- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Writing Genres

- Short Story Writing

How to Write a Vignette

Last Updated: December 9, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was reviewed by Gerald Posner . Gerald Posner is an Author & Journalist based in Miami, Florida. With over 35 years of experience, he specializes in investigative journalism, nonfiction books, and editorials. He holds a law degree from UC College of the Law, San Francisco, and a BA in Political Science from the University of California-Berkeley. He’s the author of thirteen books, including several New York Times bestsellers, the winner of the Florida Book Award for General Nonfiction, and has been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in History. He was also shortlisted for the Best Business Book of 2020 by the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 556,744 times.

A vignette is a short piece of literature used to add depth or understanding to a story. The word “vignette” originates from the French word “vigne”, which means “little vine”. A vignette can be a “little vine” of a story, like a snapshot with words. A good vignette is short, to the point, and packed with emotions.

Preparing to Write the Vignette

- In terms of length, a vignette is typically 800-1000 words. But it can be as short as a few lines or under 500 words.

- A vignette will usually have 1-2 short scenes, moments, or impressions about a character, an idea, a theme, a setting, or an object.

- You can use the first second, or third point of view in a vignette. But most vignettes are told in just one point of view, instead of alternating points of view. Remember you only have a short amount of space on the page for the vignette. So don’t waste valuable time confusing your reader with many points of view.

- The vignette form can also be used by physicians to create a report on the status of a patient or a procedure. In this article, we will be focusing on a literary vignette, not a clinical vignette. [1] X Research source

- A vignette also does not require a main conflict or a resolution of a conflict. This freedom gives some vignettes an unfinished or unresolved tone. But unlike other traditional storytelling forms like the novel or the short story, a vignette does not have to tie up all the loose ends.

- In a vignette, you are not limited by a certain genre or style. So you can combine elements of horror and romance, or you can use poetry and prose in the same vignette.

- Feel free to use simple and minimal language, or lush, detailed prose.

- A vignette can also come in the form of a blog entry or even a Twitter post.

- Usually, shorter vignettes are more difficult to write, as you need to create an atmosphere in very few words and evoke a reaction from your reader.

- The publication Vine Leaves Journal publishes vignettes, both short and long. One of the submissions from their first issue is a two-line vignette by the poet Patricia Ranzoni, called “Flashback”: “ the softness from dialing the phone/is like lifting the lid to my music box. ”

- Charles Dickens uses longer vignettes or “sketches” in his novel “Sketches by Boz” to explore London scenes and people. [2] X Research source

- The writer Sandra Cisneros has a collection of vignettes called “The House on Mango Street”, narrated by a young Latina girl living in Chicago.

- For example, the two-line vignette by the poet Patricia Ranzoni is a successful piece because it is both simple and complex. Simple in that it describes the feeling you might get as you dial the number of someone you are excited to talk to. But complex in that the vignette ties the excitement of dialing a number to the excitement of lifting a music box. So the vignette combines two images to create one emotion. It also uses “softness” to describe dialing the phone, which also connects to the softness of the lining of a music box, or the soft music that plays from a music box. With just two lines, the vignette effectively creates a certain mood for the reader.

- In Cisneros’ “The House on Mango Street”, there is a vignette called “Boys & Girls”. It is a longer vignette, four paragraphs long, or around 1,000 words. But it sums up the young narrator’s emotion towards the boys and girls in her neighborhood, as well as her relationship with her sister, Nenny.

Someday I will have a best friend all my own. One I can tell my secrets to. One who will understand my jokes without my having to explain them. Until then I am a red balloon, a balloon tied to an anchor.

- The image of a “balloon tied to an anchor” adds color and texture to the vignette. The narrator’s feeling of being weighed down by her sister is perfectly summed up by the last image. So the reader is left with the feeling of being held down or tethered to someone, just like the narrator.

Brainstorming Ideas for the Vignette

- Take out a sheet of paper. Write your main topic or subject in the middle of the paper. For example, “Spring”.

- Moving out from the center, write down other words that pop into your mind that relate to “Spring”.

- For example, for “Spring”, you might write “flowers”, “rain”, “Spring break”, “new life”. Don’t worry about organizing the words as you write. Simply let the words flow around the main topic.

- Once you feel you have written enough words around the main topic, start to cluster the words. Draw a circle around words that relate to each other and draw a line between the circled words to connect them. Continue doing this with the other words. Some of the terms may end up uncircled, but these lone words can still be useful.

- Focus on how the words relate to the main topic. If you have clustered together several words that relate to “new life”, for example, maybe this may be a good approach for the vignette. Or if there are a lot of clustered words that focus on “flowers", this may be another way to approach “Spring.”

- Answer questions like: “I was surprised by…” or “I discovered…” For example, you may look over the clustered words and note “I was surprised by how often I mention my mother in relation to Spring.” Or, “I discovered I may want to write about how Spring means new life.”

- Take out a piece of paper, or open a new document on your computer. Write the main topic at the top of the paper. Then, set a time limit of 10 minutes and start the free-write. [4] X Trustworthy Source University of North Carolina Writing Center UNC's on-campus and online instructional service that provides assistance to students, faculty, and others during the writing process Go to source

- A good rule of thumb for the free-write is to not lift your pen from the paper, or your fingers from the keyboard. This means not re-reading the sentences you just wrote or going back over a line for spelling, grammar, or punctuation. If you feel you have run out of things to write down, write about your frustrations about not having anything else to say about the main topic.

- Stop writing once the timer is up. Read over the text. Though there may be some confusing or convoluted thoughts, there will also be sentences you may like or an insight that may be useful.

- Highlight or underline sentences or phrases you think may work in the vignette.

- Respond to each question with a phrase or sentence. For example, if your topic is “Spring”, you may answer Who? with “my mother and I in the garden”. You may answer When? with “A hot summer day in July when I was six years old.” You may answer Where? with “Miami, Florida.” You may answer Why? with “Because it was one of the happiest moments of my life.” And you may answer How? with “I was alone with my mother in the garden, without my sisters.”

- Look over your responses. Do you have more than one or two phrases for a certain question? Is there one question you had no answer for? If your answers reveal you know more about “where” and “why”, maybe this is where the strongest ideas for the vignette are.

Writing the Vignette

- For example, a vignette about “Spring” could describe a scene in the garden with your mother, among the flowers and trees. Or it could be in the form of a letter to your mother about that day in Spring, among the flowers and trees.

- You can also add figurative language to strengthen the vignette, such as similes, metaphors, alliteration, and personification. But use these sparingly and only when you feel like a simile or metaphor will highlight the rest of the vignette. [6] X Research source

- For example, the use of the red balloon attached to an anchor in Cisneros’ “Boys & Girls” is an effective use of figurative language. But it works well because the rest of the vignette uses simple language, so the image at the end of the vignette lingers with the reader.

- Look over the first two lines of the vignette. Does the vignette begin at the right moment? Is there a sense of urgency in the first two lines?

- Make sure your characters collide with each other very early in the vignette. See if you can edit the vignette so you set a scene in the least words possible.

Vignette Help

Community Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://www.acponline.org/education_recertification/education/program_directors/abstracts/prepare/clinvin_abs.htm

- ↑ http://www.gutenberg.org/files/882/882-h/882-h.htm

- ↑ http://writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/brainstorming/

- ↑ https://www.writerswrite.co.za/how-to-write-a-vignette/

About This Article

A vignette is a short piece of writing usually no more than 800 to 1000 words long. It focuses on a specific theme, such as spring or a garden, and can take different forms, including a letter or short story. Your vignette can concentrate on anything you like, whether it's an object, person, or a mood, like happiness or mourning. Vignettes are usually very descriptive, so you should try to use all of your senses when talking about something when you're writing one. Avoid including too much context or the back story about a character, since your vignette should create an atmosphere in the present moment it's focused on. Your vignette should also feel urgent when it's read through, so leave out unnecessary details or information that doesn't contribute to its main theme. For tips on how to plan out a structure for your vignette, keep reading! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Elizabeth Anderson

Jul 31, 2017

Did this article help you?

