- Mammary Glands

- Fallopian Tubes

- Supporting Ligaments

- Reproductive System

- Gametogenesis

- Placental Development

- Maternal Adaptations

- Menstrual Cycle

- Antenatal Care

- Small for Gestational Age

- Large for Gestational Age

- RBC Isoimmunisation

- Prematurity

- Prolonged Pregnancy

- Multiple Pregnancy

- Miscarriage

- Recurrent Miscarriage

- Ectopic Pregnancy

- Hyperemesis Gravidarum

- Gestational Trophoblastic Disease

- Breech Presentation

- Abnormal lie, Malpresentation and Malposition

- Oligohydramnios

- Polyhydramnios

- Placenta Praevia

- Placental Abruption

- Pre-Eclampsia

- Gestational Diabetes

- Headaches in Pregnancy

- Haematological

- Obstetric Cholestasis

- Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy

- Epilepsy in Pregnancy

- Induction of Labour

- Operative Vaginal Delivery

- Prelabour Rupture of Membranes

Caesarean Section

- Shoulder Dystocia

- Cord Prolapse

- Uterine Rupture

- Amniotic Fluid Embolism

- Primary PPH

- Secondary PPH

- Psychiatric Disease

- Postpartum Contraception

- Breastfeeding Problems

- Primary Dysmenorrhoea

- Amenorrhoea and Oligomenorrhoea

- Heavy Menstrual Bleeding

- Endometriosis

- Endometrial Cancer

- Adenomyosis

- Cervical Polyps

- Cervical Ectropion

- Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia + Cervical Screening

- Cervical Cancer

- Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)

- Ovarian Cysts & Tumours

- Urinary Incontinence

- Genitourinary Prolapses

- Bartholin's Cyst

- Lichen Sclerosus

- Vulval Carcinoma

- Introduction to Infertility

- Female Factor Infertility

- Male Factor Infertility

- Female Genital Mutilation

- Barrier Contraception

- Combined Hormonal

- Progesterone Only Hormonal

- Intrauterine System & Device

- Emergency Contraception

- Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

- Genital Warts

- Genital Herpes

- Trichomonas Vaginalis

- Bacterial Vaginosis

- Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

- Obstetric History

- Gynaecological History

- Sexual History

- Obstetric Examination

- Speculum Examination

- Bimanual Examination

- Amniocentesis

- Chorionic Villus Sampling

- Hysterectomy

- Endometrial Ablation

- Tension-Free Vaginal Tape

- Contraceptive Implant

- Fitting an IUS or IUD

Original Author(s): Oliver Jones Last updated: 20th December 2022 Revisions: 13

- 1 Classification

- 2 Indications

- 3.1 Pre-Operative

- 3.2 Anaesthesia

- 3.3 Operative Procedure

- 3.4 Post-Operative

- 4 Vaginal Birth After Caesarean Section (VBAC)

- 5 Complications

A C aesarean section is the delivery of a baby through a surgical incision in the abdomen and uterus.

In this article, we shall look at the classification of Caesarean sections, its indications, and an outline of the operative procedure.

Classification

A Caesarean section can be classified as either ‘ elective ’ (planned) or ‘ emergency ’.

Emergency Caesarean sections can then be subclassified into three categories, based on their urgency. This is to ensure that babies are delivered in a timely manner in accordance to their or their mother’s needs.

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) recommends that when a Category 1 section is called, the baby should be born within 30 minutes (although some units would expect 20 minutes). For Category 2 sections, there is not a universally accepted time, but usual audit standards are between 60-75 minutes.

Emergency Caesarean sections are most commonly for failure to progress in labour or suspected/confirmed fetal compromise.

Indications

A planned or ‘ elective’ Caesarean section is performed for a variety of indications. The following are the most common, but this is not an exhaustive list:

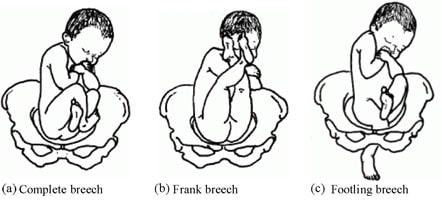

- Breech presentation (at term) – planned Caesarean sections for breech presentation at term have increased significantly since the ‘Term Breech Trial’ [ Lancet, 2000 ].

- Other malpresentations – e.g. unstable lie (a presentation that fluctuates from oblique, cephalic, transverse etc.), transverse lie or oblique lie.

- Twin p regnancy – when the first twin is not a cephalic presentation.

- Maternal medical conditions (e.g. cardiomyopathy) – where labour would be dangerous for the mother.

- Fetal compromise (such as early onset growth restriction and/or abnormal fetal Dopplers) – where it is thought the fetus would not cope with labour.

- Transmissible disease (e.g. poorly controlled HIV).

- Primary genital herpes (herpes simplex virus) in the third trimester – as there has been no time for the development and transmission of maternal antibodies to HSV to cross the placenta and protect the baby.

- Placenta praevia – ‘Low-lying placenta’ where the placenta covers, or reaches the internal os of the cervix.

- Maternal diabetes with a baby estimated to have a fetal weight >4.5 kg.

- Previous major shoulder dystocia .

- Previous 3 rd /4 th degree perineal tear where the patient is symptomatic – after discussion with the patient and appropriate assessment.

- Maternal request – this covers a variety of reasons from previous traumatic birth to ‘maternal choice’. This decision is after a multidisciplinary approach including counselling by a specialist midwife.

Elective Caesarean sections are usually planned after 39 weeks of pregnancy to reduce respiratory distress in the neonate – known as Transient Tachypnoea of the Newborn (TTN).

For those where delivery needs to be expedited prior to 39 weeks’ gestation, the administration of corticosteroids to the mother should be considered. This stimulates development of surfactant in the fetal lungs.

Fig 1 – The different types of breech presentation. Breech at term is an indication for a Caesarean section.

Theatre Procedure

Pre-operative.

Before a Caesarean section, there are a number of basic steps that should be performed:

- The average blood loss at Caesarean section is approximately 500-1000ml, depending on many factors, especially the urgency of the operation.

- Pregnant women lying flat for a Caesarean section are at risk of Mendelson’s syndrome (aspiration of gastric contents into the lung), leading to a chemical pneumonitis. This is because of pressure applied by the gravid uterus on the gastric contents.

- Anti-thromboembolic stockings +/- low molecular weight heparin should be prescribed as appropriate.

Anaesthesia

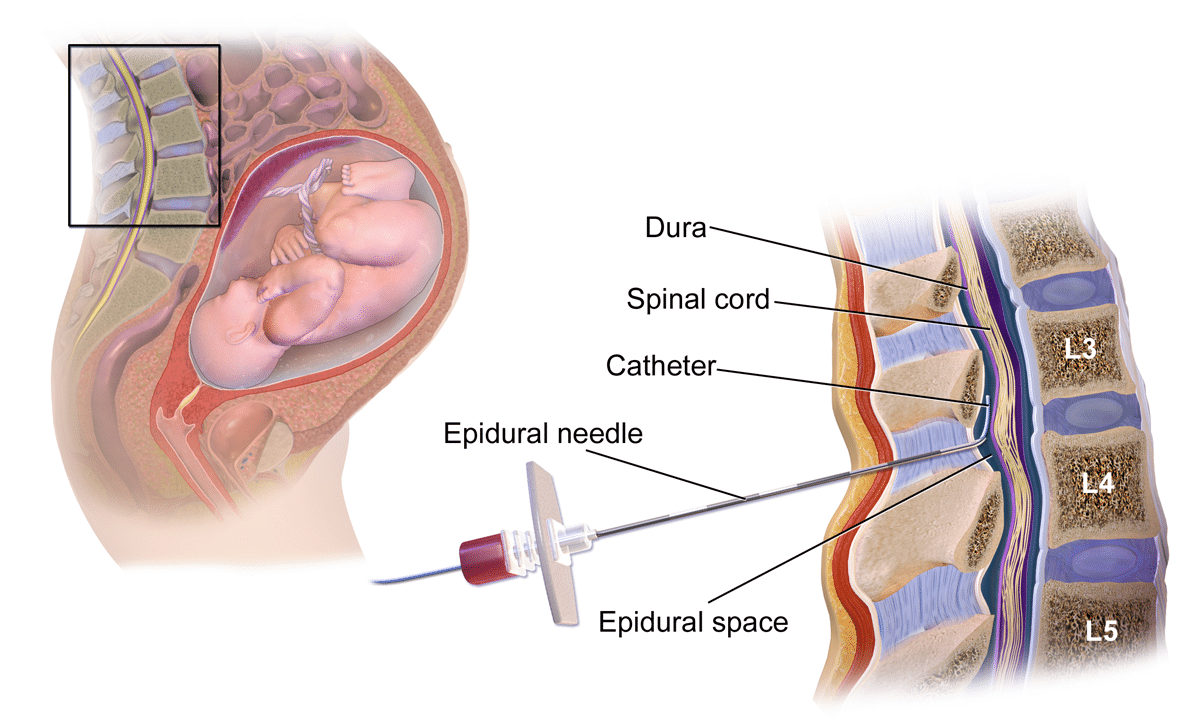

The majority of Caesarean sections are performed under regional anaesthetic – this is usually a ‘topped-up’ epidural or a spinal anaesthetic.

