- Arts & Culture

- Civic Engagement

- Economic Development

- Environment

- Human Rights

- Social Services

- Water & Sanitation

- Foundations

- Nonprofits & NGOs

- Social Enterprise

- Collaboration

- Design Thinking

- Impact Investing

- Measurement & Evaluation

- Organizational Development

- Philanthropy & Funding

- Current Issue

- Sponsored Supplements

- Global Editions

- In-Depth Series

- Stanford PACS

- Submission Guidelines

A Better Education for All During—and After—the COVID-19 Pandemic

Research from the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) and its partners shows how to help children learn amid erratic access to schools during a pandemic, and how those solutions may make progress toward the Sustainable Development Goal of ensuring a quality education for all by 2030.

- order reprints

- related stories

By Radhika Bhula & John Floretta Oct. 16, 2020

Five years into the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the world is nowhere near to ensuring a quality education for all by 2030. Impressive gains in enrollment and attendance over recent decades have not translated into corresponding gains in learning. The World Bank’s metric of "learning poverty," which refers to children who cannot read and understand a simple text by age 10, is a staggering 80 percent in low-income countries .

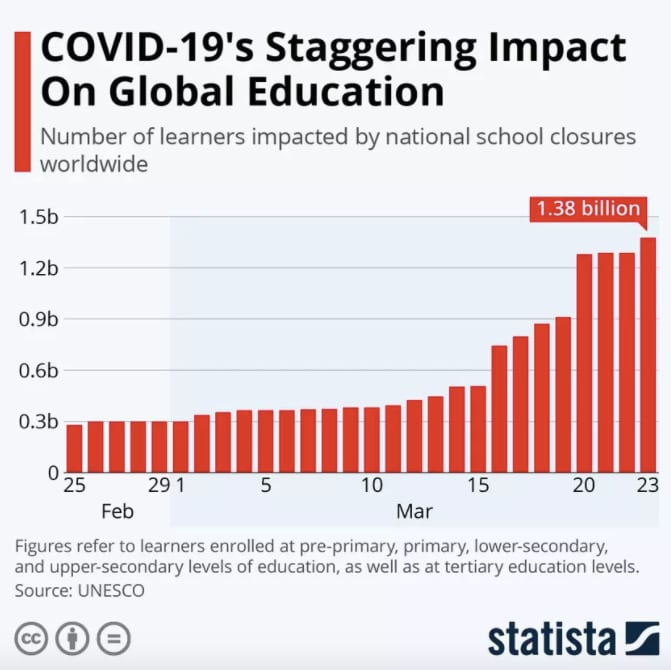

The COVID-19 crisis is exacerbating this learning crisis. As many as 94 percent of children across the world have been out of school due to closures. Learning losses from school shutdowns are further compounded by inequities , particularly for students who were already left behind by education systems. Many countries and schools have shifted to online learning during school closures as a stop-gap measure. However, this is not possible in many places, as less than half of households in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) have internet access.

Many education systems around the world are now reopening fully, partially, or in a hybrid format, leaving millions of children to face a radically transformed educational experience. As COVID-19 cases rise and fall during the months ahead, the chaos will likely continue, with schools shutting down and reopening as needed to balance educational needs with protecting the health of students, teachers, and families. Parents, schools, and entire education systems—especially in LMICs—will need to play new roles to support student learning as the situation remains in flux, perhaps permanently. As they adjust to this new reality, research conducted by more than 220 professors affiliated with the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) and innovations from J-PAL's partners provide three insights into supporting immediate and long-term goals for educating children.

1. Support caregivers at home to help children learn while schools are closed . With nearly 1.6 billion children out of school at the peak of the pandemic, many parents or caregivers, especially with young children, have taken on new roles to help with at-home learning. To support them and remote education efforts, many LMICs have used SMS, phone calls, and other widely accessible, affordable, and low-technology methods of information delivery. While such methods are imperfect substitutes for schooling, research suggests they can help engage parents in their child’s education and contribute to learning , perhaps even after schools reopen.

Preliminary results from an ongoing program and randomized evaluation in Botswana show the promise of parental support combined with low-technology curriculum delivery. When the pandemic hit, the NGO Young 1ove was working with Botswana's Ministry of Education to scale up the Teaching at the Right Level approach to primary schools in multiple districts. After collecting student, parent, and teacher phone numbers, the NGO devised two strategies to deliver educational support. The first strategy sent SMS texts to households with a series of numeracy “problems of the week.” The second sent the same texts combined with 20-minute phone calls with Young 1ove staff members, who walked parents and students through the problems. Over four to five weeks, both interventions significantly improved learning . They halved the number of children who could not do basic mathematical operations like subtraction and division. Parents became more engaged with their children's education and had a better understanding of their learning levels. Young 1ove is now evaluating the impact of SMS texts and phone calls that are tailored to students’ numeracy levels.

In another example, the NGO Educate! reoriented its in-school youth skills model to be delivered through radio, SMS, and phone calls in response to school closures in East Africa. To encourage greater participation, Educate! called the students' caregivers to tell them about the program. Their internal analysis indicates that households that received such encouragement calls had a 29 percent increase in youth participation compared to those that did not receive the communication.

In several Latin American countries , researchers are evaluating the impact of sending SMS texts to parents on how to support their young children who have transitioned to distance-learning programs. Similar efforts to support parents and evaluate the effects are underway in Peru . Both will contribute to a better understanding of how to help caregivers support their child’s education using affordable and accessible technology.

Other governments and organizations in areas where internet access is limited are also experimenting with radio and TV to support parents and augment student learning. The Côte d’Ivoire government created a radio program on math and French for children in grades one to five. It involved hundreds of short lessons. The Indian NGO Pratham collaborated with the Bihar state government and a television channel to produce 10 hours of learning programming per week, creating more than 100 episodes to date. Past randomized evaluations of such “edutainment” programs from other sectors in Nigeria , Rwanda , and Uganda suggest the potential of delivering content and influencing behavior through mass media, though context is important, and more rigorous research is needed to understand the impact of such programs on learning.

2. As schools reopen, educators should use low-stakes assessments to identify learning gaps. As of September 1, schools in more than 75 countries were open to some degree. Many governments need to be prepared for the vast majority of children to be significantly behind in their educations as they return—a factor exacerbated by the low pre-pandemic learning levels, particularly in LMICs . Rather than jumping straight into grade-level curriculum, primary schools in LMICs should quickly assess learning levels to understand what children know (or don’t) and devise strategic responses. They can do so by using simple tools to frequently assess students, rather than focusing solely on high-stakes exams, which may significantly influence a child’s future by, for example, determining grade promotion.

Orally administered assessments—such as ASER , ICAN , and Uwezo —are simple, fast, inexpensive, and effective. The ASER math tool, for example, has just four elements: single-digit number recognition, double-digit number recognition, two-digit subtraction, and simple division. A similar tool exists for assessing foundational reading abilities. Tests like these don’t affect a child’s grades or promotion, help teachers to get frequent and clear views into learning levels, and can enable schools to devise plans to help children master the basics.

3. Tailor children's instruction to help them master foundational skills once learning gaps are identified. Given low learning levels before the pandemic and recent learning loss due to school disruptions, it is important to focus on basic skills as schools reopen to ensure children maintain and build a foundation for a lifetime of learning. Decades of research from Chile, India, Kenya, Ghana, and the United States shows that tailoring instruction to children’s’ education levels increases learning. For example, the Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL) approach, pioneered by Indian NGO Pratham and evaluated in partnership with J-PAL researchers through six randomized evaluations over the last 20 years, focuses on foundational literacy and numeracy skills through interactive activities for a portion of the day rather than solely on the curriculum. It involves regular assessments of students' progress and is reaching more than 60 million children in India and several African countries .

Toward Universal Quality Education

As countries rebuild and reinvent themselves in response to COVID-19, there is an opportunity to accelerate the thinking on how to best support quality education for all. In the months and years ahead, coalitions of evidence-to-policy organizations, implementation partners, researchers, donors, and governments should build on their experiences to develop education-for-all strategies that use expansive research from J-PAL and similar organizations. In the long term, evidence-informed decisions and programs that account for country-specific conditions have the potential to improve pedagogy, support teachers, motivate students, improve school governance, and address many other aspects of the learning experience. Perhaps one positive outcome of the pandemic is that it will push us to overcome the many remaining global educational challenges sooner than any of us expect. We hope that we do.

Support SSIR ’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges. Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today .

Read more stories by Radhika Bhula & John Floretta .