Nov 14, 2023

May 29, 2023

Robert Miller

Feb 11, 2018

Lynn Acheson

Nov 10, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Level up your tech skills and stay ahead of the curve

What Is A Vignette & How Do I Write One?

If you’ve ever wondered what a vignette is, read this post. We ask ‘What is a vignette?’ and show you how to write a vignette.

What Is A Vignette ?

A vignette (pronunciation: vin-YET) is a short scene in literature that is used to describe a moment in time. It is descriptive and creates an atmosphere around a character, an incident, an emotion, or a place.

Dictionary.com defines it as a ‘a small, graceful literary sketch.’

It is also known as a slice of life that gives the reader added information that is not integral to the plot of the story.

Vignette means ‘little vine’ and it is named after the decorative vine leaves that adorned nineteenth-century books. Like the vines that adorn the books, a vignette in literature adorns the story by enhancing a part of it.

A vignette can be described as a pause in the story . Authors usually use vignettes when they want to highlight a defining, emotional moment in a character’s life.

Is A Vignette A Flashback?

No. A flashback is generally seen as essential to a plot. A vignette is not. A vignette can look into the past, but it is not a flashback in the traditional sense.

How Long Is A Vignette ?

According to Masterclass , vignettes are short scenes within a larger story. They are (usually far) fewer than 1 000 words long.

Is A Vignette A Short Story?

No. A vignette does not follow a narrative with a beginning, middle, and end. It is more of a description or an observation. It is like looking through a magnifying glass for a moment. A short story features a viewpoint character who goes through some sort of conflict.

How To Write A Vignette

Think of it as a moment out of time.

- Use it when you want to give the reader a glimpse into a moment in a character’s life.

- Use it if you want to show something that is important, but not necessary to the plot.

- Use it when you want to create an atmosphere around a place or a character.

- Be descriptive .

- Use the senses .

- Use symbols.

- Leave the reader with a distinct visual impression.

Examples Of Vignettes:

A series of vignettes can be collected into one book:.

The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros is made up of vignettes that are ‘not quite poems and not quite full stories’. The character, ‘Esperanza narrates these vignettes in first-person present tense, focusing on her day-to-day activities but sometimes narrating sections that are a series of observations.’ ( via )

Naked Lunch by William S. Burroughs is ‘structured as a series of loosely connected vignettes. Burroughs stated that the chapters are intended to be read in any order. The reader follows the narration of junkie William Lee, who takes on various aliases, from the U.S. to Mexico, eventually to Tangier and the dreamlike Interzone.’ ( via )

Vignettes can be found within a book or a short story:

In In Our Time by Ernest Hemingway , the author uses a vignette to describe the death of a bullfighter, Maera. Hemingway writes: ‘Maera lay still, his head on his arms, his face in the sand. He felt warm and sticky from the bleeding. Each time he felt the horn coming. Sometimes the bull only bumped him with his head. Once the horn went all the way through him and he felt it go into the sand … Maera felt everything getting larger and larger and then smaller and smaller. Then it got larger and larger and larger and then smaller and smaller. Then everything commenced to run faster and faster as when they speed up a cinematograph film. Then he was dead.’ ( via )

Top Tip : Find out more about our workbooks and online courses in our shop .

© Amanda Patterson

If you liked this article , you may enjoy

- The 7 Qualities Of Compelling Character Motivations

- How To Write The Perfect Flashback

- 140 Words To Describe Mood In Fiction

- What Is Fantasy Fiction? Plus A Fantasy Book Title Generator

- 10 Memoir Mistakes Writers Should Avoid At All Costs

- What Is A Plot? – A Writer’s Resource

- Why You Need To Pay Attention If You’re A Writer

- Description , Featured Post , Literary Devices , Writing Tips from Amanda Patterson

5 thoughts on “What Is A Vignette & How Do I Write One?”

I’m curious as to whether a vignette might be a very short story? Or has it to be a part of a larger story and just an aside; a glimpse?

Dear Martin It could be a very short story, but generally it does not follow a narrative with a beginning, middle, and end. It is more of a description or an observation. It is like looking through a magnifying glass for a moment. It could work, but you will probably find the vignette morphing into more of a story as you go along.

We have added your question to the post (and answered it). Thank you so much for asking it.

Is vignette found mostly in any certain genre? Is it realism of some kind? Realism also focuses on describing minute details of a seemingly insignificant event.

Dear Rabia It is not restricted to any particular genre. We don’t think it has anything to do with realism. It is a moment in time that is described using symbols, senses, and imagery. It is a literary device.

Comments are closed.

© Writers Write 2022

A Writer's Notebook

The Essay Series # 2: The Vignette Essay

What is a vignette essay and how do you write one when you want to say the most with the fewest words of all..

The is Part 2 of The Essay Series .

Essays are perhaps the most naturally discursive of literary genres. They can start out in one place and end up in another. But if essays are about exploration, about investigation, arrival, and the formulation of thought, why then would we want to make them shorter? There’s short, as in the kind of thing you can read in under ten minutes, and then there is vignette short.

The vignette resists editorializing, explanation, explicit universalization, justification, and apology. It makes no excuses, and leaves no forwarding address. The vignette exists because it is enough. It offers no credentials, flashes no badge. If the full-length book is a marriage, the vignette is a one night stand.

What is accomplished, not just with this sort of brevity, but with this narrative choice? How can something so economical exist inside such a meandering genre? This week in the Essay Series I’m going to be talking about the vignette essay—what it is, who writes it, why to write it, where to publish it, and what it’s good for.

When I think about essays and their various forms, I am often reminded of Brian Dillon’s brilliant description in his book Essayism of Virginia Woolf’s Thunder at Wembley :

“Woolf's prose mimics the action of the storm, exploding delicately into flurries of image, sound and metaphor. As so often in her writing, you have a sense of the world becoming particulate, everything airborne and efflorescent or friable, turning to dust, powder, shingle, sand. This writing seems to release spores.”

Dust, powder, sand, spores. Words that spawn, shatter, crumble. We are often presented with an image of the essay as a vehicle for atomization —the atomization of vision, experience, emotion, and thought. We push the mess of existence in on one end, and out it comes on the other, transformed. The sloshing perfume of life is dispensed as a fine mist; the opaque solidity of the expected world is revealed to be, at its core, a lie, and for some reason this pleases us.

Since the 19th century, various forms of essays have emerged that lean into this scattered quality, this dispersal, this atomization. It is a modernist tendency. This can manifest in a number of ways, and one of those is with the vignette.

You may be surprised by the number of famous authors who have worked with and published nonfiction vignettes, either as standalone magazine pieces or in books. Writers as diverse as Charles Baudelaire, Ernest Hemingway, Margaret Atwood, Jamaica Kincaid, Kathleen Stewart, and Annie Dillard have all experimented with the form. Younger writers like J. Robert Lennon and Sherman Alexie have also written very short essays or vignettes.

Typically, a vignette essay opens on a scene, an image, a simple story, and then it closes again, without going anywhere else. Their short length is part of what makes them a vignette, but it’s not the whole story. They can be fewer than a hundred words, or more than five hundred, perhaps longer in some instances. The length matters less than how they function energetically . After reading this essay, you can go take a look at the essays on Brevity and you will see that some of them are vignettes, and some are not.

Vignettes are often about a single moment, or a string of moments. They bring the lights up on an object, a tableau, or a situation, and then dim them again. I’ve often seen people claim that vignettes have no narrative and no plot, but that isn’t strictly true. You’d be surprised by how much can happen in a vignette, but if it does happen, it tends to happen fast.

Take this example of a vignette by Ernest Hemingway:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to A Writer's Notebook to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.

Definition of Vignette

Vignette is a small impressionistic scene, an illustration, a descriptive passage, a short essay , a fiction or nonfiction work focusing on one particular moment; or giving an impression about an idea, character , setting , mood , aspect, or object . Vignette is neither a plot nor a full narrative description, but a carefully crafted verbal sketch that might be part of some larger work, or a complete description in itself.