Sometimes a general anaesthetic is required. The can be because of a maternal contraindication to regional anaesthetic, failure of reginal anaesthesia to achieve the required block, or more commonly because of concerns about fetal wellbeing and the need to expedite delivery as soon as possible (often the case for Category 1 sections).

Fig 2 – Epidural anaesthesia is often used in elective Caesarean section.

Operative Procedure

The woman is positioned with a left lateral tilt of 15° – to reduce the risk of supine hypotension due to aortocaval compression.

An indwelling Foley’s catheter is inserted when the anaesthetic is ready, to drain the bladder and to reduce the risk of bladder injury during the procedure.

The skin is then prepared using an antiseptic solution and antibiotics are administered just prior to the ‘knife to skin’ incision.

There are multiple ways to perform a Caesarean, but what follows is a standard technique:

- Skin incision is usually with either a Pfannenstiel or Joel-Cohen – these are both transverse lower abdominal skin incisions.

- Camper’s fascia (superficial fatty layer of subcutaneous tissue)

- Scarpa’s fascia, (deep membranous layer of subcutaneous tissue)

- Rectus sheath, (anterior and posterior leaves laterally, that merge medially)

- Rectus muscle,

- Abdominal peritoneum (parietal)

- This reveals the gravid uterus.

- The visceral peritoneum covering the lower segment of the uterus is then incised and pushed down to reflect the bladder, which is retracted by the Doyen retractor.

- De Lee’s incision (lower vertical) may be required if the lower uterine incision is poorly formed (rare).

- Oxytocin 5 units is given intravenously by the anaesthetist to aid delivery of the placenta by controlled cord traction by the surgeon.

- The uterine cavity is ensured empty, then closed with two layers. The rectus sheath is then closed and then the skin (either with continuous/interrupted sutures or staples).

Post-Operative

After the Caesarean section, observations are recorded on an early warning score chart, and lochia (per vaginal blood loss post delivery) is monitored.

Early mobilisation , eating and drinking and removal of catheter is encouraged to enhance recovery.

Vaginal Birth After Caesarean Section (VBAC)

In women who have had one Caesarean section, any subsequent pregnancies should be counselled regarding the risks of vaginal birth:

- A planned VBAC is associated with a one in 200 (0.5%) risk of uterine scar rupture.

- The risk of perinatal death is low and comparable to the risk of women labouring with their first child.

- There is a small increased risk of placenta praevia +/- accreta in future pregnancies, and of pelvic adhesions.

- The success rate of planned VBAC is 72–75%, however this is as high as 85-90% in women who have had a previous vaginal delivery.

- All women undergoing VBAC should have continuous electronic fetal monitoring by CTG in labour as a change in fetal heart rate can be the first sign of impending scar rupture.

- Risks of scar rupture is higher in labours that are augmented or induced with prostaglandins or oxytocin.

Complications

A primary Caesarean section carries a reduced risk of perineal trauma and pain, urinary and anal incontinence, uterovaginal prolapse, late stillbirth and early neonatal infections (compared with vaginal birth).

However, it is associated with immediate, intermediate and late complications, which are listed below:

- Breech presentation (at term) - planned Caesarean sections for breech presentation at term have increased significantly since the ‘Term Breech Trial’ [ Lancet, 2000 ].

- Other malpresentations - e.g. unstable lie (a presentation that fluctuates from oblique, cephalic, transverse etc.), transverse lie or oblique lie.

- Twin p regnancy - when the first twin is not a cephalic presentation.

- Maternal medical conditions (e.g. cardiomyopathy) - where labour would be dangerous for the mother.

- Fetal compromise (such as early onset growth restriction and/or abnormal fetal Dopplers) - where it is thought the fetus would not cope with labour.

- Primary genital herpes (herpes simplex virus) in the third trimester - as there has been no time for the development and transmission of maternal antibodies to HSV to cross the placenta and protect the baby.

- Previous 3 rd /4 th degree perineal tear where the patient is symptomatic - after discussion with the patient and appropriate assessment.

- Maternal request - this covers a variety of reasons from previous traumatic birth to 'maternal choice'. This decision is after a multidisciplinary approach including counselling by a specialist midwife.

Elective Caesarean sections are usually planned after 39 weeks of pregnancy to reduce respiratory distress in the neonate - known as Transient Tachypnoea of the Newborn (TTN).

The majority of Caesarean sections are performed under regional anaesthetic - this is usually a ‘topped-up’ epidural or a spinal anaesthetic.

The woman is positioned with a left lateral tilt of 15° - to reduce the risk of supine hypotension due to aortocaval compression.

The skin is then prepared using an antiseptic solution and antibiotics are administered just prior to the 'knife to skin’ incision.

- Skin incision is usually with either a Pfannenstiel or Joel-Cohen - these are both transverse lower abdominal skin incisions.

- Camper's fascia (superficial fatty layer of subcutaneous tissue)

- Scarpa's fascia, (deep membranous layer of subcutaneous tissue)

- De Lee's incision (lower vertical) may be required if the lower uterine incision is poorly formed (rare).

[start-clinical]

[end-clinical]

Found an error? Is our article missing some key information? Make the changes yourself here!

Once you've finished editing, click 'Submit for Review', and your changes will be reviewed by our team before publishing on the site.

We use cookies to improve your experience on our site and to show you relevant advertising. To find out more, read our privacy policy .

Privacy Overview

Learn how UpToDate can help you.

Select the option that best describes you

- Medical Professional

- Resident, Fellow, or Student

- Hospital or Institution

- Group Practice

- Patient or Caregiver

- Find in topic

RELATED TOPICS

INTRODUCTION

Other aspects of cesarean birth are reviewed separately:

● (See "Cesarean birth: Preoperative planning and patient preparation" .)

● (See "Anesthesia for cesarean delivery" .)

● (See "Cesarean birth: Postoperative care, complications, and long-term sequelae" .)

- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 09 October 2021

Cesarean scar pregnancy treatment: a case series

- Zahra Heidar 1 ,

- Shahrzad Zadeh Modarres 1 ,

- Zhila Abediasl 1 ,

- Arezo Khaghani 1 ,

- Ensieh Salehi 2 &

- Tayebeh Esfidani 1

Journal of Medical Case Reports volume 15 , Article number: 506 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

2615 Accesses

5 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Cesarean scar pregnancy is a complicated and potentially life-threatening type of ectopic pregnancy. This study reports two women with cesarean scar pregnancy who were successfully treated with systemic methotrexate administration, and two other women who needed local re-administration of methotrexate after systemic injection.

Case presentation

Four Iranian pregnant women aged 29–34 years who were between 5 to 7 gestational weeks with cesarean scar pregnancy diagnosis are described. After a single dose of systemic methotrexate injection, the level of serum beta-human chorionic gonadotropin decreased in two of the women, while fetal activity was observed in the other two women. In the latter patients, methotrexate was injected under transvaginal ultrasound guidance into the gestational sac. As a result, the serum beta-human chorionic gonadotropin level first increased and then decreased in these patients. During the follow-up period, all the patients were stable and no complications were observed. Serum beta-human chorionic gonadotropin levels reached the non-pregnancy range from 4 to 9 weeks after treatment.

When diagnosed at early gestation, cesarean scar pregnancy can be treated successfully with methotrexate administration alone. The clinicians should be aware that the beta-human chorionic gonadotropin level may initially increase after methotrexate injection in some patients. However, the final outcome will be promising if the patients remain stable.

