Search form

A for and against essay.

Look at the essay and do the exercises to improve your writing skills.

Instructions

Do the preparation exercise first. Then do the other exercises.

Preparation

Check your understanding: multiple selection

Check your writing: reordering - essay structure, check your writing: typing - linking words, worksheets and downloads.

What are your views on reality TV? Are these types of shows popular in your country?

Sign up to our newsletter for LearnEnglish Teens

We will process your data to send you our newsletter and updates based on your consent. You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking the "unsubscribe" link at the bottom of every email. Read our privacy policy for more information.

Argumentative Essay Examples to Inspire You (+ Free Formula)

Have you ever been asked to explain your opinion on a controversial issue if you’re in college, you’ll likely have to write an argumentative essay at some point. this simple guide will help you get started..

.webp)

Table of contents

Meredith Sell

Have you ever been asked to explain your opinion on a controversial issue?

- Maybe your family got into a discussion about chemical pesticides

- Someone at work argues against investing resources into your project

- Your partner thinks intermittent fasting is the best way to lose weight and you disagree

Proving your point in an argumentative essay can be challenging, unless you are using a proven formula.

Argumentative essay formula & example

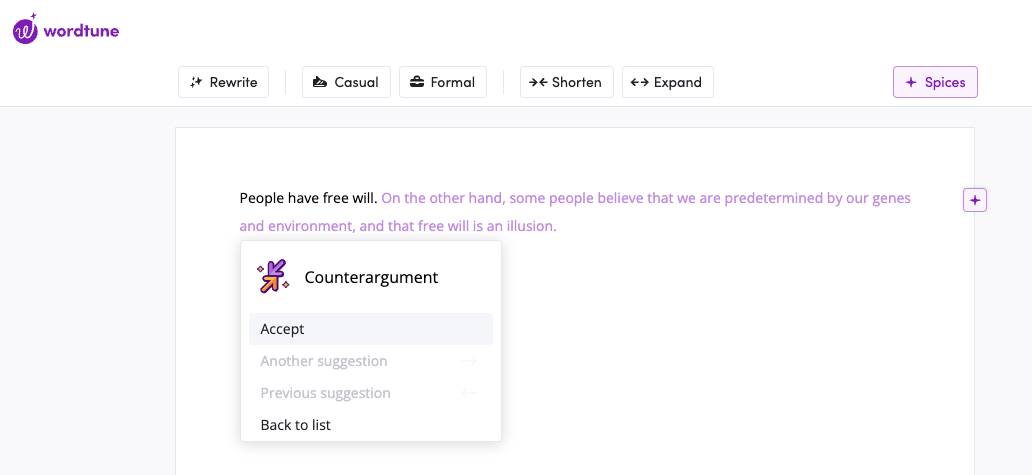

In the image below, you can see a recommended structure for argumentative essays. It starts with the topic sentence, which establishes the main idea of the essay. Next, this hypothesis is developed in the development stage. Then, the rebuttal, or the refutal of the main counter argument or arguments. Then, again, development of the rebuttal. This is followed by an example, and ends with a summary. This is a very basic structure, but it gives you a bird-eye-view of how a proper argumentative essay can be built.

Writing an argumentative essay (for a class, a news outlet, or just for fun) can help you improve your understanding of an issue and sharpen your thinking on the matter. Using researched facts and data, you can explain why you or others think the way you do, even while other reasonable people disagree.

Free AI argumentative essay generator > Free AI argumentative essay generator >

What Is an Argumentative Essay?

An argumentative essay is an explanatory essay that takes a side.

Instead of appealing to emotion and personal experience to change the reader’s mind, an argumentative essay uses logic and well-researched factual information to explain why the thesis in question is the most reasonable opinion on the matter.

Over several paragraphs or pages, the author systematically walks through:

- The opposition (and supporting evidence)

- The chosen thesis (and its supporting evidence)

At the end, the author leaves the decision up to the reader, trusting that the case they’ve made will do the work of changing the reader’s mind. Even if the reader’s opinion doesn’t change, they come away from the essay with a greater understanding of the perspective presented — and perhaps a better understanding of their original opinion.

All of that might make it seem like writing an argumentative essay is way harder than an emotionally-driven persuasive essay — but if you’re like me and much more comfortable spouting facts and figures than making impassioned pleas, you may find that an argumentative essay is easier to write.

Plus, the process of researching an argumentative essay means you can check your assumptions and develop an opinion that’s more based in reality than what you originally thought. I know for sure that my opinions need to be fact checked — don’t yours?

So how exactly do we write the argumentative essay?

How do you start an argumentative essay

First, gain a clear understanding of what exactly an argumentative essay is. To formulate a proper topic sentence, you have to be clear on your topic, and to explore it through research.

Students have difficulty starting an essay because the whole task seems intimidating, and they are afraid of spending too much time on the topic sentence. Experienced writers, however, know that there is no set time to spend on figuring out your topic. It's a real exploration that is based to a large extent on intuition.

6 Steps to Write an Argumentative Essay (Persuasion Formula)

Use this checklist to tackle your essay one step at a time:

1. Research an issue with an arguable question

To start, you need to identify an issue that well-informed people have varying opinions on. Here, it’s helpful to think of one core topic and how it intersects with another (or several other) issues. That intersection is where hot takes and reasonable (or unreasonable) opinions abound.

I find it helpful to stage the issue as a question.

For example:

Is it better to legislate the minimum size of chicken enclosures or to outlaw the sale of eggs from chickens who don’t have enough space?

Should snow removal policies focus more on effectively keeping roads clear for traffic or the environmental impacts of snow removal methods?

Once you have your arguable question ready, start researching the basic facts and specific opinions and arguments on the issue. Do your best to stay focused on gathering information that is directly relevant to your topic. Depending on what your essay is for, you may reference academic studies, government reports, or newspaper articles.

Research your opposition and the facts that support their viewpoint as much as you research your own position . You’ll need to address your opposition in your essay, so you’ll want to know their argument from the inside out.

2. Choose a side based on your research

You likely started with an inclination toward one side or the other, but your research should ultimately shape your perspective. So once you’ve completed the research, nail down your opinion and start articulating the what and why of your take.

What: I think it’s better to outlaw selling eggs from chickens whose enclosures are too small.

Why: Because if you regulate the enclosure size directly, egg producers outside of the government’s jurisdiction could ship eggs into your territory and put nearby egg producers out of business by offering better prices because they don’t have the added cost of larger enclosures.

This is an early form of your thesis and the basic logic of your argument. You’ll want to iterate on this a few times and develop a one-sentence statement that sums up the thesis of your essay.

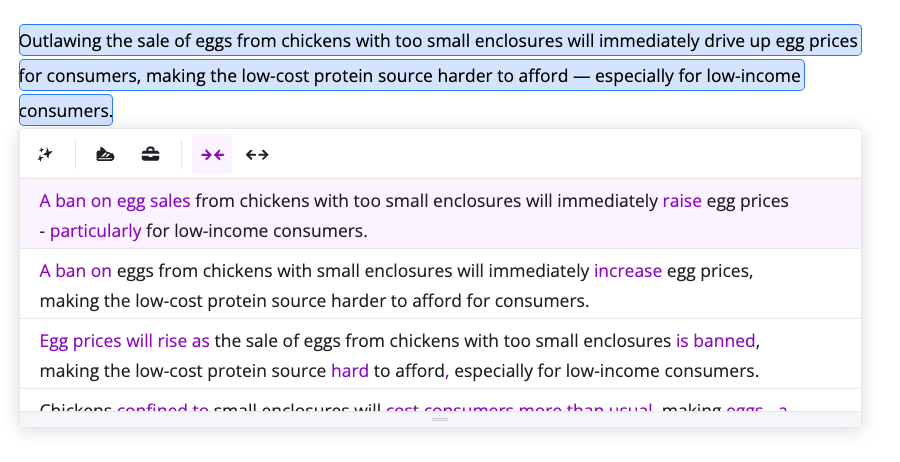

Thesis: Outlawing the sale of eggs from chickens with cramped living spaces is better for business than regulating the size of chicken enclosures.