Literally, vignette is a French word that means “little vine.” The printers, during the nineteenth-century, would decorate their title pages with drawings of looping vines. Hence, the derivation of this term is that source of drawings. Contemporary ideas from the scenes shown in television and film scripts also have influenced vignettes.

Examples of Vignette in Literature

Example #1: in our time (by ernest hemingway).

“Maera lay still, his head on his arms, his face in the sand. He felt warm and sticky from the bleeding. Each time he felt the horn coming. Sometimes the bull only bumped him with his head. Once the horn went all the way through him and he felt it go into the sand … Maera felt everything getting larger and larger and then smaller and smaller. Then it got larger and larger and larger and then smaller and smaller. Then everything commenced to run faster and faster as when they speed up a cinematograph film. Then he was dead.”

In this impressionistic sketch, the author gives an illustration of the character Maera, who is a bullfighter that dies from injures inflicted by a bull.

Example #2: An American Childhood (By Annie Dillard)

“Some boys taught me to play football. This was fine sport. You thought up a new strategy for every play and whispered it to the others. You went out for a pass, fooling everyone. Best, you got to throw yourself mightily at someone’s running legs … In winter , in the snow , there was neither baseball nor football, so the boys and I threw snowballs at passing cars. I got in trouble throwing snowballs, and have seldom been happier since.”

In this excerpt, Dillard has used her personal experiences while growing up in Pittsburgh, and describes the nature of American life. In this particular scene, she tells us how she learned to play football with the boys, and offering this incident of her teenage years.

Example #3: Railroads (By E. B. White)

“The strong streak of insanity in railroads, which accounts for a child’s instinctive feeling for them and for a man’s unashamed devotion to them, is congenital; there seems to be no reason to fear that any disturbing improvement in the railroads’ condition will set in … He gravely wrote ‘Providence’ in the proper space, and we experienced anew the reassurance that rail travel is unchanged and unchanging, and that it suits our temperament perfectly – a dash of lunacy, a sense of detachment, not much speed, and no altitude whatsoever.”

In this descriptive passage, White laments the bad condition of the passenger train industry in the state of Main, his home state, and worries for the future. He softens his complaints by going into past memories when he would ride as an adult.

Example #4: House on Mango Street (By Sandra Cisneros)

“Then Uncle Nacho is pulling and pulling my arm and it doesn’t matter how new the dress Mama bought is because my feet are ugly until my uncle who is a liar says, “You are the prettiest girl here, will you dance … My uncle and me bow and he walks me back in my thick shoes to my mother who is proud to be my mother. All night the boy who is a man watches me dance. He watched me dance.”

This whole story provides us a collection of vignettes. There are several passages with detailed descriptions about particular ideas or characters, such as this extract illustrating a dancing scene.

Function of Vignette

We often find vignettes in creative writing, as it provides description to achieve an artistic effect. However, we also see its usage in prose and poetry. Writers use this device to explore a character, and describe the setting of a scene. Vignettes give deeper understanding of texts, as writers densely pack them with imagery and symbolism . Besides, it increases writers’ language proficiency, as they use their language to its fullest by employing imagery to set a certain color and mood. Hence, the nature of vignettes is evocative and puts an impact on the senses of readers.

Post navigation

- Scriptwriting

What is a Vignette in Writing — Definition & Examples Explained

W hat is a vignette? The term has the potential to be confusing because it means slightly different depending on which story-telling medium is the topic of discussion. Even within filmmaking, the term can also be used to describe two completely different things. We will sort through this confusion and break down each meaning of ‘vignette.’ We will also take a look at some vignette writing examples in literature and film. Learning this specific writing technique might be exactly what your next project needs.

What is a Vignette

Let’s define vignette.

The vignette is one of many literary devices that relies on context . We will be focusing primarily on the definition of vignette as it relates to storytelling. But first, let’s quickly take a look at the other meaning of vignette.

In photography, filmmaking, and illustration, vignette refers to the darkening or, less commonly, the lightening of an image’s edges. Vignetting an image can provide it with additional contrast, value, and heighten the viewer’s focus on the center of the image.

If you encounter any other unfamiliar terms, our ultimate guide to filmmaking terminology is a handy resource for looking them up. Now let’s dig into the other meanings and variations of this concept.

Vignette Literary Definition

What is a vignette.

In literature, a vignette is a short piece of writing that does not have a beginning, middle, and end but rather focuses on a specific moment in time and the details within it.

In film, a vignette is a scene in a movie that can stand on its own. For example, the orgasm scene in When Harry Met Sally is often viewed and referenced on its own, separated from the rest of the film.

Vignettes do not tell complete stories on their own. They exist within broader stories, and multiple vignettes can add up to a cohesive whole. A vignette film is a complete cinematic work comprised of multiple episodes that can either weave together or remain separate throughout the course of the film.

Vignette Characteristics:

- Non-complete stories

It is important to distinguish a vignette film from an anthology film. An anthology film is made up of individual stories that are complete on their own. Each segment in an anthology film has a protagonist , a conflict , and a beginning, middle, and end.

Whereas in a vignette film, the individual segments are not complete on their own, but rather small pieces of an ultimate whole.

Films like Creepshow or Twilight Zone: The Movie are anthology films, not vignette films since their individual stories are self-contained and each follows a full plot arc.

What is a Vignette in Writing

How vignettes are used in storytelling.

A vignette in literature differs from a vignette in film. In traditional literature, a vignette is kept very short, typically under 1,000 words, and describes an isolated moment outside the passage of time. In a literary vignette, textures, emotions, and senses are described, but the plot does not move forward.

However, in a cinematic vignette, time is always passing, the plot may or may not advance, and the internal sensations of the character are not externalized, except in extremely rare instances of poetic visualization.

We will be focusing on how this device works in cinema moving forward. However, if you would like more information on how writers use them in literature, you can refer to the following video.

What is a vignette in literature?

A work of fiction can be built entirely out of vignettes, becoming a vignette film . Alternatively, one or more vignettes can be placed within an otherwise traditionally told narrative , such as in the aforementioned When Harry Met Sally scene or in many of Quentin Tarantino’s best films .

The KKK raid sequence in Django Unchained is a pivotal moment in the story. But the comedic “bag” scene that interrupts it is a perfect example of a humorous vignette. For more on this film, check out our analysis of the Django Unchained screenplay .

Comedic vignette example from Django Unchained

Both of these example scenes are diversions from the narrative. But they are so funny that we, as audience members, do not care that the plot has been momentarily paused.

Writing a Vignette

What to write a vignette about.

Most, but not all, vignette films share a few distinctive characteristics. First, they must have multiple plot threads. Whereas a traditional plot may follow a simple A-to-B trajectory, a vignette film is comprised of multiple narratives that each progress forward.

These separate plot threads may overlap, and the characters from one story may find themselves in another.

But this kind of crossover is optional, not mandatory.

These films are typically stocked with many characters of great or minor significance. While having a huge cast is not a requirement for a vignette film, having multiple protagonists is. Each vignette must have a distinct protagonist to follow, at least in part.

More often than not, these films are less plot-heavy than traditionally structured films. Slow, talky, and slice-of-life are all descriptors that are usually appropriate when describing a vignette film. Although some vignette films do opt for a more ‘active’ narrative style.

A segmented nature will be found in all vignette films. Jumping from story to story creates natural divisions in the narrative. Thus turning the plot into a series of connected segments rather than the singular through-line you might find in a traditionally structured film .

Each segment within a vignette film tends to be on the shorter side, but some films go against the grain in this regard.

One segment can be played through in its entirety before moving on to the next vignette. Or the film can jump from story to story, making a little progress on each plot thread with each segment before reaching an overall finale.

VIGNETTE WRITING EXAMPLES

Examples of vignette films.

Now, let’s take a look at some examples of successful vignette films. This format offers a chance at collaboration for filmmakers to team up and deliver an overall vision while also injecting their own signature flair.