SSIR.org and/or its third-party tools use cookies, which are necessary to its functioning and to our better understanding of user needs. By closing this banner, scrolling this page, clicking a link or continuing to otherwise browse this site, you agree to the use of cookies.

The pandemic has had devastating impacts on learning. What will it take to help students catch up?

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, megan kuhfeld , megan kuhfeld senior research scientist - nwea @megankuhfeld jim soland , jim soland assistant professor, school of education and human development - university of virginia, affiliated research fellow - nwea @jsoland karyn lewis , and karyn lewis director, center for school and student progress - nwea @karynlew emily morton emily morton research scientist - nwea @emily_r_morton.

March 3, 2022

As we reach the two-year mark of the initial wave of pandemic-induced school shutdowns, academic normalcy remains out of reach for many students, educators, and parents. In addition to surging COVID-19 cases at the end of 2021, schools have faced severe staff shortages , high rates of absenteeism and quarantines , and rolling school closures . Furthermore, students and educators continue to struggle with mental health challenges , higher rates of violence and misbehavior , and concerns about lost instructional time .

As we outline in our new research study released in January, the cumulative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on students’ academic achievement has been large. We tracked changes in math and reading test scores across the first two years of the pandemic using data from 5.4 million U.S. students in grades 3-8. We focused on test scores from immediately before the pandemic (fall 2019), following the initial onset (fall 2020), and more than one year into pandemic disruptions (fall 2021).

Average fall 2021 math test scores in grades 3-8 were 0.20-0.27 standard deviations (SDs) lower relative to same-grade peers in fall 2019, while reading test scores were 0.09-0.18 SDs lower. This is a sizable drop. For context, the math drops are significantly larger than estimated impacts from other large-scale school disruptions, such as after Hurricane Katrina—math scores dropped 0.17 SDs in one year for New Orleans evacuees .

Even more concerning, test-score gaps between students in low-poverty and high-poverty elementary schools grew by approximately 20% in math (corresponding to 0.20 SDs) and 15% in reading (0.13 SDs), primarily during the 2020-21 school year. Further, achievement tended to drop more between fall 2020 and 2021 than between fall 2019 and 2020 (both overall and differentially by school poverty), indicating that disruptions to learning have continued to negatively impact students well past the initial hits following the spring 2020 school closures.

These numbers are alarming and potentially demoralizing, especially given the heroic efforts of students to learn and educators to teach in incredibly trying times. From our perspective, these test-score drops in no way indicate that these students represent a “ lost generation ” or that we should give up hope. Most of us have never lived through a pandemic, and there is so much we don’t know about students’ capacity for resiliency in these circumstances and what a timeline for recovery will look like. Nor are we suggesting that teachers are somehow at fault given the achievement drops that occurred between 2020 and 2021; rather, educators had difficult jobs before the pandemic, and now are contending with huge new challenges, many outside their control.

Clearly, however, there’s work to do. School districts and states are currently making important decisions about which interventions and strategies to implement to mitigate the learning declines during the last two years. Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) investments from the American Rescue Plan provided nearly $200 billion to public schools to spend on COVID-19-related needs. Of that sum, $22 billion is dedicated specifically to addressing learning loss using “evidence-based interventions” focused on the “ disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on underrepresented student subgroups. ” Reviews of district and state spending plans (see Future Ed , EduRecoveryHub , and RAND’s American School District Panel for more details) indicate that districts are spending their ESSER dollars designated for academic recovery on a wide variety of strategies, with summer learning, tutoring, after-school programs, and extended school-day and school-year initiatives rising to the top.

Comparing the negative impacts from learning disruptions to the positive impacts from interventions

To help contextualize the magnitude of the impacts of COVID-19, we situate test-score drops during the pandemic relative to the test-score gains associated with common interventions being employed by districts as part of pandemic recovery efforts. If we assume that such interventions will continue to be as successful in a COVID-19 school environment, can we expect that these strategies will be effective enough to help students catch up? To answer this question, we draw from recent reviews of research on high-dosage tutoring , summer learning programs , reductions in class size , and extending the school day (specifically for literacy instruction) . We report effect sizes for each intervention specific to a grade span and subject wherever possible (e.g., tutoring has been found to have larger effects in elementary math than in reading).

Figure 1 shows the standardized drops in math test scores between students testing in fall 2019 and fall 2021 (separately by elementary and middle school grades) relative to the average effect size of various educational interventions. The average effect size for math tutoring matches or exceeds the average COVID-19 score drop in math. Research on tutoring indicates that it often works best in younger grades, and when provided by a teacher rather than, say, a parent. Further, some of the tutoring programs that produce the biggest effects can be quite intensive (and likely expensive), including having full-time tutors supporting all students (not just those needing remediation) in one-on-one settings during the school day. Meanwhile, the average effect of reducing class size is negative but not significant, with high variability in the impact across different studies. Summer programs in math have been found to be effective (average effect size of .10 SDs), though these programs in isolation likely would not eliminate the COVID-19 test-score drops.

Figure 1: Math COVID-19 test-score drops compared to the effect sizes of various educational interventions

Source: COVID-19 score drops are pulled from Kuhfeld et al. (2022) Table 5; reduction-in-class-size results are from pg. 10 of Figles et al. (2018) Table 2; summer program results are pulled from Lynch et al (2021) Table 2; and tutoring estimates are pulled from Nictow et al (2020) Table 3B. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals are shown with vertical lines on each bar.

Notes: Kuhfeld et al. and Nictow et al. reported effect sizes separately by grade span; Figles et al. and Lynch et al. report an overall effect size across elementary and middle grades. We were unable to find a rigorous study that reported effect sizes for extending the school day/year on math performance. Nictow et al. and Kraft & Falken (2021) also note large variations in tutoring effects depending on the type of tutor, with larger effects for teacher and paraprofessional tutoring programs than for nonprofessional and parent tutoring. Class-size reductions included in the Figles meta-analysis ranged from a minimum of one to minimum of eight students per class.

Figure 2 displays a similar comparison using effect sizes from reading interventions. The average effect of tutoring programs on reading achievement is larger than the effects found for the other interventions, though summer reading programs and class size reduction both produced average effect sizes in the ballpark of the COVID-19 reading score drops.

Figure 2: Reading COVID-19 test-score drops compared to the effect sizes of various educational interventions

Source: COVID-19 score drops are pulled from Kuhfeld et al. (2022) Table 5; extended-school-day results are from Figlio et al. (2018) Table 2; reduction-in-class-size results are from pg. 10 of Figles et al. (2018) ; summer program results are pulled from Kim & Quinn (2013) Table 3; and tutoring estimates are pulled from Nictow et al (2020) Table 3B. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals are shown with vertical lines on each bar.

Notes: While Kuhfeld et al. and Nictow et al. reported effect sizes separately by grade span, Figlio et al. and Kim & Quinn report an overall effect size across elementary and middle grades. Class-size reductions included in the Figles meta-analysis ranged from a minimum of one to minimum of eight students per class.

There are some limitations of drawing on research conducted prior to the pandemic to understand our ability to address the COVID-19 test-score drops. First, these studies were conducted under conditions that are very different from what schools currently face, and it is an open question whether the effectiveness of these interventions during the pandemic will be as consistent as they were before the pandemic. Second, we have little evidence and guidance about the efficacy of these interventions at the unprecedented scale that they are now being considered. For example, many school districts are expanding summer learning programs, but school districts have struggled to find staff interested in teaching summer school to meet the increased demand. Finally, given the widening test-score gaps between low- and high-poverty schools, it’s uncertain whether these interventions can actually combat the range of new challenges educators are facing in order to narrow these gaps. That is, students could catch up overall, yet the pandemic might still have lasting, negative effects on educational equality in this country.

Given that the current initiatives are unlikely to be implemented consistently across (and sometimes within) districts, timely feedback on the effects of initiatives and any needed adjustments will be crucial to districts’ success. The Road to COVID Recovery project and the National Student Support Accelerator are two such large-scale evaluation studies that aim to produce this type of evidence while providing resources for districts to track and evaluate their own programming. Additionally, a growing number of resources have been produced with recommendations on how to best implement recovery programs, including scaling up tutoring , summer learning programs , and expanded learning time .

Ultimately, there is much work to be done, and the challenges for students, educators, and parents are considerable. But this may be a moment when decades of educational reform, intervention, and research pay off. Relying on what we have learned could show the way forward.

