While both autonomy and feedback are essential for jobs to be motivating, as each of the latter aspects relate to the same critical psychological state, task identity, task significance, and variety were considered to be interchangeable, which introduced the possibility that particular job aspects can compensate for each other, so that low task identity wouldn’t be problematic when employees experience high levels of variety.

An important contribution from Hackman and Oldham is that they acknowledged the importance of individual differences. They assumed that peoples’ skills, knowledge, and ability, as well as general satisfaction with the work context, may impact the strength of the relations between the job characteristics and the critical psychological states, and between the latter and the work outcomes (Oldham, Hackman, & Pearce, 1976 ). Perhaps the most important moderator in the JCM is peoples’ growth-need strength, which is defined as the degree to which employees want to develop in the context of work. Highly growth-oriented employees may benefit more from job enrichment.

In addition to developing the JCM, Hackman and Oldham also contributed to the job-design literature by presenting a measure (Hackman & Oldham, 1976 ), which spurred empirical research. Meta-analysis supported the basic tenets of the model, showing that motivational characteristics lead to favorable attitudinal and behavioral outcomes, via some of the critical psychological states (Fried & Ferris, 1987 ; Humphrey et al., 2007 ; Johns, Xie, & Gang, 1992 ). However, criticism has been directed at the inclusion of only a limited set of job characteristics, mediating mechanisms, and behavioral outcomes, as well as at the model’s focus only on the motivational aspects of work, while ignoring the stressful aspects (Parker, Wall, & Cordery, 2001 ) proposed an elaborated version of the JCM that identified an expanded set of work characteristics (including those more important in contemporary work, such as emotional demands and performance-monitoring demands), elaborated moderators (including, for example, operational uncertainty), and outcomes (including creativity, proactivity, and safety). This model also proposed antecedents of work design.

Karasek’s Job Demand Control Model

Karasek ( 1979 ) built on the criticisms of the JCM. In his job demand control model, he synthesized the traditions on detrimental aspects of work design (i.e., demands, including workload and role stressors) and the beneficial aspects (i.e., job control, including autonomy and skill variety) mentioned in the literature following the development of the Michigan Model (Caplan, Cobb, French, Harrison, & Pinneau, 1975 ) and the JCM, respectively. Rather than considering both aspects separately, seeing all structural work aspects as a demand, Karasek argued that job demands and job control have to be examined in combination, as the effects of each may be fundamentally different depending on the level of the other.

Specifically, Karasek built his theory on four types of jobs: Passive jobs are characterized by low demands and low control, while high-strain jobs include high job demands and low job control. Low-strain jobs are characterized by low demands and high job control, while active jobs include both high demands and high job control. These four types of jobs fall along two continua. Low- and high-strain jobs are modeled on a continuum from low strain to high strain, which over time may result in stress and health problems, while passive and active jobs are modeled on a growth-related continuum ranging from low to high activation, fostering motivation, learning, and development. Following up on the assumptions of the Michigan Model, Karasek proposed that job design not only may have short-term effects, but also in the long run, may affect employee personality: Continuous exposure to stressful jobs leads to accumulated strain, which then causes long-term anxiety that inhibits learning. Continuous exposure to active jobs, in contrast, builds experiences of mastery, which then buffers the perception of strain (Theorell & Karasek, 1996 ).

Apart from an expanded focus on the content of work in terms of job demands and job control, Karasek expanded his model by reintroducing social support, as a beneficial aspect of job design, and more specifically as an antidote to job demands. The role of social relations at work was acknowledged by Herzberg (although only as a hygiene factor) but was not included in the JCM, which continued to dominate the job-design literature in the United States.

Karasek’s model spurred research on job stress, as well as on health-related outcomes, such mortality and cardiovascular diseases (Van der Doef & Maes, 1998 ). The additive effects of job demands and job control are often found, but more cross-sectionally than over time, which suggests that reciprocal or reversed effects may also occur, with well-being, motivation, and learning also predicting job design (Hausser, Mojzisch, Niesel, & Schulz-Hardt, 2010 ). Results for the interaction between job demands and job control are limited (Van der Doef & Maes, 1999 ), even among high-quality studies (de Lange, Taris, Kompier, Houtman, & Bongers, 2003 ).

Warr’s Vitamin Model

Warr ( 1987 ) further expanded on the number of job characteristics that may influence people’s well-being. Going beyond the design of jobs, per se, Warr examined environmental aspects that may serve as vitamins for people’s well-being, in or outside the context of work. Well-being is herein broadly defined, including affective well-being, which is arranged around three axes—pleasure and displeasure, anxiety versus comfort, and depression versus enthusiasm—as well as competence, aspiration, autonomy, and integrated functioning of feeling harmonious. In total, Warr discerned nine different broad environmental factors that affect aspects of well-being, including:

Availability of money or a decent salary.

Physical security (good working conditions and working material).

Environmental clarity (low job insecurity, high role clarity, predictable outcomes, and task feedback).

A valued social position associated with, for example, task significance and the possibility to contribute to society.

Contact with others or the possibility of having (good) social relations at work, being able to depend on others, and working on a nice team.

Variety or having changes in one’s task context and social relations.

Externally generated goals or a challenging workload, with low levels of role conflict and conflict or competition with others.

Opportunity for skill use and acquisition or the potential to apply and extend one’s skills.

Opportunities for personal control or having autonomy, discretion, and opportunities to participate (Warr, 1987 ).

Intriguingly, Warr was the first to recognize that these job characteristics are not necessarily linearly related to employee well-being. Some job characteristics, and more specifically money, safety, and a valued social position, are the vitamins C and E. First, they affect employee well-being linearly, but only a certain amount, with their effects plateaus maintaining a constant effect (CE). The other job characteristics, however, are vitamins A and D and affect employee well-being in a curvilinear way: both low and high levels are detrimental, with any addition beyond a certain level leading to decrease in well-being (AD). In assuming these relations, Warr captured the widely held assumption that there can be too much of a good thing (Pierce & Aguinis, 2011 ). For example, while some amount of workload can be beneficial, too much workload may be detrimental for employees’ well-being. Similarly, too much job stimulation may contribute to negative health outcomes (Fried et al., 2013 ).

Furthermore, in line with Hackman and Oldham, Warr proposed that some employees are more susceptible to the impact of particular job characteristics than others, because their personal values or abilities fit better with particular job characteristics. For example, employees with low preference for independence benefit less from autonomy, while employees having a high tolerance for ambiguity suffer less when their environment provides less clear guidelines (Warr, 1987 ).