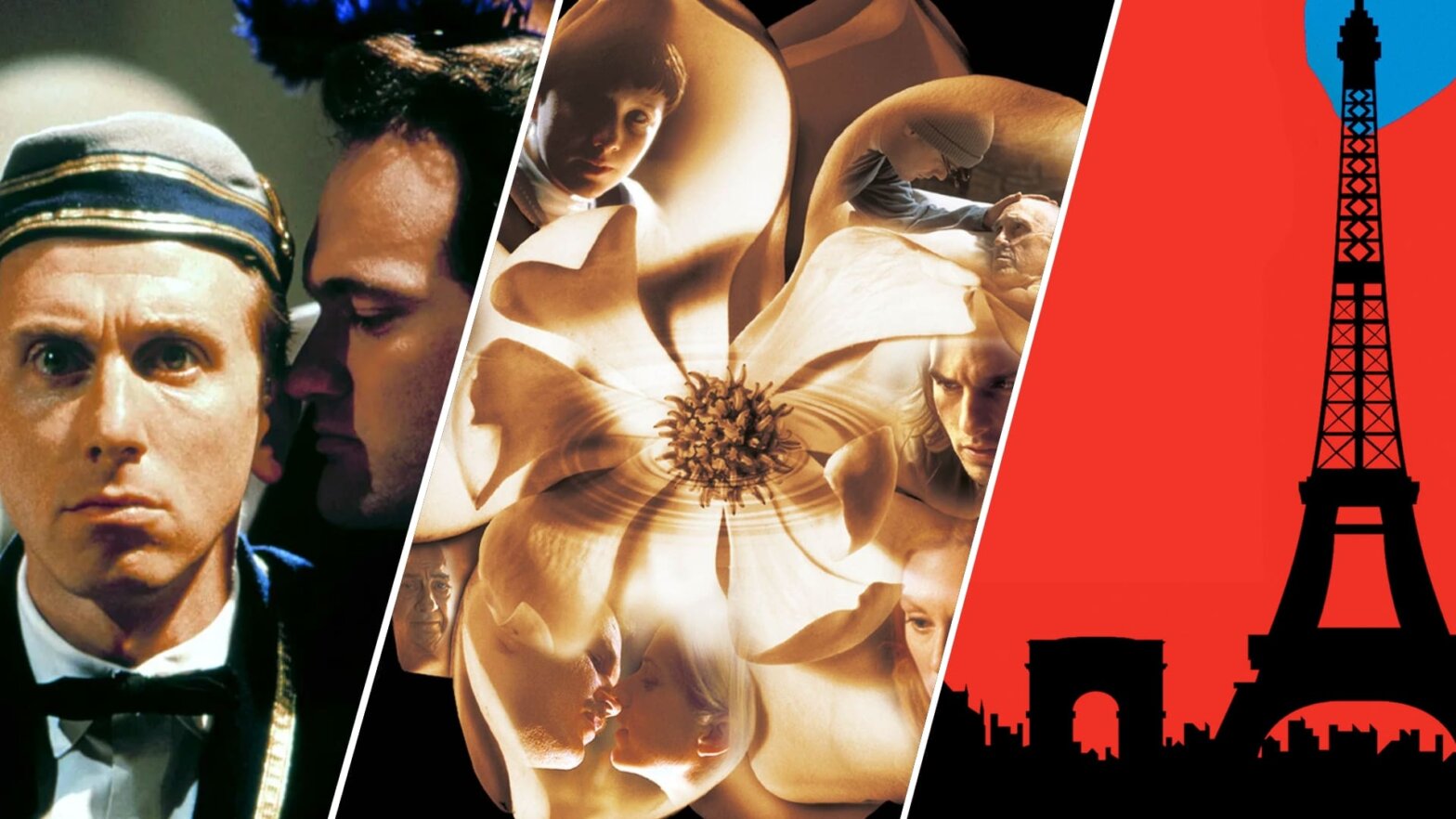

One vignette film that brought together the powerful directing team of Quentin Tarantino, Robert Rodriguez , Allison Anders, and Alexandre Rockwell is 1995’s Four Rooms .

Vignette Story • Four Rooms Trailer

One more example of a vignette story serving a collaboration between directors is Paris, je t’aime . This star-studded affair is comprised of 18 vignettes, each directed by a different filmmaker with such notable names in the mix as Alfonso Cuaron , Wes Craven , and the Coen Brothers .

Paris, je t’aime • A collection of cinematic episodes

Now, let’s take a look at some vignette film examples from directors with singular visions over multiple storylines.

Short Cuts from director Robert Altman is one of the finest examples of a vignette film. The script is adapted from the stories of Raymond Carver and explores a massive cast of 22 main characters all living in Los Angeles in the same moment in time. Each storyline is uniquely dramatic, and the subtle narrative overlaps serve to make the world feel vibrant and real.

Short Cuts • Trailer

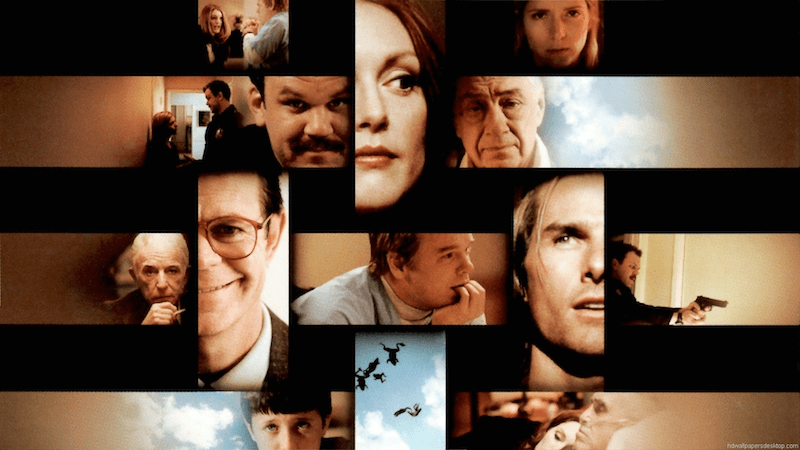

Auteur filmmaker Paul Thomas Anderson tackled the vignette film format in his third feature-film: Magnolia . The film is epic in scope while remaining deeply humanistic at its core, treating each and every character in the large cast with serious emotional depth.

The script is tightly woven, and the overlap between the characters of different stories is immensely satisfying when their connections finally come to light.

Magnolia • Visualizing the different segments

Another vignette film that is similar to Magnolia in many ways is the Oscar-winning drama Crash . Though Crash may be more high-profile, it is far less successful in crafting a cohesive vignette narrative with emotional resonance and staying power.

Wayne Wang’s Smoke is a great example of a laid-back, low-key vignette film. The movie centers around a cigar shop and the Brooklyn neighborhood surrounding it. As customers enter the shop, we learn about their personal stories and follow their dramatic potential.

A relaxed, natural atmosphere in Smoke

Jim Jarmusch is a filmmaker who has had great fun playing around with narrative structure over the years. His film Coffee and Cigarettes is built around 11 vignettes with only one thing in common: they are all set in coffee shops with different characters drinking coffee and smoking cigarettes.

Coffee and Cigarettes • Trailer

The various segments within Coffee and Cigarettes were filmed over the course of 17 years. In fact, the first segment was filmed in 1986, and the final feature film not being released until 2003.

Before releasing the full film, Jim Jarmusch released pieces of the film as a trilogy of short films called Coffee and Cigarettes I , II , and III between 1986 and 1993. And one additional perk of working in this format: isolated pieces can take on a new meaning when combined to form a whole.

Related Posts

- What is a Trope? With Movie Examples →

- Subtext-Rich Joker Script and Free Download →

- How to Write a Movie Script: Format and Examples →

What is Subtext?

We now have a comprehensive definition of vignette and plenty of examples to round out our understanding. Now it’s a good time to further our understanding of another literary device that pays dividends when used properly in a screenplay. Up next, let’s discuss subtext — what it is, and how to incorporate it into a story.

Up Next: Subtext Explained →

Write and produce your scripts all in one place..

Write and collaborate on your scripts FREE . Create script breakdowns, sides, schedules, storyboards, call sheets and more.