Related Content

Megan Kuhfeld, Jim Soland, Beth Tarasawa, Angela Johnson, Erik Ruzek, Karyn Lewis

December 3, 2020

Lindsay Dworkin, Karyn Lewis

October 13, 2021

Education Policy K-12 Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Katharine Meyer

May 7, 2024

Jamie Klinenberg, Jon Valant, Nicolas Zerbino

Thinley Choden

May 3, 2024

Mission: Recovering Education in 2021

THE CONTEXT

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused abrupt and profound changes around the world. This is the worst shock to education systems in decades, with the longest school closures combined with looming recession. It will set back progress made on global development goals, particularly those focused on education. The economic crises within countries and globally will likely lead to fiscal austerity, increases in poverty, and fewer resources available for investments in public services from both domestic expenditure and development aid. All of this will lead to a crisis in human development that continues long after disease transmission has ended.

Disruptions to education systems over the past year have already driven substantial losses and inequalities in learning. All the efforts to provide remote instruction are laudable, but this has been a very poor substitute for in-person learning. Even more concerning, many children, particularly girls, may not return to school even when schools reopen. School closures and the resulting disruptions to school participation and learning are projected to amount to losses valued at $10 trillion in terms of affected children’s future earnings. Schools also play a critical role around the world in ensuring the delivery of essential health services and nutritious meals, protection, and psycho-social support. Thus, school closures have also imperilled children’s overall wellbeing and development, not just their learning.

It’s not enough for schools to simply reopen their doors after COVID-19. Students will need tailored and sustained support to help them readjust and catch-up after the pandemic. We must help schools prepare to provide that support and meet the enormous challenges of the months ahead. The time to act is now; the future of an entire generation is at stake.

THE MISSION

Mission objective: To enable all children to return to school and to a supportive learning environment, which also addresses their health and psychosocial well-being and other needs.

Timeframe : By end 2021.

Scope : All countries should reopen schools for complete or partial in-person instruction and keep them open. The Partners - UNESCO , UNICEF , and the World Bank - will join forces to support countries to take all actions possible to plan, prioritize, and ensure that all learners are back in school; that schools take all measures to reopen safely; that students receive effective remedial learning and comprehensive services to help recover learning losses and improve overall welfare; and their teachers are prepared and supported to meet their learning needs.

Three priorities:

1. All children and youth are back in school and receive the tailored services needed to meet their learning, health, psychosocial wellbeing, and other needs.

Challenges : School closures have put children’s learning, nutrition, mental health, and overall development at risk. Closed schools also make screening and delivery for child protection services more difficult. Some students, particularly girls, are at risk of never returning to school.

Areas of action : The Partners will support the design and implementation of school reopening strategies that include comprehensive services to support children’s education, health, psycho-social wellbeing, and other needs.

Targets and indicators

2. All children receive support to catch up on lost learning.

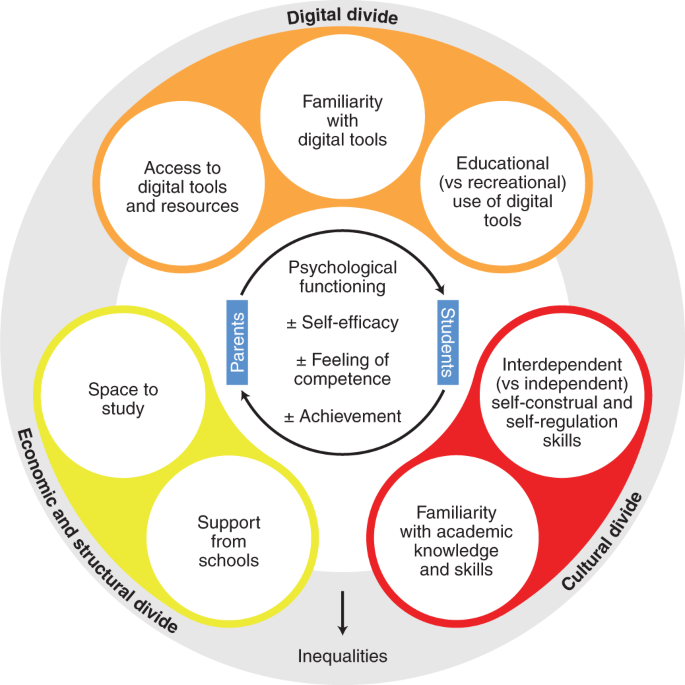

Challenges : Most children have lost substantial instructional time and may not be ready for curricula that were age- and grade- appropriate prior to the pandemic. They will require remedial instruction to get back on track. The pandemic also revealed a stark digital divide that schools can play a role in addressing by ensuring children have digital skills and access.

Areas of action : The Partners will (i) support the design and implementation of large-scale remedial learning at different levels of education, (ii) launch an open-access, adaptable learning assessment tool that measures learning losses and identifies learners’ needs, and (iii) support the design and implementation of digital transformation plans that include components on both infrastructure and ways to use digital technology to accelerate the development of foundational literacy and numeracy skills. Incorporating digital technologies to teach foundational skills could complement teachers’ efforts in the classroom and better prepare children for future digital instruction.

While incorporating remedial education, social-emotional learning, and digital technology into curricula by the end of 2021 will be a challenge for most countries, the Partners agree that these are aspirational targets that they should be supporting countries to achieve this year and beyond as education systems start to recover from the current crisis.

3. All teachers are prepared and supported to address learning losses among their students and to incorporate digital technology into their teaching.

Challenges : Teachers are in an unprecedented situation in which they must make up for substantial loss of instructional time from the previous school year and teach the current year’s curriculum. They must also protect their own health in school. Teachers will need training, coaching, and other means of support to get this done. They will also need to be prioritized for the COVID-19 vaccination, after frontline personnel and high-risk populations. School closures also demonstrated that in addition to digital skills, teachers may also need support to adapt their pedagogy to deliver instruction remotely.

Areas of action : The Partners will advocate for teachers to be prioritized in COVID-19 vaccination campaigns, after frontline personnel and high-risk populations, and provide capacity-development on pedagogies for remedial learning and digital and blended teaching approaches.

Country level actions and global support

UNESCO, UNICEF, and World Bank are joining forces to support countries to achieve the Mission, leveraging their expertise and actions on the ground to support national efforts and domestic funding.

Country Level Action

1. Mobilize team to support countries in achieving the three priorities

The Partners will collaborate and act at the country level to support governments in accelerating actions to advance the three priorities.

2. Advocacy to mobilize domestic resources for the three priorities

The Partners will engage with governments and decision-makers to prioritize education financing and mobilize additional domestic resources.

Global level action

1. Leverage data to inform decision-making

The Partners will join forces to conduct surveys; collect data; and set-up a global, regional, and national real-time data-warehouse. The Partners will collect timely data and analytics that provide access to information on school re-openings, learning losses, drop-outs, and transition from school to work, and will make data available to support decision-making and peer-learning.

2. Promote knowledge sharing and peer-learning in strengthening education recovery

The Partners will join forces in sharing the breadth of international experience and scaling innovations through structured policy dialogue, knowledge sharing, and peer learning actions.

The time to act on these priorities is now. UNESCO, UNICEF, and the World Bank are partnering to help drive that action.

Last Updated: Mar 30, 2021

- (BROCHURE, in English) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (BROCHURE, in French) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (BROCHURE, in Spanish) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (BLOG) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (VIDEO, Arabic) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (VIDEO, French) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (VIDEO, Spanish) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- World Bank Education and COVID-19

- World Bank Blogs on Education

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

America's Education News Source

Copyright 2024 The 74 Media, Inc

- Pine Bluff, Arkansas

- absenteeism

- Future of High School

- Artificial Intelligence

- science of reading

Best Education Essays of 2021: Our 15 Most Discussed Columns About Schools, COVID Slide, Learning Recovery & More

A full calendar year of education under COVID-19 and its variants gave rise to a wave of memorable essays in 2021, focusing both on the ongoing damage done and how to mitigate learning loss going forward.

While consensus emerged around several key themes — the need for extensive, in-depth tutoring, the possibilities presented by unprecedented millions in federal relief dollars for schools, the opportunity for education reimagined — there was far less agreement on whether to remediate or accelerate, which health and safety measures schools should employ, even how dire the shortage of teachers and school staff really is.