Peer Review reports

Cesarean scar pregnancy (CSP) is a complicated and potentially life-threatening type of ectopic pregnancy. It is estimated that CSP comprises 0.04–0.05% of all pregnancies [ 1 , 2 ]. With the increased number of cesarean deliveries and the widespread use of ultrasound (US) in early pregnancy, the incidence of CSP is increasing [ 2 ]. Two types of CSP have been defined. Type I (endogenic type) is characterized by a gestational sac implanted in the scar that progresses towards the uterine cavity. Type II (exogenic type) is a deep implantation that mainly grows towards the abdominal cavity. Type II is associated with early uterine rupture and vaginal bleeding [ 3 ].

Various medical and surgical treatments including expectant management, systemic methotrexate (MTX), local MTX, dilation and evacuation (D&E), uterine artery embolization, hysteroscopy, and laparoscopy are currently used for the management of CSP [ 4 ].

Methotrexate (MTX) is an antimetabolite drug that has been used in the treatment of molar and ectopic pregnancies, including CSP [ 3 ]. Here, we describe our experiences of four women with CSP who were successfully treated by systemic MTX administration or a combination of systemic and local MTX administration. In this study, the criteria for the diagnosis of CSP using transvaginal ultrasound (TVU) were an empty uterine cavity, a placenta or pregnancy sac implanted in the cesarean scar site, a pregnancy sac filling the niche of the scar, a thin layer (1–3 mm) of myometrium or its absence between the pregnancy sac and the bladder, a closed cervix and an empty cervical canal, a fetal pole with or without cardiac activity, and the presence of a prominent and at times rich vascular pattern in the area of a cesarean section scar with a positive pregnancy test [ 3 ].

Case 1: A 31-year-old Iranian woman, gravida 2, para 1, with a history of cesarean section (7 years before) was referred to a prenatal clinic for first-trimester screening. She had conceived by an intrauterine insemination (IUI) cycle. Abdominal ultrasonography was performed, and since a gestational sac was located lower than the normal position in her uterine cavity, CSP was suspected. A transvaginal ultrasound revealed a blighted ovum with a 6 mm gestational sac. She was asymptomatic, and her vital signs were stable. Her serum beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) level was 7000 IU/L. After evaluating her renal and liver function tests, one dose of systematic MTX (50 mg/m 2 ) was administered. The serum β-hCG level decreased from 7000 to 4900 IU/L after 4 days. During the follow-up period, the β-hCG level decreased continuously. After 1 week, vaginal bleeding occurred and the remnants of pregnancy were expelled. Four weeks after MTX administration, the serum β-hCG level reached the non-pregnancy range. No complications occurred during the treatment.

Case 2: A 34-year-old Iranian woman with a history of cesarean section (8 years before) was referred to our hospital for prenatal care. She had conceived with an in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycle. With abdominal ultrasound imaging, CSP was suspected due to the improper location of the gestational sac. This was confirmed using TVU. The gestational sac was measured to be 10 mm, showing that the gestational age was 6 weeks. The serum β-hCG level was 19,000 IU/L. Her vital signs were stable, and she was asymptomatic. The patient was hospitalized for management, and liver and renal function tests were performed. The patient was counseled for medical and surgical management and opted for medical management. After obtaining informed consent, one dose of 60 mg systemic MTX was administered and repeated 48 hours later. Four days later, her serum β-hCG level reached 29,000 IU/L, and cardiac activity was observed on TVU. For this reason, 0.3 cc KCl was injected into the embryo. Then, 30 mg of MTX was injected transvaginally into the gestational sac. Twenty-four hours later, the serum β-hCG level increased to 45,000 IU/L. As she remained clinically stable, we decided to follow her up with serial serum β-hCG measurements. Four days later, her serum β-hCG level reached 32,000 IU/L and she was discharged. Her serum β-hCG values were measured weekly. Nine weeks later, the serum β-hCG reached the non-pregnancy range. Side effects of MTX administration were not observed. Serial ultrasound assessments revealed a persistent 15 mm mass (including blood clots and fragments of decidualized tissue and secretory endometrium) in the cesarean scar, which was removed by hysteroscopy.

Case 3: A 29-year-old Iranian woman, gravida 3, with a history of one miscarriage in the sixth week of pregnancy and a history of cesarean section (4 years before) was referred to our hospital for routine pregnancy ultrasonography. The gestational age based on the last menstrual period was 7 weeks. An abdominal ultrasound scan suggested CSP with a fetal pole lower than the normal position with a gestational age of 6 weeks. TVU revealed CSP with a blighted ovum, and the β-hCG level was 11,000 IU/L. The patient did not have vaginal bleeding, abdominal pain, or discomfort. After consultation with the patient and her husband about the management, her vital signs were checked and kidney and liver function tests were performed. Afterward, she received 50 mg/m 2 of systemic MTX. Four days later, the β-hCG level reached 10,000 IU/L. Seven days later, the β-hCG level decreased to 7500 IU/L. The patient had spotting but remained stable. The β-hCG level was checked weekly. In the sixth week, the β-hCG level decreased to less than 10 and the pregnancy remnants (approximately 2 cm) were removed by hysteroscopy.

Case 4: A 33-year-old Iranian woman, gravida 3, para 2, live 2, with a history of cesarean section (6 years before) whose last menstrual period was 5 weeks before was admitted to our hospital owing to the diagnosis of CSP using TVU. The gestational age was 5 weeks and 5 days. Her vital signs were stable, and she had no abdominal pain and no vaginal bleeding symptoms.

The β-hCG level was 3546 IU/L. After consulting with the patient, she was hospitalized. After performing kidney and liver function tests, she received 50 mg/m 2 systemic MTX. Four and seven days after MTX injection, the β-hCG level reached 4800 IU/L and 5750 IU/L, respectively. The second dose (70 mg) was repeated 7 days after the first dose. Four days later (after the second dose), the β-hCG level became 6500 IU/L. Since fetal heart activity was observed on vaginal ultrasonography, MTX (70 mg) was administered transvaginally. Two days after transvaginal MTX injection, the β-hCG level increased to 7100 IU/L. Four days after transvaginal MTX administration, the β-hCG level decreased to 4100 IU/L. Afterward, the patient was monitored for her stability and absence of symptoms. Two days later, mild vaginal bleeding occurred. The β-hCG level was checked weekly. The patient was discharged in good general condition and was advised to check her β-hCG level weekly. Five weeks later, the β-hCG level reached the non-pregnancy range. TVU showed no sac, and the remnants of pregnancy (including fragments of decidualized tissue and secretory endometrium) were removed by hysteroscopy (Table 1 ).

Discussion and conclusions

Cesarean scar pregnancy (CSP) is defined by the development of a gestational sac in the myometrium of a previous cesarean scar [ 5 ]. Although the exact pathology underlying CSP is still unclear, impaired healing of the cesarean section wound can predispose women to CSP. Further, CSP may result from a defect in the endometrium caused by trauma [ 6 ]. The symptoms of CSP are unspecific, and one-third of cases are asymptomatic [ 7 ]. In this report, all patients were asymptomatic and were diagnosed on first-trimester ultrasound. Therefore, early routine ultrasound at the beginning of pregnancy is recommended in pregnant women with a history of previous cesarean section. The most common diagnosis techniques of CSP are abdominal ultrasonography, TVU, and color Doppler. The sensitivity of TVU is reported to be 84% [ 8 ]. In all women of this study, the size and location of the gestational sac was determined using TVU.

The treatment options for CSP are medical, surgical, or a combination of them. Since women with CSP are of reproductive age and would like to preserve their fertility, the selected treatment should retain their fertility. Local or systemic administration of MTX is one of the most popular treatments for CSP because of its quick response and fewer side effects. The present study demonstrated that a single dose of systemic MTX administration resulted in a safe treatment without further intervention in two patients with CSP. However, in two other patients, the β-hCG level increased following a single dose of systemic MTX administration. Since the serum β-hCG level was not decreased as expected, multiple doses of MTX as a combination of systemic and local (injected into the sac) MTX were used. Levin et al . reported that 29/36 cases (80.6%) were treated successfully by systemic injection of MTX, while the other 19.4% were treated with a combination of systemic and local (that is, intra-sac) MTX administration [ 9 ]. Bodur et al . concluded that a primary systemic MTX administration was effective for a cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy before 8 weeks of gestational age, a β-hCG concentration of ≤ 12,000 mIU/ml, and negative embryonic cardiac activity [ 10 ]. In the present study, all of the mentioned criteria were present in the two patients who were successfully treated with a primary systemic MTX administration. In this regard, another study demonstrated that the failure of the MTX treatment was associated with a high β-hCG level, advanced pregnancy, and deep implantation. Moreover, it was found that the resolution of pregnancy was relatively faster in the two patients that received a single dose of systemic MTX compared with the other two patients. A clinical trial study indicated that a single dose of systemic MTX had an equally successful rate compared with local MTX administration (67.3% versus 69.2%, respectively). However, the decline of the serum β-hCG level and pregnancy disappearance were faster in the systemic group.