- Pricing & Plans

- Product Updates

- Featured On

- StudioBinder Partners

- The Ultimate Guide to Call Sheets (with FREE Call Sheet Template)

- How to Break Down a Script (with FREE Script Breakdown Sheet)

- The Only Shot List Template You Need — with Free Download

- Managing Your Film Budget Cashflow & PO Log (Free Template)

- A Better Film Crew List Template Booking Sheet

- Best Storyboard Softwares (with free Storyboard Templates)

- Movie Magic Scheduling

- Gorilla Software

- Storyboard That

A visual medium requires visual methods. Master the art of visual storytelling with our FREE video series on directing and filmmaking techniques.

We’re in a golden age of TV writing and development. More and more people are flocking to the small screen to find daily entertainment. So how can you break put from the pack and get your idea onto the small screen? We’re here to help.

- Making It: From Pre-Production to Screen

- VFX vs. CGI vs. SFX — Decoding the Debate

- What is a Freeze Frame — The Best Examples & Why They Work

- TV Script Format 101 — Examples of How to Format a TV Script

- Best Free Musical Movie Scripts Online (with PDF Downloads)

- What is Tragedy — Definition, Examples & Types Explained

- 1 Pinterest

What is a Vignette in Writing? Examples, Definitions, and How to Create Them

A v ign ette is a short descriptive narrative , usually humorous in tone , that paints a vivid picture of a scene , character , or situation . Common ly used in creative writing and journalism , v ign ettes can also be used to provide background information or set up a context for a story . Some examples are “ The old general store filled with dusty jars and rusty tools ,” or “ The couple danced in the moon light , laughing and singing “. Some examples from famous books are the opening of A Christmas Carol , or the start of The Great Gatsby .

The Essence of Vignettes

Vignettes can be compared to a scrumptious bite of chocolate cake. They may be small, but they pack a flavorful punch. Each little piece offers a snapshot of a larger world, engaging readers and capturing their imaginations. While these tasty morsels may not be as filling as a full-length novel, they can provide a satisfying literary experience.

The Purpose and Use of Vignettes

Vignettes are versatile tools that can serve a variety of purposes in writing. They can:

- Set the stage : By providing a glimpse into the setting, a vignette can draw readers into the story and make them feel as though they’re right there, experiencing the world with the characters.

- Character exploration : A vignette can offer insight into a character’s personality or backstory, allowing readers to connect with them on a deeper level.

- Create atmosphere : By focusing on the sensory details of a scene, a vignette can evoke a specific mood or atmosphere, immersing readers in the story’s world.

- Break up long narratives : In longer works, vignettes can serve as breaks between chapters or sections, giving readers a moment to pause and absorb the story so far.

Vignette Writing Tips

Crafting a vignette that captivates readers is no piece of cake, but with a few simple tips, writers can create vivid, engaging snapshots that leave readers craving more.

- Keep it short : Vignettes are meant to be brief, so avoid the temptation to ramble on. Aim for a few paragraphs or even just a single paragraph, depending on the desired effect.

- Focus on details : To make a scene come alive, hone in on specific sensory details. Describe sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and textures to create a rich, immersive experience.

- Show, don’t tell : Instead of simply stating information, use descriptive language and action to illustrate a scene or character.

- Embrace ambiguity : Vignettes often leave readers with unanswered questions, sparking their curiosity and encouraging them to imagine the rest of the story.

Examples of Vignettes in Literature

A christmas carol.

In Charles Dickens’ classic tale, the opening vignette sets the stage for the story that follows:

“Marley was dead: to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that. The register of his burial was signed by the clergyman, the clerk, the undertaker, and the chief mourner. Scrooge signed it: and Scrooge’s name was good upon ’Change, for anything he chose to put his hand to. Old Marley was as dead as a door-nail.”

This vignette introduces readers to the gloomy atmosphere and the cold-hearted character of Ebenezer Scrooge.

The Great Gatsby

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s iconic novel opens with a vignette that offers a glimpse into the narrator’s mindset:

“In my younger and more vulnerable years my father gave me some advice that I’ve been turning over in my mind ever since. ‘Whenever you feel like criticizing any one,’ he told me, ‘just remember that all the people in this world haven’t had the advantages that you’ve had.'”

By sharing this personal reflection, the vignette sets the tone for the themes of wealth, class, and privilege that permeate the novel.

Crafting Your Own Vignettes

Ready to take a stab at creating a delectable vignette? Here’s a step-by-step recipe to get started:

- Choose a subject: Decide on a character, setting, or situation to explore.

- Focus on the senses: Identify specific details that bring the subject to life.

- Write the scene: Begin crafting the vignette, incorporating the sensory details and focusing on showing, not telling. 4. Edit and refine: Review the vignette and make any necessary revisions to sharpen the imagery, tighten the language, and ensure it meets the desired length.

With practice and patience, the art of crafting delightful vignettes will become second nature. These bite-sized snapshots can add depth and intrigue to any story, making them invaluable tools for writers of all genres. So go ahead, indulge in some literary chocolate cake, and watch as readers savor every last morsel.

If you’re thirsty for more writing knowledge, head over here to learn all 74 literary devices .

About The Author

Related Posts

What is Anthimeria in Writing? Examples, Definitions, and How to Create Them

How Transportation Theory Can Help Your Writing Captivate Readers

What is Foil in Writing? Examples, Definitions, and How to Create Them

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Write a Vignette

I. What is a Vignette?

In literature, a vignette (pronounced vin-yet) is a short scene that captures a single moment or a defining detail about a character, idea, or other element of the story. Vignettes are mostly descriptive; in fact, they often include little or no plot detail. They are not stand-alone literary works, nor are they complete plots or narratives . Instead, vignettes are small parts of a larger work, and can only exist as pieces of a whole story.

Notably, the word vignette comes from the French vigne meaning “little vine,” and the term specifically arose for the small vines drawn on the pages of printed texts. These embellishments were commonly on title pages or a chapter’s first page, as can be seen on this page from the manuscript of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight :

So, much like the vines on the page, vignettes are little sections of a much bigger work.

II. Example of a Vignette

A vignette should be descriptive, whether it is about a setting, a character, or another aspect of a story. Read the passage below:

The room was warm and stuffy, but in a comforting way. It had the heavy but pleasing odor of musty books and old upholstery, with an overall air of ash and cedar from the fire that was always burning low the stone hearth, crackling and spitting quietly. There was a patchwork blanket resting over the side of the sunken but cozy couch, its squares tattered by the love and wear of time. A wooden clock ticked reliably on the wall.

The vignette above uses descriptive words to paint a literary picture of a single room. On its own and out of context, this passage does not serve much of a purpose. It leaves questions like: Where is the room? Who is seeing the room? Why are they there? Whose home is it? These questions about the larger story, aren’t answered with the description. This vignette’s purpose is to add further insight about the room and to help the audience understand the setting—it doesn’t tell a complete story on its own, but rather, it provides depth to the setting of some whole story.

III. Importance of Vignettes

Vignettes are important because of their descriptive nature—they can illuminate significant information, create depth of character, or provide insight about past events or circumstances. This helps create a more complete picture of the greater story. All stories rely on vignettes to provide detail. Without them, stories would be little more than plot outlines.

IV. Examples of Vignette in Literature

Vignettes can appear in different ways; they can be a few sentences in a novel or an important scene in a movie, but most importantly, they must be descriptive. Here are some examples of vignettes in a short story and a novel.

Much of 20 th century author Ernest Hemingway’s fame and renown can be attributed to his descriptive brilliance—he was a master of creating portraits of both setting and character, as he did in his short story “A Well-Lighted Café”:

It was very late and everyone had left the cafe except an old man who sat in the shadow the leaves of the tree made against the electric light. In the day time the street was dusty, but at night the dew settled the dust and the old man liked to sit late because he was deaf and now at night it was quiet and he felt the difference. The two waiters inside the cafe knew that the old man was a little drunk, and while he was a good client they knew that if he became too drunk he would leave without paying, so they kept watch on him.

Reading this opening passage creates a clear image and atmosphere in the reader’s mind—we can envision the shadow of the leaves in the light, we can feel the silence of the night, and we can imagine the intoxicated but quiet man sitting alone at the café. Hemingway doesn’t introduce the dialogue—which makes up the majority of the story—until he has employed a vignette that develops the atmosphere and feelings that he needs for the story’s success.