From grade-level standards and hygiene theater to lessons from the Spanish flu and homeschooling, here are the 15 most read and buzzed-about essays of 2021:

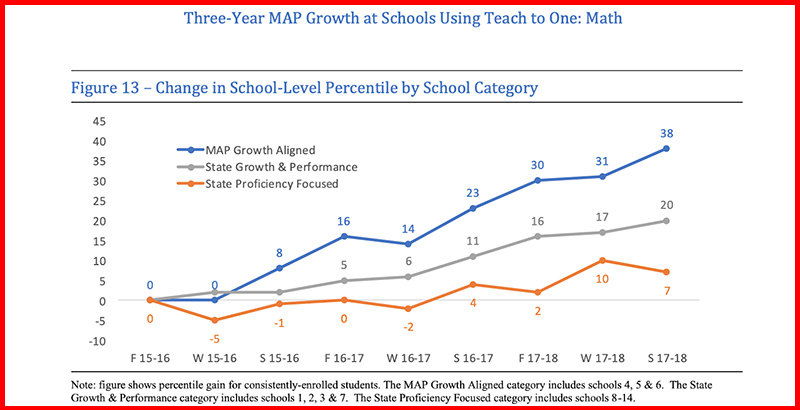

Analysis: Focus on Grade-Level Standards or Meet Students Where They Are? How an Unintentional Experiment Guided a Strategy for Addressing Learning Loss

Learning Recovery: What’s the best way to support learning recovery in middle-grade math? Should schools stay focused on grade-level standards while trying to address critical learning gaps as best as they can? Or should they systematically address individual students’ unfinished learning from prior years so they can ultimately catch back up — even if that means spending meaningful time teaching below-grade skills? As educators and administrators wrestle with those questions as they prepare to return to school in the fall, contributor Joel Rose offers some guidance inadvertently found in a study of Teach to One , an innovative learning model operated by New Classrooms Innovation Partners, the nonprofit where he is co-founder and CEO. That research found performance in schools with accountability systems that focused on grade-level proficiency (and thus prioritized grade-level exposure) grew 7 percentile points, while those that operated under systems that rewarded student growth (and thus prioritized individual student needs) grew 38 points. While the study was never intended to compare results across schools in this way, the stark difference between the two groups could not be ignored. Math is cumulative, and the path to proficiency often requires addressing unfinished learning from prior years. For the middle grades, administrators and policymakers would be wise to question the grade-level-only gospel as they begin to plan students’ educational recovery. Read the full analysis .

Lessons from Spanish Flu — Babies Born in 1919 Had Worse Educational, Life Outcomes Than Those Born Just Before or After. Could That Happen With COVID-19?

History: Contributor Chad Aldeman has some bad news: The effects of COVID-19 are likely to linger for decades. And if the Spanish Flu is any indication, babies born during the pandemic may suffer some devastating consequences . Compared with children born just before or after, babies born during the flu pandemic in 1919 were less likely to finish high school, earned less money and were more likely to depend on welfare assistance and serve time in jail. The harmful effects were twice as large for nonwhite children. It may take a few years to see whether similar educational and economic effects from COVID-19 start to materialize, but these are ominous findings suggesting that hidden economic factors may influence a child’s life in ways that aren’t obvious in the moment. Hopefully, they will give policymakers more reasons to speed economic recovery efforts and make sure they deliver benefits to families and children who are going to need them the most. Read the full essay .

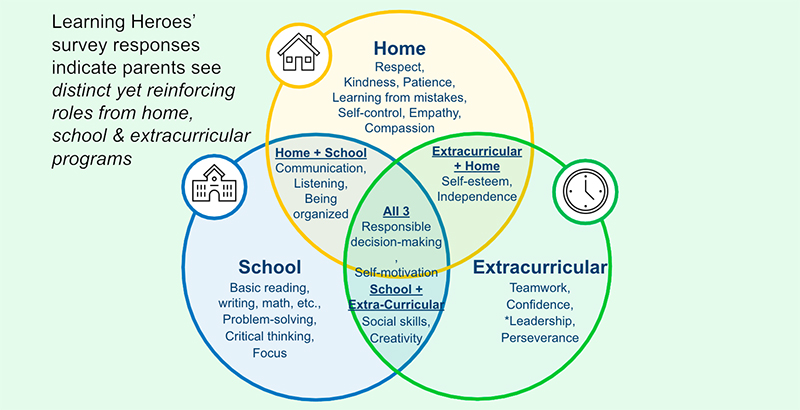

Pittman & Darling-Hammond: Surveys Find Parents Want Bold Changes in Schools — With More Learning Inside and Outside the Classroom

Future of Education: Whatever they thought of their schools before the pandemic struck, parents now have strong opinions about what they want them to provide. They are looking beyond fall reopenings to rethink schooling, and they care about having good choices for interest-driven learning opportunities beyond the classroom . Two national parent surveys released in May shed new light on how to think about the often-used phrase “more and better learning.” Among the key findings, write contributors Karen Pittman and Linda Darling-Hammond: Parents want bold changes in schools, to make public education more equitable and learner-centered. But they also believe that home, school and extracurriculars play complementary roles in imparting the broad set of skills children need for their future success. This means educators and policymakers must support learning that extends beyond the school day, the school walls, the school staff and the traditional school approaches. Read the full essay .

High-Quality, High-Dosage Tutoring Can Reduce Learning Loss. A Blueprint for How Washington, States & Districts Can Make It Happen

Personalized Learning: There is near-unanimous, bipartisan agreement that tutoring is among the most promising, evidence-based strategies to help students struggling with learning loss . Decades of rigorous evaluations have consistently found that tutoring programs yield large, positive effects on math and reading achievement, and can even lead to greater social and motivational outcomes. It isn’t just the research community buzzing about tutoring — it is gaining momentum in policy circles, too. Which means there is a real opportunity — and responsibility — to design and deliver tutoring programs in a way that aligns with the research evidence, which is fortunately beginning to tell us more than just “tutoring works.” Contributors Sara Kerr and Kate Tromble of Results for America lay out a blueprint for how Washington, states and local school districts can make high-quality, high-dosage tutoring happen .

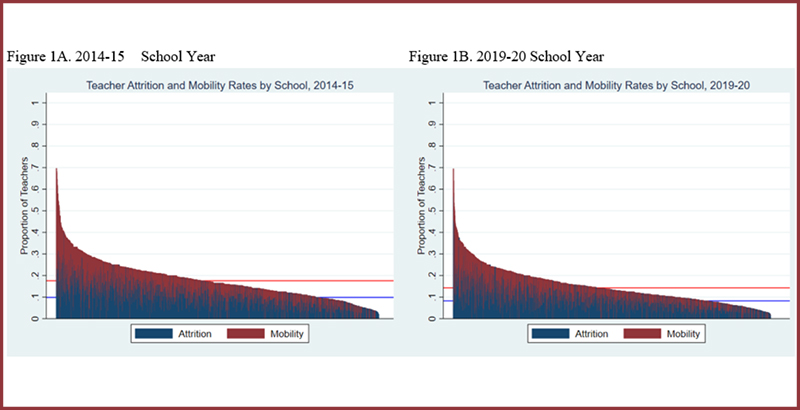

COVID-19 Raised Fears of Teacher Shortages. But the Situation Varies from State to State, School to School & Subject to Subject

Teacher Pipeline: Is the U.S. facing a major teacher shortage? Relatively low pay, a booming private sector and adverse working conditions in schools are all important elements in whether teaching is becoming an undesirable profession. But, writes contributor Dan Goldhaber, the factors that lead to attrition are diverse, so treating teachers as a monolith doesn’t help in crafting solutions to the real staffing challenges that some schools face. There is no national teacher labor market per se, because each state adopts its own rules for pay, licensure, tenure, pension and training requirements. And nationally, tens of thousands more people are prepared to teach than there are available positions. But while some schools have applicants lined up when an opening becomes available, others, typically those serving economically disadvantaged students, draw far fewer candidates. And schools tend to struggle to find teachers with special education or STEM training. The pandemic certainly raises concerns about teacher shortages; what is needed is a more nuanced conversation about teacher staffing to come up with more effective solutions to real problems. Read the full essay .

Clash of Cultures, Clash of Privilege — What Happened When 30 Low-Income Students of Color Were Admitted to Elite Prep Schools

Analysis: Programs like Prep for Prep and A Better Chance have long been regarded as groundbreaking solutions to the lack of diversity in the nation’s most elite prep schools. Teens who join these types of programs undergo a transfer of privilege that starts with their education and bleeds into every facet of their lives, forever altering their trajectory with opportunities that otherwise would likely be unattainable. But what assumptions do these programs subscribe to? And what lessons can be found in the experiences of the participants? In her Harvard senior thesis, contributor Jessica Herrera Chaidez followed 30 participants in a program that grants select socioeconomically disadvantaged students of color in the Los Angeles area the opportunity to attend famed independent schools. She found that the experiences of these students can be understood in various forms of twoness associated with this transfer of privilege, an internal struggle that begins with their introduction to the world of elite education and will come to mark them for their entire lives in a way that they aren’t even able to comprehend yet. Read more about her findings, and what some of these students had to say .