It has been reported that 25% of patients need additional treatment owing to increased β-hCG levels and heart activity following MTX administration. The β-hCG level was an important prognostic factor in treatment failure [ 11 ]. However, no specific β-hCG level has been determined to guarantee treatment success [ 12 ]. In our observations, two patients showed higher β-hCG levels following the first dose of systemic MTX administration. This indicated primary treatment failure. Therefore, an additional injection into the sac (transvaginal MTX injection) was needed.

It is important to know that the serum β-hCG level, the gestational sac volume, and vascularization may temporarily increase after a combined local and systemic MTX administration for the treatment of CSP [ 13 ]. In accordance with the findings of the current study, Timor-Tritsch et al . also reported that the β-hCG level increased after combined local and systemic MTX administration [ 13 ]. Another study found that the mean serum β-hCG level tended to increase in 38 women with ectopic pregnancy in the first 4 days after systemic MTX injection [ 14 ]. In a review of eight patients with CSP, Yamaguchi et al . reported that the β-hCG level first increased and then decreased [ 15 ]. Therefore, the increase of the β-hCG level at the beginning of local MTX injection is probably not worrying if the patient remains stable.

In conclusion, when diagnosed at early gestation, cesarean scar pregnancy can be successfully treated with medical management alone. Nevertheless, in advanced gestation, it usually leads to excessive vaginal bleeding, higher β-hCG levels, and risk of failure of medical management alone. The clinicians should be aware that the β-hCG level, as a prognostic factor for treatment success, may initially increase after MTX injection in some patients. However, the final outcome will be promising if the patients remain stable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting this article are included within the article

Abbreviations

- Cesarean scar pregnancy

- Methotrexate

Beta-human chorionic gonadotropin

Intrauterine insemination

Transvaginal ultrasound

In vitro fertilization

Maymon R, Halperin R, Mendlovic S, Schneider D, Herman A. Ectopic pregnancies in a Caesarean scar: review of the medical approach to an iatrogenic complication. Hum Reprod Update. 2004;10(6):515–23.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Baradwan S, Khan F, Al-Jaroudi D. Successful management of a spontaneous viable monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancy on cesarean scar with systemic methotrexate: a case report. Medicine. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000012343 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Le Minh Tam TK, Linh TM, Thu PTM, Khanh TV, Anh NTK, Nguyen NTT, et al . Outcome of cesarean scar pregnancy treated with local methotrexate injection. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2020;82(1):15.

Google Scholar

Junaid D, Chaudhry S, Usman M, Hussain R. Caesarean scar ectopic pregnancy: a case series. Pak J Med Dent. 2018;7(3):4.

Wang S, Beejadhursing R, Ma X, Li Y. Management of Caesarean scar pregnancy with or without methotrexate before curettage: human chorionic gonadotropin trends and patient outcomes. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):1–6.

Article Google Scholar

Xiao J, Zhang S, Wang F, Wang Y, Shi Z, Zhou X, et al . Cesarean scar pregnancy: noninvasive and effective treatment with high-intensity focused ultrasound. Am J Obstetr Gynecol. 2014;211(4):356 e1-356 e7.

Gonzalez N, Tulandi T. Cesarean scar pregnancy: a systematic review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24(5):731–8.

Pristavu A, Vinturache A, Mihalceanu E, Pintilie R, Onofriescu M, Socolov D. Combination of medical and surgical management in successful treatment of caesarean scar pregnancy: a case report series. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):1–10.

Levin G, Zigron R, Dior UP, Gilad R, Shushan A, Benshushan A, et al . Conservative management of Caesarean scar pregnancies with systemic multidose methotrexate: predictors of treatment failure and reproductive outcomes. Reprod Biomed Online. 2019;39(5):827–34.

Bodur S, Özdamar Ö, Kılıç S, Gün I. The efficacy of the systemic methotrexate treatment in caesarean scar ectopic pregnancy: a quantitative review of English literature. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;35(3):290–6.

Lipscomb GH, Givens VM, Meyer NL, Bran D. Comparison of multidose and single-dose methotrexate protocols for the treatment of ectopic pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(6):1844–7.

Menon S, Colins J, Barnhart KT. Establishing a human chorionic gonadotropin cutoff to guide methotrexate treatment of ectopic pregnancy: a systematic review. Fertil Steril. 2007;87(3):481–4.

Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A, Santos R, Tsymbal T, Pineda G, Arslan AA. The diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of cesarean scar pregnancy. Am J Obstetr Gynecol. 2012;207(1):44 e1-44 e13.

Saraj AJ, Wilcox JG, Najmabadi S, Stein SM, Johnson MB, Paulson RJ. Resolution of hormonal markers of ectopic gestation: a randomized trial comparing single-dose intramuscular methotrexate with salpingostomy. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92(6):989–94.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Yamaguchi M, Honda R, Uchino K, Tashiro H, Ohba T, Katabuchi H. Transvaginal methotrexate injection for the treatment of cesarean scar pregnancy: efficacy and subsequent fecundity. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(5):877–83.

Download references

Acknowledgements

There were no funding resources.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Clinical Research Development Center, Mahdiyeh Educational Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Shishe Gar Khaneh Alley, Fadaian Islam Ave, Shoosh Sq, Tehran, Iran

Zahra Heidar, Shahrzad Zadeh Modarres, Zhila Abediasl, Arezo Khaghani & Tayebeh Esfidani

Fertility and Infertility Research Center, Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences, Bandar Abbas, Iran

Ensieh Salehi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Examination and treatment of the patient were performed by ZH, SZ, ZA, and TS. The manuscript writing was performed by TS, AK, and ZH. ES edited the final version of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Tayebeh Esfidani .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this case series report. A copy of the written consents is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Heidar, Z., Zadeh Modarres, S., Abediasl, Z. et al. Cesarean scar pregnancy treatment: a case series. J Med Case Reports 15 , 506 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-03081-0

Download citation

Received : 01 March 2021

Accepted : 24 August 2021

Published : 09 October 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-03081-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Case series

Journal of Medical Case Reports

ISSN: 1752-1947

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

9 Cesarean Birth Nursing Care Plans

Cesarean birth, also termed cesarean section , is the delivery of a neonate by surgical incision through the abdomen and uterus. The term cesarean birth is used in nursing literature rather than cesarean delivery to accentuate that it is a process of birth rather than a surgical procedure. This method may occur under planned, unplanned, or emergency conditions. Indications for cesarean birth may include abnormal labor , cephalopelvic disproportion, gestational hypertension or diabetes mellitus , active maternal herpes virus infection, fetal compromise, placenta previa , or abruptio placentae .

Table of Contents

Nursing problem priorities, nursing assessment, nursing diagnosis, nursing goals, 1. initiating patient education and health teachings, 2. managing acute pain, 3. preventing infections, 4. preventing hypovolemia and hemorrhage, 5. promoting safety and preventing injuries, 6. reducing anxiety and fear, 7. promoting adherence to therapeutic regimen, 8. administering medications and pharmacologic support, recommended resources, references and sources, nursing care plans and management.

The nursing care plan for patients undergoing a Cesarean birth involves monitoring vital signs, incision site, and post-operative pain, providing education on incision care and postpartum recovery, and assisting with early ambulation and mobilization. Nursing management includes providing pain relief measures, promoting deep breathing and coughing exercises to prevent complications, administering prescribed medications, assessing and managing incision site complications, and providing emotional support and guidance throughout the recovery process.