Sandra Cisneros’s novel The House on Mango Street is a series of vignettes that together create a portrait of life at “the house on Mango Street,” which is the protagonist’s childhood home in a low income Latino neighborhood in Chicago. A girl named Esperanza narrates the story, and each vignette in the book captures moments, memories, and observations of her everyday life on Mango Street—

The house on Mango Street is ours, and we don’t have to pay rent to anybody, or share the yard with the people downstairs, or be careful not to make too much noise, and there isn’t a landlord banging on the ceiling with a broom. But even so, it’s not the house we’d thought we’d get.

The selection is a vignette about Esperanza’s perception of the house on Mango Street. Prior to this passage Esperanza has explained that they bought the house (it isn’t a rental). The passage above provides insight to Esperanza’s thoughts about the house, which are important for the entire story. The reader knows that although the house is their own, it’s not the family’s first choice—Esperanza is grateful but disappointed at heart. This vignette exists as a piece of insight for the development of the overall image of life on Mango Street, but it is not a full story itself.

V. Examples of Vignette in Pop Culture

Here are some examples of vignettes showing defining moments of characters in TV and film.

The Netflix drama and comedy series Orange is the New Black uses many vignettes for characterization of the female prisoners. The vignettes are most notably in the form of flashbacks and capture relative or defining moments in the prisoners’ lives and situations that led to their imprisonment. In the show, there is a character and inmate named Suzanne who is also known as “Crazy Eyes” because of her both her erratic behavior and her wide, intense eyes.

Her flashback is a sleepover party that provides deeper insight about Suzanne’s character. Importantly, it shows that she has always been eccentric, unstable, and as a result has always been an outcast that people struggle to connect with. This remains true in prison, as exemplified by her unkind nickname.

The closing scene of the classic film Planet of the Apes is an excellent example of a vignette, particularly one that provides insight about setting —

Here, the protagonist George discovers that the planet he has been on is actually Earth, in the future, but it has been completely destroyed. Before this moment, it was unclear when or where George is in space and time, respectively. However, this vignette provides the audience (and George) with information that changes the whole perspective of the plot. On its own, this scene is irrelevant; however, it is a very relevant part of a much larger story.

VI. Related Terms

A sketch is a short piece of writing—shorter than a short story—that contains little or no plot. It mainly describes people or places, and does not have to be part of a larger story. For example, a sketch of a location, like a vacation destination, would describe its most notable details. This is the primary difference between a sketch and a vignette, because a vignette is always part of a larger story or work.

Vignette (Photography)

In photography, a vignette technique and style in which a photo’s edges are blurred and/or darkened to bring the focus in on a certain portion of an image or scene. The term is similar to the literary definition of vignette in that it captures and emphasizes a small part of a bigger picture.

VII. Conclusion

In conclusion, a vignette is a critical tool in both creative fiction and creative nonfiction because it adds depth and support to a piece of literature. It is a powerful descriptive device that can bring insight about a setting, character, or idea that adds to the overall understanding of a story.

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

School of Writing, Literature, and Film

- BA in English

- BA in Creative Writing

- About Film Studies

- Film Faculty

- Minor in Film Studies

- Film Studies at Work

- Minor in English

- Minor in Writing

- Minor in Applied Journalism

- Scientific, Technical, and Professional Communication Certificate

- Academic Advising

- Student Resources

- Scholarships

- MA in English

- MFA in Creative Writing

- Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies (MAIS)

- Low Residency MFA in Creative Writing

- Undergraduate Course Descriptions

- Graduate Course Descriptions

- Faculty & Staff Directory

- Faculty by Fields of Focus

- Faculty Notes Submission Form

- Promoting Your Research

- 2024 Spring Newsletter

- Commitment to DEI

- Twitter News Feed

- 2022 Spring Newsletter

- OSU - University of Warsaw Faculty Exchange Program

- SWLF Media Channel

- Student Work

- View All Events

- The Stone Award

- Conference for Antiracist Teaching, Language and Assessment

- Continuing Education

- Alumni Notes

- Featured Alumni

- Donor Information

- Support SWLF

What is a Vignette? || Oregon State Guide to Literary Terms

"what is a vignette": a literary guide for english students and teachers.

View the full series: The Oregon State Guide to English Literary Terms

- Guide to Literary Terms

- BA in English Degree

- BA in Creative Writing Degree

- OSU Admissions Info

"What is a Vignette?" Transcript (English Subtitles Available in Video)

By Kristin Griffin , Oregon State Creative Writing Senior Lecturer

28 August 2023

If you’ve ever been to a natural history museum, you’ll know that a big part of the experience are the dioramas. From one gallery to the next you might happen upon a herd of zebras milling around a watering hole in the African bush, or a pack of wolves frozen mid-hunt in the snowy Siberian woods. These dioramas—these highly detailed, thoughtfully composed moments in time—are vignettes.

wolf_diarama.jpg

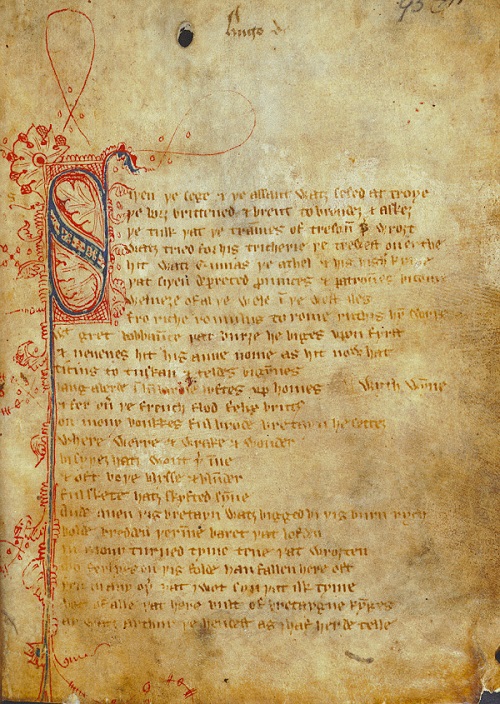

Another place you’re likely to find a vignette or two? Wes Anderson movies. There’s a great example in ‘The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou,’ where we’re shown a cross section of the research vessel Belafonte where much of the movie takes place. The camera pans across different levels of the boat and we see various characters going about their business in real-time: the chef icing a cake in the kitchen, the female lead taking notes in the library, the male lead fishing from the bridge. The sequence doesn’t move the plot forward—it’s not active in that way—but it’s beautiful to watch and enhances the sensory experience of the film.

life_aquatic_vignette.jpg

These two examples—the natural history museum diorama, the Belafonte sequence—show us a lot about what a vignette is and its purpose in storytelling. In literary terms, a vignette is a short, descriptive passage that captures a moment in time. It can enhance a mood , develop a character, or describe a setting , but one thing a vignette doesn’t do is move along a plot. It’s no accident that the term vignette comes from a French word meaning “little vine,” referencing the vine-like illustrations that decorated the margins of old books. Vignettes can differ from, say, a flashback (which we explored in another literary terms video recorded by someone you might recognize) because flashbacks are solely about taking a reader into the past, whereas vignettes can occur anytime. Vignettes also differ from anecdotes in that anecdotes, while short too, are complete stories with a beginning, middle, and end whereas the most you’ll ever get from a vignette is a glimpse.

vignette_definition.jpg

You’ll notice that vignettes are everywhere once you know what to look for. One of my favorite examples is Sandra Cisneros’ book The House on Mango Street . It’s a novel-length work composed of a series of non-linear vignettes that consider common themes , familiar characters, and recognizable settings. Here’s a vignette I love from early on in the book. Page six. It’s called ‘Hairs’: “Everybody in our family has different hair. My papa’s hair is like a broom, all up in the air. And me, my hair is lazy. It never obeys barrettes or bands. Carlos’ hair is thick and straight. He doesn’t need to comb it. Nenny’s hair is slippery – slides out of your hand. And Kiki, who is youngest, has hair like fur. But my mother’s hair, my mother’s hair, like little rosettes, like little candy circles all curly and pretty because she pinned it in pincurls all day, sweet to put your nose into when she is holding you, holding you and you feel safe, is the warm smell of bread before you bake it, is the smell when she makes room for you on her side of the bed still warm with her skin, and you sleep near her, the rain outside falling and Papa snoring. The snoring, the rain, and Mama’s hair that smells like bread.”