Research has provided some support for the vitamin model, showing that externally generated goals, autonomy, and social support may indeed have curvilinear relations with employee well-being (De Jonge & Schaufeli, 1998 ; Xie & Johns, 1995 ), but these results are not always replicated, especially not longitudinally (Mäkikangas, Feldt, & Kinnunen, 2007 ) or when general, rather than job-related, well-being is assessed (Rydstedt, Ferrie, & Head, 2006 ). One of the merits of the vitamin model is, however, that it broadened researchers’ horizons in terms of which job characteristics could influence employee well-being.

The Job Demands Resources Model of Bakker, Demerouti, and Schaufeli

The job demands resources model (JD-R model; Bakker, Demerouti, & Sanz-Vergel, 2014 ; Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner, & Schaufeli, 2001 ) aimed to provide an integrative view of job characteristics. At the core of the model lies the various job characteristics that may impact employees, which can be meaningfully classified as job demands and job resources. Job demands are defined as “those physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that require sustained physical and/or psychological (cognitive and emotional) effort or skills and are therefore associated with certain physiological and/or psychological costs” (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007 , p. 312). They are not necessarily negative, but turn into job stressors when they exceed workers’ capacities, which makes it hard for them to recover. Job resources are defined as the “physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that … (1) [are] functional in achieving work goals, (2) reduce job demands and the associated physiological and psychological costs, [or] (3) stimulate personal growth, learning, and development” (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007 , p. 312).

Just like the vitamin model, the JD-R model focuses on employee well-being as a crucial outcome. Following the positive psychology movement advocating the balanced study of the bright side of employees’ functioning (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000 ) along with the dark side, both negative (i.e., burnout) and positive (i.e., work engagement) aspects of well-being are considered as the crucial pathways through which job demands and job resources relate to a host of other outcomes, including employee physical health and well-being, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and different types of behaviors, including in-role and extra-role performance, as well as counterproductive behavior (for an overview, see Van den Broeck, Van Ruysseveldt, Vanbelle, & De Witte, 2013 ).

Job demands are considered the main cause of burnout. In being continuously confronted with job demands, employees can become emotionally exhausted because they put all their energy into the job. Under particular situations, such as when all their effort is in vain, they likely start withdrawing from their job as a means to protect themselves and become cynical, which is part of the burnout response. Job resources can also have a (limited) direct negative relationship with burnout (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004 ), but they are most crucial for the development of vigor and dedication, the main components of work engagement. Job demands and job resources are also assumed to interact, so that high levels of resources may attenuate (i.e., buffer) the association between job demands and burnout, while job demands are said to strengthen (i.e., boost) the association between job resources and work engagement.

Within the JD-R model, individual factors are modeled as personal resources, which are defined as malleable lower-order, cognitive-affective personal aspects reflecting a positive belief in oneself or the world (van den Heuvel, Demerouti, Bakker, & Schaufeli, 2010 ). As in the job characteristics model, personal resources can represent the underlying process through which job resources prevent burnout and foster work engagement (Xanthopoulou, Bakker, Demerouti, & Schaufeli, 2007 ), moderate, and—more specifically—buffer the health-impairing impact of job demands, as job resources do, and they may serve as antecedents of the job characteristics, preventing the occurrence of job demands and increasing the (perceived) availability of job resources.

Evidence supporting the JD-R model is abundant, but the model is used mostly in the European literature. Job demands and job resources are convincingly shown to relate to burnout and work engagement (Nahrgang et al., 2011 ), while some evidence is provided for their interactions and the role of personal resources (Van den Broeck et al., 2013 ).

Contemporary Job-Design Models

Over the years, various other models have been developed. They may range from slightly different perspectives on job characteristics and their roles in the prediction of employee functioning to more fundamental changes in how we could perceive job design.

For example, some scholars suggested that not all job demands are equal, but need to be differentiated into challenging and hindering job demands. While challenges are obstacles that can be overcome and hold the potential for learning, hindrances are threatening obstacles that drain people’s energy and prevent goal achievement (Lepine, Podsakoff, & Lepine, 2005 ). Some authors suggested that job demands can be either challenging, or hindering, or both, depending on the appraisal of the individual employee (Rodríguez, Kozusnik, & Peiro, 2013 ; Webster, Beehr, & Christiansen, 2010 ). Others, in contrast, argued that employees generally categorize particular job demands as challenging (e.g., workload and time pressure) or hindering (e.g., red tape and role conflict), in relatively clear-cut categorizations (Cavanaugh, Boswell, Roehling, & Boudreau, 2000 ; Van den Broeck, De Cuyper, De Witte, & Vansteenkiste, 2010 ).

Morgeson and Humphrey ( 2006 ) aimed to integrate the various job characteristics that have been examined in the literature and encouraged job-design scholars not only to focus on task characteristics, such as autonomy and variety, and social characteristics, such as social support and interdependence, but also to pick up on the work context and consider ergonomics, equipment use, and work conditions. This call aligns with the observations of Campion and Thayer ( 1985 ). They noticed that job-design scholars seem to have specialized in either the biological (e.g., concern with noise and lifting), the ergonomic (e.g., lighting, information input), the motivational (e.g., autonomy, variety), or the mechanistic (e.g., specialization, simplification) job characteristics, while Taylor, for example, considered each of these aspects in designing jobs. The more integrative view may be more beneficial, because motivational job characteristics may also have an impact on biological functioning (e.g., heart disease), and the best results may be achieved when ergonomic and motivational factors are jointly considered. For example, Das, Shikdar, and Winters ( 2007 ) found that drill press operators who had the most ergonomic tools and received training were more satisfied and performed better than their counterparts who also could use the ergonomic tools but didn’t receive any training.

New developments in the job-design literature also focused on the relations between the job characteristics and outcomes. The Demand-Induced Strain Compensation model (DISC model; de Jonge & Dormann, 2003 ), for example, further refined job-design theory by qualifying the interaction between job demands and job resources. Specifically, the DISC model assumes that job resources have more potential to buffer the negative effect of job demands on employee well-being when the demands, resources, and outcomes are all physical, cognitive, or emotional. That is, emotional resources, such as social support, may best buffer the impact of emotional demands on emotional stability (Van de Ven, De Jonge, & Vlerick, 2014 ).

More profound changes in job-design theory have been launched. For example, building on the notions of role conflict and role ambiguity (Kahn et al., 1964 ), Ilgen and Hollenbeck ( 1992 ) argued for the study of work roles, which are generally broader than people’s prescribed jobs because they also include emergent and self-imitated tasks. The focus on work roles led to a flourishing literature on role breadth self-efficacy (Parker, 1998 ), personal initiative (Frese, Garst, & Fay, 2007 ), and proactive work behavior (Parker, Williams, & Turner, 2006 ), with the argument being that work design is an especially important facilitator of these outcomes.