Now that you’ve articulated your thesis , spell out the counterargument(s) as well. Putting your opposition’s take into words will help you throughout the rest of the essay-writing process. (You can start by choosing the counter argument option with Wordtune Spices .)

Counterargument: Outlawing the sale of eggs from chickens with too small enclosures will immediately drive up egg prices for consumers, making the low-cost protein source harder to afford — especially for low-income consumers.

There may be one main counterargument to articulate, or several. Write them all out and start thinking about how you’ll use evidence to address each of them or show why your argument is still the best option.

3. Organize the evidence — for your side and the opposition

You did all of that research for a reason. Now’s the time to use it.

Hopefully, you kept detailed notes in a document, complete with links and titles of all your source material. Go through your research document and copy the evidence for your argument and your opposition’s into another document.

List the main points of your argument. Then, below each point, paste the evidence that backs them up.

If you’re writing about chicken enclosures, maybe you found evidence that shows the spread of disease among birds kept in close quarters is worse than among birds who have more space. Or maybe you found information that says eggs from free-range chickens are more flavorful or nutritious. Put that information next to the appropriate part of your argument.

Repeat the process with your opposition’s argument: What information did you find that supports your opposition? Paste it beside your opposition’s argument.

You could also put information here that refutes your opposition, but organize it in a way that clearly tells you — at a glance — that the information disproves their point.

Counterargument: Outlawing the sale of eggs from chickens with too small enclosures will immediately drive up egg prices for consumers.

BUT: Sicknesses like avian flu spread more easily through small enclosures and could cause a shortage that would drive up egg prices naturally, so ensuring larger enclosures is still a better policy for consumers over the long term.

As you organize your research and see the evidence all together, start thinking through the best way to order your points.

Will it be better to present your argument all at once or to break it up with opposition claims you can quickly refute? Would some points set up other points well? Does a more complicated point require that the reader understands a simpler point first?

Play around and rearrange your notes to see how your essay might flow one way or another.

4. Freewrite or outline to think through your argument

Is your brain buzzing yet? At this point in the process, it can be helpful to take out a notebook or open a fresh document and dump whatever you’re thinking on the page.

Where should your essay start? What ground-level information do you need to provide your readers before you can dive into the issue?

Use your organized evidence document from step 3 to think through your argument from beginning to end, and determine the structure of your essay.

There are three typical structures for argumentative essays:

- Make your argument and tackle opposition claims one by one, as they come up in relation to the points of your argument - In this approach, the whole essay — from beginning to end — focuses on your argument, but as you make each point, you address the relevant opposition claims individually. This approach works well if your opposition’s views can be quickly explained and refuted and if they directly relate to specific points in your argument.

- Make the bulk of your argument, and then address the opposition all at once in a paragraph (or a few) - This approach puts the opposition in its own section, separate from your main argument. After you’ve made your case, with ample evidence to convince your readers, you write about the opposition, explaining their viewpoint and supporting evidence — and showing readers why the opposition’s argument is unconvincing. Once you’ve addressed the opposition, you write a conclusion that sums up why your argument is the better one.

- Open your essay by talking about the opposition and where it falls short. Build your entire argument to show how it is superior to that opposition - With this structure, you’re showing your readers “a better way” to address the issue. After opening your piece by showing how your opposition’s approaches fail, you launch into your argument, providing readers with ample evidence that backs you up.

As you think through your argument and examine your evidence document, consider which structure will serve your argument best. Sketch out an outline to give yourself a map to follow in the writing process. You could also rearrange your evidence document again to match your outline, so it will be easy to find what you need when you start writing.

5. Write your first draft

You have an outline and an organized document with all your points and evidence lined up and ready. Now you just have to write your essay.

In your first draft, focus on getting your ideas on the page. Your wording may not be perfect (whose is?), but you know what you’re trying to say — so even if you’re overly wordy and taking too much space to say what you need to say, put those words on the page.

Follow your outline, and draw from that evidence document to flesh out each point of your argument. Explain what the evidence means for your argument and your opposition. Connect the dots for your readers so they can follow you, point by point, and understand what you’re trying to say.

As you write, be sure to include:

1. Any background information your reader needs in order to understand the issue in question.

2. Evidence for both your argument and the counterargument(s). This shows that you’ve done your homework and builds trust with your reader, while also setting you up to make a more convincing argument. (If you find gaps in your research while you’re writing, Wordtune Spices can source statistics or historical facts on the fly!)

Get Wordtune for free > Get Wordtune for free >

3. A conclusion that sums up your overall argument and evidence — and leaves the reader with an understanding of the issue and its significance. This sort of conclusion brings your essay to a strong ending that doesn’t waste readers’ time, but actually adds value to your case.

6. Revise (with Wordtune)

The hard work is done: you have a first draft. Now, let’s fine tune your writing.

I like to step away from what I’ve written for a day (or at least a night of sleep) before attempting to revise. It helps me approach clunky phrases and rough transitions with fresh eyes. If you don’t have that luxury, just get away from your computer for a few minutes — use the bathroom, do some jumping jacks, eat an apple — and then come back and read through your piece.

As you revise, make sure you …

- Get the facts right. An argument with false evidence falls apart pretty quickly, so check your facts to make yours rock solid.

- Don’t misrepresent the opposition or their evidence. If someone who holds the opposing view reads your essay, they should affirm how you explain their side — even if they disagree with your rebuttal.

- Present a case that builds over the course of your essay, makes sense, and ends on a strong note. One point should naturally lead to the next. Your readers shouldn’t feel like you’re constantly changing subjects. You’re making a variety of points, but your argument should feel like a cohesive whole.

- Paraphrase sources and cite them appropriately. Did you skip citations when writing your first draft? No worries — you can add them now. And check that you don’t overly rely on quotations. (Need help paraphrasing? Wordtune can help. Simply highlight the sentence or phrase you want to adjust and sort through Wordtune’s suggestions.)

- Tighten up overly wordy explanations and sharpen any convoluted ideas. Wordtune makes a great sidekick for this too 😉

Words to start an argumentative essay

The best way to introduce a convincing argument is to provide a strong thesis statement . These are the words I usually use to start an argumentative essay:

- It is indisputable that the world today is facing a multitude of issues

- With the rise of ____, the potential to make a positive difference has never been more accessible

- It is essential that we take action now and tackle these issues head-on

- it is critical to understand the underlying causes of the problems standing before us

- Opponents of this idea claim

- Those who are against these ideas may say

- Some people may disagree with this idea

- Some people may say that ____, however

When refuting an opposing concept, use:

- These researchers have a point in thinking

- To a certain extent they are right

- After seeing this evidence, there is no way one can agree with this idea

- This argument is irrelevant to the topic

Are you convinced by your own argument yet? Ready to brave the next get-together where everyone’s talking like they know something about intermittent fasting , chicken enclosures , or snow removal policies?

Now if someone asks you to explain your evidence-based but controversial opinion, you can hand them your essay and ask them to report back after they’ve read it.

Share This Article:

Metaphor vs. Simile: What’s the Difference? (+ Examples)

10 Ways to Effectively Manage Your Stress at University

9 Tips to Improve Your Job Application

Looking for fresh content, thank you your submission has been received.

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, 3 strong argumentative essay examples, analyzed.