The following are the nursing priorities for patients undergoing a Cesarean birth:

- Pain management and comfort

- Incision site assessment and care

- Monitor vital signs and post-operative complications

- Promotion of breastfeeding and bonding

- Education on postpartum recovery and self-care

- Assistance with early ambulation and mobilization

- Emotional support and guidance

Assess for the following subjective and objective data:

- Incision site pain or discomfort

- Swelling, redness, or discharge at the incision site

- Post-operative bleeding or unusual vaginal discharge

- Difficulty or pain while moving or walking

- Fatigue or exhaustion

- Breast engorgement or difficulty with breastfeeding

- Emotional changes such as mood swings or baby blues

- Incision site infection or wound complications (less common but possible)

Following a thorough assessment, a nursing diagnosis is formulated to specifically address the challenges associated with cesarean birth based on the nurse ’s clinical judgment and understanding of the patient’s unique health condition. While nursing diagnoses serve as a framework for organizing care, their usefulness may vary in different clinical situations. In real-life clinical settings, it is important to note that the use of specific nursing diagnostic labels may not be as prominent or commonly utilized as other components of the care plan. It is ultimately the nurse’s clinical expertise and judgment that shape the care plan to meet the unique needs of each patient, prioritizing their health concerns and priorities.

Goals and expected outcomes may include:

- The client will verbalize understanding of indications for cesarean birth and postoperative expectations.

- The client will state that they feel well prepared for cesarean birth.

- The client will recognize this as an alternative childbirth procedure to achieve the best result possible in the end.

- The client will perform or participate in necessary procedures appropriately to understand the rationale behind the actions.

- The client verbalizes reduced discomfort or pain.

- The client appears relaxed, can rest or sleep , and participates appropriately.

- The client verbalizes methods that provide relief.

- The client demonstrates relaxation skills and diversional activities as indicated for the situation.

- The client is afebrile (temperature below 38℃/100.4℉) and free of purulent drainage or erythema of the surgical site.

- The client achieves timely wound healing without complications.

- The client’s amniotic fluid remains clear with a mild odor.

- The client remains normotensive, with fewer than 800 ml blood loss.

- The client has scant to no bleeding on the surgical dressing.

- The client’s urine-specific gravity remains between 1.003 and 1.030.

- The client’s weight loss is not more than 5 to 10 lbs (11 to 22 kgs).

- The client displays optimal FHR.

- The client manifests normal variability on the monitor strip.

- The client reduces the frequency of late or prolonged variable decelerations .

- The mother is free of injury .

- The client and her partner discuss feelings about cesarean birth.

- The client appears relaxed and comfortable.

- The client and her partner will verbalize fears for the safety of herself and the infant.

- The client and her partner will express decreased anxiety after explaining cesarean birth.

- The client will identify and discusses negative feelings.

- The client will verbalize confidence in herself and her abilities.

- The client will identify coping strategies for the present situation.

- The client will verbalize fears and feelings of vulnerability.

- The client will express individual needs and desires.

- The client will participate in the decision-making process whenever possible.

- The client will participate in the development of goals and care plans.

- The client will demonstrate behaviors necessary to incorporate a therapeutic regimen in daily life.

- The client will participate in the decision-making process about the infant.

- The client will demonstrate techniques to enhance the care of the infant.

- The client will display a desire to strengthen her parenting skills.

Nursing Interventions and Actions

Therapeutic interventions and nursing actions for patients undergoing a cesarean birth may include:

Cesarean section (CS) is one of the most common major surgical procedures worldwide. Despite being a vital obstetric procedure that saves the lives of women and infants, it is not free of short and long-term adverse events for both. Childbearing women themselves, their relatives, and society might prefer delivery by a CS due to a lack of general knowledge about the advantages of vaginal delivery, fear from pain, widespread misconceptions about urinary and sexual functions after vaginal delivery, and the misbelief that a CS is safer for the baby (Wali et al., 2020).

Assess the client’s or couple’s level of understanding. Determining the level of understanding facilitates the planning of preoperative teaching and identifies content needs.

Appraise knowledge toward the procedure. Most clients fail to retain the information instilled during childbirth classes. Therefore, clients have difficulty remembering or understanding the details during the entire process.

Assess the level of stress and whether the procedure was planned or not. Defines the client’s or couple’s readiness to incorporate information. Clients who are extremely worried about surgery may need a detailed explanation of the procedure to reduce their anxiety to a tolerable level.

Provide accurate information in easy-to-understand terms and clarify misconceptions. The stress of the situation can affect the client’s ability to understand the information required to make informed decisions. They may not process the new information if they do not understand the terminology.

Encourage the couple to ask questions and verbalize their understanding of the matter. Provides an opportunity to assess and evaluate the client’s or couple’s understanding of the situation. Answer all specific questions that the couple has and fill in gaps in knowledge as necessary. Be certain that all information that you offer is correct.

Review indications necessitating alternative birth methods. Cesarean birth should be viewed as an alternative and not an abnormal situation to enhance maternal and fetal safety and well-being.

Explain preoperative procedures in advance and present rationale as appropriate. Explanation of the logical reasons why a particular choice was made is vital in preparation for the procedure. Immediate preoperative procedures such as surgical skin preparation, eating nothing before the time of surgery, premedications, and method of transport to surgery should be clearly explained by the nurse.

Review the necessity for postoperative measures. Educate the client about the rationale behind necessary postoperative measures such as indwelling bladder catheter, IV fluid administration, and placement of an epidural catheter for post-procedure pain relief (if preferred by the client). Knowing the rationale behind the procedures may allow the client to feel a sense of control over her situation.

Educate the client preoperatively and reinforce learning postoperatively, including demonstration of leg exercises, proper coughing, deep breathing techniques, incentive spirometry , splinting, and abdominal tightening exercises. Provides routine to prevent complications associated with venous stasis and hypostatic pneumonia and lessen stress on the operative site. Abdominal tightening reduces distress associated with gas formation and abdominal distension. Periodic deep breathing exercises fully aerate the lungs and help prevent stasis of lung secretions. Preoperative education can help reduce anxiety about the procedure and clients are more likely to comprehend what is being taught.

Stress anticipated sensations further during the delivery and recovery period. Knowing the possible outcomes helps prevent unnecessary anxiety. Preoperative teaching aims to acquaint the client with the cesarean procedure and any special equipment used.

Use visual aids during teaching if necessary. Draw pictures or show illustrations of anatomy, as needed. These materials could enhance the client’s learning experience and make it easier to understand and recall the teachings fully. See the resources section below for a list of teaching aids you can use.

Discuss and develop a postoperative pain management plan and review the use of the pain scale. Developing a pain management plan with the client increases the likelihood of successful pain management. Some clients may expect that cesarean birth produces less pain than a vaginal birth or fear becoming addicted to opioid agents (Wali et al., 2020).

Note the presence of maternal factors that negatively affect placental circulation and fetal oxygenation. Decreased circulating volume or vasospasms within the placenta decrease oxygen available for fetal uptake. Vasospasm in gestational hypertension impedes blood flow to the mother’s organs and placenta, reducing maternal blood flow and nutrition flow and decreasing available oxygen to the fetus.

Document fetal heart rate (FHR), note any changes or decelerations during and following contractions. Owing to hypoxia, fetal distress may transpire; may be displayed by reduced variability, late decelerations, and tachycardia followed by bradycardia. Late decelerations suggest that the placenta is not delivering enough oxygen to the fetus. Infection from prolonged rupture of membranes also increases FHR (Ghi et al., 2020).

Examine color and amount of amniotic fluid when membranes rupture. Fetal distress in vertex presentation is manifested by meconium staining, resulting from a vagal response to hypoxia. Meconium staining is a common complication during labor and is a common cause for cesarean birth as shown by 5% to 25% of meconium-stained amniotic fluid cesarean deliveries (Hasan et al., 2021; Fernandez et al., 2018).

Document the presence of variable decelerations; change client’s position from side to side. Variable decelerations suggest that there is inadequate amniotic fluid to cushion the cord or it is being compressed. Compression of the cord between the birth canal and presenting part may be relieved by position changes. The woman should be turned to her left side to relieve pressure on the umbilical cord and improve blood flow through it.

Auscultate FHR when membranes rupture. In the absence of full cervical dilation, occult or visible prolapse of the umbilical cord may necessitate cesarean birth. Rates outside the normal range of 110 to 160 beats/minute for a term fetus suggest a prolapsed umbilical cord after an amniotomy was performed.

Monitor fetal heart response to preoperative medications or regional anesthesia . Following delivery, narcotics normally reduce FHR variability and necessitate naloxone (Narcan) administration to reverse narcotic-induced respiratory depression . Maternal hypotension results from local anesthetic blockade of the sympathetic nervous system leading to vasodilation. Because uterine blood flow is not autoregulated, a decrease in maternal blood pressure decreases uteroplacental perfusion. Fetal bradycardia occurs within 15 to 45 minutes after initiation of both epidural and combined spinal-epidural (CSE) anesthesia (Galante, 2010).