The relational perspective of Grant and colleagues is also a novel extension (e.g., Grant, 2007 ). In this approach, a powerful way to design work is to ensure that employees are connected with those that benefit from the work. Such an approach enhances task significance, and thereby promotes greater prosocial motivation amongst employees, which in turn benefits employee performance (for a review, see Grant & Parker, 2009 ).

Another development has been to recognize the role of work design in promoting learning. As Parker ( 2014 , p. 671) argued: “Motivational theories of work design have dominated psychological approaches to work design. However, we need to expand the criterion space beyond motivation, not just by adding extra dependent variables to empirical studies but by exploring when, why, and how work design can help to achieve different purposes.” Parker outlined existing theory and research that suggest work design might be a powerful—yet currently rather neglected—intervention for promoting learning outcomes, such as the accelerated acquisition of expert knowledge, as well as for promoting developmental outcomes over the lifespan (such as the development of cognitive complexity, or even moral development).

Nevertheless, despite, or perhaps because of, the different perspectives, the current job-design literature can be fragmented, with different job-design models offering insights to different parts of the puzzle but not necessarily the whole puzzle. To move the job-design literature forward, a more synthesized mental model of the literature has been developed that describes what can already be considered established knowledge and that highlights fruitful ways forward.

The Integrative Work Design Model

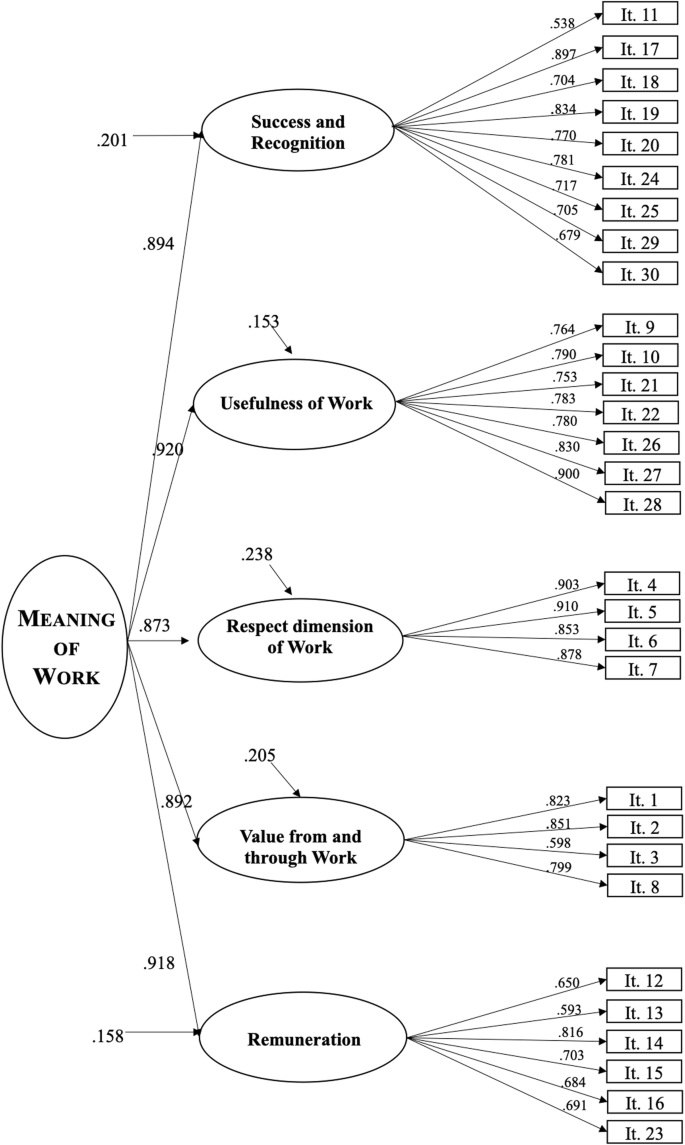

Figure 1. The Integrated Work Design (IWD) Model.

Building from the job-design models featured in the literature and the principles they put forward, an integrative work design model can be developed. The model may stimulate scholars to think broadly when studying job design and to develop new areas for research. It may equally assist managers to consider various aspects of people’s jobs when assessing the adequateness of the jobs they design. The model includes job characteristics as antecedents, and their possible relations with employee outcomes, including employee well-being, cognitions, attitudes, and behaviors. Finally, personal characteristics are taken into account as intervening variables in these relationships. The core aspects of the integrative work design (IWD) model are outlined in Figure 1 .

Job Characteristics as Antecedents

In keeping with the approach of the JD-R, the differentiation between job resources and job demands is maintained as a valuable framework for grouping job characteristics. This approach is not without criticism (Van den Broeck et al., 2013 ). For example, not all job characteristics can be easily classified as either a job demand or a job resource (e.g., job security could be a resource, while job insecurity could be a demand). However, within the IWD model it is maintained that various positive and negative events are not simply opposite ends of the spectrum (e.g., the absence of aggressive or troublesome patients doesn’t necessarily turn patient contacts into positive experiences; Hakanen, Bakker, & Demerouti, 2005 ). The difference between positive and negative reflects the universal differentiation between the positive and the negative, which is rooted in our neurophysiology and how we appraise each encounter with the environment (Barrett, Mesquita, Ochsner, & Gross, 2007 ). Negatives typically loom larger than positives and have a stronger impact on negative aspects of employee functioning, while positive aspects are more predictive of positive outcomes (Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer, & Vohs, 2001 ). This suggests that having a mindset that looks at both job demands and job resources allows scholars and managers alike to take a balanced perspective on the beneficial and detrimental characteristics of a job.

Although Warr, as well as the JD-R model, start from the assumption that several job characteristics may have an impact on employee functioning, by far the most empirical attention has been paid to the restricted list of job characteristics proposed by Karasek: autonomy, workload, and social support (Humphrey et al., 2007 ), and/or the five job characteristics covered in the JCM. To overcome this issue, a broader view on job design seems necessary. People may be inspired by new developments in the job-design literature differentiating between job challenges (e.g., responsibility) and job hindrances (e.g., red tape), as was done in the development of a model including job hindrances, challenges, and resources (Crawford, Lepine, & Rich, 2010 ; Van den Broeck et al., 2010 ). Second, the classification by Campion and Thayer ( 1985 , 1988 ) may be a source of inspiration to also include job characteristics related to human factors (e.g., equipment) and biological factors (e.g., noise, temperature), along with the mechanical (e.g., repetition) and motivational (e.g., promotion, task significance) job characteristics. Job-design scholars may consider the inclusion of context-specific job-specific hindrances, challenges, and resources, such as student aggression for teachers, number and duration of interventions for firefighters, or having contact with the patients’ families for nurses (for an overview, see Van den Broeck et al., 2013 ).