General Education

Need to defend your opinion on an issue? Argumentative essays are one of the most popular types of essays you’ll write in school. They combine persuasive arguments with fact-based research, and, when done well, can be powerful tools for making someone agree with your point of view. If you’re struggling to write an argumentative essay or just want to learn more about them, seeing examples can be a big help.

After giving an overview of this type of essay, we provide three argumentative essay examples. After each essay, we explain in-depth how the essay was structured, what worked, and where the essay could be improved. We end with tips for making your own argumentative essay as strong as possible.

What Is an Argumentative Essay?

An argumentative essay is an essay that uses evidence and facts to support the claim it’s making. Its purpose is to persuade the reader to agree with the argument being made.

A good argumentative essay will use facts and evidence to support the argument, rather than just the author’s thoughts and opinions. For example, say you wanted to write an argumentative essay stating that Charleston, SC is a great destination for families. You couldn’t just say that it’s a great place because you took your family there and enjoyed it. For it to be an argumentative essay, you need to have facts and data to support your argument, such as the number of child-friendly attractions in Charleston, special deals you can get with kids, and surveys of people who visited Charleston as a family and enjoyed it. The first argument is based entirely on feelings, whereas the second is based on evidence that can be proven.

The standard five paragraph format is common, but not required, for argumentative essays. These essays typically follow one of two formats: the Toulmin model or the Rogerian model.

- The Toulmin model is the most common. It begins with an introduction, follows with a thesis/claim, and gives data and evidence to support that claim. This style of essay also includes rebuttals of counterarguments.

- The Rogerian model analyzes two sides of an argument and reaches a conclusion after weighing the strengths and weaknesses of each.

3 Good Argumentative Essay Examples + Analysis

Below are three examples of argumentative essays, written by yours truly in my school days, as well as analysis of what each did well and where it could be improved.

Argumentative Essay Example 1

Proponents of this idea state that it will save local cities and towns money because libraries are expensive to maintain. They also believe it will encourage more people to read because they won’t have to travel to a library to get a book; they can simply click on what they want to read and read it from wherever they are. They could also access more materials because libraries won’t have to buy physical copies of books; they can simply rent out as many digital copies as they need.

However, it would be a serious mistake to replace libraries with tablets. First, digital books and resources are associated with less learning and more problems than print resources. A study done on tablet vs book reading found that people read 20-30% slower on tablets, retain 20% less information, and understand 10% less of what they read compared to people who read the same information in print. Additionally, staring too long at a screen has been shown to cause numerous health problems, including blurred vision, dizziness, dry eyes, headaches, and eye strain, at much higher instances than reading print does. People who use tablets and mobile devices excessively also have a higher incidence of more serious health issues such as fibromyalgia, shoulder and back pain, carpal tunnel syndrome, and muscle strain. I know that whenever I read from my e-reader for too long, my eyes begin to feel tired and my neck hurts. We should not add to these problems by giving people, especially young people, more reasons to look at screens.

Second, it is incredibly narrow-minded to assume that the only service libraries offer is book lending. Libraries have a multitude of benefits, and many are only available if the library has a physical location. Some of these benefits include acting as a quiet study space, giving people a way to converse with their neighbors, holding classes on a variety of topics, providing jobs, answering patron questions, and keeping the community connected. One neighborhood found that, after a local library instituted community events such as play times for toddlers and parents, job fairs for teenagers, and meeting spaces for senior citizens, over a third of residents reported feeling more connected to their community. Similarly, a Pew survey conducted in 2015 found that nearly two-thirds of American adults feel that closing their local library would have a major impact on their community. People see libraries as a way to connect with others and get their questions answered, benefits tablets can’t offer nearly as well or as easily.

While replacing libraries with tablets may seem like a simple solution, it would encourage people to spend even more time looking at digital screens, despite the myriad issues surrounding them. It would also end access to many of the benefits of libraries that people have come to rely on. In many areas, libraries are such an important part of the community network that they could never be replaced by a simple object.

The author begins by giving an overview of the counter-argument, then the thesis appears as the first sentence in the third paragraph. The essay then spends the rest of the paper dismantling the counter argument and showing why readers should believe the other side.

What this essay does well:

- Although it’s a bit unusual to have the thesis appear fairly far into the essay, it works because, once the thesis is stated, the rest of the essay focuses on supporting it since the counter-argument has already been discussed earlier in the paper.

- This essay includes numerous facts and cites studies to support its case. By having specific data to rely on, the author’s argument is stronger and readers will be more inclined to agree with it.

- For every argument the other side makes, the author makes sure to refute it and follow up with why her opinion is the stronger one. In order to make a strong argument, it’s important to dismantle the other side, which this essay does this by making the author's view appear stronger.

- This is a shorter paper, and if it needed to be expanded to meet length requirements, it could include more examples and go more into depth with them, such as by explaining specific cases where people benefited from local libraries.

- Additionally, while the paper uses lots of data, the author also mentions their own experience with using tablets. This should be removed since argumentative essays focus on facts and data to support an argument, not the author’s own opinion or experiences. Replacing that with more data on health issues associated with screen time would strengthen the essay.

- Some of the points made aren't completely accurate , particularly the one about digital books being cheaper. It actually often costs a library more money to rent out numerous digital copies of a book compared to buying a single physical copy. Make sure in your own essay you thoroughly research each of the points and rebuttals you make, otherwise you'll look like you don't know the issue that well.

Argumentative Essay Example 2

There are multiple drugs available to treat malaria, and many of them work well and save lives, but malaria eradication programs that focus too much on them and not enough on prevention haven’t seen long-term success in Sub-Saharan Africa. A major program to combat malaria was WHO’s Global Malaria Eradication Programme. Started in 1955, it had a goal of eliminating malaria in Africa within the next ten years. Based upon previously successful programs in Brazil and the United States, the program focused mainly on vector control. This included widely distributing chloroquine and spraying large amounts of DDT. More than one billion dollars was spent trying to abolish malaria. However, the program suffered from many problems and in 1969, WHO was forced to admit that the program had not succeeded in eradicating malaria. The number of people in Sub-Saharan Africa who contracted malaria as well as the number of malaria deaths had actually increased over 10% during the time the program was active.

One of the major reasons for the failure of the project was that it set uniform strategies and policies. By failing to consider variations between governments, geography, and infrastructure, the program was not nearly as successful as it could have been. Sub-Saharan Africa has neither the money nor the infrastructure to support such an elaborate program, and it couldn’t be run the way it was meant to. Most African countries don't have the resources to send all their people to doctors and get shots, nor can they afford to clear wetlands or other malaria prone areas. The continent’s spending per person for eradicating malaria was just a quarter of what Brazil spent. Sub-Saharan Africa simply can’t rely on a plan that requires more money, infrastructure, and expertise than they have to spare.

Additionally, the widespread use of chloroquine has created drug resistant parasites which are now plaguing Sub-Saharan Africa. Because chloroquine was used widely but inconsistently, mosquitoes developed resistance, and chloroquine is now nearly completely ineffective in Sub-Saharan Africa, with over 95% of mosquitoes resistant to it. As a result, newer, more expensive drugs need to be used to prevent and treat malaria, which further drives up the cost of malaria treatment for a region that can ill afford it.

Instead of developing plans to treat malaria after the infection has incurred, programs should focus on preventing infection from occurring in the first place. Not only is this plan cheaper and more effective, reducing the number of people who contract malaria also reduces loss of work/school days which can further bring down the productivity of the region.