Apply internal lead, and monitor fetus electronically as indicated. Gives more precise measurements of fetal response and condition. Continuous electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) allows the nurse to collect more data about the fetus, which is why it is used commonly in most hospitals. FHR and uterine contraction patterns are continuously recorded.

Administer supplemental oxygen to mother via mask. Maximizes oxygen available for placental uptake. Administer 10L/min for 30 minutes to increase fetal oxygenation. Oxygen administration has also been used prophylactically in the second stage of labor on the assumption that this is a time of high risk for fetal distress (Fawole & Hofmeyr, 2012).

Administer IV fluid bolus before initiation of epidural or spinal anesthesia. Optimizes uteroplacental perfusion helps prevent a hypotensive response. Administer saline solution to improve cardiac output, circulatory volume, and uteroplacental perfusion. However, the nurse should observe for fluid volume overload and pulmonary edema.

Implement amniotransfusion, as indicated. Amniotransfusion involves instilling a saline infusion by catheter into the uterine cavity to restore amniotic fluid volume to relieve umbilical cord compression that can interrupt fetal oxygenation.

Assist the healthcare provider with the elevation of the vertex, if required. Position changes may reduce pressure on the cord. Manual elevation of the fetal presenting part using two fingers or the whole hand through the vagina can be done, as well as positioning the client into a steep Trendelenburg position, exaggerated Sim’s position or knee-chest position to relieve cord compression until cesarean birth is performed (Ahmed & Hamdy, 2018).

Implement measures to reduce uterine activity, as prescribed. Excess uterine activity (tachysystole) is more than five contractions in 10 minutes, averaged over 30 minutes (the normal is five contractions or fewer in 10 minutes). Discontinuing oxytocin or administering tocolytics that decrease the healthcare provider may prescribe uterine activity.

Administer tocolytic drugs as prescribed by the healthcare provider. See Pharmacologic Management

Plan the presence of a pediatrician and neonatal intensive care nurse in the delivery room for both scheduled and emergency cesarean births. Due to underlying maternal conditions and alternative birth, the neonate may be preterm or experience altered responses, necessitating immediate care or resuscitation.

The experience of pain during childbirth is complex and subjective. Several factors can affect the client’s perception of labor pain, making each experience unique. Consistently, pain during childbirth is ranked high on the pain rating scale compared to other painful life experiences (Labor & Maguire, 2008). Cesarean birth is among surgery procedures that induce pain, and surgery threatens the body’s integrity. Increased serum catecholamines and cortisol may lead to decreased pelvic blood flow and increased pain during labor while disrupting normal labor and delivery, prolonged deliveries, emergency cesarean birth, medical and surgical interventions, and increased dissatisfaction with childbirth experiences (Ahmadi, 2020).

Assess location, characteristics, frequency, severity, and onset/duration of pain, especially related to the indication for cesarean birth. Data can help indicate the suitable choice of treatment and guide interventions. The client awaiting imminent cesarean birth may encounter varying degrees of discomfort, depending on the indication for the procedure, e.g., failed induction, dystocia . A study determined that the reasons for performing cesarean birth were the above-normal baby’s weight, fetal distress, dystocia, placenta previa, placenta abruption, decreased fetal percentage, and malposition (Solehati & Rustina, 2015).

Assess the client’s perceptions, along with behavioral and physiological responses. Research shows that experiencing pain during labor and early puerperium is higher in women after a cesarean birth. However, many clients opt to deliver via cesarean for fear of pain (Ilska et al., 2020). According to research conducted in Iran, over 70% of pregnant women demand cesarean without medical necessity, 92% of which are due to fear of labor pain and normal delivery complications. Correcting false client perceptions may help them prepare adequately in dealing with childbirth pain.

Note the client’s attitude toward pain and use of specific pain medications. Fear of labor pain is the most common fear of childbirth (Ahmadi, 2020). According to previous studies, fear of pain increases the amount of pain and stress during labor. Additionally, the pain intensity is influenced by cultural factors. Culture has a role in pain tolerance and psychological perception of pain (Solehati & Rustina, 2015). Some clients may avoid pharmacological pain relief because of cultural and religious beliefs.

Educate the patients about the effects of regional and general anesthesia. See Pharmacologic Management

During labor and delivery

Perform pain assessment every time the client reports pain. Note, compare, and investigate changes from previous reports to identify labor progress or rule out worsening of the client’s condition or development of complications. Always rate the client’s pain using a rating scale and identify its characteristics (frequency, duration, severity, intervals).

Monitor the client’s vital signs. Note for signs of tachycardia, hypertension , and increased respirations. Changes in these vital signs often indicate acute pain and discomfort.

Observe nonverbal cues of pain, especially in clients who cannot communicate. The nurse’s observations may not always be congruent with verbal reports indicating the need for further evaluation , especially in clients who cannot communicate verbally or clients who strictly adhere to their birth plan, which strictly prohibits the use of pharmacologic agents for pain relief. Nevertheless, these women should be assured that pain relief is available at any time during labor.

Avoid anxiety-producing circumstances (e.g., loss of control) and encourage the presence of a partner. Levels of pain tolerance are individual and are affected by various factors. Extreme anxiety following an emergency may develop discomfort due to fear, tension, and pain affecting the client’s ability to cope. Providing social and professional support to the client creates comfort and reassurance and reduces pain (Ahmadi, 2020).

Encourage the client to verbalize feelings about pain. Allow the client to verbalize her perceptions about pain and acknowledge the pain experience. Pain is a subjective experience and cannot be felt by others. Convey acceptance of the client’s response to pain.

Teach and demonstrate proper relaxation techniques—position for comfort as possible. Use therapeutic touch , as appropriate. Relaxation techniques such as deep breathing exercises, music therapy, massages, etc., can help decrease anxiety and tension, promote comfort, and enhance a sense of well-being. Excessive fear and worry increase the release of catecholamines such as adrenaline and potentiate painkiller stimuli, increase the perception of pain in the cerebral cortex and decrease pain tolerance (Ahmadi, 2020).

Review client’s knowledge of and expectations about pain management and previous experiences with pain and methods used. Antenatal childbirth preparation has a role in increasing maternal satisfaction and may reduce pain scores. Antenatal education is also essential when obtaining consent from the client; the aim is to provide good information to facilitate mothers to form realistic expectations about pain management during childbirth (Labor & Maguire, 2008).

Postpartum care and interventions

Encourage adequate rest periods after cesarean birth. The period after cesarean birth includes recovery from surgery and adapting to motherhood. The client needs to rest adequately to prevent fatigue and recover appropriately before assuming the new role of being a mother. Parents may appreciate early discharge, as it provides the family, including older siblings, an opportunity to be together in the home environment (Kruse et al., 2020). Additionally, it provides adequate social and moral support for the woman.

Discuss with family ways to assist the client and reduce the pain. Emotional and psychological support provided by the family can help in recovery and reduce postpartum pain.

If indicated, administer sedatives, narcotics, or preoperative drugs. See Pharmacologic Management

Assess location, characteristics, frequency, severity, and onset/duration of pain, especially related to the indication for cesarean birth. Data can help indicate the suitable choice of treatment and guide interventions. The client awaiting imminent cesarean birth may encounter varying degrees of discomfort, depending on the indication for the procedure, e.g., failed induction, dystocia. A study determined that the reasons for performing cesarean birth were the above-normal baby’s weight, fetal distress, dystocia, placenta previa, placenta abruption, decreased fetal percentage, and malposition (Solehati & Rustina, 2015).

Monitor the client’s vital signs. Note for signs of tachycardia, hypertension, and increased respirations. Changes in these vital signs often indicate acute pain and discomfort.

Observe nonverbal cues of pain, especially in clients who cannot communicate. The nurse’s observations may not always be congruent with verbal reports indicating the need for further evaluation, especially in clients who cannot communicate verbally or clients who strictly adhere to their birth plan, which strictly prohibits the use of pharmacologic agents for pain relief. Nevertheless, these women should be assured that pain relief is available at any time during labor.