The study of specific and general job characteristics may also take into account recent developments in the labor market, such as the digital revolution, and the changes in demographics. Few studies have included the consequences of these changes in the study of contemporary jobs, although they have caused dramatic changes in job design (Cordery & Parker, 2012 ). For example, due to technological advances, jobs have undergone profound changes. While some jobs are disappearing due to automation and digitalization, the remaining jobs—for example, in supporting, maintaining, and repairing technology—have become more analytical and problem-solving in nature. Recent job-design scales therefore include concentration and precision as cognitive or mental demands (Van Veldhoven, Prins, Van der Laken, & Dijkstra, 2016 ), which may become extremely relevant for older workers who experience a decline in fluid intelligence (Krings, Sczesny, & Kluge, 2011 ). Due to the technological revolution, employees also become increasingly dependent on technology, leading to techno-stress (Tarafdar, D’Arcy, Turel, & Gupta, 2015 ). The growing body of research on this issue, however, developed outside of I/O psychology, with the leading publications in information and computer sciences. Similarly, the use of digital technology has made it possible to work from home. This increased the degree to which work-related activities intruded into private life and had implications for job design in terms of autonomy and social support (Allen, Golden, & Shockley, 2015 ; Gajendran & Harrison, 2007 ). Research interest on the impact of telework is growing, but—again—mostly as a separate field, rather than as an aspect of job design (Bailey & Kurland, 2002 ).

Finally, and again in line with the JD-R model and the recent work of Morgeson and Humphrey ( 2006 ), job demands and job resources can be found at the level of one’s task and job in general—relating to the content of work—but also at the level of the social relations at work (e.g., conflict vs. social support), which includes the social support component of the Karasek model and the call for more research on the role of social influences at work (Grant & Parker, 2009 ). Apart from the social aspects, attention could also be paid to job characteristics at the team level. In 2012 , Hollenbeck, Beersma, and Schouten noted that up to 80% of all Fortune organizations rely on teamwork to achieve their goals. Team characteristics, such as interdependence and team autonomy, have an impact on employee task characteristics, such as autonomy and well-being and performance (Langfred, 2007 ; Van Mierlo, Rutte, Vermunt, Kompier, & Doorewaard, 2007 ) and could therefore be taken into account.

Furthermore, scholars may want to go one step further and incorporate aspects at the level of the organization, such as HR-related demands and resources (e.g., strategic impact; De Cooman, Stynen, Van den Broeck, Sels, & De Witte, 2013 ) and organizational climate (e.g., safety climate; Dollard & Bakker, 2010 ). Apart from examining the direct impact of these characteristics on employee functioning, job-design scholars could also examine their interplay, in terms of how organizational and team-level variables influence social and task characteristics, as well as how the different levels may buffer, amplify, or boost each other’s impact (Parker, Van den Broeck, & Holman, 2017 ). Furthermore, scholars could examine the interplay between job characteristics through profile analyses (Van den Broeck, De Cuyper, Luyckx, & De Witte, 2012 ).

The Relations of Job Characteristics with Outcomes

The previous models have outlined that job characteristics may influence employee outcomes in many different ways. While most models assume linear relations, Warr argued for curvilinear relations, where both too little and too much of a job characteristic, such as workload, would lead to lower levels of employee well-being, an assumption that also seems to be implicit in the definition of job demands in the JD-R model. Others have argued that such curvilinear relationships are nothing less than “urban myths,” as they are difficult to establish empirically (Taris, 2006 ). Although the lack of empirical support for curvilinear relations may also be attributable to methodological shortcomings, this challenging statement has encouraged other scholars to argue that not the amount, but the type, of job demands matters for how they relate to employee functioning (Lepine et al., 2005 ; Van den Broeck et al., 2010 ). This approach ties in with the appraisal theory (Folkman & Lazarus, 1985 ), which states that the interpretation of an event as challenging or threatening determines how people react to it. Future studies may follow through on these potential curvilinear or differentiated results.

Moreover, it would be interesting to see more research on the differentiated results of particular job characteristics. While Hackman and Oldham argued that all motivational job characteristics would have an impact on employee motivation, performance, and turnover, other frameworks (e.g., Herzberg’s two-factor theory, Karasek’s job demand control model, the JD-R, and the DISC model) propose that some job characteristics would be more strongly related to particular outcomes. This is in line with the meta-analysis findings that motivational characteristics may, for example, explain more variance in performance than social characteristics, but the latter seemed to be most important in the prediction of turnover intentions (Humphrey et al., 2007 ). Furthermore, this meta-analysis showed that work-scheduling autonomy is less predictive of job satisfaction than decision-making autonomy, which shows that it is worthwhile to examine the different effects of different job characteristics.

Different Outcomes of Job Design

Within the job-design literature, different outcomes of job design have been put to the fore. Whereas Taylor mostly focused on performance, most of the motivational and health-oriented job-design models focused on aspects of employee well-being and attitudes. But none of the existing job-design models does full justice to the rich amount of consequences that have been empirically studied. The immediate, i.e., individual-level, outcomes of job design are here grouped in terms of health and well-being, cognitions and learning, attitudes, and behaviors (Cordery & Parker, 2012 ; Humphrey et al., 2007 ). The IWD model thus goes beyond mere well-being, core task performance, absenteeism, and turnover.

Health and Well-being

First, following through on their importance in job-design models, employee health and well-being have arguably been the most studied outcomes of job design. Meta-analytic results convincingly show that job characteristics like autonomy, feedback, and social support increase employee engagement and prevent employees from feeling anxious, stressed, or burned out (Humphrey et al., 2007 ; Nahrgang et al., 2011 ). In line with these results, many countries developed policies that urge employers to take care of the psychosocial risk factors—including mostly quantitative and qualitative demands, job control, and opportunities for skill development—to prevent these outcomes (Formazin et al., 2014 ).