One of the cheapest and most effective ways of preventing malaria is to implement insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs). These nets provide a protective barrier around the person or people using them. While untreated bed nets are still helpful, those treated with insecticides are much more useful because they stop mosquitoes from biting people through the nets, and they help reduce mosquito populations in a community, thus helping people who don’t even own bed nets. Bed nets are also very effective because most mosquito bites occur while the person is sleeping, so bed nets would be able to drastically reduce the number of transmissions during the night. In fact, transmission of malaria can be reduced by as much as 90% in areas where the use of ITNs is widespread. Because money is so scarce in Sub-Saharan Africa, the low cost is a great benefit and a major reason why the program is so successful. Bed nets cost roughly 2 USD to make, last several years, and can protect two adults. Studies have shown that, for every 100-1000 more nets are being used, one less child dies of malaria. With an estimated 300 million people in Africa not being protected by mosquito nets, there’s the potential to save three million lives by spending just a few dollars per person.

Reducing the number of people who contract malaria would also reduce poverty levels in Africa significantly, thus improving other aspects of society like education levels and the economy. Vector control is more effective than treatment strategies because it means fewer people are getting sick. When fewer people get sick, the working population is stronger as a whole because people are not put out of work from malaria, nor are they caring for sick relatives. Malaria-afflicted families can typically only harvest 40% of the crops that healthy families can harvest. Additionally, a family with members who have malaria spends roughly a quarter of its income treatment, not including the loss of work they also must deal with due to the illness. It’s estimated that malaria costs Africa 12 billion USD in lost income every year. A strong working population creates a stronger economy, which Sub-Saharan Africa is in desperate need of.

This essay begins with an introduction, which ends with the thesis (that malaria eradication plans in Sub-Saharan Africa should focus on prevention rather than treatment). The first part of the essay lays out why the counter argument (treatment rather than prevention) is not as effective, and the second part of the essay focuses on why prevention of malaria is the better path to take.

- The thesis appears early, is stated clearly, and is supported throughout the rest of the essay. This makes the argument clear for readers to understand and follow throughout the essay.

- There’s lots of solid research in this essay, including specific programs that were conducted and how successful they were, as well as specific data mentioned throughout. This evidence helps strengthen the author’s argument.

- The author makes a case for using expanding bed net use over waiting until malaria occurs and beginning treatment, but not much of a plan is given for how the bed nets would be distributed or how to ensure they’re being used properly. By going more into detail of what she believes should be done, the author would be making a stronger argument.

- The introduction of the essay does a good job of laying out the seriousness of the problem, but the conclusion is short and abrupt. Expanding it into its own paragraph would give the author a final way to convince readers of her side of the argument.

Argumentative Essay Example 3

There are many ways payments could work. They could be in the form of a free-market approach, where athletes are able to earn whatever the market is willing to pay them, it could be a set amount of money per athlete, or student athletes could earn income from endorsements, autographs, and control of their likeness, similar to the way top Olympians earn money.

Proponents of the idea believe that, because college athletes are the ones who are training, participating in games, and bringing in audiences, they should receive some sort of compensation for their work. If there were no college athletes, the NCAA wouldn’t exist, college coaches wouldn’t receive there (sometimes very high) salaries, and brands like Nike couldn’t profit from college sports. In fact, the NCAA brings in roughly $1 billion in revenue a year, but college athletes don’t receive any of that money in the form of a paycheck. Additionally, people who believe college athletes should be paid state that paying college athletes will actually encourage them to remain in college longer and not turn pro as quickly, either by giving them a way to begin earning money in college or requiring them to sign a contract stating they’ll stay at the university for a certain number of years while making an agreed-upon salary.

Supporters of this idea point to Zion Williamson, the Duke basketball superstar, who, during his freshman year, sustained a serious knee injury. Many argued that, even if he enjoyed playing for Duke, it wasn’t worth risking another injury and ending his professional career before it even began for a program that wasn’t paying him. Williamson seems to have agreed with them and declared his eligibility for the NCAA draft later that year. If he was being paid, he may have stayed at Duke longer. In fact, roughly a third of student athletes surveyed stated that receiving a salary while in college would make them “strongly consider” remaining collegiate athletes longer before turning pro.

Paying athletes could also stop the recruitment scandals that have plagued the NCAA. In 2018, the NCAA stripped the University of Louisville's men's basketball team of its 2013 national championship title because it was discovered coaches were using sex workers to entice recruits to join the team. There have been dozens of other recruitment scandals where college athletes and recruits have been bribed with anything from having their grades changed, to getting free cars, to being straight out bribed. By paying college athletes and putting their salaries out in the open, the NCAA could end the illegal and underhanded ways some schools and coaches try to entice athletes to join.

People who argue against the idea of paying college athletes believe the practice could be disastrous for college sports. By paying athletes, they argue, they’d turn college sports into a bidding war, where only the richest schools could afford top athletes, and the majority of schools would be shut out from developing a talented team (though some argue this already happens because the best players often go to the most established college sports programs, who typically pay their coaches millions of dollars per year). It could also ruin the tight camaraderie of many college teams if players become jealous that certain teammates are making more money than they are.

They also argue that paying college athletes actually means only a small fraction would make significant money. Out of the 350 Division I athletic departments, fewer than a dozen earn any money. Nearly all the money the NCAA makes comes from men’s football and basketball, so paying college athletes would make a small group of men--who likely will be signed to pro teams and begin making millions immediately out of college--rich at the expense of other players.

Those against paying college athletes also believe that the athletes are receiving enough benefits already. The top athletes already receive scholarships that are worth tens of thousands per year, they receive free food/housing/textbooks, have access to top medical care if they are injured, receive top coaching, get travel perks and free gear, and can use their time in college as a way to capture the attention of professional recruiters. No other college students receive anywhere near as much from their schools.

People on this side also point out that, while the NCAA brings in a massive amount of money each year, it is still a non-profit organization. How? Because over 95% of those profits are redistributed to its members’ institutions in the form of scholarships, grants, conferences, support for Division II and Division III teams, and educational programs. Taking away a significant part of that revenue would hurt smaller programs that rely on that money to keep running.

While both sides have good points, it’s clear that the negatives of paying college athletes far outweigh the positives. College athletes spend a significant amount of time and energy playing for their school, but they are compensated for it by the scholarships and perks they receive. Adding a salary to that would result in a college athletic system where only a small handful of athletes (those likely to become millionaires in the professional leagues) are paid by a handful of schools who enter bidding wars to recruit them, while the majority of student athletics and college athletic programs suffer or even shut down for lack of money. Continuing to offer the current level of benefits to student athletes makes it possible for as many people to benefit from and enjoy college sports as possible.

This argumentative essay follows the Rogerian model. It discusses each side, first laying out multiple reasons people believe student athletes should be paid, then discussing reasons why the athletes shouldn’t be paid. It ends by stating that college athletes shouldn’t be paid by arguing that paying them would destroy college athletics programs and cause them to have many of the issues professional sports leagues have.

- Both sides of the argument are well developed, with multiple reasons why people agree with each side. It allows readers to get a full view of the argument and its nuances.

- Certain statements on both sides are directly rebuffed in order to show where the strengths and weaknesses of each side lie and give a more complete and sophisticated look at the argument.

- Using the Rogerian model can be tricky because oftentimes you don’t explicitly state your argument until the end of the paper. Here, the thesis doesn’t appear until the first sentence of the final paragraph. That doesn’t give readers a lot of time to be convinced that your argument is the right one, compared to a paper where the thesis is stated in the beginning and then supported throughout the paper. This paper could be strengthened if the final paragraph was expanded to more fully explain why the author supports the view, or if the paper had made it clearer that paying athletes was the weaker argument throughout.

3 Tips for Writing a Good Argumentative Essay

Now that you’ve seen examples of what good argumentative essay samples look like, follow these three tips when crafting your own essay.