Steiner & Wilson: Some Tough Questions, and Some Answers, About Fighting COVID Slide While Accelerating Student Learning

Case Study: How prepared are district leaders, principals and teachers as they work to increase learning readiness for on-grade work this fall? That’s the question posed by contributors David Steiner and Barbara Wilson in a case study examining how a large urban district sought to adapt materials it was already using to implement an acceleration strategy for early elementary foundational skills in reading . Among the insights to be drawn: First, planning is critical. Leaders need to set out precisely how many minutes of instruction will be provided, the exact learning goals and the specific materials; identify all those involved (tutors, specialists, and teachers); and give them access to shared professional development on the chosen acceleration strategies. Second, this requires a sea change from business as usual, where teachers attempt to impart skill-based standards using an eclectic rather than a coherent curriculum. It is not possible to accelerate children with fragmented content. All efforts to prepare students for grade-level instruction must rest on fierce agreement about the shared curriculum to be taught in classrooms. What we teach is the anchor that holds everything else in place. Read the full essay .

Schools Are Facing a Surge of Failing Grades During the Pandemic — and Traditional Approaches Like Credit Recovery Will Not Be Enough to Manage It

Student Supports: Earlier this year, failing grades were on the rise across the country — especially for students who are learning online — and the trend threatened to exacerbate existing educational inequities. The rise in failing grades appears to be most pronounced among students from low-income households, multilingual students and students learning virtually . This could have lasting consequences: Students with failing grades tend to have less access to advanced courses in high school, and a failing grade in even one ninth-grade course can lower a student’s chances of graduating on time. Addressing the problem, though, won’t be easy. In many school systems, the rash of failed courses could overwhelm traditional approaches to helping students make up coursework they may have missed. In a new analysis, Betheny Gross, associate director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education, implored school and district leaders to be especially wary of one long-established but questionable practice: credit recovery. Read more about her warning — as well as her recommendations for how districts should seek to reverse this learning loss .

Riccards: The 1776 Report Is a Political Document, Not a Curriculum. But It Has Something to Teach Us

Analysis: The 1776 Report was never intended to stand as curriculum, nor was it designed to be translated into a curriculum as the 1619 Project was. It is a political document offered by political voices. But, writes contributor Patrick Riccards, dismissing it would be a mistake, because it provides an important lesson . The American record, whether it be measured starting in 1619 or 1776, is hopeful and ugly, inspiring and debilitating, a shining beacon and an unshakable dark cloud. American history is messy and contradictory; how we teach it, even more so. For years, we have heard how important it is to increase investment in civics education. But from #BlackLivesMatter to 2020 electioneering to even the assault on the U.S. Capitol, the basics of civics have been on display in our streets and corridors of power. What we lack is the collective historical knowledge necessary to translate civic education into meaningful, positive community change. The 1776 Report identifies beliefs espoused by our Founding Fathers and many Confederates and reflected by those who attacked the Capitol on Jan. 6. They are a part of our history that we must study, understand, contextualize and deconstruct. The 1776 Report becomes the proper close to the social studies lessons of the past four years. As the next chapter of American history is written, it is imperative to apply those lessons to significantly improve the teaching and learning of American history. Our nation’s future depends on better understanding our past .

There’s Lots of Education Data Out There — and It Can Be Misleading. Here Are 6 Questions to Ask

Student Data: Data is critical to addressing inequities in education. However, it is often misused, interpreted to fit a particular agenda or misread in ways that perpetuate an inaccurate story . Data that’s not broken down properly can hide gaps between different groups of students. Facts out of context can lead to superficial conclusions or deceptive narratives. In this essay, contributor Krista Kaput presents six questions that she asks herself when consuming data — and that you should, too .

Educators’ View: Principals Know Best What Their Schools Need. They Should Have a Central Role in Deciding How Relief Funds Are Spent

School Funding: The American Rescue Plan represents a once-in-a-generation federal commitment to K-12 schools across the country. The impact will be felt immediately: The $122 billion in direct funding will support safe school reopenings, help ensure that schools already providing in-person instruction can safely stay open and aid students in recovering from academic and mental health challenges induced and exacerbated by the pandemic. How these funds are distributed will shape the educational prospects of millions of students, affecting the country for decades to come. As they make rescue plan funding decisions, write contributors L. Earl Franks of the National Association of Elementary School Principals and Ronn Nozoe of the National Association of Secondary School Principals, states and districts should meaningfully engage and empower school principals throughout all phases of implementation. Principals, as leaders of their school buildings and staff, have unequaled insights into their individual schools’ needs and know which resources are required most urgently. Read the authors’ four recommendations for leveraging this expertise .

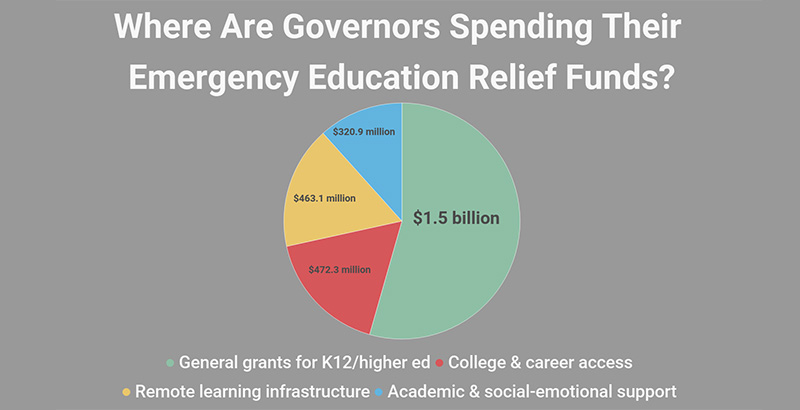

Case Studies: How 11 States Are Using Emergency Federal Funds to Make Improvements in College and Career Access That Will Endure Beyond the Pandemic

COVID Relief: The Governor’s Emergency Education Relief Fund gave states more than $4 billion in discretionary federal dollars to support K-12 schools, higher education and workforce initiatives. These were welcome resources, coming just as the pandemic accelerated unemployment and exacerbated declining college enrollment, hitting those from low-income backgrounds hardest. But as contributors Betheny Gross, Georgia Heyward and Matt Robinson note, most states have invested overwhelmingly in one-time college scholarships or short-term supports that will end once funds run out. In hopes of encouraging policymakers across the country to make more sustainable investments with the remaining relief funds, the trio spotlights efforts in 11 states that show promise in enduring beyond COVID-19. Read our full case study .

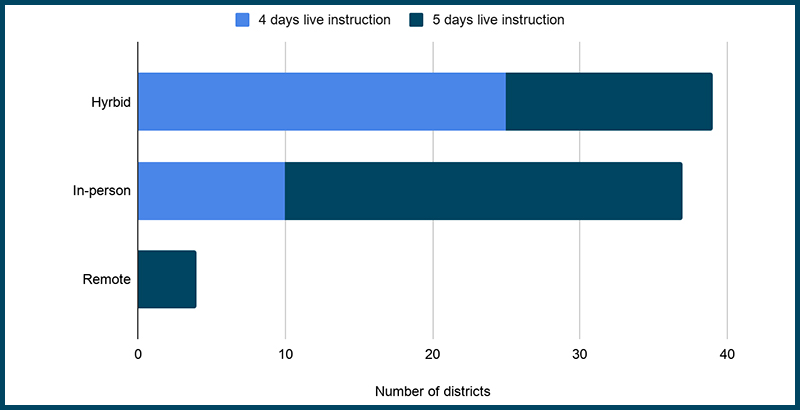

In Thousands of Districts, 4-Day School Weeks Are Robbing Students of Learning Time for What Amounts to Hygiene Theater

School Safety: Last April, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention made clear that having good ventilation and wearing masks consistently are far more effective at preventing the spread of COVID-19 than disinfecting surfaces. This clarification was long overdue, say contributors Robin Lake and Georgia Heyward of the Center on Reinventing Public Education, as scientists had long suspected that deep cleaning and temperature checks are more hygiene theater than a strategy for limiting the spread of an airborne virus. Thousands of school districts, however, had already built complex fall reopening plans with a full day for at-home learning. The result was a modified four-day week with students receiving significantly reduced live instruction. Eliminating a full day of in-person teaching was always a high-cost strategy from an education standpoint; now there is confirmation that it was totally unnecessary. Lake and Heyward argue that we cannot afford to throw away an entire day of learning and student support based on a false scientific premise .