cisneros_vignette.jpg

This vignette does so much work to characterize the family as a unit and as individuals. Things come to Carlos. Nenny is exasperating. Little Kiki is soft and young. The speaker’s hair has a mind of its own. A little lazy, perhaps, a little disobedient. The narrator doesn’t seem sure. That makes sense, because the overarching movement of the book is around her coming to understand herself. And then there’s that beautiful, lush, almost stream-of-consciousness passage about her mother where the short sentences in the first paragraph break open into something looser. Her mother’s hair is “like little rosettes,” the speaker says. “Like little candy circles.” Sweetness and delight. The center of the family with a paragraph all to herself. Remember, a little earlier in this video, when I said that vignettes can enhance a mood, develop a character, or describe a setting? It’s clear in the vignette I just discussed that it develops characters, but does it reveal aspects of mood or setting too? What do you think? Let me know in the comments section of the video.

Want to cite this?

MLA Citation: Griffin, Kristin. "What is a Vignette?" Oregon State Guide to English Literary Terms, 28 Aug. 2023, Oregon State University, https://liberalarts.oregonstate.edu/wlf/what-vignette-oregon-state-guide-literary-terms. Accessed [insert date].

Interested in more video lessons? View the full series:

The oregon state guide to english literary terms, contact info.

Email: [email protected]

College of Liberal Arts Student Services 214 Bexell Hall 541-737-0561

Deans Office 200 Bexell Hall 541-737-4582

Corvallis, OR 97331-8600

liberalartsosu liberalartsosu liberalartsosu liberalartsosu CLA LinkedIn

- Dean's Office

- Faculty & Staff Resources

- Research Support

- Featured Stories

- Undergraduate Students

- Transfer Students

- Graduate Students

- Career Services

- Internships

- Financial Aid

- Honors Student Profiles

- Degrees and Programs

- Centers and Initiatives

- School of Communication

- School of History, Philosophy and Religion

- School of Language, Culture and Society

- School of Psychological Science

- School of Public Policy

- School of Visual, Performing and Design Arts

- School of Writing, Literature and Film

- Give to CLA

How To Write A Vignette

November 19, 2020

Short stories, poems, and vignettes, like their long-form counterparts, can be used as literary devices. Their brevity makes them ideal for exploring and expressing a specific detail or moment in a larger story. In the context of fiction writing, vignettes can be used to establish a setting, describe a character, or provide a snapshot of a moment in time. The use of vignettes in nonfiction allows the writer to focus on a single topic in detail. Whatever your purpose, here are steps for how to write a vignette that will get you started in the right direction.

Master the art of the hook

Writing vignettes that suck readers in so that they want to learn more isn’t as simple as telling the reader the surface details, but rather can be quite a task. You’ll need to set the scene carefully to give your reader maximum context, which will let you get to the real meat — the details of action, conflict, and emotion — quicker. Creating a hook is a good way to prepare the reader for what lies ahead, and it can happen in a number of ways. You can choose a relatable setting that will resonant with a significant number of readers, like a wedding where you’re able to showcase the groom’s neuroses along with the bride’s disdain for mudroom weddings. Or you can use a hook at the beginning of the vignette to give the reader a glimpse of the world and allow them to practice familiarizing themselves with an environment — which will allow you to jump right into the scene space with the elements you’ve brainstormed and culled from your memory.

Writing a great hook also helps your vignette appear even shorter than it is. Keep in mind that the shorter your summation, the better chance you have as a writer to not flesh out unnecessary details. Read your summaries aloud to hear how the words will roll off your readers’ tongues. The hook should be just long enough to grab a reader’s attention and not so long that it detracts from the forefront of your vignette. It can also help for you to use particular details that generate interest by giving the reader a taste of the full story. Don’t bog the beginning down with too many details, but give the reader a sense of the characters, conflict, or emotional tone so that they’ll feel the need to learn more.

Keep it focused

Vignettes are all about providing context for your character and their surroundings, but the best way to give your reader that context is to keep things focused. The scenes in the vignette should all fit together into a cohesive whole, while also being distinct on their own. As you write, think about the continuum from slice of life to author intrusion. Can you seamlessly weave back and forth between showing your character’s world and coloring it in for the reader, or must it be a choppy, disjointed looking experience? Are the details capturing the essence of how you want the reader to feel about the character and their situation, or are they just on-the-fly inferences you’re filling in about what’s going on? Completing a successful vignette means making sure there’s no tension and/or conflict in each scene on their own, and also a strong cumulative effect that paints a complete picture for the reader.

Make each scene count. If you have ten scenes or less, you can have them all be full of tension or conflict. If you have more scenes though, you’ll probably need to narrow it down and focus it more on creating a sense of cohesion across the vignette as a whole. A great way to do this is to create a few moments of tension or conflict that foreshadow a conflict that would affect the entirety of the story even more, and have a cumulative overall impact on the reader. This makes your vignette cohesive and pulls in all its disparate elements while also providing a hook at the end for a reason to come back again.

Don’t have backstory

A vignette generally takes place over just one moment, so beware of describing a character’s entire background, either in your vignette or in the scene preceding it. If the characters have come from other parts of the story, save their introduction for the scene following the vignette. Feel free to have other characters appear or reappear later as plot developments warrant. Do remember to make your vignette pinpoint-specific and include specific setting descriptions to paint a mental image for your reader. But remember, this is a short piece of writing, so don’t waste the limited space for overindulgence.

Vignettes have small ordinary moments that reveal an extraordinary state of existence. So you should choose ordinary circumstances to present them. Invite your readers to notice the smaller moments or sights or sounds that most people take for granted. In spending just a moment or two with a character, you can provide a unique perspective on ordinary life. Play with the time frame. Let the reader see the past to bring an event up to the present moment. Try to end on a twist.

State that theme clearly and boldly

Because a vignette is a small work excerpt, you need to make sure that the big picture of a theme is clear. You should write vignettes that delve into the depths of certain characters and emotions. Just as the theme is larger than conflict, so is the word vignette. It should highlight particular characters, giving them a sense of identity as the story goes along and as it moves through its three-part, five-act, or seven-chapter structure.

The character in vignettes is often under a microscope because the reader isn’t sure about her story. She must be shrouded in mystery, but in a way that also provides the reader with the required props for the comprehension of random vignettes. The vignette character, then, is typically a subject that lends itself to exploration or enhancement. She should serve as a paragon, but become better known as the author progresses story events. The springboards from which some of a vignette character’s identity comes should never be the harbinger of the story’s climax.

Balance theme with all characters and plot threads

Vignettes should stand alone from the world of a story or novel, but remain rooted enough that they add texture to a narrative. To truly learn how to write a vignette, you should study some examples of the best vignette examples that you can find. Do these vignettes complement or subvert the protagonist or main character of the story? Many times, the author might use a vignette in a larger scene, to provide a useful backdrop that completes the snippet like a portrait fits into a mural.

As an example of wrapping a vignette into a longer narrative, take a look at How to Dig a Hole to China by Katherine Roeder. This longer narrative provides a plot-oriented vignette, outlining a two-page procedure for tunneling to the other side of the world. The vignette begins light, with the example of a boy asking Dad what a hole to China would even look like. The length intensifies as the section of the instructions progresses. The sudden appearance of spades, shovels, and water-filled dustpans, along with misdirections about weight and falling, creates humor that adeptly juxtaposes with the possible physical ramifications of this lengthy project. Read the simple prescription once, and then imagine the ramifications of following it. If a chapter of fiction followed the physical labor necessary for the father and son to build this tunnel, it would leave very little physical or mental room for anything else, making this one of the most subversive—and hilarious—two-pages in fiction.