#1: Make Your Thesis Crystal Clear

The thesis is the key to your argumentative essay; if it isn’t clear or readers can’t find it easily, your entire essay will be weak as a result. Always make sure that your thesis statement is easy to find. The typical spot for it is the final sentence of the introduction paragraph, but if it doesn’t fit in that spot for your essay, try to at least put it as the first or last sentence of a different paragraph so it stands out more.

Also make sure that your thesis makes clear what side of the argument you’re on. After you’ve written it, it’s a great idea to show your thesis to a couple different people--classmates are great for this. Just by reading your thesis they should be able to understand what point you’ll be trying to make with the rest of your essay.

#2: Show Why the Other Side Is Weak

When writing your essay, you may be tempted to ignore the other side of the argument and just focus on your side, but don’t do this. The best argumentative essays really tear apart the other side to show why readers shouldn’t believe it. Before you begin writing your essay, research what the other side believes, and what their strongest points are. Then, in your essay, be sure to mention each of these and use evidence to explain why they’re incorrect/weak arguments. That’ll make your essay much more effective than if you only focused on your side of the argument.

#3: Use Evidence to Support Your Side

Remember, an essay can’t be an argumentative essay if it doesn’t support its argument with evidence. For every point you make, make sure you have facts to back it up. Some examples are previous studies done on the topic, surveys of large groups of people, data points, etc. There should be lots of numbers in your argumentative essay that support your side of the argument. This will make your essay much stronger compared to only relying on your own opinions to support your argument.

Summary: Argumentative Essay Sample

Argumentative essays are persuasive essays that use facts and evidence to support their side of the argument. Most argumentative essays follow either the Toulmin model or the Rogerian model. By reading good argumentative essay examples, you can learn how to develop your essay and provide enough support to make readers agree with your opinion. When writing your essay, remember to always make your thesis clear, show where the other side is weak, and back up your opinion with data and evidence.

What's Next?

Do you need to write an argumentative essay as well? Check out our guide on the best argumentative essay topics for ideas!

You'll probably also need to write research papers for school. We've got you covered with 113 potential topics for research papers.

Your college admissions essay may end up being one of the most important essays you write. Follow our step-by-step guide on writing a personal statement to have an essay that'll impress colleges.

Christine graduated from Michigan State University with degrees in Environmental Biology and Geography and received her Master's from Duke University. In high school she scored in the 99th percentile on the SAT and was named a National Merit Finalist. She has taught English and biology in several countries.

Student and Parent Forum

Our new student and parent forum, at ExpertHub.PrepScholar.com , allow you to interact with your peers and the PrepScholar staff. See how other students and parents are navigating high school, college, and the college admissions process. Ask questions; get answers.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

160 Good Argumentative Essay Topics for Students in 2024

April 3, 2024

The skill of writing an excellent argumentative essay is a crucial one for every high school or college student to master. In sum, argumentative essays teach students how to organize their thoughts logically and present them in a convincing way. This skill is helpful not only for those pursuing degrees in law , international relations , or public policy , but for any student who wishes to develop their critical thinking faculties. In this article, we’ll cover what makes a good argument essay and offer several argumentative essay topics for high school and college students. Let’s begin!

What is an Argumentative Essay?

An argumentative essay is an essay that uses research to present a reasoned argument on a particular subject . As with the persuasive essay , the purpose of an argumentative essay is to sway the reader to the writer’s position. However, a strong persuasive essay makes its point through diligent research and emotion while a strong argumentative essay should be based solely on facts, not feelings.

Moreover, each fact should be supported by clear evidence from credible sources . Furthermore, a good argumentative essay will have an easy-to-follow structure. When organizing your argumentative essay, use this format as a guide:

- Introduction

- Supporting body paragraphs

- Paragraph(s) addressing common counterarguments

Argumentative Essay Format

In the introduction , the writer presents their position and thesis statement —a sentence that summarizes the paper’s main points. The body paragraphs then draw upon supporting evidence to back up this initial statement, with each paragraph focusing on its own point. The length of your paper will determine the amount of examples you need. In general, you’ll likely need at least two to three. Additionally, your examples should be as detailed as possible, citing specific research, case studies, statistics, or anecdotes.

In the counterargument paragraph , the writer acknowledges and refutes opposing viewpoints. Finally, in the conclusion , the writer restates the main argument made in the thesis statement and summarizes the points of the essay. Additionally, the conclusion may offer a final proposal to persuade the reader of the essay’s position.

How to Write an Effective Argumentative Essay, Step by Step

- Choose your topic. Use the list below to help you pick a topic. Ideally, a good argumentative essay topic will be meaningful to you—writing is always stronger when you are interested in the subject matter. In addition, the topic should be complex with plenty of “pro” and “con” arguments. Avoid choosing a topic that is either widely accepted as fact or too narrow. For example, “Is the earth round?” would not be a solid choice.

- Research. Use the library, the web, and any other resources to gather information about your argumentative essay topic. Research widely but smartly. As you go, take organized notes, marking the source of every quote and where it may fit in the scheme of your larger essay. Moreover, remember to look for (and research) possible counterarguments.

- Outline . Using the argument essay format above, create an outline for your essay. Then, brainstorm a thesis statement covering your argument’s main points, and begin to put your examples in order, focusing on logical flow. It’s often best to place your strongest example last.

- Write . Draw on your research and outline to create a first draft. Remember, your first draft doesn’t need to be perfect. (As Voltaire says, “Perfect is the enemy of good.”) Accordingly, just focus on getting the words down on paper.

- Does my thesis statement need to be adjusted?

- Which examples feel strongest? Weakest?

- Do the transitions flow smoothly?

- Do I have a strong opening paragraph?

- Does the conclusion reinforce my argument?

Tips for Revising an Argument Essay

Evaluating your own work can be difficult, so you might consider the following strategies:

- Read your work aloud to yourself.

- Record yourself reading your paper, and listen to the recording.

- Reverse outline your paper. Firstly, next to each paragraph, write a short summary of that paragraph’s main points/idea. Then, read through your reverse outline. Does it have a logical flow? If not, where should you adjust?

- Print out your paper and cut it into paragraphs. What happens when you rearrange the paragraphs?

Good Argumentative Essay Topics for Middle School, High School, and College Students

Family argumentative essay topics.

- Should the government provide financial incentives for families to have children to address the declining birth rate?

- Should we require parents to provide their children with a certain level of nutrition and physical activity to prevent childhood obesity?

- Should parents implement limits on how much time their children spend playing video games?

- Should cell phones be banned from family/holiday gatherings?

- Should we hold parents legally responsible for their children’s actions?

- Should children have the right to sue their parents for neglect?

- Should parents have the right to choose their child’s religion?

- Are spanking and other forms of physical punishment an effective method of discipline?

- Should courts allow children to choose where they live in cases of divorce?

- Should parents have the right to monitor teens’ activity on social media?

- Should parents control their child’s medical treatment, even if it goes against the child’s wishes?

- Should parents be allowed to post pictures of their children on social media without their consent?

- Should fathers have a legal say in whether their partners do or do not receive an abortion?

- Can television have positive developmental benefits on children?

- Should the driving age be raised to prevent teen car accidents?

- Should adult children be legally required to care for their aging parents?

Education Argument Essay Topics

- Should schools ban the use of technology like ChatGPT?

- Are zoos unethical, or necessary for conservation and education?

- To what degree should we hold parents responsible in the event of a school shooting?

- Should schools offer students a set number of mental health days?

- Should school science curriculums offer a course on combating climate change?

- Should public libraries be allowed to ban certain books? If so, what types?

- What role, if any, should prayer play in public schools?