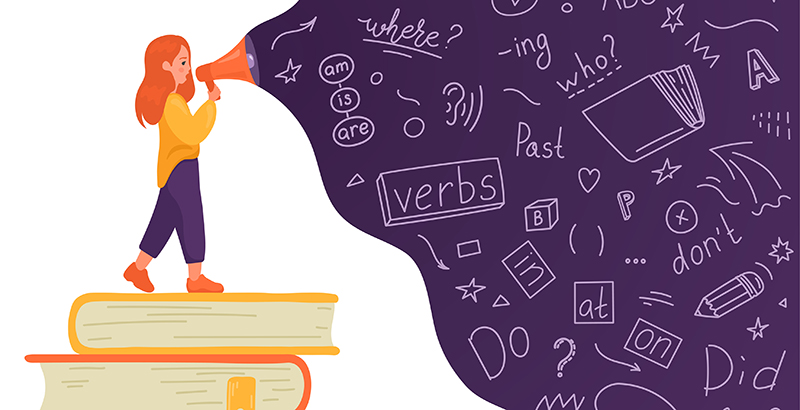

Teacher’s View: How the Science of Reading Helped Me Make the Most of Limited Time With My Students & Adapt Lessons to Meet Their Needs

First Person: March 12, 2020, was contributor Jessica Pasik’s last typical day in the classroom before COVID-19 changed everything. When her district closed, she assumed, as did many, that it was a temporary precaution. But with each passing week, she worried that the growth in reading she and her first-graders had worked so hard for would fade away . Many pre-pandemic instructional approaches to teaching reading were already failing students and teachers, and the stress of COVID-19 has only exacerbated these challenges. When Pasik’s district reopened for in-person classes in the fall, they were faced with difficult decisions about how to best deliver instruction. One factor that helped streamline this transition was a grounding in the science of reading. Having extensive knowledge of what they needed to teach allowed educators to focus on how they would teach, make the most of the limited instructional time they had with students and adapt lessons to meet their needs. There are multiple factors that teachers cannot control; one person alone cannot make the systematic changes needed for all children to reach proficiency in literacy. But one knowledgeable teacher can forever change the trajectory of a student’s life. Students will face many challenges once they leave the classroom, but low literacy does not need to be one of them. Read her full essay .

Homeschooling Is on the Rise. What Should That Teach Education Leaders About Families’ Preferences?

Disenrollment: With school closures, student quarantines and tensions over mask requirements, vaccine mandates and culture war issues, families’ lives have been upended in ways few could have imagined 18 months ago. That schools have struggled to adapt is understandable, writes contributor Alex Spurrier. But for millions of families, their willingness to tolerate institutional sclerosis in their children’s education is wearing thin. Over the past 18 months, the rate of families moving their children to a new school increased by about 50 percent , and some 1.2 million switched to homeschooling last academic year. Instead of working to get schools back to a pre-pandemic normal, Spurrier says, education leaders should look at addressing the needs of underserved kids and families — and the best way to understand where schools are falling short is to look at how families are voting with their feet. If options like homeschooling, pods and microschools retain some of their pandemic enrollment gains, it could have ripple effects on funding that resonate throughout the K-12 landscape. Read the full essay .

Go Deeper: Get our latest commentary, analysis and news coverage delivered directly to your inbox — sign up for The 74 Newsletter .

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

Bev Weintraub is an Executive Editor at The 74

- learning loss

We want our stories to be shared as widely as possible — for free.

Please view The 74's republishing terms.

Different Ways to Think About COVID, Schools & Repairing Students’ Lost Learning

By Bev Weintraub

This story first appeared at The 74 , a nonprofit news site covering education. Sign up for free newsletters from The 74 to get more like this in your inbox.

On The 74 Today

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Health & Nursing

Courses and certificates.

- Bachelor's Degrees

- View all Business Bachelor's Degrees

- Business Management – B.S. Business Administration

- Healthcare Administration – B.S.

- Human Resource Management – B.S. Business Administration

- Information Technology Management – B.S. Business Administration

- Marketing – B.S. Business Administration

- Accounting – B.S. Business Administration

- Finance – B.S.

- Supply Chain and Operations Management – B.S.

- Accelerated Information Technology Bachelor's and Master's Degree (from the School of Technology)

- Health Information Management – B.S. (from the Leavitt School of Health)

Master's Degrees

- View all Business Master's Degrees

- Master of Business Administration (MBA)

- MBA Information Technology Management

- MBA Healthcare Management

- Management and Leadership – M.S.

- Accounting – M.S.

- Marketing – M.S.

- Human Resource Management – M.S.

- Master of Healthcare Administration (from the Leavitt School of Health)

- Data Analytics – M.S. (from the School of Technology)

- Information Technology Management – M.S. (from the School of Technology)

- Education Technology and Instructional Design – M.Ed. (from the School of Education)

Certificates

- View all Business Degrees

Bachelor's Preparing For Licensure

- View all Education Bachelor's Degrees

- Elementary Education – B.A.

- Special Education and Elementary Education (Dual Licensure) – B.A.

- Special Education (Mild-to-Moderate) – B.A.

- Mathematics Education (Middle Grades) – B.S.

- Mathematics Education (Secondary)– B.S.

- Science Education (Middle Grades) – B.S.

- Science Education (Secondary Chemistry) – B.S.

- Science Education (Secondary Physics) – B.S.

- Science Education (Secondary Biological Sciences) – B.S.

- Science Education (Secondary Earth Science)– B.S.

- View all Education Degrees

Bachelor of Arts in Education Degrees

- Educational Studies – B.A.

Master of Science in Education Degrees

- View all Education Master's Degrees

- Curriculum and Instruction – M.S.

- Educational Leadership – M.S.

- Education Technology and Instructional Design – M.Ed.

Master's Preparing for Licensure

- Teaching, Elementary Education – M.A.

- Teaching, English Education (Secondary) – M.A.

- Teaching, Mathematics Education (Middle Grades) – M.A.

- Teaching, Mathematics Education (Secondary) – M.A.

- Teaching, Science Education (Secondary) – M.A.

- Teaching, Special Education (K-12) – M.A.

Licensure Information

- State Teaching Licensure Information

Master's Degrees for Teachers

- Mathematics Education (K-6) – M.A.

- Mathematics Education (Middle Grade) – M.A.

- Mathematics Education (Secondary) – M.A.

- English Language Learning (PreK-12) – M.A.

- Endorsement Preparation Program, English Language Learning (PreK-12)

- Science Education (Middle Grades) – M.A.

- Science Education (Secondary Chemistry) – M.A.

- Science Education (Secondary Physics) – M.A.

- Science Education (Secondary Biological Sciences) – M.A.

- Science Education (Secondary Earth Science)– M.A.

- View all Technology Bachelor's Degrees

- Cloud Computing – B.S.

- Computer Science – B.S.

- Cybersecurity and Information Assurance – B.S.

- Data Analytics – B.S.

- Information Technology – B.S.

- Network Engineering and Security – B.S.

- Software Engineering – B.S.

- Accelerated Information Technology Bachelor's and Master's Degree

- Information Technology Management – B.S. Business Administration (from the School of Business)

- View all Technology Master's Degrees

- Cybersecurity and Information Assurance – M.S.

- Data Analytics – M.S.

- Information Technology Management – M.S.

- MBA Information Technology Management (from the School of Business)

- Full Stack Engineering

- Web Application Deployment and Support

- Front End Web Development

- Back End Web Development

3rd Party Certifications

- IT Certifications Included in WGU Degrees

- View all Technology Degrees

- View all Health & Nursing Bachelor's Degrees

- Nursing (RN-to-BSN online) – B.S.

- Nursing (Prelicensure) – B.S. (Available in select states)

- Health Information Management – B.S.

- Health and Human Services – B.S.

- Psychology – B.S.

- Health Science – B.S.

- Healthcare Administration – B.S. (from the School of Business)

- View all Nursing Post-Master's Certificates

- Nursing Education—Post-Master's Certificate

- Nursing Leadership and Management—Post-Master's Certificate

- Family Nurse Practitioner—Post-Master's Certificate

- Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioner —Post-Master's Certificate

- View all Health & Nursing Degrees

- View all Nursing & Health Master's Degrees

- Nursing – Education (BSN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Nursing – Leadership and Management (BSN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Nursing – Nursing Informatics (BSN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Nursing – Family Nurse Practitioner (BSN-to-MSN Program) – M.S. (Available in select states)

- Nursing – Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioner (BSN-to-MSN Program) – M.S. (Available in select states)

- Nursing – Education (RN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Nursing – Leadership and Management (RN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Nursing – Nursing Informatics (RN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Master of Healthcare Administration

- MBA Healthcare Management (from the School of Business)

- Business Leadership (with the School of Business)

- Supply Chain (with the School of Business)

- Back End Web Development (with the School of Technology)

- Front End Web Development (with the School of Technology)

- Web Application Deployment and Support (with the School of Technology)

- Full Stack Engineering (with the School of Technology)

- Single Courses

- Course Bundles

Apply for Admission

Admission requirements.