A policy-oriented focus on the improvement of job design also has the potential to prevent more injuries and somatic health problems related to job design. For example, job characteristics are also important precursors of accidents, injuries, and unsafe behavior (Nahrgang et al., 2011 ), because high job demands and low job resources might cause employees to routinely violate safety rules (Hansez & Chmiel, 2010 ). People working in jobs of low quality also have higher risk of stroke and the development of heart disease (Backé, Seidler, Latza, Rossnagel, & Schumann, 2012 ; Eller et al., 2009 ). Similar results have been found for the experience of low back pain, pain in the shoulders or knees (Bernal et al., 2015 ), or obesity (Fried et al., 2013 ; Kim & Han, 2015 ). Interestingly, these results are mostly reported in journals featuring biomedical and human factors research (Parker et al., 2017 ), leaving these far-reaching consequences of job design relatively unnoticed in I/O psychology.

A considerable body of research established the importance of job design for employee attitudes toward work, such as organizational commitment, job involvement, and job satisfaction (Humphrey et al., 2007 ). Meta-analytic results, for example, show that job demands explain 28% of the variance in job design, while job resources can explain no less than 62% to 85% (Humphrey et al., 2007 ; Nahrgang et al., 2011 ). Results are inconclusive whether high levels of job satisfaction should be attributed primarily to good social relations at work or to the motivational characteristics defined by Hackman and Oldham.

Cognitions and Learning

While much attention has been devoted to health and well-being, research interest in cognitions as outcomes of job design has only been emerging recently and is a promising avenue for the future (Parker, 2014 ). Although more complex jobs may be challenging (Van Veldhoven et al., 2016 ), in their systematic review, Then et al. ( 2014 ) demonstrated that this might also have positive consequences, as high work complexity—together with high job control—has a protective effect against the decline of cognitive functions later in life and dementia. Increasing cognitive demands may thus start a process in which cognitive processes are maintained, if not increased. Similarly, work pressure may reduce daytime intuitive decision making, but enhance analytical thinking (Gordon, Demerouti, Bipp, & Le Blanc, 2015 ) and foster learning (De Witte, Verhofstadt, & Omey, 2007 ), as could be expected based on Karasek’s model and German action theory (Frese & Zapf, 1994 ). For example, Holman et al. ( 2012 ) showed that blue collar workers in a vehicle manufacturer improved their learning strategies when being allotted job control, while solving complex problems. Similar results were found in a diary study (Niessen, Sonnentag, & Friederike, 2012 ), where job resources, such as having meaning on one’s job, allowed employees to maintain focus and explore new information, which then led to employees’ thriving, defined as a combination of learning and high levels of energy.

In the work context, different behaviors are valued, ranging from performance and adaptivity to proactivity (Griffin, Neal, & Parker, 2007 ). Taylor’s primary aim was to design jobs to increase job performance according to the scientific standards he established. Although performance has received less attention throughout the different classic job-design models, it is still considered crucial in job design research. Results are somewhat mixed. While meta-analyses show that a range of job resources (e.g., autonomy, skill or task variety, task significance, feedback) all relate positively to self-rated performance, only autonomy seems to relate to objective performance (Humphrey et al., 2007 ). Motivational and social factors like autonomy, task identity, feedback from the job, and social support are also important predictor of behaviors like absenteeism, while social aspects of work design, such as social support, feedback from others, and interdependence, prove to be most important for turnover intentions (Humphrey et al., 2007 ). Job resources like feedback and intrinsically motivating tasks also predict extra role behaviors, such as altruism, courtesy, conscientiousness, and civic virtue, while job demands like role ambiguity, role conflict, and task routinization are negatively related to these behaviors (Podskaoff, Mackenzie, Paine, & Bachrach, 2000 ).

Job design also affects adaptivity, or the degree employees cope well with the ongoing change and adversities in organizations (Griffin et al., 2007 ). For example, sportsmanship, or tolerating work-related inconveniences without complaining, is fostered when employees find their jobs inherently satisfying and receive feedback, while role problems likely forestall sportsmanship (Podskaoff et al., 2000 ).

More than just adapting to the rapid changes and the insecurity characterizing the contemporary labor market, employees are also required to proactively anticipate and act upon potential future opportunities (Griffin et al., 2007 ). Job design had not always been considered essential for employee proactivity (Anderson, De Dreu, & Nijstad, 2004 ), but recent views see job design—and most importantly autonomy and social support—as an important antecedent (Parker et al., 2006 ), which is confirmed by meta-analytic results (Tornau & Frese, 2013 ). Employees in enriched jobs are more inclined to be proactive than employees in jobs characterized by routinization and formalization (Marinova, Peng, Lorinkova, Van Dyne, & Chiaburu, 2015 ).

Job design is also an important moderator for proactivity, allowing proactive motivations to materialize in proactive behavior (Parker, Bindl, & Strauss, 2010 ). Meta-analyses, for example, suggest that employees don’t need autonomy to generate ideas, but require autonomy for idea implementation (Hammond, Neff, Farr, Schwall, & Zhao, 2011 ). As for job demands, the relations may be complex: while uncertainty relates negatively to feedback seeking (Anseel, Beatty, Shen, Lievens, & Sackett, 2015 ), job demands like complexity associate positively with proactive innovation (Hammond et al., 2011 ). Similar results are found at the within-person level. For example, civil servants are more likely to proactively try to improve procedures and introduce new ways of working when they are challenged by time pressure and situational constraints (Fritz & Sonnentag, 2007 ). Proactive behavior may also become a challenge in itself, because one has to plan his actions and invest additional hours or effort in the proactive behavior (Podsakoff, Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Maynes, & Spoelma, 2014 ). Job characteristics like job insecurity may also lead to counterproductive behaviors toward the organization (Van den Broeck et al., 2014 ) and also toward other employees. For example, Van den Broeck, Baillien, and De Witte ( 2011 ) found that job demands like workload are a risk factor for bullying behavior, while job resources like autonomy and supervisory support seem to reduce this risk. However, employees having both high job demands and high job resources were most at risk of becoming bullies at work.