Teach and demonstrate proper relaxation techniques—position for comfort as possible. Use therapeutic touch, as appropriate. Relaxation techniques such as deep breathing exercises, music therapy, massages, etc., can help decrease anxiety and tension, promote comfort, and enhance a sense of well-being. Excessive fear and worry increase the release of catecholamines such as adrenaline and potentiate painkiller stimuli, increase the perception of pain in the cerebral cortex and decrease pain tolerance (Ahmadi, 2020).

If the cesarean birth is performed hours after the membranes rupture, a woman’s risk for infection will be higher than if the membranes were still intact. Amniotic fluid helps protect the fetus from infectious agents due to its inherent antibacterial properties. After the rupture of membranes, the cervical canal becomes the usual pathway for cervical and vaginal flora, causing infections. Additionally, the skin also serves as the primary line of defense against bacterial invasion, so when the skin is incised for a surgical procedure, this important line of defense is lost.

Assess history for preexisting conditions or risk factors. Note time of rupture of membranes. Persons with a history of diabetes or hemorrhage have increased chances of infection and poor healing. The risk of chorioamnionitis increases while the pregnancy progresses, which may increase fetal risk contamination.

Assess the client’s vital signs for signs and symptoms of infection. Rupture of membranes occurring 24 hours before the surgery may result in chorioamnionitis before surgical intervention and impair wound healing. An elevated temperature of at least 39℃ (102.2℉) or between 38℃ (100.4℉) and 39℃ (102.2℉) within 30 minutes and one of the clinical symptoms are signs of clinical chorioamnionitis. Chorioamnionitis presents as a febrile illness associated with an elevated WBC count, uterine tenderness, abdominal pain, foul-smelling vaginal discharge, and fetal and maternal tachycardia (Fowler & Simon, 2021).

Assess fetal heart rates regularly. Fetal tachycardia (rate >160 beats per minute) may be the first sign of infection. Poor fetal oxygenation may also occur, especially with abnormal labor (Leifer, 2018). In the presence of fetoplacental infection or inflammation, the production of cytokines and other inflammatory mediators leads to an increase of the FHR baseline secondary to a dysregulation of the thermoregulatory center and the increased metabolic rate (Ghi et al., 2020).

Assess amniotic fluid drainage for color, clarity, and odor. Cloudy, yellow, or foul-smelling amniotic fluid suggests infection, and meconium (green) staining suggests fetal compromise but is also seen with prolonged pregnancy.

Observe for localized signs of infection at the surgical incision site. Surgical site infection (SSI) occurs in up to 11% of women after cesarean birth and is manifested as wound infection, endometritis, or urinary tract infection . The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defined SSI as an infection occurring 30 days after the operative procedure. However, they may appear after discharge and are managed, outpatient. The skin and subcutaneous tissue may have purulent drainage, a positive culture, complaints of pain or tenderness, or evidence of swelling, redness, or heat (Burke & Allen, 2020).

Provide perineal care per protocol, particularly once membranes have ruptured. Decreases risk of ascending infection. Assist the client in maintaining good perineal hygiene by wiping from front to back. Good hygiene reduces the possibility of introducing bacteria into the birth canal. Vaginal cleansing with a 10% solution of povidone-iodine swab stick for 30 seconds should be considered for women in labor, especially those with ruptured membranes (Burke & Allen, 2020).

Strictly adhere to preoperative skin preparation; scrub according to protocol. Decreases risk of skin contaminants entering the operative site, reducing the risk of preoperative infection. High-quality studies found that betadine and chlorhexidine as skin antisepsis preparation are sufficient and optimal when the solution is allowed to dry, per the manufacturer’s instructions (Burke & Allen, 2020).

Record hemoglobin and hematocrit and estimated blood loss during the surgical procedure. The risk of post-delivery infection and poor healing increases if hemoglobin levels are low and blood loss is excessive. Compared with vaginal birth, women having a cesarean birth, especially a repeat cesarean, incur the highest risk for postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) (Burke & Allen, 2020). Excessive blood loss reduces immunity and leads to a lowering of hemoglobin concentration, which increases the risk of infection by negatively affecting macrophage activity and impeding wound healing (Abdelraheim et al., 2019). Greater blood loss is associated with classic incision than lower uterine segment incision.

Stress proper handwashing techniques by all caregivers between therapies/clients. Hand hygiene is the single most effective way to prevent infections. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the CDC recommend hand hygiene as the first, simplest, and most cost-effective technique for infection control. Healthcare providers, clients, and their family members in the healthcare setting need to closely adhere to hand hygiene guidelines to prevent and minimize nosocomial infections (Damanabad et al., 2021).

Maintain sterile techniques for invasive procedures. Using a sterile technique on invasive procedures (e.g., IV start, urinary catheterization , etc.) reduces the microbial count and creates a sterile field that helps prevent infections. Breaks in the technique can lead to infections in the client, leading to higher healthcare costs and severe complications (Tennant & Rivers, 2021).

Encourage early ambulation after cesarean birth. Early mobilization is often part of a surgical bundle “fast track” or “enhanced recovery after surgery” (ERAS). It is recommended to improve many short-term outcomes after surgery, including a rapid return of bowel function and decreased length of hospital stay, thereby reducing the risk for infection (Macones et al., 2019).

Instruct client and family about techniques to protect the skin’s integrity and prevent the spread of infection. Surgical site infections occur in approximately 10% of clients, >80% of which develop after discharge, which indicates a need for the client and their family to be provided with comprehensive information on the normal discharge course, signs and symptoms of infection, activity restrictions, and instructions on when to seek medical attention (Macones et al., 2019). Symptoms to watch out for that may indicate SSI are fever , pain, tenderness, purulent drainage of abscess on the incision site, and evidence of swelling, redness, or heat (Burke & Allen, 2020).

Emphasize the necessity of taking antibiotics as directed and using “leftover” drugs. Premature discontinuation of treatment when the client feels well may yield reinfection and antibiotic resistance. The major contributors to resistance development include clinical misuse, self-medication, ease of availability of antibiotics, and poor hospital-based antibiotic use regulation in both developing and developed countries (Chokshi et al., 2019).

Administer parenteral, intravenous antibiotics within 60 minutes before cesarean birth skin incision, as indicated. See Pharmacologic Management

Obtain blood, vaginal, and placental cultures, as indicated. Evaluate the results of blood and wound cultures before the initiation of antibiotics to help determine the infecting organisms and degree of involvement. Laboratory findings typical of infection include leukocytosis with neutrophilia, a left shift, and lactic acidosis. However, no postpartum infection can be excluded based on lab work alone (Boushra & Rahman, 2021).

During a Cesarean birth, blood loss is a normal occurrence as the uterus is highly vascularized. However, excessive blood loss or postpartum hemorrhage can occur, which is characterized by heavy or continuous bleeding. It is a serious complication that can lead to hypovolemic shock and requires prompt medical intervention, including uterine massage, administration of uterotonics, fluid replacement, and possible blood transfusion to stabilize the patient’s condition and prevent further complications.

Assess the client’s intake and output and document for at least 24 hours. Keep an accurate intake and output record of the client to ensure an adequate fluid balance has been achieved. A full uterus can obstruct a full bladder and fetal head; therefore, encourage voiding every two (2) hours if possible or catheterize if the bladder is distended and the client cannot void.

Assess the client’s respirations, BP, and pulse before, during, and after surgery. To detect the earliest signs of bleeding, monitor blood pressure, pulse, and respiratory rate approximately every 15 minutes for the first hour after surgery, every 30 minutes for the next 2 hours, every hour for the next 4 hours, or as specifically prescribed. A minimal but continued change in vital signs is as ominous a sign of hemorrhage as is a sudden alteration in these measurements.

Assess for signs indicative of possible hemorrhage. Observe for signs of hemorrhage, which include falling blood pressure (more than 20 mmHg systolic), systolic blood pressure less than 80 mmHg, or a drop of 5 to 10 mmHg over several readings; a change in pulse rate greater than 110 beats/minute or less than 60 beats/minute; respirations more rapid and stressed from previous readings; and restlessness and a sense of thirst. Notify the healthcare provider of any changes in vital signs that may indicate hemorrhage.

Assess the client’s dressing on the incision site and check for excessive vaginal discharges. Inspect the dressing over the client’s surgical incision for blood staining each time vital signs are assessed to document no incisional bleeding. Observe the perineal pad for lochia flow and palpate fundal height each time to document uterine contraction. Blood oozing vaginally or from a surgical wound can pool considerably under the client before being otherwise visible.