- New Students

- WGU Returning Graduates

- WGU Readmission

- Enrollment Checklist

- Accessibility

- Accommodation Request

- School of Education Admission Requirements

- School of Business Admission Requirements

- School of Technology Admission Requirements

- Leavitt School of Health Admission Requirements

Additional Requirements

- Computer Requirements

- No Standardized Testing

- Clinical and Student Teaching Information

Transferring

- FAQs about Transferring

- Transfer to WGU

- Transferrable Certifications

- Request WGU Transcripts

- International Transfer Credit

- Tuition and Fees

- Financial Aid

- Scholarships

Other Ways to Pay for School

- Tuition—School of Business

- Tuition—School of Education

- Tuition—School of Technology

- Tuition—Leavitt School of Health

- Your Financial Obligations

- Tuition Comparison

- Applying for Financial Aid

- State Grants

- Consumer Information Guide

- Responsible Borrowing Initiative

- Higher Education Relief Fund

FAFSA Support

- Net Price Calculator

- FAFSA Simplification

- See All Scholarships

- Military Scholarships

- State Scholarships

- Scholarship FAQs

Payment Options

- Payment Plans

- Corporate Reimbursement

- Current Student Hardship Assistance

- Military Tuition Assistance

WGU Experience

- How You'll Learn

- Scheduling/Assessments

- Accreditation

- Student Support/Faculty

- Military Students

- Part-Time Options

- Virtual Military Education Resource Center

- Student Outcomes

- Return on Investment

- Students and Gradutes

- Career Growth

- Student Resources

- Communities

- Testimonials

- Career Guides

- Skills Guides

- Online Degrees

- All Degrees

- Explore Your Options

Admissions & Transfers

- Admissions Overview

Tuition & Financial Aid

Student Success

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Military and Veterans

- Commencement

- Careers at WGU

- Advancement & Giving

- Partnering with WGU

Shaping the Future of Education After COVID-19

- See More Tags

For new teachers, entering the field of education has always been an exciting, if daunting, prospect. Helping students achieve their full potential is richly rewarding, after all. But once the COVID-19 pandemic dissipates, a major challenge awaits teachers new and old.

The health crisis has opened new gaps in student achievement and exacerbated existing ones, threatening the future of education. Low-income students have endured the worst of the pandemic's deleterious effects.

Teachers, new and experienced alike, will be vital in reversing these effects. By addressing the challenges of a post-pandemic world, teachers can save a generation of students from long-term damage.

The widening gap.

The future of education hinges on equal access and participation, but COVID-19 has further widened the gap between the haves and the have nots. The National Bureau of Economic Research found that lower-income students are 55% more likely to delay graduation due to COVID-19 than their more affluent peers. On top of that, the bureau found that COVID-19 nearly doubled the gap between low- and high-income students in expected grade point average. The pandemic's disruption to students' ability to succeed isn't just profound—it's heterogeneous.

These gaps, rooted in socioeconomic disparities and exacerbated by pandemic-induced disruptions, will only get worse if left unaddressed. It's easy to point fingers at schools and, broadly, the educational system. But teachers are the educational professionals who have the most day-to-day contact with the students. They could potentially have the greatest impact in narrowing the achievement gap.

Cascading effects.

For teachers, advancing the future of education means advocating for every student. But that's easier said than done, as the cascading adverse effects of the pandemic disproportionately afflict socioeconomically challenged students.

Some of these effects are beyond teachers' control. For instance, a Tulsa School Experiences & Early Development study of approximately 1,000 low-income families in Tulsa, Oklahoma, determined that 46% of responding parents had lost their jobs or had decreased work hours and 49% experienced food insecurity since the start of the pandemic.

Elsewhere, Anna Johnson, a professor of psychology at Georgetown University and one of the authors of the Tulsa study, observed another technological hurdle that teachers will need to clear post-pandemic.

"These low-income kids are also more likely to have unreliable internet access," Johnson said. "Some of them don't have devices beyond a parent's smartphone, which makes connecting to teachers and classmates for learning nearly impossible."

Other cascading effects of the pandemic on students and families include depression, lack of sleep, declining physical health, and disruption in household routines—and each of these could harm a student's performance. Teachers need to be ready to meet the call and help their students after the pandemic subsides.

Making a difference.

For teachers, guiding the future of education means getting involved and advocating for their students. Teachers can't fix all their students' pandemic-related problems, but there are essential steps that they can take.

Give your students extra emotional support during and after the pandemic. The goal is to lift your students' spirits with words and body language that are inviting and accepting to everyone. However you communicate with them, take the time to greet and check in with each student every day.

Make the tasks that you assign meaningful. Different students have different learning styles, so apply every teaching technique you've learned to make learning engaging and equitable for every student.

No one expects teachers to shoulder the entire responsibility for shaping the future of education. But they play a vital role in helping students of every socioeconomic level work through these difficult circumstances and bring out their best. If you're interested in making a difference, there are plenty of ways to get the education you need.

Ready to Start Your Journey?

HEALTH & NURSING

Recommended Articles

Take a look at other articles from WGU. Our articles feature information on a wide variety of subjects, written with the help of subject matter experts and researchers who are well-versed in their industries. This allows us to provide articles with interesting, relevant, and accurate information.

{{item.date}}

{{item.preTitleTag}}

{{item.title}}

The university, for students.

- Student Portal

- Alumni Services

Most Visited Links

- Business Programs

- Student Experience

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- Student Communities

COVID-19 and education: The lingering effects of unfinished learning

As this most disrupted of school years draws to a close, it is time to take stock of the impact of the pandemic on student learning and well-being. Although the 2020–21 academic year ended on a high note—with rising vaccination rates, outdoor in-person graduations, and access to at least some in-person learning for 98 percent of students—it was as a whole perhaps one of the most challenging for educators and students in our nation’s history. 1 “Burbio’s K-12 school opening tracker,” Burbio, accessed May 31, 2021, cai.burbio.com. By the end of the school year, only 2 percent of students were in virtual-only districts. Many students, however, chose to keep learning virtually in districts that were offering hybrid or fully in-person learning.

Our analysis shows that the impact of the pandemic on K–12 student learning was significant, leaving students on average five months behind in mathematics and four months behind in reading by the end of the school year. The pandemic widened preexisting opportunity and achievement gaps, hitting historically disadvantaged students hardest. In math, students in majority Black schools ended the year with six months of unfinished learning, students in low-income schools with seven. High schoolers have become more likely to drop out of school, and high school seniors, especially those from low-income families, are less likely to go on to postsecondary education. And the crisis had an impact on not just academics but also the broader health and well-being of students, with more than 35 percent of parents very or extremely concerned about their children’s mental health.

The fallout from the pandemic threatens to depress this generation’s prospects and constrict their opportunities far into adulthood. The ripple effects may undermine their chances of attending college and ultimately finding a fulfilling job that enables them to support a family. Our analysis suggests that, unless steps are taken to address unfinished learning, today’s students may earn $49,000 to $61,000 less over their lifetime owing to the impact of the pandemic on their schooling. The impact on the US economy could amount to $128 billion to $188 billion every year as this cohort enters the workforce.

Federal funds are in place to help states and districts respond, though funding is only part of the answer. The deep-rooted challenges in our school systems predate the pandemic and have resisted many reform efforts. States and districts have a critical role to play in marshaling that funding into sustainable programs that improve student outcomes. They can ensure rigorous implementation of evidence-based initiatives, while also piloting and tracking the impact of innovative new approaches. Although it is too early to fully assess the effectiveness of postpandemic solutions to unfinished learning, the scope of action is already clear. The immediate imperative is to not only reopen schools and recover unfinished learning but also reimagine education systems for the long term. Across all of these priorities it will be critical to take a holistic approach, listening to students and parents and designing programs that meet academic and nonacademic needs alike.

What have we learned about unfinished learning?