- Should schools push to abolish homework?

- Are gifted and talented programs in schools more harmful than beneficial due to their exclusionary nature?

- Should universities do away with Greek life?

- Should schools remove artwork, such as murals, that some perceive as offensive?

- Should the government grant parents the right to choose alternative education options for their children and use taxpayer funds to support these options?

- Is homeschooling better than traditional schooling for children’s academic and social development?

- Should we require schools to teach sex education to reduce teen pregnancy rates?

- Should we require schools to provide sex education that includes information about both homosexual and heterosexual relationships?

- Should colleges use affirmative action and other race-conscious policies to address diversity on campus?

- Should public schools remove the line “under God” from the Pledge of Allegiance?

- Should college admissions officers be allowed to look at students’ social media accounts?

- Should schools abolish their dress codes, many of which unfairly target girls, LGBTQ students, and students of color?

- Should schools be required to stock free period products in bathrooms?

- Should legacy students receive preferential treatment during the college admissions process?

- Are school “voluntourism” trips ethical?

Government Argumentative Essay Topics

- Should the U.S. decriminalize prostitution?

- Should the U.S. issue migration visas to all eligible applicants?

- Should the federal government cancel all student loan debt?

- Should we lower the minimum voting age? If so, to what?

- Should the federal government abolish all laws penalizing drug production and use?

- Should the U.S. use its military power to deter a Chinese invasion of Taiwan?

- Should the U.S. supply Ukraine with further military intelligence and supplies?

- Should the North and South of the U.S. split up into two regions?

- Should Americans hold up nationalism as a critical value?

- Should we permit Supreme Court justices to hold their positions indefinitely?

- Should Supreme Court justices be democratically elected?

- Is the Electoral College still a productive approach to electing the U.S. president?

- Should the U.S. implement a national firearm registry?

- Is it ethical for countries like China and Israel to mandate compulsory military service for all citizens?

- Should the U.S. government implement a ranked-choice voting system?

- Should institutions that benefited from slavery be required to provide reparations?

- Based on the 1619 project, should history classes change how they teach about the founding of the U.S.?

- Should term limits be imposed on Senators and Representatives? If so, how long?

- Should women be allowed into special forces units?

- Should the federal government implement stronger, universal firearm licensing laws?

- Do public sex offender registries help prevent future sex crimes?

- Should the government be allowed to regulate family size?

- Should all adults legally be considered mandated reporters?

- Should the government fund public universities to make higher education more accessible to low-income students?

- Should the government fund universal preschool to improve children’s readiness for kindergarten?

Health/Bioethics Argumentative Essay Topics

- Should the U.S. government offer its own healthcare plan?

- In the case of highly infectious pandemics, should we focus on individual freedoms or public safety when implementing policies to control the spread?

- Should we legally require parents to vaccinate their children to protect public health?

- Is it ethical for parents to use genetic engineering to create “designer babies” with specific physical and intellectual traits?

- Should the government fund research on embryonic stem cells for medical treatments?

- Should the government legalize assisted suicide for terminally ill patients?

- Should organ donation be mandatory?

- Is cloning animals ethical?

- Should cancer screenings start earlier? If so, what age?

- Is surrogacy ethical?

- Should birth control require a prescription?

- Should minors have access to emergency contraception?

- Should hospitals be for-profit or nonprofit institutions?

Good Argumentative Essay Topics — Continued

Social media argumentative essay topics.

- Should the federal government increase its efforts to minimize the negative impact of social media?

- Do social media and smartphones strengthen one’s relationships?

- Should antitrust regulators take action to limit the size of big tech companies?

- Should social media platforms ban political advertisements?

- Should the federal government hold social media companies accountable for instances of hate speech discovered on their platforms?

- Do apps such as TikTok and Instagram ultimately worsen the mental well-being of teenagers?

- Should governments oversee how social media platforms manage their users’ data?

- Should social media platforms like Facebook enforce a minimum age requirement for users?

- Should social media companies be held responsible for cases of cyberbullying?

- Should the United States ban TikTok?

- Is social media harmful to children?

- Should employers screen applicants’ social media accounts during the hiring process?

Religion Argument Essay Topics

- Should religious institutions be tax-exempt?

- Should religious symbols such as the hijab or crucifix be allowed in public spaces?

- Should religious freedoms be protected, even when they conflict with secular laws?

- Should the government regulate religious practices?

- Should we allow churches to engage in political activities?

- Religion: a force for good or evil in the world?

- Should the government provide funding for religious schools?

- Is it ethical for healthcare providers to deny abortions based on religious beliefs?

- Should religious organizations be allowed to discriminate in their hiring practices?

- Should we allow people to opt out of medical treatments based on their religious beliefs?

- Should the U.S. government hold religious organizations accountable for cases of sexual abuse within their community?

- Should religious beliefs be exempt from anti-discrimination laws?

- Should religious individuals be allowed to refuse services to others based on their beliefs or lifestyles? (As in this famous case .)

- Should the US ban religion-based federal holidays?

- Should public schools be allowed to teach children about religious holidays?

Science Argument Essay Topics

- Would the world be safer if we eliminated nuclear weapons?

- Should scientists bring back extinct animals? If so, which ones?

- Should we hold companies fiscally responsible for their carbon footprint?

- Should we ban pesticides in favor of organic farming methods?

- Should the federal government ban all fossil fuels, despite the potential economic impact on specific industries and communities?

- What renewable energy source should the U.S. invest more money in?

- Should the FDA outlaw GMOs?

- Should we worry about artificial intelligence surpassing human intelligence?

- Should the alternative medicine industry be more stringently regulated?

- Is colonizing Mars a viable option?

- Is the animal testing worth the potential to save human lives?

Sports Argument Essay Topics

- Should colleges compensate student-athletes?

- How should sports teams and leagues address the gender pay gap?

- Should youth sports teams do away with scorekeeping?

- Should we ban aggressive contact sports like boxing and MMA?

- Should professional sports associations mandate that athletes stand during the national anthem?

- Should high schools require their student-athletes to maintain a certain GPA?

- Should transgender athletes compete in sports according to their gender identity?

- Should schools ban football due to the inherent danger it poses to players?

- Should performance-enhancing drugs be allowed in sports?

- Do participation trophies foster entitlement and unrealistic expectations?

- Should sports teams be divided by gender?

- Should professional athletes be allowed to compete in the Olympics?

- Should women be allowed on NFL teams?

Technology Argumentative Essay Topics

- Should sites like DALL-E compensate the artists whose work it was trained on?

- Should the federal government make human exploration of space a more significant priority?

- Is it ethical for the government to use surveillance technology to monitor citizens?

- Should websites require proof of age from their users? If so, what age?

- Should we consider A.I.-generated images and text pieces of art?

- Does the use of facial recognition technology violate individuals’ privacy?

- Is online learning as effective as in-person learning?

- Does computing harm the environment?

- Should buying, sharing, and selling collected personal data be illegal?

- Are electric cars really better for the environment?

- Should car companies be held responsible for self-driving car accidents?

- Should private jets be banned?

- Do violent video games contribute to real-life violence?

Business Argument Essay Topics

- Should the U.S. government phase out the use of paper money in favor of a fully digital currency system?

- Should the federal government abolish its patent and copyright laws?

- Should we replace the Federal Reserve with free-market institutions?

- Is free-market ideology responsible for the U.S. economy’s poor performance over the past decade?

- Will cryptocurrencies overtake natural resources like gold and silver?

- Is capitalism the best economic system? What system would be better?

- Should the U.S. government enact a universal basic income?

- Should we require companies to provide paid parental leave to their employees?

- Should the government raise the minimum wage? If so, to what?

- Should antitrust regulators break up large companies to promote competition?