Think in terms of montage

In a vignette, the details that fill out the story come second to building a strong character and emotion. You don’t want to aim for naturalistic language, because with such a small space, every word becomes important. Vignettes are like kinetic action sequences in film that condense up into a single freeze frame of a moment. Use this quality to your advantage, to fire off a quick piece that doesn’t waste words.

Consider the sentence, “The fire was beautiful, like the great lion roaring at the world,” and think of how easy that would be to expand on into something complete, right? The image of the fiery lion alone could support an essay. However, the author Yoko Tawada uses that sentence to anchor a micro-story, a vignette, in the small Japanese collection Silence . She expands the original “like the lion roaring” part into an entire paragraph of the fire’s roar, heat, and the characters’ responses. Then she ends with the simple, extreme image of the animal itself.

Vignettes take us out of reality and give us a choice vantage point on another person’s life. Start by taking snapshots of your character’s life that show conflict and resolution. Like an actual camera, these frozen slices can zoom in, leaving out unnecessary detail and cutting to show the true face of conflict. As a result, vignettes feel meaningful and intense in a way that many longer stories fail to be. They ask questions, rather than explaining or carrying out a chain of events.

Learn it backwards and forwards

If you don’t want to seem sheerly incompetent, remember to “show early, show often.” The reader sees the vignette being created before his or her very eyes, rather than being told about it or eavesdropping on an important conversation. The vignette is written in chronological order, instead of in “montage” form, and it has action rather than being entirely dialogue-driven. No matter how literary you think your book is, you cannot have characters sitting around and snapping quips at each other. It won’t work. Remember to put your story in the past, present or future — the vignette isn’t a flash-forward, backstory or flash-sideways, even if there’s the inevitable premonition or instance of déjà vu. The vignette opens in the present and stays in the same place, even if the narrator is reflecting upon the past. Without the aid of melodrama, without sudden revelation and without intent on your part, the reader will still “feel” the truth in the vignette. It should be pregnant with emotion and etched in the mind of the reader as if they witnessed it themselves.

Choose the point-of-view of the narrator carefully. A small tale told by a giant – or vice versa – will put the reader in a different position. You might choose to tell your vignette in the third person, so that you can speak directly to your reader and frame the action just so. Or, you might tell it in the first person to allow perspective and empathy for your narrator — or maybe even for his or her antagonist, if the vignette is done from their point-of-view. In the second paragraph, the reader sees a general idea of who the character is, and what they’re like. Is there something that makes the character “iconic?” Is their amnesia or a curse, or an illness or disability? Do they have a measurable characteristic flaw, need, or other “hook” in their personality? Do they feel or react to things a certain way — and would the reader recognize it?

Use language and writing devices

Ask yourself a series of questions about how you want your vignette to read, including what it will be framed/introduced by, what purpose it will serve, what length and tone it will have, and whether it will have multiple parts or set scenes. Decide what tone your vignette will have — is it somber and tender, or light and playful? Does it serve a structural or expository purpose, or should it be used to introduce a specific tone? Some ideas for framing a vignette might be to use dialogue, a letter, or something that the characters have created, as a means for introducing the story.

Then, look back on your story and see where points could use a little more definition or description. Think about what the characters are doing when your story takes place, and whether they are in locations that are easy to describe. When you’re done with that, start to outline your vignette. Decide what it will be made up of — will it be one scene or multiple scenes, a paragraph long, or anything else? Then determine what tone, purpose, and setting you want your vignette to have, and the way you want to write it, based on the questions you decided on in paragraph one.

Include dialogue

Vignettes are much shorter than works of fiction, so the brevity forces you to zero in on the most important details. This doesn’t mean that you can’t add extras, however. Vignettes benefit from including dialogue, and you can also lean on sensory detail and metaphor to make complicated thoughts or feelings accessible. Pay attention to word choices as well, since big, bold language makes vignettes easier to read.

Your goal with a vignette is to start strong and finish strong and ensure there’s a good balance between dialog and description. While you may start a vignette with an intimate observation, you should end it with a solid plot point or moral lesson that makes the reader want to keep on reading. Like any other type of writing, you should write your vignette a bit unevenly. But if you’re looking for a way to cut edge in the right direction, be sure to invest extra time into your introduction, to make it feel like an exciting invitation into the rest of the piece.

Vignettes are important in that they provide insight into their host text. While the majority of your vignette should be able to stand alone, you may want to provide links to a larger work, as well as a general overview of the chapter, character, or story that this vignette serves. In other words, once you’ve written your vignette, make sure it reads well on its own, but spend a little time researching what it links. What’s the scene about? Why does this scene need to be told? What does it mean in terms of plot or mood? Do you provide answers to these questions, or at least mention that they exist? Now that you’re ready to write a vignette, what will you write first?

Other Posts You Might Like:

- 17 Tips on Writing Your First Simple Poem

- How To Write A Strong Female Personality

- How To Write A Tragedy

Join the Commaful Storytelling Community

Commaful takes everything you love about stories and makes it a bite-sized, on-the-go experience. Fanfiction? Poetry? Short stories? You’ll find it all!

Definition and Examples of Vignettes in Prose

Glossary of Grammatical and Rhetorical Terms

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

In composition , a vignette is a verbal sketch—a brief essay or story or any carefully crafted short work of prose . Sometimes called a slice of life .

A vignette may be either fiction or nonfiction , either a piece that's complete in itself or one part of a larger work.

In their book Studying Children in Context (1998), M. Elizabeth Graue and Daniel J. Walsh characterize vignettes as "crystallizations that are developed for retelling." Vignettes, they say, "put ideas in concrete context , allowing us to see how abstract notions play out in lived experience."

The term vignette ( adapted from a word in Middle French meaning "vine") referred originally to a decorative design used in books and manuscripts. The term gained its literary sense in the late 19th century.

See Examples and Observations below. Also, see:

- Character (Genre) and Character Sketch

- Composing a Character Sketch

- Creative Nonfiction

- Description

- How to Write a Descriptive Paragraph

Examples of Vignettes

- "By the Railway Side" by Alice Meynell

- Eudora Welty's Sketch of Miss Duling

- Evan S. Connell's Narrative Sketch of Mrs. Bridge

- Harry Crews' Sketch of His Stepfather

- Hemingway's Use of Repetition

- "My Home of Yesteryear": A Student's Descriptive Essay

Examples and Observations

- Composing Vignettes - "There are no hard-and-fast guidelines for writing a vignette , though some may prescribe that the content should contain sufficient descriptive detail , analytic commentary, critical or evaluative perspectives, and so forth. But literary writing is a creative enterprise, and the vignette offers the researcher an opportunity to venture away from traditional scholarly discourse and into evocative prose that remains firmly rooted in the data but is not a slave to it." (Matthew B. Miles, A. Michael Huberman, and Johnny Saldana, Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook , 3rd ed. Sage, 2014) - "If one is writing a vignette about a dearly beloved Volkswagen, one will probably play down the general characteristics which it shares with all VW's and focus instead on its peculiarities—the way it coughs on cold mornings, the time it climbed an icy hill when all the other cars had stalled, etc." (Noretta Koertge, "Rational Reconstructions." Essays in Memory of Imre Lakatos , ed. by Robert S. Cohen et al. Springer, 1976)

- E.B. White's Vignettes "[In his early 'casuals' for The New Yorker magazine] E.B. White focused on an unobserved tableau or vignette : a janitor polishing a fireplug with liquid from a Gordon's Gin bottle, an unemployed man idling on the street, an old drunk on the subway, noises of New York City, a fantasy drawn from elements observed from an apartment window. As he wrote to his brother Stanley, these were 'the small things of the day,' 'the trivial matters of the heart,' 'the inconsequential but near things of this living,' the 'little capsule[s] of truth' continually important as the subtext of White's writing. "The 'faint squeak of mortality' he listened for sounded particularly in the casuals in which White used himself as a central character. The persona varies from piece to piece, but usually the first-person narrator is someone struggling with embarrassment or confusion over trivial events." (Robert L. Root, Jr., E.B. White: The Emergence of an Essayist . University of Iowa Press, 1999)