As the 2020–21 school year began, just 40 percent of K–12 students were in districts that offered any in-person instruction. By the end of the year, more than 98 percent of students had access to some form of in-person learning, from the traditional five days a week to hybrid models. In the interim, districts oscillated among virtual, hybrid, and in-person learning as they balanced the need to keep students and staff safe with the need to provide an effective learning environment. Students faced multiple schedule changes, were assigned new teachers midyear, and struggled with glitchy internet connections and Zoom fatigue. This was a uniquely challenging year for teachers and students, and it is no surprise that it has left its mark—on student learning, and on student well-being.

As we analyze the cost of the pandemic, we use the term “unfinished learning” to capture the reality that students were not given the opportunity this year to complete all the learning they would have completed in a typical year. Some students who have disengaged from school altogether may have slipped backward, losing knowledge or skills they once had. The majority simply learned less than they would have in a typical year, but this is nonetheless important. Students who move on to the next grade unprepared are missing key building blocks of knowledge that are necessary for success, while students who repeat a year are much less likely to complete high school and move on to college. And it’s not just academic knowledge these students may miss out on. They are at risk of finishing school without the skills, behaviors, and mindsets to succeed in college or in the workforce. An accurate assessment of the depth and extent of unfinished learning will best enable districts and states to support students in catching up on the learning they missed and moving past the pandemic and into a successful future.

Students testing in 2021 were about ten points behind in math and nine points behind in reading, compared with matched students in previous years.

Unfinished learning is real—and inequitable

To assess student learning through the pandemic, we analyzed Curriculum Associates’ i-Ready in-school assessment results of more than 1.6 million elementary school students across more than 40 states. 2 The Curriculum Associates in-school sample consisted of 1.6 million K–6 students in mathematics and 1.5 million in reading. The math sample came from all 50 states, but 23 states accounted for 90 percent of the sample. The reading sample came from 46 states, with 21 states accounting for 90 percent of the sample. Florida accounted for 29 percent of the math and 30 percent of the reading sample. In general, states that had reopened schools are overweighted given the in-school nature of the assessment. We compared students’ performance in the spring of 2021 with the performance of similar students prior to the pandemic. 3 Specifically, we compared spring 2021 results to those of historically matched students in the springs of 2019, 2018, and 2017. Students testing in 2021 were about ten points behind in math and nine points behind in reading, compared with matched students in previous years.

To get a sense of the magnitude of these gaps, we translated these differences in scores to a more intuitive measure—months of learning. Although there is no perfect way to make this translation, we can get a sense of how far students are behind by comparing the levels students attained this spring with the growth in learning that usually occurs from one grade level to the next. We found that this cohort of students is five months behind in math and four months behind in reading, compared with where we would expect them to be based on historical data. 4 The conversion into months of learning compares students’ achievement in the spring of one grade level with their performance in the spring of the next grade level, treating this spring-to-spring difference in historical scores as a “year” of learning. It assumes a ten-month school year with a two-month summer vacation. Actual school schedules vary significantly, and i-Ready’s typical growth numbers for a “year” of learning are based on 30 weeks of actual instruction between the fall and the spring rather than on a spring-to-spring calendar-year comparison.

Unfinished learning did not vary significantly across elementary grades. Despite reports that remote learning was more challenging for early elementary students, 5 Marva Hinton, “Why teaching kindergarten online is so very, very hard,” Edutopia, October 21, 2020, edutopia.org. our results suggest the impact was just as meaningful for older elementary students. 6 While our analysis only includes results from students who tested in-school in the spring, many of these students were learning remotely for meaningful portions of the fall and the winter. We can hypothesize that perhaps younger elementary students received more help from parents and older siblings, and that older elementary students were more likely to be struggling alone.

It is also worth remembering that our numbers capture the “average” progress by grade level. Especially in early reading, this average can conceal a wide range of outcomes. Another way of cutting the data looks instead at which students have dropped further behind grade levels. A recent report suggests that more first and second graders have ended this year two or more grade levels below expectations than in any previous year. 7 Academic achievement at the end of the 2020–2021 school year , Curriculum Associates, June 2021, curriculumassociates.com. Given the major strides children at this age typically make in mastering reading, and the critical importance of early reading for later academic success, this is of particular concern.

While all types of students experienced unfinished learning, some groups were disproportionately affected. Students of color and low-income students suffered most. Students in majority-Black schools ended the school year six months behind in both math and reading, while students in majority-white schools ended up just four months behind in math and three months behind in reading. 8 To respect students’ privacy, we cannot isolate the race or income of individual students in our sample, but we can look at school-level demographics. Students in predominantly low-income schools and in urban locations also lost more learning during the pandemic than their peers in high-income rural and suburban schools (Exhibit 1).

In fall 2020, we projected that students could lose as much as five to ten months of learning in mathematics, and about half of that in reading, by the end of the school year. Spring assessment results came in toward the lower end of these projections, suggesting that districts and states were able to improve the quality of remote and hybrid learning through the 2020–21 school year and bring more students back into classrooms.

Indeed, if we look at the data over time, some interesting patterns emerge. 9 The composition of the fall student sample was different from that of the spring sample, because more students returned to in-person assessments in the spring. Some of the increase in unfinished learning from fall to spring could be because the spring assessment included previously virtual students, who may have struggled more during the school year. Even so, the spring data are the best reflection of unfinished learning at the end of the school year. Taking math as an example, as schools closed their buildings in the spring of 2020, students fell behind rapidly, learning almost no new math content over the final few months of the 2019–20 school year. Over the summer, we assume that they experienced the typical “summer slide” in which students lose some of the academic knowledge and skills they had learned the year before. Then they resumed learning through the 2020–21 school year, but at a slower pace than usual, resulting in five months of unfinished learning by the end of the year (Exhibit 2). 10 These lines simplify the pattern of typical learning through the year. In a typical year, students learn more in the fall and less in the spring, and only learn during periods of instruction (the chart includes the well-documented learning loss that happens during the summer, but does not include shorter holidays when students are not in school receiving instruction).

In reading, however, the story is somewhat different. As schools closed their buildings in March 2020, students continued to progress in reading, albeit at a slower pace. During the summer, we assume that students’ reading level stayed roughly flat, as in previous years. The pace of learning increased slightly over the 2020–21 school year, but the difference was not as great as it was in math, resulting in four months of unfinished learning by the end of the school year (Exhibit 3). Put another way, the initial shock in reading was less severe, but the improvements to remote and hybrid learning seem to have had less impact in reading than they did in math.

Before we celebrate the improvements in student trajectories between the initial school shutdowns and the subsequent year of learning, we should remember that these are still sobering numbers. On average, students who took the spring assessments in school are half a year behind in math, and nearly that in reading. For Black and Hispanic students, the losses are not only greater but also piled on top of historical inequities in opportunity and achievement (Exhibit 4).

Furthermore, these results likely represent an optimistic scenario. They reflect outcomes for students who took interim assessments in the spring in a school building 11 Students who took the assessment out of school are not included in our sample because we could not guarantee fidelity and comparability of results, given the change in the testing environment. Out-of-school students represent about a third of the students taking i-Ready assessments in the spring, and we will not have an accurate understanding of the pandemic’s impact on their learning until they return to school buildings, likely in the fall. —and thus exclude students who remained remote throughout the entire school year, and who may have experienced the most disruption to their schooling. 12 Initial results from Texas suggest that districts with mostly virtual instruction experienced more unfinished learning than those with mostly in-person instruction. The percent of students meeting math expectations dropped 32 percent in mostly virtual districts but just 9 percent in mostly in-person ones. See Reese Oxner, “Texas students’ standardized test scores dropped dramatically during the pandemic, especially in math,” Texas Tribune , June 28, 2021, texastribune.org. The Curriculum Associates data cover a broad variety of schools and states across the country, but are not fully representative, being overweighted for rural and southeastern states that were more likely to get students back into the classrooms this year. Finally, these data cover only elementary schools. They are silent on the academic impact of the pandemic for middle and high schoolers. However, data from school districts suggest that, even for older students, the pandemic has had a significant effect on learning. 13 For example, in Salt Lake City, the percentage of middle and high school students failing a class jumped by 60 percent, from 2,500 to 4,000, during the pandemic. To learn about increased failure rates across multiple districts from the Bay Area to New Mexico, Austin, and Hawaii, see Richard Fulton, “Failing Grades,” Inside Higher Ed , March 8, 2021, insidehighered.com.

The harm inflicted by the pandemic goes beyond academics

Students didn’t just lose academic learning during the pandemic. Some lost family members; others had caregivers who lost their jobs and sources of income; and almost all experienced social isolation.