Employee health and well-being, cognitions, attitudes, and behavior are treated as independent elements in the IWD model. They are, however, most likely to influence each other. High levels of well-being have, for example, been shown to relate to commitment and behavioral outcomes (Nahrgang et al., 2011 ). Moreover, thus far, mostly short-term outcomes at the level of the employee were mentioned, leaving outcomes that evolve only over time or develop at the organizational unexplored. Job design is, however, also related to several such outcomes, potentially through its impact on well-being, cognitions, attitudes, and behaviors. For example, job design also has an effect on one’s self-definition (Parker, Wall, & Jackson, 2016 ) and careers (Fried, Grant, Levi, Hadani, & Slowik, 2007 ). Longitudinal studies among more than 2,000 employees show that having high job demands and few opportunities for skill development or social support cause employees to retire early, even above and beyond their impact on mental and physical health (de Wind et al., 2014 ; de Wind, Geuskens, Ybema, Bongers, & van der Beek, 2015 ). Job design also leads to the financial success of the organization. High levels of job resources during one’s shift, for example, increase the financial returns in the fast food industry, as they contributed to the work engagement of the employees (Xanthopoulou, Bakker, Demerouti, & Schaufeli, 2009 ). High job resources equally increase the service climate within the hospitality sector, which then associates with customer loyalty (Salanova, Agut, & Peiró, 2005 ). These outcomes not only may be caused by job characteristics, but also feed into job characteristics (i.e., they have reciprocal relationships), and they may be dependent on employees’ personal characteristics.

Personal Characteristics

Several of the job-characteristics models have considered the role of personal characteristics within job design. Rightly so, as employee functioning is likely to be a function of both situation (i.e., to be job related) and person factors. Most attention with regard to the role of person factors has been paid to personal resources, which are defined as highly valued aspects, relating to resilience and contributing to individuals’ potential to successfully control and influence the environment (Hobfoll, Johnson, Ennis, & Jackson, 2003 ).

Several personal characteristics have been considered personal resources. Within the JCM, for example, growth-need strength can be seen as a personal resource, as are the critical psychological states of meaning, knowledge of results, and responsibility. Within Warr’s vitamin model, employees’ values are considered essential to how employees respond to certain contexts, while a host of personal resources have been studied in the realm of the JD-R model, ranging from hope and optimism to the core self-evaluations of self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, emotional stability, and locus of control (Van den Broeck et al., 2013 ).

In our view, personal resources may play at least three different roles in the job-design literature. First, they may moderate the impact of job characteristics on employee functioning (i.e., job resources as moderators). Conservation of resources Theory (COR), for example, assumes that having resources allows people to cope with demanding circumstances, so that personal resources may buffer the negative consequences (Hobfoll, 1989 ). In line with this view, employees endowed with self-esteem and optimism were found to experience less psychological distress when confronted with job demands like time pressure (Mäkangas & Kinnunen, 2003 ), while customer orientation buffers the association between job demands and burnout (Babakus, Yavas, & Ashill, 2009 ).

In addition to the buffering effect, job resources can also amplify the positive effects of resourceful job characteristics, as was also mentioned by Hackman and Oldham, as well as by Warr. Again following COR, employees holding high levels of personal resources in a resourceful environment may build resource caravans, which may then lead to low levels of stress and high performance (Hobfoll, 2002 ). More specifically, personal resources may boost the impact of job resources, because a fit between the personal resources and the job characteristics causes employees to pay more attention to the availability of the job characteristics, but also because they have more adaptive ways to act upon the job characteristics (Kristof-brown, Zimmerman, & Johnson, 2005 ). For example, employees who aim to develop themselves see more opportunities for development and may make better use of such opportunities, which then increases their well-being (Van den Broeck, Schreurs, Guenter, & van Emmerik, 2015 ; Van den Broeck, Van Ruysseveldt, Smulders, & De Witte, 2011 ).

Apart from the relatively straightforward moderating effects, personal resources may also influence the impact of job characteristics in a more complex way. Because of their boosting effect on job resources, personal resources may also enable employees to use their job resources better to offset the negative effects of job demands, leading to a three-way interaction between personal and job resources and job demands. For example, employees having an internal locus of control may make optimal use of the job control at their disposal to attenuate the effects of daily stressors, while for employees having an external locus of control, job control may not be put in practice and in some research actually predicted poorer well-being and health (Meier, Semmer, Elfering, & Jacobshagen, 2008 ; for a similar study, see Parker & Sprigg, 1999 ). Considering the curvilinear effects, personal resources may affect the tipping point at which increases in job characteristics stop being positive or even start to have negative consequences, so that employees with a high need for security may appreciate higher levels of role clarity than employees who are more adventurous (Warr, 1987 ). Overall, personal resources may allow employees to make better use of job resources, while dealing better with job demands, leading to different outcomes for employees working in the same jobs.

A second role of personal resources may be in explaining the relationships between job characteristics and their outcomes (i.e., personal resources as mediators). Hackman and Oldham suggested that the environment could influence employees’ psychological states, which then explains why job characteristics affect, for example, employee motivation and performance. According to JD-R scholars, this is true not only for the critical psychological states, but also for various personal resources. An important addition to the assumption is that not only may job resources add to psychological states, but also job demands can be assumed to take away employees’ energy and hinder their goal orientation, thereby decreasing employees’ personal resources (Hobfoll, 1989 ). In support of this, research shows that the same psychological resources may indeed explain the effects of both motivational and demanding job characteristics: While job resources lead to high levels of engagement and low levels of burnout through increased satisfaction of SDT’s basic needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, job demands hinder the experience of basic need satisfaction and therefore lead to higher levels of burnout and more counterproductive behavior (Van den Broeck, Suela, Vander Elst, Fischmann, Iliescu, & De Witte, 2014 ; Van den Broeck, Vansteenkiste, De Witte, & Lens, 2008 ). In exploring the mediating role of personal resources, future research may answer the call for more attention to the processes underpinning the relations between job characteristics and outcomes (Parker et al., 2001 ).

Finally, personal resources may serve as antecedents of job demands and job resources. This may be because managers provide more favorable job conditions to highly motivated employees (Rousseau, 2001 ), because such employees craft their job to include more motivational and less demanding characteristics (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001 ), or because resourceful employees appraise their job situation as more benign or challenging and less threatening (Folkman & Lazarus, 1985 ).

Notably, thus far, the job-design literature focuses on relatively changeable and positive personal characteristics. However, more stable personal characteristics may also play a role, as they may shape employees’ directedness to particular goals and thereby equally serve as antecedents and moderators of job characteristics (Barrick, Mount, & Li, 2013 ). The personality trait of neuroticism may, for example, cause employees to report higher job demands, while extroverted employees experience more job resources (Bakker et al., 2010 ). Moreover, recently, it was also shown that job characteristics may change employees’ personality (Wu, 2016 ). A final consideration is that particular personal aspects may also make employees more vulnerable to the negative impact of job demands or make it more difficult to benefit from positive aspects.

The job-design literature has a long history and continues to grow. Although some job-design scholars have argued there is nothing left to know about job design, new aspects are still unraveling and many aspects of the nature of job characteristics and their relationship with various outcomes, as well as the role of personal characteristics, remain underexplored. Because job design strongly associates with a host of outcomes and various jobs are still of low quality, job design still deserves scholarly and managerial attention. The integrative work design (IWD) model may assist in the process.