- Is it ethical for companies to prioritize profits over social responsibility?

- Should gig-economy workers like Uber and Lyft drivers be considered employees or independent contractors?

- Should the federal government regulate the gig economy to ensure fair treatment of workers?

- Should the government require companies to disclose the environmental impact of their products?

- Should companies be allowed to fire employees based on political views or activities?

- Should tipping practices be phased out?

- Should employees who choose not to have children be given the same amount of paid leave as parents?

- Should MLMs (multi-level marketing companies) be illegal?

- Should employers be allowed to factor tattoos and personal appearance into hiring decisions?

In Conclusion – Argument Essay Topics

Using the tips above, you can effectively structure and pen a compelling argumentative essay that will wow your instructor and classmates. Remember to craft a thesis statement that offers readers a roadmap through your essay, draw on your sources wisely to back up any claims, and read through your paper several times before it’s due to catch any last-minute proofreading errors. With time, diligence, and patience, your essay will be the most outstanding assignment you’ve ever turned in…until the next one rolls around.

Looking for more fresh and engaging topics for use in the classroom? You might consider checking out the following:

- 125 Good Debate Topics for High School Students

- 150 Good Persuasive Speech Topics

- 7 Best Places to Study

- Guide to the IB Extended Essay

- How to Write the AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay

- AP Lit Reading List

- How to Write the AP Lang Synthesis Essay

- 49 Most Interesting Biology Research Topics

- High School Success

Lauren Green

With a Bachelor of Arts in Creative Writing from Columbia University and an MFA in Fiction from the Michener Center for Writers at the University of Texas at Austin, Lauren has been a professional writer for over a decade. She is the author of the chapbook A Great Dark House (Poetry Society of America, 2023) and a forthcoming novel (Viking/Penguin).

- 2-Year Colleges

- Application Strategies

- Best Colleges by Major

- Best Colleges by State

- Big Picture

- Career & Personality Assessment

- College Essay

- College Search/Knowledge

- College Success

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Dental School Admissions

- Extracurricular Activities

- Graduate School Admissions

- High Schools

- Law School Admissions

- Medical School Admissions

- Navigating the Admissions Process

- Online Learning

- Private High School Spotlight

- Summer Program Spotlight

- Summer Programs

- Test Prep Provider Spotlight

“Innovative and invaluable…use this book as your college lifeline.”

— Lynn O'Shaughnessy

Nationally Recognized College Expert

College Planning in Your Inbox

Join our information-packed monthly newsletter.

Argumentative Essay Writing

Argumentative Essay Examples

Best Argumentative Essay Examples for Your Help

Published on: Mar 10, 2023

Last updated on: Jan 30, 2024

People also read

Argumentative Essay - A Complete Writing Guide

Learn How to Write an Argumentative Essay Outline

Basic Types of Argument and How to Use Them?

Take Your Pick – 200+ Argumentative Essay Topics

Essential Tips and Examples for Writing an Engaging Argumentative Essay about Abortion

Crafting a Winning Argumentative Essay on Social Media

Craft a Winning Argumentative Essay about Mental Health

Strategies for Writing a Winning Argumentative Essay about Technology

Crafting an Unbeatable Argumentative Essay About Gun Control

Win the Debate - Writing An Effective Argumentative Essay About Sports

Make Your Case: A Guide to Writing an Argumentative Essay on Climate Change

Ready, Set, Argue: Craft a Convincing Argumentative Essay About Wearing Mask

Crafting a Powerful Argumentative Essay about Global Warming: A Step-by-Step Guide

Share this article

Argumentative essays are one of the most common types of essay writing. Students are assigned to write such essays very frequently.

Despite being assigned so frequently, students still find it hard to write a good argumentative essay .

There are certain things that one needs to follow to write a good argumentative essay. The first thing is to choose an effective and interesting topic. Use all possible sources to dig out the best topic.

Afterward, the student should choose the model that they would follow to write this type of essay. Follow the steps of the chosen model and start writing the essay.

The models for writing an argumentative essay are the classical model, the Rogerian model, and the Toulmin model.

To make sure that you write a good argumentative essay, read the different types of examples mentioned in this blog.

On This Page On This Page -->

Good Argumentative Essay Examples

Argumentative essays are an inevitable part of academic life. To write a good argumentative essay, you need to see a few good examples of this type of essay.

To analyze whether the example is good to take help from or not. You need to look for a few things in it.

Make sure it follows one specific model and has an introductory paragraph, organized body paragraphs, and a formal conclusion.

Get More Examples From Our AI Essay Writer

How to Start an Argumentative Essay Example

Learning how to start an argumentative essay example is a tricky thing for beginners. It is quite simple but can be challenging for newbies. To start an argumentative essay example, you need to write a brief and attractive introduction. It is written to convince the reader and make them understand your point of view .

Add body paragraphs after the introduction to support your thesis statement. Also, use body paragraphs to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of your side of the argument.

Write a formal conclusion for your essay and summarize all the key elements of your essay. Look at the example mentioned below to understand the concept more clearly.

Check out this video for more information!

Argumentative Essay Example (PDF)

Argumentative Essay Example

Argumentative essays are assigned to university students more often than the students of schools and colleges.

It involves arguments over vast and sometimes bold topics as well.

For university students, usually, argumentative essay topics are not provided. They are required to search for the topic themselves and write accordingly.

The following examples will give an idea of how university students write argumentative essays.

Argumentative Essay Example for University (PDF)

Argumentative Essay Examples for College

For the college level, it is recommended to use simple language and avoid the use of complex words in essays.

Make sure that using simple language and valid evidence, you support your claim well and make it as convincing as possible

If you are a college student and want to write an argumentative essay, read the examples provided below. Focus on the formatting and the vocabulary used.

Argumentative Essay Example for College (PDF)

College Argumentative Essay Sample (PDF)

Argumentative Essay Examples for Middle School

Being a middle school student, you must be wondering how we write an argumentative essay. And how can you support your argument?

Go through the following examples and hopefully, you will be able to write an effective argumentative essay very easily.

Argumentative Essay Example for Middle School(PDF)

Middle School Argumentative Essay Sample (PDF)

Argumentative Essay Examples for High School

High school students are not very aware of all the skills that are needed to write research papers and essays.

Especially, when it comes to argumentative essays, it becomes quite a challenge for high schools to defend their argument

In this scenario, the best option is to look into some good examples. Here we have summed up two best examples of argumentative essays for high school students specifically.

Argumentative Essay Example for High School (PDF)

High School Argumentative Essay Sample (PDF)

Argumentative Essay Examples for O Level

The course outline for O levels is quite tough. O levels students need to have a good command of the English language and amazing writing skills.

If you are an O-level student, the following examples will guide you on how to write an argumentative essay.

Argumentative Essay Example for O Level (PDF)

Argumentative Essay for O Level Students (PDF)

5-Paragraph Argumentative Essay Examples

A 5-paragraph essay is basically a formatting style for essay writing. It has the following five parts:

- Introduction

In the introduction, the writer introduces the topic and provides a glance at the collected data to support the main argument.

- Body paragraph 1

The first body paragraph discusses the first and most important point related to the argument. It starts with a topic sentence and has all the factual data to make the argument convincing.

- Body paragraph 2

The second body paragraph mentions the second most important element of the argument. A topic sentence is used to start these paragraphs. It gives the idea of the point that will discuss in the following paragraph.

- Body paragraph 3

The third paragraph discusses all the miscellaneous points. Also, it uses a transitional sentence at the end to show a relation to the conclusion.

The conclusion of a five-paragraph essay reiterates all the major elements of an argumentative essay. It also restates the thesis statement using a more convincing choice of words.