Assess the client’s fundal height and abdomen regularly. A client who has had spinal or epidural anesthesia will not experience pain on uterine palpation until the anesthesia has worn off. Therefore, uterine palpation should not increase her pain. Palpate gently enough once the anesthesia has worn off to not cause increased pain but thoroughly enough to determine uterine consistency. Assess the remainder of the abdomen for softness. A hard, “guarded” abdomen is one of the first signs of peritonitis .

Note the shift in behavior or mental status and cyanosis of mucous membranes. Oxygen deficits are manifested first by changes in mental status, later by cyanosis. The presentation may include altered cognitive and neuromuscular function in clients with severe fluid volume depletion. Altered mentation can be both a cause and a consequence of volume depletion (Asim et al., 2019).

Remove nail polish on fingernails and toes. Removal of nail polish allows the nurse to visualize the nail beds for assessing circulatory status. During the capillary refill test, pressure is applied on the nail bed until it turns white. Then, the pressure is released, and the amount of time it takes for the blood to return is measured.

Place a towel or wedge under the client’s hip. Placing a towel wedge shifts the uterus off of the inferior vena cava and increases venous return. Compression caused by obstruction of the inferior vena cava and aorta by the gravid uterus in a supine position may cause as much as a 50% decrease in cardiac output (Kim & Wang, 2015).

Encourage the client to increase fluid intake, as indicated. Introduce oral fluid slowly (e.g., ice chips for the first hour, then sips of clear liquid such as ginger ale, Jell-O, tea, or flavored ice). Teach the client to continue to drink large quantities of fluid after they return home (at least 6 glasses daily) so they have adequate body fluid to make breastfeeding successful.

Administer supplemental oxygen via a mask, as indicated. Oxygen administration increases the oxygen available for maternal and fetal uptake. Maintaining adequate uterine perfusion can optimize fetal oxygenation, prevent acidosis, deliver nutrients, and eliminate waste products from the uterine myometrium (Caughey et al., 2018).

Administer IV fluids with or without oxytocin, as indicated. It is important to infuse IV fluids during cesarean birth at a monitored rate. Rapid infusion can lead to cardiac overload, while slow infusion can lead to inadequate circulatory compensation. Oxytocin may be added, as prescribed, to the first one or two liters of IV fluid after surgery to ensure firm uterine contraction. Oxytocin aids myometrium contraction and reduces blood loss from exposed endometrial blood vessels. Be aware that the client is prone to hemorrhage when the oxytocin is discontinued. This is the first time her uterus is asked to maintain contraction on its own, so monitor the client’s vital signs carefully.

Administer blood and blood products as indicated. A strong recommendation on blood transfusion in postpartum hemorrhage is that the client receives RBCs as soon as possible in case of massive hemorrhage. Additionally, the early treatment of coagulopathy with fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and platelets determines maternal morbidity and mortality. Fibrinogen plasma level has been a good predictor of hemorrhage severity because it plays a critical role in maintaining and achieving hemostasis. Fibrinogen concentrates offer rapid restoration of the fibrinogen concentration with a small-volume infusion with minimal preparation time (Bonnet & Benhamou, 2016).

Administer tranexamic acid as prophylaxis, as prescribed. See Pharmacologic Management

After a Cesarean birth, patients may be at an increased risk of falls and injury due to the physical changes and recovery process. They may experience post-operative pain, limited mobility, and difficulty with activities of daily living, which can contribute to a higher risk of accidents. It is important to provide a safe environment, educate patients on proper body mechanics and movement techniques, encourage early mobilization, and implement fall prevention strategies to minimize the risk of injury and promote a safe recovery.

Assess and record the time of first bowel sounds auscultated after the surgery. During surgery, the intestine can feel pressure, resulting in a paralytic ileus or halting of intestinal function with obstruction. Late-onset of bowel movements after cesarean birth with spinal anesthesia can cause discomfort to the mother and prolonged hospital stay (Akalpler & Okumus, 2018).

Assess the client’s voiding pattern, including frequency, output, appearance, and time of the first postoperative output. An indwelling catheter will be inserted during cesarean delivery to reduce bladder injury and increase time to first voiding, leading to early catheter removal and reducing incidences of urinary tract infection (Macones et al., 2019). Additionally, after removing the catheter, the woman should void in 4 to 8 more hours. Assess for bladder refilling by palpation to determine urinary retention , which can be potentially dangerous because a full bladder may inhibit the uterus from contracting, increasing the risk for postpartum hemorrhage.

Assess the surgical incision every 8 hours for every nursing shift . Surgical incisions heal by primary intention. The nurse should routinely assess the surgical incision to ensure that the wound edges are approximated, and there are no signs of infection such as erythema or purulent discharges.

Assess the client’s vital signs, especially the respiratory rate, every 15 minutes for the first 1 to 2 hours and then every 30 minutes for 1 hour according to hospital policy. The nurse should closely monitor the client for depressed respiratory function, especially if general anesthesia has been administered. There is a greater potential for postoperative sedation with general anesthesia than regional anesthesia (Caughey et al., 2018).

Assess the client’s lower extremity reflexes to return sensation to the lower limbs. The administration of spinal or epidural anesthesia during cesarean birth produces numbness to the lower extremities that should disappear after a few hours. To assess for return of sensation, the nurse may elicit the knee-jerk reflex or the Achilles reflex by striking the plantar surface of the foot with a reflex hammer while creating a 90-degree angle.

Remove prosthetic devices before surgery. Before surgery, follow hospital protocols regarding removing jewelry, contact lenses, piercings, hair ornaments, acrylic nails, or nail polish. These accessories can become accidentally dislodged or damaged during surgery. Nail polish should be removed to allow healthcare providers to assess for a capillary refill during the procedure.

Monitor urine output following insertion of an indwelling catheter. An indwelling catheter reduces bladder size and keeps the bladder away from the surgical field. Catheterization may prevent bladder injury and postoperative urinary retention . A distended bladder is also expected to interfere with exposure and complicate surgery (Li et al., 2010). Additionally, the physiologic stress of surgery or lack of blood flow to the kidneys due to decreased blood pressure can cause kidney failure. All reproductive tract surgery also puts the ureter flow at risk because the edema that collects in the surgical area can press on the ureters.

Obtain the urine specimen for routine analysis, protein, and specific gravity. Ensure that laboratory results are available before surgery is started. Preoperative assessment procedures for the client may include circulatory and renal function tests, complete blood count , coagulation profile, serum electrolytes , and blood typing and crossmatching. Keep in mind that blood values need to be evaluated in light of the changes in pregnancy.

Ensure early, if not immediate, removal of indwelling catheter after cesarean birth. Clients without indwelling catheters had a shorter mean ambulation time and length of hospital stay. Even though the urinary catheter was removed 12 hours after surgery, the incidence of urinary tract infection was still significantly higher. Additionally, there is a higher incidence of discomfort and increased time to first voiding in clients with indwelling catheters, according to a Cochrane review (Macones et al., 2019).

Encourage enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) sham feeding (chewing gum) as appropriate after cesarean birth. Problems such as constipation , postoperative ileus, and abdominal distention may be seen as an effect of anesthesia after abdominal surgery. Sham postoperative feeding with chewing gum after abdominal surgery appeared to reduce the time to recover gastrointestinal function (Macones et al., 2019). Chewing gum activates the cephalic vagal reflex and stimulates the digestive cephalic phase by imitating eating (Akalpler & Okumus, 2018).

Encourage early mobilization after cesarean birth, as indicated. Early mobilization can improve many short-term outcomes after surgery, including the rapid return of bowel function, reduced risk of thrombosis , and decreased length of stay (Macones et al., 2019).

Restrict oral intake up to 6 hours before surgery, as indicated. The client may be encouraged to drink clear fluids until 2 hours before surgery. A light meal may be eaten up to 6 hours before surgery. The European Society of Anesthesiology Guideline recommended that adults are allowed clear fluid intake 2 hours before elective surgeries (including cesarean births), and solid food is prohibited for 6 hours (Wilson et al., 2018).

Encourage the use of compression stockings as ordered by the healthcare provider. Pregnant and postpartum women are at an increased risk of venous thromboembolism due to decreased physical mobility after major abdominal surgery. Pneumatic compression stockings may be used to prevent thromboembolic disease in clients who underwent cesarean birth (Macones et al., 2019).

Administer ephedrine or phenylephrine and antiemetics to prevent nausea and vomiting , as prescribed. See Pharmacologic Management