Further Reading

- Grant, A. M. (2008). The significance of task significance: Job performance effects, relational mechanisms, and boundary conditions . Journal of Applied Psychology , 93 (1), 108–124.

- Oldham, G. R. , & Fried, Y. (2016). Job design research and theory: Past, present and future . Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes , 136 , 20–35.

- Oldham, G. R. , & Hackman, J. R. (2010). Not what it was and not what it will be: The future of job design research . Journal of Organizational Behavior , 31 (2–3), 463–479.

- Allen, T. D. , Golden, T. D. , & Shockley, K. M. (2015). How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings . Psychological Science in the Public Interest , 16 (2), 40–68.

- Ambrose, M. L. , & Kulik, C. (1999). Old friends, new faces: Motivation research in the 1990. Journal of Management , 25 (3), 231–292.

- Anderson, N. , De Dreu, C. K. W. , & Nijstad, B. A. (2004). The routinization of innovation research: A constructively critical review of the state-of-the-science . Journal of Organizational Behavior , 25 (2), 147–173.

- Anseel, F. , Beatty, A. S. , Shen, W. , Lievens, F. , & Sackett, P. R. (2015). How are we doing after 30 years? A meta-analytic review of the antecedents and outcomes of feedback-seeking behavior . Journal of Management , 41 (1), 318–348.

- Axtell, C. M. , & Parker, S. K. (2003). Promoting role breadth self-efficacy through involvement, work redesign and training . Human Relations , 56 (1), 113–131.

- Babakus, E. , Yavas, U. , & Ashill, N. J. (2009). The role of customer orientation as a moderator of the job demand–burnout–performance relationship: A surface-level trait perspective . Journal of Retailing , 85 (4), 480–492.

- Backé, E.-M. , Seidler, A. , Latza, U. , Rossnagel, K. , & Schumann, B. (2012). The role of psychosocial stress at work for the development of cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review . International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health , 85 (1), 67–79.

- Bailey, D. E. , & Kurland, N. B. (2002). A review of telework research: Findings, new directions, and lessons for the study of modern work . Journal of Organizational Behavior , 23 , 383–400.

- Bakker, A. B. , Boyd, C. M. , Dollard, M. , Gillespie, N. , Winefield, A. H. , & Stough, C. (2010). The role of personality in the job demands-resources model: A study of Australian academic staff . Career Development International , 15 (7), 622–636.

- Bakker, A. B. , & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art . Journal of Managerial Psychology , 22 (3), 309–328.

- Bakker, A. B. , Demerouti, E. , & Sanz-Vergel, A. I. (2014). Burnout and work engagement: The JD–R approach . Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior , 1 (1), 389–411.

- Barley, S. R. , & Kunda, G. (2001). Bringing work back in . Organization Science , 12 (1), 76–95.

- Barrett, L. F. , Mesquita, B. , Ochsner, K. N. , & Gross, J. J. (2007). The experience of emotion . Annual Review of Psychology , 58 , 373–403.

- Barrick, M. R. , Mount, M. K. , & Li, N. (2013). The theory of purposeful work behavior: The role of personality, higher-order goals and job characteristics. Academy of Management Review , 38 (1), 132–153.

- Baumeister, R. F. , Bratslavsky, E. , Finkenauer, C. , & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good . Review of General Psychology , 5 (4), 323–370.

- Bernal, D. , Campos-Serna, J. , Tobias, A. , Vargas-Prada, S. , Benavides, F. G. , & Serra, C. (2015). Work-related psychosocial risk factors and musculoskeletal disorders in hospital nurses and nursing aides: A systematic review and meta-analysis . International Journal of Nursing Studies , 52 (2), 635–648.

- Campion, M. A. , Mumford, T. V. , Morgeson, F. P. , & Nahrgang, J. D. (2005). Work redesign: Eight obstacles and opportunities . Human Resource Management , 44 (4), 367–390.

- Campion, M. A. , & Thayer, P. W. (1985). Development and field evaluation of an interdisciplinary measure of job design . Journal of Applied Psychology , 70 (1), 29–43.

- Campion, M. A. , & Thayer, P. W. (1988). Job design: Approaches, outcomes and trade-offs. Organizational Dynamics , 15 (3), 66–79.

- Caplan, R. D. , Cobb, S. , French, J. R. R, Jr. , Harrison, R. V. , & Pinneau, S. R., Jr. (1975). Demands and worker health: Main effects and occupational differences . Washington, DC.: US Government Printing Office

- Cavanaugh, M. A. , Boswell, W. R. , Roehling, M. V. , & Boudreau, J. W. (2000). An empirical examination of self-reported work stress among U.S. managers . Journal of Applied Psychology , 85 (1), 65–74.

- Cordery, J. , & Parker, S. K. (2007). Organization of work. In P. F. Boxall , J. Purcell , & P. M. Wright (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of Human Resource management (Vol. 1, pp. 12–13). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cordery, J. L. , & Parker, S. K. (2012). Job and role design. In S. Kozlowski (Ed.), Oxford handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol 1, pp. 247–284). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Crawford, E. R. , Lepine, J. A. , & Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test . The Journal of Applied Psychology , 95 (5), 834–848.

- Das, B. , Shikdar, A. A. , & Winters, T. (2007). Workstation redesign for a repetitive drill press operation: A combined work design and ergonomics approach . Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing , 17 (4), 395–410.

- De Cooman, R. , Stynen, D. , Van den Broeck, A. , Sels, L. , & De Witte, H. (2013). How job characteristics relate to need satisfaction and autonomous motivation: Implications for work effort . Journal of Applied Social Psychology , 43 (6), 1342–1352.

- De Jonge, J. , & Dormann, C. (2003). The DISC model: Demand-induced strain compensation mechanisms in job stress. In M. F. Dollard , H. R. Winefield , & A. H. Winefield (Eds.), Occupational stress in the service professions (pp. 43–74). London: Taylor & Francis.

- De Jonge, J. , & Schaufeli, W. B. (1998). Job characteristics and employee well-being: A test of Warr’s vitamin model in health care workers using structural equation modelling . Journal of Organizational Behavior , 19 (4), 387–407.

- de Lange, A. H. , Taris, T. W. , Kompier, M. A. J. , Houtman, I. L. D. , & Bongers, P. M. (2003). “The very best of the millennium”: Longitudinal research and the demand-control (-support) model . Journal of Occupational Health Psychology , 8 (4), 282–305.