Look at the example below to see how a well-written five-paragraph essay looks like

5 Paragraph Argumentative Essay Example (PDF)

Argumentative Essay Examples for 6th Grade

Students in 6th grade are at a point where they are learning new things every day.

Writing an argumentative essay is an interesting activity for them as they like to convince people of their point of view.

Argumentative essays written at such levels are very simple but well convincing.

The following example will give you more detail on how a 6th-grade student should write an argumentative essay.

6th Grade Argumentative Essay Example (PDF)

Argumentative Essay Examples for 7th Grade

There is not much difference between a 6th-grade and a 7th-grade student. Both of them are enhancing their writing and academic skills.

Here is another example to help you with writing an effective argumentative essay.

7th Grade Argumentative Essay Example (PDF)

Tough Essay Due? Hire a Writer!

Short Argumentative Essay Examples

For an argumentative essay, there is no specific limit for the word count. It only has to convince the readers and pass on the knowledge of the writer to the intended audience.

It can be short or detailed. It would be considered valid as far as it has an argument involved in it.

Following is an example of a short argumentative essay example

Short Argumentative Essay Example (PDF)

Immigration Argumentative Essay Examples

Immigration is a hot topic for a very long time now. People have different opinions regarding this issue.

Where there is more than one opinion, an argumentative essay can be written on that topic. The following are examples of argumentative essays on immigration.

Read them and try to understand how an effective argumentative essay is written on such a topic.

Argumentative Essay Example on Immigration (PDF)

Argumentative Essay Sample on Immigration (PDF)

Writing essays is usually a tiring and time-consuming assignment to do. Students already have a bunch of assignments for other subjects to complete. In this situation, asking for help from professional writers is the best choice.

If you are still in need of assistance, our essay writer AI can help you create a compelling essay that presents your argument clearly and effectively.

With our argumentative essay writing service, you will enjoy perks like expert guidance, unlimited revisions, and helpful customer support. Let our essay writer help you make an impact with your essay on global warming today!

Place your order with our college essay writing service today!

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the 7 types of arguments.

The seven types of arguments are as follows:

- Statistical

What is the structure of an argument?

The structure of an argument consists of a main point (thesis statement) that is supported by evidence.

This evidence can include facts, statistics, examples, and other forms of data that help to prove or disprove the thesis statement.

After providing the evidence, arguments also often include a conclusion that summarizes the main points made throughout the argument.

Cathy A. (Literature, Marketing)

For more than five years now, Cathy has been one of our most hardworking authors on the platform. With a Masters degree in mass communication, she knows the ins and outs of professional writing. Clients often leave her glowing reviews for being an amazing writer who takes her work very seriously.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

Legal & Policies

- Privacy Policy

- Cookies Policy

- Terms of Use

- Refunds & Cancellations

- Our Writers

- Success Stories

- Our Guarantees

- Affiliate Program

- Referral Program

- AI Essay Writer

Disclaimer: All client orders are completed by our team of highly qualified human writers. The essays and papers provided by us are not to be used for submission but rather as learning models only.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Ross Douthat

The Case Against Abortion

By Ross Douthat

Opinion Columnist

A striking thing about the American abortion debate is how little abortion itself is actually debated. The sensitivity and intimacy of the issue, the mixed feelings of so many Americans, mean that most politicians and even many pundits really don’t like to talk about it.

The mental habits of polarization, the assumption that the other side is always acting with hidden motives or in bad faith, mean that accusations of hypocrisy or simple evil are more commonplace than direct engagement with the pro-choice or pro-life argument.

And the Supreme Court’s outsize role in abortion policy means that the most politically important arguments are carried on by lawyers arguing constitutional theory, at one remove from the real heart of the debate.

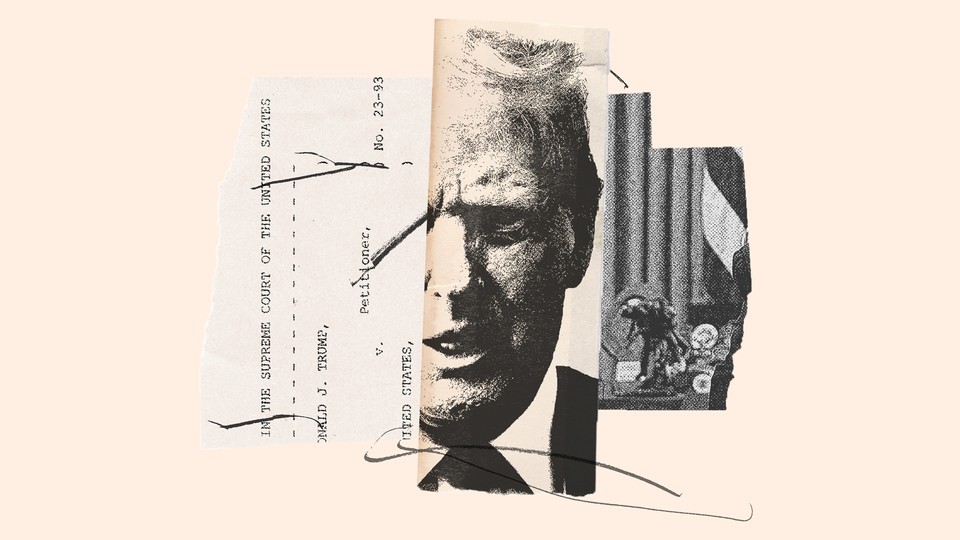

But with the court set this week to hear Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, a direct challenge to Roe v. Wade, it seems worth letting the lawyers handle the meta-arguments and writing about the thing itself. So this essay will offer no political or constitutional analysis. It will simply try to state the pro-life case.

At the core of our legal system, you will find a promise that human beings should be protected from lethal violence. That promise is made in different ways by the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence; it’s there in English common law, the Ten Commandments and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. We dispute how the promise should be enforced, what penalties should be involved if it is broken and what crimes might deprive someone of the right to life. But the existence of the basic right, and a fundamental duty not to kill, is pretty close to bedrock.

There is no way to seriously deny that abortion is a form of killing. At a less advanced stage of scientific understanding, it was possible to believe that the embryo or fetus was somehow inert or vegetative until so-called quickening, months into pregnancy. But we now know the embryo is not merely a cell with potential, like a sperm or ovum, or a constituent part of human tissue, like a skin cell. Rather, a distinct human organism comes into existence at conception, and every stage of your biological life, from infancy and childhood to middle age and beyond, is part of a single continuous process that began when you were just a zygote.

We know from embryology, in other words, not Scripture or philosophy, that abortion kills a unique member of the species Homo sapiens, an act that in almost every other context is forbidden by the law.

This means that the affirmative case for abortion rights is inherently exceptionalist, demanding a suspension of a principle that prevails in practically every other case. This does not automatically tell against it; exceptions as well as rules are part of law. But it means that there is a burden of proof on the pro-choice side to explain why in this case taking another human life is acceptable, indeed a protected right itself.

One way to clear this threshold would be to identify some quality that makes the unborn different in kind from other forms of human life — adult, infant, geriatric. You need an argument that acknowledges that the embryo is a distinct human organism but draws a credible distinction between human organisms and human persons , between the unborn lives you’ve excluded from the law’s protection and the rest of the human race.

In this kind of pro-choice argument and theory, personhood is often associated with some property that’s acquired well after conception: cognition, reason, self-awareness, the capacity to survive outside the womb. And a version of this idea, that human life is there in utero but human personhood develops later, fits intuitively with how many people react to a photo of an extremely early embryo ( It doesn’t look human, does it? ) — though less so to a second-trimester fetus, where the physical resemblance to a newborn is more palpable.