- de Wind, A. , Geuskens, G. A. , Ybema, J. F. , Blatter, B. M. , Burdorf, A. , Bongers, P. M. , et al. (2014). Health, job characteristics, skills, and social and financial factors in relation to early retirement—Results from a longitudinal study in the Netherlands . Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health , 40 (2), 186–194.

- de Wind, A. , Geuskens, G. A. , Ybema, J. F. , Bongers, P. M. , & van der Beek, A. J. (2015). The role of ability, motivation, and opportunity to work in the transition from work to early retirement—Testing and optimizing the Early Retirement Model . Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health , 41 (1), 24–35.

- De Witte, H. , Verhofstadt, E. , & Omey, E. (2007). Testing Karasek’s learning and strain hypotheses on young workers in their first job . Work & Stress , 21 (2), 131–141.

- Demerouti, E. , Bakker, A. B. , Nachreiner, F. , & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout . Journal of Applied Psychology , 86 (3), 499–512.

- Dollard, M. F. , & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Psychosocial safety climate as a precursor to conducive work environments, psychological health problems, and employee engagement . Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology , 83 (3), 579–599.

- Eller, N. H. , Netterstrøm, B. , Gyntelberg, F. , Kristensen, T. S. , Nielsen, F. , Steptoe, A. , et al. (2009). Work-related psychosocial factors and the development of ischemic heart disease . Cardiology in Review , 17 (2), 83–97.

- Folkman, S. , & Lazarus, R. S. (1985). If it changes it must be a process: Study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 48 (1), 150–170.

- Formazin, M. , Burr, H. , Aagestad, C. , Tynes, T. , Thorsen, S. V. , Perkio-Makela, M. , et al. (2014). Dimensional comparability of psychosocial working conditions as covered in European monitoring questionnaires . BMC Public Health , 14 , 1251.

- Frese, M. , Garst, H. , & Fay, D. (2007). Making things happen: Reciprocal relationships between work characteristics and personal initiative in a four-wave longitudinal structural equation model . The Journal of Applied Psychology , 92 (4), 1084–1102.

- Frese, M. , & Zapf, D. (1994). Action as the core of work psychology: A German approach. In H. C. Triandis , M. D. Dunnette , & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 4, pp. 271–340). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Fried, Y. , & Ferris, G. (1987). The validity of the job characteristics model: A review and meta-analysis . Personnel Psychology , 40 (2), 287–322.

- Fried, Y. , Grant, A. M. , Levi, A. S. , Hadani, M. , & Slowik, L. H. (2007). Job design in temporal context: A career dynamics perspective . Journal of Organizational Behavior , 28 (7), 911–927.

- Fried, Y. , Laurence, G. A. , Shirom, A. , Melamed, S. , Toker, S. , Berliner, S. , et al. (2013). The relationship between job enrichment and abdominal obesity: A longitudinal field study of apparently healthy individuals . Journal of Occupational Health Psychology , 18 (4), 458–468.

- Fritz, C. , & Sonnentag, S. (2007). Antecedents of day-level proactive behavior: A look at job stressors and positive affect during the workday . Journal of Management , 35 (1), 94–111.

- Gajendran, R. S. , & Harrison, D. A. (2007). The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: Meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences . The Journal of Applied Psychology , 92 (6), 1524–1541.

- Gordon, H. J. , Demerouti, E. , Bipp, T. , & Le Blanc, P. M. (2015). The Job Demands and Resources Decision Making (JD-R-DM) model . European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology , 24 (1), 44–58.

- Grant, A. M. (2007). Relational job design and the motivation to make a prosocial difference. Academy of Management Review , 32 (2), 393–417.

- Grant, A. M. , & Parker, S. K. (2009). Redesigning work design theories: The rise of relational and proactive perspectives . Academy of Management Annals , 3 (1), 317–375.

- Griffin, M. A. , Neal, A. , & Parker, S. K. (2007). A new model of work role performance: Positive behavior in uncertain and interdependent contexts. Academy of Management Journal , 50 (2), 327–347.

- Hackman, J. R. , & Oldham, G. R. (1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance , 16 , 250–279.

- Hakanen, J. J. , Bakker, A. B. , & Demerouti, E. (2005). How dentists cope with their job demands and stay engaged: The moderating role of job resources . European Journal of Oral Sciences , 113 (6), 479–487.

- Hammond, M. M. , Neff, N. L. , Farr, J. L. , Schwall, A. R. , & Zhao, X. (2011). Predictors of individual-level innovation at work: A meta-analysis . Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts , 5 (1), 90–105.

- Hansez, I. , & Chmiel, N. (2010). Safety behavior: Job demands, job resources, and perceived management commitment to safety . Journal of Occupational Health Psychology , 15 (3), 267–278.

- Hausser, J. A. , Mojzisch, A. , Niesel, M. , & Schulz-Hardt, S. (2010). Ten years on: A review of recent research on the Job Demand-Control (-Support) model and psychological well-being . Work and Stress , 24 (1), 1–35.

- Herzberg, F. (1968). One more time: How do you motivate employees? Harvard Business Review , 48 , 53–62.

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist , 44 (3), 513–524.

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation . Review of General Psychology , 6 (4), 307–324.

- Hobfoll, S. E. , Johnson, R. J. , Ennis, N. , & Jackson, A. P. (2003). Resource loss, resource gain, and emotional outcomes among inner city women . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 84 (3), 632–643.

- Holman, D. , Totterdell, P. , Axtell, C. , Stride, C. , Port, R. , Svensson, R. , & Zibarras, L. (2012). Job design and the employee innovation process: The mediating role of learning strategies . Journal of Business and Psychology , 27 , 177–191.

- Huang, Y. , Xu, S. , Hua, J. , Zhu, D. , Liu, C. , Hu, Y. , et al. (2015). Association between job strain and risk of incident stroke . Neurology , 85 , 1–7.

- Humphrey, S. E. , Nahrgang, J. D. , & Morgeson, F. P. (2007). Integrating motivational, social, and contextual work design features: A meta-analytic summary and theoretical extension of the work design literature . Journal of Applied Psychology , 92 (5), 1332–1356.

- Ilgen, D. R. , & Hollenbeck, J. R. (1992). The structure ofwork: Job design and roles. In M. D. Dunnette & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (2d ed., Vol. 2, pp. 165–207). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Jahoda, M. (1982). Employment and unemployment: A social-psychological analysis . Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Johns, G. , Xie, J. L. , & Gang, Y. (1992). Mediating and moderating effects in job design. Journal of Management , 18 (4), 657–676.